I made this bed of games and now I'm going to play in it.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Shaun Palmer’s Pro Snowboarder: Think You Can Ride Like Me?

Game #38: Shaun Palmer’s Pro Snowboarder, Dearsoft, 2001

If you’ve ever spent time in a used game store, you’ve seen a copy of Shaun Palmer’s Pro Snowboarder. You may not remember seeing it, but you did. Perhaps you did notice, and perhaps you said to yourself, “wait, there’s a Tony-Hawk-style snowboarding game? And it’s not named after Shaun White?”

When SPPS came out, Shaun White was 15 years old. He still makes an appearance in this game, but his avatar is about 3 feet tall and has the voice of a young Anikin Skywalker.

Palmer was Snowboarding’s biggest name in those days. This was at a time when you were more likely to catch Snowboarding on the X Games than at the Olympics. Snowboarding was a sport for tattooed Henry Rollins impersonators, not charming youngsters with bright smiles and endearingly unkempt hair. And Palmer embodied this spirit to the fullest.

Learning about Palmer’s life, I see shades of Bam Margera, someone who now somberly reflects on how early fame arrested his personal growth. After setting his sights on the sport of mountain biking, Palmer became notorious for showing up to races with his naked his body splayed against the front windshield of his tour bus. After coming second place in a mountain-biking championship, he threw his goggles to the ground in frustration. He was the first in the sport to trade in cycling gear for the far-more badass motorcross attire, and routinely passed on sponsorship deals offering upwards of 100k dollars if the deal wasn’t just so.

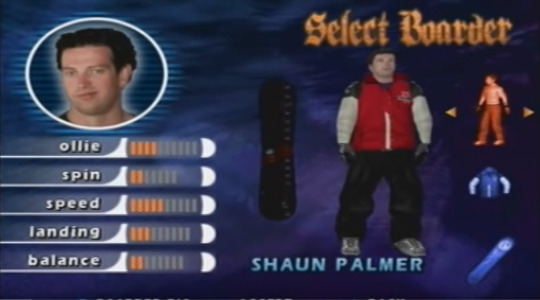

We see this reflected in SPPS in a number of ways, one of them being Palmer’s in-game portrait.

Okay, how about one normal one, and one silly one? Oh, we’re just gonna stick with the snide apathy? Okay.

As I write this, the Winter Olympics are ongoing. Something that makes these Olympics different for me is that I’ve recently come to understand how costly the upper-echelons of success can be. In the Netflix documentary, Jim and Andy, Jim Carry says: “You do whatever you need to do to look like a winner... At some point, when you create yourself to make it, you’re going to have to either let that creation go and take a chance on being loved or hated for who you really are, or you’re gonna have to kill who you really are, and fall into your grave grasping onto a character that you never were.”

This documentary, along with reading about countless other creators, athletes, inventors and entrepreneurs has completely changed the way I look at successful people. When I see someone brandishing a gold medal, to some degree I still see fortune and genius and talent and circumstance just like I always did. But more than that, I see sacrifice. And not just time and relationships, but little chunks of oneself that must be cleaved off like flecks of diamond, leaving behind a rock that is smaller, battle-scarred, but outwardly prettier.

Shaun Palmer is arguably the reason you and I have heard of snowboarding. To the burgeoning in-crowd of the infant sport, he was snowboarding. When flashy moves fell out of favor for technical precision and riders were suddenly expected to be role-models rather than rebels, the Shaun Palmers of the world were relegated to the X-Games, with professional and Olympic snowboarding veering off in a cleaner, more formal direction.

And I’ll admit that I’m glad it did, because I’m a prude and a coward. I don’t want my Olympic gold-medalists to be dangerous bad boys. I want ginger-headed muppets who will charm the pants off the world once every four years and then disappear so I don’t have to worry about what flecks of them got sheared off on their way to the top. I want athletes whose character flaws are easily brushed over in a 1 minute puff piece. I want athletes that help me feel like watching snowboarding counts as a legitimate interest in sports, not my way of clinging to my adolescent video-game fantasies.

Oh, right, the game.

Shaun Palmer’s Pro Snowboarder essentially transplants the core ideas of Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater to snowboarding. It incorporates elements of many snowboarding disciplines, including half-pipe, slopestyle, downhill, and big air. Grab and grind tricks are similar, but flip tricks are a complete curve ball, because it’s the rider’s body, rather than the board, that does the flipping. Landing also takes some getting used to, especially with both ramps, and quarter/half-pipes present. Because the levels are strictly down hill and backtracking requires hitting special targets to teleport back up, missing a pickup or failing to land a trick can be a death sentence for a run. Resetting is frequent.

Essentially, SPPS’s biggest flaw is that it’s snowboarding’s answer to the earlier Tony Hawk games, feeling a bit out-of-date. And in a way it was probably always doomed to be. Snowboarding is far more different from skateboarding than it first seems. Bringing SPPS to life required a drastic rework of the object control code that governs the rider.

The code that dictates what the player character can and cannot do is often called a “character controller.” Before attempting to script a character controller myself, I could never have imagined how disruptive it can be to make even small changes to its behavior. A character controller in a game like SPPS or Sly Cooper or Mario in Mario Odyssey has to account for a dizzying number of states (standing on the ground, walking, in the air after falling, in the air after jumping, clinging to a ledge, running, changing direction while mid-air, using one of several moves while on the ground, while in the air, while running, while using another move, on and on and on).

Not only does changing one of these states usually have implications for the other states, especially those that are not exclusive but can exist simultaneously, (one can be attacking while running in Sly Cooper for instance) but it also has implications for many other systems, including NPC AI, level design, special mechanics, and so-on.

What this means is that a lot of the lessons that the designers learned over the course of the first four Tony Hawk games rarely applied because most of them were specific to the particulars of the Tony Hawk character controller. Things like how dense to make the levels, balancing challenges, making things relatively easy to find, etc. SPPS had to go back to square one on a lot of these things.

The result was not bad per se, it’s just not what fans of Activision’s “action sports” games had come to expect. If SPPS had come out just a couple years earlier, it would have been a huge success. But by the time it came out, its mechanical similarities to the Tony Hawk games were arguably a deficit, because they create an expectation for a similar level of mechanical polish.

So yeah, the game’s difficulty is far above what followers of the THPS series were used to at that point. And the goal system wasn’t a perfect fit with the level design, and the starting stats were probably too low and the scoring system needed some work, and the sound implementation has a couple kinks in it. But that’s nothing that should be too damning of the game were it not for the expectations set by it’s older cousins.

I love games like this. They’re focused and honest. It promises snowboarding and then delivers.

#shaun palmer#shaun palmer's pro snowboarder#tony hawk's pro skater#game#review#stack of shame#too many games#ps2#activision 02#neversoft#extreme sports#retro gaming

1 note

·

View note

Text

Tony Hawk’s Underground: Go Get Some Women, You Woman

Game #37: Tony Hawk’s Underground, Neversoft, 2003

Playing Tony Hawk's Underground as the female avatar is the strangest experience. First of all, it's dead obvious that they were imagining a male character when they wrote the dialogue. Everyone is calls you "dude" and "man" constantly.

At one point, you and your friend, later villain get arrested. This scene starts with a police officer's boot on your avatar's neck. Then the cop tells you you won't make your skateboarding competition unless your avatar is willing to "do them a couple favors, hehe.” This is an outright horrifying image when your avatar is a WOC.

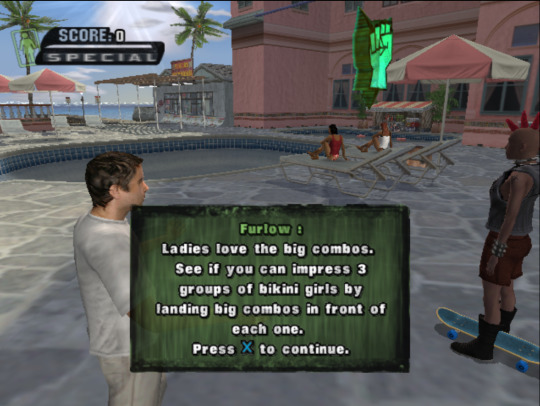

Later, you're put on a mission to retrieve women for a party. You drive up to strangers on a motorized cart full of potted plants. After you impress the women, they say something vaguely flirty and join you, a stranger, on the cart. Keep in mind the cart is a two-seater, so women nos. 2, 3, and 4 are foced to ride with the plants.

Don’t make the combo too big though. You’ll look like you’re compensating.

This party was thrown in your honor for a successful magazine shoot. But it's now your job to go "get some women", because the party honoring you, a woman, is "a total dudefest,” says an NPC you’ve never met and never meet again. This is clearly the result of the female avatar being an afterthought, but taken at face-value, it is incredibly creepy. Not that riding around in a cart full of strange women and plants is any less creepy if you’re playing as a man. Actually it’s almost worse because now it’s creepy in a more intentional way, I guess?

This all is just my reaction as a privileged white cis dude. I don’t even want to think about what this was like for any women playing the game. I think when we talk about representation in games, we forget how bad it used to be, and how many of those problems simply got toned down rather than fixed. Re-experiencing Tony Hawk’s Underground has made it all the more obvious how games pushed women away. This game takes masculinity beyond masculinity, to a place where there are only men, and girl-objects. And if you’re a woman you better count your lucky stars you’re on the skateboard because it’s the only thing keeping you a man.

Ah, I remember you mentioning something like that in your Ted Talk

I considered the possibility that the female avatar is intended to be off-the-charts butch. Call it my last stand in the fight against being overwhelmingly embarrassed and ashamed. But it doesn’t hold water. The female avatar’s voice is bubbly, with a little fry. Her voice is perfectly honed to sound cool and relatable, but not so masculine as to threaten the other characters’ masculinity.

Without having heard this voice, I had used create-a-skate to make a badass biker-punk looking character with a red Mohawk. Now, there’s no reason that someone who looks like my character couldn’t talk like a 12 year old Miranda Cosgrove. But unless you go far, far out of your way to make the character look like the girl from Lazytown, the sound you expect to hear is a brassy 20-something alto with a pack-a-day rasp. This is not the time for lofty hypotheticals about dissonance between a character’s voice an appearance. This is a case where the game gives you a grown woman to play as and then makes her talk like a toddler who takes elocution lessons.

Or perhaps the avatar is meant to be a lesbian, the straw man in my head says. If that’s the case, so is every other woman in this universe. It’s the only way to explain the coos of, “Wanna put lotion on my back?” during the “Impress 3 Bikini Girls” mission. Again, one could disingenuously twist this scenario to try and argue some kind of statement about sexual liberation. But the obvious truth is that the question is directed at the player. “Your combos are sooooooooo big,” comes the voice again.

It should come as no surprise that women weren't flocking to a game where even if you play as a woman, women are still treated as a prize.

0 notes

Text

Superhot - A Better Game Than I Want to Play

Game #36: Superhot, Superhot Team, 2016

Super Hot is an absolutely amazing game that does not deliver the experience I think it promises.

It's whole gimmick is that time only moves when you move. Except that that's a lie. Time just moves incredibly slowly when you're standing still. But even at incredibly slow speeds, bullets move fast enough that you have to worry about them.

I can see how truly stopping time would create a lot of design difficulties that would be difficult to reconcile. If time truly stops, it would probably result in lock-step puzzles where things have to play out in an exact way. Making time progress at a snail's pace means they can introduce a challenge while allowing the puzzles to be flexible. It also means you have to think on your feet and that execution and aim matter almost as much as in a more traditional shooter.

Thing is, I sometimes feel like an apprentice of an obsolete trade. I play a lot of point & click graphic adventure games, I'm accustom to that pacing, I am at peace with lock-step puzzles, and I was really excited going into Super Hot to see a reconciliation of shooters, a genre I've learned to appreciate through much hair-pulling, and point and click adventures, games I've loved since I was a child.

The actual experience is more like a refined take on the bullet-time sequences in Enter the Matrix. And if it were more like what I was hoping for going into it, it would be worse in a lot of ways, it would be more frustrating and give the player less room for self-expression. But it would be worse in ways that I personally like.

0 notes

Text

Yooka Laylee: (Various gurgling sounds)

Game #35: Yooka-Laylee, Playtonic, 2017

I keep reading these reviews by people who have nostalgic feelings for Banjo-Kazooie who hate, hate, goddamn hate Yooka-Laylee. Jim Sterling says he was inches from refusing to give it a rating. People are calling it an abomination, a cash grab, a shining example of where the past should be left in the past.

I’ll tell you what Yooka-Laylee is. Yooka-Laylee is exactly what Playtonic promised it would be; a clone of Banjo-Kazooie. "How did Yooka-Laylee turn out so bad then,” you ask? Simple. Because Banjo-Kazooie is a bad game.

At this point I have a small confession to make. Sometimes, if I knock a game off the stack that I really didn’t like, I’ll choose not to write about it. I’m not trying to be a game basher. That movie that we love to make fun of? People worked their hands to the bone to make it, and they weren’t idiots. There are so many reasons why a game or a movie or any piece of entertainment might turn out the way it does. So I try, as much as possible, to avoid the pitfalls of thoughtlessly bashing things. So if I don’t have anything nice to say, I chose not to say anything.

So I played Banjo Kazooie.

And I didn’t write about it.

So now Yooka-Laylee is out, and nobody, I mean nobody is tearing into this thing with sharper claws than the Banjo nostalgia crowd. And when I hear them describe what they don’t like about it, what I see is a comprehensive list of everything I hate about the beloved original.

I won’t say what those things are, but if you’re curious, go find Jim Sterling’s review, copy/paste it into your favorite text editor, and replace all instances of “Yooka-Laylee” with “Banjo-Kazooie”, and that’s it.

UPDATE:

Yooka Laylee has become the only game that I play muted. You know how a meh day seems a million times worse when you have a headache? Yooka-Laylee also seems a million times worse when you have a headache. And the soundscape of Yooka Laylee gives you a headache.

Having replaced the various gurgles with various podcasts, I was able to dive a little deeper.

What I like:

You are never forced to watch your character do interesting things that you never get to do.

The controls feel darn good

There is a lot of good platforming, which is hard to achieve.

Traversing the level even without an objective can be satisfying

It has renewed interest in the genre

What I don’t like:

Custscenes cannot be skipped, most cutscenes are not fun to watch, most cutscenes are very very long

There are some gameplay moments that are more frustrating than can be justified by a return to an old genre.

I can only play it muted

The level design does this weird thing. In post-golden age 3D platformers, there’s a clear delineation between what surfaces you’re meant to be able to have footing on, and what you can’t. In Sly Cooper, the collision geometry of the level is a lot simpler than the visual geometry of the level. A rocky cliff side might seem like you could get some purchase on it if you jumped on it just right, but the actual collider around it is smooth as glass, and you’ll never be able to jump up that cliff side. In Yooka Laylee, there are areas where the visual geometry and colliding geometry are the same, so you can jimmy your way up mountains. I end up getting to places that I’m not sure I’m allowed to be, but it’s more confusing than satisfying. It makes the terrain feel inconsistent and doesn’t add anything. The game doesn’t particularly care if you find your way outside a level.

I respect when designers choose to discard outmoded conventions. And the infamous “bowl” form that so many open world platform games adopt could be considered one of those conventions. But in a game that is a slave to so many other conventions, I don’t buy it.

It ignores progress. Yooka’s problems are more forgivable if you buy into the popular narrative that it’s the first 3D platformer to come out since Banjo-Kazooie. But it’s not. That gap has seen Psychonauts, Sly Cooper, all the Ratchet and Clank games, Super Mario Galaxy, You can do a revival while still acknowledging that we’ve learned things about making games other than how to increase poly-count .

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shamesplosion II: Regexance

Game #26: Legend of Kay, Neon Studios, 2005

Legend of Kay is part of a peculiar group of games from the waning years of “Character Action Games” (now known as 3D platformers). In some ways these games, including Kay, are some of the best in the genre. The industry had learned how to make controls feel good. Even more esoteric things, like combo moves, had been standardized to a degree. The camera, once nausea inducing, now seamlessly balanced between the gentle hand of the game and the user’s input.

For all that is expert about Legend of Kay, it flies a bit too high. The cutscenes and conversations over-rely on generic, canned animations. I believe that all the voice talent in Legend of Kay were fine actors, but, searching the game’s credits, there was not a dedicated voice over director. As such the voice performances as a whole leave something to be desired.

Why am I picking these nits? Because cutscenes demand a certain quality to justify their presence in a game. Unless they are very good, they drag the experience down. I think I’d have enjoyed Kay more if the conversations had been presented only as text. I don’t say that to be cruel, I honestly believe that the atmosphere would have been easier to establish.

Game #27: Quadrilateral Cowboy, Blendo Games, 2016

Quadrilateral Cowboy vs. Jazzpunk is an amazing case study in game audio

Largely because, given access only to the visual elements of both games, you could easily be forgiven for confusing the two.

Both have an aesthetic that blends minimalist geometry and a honey-mustard color-sheme with 80s cyberpunk, both feature a main character who is sent on various "jobs" which involve traveling to an ambiguously virtual dimension to perform espionage, and both treat pre-digital and recently digital technology as a plaything in their world-building.

If, however, you were given only the audio of each game, you would never confuse the two.

On the blog for Necrophone games, they outline the absolutely bonkers lengths they went to to achieve the sound. Many of the noisemakers used for Jazzpunk's soundscape actually built from scratch, soldering and all, by the game's creators. Bringing that level of depth to a game's sound would be admirable for a sound designer, let alone someone who is also devoted full time to simply making the game.

The soundscape of Jazzpunk is like nothing else I've heard before or since, except perhaps in a Martin Denny record. It's a jangly, agitated mix of synths and old jazz records, a kind of James-Bond-cyber-mambo. The implementation is straightforward for the most part, though outright bizarre at times, with attention-grabbing samples coming it at inappropriate times, but because the rest of the game is so damn weird you forgive it somehow.

For everything that is bizarre about Jazzpunk, it relies on more traditional adventure puzzle mechanics, as well as callbacks (there's a quake clone hidden in a wedding cake). The puzzles are hilariously gratifying to solve, but Jazzpunk does not have many new skills to teach the player.

Quadrilateral Cowboy is, in some ways, more sophisticated than Jazzpunk, and I'm not just talking about their approach to humor. Cowboy's gameplay has something quite new to offer players, and something which feels like somewhat of a holy grail in game design; it makes it feel cool to write code. For a while it seemed like there were so many attempts to make games about coding that reviewers were declaring the effort itself to be futile. But Cowboy has done it.

When you look at the credits in Quadrilateral Cowboy, under audio, it simply says "Soundsnap.com" As such very little in Cowboy's soundscape really feels like it belongs to the game. Many of the sounds are appropriate enough. But they do not have that intangible sense of having somehow come from the game itself.

The implementation of sounds is just as puzzling as in Jazzpunk, but unfortunately it is to negative effect. Point-located sounds are at maximum volume when standing near them, and nearly silent when a few steps away. When the player character throws something, they often emit a cough, not the expected effort sound.

The music is completely diagetic, which can be a powerful decision. It is all licensed, and is used to build the settings and tell you things about the characters. All in all a strong point in the soundscape.

I adore both games, but y'all can guess which has been my enduring favorite.

Game #28: Snuggle Truck, Owlchemy Labs, 2012

This game has been in my library for five years, and I sorely regret not playing it immediately after buying it. Snuggle Truck smacks of the Indie Revolution. These kinds of games, centered around a straightforward-but-wiley physics-based mechanic, will always have a special place in my heart. I found myself wondering if this game would be able to stand out if it were released today. Perhaps it would, given Owlchemy’s outreach.

But how Snuggle Truck would do in today’s market has nothing to do with it’s validity as a work of art, nor does it have anything to do with how deserving it is of commercial success.

I think about the discussion going on in the indie game community, about the “indiepocalypse” and the “indie bubble.” I think it’s easy to forget that there was never a time when making a game was risk free. It was never a case of, “make game, get paid, onto day three of my indie adventure.” It has always been hell. Maybe the marketing wasn’t hell for a short while. Everything else has always been hell.

Game #29: Day of the Tentacle Remastered, Double Fine, 2016

I don’t like admitting that I always kind of thought Broken Age invented the whole switching between characters thing. I’ve been touting myself as a fan of point and click adventure games for a while now, and it’s just embarrassing to think I had gotten the whole picture after having played only a tiny selection from what the golden age of this genre has to offer. Man there are a lot of these things. They are a huge time sink though, often designed to take 40 hours to play. I’m not gonna lie, as much as a I adore these games I have myself a good ol’ fashioned think before I choose to start in on one.

Day of the Tentacle is great, by the way.

Game #30: Judge Dredd: Dredd vs Death, Rebellion, 2003

According to steam, I have played this for 13 minutes. I couldn’t tell you a thing about it because I have no memory of doing so.

Game #31: Elite Dangerous, Frontier Developments, 2014

Oh the deep, dark, horrible shame. My boyfriend bought this game for me at considerable expense in the hopes of giving us another thing to do together. As we booted up the game, he explained to me how we would do one simple thing to boost my cash reserves, and that we’d then be able to do some fun stuff together. He would give me some items, I would sell them. Easy. Would you care to guess how long this took? Trade and sell. How long? How long do you think?

Three hours. It wasn’t because of our internet connection, it wasn’t because we were very far apart, it wasn’t because we had to do multiple runs, that is how long it takes to do all of the preparatory work in the 20 odd menus and locales you need to visit, then rendez-vous in space, then use a slightly smaller set of menus to open a thing, arm something else, send out another thing, there’s something called a limpet, (I’m assuming it’s named after a British cookie) and then I got the thing and then I could fly back to the station blah blah blah blah.

I cried. I cried, people. I felt so much like a dumb failure, like a complete waste of my boyfriend’s generosity, that it honestly upsets me to write about it. He did his best to comfort me and assured me he wasn’t mad (yeah, he saw the cry happen) but we have never played it again. I still technically own it but I have hidden it from my steam library because the mere sight of it is disturbing to me, even now.

Game #32: Mass Effect 2, Bioware, 2010

I have started using Mass Effect 2 to bone up on my German. It’s got full German language support. I only get about a 3rd of what they’re saying. It makes me chuckle how the made-up sci-fi words get pronounced with an American accent.

Game #33: TRI: Of Friendship and Madness, Rat King, 2014

Exposition of any kind is a tough sell, especially in the fantasy genre. Unless you have Ian McKellen in your roster, almost any fantasy writing is going to sound silly when read aloud. Put another way, dramatic voice over in a game is one of those things that cannot be anything less than great. I’m tempted to compare this to Journey. Both do a good job of building a fantastical world with magical architecture and a story that existed long before you arrived, but Journey does it better. They probably could have gotten a budget for voice over, but they chose not to use it, and I think it was the right decision. Even with the best voice cast and writers in the world, human voices would have made the world more familiar, to it’s detriment.

And here’s the thing: in all likelihood, the team behind Journey wrote down just as much detail about the backstory of their game as Tri presents aloud, and a million times more. It may seem that choosing to tell your game’s story without voice over would save effort in terms of storytelling, but nothing could be further from the truth. To expose a world to a player without dialogue, you have to know how your world affects the walls, clothes, materials, gestures, decor, artifacts, absolutely everything the player encounters, because that is the sum total of what you have at your disposal to tell your story. I’m told that there’s a real mind bender of a game waiting for you if you stick with it, so I may revisit.

Game #34: Robot Roller-Derby Disco Dodgeball, Erik Asmussen, 2015

I am a chronic late adopter of multiplayer games, partially because I’ve never been able to afford them when they’re new. I’ve never joined one in time to get good at it at the same pace as all the early adopters. For my entire life playing games, I’ve found myself getting stomped by people who have hung on long after a game’s heyday, people who know every trick, and who’s patience for newbs ran out years ago. Which is a shame because this game is colorful and awesome.

#too many games#stack of shame#gaben#steam sales#shamesplosion#day of the tentacle#snuggle truck#quadrilateral cowboy#jazzpunk#legend of kay#the world doesn't need another review of mass effect 2

0 notes

Text

Goat Simulator: Ceci N’est Pas une Sim

Game #25: Goat Simulator, Coffee Stain, 2014

So, Goat Simulator. Part of why Goat Sim stayed on the stack for so long is because I had been led to believe that to play goat sim was to run around in someone’s half-assed Unity scene, chuckle for five minutes, and then be done forever. I know that the reaction I'm supposed to have to this game is, "it was just funny maymays, they gamed social media so they could release a game while bypassing this whole 'effort' thing."

It turns out that Goat Simulator is feature rich, it is cohesive, it has a vision. The barks of “Cash Grab!” may be valid for the hundreds of imitators that came in Goat Sim's wake, but certainly not of Goat Sim itself. I'm about to use a word to describe Goat Simulator which has perhaps never been used to describe Goat Simulator: polish. Goat Simulator is polished.

Goat Sim has a lot of "juice", little bits of text and graphics that reward you for your accomplishments. Goat Sim seems to be listening for an impossibly huge variety of actions, much like the tricks in a Tony Hawk game. You can mix and match movement mechanics by adding “mutations” to your goat. The levels are full of things to discover which have been lovingly arranged to let you use your moveset. For a game of this scope, there is a considerable amount of music as well. The reason I really love Goat Simulator, really really love it, is because it starts right at that point we’ve all found ourselves while playing Tony Hawk, or Skate, or Grand Theft Auto, right at the point where you’ve made the game act as silly as it’s willing to act. You’ve probed all the edges, bashed yourself against all the walls, nudged all the NPCs. And for this effort you have eeked out one or two cracks in the geometry, found a couple places where they player character will jitter around, if you’re especially determined you might even send a ragdoll flying into the sky, but it’ll be a while before it happens again. The game has dug in it’s heels, it has drawn the line. I will be this silly for you, no further. Goat Simulator’s silliness is limited only by what the team put in, As such, even an inexperienced player can break this game in seconds. You’ll probably rack up a ton of points doing so. And that’s why it works. If an NPC in Tony Hawk died because he tried to climb over a concrete barrier, flickered vertically a few hundred times, and ragdolled, it would be a problem. That NPC was probably supposed to tell you to go search walls and gutters and stair railings for his twelve lost cheese slices. In Goat Sim it doesn’t matter. No gods, only goats.

You might, at this point, be wondering if the game is just complete anarchy, but that’s not the case. It is just as achievement driven as the other games I’ve mentioned, those achievements simply don’t depend on the maintenance of this ridiculous pretense that you’re in a world where common sense laws remotely apply.

I dare say that after playing Goat Sim, the Tony Hawk games seem a bit insulting to one’s intelligence. Really, Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater 2? You’re going to hold a straight face while you explain how I have to grind my skateboard across a crucible full of molten metal? Do me a favor. Goat Sim at least respects me enough to admit it’s all a joke. The music and sound add to the hilarity. A drunken electronic pop mixed with Unity’s doppler algorithm desperately trying to figure out what to do as you bungie across the map many hundreds of times each second because you licked a truck. I think what I love most about Goat Simulator is simply that it has such blatant disregard for convention in spite of coming from an established genre, and yet it’s still a game design success story. People will pooh-pooh it as a quirk of viral marketing, though I don’t know how those people would expect a game like goat simulator to market itself. Not to mention, this criticism starts from the condescending premise that consumers don’t know what they want when they see it.

It’s true that focus groups usually produce nonsense and the layperson is generally not a good source of ideas for a game. But when you put a trailer in front of people, and they all say, “yes, I want that!” and then those same people get the product that trailer was advertising and say “yes, I want this!” you can’t really say they’ve been deceived.

Goat Simulator is great and if you don’t like it you’re a square.

0 notes

Text

Shamesplosion

I’ve been playing more games than I’ve been writing posts. Relying only on the power of my squishy, squishy memory, I’ll try to knock out a bunch of the games I’ve tried.

Game #15: Rocket League, Psyonix, 2015

Spent most of the game obsessing over various steam controller configurations, as I had just gotten mine. I never landed on one I was happy with, which made me think of how in some situations, taking choice away from people will actually make them happier .With less choice, there are fewer alternatives to obsess over.

Game #16: Assassin’s Creed IV Black Flag, Ubisoft, 2013

This game was a gift given to me before I had a graphics card capable of running it. The game technically ran, though it was like a mushy pirate slideshow on a 3 second delay. I didn’t have the heart to tell the person who gave it to me, so I just told them it was awesome and I loved it. Then I got a graphics card for mah birfday, and the first thing I did was load this game. It was like the ending of The Hustler, returning after so much time to conquer an old enemy.

Game #17: Armikrog, Pencil Test, 2015

Much like the American public, I was much more willing to deal with getting stuck for hours in an adventure game when I only owned three of them. A hint system is not a symptom of dumbing-down, it is an adaptation to swelling libraries. My impatience with the obtuse puzzles was also fueled by having read some interviews with the creator.

Game #18: Lego Star Wars: The Complete Saga, Traveler’s Tales, 2009

Lego Star Wars

Game #19: Poly Bridge, Dry Cactus, 2016

It really warms my heart when a game achieves this kind of status, where people are eagerly sharing their own solutions to things. And there are few more deserving projects.

Game #20: Sonic 3D Blast, Traveler’s Tales, 1996

Traveler’s Tales sticks in my mind as a company. Maybe it’s because of how long the logo fmv was in Bug’s Life for PS1. Traveler’s Tales has been quietly making all these B+ games for a long time. I don’t know what tumult they have endured (because their website is down right now) but from the outside they have all the appearance of being a firmament on which the entire game industry chaotically bubbles and roils.

Game #21: 30 Flights of Loving, Blendo Games, 2012

I had high expectations for this darling of the IGDA awards. I think that some media really need to be experienced immediately after release to have the intended impact. Trying to send my mind back to 2012, I can see how this surreal experience with it’s angular art, atmosphere, and compellingly scattered timeline would have been fresh and exciting. Four years after release, the game feels like it’s held back by lack of polish. 3D indie games are still less common than 2D ones, but when 30 Flights came out they were practically nonexistent. The access we have in terms of tools and community are insane. The standards for polish are approaching those of AAA products from the end of the 90s. 30 Flights resembles a 2016 indie game in many respects, which makes those aspects that are not polished stand out.

Game #22: Soundodger+, Studio Bean, 2013

The difficulty of this game is subtle and unexpected. You move your avatar with your mouse to avoid swarms of objects which move in coordination with music. But since the avatar moves 1:1 with your mouse, it should be easy, right? Somehow though, there’s a natural difficulty curve.

Game #23: Ty the Tasmanian Tiger, Krome, 2002

So, Ty. I’d like to start by talking about his face, because it is the perfect totem for the entire rest of the game. All of it’s flaws, strengths, and all the factors leading up to them can be perfectly encapsulated in Ty’s face.

Now I don’t know for sure, but I’d be willing to bet, that Ty’s face didn’t always look like that of a Sonic the Hedgehog fan character. Ty’s eyebrows are crumpled into a permanent scowl over his undivided eyes, and his mouth is pushed all the way back to his neck on both sides, meaning that whenever he speaks his cheeks flap like a cartoon James Cagney.

He’s the only character who’s face works that way, and his constant pissed-off screwed-up badass face is a huge clash with his chipper, happy-go-lucky voice delivery. Of course, his voice and face match perfectly in the edgy, edgy trailer. So there emerges a narrative:

Krome are charged with jumping on the 3D platformer bandwagon. They’re on a 2 year development cycle, and when they start, cute, affable characters are in, at least that’s how it seems. Then, 2001: Jak and Daxter comes out to huge critical acclaim, but sales fail to meet expectations. It isn’t a flop by any means, but it goes gold instead of platinum. The gaming audience is aging, Grand Theft Auto III is king of the castle, games with hopping animals are “for babies.” Jason Rubin has 7 year old focus testers telling him Jak and Daxter is great, but it’s probably targeted at a younger audience.

So the movers and shakers at Krome start freaking out. They were already planning on competing with established franchises for the mass market, but then they find out their competitors aren’t even reaching the mass market anymore. Imagine working for two years on a competitor to Coca-Cola, hoping to carve out a slice of their market, only to find out you’re actually going to compete for a slice of the market controlled by Mello Yello.

In their panic, they fuck up their main character’s face. They demand he have a single giant eyeball with two pupils and two mouths that go under his ears. They make a trailer that features silhouettes of competing platformer mascots quivering in full-body casts. They create a marketing perception that has almost nothing to do with a game about collecting gears, throwing boomerangs at lizards, and being escorted past mean sharks by a seahorse.

Ty the Tasmanian Tiger isn’t the least edgy 3D platformer, by any means. As a matter of fact, it’s the third least edgy after Croc: Legend of the Gobbos and Mort the Chicken.

Game #24: NotGTAV, Not Games, 2015

I’m furious with myself for not having made this game. NotGTAV’s stand-out quality is it’s charm. A capella sound and music, goofy voice lines, ridiculous situations, it’s easily my favorite version of Snake.

Coffee Break: Forza Motorsport 6, Turn 10, 2015

(This was not technically on my stack of shame because I played it when a friend rented it)

After a lifetime of Gran Turismo loyalty, playing Forza 6 made me feel how I imagine East German defectors felt. I knew there were problems, but I could never have known how good the other side had it. I found myself marveling at the fact that wet races featured actual puddles. Actual spots where water stood on the road where your car would hydroplane. Gran Turismo games instantly felt feature-bare, more an exercise in the manipulation of physics parameters than actual driving. The fact that there is a game where you can adjust the camber angle on the front left tire of a Renault Clio is a beautiful thing. It is a beautiful artifact that engineers should buy. But I’m honestly considering switching from Playstation to Xbox over Forza.

0 notes

Text

Stanley Parable - I Learned to Obey

Game #14: The Stanley Parable, Galactic Cafe, 2013

When I was in high school, I used to throw away forks, at lunch. I started by throwing away my own, then I started taking the forks from my nearby friends, and then from about 40 other students in the lunch room. They’d all process past me and drop their forks on my tray. 9 years of American public school was 9 years of bullying, 9 years of arbitrary rules, 9 years of my every attempt to affect my surroundings getting mired in the syrupy muck of bureaucracy. The thundering crash of forks into the garbage can was my adolescent (in every sense of the word) protest. It was my rage, like a cornered angry child, too busy listening to Rob Zombie to think about why it’s doing what it’s doing. I felt like I was the Yoko Ono of my school. I don’t handle authority well. So I begin playing The Stanley Parable. I knee jerk reaction is to say no to everything I’m told. The game gets the message quickly, and starts sending one of it’s own. It tells me in no uncertain terms, that I’m killing myself, I’m incapable of refusing requests, I’m refusing to acknowledge my surroundings, and that my entire life is shallow play-acting. It’s a pretty intense 15 minutes. I decide that I’m not going to play a game that clearly doesn’t want to be played. Alt+tab, right click, close. I want to make one thing clear though. Although I might never play it again, my quarter-hour in The Stanley Parable will stand as one of the most profound gaming experiences I’ve ever had. It made me feel sick inside. I couldn’t stop thinking about it. Had I really rebelled? Had I simply done exactly as I was instructed? Would the acerbic William Pugh (follow him on twitter, you won’t regret it) approve of my playthrough? Would he lambaste me? Would he even have an opinion? Had I learned the lesson the game intended or simply stomped off like an impudent child? Would I feel differently if I had experienced more of the game, perhaps learned to accept the authority of the narrator? Had I done the gaming equivalent of skipping straight to the desert, and then complained that the meal was too sweet?

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Coffee Break - A Four Dichotomy Method of Categorizing Games

RPG. A familiar initialization which effectively evokes a set of mechanics and attributes but does not, itself, have very much meaning. Before learning that role playing games were about maintaining large inventories, strategic application of skill points, and carefully calculated combat scenarios, one might think that the goal of an RPG is to successfully embody another character, accurately predicting decisions that character would make. Platform, Adventure and Puzzle games have similar semantic shortcomings.Inspired by the Myers Briggs personality profile, I have identified four dichotomies in which games tend to be either one way or the other. I’ve not yet identified any other useful dichotomies which are sufficiently broad in their application, or in which the two sides of the dichotomy have sufficient mutual exclusivity. The four dichotomies I have identified are informative as to the experience the player will have. The dichotomies are thus: Contemplative – Reactive

This is dependent on how much time the player has to make decisions. At the far ends of the spectrum, we have the highly reactive Starcraft II, which requires players to make decisions with blinding speed in response to the choices of the opponent. On the flip side is Day of the Tentacle, where there are no bounds whatsoever on how long you have to make a decision in almost all cases.

Avatar – Direct

Games are Avatar games if there is an object on screen to represent the player. If they take action by directly manipulating objects, characters, text or images with the mouse, key presses, buttons etc., it is a direct game. Direct games are often called “God’s-eye-view” games. In general, it is on this dichotomy that games are the most divergent. Consider whether the character has an identity beyond the player, as not all objects the player is able to move or manipulate are necessarily avatars.

Enemies – Obstacles

This depends on whether the player must overcome the environment/circumstances, or enemies/other players. Games in which players must overcome obstacles are approached differently by the player and designer alike. Those games which are obstacle focused but which still contain enemies often have enemies with predictable movement patterns, and which are not difficult to defeat, and are thus more like obstacles than enemies. As there are many games which focus tightly on combat with enemies, it is safe to be strict with this categorization.

A game like Crash Bandicoot might seem ambiguous, but I think it falls firmly in the Obstacle category. Most of the enemy characters in Crash could easily be replaced with props with similar behavior. Most do not respond to Crash’s actions (other than poofing out of existence when attacked). The player doesn’t have to engage a different kind of thinking than they do when avoiding pitfalls, booby traps, etc.

Unfolding – Situational

In games where the player starts with a small set of tools, items, mechanics, (items, abilities, units, changes to the avatar etc.) and slowly accumulates them over time, the game is Unfolding. This is especially true if the player has the ability to make alterations and tune things at their will. In Situational games, there’s more focus on changing circumstances around they player, while the player themselves has more or less the same toolset throughout the game.

This spectrum is as much about time as it is about flexibility. For instance, in platformers, players often pick up power ups, but item use is dependent largely upon the level, and they might return to their initial state at any moment, so there’s little correlation between the nature of gameplay and time. Skyrim however has a strong correlation, with more and more items, abilities, and alterations to the avatar accumulated over time. A game like Team Fortress 2 is close to the middle of this spectrum, but falls on the side of Situational because in theory all stat changes that one might achieve through time investment can be achieved immediately, and there’s a huge amount of emphasis on different types of situations.

From these four dichotomies, we get the following sixteen categories:

CAES – Stealth Game (Metal Gear Solid, Splinter Cell)

CAET – Non-Time-Intensive Combat (Final Fantasy, Phantasy Star)

CAOS – Story Adventure (Monkey Island, L.A. Noire, Deadly Premonition)

CAOT – Minecraft-Like (Minecraft, Lego Creator)

CDES – Non-Time-Intensive Strategy (Civ Series, Age of Wonders)

CDEU – Conflict Simulation (Football Manager, Magic)

CDOS – Pure Puzzle (Crayon Physics, Sudoku, World of Goo)

CDOU – Simulation (Sim City, Flight Simulator)

RAES – Combat (Streets of Rage, Tekken, Halo)

RAEU – Strategic Adventure (Mass Effect, Skyrim, DotA)

RAOS – Obstacle Course (Sonic, Spyro, Rayman)

RAOU – Fast Vehicle Sim (Gran Turismo, Need for Speed, Hydro Thunder)

RDES – Tower Defense (Unstoppable Gorg)

RDEU – Fast Strategy (Starcraft, Warcraft)

RDOS – Fast Puzzles (Tetris, Audiosurf, Chime)

RDOU – Puzzle Quest-Like (Puzzle Quest)

It is true that some categories, RDOT for instance, are exceptionally rare. It is also true that certain Myers-Briggs personality types only describe 1 percent of the population. That is the nature of such a system. It is also true that certain games will appear to be equally described by both sides of a dichotomy. Thankfully, games are rarely simple enough to fit into one category or another without some argument being present. Still, in these cases we should look to which behavior dominates gameplay. I would argue that Call of Duty, despite the ability of the player to customize characters, is a static game because the majority of players will simply pick one of the available classes.

0 notes

Text

Dishonored: the Other Big-Eyed Girl Rescuing Simulator

Game #13: Dishonored, Arkane Studios, 2012

So first things first, every game since Half-Life has been Half-Life. Four or Five times a year, Half-Life comes out, they review Half-Life, they buy Half-Life, they play Half-Life, they put Half-Life on the shelf and wait for the next Half-Life to come out. Bioshock was half life. Spec Ops is Half Life. In a certain light, the Call of Duty campaigns are all Half-Life. Shoot the guns, experience the story, Half-Life. Dishonored is also Half-Life. That makes this an article about Half-Life. This isn’t a bad thing, not at all. Every pop song is Sugar, Sugar, and it’s fine. Half-Life is a good game. It’s not a bad thing for a game to be Half-Life. Playing Assassin’s Creed III--Which is Tomb Raider--left me hungry for a good stealth experience. That game is a sluggish brawler that, from time to time, demands the player to be stealthy, while giving them no tools whatever to be stealthy.

Also it might be bad that every time I play a game I like I end up rambling about a game I hate.

Dishonored is famous for the fact that it can be beaten without killing anyone. The more you kill, the more chaos you create. Brute force your way through the levels, and you’ll find them swarming with plague addled “weepers”, aggressive rats, and slightly sadder NPC dialogue. If you want the good ending, you have to play the game as the lullaby simulator it wants to be.

This does not necessarily mean the game isn’t violent.

I hesitate to talk about violence in games, lest I get lumped in with Fox News’ Moral Panic Brigade. People talk about how the ubiquity of violence in games is bad for kids, or a sign of an immature medium, or just the nature of video games, but nobody talks about how weird it is. A game engine is like a lump of wet clay; you can make almost anything with it. For instance, you can make a game where you’re in the army and you click on people’s heads, or where you’re in space and you click on people’s heads, or even in an underwater city in a libertarian paradise gone horribly wrong and your only way to escape is by clicking on people’s heads.

I’ve been clamoring for a good stealth experience. Dishonored promises to give me that. I’ve been clamoring for a game which doesn’t force me to take on the role of mass murderer. Dishonored promises to give me that too. Okay, AAA game, I smugly think, show me what Half-Life looks like without mandatory head-clicking.

Well, the game did show me. It showed me good. It showed me with it’s charming oil-painting like art style. It showed me with it’s impeccable stealth. It showed me with it’s expert level design, it’s holy-crap-awesome upgrades, and the subtle but powerful interactive music.

This might be the most fun AAA game I’ve ever played. I just love doing the thing! I love the swooping in and knocking people out, I love collecting all the whatsits, I love reading the stupid books and notes that I know are dumb design-wise but I don’t care they’re so fascinating. I love the Jules Verne technology and the victorian fashion. I love how the non-lethal option emerges throughout the mission. I love how dealing with enemies has more to do with where I put myself than how well I aim my mouse. I love how stealth is just the perfect amount of tricky to pull off, I love watching and waiting for the right moment, I love knowing that if I were just a little bit lazier, the game would turn into just another big dumb brawler, but my decisions and my efforts make stealth viable. I love how the game could almost be interpreted as an open letter to other game designers.

I am Bob Ross. I am the human Quaalude.

We’re just gonna put some happy little unconscious guards right here. It’ll be our little secret.

It does still have a lot of the same problems all the other Half-Life’s have. Is there some ludo-narrative dissonance in the lifelong bodyguard of a child becoming a magical cyborg assassin? A bit. Is the mixture of open world gameplay and linear narrative not extremely elegant? Maybe. Is the game, in spite of it’s reputation as the non-violent action game, still about as gruesome as most 80s horror films? Well, yes. But calling out a AAA game for these problems is like calling out a World’s Strongest Man competitor for using steroids. It’s far more productive to talk about the societal forces that caused it than to admonish the individual.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Super Mario 64: Everything is Cars

Game #12: Super Mario 64, Nintendo, 1996

My experience with Mario 64 has taught me that I grew up with the Porsche 911 of game controllers. Generation after generation of this well balanced icon has remained virtually unchanged. Indeed the most common criticism leveled against them is a failure to innovate, a tendency to rest on their laurels, a history defined by trying to find ways to compensate for a stubbornly unchanging design decision (whether it’s putting the engine at the back or the joysticks on the bottom). We’ll call the DS4 the advent of airbags.

James May, pretending two different Porche 911′s are different Dual Shock controllers.

The NUS-005, aka the N64 controller, was hugely innovative and visually striking, it’s silhouette is inseparable from the era in which it was introduced. It’s three perplexing handles, it’s joystick which is simultaneously stiff and loose, which both digs into, painfully, and slips out from under, your thumb, and it’s... creative smattering of buttons. It’s more like the Lamborghini Countach. It’s an experiment we look back on fondly, which dedicated enthusiasts own, but anyone who’s being honest with themselves would really rather not operate.

James May,sitting in a Lamborghini Countach, pretending it’s an N64 controller.

This posturing, haphazard Italian supercar is the tool I was given to traverse the miles upon miles of untested game design theory that is Mario 64. For me, the bubble cannons of Bob-omb Battlefield are effectively a timed drain on my health points. The climb up the mountain to face King Bob-omb feels like trying to thread 20 needles that are constantly moving using only a robot arm which I can only see through a video feed on a two-second delay.

I love 3D platformers. They are my favorite games. Every time I see a new shooter IP announced, a little fire burns in my heart, as I simultaneously curse the narrow-mindedness of game publishers, and pine for a time when their narrow-mindedness was focused on games I like. I have forgiven some heinous controls to collect another whatsit and unlock a keyframed cutscene. I have unearthed unloved forgotten games like Scaler, Croc, and Gex. I can look you right in the eyes and tell you I found them to be playable. The fact that Mario 64 was on my stack of shame at all is empirically bonkers.

So imagine my dismay when this, the alleged one, the alleged original, the alleged miggity mac daddy of 3D platformers had me defeated so quickly. It was like looking at the source material on which your favorite movie was based, and finding that the author switched tenses mid-sentence. A classic case of don’t meet your heroes.

I was more than prepared at this point to leave this game on my shelf forever. After all, I have Mario Galaxy and Mario Galaxy 2 on my shelf whenever I want them. Not to mention Super Mario 3D world, Mario Sunshine, every Sly, Crash, Ratchet and Clank, and Spyro game a 3D platformer obsessed nerd could ever ask for. For whatever reason, I left it in my N64. Perhaps there were no other N64 games that interested me at the time. Perhaps I wanted it to be visible to guests. Perhaps I was simply lazy. But it stayed there. And day after day, I’d sit in my living room, chat with my house mates, and I’d switch on Mario 64 and fiddle with the controller.

Yahoo! Yahoo! Yahoo!, came the cheerful cries. They propagated throughout the room from the tiny speakers on the squat cathode ray tube television we got to more authentically experience old games. I learned to take pleasure in stringing together crouch jumps. I learned to do them forward, backward, sideways, and in circles. My fiddling lazily migrated into the levels. I found suddenly I was able to make my way across Bob-omb without getting hit by cannons. I knew exactly which direction to hold to cross the narrow bridge in Thwomp’s Fortress. After a while using four dedicated buttons to control the camera had a strange logic to it.

Suddenly, I only needed five more stars to get through the door. “Yes, I know this game is bad,” I found myself saying to my roommate, “but I like it.”

At 57 stars, there was no more magic. the last seven stars had been feats of patience my psyche had never experienced. I had run out of curiosity and was now burning pure determination. It wasn’t to last long. I found myself talking about the game in a distinctly funerary tone. “I’ve been changed by it,” I would say, “and I’ll always be grateful for the time I’ve had with it.”

After my eulogy, I picked it up once more. I came to the precipice of a star, when an enemy knocked me back onto a slope. I jumped and jumped, desperate to find some purchase on the terrain. My lack of knowledge of the map meant than when I finally did jump, it caused me to overshoot the only patch of earth that would have stopped my fall.

I am at this moment, unsure of whether or not I should agree with Jeremy.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Coffee Break: It's time to play the Steam Queue drinking game!

1. Zombies

2. Post-apocalyptic

3. Waifu

4. "FPS Meets Minecraft" with overwhelmingly negative reviews

5. Sarcastic Sim Bandwagon Simulator twenty-LOL-teen

6. Sequel to Realistic Military FPS franchise that fell by the wayside

7. We're hoping you're so starved for colors that you'll buy our game, which looks like a tornado ripped through the Crayola factory

8. Free 2 pay 2 win

9. Hey, remember Quake? We did. We remembered it really hard.

10. "FPS Meets Minecraft" but you don't actually build things

11. Arg'olious, r'ise o'f 'a'p''o's't'r'''o'p'h'e'

12. Jargon-based A.C.R.O.N.Y.M with Buzzword-like elements set in a post-cliche world featuring music by Slavish Devotion to Trends and an future-retro-futuristic-retroactive-futurious-retronic-ford futura-retractable-untraceable-insatiable art style.

13. Seriously how many people failed to google "FPS Meets Minecraft" before they opened Unity?

14. Minecraft.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ibb & Obb: Adventure of the Sentient Pastel Christmas Thimbles

Game #11: Ibb & Obb, Sparpweed Games, 2013

Comparison to Portal 2 is inevitable when talking about a physics based co-op puzzle game starring two creatures who’s only essential difference is color and height. Those who know me know that I’m, at this moment, fighting very hard to keep this from becoming an article about Portal 2, so I’ll sum it up like this: Portal 2 first created itself, then the universe, and then everybody in it, as a sort of tribute to the concept of excellence. NOW THEN. Ibb & Obb has a lot of what I want to call “Portal Appeal”. It doesn’t give the user as much agency, but it does place them in a world largely governed by rewritten physics. As the puzzles get more complicated, players learn to exploit Ibb & Obb’s freaky gravity to do things like this:

Portal 2′s puzzles do give the players more agency, but Ibb & Obb illustrates the cost of that agency. The mechanics of Portal 2 make it easy to be inconsiderate without intending to or to become seized with anxiety. It’s all too easy to over-write someone else’s portal, or accidentally send them falling to their death. I think it helps that the game is phenomenally mellow on top of that. I played this game and Portal 2 with my boyfriend, Dave. Whereas Portal 2 elicited precise, occasionally tense conversations of where to put what, Ibb & Obb had us laughing. Now and then Dave would gleefully observe some of the game’s subtleties. “Look, the little characters look at each other!” he’d say, or, “Did you notice the city changing colors?”

Preeeeeeeettttyyyyyyyyyy.

Visually it’s like Mario Brothers meets Yellow Submarine meets PAAS egg dye kit. And I like that, because in my day...

The music, like the landscape, is subtle and abstract (the digital shapes are abstractions of a landscape, and synthesizers are abstractions of physical instruments.) Tracks and motifs fade in and out as the duo progresses through the levels, which don’t really end. They are merely interrupted by a pleasing and symbolic fade in and out of nighttime as the players run past a scoreboard. Play Ibb & Obb, solve puzzles, keep your boyfriend.

0 notes

Text

Luftrausers: Oh You Shooty Shooty Plane Plane, Shooty Shooty Plane Plane, We Love You

Game #10: Luftrausers, Vlambeer, 2014

There’s something transfixing about the undulations of a mass of starlings, an ominous cloud, both heavy and graceful, acting with a singular will. And in the backs of our minds we know we’re looking at thousands of individual birds, each of them in their own right a miracle. There are moments when the world stops, and you consider the infinitely downward tumbling complexity of even a single phenomenon, such as a starling flock. The mass, the individual, the feathers, the cells, DNA, particles, all comprised of their own worlds worthy of a lifetime of devotion. Allowing your mind to follow this pattern of thought can stop time and induce vertigo. Suddenly the world seems impossibly huge, all because of a moment’s contemplation on the diminutive, modest starling.

But what if one of the starlings had a lazer beam?

Tweet, tweet, tweedle kasplow!

Luftrausers is a basplode in which the kerblooey splats upon themes of pew-pew-pew, while avoiding some of pitfalls of tshik-tshik fa-dusshhhhhhh. When I’m playing it, I make the following face:

Like many indie games, Luftrausers uses the artistic tropes of 1980s arcade games extensively. In many ways, it attempts to exist outside the linear progression of game visuals. I appreciated that Luftrausers didn’t confine itself to what might have been possible on dusty Sega hardware. At times though, the game had done such a good job of selling itself as 16-bit, the sudden inclusion of modern elements took me out of the game. Luftrausers really doesn’t belong to any one time period, though. It’s a game from 2014 meant to look like a game from the 80s the subject of which is a distant future in which 1940s retro has come back with an earth shattering vengeance.

The score for Luftrausers is a real gem among indie game scores. At first though, I was a bit disappointed. The music struck me as being plain techno, an ill-fitting accompaniment to the eclecticism of the visuals and gameplay. It wasn’t long before I saw how wrong I was. If you’re good at games, you’ll figure out what I’m talking about even quicker. It doesn’t take long for the four on the floor chippy beat to be augmented by lush orchestral textures, giving a sudden do-or-die feeling to the action. But when you level up, and earn additional features for your plane, that’s when the score really begins to shine.

The content of the music seems to depend largely on what parts your plane is equipped with at that moment. When I switched out my weapon for a laser beam, the four-on-the-floor beat was replaced with a heavier, half-time feel, which is music’s way of telling you, “you are the god damn Terminator, now go terminate.” Luftrauser’s gameplay isn’t exactly what I was expecting either. It’s a bit like Moon Lander meets Resogun. The physics feel somehow both slippery and within my control, letting me elegantly float through clouds of bullets. The fact that you can only fire in the direction you’re flying sets up a very effective risk reward dynamic at a very fundamental level. You can shoot at the battleships on the water, but only if you’re prepared to pull up after a long freefall. This game has all the instant yes, yes, I’m such a badass of Crazy Taxi, but there’s also the feeling that I’ve just scratched the surface, as there’s a multitude of power-ups to unlock and not insignificant achievements guarding them. “Your word is, Luftrausers.” “Can you use it in a sentence, please?” “Yes. Ahem, ‘I like Luftrausers.’”

#too many games#steam sales#gaben#stack of shame#stackofshame#luftrausers#interactive music#video game music#review

1 note

·

View note

Text

Kotor II: I am losing momentum way faster than I thought I would.

Game #9: Star Wars, Knights of the Old Republic II, Obsidian Entertainment, 2004 I tend to get overexcited about new ideas. As you can imagine, that initial overexcitement translates into AMAZING FOLLOW-THROUGH and not rapid burnout.

Oh my god. Maybe I can segue from this into why I don’t play RPGs. Am I actually gonna write this thing? This could happen people. So... a game like Kotor II does a really good job of offering me a world bursting with possibilities, where my influence is tangible and my choices meaningful. I start to imagine all the people I’m about to meet, the challenges I’m about to face, the intricate storyline which I will not just absorb but actually, in some ways, determine through my actions? Alright, let’s do this! I just have to pick a name...

There’s a phenomenon called choice paralysis. I feel like this affects me more than most people. All options just tend to seem ‘fine’. At the grocery store, on Netflix, on god damn Steam obviously, and most definitely when trying to decide what class to be. And I never feel like I’m making an informed decision in these games anyway because I’ve never gotten far enough in one to see the consequences of my initial choice play out.

My indecision presents itself most clearly in my save files.

Kotor II lets you know right away that you’re in for the usual Obsidian awesomeness:

This is the first instance of pathfinding in the game.

Cheap shots aside, I really like the opening tutorial. Honestly I think I could play a whole game about being an astro-droid. Repairing ships, hacking systems, leaving what turns out to be the main character to die, but sadly I don’t think such a game would be flashy enough. Plus, there are some who find Star Wars’ portrayal of robots to be in poor taste.

Kotor II, it’s not you, it’s me. You have a way of bringing out the worst in my defeatism. Asking me to comprehend this world is like asking someone to play their irresponsibly large pile of unplayed games. I’m either going to get bogged down in minutia or feel like I’m short changing myself. Kotor II, do you think you can ever forgive me?

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fallout: New Vegas: I don't want to shoot the dog, I just wanna know if the game will let me

Game #8: Fallout: New Vegas, Obsidian Entertainment, 2010

Americans are obsessed with the end of the world. It's the only explanation. I think some of them want the collapse to come, expecting perhaps the same feeling of relief that accompanies a canceled dinner party or a snow day. Or maybe it's because a cataclysm was the precursor to our country's founding.

The phrase 'post-apocalyptic' has a way of draining me the instant I see it. In that way it's similar to 'results-oriented' or 'barcade'. I think it's because I don't like the feeling that I'm expected to be immediately enticed. And because I don't necessarily see the appeal of the end times. I find it difficult to engage in the fantasy because I seldom fantasize about strife, suffering, and starvation. At least I think it's a fantasy. The game begins with my resurrection from (near) death, I'm on a quest to find out what went wrong while delivering the plot device, and absolutely everyone and everything is my business. I'm a lone figure with messianic overtones in a lawless wasteland where good folks just wanna run their Mad Max theme restaurants in peace.

The Casino is called "Gomorrah". Told you this game is the Bible.

The first action I am allowed to take is entering my avatar's name. I considered many options before making my final selection.

But then I decided I ought to be taking this seriously. I only have an hour with this game, I may as well let myself get swept up in the fantasy. If I am to become the savior of New Vegas, I must have a name befitting the role.

I then have the opportunity to make tweaks to my avatar's appearance.

Billy Casino man is through being cool.

I explore the home of the doctor who revived me, steal all three of his clipboards and take my leave. Next I learn to shoot guns from a nice woman who's saloon I relieve of it's pool balls.

I had a lot of trouble hitting the bottles, though I was able to develop a strategy.

I have mixed feelings about the "go anywhere, do anything". I like the idea of being trusted to play the game, and figure out my own way of doing things, and not being penalized just because my solution to a given problem is not the solution the game wants. I like the idea of an avatar and an environment that evolves over time based on the way I've chosen to play.

There's also a certain elegance to the way the world of Fallout: New Vegas is built. I like the idea of building a space and populating it with simulacra. I like the idea that your experience as the player is the gestalt of a multitude of systems which appear to govern themselves. Even though games like this put you in a messianic role, there's still a sense that the towns and people and even society as a whole would carry on if you weren't there, a sense which I don't recall in Parappa the Rapper.

I think Fallout: Old Skokie is an impressive game, but it's not for me for three reasons.

1. I'm cranky.

2. I find open world RPG games intimidating. The number of quests you can accumulate in the space of a few minutes, the number of objects you deal with, the stats, the attacks, the glut of information, it is impressive and the mark of quality, no doubt. It just makes me tired.

3. I possess a prejudice against it's type of story premise.

The phrase "you can't please everybody" is about me.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Race '07: You ever feel kind of weird sometimes?

Game #7: Race '07, SimBin, 2007

Because I feel really weird. I slept for I think 17 hours today. I was good for like 6 hours after I woke up, and then I started to get these weird waves of lightheadedness, diziness, and lightning fast disconnected strings of thought.

In many ways, Race '07 feels like Gran Turismo. Except when they got to the part where they added the unique dumb feature every version Gran Turismo game has that just gets in the way and makes the game a red hot pain in the ass, they apparently said, "hey, why don't we not?" Then something amazing happened. They actually decided not to.

It's like the world is when you watch footage of a completely immobile landscape and somehow you can still tell it was sped up. That's what my eyeballs feel like.

What's that? You've never heard of the bullshit feature in every Gran Turismo that makes everything worse for no reason? Let me tell you about some of them.

Gran Turismo 2: The UI is nonsense. All the dealerships are arbitrarily grouped into four "cities" so it takes forever to find what you're looking for. Also the UI has an annoying tendency to direct you to replays of whatever race you just ran. They take forever to load, and the "watch replay" option is peppered everywhere, just waiting for you to click it by accident. Yeah, they ask "are you sure?" when you skip a replay, but they don't say shit when you start one and your PS1 shakes itself off your TV trying to load it.

Gran Turismo 3: Psychotic A.I. that rams you into walls, and a gutted car roster.

Gran Turismo 4: Informs you after you spend 400,000,000,0,0000000,0000,0!!!0000 Fakemoney on a car that it can only be raced on two courses, turns your car into Gary the snail for nine hours if your front end touches something during rally races.

Gran Turismo PSP: Wanna buy a Honda Civic? Great! Just wait for Honda to be one of the four random dealerships you can buy from. They refresh every... I can't remember, how long does it take for your time to feel wasted? That long. *smiley face*

Gran Turismo 5: Wanna buy a Honda Civic? Great! Just level up, because we introduced levels, I don't know why but we did it, yes, that's right sir against all reason and design sense we put levels in Gran Turismo, so just level up until you can buy a Civic. It only takes... I can't remember, how long does it take for your time to feel wasted?

All of the above: License tests with paper thin tolerances you have to pass before you can run certain races. Earning them is kind of like leveling up. Except slightly less arbitrary. So why you'd want license tests AND a level system IS FUCKING BEYOND ME sorry I'm still mad about that. And every time you start a new Gran Turismo game, you will spend so much time crawling up the ladder of Daihatsu Grocery Carts by the time you get in an actual racing car you'll have forgotten how to take a corner.

I feel really weird you guys.

So why did I keep buying Gran Turismo games? Perfectly valid question, and the answer is this: I like Playstation controllers, and I like cars, and therefore Polyphony has me by the balls. I used to be able to defend Gran Turismo to Forza players and actually feel like I had an argument. But ten years later, I know exactly how George W. Bush's constituency feels. Or at least how they should feel.

So I load Race '07, and I'm like,

"Ahem, um, I'd like to drive a car please?"

"That's what we do."

"So how many hours of bullshit am I going to have to go through?"

"Sir?"

"You know, content I paid for locked behind what should be a tutorial, that kind of thing."

"Sir this is a racing game."

"Well yeah I know but... Wait, can I drive a car now?"

"Wouldn't be much of a racing game if you couldn't."

"I mean a fast one, a fast car."

"We don't have slow ones."

"Wait a minute, I've seen this scam before. Lemme guess, you'll let me drive one or two of your cars but if I want the whole selection I have to jump through the hoops, right?"

"Sir if you want the whole selection, you click 'Select car'."

"I probably shouldn't be driving right now. I'm so god damn dizzy, I don't know why."

I pick a car and a course at random. The car is fast, and it actually feels fast. There's a little heads up display letting me know when a tight corner is coming up. The game's physics are sacrificing reality to help me hold traction in corners, but I don't care. You know why? Because it's fun. It's funnnnn-na.

In a world where you either have Gran Turismo, "Life sucks, play our fucking game you shit." or Mario Kart, "Actually driving is too hard, so we made a button that automatically lets you drift perfectly. After that, races are a dice roll," it's really really nice to discover a reasonable compromise that isn't no-practice-mode-for-some-god-damn-reason-also-this-was-built-on-a-rally-game-engine-so-hope-you-enjoy-getting-dicked-by-corners GRID.

I'm looking at my stream of consciousness rage about Gran Turismo, and I'm reminded of a certain reality show called Intervention. People see the people they love dearly throwing away their potential, making stupid self destructive decisions that they, as non-addicts, just don't understand. I guess that means in spite of everything, I still love Gran Turismo. (I also love Mario Kart. Sorry you got dragged into this Karty.)

Race '07 is less full featured than Gran Turismo, but as I've discussed most of those features feel like obstacles. It doesn't have as many cars, but they're all at the same resolution (oh yeah, add that to the bullshit list on GT5) and they're all available at the start. As Dara O'Briain would say, "I unlocked it in the shop with my credit card"

Finally. Finally, finally, finally. We have a game that takes racing seriously but isn't an exercise in self-flagellation. And it's called Speed Freaks. Wait... is that right? Man, you ever feel weird?

1 note

·

View note