#<- This is a Strong Woman trope subversion on purpose. She wants to be the trope. She can't do this she's ~17

Text

cooing over my own ocs part 282737. listening to songs abt teenagers like woaah ..... they're teenagers

#vwoop.noises#They pair off nicely. In more ways than just their respective romances#Like when you can mix things and you get bonuses .. in video games... But that's just how people are they should draw different things out#But. agh. Max and Ethan... My little guys#Max is depressed and has will to live imparted onto him via an obligation to others. Ethan does not#Ethan fully believes everyone is better off w/o him#Together they are... A Force. thats for sure#+ Matt who has more interesting things wrong with him but self preservation isn't one of them#They are a trio before Max dates Matt and it goes spectacularly wrong.#Anywyas. They're so teenaged#Bridge burners unite#(Chrys gets in on the nihilism but she internalizes it more. She has 2 be a rock for the friend group (this is a cry for help). She can -#level w Max on this front)#<- This is a Strong Woman trope subversion on purpose. She wants to be the trope. She can't do this she's ~17#Forgets to let herself be a person first. Etc#But she does have more self preservation instincts than whatever they get up. She doesn't socially self destruct she does this on her own

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi! How are you doing? Sorry to bother you, but i dont know many scottish people and idk who to talk to about this book I found on audible. It's called Imogène, by french author Charles Exbrayat. Do you know him /the book? I've started reading it but I had to pause because, while being sold as a "humorous spy story" I find the protagonist, a "very proudly scottish" woman, to be... an offensive caricature? Like she acts like a fool, honestly. This book contains some interesting points about sexism (it was published in 1959), and ridiculous british habits (such as employees forced to give money for princess anna's birthday or being socially scorned). I'm sure the shared dislike / distrust the protagonist and her british colleagues feel are (were?) realistic. But she is so extra, and the story keeps telling how lonely she is, even after working 20 years in london. She has No friends, most acquitances dont talk to her for various motivations, her bosses hates her ... idk I feel this book is actually mocking scottish people? Or scottish women??? I was SO there for a "strong woman protagonist who gives cutting remarks to her boss or peers", but this looks wrong. Idk. I didnt know whom ask for inputs. Maybe i'm reading too much into it. Feel free to ignore this mega rant. Have a good day!

I think cultural and historical context and time of publication-- which was almost 70 years ago --are important factors to take into consideration when we look at fiction through our current expectations.

I can’t speak to the book as I’ve never read it, but speaking as a Scots woman who worked for an English publishing house for a while, being made to feel alienated by my boss and others due to being Scottish was unfortunately still something going on in 2011.

I’d get lots of “Oh but you sound so eloquent” remarks regarding my thinned-out accent (something I did on purpose to avoid being told to “speak properly” which was also something I heard a lot in school if I ever used my native Scots language instead of “Queen’s English.”) and one time my boss referred to me as “their civilized Scot” to an American author, whose Scottish romance book I was supposed to be fixing the dialogue on.

The phrasing was along the lines of, “Don’t worry, you’ll be able to understand her. Joy is our civilized Scot.”

The author laughed and made another derogatory comment about how they just loved Scottish accents even if it was unintelligible a lot of the time. I kept my mouth shut because I didn't want to lose my first career job.

I kept my mouth shut a lot in that job.

In that regard I could very well empathize with the character being lonely and not engaging with anyone, even after 20 years.

The proud Scottish woman can be a bit of a caricature, but that doesn't necessarily mean it is intended as mocking.

Again, cultural/historical context matters.

I wasn’t alive in 1959, but I know there was a lot of Scottish media about the time that leaned into the stubbornness and pride of Scots women both for humor and to make societal commentary on the fact that women were strong and more independent than they’d ever been following two world two and a lot of men weren’t happy about it and wanted them to go back into their boxes. As a result the mouthy, proud Scots woman became a mockable caricature that turned women into shrill, over proud scolds.

Get back in your box or we’ll make fun of you, basically.

So is this book being mocking, or is it employing popular tropes of the time, knowing that audience will understand what it means and that the female protagonist is being subversive despite what others expect from her?

I can’t say. Again, haven’t read it. It could be utter dogshit and making total fun of my culture. But I do think when looking at older media we need to put our thinking caps on and think, “How would the audience of the time, 1959, have viewed and engaged with this?”

Expecting a “strong female protagonist” as we know it from media today isn’t going to work with media that’s almost 70 years old.

Hell, the “strong woman protagonist” wasn’t even something any piece of media could agree on when I was growing up in the 90s.

Times change. Literary tropes and preferences change. It helps to keep that in mind.

253 notes

·

View notes

Text

Oh my fucking god. This episode… I really shouldn’t go there because this is reading far too much into most likely nothing at all but here goes. * put clown shoes on *

1. Both Ted and Rebecca wearing red in this episode (red string anyone?). Ted at the beginning, Rebecca at the end.

2. Keeley implying both women might see red flags as giant green flags. Rebecca said it was nice to be taken care of for once when Rupert wooed her. But he turned out to be a piece of shit. I couldn’t help but see that pattern repeating with the Dutch Man. He was objectively icky. Yet she was immediately swayed. His approach was too strong. Mistaking his daughter’s ankle for a woman’s… 🤮 Give me a break. I think back to that scene in 3x02 about Rupert seducing Rebecca. Interesting that it’s now the second time they are both talking about this. I didn't like how forward Dutch Guy was with her and I think she would be committing the same mistake a second time:

Keeley: It's a fine line between stalking and romance.

Rebecca: Mmm. And after about six weeks of that, he asked me out again. And I said yes without any hesitation. Because by that point… I just felt so lucky because he wanted me. He made me feel special. Chosen.

I really hope that dude is Derik. 😂 I just find it interesting that just after talking about him she mentions how many red flags she has ignored in the past. The implication might be that she’s still doing it. We might see him again and I see the purpose of that. I hope he goes to London to find her. That’s stalkish. And she said it herself: What is shiny tarnishes. Something as bold and brash is not meant to last.

In a similar vein, it’s interesting to have Sense and Sensibility feature into this. Which is famously about how choosing passion over kindness and consistency in a partner will only lead to suffering…… Rebecca, Keeley, write this down 😂

But what do I know? This show has a gift for treading a fine line between traditional romcom tropes and subversion of said tropes. So I don’t know anything 😅

3. OMG!!! The Lasso Way!!! “Slowly building a club-wide culture of trust and support through thousands of imperceptible moments all leading to their inevitable conclusion.” What the fuck???? This is TedBecca in a freaking nutshell. STOP IT JASON!! You are killing me right now!!!

4. Interesting that Tish mentioned the Japanese tradition of Kintsugi and now Ted is mentioning the Japanese version of the Red thread of fate. Which is about true love btw. He officially referred to soulmates in the romantic sense between a man and a woman. Not platonic. Just putting this out there.

5. I can’t help but think back to Ted’s speech about romcommunism. Nothing is working out the way we expected, but it will work out.

🤡😂

50 notes

·

View notes

Note

You're right, George is more than his abs, but why would he need to be nearly naked the entire movie though? "some characters briefly objectify George but the *film* does not treat George as an object." Ok, but why THIS distinction never made when talking about the male gaze? What I mean is, how is objectifying George any less sexist than Megan Fox's character in Transformers? They both have character beyond looks and both subvert gender tropes.

Why would he need to be nearly naked the entire movie though?

It is obtuse of you to pretend that George of the Jungle is not clearly a children’s comedy interpretation of Tarzan. That’s it. That’s the joke. Me Tarzan, You Jane. Me Handsome Strong Jungle Man, You Smart City Lady. When George makes it to the city he looks pretty darn good in Armani and happily wears a dress because it’s comfortable. When he’s in the jungle he’s dressed like Tarzan because this movie is based on a cartoon that is a children’s comedy interpretation of Tarzan.

It’s not like there’s a rash of criticism of Blue Crush for featuring women in swimsuits or Bring it On for putting girls in short skirts because in the context of the films swimsuits and short skirts are relevant and appropriate. There HAS, however, been a lot of mockery and some serious criticism of Marvel for putting Chris Evans in uncomfortably tight clothing with no purpose other than showcasing his body. “Steve Rogers can’t buy clothes that fit and all of his shirts are too tight” is actually a major fanfic trope because of that.

"some characters briefly objectify George but the *film* does not treat George as an object." Ok, but why THIS distinction never made when talking about the male gaze?

It is. Constantly. It’s the second sentence of the Wikipedia entry on “Male Gaze.” That’s a constant feature of academic media criticism. Here, have a video about how the framing and direction of Michael Bay in Transformers objectifies Megan Fox in a way that the film’s script does not:

undefined

youtube

That’s a whole video about that distinction.

Fox’s character in the first Transformers film was written as a hypercompetent, intelligent, complex woman. People remember the character as tits and ass because that’s what the camera reduced her to.

Think about Ellen Ripley.

Did you think about her in a Powerloader? Did you think about her holding a flame thrower? Did you think about her in her jumpsuit calmly trying to enforce quarantine and protect the entire ship?

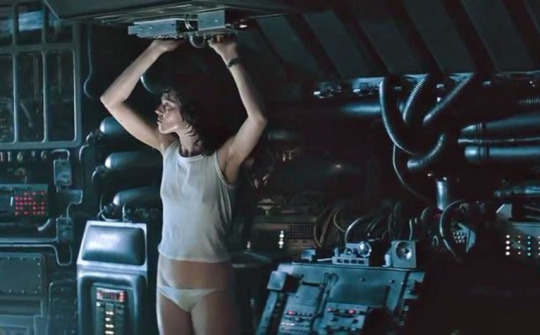

You probably, on reading the name “Ellen Ripley” did not think about her like this:

[Image description: Ellen Ripley wearing revealing underwear in front of a bunch of computer consoles and pipes; if you look very closely it is possible to see that the pipe behind her is not a pipe but is actually the alien Xenomorph curled up and camouflaged by the console]

The underwear scene stands out in Alien. It’s unusual, given the way that Ripley has been framed in the rest of the film. In the underwear scene Ridley Scott uses the framing of Ellen Ripley as a sexual object to 1) distract the viewer from seeing the xenomorph that is right behind her and 2) increase the character’s vulnerability to ratchet up tension in the film’s climactic scene.

This is an example of the director taking advantage of cinematic language to use the audience’s gaze against them and it is very well done.

That is very different than the way that Fox’s character (Michaela? I think? Someone who is so objectified that it is difficult to remember her name in spite of the fact that “Sam Witwicky” is almost obnoxiously hard to forget) is sexualized and objectified in Transformers.

But even Bay makes use of this! WHILE he is busy objectifying Fox as a director we also see the way her character is the subject of Sam’s gaze and the audience is STILL set up to be sympathetic to Sam because we’ve seen Michaela’s boyfriend objectifying her in a much more overt way than Sam does.

What I mean is, how is objectifying George any less sexist than Megan Fox's character in Transformers? They both have character beyond looks and both subvert gender tropes.

I mean, aside from the fact that I’ve already made the distinction that while some characters in GotJ objectify George the FILM does not, you know that just saying “This person is really hot!” isn’t itself objectifying, right? Michaela is a sexy prize that Sam is trying to win throughout the first Transformers film, George is a person who Ursula meets and takes on an adventure to the city and she gets to know and appreciate him as a *person* beyond his novelty as a “find” on her jungle excursion.

If Ursula spent the entire film attempting to seduce George by being sexy and ignored his wants and needs because he was just a dumb jungle man then yeah, it would be ALMOST as sexist as Bay is against his male characters. (Transformers goes hard as fuck at reinforcing “appropriate” gender roles and punishing characters who don’t live up to them and it is arguably more interested in gender policing its male characters than its female characters)

But you are asking me “isn’t this movie that you have repeatedly praised for modeling healthy masculinity sexist against men” and no? It’s not?

The fact that someone is naked and attractive is not in and of itself sexist. A major, major part of the plot of GotJ is people (and the audience!) seeing that George is more than the silly beefcake they initially mistook him for and I think you’re missing the fact that most films that feminists criticize as sexist have female characters who are naked and attractive and have very few memorable traits beyond being naked and attractive and fawning over the protagonist.

Who here remembered that Michaela’s dad was a felon and that she has a record for refusing to testify against him? You probably remembered that she’s good at cars because Transformers is a movie about cars and there are at least two scenes where people expect Michaela to be bad at cars and she isn’t. So. Okay. Michaela is good at cars. DOES THIS EVER HAVE ANY IMPACT ON THE PLOT? She hotwires a truck in the climactic fight scene and it is window dressing as the background for Sam to make his heroic sacrifice. If you replace Michaela with a sexy lamp is the film any different? It wouldn’t stop Sam from being the target of the Decepticons, wouldn’t change the fact that Sam gets Bumblebee, wouldn’t change the conflict with the government, and wouldn’t change anything in the final battle. Michaela exists to be a sexy lamp for Sam to kiss after he’s won the movie.

If you make George a sexy lamp you don’t have a movie. Now! Obviously Michaela is not the protagonist of Transformers and George IS the protagonist of the movie made about him so it’s not a one to one comparison, but “could you edit this character out without it having a significant impact on the plot of the film” is a pretty decent test as to whether the film treats the character as a Person or as a Decoration.

Michaela is good at cars. She exits the Transformers series by getting cheated on after spending a movie trying to trap Sam into proposing. This is not the gender subversion that you’re claiming it is.

Michaela deserved a better movie than Transformers and Megan Fox deserved better than working with Michael Bay.

301 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello, I re-read your fic "one of a king, no category" again recently and first of all I absolutely love it and I always tear up no less then 3 times every time I read it. I was curious, if you remember, how you decided on the 9 cats you chose for the 9 lives ceremony, and also were there any other characters you considered using but who didn't end up making the cut?

Hello there! Thank you so much for writing in with such a sweet compliment, it really warms my heart to know that story has hit such a lovely chord with so many people. I think out of all the stories I’ve written for Warriors so far, one of a kind, no category is the one I’m proudest of and the one I’d like to be remembered for the most.

And thank you for this question, it’s a very good one! I have a feeling it’ll get very long, though, so I’ll put it under the cut.

I didn’t have to think much at all to know which cats I wanted to write about for this story, because I’ve been thinking about these nine in various ways since I first read the series. In many ways, one of a kind, no category is a love letter to characters I felt were treated cruelly and unfairly in canon and I wanted to give them a brief moment to be something other than what they were--whether that was to complicate or reinterpret the narrative they’re given in canon, or to highlight the qualities they have that often get overlooked or underappreciated by the writers (and sometimes other fans).

So there’s cats like Silverstream and Rosetail, who are barely there and then killed off as a plot point--to cause drama for Greystripe or show the brutality of clan life, respectively. Then there’s cats like Lizardstripe, Nightcloud, and Foxheart who are basically written as shallow, “bitchy” antagonists--and as a result are often seen that way by the fandom--or cats like Ferncloud, who are seen as “boring” or “useless” because of their time in the nursery and often resented for that by fans.

And I don’t necessarily blame fans for these readings of the characters, because the canon is so badly written. I think there’s always a tendency for male characters to be given leniency and complicatedness that is often withheld for female characters, but in Warriors, that cultural reading issue is compounded by the fact the writers themselves don’t ever really do female characters justice. Canon Ferncloud is largely there to pop out kittens and then died in battle “as a result of fan complaints” because Erin Hunter’s misguided understanding of the criticism they were receiving--i.e., interpreting “all she does is have kittens” to mean “we want her to fight [and die]” instead of “please give her character depth--no, not death, no, Erin, don’t--”

I wanted to take these characters and humanise (for lack of a better word) their canonical representations in a way that makes you actually care about who they are/were and the life they lived. Silverstream’s death is a tragedy. Rosetail’s life is a triumph. I wanted these experiences to be embodied in a story in a way that could give readers feelings and change how people thought of these (canonically very badly written) characters, not because I think Erin Hunter is a secret genius and deserves it (they don’t, I hate them), but because the characters themselves deserve more recognition and care than they often receive.

Anyway, I’m sorry, I’ve gone way off track! To actually answer your questions:

1. Leopardstar: one of the few female leaders--whose story is then basically about what a bigot she is and how she betrayed her whole clan (more or less) for a man because she was secretly in love with Tigerstar. I hate that they made a female leader (one of very few!) just to be like “eh she’s a lackey to an evil man she’s in love with who doesn’t care about her.”

2. Rosetail: as mentioned before, she is barely in canon at all (in the main series; she returns in Bluestar’s Prophecy as kind of Bluefur’s best friend?). She’s actually the first clan cat to die after Firepaw joins Thunderclan, but it mostly gets swept aside and people are sad for like a minute and then the shock value wears off and she’s forgotten.

3. Nightcloud: she’s kind of the contentious female character of the main series, because she’s either too clingy or too mean or a bad mother etc., and I’ve seen many people sympathise with Crowfeather over her--even though her side of things genuinely sucks. I wanted to give her space to be a kind of unlikeable person who still deserved better than she got. I think she deserves the same compassion people are willing to the extend to the man who mistreats her.

4. Brightheart: one of the most famous disabled characters of canon--but she never really gets a decent resolution. Her ending is “happy” but I feel that she’s not really given closure for much of what happened to her, and in many ways the story around her is still very ableist. I feel like there’s a lot of extremely challenging internal growth that she would have had to do that never gets noticed in canon, so I wanted to give her a moment of sharing a fraction of the strength and wisdom she would have taught herself.

5. Silverstream: as mentioned before, she’s so young and it feels to me like she exists--and dies--for the purposes of man-pain and I hate that. She gets so little personality in canon and then dies in childbirth, and I wanted to first give her a self that is so wonderful and real that it genuinely is devastating that she dies. It’s not a shrug, or a “poor Greystripe”: it’s a heartbreak to see someone so vivacious and excellent and hopeful get their life cut short. I want her story to be centred on who she is, not who she fell in love with and how he feels.

6. Foxheart: she’s basically a mean, snotty villain in Yellowfang’s Secret (as is Lizardstripe) and an enemy of Yellowfang in a way that to me reeks of internalised misogyny from Erin Hunter, if I’m real with you. I wanted to give another interpretation of the events--especially considering how unbelievable it is that Yellowfang “got away” with that whole secret kit thing. It doesn’t make sense, unless you consider that other cats are in on it. Literally all Foxheart had to say to ruin Yellowfang’s life was “that kitten’s not mine”--and she never said that. I think that gets overlooked a lot and I wanted to explore that detail. And I thought it fitting to reinterpret a character whose name is literally an insult in canon (”fox-heart”) as having so much integrity that she would rather go down in history as a villain than be a snitch and a traitor to a clan-mate.

7. Lizardstripe: similar to above, she’s written as a horrible, bitter lady who resents her own mate and kits and is bullied into fostering Brokenkit and is miserable about that. It’s literally said “[h]er bitterness and resentment towards Brokenstar is what led him down his path of hatred” which is classic “blame a woman for a man’s behaviour” and a very rich statement from Erin Hunter who in the same breath is like “some cats (i.e., Brokentail) are just born evil as a punishment from Starclan on their birth mothers for breaking their vows.” It is so vile how Erin Hunter’s writing revolves as much as possible around blaming and punishing women for everything, including and especially men’s development and behaviour.

8. Ferncloud: sort of mentioned before, but Ferncloud over the years has gotten a lot of fan disapproval for being passive and frequently pregnant. I think a lot of those criticisms--when levelled at Erin Hunter’s lazy writing--are fair and just but sometimes I feel that, in pursuit of more “strong” female characters in media, some fans forget to appreciate the many ways femininity and female characters can be subversive and/or still good, even when they’re not traditional hero’s narratives. In the real world, domestic labour (i.e., women’s work) is significantly undervalued, and I feel that Ferncloud can be read as an amazing example of someone who works to the bone every day and is largely ignored and underappreciated because the work she does is expected and taken for granted.

9. Greypool: I love her--or at least my version of her. She doesn’t get a lot of attention in canon, other than a mention of being the foster mother to Bluestar’s kits and the fact she loses her memory as she ages and is murdered by Tigerclaw. It felt fitting for her to be the final life, both as a great and renowned storyteller in her own right and a cat considered to be very wise and kind with her words and thoughts, since ultimately one of a kind, no category is about the way stories can be told to shape the world--i.e., Erin Hunter’s often sexist canon versus the compassionate and intelligent retellings this fandom creates.

As for cats that weren’t included, I’m happy with the nine I chose and I love them, but there are a lot of other cats who’ve been poorly treated by canon that would deserve a better story too. Snowfur of Thunderclan leaps to mind, as does Feathertail, and Palebird of Windclan, and honestly even Bluestar and Mapleshade. I think to a certain extent it’s hard to really engage with any of these characters’ narratives without also acknowledging the impact of sexist tropes on that narrative--i.e., how much of canon is “the character” (an intentional construct) and how much of their characterisation/story is kind of a side-effect of uncritical sexism perpetuated in the writing of said character? And I don’t really know the answer, because that’s not really a line that can be drawn. But I like to think one of a kind, no category and similar stories help reimagine other versions of these characters as fuller, more real people and that thought makes me happy.

#reply#one of a kind no category#warriors#honestly i had to really pull back on this one so i didn't write you a whole essay but there's still a lot here and for that i am sorry#thank you for asking! i really like that story and it is the nicest thing in the world when people tell me they like it too

20 notes

·

View notes

Note

What are your thoughts on Jaime x Cersei, Jaime x Brienne, Tyrion x Tysha, George x Isabel, and Henry VIII x Anne Boleyn? (Sorry for the long list!)

Glad to see someone else feeling charitable and letting me vent my unsolicited opinions 😂. Saved the George x Isabel for the last cause I’m sure it will be the longest lmao!

Asked Via: Send me a ship and I'll give you my (brutally) honest opinion on it: https://lady-plantagenet.tumblr.com/post/627331607624302592/send-me-a-ship-and-ill-give-you-my-brutally

Jaime x Cersei: Despite it’s fundamental flaws, it is... titillating to read. The idea of people falling in love with their own other-gender counterpart is twisted yet so intriguing. I must confess that I am not as disgusted by incest as most people, so bear that in mind. The thing is, Cersei is definitely a narcissist with a lot of internalised misogyny and this ship just feels so justified to her character.

The issue is, and as the books go on, it becomes quickly clear that Jaime’s love is not as deep and as his appearance changes, and they no longer look identical Cersei’s own mental image, Cersei’s love also wanes and then you’re hit with how shallow it was. So I ship these two... but I also don’t because they’re toxic? Honestly, book-wise I am intrigued to see what will happen, if they end up together... or they don’t... either way I’m sure it will be quite a ride. You see, I’m not emotionally invested.

Jaime x Brienne: Oh the Sapphires... Obviously anyone who cares for Jaime’s wellbeing would want him to end up with Brienne as opposed to Cersei. I read this interesting theory recently on how these two don’t actually love each other but confuse their strong platonic feelings of affection for romance. You see, that’s also an interesting take as both characters are quite bereft off opposite gender friendships.

However, I strongly ship them romantically as well, Book!Brienne (hey show as well!) is truly admirable because based on her choice in men e.g. Renly, you can see how she had still not given up on her maidenly fantasies and I just love her for that, because true love isn’t something to which only pretty women are entitled. She in many ways represents salvation for him as she being a true knight in spite of her gender, can veer him back into the path of chivalry. He is most chivalrous around her, I mean, not only because her good conduct influences but also because he performs some of the most knightly deeds by cause of her e.g. rescuing her from the bear pit. I like this ship, it’s a good trope subversion.

Tyrion x Tysha: I find this one of the more heartbreaking ships of ASOIAF, because to me it represents Tyrion’s loss of innocence.

She is a haunting figure because of how small remnants of her memory were enough to pull Tyrion into the toxic relationship he had with Shae e.g. she too hard dark hair and there was music around when he met her. Its one of those weird (as @omgellendean put it in her brutally honest ask tag answer - a character who consists of only a name), but unlike Ashara Dayne, she is not idealised and given this over-the-top tragic story. So this elusive Tysha is an entity by what she symbolises: foregone youth and a sweetness that has no place in the ASOIAF universe.

Henry VIII x Anne Boleyn: As I said in my last ask. I cannot tolerate the romanticisation of infidelity, and that is especially when the male’s spouse is a wonderful woman fit for him and has done nothing wrong. I don’t have strong feelings against Anne Boleyn herself, as I prefer to see her as ‘Anne the Educated and Sophisticated Reformer’ as opposed to ‘Anne the Seductress’. Ugh let me just say... rule of thumb for whether it’s a good pair: Do thousands have to die for your selfish desire to be together? Yes? Then probably not meant to be. Just a thought.

I think Anne knew her own mind and I like to think her strong beliefs influenced her decision to breach this marriage (no I didn’t think she was her father’s pawn gah I’m sick of that term), but they were ultimately unsuited in everything and it was a passion brought about by Henry’s caprice. My heart breaks when I think on how Anne could have been happily married to Henry Percy. I’m also tried of this whole ‘master manipulator of men’s hearts’ reputation Anne is getting. You do realise refusing to be a mistress was not being a tease as much as it was just being a conventionally virtuous woman..? The girl knew her worth.

George x Isabel: Oh god. I promise to not start writing an essay. As weird as it is to ship dead people, they are my OTP, the main characters of my main historyfanfic, and frankly the most unsung couple of TWOTR. The fact that there are no records of letters or any particularly over-the-top romantic gestures by either of them, just intrigues me more because it was very much a relationship defined in subtle deeds. If you peruse the more academic TWOTR literature you can see all the fine but conclusive evidences of a devoted relationship: He posthumously enrolled her in a guild when he stayed there with his children (months after she died), he was buried together with her and her ancestors not his, how during 1470 he sent her to Exeter for her safekeeping while her mother and sister remained at Warwick and when a siege broke out he (and his father-in-law) immediately rode south to lift it and the amount of expenses and care he put into her funeral. Not to mention, the hassle it took for them to get married: years of trying to get a dispensation underneath the king’s nose culminating in them having to cross the channel.

The thing is, it had a lot of politics behind it and to be honest I don’t find that less romantic. It was one right for both of them: for the wealthiest heiress in England and the handsome younger brother and heir of King Edward - truly no one else would do for any of them. One of the things that grabs me is the medievalness of it all, how they were bound together by what was essentially a plan to reverse the country’s inevitable transition out of ‘bastard feudalism’. You also get a sense of how this marriage despite the ultimate failure of its purpose (to make George King) brought George the chance to establish himself as a major magnate through his wife’s lands which ultimately became his main source of power as opposed to his royal status. The relative peace that ensued after 1472 shows that his status as Warwick’s political heir (as Christine Carpenter put it) did something to placate the disapointment of not becoming king. So the way I see it, Isabel’s death took from him any of the satisfaction and peace she brought with her lands and persona as he once again reverted to his old (even more than before) reckless self. Not to mention the people he executed after her death in his grief believe in her to have been poisoned (most historians believe that’s unlikely).

Aside from that, in a society where pretty much everyone strayed (even Anthony Woodville had a bastard daughter), it is quite heart-warming how the man known for his treachery, happened to be one of the only ones loyal to his wife: no bastards or women were ever linked to his name not even in rumour. As for Isabel, she is quite a shadowy figure but you get the sense she was intelligent because of the care her father took in preparing her as his heir, because of her wealth you get this sense of majesty and significance about her. The two times we can deduce anything about her personality is a true supporter of her husband: once, when deciding to treat with the Yorks behind her father’s back to reconcile George to them, second, remaining steadfast to George when he tried to squirrel her sister Anne out of her inheritance. Based on the homage she paid to her ancestors, she seems proud of her ancestry so it’s quite intriguing to think why she made the aforementioned two choices, endangering her father and sister in favour of her husband. And oh god I’m rambling, I can say even more if you can believe it but I shall stop. Overall, one might think I’m wishful thinking but frankly Anne and Richard are touted as star-crossed lovers all the time and with even littler evidence to support it (not that I don’t ship them, I do). I might be subjective, but the story of George and Isabel’s life is just so compelling...

#🍷❤️#thank you for asking darling#I know you were being nice about the last one and giving me an oppportunity to gush 😂#if anyone has anything to say to my rambles feel free to send an ask#or hell if anyone else wants to send me other ships#cersei lannister#jaime lannister#cersei x jaime#brienne of tarth#jaime x brienne#tyrion lannister#tysha#tyrion x tysha#anne boleyn#henry viii#henry viii x anne boleyn#george of clarence#george duke of clarence#isabel neville#gisabel#george x isabel

28 notes

·

View notes

Link

The Rise of Skywalker Does a Terrible Disservice to the Women of Star Wars

Besides Reylo, one of the great marketing tools of the Star Wars sequel trilogy was its emphasis on girl power, as well its subversion of class dynamics. The films showed that women -- even poor, destitute women with no connections to powerful men -- could play the same role in the franchise as every cocky flyboy or adopted son of a moisture farmer. Unfortunately, and despite the press tour assurances from the cast and crew that Rey and her gal pals are here to lead a new generation of fans into the new world of gender equality, The Rise of Skywalker makes sure that none of the women of the franchise gets to live happily ever after nor establish any lasting romantic connection.

Instead, Episode IX leans heavily into the tired trope of the "strong female character" that has to resign from silly notions like love and family to live up to her full potential. Adding insult to injury, the film removes all agency from the women, and instead thrusts them onto a straight-and-narrow path of contrived choices foisted upon them by male characters or by the Force -- which, in J.J. Abrams' movie, acts not as the power that propels life in the universe, but like the mean Catherine de Bourgh of Pride and Prejudice.

Let's start with Leia Organa, whose call for help in The Last Jedi was ignored by the entire galaxy. However, Lando Calrissian, who has been hanging around on Pasaana doing who knows what, just has to say the word for an entire legacy fleet to appear out of nowhere. Then there's the handling of her Jedi training, which she gave up because she felt the Force might corrupt her unborn son -- a narrative choice that comes out of left field but that mirrors the real-world dilemma of women giving up promotions for fear that their careers might get in the way of parenting.

But we could argue that Leia's arc in Episode IX is clunky because Abrams had limited footage of the late Carrie Fisher. But what about the characters portrayed by living actresses?

There's Rose Tico, played by Kelly Marie Tran, who had a major role in The Last Jedi with an interesting arc of her own. Unfortunately, a vocal segment of Star Warsfans loathed the character and harassed the actress until she left social media. Things looked brighter when Abrams announced Tran would rejoin the cast in The Rise of Skywalker and that her role would be even better. She was billed as a general, an essential part of the Resistance; Tran went on a press tour and talked about the great feminine energy of the set. The comes The Rise of Skywalker, where Rose appears three times, speaks four lines, and is sidelined to the "really important job" of tech support, with her connection with Finn never addressed. In The Rise of Skywalker, Rose doesn't get romance, connections, friendship, a job, or a story of her own -- something that should please the most toxic fans.

Then there's Jannah, played by Naomi Ackie, another "strong female character." The twist this time is that, like Finn, she's a former Stormtrooper who mutinied and defied an order to kill a bunch of villagers. For a few seconds, her story is hopeful and fascinating, and teases the line from the trailer that "good people will fight if we lead them," that free will and the power of the individual are concepts that exist in Abrams' Star Wars.

How foolish of the audience to hold such hope. Jannah and Finn explain theyweren't the ones who decided to spare the innocent villagers; it was a feeling. The Force takes care of silly dramatic concepts like agency, choice and heroism. Jannah is not a good person because of her actions, but because the Force willedher to be one. The only funny thing about this depressing predeterministic twist is that it also works as an apt metaphor for the actions of the characters in The Rise of Skywalker, who do things not because they make sense, but because the script -- the Force -- says so. To add another nail to the coffin, The Rise of Skywalker Visual Dictionary hints at Lando being Jannah's father, yet another woman of Star Wars whose story doesn't matter unless she's related to a legacy male character.

Moving on, Keri Russell plays Zorii Bliss, a spice runner from Kijimi who essentially wears Leia's slave outfit, only with thermal underwear. Zorii's only purpose in the story is to provide a tragic background for Poe Dameron, as well as a potential love interest. She's also a glorified MacGuffin holder (twice!), and one of the many characters that Abrams fake-kills to ignite an emotional response from the viewer in a desperate effort to make Poe sympathetic. Zorii's role could have easily been filled by Rose, who was an actual tech whiz with a questionable past and a potential massive beef against Poe. After all, he's directly responsible for her sister's death.

Let's move on to Rey (Daisy Ridley), who is retconned from being a resilient orphan scavenger strong in the Force... to receiving her powers from a male bloodline. Now, to be perfectly clear, there's nothing wrong with overly dramatic space operas where everyone is related to a royal family, but this "reveal" goes against the premise of The Force Awakens and the heart of The Last Jedi, which proposes that anyone can be a hero.

There were no hints at all about this "twist" -- not in the movies, in the animated series or in the ancillary material, which makes it feel like a last-minute decision designed to appease those fans who accused Rey of being an overpowered Mary Sue, overlooking one of the most common Mary Sue tropes: their tendency to be secretly related to important canon characters.

Another Mary Sue trope exploited in The Rise of Skywalker, but that wasn't even touched in the previous two movies, is the female character sacrificing herself for the greater good, only to be saved at the last minute by a man, which is exactly what happens here. This double-whammy of "being powerful because of grandad" and "getting to live because of a man" is particularly egregious, and caters to no one, because of what happens right after Ben Solo sacrifices himself. We'll get to that in a moment.

Then there's the Force vision scene. Rey already had a trippy Force vision in The Last Jedi, a deep dive into an array of feminine symbology that she wasn't afraid to confront, from which she emerged heartbroken but stronger. In The Rise of Skywalker, this moment is undercut and shows Rey terrified of the darker, sexier, powerful version of herself, which is a hard pill to swallow. Rey explicitly says that she has nightmare visions where she and Kylo Ren are the evil Empress and Emperor of the Galaxy, linking the fulfillment of her desires to the galaxy's apocalypse. In Episode IX, romantic love is a flaw that the "strong female character" should overcome, but sex is pure evil.

Her visceral rejection of her dark side is also a 180 turn on her chill acceptance of her darkness in The Last Jedi. In the real world, women are taught from a young age to hide their negative feelings, to smile and live to be pleasant to everyone, to not be loud or angry or intense. That mentality only makes things easier for everyone in the world who is not a woman, and runs contrary to the quickly angered but enthusiastic scavenger of the previous two movies. However, by the end of The Rise of Skywalker, Rey has transformed into this Cool Girl version of Ideal Femininity/Strong Woman Character.

Ben Solo's death right after his redemption and first kiss should have been treated like a tragedy at least by Rey, and at least for one minute... but she does not react at all. The camera cuts from Ben's clothes folding as he disappears to Rey's neutral expression as she flies back to the Resistance. His death, and any emotional reaction that it might have caused in the protagonist, is not mentioned at all, which is baffling, to say the least. After a brief reunion with Finn and Poe, Rey immediately regresses on-screen to a lonely child on a desert planet, sliding down a Tatooine sand dune and negating her evolution for the last two movies, just so Abrams could throw in a homage to himself.

For the sake of argument, let's take Rey's reveal of her villainous ancestry at face value, and let's imagine that Disney had prepared this reveal from The Force Awakens: Her ending is still insulting, because it forces her to pay for the actions of her grandfather, despite having suffered as much as anyone from his evil ways. Palpatine's murderous pursuit of his son's family was what caused Rey to grow up heartbroken and abandoned on Jakku.

Rey longed for family and love her entire life; she jumped at the opportunity to establish a real connection with Han Solo, Maz Kanata, Finn, Leia, Luke and Kylo Ren, and in The Rise of Skywalker she looks longingly at the Pasaana children, clearly wanting a family of her own. Rey marveled at the green of Takodana in The Force Awakens and at the water of Ahch-To in The Last Jedi. Just like Anakin, she hated the desert. So why does the plot force her to go back to Tatooine to take on the Skywalker name, a planet where none of the Skywalkers, Organas or Solos were born; that Anakin and Luke longed to escape; where Shmi Skywalker was enslaved twice and then killed; and where Leia became Jabba's sex doll? Wouldn't it make more sense for her to head to verdant, watery Naboo, where both Palpatine and Padmé came from, the place where the latter wanted to raise her Skywalker twins?

But, no, Rey doesn't get to live where she would be logically happier, or where it makes sense; she goes where the fan service is stronger, and the twin suns of Tatooine were unparalleled -- until now. When an old woman asks Rey her family name, she answers "Skywalker," which doesn't hold up to close examination. Luke Skywalker refused to train her, Leia's name was Organa, Ben and Han were Solos, and she's standing on the Lars' buried homestead. And although it makes sense that she would lie about her true ancestry, denying the Palpatine name still reeks of burying her darker side, which worked really well for the Jedi Order.

Compare this ending of a lonely girl on a barren planet lying to strangers about her family name to the ending of The Return of the Jedi, where Luke, Han, and Leia are surrounded by life and celebration, and everyone is radiant with love and living family. Or compare it to the ending of The Last Jedi, where a Force-sensitive boy is looking up at shooting star. Or even the final scene of Revenge of the Sith, which takes place in the same spot after the fall of the Republic, the death of Padmé and the rise of Darth Vader -- but at least in that little spot there's love, family, life and hope.

Directed and co-written by J.J. Abrams, Star Wars: The Rise of Skywalker stars Daisy Ridley, Adam Driver, John Boyega, Oscar Isaac, Lupita Nyong’o, Domhnall Gleeson, Kelly Marie Tran, Joonas Suotamo, Billie Lourd, Keri Russell, Anthony Daniels, Mark Hamill, Billy Dee Williams, and Carrie Fisher, with Naomi Ackie and Richard E. Grant.

114 notes

·

View notes

Note

I just read your fandom racists post and under the fake woke list, you had “why can’t this strong woc just be single?! she’s awesome without a man” And I don’t see an immediate issue with this. I see it from the point of view of there aren’t enough (healthy especially) poc romances in our media, but I want to know if I’m missing some nuance here? I want to learn and change my viewpoint if I’ve got the wrong idea.

There’s a lot going on with that bullet point, definitely, and the ideology behind it goes way deeper, but it usually manifests in “she doesn’t need a man!” There are so many stereotypes about WOC that prevail in media and fandom for the purpose of making WOC seem unloveable and unfriendly. Off the top of my mind we have:

WOC as caretakers. This encompasses mothers, nannies, cleaning staff, whatever may have you, any role where a WOC is in some capacity majorly responsible for other people’s wellbeing. Think Viola Davis in The Help, Daenerys’s handmaids, Gwen from Merlin… I could name more. This stereotype goes back to colonial times when white people wanted to shoehorn black women into caretaker roles so white slavers could pretend that they weren’t attracted to and sexually assaulting slave women. The caretaker/nanny image is usually of an older woman who doesn’t fit the ideal white body type and only lives to make white people happy. Thus if she’s “matronly,” and working hard she can’t have time for a relationship and she can’t possibly be attractive, especially to a white man.

WOC as angry. This is one of the most common ones out there. It’s meant to paint WOC as unreasonable, overly emotional, and violent, especially in comparison to the ideal white lady. May I direct everyone to this article, “Uses of Anger” by Audre Lorde, 1981. My little TL;DR here could never ever do it justice, so please read it for the full effect, but: the basic tenet is that although white people view anger as threatening, it is extremely productive, enlightening, and useful. Not only do white people try to downplay/vilify anger of POC to control our self-expression and discussions of racism, but they also tend to automatically stereotype every WOC as angry and unpleasant. This is also why while many white women aren’t empowered by the damsel in distress role, many WOC are tired of the headstrong fighter role. White women are more likely to be written as desirable and worth saving, but can move out of that role (ie movie Katniss, Wonder Woman, Dany Targ, Capt. Marvel etc). WOC on the other hand have always been the ones to save themselves/others and support their white BFFs without complaint, thus leading real WOC to shoulder astronomic expectations from people who expect us to save them. We haven’t been able to leave behind the angry trope as well as white women have done to the damsel trope, and oftentimes WOC have to settle for white female characters or MOC as representation. Thus, we have little representation of softer, more mentally/emotionally driven WOC, as well as WOC being a desirable/viable love interest or the main characters in a best friend duo.

WOC as “independent.” Again, the “independent” idea often follows white women’s models of what empowerment looks like for all women. Whenever an interracial ship pops up on a show, literally without fail, one of the first arguments against its existence is something like “IDK I kind of liked her alone. We have so little representation of women being independent” (funny how this doesn’t show up nearly as often with white/white ships), or “It’s so heteronormative for these two to get together when we could have a (white) mlm ship.” In isolation, these arguments are fine and actually make sense, but in context they don’t work. WOC have never been written in long-term, high concept, elaborate romances like white women have (think classic British romance novels, Romeo & Juliet usually being cast white, the extreme whiteness of rom coms/romance movies, most interracial ships being between a MOC and a white woman, cancellation of Sleepy Hollow etc). A lot of WOC, regardless of sexuality, rarely see themselves in romances. We’re used to being de-feminized, rejected, hated, portrayed as ugly, the first stop on the way to a white/white endgame love story, sex workers, the invincible strong #queen who can’t get hurt, Whitey’s supportive BFF and dying for her, or a doting (or bothersome) wife for a main MOC. We’re so used to being “independent” (aka endlessly taking care of everyone else, working way harder than everyone, getting less credit for that work, being told/expected to be “strong” for others) that actually showing the opposite for WOC would be subversive.

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

Repossessing the Body: Transgressive Desire in “Carmilla” and “Dracula” (I)

Every time I encounter media where Carmilla is either the servant of Dracula or in love with him (very often both simultaneously), I want to flip tables.

Carmilla not only despised men, but she was a veiled depiction of a lesbian woman. As an innocent human, she was preyed on and murdered by a male vampire who was obsessed with her and yet emerged from her grave a cunning and powerful figure who cleverly exploited the womanly tropes of her time (the helpless and delicate flower) to dupe and charm men into doing exactly as she wanted in pursuit of her goals. Her romantic interests and desires for companionship were reserved exclusively for women. Every time I see her being relegated to the role of love interest for a man, I feel like her nature and personality being denied, misused and erased.

Back in Ye Olde Days (1996), I discovered a fascinating article by Elizabeth Signorotti which put forward the theory that Dracula was written as a patriarchal response to the unleashed female power and sexuality depicted in Carmilla. This remarkable article, which I have split into parts and transcribed below, explains better than I ever could the power of Carmilla and the ways in which its themes of female empowerment and agency were perceived as a threat.

Repossessing the Body: Transgressive Desire in “Carmilla” and “Dracula” (part I)

Of the vampire tales to date, Bram Stoker’s Dracula has unquestionably become the most popular and the most critically examined. It constitutes, however, the culmination of a series of nineteenth-century vampire tales that have been overshadowed by Stoker’s 1897 novel. To be sure, many of the earlier tales provide little more than a collective history of the vampire lore Stoker incorporated in Dracula, but Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu’s little known “Carmilla” (1872) is the original tale to which Stoker’s Dracula served as a response. In “Carmilla” Le Fanu chronicles the development of a vampiric relationship between two women, in which it becomes increasingly clear that Laura’s and Carmilla’s lesbian relationship defies the traditional structures of kinship by which men regulate the exchange of women to promote male bonding. On the contrary, Le Fanu allows Laura and Carmilla to usurp male authority and to bestow themselves on whom they please, completely excluding male participation in the exchange of women, normative as discussed by Claude Levi-Strauss and more recently by Gayle Rubin and Eve Sedgwick. Stoker later responded to Le Fanu’s narrative of female empowerment by reinstating male control in the exchange of women. In effect, Dracula seeks to repossess the female body for the purposes of male pleasure and exchange, and to correct the reckless unleashing of female desire in Le Fanu’s “Carmilla.”

In The Elementary Structures of Kinship, Levi-Strauss argues that women are “valuables par excellence from both the biological and the social points of view... without which life is impossible.” As “valuables,” women are seen “as the object of personal desire, thus exciting sexual and proprietorial instincts... [and also as] the subject of the desire of others, ... binding others through alliance with them.” Women, then, become the means of alliance, the ”supreme gift” that binds men together and creates social order. For Levi-Strauss, marriage most significantly reveals men’s complete control of women. He argues that traditionally “the total relationship of exchange which constitutes marriage is not established between a man and a woman, where each owes and receives something, but between two groups of men, and the woman figures only as one of the objects in the exchange, not as one of the partners between whom the exchange takes place.” As an essential and valuable “sign” to be possessed and exchanged, woman’s sole purpose is to provide the passive link between men.

Levi-Strauss’ exploration of the role women play in creating male alliance is further examined in Gayle Rubin’s “The Traffic in Women” and in Eve Sedgwick’s Between Men. Whereas Levi-Strauss ultimately romanticizes the exchange of women, Rubin examines the specific implications for women resulting from his argument. She states that Levi-Strauss’ “exchange of women” is shorthand for expressing the “social relations of a kinship system... [where] men have certain rights in their female kin...[and where] women do not have the same rights either to themselves or to their male kin.” Since women are “transacted” by men, they become only “a conduit of a relationship rather than a partner to it” and are denied the “benefits of their own circulation.” Rubin further stresses that “compulsory heterosexuality is a product of male kinship” because “women... can only be properly [valued] by someone ‘with a penis’(phallus). Since the girl has no ‘phallus’, she has no ‘right’ to love her mother or another woman.” In her examination of Levi-Strauss, Rubin underscores woman’s historical subjection to male desire and her exclusion from the social order governed by male alliance.

Sedgwick broadens Rubin’s argument by investigating “compulsory heterosexuality” as a distinguishing factor in female relationships and in male relationships. She argues that men’s relationships are defined by “homosocial desire,” that homosocial relationships between men must be distinguished from socially threatening homosexual unions, and the only way to eliminate the homosexual threat between men is to include a woman in the relationship, forming a (safe) triangular configuration rather than a (threatening) linear, male-to-male union. She contends that contrary to women’s relationships “patriarchal structures [assure] that ‘obligatory heterosexuality’ is built into male-dominated kinship systems, [and] that homophobia is a necessary consequence of... patriarchal institutions [such] as heterosexual marriage.” Women function in this system as signs and tools to ensure the survival of male relationships and to deflect the threat of homosexuality by serving as a link between men.

Sedgwick sums up social perceptions of women’s and men’s relationships as “diacritical opposition between the ‘homosocial’ and the ‘homosexual,’” an opposition that ”seems to be much less thorough and dichotomous for women, in our society, than for men.” She argues that all women in our society who promote the interests of other women (by teaching, nurturing, studying, marching for, or employing) are “pursuing congruent and closely related activities. Thus the adjective ‘homosocial’ as applied to women’s bonds... need not be pointedly dichotomized as against ‘homosexual’; it can intelligibly dominate the entire continuum.” The unity of the lesbian continuum, “extending over the erotic, social, familial, economic, and political realms, would not be so striking if it were not in strong contrast to the arrangement among males.” That arrangement, as Levi-Strauss has defined it, is a system of alliance between men that requires, in some form, the exchange of women to bind men and (as Sedgwick implies) to stave off homosexual anxiety. Sedgwick makes clear that women’s relationships are not governed by homophobia; therefore, excluding men from female friendships or from access to women poses more of a threat to male kinship systems than to female. Thus, female homosocial bonds potentially carry tremendous power to subvert or demolish existing patriarchal kinship structures, which is precisely what happens in “Carmilla.”

Throughout most of the nineteenth century the central figure in vampire tales was a male whose relationships were used to depict various conflicts in contemporary society. James Twitchell observes in The Living Dead that nineteenth-century writers mainly used the vampire “to express various human relationships, relationships that the artist himself had with family, with friends, with lovers, and even with art itself.” Other critics note that the vampire, a dead body that drinks blood and preys on innocent victims to sustain its own life, acts as a complex metaphor: it could represent the economic dependence of women; the parasitic relationship between the aristocracy and the oppressed middle and lower classes: unrepressed female sexuality; eugenic contamination; enervating parent/child relationships; and, of course, sexual relationships deemed subversive or perverse in hegemonic discourse.” Perhaps most interesting is Nina Auerbach’s contention that the demonized (or vampirized) woman in nineteenth-century literature and art really depicts a “hero who was strong enough to bear the hopes and fears of a century’s worship.” Auerbach’s comment may be true in some instances, but by and large the majority of women in vampire tales, at least in the early and mid-nineteenth century, were far too marginalized and victimized to be seen as heroic; like the male protagonists of those tales, who brutalized them, women vampires were generally perceived as loathsome and diseased.

Le Fanu’s “Carmilla” - the first vampire tale whose protagonist is a woman vampire - marks the growing concern about the power of female homosocial relationships in the nineteenth century. All of Carmilla’s predecessors - Lord Ruthven, Varney, Melmoth - were men. Le Fanu’s creation of a woman vampire anticipates the shift toward the end of the century to predominantly female vampires. In both art and literature, women and specifically women’s bodies became progressively associated with the vampire. One explanation for this shift, as Carol Senf points out, is the “growing awareness of women’s power and influence... [as] feminists began to petition for additional rights for women. Concerned with women’s power and influence, writers... often responded by creating powerful women characters, the vampire being one of the most powerful negative images.” But women’s potential power alone does not fully explain the proliferation of women vampires. The female body itself was demonized. According to Sian Macfie, “the function or dysfunction of the female body was juxtaposed with notions of the perceived threat of vampirism... [and these notions] were largely based upon a sense of women’s association with blood [as a result of menstruation]. However, the idea of female vampirism also came to be understood in a more figurative sense. In addition to the idea of literal contagion of the blood, vampirism came to be associatively linked to the notion of moral contagion and especially with the ‘contamination’ of lesbianism.” Citing Havelock Ellis, who hypothesized that “homosexuality... occurs with special frequency in women of high intelligence who... influence others,” Macfie concludes that “the notion of vampirism also came to be used metaphorically to refer to a social phenomenon, the ‘psychic sponge.’ The psychic sponge was understood to be a woman who was perceived [as] a drain on the energy and [the] emotional and intellectual resources of her companions.” As a result of women’s perceived link with vampirism, by the late nineteenth century “close female bonding and lesbianism are conflated with notions of the unhealthy draining of female vitality.”

“Carmilla“ is the vampire tale that most readily defines the established patriarchal systems of kinship discussed above and that most provokingly challenges nineteenth-century notions of the “contamination of lesbianism“ and the female “psychic sponge.“ Florence Marryat’s The Blood of the Vampire (1897) depicts an equally interesting lesbian vampire relation, offering insights into fin-de-siecle stereotypes of female sexuality and gendered identity, but Le Fanu’s tale is the first to investigate disruptive lesbian desire. Although “Carmilla“’s denouement is ambiguous, Le Fanu refrains from heavy-handed moralizing, leaving open the possibility that Laura’s and Carmilla’s vampiric relationship is sexually liberating and for them highly desirable. The ontological change in Laura between the beginning of the narrative and the end is never reversed, suggesting that her shifting desires are, for her, healthy and vital.

Le Fanu originally published “Carmilla” in the short-lived Victorian periodical The Dark Blue, then added the prologue and included the tale in In a Glass Darkly, five unrelated narratives held together by the figure of Dr. Hesselius, a student of psychic phenomena whose case histories make up these stories. Not only “the greatest” of Le Fanu’s works, “Carmilla” is also the most daring. It depicts a society where men increasingly become relegated to powerless positions while women assume aggressive roles. Le Fanu pushes his male characters, who lose all control over their women, towards the edge of his narrative. Ineffectual in either understanding or treating Styria’s baffling (female) “malady,” Le Fanu’s men suffer exclusion from male kinship systems because they are unable to exchange women. Instead, women control their own exchange, prompting W. J. McCormack to observe that in “Carmilla” “feminine nature is powerful, destructively powerful, and its objects become hypnotized (or hyperstatically controlled) in its power.” Le Fanu untethers “destructively powerful” feminine nature in “Carmilla” and refuses to thether it by the end of his story.

Part II is here.

#carmilla#dracula#j sheridan le fanu#bram stoker#vampire#vampire mythos#feminism#empowerment#women#erasure#compulsory femininity#feminist reading

28 notes

·

View notes

Note

why does anyone think level of obviousness is a reason something won't happen in Star Wars? When has Star Wars ever not been incredibly obvious? It was originally written to be the most textbook possible Hero's Journey, following Campbell on purpose. It had one surprising plot twist thirty years ago and people act like it's fucking LOST or whatever. She says redemption is a given so why would she suddenly think logical storytelling is a trap when it comes to something equally spelled out?

Well to be fair, LOST was a JJ Abrams project and he DOES tend to gravitate toward stories with a lot of mystery and strange twists and turns. A lot of movies these days, particularly Disney movies, are also trying to be subversive, especially regarding romance tropes. Maleficent had the princess awakened by a motherly kiss instead of the prince. Frozen had the princess saved by her own act of love for her sister instead of the love of a man, and the handsome prince turned out to be evil. The Nutcracker also apparently ended with the heroine going back home to her dad instead of hooking up with the prince. Moana made a big deal of not having romance at all.

As for Star Wars, the one big twist it had was the most memorable part of the whole series, so people expect something as big and profoundly earth-shattering to happen in the sequel trilogy to top it.

What people don’t get is that twists need to happen organically, not just for the sake of being clever or Woke™. Maleficent was all about the evil villainess regretting putting the curse on Aurora to spite the man who broke hear heart, and learning she was wrong to believe there was no such thing as “true love’s kiss”. So it was only natural that it was her kiss that saved Aurora and not the prince’s.

In Frozen, it was set-up from the beginning that Anna and Elsa’s relationship was taking center stage and romance was the b-plot, so it made sense that the plot would be resolved by Anna saving herself through her own act of love for her sister, rather than being saved by the love of a man. It was also set-up from the beginning that Anna was wrong to want to marry someone she’d just met, so it made sense for Hans to be evil, to make her understand why that was wrong, regardless of how many people bitch that it came out of nowhere.

In Moana, romance just wasn’t brought up at all, there was never anything to suggest that she and Maui would get together, so there was nothing to subvert.

As for the sequel trilogy, people came into it expecting a parentage twist and got thrown when it happened in the first act of the first film, so they latched onto Reywalker/Solo/Kenobi theories because they assumed the twist had to be something meaningful to the protagonist, not realizing that Kylo IS one of the main protagonists and the twist that he, the villain, is the son of the previous trilogy’s heroes DOES have ramifications for Rey. Jenny, thankfully, realized that these theories made no sense because what was established about Rey and the way the Skywalker clan spoke about their family history and acted toward her didn’t support the idea that she was their long-lost relative and you’d have to bend over backwards even harder to explain Rey Kenobi, and ultimately none of those twists were a logical conclusion to Rey’s character arc about holding herself back because she’s stuck thinking she needs someone else to give her the family and the purpose she’s seeking in life. I can’t speak as to why it took Jenny so long to connect the dots and realize that Reylo made more sense than Rey ending up single or hooking up with another guy after going through the profound life-changing experiences with Kylo that would ultimately see him redeemed. Maybe she thought Kylo would die or that Disney would want Rey to be a Strong Independent Woman Who Don’t Need No Man? Maybe she, like a lot of audiences, expected that the backlash toward the romance in the prequel trilogy, the moral panic and ridicule of Twilight/50 Shades, and the praise movies like Frozen and Moana got for having Strong Independent Women Who Don’t Need No Man would compel Disney to steer clear of romance, particularly of the non-vanilla variety. A lot of people read TLJ as a cautionary tale meant to teach Rey that she was foolish for thinking she could save Kylo. Maybe Jenny expected that Kylo was just going to redeem himself on his own because It’s Not A Woman’s Job or the relationship was going to be platonic because no romance = woke and subversive and that’s better than being satisfying, especially to what’s perceived as the same demographic that enjoys lowbrow trash like Twilight/50 Shades.

#reylo#jenny nicholson#star wars#star wars tlj#tlj#the last jedi#star wars the last jedi#anon#anonymous#ask#asks

23 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Finished Buffy season 3

Some finale. I have thoughts.

First off, once again time has betrayed me. I knew Angel was on his way to his own series so that plotline lacked the devastation that probably came with it on first viewing.

I’m assuming Faith is going to recover at some point since she’s just in a coma. It would have made way more sense for her to have died and visited Buffy in a dream, but we can’t give Buffy a kill count just yet I guess. After all the special attention we gave Faith for her one human kill, i suppose Buff is already needing enough therapy for one year.

I like that the mayor had sincere feelings for Faith in the end. He was a great subversion of the evil demon character by way of the the straight-laced 50s dad. And the big finale with the models and the cgi monster was ADORABLE lol. I’m probably the only one who thinks that though.

Xander did improve by the end of the season. They were forcing a “he’s not so useless after all” theme through the second half and paid that off by having him know how to use guns I guess? That one time he was brainwashed into knowing how to use guns was the best thing that ever happened to him. What I did NOT appreciate was the straw man “shewitch manhater” in the form of the wish girl who came around to love b/c Xander lowered his standards and took her to the prom. Lesson for all writers -- its weak character craft to make your character look better by making other characters worse by comparison. Wish Girl’s only purpose in the last couple episodes was to prop Xander up and let him defend men to her. Specifically the kind of masculinity that I’ve been complaining about concerning HIM for a while now. Men aren’t just sex goggles, which Xander has been this whole show. They have the capacity for a broad spectrum of emotion and can be strong (aka substantive and contributing to the story) in ways other than or in addition to machismo. Wish Girl complains about evidence of toxic masculinity which Xander is like poster child for. Him being afraid of a more powerful foe or falling behind Buffy (who is supernaturally powerful) in a fight is played for laughs more often than not, and when it’s not that he’s being called pathetic and made to feel bad about that. Finally Wish Girl does this grunt grunt pro woman thing that makes her absolutely insufferable and stupidly shallow to personify criticism of men (xander) in general specifically so Xander can dress her down in defense of his gender.

Listen, show, you didn’t have to go to this length to show that you can write substantial, powerful, and likable men. My case in point is effin OZ. Oz prove through this show that he can take a back-seat role, be vulnerable, play support, and still be a strong male character. Unless he’s become a werewolf he’s far from the strongest fighter in the room. He’s a good student but not a super genius in supernatural things like Willow or Giles are. He’s got his band and his own interests, but aren’t specifically defined by these roles. What defines him as such a strong character is how he dealt with Willow’s cheating on him, and the capacity for honesty and forgiveness he met in that moment. Cordelia’s character did the same thing -- her response to Xander’s cheating taught us about her as a character. She’s still shallow and petty, but we’ve seen the depth of her hurt and her affection and watched her edges blunt through the humility and loss of trust she experienced. If Xander had come out of that experience having learned something i’d like him better for the bulk of the season. I didn’t see a lot of change in him until here at the very end, when he apologizes to Cordelia by helping her buy her dress with no expectation of reward, and covering for her to keep from embarrassing her even though cutting each other down is how they flirt/their favorite past time. And to be fair him bouncing off of Wish Girl and picking his friends over running away from danger with her is good development and did warm me to him more than previous episodes, but it was a clunky method of doing that. Really it felt like the script didn’t want to pay him any more attention than “comedy monkey” until the reviews started coming in and his approval rating dropped. I don’t know if that IS the case? I wasn’t there and have no references, but that’s what it felt like. I hope this gaining of facets continues in season 4 and we get to watch him meaningfully grow and change in response to his decisions and circumstances. Up until this point I had no idea why Buffy or Willow hung out with him.

i know I’ve picked Xander as a bit of a sticking point. If you guys think I’m being unfair to him, I apologize. He aggravates an exposed nerve in me, and I’m aware he’s a product of his time. My present and his history have not been kind and my anger comes mostly from the disappointment of me hoping for better.

Overall, though, Joss Whedon’s clippy writing style was strong as ever :) his subversion of his own tropes has started to kick in, which keeps the writing fresh and funny. Giles and Cordelia are still my favorites. I also like Willow and Buffy a lot. I won’t really miss Angel, mostly because I knew his departure was coming. i’m sure he’ll make another appearance at some point when the casts cross over. I think being without him will give Buffy a chance to grow in a new direction the way she did with Faith. i’m also glad the show is letting everyone advance to college! New places will bring new people and new challenges -- especially now that the high school has blown up. Let’s get started!

RIP principal snyder.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why Pride and Prejudice is the best love story of all time and the deconstruction of love at first sight

Perhaps everybody has heard, read or watched a story about love at first sight. It’s a cliché that always works in movies. The quirky girl, in a hurry to get to a meeting, stumbles on a grumpy man in the middle of the street and he lets all his stuff fall down. Both bend over to gather his things that are on the street and, for a second, only a second, the girl is not in a hurry anymore and the man’s soul is light as a summer day. That’s it, the passion is born. It’s simple, easy, and works almost every time.

Despite its efficiency in fiction, it’s always rather weird to apply this concept in real life -- to believe someone can fall in love without even knowing the other person. I, personally, can’t imagine falling for someone that supports Trump, or that hates Harry Potter. And you can’t identify these things just by looking at someone.

So why do we so easily believe in the concept that love can overcome anything? That’s another weird-ass concept; should love truly overcoming every single obstacle? If I ever fall in love with a misogynist serial killer, please, rescue me from that trap!! There will never be enough attraction to overcome so many differences. And so we go back to love at first sight: even if I fell in love with someone just by looking at them, I think it’s unlikely I’d still be in love after actually getting to know them.

My favorite love stories are the ones in which none of the central characters is interested in one another when they first meet. The “love at first sight” trope (or: a cliché or allegory used in fiction in order to develop characters or plots) is still recurrent in literature, but many books have been trying to subvert this cliché; such as Fangirl, by Rainbow Rowell, or The Raven Cycle series by Maggie Stiefvater. Both are pretty recent examples – Fangirl was released in 2014 and The Raven Cycle started in 2012. Maybe the subversion of love at first sight is a recent phenomenon, but long before any of these books were published, long before these authors were even born, we already had a good example of a love story in which love itself is a construction that takes a lot of time, and its title is Pride and Prejudice, written by Jane Austen.

2017 marked the 200th anniversary of the author’s death and the 204 years that passed since the first publication of the novel which is perhaps the most iconic Jane Austen wrote. Despite being two hundred years old, Pride and Prejudice is one of those timeless stories. It’s a classic.

In Why read the classics Italo Calvino explains that a classic is a book you always re-read; because if it’s a classic everyone already knows the plot, so even if it’s the reader’s first time with that specific book, she’s revisiting it nonetheless. We can say Pride and Prejudice is a classic because it’s a story that everyone knows: girl meets boy, girl hates boy, time goes by and the guy shows himself worthy of the girl’s affection and both declare they love for each other. Happy ending. It’s not by chance that Jane Austen’s story has inspired many modern adaptations, such as the Bridget Jones’ Diary series, Pride and Prejudice and Zombies, or even the amazing web series The Lizzie Bennet Diaries. Pride and Prejudice remains relevant nowadays.

Even though I agree with Italo Calvino, I want to add here another factor that makes Pride and Prejudice a classic: identification. If the characters of the novel were not well developed, so complex that they seem real, a great portion of the strength of the book would not exist. Even more so because in real life people can change their minds, they can turn out wrong and have strong opinions that sometimes lead to mistakes or misjudgments. Being wrong is not necessarily equivalent to being a bad person; actually, those are pretty different things. We are all wrong at some point in our lives – or in many of them. And that’s fine, because we can all realize the mistake, apologize and become better. People can always – and should always – become better, listen to others, empathize and stay away from prejudices. Elizabeth Bennet and Mr. Darcy, the heroes of the story, make mistakes, misjudge each other and others, are prideful and prejudiced, but also regret their mistakes, apologize and become better.