#1780s womenswear

Text

Oil Painting, 1787, French.

By Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun.

Portraying Marie Antoinette in a red velvet dress with black fur trim, with her children.

Château de Versailles.

#élisabeth vigée le brun#marie antoinette#marie Thérèse de France#Louis Charles de France#womenswear#1780s womenswear#1787#1780s#1780s painting#1780s France#red#louis Joseph of France#dress#1780s dress#royalty#ancien regime#château de versailles

76 notes

·

View notes

Text

Planche 1, Cabinet des Modes, May 15th 1786, Bibliothèque Nationale Française.

This plate has a LONG description, and here's a (shortened) rough translation of the description:

We can say it is no longer desirable for women to dress with great adornment (...) and these fashions are no longer made but for ceremonial gatherings, weddings, formal balls, large meals, which take place in very small numbers. This justifies us to not have often representations of these garments (...), nevertheless since they re sometimes worn, we show them in plates 1 and 2.

In plate 1 we can clearly see that we no longer wear the big paniers and even in the most adornment, the fashions have been simplified (except, of course, the court clothes, which do not vary much and can be traces to the clothes of our fathers) (...).

The woman in Plate 1 wears a blue robe à la Turque. The petticoat is of the same fabric and colour, the sleeves are made of white gros-de-Naples or another white fabric. The trim of the dress is in white crepe in the shape of rosettes, and in the middle of each is bouquet of artificial roses. The skirt of also decorated with white crepe and rosettes similar to the dress. The cuffs attached to the sleeves are made of cut white gauze. The throat is covered with a gauze fichu, tied at the front with a rainbow ribbon bow, she wears white leather gloves, and a fan. The head is covered with a bonnet also tied with a rainbow ribbon and topped with a garland of artificial roses. The ribbon forms a large bow at the back and holds a white crepe veil that falls almost to the waist, and on top of the bonnet rises a set of feathers: two rose, two blue, one white, and one green. The hairstyle has light curls along the entire front of the head, her hair is pulled up at the back in a flat bun, and two large curls on each side fall down her length. Her shoes are blue to match the colour of the dress, and are adorned with rainbow ribbon.

I found many funny things in this description, like that the magazine writers thought in 1786 that this look was simple, the concept of rainbow ribbon (ruban à l'Arc-en-Ciel) that seems to simply be a ribbon in colourful stripes, and the size and complexity of that bonnet. How about you? Please let me know in the comments or reblog tags, what is your favorite part of this outfit, or even if you'd like to reproduce it.

Also, the plate 2, that is a men's outfit, will be posted soon :)

#18th century#18th century fashion#cabinet des modes#1780s#1786#france#womenswear#blue#blue womenswear#fashion plate

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

thinking once again about how i want a good 18th century comedy OR a gay romance. or both.

#:V#im fond of 1780s menswear but i wouldnt turn down a good 30s setting#or anything really. i just want a good 18th century movie.#everyones obsessed with regency and like yeah it looks good but 1790s menswear is literally so fun!!#(and im sure the womenswear was fun too! i just dont really know what womens fashion looks like no matter the year)

8 notes

·

View notes

Note

Have you read Spin the Dawn by Elizabeth Lim? Idk what Era precisely it's meant to be, but I'm curious if anyone in the Chinese fashion sphere has anything to say about the clothes making/designing portions of the book, re: what clothes making was really like, the job of a royal tailor/tailors in general (were they common, or did most people make their own clothes? Was it a respected job?), that kind of thing! Thank you for your work on this blog!

I don't usually read fantasy novels like Spin the Dawn but I can say a thing or two about clothing production in imperial China. The state of dressmaking was different for each era and I can only talk a little bit about the Ming and Qing. Obviously I don't know the complete details of every stage of production for clothing, I'll just share some things that I do have knowledge on. Most of my information came from Rachel Silberstein's book A Fashionable Century: Textile Artistry and Commerce in the Late Qing, which could be read on JSTOR.

Royal dressmaking

Clothing that was meant for royal use was seldom created by one person alone, but rather the combined efforts of specialists and professionals in different areas. The designs would be made by artists in court, then textiles used for the clothing would be commissioned from state owned textile workshops, then sent to tailors to be sewn into garments and then to embroiderers if embroidery was required. Embroidery wasn't always necessary, since for most of the Ming fashionable and prestigious clothing was made from fabrics with woven patterns (e.g. brocades, damasks) instead of embroidered ones; embroidery would not become the dominant form of decoration until the Ming-Qing transition in the mid 17th century. Normal people wouldn't be able to purchase fabrics from the imperial workshops, but imperial workshops have been on the decline since the late Ming and commercial workshops were producing quality fabrics on a par with those from the imperial ones. Imperial workshop also frequently sublet their work to commercial ones.

As to the design aspect, formal court dress was heavily regulated as to what patterns and garments could be used for what occasion, so there wasn’t much room for artistic liberty. It was on informal clothing that more creativity could be exercised; embroiderers could choose what patterns and motifs go on garments and tailors could experiment with different proportions.

Source

Women’s 吉服 jifu formal ensemble from the Qianlong era. The patterns and their placement for such formal garments were fixed.

Source

Guangxu era informal 氅衣 changyi. The final appearance of this garment was still the combined efforts of many people, e.g. the weavers decided on the purple color, the tailor decided on the proportion and the embroiderers the floral motifs etc..

Home dressmaking

Common people prior to the 17th century mostly made their own clothes, particularly by the female members of the household. It was very common to make clothing from scratch i.e. the growing of cotton or grooming of silkworms, to fabric weaving, sewing and embroidering. It was considered a part of women's education to learn how to weave fabrics and sew garments together, but this doesn't mean that the entire dressmaking process was confined to women or one person either; men, who were expected to do farm work, would grow the crops necessary for the weaving of fabrics, and often assisted in the weaving process. Since the majority of the Chinese population lived in the countryside, many families produced fabrics from raw materials they made on their own farms and made clothes from said fabrics. Because of the difficulty in weaving brocaded fabrics by oneself, home dressmakers who couldn't afford to buy ready woven fabrics prior to the late Ming had to limit themselves to plain fabrics. In the late Ming and early Qing, the rise of embroidery as the dominant method of decoration meant that fashionable patterns became available to less wealthy people who couldn't afford to buy expensive brocaded fabrics, since they could reproduce all the fashionable patterns with just needle, thread and spare time. Embroidery books showing popular patterns and motifs were widely available and could be purchased cheaply. With that said, that doesn't mean that the entirety of a garment had to be made from scratch; many decorations and notions could be bought from shops, like trimmings, ribbons, buttons and prefabricated embroidery appliques. The seamstress would just need to buy the fabric, decorations and notions and put them together as one garment. In the Qing, women seldom went out of the house, and they relied on vendors or middlemen for vendors who brought products to their homes for sale. For women at the time, being a skilled weaver, seamstress or embroiderer was a highly desirable trait, not just because it symbolized "female virtue" whatever that means, but also because it provided work opportunities. Women who were otherwise not employed could take commissions from commercial weaving, tailoring or embroidery workshops as a side income.

Commercial dressmaking

Since the 17th century, the textile industry was increasingly commercialized and it since became more viable to purchase ready woven fabrics from commercial workshops, especially for people in urban areas. These were usually owned by rural families as a side income, and they would often hire landless people to work in their manufactories. I don't know if owning a textile manufactory was a respected job (probably not, considering the literati's hatred for everything commercial) but these people did make serious money. Family operating businesses were often co-owned by wife and husband. Embroidery workshops making prefabricated embroidered appliques and tailor shops making ready to wear garments were also quite common, often relying on middlemen for delivering orders and negotiating prices between the workshop and individual embroiderers/seamstresses in the countryside. In Qing tailor shops, it was often the case that only menswear could be purchased ready to wear, whereas womenswear was made to measure or by the wearer herself. Within tailor shops, there were many subdivisions of labor, like some people did pattern drafting, some people cut pattern pieces and some people assembled the garments. The status of commercial tailors has historically been low, mostly because of the Confucian ruling class’ disdain for consumption, luxury and anything non-self sustaining.

Source

Ca. 1780s export painting showing weaving women.

Feminist tangent

In the Qing, most home weaving and embroidering were done by women, but the commercial workshops were male dominated and their guilds prohibited entry for women, because commercial dressmaking had become a lucrative business and men didn’t want to share employment with women. Male employees in workshops were considered artisans and better paid, whereas women who had to work at home were considered unskilled labor and paid less. Most commercial tailors in the Qing were also male, for reasons similar to why embroidery was male dominated. Whereas women commonly sewed clothes for themselves and their families, they were often prohibited from becoming professional tailors working in workshops or joining a guild. It’s that bogus thing where handicrafts are “women’s work” but when men see how profitable they are they suddenly become “artistic” and limited to men.

Commercial tailors, who were male, were seen as a cultural abomination for doing what was historically seen as “women’s work” for profit. In order to elevate themselves to a higher, more respected status, they chose to throw women under the bus and revise the history of all things historically considered “women’s work” to make them more male centered. An example of this was the 露香园 Luxiang Yuan or Dew Fragrance Garden, a renowned Suzhou embroidery workshop built up by three generations of women of the Gu family, who owned the estate and was the namesake of their style of embroidery, 顾绣 guxiu or Gu embroidery. The male family head at the time, Gu Mingshi, later became the patron saint of the Suzhou embroiderer’s guild founded in 1867. The reason why Gu Mingshi was worshipped instead of the three women who made Gu embroidery famous was largely because male members of the Suzhou embroiderer’s guild needed historical justification for their exclusion of women and erasure of women’s contributions. Apparently late 19th century scholars also complained about this misogyny so this isn’t a new understanding.

Source

Gu embroidery by Han Ximeng, one of the three OG Gu women.

With all of this said, it doesn’t mean that women stopped working in commercial embroidery; women were actually the backbone of the industry, they just didn’t get any recognition from official, male written guild records and such. Many people in the 19th century observed that while the resident embroiderers in commercial workshops were men, a lot of their work was sublet to independent female embroiderers in the countryside, who were not credited on the finished product or advertising.

Now I’m kinda inspired to make a whole rant about working women in the Qing and their representation (or lack thereof) in the Republican era, but there are some 20 unanswered asks sitting in my ask box so maybe later😅

332 notes

·

View notes

Text

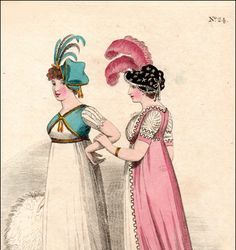

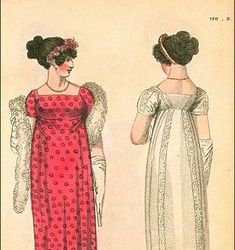

The 1800 Fashion History

The year 1800 heralded a new century and a new world. The fashion landscape had changed radically and rapidly; the way that women dressed in 1800 stood in stark contrast to the dress of a generation earlier. The wide panniers, conical stays, and figured silks of the eighteenth century had melted into a neoclassical dress that revealed the natural body, with a high waist and lightweight draping muslins (Fig. 1). The origin of this garment was the chemise dress of the 1780s, worn by influential women such as Marie Antoinette and Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire (Ashelford 174-175). The chemise dress, in part, reflected a neoclassicism that was beginning to emerge in fashion. Interest in classical antiquity had been growing throughout the second half of the eighteenth century, following the excavations of Pompeii and Herculaneum. Classical revivals appeared not only in fashion, but in architecture, the fine arts, and interior design (Davidson 30). However, it was the violently shifting politics at the end of the eighteenth century that spurred this style to the forefront. The French Revolution brought the old world hierarchy crashing down, forever altering dress during the 1790s. The new classical style, imitating the clothing of ancient democracies, seemed to be evidence of a political philosophy on the rise.

.By 1800, the high-waisted silhouette was the prevailing fashion across the Western world (le Bourhis 72). The most extreme manifestations of the Revolutionary classical dress, such as the dampening of gowns so that they clung to the body, were rarely seen after 1800; indeed, those radical fashions had seldom ever been seen outside of France (C.W. Cunnington 26). Still, neoclassicism continued to dominate fashionable dress (Fig. 2). Fashionable women consciously sought to reproduce the supposed fashions of Ancient Greece or Rome. Everything from the hairstyles to the draping shawls evoked antiquity; the preeminence of white as a dress color was due, in part, to the incorrect assumption drawn from classical statuary that classical women only wore white. The slim, vertical line of the garments themselves reflected the neoclassical preference for clean geometry expressed in other visual and applied arts. Fashion historian Philippe Séguy wrote that early 1800s dress “would have been at home in the days of Hadrian” (le Bourhis 73). However, neoclassicism was not the only influence on fashion during the 1800s. Notably, the campaigns of Napoleon Bonaparte brought inspiration from all over the world. For example, his occupation of Egypt popularized turbans for evening wear, and sketches of Egyptian ruins inspired palm motifs (Tortora 313; Foster 13). Towards the end of the decade, Spanish ornamentation, such as slashed sleeves, and a heavy use of fur imported from Russia, Poland, and Prussia was the result of Napoleon’s incursions in those countries (le Bourhis 108-109; C.W. Cunnington 27). Gothic ornament began to appear by 1810, and fanciful elements of pastoral dress were also seen.

In addition to the very high waistline, directly under the bust, the signature feature of womenswear was the prominent use of fine cotton muslin; it achieved a lightness and drape that could not be accomplished with wool or silk (Byrde 23; Foster 12). The main form of dress construction was the “stomacher” or “fall front” dress. This consisted of a bodice front attached to the skirt which was partially cut in a flap; once the wearer pulled on the sleeves and fastened the inner bodice lining, the skirt flap was pulled up where it was fastened with ties around the “waist” and the bodice front was pinned into place (Johnston 166; C.W. Cunnington 31-32). Figure 3 illustrates this construction method. This type of dress was known as a “round gown.” Around 1804, some dresses were made with button fastenings up the center back of the bodice; these were referred to as frocks (Davidson 26).

Dresses saw minor changes during the 1800s, losing much of the rounded volume of the previous decade. By 1810, skirts were much straighter, and the fullness that was left in the skirt was concentrated at the back, while the front was flat, falling straight to the floor (Fig. 4). In the early years, long trains were common on fashionable gowns, for both day and evening wear, but these began to gradually disappear around 1807 (Byrde 24; Foster 21, 29). The straighter, slimmer appearance of the 1800s was also echoed in the bodice back which featured seams that created a distinctive “kite” or “diamond” shape and gave a very slim, small-backed effect. Finally, straight, narrow sleeves too reinforced the clean lines (Davidson 26; Johnston 56). Importantly, part of the neoclassical ideal was the beauty of the natural, nude body. Fashion legends abound that tell of women leaving off their stays entirely, and appearing with very little underwear at all; while it seems that some women really did abandon their stays, the practice was not widespread or mainstream. Instead, nudity was suggested in the revealing cut of dresses. Large portions of the chest and back were bared even in day dresses, sleeves were short, and draping muslin revealed the shape of the leg (Fig. 5) (C.W. Cunnington 28; Davidson 63-64; Laver 155). Of course, this new style of dress did force a change in underwear. The narrowed skirt only required a single petticoat; indeed one was necessary for modesty beneath the nearly-transparent muslin (Byrde 25). Both long and short stays were worn; the new term “corset” referred to lightly boned or even simply corded supports, and these were often worn instead of stays. The chief goal of any supportive undergarment was to raise and shape the breasts, as their natural roundness was desirable for the first time (Davidson 64). Finally, throughout the decade, the fullness in the back of the gown was supported by a bustle pad attached to the inside of the skirt (Johnston 166; C.W. Cunnington 32-33).

The neckline of dresses, for both day and night, was quite low and could be either square or V-neck. During the day, the low neckline could be filled in with a chemisette or tucker (Foster 22). In the early years, the most fashionable sleeve was short for both day and night. Later in the decade, long sleeves were also worn, and they began to gain some fullness at the sleeve head (Davidson 288-289). In the evening, there was a fashion for short overdresses or tunics which borrowed from the ancient Greek chlamys (Fig. 6). While white was considered correct for evening, the nearly transparent muslins were sometimes worn over colored silk slips, creating shimmering pastels (Fig. 4) (Byrde 25-27; C.W. Cunnington 29-30).

Textiles of the 1800s were often enriched with embroidery, one of the few elements permitted to disrupt the classical line. Whitework, colored and gilt threads, and chenille were all employed to decorate gowns with a variety of embroidered designs (Figs. 2, 7) (Johnston 146, le Bourhis 95, 104). While white was undoubtedly the most modish color for dresses, it was difficult and costly to maintain. Sturdier printed cottons and patterned silks were common for daywear, and warmer wools were acceptable in the winter months (Figs. 3, 8) (Byrde 27).

A discussion of 1800s textiles would be incomplete without mention of the resurgence of French silk. In 1804, Napoleon declared the Empire, becoming Emperor, and he revived the luxury and pomp of the ancien régime, instituting lavish court dress once again. Napoleon gave the silk industry a much-needed boost in an imperial decree that French silk be worn at formal ceremonies (Fig. 9). The imperial commissions alone saved the French fashion industry which had been decimated during the Revolution (Fukai 125; le Bourhis 84-94, 100). While Paris was the center of women’s fashion, the best cottons originated in Britain and India; Napoleon forbade the wearing of foreign cotton in order to stimulate French manufacturing. His wife, Joséphine, was the most fashionable woman of the era, the undisputed leader of la mode, and she negotiated the contradictions of a fashion that preferred simple muslin with the demands of court dress expertly (Fig. 10) (Jensen).

Outerwear and accessories were essential elements of the period, often introducing pops of color (Ashelford 178). By far, the most important accessory of the neoclassical period was the shawl, specifically Indian kashmiris/cashmere (Figs. 2, 5). Lightweight muslin gowns did not provide much protection from the cold, and shawls became a necessary accessory; not only did they provide warmth, they added to the classical draped effect. Imported Indian shawls were wildly expensive luxuries, and a favorite of Empress Joséphine (Fig. 10) (Jensen). European weavers quickly began to create cheaper imitations, most notably in Paisley, Scotland, and that city’s name would become synonymous with the pine or buta/boteh motif (Laver 155; Johnston 40; le Bourhis 77, 81). Other forms of outerwear included the pelisse (Fig. 11) and the redingote, both types of coat, and the spencer, a cropped jacket (Ashelford 179; C.W. Cunnington 34-38). Other smaller accessories also mark the era, such as swansdown boas and large fur muffs. Notably, the reticule, a small drawstring handbag, became a standard element of a woman’s outfit (Fig. 12). Reticules became essential as the era’s narrowly-cut skirts prevented the wearing of pockets beneath the dress (Byrde 25-29).

Hairdressing further underscored the classical inspiration of the era; styles were frequently given names from antiquity such à l’Agrippine and à la Phèdre (le Bourhis 80). The most extreme style was à la Titus, in which the hair was cropped short and messily tousled. More frequently, a woman’s hair was arranged in ringlets and curls, often entwined with bandeaux, ribbons, and jeweled combs (Figs. 1, 5, 10) (Tortora 317; Foster 22, 26). There was an astonishing variety of millinery. Jockey caps, lavish evening turbans, wide-brimmed bonnets, face-shielding poke bonnets, and veiled caps were all modish choices (Figs. 4, 6, 13) (C.W. Cunnington 29, 52-53).

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Oil Painting, 1784, French.

By Jacques-Louis David.

Portraying Madame Charles-Pierre Pécoul.

Musée du Louvre.

#oil painting#painting#french#France#Jacques-Louis David#musée du louvre#Madame Charles-Pierre Pécoul#1780s#1784#1780s painting#1780s hair#1780s womenswear#third estate

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

Oil Painting, 1789, English.

By Thomas Lawrence.

Portraying Miss Harriet Maria Day in a white chemise dress.

Montreal Museum of Fine Arts.

#painting#1780s painting#oil painting#white#1789#1780s England#1780s dress#1780s hair#1780s britain#Montreal museum of fine arts#womenswear#1780s womenswear#robe en chemise#thomas Lawrence#Harriet Maria day

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Beige Floral Cotton Dress, 1780-1785, English.

Victoria and Albert Museum.

#V&A#floral#cotton#beige#extant garments#womenswear#dress#1780#1780s#1780s dress#1780s extant garment#1780s England#1780s Britain#British#English

268 notes

·

View notes

Text

Beige Floral Cotton Robe à l’Anglaise, ca. 1760-1770, Indian (for the European Market).

Victoria and Albert Museum.

#robe à l’anglaise#womenswear#extant garments#dress#Cotton#Indian#1780s India#floral#V&A#1760#1760s#1760s dress#1760s India#1760s extant garment

212 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pale Green Taffeta Dress, 1775-1785, French.

Musée des Arts Décoratifs Paris.

#womenswear#extant garments#dress#silk#green#18th century#1775#1770s#1780s#1770s dress#1780s dress#1770s france#1780s France#mad paris#musée des arts décoratifs paris#France#French#reign: louis xvi#1776#1777#1778#1779#1780#1781#1782#1783#1784#1785#1770s extant garment#1780s extant garment

260 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pink and Green Robe à la Polonaise, 1780-1785, French.

Musée des Arts Décoratifs Paris.

#musée des arts décoratifs paris#mad paris#womenswear#extant garments#dress#silk#18th century#robe à la polonaise#french#France#1780s#1780s dress#1780s France#reign: louis xvi#pink#green#1780#1781#1782#1783#1784#1785#1780s extant garment

183 notes

·

View notes

Text

White Printed Cotton Dress, 1780s, English.

Victoria and Albert Museum.

#white#cotton#dress#womenswear#extant garments#1780s#1780s England#English#British#1780s Britain#1780s dress#18th century#V&A

124 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pink Silk Stays, 1780-1789, British.

Victoria and Albert Museum.

#pink#silk#stays#womenswear#extant garments#1780#1780s#1780s britain#V&A#British#1780s stays#1780s undergarment#1780s extant garment#undergarments#corset

139 notes

·

View notes

Text

Beige Chintz Dress, ca. 1780, Dutch.

Victoria and Albert Museum.

#beige#Chintz#cotton#womenswear#extant garments#dress#1780#1780s#1780s Netherlands#1780s dress#1780s extant garment#V&A

93 notes

·

View notes

Text

White Silk Dress with Purple Trim, 1780-1785, British.

Victoria and Albert Museum.

#white#silk#dress#extant garments#womenswear#British#1780s#1780#1780s Britain#1780s dress#1780s extant garment#V&A

76 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yellow Silk Robe à la Polonaise, 1780-1785, American.

Met Museum.

#met museum#yellow#silk#dress#robe à la polonaise#18th century#1780#1780s#American#USA#womenswear#extant garments#1780s usa#fave#1781#1782#1783#1784#1785

178 notes

·

View notes