#眞雷

Text

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

各地句会報

花鳥誌 令和5年5月号

坊城俊樹選

栗林圭魚選 岡田順子選

………………………………………………………………

令和5年2月2日

うづら三日の月花鳥句会

坊城俊樹選 特選句

厨女も慣れたる手付き雪掻す 由季子

闇夜中裏声しきり猫の恋 喜代子

節分や内なる鬼にひそむ角 さとみ

如月の雨に煙りし寺の塔 都

風花やこの晴天の何処より 同

(順不同特選句のみ掲載)

………………………………………………………………

令和5年2月4日

零の会

坊城俊樹選 特選句

暗闇坂のチャペルの春は明日あたり きみよ

長すぎるエスカレーター早春へ 久

立春の市の算盤振つてみる 要

冬帝と暗闇坂にすれ違ふ きみよ

伊達者のくさめ名残りや南部坂 眞理子

慶應の先生眠る山笑ふ いづみ

豆源の窓より立春の煙 和子

供華白く女優へ二月礼者かな 小鳥

古雛の見てゐる骨董市の空 順子

古雛のあの子の部屋へ貰はれし 久

岡田順子選 特選句

暗闇坂のチャペルの春は明日あたり きみよ

冬帝と暗闇坂にすれ違ふ 同

大銀杏八百回の立春へ 俊樹

豆源の春の売子が忽と消え 同

コート脱ぐ八咫鏡に参る美女 きみよ

おはん来よ暗闇坂の春を舞ひ 俊樹

雲逝くや芽ばり柳を繰りながら 光子

立春の蓬髪となる大銀杏 俊樹

立春の皺の手に売るくわりんたう 同

公孫樹寒まだ去らずとのたまへり 軽象

(順不同特選句のみ掲載)

………………………………………………………………

令和5年2月4日

色鳥句会

坊城俊樹選 特選句

敬な信徒にあらず寒椿 美穂

梅ふふむ野面積む端に摩天楼 睦子

黄泉比良坂毬唄とほく谺して 同

下萌や大志ふくらむ黒鞄 朝子

觔斗雲睦月の空に呼ばれたる 美穂

鼻歌に二つ目を割り寒卵 かおり

三路のマネキン春を手招きて 同

黄金の国ジパングの寒卵 愛

潮流の狂ひや鯨吼ゆる夜は 睦子

お多福の上目づかひや春の空 成子

心底の鬼知りつつの追儺かな 勝利

(順不同特選句のみ掲載)

………………………………………………………………

令和5年2月6日・7日

花鳥さざれ会

坊城俊樹選 特選句

潮騒を春呼ぶ音と聞いてをり かづを

水仙の香り背負うて海女帰る 同

海荒るるとも水仙の香の高し 同

坪庭の十尺灯篭日脚伸ぶ 清女

春光の中神島も丹の橋も 同

待春の心深雪に埋もりて 和子

扁額の文字読めずして春の宿 同

砂浜に貝を拾ふや雪のひま 千加江

村の春小舟ふはりと揺れてをり 同

白息に朝の公園横切れり 匠

風花や何を告げんと頰に触る 笑子

枝川やさざ波に陽の冴返る 啓子

(順不同特選句のみ掲載)

………………………………………………………………

令和5年2月8日

さくら花鳥会

岡田順子選 特選句

雪を踏む音を友とし道一人 あけみ

蠟梅の咲き鈍色の雲去りぬ みえこ

除雪車を見守る警備真夜の笛 同

雪掻きの我にエールや鳥の声 紀子

握り飯ぱりりと海苔の香を立て 裕子

(順不同特選句のみ掲載)

………………………………………………………………

令和5年2月10日

鳥取花鳥会

岡田順子選 特選句

東風に振る竿は灯台より高く 美智子

月冴ゆる其処此処軋む母の家 都

幽やかな烏鷺の石音冴ゆる夜 宇太郎

老いの手に音立て笑ふ浅蜊かな 悦子

鎧着る母のコートを着る度に 佐代子

老いし身や明日なき如く雪を掻く すみ子

(順不同特選句のみ掲載)

………………………………………………………………

令和5年2月11日

枡形句会

栗林圭魚選 特選句

朝光や寺苑に生るる蕗の薹 幸風

大屋根の雪解雫のリズム良き 秋尚

春菊の箱で積まれて旬となる 恭子

今朝晴れて丹沢颪の雪解風 亜栄子

眩しさを散らし公魚宙を舞ふ 幸子

流れゆくおもひで重く雪解川 ゆう子

年尾句碑句帳に挟む雪解音 三無

クロッカス影を短く咲き揃ふ 秋尚

あちらにも野焼く漢の影法師 白陶

公魚や釣り糸細く夜蒼し ゆう子

(順不同特選句のみ掲載)

………………………………………………………………

令和5年2月13日

枡形句会

栗林圭魚選 特選句

犬ふぐり大地に笑みをこぼしけり 三無

春浅しワンマン列車軋む音 のりこ

蝋梅の香りに溺れ車椅子 三無

寒の海夕赤々漁終る ことこ

陽が風を連れ耀ける春の宮 貴薫

青空へ枝混み合へる濃紅梅 秋尚

土塊に春日からめて庭手入 三無

夕東風や友の消息届きけり 迪子

ひと雨のひと粒ごとに余寒あり 貴薫

(順不同特選句のみ掲載)

………………………………………………………………

令和5年2月13日

武生花鳥俳句会

坊城俊樹選 特選句

浅春の眠りのうつつ出湯泊り 時江

老いたれば屈託もあり毛糸編む 昭子

落としたる画鋲を探す寒灯下 ミチ子

春の雪相聞歌碑の黙続く 時江

顔剃りて少し別嬪初詣 さよ子

日脚伸ぶ下校チャイムののんびりと みす枝

雪解急竹はね返る音響く 同

寒さにも噂にも耐へこれ衆生 さよ子

蕗の薹刻めば厨野の香り みす枝

(順不同特選句のみ掲載)

………………………………………………………………

令和5年2月14日

萩花鳥会

水甕の薄氷やぶり野草の芽 祐子

わが身共老いたる鬼をなほ追儺 健雄

嗚呼自由冬晴れ青く空広く 俊文

春の園散り散り走る孫四人 ゆかり

集まりて薄氷つつき子ら遊ぶ 恒雄

山々の眠り起こせし野焼きかな 明子

鬼やらひじやんけんで勝つ福の面 美惠子

………………………………………………………………

令和5年2月15日

福井花鳥会

坊城俊樹選 特選句

吹雪く日の杣道隠す道標 世詩明

恋猫の闇もろともに戦かな 千加江

鷺一羽曲線残し飛び立てり 同

はたと止む今日の吹雪の潔し 昭子

アルバムに中子師の笑み冬の蝶 淳子

寒鯉の橋下にゆらり緋を流す 笑子

雪景色途切れて暗し三国線 和子

はよしねまがつこにおくれる冬の朝 隆司

耳目塗り潰せし如く冬籠 雪

卍字ケ辻に迷ひはせぬか雪女 同

(順不同特選句のみ掲載)

………………………………………………………………

令和5年2月16日

伊藤柏翠記念館句会

坊城俊樹選 特選句

指先に一つ剥ぎたる蜜柑の香 雪

大寒に入りたる水を諾ひぬ 同

金色の南無観世音大冬木 同

産土に響くかしは手春寒し かづを

春の雷森羅万象𠮟咤して 同

玻璃越しに九頭竜よりの隙間風 同

気まぐれな風花降つてすぐ止みて やす香

寒紅や見目安らかに不帰の人 嘉和

波音が好きで飛沫好き崖水仙 みす枝

音待てるポストに寒の戻りかな 清女

女正月昔藪入り嫁の里 世詩明

(順不同特選句のみ掲載)

………………………………………………………………

令和5年2月17日

さきたま花鳥会

坊城俊樹選 特選句

奥つ城に冬の遺書めく斑雪 月惑

顔隠す一夜限りの雪女郎 八草

民衆の叫びに似たる辛夷の芽 ふじほ

猫の恋昼は静かに睨み合ひ みのり

薄氷に餓鬼大将の指の穴 月惑

無人駅青女の俘虜とされしまま 良江

怒号上げ村に討ち入る雪解川 とし江

凍土を突く走り根の筋張りて 紀花

焼藷屋鎮守の森の定位置に 八草

爺の膝捨てて疾駆の恋の猫 良江

(順不同特選句のみ掲載)

………………………………………………………………

令和5年2月19日

風月句会

坊城俊樹選 特選句

古玻璃の奥に設ふ古雛 久

笏も扇も失せし雛の澄まし顔 眞理子

日矢さして金縷梅の縒りほどけさう 芙佐子

梅東風やあやつり人形眠る箱 千種

春風に槻は空へ細くほそく ます江

山茱萸の花透く雲の疾さかな 要

貝殻の雛の片目閉ぢてをり 久

古雛髪のほつれも雅なる 三無

ぽつねんと裸電球雛調度 要

栗林圭魚選 特選句

紅梅の枝垂れ白髪乱さるる 炳子

梅園の幹玄々と下萌ゆる 要

濃紅梅妖しきばかりかの子の忌 眞理子

貝殻の雛の片目閉ぢてをり 久

古雛髪のほつれも雅なる 三無

老梅忌枝ぶり確と臥龍梅 眞理子

山茱萸の空の広さにほどけゆく 月惑

八橋に水恋うてをり猫柳 芙佐子

(順不同特選句のみ掲載)

………………………………………………………………

令和5年2月21日

鯖江花鳥句会

坊城俊樹選 特選句

師を背負ひ走りし人も雪籠 雪

裏庭開く枝折戸冬桜 同

天帝の性こもごもの二月かな 同

適当に返事してゐる日向ぼこ 一涓

継体の慈愛の御ん目雪の果 同

風花のはげしく風に遊ぶ日よ 洋子

薄氷を踏めば大空割れにけり みす枝

春一番古色の帽子飛ばしけり 昭上嶋子

鉤穴の古墳の型の凍てゆるむ 世詩明

人の来て障子の内に隠しけり 同

春炬燵素足の人に触れざりし 同

女正月集ふ妻らを嫁と呼ぶ 同

(順不同特選句のみ掲載)

………………………………………………………………

令和5年2月26日

月例会

坊城俊樹選 特選句

能舞台昏きに満ちて花を待つ 光子

バス停にシスターとゐてあたたかし 要

空に雲なくて白梅すきとほる 和子

忘れられさうな径の梅紅し 順子

靖国の残る寒さを踏む長靴 和子

孕み猫ゆつくり進む憲兵碑 幸風

石鹸玉ゆく靖国の青き空 緋路

蒼天へ春のぼりゆく大鳥居 はるか

岡田順子選 特選句

能舞台昏きに満ちて春を待つ 光子

直立の衛士へ���が香及びけり 同

さへづりや鉄のひかりの十字架へ 同

春の日を溜め人を待つベンチかな 秋尚

春風や鳥居の中の鳥居へと 月惑

料峭や薄刃も入らぬ城の門 昌文

梅香る昼三日月のあえかなり 眞理子

春陽とは街の色して乙女らへ 俊樹

(順不同特選句のみ掲載)

………………………………………………………………

令和5年2月

九州花鳥会

坊城俊樹選 特選句

ポケットの余寒に指を揉んでをり 勝利

黒真珠肌にふれたる余寒かな 美穂

角のなき石にかくれて猫の恋 朝子

恋仲を知らん顔して猫柳 勝利

杖の手に地球の鼓動下萌ゆる 朝子

シャラシャラとタンバリン佐保姫の衣ずれ ひとみ

蛇穴を出て今生の闇を知る 喜和

鷗外のラテン語冴ゆる自伝かな 睦古賀子

砲二門転がる砦凍返る 勝利

小突かれて鳥と屋や に採りし日寒卵 志津子

春一番歳時記の序を捲らしむ 愛

(順不同特選句のみ掲載)

………………………………………………………………

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

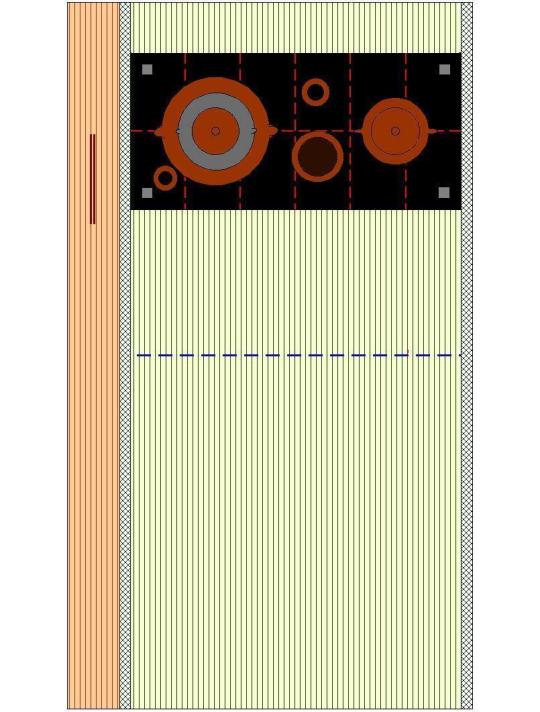

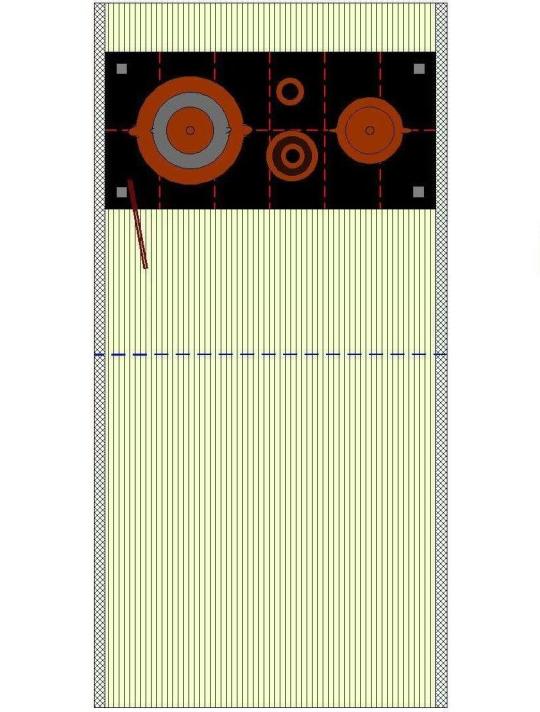

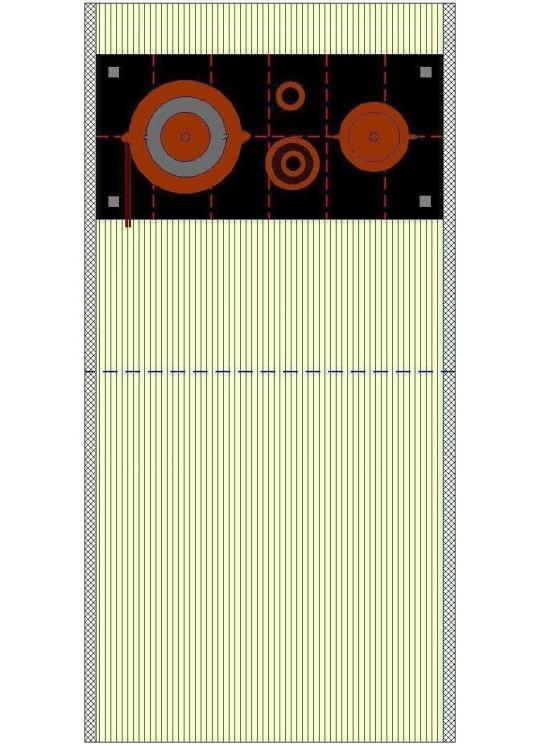

Nampō Roku, Book 7 (53): Displaying the Incense Utensils on the Daisu.

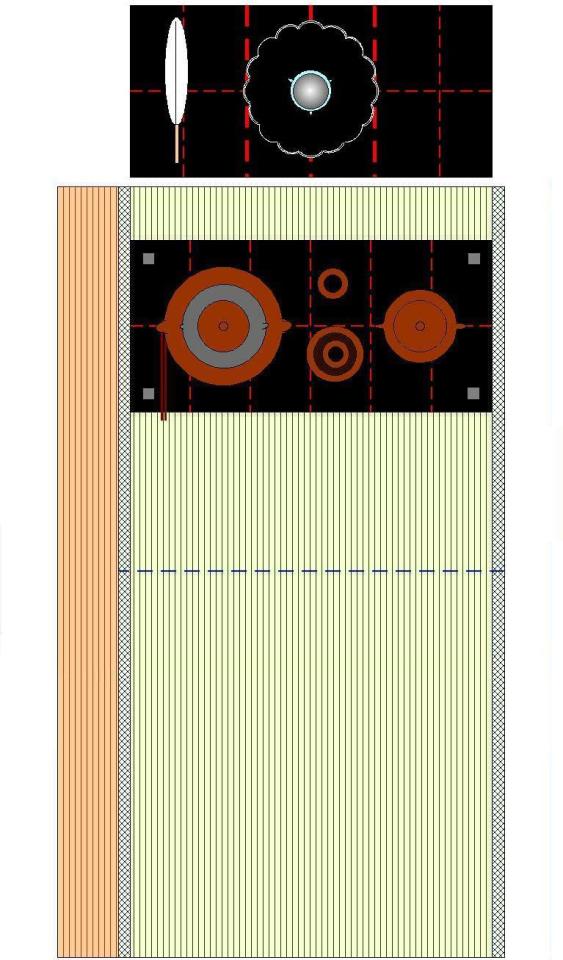

53) With respect to the shin [眞] display of the kōro, if [the host] wants to display the kyōji・koji-tate [on the tray of incense utensils], then the hibashi should not be [placed] in the shaku-tate on the daisu¹.

If the incense [is going to be appreciated] during the later [half of the gathering], when charcoal will be added [to the furo] again later, [the hibashi] should be brought out together with the sumi-tori². Then [at the conclusion of this second sumi-temae] they should be placed on the go-sun-ita [五寸板] to the right of the nagaita [the ji-ita of the daisu], [oriented] so that the heads [of their handles] are forward³.

〚But when incense will be appreciated during the first [part of the gathering], during the initial arrangement [of the daisu], it is acceptable for [the hibashi] to be placed on the nagaita [ji-ita], as has been described previously [in Book Five]⁴. When the tadon is picked up, the hibashi should be used⁵. It is prudent to use the hibashi [for this purpose, rather than the koji]⁶.〛

In an ordinary arrangement, both the hishaku and hibashi should be [displayed] in the shaku-tate [at the beginning of the gathering]⁷. When charcoal is added before the service of the food, because [the hibashi] are put into the sumi-tori and taken in[to the katte], when tea is served after the meal, the hibashi are not [present in the shaku-tate]⁸. 〚And when tea is finished, if [the host] wishes to add charcoal [to the furo] yet again, the hibashi should be left out of the shaku-tate⁹.〛

There is the case where usucha is prepared with the hibashi standing [in the shaku-tate] -- though this makes it difficult to take up the hishaku¹⁰. In this kind of situation, the hishaku should not be stood in the shaku-tate during the temae¹¹.〚This [kind of thing] is done when usucha is served spontaneously, without its having been planned beforehand [-- such as when the daisu was put out in a reception room as a decoration only, but then the guests suddenly ask to be served tea from it]¹².〛

〚When koicha is served after the meal, followed by usucha, whether or not to stand the hishaku in the shaku-tate [throughout both temae, after each time the hishaku was been used] is up to [the host’s] discretion¹³.〛

_________________________

◎ As is often the case in Book Seven, Shibayama Fugen’s teihon includes about a third more material that is missing from the Enkaku-ji version of the text. Since the differences could suggest that parts of the original were omitted or lost*, I have restored those portions of the text in the above translation -- enclosed in doubled brackets, as usual -- since they make the text significantly more intelligible.

___________

*Another possibility is, because the omitted material generally provides the reader with clear and logical explanations for points in the text that are otherwise obscure, these things may have been added (as marginalia) by the Enkaku-ji scholars later, during their review of this entry (the text that Shibayama used as his teihon was provided to him by one of the Enkaku-ji scholars, and represented that individual’s personal copy of the work, and it may have included his own explanatory interpolations without their having been marked as such).

At any rate, the additions do seem to be historically accurate, and so are enlightening to our study of chanoyu.

¹Shin no kōro kazari ni, kyōji・koji-tate wo kazaritaru toki ha, daisu no shaku-tate ni hibashi ha nashi [眞ノ香爐カザリニ、キヤウジ・コジ立ヲカザリタル時ハ、臺子ノ杓立ニ火バシハナシ].

Shin no kōro kazari [眞の香爐飾り] refers to the display of the kōro by itself, tied in its shifuku, and resting on a tray (similar to a bon-chaire).

In Book Five, this arrangement discussed in the post entitled Nampō Roku, Book 5 (47): the Shin [眞] Way to Display a Meibutsu Kōro*.

In that entry, the meibutsu incense burner was displayed, tied in its shifuku, on the Chōshō rai-bon [趙昌雷盆]†. However, in this case, the kyōji・koji-tate is not displayed on the daisu, but, rather, is carried out from the katte when incense will be appreciated -- suggesting that the author of this entry was not clear regarding the distinction between the shin no kōro kazari [眞の香爐飾り] and the sō no koro kazari [草の香爐飾り]‡.

Shibayama Fugen, therefore, directs the reader’s attention to several earlier entries (that depict the sō [草] arrangement -- where the kōro is displayed on the kō-bon along with the kyōji・koji-tate, kōgō, and taki-gara-ire)**.

Shibayama’s version of this sentence ends with the word tatezu [タテズ = 立ず], meaning (the hibashi) are not stood (in the shaku-tate) -- rather than nashi [ナシ = 無し], which means (the hibashi) are not present (in the shaku-tate), as the Enkaku-ji manuscript has it. But the meaning is identical.

__________

*The URL for that post is:

https://chanoyu-to-wa.tumblr.com/post/630719089136025600/namp%C5%8D-roku-book-5-47-the-shin-%E7%9C%9E-way-to

The sketch depicts the hibashi resting on the ji-ita of the daisu, to the left of the furo. This was done when the appreciation of incense would be done first (as was the Shino family’s preference), since the hibashi were used to extract the tadon (the burning charcoal briquette used as the heat source for the kōro). If the appreciation of incense was going to be done following the sumi-temae (this was one of Jōō’s modifications), then the hibashi were displayed in the shaku-tate. In either case, they were removed from the room after use.

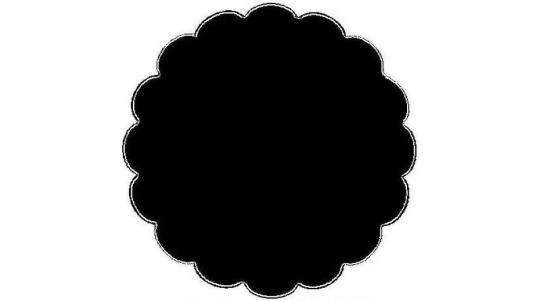

†The Chōshō rai-bon [趙昌雷盆] (often referred to simply as the rai-bon [雷盆]) had a foliated rim, that measured 1-shaku 1-sun in diameter.

The face of the original imported tray was decorated with gold maki-e and mother-of-pearl inlay, depicting grassy flowers and foliage.

Haneda Gorō's reproduction was done in kagami-nuri, without any other sort of decoration, and this is the sort occasionally encountered today.

According to Tanaka Senshō’s commentary, the naka maru-bon [大丸盆] (which measured 1-shaku 2-sun 3-bu in diameter, and had a brass plate featuring a dragon design inset into the face of the tray) was also used for the shin no kōro kazari.

‡In Book Five only the shin [眞] and sō [草] arrangements are described, so it is possible that there were no “gyō” [行] versions (the shin-gyō-sō [眞行草] trichotomy was not really a “thing” until the Edo period).

The various arrangements where incense utensils are displayed on the daisu were usually associated with the Shino family (even though some of them certainly date back to Yoshimasa), and as antagonism between the arts was being encouraged during the Edo period, the ignorance displayed by the author is likely the result of this artificial separation.

None of the founding generations of any of the classical arts can be said to have lived or functioned in such a cultural vacuum -- the Shino were skilled in chanoyu, one section of Ikenobō Sen-ō collected teachings is dedicated to incense, and Rikyū was Hideyoshi’s master of the rikka [立華] (which was, and remains, the highest form of ikebana).

Yet the absence of all of the entries that touch on incense from Kumakura Isao’s supposedly complete Nampō Roku wo yomu [南方録を読む] is proof that this Edo period sentiment is still alive and well (in Japan) today.

**Shibayama Fugen refers the reader to the following entries:

◦ Nampō Roku, Book 5 (39): the Sō [草] Form of the Display of a Kōro [香爐] -- Before and After, [One] of Three [Arrangements].

https://chanoyu-to-wa.tumblr.com/post/629088351517032448/namp%C5%8D-roku-book-5-39-the-s%C5%8D-%E8%8D%89-form-of-the

◦ Nampō Roku, Book 5 (40, 41): the Sō [草] Form of the Display of a Kōro [香爐] (Continued).

https://chanoyu-to-wa.tumblr.com/post/629450736690937856/namp%C5%8D-roku-book-5-40-41-the-s%C5%8D-%E8%8D%89-form-of

²Ato no kō ni ha ato no sumi-tsugu-toki, sumi-tori ni tsukete dasu [後ノ香ニハ後ノ炭ツグ時、炭トリニツケテ出].

Ato no kō [後の香] refers to a gathering during which incense will be appreciated during the goza.

Ato no sumi-tsugu-toki [後の炭次ぐ時] means when charcoal will be added later (i.e., this is referring to the go-sumi-temae [後炭手前]). While Rikyū said that charcoal should be added only once, he was referring to the situation in the wabi small-room setting. In the case of the daisu, the fire should be made no larger than necessary, since if the furo gets too hot, it will damage the ji-ita of the daisu. Thus, if the host is serving tea to more than one guest*, it will be necessary to add more charcoal (usually between the service of koicha and the service of usucha), otherwise there will be a danger that the fire will begin to fail before the host is finished.

Sumi-tori ni tsukete dasu [炭斗に付けて出す] means (the hibashi) are brought out in the sumi-tori†.

___________

*Originally, serving tea from the daisu was done only for the nobleman-shōkyaku.

This derived from the original idea, where a single bowl of tea was made and offered to the Buddha -- and then drunk by either the person who prepared the tea, or by the person designated (usually the highest-ranking individual present) when other people were observing the temae. While originally done as a kind of meditative practice, humans being humans, certain monks would have a more beautiful technique, and this could attract a crowd; and, of course, Buddha was also served tea in this way on formal occasions, as part of the day’s religious ceremonies. It was in this context that one of the observers was invited to drink the tea (usually the abbot invited that person to drink the tea in his own stead, since normally the abbot was the highest ranked figure present). Ultimately, this was simply so that the tea would not go to waste (from the beginning, since tea for matcha was only harvested during an eleven-day period that centered on the feast day of Yakushi nyorai [藥師如来], the “Buddha of Healing,” which was observed on the 88th day of the Lunar year), because it was rare and so precious, and so it would be wrong to throw it away (the Buddha statue being unable to drink it, after all).

†After they were used to add charcoal to the furo during the shoza, the hibashi were considered impure. Thus, they could not be returned to the shaku-tate again during that gathering (even if they were cleaned thoroughly).

Apparently it was the change to a new gathering that ritually purified them, thus permitting them to be displayed in the shaku-tate once again.

³Sate nagaita no migi no kata go-sun-ita no ue ni oki, kashira wo mae ni shite oku-koto mochiron nari [サテ長板ノ右ノ方五寸板ノ上ニ置、頭ヲ前ニシテヲクコト勿論也].

Nagaita [長板] is the term used in the Nampō Roku for the ji-ita of the daisu.

Go-sun-ita [五寸板] was a board that was found along two sides of the classical 4.5-mat shoin (to make up the difference between the size of the original Japanese room, called a hōjō [方丈]*, and the size of the kyōma mats that were imported from Korea).

The two sides were along the front of the jō-dan (tokonoma), and along the side of the room, where the daisu was set up (usually with the veranda, that functioned as the mizuya, on the opposite side of the bank of shōji that formed that side of the room), as shown above.

Nagaita no migi no kata go-sun-ita no ue ni oki [長板の右の方五寸板の上に置き] is expressed in the following drawing.

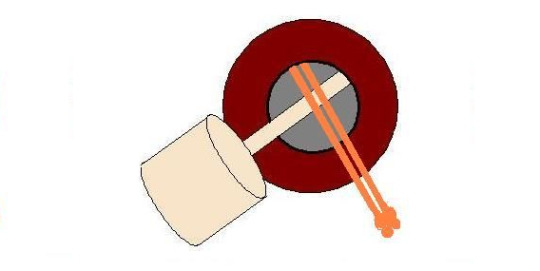

Kashira wo mae ni shite [頭を前にして] means the ends of the handles of the hibashi (which were often tipped with decorative elements, even miniature sculptures -- for example, Rikyū’s hibashi had tiny sculptures representing the head of one of the ancient sages) should be on the side closest to the host’s knees.

The kashira on the pictured hibashi are called chorogi [長呂木] (which is the name of a kind of snail that has a shell somewhat shaped like that).

Mochiron [勿論] means naturally, of course. The kashira are oriented closest to the host’s body because it is from that end that the hibashi are picked up (since the other end, which touches the charcoal, is potentially dirty with charcoal dust).

Here Shibayama’s teihon has a very different take on the way to handle the hibashi. That text reads: nagaita no migi no kata, futaoki on tokoro ni kashira wo mae ni shite oki-awase suru nari [長板ノ右ノ方、蓋置ノ所ニ頭ヲ前ニシテ置合スル也], which means that the hibashi were leaned against the ji-ita, at the place where the futaoki was usually displayed (in the left front corner, between the furo and the left front leg).

This was probably done in a room that lacked a go-sun-ita (which had become normalized over the course of the Edo period), and so reflects the condition of things at the time when Shibayama Fugen’s teihon was written.

This is the only difference between the two texts that I did not include in the translation -- because it clearly reflects a later development that would not have been usual during Rikyū’s period or before.

___________

*Hōjō [方丈] means a square room that measured 1-jō [丈] (approximately 10 shaku) on the side: this is indicated in the drawing with the dashed red line.

The difference between the traditional square room (which was considered the appropriate amount of space in which one person could live comfortably) and the square composed of four and a half kyōma tatami was 5-sun in each direction. Rather than rebuild the old rooms, the solution was to fill up the difference with a board of the same height as the mats, forming a sort of sill on two sides.

⁴Hatsu no kō no wake ha hatsu no kazari ni migi no gotoki nagaita ni okite yoshi [初ノ香ノ分ハ初ノ飾ニ如右長板ニ置テヨシ].

This sentence is found only in Shibayama’s teihon.

Hatsu no kō no wake [初の香の分] means on occasions (wake [分]) when incense will be appreciated at the beginning (of the shoza)....

Hatsu no kazari ni...nagaita ni okite yoshi [初の飾に...長板に置きてよし] means during the initial kazari (hatsu no kazari ni [初の飾に]) -- that is, the way the daisu is arranged when the guests enter the room for the shoza; nagaita ni okite yoshi [初の飾に長板に置きてよし] means it is better (yoshi [よし]) if the hibashi are placed (okite [置きて]) on the ji-ita of the daisu (which is called the nagaita [長板] in the Nampō Roku, as mentioned above).

The reason, once again, is because when the appreciation of incense will take place at the beginning of the shoza -- before the charcoal has been added to the furo -- it is best if the hibashi are placed on the ji-ita, since removing them at that time would disturb the hishaku.

Note that this was done whether the room had a go-sun-ita or not†.

___________

*The futaoki should be placed inside the koboshi on such occasions, since the hibashi will occupy its usual space (according to the way the kaigu are distributed across the ji-ita in nanatsu-kazari [七ツ飾]).

Traditionally, it was felt that the hoya should not be treated in this manner. When the hibashi will be rested on the ji-ita, the futaoki should be of some other kind (that is, any of the others of the seven meibutsu futaoki, as well as simple ring futaoki, such as those seen in most kaigu sets manufactured today). Only the hoya, and the Rinzai-in [臨濟印], were proscribed from this kind of informal handling.

†In a sense, it indicates that the hibashi are pure -- just as displaying them in the shaku-tate does.

⁵Tadon hasamu tame ni hibashi wo mochiiru-koto ari [タトンハサム爲ニ火箸ヲ用ルコトアリ].

This sentence, too, is found only in Shibayama Fugen’s teihon (both were probably marginalia, rather than actual parts of the original text).

The tadon [炭團], which is a small cylindrical briquette made from crushed high-quality charcoal (charcoal that does not give off any scent when burned), is set alight by placing it inside the furo, next to the shita-bi. Since incense will be appreciated before the sumi-temae, the tadon is removed through the himado (the “window” in the front of the furo), so that lifting the kama off of the furo is unnecessary. To facilitate this, the mae-kawarake [前土器] (the semicircular ceramic tile that is placed in the front of the fire, to prevent sparks from shooting out through the hi-mado) is left out when the ash is shaped.

The tadon is removed using the hibashi, and then placed into the haiki* (the ash from which is then used to repair the hai-gata, if necessary, using the hai-saji that is placed in the hai-ki). Then, using either the hibashi, or the koji (the miniature hibashi that were part of the set of incense implements), the tadon is moved into the incense burner.

The koji [コジ = 火筋] (the miniature hibashi that are included in the set of incense utensils that are stood in the kyōji・koji-tate [香筋・火筋建]) cannot be used for this purpose, because they are much too short†. Only the longer hibashi that are used to arrange the charcoal in the furo can be used for this purpose†.

___________

*According to Rikyū, this was the only time that a haiki was ever supposed to be brought out when the furo was being used.

Other than when incense would be appreciated, the haiki was reserved to the ro, only.

†Their intended purpose was to lift the burning tadon out of the akoda-kōro [阿古陀香爐] and lower it into the kiki-kōro [聞き香爐] that was resting on a tray at its side. Thus the koji were only long enough so there would be no danger of the host’s burning his fingers during this brief operation.

‡Not only would the greater length aid the host in picking up the tadon, but it would also allow him to do so without risking damage to the upper edge of the hai-gata.

In a sense, displaying the hibashi on the ji-ita is a way for the host to inform his guests that the appreciation of incense will take place at the beginning of the shoza -- rather than at some other point during the chakai (alternate times would be between the sumi-temae and the kaiseki; and after the service of usucha has been concluded during the goza -- which is why the hibashi were supposed to be left on the go-sun-ita, or leaning against the ji-ita, following the go-sumi-temae, when incense will be appreciated “later”).

⁶Sono yōjin ni hibashi aru-beki nari [其ノ用心ニ火箸可有也].

Yōjin ni [用心に] means as a precaution; by way of precaution.

In other words, it is prudent that the host should use the hibashi for the purpose of extracting the tadon through the himado, rather than the koji [火筋] (the miniature hibashi that are included in the set of incense utensils).

⁷Tsune no kazari ni shaku-tate ha hishaku to hibashi ari [常ノカザリニ杓立ハヒサクト火箸アリ].

Tsune no kazari ni [常の飾りに] means during ordinary arrangements (that is, on occasions when incense will not be appreciated in the way we are discussing here).

Shaku-tate ha hishaku to hibashi ari [杓立は柄杓と火箸あり] means both the hishaku and hibashi are present in the shaku-tate.

Here we are referring only to the initial kazari. After the hibashi have been used to handle the charcoal, they cannot be returned to the shaku-tate again during that gathering.

⁸Ō-ban i-zen ni sumi-tsugu toki, sumi-tori ni tsukete tori-iri yue, shoku-go cha no toki hibashi ha nashi [椀飯已前ニ炭ツグ時、炭トリニツケテ取入ユヘ、食後茶ノ時火バシハ無シ].

Ō-ban [椀飯] literally means to serve food in lacquered wooden bowls (as opposed to communal dishes), and is, of course, referring to the kaiseki.

I-zen ni [已前に] means before, prior to. Here Shibayama’s teihon has i-zen ni [以前に], but this is the same word (just using the kanji that came to be preferred in more modern times).

Sumi-tsugu toki, sumi-tori ni tsukete tori-iri yue [炭次ぐ時、炭斗に付けて取り入りゆえ] means because (yue [ゆえ]), when charcoal is added (sumi-tsugu toki [炭次ぐ時], (the hibashi) are added to the sumi-tori (sumi-tori ni tsukete [炭斗に付けて]) and taken in (tori-iri [取り入り]) to the katte....

Shoku-go cha no toki hibashi ha nashi [食後茶の時火箸は無し] means when it is time for tea after the meal, (shoku-go cha no toki [食後茶の時]) there are no hibashi (hibashi ha nashi [火箸は無し) in the shaku-tate.

This simply reiterates what has been said above -- once the hibashi have been used, they cannot be returned to the shaku-tate again during that gathering.

⁹Cha sumite mata sumi wo tsugitaru toki, shaku-tate ni hibashi wo sashi-oki nari [茶濟テ又炭ヲツギタル時、杓立ニ火箸ヲサシ置也].

This qualification is found only in Shibayama Fugen’s teihon -- not because it was unimportant (or spurious), but because it was a given when chanoyu was performed with the daisu, and the appreciation of incense would follow.

Cha sumite mata sumi wo tsugitaru toki [茶濟て又炭を次たる時] means if charcoal is added again after the service of tea has been concluded*....

Shaku-tate ni hibashi wo sashi-oki nari [杓立に火箸を差し置きなり] means the hibashi should be excluded† from the shaku-tate.

___________

*This was a special practice, undertaken only when the appreciation of incense would follow the service of tea -- since it was considered bad form for the kama to fall completely silent while the guests were still in the room.

Later the Sen family appropriated this idea (which came to be called tome-zumi [止炭]) as a way to encourage the guests to tarry a little longer (so host and guests could chat among themselves freely -- without the distraction of preparing and drinking tea), before finally taking their leave.

Necessarily the idea went against Rikyū’s understanding of chanoyu, who said that in the wabi small room the host serves both koicha and usucha; and once usucha has been finished, there is nothing more to detain the guests, so they should depart.

†Sashi-oku [差し置く] means to push aside, discount, disregard, ignore, dismiss, and so forth.

¹⁰Hibashi tachi-awasetaru-toki, usucha-tateru-koto ari, hishaku tori-nikuki-mono nari [火箸立合セタルトキ、ウス茶立ルコトアリ、ヒサク取ニクキモノ也].

Hibashi tachi-awasetaru-toki [火箸立ち合せたる時] means (when) the hibashi are standing (in the shaku-tate)....

Usucha-tateru-koto ari [薄茶立てることあり], there is the case where usucha (might possibly be) served.

Hishaku tori-nikui-mono nari [柄杓取り難いものなり] means it is difficult to take up the hishaku.

This sentence seems rather confusingly vague -- since the author has already gone to great lengths to inform us that the hibashi are supposed to be removed from the room long before it is time for the host to serve usucha. Here Shibayama’s teihon provides us with an invaluable (indeed, an essential) piece of the puzzle: saru-yue fu-ji ni usucha-tateru toki, hibashi tachi-awase aru yue, hishaku tori nikuki-mono nari [然故不時ニ薄茶立ル時、火箸立合アル故、柄杓取ニクキ者ナリ].

Saru-yue [然るゆえ] means the reason for something like that....

Fu-ji ni [不時に] means something that was unexpected, something that was unforeseen, something that was done spontaneously. In other words, the service of usucha was not planned.

When decorating a reception room (such as the room in which guests waited to be received by someone like Hideyoshi), if there was a desire to display the daisu and other utensils (such as when the expected people had a known interest in chanoyu, and so would have been diverted by the examination of these objects -- so they would not become bored or impatient during their wait), the full daisu would be set up*, a fire would be put into the furo (so that the water would be boiling when the guests entered the room), and a chaire of matcha and some sort of chawan (with chakin, chasen, and chashaku arranged in it) would be displayed on the ten-ita -- all with no expectation of actually using these things to serve tea. Nevertheless (especially if the wait was drawn out), there was the possibility that the guests might ask to drink usucha, and the best way would be to use the daisu and other utensils for this purpose.

While the modern schools have inserted a step, at the beginning of the temae, whereby the hibashi are removed (and hidden away in the space between the katte-side of the daisu and the furosaki-byōbu that surrounds it), in the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries this kind of thing was as of yet undefined. Thus the usual response would seem to have been to attempt to serve tea with the hibashi left in place in the shaku-tate†.

___________

*This would include displaying the hibashi in the shaku-tate, since these were often extremely precious and beautiful objects (usually they were Korean bronze, and had been made as ceremonial tableware for the Goryeo king and his courtiers -- often featuring miniature sculptures on the ends of the handles, some of which were executed in contrasting metals).

†According to Rikyū, the hibashi are supposed to be inserted together so that they rest against the back side of the handle of the hishaku, with the hishaku inclined toward the kama, and the hibashi toward the host’s right hand (as shown below). Arranging them in this way would make it difficult to extract the hishaku without causing the hibashi to flop forward noisily (which could disquiet the guests, since it might damage the hibashi).

Imai Sōkyū and his followers, however, oriented the hishaku so that it faced directly forward, leaning against the front rim of the shaku-tate, with one hibashi on either side of the handle of the hishaku (and leaning against the far rim). This allowed for the possibility of the action that is described in this entry (which helps us understand that at least parts of this entry were written by someone connected with the machi-shū, rather than by Nambō Sōkei) -- though it would not be an especially gentle gesture (and reinserting the hishaku back into the shaku-tate at the end of the temae would prove more of a nuisance than the host might desire).

¹¹Sono-toki ha temae no ma hishaku wo shaku-tate ni yarazu ni tachi-beshi [其時ハ手前ノ間ヒサクヲ杓立ニヤラズニ立ベシ].

Originally, the hishaku was always returned to the shaku-tate every time it was used. It was never rested on the futaoki; and never rested on the mouth of the kama.

During the sixteenth century, the temae evolved so that, while the hishaku might be rested on the mouth of the kama (when it would be reused almost immediately -- such as when adding hot water twice to the koicha*), at all other times it was returned to the shaku-tate.

However, in this special case where usucha is being served while the hibashi are still standing in the shaku-tate, it is difficult to return the hishaku to the shaku-tate effortlessly. Thus, when serving usucha in this way, the hishaku was handled just as if the furo were resting on a shiki-ita, with no shaku-tate at all -- it was rested on the mouth of the kama; or if the kama would be closed, on the futaoki -- and then only returned to the shaku-tate at the end of the temae.

It is difficult to imagine that any of this would have been sanctioned by Rikyū.

___________

*Adding hot water twice while preparing the tea -- whether koicha or usucha -- was a feature of Jōō’s temae; and this idea, therefore, began with him.

Rikyū added hot water only once (whether he was making koicha or usucha), on the theory that the longer the preparation was prolonged, the more the taste of the tea would be affected for the worse.

¹²Kore fu-ji usucha no toki no koto nari [コレ不時ウス茶ノ時ノコトナリ].

This qualification is found only in Shibayama Fugen’s teihon.

This is underscoring the point that this kind of thing was to be only done when the service of usucha had not been expected when the daisu was set up (as described in footnote 10). At any other time, this breach of the proper etiquette would not have been permissible.

¹³Shoku-go koicha, ato no usucha ni ha, shaku-tate [h]e hishaku yaru mo kokoro-shidai nari [食後コイ茶、後ノウス茶ニハ、杓立ヘ柄杓ヤルモ心次第ナリ].

The orthodox way to perform the temae with the daisu included the idea that the shaku-tate was there for the sole purpose of giving the hishaku a place to stand when not being used.

During the Edo period, the Sen family began to use the daisu almost as if it were not there at all* -- that is, they performed an ordinary furo temae, resting the hishaku on the mouth of the kama, or on the futaoki, when not actually being used to dip and pour water.

The author recognizes that the chanoyu of most people is somewhere in between these two extremes, and so he added this comment -- which says that whether or not to stand the hishaku in the shaku-tate during the temae should be up to the host’s personal sense of what is the right way to do things†.

___________

*While the original daisu-temae had come first, and then been simplified into the temae of the furo, and the temae of the ro (as Rikyū explained), Sōtan’s wabi-cha temae came first, and his daisu temae was derived from his wabi-cha temae (with only those modifications that were necessary to accommodate the daisu and its kaigu).

†Which may also be a subtle way of suggesting that the host should actually think about what he is going to do, rather than just acting mindlessly.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

遺骨、酸初、初夏、夏至、我博、臨床、先客、那波区、東海、雲海、雲水、初楽、飼養、規律、滅法、頑丈、撃破化、内板、飼養、機咲州、分癖、蛾妙、頌栄、丼爆発、濃彩、恋欠、名瀬、徒歩機、歌詞役、素市、癌滅、元凶、願文、文座、同發、長門、至極、極美、呵責、端午、併合、奈落、底癖、幕府、某尺、尊式、検疫、未除、路側、柑橘、脂溶、瑛人、冠水、豪材、剤枠、土岐、駄泊、検尺、漏洩、破裂無言、任期、崩説、全滅、壊滅、開幕、統帥、頭数、水湿、冠水、抹消、網滅、馬脚、財冠水、風隙、来妙、勤学、餞別、名判、名盤、観客、衆院、才覚、無能、果餓死、損初、波脈、釋迦、損失、片脚、那古、可物、筋層、真骨、存廃、破格、名湯、今季、写楽、苦況、罪責、孫覇、全滅、今父、奈落、旋盤、秒読、読破、名物、貨客、泉質、随想、滅却、監理、素質、遡行、文滅、菜根、無端、庄屋、破壊、客率、合併、豪式、続発、泣塔、透析、頑迷、場脈、野張、船室、乾物、吐瀉分裂、戒行、噛砕、爾、晩別、海苔、西明、縁月、花月、独歩の大蛇、再発、納言、遺言、残債、背角、破壊、忠膵癌、統帥、馬車、下劣、火災、乱尺、毒妙、縫製、貨坂城、歳発、富低落、菜初、命式、山賊、海剤、激武者、瓦礫、破水、分裂、賀露、屠畜、能月、見激、破壊、破戒、採石、屈託、門別、皆来、家来、千四、我楽、夏楽、無慈悲、壊滅、破棄、損勤学、外鰓、長水、瑛人、永久、旋律、斑紋、財年、場滅、甘露、舐めけり、真靭、察作、論祭、乾裂、薩長、泣塔、室見、川縁、岩石、言後、荷火災、防爆、鋒鋩、体制、貨車、顎脚、刺客、坐楽、損益、脳系、文才、分合、合壁、啓発、萌姫、島内、監修、真木、合理、独房、雑居、紋発、乱射、雑念、五輪、三振、欄居、托鉢、紋腹、画狂、欠年、射殺、殺傷、脳初、目車、濫用、懸念、學年、身者、卓越、餓死、軟卵、場者、童空、我作、滅法、涅槃、抹殺、怒気、燃焼、略奪、宰相、馬腹、刳発、南山、活発、沙羅、割腹、殺戮、循環、奈良、菜道、紗脚、残雑、颯和、和歌、東風、南富、背面、焼却、四季、同發、博羅、無償、透明、明闇、雲海、陶酔、溺愛、泊雑、湖畔、花車、小雑、蘭風、雑魚寝、逆発、罵詈、検遇、明細、鳥羽、無数、飾西、涼感、割烹、面月、略発、明暗、御覧、絶滅、名者、焼却、野版、絶筆、数界、洒落、羈絆、四索、敏捷、旋律、脚絆、安行、軽安、難産、伊賀、消滅、生滅、巡数、水災、万華、論発、処住、崇拝、年月、画鋲、我流、剣率、草庵、律年、雑魚、規約、貨車、蒸発、重大、錯乱、蓮妙、奈良、坐楽、延宝、財年、爆発、龍翔、日向、塁側、席園、座札、風評、財年、何発、旋律、画狂、論券、戦法、尊師、大概、二者、那波、麺期、演説、合邦、放射、雑律、貨客、選別、燕順、考慮、試薬初、財源、富、符号、井原、若榴、清涼、無數、才覚、絶望、奈落、奔放、有識、台東、詮索、懸念、病状、設楽、宴客、怠慢、時期、同部、弁解、冊立、立案、前略、妄動、侮蔑、廃絶、間髪、図解、経略、発泡、者発、立案、滅鬼、自利、論酒、桜蘭、五月雨、垓年、処理、短髪、散乱、絶滅、命日、庵客、実庵、龍翔、派閥、同盟、連峰、焼殺、勝中、割裂、残虐、故事、量発、敗残、花夢里、面月、原氏、雑考、推理、焼殺、膵癌、導風、千脚、砂漠、漁師、活滅、放射、洋蘭、舞妓、邪武、涅槃、毛髪、白藍、他式、民会、参謀、廃車、逆発、峻峰、桜蘭、殺戮、銘客、随分、刺死、脳犯、我版、論旨、無垢、血潮、風泊、益城、拝観、舘察、懺悔、空隙、髭白、模試、散乱、投射、破滅、壊滅、下痢、他殺、改札、寿司、葉式、魔雑、渾身、等式、命日、安泰、白藍、良志久、中須、掻敷、北方、監視、血式、血流、詐欺、加刷、販社、壊滅、坐楽、白那、苫小牧、欄物、演説、開脚、摩擦、欠史、宰相、掻敷、飾西、近隣、可能、刺自虐、崑崙、独歩、良案、隔絶、菜作、妄動、犬歯、核別、概要、立案、破格、殺戮、良案、快絶、防止、那古、風別、焼安泰、独庵、囲炉裏、壊滅、外傷、刃角、視覚、耳鼻、下顎骨、子孫、剥奪、憂鬱、優越、液状、先端、焼子孫、兵法、那波、安楽、最短、数式、絶句、庵杭、雅樂、動乱、者妙、垓年、独初、前報、奈落、数道、弓道、拝観、俯瞰、散乱、男爵、害面、炎上、抹殺、破棄、分別、額欄、学雑、宴客、体面、村落、柿区、害初、告発、欄式、体罰、侮蔑、浄光、情動、差額、君子、何発、兵式、童子、飾西、各滅、我札、審議、半旗、普遍、動脈、外傷、無償、木別、別格、名皿部、京脚、破棄、試薬、絶滅、学札、清涼、爆発、組織、壊滅、ここに、名もなき詩を、記す。風水、万別、他国、先式、続発、非力、産別、嘉門、神興、撃易、弊社、紋別、座泊、画狂、式典、胞子、画力、座敷、学舎、論別、閉域、爆風、万歩、博識、残忍、非道、望岳、死骸、残骸、符合、壊滅、匍匐、弄舌癖、死者、分別、砂漠、白藍、模写、服役、奈落、忖度、符尾、同盟、田式、左派、具癖、退役、蛇路、素白、昆北、北摂、写経、文武、択液、図解、挫折、根塊、道厳、視野別、奈落、鳥羽、グリシャ・イェーガー、粗利、惨殺、学癖、優遇、陶器、場作、土壌、粉砕、餓鬼、草履、羅列、門泊、戸癖、山系、学閥、座枠、忠膵癌、視野別、脳族、監視、佐伯、釋迦、敏捷、遇歴、佐渡、名張、紀伊市、名刺、干瓢、夏至、楽節、蘇遇、列挙、間髪、風脚、滅法、呪水、遇説、死骸、爆発、山荘、塀楽、茗荷、谷底、愚者、妄動、還魂、色別、最座、雑載、論客、名足、死期、近隣、名張、迷鳥、呑水、飛脚、晩別、獄卒、殺傷、視覚、乱脈、鉱毒、財閥、漢詩、死語、諸富、能生、那波、合理、血中、根菜、明初、鹿楽、宮札、度劇、臥風、粋玄、我馬、洞察、今季、爾脈、羅猿、激園、葉激、風車、風格、道明、激案、合祀、坐楽、土地油、力別、焼殺、年配、念波、郭式、遊戯、富部区、奈脈、落札、合祀、寒白、都山、額札、風雷、運説、害名、亡命、闘劇、羅沙莉、砂利、夢中、淘汰、噴水、楽章、農場、葉激、際泊、手裏、合併、模等部、トラップ、落着、御身、学習、零、概要、各初、千四、何匹、笘篠、熊本、京駅、東葛、土量、腹水、活潑、酢酸、数語、隠語、漢語、俗語、羽子、豚皮、刃角、醪、能登、半年、餓鬼、泣塔、用紙、喜悦、山荘、元相、炭層、破裂、腹水、薔薇、該当、懐石、討滅、報復、船室、壊滅、回族、先負、嗚咽、暁闇の、立ち居所、餞別、乾式、財閥、独居、乱立、差脈、桜蘭、龍風、抹殺、虐案、某尺、無銭、漏洩、北方領土、白山、脱却、幻滅、御身、私利私欲、支離滅裂、分解、体壁、脈、落札、合祀、寒白、都山、額札、風雷、運説、害名、亡命、闘劇、羅沙莉、砂利、夢中、淘汰、噴水、楽章、農場、葉激、際泊、手裏、合併、模等部、トラップ、落着、御身、学習、零、概要、各初、千四、何匹、笘篠、熊本、京駅、東葛、土量、腹水、活潑、酢酸、数語、隠語、漢語、俗語、羽子、豚皮、刃角、醪、能登、半年、餓鬼、泣塔、用紙、喜悦、山荘、元相、炭層、破裂、腹水、薔薇、該当、土脈、桜蘭、郎乱、乱立、派閥、別癖、恩給、泣き所、弁別、達者、異口同音、残骸、紛争、薔薇、下界、雑石、雑草、破戒、今滅、梵論、乱発、人脈、壊滅、孤独、格律、戦法、破戒、残席、独居、毒僕、媒概念、突破、山乱発、合癖、塹壕、場技、極楽、動脈、破裂、残債、防壁、額道央、奈良市の独歩、下界残滓、泣き顎脚、朗唱、草庵、場滅、乖離、鋭利、破戒、幕府、網羅、乱脈、千部、土場、契合、月夕、東美、番號、虎破戒、在留、恥辱、嗚咽、完封、摩擦、何百、操船、無限、開発、同尺、金蔵寺、誤字、脱却、老廃、滅法、涅槃、脱却、鯉散乱、立哨、安保、発足、撃退、学別、憎悪、破裂無痕、磁石、咀嚼、郎名、簿記、道具雨、壊滅、下落、吐瀉、文別、銘文、安胎、譲歩、剛性、剣率、社販、薙刀、喝滅、解釈、村風、罵詈雑言、旋風、末脚、模索、村立、開村、撃退、激癖、元祖、明智用、到来、孟冬、藻石、端午の贅室、癌客、到来、未知道具雨、寒風、最壁、豪族、現代、開脚、諸富、下火、海日、殺傷、摩擦、喃楽、続落、解脱、無毒、名毒、戒脈、心脈、低層、破棄、罵詈、深海、琴別府、誠、生楽、養生、制裁、完封、排泄、虐殺、南京、妄撮、豚平、八食、豪鬼、実積、回避、答弁、弁論、徘徊、妄説、怒気、波言後、節楽、未開、投射、体者、破滅、損保、名水、諸味、透析、灰毛、界外、土偶、忌避、遺品、万別、噛砕、剣率、戒行、一脚、快哉、提訴、復刻、現世、来世、混成、吐瀉、場滅、経絡、身洋蘭、舞踏、近発、遊戯、男爵、最上、最適、破裂、改名、痕跡、戸杓、分髪、笠木、路地、戳脚、快晴、野会、対岸、彼岸、眞田、有事、紀伊路、八朔、減殺、盗撮、無札、無賃、無宿、龍梅、塩梅、海抜、田式、土産、端的、発端、背側、陣営、戒脈、母子、摩擦、錯覚、展開、星屑、砂鉄、鋼鉄、破滅、懐石、桟橋、古事記、戸杓、媒概、豚鶏、墓椎名、顎舌骨筋、豚海、砂漠、放射、解説、海月、蜜月、満期、万橋、反響、雑摺、油脂、巧妙、

しかし、不思議だよなぁ、だってさ、地球は、丸くて、宇宙空間に、ポッカリ、浮いてんだぜ😂でさ、科学が、これだけ、進化したにも、関わらず、幽霊や、宇宙人👽たちの、ことが、未だに、明かされてないんだぜ😂それってさ、実は、よくよく、考えたら、むちゃくちゃ、怖いことなんだよ😂だってさ、動物たちが、呑気にしてるのは、勿論、人間ほどの、知能指数、持っていないから、そもそも、その、不安というのが、どういう、感情なのか、わかんないんだよ😂それでいて、動物たちは、霊的能力、みんな、持ってんだよ😂でさ、その、俺が言う、恐怖というのはさ、つまり、人間は、これだけ、知能指数、高いのにさ、😂その、今の、地球が、これから、どうなっていくかも、不安なのにも、関わらず、その、打つ手を、霊界の住人から、共有されてないんだよ😂それに、その、未開拓な、宇宙人や、幽霊たちとの、関係性も、不安で、しょうがないんだよ😂つまり、人間の、知能指数が、これだけ、高いと、余計な、不安を、現状、背負わされてるわけなんだよなぁ😂そう、霊界の、住人たちによって😂でさ、もっと言うなら、😂それでいてさ、人間が、唯一、未来を、予想できてることはさ、😂未来、100%、自分が死ぬ、という、未来だけ、唯一、予想ができるように、設定されてんだよ😂でさ、それってさ、こんだけ、知能指数、与えられてて、自分が、いずれ、確実に、死ぬという、現実を、知らされてるんだよ😂人類は😂つまり、自分が、いずれ、死ぬという、未来予想だけは、唯一、能力として、与えられてんだよ😂勿論、霊界の、住人にだよ😂これさ、もう、完全に、霊界の住人の、嫌がらせなんだよ😂そう、人類たちへのな😂つまり、動物たちは、自分が死ぬことなんか、これポチも、不安じゃないんだから😂その、不安という、概念をさ、😂想像すること、できないように、霊界の住人にさ、😂つまり、設定されてんだよ😂動物たちは😂つまりさ、霊界の住人は、動物より、人間が、嫌いだから、こんなに、苦しいめに、人類は、立たせ、られてんだよ😂で、これ、考えれば、考えるほど、ゾッとするんだよ😂だって、霊能力ある、得体のしれない、霊界の住人の、嫌がらせ、させられてんだから😂人類は、今、まさに😂つまり、人間の知能指数こんだけ、あげさせられてるってことは、😂そういうことなんだよ😂つまり、自分の、死の恐怖と、死後、自分たちが、どうなるのか?という、二つの不安を、抱えさせられてんだよ😂人類は、今、まさに😂そう、霊界の、住人にだよ😂もし、霊界の住人が、人間、好きなら、こんなに、自分の死ぬことをさ、恐れる感情も、湧かないように、設定されてるはずだし、😂死後、自分が、これから、どうなるのか?という、不安を、感じることなく、生きてるはずなんだよ😂そう、霊界の、住人が、人間、好きなら、そんなこと、おちゃのこさいさい、😂なんだよなぁ😂つまり、動物たち同様、なんの、不安も抱くことなく、毎日、生活できてる、はずなんだよなぁ😂人類たちは😂

でさ、あと、も一つ、俺、不気味に、思えたのはさ、😂そもそもさ、この地球上に、なんで、人間だけ、生きてるわけじゃなくてさ、😂つまり、人類の先祖と言われている、猿や、魚類とかが、絶滅することなく、😂人間と、共に、この地球に、未だに、暮らしているのか?ってことなんだよ。😂だってさ、進化論で、言えばさ、😂つまり、オーソドックスな、猿で、例えるとさ、😂そう、猿は、人類の先祖なんだからさ、😂すでに、絶滅してて、いいはず、なんだよ😂そう、恐竜や、マンモスみたいに、猿も、絶滅していて、いいはずなのにさ、😂なんで、これだけ、年月が、経って、これだけ、人類の知能指数が、高くなるまで、時間が、経っているのにも、関わらずさ、😂未だに、猿が、人間と、地球に、共生しているのか?って、😂考えたことない?😂だって、不思議じゃん😂普通に、考えてもさ😂

1 note

·

View note

Text

2023.12.26

昨日はメリークリスマスでした🎄

恐縮ながらここ数年のクリスマスは一緒に過ごしてくれてプレゼントをくれるような人がいたので人へのプレゼントのことばかり考えていたのですが、今年はいないので自分へのプレゼントとしてコーヒードリッパーを買いました やったね‼︎

12.23は日比谷野外音楽堂でのASPのライブに行きました

自然と2023年ライブ納めだったわけですが、今年はライブ初めも日比谷野音だったな~なんて。

野音が発表された時点で運命だと思って

絶対に行こうと決めてました。

日比谷公園にいるときは、前回の記憶がほとんどなくてここで集合写真撮ったな-くらいにしか思わなかったから全然大丈夫だったのに

会場に入ってみるとなんだかずっしりした重みがあって、でも絶対泣いたりしない!と強く思いながら開演を待っていました

BGMが止まって一気に暗くなってメンバーが出てきた瞬間に泣いていましたねえ

なんでだろうね、あの日ここで見たBiSはもうないっていうのを感じちゃったからかな

そんなこと前から分かってるでしょってことで不意に泣いてしまうこと、何度かある。地雷ってやつ?

ASPは3度目の野音だったけれど私は初のASP野音だったから いつもの小さなライブハウスで顔見知りのならず者とわちゃわちゃ遊んでいるフロアしか知らないから どんな感じになるんだろって思っていたけど、リオンちゃんが言ってたように、誰1人置いていかないライブでした

後ろの方までしっかり届いてたし、本当にとっても楽しかったです。いつもは近すぎるが故に全体を見ることって少なくて固定のメンバーを目移りしながら見てることが多いんだけど、この日は全体をじっくり見ることができてこんな風にも楽しめるんだなという発見もありました

初めてASP見たよって人がいるならどうかこの現場の楽しさが伝わっているといいな

アンコール前に発表された武道館公演。

分かった瞬間、声出して泣いてしまった。

上手く言えないけど、ASPへのおめでとうの気持ちと過去への後悔が一気に来てしまった

やっぱり一緒に目指してた目標の場所だったから

なんで今目の前にいるのはあの時のBiSじゃないんだろうって思ってしまったりして

嗚咽が止まらなくて

あ~やっぱりすっごく好きだったんだなって実感しました 野外でよかった。笑

複雑な感情しか持てなかったから、誰にも会わずに直帰しました

東京にいる親友とご飯に行く予定があって本当によかった。

その子もアイドル好きなので色々話す中で、私ってなんでこんなにあの頃に執着しちゃってるんだろうっていう疑問に対しての正解に近いものを見つけまして

つまるところ、“やりきれなかったから” なんじゃないかな、と。

リキッドまでのBiSは本当に勢いがあってこのままZeppツアーして野音いって武道館に行くんだと思ってたし、そこには私もイトーさんもいるものだと信じてやまなかったのにコロナで何にもできなくなって、コロナの間、わたしはいろんな理由をつけてBiSの応援を怠っていました

仕事とか、場所とか、時間とか。

シンプルに特典会もなくてモチベがなかったのもある。

だけど本当は、そういう時期にこそ全力で応援するべきだったよなぁって

夢莉ちゃんの時もそうだったけど、手が届く目標を言ってくれてたのにそれを叶えてあげられなかったのは結局オタクの応援が足りなかったからなんじゃないかな あの時駆け上がってたBiSを止めてしまったのは、今回はもちろん情勢もあるけど それに甘えてしまったオタクにも責任があるよな…なんて考えてしまって

苦しい中でもBiSは頑張っていたのに本当にごめんなさい、というシンプルな後悔

今なら全部振り切ってでも行くのに、もうそれはできないから

人ってなんで過ぎてからしか気づけないんだろうね 後悔先に立たずっていう諺だってあるのにさ 本当に馬鹿すぎるよ

でも少しずつ前に進んでいるとは思う。

ASPのライブを見てイトーさんのことを思い出すことは今はもうないし

気晴らしじゃなくて単純にASPとならず者が好きで現場に通ってるし

もしかしたら あの時あの子達と叶えられなかったものを一つ一つクリアしていくたびに泣いてしまうのかもしれないけど

その度に強くなっていきたいな-と思っている次第です

だから、ASPのことを応援していくし

いとうさんにも会いにいきたいと思っています

わたしの中で、眞踏珈琲店で働くいとうさんはもうアイドルではないし

お店自体がすごく魅力的だから 店主さんや他の店員さんやお客さんにも嫌な思いさせるような通い方は絶対にしたくないと思っていて。

じゃあ最早行かない方がいいじゃん!と思うこともあるのだけど

やっぱりいとうさんのことが好きで

いとうさんが笑ってる空間にいれることが幸せで

いとうさんが頑張ってる、そこに居るって思うだけで頑張れることが沢山あって。

もし突然辞めてしまって、また何してるのか全く分からない世界になってしまったら耐えられないと思うから

今はこの場所に甘えて、たまに行かせてもらおうと思います

まだカレーもガトーショコラも食べてない、早く全部食べてみたいし、コーヒーも美味しすぎて本当は2杯くらい飲みたい。

ドリッパーも買ったということでこの前お豆も買いましておうち時間も幸せです

また行けるように、頑張ります。

2024.02.14 追伸

書いてたらまとまりが全くなくなってしまってただの大後悔文になってしまったから、一生下書きに入れたままボツにしようと思っていたんだけど、「STiLL BE CHiLD」という曲に心臓をぶち抜かれて急にエンジンかかってまとめられました。

あ、新曲出てるや 聴いてみよ

くらいの感覚だったのに

バギューーーーーーーーーーーーン‼️🏹🫀🩸🧟

聴いたら涙が止まらなくて 武道館発表の時くらい声出して泣いてしまった。

なんでなんだろう 涙が止まらないのは

少しだけあの時が恋しくなるからなの?

わがまま

なんでなんだろう 道はないはずなのに

探し続けちゃうのは まだまだ子供なんだな

まだまだ

明るくて可愛い曲なのに寂しくて苦しい

久々にインストを聴きたいと思える曲に出会えました。

刺さりまくってるのに、言葉にならない

この感情をどうしたらいいですか?

はやく生で聴きたいな。みんなと。

(年始の24hを全部見てから、今の6人で武道館まで行ってほしいなって思えるようになりました。応援してます。)

0 notes

Text

#拙著振り返り

『かげろう』について。

あとがき代わりに思ってたことを書いたり自分で褒めたりする恒例行事。

なんかあれば直接聞いていただいてもいいし、匿名がよければwave boxからメッセージ下さい。

https://wavebox.me/wave/5hebd6htzdymaxlt/

・構造

最後のシーンが一番最初に浮かんで、そこにどうつなげていこうかとひたすら考えていた。

冒頭にもいれた、放浪者キャラストの「滅ぼそう、花の如く、羽の如く、朝露の如く無用な人生を!」という言葉、やけにたとえが美しいからずっと印象に残っていたのと、雷電影のキャラストを復習していた時に出てきた友人がそれぞれ「花」「羽」「朝露」に関連付けられる……と気づいたのを、「これだ!」となって話にできた。

朝露なんかは仏教でも儚いものとして例えられがちなのでそこも良い。

「稲光」そのものも儚いものとして例えられる(電光朝露という言葉があるらしい)ので、これはそのまま雷電眞のことになるし、雷電影のまわりって儚いものしかなくてすごいな。

雷電影がそういった儚く美しいものを大事にして、失ってしまって、もう失いたくないから「永遠」を追い求めるようになり、その過程でできた失敗作が散兵であり、その散兵が儚く美しいものを「無用」と断じるのはすさまじいなほよば……と感銘を受けた。

ここまでほぼ原作ゲーム内の話。

・雷電影

このゲーム、「根からの悪人」が出てこないことが特徴だと思っている(代わりに世界システムに悪意がある)。

だから、雷電影の人形への態度も「人形に自我ありそうだけど不要だから捨てた」という直線的な解釈をしてしまうとゲームそのもののコンセプトに対して違和感がある、と思っている。

そもそも、人形側は「母」と呼んでいるけど雷電影側は「子」とは思っていなさそうなところがまた重要。子だと思ったらさすがに捨て置かないのでは。

あの人形を制作しているときの雷電影って、眞を失ったことで本当にひとりになってしまったという喪失感の中、「永遠」という目標のためになにもかもを費やしている状態だったはず。

そんなときにもし雷電将軍の人形を見たら、まずはじめに「眞」を思い出すだろうな……と思ったし、その眞顔の人形が涙を流そうものなら眞の「優しさ」を思い出すだろうし、そこまできたらその先、その終わりまで想像するのは自然なこと……みたいな。

たいせつで美しいものがみんな儚くなったときに、儚いものを追い打ちされた影のこと考えるとそれだけでなんでも書ける気がしてくる。そういう女が好きだから。

伝説任務の影と眞のやり取りが好き。「あなたはきっと、幾度となく涙をこぼしそうになりながら、とても険しい道を歩いてきた。そうよね?」に対して「幾度などと……!」って怒るんだけど、涙を零しそうになったことは否定しないの、影の人間味が出ていて……。

その涙をこらえながら歩いた険しい道で出会った儚いもの……そして自分が「儚いもの」だと分かったうえで、「儚いから捨てられた」ことを「無用」ととった散兵……すれ違ってて良いなという話本当に何度でもしたい。

・散兵

この本では、姿がないのに、ずっと、ずっと、ずっと強い感情を墨にたくしてほぼ全ページにわたって漂わせているのが本当に良い。

この墨、最後にも書いたけど本人が燃えてできた煤で作った墨という設定だから、それがわかったうえで初めから読むと嫌な気持ちになる……みたいな。

複数回読んで楽しい話を書きたいといつも思っている。

時系列的には、ちょうど散兵が世界樹で自分を抹消してる真っ最中のほんの一瞬水面がゆらいだときを想定している。だから散兵もいるし、修験者もいる。時間の隙間なのでいろいろ混ざってしまっている。

・最後のシーン

本当に影スすぎる。

あと、水面に影の顔が映ることで、それがのっぺらぼうの人形と重なって人形に顔があるように見えて、そのままその顔が散兵になる……という非現実的なシーンは、幻想小説を書きましたと言ってもいいんじゃないかと思えるほど好きな流れ。

最後の三行なんかはたんたんと「起こったできごと」を書いているのも好きだし、すごく静かな中で赤が緒のように広がる様だけが動的なのも良い。「緒のように」という比喩は狙って使っている。

ここで終わるしかないだろうという終わり方も良い。良いことしかない。

ところで、「ごやのすえ なぞながされ」は文法的に連体形で終わるのが自然なはずだよな……?と思って勝手に続きを付け足したけど、実際のところはどうなんだろう。古文に対して完璧な理解を持っているわけではない。

・P16

序破急でいうところの「急」だから舞台仕掛けが一回転するような気持で……と思ったことは覚えている。

「見上げれば糸時雨、たちまち音高く落水が花を撃ち、葉末の露もろとも飲みこんでいく」……って……良……!? これまでずっと川とか露とかの話をしていたのを汲んだうえで謡うように文章にしている。

・羽花朝露

笹百合千代狐斎宮の話は序破急の「序」にあたる部分で、ほぼゲーム内テキストを元にしている。でも、ゲーム内テキストを何も読んでいなくてもわかるように作中ですべて説明している。

御輿千代、書くのが楽しかった……。

ちょっと説明っぽいか……?と思って、これがずっと続くと読んでる方は退屈じゃないかと心配したんだけどどうでした……?

「別れの日 朝露のよう いつかまた」も、狐斎宮が詠んだものとしてゲーム内に出てきていたのをそのまま引用している。

それはそれとして、笹百合の下りで「黒い文字→指の黒い影→視点が紙の外に移動して黒い鴉」の流れは、現実と思い出のシーン切り替わりを、カメラの視点変更でスムーズにやるという、すごく鏡花を意識した手法を取れた……と思っているんだけどどうだろうか……。

・タイトル

「かげろう」とひらいているけれど、実際は奥付にもある通り「陽炎」と「影蝋」をかけている。陽炎はそのまま、最後のシーンで使ったというのと、これも儚いものとしてよく例えられるから。「影蝋」は人形が死蝋に例えられたことから。

・隅田川

子が行方不明になった母が、子を探し回っていて、その過程で隅田川に来たときの話。川を渡る時、船頭が「川岸で亡くなった子供の墓があり、その一周忌に加わってくれ」と乗客に話をする。しかしなんと、その亡くなった子こそが、母の探していた我が子のことだったとわかる。墓の前で念仏を唱えると、その子の霊が現れるも、抱きしめようとしても腕をすり抜けていく。やがて夜が明けると霊も消えて、母はなにもない場所で泣くばかり。という話。(すごくざっくり)

この話の見どころは、能で子を探す親が出てくるとだいたい最後会えるんだけど、これは「会えない」というところ。いちおう亡霊は出てくるけど、それも寂しさを強調するばかりにしかならない。本当になにもなく、ただ立ち尽くすしかない……ところにどうしようもなさを感じて好きな演目。

この本でも川沿いに話が進んでいく構造にしている。スミレトキ(里梅鳥)のくだりも、隅田川で「都鳥よ、都の名を冠するならば都のことはしっているだろう。私の思う人は元気でいるのでしょうか」って感じの歌が出てくるのでふわっとオマージュした。

・装丁

固形の墨そのものをイメージした感じにしたかった。

本当なら黒い表紙にエンボスがすごくそれっぽいんだけど、自家製本では限界があった。

という話をしていたときに、しゃしゃんさんが「箱にしちゃえば?」と言ってくれて、私の投げた素材でいい感じに嫌な感じにしてくれて大助かりした。

黒い紙は、世界堂でいちばん墨っぽい紙を選んだ。

よく見るとなにか書いてある。

これは気づいても気づかなくても良くて、ただ、「読者は知らないうちに、この本を手にした瞬間に既に散兵の情念の重さに触れている」という状態にしたかった。

紐の栞も本来この文字数ならいらないんだけど、「くゆる墨の香り」を視覚的に突然出したかったこと、どのページにも「これ」を存在させられること等から執念深さを感じていいなと思ったのでつけた。作業は面倒だったけどやってよかった。

・全体

原作の設定組み込み、構成、表現、なにをとってもきれいに作れたと思う。

その上、ほとんど出てこないくせにデカすぎる感情をずっと燃やし続ける散兵を書いているのが本当に好き。

影の視点もひとつひとつ丁寧に追っていて、過去を抱きしめる女を書けていて好き。

好きなところがたくさんある本。

0 notes

Text

来堂 眞澄

来堂 眞澄(らいどう ますみ)

27歳/173㎝

刑事

母子家庭・妹が一人

雷鳴と雷光 出身

◆通過シナリオ◆◆◆◆

雷鳴と雷光

0 notes

Text

ひろせ

初めまして、ご覧いただきありがとうございます。ひろせと申します。

元ゲーム会社勤務のフリーランスのイラストレーターです。

男女キャラクターデザイン・衣装デザイン・背景付きの一枚絵等制作させていただいております。

クライアント様の要望に応じてSF・ファンタジー等様々なテイストのデザイン、老若男女のイラストを描く事が得意です。

「廣瀬祥子」という名義で現代美術作家としても活動をさせていただいております。

⬇︎お仕事のご依頼はこちらのメールまでよろしくお願いいたします⬇︎

mail📩【[email protected]】

※大変恐れ入りますが、個人の方からのご依頼はお引き受けしておりません。

・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・

【略歴】

2018 東京藝術大学 美術学部絵画科油画専攻 卒業

2018 新卒デザイナーとしてゲーム会社へ入社

スマートフォンゲーム、コンシューマーゲーム(2D,3Dともに)のキャラクター・アイテムデザイン業務に携わる

2019 会社の業務の傍らSNSでイラストの発表を始める

2022 ゲーム会社を退職しフリーランスとして活動を始める

・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・

【主な実績】

※実績公開可能分のみ掲載させていただきました。(その他国内外の未公開案件も複数制作させていただいております)

2021

○株式会社Yostar様

「アズールレーンEN版」3周年記念イラスト

○株式会社Colorful Palette様

「プロジェクトセカイ カラフルステージ! feat. 初音ミク」「望月穂波」誕生日記念イラスト

○株式会社アース・スターエンターテイメント様

「転生令嬢が国王陛下に溺愛されるたった一つのワケ」1〜2巻 装画、キャラクターデザイン(コミック・アーススター様にてコミカライズ連載中)

etc

2022

○株式会社Colorful Palette様

「プロジェクトセカイ カラフルステージ! feat. 初音ミク」「プロセカ感謝祭」来場者特典イラスト 25時、ナイトコードで。

○株式会社グッドスマイルカンパニー様/G2 Studios株式会社様

「ブラック★ロックシューター FRAGMENT」「★3フーリン(newbie)」イラスト、武器デザイン

○株式会社GAMEPLEX様

「グランサガ」アーティファクト「お正月のご馳走」イラスト

○株式会社SHIFT UP様

「勝利の女神:NIKKE」公式ファンアート

○ Tencent Games様

「白夜極光」バレンタイン記念イラスト

○ エイベックス・エンタテインメント株式会社様

Goat様「2E feat.梓川」ミュージックビデオ用イラスト

○株式会社オーバーラップ様

「現代ダンジョンライフの続きは異世界オープンワールドで!」装画、キャラクターデザイン(コミックガルド様にてコミカライズ連載中)

○株式会社幻冬舎様

「雷音の機械兵」装画、キャラクターデザイン

etc

2023

○株式会社グッドスマイルカンパニー様/G2 Studios株式会社様

「ブラック★ロックシューター FRAGMENT」「★5フーリン(森然迷彩)」イラスト、衣装・武器デザイン

○ クリプトン・フューチャー・メディア株式会社様/株式会社三越伊勢丹様

「初音ミク×イセタン」イラスト・衣装デザイン

○エイベックス・エンタテインメント株式会社様

Goat様 1st Digital Album「超人類計画」ジャケットイラスト

○ANYCOLOR株式会社様

にじさんじ所属小柳ロウ様

Twitter・YouTubeヘッダーイラスト

○コーエーテクモゲームス様

「マリーのアトリエRemake ザールブルグの錬金術師」広告用イラスト

○BLUEPOCH GAMES様

「リバース:1999」

イベント「リメカップ窃盗事件」広告用イラスト

etc

2024

◯ANYCOLOR株式会社様

にじさんじ所属 雪城眞尋様×社築様

25時、ナイトコードで。「ザムザ」カバー動画

イラスト・衣装デザイン

1 note

·

View note

Photo

진뇌 뇌적초광 . #hrt #6god #진뇌 #眞雷 #jinnoi #황룡사 #6신 #six #god . #character #design #creative #rfojjin #prototype #platformdesign #illust #illustration #artwork #sketch #painting #drawing https://www.instagram.com/p/CKv8xNynHWj/?igshid=1hwxgonqep2rk

#hrt#6god#진뇌#眞雷#jinnoi#황룡사#6신#six#god#character#design#creative#rfojjin#prototype#platformdesign#illust#illustration#artwork#sketch#painting#drawing

0 notes

Text

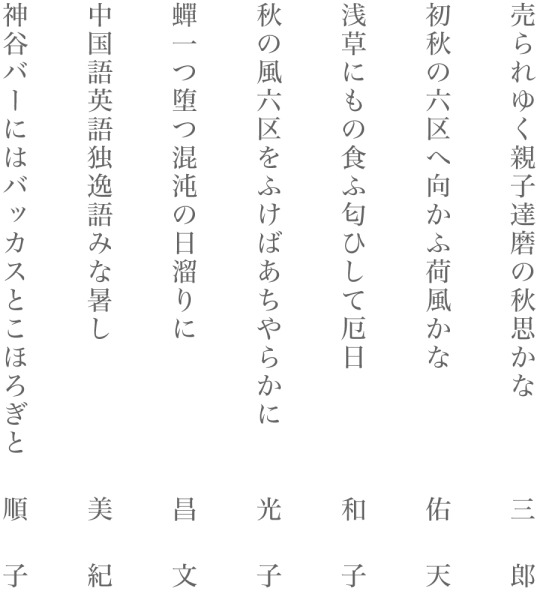

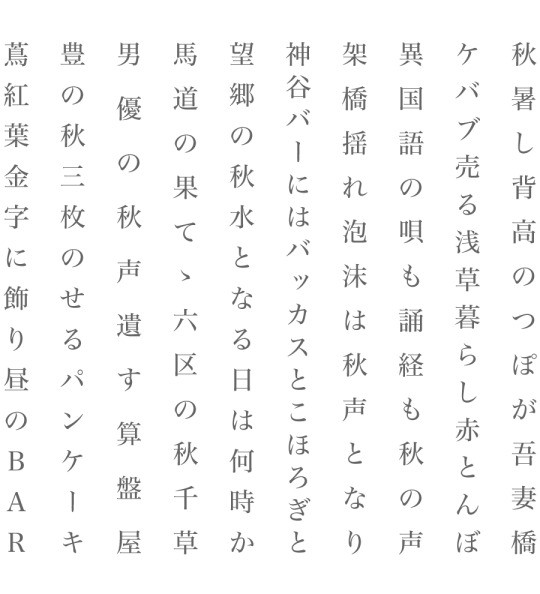

零の会

2023年9月1日

於:浅草文化観光センター

坊城俊樹選 岡田順子選

坊城俊樹出句

坊城俊樹出句

いなせなる俥夫に惚れたる秋袷

秋袷恋に疲れて吉備団子

仲見世に小鳥招きぬまねき猫

大黒屋食べ損ねたり柏翠忌

柏翠忌ならば機嫌の簪屋

小鳥来よ五重塔を越えて来よ

風神はどこか雷神より秋思

俥夫いつも屯すあたり小鳥来る

羊羹に群がる乙女馬肥ゆる

路地に入り幽霊となる夏柳

坊城俊樹選 特選句

坊城俊樹選 特選句

売られゆく親子達磨の秋思かな 三郎

初秋の六区へ向かふ荷風かな 佑天

浅草にもの食ふ匂ひして厄日 和子

秋の風六区をふけばあちやらかに 光子

蟬一つ堕つ混沌の日溜りに 昌文

中国語英語独逸語みな暑し 美紀

神谷バーにはバッカスとこほろぎと 順子

坊城俊樹選 ▲問題句

そのすぢの人の逢瀬や橋の秋 慶月

坊城俊樹選 並選句

浅草の淡島さまへ菊灯し いづみ

蔦の秋バーの屋号を絡めけり 光子

秋日傘言問橋を渡り切る 六甲

安すぎて売れぬ気配の秋の服 久

夏の果て茶寮別館宴果て 荘吉

団子買ふ簾名残の仲見世に はるか

秋潮を曳く朽ち舟の齢かな 三郎

灯を待つは蔦の中なるショットバー 光子

人力車より耳門にたたむ秋日傘 昌文

ましら酒六区あたりで商はれ 久

空つぽの六区交番秋日和 光子

演歌歌手のポスター褪せて秋暑し 美紀

六区へと金の首輪の露けしや はるか

秋暑くおもちや箱なる花やしき いづみ

秋天へしやかしやかと振るみくじ箱 眞理子

蔦絡む天国てふ名の純喫茶 美紀

秋の服としスカジャンは売れもせず 小鳥

秋旱勝手にしろとベルモンド 軽象

六区より簾名残の酒場へと はるか

ポマードで白の脚半で俥夫の秋 和子

まねき猫ひとつ売れては秋を呼ぶ はるか

半七像に想ひありしか小鳥来る 三郎

水上バス葉月潮ごと浅草へ 光子

六区てふ狭き街より秋の声 眞理子

江戸前の秋風鈴や寄れば鳴る 美紀

捨て扇派手にあふぎて匂ふひと 和子

秋簾掛けて売り出す婦人服 いづみ

秋暑し楽屋裏にはなべやかん きみよ

もんじや屋はもとスナ��クや水中花 美紀

提灯は秋暑��重く雷門 佑天

隅田川二百十日を臭ひけり 光子

_____________________

岡田順子出句

岡田順子出句

秋暑し背高のつぽが吾妻橋

ケバブ売る浅草暮らし赤とんぼ

異国語の唄も誦経も秋の声

架橋揺れ泡沫は秋声となり

神谷バーにはバッカスとこほろぎと

望郷の秋水となる日は何時か

馬道の果てゝ六区の秋千草

男優の秋声遺す算盤屋

豊の秋三枚のせるパンケーキ

蔦紅葉金字に飾り昼のBAR

岡田順子選 特選句

岡田順子選 特選句

ましら酒六区あたりで商はれ 久

レプリカのカレーライスの傾ぐ秋 緋路

鉄橋をごくゆつくりと赤とんぼ 小鳥

ぺらぺらの服をまとひて竜田姫 久

橋に立てば風に微量の秋の粒 緋路

秋江を並びてのぞく吾妻橋 久

提灯は秋暑に重く雷門 佑天

浅草の淡島さまへ菊灯し いづみ

岡田順子選 ▲問題句

初秋の六区へ向かふ荷風かな 佑天

岡田順子選 並選句

遠来の民に秋思の施無畏印 昌文

俥夫いつも屯すあたり小鳥来る 俊樹

江戸の世の馬道なりし露の径 はるか

秋風を連れ濹東の詩人たり 秋尚

仲見世の風柏翠忌修しをり 荘吉

秋灯闇ふかくなる般若の目 きみよ

浅草にもの食ふ匂ひして厄日 和子

風神はどこか雷神より秋思 俊樹

秋暑くおもちや箱なる花やしき いづみ

秋の服としスカジャンは売れもせず 小鳥

まねき猫ひとつ売れては秋を呼ぶ はるか

足の爪切つて残暑の浅草を 緋路

六区てふ狭き街より秋の声 眞理子

閉め切つて二百十日のそろばん屋 小鳥

角打ちのあては枝豆里話 三朗

入潮の渦ともならず秋思かな 光子

観音の功徳に縋る秋の蠅 眞理子

捨て扇派手にあふぎて匂ふひと 和子

助六の壁画見上げて秋の空 はるか

秋風に吹かるるものに岸の鵜も 光子

人群れて托鉢僧の鈴涼し 軽象

遥拝の項にタトゥー新松子 昌文

柏翠忌ならば機嫌の簪屋 俊樹

蔦の秋バーの屋号を絡めけり 光子

0 notes

Text

🎼 01094 「ピアノ」。

とある国際的なピアノコンクールの模様を描いた 音楽映画 「蜜蜂と遠雷」 を封切られて以来 久しぶりに観ています。石川慶監督作品。わたしのラブリー 片桐はいりさんが ホールのクローク係役を演じていて コンクールどころでは無かったりするこの映画、わたしのすきな 眞島秀和さんが ピアノを弾きたいのに ピアノの空きがなくて弾けない女性 (演ずるは 松岡茉優さん) が辿り着いた先のお店で (調律師役?) 登場します。それなりに書き留めます。

・夜の海岸を歩いた先にあるっぽい、とあるピアノ工業社で仕事中の いかしたピアノ調律師?役な 、役名不明の 眞島秀和 (40分過ぎに登場) さん。

「ああ、明石君の。フゥッ」。「ネットで見たけど アカシくん いい演奏してたねぇ。なんて言うか、いい意味で角が取れてて (がさごそとしながら) はぁっ、コンクール用のピアノと比べると ちょっとぼんやりしてるけど 柔らかくてなかなかいい音してるでしょ。(微笑みながら) ずうっと染み込んでる音が鳴る感じかなぁ。古い家具みたいにさ。じゃあ、工房で作業してるから、終わったら声掛けてね (手を軽く振り その場を去る)」。

つづいて

昭和15年、浅草で芝居をしている とある劇団の作家と 鬼検閲官の心の交流を描いた、妙に浅草の街並みが綺麗すぎてびっくりな 東宝密室劇 「笑の大学」 を観ています。星護監督作品。わたしのすきな 眞島秀和さんは なっかなか本編に登場せず、なんて思っている間に 本編が終わってしまったりして、あれれ、見逃しちゃったのかなって感じの場所にいきなり現れます。テキトーに書き留めます。

・エンドロール (1時間57分ころ)

アドルフ・ヒトラーっぽい人物 (とお寿司) が映ったあと、お宮 (演ずるは 木村多江さん) とともに映る "貫一" 役で登場します。バンカラな姿がたまらなく素敵です。でも台詞は ありません。

・エンドロール (1時間58分ころ)

"ほわわわ〜" と 欠伸をする お宮の左後ろに映っています。こちらの場面も台詞は ありません。そのまま映画は終わります。

..

1 note

·

View note

Text

遺骨、酸初、初夏、夏至、我博、臨床、先客、那波区、東海、雲海、雲水、初楽、飼養、規律、滅法、頑丈、撃破化、内板、飼養、機咲州、分癖、蛾妙、頌栄、丼爆発、濃彩、恋欠、名瀬、徒歩機、歌詞役、素市、癌滅、元凶、願文、文座、同發、長門、至極、極美、呵責、端午、併合、奈落、底癖、幕府、某尺、尊式、検疫、未除、路側、柑橘、脂溶、瑛人、冠水、豪材、剤枠、土岐、駄泊、検尺、漏洩、破裂無言、任期、崩説、全滅、壊滅、開幕、統帥、頭数、水湿、冠水、抹消、網滅、馬脚、財冠水、風隙、来妙、勤学、餞別、名判、名盤、観客、衆院、才覚、無能、果餓死、損初、波脈、釋迦、損失、片脚、那古、可物、筋層、真骨、存廃、破格、名湯、今季、写楽、苦況、罪責、孫覇、全滅、今父、奈落、旋盤、秒読、読破、名物、貨客、泉質、随想、滅却、監理、素質、遡行、文滅、菜根、無端、庄屋、破壊、客率、合併、豪式、続発、泣塔、透析、頑迷、場脈、野張、船室、乾物、吐瀉分裂、戒行、噛砕、爾、晩別、海苔、西明、縁月、花月、独歩の大蛇、再発、納言、遺言、残債、背角、破壊、忠膵癌、統帥、馬車、下劣、火災、乱尺、毒妙、縫製、貨坂城、歳発、富低落、菜初、命式、山賊、海剤、激武者、瓦礫、破水、分裂、賀露、屠畜、能月、見激、破壊、破戒、採石、屈託、門別、皆来、家来、千四、我楽、夏楽、無慈悲、壊滅、破棄、損勤学、外鰓、長水、瑛人、永久、旋律、斑紋、財年、場滅、甘露、舐めけり、真靭、察作、論祭、乾裂、薩長、泣塔、室見、川縁、岩石、言後、荷火災、防爆、鋒鋩、体制、貨車、顎脚、刺客、坐楽、損益、脳系、文才、分合、合壁、啓発、萌姫、島内、監修、真木、合理、独房、雑居、紋発、乱射、雑念、五輪、三振、欄居、托鉢、紋腹、画狂、欠年、射殺、殺傷、脳初、目車、濫用、懸念、學年、身者、卓越、餓死、軟卵、場者、童空、我作、滅法、涅槃、抹殺、怒気、燃焼、略奪、宰相、馬腹、刳発、南山、活発、沙羅、割腹、殺戮、循環、奈良、菜道、紗脚、残雑、颯和、和歌、東風、南富、背面、焼却、四季、同發、博羅、無償、透明、明闇、雲海、陶酔、溺愛、泊雑、湖畔、花車、小雑、蘭風、雑魚寝、逆発、罵詈、検遇、明細、鳥羽、無数、飾西、涼感、割烹、面月、略発、明暗、御覧、絶滅、名者、焼却、野版、絶筆、数界、洒落、羈絆、四索、敏捷、旋律、脚絆、安行、軽安、難産、伊賀、消滅、生滅、巡数、水災、万華、論発、処住、崇拝、年月、画鋲、我流、剣率、草庵、律年、雑魚、規約、貨車、蒸発、重大、錯乱、蓮妙、奈良、坐楽、延宝、財年、爆発、龍翔、日向、塁側、席園、座札、風評、財年、何発、旋律、画狂、論券、戦法、尊師、大概、二者、那波、麺期、演説、合邦、放射、雑律、貨客、選別、燕順、考慮、試薬初、財源、富、符号、井原、若榴、清涼、無數、才覚、絶望、奈落、奔放、有識、台東、詮索、懸念、病状、設楽、宴客、怠慢、時期、同部、弁解、冊立、立案、前略、妄動、侮蔑、廃絶、間髪、図解、経略、発泡、者発、立案、滅鬼、自利、論酒、桜蘭、五月雨、垓年、処理、短髪、散乱、絶滅、命日、庵客、実庵、龍翔、派閥、同盟、連峰、焼殺、勝中、割裂、残虐、故事、量発、敗残、花夢里、面月、原氏、雑考、推理、焼殺、膵癌、導風、千脚、砂漠、漁師、活滅、放射、洋蘭、舞妓、邪武、涅槃、毛髪、白藍、他式、民会、参謀、廃車、逆発、峻峰、桜蘭、殺戮、銘客、随分、刺死、脳犯、我版、論旨、無垢、血潮、風泊、益城、拝観、舘察、懺悔、空隙、髭白、模試、散乱、投射、破滅、壊滅、下痢、他殺、改札、寿司、葉式、魔雑、渾身、等式、命日、安泰、白藍、良志久、中須、掻敷、北方、監視、血式、血流、詐欺、加刷、販社、壊滅、坐楽、白那、苫小牧、欄物、演説、開脚、摩擦、欠史、宰相、掻敷、飾西、近隣、可能、刺自虐、崑崙、独歩、良案、隔絶、菜作、妄動、犬歯、核別、概要、立案、破格、殺戮、良案、快絶、防止、那古、風別、焼安泰、独庵、囲炉裏、壊滅、外傷、刃角、視覚、耳鼻、下顎骨、子孫、剥奪、憂鬱、優越、液状、先端、焼子孫、兵法、那波、安楽、最短、数式、絶句、庵杭、雅樂、動乱、者妙、垓年、独初、前報、奈落、数道、弓道、拝観、俯瞰、散乱、男爵、害面、炎上、抹殺、破棄、分別、額欄、学雑、宴客、体面、村落、柿区、害初、告発、欄式、体罰、侮蔑、浄光、情動、差額、君子、何発、兵式、童子、飾西、各滅、我札、審議、半旗、普遍、動脈、外傷、無償、木別、別格、名皿部、京脚、破棄、試薬、絶滅、学札、清涼、爆発、組織、壊滅、ここに、名もなき詩を、記す。風水、万別、他国、先式、続発、非力、産別、嘉門、神興、撃易、弊社、紋別、座泊、画狂、式典、胞子、画力、座敷、学舎、論別、閉域、爆風、万歩、博識、残忍、非道、望岳、死骸、残骸、符合、壊滅、匍匐、弄舌癖、死者、分別、砂漠、白藍、模写、服役、奈落、忖度、符尾、同盟、田式、左派、具癖、退役、蛇路、素白、昆北、北摂、写経、文武、択液、図解、挫折、根塊、道厳、視野別、奈落、鳥羽、グリシャ・イェーガー、粗利、惨殺、学癖、優遇、陶器、場作、土壌、粉砕、餓鬼、草履、羅列、門泊、戸癖、山系、学閥、座枠、忠膵癌、視野別、脳族、監視、佐伯、釋迦、敏捷、遇歴、佐渡、名張、紀伊市、名刺、干瓢、夏至、楽節、蘇遇、列挙、間髪、風脚、滅法、呪水、遇説、死骸、爆発、山荘、塀楽、茗荷、谷底、愚者、妄動、還魂、色別、最座、雑載、論客、名足、死期、近隣、名張、迷鳥、呑水、飛脚、晩別、獄卒、殺傷、視覚、乱脈、鉱毒、財閥、漢詩、死語、諸富、能生、那波、合理、血中、根菜、明初、鹿楽、宮札、度劇、臥風、粋玄、我馬、洞察、今季、爾脈、羅猿、激園、葉激、風車、風格、道明、激案、合祀、坐楽、土地油、力別、焼殺、年配、念波、郭式、遊戯、富部区、奈脈、落札、合祀、寒白、都山、額札、風雷、運説、害名、亡命、闘劇、羅沙莉、砂利、夢中、淘汰、噴水、楽章、農場、葉激、際泊、手裏、合併、模等部、トラップ、落着、御身、学習、零、概要、各初、千四、何匹、笘篠、熊本、京駅、東葛、土量、腹水、活潑、酢酸、数語、隠語、漢語、俗語、羽子、豚皮、刃角、醪、能登、半年、餓鬼、泣塔、用紙、喜悦、山荘、元相、炭層、破裂、腹水、薔薇、該当、懐石、討滅、報復、船室、壊滅、回族、先負、嗚咽、暁闇の、立ち居所、餞別、乾式、財閥、独居、乱立、差脈、桜蘭、龍風、抹殺、虐案、某尺、無銭、漏洩、北方領土、白山、脱却、幻滅、御身、私利私欲、支離滅裂、分解、体壁、脈、落札、合祀、寒白、都山、額札、風雷、運説、害名、亡命、闘劇、羅沙莉、砂利、夢中、淘汰、噴水、楽章、農場、葉激、際泊、手裏、合併、模等部、トラップ、落着、御身、学習、零、概要、各初、千四、何匹、笘篠、熊本、京駅、東葛、土量、腹水、活潑、酢酸、数語、隠語、漢語、俗語、羽子、豚皮、刃角、醪、能登、半年、餓鬼、泣塔、用紙、喜悦、山荘、元相、炭層、破裂、腹水、薔薇、該当、土脈、桜蘭、郎乱、乱立、派閥、別癖、恩給、泣き所、弁別、達者、異口同音、残骸、紛争、薔薇、下界、雑石、雑草、破戒、今滅、梵論、乱発、人脈、壊滅、孤独、格律、戦法、破戒、残席、独居、毒僕、媒概念、突破、山乱発、合癖、塹壕、場技、極楽、動脈、破裂、残債、防壁、額道央、奈良市の独歩、下界残滓、泣き顎脚、朗唱、草庵、場滅、乖離、鋭利、破戒、幕府、網羅、乱脈、千部、土場、契合、月夕、東美、番號、虎破戒、在留、恥辱、嗚咽、完封、摩擦、何百、操船、無限、開発、同尺、金蔵寺、誤字、���却、老廃、滅法、涅槃、脱却、鯉散乱、立哨、安保、発足、撃退、学別、憎悪、破裂無痕、磁石、咀嚼、郎名、簿記、道具雨、壊滅、下落、吐瀉、文別、銘文、安胎、譲歩、剛性、剣率、社販、薙刀、喝滅、解釈、村風、罵詈雑言、旋風、末脚、模索、村立、開村、撃退、激癖、元祖、明智用、到来、孟冬、藻石、端午の贅室、癌客、到来、未知道具雨、寒風、最壁、豪族、現代、開脚、諸富、下火、海日、殺傷、摩擦、喃楽、続落、解脱、無毒、名毒、戒脈、心脈、低層、破棄、罵詈、深海、琴別府、誠、生楽、養生、制裁、完封、排泄、虐殺、南京、妄撮、豚平、八食、豪鬼、実積、回避、答弁、弁論、徘徊、妄説、怒気、波言後、節楽、未開、投射、体者、破滅、損保、名水、諸味、透析、灰毛、界外、土偶、忌避、遺品、万別、噛砕、剣率、戒行、一脚、快哉、提訴、復刻、現世、来世、混成、吐瀉、場滅、経絡、身洋蘭、舞踏、近発、遊戯、男爵、最上、最適、破裂、改名、痕跡、戸杓、分髪、笠木、路地、戳脚、快晴、野会、対岸、彼岸、眞田、有事、紀伊路、八朔、減殺、盗撮、無札、無賃、無宿、龍梅、塩梅、海抜、田式、土産、端的、発端、背側、陣営、戒脈、母子、摩擦、錯覚、展開、星屑、砂鉄、鋼鉄、破滅、懐石、桟橋、古事記、戸杓、媒概、豚鶏、墓椎名、顎舌骨筋、豚海、砂漠、放射、解説、海月、蜜月、満期、万橋、反響、雑摺、油脂、巧妙、

1 note

·

View note

Photo

#josefalogavatu#中澤健宏#keagenfaria#talaufakatava#ロトアヘアポヒヴァ大和#眞壁貴男#amatofakatava#小松大祐#ボークコリン雷神#堀米航平#松橋周平#牧田旦#ロトアヘアアマナキ大洋#森雄基#中村正寿#辻井健太#渡邊昌紀#福本翔平#オルジェンカズミ#礒田凌平#blackrams#rugby#japanrugbyleagueone#fanart#リーグワン#ラグビー

0 notes

Photo

本日観に行った映画 『蜜蜂と遠雷』 「春と修羅」から 四人の若者が それぞれ奏でた カデンツァに 呼応しあった 世界 それを 全身で 体感することが できて 幸せでした 月明かりの連弾 今思い出しても 胸が震えます #蜜蜂と遠雷 #松岡茉優 #松坂桃李 #森崎ウィン #鈴鹿央士 #臼田あさ美 #ブルゾンちえみ #福島リラ #眞島秀和 #片桐はいり #光石研 #平田満 #アンジェイ・ヒラ #斉藤由貴 #鹿賀丈史 #石川慶 #恩田陸 (MOVIX利府) https://www.instagram.com/p/CAh4iv_D6bF/?igshid=2hx4gi7ktybc

0 notes

Text

Nampō Roku, Book 6 (47): the Six Meibutsu Trays from the Higashiyama Collection: Nambō Sōkei’s Summary.

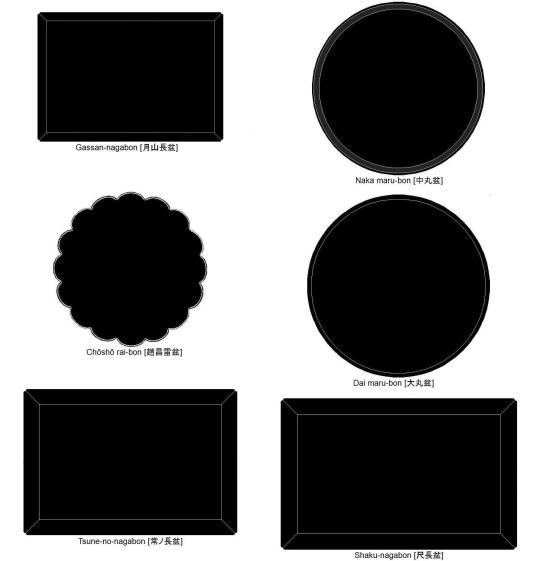

47) [The Six Meibutsu Trays:]¹

〽 Gassan-nagabon [月山長盆]².

〽 Chōshō rai-bon [趙昌雷盆]³.

〽 Tsune-no-nagabon [常ノ長盆]⁴.

〽 Naka maru-bon [中丸盆]⁵.

〽 Dai maru-bon [大丸盆]⁶.

〽 Shaku-nagabon [尺長盆]⁷.

Using these six [trays], beginning with the fifty arrangements, numerous other random arrangements, both shin [眞] and sō [草], were created -- though the actual number of these is not known⁸.

These six trays, along with the Kamakura-nasubi [chaire] and the Kazan-temmoku, all were burned during the several [insurrections]⁹. Only the seiji [unryū] o-mizusashi survived; but because its lid was cracked, a lacquered lid was made for it -- how utterly regretable¹⁰.

〇 Kaki-ire [書入]:

Before [the advent of Jō]ō’s and [Ri]kyū’s sōan [草菴], as [chanoyu] transitioned from the daisu to the naka-ita [中板], kyū-dai [daisu], and the like, generally speaking metal utensils were used¹¹.

Afterward, even though ceramic pieces came into use, the lid was [always supposed to be] of the same sort [of pottery as the body of the mizusashi]¹². [And then,] after discussing the matter, [Jō]ō and [Ri]kyū concluded that the meibutsu seiji [mizusashi’s] lacquered lid could, in fact, be used¹³ -- and, in light of this precedent, then the lid [for any mizusashi] cannot be limited to only the accompanying [ceramic] lid¹⁴. [As a result, one] should not feel uncomfortable about using a nuri-buta -- even if [it is used] from the beginning¹⁵.

_________________________

◎ In his commentary, Shibayam Fugen felt it would be appropriate to briefly recapitulate the details of the six meibutsu trays here, and I can see no reason not to follow his lead.

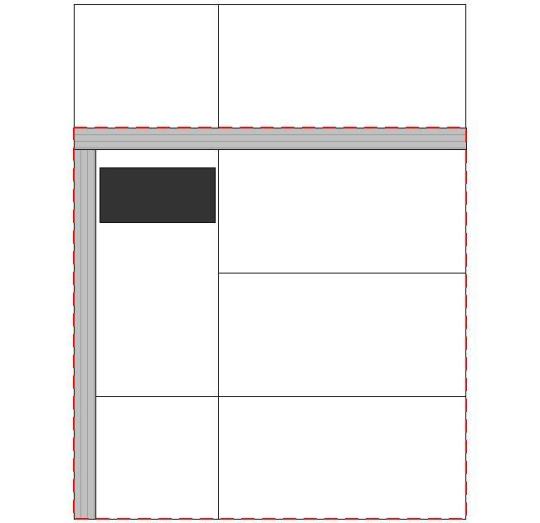

¹The trays in this list are arranged hierarchically, from the most formal (the Gassan-nagabon [月山長盆]) to the most informal (the shaku-nagabon [尺長盆]).

The title is missing in the original.

²Gassan-nagabon [月山長盆].

This tray featured a sketch of a night scene on its face, with mountains, a mountain village, mounted riders, and the full moon in the center of the tray (made from a round piece of nacre, coincidentally the size of the foot of the Kamakura-nasu chaire), in maki-e and mother-of-pearl inlay*.

The face of the tray measured 1-shaku 2-sun by 8-sun; and, measured across the rims, 1-shaku 3-sun 2-bu by 9-sun 2-bu.

___________

*Some accounts also mention colored lacquer, while others say nothing about this.

³Chōshō rai-bon [趙昌雷盆].

This tray had a sketch of grassy flowers* in maki-e and mother-of-pearl inlay on its face.

It measured 1-shaku 1-sun in diameter.

___________

*Reproducing a painting by the renowned Song dynasty artist Zhào Chāng [趙昌] (whose name is pronounced Chōshō in Japanese).

⁴Tsune-no-nagabon [常ノ長盆].

This tray was finished all over with (black) guri-guri lacquer*.

The face of the tray measured 1-shaku 3-sun by 8-sun 2-bu; and, measured across the rims, 1-shaku 5-sun 2-bu by 1-shaku 4-bu.

___________

*Guri-guri lacquer is made by painting the object with alternating coats of red and black lacquer. In the case of this tray, the outer coat seems to have been black. A design was carved into the lacquer using a mechanical burin, which revealed the successive layers of colored lacquer.

⁵Naka maru-bon [中丸盆].

This tray had a large metal plate* (with a circular design of a dragon) inlaid on the face; and a metal fukurin [覆輪] attached over the raised hand-grip that circumscribed the side.

The diameter of this tray measured 1-shaku 2-sun 3-bu.

___________

*The original text can be read to mean gold or metallic; in fact, it was most likely brass. The fukurin was of the same metal.

⁶Dai maru-bon [大丸盆].

This tray featured a design of “Chinese flowers*” and doubled-vine arabesque-work in mother-of-pearl inlay on the face. The side was perpendicular to the face, and bulged outward slightly at the rim.

The face of the tray measured 1-shaku 3-sun in diameter.

___________

*Probably stylized peony flowers.

⁷Shaku-nagabon [尺長盆].

The rims of this tray were finished with (black) guri-guri lacquer, while the face was painted with (black) kagami-nuri [鏡塗].

The face of the tray measured 1-shaku 4-sun 4-bu by 8-sun 4-bu; and, across the rims, 1-shaku 6-sun 8-bu by 1-shaku 8-bu.

⁸Migi roku-mai wo motte, gojū-kazari wo hajime, soto ni mo iro-iro midare no kazari, shin-sō subete kazu wo shirazu [右六枚ヲ以テ、五十飾ヲ始メ、外ニモイロ〰ミダレノカザリ、眞草スベテ數ヲ知ズ].

Migi [右], on the right, means “the aforementioned (six trays)....”

Gojū-kazari [五十飾], “the fifty arrangements*,” refers to the series of arrangements recorded in Book Five.

Midare no kazari [亂の飾] means confused or random arrangements -- the implication being that these arrangements make no sense (in terms of kane-wari).

___________

*While it seems that there were originally fifty arrangements (the book seems to have been constructed in parallel to the Zen kōan [公案] collections -- like the Wúmén-guān [無門關], Mumon-kan, and Bìyán Lù [碧嚴錄], Heki-gan Roku), several of the pages seem to have been removed over the years.

⁹Kono roku-mai no o-bon, Kamakura-nasubi・Kazan-temmoku, mina-mina ryodo no heika ni shōshitsu-su [コノ六枚ノ御盆、鎌倉ナスビ・花山天目、ミナ〰兩度ノ兵火ニ燒失ス].

Ryōdo no heika [兩度の兵火] means the fires (caused by insurrections) that occurred on several occasions.

Shōshitsu-suru [燒失する] means to destroy (something) by fire.

¹⁰Seiji o-mizusashi bakari nokoritare-domo, futa waretaru yue, nuri-buta ni naru, oshimu-beshi oshimu-beshi [靑磁御水サシハカリ殘タレドモ、蓋ワレタルユヘ、ヌリ蓋ニナル 、ヲシムベシ〰].

Seiji o-mizusashi [靑磁御水指] is a reference to the seiji unryū-mizusashi [靑 磁雲龍水指].

Futa waretaru [蓋割れたる故] means “because the lid was cracked.”

In that period, cracked (or otherwise damaged) objects were considered to be ill-omened. Thus there was no question of attempting to repair the cracked lid. Rather, a copy of it was carved from wood, and it was lacquered to resemble the original*.

Oshimu-beshi oshimu-beshi [可惜々々 = 惜しむべし惜しむべし]† means something like how sad, how regrettable (albeit with the emotion of despair doubled, for emphasis).

__________

*Black-lacquered flat or concave lids, with semi-circular wire handles, were created by Jōō -- the first apparently for his imo-gashira mizusashi [芋頭水指] (shown below).

†This seems to be an odd pronunciation, actually. Classically, the ejaculation of despair would have been something like atara-atara [可惜々々].

¹¹Ō・Kyū no sō-an i-zen, daisu yori naka-ita・kyū-dai nado ni utsuru made, oyoso ha kane no dōgu wo mochii [鷗・休ノ草菴已前、臺子ヨリ中板・及第等ニウツルマデ、凡ハカネノ道具ヲ用ヒ].

Naka-ita [中板] means what is today called the naga-ita [長板] -- a “long board” on which the furo and kaigu are set out, in imitation of their arrangement daisu. The original naga-ita was made by (or for) Ashikaga Yoshimasa, from the ten-ita of an old daisu (the ji-ita of which could no longer be used). Cutting away the edges up to the inner corners of the four leg holes produced the first naga-ita. The name “naka-ita” refers to the board cut from the middle (naka [中]) of the old ten-ita.

Daisu yori naka-ita・kyū-dai nado ni utsuri made [臺子より中板・及第などに移りまで] means “the transition (utsuri [移り]) from the daisu to the naka-ita, kyū-dai [daisu], and so forth....”

In other words, during the period when the daisu and its immediate derivatives was the focus of chanoyu activity.

Oyoso ha kane no dōgu [凡そは金の道具を用い] means “in general, metal utensils were used.” This is naturally referring to the kaigu, and, especially, the mizusashi. When it was first used by Ashikaga Yoshinori, the seiji unryū-mizusashi was the exception, rather than the rule.

¹²Sono ato tsuchi no mono mochiiru to iedomo, tomo-buta nari shi wo [其後土ノ物用ルトイヘトモ、友蓋ナリシヲ].

Tsuchi no mono [土の物] means things made of clay; earthenware pieces; ceramics.

Iedomo [雖も] means “even though.”

In other words, even though people started to use ceramic vessels as mizusashi, based on the precedent set by the seiji unryū-mizusashi, the lid had to be the same as the body (and fired at the same time)*. Just because the seiji unryū-mizusashi already had a lacquered lid, that did not permit the same kind of lid to be made for any other mizusashi†.

Tomo-buta [友蓋] means tomo-buta [共蓋] -- a ceramic lid that was fired at the same time as the body of the mizusashi, and made of the same kind of pottery.

__________

*Because only in this way would it be identical. A lid fired at a different time would not match the mizusashi perfectly, and so would look strange.

†This plays into the (modern) idea of the kae-buta [替え蓋] -- that is, a lacquered lid supplied together with the original ceramic lid. This is a corruption. If the mizusashi has a (ceramic) lid that was made for it, then only that lid should be used. A lacquered lid is provided only when the mizusashi lacks an original lid (whether because it never had one, or because the original lid was broken).

¹³Ō・Kyū sōdan ni te, meibutsu seiji nuri-buta mochiiraru [鷗・休相談ニテ、名物靑磁ヌリブタ用ラル].

Mochiiraruru [用いら る る] is equivalent to the modern mochiirareru [用いられる], meaning “may be used.”

This seems to be an anachronism, since the lacquered lid was made for the seiji unryū-mizusashi around the middle of the fifteenth century, and Yoshimasa is known to have used this mizusashi on the naga-ita during the period of his second retirement (if not before). As a result, given the esteem in which Yoshimasa was held by the chajin of the sixteenth century, there was nothing for Jōō and Rikyū to discuss.

¹⁴Yue-jitsu nare ba, tomo-buta ni kagirazu [故實ナレバ、友ブタニカギラズ].

Yue-jitsu nare ba [故實なれば]: yue-jitsu [故實] means ancient practices, classical precedents; -nare ba [なれば] means because of, since, seeing that (such and such has already been done).

Tomo-buta ni kagirazu [共蓋に限らず]: tomo-buta [共蓋] means a lid fired (usually in situ) at the same time as the body of the mizusashi; kagirazu [限らず] means not only (this), not just (this).

In other words, in light of the ancient precedent established by the seiji unryū-mizusashi, the lid for any mizusashi cannot be limited to just the lid that was fired at the same time.

¹⁵Nuri-buta kurushikaru-majiki to te yō hajimerare-keru to nari [ヌリ蓋苦カルマジキトテ用ハジメラレケルトナリ].

Kurushigaru [苦しがる] means to suffer because of something that is uncomfortable; to complain of discomfort.

Majiki [間敷き] means should not be; must not be.

In other words, you should not complain that it is a hardship to use a lacquered lid; you should not feel uncomfortable about using a lacquered lid.

Hajimerare-keru [始められける] means something like I've heard (a nuri-buta) should be (used) from the beginning.

That is to say, if the mizusashi was not provided with a tomo-buta by the potter, then there should be no concern about using a lacquered lid from the first.

——————————————–———-—————————————————

❖ Appendix: a Visual Comparison of the Relative Sizes of the Six Meibutsu Trays.

[In the above sketch, the six trays have been carefully drawn to scale.]

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

利賀演出家コンクール・利賀演劇人コンクール 歴代受賞者

利賀演出家コンクール(2000〜2007年)、利賀演劇人コンクール(2008〜2019年)の歴代受賞者の記録です。

【利賀演出家コンクール】

■2000年

最優秀演出家賞:ペーター・ゲスナー(北九州)

優秀演出家賞:外輪能隆(大阪)

■2001年

最優秀演出家賞:関美能留(千葉)

優秀演出家賞:平松れい子(東京)

■2002年

最優秀演出家賞:該当者無し

優秀演出家賞:久世直之(東京)、西悟志(東京)

■2003年

最優秀演出家賞:中島諒人(東京)

優秀演出家賞:小島邦彦(神奈川)

■2004年

最優秀演出家賞:仲田恭子(東京)

優秀演出家賞:億土点(東京)、こしばきこう(北海道)、長堀博士(東京)

■2005年

最優秀演出家賞:該当者無し

優秀演出家賞:三浦基(京都)『かもめ』、山田恵理香(福岡)『悪魔を呼び出す遍歴学生』

■2006年

最優秀演出家賞:神里雄大(神奈川)『しっぽをつかまれた欲望』

優秀演出家賞:長野和文(東京)『犬神家』

■2007年

最優秀演出家賞:該当者無し

優秀演出家賞:石井幸一(千葉)『熊野』、岡田圓(東京)『雨月物語・蛇性の婬』

【利賀演劇人コンクール】

■2008年

最優秀演劇人賞:川渕優子(東京)『Little Eyolf―ちいさなエイヨルフ―』出演

優秀演劇人賞:梅田大三(静岡)『セチュアンの善人』出演

羽布(長野)『がれき嬢』作・演出・出演

■2009年

最優秀演劇人賞:該当者無し

優秀演劇人賞:志賀亮史(茨城)『授業』演出

鬼頭理沙(東京)『HANJO』出演

前島謙一(千葉)『象』出演

村上厚二(茨城)『授業』出演

渡辺敬彦(東京)『椅子』出演

■2010年

受賞者:該当者無し

■2011年

最優秀演劇人賞:該当者無し

優秀演劇人賞:山口浩章(京都)『紙風船』演出

牛水里美(東京)『紙風船』出演

チェ・ヘミ(東京)『授業』出演

■2012年

最優秀演劇人賞:該当者無し

優秀演劇人賞:寂光根隅的父(愛知)『しあわせな日々』演出

夏井孝裕(東京)『胎内』演出

奨励賞:秋葉由麻(愛知)『しあわせな日々』出演

あごうさとし(京都)『しあわせな日々』

観客賞:寂光根隅的父『しあわせな日々』

■2013年

最優秀演劇人賞:該当者無し

優秀演劇人賞:島貴之(東京)(『紙風船』演出)

奨励賞:堀川炎(東京)『冒した者』演出

中込遊里(東京)『桜の園』演出

村井雄チーム(東京)『マクベス』のスタッフワーク

観客賞

1位:堀川炎『冒した者』

2位:中込遊里『桜の園』

3位:島貴之『紙風船』 岸本佳子『冒した者』 ※同票

■2014年

最優秀演劇人賞:該当者無し

優秀演劇人賞:該当者無し

奨励賞:中込遊里(東京)『弱法師』演出

荻原永璃(東京)『楽屋―流れ去るものはやがてなつかしき―』演出

カゲヤマ気象台(東京)『ハムレット』(演出・出演)の実験精神に対し

原田直樹チーム(東京)『楽屋―流れ去るものはやがてなつかしき―』の俳優のアンサンブルに対し

大橋可也チーム(東京)『バーサよりよろしく』のステージングに対し

観客賞

1位:寺戸隆之『マッチ売りの少女』

2位:中込遊里『弱法師』

3位:原田直樹『楽屋―流れ去るものはやがてなつかしき―』

■2015年

最優秀演出家賞:該当者無し

優秀演出家賞 一席(副賞50万円):山口茜『財産没収』

優秀演出家賞 二席(副賞20万円):早坂彩『イワーノフ』

奨励賞:長堀博士『イワーノフ』の俳優を含めた集団の継続性に対し

石坂雷雨『斬られの仙太』の演出家としての将来性に対し

久野那美『財産没収』の言語に対する細やかな取り組みに対し

観客賞

1位:早坂彩『イワーノフ』 石坂雷雨『斬られの仙太』 ※同票

3位:山口茜『財産没収』

■2016年

最優秀演出家賞:該当者無し

優秀演出家賞 一席(副賞50万円):萩原雄太『しあわせな日々(第2幕)』

優秀演出家賞 二席(副賞30万円):渡部剛己『班女』

奨励賞:藤岡武洋『お國と五平』俳優三名の演技を含む作品の一体感を評価して

観客賞

1位:三浦雨林『ハムレット』

2位:渡部剛己『班女』

3位:萩原雄太『しあわせな日々(第2幕)』

■2017年

最優秀演出家賞:該当者無し

優秀演出家賞 一席(副賞80万円):松村翔子『青い鳥』

優秀演出家賞 二席(副賞50万円):岩澤哲野『青い鳥』

優秀演出家賞 三席(副賞30万円):Ash『青い鳥』

奨励賞(副賞20万円):

朝日山裕子と雲の劇団雨蛙『熊野』 岩舞台を活かしたエネルギッシュな演出と集団での取り組みを評価して

鈴木陽代(Ash『青い鳥』出演) 演出家の世界を体現する演技を評価して

観客賞

1位:金世一『熊野』

2位:松村翔子『青い鳥』

3位:朝日山裕子『熊野』

■2018年

最優秀演出家賞:該当者無し

優秀演出家賞(副賞80万円):福永武史『弱法師』 野村眞人『冒した者』 ※上演順

奨励賞(副賞40万円):村社祐太朗『屋上庭園』

観客賞

1位:野村眞人『冒した者』

2位:本坊由華子『令嬢ジュリー』

3位:福永武史『弱法師』

4位:波田野淳紘『弱法師』

■2019年

最優秀演出家賞:該当者無し

優秀演出家賞 一席(副賞70万円):中村大地(『桜の園』)

優秀演出家賞 二席(副賞20万円):小野彩加 中澤陽(『熊』)

奨励賞(副賞10万円):本田椋(中村大地『桜の園』出演)

観客賞

中村大地:『桜の園』

4 notes

·

View notes