#AND!!!! absolutely moctezuma

Text

/ All I know is;; Daybit Sem Void supremacy 😳

#;ooc#ooc#/WHERE DO U ALL SEE THE S.POILERS OF THE F.GO X ARCADE COLLAB I WANNA SEE-!#/it is the start of summonable c.amazotz SO true#still praying one day we get an argentinian servant 🙏#AND!!!! absolutely moctezuma#mocte 🤧🤧🤧🤧🤧 pls come home 😭😭😭🙏🙏🙏#ALSO UNRELATED BUT FU CKKCKKVCKCKCK!!!!! N.YARJU IS COMING ON THE 28 IM CRYING WHAT THA HELLL!!!!!!!!!#LITERAL SPOOK!! THIS WAS NOT EXPECTED AT A L L#i thought he was coming in two years!! insanityyyyy#also for the peeps who have jap f.go accounts- how do u do it-#bc when i downloaded f.go japan on q.ooapp or apkpure; it did let me open but i couldn't play it#i wanna have one in case my beloved c.amazotz drops 🤧🤧#CONSTANTINE. do y ever think about how u could have a constantine in ur pocket in f.go japan#tezca- o.beron- charlie- in a future maybe mocte- too many cool servants!! and two years or more until they come noooo 😭😭

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Have the other Mesoamerica beings done anything wrong?

Ok so like, for the longest time Quetzalcoatl was the only Mesoamerican servant in FGO (no I don't count Jaguar man) but now with LB7, there's a few more members! While it's very possible someone else will do a HDAW blog for any of them, I've decided to make this one post about them and whether or not they've done wrong.

Major Spoilers for LB7 ahead. But you probably knew that.

Tezcatlipoca

Yes, he's absolutely done a lot wrong. If the very idea of you pisses off someone as pure and amazing as Quetzalcoatl, you done fucked up. Also he made a shit host for himself too. And the whole... wanting to wake up ORT thing too.

Tenochtitlan

Yeah, the fucking city. Yes she has some sins, attacked Kukulkan, and slandered Quetzalcoatl, so those are some BIGASS strikes. She has a kinda cool design tho, so could be worse. Also she slanders the conquistadors so more good points.

Ixcalli

Apparently is Moctezuma II? Lead jaguar dudes in killing dinosaurs, very very BIG strike there! But also didn't wanna end the world so that's something.

Camazotz

Was kinda a bitch the whole time. But also fought ORT, so that's dope actually. Also we wouldn't have Kuku without him (or Daybit) so like.... I do gotta admit he's not as bad as I'd say otherwise. Even if I don't like his vibes.

Kukulkan

I know I already covered her before in the actual daily, and will continue to do so, but still. Absolute perfection, never ever done anything wrong and neve will! 🥰 also destroyed ORT for good (well a weaker one) so even more amazing!!!!

Those are my totally not at all biased thoughts on the other mesoamerican beings of FGO. Here's hoping for more in the future, that also are treated better.

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Going down the rabbit hole over a comet that never existed

The other day i spotted someone's fursona with the name Tlayoualo, a Nahuatl-inspired name composed of the following word structure:

Tla- (Nahuatl: nonspecific object prefix) +

yohualli / youalli (Nahuatl: "night", "darkness", "shadow") -

-li (Nahuatl: absolutive object suffix) +

-o (Spanish: masculine object suffix)

“The Dark One” very much fits the vibe of their sona.

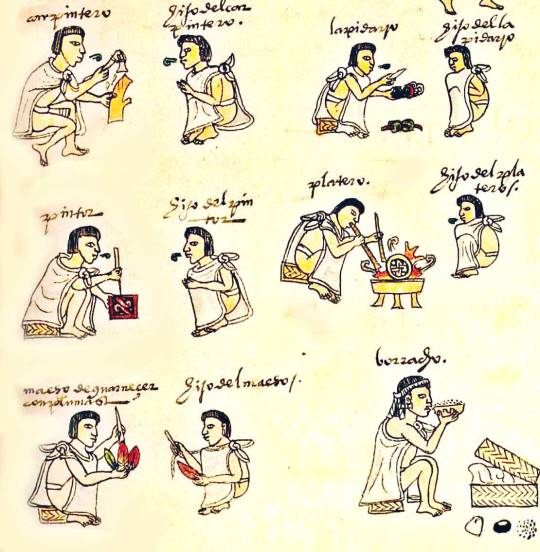

They self-identify as a "modern tlacuilo", which is the Nahuatl term for an "artisan" in Pre-Hispanic Mexico. The exact meaning of tlacuilo in English (and Spanish) varies but generally it was a man who is a skilled painter, illustrator, scribe, and/or sage. Tlacuilo were almost always people of royal pedigree, with the rare exception of a particularly gifted commoner being chosen by a noble to join the calmecatl (Nahuatl: private academy for the sons of Aztec nobility; lit. "group of buildings"). These people could remember past events in exquisite detail and could be consulted on a wide variety of topics (i.e. religion, politics, art, relationships, botany, etc). They were also skilled in painting, sculpting, cartography, and other such arts.

Codex Durán

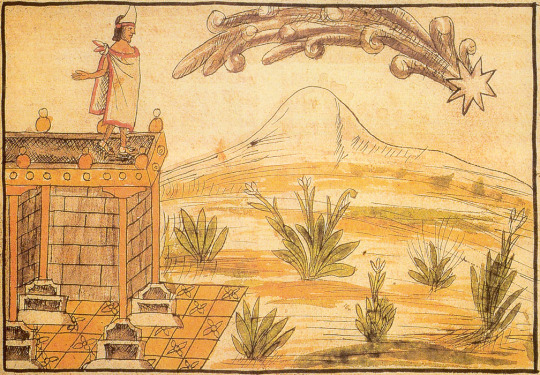

Among the works of the Mexican codicies I found an interesting painting in the first page of Codex Durán. It depicts Moctezuma Xocoyotzin (c.1466–1520) standing atop his royal residence observing a comet in the skies over [what appears to be] Popocatépetl. The story goes that Moctezuma consulted a tlacuilo, who told him it was a sign of something major to come. What that impending event was the tlacuilo could not tell.

Moctezuma Xocoyotzin, the final monarch of the Aztec Empire, standing atop his royal residence observing a comet in the skies over [what appears to be] Popocatépetl.

I wasn't sure if this was a metaphorical or literal depiction of historical events, so I went rummaging through the archives to see if any notable comets appeared in the night sky between 1502 and 1520, which are the beginning and end dates of Moctezuma's administration. If this comet was real, and the mountain depicted is in fact Popocatépetl (which east of Tenochtitlan/Mexico City), then the comet would appear to rise up from behind the mountain at dawn and would be absolutely amazing to see in person.

I couldn't find anything.

The comets that best fit that timeline were the Great Comet of 1471, which was visible in the northern hemisphere when Moctezuma was 5 years old, and a visit from Comet Halley in 1531, eleven years after Moctezuma's death. Unless NASA failed to identify any other bright comets during that time frame and everyone around the world just decided not to mention it other than what's in this codex, the comet depicted has to be fictitious.

Diego Durán & Gaspar da Cruz

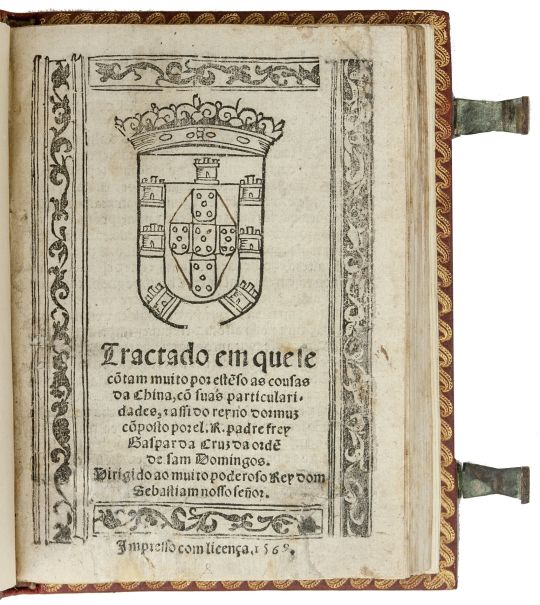

Diego Durán (c.1537–1588), the Spanish-born Dominican friar who created the Codex Durán, was inducted into the Dominican Order in Mexico City in 1556, the same year as an exceptionally bright comet that was noted by people around the world. Relevant to this rabbit hole is Portuguese Dominican friar Gaspar da Cruz (c.1520–1570), who in late 1556 visited the Portuguese outpost on the island of Lampacau in what is now Guangzhou, China. He returned to Portugal in 1565 and in 1569 wrote the first book written by a European that was dedicated exclusively to China.

In his 1569 book Tractado em que se[n]tam muito por este[n]so como cosas de China, con[m] sus particularidades, [y] así el reino no duerme, Gaspar da Cruz claimed that the Great Comet of 1556 was responsible not only for the devastating 1556 Shaanxi earthquake in China, but was an omen of the end times for the entire world. He even suggested the comet could be a sign of the birth of the Antichrist.

Digital scan of the front cover of Gaspar de Cruz's 1569 book "Tractado em que se[n]tam muito por este[n]so como cosas de China, con[m] sus particularidades, [y] así el reino no duerme." The title in English: "Treated in that it is also very much like things from China, with[m] its particularities, [and] thus the kingdom does not sleep".

Meanwhile, in 1561, Durán completed his training and went on a missionary expedition to Oaxaca, an indigenous village turned missionary outpost about 350 km to the southeast. Around 1573, Durán became vicar of a newly constructed convent in Hueyapan, Morelos, another indigenous village turned missionary outpost located only 75 km southeast of Mexico City. It was here that Durán compiled most of the tales he learned of during his previous missionary work in Oaxaca.

If the book mentioned previously arrived in the hands of Durán from Mexico City, then this could have inspired him to produce a fictitious depiction of a brilliant comet foreshadowing the demise of the Aztec Empire in Codex Durán, which was created from 1574 to 1576.

And that's the bit! Or is it? 😏

Start | Next >

#mexican history#Chinese history#nahuatl#nahua#indigenous#colonization#art#art history#photography#astrophotography#astronomy#comet

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

I am doing up another movie of the day/countdown to Halloween where I'll recommend funky, funny, scary or bloody horror

Pregame to the countdown (like El Superbeasto was, tonight we are watching Alucarda (1977) dir. Juan López Moctezuma

This English language Mexican Supernatural film is jammed packed with things like Demonic Possesion, devil worship, vampirism, and plenty of homoroctic scenes all while classically telling the tale of a young girl who arrives at a convent and befriends a strange young lady and strange events begin to happen.

The Cinematography in this film is absolutely stunning and it's not hard for anyone to fall for the characters, the acting serves well for the vibe and aesthetic that the film tries to give off.

This film doesn't necessarily fallow your conventional classic horror tropes, it passes as non sensible, strange, and out of this world which makes probably one of the most creative films I've seen, especially for a exploitation film.

The fact that Alucarda is just an anagram for Dracula is absolutely genius and imagination behind it all is just wow.

The sets are absolutely impressive, the fashion and costumes just scream 70s and overall it's just a wonderful dreamy surreal film.

Also this poster is just is just so cool

#alucarda#films#70s horror#70s#countdown to halloween#one movie a day#might call this Rammstein's countdown to Halloween#rammstein is a character I made for a horror script I am writing#i am not a critic#i also don't think there is really a bad movie its just all opinion#hippie with a horror movie addiction#Rammstein's Countdown to Halloween 2023

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

So fringe theory time:

The european conquistadores would have tried to salvage as much they could about the land of mexico tenochtitlan to make up for literal sedition and insubordination fleeing the old world and cuba to avoid arrest because the king said NO and Cortes said SI. He was a dead man if he returned empty handed or without some compensative atonement.

Any how. My guess is they said nope. Nope. No. Fuck. No. Omg. Dear god. AH!!! 😫😩😖🫠🫥😵💫🥴

When i presume they were given psychoactive and psychedelics as welcome ceremony for presumed carried away Quetzalcoatl hath arrived as prophecised.

The thing is they probably were not only not accustomed to such mind bending, reality warping things that "powerful" when compared to like tobacco and alcohol and wine and even old time cannabis (lower thc concentration in the genetics). We talking peyote. Shrooms. That one pseudo lsd substance the Mayans discovered. And or DMT and enemas. That mixed in with the metal ass air about the regime in contrast to the marvelous city they felt so enchanted with. Like we werent that far different. We had society. We had classes. We had religion. We had state. We even had state religion, which woulda felt like old time to the Europeans. However men in such circumstances AND upbringings not that prepared to handle such sinking in of thought and or knowledge was like beyond anything i daresay saving. The Aztecs and even Mayas like tee heee why they so stressed the fuck out? (They were kinda hardcore with their ceremonial stuff). That also making them in their trips like soooooo damn stressed tf out. Omg!!! Hernan! This stuff feels demonic. Im not having fun, AT ALL. The brutal elements of the kingdom basically ACCENTUATED like an arched back. With so little time too. They got lucky and they knew their whole going with it was only going to last so long before they had to decide how to stay alive and not return to get imprisoned or sent to gallows. Moctezuma was like: my Lord. Hernan like: o uh yes. It is I. I have arrived.

Moctezuma: as you had promised.

Hernan not yet disclosing his worst case scenario was burn down all their ships at the coast to not allow any of his men to escape and mutiny. He needed all of them. He was a dead man with empty hands before the King. Made it clear he was ignoring the orders from the King himself leaving Spain quickly and then Cuba as well once word was out about him being wanted and sent back to Spain.

So he had the most consequential decisions to make.

And yeah the whole thing is it was probably that fuckin simple. While tripping they probably thought the buildings and masonry was alive or something. More the reason to raze it. Claim it all in the name of the King and his seal(?).

He was absolutely successful at staying alive. And not having his future ruined. He was awarded titles too.

0 notes

Text

This is absolutely fascinating, full text under the cut. (Obvious CNs for racism, colonial violence, Hitler mention and white supremacy.)

When he stepped ashore in October 1492, in what he understood to be part of India or Japan, Christopher Columbus’s first act was to claim possession of the land for the Spanish crown. After that, he distributed cloth caps, glass beads, bits of broken crockery, “and many other things of little value” to its inhabitants, recording in his diary that they were a “very simple” people, who could easily “be kept as captives…[and] all be subjugated and made to do what is required of them.” They reminded him of the aboriginals of the Canary Islands, the most recent victims of Castilian conquest, Christianization, and enslavement. “They are the colour of the Canarians, neither black nor white,” he observed.

Columbus also believed that the “Indians” regarded him and his crew as celestial beings. His earliest description of this, two days after landfall, was unsure: “We understood that they asked us if we had come from heaven.” But speculation soon hardened into certainty. Though the natives “were very sorry that they could not understand me, nor I them,” Columbus nonetheless confidently surmised that they were “convinced that we come from the heavens.” Every tribe he met seemed to think the same: it explained why they were all so friendly.

Over the decades that followed, this notion became a staple of Europeans’ accounts of their reception in the New World. According to the sixteenth-century Universal History of the Things of New Spain, compiled by a Franciscan friar in Mexico, Hernán Cortés’s lightning capture of Moctezuma’s empire in 1519 was made possible by the Aztecs’ misapprehension that he was “the god Quetzalcoatl who was returning, whom they had been and are expecting.” The following year, while rounding the tip of South America, Ferdinand Magellan’s crew encountered a giant native, “and when he was before us he began to be astonished, and to be afraid, and he raised one finger on high, thinking that we came from heaven.” The Incas of Peru initially received Francisco Pizarro as an incarnation of the god Viracocha, so one of his companions later wrote, and venerated the conquistadors because “they believed that some deity was enclosed within them.”

It was a popular, endlessly elaborated trope. By the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, white men colonizing other parts of the world were hardly surprised anymore to encounter similar instances of mistaken deification. After all, the error seemed to encapsulate the innocence, intellectual inferiority, and instinctive submissiveness of the peoples they were born to rule. What’s more, as Anna Della Subin explores in her bracingly original Accidental Gods, unsought divinity was a remarkably widespread phenomenon that spanned centuries and continents.

I In Guiana, the long-lived prophecy of “Walterali” commemorated Sir Walter Raleigh’s supposedly providential exploits against the Spaniards. In Hawaii, the death of Captain James Cook came to be regarded as the tragic apotheosis of a man mistaken for a god. Across British India, shrines sprang up around the graves and statues of colonists who were worshiped as deities with supernatural powers. The tomb of Sir Thomas Beckwith in Mahabaleshwar acquired a clay doll in his image, which received offerings of plates of warm rice. In Bombay, the effigy of Lord Cornwallis, the former governor-general, came to be permanently festooned with garlands and beset by pilgrims performing darshan, the auspicious ritual of seeing and being seen by a god who was present inside his likenesses.

Even as they battled to convert the local heathens from their misguided ways, Christian missionaries met the same fate. Long after he’d returned to Scotland, a portrait of the first chaplain of St. Andrew’s Church in Bombay, the Presbyterian James Clow, became the object of pagan veneration. In the church vestry, the congregation’s “native servants” offered up ritual homage to it and tried to carry off pieces of the canvas as personal talismans.

An especially celebrated cult grew up around the ferocious soldier John Nicholson, a staunchly Protestant Northern Irishman who’d begun his career in the disastrous British invasion of Afghanistan in 1839, then rose to become deputy commissioner successively of Peshawar and Rawalpindi. He was an unspeakably brutal man, who kept a severed human head on his desk, frequently expressed his immense hatred for the entire subcontinent, and begged his superiors to allow him to flay alive and impale suspected rebels—so instinctively violent were his proclivities that “the idea of merely hanging” insubordinate Indians was “maddening” to him. Yet before he died, while leading the pitiless British invasion, slaughter, and looting of Delhi in 1857, he had inspired a cult of hundreds of indigenous “Nikalsaini” followers, army sepoys and ascetic faqirs alike, who surrounded his unwilling figure at all hours, solemnly chanting prayers and rendering obeisance to their idol.

Something similar befell General Douglas MacArthur, the conquering hero of World War II. From Panama to Japan, Korea to Melanesia, his persona was made to take on divine properties of different kinds, in the form of wooden ritual statues, shamanistic shrines, and spirit persons, and as an avatar of the Papuan god Manarmakeri, whose return will herald the age of heaven. Even Western anthropologists not infrequently became enmeshed as involuntary deities in the very value systems they were trying, as neutral, external observers, to describe.

Resistance was always futile: disclaiming one’s divinity never seemed to dispel it. Nicholson was deeply revolted at being worshiped. He raged against the Nikalsainis who followed him around, kicked them into the dirt, beat and whipped them savagely, and imprisoned them in chains, yet they interpreted all this as “their god’s righteous chastisement.” “I am not God,” Gandhi repeatedly yet fruitlessly declared from the early 1920s on, as ever more elaborate tales began to spread about his supernatural powers, and he was pestered incessantly by people wishing to touch his feet. “The word ‘Mahatma’ stinks in my nostrils”—“I am not God; I am a human being.”

In 1961 a group of Jamaican Rastafarians traveled to Addis Ababa to meet for the first time with their living god, Haile Selassie. They were unfazed by the aging Ethiopian emperor’s own stance on the matter: “If He does not believe He is god, we know that He is god,” his apostles maintained. In despair, the Jamaican government invited Selassie for a state visit, hoping that his public disavowal of their delusions would sap the movement’s growing strength and political clout. “Do not worship me: I am not God,” the diminutive septuagenarian politely beseeched his dazzled followers when he arrived in the Caribbean. But this only had the opposite effect, for Rastafarian theologians knew full well what the Bible taught: “He that humbleth himself shall be exalted, and he that exalteth himself shall be abased.”

What are we to make of such episodes? As Accidental Gods brilliantly lays out, European observers were quick to jump to obvious-seeming conclusions. Accidental divinity bespoke the natives’ recognition of the personal greatness of their overlords: Nicholson was adored because he epitomized “the finest, manliest, and noblest of men,” as a typical Victorian paean put it. The question of why such worship sometimes alighted on arbitrary, obscure, and unheroic figures (violent sadists, deserters, anonymous memsahibs) was submerged beneath the general idea of effeminate natives in thrall to their masculine conquerors.

It was also believed to testify to their intellectual inferiority. As the academic study of religious beliefs developed over the course of the nineteenth century, European scholars defined “religion” in ways that classified the practices of “uncivilized races” as superstitious, backward, or “degenerate”—thereby further justifying colonialism. Compared to “real” religions with fixed temples, scriptures, and “rational,” monotheistic worship, above all Christianity, the beliefs of “the lower races,” they theorized, were stuck in an earlier stage of development. The worship of deified men was a primitive category error, “the irrational, misfired devotions of locals left to their own devices,” in one of Subin’s many luminous turns of phrase: proof of their inability to rule themselves.

In reality, from Columbus onward, Europeans repeatedly blundered into situations they didn’t properly understand and whose meaning they then invariably recast as vindicating their own actions. Across the Americas, the Pacific, and Asia, the indigenous terms and rituals applied to them were in fact commonly used of rulers and other powerful figures, not just of deities, and signified only awe, not some separate, nonhuman, “godlike” status. Likewise, because sudden death precluded reincarnation, people in India had for millennia been accustomed to appeasing the powerful spirits of those who were therefore eternally trapped in the afterlife—that, not reverence for white superpower, was why they singled out many random, prematurely deceased Britons for the same treatment. Nor was the apotheosis of living colonists usually intended to honor them, let alone to reflect some personal virtue: it was simply a way of mediating and appropriating their power, one way of creating collective meaning in the midst of imperial precarity and violence.

Above all, the very idea of a binary division between humanity and divinity was itself a peculiarly Christian dogma. In most other belief systems, the two were not strictly separated but overlapped. Reincarnations, communications with the spirit world, living gods, avatars, demigods, ancestor deities, and the powers of kings and lords—all were part of an interwoven spectrum of natural and supernatural authority. Much the same had been true in European antiquity. The ancient Greeks thought it normal for men to become gods. Among the Romans, apotheosis became a tool of statecraft, the ultimate form of memorialization. Cicero wanted to deify his daughter, Tullia; Hadrian arranged it for his wife and his mother-in-law, as well as for his young lover, Antinous. For emperors, it became a routine accolade—“Oh dear, I think I’m becoming a god,” Vespasian is said to have joked on his deathbed in 79 CE.

Similar ideas circulated among Jesus’ early followers. It was only from the Middle Ages on that the notion of humans being treated as gods came to be regarded by Christians as absurd, despite the fact that their own prophet, saints, and holy persons embodied similar principles. And so it happened that modern Europeans ventured abroad and began to impose their own category errors on the views of others. As Subin tartly observes, “correct knowledge about divinity is never a matter of the best doctrine, but of who possesses the more powerful army.”

Though Accidental Gods wears its learning lightly and is tremendous fun to read, it also includes a series of lyrical and thought-provoking meditations on the largest of themes. How should we think of identity? What is it to be human? How do stories work, grow, and stay alive? Belief itself, Subin suggests, is as much a set of relationships among people as it is an absolute, on-or-off state of mind. European myths about the primitive mentalities of others served to justify colonization and theories of white supremacy, and still do. Regarding indigenous practices as antithetical to the “reasoned” presumptions of “developed” cultures has always allowed Western observers to overlook their complicity in creating them—to see them only as the errors of “superstitious minds, the tendencies of isolated atolls, rather than a product of the violence of empire and the shackling of peoples to new capitalist machineries of profit.”

It also serves to mask the extent to which Western attitudes depend on their own forms of magical thinking. Our culture, for example, fetishizes goods, money, and material consumption, holding them up as indices of personal and social well-being. Moreover, as Subin points out, none of us can truly escape this fixation:

Though we may demystify other people’s gods and deface their idols, our critical capacity to demystify the commodity fetish still cannot break the spell it wields over us, for its power is rooted in deep structures of social practice rather than simple belief. While fetishes made by African priests were denigrated as irrational, the fetish of the capitalist marketplace has long been viewed as the epitome of rationalism.

To see a myth is one thing; to grasp it fully, quite another. It turns over, changes its shape, slips away, fades out of view. The further back in time Subin ventures, the more fragmentary her sources become, the larger the gaps in what they choose to notice. But more than once she is able to illustrate, almost in real time, how indigenous and Western mythmaking can be intertwined, codependent, and mutually reinforcing.

Following its “discovery” by Captain Cook in 1774, the Melanesian island of Tanna was devastated by centuries of colonial exploitation: its population kidnapped to provide cheap labor, its landscape stripped bare for short-term profit, its culture destroyed by missionary indoctrination. By the early twentieth century this treatment had provoked a series of indigenous messianic movements that looked forward to the expelling of the colonizers and the return of a golden age of plenty. The messiah would incarnate a local volcano god, it was believed, though the exact human form he would take was not clear.

One perennially popular idea was that the savior would appear as an American (perhaps Franklin D. Roosevelt, perhaps a black GI). This was because the island was under British and French control—movements of deification provoked by colonial injustice often sought to access the power of their tormentors’ rivals or enemies. In 1964 the Lavongai people of the occupied Papua and New Guinea territory sabotaged the elections organized by their colonial masters by writing in the name of President Lyndon B. Johnson, electing him as their king and then refusing to pay taxes to their Australian oppressors. On similar grounds, midcentury Indian and African religious sects sometimes deployed avatars of Britain’s enemies—in India, Hitler was seen as the final coming of Vishnu, while Nigerians worshiped “Germany, Destroyer of Land”: My enemy’s enemy is my friend.

During World War I, indigenous populations in far-flung Allied colonies independently developed cults of Kaiser Wilhelm II, who, it was said, would shortly sweep away the English-speaking whites who had stolen their land and were exploiting their people. High above the Bay of Bengal, on the plateau of Chota Nagpur, tens of thousands of Oraon tea plantation workers gathered at clandestine midnight services and swore blood oaths to exterminate the British. They spoke of the Germans as “Suraj Baba” (Father Sun), passed around the emperor-god’s portrait, and sang hymns to his casting out of the British and establishing an independent Oraon raj:

German Baba is coming,

Is slowly slowly coming;

Drive away the devils:

Cast them adrift in the sea.

Suraj Baba is coming…

The salient point is not that such hopes were untethered from reality, but what they expressed. For what can the powerless do? To what can they appeal to restore the rightful order of things, in the face of endless loss? “Do you know that America kills all Negroes?” a Papuan skeptic challenged one of LBJ’s apostles in 1964. “You’re clever,” the apostle replied. “But you haven’t got a good way to save us.”

Around this time, the British colonizers of Tanna were indoctrinating its inhabitants in the goodness of their young queen Elizabeth II and her handsome consort—a man, they learned, who was not actually from Britain, or Greece, or anywhere in particular. As it happened, the legend of the volcano god told that one of his sons had taken on human form, traveled far, and married a powerful foreign woman. Prince Philip vacationed in the archipelago and participated in a pig-killing ritual to consecrate a local chief. He was the Duke of Edinburgh, and Tanna’s island group had once been called the New Hebrides. In 1974 one of the many local messianic factions realized that he must be their messiah.

It proved to be a match made in heaven, for the British monarchy itself, in the twilight of its authority, was ever more reliant on invented ritual and mythmaking. Once Buckingham Palace learned of the prince’s deification, it began to celebrate and publicize the story for its own purposes, deftly positioning it as evidence of the affection in which the royal family (and by inference the British) were supposedly held all across the former empire, and as a counterweight to the prince’s well-deserved domestic reputation as an unregenerate racist. This Western interest in turn produced an unceasing stream of international attention and visitors to Tanna, to investigate and report on the islanders’ strange “cult,” which not only helped to strengthen the myth’s local appeal but even influenced its shape.

In 2005 a BBC journalist arrived on the island to report the story, bringing with him a sheaf of documents compiled by the prince’s former private secretary, including official correspondence from the 1970s, press clippings, and other English descriptions of the islanders’ beliefs. His sharing of these papers, and his lengthy discussions with the locals, inadvertently seeded new myths, many of which, as Subin dryly notes, sounded “much like palace PR describing philanthropic activities in an underdeveloped land.” Myths stay alive by constantly adapting, encompassing, and feeding off one another. This was a classic case of mutual mythmaking: the deification of Prince Philip was produced in Buckingham Palace and Fleet Street, as well as in the South Pacific. To this day, white men from Europe and America keep turning up on Tanna, claiming to be fulfilling the prophecy of the returning god.

In Subin’s irresistible medley of history, anthropology, and exhilaratingly good writing, the most powerful stories are those of indigenous mythmaking as outright political revolt. For in many instances in which white men were turned into gods, the purpose was wholly subversive: not just to channel the strength of the colonial imperium for one’s own ends, but to grasp the colonizers’ power and turn it against them. In 1864 a Maori uprising led by the prophet Te Ua Haumene killed several British soldiers. The head of their captain, speared on a pole, became the rebels’ protective talisman against other white invaders and their divine conduit to the angel Gabriel. Just as they reinterpreted the Bible to mean that Maori land should be restored and the British driven out, so too they appropriated a colonist’s actual mouth and made it speak their truth.

Even more unsettlingly, across their newly conquered African territories, from the 1920s onward British, French, and Belgian administrators found themselves faced with a strange contagion of spirit possession, in which the locals took on the colonists’ identities. People would fall into a trance and then claim to be channeling the governor of the Red Sea or a white soldier, secretary, judge, or imperial administrator. They demanded pith helmets and libations of gin, marched around in undead formations, issued commands, and refused to obey imperial edicts, calling themselves Hauka, or “madness,” in the Sahel, and Zar in Ethiopia and the Sudan.

One version in the Congo claimed to have created deified duplicates of every single colonial Belgian. Each time an African adept joined the movement, he’d adopt the name of a particular colonist, and his wife that of the spouse. In this way, Hauka captured the entire colonial population, from the governor-general down to the lowliest clerk. On entering their trance state, the locals usurped the colonists’ power: the wives went around with chalked faces and wearing special dresses, screeching in shrill voices, demanding bananas and hens, clutching bunches of feathers under their arms in representation of handbags.

Precisely because spirit possession was unwilled and painful, this was a means of resistance that mechanisms of imperial power could not easily counter. Early on, a district commissioner in Niger named Major Horace Crocicchia decided to suppress it by force. He rounded up sixty of the leading Hauka mediums, brought them in chains to the capital, Niamey, and imprisoned them for three days and nights without food. Then he forced them to acknowledge that their spirits could not match his own power, taunting them that he was stronger and that the Hauka had disappeared. “Where are the Hauka?” he jeered repeatedly, beating one of them until she acknowledged that the spirits were gone.

It only made things worse. Almost immediately a new, extremely powerful specter joined the spirit pantheon. All across Niger, villagers were now possessed by the vengeful, violent avatar of Crocicchia himself—also known as Krosisya, Kommandan, Major Mugu, or the Wicked Major. Deification of this kind was a form of ritualized revolt, a defiance of imperialist power that not only mocked but appropriated its authority.

All this also explains why, toward the middle of the twentieth century, the rise of a powerful, proud, anti-imperialist black ruler at the heart of Africa was so intoxicating to people on the other side of the globe who had been dehumanized for centuries because of the color of their skin. For black people in the Babylonian captivity of the New World, Ethiopia had long been held up as Zion, the land of their future return. Even before its dashing new emperor was crowned in 1930, American and Jamaican prophecies had begun to foretell the coming of a black messiah. Rastafarianism became a religion for all who opposed white hegemony: to worship Haile Selassie as a living god was to reject colonial Christianity, racial hierarchy, and subordination, and to celebrate black power. No wonder its tenets have spread across the globe and attracted nearly a million followers. As Subin’s rich, captivating book shows, religion is a symbolic act: though we cannot control the circumstances, we all make our own gods, for our own reasons, all the time.

144 notes

·

View notes

Text

August 13 marks half a millennium since the fall of the Aztec Empire, and dozens of new books are casting doubt on the version of history written by the victors.

History is not only what happened, but what we are told happened.

Of course, that does not mean that history is subjective, because some facts are undeniable:

Hernán Cortés reached the shores of Veracruz, Mexico in 1519. But to understand the conquest of Mexico, we need to look at who was narrating it, as the angle or the sources they choose can tell us more about that moment than the facts themselves. “History is a consequence of power,” wrote Trouillot. “The most important task is not to determine what history is, but how it works.”

In the last two years, publishing houses in the country have produced dozens of new volumes questioning the credibility of the powerful storytellers who saw 1521 as a set victory of the Spanish over the Mesoamerican indigenous people. The full story of that battle, they say, was more complex.

“Every source is first and foremost a fact within its social, spatial and temporal context,” writes Luis Fernando Granados, a historian at Mexico’s Universidad Veracruzana, in his new book Relación de 1520 (or Record of 1520). He is critical of Hernán Cortés, considered the master storyteller of his time. In the book, Granados questions the credibility of the letters that the conquistador sent to the Spanish crown between 1519 and 1526, and that for centuries were taken as official accounts. Granados points out that there is no original manuscript from Cortés, but rather a transcription made years later by a scribe. There were letters written by several people, but these were political documents to the queen rather than a careful historical account. “If we stop considering them as the master version of Mexico’s past, that could have as refreshing an effect on the historiographical as on the purely historical,” he said. (Granados died in July of this year.)

One of the most interesting books on Cortés’ lack of credibility is entitled: ¿Quién conquistó México? (or Who Conquered Mexico?), by historian Federico Navarrete, and published by Debate books in 2019. This book poses different answers to the question of who conquered Mexico, and states: “The idea of the absolute victory of the Spaniards in 1521 is nothing more than a partial and self-serving version, invented by Hernán Cortés himself, to extol and exaggerate his own role in the events,” the book adds.

Another narrator whose words were taken as gospel was Bernal Díaz del Castillo, conquistador and author of La Historia verdadera de la conquista de la Nueva España (or The True History of the Conquest of Nueva España”), whom Mexican writer Carlos Fuentes called Mexico’s “first novelist.” In 2019, the Taurus publishing house translated into Spanish When Montezuma Met Cortés: The True Story of the Meeting that Changed History, a work by US historian Matthew Restall dissecting official narratives, which begins by casting doubt on Díaz del Castillo’s credibility regarding Aztecan emperor Moctezuma and Cortés. The Aztec leader was neither cowardly nor naive, and Hernán Cortés was not a brilliant Spanish strategist, the book asserts.

“We have abandoned the term conquest, in the singular, and instead prefer the term conquests plural, in order to emphasize that the defeat of [the capital of the Aztec Empire] Tenochtitlan was only the beginning of a historical step,” writes historian Martín Ríos Saloma of the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM). He has compiled essays by the best researchers in Mexico and Spain in his work Conquistas (or Conquests) released this year. His book makes an effort to search for the narrators whose past has been silenced, including “the voices of indigenous actors, of women, of the army captains, of the Castilian soldiers.” To ignore them, he believes, is to offer “a simplistic, Manichean and isolated vision of the historical processes happening in the world at that time.”

One of these silenced voices opens El quinto sol (or The Fifth Sun) by Camilla Townsend, translated into Spanish by the Grano de Sal publishing house this year. Chimalpahin, an indigenous historian who worked in a church, wrote in the evenings during his spare time to try and save the memory of his ancestors. To revisit writings like his, set down a century after 1521, is to deconstruct false narratives, Townsend says, offering the example of the exaggerated myth of Aztec human sacrifice. “The Aztecs were conquered, but they also saved themselves,” the author notes, “by writing down everything they could remember of their peoples’ history so that it would not be lost forever.”

The list of new publications in this year of commemoration can seem endless. Mexican historian Pedro Salmerón rejects the term conquest in La batalla por Tenochtitlan (or The Battle for Tenochtitlan). “The war was much more prolonged, the resistance was far greater and long-lasting and, in fact, it has not ended,” he stresses. Enrique Semo, in La conquista, catástrofe de los pueblos originarios (or The Conquest, Catastrophe of the Original Peoples) is more interested in the history of a new capitalist system present in Mesoamerica than in the date of 1521 itself. “Instead of eliminating or displacing the indigenous people in order to make use of empty spaces, the imperative was to reduce them to manageable groups,” he says.

Novelists and graphic novelists have also done their part as the anniversary approaches. The Planeta group published several novels this year focused on women. Montezuma’s daughter features in La otra Isabel (or The Other Isabel) by Laura Martínez-Belli.

#mexico#history#mexican history#spain#indigenous#aztec#hernan cortes#montezuma#Tenochtitlan#🇲🇽#books

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

i’m so glad that being a latin americanist has required me to learn about pre-contact and colonial latin america because i absolutely love it and i am so happy that it technically falls under my area of expertise. i worked very hard to be a specialist on colonial latin america as well as being a modernist. while i’m nowhere near the expertise level of my peers who are specifically designated as colonialists, i worked hard reading a ton of books and getting tested on my proficiency on the subject so maybe one day i can teach it or write on it in the future. one of the things that fascinates me most is life in mesoamerica and the andes pre contact and immediately post contact. it is horrendous to wrap your mind around, but i find the moment of complete culture shock and slow realization at the point of contact (whether that be with cortes and moctezuma or pizarro and atahualpa) fascinating. the source base for this period of time is especially interesting - i loved reading the firsthand account by titu cusi yupanqui taken down by spanish notaries... i think that account of just complete shock and misunderstanding of the spaniards as gods or in the case of the aztecs perceiving cortes as the reincarnation of quetzalcoatl is so incredible to read.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ep 202: The Scrying Game

“The scryer does not seek reflections, but visions.”

– Donald Tyson, author of "Scrying for Beginners: Use Your Unconscious Mind to See Beyond the Senses

Description:

Who among us hasn't wanted to know the future or have insight into the hidden, at least in passing? From the first instance a human had a premonition that came true, it seems likely that the adventurous who were shocked and astounded wondered how those without the "gift" could duplicate this impossible experience. Then, when someone stared too intently into a reflective pool of liquid, a glowing ember, or even the night sky, and experienced an extrasensory perception, a technique and its medium are discovered to tap into a sixth sense. Practiced now for millennia, this procedure for obtaining occult information has become known as scrying. One interesting observation is that although there are general guidelines for preparing oneself and performing a scrying session, many mediums can facilitate the phenomenon. It appears that any object can be used that can capture the light and dazzle the eye, or a reflective surface that can offer deep introspection or a dark void that focuses the senses. But then the burning question becomes, how does this process work, and from where does the information come? Does this "second sight" materialize from deep within ourselves, external omniscience, or some combination of both? In tonight's episode, we'll look at the elements, the history, and the concepts behind this ancient and mysterious means of knowing the unknowable.

Reference Links:

Scrying on Wikipedia

The 1992 motion picture, The Crying Game

Samhain

Lori Williams’ Controlled Remote Viewing website IntuitiveSpecialists.com

Russell Targ

Crystal Gazing – Its History and Practice, with a Discussion of the Evidence for Telepathic Scrying, by Northcote W. Thomas, M.A.

Benjamin, from the Old Testament or “Hebrew Bible”

“The Forgotten Art of Scrying” by Fernando S. Gallegos on ExploringTraditions.com

Bernardino de Sahagún

Moctezuma II

Nostradamus

John Dee

Edward Kelley

“Notes on John Dee’s Aztec Mirror” by Ed Simon on NorthernRenaissance.org

Horace Walpole

“Making a Sigilum Dei Aemeth out of Wax [Esoteric Saturdays]” on YouTube

Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn

Thelema

“Joseph Smith's "Magic" Glasses and Other Bizarre Objects from Mormonism” on ranker.com

Related Books:

SPECIAL OFFERS FROM OUR SPECIAL SPONSORS:

FIND OTHER GREAT DEALS FROM OUR SHOW’S SPONSORS BY CLICKING HERE!

SimpliSafe – Every night, local police departments across America receive hundreds of calls from burglar alarms. The vast majority of the time, they have no idea whether the alarm is real – Is there really a crime going on or not? All the alarm company can tell them is “the motion sensor went off.” SimpliSafe Home Security is different. If there’s a break-in, SimpliSafe uses real, video evidence, to give police an eye-witness account of the crime. That means police dispatch up to 350% faster than for a normal burglar alarm. You get comprehensive protection for your entire home. Outdoor cameras and doorbells alert you to anyone approaching your home. Entry, motion, and glass break sensors guard inside. Plus, SimpliSafe protects your home from fires, water damage, and carbon monoxide poisoning. It’s 24/7 monitoring by live security professionals. You can set up your system yourself, no tools needed – or SimpliSafe can do it for you. All this starts at just $15 a month, with no contracts, no pushy sales guys, no hidden fees, and no fine print! The Verge calls SimpliSafe “the best home security,” it’s a two-time winner of CNET’s “Editor’s Choice,” it’s won “Reader’s Choice” from PC Magazine and it’s a Wirecutter top pick. Right now, our listeners can get a FREE HD home security camera when they purchase a SimpliSafe system at SimpliSafe.com/AL. You’ll also get a 60-day Risk-Free Trial so there’s nothing to lose! Order now from SimpliSafe.com/AL and within a week you’ll give your home and family the protection and peace of mind they deserve, plus a FREE HD CAMERA!

Squarespace – Have something you need to sell or share with the world but don't have a website? Or maybe that old website of yours could use a serious style and functionality update but you don't think you have the time or money to pay someone to do it? Well, now you can do it yourself, stylishly and cost-effectively in very little time with Squarespace! With their large gallery of beautifully designed templates, eCommerce functionality, built-in Search Engine Optimization, free and secure hosting, and award-winning 24/7 Customer Support to guide you along the way, you'll be up and running on the Web in no time, with flair, ease and a choice of over 200 URL extensions to make you stand out! So what are you waiting for? Go to Squarespace.com/LEGENDS for a free trial and when you’re ready to launch, use the Offer Code "LEGENDS" to save 10% off your first purchase of a website or domain.

The Great Courses Plus – There are so many benefits to lifelong learning, which is why we love The Great Courses Plus! Learn about virtually anything, now with over 11,000 lectures on almost any subject you can think of – from history and science to learning a new language, how to play an instrument, learn magic tricks, train your dog, or explore topics like food, the arts, travel, business, and self-improvement. And all taught by world-leading professors and experts in their field. Their app lets you download and listen to only the audio from the courses or watch the videos, just like a podcast. Switch between all your devices and pick up right where you left off. Available for iOS and Android. So what is your purpose this year? What new things will you learn? Sign up for The Great Courses Plus and find out! And RIGHT NOW, our listeners can get this exclusive offer: A FREE TRIAL, PLUS get $30 OFF when you sign up for an annual plan! That comes out to just $10 a month! But this limited-time offer won’t last long, and it’s only available through our special URL and you don’t want to pass this up, so go NOW to: TheGreatCoursesPlus.com/LEGENDS

Purple – Throw some bedding on a bunch of different mattresses and sure, they all look alike. The same goes for pillows. But peel away the layers, look at what’s inside, and you’ll see they aren’t all created equal. And that’s what makes every Purple pillow and mattress, unlike anything you’ve ever slept on! “The Purple Grid” sets the Purple mattress apart from every other mattress. It’s a patented comfort technology that instantly adapts to your body’s natural shape and sleep style. With over 1,800 open-air channels designed to neutralize body heat, Purple provides a cooling effect other mattresses can’t replicate. And this cutting-edge technology doesn’t stop with the mattresses. Every Purple Pillow is engineered with The Grid for total head and neck support and absolute airflow, so you’re always on the cool side of the pillow. Purple’s proprietary technology has been innovating comfort for over 15 years. And now you can try every Purple product risk-free with FREE SHIPPING and returns. And Purple has financing available as low as 0% APR for qualified customers! Experience The Purple Grid and you’ll sleep like never before! Go to purple.com/AL10 and use promo code AL10. For a limited time, you’ll get 10% OFF any order of $200 or more! Terms apply.

Mint Mobile – After the year we’ve all been through, saving money should be at the top of everyone’s resolution list… So if you’re still paying insane amounts of money every month for wireless, what are you doing? Switching to Mint Mobile is the easiest way to save this year. As the first company to sell premium wireless service online-only, Mint Mobile lets you maximize your savings with plans starting at JUST $15 a month. By going online-only and eliminating the traditional costs of retail, Mint Mobile passes significant savings on to YOU. All plans come with unlimited talk and text + high-speed data delivered on the nation’s largest 5G network. Use your own phone with any Mint Mobile plan and keep your same phone number along with all your existing contacts. And if you’re not 100% satisfied, Mint Mobile has you covered with their 7-day money-back guarantee. To get your new wireless plan for just $15 bucks a month, and get the plan shipped to your door for FREE, go to MintMobile.com/AL !

Credits:

Episode 202: The Scrying Game. Produced by Scott Philbrook & Forrest Burgess; Audio Editing by Sarah Vorhees Wendel. Sound Design by Ryan McCullough; Tess Pfeifle, Producer, and Lead Researcher; Research Support from the astonishing League of Astonishing Researchers, a.k.a. The Astonishing Research Corps, or "A.R.C." for short. Copyright 2021 Astonishing Legends Productions, LLC. All Rights Reserved.

#202#2021#scrying#Nostradamus#John Dee#crystal ball#asphaltum#Snow White#Magic Mirror#Bloody Mary#Candyman#obsidian#mirror#magic mirror#fortune telling#tarot#palm reading#psychic#medium#future#predict

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

and this faith is gettin' heavy (but you know it carries me) redux

This is literally and unironically the SECOND TIME i have added another thousand words to this fic but now it is finally done. Behold, over 10k words of food as metaphor for love/angst-with-a-happy-ending! In which Teomitl goes missing on a foreign battlefield, and Acatl mourns...but events in his dreams suggest Teomitl maybe isn’t gone for good.

Also on AO3

-

Acatl grimaced as he stepped from the coolness of his home into the day’s bright, punishing sunlight. Today was the day the army was due to return from their campaign in Mixtec lands, and so he was forced to don his skull mask and owl-trimmed cloak on a day that was far too hot for it. Not for the first time, he was thankful that priests of Lord Death weren’t required to paint their faces and bodies for special occasions; the thought of anything else touching his skin made him shudder.

He’d barely made it out of his courtyard when Acamapichtli strode up to him, face grave underneath his blue and black paint. “Ah, Acatl. I’m glad I could catch you.”

“Come to tell me that the army is at our gates again?” They would never be friends, he and Acamapichtli, but they had achieved something like a truce in the year since the plague. Still, Acatl couldn’t help but be on his guard. There was something...off about the expression on the other man’s face, and it took him a moment to realize what it was. He’d borne the same look when delivering the news of a death to a grieving family. Ah. A loss, then.

He’d expected Acamapichtli to spread his hands, a wordless statement of there having been nothing he could have done. He didn’t expect him to take a deep breath and slide his sightless eyes away. “I have. The runners all say it is a great victory; Tizoc-tzin has brought back several hundred prisoners.”

It should have pleased him. Instead, a cold chill slid down his spine. “What are you not telling me? I’ve no time for games.”

Acamapichtli let out a long sigh. “There were losses. A flood swept across the plain, carrying away several of our best warriors. Among them...the Master of the House of Darts. They looked—I’m assured that they looked!—but his body was not found.”

No. No. No. A yawning chasm cracked open beneath his ribs. He knew he was still breathing, but he couldn’t feel the air in his lungs. Even as he wanted, desperately, to grab Acamapichtli by the shoulders and shake him, to scream at him for being a liar, he knew the man was telling the truth. That his face and mannerisms, the careful movements of a man who knew he brought horrible news, showed his words to be honest. That Teomitl—who had left four months before with a kiss for Mihmatini and an affectionate clasp for Acatl’s arm—would not return.

It took real effort to focus on Acamapichtli’s next words. The man’s eyes were full of a horrible sympathy, and he wanted to scream. “I thought you should know in advance. Before—before they arrived.”

“Thank you,” he forced out through numb lips.

Acamapichtli turned away. “...I’m sorry, Acatl.”

After a long, long moment, he made himself start walking again. There was the rest of the army to greet, after all. Even if Teomitl wouldn’t be among them.

Even if he’d never return from war again.

Greeting the army was a ceremony, one he usually took some joy in—it had meant that Teomitl would be home, would be safe, and his sister would be happy. Now it passed in a blue, and he registered absolutely none of it. Someone must have already given the news to Mihmatini when he arrived; she was an utterly silent presence at his side, face pale and lips thin. She wouldn’t cry in public, but he saw the way her eyes glimmered when she blinked. He couldn’t bring himself to so much as lay a sympathetic hand on her shoulder. If he touched her, if he felt the fabric of her cloak beneath his hand, that meant it was real.

It couldn’t be real. Jade Skirt was Teomitl’s patron goddess, She wouldn’t let him simply drown. But there was an empty space to Tizoc’s left where Teomitl should have been, and no sign of his white-and-red regalia. Acatl’s eyes burned as he blinked away the sun.

Tizoc was still speaking, but Acatl heard none of his words. It was all too still, too quiet; everything was muffled, as though he was hearing it through water. If there was justice, came the first spinning thought, every wall would be crumbling. No...if there was justice, Teomitl would be...

He drew in a long breath, feeling chilled to the bone even as he sweated under his cloak. Now that his mind had chosen to rouse itself, its eye was relentless. He barely saw the plaza around him, packed with proud warriors and colorful nobles; it was too easy to imagine a far-flung province to the south, a jungle thick with trees and blood. A river bursting its banks, carrying Teomitl straight into his enemies’ arms. They would capture him, of course; he was a valiant fighter and he’d taken very well to the magic of living blood, but even he couldn’t hold off an army alone.

And once they had him, they would sacrifice him.

Somewhere behind the army, Acatl knew, were lines of captured warriors whose hearts would be removed to feed the Sun, whose bodies would be flung down the Temple steps to feed the beasts in the House of Animals, whose heads would hang on the skull-rack. It was necessary, and their deaths would serve a greater purpose. He’d seen it thousands of times. There was no use mourning them. It was simply the way nearly all captured warriors went.

It was what Teomitl would want. An honorable death on the sacrifice stone. It was better to die than to be a slave all your life. But at least he would have a life—all unbidden, the alternative rose clear in Acatl’s mind. Teomitl, face whitened with chalk. Teomitl, laying down on the stone. Teomitl, teeth clenched, meeting his death with open eyes. Teomitl’s blood on the priests’ hands.

Nausea rose hot and bitter in his throat, and he shut his eyes and focused on his breathing. In for a count of three, out for a count of five. Repeat. It didn’t hurt to breathe, but he felt as if it should. He felt as if everything should hurt. He felt a sudden, vicious urge to draw thorns through his earlobes until the pain erased all thoughts, but he made his hands still. If he started, he wasn’t sure if he would be able to stop.

Still, it seemed to take an eternity for the speeches and the dances to be over and done with. By the time they finished, he was light-headed with the strain of remaining upright, and Mihmatini had slipped a hand into his elbow. Even that single point of contact burned through his veins. They still hadn’t spoken. He wondered if she, too, couldn’t quite find her own voice under the screaming chasm of grief.

And then, after all that, when all he yearned for was to go home and lay down until the world felt right again—maybe until the Sixth Sun rose, that would probably be enough time—there was a banquet, and he was forced to attend.

Of course there’s a banquet, he thought dully. This is a victory, after all. Tizoc had wasted no time in promoting a new Master of the House of Darts to replace his fallen brother, with many empty platitudes about how Teomitl would surely be missed and how he’d not want them to linger in their grief, but to move on and keep earning glory for the Mexica. Moctezuma, his replacement, was seventeen and haughty; where Teomitl’s arrogance had begun to settle into firm, well-considered authority and the flames of his impatience had burnt down to embers, Moctezuma’s gaze swept the room and visibly dismissed everyone in it as not worth his concern. It reminded Acatl horribly of Quenami.

Mihmatini sat on the same mat she always did, but now there was a space beside her like a missing tooth. She still wore her hair in the twisted horn-braids of married women, and against all rules of mourning she had painted her face with the blue of the Duality. Underneath it, her face was set in an emotionless mask. She did not eat.

Neither did Acatl. He wasn’t sure he could stomach food. So instead his gaze flickered around the room, unable to settle, and he gradually realized that he and Mihmatini weren’t alone in the crowd. The assembled lords and warriors should have been celebrating, but there was a subdued air that hung over every stilted laugh and negligent bite of fine food. Neighbors avoided each other’s eyes; Neutemoc, sitting with his fellow Jaguar Warriors, was staring at his empty plate as though it held the secrets of the heavens. He looked well, until Acatl saw the expression on his face. It was a mirror of his own.

At least his fellow High Priests didn’t try to engage him in conversation, for which he was grateful. Acamapichtli kept glancing at him almost warily, but he hadn’t voiced any more empty platitudes—and when Quenami had opened his mouth to say something, he’d taken the unprecedented step of leaning around Acatl and glaring him into silence.

If they’d been friends, Acatl would have been touched; as it was, it made a burning ember of rage lodge itself in his throat. Don’t you pity me. Don’t you dare pity me. He ground his teeth until his jaw hurt, clenched his fists until his nails cut into his palms, and didn’t speak. If he spoke, he would scream.

Even the plates in front of him weren’t enough of a distraction. Roasted meats glistened in their vibrant red or green or orange sauces. Each breath brought the deliciously warm fragrance of chilies and pumpkin seeds and vanilla to his nose. The fish and lake shrimp, grilled in their own juices and arrayed on beds of corn husks, would at any other time have tempted him to take a bite. Soups and stews were carried from table to table by serving women in gleaming white cotton; he breathed in as one woman passed and nearly choked on the rich peppery scent. He didn’t need to look to know it was his usual favorite, chunks of firm white fish and bitter greens in what was sure to be a fiery broth. Teomitl had always teased him for that, saying it was a miracle he could even taste the greens with so much chili in the way.

Don’t look. Don’t think about it. The ember in his throat was slowly scorching a path through his gut. He couldn’t eat. Didn’t even try.

There were more courses, obviously. More fish, more vegetables, more haunches of venison or rabbits bathed in spicy-sweet sauce. More doves and quail, and even a spoonbill put back in its own pink feathers for a centerpiece. When the final course was triumphantly set in front of him—wedges and cubes of fruit, with a little cup of spiced honey—he was nearly sick over the sweet crimson pitaya split open on his plate. It had been Teomitl’s favorite.

Somehow, he held it together until after the dessert had been cleared away. He rose jerkily to his feet, legs trembling, and fixed his mind firmly on getting home in one piece. No one hailed him on his way out of the room, and for a hopeful moment he thought he was safe.

Quenami’s voice stopped him in the next hallway. “Ah, Acatl. A lovely banquet, wasn’t it?”

He didn’t turn around. “Mn.” Go away.

Quenami didn’t. In fact he took a step closer, as though they were friends, as though he’d never tried to have Acatl killed. His voice was like a mosquito in his ear. “You must not be feeling well; you hardly touched your food. Some might see that as an insult. I’m sure Tizoc-tzin would.”

“Mm.”

“Or is it worry over Teomitl that’s affecting you? You shouldn’t fret so, Acatl. You know, I wouldn’t be surprised if he’s not dead after all; there are plenty of cenotes in the southlands, and a determined man could easily hide out there for the rest of his life. He probably just took the coward’s way out, sick of his responsibilities—“

He whirled around, sucking in a breath that scorched his lungs. It was the last thing he felt before he let Mictlan’s chill spill through his veins and overflow. His suddenly-numb skin loosened on his neck; his fingers burned with the cold that came only from the underworld. He knew that his skin was black glass, his muscles smoke, his bones moonlight on ice, his eyes burning voids. All around him was the howling lament of the dead, the stench of decay and the dry, acrid scent of dust and dry bones. When he spoke, his voice echoed like a bell rung in a tomb.

“Silence.”

You do not call him a coward. You do not even speak his name. I could have your tongue for that. He stepped forward, gaze locked with Quenami’s. It would be easy, too. He could do it without even blinking—could take his tongue for slander, his eyes for that sneering gaze, could reach inside his skin and debone him like a turkey—all it would take would be a single wrong word—

Quenami recoiled, jaw going slack in terror. Silently—blessedly, mercifully, infuriatingly silently—he turned on his heel and left.

Acatl took one breath, two, and let the magic drain out of his shaking limbs. He hadn’t meant to do that. It should probably have sickened him that he’d nearly misused Lord Death’s power like that, especially on a man who ought to have been his superior and ally, but instead all he felt was a vicious sort of stymied rage—a jaguar missing a leap and coming up with nothing but air between his claws. He wanted to scream. He wanted blood under his nails, the shifting crack of breaking bones under his knuckles. He wanted to hurt something.

He made it to the next courtyard, blessedly empty of party guests, and collapsed on the nearest bench like a dead man. His stomach ached. I could have killed him. Gods, I wanted to kill him. I don’t think I’ve ever been so angry in my life. All because...all because he said his name...

“...Acatl?”

Mihmatini’s voice, admirably controlled. He made himself lift his head and answer. “In here.”

She padded into the courtyard and took a seat on the opposite end of the bench, skirt swishing around her feet as she walked. Gold ornaments had been sewn into its hem, and he wondered if they’d been gifts from Teomitl. “I saw Quenami running like all the beasts of the underworld were on his tail. What did you do?”

Nothing. But that would have been a lie, and he refused to do that to his own flesh and blood. “...He said…” He swallowed past a lump in his throat. “He said that Teomitl might have deserted. He dared to say that—” The idea choked him, and he couldn’t finish the words. That Teomitl was a coward. That he would run from his responsibilities, from his destiny, at the first opportunity…

She tensed immediately, eyes going cold in a way that suggested Quenami had better be a very fast runner indeed. “He would never. You know that.”

Air seemed to be coming a bit easier now. “I do. But…”

Of course, she pounced on his hesitation. “But?”

I want him so badly to not be dead. “Nothing.”

Mihmatini was silent for a while, wringing her hands together. Finally, she spoke. “He would never have deserted. But...Acatl…”

“What?”

“I don’t know if he’s dead.” She set a hand on her chest. “The magic that connects us—I can still feel it in here. It’s faint, really faint, but it’s there. He might…” She took a breath, and tears welled up in her eyes. “He might still be alive.”

Alive. The word was a conch shell in his head, sounding to wake the dawn. For an instant, he let himself imagine it. Teomitl alive, maybe in hiding, maybe trying to find his way home to them.

Maybe held captive by the Mixteca, until such time as they can tear out his heart. He closed his eyes, shutting out everything but the sound of his own breathing. It didn’t help. He hated how pathetic his own voice sounded as he asked, “You think so?”

“It’s—” She scrubbed ineffectually at her eyes with the back of a hand. “It’s possible. Isn’t it?”

“...I suppose.” He took a breath. “I think it’s time for me to get some sleep. I’ll...see you tomorrow.”

He knew he wouldn’t sleep—knew, in fact, that he’d be lucky if he even managed to close his eyes—but he needed to get home. He refused to disgrace himself by weeping in public.

&

The first dream came a week later.

He’d managed to avoid them until then; he’d thrown himself headlong into his work, not stopping until he was so tired that his “sleep” was really more like “passing out.” But it seemed his body could adapt to the conditions he subjected it to much easier than he’d thought, because he woke with tears on his face and the scraps of a nightmare scattering in the dawn light. There had been blood and screaming and a ravaged and horrible face staring into his that somehow he’d known. He did his best to put it from his mind, and for a day he thought he’d succeeded. He shed blood for the gods, stood vigil for the dead, tallied up the ledgers for the living. Remembered, occasionally, to put food into his mouth, but he couldn’t have said what he was eating. Collapsed onto his mat and prayed that he wouldn’t have a dream like that again.

It wasn’t like that. It was worse.

He was walking through a jungle made of shadows, trees shedding gray dust from their leaves as he passed under them. There was no birdsong, no rippling of distant waters or crunching of underbrush, and he knew deep in his soul that nothing was alive here anymore. Not even himself. Though his legs ached and his lungs burned, it was pain that felt like it was happening to someone else. His gut held, not the stretched desiccation of Mictlan, but a nasty twisting feeling of wrongness; part of him wanted to be sick, but he couldn’t stop. Ahead of him, someone was making their way through the undergrowth, and it was a stride he’d know anywhere.

Teomitl. He thought he called out to him, but no sound escaped his mouth even though his throat hurt as though he’d been screaming. He tried again. Teomitl! This time, he managed a tiny squeak, something even an owl wouldn’t have heard.

Teomitl didn’t slow down, but somehow the distance between them shortened. Now Acatl could make out the tattered remains of his feather suit, singed and bloodstained until it was more red than white, and the way his bare feet had been cut to ribbons. He still wasn’t looking behind him. It was like Acatl wasn’t there at all. Ahead of them, the trees were thinning out.

And then they were on a flat plain strewn with corpses, bright crimson blood the only color Acatl could see. Teomitl was standing still in front of him as water slowly seeped out of the ground, covering his feet and lapping gently at his ankles. There were thin threads of red in it.

“Teomitl,” he said, and this time his voice obeyed him.

Teomitl turned to him, smiling as though he’d just noticed he was there. His chest was a red ruin, the bones of his ribcage snapped wide open to pull out his beating heart. A tiny ahuizotl curled in the space where it had been.

He took one step back. Another.

Teomitl’s smile grew sad, and he reached for him with a bloody hand. “Acatl, I’m sorry.”

He awoke suddenly and all at once, curling in on himself with a ragged sob. It was still dark out; the sun hadn’t made its appearance yet. There was no one to see when he shook himself to pieces around the space in his heart. It was a dream, he told himself sternly. Just a dream. My soul is only wandering through my own grief. It doesn’t mean anything.

But then it returned the next night, and the next. While the details differed—sometimes Teomitl was swimming a river that suddenly turned to blood and dissolved his flesh, sometimes one of his own ahuizotls turned into a jaguar and sprang for his face—the end was always the same. Teomitl dead and still walking, reaching for him with an apology on his lips. Sometimes it even lingered after he woke. Once he jolted awake utterly convinced that he wasn’t alone—that Teomitl was in the room, a sad smile on his lips and an outstretched hand hovering in the air. Only when he looked around, searching for that other presence, did reality reassert itself and he remembered with gutwrenching pain that it had only been a nightmare. That Teomitl was dead somewhere on a Mixtec altar, his heart an offering to the Sun.

He started timing his treks across the Sacred Precinct to avoid the Great Temple’s sacrifices to Huitzilopochtli. Sleep grew more and more difficult to achieve, and even when he caught a few hours’ rest it never seemed to help. He even thought, fleetingly, of asking the priests of Patecatl if anything they had would be useful, only to dismiss it the next day. He would survive this. It wasn’t worth baring his soul to anyone else’s prying eyes or clumsy but well-meaning words. He would work and pray, and that would keep him occupied. There was a haunting case that needed his attention; while he was tracking down the cause he had an excuse not to focus on anything else. He forgot to eat, no matter how much Ichtaca scolded him. The food tasted like ashes in his mouth, anyway.

Still, when one of Neutemoc’s slaves came to his door asking whether he would come to dinner at his house that night, he didn’t waste time in accepting. Dinner with Neutemoc’s family had become...normal. He needed normal, even if it still felt like walking on broken glass.

Up until the first course was served, he even thought he’d get it. Neutemoc had been nearly silent when he’d arrived, but he’d unbent enough to start a conversation about his daughters’ studies. Necalli and Mazatl were more subdued than they normally were, but they’d heard what happened to their newest uncle-by-marriage and were no doubt mourning in their own ways. Mihmatini’s face was as pale and set as white jade, but as the conversation wore on he thought he saw her smile.

He didn’t much feel like smiling himself. The smells of the meal were turning his stomach. It was simple enough fare—fish with peppers, lightly boiled vegetables in a salty, spicy sauce, plenty of soft flatbread to mop it up—but he couldn’t bring himself to touch it. The last time he’d eaten a meal like this had been with Teomitl at his side, hugging Mazatl and fondly ruffling up Necalli’s hair and barely paying any attention to his own plate until Mazatl had swiped something off it and he’d tickled her as revenge, the both of them laughing. Acatl would never forget the look on his face the first time she’d called him uncle.

He was vaguely aware Neutemoc was frowning at him. “Eat. Before it gets cold.”

He put some fish onto his plate. He ate it. He couldn’t say what it tasted like. Peppers, mostly. It sat in his stomach like a lead weight, and he swallowed so roughly that for a moment he was afraid he’d choke. I can’t do this. But they would notice if he didn’t eat, and then they’d worry about him. He forced himself to take a few more bites, filling the yawning void within.

A second course arrived eventually. Roasted agave worms and greens, which he usually liked. He took a small portion, nibbled on it, and set his plate down.

“More greens?”

Neutemoc’s voice was too careful for his liking, but he nodded. Another portion of greens was duly set onto his plate, and he ate without really tasting it. He only managed a few bites before he had to give up, his gorge rising.

Mihmatini picked at her own dish, and Neutemoc frowned at her. “You’re not hungry?”

She shook her head.

Silence descended again, but It didn’t reign for long before Neutemoc said, “Acatl. Any interesting cases lately?” With a quick glance at his children, he added, “That we can talk about in front of the kids?”

“Aww, Dad...”

Neutemoc gave his eldest the same look his father had once given him. “When you go off to war, Necalli, I will let you listen to all the awful details.”

It wasn’t enough to make Acatl smile, but nevertheless the tension in his throat eased. “Well,” he began, “we’ve been trying to figure out what’s been strangling merchants in the featherworkers’ district…”

Laying out the facts of a suspicious death or two was always calming. He could forget the ache in his heart, even if only briefly. But even when he was done and had just started to relax, Neutemoc was still talking to him as though he expected to see his younger brother shatter any minute. The slaves, too, were unusually solicitous of him—rushing to fill up his cup, to heap delicacies on his plate. At any other time he might have suspected the whole thing to be a bribe or an awkward apology for some unremembered slight; now, he just felt uneasy.

When the meal was done, he declined Neutemoc’s offer of a pipe and got to his feet. “I think I’ll get some air.”

The courtyard outside was empty. He lifted his eyes to the heavens, charting the path of the four hundred stars above. Ceyaxochitl’s death hadn’t hit him anywhere near as hard as this, but gods, he thought he could recover in time if only the people around him stopped coddling him. Everywhere he went there were sympathetic glances and soft words, and even the priests of his own temple were stepping gingerly around him. As though he needed to be treated like...like...

Like a new widow. Like Mihmatini. He sat down hard, feeling like his legs had been cut out from under him. Air seemed to be in short supply, and the gulf in his chest yawned wide.

But I’m not. I care for Teomitl, of course, but it’s not like that. It’s not—

He thought about Teomitl sacrificed as a war captive or drowned in a river far from home, and nearly choked at the fist of grief that tightened around his heart. No. He shook his head as though that would clear it. He wouldn’t want me to grieve over him. He wouldn’t want me to think of him dead, drowned, sacrificed—he’d want me to remember him happy. I can do that much for him, at least.

He could. It was easy. He closed his eyes and remembered.

Remembered the smile that lit up rooms and outshone the Sun, the one that could pull an answering burst of happiness out of the depths of his soul. Remembered the way Teomitl had laughed and rolled around the floor with Mazatl, the way he’d helped Ollin to walk holding onto his hands, the way he sparred with Necalli and asked about Ohtli’s lessons in the calmecac, and how all of those moment strung together like pearls on a string into something that made Acatl’s heart warm as well. Remembered impatient haggling in the marketplace, haphazard rowing on the lake, strong arms flexing such that he couldn’t look away, the touch of a warm hand lingering even after Teomitl had withdrawn—

He remembered how it had felt, in that space between dreams and waking, where he’d thought Teomitl was by his side even in Mictlan. Where, for the span of a heartbeat, he’d been happy.

There was a sound—a soft, miserable whine. It took him a moment to realize it was coming from his own throat, that he’d drawn his knees up to his chest and buried his face in them. That he was shaking again, and had been for some time. As nausea oozed up in his throat, he regretted having eaten.

It was like that, after all.

And he’d realized too late. Even if he’d ever been able to do anything about it—which he never would anyway, the man was married to his sister—there was no chance of it now, because Teomitl was gone.

He forced his burning eyes to stay open. If he blinked, if he let his eyes close even for an instant, the tears would fall.

Approaching footsteps made him raise his head. Mihmatini was walking quietly and carefully towards him, as though she didn’t want to disturb him. As though I’m fragile. You too, Mihmatini?

“Ah. There you are.” Even her voice was soft.