#A Study of Provincial Life

Text

Literal March Madness

Middlemarch, A Study of Provincial Life. Novel by George Eliot

Ides of March. Assassination of Julius Caesar

#knowing tumblr#I have a pretty good ide-a of which option will win here#xkcd#polls on tumblr#poll#polls#march madness#tournament#bracket#march#Middlemarch#A Study of Provincial Life#Ides of March#Julius Caesar#Brutus#Cassius#assassination#Shakespeare#assassination of julius caesar#0x7v0x8#poll tournment#March Madness Round 1

89 notes

·

View notes

Note

a few quick questions on Machete, what breed is he? I love the angles of his snout and the proportions remind me of a borzoi though I don't think he is one. Also, does he have a set age for when he's a cardinal? I picture him to be around mid-30s or so. Wonderful art! love your stuff and find you an inspiration :)

He's a fictional breed called Podenco Siciliano, which is closely related to modern day Ibizan Hound (pictured below) and other Mediterranean rabbit-hunting podencos. I usually just default to calling him a sighthound since he's somewhat of a provincial mongrel and not meant to be purebred anyway.

As for the age, mid-30s sounds about right. I think the current timeline goes something like this:

0 - Born to a lower-middle class family in Sicily, father is a tradesman, has three older brothers. Generally considered a runt, is weak and sick all the time, parents suspicious of his unusual colors.

3 - Gets left at a monastery and raised by monks as a foundling. Nervous and meek kid, but the monks think he's endearing and do their best to support him. Is taught to read and write, which is a massive advantage at that day and age, and learns rudimentary Latin through exposure.

9 - Apprenticed to a Neapolitan priest, moves to southern part of mainland Italy (or Kingdom of Naples as it was called, it was ruled by Spain actually). Does chores and runs errands in exchange for education and experience.

15 - The priest gets elevated to a bishop and decides to sponsor Machete's further studies at an acclaimed university in Venice (in Northern Italy). There he studies theology, medicine, arts, law, philosophy and gets fluent in Latin and adequate in Greek. Befriends Vasco but their relationship is short-lived.

21 - Ordained a priest. Leads a parish somewhere in Papal States (Central Italy). Is generally well liked but doubts his career choice from time to time.

26 - Becomes a part of the Papal Court in Vatican, mostly because of the recommendations of his former mentor and professors, good reputation, excellent track record and sheer luck. Still a priest but assists bishops, cardinals and the pope himself directly. Moves to Rome. Becomes pope's unofficial confidant due to his obedient and hardworking nature and because of his lack of prestigious family connections that would render him a threat. Slowly starts to gain wealth.

30 - Created a cardinal (which is the second highest position in the church after the pope, and it's at the sole discretion of the pope who becomes one). Is also a bishop as a technicality. Handles administrative jobs, tons of paperwork, at some point he's in charge of a lot of the political correspondence and diplomatic missions. Still the old pope's trusted advisor but disliked by the majority of the cardinals, who see him as an outsider, sycophant and a potential disruptor of the status quo.

34 - Meets Vasco again. Vasco has become a succesful politician in Florence, he's married with three children.

38 - The pope dies and Machete's status falters. He starts to work with the Roman inquisition more. Oversees trials, torture, excommunications and executions of heretics, witches and most of all, protestants (since we're reaching Counter Reformation times and the Vatican is Very Worried about the spread of Luther's ideas). Isn't having a good time at all but keeps up the appearances. Gets infamous. The beginning of the true villain era.

40 - Grows increasingly more disillusioned with life and his ideals, as well as the corruption of the Curia. Burned out, paranoid and desperate. Uses scare tactics, extortion and legal trickery to expose and undermine his enemies, but gains them faster than he can keep up. Employs spies, thugs and assassins. Feared and loathed.

43 - Gets assassinated and dies in disgrace.

#answered#jaydenchapstick#sorry this turned out sorta long#and kinda bummer too#all of this is subject to change if I end up thinking of something better#not set in stone just the current grand picture#the ages are approximate#the history of Italy and the workings of the catholic church are both such clusterfucks holy moly gosh darn#I've done research but don't rely on my word that this is all accurate and feasible in the end it's fantasy rules#whenever you see him wearing any red it's a sign he's at the cardinal phase these positions are color coded like that#Machete

877 notes

·

View notes

Text

What's Happening in China? The November 2022 Protests

Hello! I know that there's so much going on in the world right now, so not everyone may be aware of what is happening in China right now. I thought that I would try to write a brief explainer, because the current wave of protests is truly unprecedented in the past 30+ years, and there is a lot of fear over what may happen next. For context, I'm doing this as someone who has a PhD in Asian Studies specialising in contemporary Chinese politics, so I don't know everything but I have researched China for many years.

I'll post some decent links at the end along with some China specialists & journalists I follow on Twitter (yeah I know, but it's still the place for the stuff at the moment). Here are the bullet points for those who just want a brief update:

Xi Jinping's government is still enacting a strict Zero Covid policy enforced by state surveillance and strict lockdowns.

On 24 November a fire in an apartment in Urumqi, Xinjiang province, killed 10. Many blamed strict quarantine policies on preventing evacuation.

Protests followed and have since spread nationwide.

Protesters are taking steps not seen since Tiananmen in 1989, including public chants for Xi and the CCP to step down.

Everyone is currently unsure how the government will respond.

More in-depth discussion and links under the cut:

First a caveat: this is my own analysis/explanation as a Chinese politics specialist. I will include links to read further from other experts and journalists. Also, this will be quite long, so sorry about that!

China's (aka Xi Jinping's) Covid Policy:

The first and most important context: Xi has committed to a strict Zero Covid policy in China, and has refused to change course. Now, other countries have had similar approaches and they undoubtedly saved lives - I was fortunate to live in New Zealand until this year, and Prime Minister Ardern's Zero Covid approach in 2020-2021 helped protect many. The difference is in the style/scope of enforcement, the use of vaccines, and the variant at play. China has stepped up its control on public life over the past 10 years, and has used this to enforce strict quarantine measures without full regard to the impact on people's lives - stories of people not getting food were common. Quarantine has also become a feared situation, as China moves people to facilities often little better than prisons and allegedly without much protection from catching Covid within. A personal friend in Zhengzhou went through national, then provincial, then local quarantines when moving back from NZ, and she has since done her best to avoid going back for her own mental and physical health. Xi has also committed China to its two home-grown vaccines, Sinovac and Sinopharm, both of which have low/dubious efficacy and are considered ineffective against new variants. Finally, with delta and then omicron most of the Zero-Covid countries have modified their approach due to the inability to maintain zero cases. China remains the only country still enacting whole-city eradication lockdowns, and they have become more frequent to the point that several are happening at any given time. The result is a population that is incredibly frustrated and losing hope amidst endless lockdowns and perceived ineffectiveness to address the pandemic.

Other Issues at Play:

Beyond the Covid situation, China is also wrestling with the continued slowdown in its economic growth. While its economic rise and annual GDP growth was nigh meteoric from the 80s to the 00s, it has been slowing over the past ten years, and the government is attempting to manage the transition away from an export-oriented economy to a more fully developed one. However, things are still uncertain, and Covid has taken its toll as it has elsewhere the past couple of years. Youth unemployment in particular is reaching new highs at around 20%, and Xi largely ignored this in his speech at the Party Congress in October (where he entered an unprecedented third term). As a result of the perceived uselessness of China's harsh work culture and its failure to result in a better life, many young Chinese have been promoting 躺平 tǎng píng or "lying flat", aka doing the bare minimum just to get by (similar to the English "quiet quitting"). The combination of economic issues and a botched Covid approach is important, as these directly affect the lives of ordinary middle-class Chinese, and historical it has only been when this occurred that mass movements really took off. The most famous, Tiananmen in 1989, followed China's opening up economic reforms and the dismantling of many economic safety nets allowing for growing inequality. While movements in China often grow to include other topics, having a foundation in something negatively impacting the average Han Chinese person's livelihood is important.

The Spark - 24 Nov 2022 Urumqi Apartment Fire:

The current protests were sparked by a recent fire that broke out in a flat in Urumqi, capital of the Xinjiang province. (This is the same Xinjiang that is home to the Uighur people, against whom China has enacted a campaign of genocide and cultural destruction.) The fire occurred in the evening and resulted in 10 deaths, which many online blamed on the strict lockdown measures imposed by officials, who prevented people from leaving their homes. It even resulted in a rare public apology by city officials. However, with anger being so high nationwide, in addition to many smaller protests that have occurred over the past two years, this incident has ignited a nationwide movement.

The Protests and Their Significance:

The protests that have broken out over the past couple of days representing the largest and most significant challenge to the leadership since the 1989 Tiananmen movement. Similar to that movement, these protests have occurred at universities and cities across the country, with many students taking part openly. This scale is almost unseen in China, particularly for an anti-government protest. Other than Tiananmen in 1989, the most widespread movements that have occurred have been incidents such as the protest of the 1999 Belgrade bombings or the 2005 and then 2012 anti-Japanese protests, all of which were about anger toward a foreign country.

Beyond the scale the protests are hugely significant in their message as well. Protesters are publicly shouting the phrases "习近平下台 Xí Jìnpíng xiàtái!" and "共产党 下台 Gòngchǎndǎng xiàtái!", which mean "Xi Jinping, step down/resign!" and "CCP, step down/resign!" respectively. To shout a direct slogan for the government to resign is unheard of in China, particularly as Xi has tightened control of civil society. And people are doing this across the country in the thousands, openly and in front of police. This is a major challenge for a leader and party who have prioritised regime stability as a core interest for the majority of their history.

Looking Ahead:

Right now, as of 15:00 Australian Eastern time on Monday, 28 November 2022, the protests are only in their first couple of days and we are unsure as to how the government will respond. Police have already been seen beating protesters and journalists and dragging them away in vehicles. However, in many cases the protests have largely been monitored by police but still permitted to occur. There seems to be uncertainty as to how they want to respond just yet, and as such no unified approach.

Many potential outcomes exist, and I would warn everyone to be careful in overplaying what can be achieved. Most experts I have read are not really expecting this to result in Xi's resignation or regime change - these things are possible, surely, but it is a major task to achieve and the unity & scale of the protest movement remains to be fully seen. The government may retaliate with a hard crackdown as it has done with Tiananmen and other protests throughout the years. It may also quietly revamp some policies without publicly admitting a change in order to both pacify protesters and save face. The CCP often uses mixed tactics, both coopting and suppressing protest movements over the years depending on the situation. Changing from Zero Covid may prove more challenging though, given how much Xi has staked his political reputation on enforcing it.

What is important for everyone online, especially those of us abroad, is to watch out for the misinformation campaign the government will launch to counter these protests. Already twitter is reportedly seeing hundreds of Chinese bot accounts mass post escort advertisements using various city names in order to drown out protest results in the site's search engine. Chinese officials will also likely invoke the standard narrative of Western influence and CIA tactics as the reason behind the protests, as they did during the Hong Kong protests.

Finally, there will be a new surge of misinformation and bad takes from tankies, or leftists who uncritically support authoritarian regimes so long as they are anti-US. An infamous one, the Qiao Collective, has already worked to shift the narrative away from the protests and onto debating the merits of Zero Covid. This is largely similar to pro-Putin leftists attempting the justify his invasion of Ukraine. Always remember that the same values that you use to criticise Western countries should be used to criticise authoritarian regimes as well - opposing US militarism and racism, for example, is not incompatible with opposing China's acts of genocide and state suppression. If you want further info (and some good sardonic humour) on the absurd takes and misinfo from pro-China tankies, I would recommend checking out Brian Hioe in the links below.

Finally, keep in mind that this is a grass-roots protest made by people in China, who are putting their own lives at risk to demonstrate openly like this. There have already been so many acts of bravery by those who just want a better future for themselves and their country, and it is belittling and disingenuous to wave away everything they are doing as being just a "Western front" or a few "fringe extremists".

Links:

BBC live coverage page with links to analysis and articles

ABC (Australia) analysis

South China Morning Post analysis

Experts & Journalists to Check Out:

Brian Hioe - Journalist & China writer, New Bloom Magazine

Bonnie Glaser - China scholar, German Marshall Fund

Vicky Xu - Journalist & researcher, Australian Strategic Policy Institute

Stephen McDonnell - Journalist, BBC

M Taylor Fravel - China scholar, MIT

New Zealand Contemporary China Research Centre - NZ's hub of China scholarship (I was fortunate to attend their conferences during my PhD there, they do great work!)

If you've reached the end I hope this helps with understanding what's going on right now! A lot of us who know friends and whanau in China are worried for their safety, so please spread the word and let's hope that there is something of a positive outcome ahead.

#孟珏’s china corner#中国#上海#习近平#习近平下台#共产党下台#China#Shanghai#China protests#China protests 2022#Xi Jinping#Xi Jinping step down#CCP step down#Xi Jinping resign#CCP resign#乌鲁木齐#Urumqi#Urumqi fire#Urumqi apartment fire

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

THE SUPER SCUFFED THANATICA LABS MODERN AU

There is so much groundwork that me and my partner failed to cover/did not think about, but I think we're going to just lay out what we have and just build upon it as more solid ideas come to fruition, so here we go

THANATICA LABS

Research corporation funded by the Powers That Be(?)

Dedicated to defeating death by prolonging life

Akin to Black Mesa or Aperture Science - Unethical experimentation going on behind the scenes

-----

DANIIL DANKOVSKY

Maybe not the founder? Maybe lead researcher?

Maybe founded it when it was a small lab and was bought out by The Powers to greatly expand funding?

Not exactly on the level - HAS done and WILL do shady things again

KNOWS what he's doing is illegal to some extent, but he tries to wash his hands of the dirty work (alleviate some guilt maybe?)

Hands the recruiters a list of requirements for his new hires (potential lab rats), lets them do the searching and he'll conduct the interviews

I have no idea what these requirements are

Sometimes the lab assistants go missing, he doesn't know anything about that, don't ask him

He LIKES his designers clothes - SOMETIMES it comes from Thanatica's grant money, SOMETIMES it's a few hundred here or there, BIG DEAL

-----

ARTEMY BURAKH

Studied in the Capital or IS studying in the Capital, and is in SO SO SO much debt

Is having trouble getting work because nobody is going to hire a surgeon with no ACCREDITED experience (cutting up bodies in your dad's unlicensed clinic does not count)

Looking to expand the medical practices of his provincial studies(?)

Maybe father has an illness(?) Perhaps Isidor suffering some kind of debilitating disease called the sand pest?

Was contacted by Thanatica Labs for a low level Lab Assistant position - It's Thanatica Labs, of course he's going to respond, that's a lot of money for an entry position, and he's going to have his name attached to a prestigious establishment

He's hired - Is under the pretense he can save up some money, maybe get some lab experience to eventually propose his own research somewhere else

Alternatively, went to university, left university to go home to tend to family business, came back to the Capital to resume studies and is looking for ways to expand his thesis?

Keeps his head down and minds his own business, the less he's under the eye of the lead scientist, the better

Doesn't mean he isn't talking to people and keeping a watchful eye - things are happening that aren't adding up, and it isn't just the grant money

Because he's so desperate for a job, it may mean he's more agreeable to participate in some of Thanatica's shady dealings

-----

THEIR RELATIONSHIP

This is so stupidly long, continued under cut

Daniil interviews Artemy and is so rude and condescending about it

Artemy is either biting back insults or being too sassy for his own good

Artemy gets the job either way, but it's VERY funny to imagine that Artemy failed the interview UNCONDITIONALLY, but was hired anyway under the pretense that Daniil didn't expect him to stick around for very long

"He's so handsome, shame that he's such a dick"

"He's so handsome, shame that he'll be medically indisposed for the sake of research"

Artemy figures out Thanatica is doing illegal experimentation but somehow despite this, it sort of falls in line with what Artemy is hoping to accomplish with his own studies (untested and unproven methods of healing that haven't been approved by any board)

Artemy decides to do his own experimentation behind Daniil's back

Daniil smells something suspicious, equipment and samples are missing (its his lab, he WILL get to the bottom of this)

He's been watching the new hire closely (assessing his potential for experimentation), eventually finds out that he's been performing experiments of his own with methods he's never seen before

Wants to put him under a microscope (literal) --> Wants to put him under a microscope (figurative)

Their confrontation can go a couple ways

Daniil approaches Artemy and offers him the resources to continue his work in exchange for doing some underhanded deeds to progress Daniil's own research

OR Artemy blackmails Daniil with the evidence he's gathered in exchange for resources - Daniil is largely unfazed by this, but sees Artemy's morals aren't exactly on the level either and he finds him very interesting so he allows him his resources in exchange for dirty work

Laughing at the idea that Daniil finds out that Artemy has no accredited experience and he lied on his resume to get an interview - Now he's even MORE desirable for underhanded work (thank you inkpot-demigod)

This would be the point Artemy is bagging bodies

Starts off with superficial antagonistic attraction (purely on looks, otherwise has disrespect for each other, condescending and rude) --> eventually develops into mutual respect for each other's work (cordial, maybe even friendly, "oh god why do they keep looking at each other like that") --> eventually develops into unprofessional workplace relationship (they are fucking in places where they definitely have no business doing so)

-----

"can we have artemy need a place to stay and daniil offers a space in his apartment and artemy packs him lunches to take to work. daniil thinks he's being subtle but just the fact he's eating lunch... all of his coworkers Know"

At some point during the relationship (most likely early on) Artemy mentions that his lease is ending and he's going to need to spend time looking for an apartment (or suggests that he needs to find a roommate to save some money because BOY DOES HE NEED IT)

Daniil IMMEDIATELY blurts out that he has space in his apartment (HE IS NOT JEALOUS, THIS IS JUST THE MOST ECONOMIC AND REASONABLE CHOICE, HE IS THE LEAD RESEARCHER AND HE CAN AFFORD A NICE SPACIOUS PLACE THAT HAPPENS TO ACCOMMODATE TWO)

It's closer proximity to the lab

They can keep discussing things in the privacy of his home

Not that Daniil NEEDS to save money, but having some extra is a plus

Artemy makes meals, food just APPEARS and Daniil never has to think about it

Co-workers are noticing that Daniil is ACTUALLY bringing lunches and eating food, hmmm very suspicious.....

Eva (lab receptionist, more on this later) notices the two of them coming into work at the same time in alarming frequency both carrying lunches and she's like SUSPICIOUS EYEZOOM

-----

"if the kids are involved with this i think it'd be kind of funny if daniil and artemy are desperately trying to hide the fact that they kill people but the kids definitely know that they kill people"

Not sure if they can live in Daniil's apartment if Artemy and Daniil have a living arrangement - Could be frequent visitors if Artemy is living there

Not sure about their relation to Artemy - would love to have him be uncle to his brother's adopted kids but this might get complicated

The kids are savvy enough to know about fucked up corporations, they are doing some MURDER in there

"Are you a mad scientist?"

"No pumpkin, I do very important research to extend the human lifespan"

"Oh…. That means people are dying in there right?"

"……."

-----

"i'm having a vision of daniil wanting to properly court artemy after a few trysts but he doesn't communicate this very well and he also has very little experience with this so he invites him to a fancy dinner or maybe even a gala and artemy is clearly out of his element the whole time and daniil is trying to make this work and its NOT... if anything artemy thinks daniil is trying to pull some power move on him AND THEN. at the end of the evening when daniil is trying to charmingly flirt and do a kiss, artemy is just like. what are you DOING and they do at least SOME communicating. its a START. this au is a murder romcom"

Daniil coming to terms with the fact that he's so gay for the new hire, oh god he's so gay, who allowed Artemy to be so handsome AND intelligent AND clever AND funny what the hell

He keeps looking in Artemy's direction and Temy thinks he's scrutinizing his work, but god knows Daniil needs to get ahold of himself

He has an idea: Invite Artemy to the next charity gala, show him off to some higher ups, thus giving him the opportunity to sing his praises, and Artemy should get the idea, then later in the night have some drinks and who knows

Daniil extends the invite to Artemy, Temy thinks he's getting some kind of promotion, so he agrees

The event is way bigger and way fancier than Artemy was anticipating, Daniil is showing him off to a lot of executives and Temy is trying to hold his own here - If this is some kind of test, he's going to wring Daniil's neck

"Why is Daniil being so flattering, is he making fun of me"

The two are finally alone and Daniil is sitting where his leg is bumping into Artemy's, he has his hand on Temy's thigh and he's leaning in so, so, so close and Temy panics - Not that he doesn't have his share of attraction to his boss but what is he getting at here? Some kinda power move? A cruel test? Blackmail?

They have been misreading each other this entire time and the both of them are UNBELIEVABLY embarrassed

Time to talk things out and admit some things to each other

-----

SOME LOOSE MUSINGS ABOUT OTHER CHARACTERS

Eva Yan

Receptionist at Thanatica, maybe specifically for Daniil's office/lab whatever

The only thing that matters is that she always sees Daniil and Artemy going in and out of the place

Privy to a lot of gossip and goings-on of the place, knows about some of the shadier stuff but she's far from put-off

In fact, she wants to be Daniil's next experiment and he is not having it

Dresses like "I have to go to the office but I'm going to a music festival at 6" boho chic

Yulia Lyuricheva

Works for the government helping to orchestrate shady evil things but she's not actively invested in being evil this is just a job where she can apply her mathematical genius

Eva of course goes on about wanting to be an experiment and neither Eva's enthusiasm nor the fact that Thanatica is so shady is surprising to her

Clara

She doesn't have to be here but if she is here than she runs around Thanatica like a rat and no one knows where she came from

She claims to be an experiment gone wrong but really she is just a girl in need of some caring parental figures in her life

Lara Ravel

In the city on a revenge mission to kill Alexander Block for the death of her father

DANIIL AND LARA MURDER SPREE WHEEEEEEE LET THEM HAVE IT I WANT IT

I have no idea how to make this happen

Block

Thanatica is not surviving this one Dankovsky oooooo it is not surviving

Head of the military operation to destroy all evidence related to Thanatica's experiments?

Roles of other characters unclear..... To be determined....

THANK YOU FOR READING THIS TEXT DUMP, MORE TO BE ADDED IF WE THINK OF IT

446 notes

·

View notes

Text

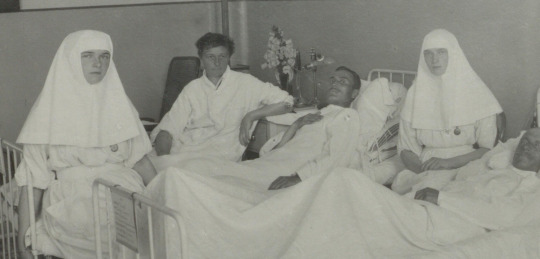

Vera Ignatievna Gedroits - the openly lesbian, first woman professor of surgery in Russia, who worked alongside the Romanovs

Princess Vera Ignatievna Gedroits was a doctor, surgeon, poet, and pioneer of medicine. Vera worked alongside Tsarina Alexandra and Grand Duchesses Olga and Tatiana Nikolaevna, working with the Red Cross to treat injured soldiers during the First World War.

** content warning for mention of suicide **

Born as a Princess of royal Lithuanian descent in 1870 in Kyiv, Vera is thought to have developed an interest in medicine following the passing of her little brother Sergei during childhood. Vera later wrote under the pen name ‘Sergei Gedroits’ in honour of him.

In 1892, Vera was arrested for participating in the Populist movement. Freed and undeterred, Vera was adamant to continue her medical studies. An open lesbian, Vera entered into a marriage of convenience with friend Nikolai Belozerov, permitting the obtaining of a new passport to travel, allowing her to pursue her dream of a medical career without the restriction of borders and her previous name being on police records. Despite their marriage being one of convenience, rather that romantic love, Vera and Nikolai were close friends, and stayed in contact through letters.

In 1903, Vera obtained the title of ‘female doctor’, but later that year attempted suicide. Vera’s mental health had declined due to an overwhelming personal family life, the death of her sister, exhausting workload, and breakup of a relationship with a lady in Switzerland. The following year, Vera had recovered, and the outbreak of the Russo-Japanese war led to her working in horse-drawn mobile hospitals.

Working with wounded patients, Vera took detailed notes which allowed the making of the connection between injuries and the weapon used to inflict them. Interestingly, Vera did not shy away from abdominal operations, which was irregular due to previous thoughts that such injuries were ‘inoperable’. Often, patients with such injuries were refused surgery and were sadly left to pass away.

Following the War, Vera worked provincially, attending to 125,363 patients. This pioneering work was recognised by Tsarina Alexandra Feodorovna in 1909, who invited Vera to take the position of Senior Court Physician. Vera was the first woman to serve as a physician in the Imperial Palace. Vera wrote ‘Conversations on Surgery for Sisters and Doctors’ to help the Palace understand the profession. Vera would eventually write 58 scientific papers. Vera earned a Doctorate of Surgery on May 11 1912, the first woman in the history of the University of Moscow to do so.

Following the outbreak of the First World War, Vera helped to install physiotherapy equipment and X-ray machines in hospitals to aid recovery. Vera taught Tsarina Alexandra Feodorovna and her daughters, Grand Duchesses Olga and Tatiana, medical work, and they assisted with operations. Vera worked alongside Imperial Physician Dr. Evgeny Botkin to help connect infirmaries to railways and supplies. Vera occasionally travelled to the front lines to help provide surgery directly at the scene, and in one case performed over 30 operations over a three day period.

Vera is recorded as having little patience for the infamous Grigori Rasputin, with one source recording the shoving of Rasputin ‘into a corridor when he refused to get out’ of the way.

There are no records that suggest that the patients or the Romanovs objected to Vera's sexuality, though there was disapproval of her continuing to remain in Tsarskoe Selo to continue military surgery after the Revolution. If anything, she was renowned as one of the most capable and intelligent women of the era. Vera wore a surgeon's cap rather than the head coverings that nurses and Sisters of Mercy wore.

During the First World War, Vera met fellow nurse Countess Maria Dmitrievna Nirod-Mukhanova, a widowed maid-of-honour at the palace. The pair fell in love and started a relationship, which would last for the rest of Vera’s life. Maria had three children: Dmitri Feodorovich, Marina Feodorovna, and Feodor Feodorovich. The children knew about their mother's relationship with Vera, as they lived as a married couple whilst caring for and raising them. Some sources suggest that Vera and Maria had a marriage ceremony.

By the late 1920s, Vera was living with Maria, who worked as a surgeon, in Kyiv after the couple and Maria’s children escaped Revolution, taking refuge with monks. They spent eighteen years together. The pair lived as a married couple. In 1932, Vera passed away aged 61 after a diagnosis of uterine cancer. Maria continued Vera’s work by operating a pharmacy that provided free medicine to the poor. Maria passed away in 1965 aged 86. The above image is the only photo that has been attributed to her.

Vera defied all the social norms, becoming a pioneer of medicine and challenging traditions within the profession, saving thousands of lives in the process. Vera’s legacy lives on today.

SOURCES:

Hands that bring back to life. Vera Ignatievna Gedroits - surgeon and poet by V.G. Khokhlov

Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library

Wartime albums of Olga Nikolaevna and Tatiana Nikolaevna, Last Romanovs on Flickr

The Princess who Transformed War Medicine - BBC

Princess Vera Gedroits: military surgeon, poet, and author by J.D.C. Bennet

The Diary of Olga Romanov : Royal Witness to the Russian Revolution by Helen Azar

Tatiana Romanov, Daughter of the Last Tsar : Diaries and Letters, 1913-1918 by Helen Azar and Nicholas B.A. Nicholson

#Vera Gedroitz#Vera Gedroits#lgbt history#lesbian history#Alexandra Feodorovna#Olga Nikolaevna#Tatiana Nikolaevna#Maria Nirod Mukhanova#medical history#Russian history#pride month#tw sui#image described#queer history

239 notes

·

View notes

Text

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

Really interesting thing about Les Miserables is that it combines a number of semi-independent stories - each of which, when isolated, is a fairly standard interpretation of a given trope - into a larger, inter-connected whole; and wherever the individual archetypes interact with each other, they set the stage for the introduction of things that are less generic and cannot be treated as a one-dimensional paradigm. Such a layered "collage" is possible because of two factors: first, a large (and varied) cast of characters; second, the fact that the events in the novel span a relatively long period of time (some 40 years*).

However, unlike many historical works of similar calibre, Les Miserables usually favors a surgical approach - in a way, the individual "puzzle pieces" and their intersections matter more than the final "big picture".

When you look at the collage, you start to notice patterns and parallels: how Éponine is a distant echo of Javert, and in turn how Grantaire can be likened to Éponine; the mirrored fates of Enjolras and Gavroche; the analogous-yet-divergent fates of Valjean and Fantine, and many more.

In and of itself, the joined tale of Marius and Cosette is a variation on the theme of Werther et al. But when you broaden your perspective and consider the preceding stories of the two characters, it suddenly expands beyond the conventions of the genre. They are more than archetypical Romantic lovers: Marius - by virtue of his conflict with his grandfather and his involvement in the June Rebellion; and Cosette - owing to the detailed account of her turbulent past. The lover, the wayward son and the patriot-martyr are all characters extremely common in nineteenth-century literature - it just so happens that Marius is all three. Similarly, Cosette's childhood is a typical, if harrowing, Realistic depiction of abuse and poverty; and yet she is also the angelic, aethereal "kindred spirit" venerated by the lovestruck Marius-Werther.

Then you have Valjean, whose life is part morality play, part Positivistic* success story, part psychological study of an eternal outcast; Javert, who is simultaneously a caricature of single-mindedness, a universal parable about the dangers of blindly following authority, and Hugo's way of critiquing the reactionary police-state of Napoleon III; Éponine, at once a cautionary tale and a sympathetic look at the seedy underbelly of 'civilised' society; and bishop Myriel, both a textually canonized saint and the jolly protagonist of a pastoral about the highs and lows of life in a provincial parish.

The characters evoke emotion not because they can be losslessly stencilled into the new millenium, but because their reality is multi-faceted enough for us to become immersed in it. It's as if Hugo put a bucket-load of archetypes and genres in a well-researched and digression-prone blender, and out of that marring of ideals came something that has perhaps lost some of its everyman appeal and universality, in favor of immortalizing a kaleidoscope view of life in the early eighteen-hundreds; and yet it remains relevant because the problems he tackles are relevant still.

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

01: Finding Place and Peace with Nature

Welcome folks to my Environmental Science Nature interpretation Blog! I am eager to share my thoughts, opinions, and some of my life with you all over the term. To orient you all, I am currently in my fourth and final term at the University of Guelph. My degree is in Arts and Science program with a focus on Biology and Psychology. I have experience in ecology, plant biology, and field experience that I will share with you all. Throughout my degree, I have found value in understanding how the natural world that surrounds us supports our functioning and the role we must have in protecting it.

From the ripe age of three, my parents bundled me up and took me on my first camping trip. I am reminiscent of those experiences as they have influenced my relationship with nature as a young adult. Hiking, youth groups, and time spent on the beach are some of the fondest memories of my childhood. Each summer, I have taken the initiative and have continued the camping tradition for myself. I am no longer reliant upon my parents to facilitate the trip and have introduced my closest friends to the joys of living with nature. Nature has taught me some of the most valuable lessons a child should learn and I feel inclined to share my lessons with those around me.

As a young adult, university has been a pivotal moment in my life. With university comes additional responsibility and pressure on the future. The COVID-19 pandemic commenced in my first year of study at the University of Guelph. The pandemic, in many ways, was a period of reflection and revaluation for my life and how I wish to lead it. In moments of high stress, I tend to forget the peace that nature brings. The pandemic allowed me to reconnect with nature the way I once did as a child and recentered my headspace.

More recently, I had the opportunity to travel to fourteen different countries across the United Kingdom and Europe. From breathtaking hikes in the Swiss Alps to walking the vineyards of Tuscany, I had the pleasure of exploring new areas and ecosystems of the world I never could have dreamed of experiencing. As I share stories of my adventures with those around me, I express the wonder and fulfillment I felt in those moments. Through facilitating conversations surrounding my travels, I remind my peers that nature does not need to be expensive or extreme. Nature is exciting in the simplest form and we as Canadians are blessed with an extraordinary country to explore. I have found a "sense of place" in some of the smallest corners of the world that ultimately challenged my perspective of what nature is capable of.

As described in the textbook, place is not a consistent entity; it may change and take new meaning through experiences (Beck et al., 2018). No one person or experience offered a sense of place in nature rather it has been a combination of many. As I have previously mentioned, I embark on a camping trip annually at one of our provincial parks. I have attended the same provincial park for nearly a decade. From the perspective of a young child, the campsite was simply a plot of land with large trees lining the perimeter as a source of protection; the beach was a place I would play and dive in to find beach glass. As I have matured, this "big picture" has evolved into a collection of smaller snapshots (Beck et al., 2018). I believe that the metaphorical lighthouse that guides my understanding of heritage will continue to change as I develop a stronger sense of self and interact with the environment (Beck et al., 2018).

In conclusion, my journey as an interpreter of nature is evolving. I found a voice and advocacy for our Earth in my travels. My metaphorical lighthouse has guided my path to places I have only dreamed of. The metaphorical lighthouses that assist in developing a "sense of place" may guide our path in several different directions throughout our lifetime (Beck et al., 2018). With each step, our connection and interpretation of the world around us may change (Beck et al., 2018). Like Shel Silverstein's, The Giving Tree, life will continue to evolve and in some moments we may take more of the Earth than we replenish. At the end of it all, it is our connectedness with others that can produce change. Regardless of socioeconomic status, there is wealth in the natural world that surrounds us all.

I have included some of my most favourite pictures of my adventures abroad. If you have been contemplating whether or not traveling abroad is worth it, this is your sign to book that flight!

References

Beck, L., Cable, T. T., & Knudson, D. M. (2018). Interpreting cultural and natural heritage: for a better world. Sagamore Venture.

Silverstein, Shel. (1964). The giving tree. Harper & Row.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

(...) For almost five centuries, their slave labour resulted in huge earnings for their masters: landowers, the feudal aristocracy and the Orthodox Church. Romani people's status was that of subjugated people, the absolute property of their masters: their masters' personality, faith and habits dictated their whole existence.

After 1500, even though the number of slaves decreased dramatically in Catholic and Protestant Europe - as slaves were transferred to overseas colonies to work - slavery flourished in Romanian Principalities. 'In the 16th, 17th, and 18th century we were probably the only country in Europe which had a class of people with this label of slave or bondsman', states Professor doctor Constantin Bălăceanu Stolnici.

Roma bondsmen were subjected to atrocious treatment.

For five centuries, they were denied the status of human being. Among the cruellest punishments was that of wearing a collar fitted with iron spikes on the inside that prevented the wearer from lying down to rest.

Most of the writing we have about this topic comes from foreigners travelers, staggered by this behaviour.

"The squires are their absolute masters. They sell or kill them like cattle, at their sole discretion. Their children are born slaves with no distinction on sex"

- Comte d'Antraigues.

Jean Louis Parrant, who was in Moldavia during the French revolution, asks himself: 'What can be said about this numerous miserable flock of beings (because they can’t be otherwise described) that are called gypsies and are lost for the humanity, placed on the same level with the cattle of burden and often treated even worse by the their barbaric master whose revolting (so-called) property they are?'

Mihail Kogălniceanu, a former Romanian politician who played a significant role in the abolition of slavery, remembers growing up in a provincial Romanian town and seeing people 'being with hands and feet enchained, with iron circles around their forehead or metal collar around their neck. Bloody whips and other punishments such as starvation, hanging over a burning fire, the detention barrack and the forcing to stay naked in snow or in the frozen water of a river - this is the treatment applied to the miserable gypsies.'

Legislative texts, referring to them under a double denomination - gypsies or bondsmen - stated that they were born slaves; that every child born from a slave mother was a slave; that their masters had power of life and death over them; that each owner had the right to sell or offer his slaves; and that every masterless gypsy is propriety of the state. The list goes on... (...)

In 1600, a gypsy fit for work was worth the same as a horse. In 1682, a gypsy woman was worth two mares with foals. In 1760, three gypsies were worth the same as a house, and in 1814, Snagov Monastery was selling a gypsy for the price of four buffalo. There were also cases when gypsies were sold according to their weight, exchanged for honey barrels, pawned off, or offered as presents.

The abolishment of Roma slavery began with young artistocratic Romanians leaving to study in Western Europe. Upon returning home, they gave voice to progressive ideas denouncing slavery.

At the same time, Western Europe, and France especially, exerted considerable pressure on the newly formed Romanian state regarding the abolition of slavery. In the middle of the 19th century, there were half a million slaves on Romanian territory: 7% of the population.

Unfortunately, until now, Roma slavery has not been yet included in most history school books, and there are still very few Romanians who are aware of this historical reality. (...)

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

Since today is Charlotte Robespierre’s 163’th birthday, I thought I’d attempt something I’ve not seen anyone else yet do, which is to write a mini biography over her entire life. I’ve already translated a study from the 1960s which deals with Charlotte, but since it’s a bit all over the place and spends almost more time describing the people Charlotte had any sort of connections with rather than Charlotte herself, I decided to try to make some more sense of things by a more chronological approach.

Marie Marguerite Charlotte de Robespierre was born in Arras on February 5 1760, around half past two in the afternoon. Her baptism record, written three days later, goes as follows:

”Today is the eighth day of the month of February, the year 1760. We priests of the parish of Saint-Étienne of towns and Diocese of Arras, have supplemented the ceremonies of the baptism for a girl born around half past two in the afternoon in said parish in the legitimite marriage of maître Maximilien-Barthélemy-François de Robespierre, lawyer at the Provincial Council of Artois, and of demoiselle Jacqueline-Margueritte Carraut, her father and mother; she was delivered by us parish priest the day after her birth, six of the same month and year as above, with the permission of the bishopric dated the same day signed by Le Roux, vicar general, and below, by ordinance Péchena. The godfather was master Charles-Antoine de Gouve, adviser to the King and his attorney for the town and city of Arras, subdelegate of the intendant of Flanders and Artois, in the department of Arras, of the parish of Saint-Jean in Ronville, and the godmother demoiselle Marie-Dominique Poiteau, widow of Sieur François Isambart, procurator to the said provincial council of Artois, of the parish of Saint-Aubert, who gave her the name Marie-Marguerite-Charlotte, and who signed with us the parish priest, and the father here present, the same act on the day and year mentioned above. The child was born on the fifth.

Marie Dominique Poiteau

De Gouve

Derobespibrre

Willart, parish priest of Saint-Etienne.”

That Charlotte wasn’t baptisted until three days after her birth may be a sign that her parents for a moment feared for her life, considering Charlotte’s three siblings — the older Maximilien (born 1758), and younger Henriette (1761) and Augustin (1763) — all were baptised the same days they had been born.

Charlotte would later recall the memory of her mother Jacqueline (1735) with fondness. ”Oh! Who would not keep the memory of this excellent mother!” she wrote in her memoirs. ”She loved us so! Nor could Maximilien recall her without emotion: every time that, in our private interviews, we spoke of her, I heard his voice alter, and I saw his eyes soften. She was no less of a good wife than a good mother.” But they did not get to keep her for long — on July 4 1764 Jacqueline gave birth to a baby who didn’t make it past his first twenty-four hours alive, and was buried in the Saint-Nicaise cemetery without having received a name. She was not to survive him for much longer, twelve days later she died as well, a few days before her twenty-ninth birthday. The funeral held the following day was, according to the mortuary act, attended by Jacqueline’s brother Augustin and Antoine-Henri Galbaut, Knight of Saint-Louis, assistant major of the Citadel, but not by her husband. In her memoirs, Charlotte reported that Jacqueline’s death had been ”a lightning strike to the heart” for him — ”He was inconsolable. Nothing could divert him from his sorrow; he no longer pleaded, nor occupied himself with business; he was entirely consumed with chagrin. He was advised to travel for some time to distract himself; he followed this advice and left: but, alas! We never saw him again; the pitiless death took him as it had already taken our mother.”

Different documents tell us that the father actually didn’t leave Arras until December 1764, five months after Jacqueline’s death, after which he sporadically appeared in his hometown, sometimes for months at a time. The last known stay is from 1772. It is nevertheless probable that he no longer was in a state to look after his children after the death of his wife, and therefore, as Charlotte recounts in her memoirs, quickly handed them over to different relatives. Charlotte and Henriette, seperated by an age gap of less than two years, were therefore sent to live with their two unmarried paternal aunts, Henriette and Eulalie de Robespierre. According to contemporary Abbé Proyart, who knew the family, the aunts ”lived in a great reputation for piety.” Maximilien and Augustin, the latter still with his wetnurse, were in their turn taken in by their maternal grandparents. According to Charlotte, the loss of their parents had left a big mark on the former:

”He was totally changed. Before that point he had been, like all children of his age, flighty, unruly, rash; but since from this time he saw himself, in the quality of eldest, as the head of the family, he became poised, reasonable, laborious; he spoke to us with a sort of imposing gravity; if he joined in our games, it was to direct them. He loved us tenderly, and there were no caresses that he did not lavish on us […] He had been given pigeons and sparrows which he took the greatest care of, and close to which he often came to pass the moments which he did not consecrate to his studies.”

The children were reunited every Sunday, during which Maximilien would show his sisters his drawings and place his sparrows and pigeons into their cupped hands. One time, Charlotte and Henriette begged him to let them have one of his birds, and after much hesitation he gave in, much to their joy. Unfortunately, some days later the girls forgot the pigeon in the garden during a stormy night, by which it perished. When he found out about it Maximilien’s tears flowed, and he rained reproaches on Charlotte and Henriette and refused to give his birds to them when he left to study in Paris. ”It was sixty years ago,” Charlotte writes in her memoirs, ”that by a childish flightiness I was the cause of my elder brother’s chagrin and tears: and well! My heart bleeds for it still; it seems to me that I have not aged a day since the tragic end of the poor pigeon was so sensitive to Maximilien, such that I was affected by it myself.”

On December 30 1768, Charlotte was sent off to Maison des Sœurs Manarre, — “a pious foundation for poor girls, who may be admitted from the age of nine to eighteen, to be fed, brought up under some good mistress of virtue and to improve oneself in lacing and sewing or in another thing which one will judge useful; to learn to read and write until they are able to serve and earn a living,” situated just across the border in Tournai (modern-day Belgium). She was actually a few months too young to be enrolled, but an exeption was made in her favor, obtained by the influence of her godfather Charles-Antoine de Gouve. Two years later Charlotte was joined at the convent school by Henriette, who in her turn was enrolled without yet having a scolarship. Perhaps this is a sign that their relatives were struggling to provide for the four orphans and thus had to send them away as quickly as possible. On October 1769, Maximilien was enrolled at the College of Louis-le-Grand in Paris, his taste for study having awarded him with a scholarship to the prestigious school, while Augustin in his turn was sent off to the College of Duoai. The children were thus dispersed and no longer saw anything of each other, except for in the summers when they were reunited in Arras. According to Charlotte these were days of great joy that passed too quickly, even if many of these years were also ”marked by the death of something cherished.” In 1770, their paternal grandmother died, in 1775 their maternal grandmother and in 1778 their maternal grandfather. 1777 saw the death of their father, who at that point was living in Munich, but it’s unknown if Charlotte and her relatives actually found out about it or not. Finally, on March 5 1780, Henriette was buried, a little more than two months after her eighteenth birthday. According to Charlotte, the death of the sister had a big impact on Maximilien, it rendered him ”sad and melancholy” and he wrote a poem in her honor. She does not, on the other hand, report how the death affected her, Henriette undeniably being the family member she had spent the most time together with… Nevertheless, she did not get a chance to say goodbye, as the names of neither her nor her brothers feature on the mortuary act of Henriette or any of the other dead relatives.

One year after Henriette’s death, Maximilien graduated from Louis-le-Grand, nine days after his twenty-third birthday. Now a fully trained lawyer, he returned to Arras to work as such. We don’t know when Charlotte left the convent school, but she soon enough joined her older brother. Augustin, however, Charlotte continued to see very little of, as Maximilien arranged for him to take over his scholarship and started his studies at Louis-le-Grand on November 3 1781. He didn’t return until 1787.

The siblings had obtained half of the 8242 livres from when their late grandfather’s brewery was sold to their maternal uncle Augustin in 1778, but they were still in a rough financial situation. In 1768 their father had resigned from any inheritance whatsoever from his mother ”both for me and my children,” a wish he had then repeated both in 1770 and 1771. In 1766, he had also borrowed seven hundred livres from his sister Henriette which he never paid back, leading to some tension between Henriette, her husband and Maximilien in 1780.

Charlotte and Maximilien at first moved into a house on Rue du Saumon, but their stay there was short — already in late 1782 they were forced to leave the house to instead move in with aunt Henriette on Rue Teinturiers. According to the memoirs of Maurice-André Gaillard, Charlotte told him in 1794 that she and Maximilien weren’t exactly welcomed with open arms by Henriette’s husband — ”It’s strange that you didn’t often notice how much [his] brusqueness and formality made us pay dearly for the bread he gave us; but you must also have noticed that if indigence saddened us, it never degraded us and you always judged us incapable of containing money through a dubious action.”

Eventually, Charlotte and Maximilien moved again, to Rue des Jésuites, and finally, in 1787, they moved from there Rue des Rapporteurs 9. There they were soon enough joined by Augustin, by now too a qualified lawyer. According to Charlotte’s memoirs, the bond between the three siblings was strong — ”good harmony would not have ceased for a sole instant to reign among us.” While her brothers worked, Charlotte took care of the house. We know the name of one of her domestics — Catherine Calmet, who helped Charlotte out for six months. When Calmet was arrested in Lille in 1788, Maximilien wrote a letter pleading in her favour: ”[Calmet’s] conduct appeared to me faultless during the time she stayed with me; I rejoice in her slightest recovery. As for the certificate you’re speaking to me about, my sister has told me that the girl brought it with her.”

The siblings had many friends. One of them was mademoiselle Dehay, who in 1782 gave Charlotte and Maximilien a cage of canaries which they both appriciated a lot. ”My sister asks me, in particular,” Maximilien wrote to her on January 22, to show you her gratitude for the kindness you have had in giving her this present, and all the other feelings you have inspired in her.” Mademoiselle Dehay would later also do other animal related favors for the two. ”Is the puppy you are raising for my sister as sweet as the one you showed me when I passed through Béthune?” Maximilien asked her in 1788. ”Whatever it looks like, we receive it with distinction and pleasure.”

Charlotte leaves a long list of Maximilien’s closest friends in her memoirs. Of those included there, important for her story as well is her brother’s fellow lawyer Antoine Buissart, ”intensely estimable savant” and his wife Charlotte. The couple lived on rue du Coclipas, a ten minute walk from Rue des Rapporteurs, and would become close with all three siblings. Another one of Maximilien’s colleagues that would play an important role in Charlotte’s life was Armand Joseph Guffroy, who, like Charlotte, witnessed Maximilien’s uneasiness when it came to the death penalty while the two worked as judges together.

Then there was the family — maternal uncle Augustin Carraut who with his wife Catherine Sabine (1740) had had four children — Augustin Louis Joseph (1762), Antoine Philippe (1764), Jean-Baptiste Guislain (1768) and Sabine Josephe (1771). The two paternal aunts Eulalie and Henriette had married in 1776 and 1777 respectively — Henriette to Gabriel-François Durut, doctor of medicine in Arras at the College d’Oratoire, Eulalie to Robert Deshorties, merchant and royal notary in Arras. Deshorties had five children from his previous marriage — two sons and three daughters. One of the daughters had according to Charlotte been courting Maximilien since 1786 or 1787. ”She loved him and was loved back. […] Many times it had been talk of marriage, and it is very probable Maximilien would have wedded her, if the the suffrage of his fellow citizens had not removed him from the sweetness of private life and thrown him into a career in politics.” However, if such plans existed, they were soon broken up by the revolution, and the step-cousin instead got engaged to another lawyer, Léandre Leducq, who she married on August 7 1792.

Charlotte was perhaps also finding love. Joseph Fouché was a science professor from Nantes, a year older than herself, who had joined her uncle Durut at the College of Arras in 1788. ”Fouché”, Charlotte writes in her memoirs, ”was not handsome, but but he had a charming wit and was extremely amiable. He spoke to me of marriage, and I admit that I felt no repugnance for that bond, and that I was well enough disposed to accord my hand to he whom my brother had introduced to me as a pure democrat and his friend.” But somehow, this engagement too ran out into the sand, and Fouché got married to Bonne Jeanne Coiquaud in 1792.

Life changed on April 26 1789, when Maximilien was elected as a deputy for the Estates General and settled for Paris for an indefinite period of time. Letters from Augustin to the family friend Antoine Buissart reveal that the he went to visit his brother in September 1789, as well as from September 1790 to March 1791. Charlotte may not have been so fond of Augustin’s trips, ”My sister must be very cross with me,” Augustin wrote to Buissart on November 25 1790, ”but she easily forgets, that consoles me, I will try to bring her what she wants.” Charlotte herself couldn’t or wouldn’t join him — ”I did not see [Maximilien] for the duration of the Constituent Assembly,” she affirms in her memoirs. In November 1791, after the closing of said assembly, Maximilien made a visit back to Arras, Charlotte, Augustin and Charlotte Buissart meeting him at the coach depot in Bapaume. In her memoirs, Charlotte could still remember the pleasure of getting to embrace her brother after not having seen him for two years. However, Maximilien’s stay was short, and on November 27 he was back in Paris to never see his hometown again.

Maximilien, like Augustin, frequently wrote long letters to Buissart, telling him about the situation developing in the capital. He did however never ask him to say hello to his siblings in them, nor do we have any conserved letters adressed from him to them. Charlotte still affirms that ”we wrote to each other often, and [Maximilien] gave me the most emphatic testimony of friendship in his letters. “You (vous) are what I love the most after the patrie,” he told me.” According to Paul Villiers, who claimed to have been Maximilien’s secretary for seven months in 1790, the latter also sent part of his deputy’s salary to ”a sister in Arras, whom he had a lot of affection of for.”

But despite the extra money, Charlotte and Augustin were having a hard time. “We are in absolute destitution,” the latter wrote to Maximilien in 1790, ”remember our unfortunate household.” Joseph Lebon, a former priest soon to be mayor of Arras, wrote to Maximilien on August 28 1792 that “the bearer of this letter, Démouliez, has planned arrangements with your brother, to procure for him the execrable silver mark.” They also had to deal with the loss of some more loved ones, as Henriette and Eulalie, the aunts that had had the raising of Charlotte and her sister, both died in 1791.

Even if Charlotte was unable to go to Paris with her younger brother, she was still politically active on a local level. This is shown through a letter dated April 9 1790 which she sent Maximilien:

”We’ve just received a letter from you, dear brother, dated April 1, and today it is the 9th. I don’t know if this delay is the fault of the person to whom you gave it. Please send it to us directly next time. At the moment, I’ve just learned that one is happy with the patriotic contribution. M. Nonot, always a good patriot, has just told me this news with this one which he has from M. de Vralie and which greatly formalizes those who love liberty. I don't know if you know that a whip-round was made about four months ago for the relief of the poor in the town. Each citizen contributed to it according to his faculties. Today the municipal officers are of the opinion that the whip-round should continue for another three months. There are many people who no longer want to pay. They give the reason that the poor should not be fed idle, that they should be made to work demolishing the rampart of the town. The mayor, who apparently knew that one would refuse to pay, said that if one refused to pay, he would obtain authorization from the National Assembly and tax himself what must be payed. If M. Nonot is not mistaken, for the remark is so ridiculous that I cannot persuade myself that it is true, M. de Fosseux will be busy, for there are those who will refuse on purpose in order to see what that will result in. I don't know if my brother has forgotten to tell you about Madame Marchand. We fell out with her! I took the liberty of telling her what the good patriots must have thought of her paper, and what you thought of it. I reproached her for her affectation of always putting infamous notes for the people, etc. She got angry, she maintained that there were no aristocrats in Arras, that she knew all the patriots, that only the hotheads found her paper aristocratic. She says a lot of nonsense to me and since then she no longer sends us her paper. Take care, dear brother, to send what you promised me. We are still in great trouble. Farewell, dear brother, I embrace you with the greatest tenderness. If you could find a position in Paris that suits me, if you knew one for my brother, because he will never be anything in this country. I am not sending you this letter by post in order to give the person who gives it to you the opportunity of getting to know you, which he has long wanted.”

However, contrary to her prediction that Augustin ”would never be something,” her younger brother was in fact elected to the council of administration of Pas-de-Calais in 1791, and in August 1792 prosecutor-syndic of the commune of Arras and president of les Amis de la Constitution. Finally, one month later, on September 16, Augustin was elected to fill a seat in France’s new government body the National Convention.

Thus, Charlotte’s hopes of going to Paris were finally coming true, as this time she was not left behind when Augustin once again set off for the capital. The first evidence of their arrival is from October 5, when Augustin’s name is first mentioned in the debates of the Jacobin Club in Paris. However, it’s possible Charlotte went to Paris still earlier, as she in her memoirs claims to have stood witness to a conversation between her older brother and his friend Jérôme Pétion ”a few days” after the Paris prison massacres between September 2-4. Maximilien would have reproached Pétion for not having interposed his authority to stop the excesses, to which the latter dryly would have replied: ”All I can tell you is that no human power could have stopped them.” Pétion also mentioned a meeting between him and Maximilien on the subject, but in his version it was rather he who accused Maximilien of doing a lot of harm — ”your denunciations, your alarms, your hatreds, your suspicions, they agitate the people; explain yourself; do you have any facts? Do you have any proof?”

Regardless, Augustin and Charlotte settled in the front of an apartment on 366 Rue Saint-Honoré, where their brother lodged since 1791. Owner of the house was one Maurice Duplay (1738), who lived there with his wife Françoise-Éleonore (1739) and their unmarried daughters Éleonore (1767/1768), Victoire (1769) and Élisabeth (1772), son Maurice (1778) and nephew Simon (1774). According to the memoirs of the youngest daughter, Élisabeth, Maximilien had become something of an additional family member — ”He was so nice! […] He had a profound respect for my father and mother; they too regarded him as a son, and we as a brother.” The letters Maximilien wrote to Maurice while on the short trip in Arras reveal that the feelings seem to have been mutual — ”Please present the testimonies of my tender friendship to Madame Duplay, to your young ladies, and to my little friend.”

Charlotte on the other hand, soon found herself on second thoughts regarding the family, or, to be more exact, Françoise Duplay. ”I should tell the whole truth,” she writes in her memoirs, ”I have nothing but praise for the demoiselles Duplay; but I would not say the same for their mother, who did me much wrong; she looked constantly to put me in bad standing with my older brother and to monopolize him.” According to Charlotte, the family exercised an ascendancy over Maximilien — ”founded neither on wit, since Maximilien certainly had more of it than Madame Duplay, nor on great services rendered, since the family among whom my brother lived had not for some time been in a position to render them,” which her older brother was simply too kind to stand against. Before, no one had interfered with Charlotte’s management over the domestic square, but now she was subordinate to Françoise, who treated Charlotte badly — ”if I were to report everything she did to me I would fill a fat volume” — and sometimes even drove her to tears. Françoise’s daughter Élisabeth, on the contrary, wrote in her memoirs that her mother loved Charlotte a lot, never refused her anything that could please her and even treated her as a daughter of her own.

Charlotte also had a hard time getting along with Éleonore, Françoise’s oldest daughter. According to Élisabeth and Maximilien’s doctor Joseph Souberbielle, she had been ”promised,” to the latter, something which Charlotte believed to be as false as later claims of Éleonore being her brother’s mistress. ”But”, she added, ”what is certain is that Madame Duplay would have strongly desired to have my brother Maximilien for a son-in-law, and that she forget neither caresses nor seductions to make him marry her daughter. Éléonore too was very ambitious to call herself the citoyenne Robespierre, and she put into effect all that could touch Maximilien’s heart.” All of this was once again to much distress for Charlotte, and, according to her, Maximilien as well, as he had no interest whatsoever in any type of marriage.

Charlotte was however on good terms with Éleonore’s two younger sisters — Victoire and, especially, Élisabeth. ”I have nothing but praise for [Élisabeth], she was not, like like her mother and older sister, stirred up against me; many times she came to wipe away my tears, when Madame Duplay’s indignities made me cry.” Élisabeth reported back that ”I was good friends with [Charlotte], and it was a pleasure to go see her often; sometimes I even pleased myself with doing her hair and her toilette. She too seemed to have much affection for me.” Charlotte often asked Françoise for permission to bring Élisabeth with her to the Convention, something which she agreed to. It was there, on April 24 1793 that Élisabeth met her future husband Philippe Lebas, who came up and asked Charlotte who Élisabeth and her family were, after which he urged the two to come to another session. They did so, bringing sweets and oranges, Élisabeth asking Charlotte if she could offer Lebas one. During yet another session, Lebas gave Charlotte and Élisabeth a lorgnette, while Charlotte showed Lebas Élisabeth’s ring, which the latter unfortunately brought with him without returning it. Charlotte consoled Élisabeth, telling her to be calm and that she would explain to her mother of how it had happened if she was to ask. But Élisabeth didn’t get her ring back until two months later, when she and Lebas also professed their love for one another. Françoise and Maurice agreed to let them marry, however, the engagement was soon complicated by Maximilien’s old collegue Armand Joseph Guffroy.

The lawyer had stayed in Arras at the outbreak of the revolution, authoring many pamphleths in support of the new developments. In them he often displayed radical ideas — among others things that women should have the right to be included as both electors and representatives in the new regime. He had also frequently corresponded with Maximilien about the situation in Arras (we have nine letters from 1791 conserved), before being elected to the National Convention on September 9 1792 and, like Augustin, heading to Paris in order to take a seat in the new government. Now he slandered Élisabeth to Lebas, saying that she had multiple love affairs. Élisabeth and Lebas soon discovered that he had only said so in order to get Lebas to marry his own daughter, Louise Reine, at that point already pregnant with the baby of her father’s printer. ”This malicious man was known less than favorably on more than one account,” Élisabeth bitterly stated in her memoirs, ”he knew only how to bad-mouth everyone; he was despised by all and viewed negatively by his colleagues. The Robespierre brothers had a great contempt for him…”

Six months before the marriage between Lebas and Élisabeth, Charlotte and her two brothers had dinner together with Rosalie Jullien, mother of the young Convention deputy Marc-Antoine Jullien. On February 2 1793, she wrote to her son: ”Robespierre, his brother and his sister are to dine with us today. I shall get acquainted with this patriotic family whose head has made so many friends and enemies. I am most curious to see him close up…” Eight days later, Rosalie could report that she had not been unhappy with the result: ”I was very pleased with the Robespierre family. His sister is naive and natural like your aunts. She came two hours before her brothers and we had some women’s talk. I got her to speak about their home life; it is all openness and simplicity, as with us. Her brother had as little to do with the events of August 10th as with those of September 2. He is about as suited to be a party chief as to clench the moon with his teeth. He is abstracted, like a thinker; dry, like a man of affairs; but gentle as a lamb; and as gloomy as the English poet, Young. I see that he lacks our tenderness of feeling, but I like to think that he wishes well to the human race, more from justice than from affection. Robespierre the younger is livelier, more open, an excellent patriot; but common for the spirit and of a petulance of humor which makes him make a noise unfavorable to the Mountain.”

On July 19 1793, a decree from the Committee of Public Safety tasked Augustin with the mission of going to the Army of Italy. ”It’s a painful mission,” Augustin wrote to Buissart the following day, ”I have accepted it for the good of my country; I’m convinced that I will serve it with utility, if only by destroying the calumnies with which my name has been nourished.” Perhaps Charlotte saw this mission as an opportunity also — an opportunity to escape the circumstances which her conflict with Madame Duplay had put her in and get to see new parts of the country. She asked to be brought along, which her younger brother joyfully agreed to, and the two departed together with Jean François Ricord, another representative on mission, and his wife.

Augustin was right in that the mission would be painful, something which Charlotte too would go on to carefully describe in her memoirs. On their way to the army, they made a stop in Lyon, which was currently in insurrection. Augustin and Ricord went into the Hôtel de Ville to talk to some municipal officers, while Charlotte and Madame Ricord remained in the carriage. They were soon surrounded by a growing crowd, showing them their national cockades as proof of their patriotism and asking what was said of the lyonnais in Paris. The two women answered that they knew nothing about it. Meanwhile, Augustin and Ricord conversation with the municipal officers had erupted into a quarrel, and the two representatives decided it was best both to leave Lyon as well as abandoning the main route when doing so. They set out for Manosque where they remained for two days, but their stay there, as Charlotte admitted, ”was not without danger.” They were badly regarded by the people who reconized them and had two soldiers brought along for protection. When it was time to resume the journey, said soldiers they went ahead in order to scout out the country. As the group was preparing to cross the banks of Durauce, the soldiers returned in a hurry to tell them about Marseillais armed with canons on the opposite bank. They therefore returned to Manosque from which they then went to Forcalquier without misfortune, where they were offered services and supper. But hardly had they sat down at the table after not having eaten since morning when an express from the mayor of Manosque came to tell them to take flight immidiately as the Marseillais were once again in pursuit of them. It was eleven o’clock in the evening, and the only course to take was to reach the mountains between Forcalquier and the department of Vaucluse. They took horses, since a carriage would prove useless in the mountains, and walked the whole night on horrible roads, scaling uneven cliffs where the animals had difficulty carrying them and were constantly making false steps. The next morning the group reached a village where the pastor showed them hospitality, and after having taken a few hours rest, they were on the road again, reaching Sault in the evening. After three pleasurable days spent there, they returned to Manosque, lying about being followed by six thousand troops in order to keep the situation under control. Finally, after a troublesome journey, they reached Nice in the beginning of September.

Public spirit in Nice was no better than in all of Provence, but there they at least had no counter-revolutionaries after them. The general in chief, Dumerbion, and his general staff protected Charlotte and Madame Ricord while Augustin and Jean François made frequent outings. But there was still unsafety to be reckoned with. Charlotte remembered that she and Madame Ricord stopped attending the theater after having hostile locals attempt to throw apples at them. They instead kept occupied by making shirts for the soldiers, and in the evenings they went for walks and horseback rides in the countryside. But soon, ”several journals paid by the aristocracy” back in Paris started accusing them of acting like princesses with their equestrian outings, and Maximilien wrote to let his siblings know. Augustin vetoed any more horse back rides, and Charlotte promised to abstain from riding from then on. But not long after, Madame Ricord, who according to Charlotte ”was the most frivolous and inconsiderate person in the world,” proposed they should go on yet another one. Charlotte reminded her of what her brothers had said, but Madame Ricord just laughed it off. As the coach and the horses were already prepared, Charlotte resigned and joined her on the ride.

Two days afterwards Augustin returned. When he didn’t reproach Charlotte for the carriage ride she assumed he was aware of the fact she had been forced into it. But the following day he did call her out for it, and Charlotte, feeling the need to explain herself, called Madame Ricord to testify that the ride had been her idea. To her ”surprise and indignation”, Madame Ricord, instead of telling the truth, enforced the lie that it was Charlotte that had wanted the ride and taken her with her against her will. Augustin chose to believe her, much to Charlotte’s distress. ”[Augustin] knew I was incapable of lying. Why then did he not want to believe me?” Charlotte wept much over the scene when she was alone, but refused to show anything to her brother, who didn’t speak more about the incident but kept a certain coldness in regards to Charlotte which caused her more despair.

Then, Madame Ricord suggested to Charlotte that they should go to Grasse together, which she agreed to. But hardly had they arrived when a letter was brought to Madame Ricord. Madame Ricord told Charlotte that the letter was from Augustin and that he prayed her to return as promptly as possible to Paris. Charlotte was shocked, but nevertheless obeyed, the next morning she got into a private coach and went back to Paris.

Charlotte would later refuse to believe that Augustin had actually asked her to leave — according to her, Madame Ricord must have forged the letter and afterwards slandered her to her brother, saying that she didn’t care about him and that this was the reason for her brusque departure. But Charlotte also hints at there being something more between Madame Ricord and Augustin: