#Adolescent Psychiatry Services

Text

Adolescent Psychiatry Services : Mental Health Services

Adolescence is a critical period of development where individuals experience significant physical, emotional, and social changes. It is also a time when many mental health conditions emerge or worsen. Visit Now: www.accesshealthservices.org

#Adolescent Psychiatry Services#Mental Health Services#Adolescent Psychiatry Care#Access Health Services#Access Health Care Services#Psychiatric Clinic MD#Mental Health Clinic MD#MD Mental Health Services#Mental Health Clinic Baltimore MD#MD Mental Health Clinic#Psychiatrists in MD#Psychiatric Treatments in MD

0 notes

Text

STEPS Center for Mental Health provides specialized care for adults and children with top-rated psychiatrists. Get the help you need.

#Psychiatry and Therapy Services#Child and Adolescent Psychiatrist#Mental Health for Teenagers#Young Adult Mental Health Clinic

1 note

·

View note

Text

By: Christina Buttons

Published: May 13, 2024

A guide to the international debate on youth medical transition, where medical authorities in the United States depart from a growing international consensus.

The world is reacting to the U.K.'s Cass Review and associated systematic evidence reviews, which found "remarkably weak" evidence supporting medical interventions for gender transition in minors. Released on April 9, 2024, the final report from the national gender clinic service for those under 18—following four years of meta-analyses of the available literature—dealt a major blow to the gender-affirming model of care and marked its termination in England.

NHS England, which commissioned the report, expressed gratitude to Dr. Hilary Cass and committed to implementing her recommendations. These advocate for primarily relying on psychotherapy to address gender-related distress in minors and discontinuing the use of puberty blockers as part of England’s publicly funded healthcare system. The NHS predicted the landmark review would have "major international importance and significance"—a prediction that has proven correct. Just one month later, we are already beginning to see its impact.

What’s New

Scotland and Wales

In response to the Cass Review, Wales and Scotland have joined England in halting new prescriptions of puberty blockers for minors under 18 diagnosed with gender dysphoria. Additionally, in Scotland, cross-sex hormones will not be available to those under 18. In the last few years, beyond the U.K., Sweden, Finland, and Denmark have adopted a more cautious approach by placing restrictions on medical interventions for the treatment of gender dysphoria in minors. Norway has also signaled intentions to follow a similar path.

Germany

Now, Germany has emerged as the latest country to initiate steps towards placing restrictions on gender transition treatments for minors. Earlier this week, the German Medical Assembly, a pivotal body representing medical professionals across the country, passed a resolution that calls for the restriction of puberty blockers, cross-sex hormones, and surgeries for gender dysphoric youth to strictly controlled research settings. Another resolution passed that stated minors should not be permitted to "self-identify" into a chosen sex without first undergoing a specialist child and adolescent psychiatric evaluation and consultation.

While national restrictions have not yet been formalized, experts in gender medicine research are describing this update as a “major development” — especially considering that Germany has been one of the most permissive countries on this issue.

Read the SEGM Analysis

Belgium

Additionally, in Belgium, leading physicians are advocating for significant reforms in the treatment protocols for gender dysphoria in children and adolescents. According to an April 2024 report authored by pediatricians and psychiatrists P. Vankrunkelsven, K. Casteels, and J. De Vleminck from Leuven, there is a pressing need to follow the precedents set by Sweden and Finland, where hormones are regarded as a last resort. Their findings and recommendations were published in a prestigious medical journal associated with Dutch-speaking medical faculties in Belgium and their alumni associations.

International Bodies

International bodies such as the United Nations (UN) have also responded to the Cass Review. The United Nations Special Rapporteur on violence against women and girls, Reem Alsalem, issued a statement on the UN’s website declaring that the Review’s recommendations are essential for protecting children, especially girls, from harm.

In addition, the European Society of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (ESCAP), a prominent umbrella association of 36 Child and Adolescent Psychiatry societies worldwide, recently issued a policy statement on child and adolescent gender dysphoria. They urged healthcare providers to "not to promote experimental and unnecessarily invasive treatments with unproven psycho-social effects and, therefore, to adhere to the ‘primum-nil-nocere’ (first, do no harm) principle."

These responses stand in stark contrast to that of World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH), a body-modification advocacy organization. WPATH emailed a statement to its subscribers in response to the Cass Review, vehemently rejecting its findings and adhering to its ideological beliefs. WPATH criticized the Cass Report as “harmful” and "rooted in a false premise" that suggests distressed children can be helped without "medical pathways.”

United States

In response to the Cass Review, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and the Endocrine Society (ES) recently provided statements to WBUR, doubling down on their endorsement of the gender-affirming model of care and medical interventions for minors. Both blamed “politics” for spreading “misinformation.” Meanwhile, prominent gender clinicians have expressed to WBUR that they are “perplexed and concerned” by these organizations’ statements, given the Cass Review’s findings.

WPATH, AAP, and ES continue to mislead the public by claiming that the gender-affirming model of care adheres to the principles of evidence-based medicine (EBM), despite clear evidence to the contrary. Their recommendations for medical interventions are not grounded in robust evidence but rather rely on "circular referencing" of each other’s guidelines, effectively creating a citation cartel.

Comprehensive Overview of the International Debate On Youth Transition by Country

In recent years, there has been an ongoing debate about the best approach for treating gender-distressed youth, addressing the global increase in young people, primarily adolescent females, seeking services from gender clinics. Countries with pediatric gender clinic services have shown varied responses, ranging from highly medicalized treatment pathways to approaches that prioritize psychotherapy.

Nations such as the UK, Sweden, Finland, and Denmark have taken unified steps to heavily restrict medical transitions for minors, aligning their guidance with the results of systematic evidence reviews, with Norway similarly indicating moves in this direction. Elsewhere, medical and health authorities remain divided on best practices, although there are signs of some reevaluating their positions on the medical transition of minors. This guide will highlight significant updates and changes observed in these practices over recent years.

The Netherlands

In the Netherlands, the birthplace of the Dutch Protocol—the highly medicalized approach to treating youth with gender dysphoria—is facing increased scrutiny. As of 2023, there is a growing debate within medical, legal, and cultural realms about the practice of youth gender transitions.

On February 15, 2024, the Dutch Parliament ordered an investigation into the physical and mental health outcomes of children who have been prescribed puberty blockers. Despite these developments, the guidelines for treating gender dysphoria have not yet been updated.

In April 2024, Amsterdam UMC, the Dutch clinic that pioneered youth gender transition practices, issued a statement in response to the Cass Report. The clinic commended several elements of the report but expressed disagreement with its conclusion that the evidence supporting the use of puberty blockers is insufficient.

In May 2024, one of the Netherlands' national newspapers profiled the new policy statement from The European Society of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (ESCAP) that advocated for a non-medicalized approach to treating child and adolescent gender dysphoria.

Norway

In 2023, the Healthcare Investigation Board of Norway (Ukom) issued recommendations urging the Ministry of Health and Care to instruct the Directorate of Health to revise the national professional guideline for gender incongruence, drawing on systematic evidence reviews. Additionally, the Ukom report proposed classifying puberty blockers, as well as hormonal and surgical interventions for children and young people, as experimental treatments. This classification would subject these treatments to more stringent regulations regarding informed consent, eligibility, and outcome evaluation. However, Norway has not yet issued any explicit new guidelines following these recommendations.

Denmark

In July 2023, Ugeskrift for Læger, the journal of the Danish Medical Association, reported a significant shift in Denmark's approach to treating youth with gender dysphoria. Instead of receiving prescriptions for puberty blockers, hormones, or surgery, most young people referred to the centralized gender clinic now receive therapeutic counseling and support.

France

In 2022, the National Academy of Medicine in France advised exercising "the utmost medical caution" for the use of puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones for children and adolescents, citing the risk of regret. Despite this caution, the prescription of these treatments remains permissible at any age with parental authorization.

A 2023 poll by the Journal International de Médecine found 84% of healthcare professionals in France are in favor of a moratorium on the administration of hormonal treatments for trans-identified minors.

In March 2024, French senators released a 369-page report advocating for the cessation of cross-sex hormones and puberty blockers on minors. Based on the findings of this report, lawmakers have drafted a bill that is set to be debated on May 28, 2024.

Italy

In January 2023, the Italian Psychoanalytic Society (SPI) wrote a letter to Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni, expressing "great concern" over the "ongoing experimentation" with drugs designed to halt puberty in children and calling for a "rigorous scientific discussion."

In March 2024, the Vatican’s doctrine office, after five years of preparation, released a report approved by Pope Francis that declared gender-related surgeries to be "a grave violation of human dignity."

In April 2024, five Italian medical organizations released a joint position paper on managing adolescent gender dysphoria. This document, which extensively references WPATH, supports the medical transition of minors.

Sweden

In 2022, Sweden's National Board of Health and Welfare declared that the potential harms of puberty blockers and gender-affirming hormone treatments for individuals under 18 years of age surpass the possible benefits for this demographic. The board recommended that such treatments should primarily occur within a research setting to better assess their effects on gender dysphoria, mental health, and quality of life among young people. Additionally, it noted that hormone treatments could still be administered in exceptional circumstances.

In April 2023, a systematic review conducted by researchers from Karolinska Institutet, University of Gothenburg, Umeå University, and the Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Assessment of Social Services was published in Acta Paediatrica. This review assessed the existing evidence on hormonal treatment for individuals under 18 years old with gender dysphoria. The researchers concluded that such interventions “should be considered experimental treatment rather than standard procedure.”

Finland

Finland was the first Western country to conduct a systematic review of the evidence for youth gender transition, that led to a significant update of its guidelines in 2020. Observations from Finnish gender clinics showed that hormone treatments do not typically improve—and can worsen—the functioning of gender-dysphoric youth. In response, the country's Council for Choices in Health Care revised its guidelines to emphasize psychosocial support as the primary approach and restricted hormonal interventions to exceptional cases. These interventions are permitted before age 18 only if the individual's cross-sex identity is confirmed as permanent and causes severe dysphoria, the child fully understands the significance, benefits, and risks of the treatments, and there are no contraindications.

In October 2023, Dr. Riittakerttu Kaltiala, a leading Finnish gender clinician and researcher at Tampere University Hospital, wrote an op-ed in The Free Press, titled "Gender-Affirming Care Is Dangerous. I Know Because I Helped Pioneer It.” She highlighted concerns about the practice of pediatric medical transition in the U.S. and the lack of solid evidence supporting the efficacy of medical transition in reducing suicide rates among young people.

In February 2023, a landmark study from Finland revealed low suicide rates among trans-identified youth and found no evidence of benefits from gender reassignment. The study showed that, after accounting for psychiatric needs, there was no statistically significant evidence that gender-referred youth have higher suicide rates compared to the general population. The authors concluded that the risk of suicide related to transgender identity and/or gender dysphoria "may have been overestimated."

England

In January 2020, National Health Service (NHS) England formed a Policy Working Group (PWG) to conduct an assessment of the existing research on the use of puberty blockers and feminizing/masculinizing hormones in children and young people with gender dysphoria. This was aimed at shaping a policy stance on their continued application. The findings from these reviews were released in March 2021.

In February 2022, the interim report to the Cass Review was published, which had been commissioned by NHS England to evaluate the Gender Identity Development Service (GIDS) at the Tavistock and Portman NHS Foundation Trust, the UK's only national clinic for children and adolescents with gender dysphoria. The review highlighted significant concerns about the clinical decision-making framework, noting a lack of robust evidence and consensus on the most effective treatments.

In July 2022, NHS England announced it would close GIDS in Spring 2023, which was delayed until Spring 2024. Two new regional hubs opened in London and the north of England to move away from a single-service model.

In October 2022, the NHS England issued new draft guidance following their systematic evidence review, stating that there is "scarce and inconclusive evidence to support clinical decision-making" for minors with gender dysphoria, and for most who present before puberty, it will be a "transient phase" requiring psychological support rather than medical intervention.

In March 2024, NHS England announced that it would end the prescription of puberty blockers at gender clinics for children due to insufficient evidence regarding their safety and effectiveness. These treatments will now only be accessible through clinical research trials.

On April 9, 2024, the final 388-page report of the Cass Review was published, along with 9 studies (8 of which were systematic evidence reviews) by the University of York.

Ireland

In March 2023, HSE published a review of the interim Cass Report to assess Gender Identity Services for children and young people in Ireland.

In April 2024, the Health Service Executive (HSE) announced the development of a new clinical program for gender healthcare, scheduled over the next two years. They also stated that the final report for the Cass Review will be included as part of this process.

Canada

In January 2024, Alberta announced the implementation of measures that significantly restrict medical transitions for minors. This policy establishes Alberta as the only province in Canada to enforce such limitations on gender transition procedures for individuals under 18. Under the new regulations, minors are prohibited from undergoing any gender-related surgeries, and those aged 16 and younger are prevented from accessing puberty blockers or cross-sex hormones.

United States

The three main organizations that have issued guidelines on youth medical transition include the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), the Endocrine Society (ES), and the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH). Other groups, such as the American Medical Association, have either publicly supported “affirming” medical practices without presenting evidence, or have aligned themselves with the guidelines set by one or more of these three organizations. Notably, none of these organizations have yet conducted systematic reviews of the evidence, which are designed to avoid selective inclusion of studies and biased interpretations.

Leaders at the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) ignored five resolutions from its members over four consecutive years, each urging that youth transition guidelines be aligned with findings from systematic evidence reviews. In August 2023, the AAP Board of Directors finally agreed to conduct their own systematic review of the evidence and consider updating its guidance. At the same time, the Board "voted to reaffirm" its 2018 policy statement on gender-affirming care.

In 2022, Florida took the lead as the first state to curtail the widespread administration of hormonal and surgical interventions to the increasing number of gender-dysphoric youth. Early in the year, Florida’s public health authority commissioned an overview of existing English-language systematic evidence reviews. Based on the findings from this review, the Florida Boards of Medicine subsequently decided to halt the provision of gender-transition services to minors, unless conducted within research settings across the state.

As of April 2024, 24 states have now placed age restrictions on hormonal and surgical sex-trait modification interventions for minors. Democrats in four states (Texas, Louisiana, New Hampshire, and Maine) have voted in favor of age restriction laws or against turning their states into hormone sanctuaries.

Spain

In 2018, the Spanish Association of Paediatrics and the Spanish Society of Paediatric Endocrinology published a statement endorsing youth medical transition.

In 2022, the directors of Spain’s Society of Psychiatry, Association of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, and Society of Endocrinology expressed their opposition to a proposed law that would enable minors to access medical transition procedures. El Mundo, the second-largest daily newspaper in Spain, highlighted this controversy on its front page with the headline: “Psychiatrists explode against the Trans Law: It can bring a lot of pain and regret to many people.”

Australia and New Zealand

In August 2021, The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists (RANZCP) issued its first position statement focused on the mental health needs of individuals with gender dysphoria, followed by an update in September 2021. This statement was the first from a professional body that did not explicitly endorse a gender-affirming approach.

Australia has experienced considerable debate in recent years regarding youth medical transition. This topic has been extensively covered by Australian journalist Bernard Lane for his Substack, Gender Clinic News.

New Zealand's Ministry of Health was expected to release an evidence brief in early 2024, aimed at reviewing the current evidence on the safety of puberty blockers. Although the publication has been delayed, it is anticipated to be released soon.

In April 2024, Guardian Australia reported that neither New South Wales or Victoria have plans to make changes to puberty blocker prescribing or accessibility as a result of the Cass Review.

International Bodies

In July 2023, for the first time, international experts publicly weighed in on the American debate over "gender-affirming care." 21 leading experts on pediatric gender medicine from eight countries wrote a letter expressing disagreement with US-based medical organizations over the treatment of gender dysphoria in youth, urging them to align their recommendations with unbiased evidence “rather than exaggerating the benefits and minimizing the risks.”

In January 2024, the World Health Organization (WHO) updated its announcement on developing healthcare guidelines for “trans and gender diverse (TGD) people.” The WHO stated in an FAQ that it would not be making recommendations that impact minors. Importantly, they made the following admission: "[O]n review, the evidence base for children and adolescents is limited and variable regarding the longer-term outcomes of gender affirming care for children and adolescents" (January, 2024).

Further Information

For additional information, one of the studies that contributed to the Cass Review conducted a survey of European gender services for children and adolescents from September 2022 to April 2023. Additionally, a Wikipedia page provides an overview of the "legal status of gender-affirming healthcare" (for adults) in various countries worldwide.

If you found this guide helpful, I am working on developing an information-based website that will feature up-to-date data, counterarguments to activist claims, explainers on research, and useful resources related to gender pseudoscience.

#Christina Buttons#systematic review#Cass report#Cass review#gender affirming care#gender affirming healthcare#gender affirmation#medical scandal#medical corruption#medical malpractice#head in the sand#willful ignorance

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dr. Riittakerttu Kaltiala, 58, is a Finnish-born and trained adolescent psychiatrist, the chief psychiatrist in the department of adolescent psychiatry at Finland’s Tampere University Hospital. She treats patients, teaches medical students, and conducts research in her field—publishing more than 230 scientific articles.

In 2011, Dr. Kaltiala was assigned a new responsibility. She was to oversee the establishment of a gender identity service for minors, making her among the first physicians in the world to head a clinic devoted to the treatment of gender-distressed young people. Since then, she has personally participated in the assessments of more than 500 such adolescents.

Earlier this year, The Free Press ran a whistleblower account by Jamie Reed, a former case manager at The Washington University Transgender Center at St. Louis Children’s Hospital. She recounted her growing alarm at the effects of treatments that sought to transition minors to the opposite sex, and her escalating conviction that patients were being harmed by their treatment.

Although a recent New York Times investigation largely corroborated Reed’s account, many activists and members of the media continue to dismiss Reed’s claims because she is not a physician.

Dr. Kaltiala is. And her concerns are likely to get more attention in the U.S. now that a young woman who medically transitioned as a teenager has just sued the doctors who supervised her treatment, along with the American Academy of Pediatrics. According to the suit, the AAP, in advocating for youth transition, has made “outright fraudulent statements” about evidence for “the radical new treatment model, and the known dangers and potential side effects of the medical interventions it advocates.”

Here, Dr. Kaltiala tells her own story, describing her increasing worries about the treatment she approved for vulnerable patients, and her decision to speak out.

20 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Editorial: Is autism overdiagnosed? (Eric Fombonne, The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 2023)

“That at least some of these community diagnoses are false positives was illustrated in one of our studies where, of 232 school-age children and adolescents with a pre-existing community diagnosis of ASD referred to our academic center for a neuroimaging study, only 47% met research criteria for ASD after an extensive diagnostic re-evaluation process (Duvall et al.,2022).

Yet, many were deemed to have been ‘meeting DSM criteria’ or ‘above the ADOS cut-off’ in prior records.

Overdiagnosis can result from shortcomings at either the diagnostic instrument or the diagnostic process levels.

With regard to diagnostic instrument, ADOS training workshops provide testers with a road map for organizing structured activities and social interactions designed to elicit diagnostically informative behaviors.

Techniques of test administration are straightforward to learn. However, scoring instructions are complex and necessitate a careful analysis and interpretation of the behaviors observed.

Even though the coding conventions are rigorously operationalized, a good deal of clinical judgment and experience remains necessary for the tester to accurately map observed behaviors to underlying autistic disturbances.

For example, children may talk repetitively about dinosaurs they saw during a recent museum visit which may be age-appropriate in young children; however, for this intense interest to be considered as excessive or ‘circumscribed’ requires that other features are demonstrated (odd quality, interference with demands, etc...).

Likewise, abnormal eye gaze is not specific to ASD and is observed across a number of other clinical conditions.

To count toward an ASD diagnosis, eye contact does not simply need to be absent or decreased but evidence of poor modulation in the dynamic context of a social interaction must be brought.

The issue is that many atypical behaviors that are linked to ASD are not specific to ASD.

Counting abnormal behaviors without establishing their specific autistic quality or nature is a source of overdiagnosis. (…)

For example, turn-taking in a conversation can be impaired in both ASD (Failure of normal back-and-forth conversation) and Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) (Often talks excessively, Blurts out answers).

Ascribing a symptom to either disorder requires a clinical analysis and judgment about the mechanism underlying conversation difficulty (pragmatic deficit? orimpulsivity?) that comes with experience in general psychopathology.

Overdiagnosing may also occur due to deficiencies in the overall diagnostic process and formulation.

As Bishop & Lord articulated, the diagnostic decision process must transcend the results of any particular tool, even if the administration of that test is considered to be a gold standard.

Combination of findings from different observations across contexts, informants, and data collection procedures (direct observation, caregiver report, school evaluations, medical records,...) must be performed.

Discrepancies between test results are common; there is no simple algorithmic solution to resolve them and expert clinical judgment is necessary to that end. (…)

Many would argue that the priority is to provide access to services for children presenting with neurodevelopmental disorders and that the consequences of underdiagnosis are far more deleterious than those due to overdiagnosis.

It may be so but that does not mean that erroneously diagnosing a child with ASD is harmless.

At the individual level, carrying an ASD diagnosis may unduly constrain one individual’s range of social and educational experiences and have long-lasting effects on his/her/their identity formation.

At a population level, the unjustified use of intensive services raises concerns about equity and fairness in services access for children who have neurodevelopmental disorders other than autism and struggle to access support services that they need as much as their peers with ASD.”

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

“At home” in Kisiizi, and encouraging developments

2nd March 2023

“At home” in Kisiizi, and encouraging developments

2nd March 2023

In one of our conversations at Kisiizi, Moses the hospital secretary reminded us that Kisiizi was our “second home”. Our welcome certainly suggested that we were part of the family. How lovely.

Georgious is the Psychiatric Clinical Officer who leads the mental health service at Kisiizi. His report was exciting as he told us of new developments and possibilities. And perhaps most importantly, we heard Georgious’s enthusiasm, leadership and vision.

The ward and patient shelter

mhGAP training, sponsored by JF, has proved to have had remarkable results.

When Covid struck, and senior mental health professionals couldn’t travel to the outlying clinics, the newly trained staff at the rural health centres carried on providing mental health treatment and support as they now know what to do.

A young clinician trained in mhGAP has been promoted to in-charge of the mental health ward.

Prima, who qualified in Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, was inspired to renew her adult mental health skills by mhGAP training.

On her way to school

Georgious is much more confident that if he has to be absent, the young team collaborate to share the responsibility of caring for the patients together. Georgious is in no doubt that mhGAP has made a significant difference. He says that staff are eager to apply their new knowledge and skills, and he can see the development in the way they work. His newly trained colleagues say they are not just wanting to pass exams as they were during their studies, they really want to use what they have learnt. And a good proportion of the mhGAP trainees have continued to practise their new skills.

Georgious has also led the workshops for Community Leaders’ Sensitisation. He says there is now clearly much better understanding of the nature of mental illness and epilepsy. The mental health team have a very good partnership with local teachers, and the police continue to refer potential patients.

Perhaps most excitingly, some of the pastors have really begun to change both their thinking and their practice. One pastor, for example, has identified 12 people who might have epilepsy or mental illness, brought them to the hospital, and stayed with them as they were assessed and started on treatment. He is now following them up and ensuring that the patients continue with their treatment.

This is a wonderful development, as the local church pastors are key people in their communities. Both we and Georgious are very hopeful that many more might follow this example.

If you have contributed to Jamie’s Fund in the last few years, your donation has helped to bring about all of this remarkable progress. Thank you so much for that.

Mobile phones get everywhere!

Georgious would like to expand the workshop programme to district level – he says that the district teams meet many patients and have the potential to be very supportive. Conversations with Kuule, who works at Bwindi hospital, have encouraged Georgious to make plans also to sensitise Village Health Volunteers – more key players in the life of village communities.

We were pleased that Dr Henry, the relatively new Medical Superintendent, was listening closely to Georgious’ report. Together with Moses we needed to have some discussion on matters less encouraging and more challenging. The team lost a patient to suicide recently, and this has provoked a renewed discussion on security, and their protocols on risk assessment and observation.

Another challenging issue is the number of patients who stay too long! Several patients have been left on the ward and abandoned by their families. In some cases they can’t even tell the team where they come from. In spite of best endeavours using community networks to try to trace the families, these have failed. The ward is left with these people who are technically no longer patients and have long been ready for discharge. Others are held until the families come to pay the fees due.

Kisiizi’s aim has always been “care for the vulnerable” and the management see this group of people as in that category. But the situation means that the mental health service has a big bill assigned to it, even when these individuals should not be there and aren’t a cost in terms of mentally illness. It is more a social work issue. This is a huge challenge. There is also an imbalance of unwell and well people, and too many extra beds down the middle of the wards.

We also talked of the Good Samaritan Fund, which provides for patients and families who cannot afford to pay for their psychiatric medicines. Georgious is of the view that if they could further expand community services and keep people well, patients would be less likely to relapse and need comparatively expensive medication. I think he is right.

When we were here last year we were struck by the negative impact of covid. It seemed to us that the whole country was depressed. This time it’s not so obvious, but there are still some concerns.

There is increased poverty, and fewer patients attending the hospital, resulting in a lower income. Patients not attending means they don’t get care from the team, and they probably don’t get medicine either, resulting in a higher number of patients relapsing.

There are psychosocial effects: increased rates of gender based violence, for example. Children have not been in school, and Georgious feels that many of them are losing hope. Some teachers took to alcohol during lockdowns. Higher pregnancy rates in girls and young women have negative results in many ways.

Families are less likely to afford medication because they have so little income; in addition, the drugs have became much more expensive, something we’ve seen around the world.

Kisiizi Hospital has, as always, tried to help the most vulnerable, and the School of Nursing has provided food for poorer patients where relatives cannot prepare meals for the inpatients.

The discussion took much of the morning. You remember that in a previous blog one of the sisters said they appreciated us coming because they felt loved. Moses commented that “when Ewan and Mo come it’s like an Annual General Meeting”!

But he also reminded us that “even if it’s a flying visit it’s important for us.” It’s important for JF too – we need to know that the funds you donate and we distribute are being put to the best use.

They are.

The vehicle bought by JF years ago with funds raised from a sponsored cycle. Still going well and 190,000 km on the clock.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Quel livre étrange !

Je ne connaissais pas du tout cette autrice américaine, accessoirement nonne zen (!), mais j’ai été attirée par cette sublime couverture (oui, c’est futile, mais ça joue), la mention du prix prestigieux obtenu et une critique élogieuse dans Télérama.

Me voilà donc partie pour presque 900 pages folles. Je ne regrette pas le voyage.

A travers les deux personnages principaux, Benny adolescent dévasté par la mort brutale de son père, et Annabelle, sa mère, devenue veuve et triste et seule, le roman aborde plein de thèmes importants avec énormément de romanesque et de liberté pour mener une narration à plusieurs voix, dont celle d’un livre, celui qui parle de et à Benny.

Ce roman interroge notre rapport au réel, et à ses représentants les plus prosaïques : les objets. Car Annabelle, dont le métier ne l’aide pas à lutter contre sa tendance, est une acheteuse compulsive, et une accumulatrice. Chez elle, elle se noie dans les objets, la paperasse, objets qui sont souvenirs, réconforts, mais aussi envahissants. Quant à Benny, il entend des voix venant des objets. Il en souffre énormément et commence à avoir des comportements qui l’envoient à l’hôpital, service psychiatrie pour enfants (au début du roman il a douze ans). Vous voyez, quelque chose se dessine… notre lien aux objets, notre équilibre mental, précaire. Benny fait des rencontres à l’hôpital et à la bibliothèque municipale, des rencontres cruciales qui vont l’aider à s’accepter, puisqu’un SDF va lui expliquer qu’entendre des voix peut-être l’apanage d’un poète. Une jeune fille perturbée va aussi lui prouver qu’il est intéressant, et lui assurer que ce n’est pas lui qui est fou mais le reste du monde, capitaliste, qui rejette ce qui est différent (on est à l’époque de l’élection de Trump). Annabelle reste longtemps seule à se débattre dans ses tracas domestiques, seulement accompagnée d’un petit livre écrit par une nonne zen (tiens, tiens) qui a écrit un best seller : La magie du rangement (j’ai pensé à Marie Kondo, je ne sais pas ce qu’en pense l’autrice, mais c’est impossible de ne pas faire le rapprochement). Enfin, heureusement, d’autres viendront l’aider.

Ce que j’ai retenu du message du livre (car je pense que malgré sa fantaisie, il est assez sérieux quant au fond du propos) c’est la beauté de l’amour qui unit un fils et sa mère (malgré les turbulences et l’incompréhension), l’enseignement zen qui transparaît dans le petit livre (nettoyer et soigner ses possessions chères plutôt que de les accumuler est un amour noble et bienfaisant ; le destin d’une tasse est d’être cassé, alors autant se réjouir tant qu’elle ne l’est pas, et si elle se casse, on peut aussi la réparer en la recollant en insérant de l’or qui soulignera les éclats plutôt que de les gommer ; les choses sont bonnes quand on comprend qu’elles sont de passage, comme nous, et quand elles sont utiles), la solidarité entre les humains permet d’accomplir beaucoup et aide à se sentir part du monde, du cosmos. Que les fous ne sont pas toujours ceux que l’on croit, que leurs voix comptent. Que les livres sont des objets à part, presque autonomes, mais qu’ils souffrent s’ils sont désertés, et restent impuissants face à la tournure des histoires qu’ils racontent.

C’est donc un livre né d’une riche imagination, qui traite de questions existentielles par le biais de détours romanesques et d’inventions poétiques, et d’une philosophie en filigrane très subtile et intéressante. Le zen a beaucoup à nous apprendre je pense, enfin, personnellement, je me suis sentie concernée.

Le récit désarçonne plus d’une fois, manque de nous perdre, mais nous rattrape par la manche, d’un coup, avec une idée jolie, et une galerie de personnages attachants plutôt bien campés. (Annabelle m’a beaucoup touchée.)

(Est-ce un hasard si j’ai passé ma semaine de vacances à ranger et trier ma maison et à nettoyer des coins oubliés depuis des mois et que ça m’a fait beaucoup de bien ?)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dr. Riittakerttu Kaltiala, 58, is a Finnish-born and trained adolescent psychiatrist, the chief psychiatrist in the department of adolescent psychiatry at Finland’s Tampere University Hospital. She treats patients, teaches medical students, and conducts research in her field—publishing more than 230 scientific articles.

In 2011, Dr. Kaltiala was assigned a new responsibility. She was to oversee the establishment of a gender identity service for minors, making her among the first physicians in the world to head a clinic devoted to the treatment of gender-distressed young people. Since then, she has personally participated in the assessments of more than 500 such adolescents.

Earlier this year, The Free Press ran a whistleblower account by Jamie Reed, a former case manager at The Washington University Transgender Center at St. Louis Children’s Hospital. She recounted her growing alarm at the effects of treatments that sought to transition minors to the opposite sex, and her escalating conviction that patients were being harmed by their treatment.

Although a recent New York Times investigation largely corroborated Reed’s account, many activists and members of the media continue to dismiss Reed’s claims because she is not a physician.

Dr. Kaltiala is. And her concerns are likely to get more attention in the U.S. now that a young woman who medically transitioned as a teenager has just sued the doctors who supervised her treatment, along with the American Academy of Pediatrics. According to the suit, the AAP, in advocating for youth transition, has made “outright fraudulent statements” about evidence for “the radical new treatment model, and the known dangers and potential side effects of the medical interventions it advocates.”

Here, Dr. Kaltiala tells her own story, describing her increasing worries about the treatment she approved for vulnerable patients, and her decision to speak out.

Early in my medical studies, I knew I wanted to be a psychiatrist. I decided to specialize in treating adolescents because I was fascinated by the process of young people actively exploring who they are and seeking their role in the world. My patients’ adult lives are still ahead of them, so it can make a huge difference to someone’s future to help a young person who is on a destructive track to find a more favorable course. And there are great rewards in doing individual therapeutic work.

Over the past dozen or so years there has been a dramatic development in my field. A new protocol was announced that called for the social and medical gender transition of children and teenagers who experienced gender dysphoria—that is, a discordance between one’s biological sex and an internal feeling of being a different gender.

This condition has been described for decades, and the 1950s is seen as the beginning of the modern era of transgender medicine. During the twentieth century, and into the twenty-first, small numbers of mostly adult men with lifelong gender distress have been treated with estrogen and surgery to help them live as women. Then in recent years came new research on whether medical transition—primarily hormonal—could be done successfully on minors.

One motivation of the medical professionals overseeing these treatments was to prevent young people from facing the difficulties adult men had experienced in trying to convincingly appear as women. The most prominent advocates of youth transition were a group of Dutch clinicians. They published a breakthrough paper in 2011 establishing that if young people with gender dysphoria were able to avoid their natural puberty by blocking it with pharmaceuticals, followed by receiving opposite-sex hormones, they could start living their transgender lives earlier and more credibly.

It became known as the “Dutch protocol.” The patient population the Dutch doctors described was a small number of young people—almost all male—who, from their earliest years, insisted they were girls. The carefully selected patients, apart from their gender distress, were mentally healthy and high-functioning. The Dutch clinicians reported that following early intervention, these young people thrived as members of the opposite sex. The protocol was quickly adopted internationally as the gold standard treatment in this new field of pediatric gender medicine.

Concurrently, there arose an activist movement that declared gender transition was not just a medical procedure, but a human right. This movement became increasingly high profile, and the activists’ agenda dominated the media coverage of this field. Advocates for transition also understood the power of the emerging technology of social media. In response to all this, in Finland the Ministry of Social Affairs and Health wanted to create a national pediatric gender program. The task was given to the two hospitals that already housed gender identity services for adults. In 2011, my department was tasked with opening this new service, and I as the chief psychiatrist became the head of it.

Even so, I had some serious questions about all this. We were being told to intervene in healthy, functioning bodies simply on the basis of a young person’s shifting feelings about gender. Adolescence is a complex period in which young people are consolidating their personalities, exploring sexual feelings, and becoming independent of their parents. Identity achievement is the outcome of successful adolescent development, not its starting point.

At our hospital, we had a big round of discussions with bioethicists. I expressed my concern that gender transition would interrupt and disrupt this crucial psychological and physical developmental stage. Finally, we obtained a statement from a national board on health ethics cautiously suggesting we undertake this new intervention.

We are a country of 5.5 million with a nationalized healthcare system, and because we required a second opinion to change identity documents and proceed to gender surgery, I have personally met and evaluated the majority of young patients at both clinics considering transition: to date, more than 500 young people. Approval for transition was not automatic. In early years, our psychiatric department agreed to transition for about half of those referred. In recent years, this has dropped to about twenty percent.

As the service got underway starting in 2011, there were many surprises. Not only did the patients come, they came in droves. Around the Western world the numbers of gender-dysphoric children were skyrocketing.

But the ones who came were nothing like what was described by the Dutch. We expected a small number of boys who had persistently declared they were girls. Instead, 90 percent of our patients were girls, mainly 15 to 17 years old, and instead of being high-functioning, the vast majority presented with severe psychiatric conditions.

Some came from families with multiple psychosocial problems. Most of them had challenging early childhoods marked by developmental difficulties, such as extreme temper tantrums and social isolation. Many had academic troubles. It was common for them to have been bullied—but generally not regarding their gender presentation. In adolescence they were lonely and withdrawn. Some were no longer in school, instead spending all their time alone in their room. They had depression and anxiety, some had eating disorders, many engaged in self-harm, a few had experienced psychotic episodes. Many—many—were on the autism spectrum.

Remarkably, few had expressed any gender dysphoria until their sudden announcement of it in adolescence. Now they were coming to us because their parents, usually just mothers, had been told by someone in an LGBT organization that gender identity was their child’s real problem, or the child had seen something online about the benefits of transition.

Even during the first few years of the clinic, gender medicine was becoming rapidly politicized. Few were raising questions about what the activists—who included medical professionals—were saying. And they were saying remarkable things. They asserted that not only would the feelings of gender distress immediately disappear if young people start to medically transition, but also that all their mental health problems would be alleviated by these interventions. Of course, there is no mechanism by which high doses of hormones resolve autism or any other underlying mental health condition.

Because what the Dutch had described differed so dramatically from what I was seeing in our clinic, I thought maybe there was something unusual about our patient population. So I started talking about our observations with a network of professionals in Europe. I found out that everybody was dealing with a similar caseload of girls with multiple psychiatric problems. Colleagues from different countries were confused by this, too. Many said it was a relief to hear their experience was not unique.

But no one was saying anything publicly. There was a feeling of pressure to provide what was supposed to be a wonderful new treatment. I felt in myself, and saw in others, a crisis of confidence. People stopped trusting their own observations about what was happening. We were having doubts about our education, clinical experience, and ability to read and produce scientific evidence.

Soon after our hospital began offering hormonal interventions for these patients, we began to see that the miracle we had been promised was not happening. What we were seeing was just the opposite.

The young people we were treating were not thriving. Instead, their lives were deteriorating. We thought, what is this? Because there wasn’t a hint in studies that this could happen. Sometimes the young people insisted their lives had improved and they were happier. But as a medical doctor, I could see that they were doing worse. They were withdrawing from all social activities. They were not making friends. They were not going to school. We continued to network with colleagues in different countries who said they were seeing the same things.

I became so concerned that I embarked on a study with my Finnish colleagues to describe our patients. We methodically went through the records of those who had been treated at the clinic its first two years, and we characterized how troubled they were—one of them was mute—and how much they differed from the Dutch patients. For example, more than a quarter of our patients were on the autism spectrum. Our study was published in 2015, and I believe it was the first journal publication from a gender clinician raising serious questions about this new treatment.

I knew others were making the same observations at their clinics, and I hoped my paper would spark discussion about their concerns—that’s how medicine corrects itself. But our field, instead of acknowledging the problems we described, became more committed to expanding these treatments.

In the U.S., your first pediatric gender clinic opened in Boston in 2007. Fifteen years later there were more than 100 such clinics. As the U.S. protocols developed, fewer limitations were put on transition. A Reuters investigation found that some U.S. clinics approved hormone treatments at a minor’s first visit. The U.S. pioneered a new treatment standard, called “gender-affirming care,” which urged clinicians simply to accept a child’s assertion of a trans identity, and to stop being “gatekeepers” who raised concerns about transition.

Around 2015, in addition to the very psychiatrically ill patients, a new set of patients started arriving at our clinic. We began to see groups of teenage girls, also usually from 15 to 17 years of age from the same small towns, or even the same schools, telling the same life stories and the same anecdotes about their childhoods, including their sudden realization that they were transgender—despite no prior history of dysphoria. We realized they were networking and exchanging information about how to talk to us. And so, we got our first experience of social contagion–linked gender dysphoria. This, too, was happening in pediatric gender clinics around the world, and again health providers were failing to speak up.

I understood this silence. Anyone, including physicians, researchers, academics, and writers, who raised concerns about the growing power of gender activists, and about the effects of medically transitioning young people, were subjected to organized campaigns of vilification and threats to their careers.

In 2016, because of several years of growing concern about the harms of transition on vulnerable young patients, Finland’s two pediatric gender services changed their protocols. Now, if young people had other, more urgent problems than gender dysphoria that needed to be addressed, we promptly referred those patients for more appropriate treatment, such as psychiatric counseling, rather than continuing their gender identity assessment.

There was a lot of pressure against this approach from activists, politicians, and the media. The Finnish press published stories of young people dissatisfied with our decision, portraying them as victims of gender clinics that were forcing them to put their lives on hold. A Finnish medical journal ran a piece that took the perspective of dissatisfied activists titled, “Why do trans adolescents not get their blockers?”

But I was trained that medical treatment has to be based on medical evidence, and that medicine has to constantly correct itself. When you are a physician who sees something is not working, it is your duty to organize, research, inform your colleagues, inform a big audience, and stop doing that treatment.

Finland’s national healthcare system gives us the ability to investigate current medical practices and set new guidelines. In 2015 I personally asked a national body, called the Council for Choices in Health Care (COHERE), to create national guidelines for treatment of gender dysphoria in minors. In 2018 I renewed this request with colleagues, and it was accepted. COHERE commissioned a systematic evidence review to assess the reliability of the current medical literature on youth transition.

Around this same time, eight years into the opening of the pediatric gender clinic, some previous patients started coming back to tell us they now regretted their transition. Some—called “detransitioners”—wished to return to their birth sex. These were another kind of patient who wasn’t supposed to exist. The authors of the Dutch protocol asserted that rates of regret were miniscule.

But the foundation on which the Dutch protocol was based is crumbling. Researchers have shown that their data had some serious problems, and that in their follow-up, they failed to include many of the very people who may have regretted transition or changed their minds. One of the patients had died due to complications from genital transition surgery.

There is an oft-repeated statistic in the world of pediatric gender medicine that only one percent or less of young people who transition subsequently detransition. The studies asserting this, too, rest on biased questions, inadequate samples, and short timelines. I believe regret is far more widespread. For example, one new study shows that nearly 30 percent of patients in the sample ceased filling their hormone prescription within four years.

Usually, it takes several years for the full impact of transition to settle in. This is when young people who have entered adulthood confront what it means to possibly be sterile, to have damaged sexual function, to have great difficulty in finding romantic partners.

It is devastating to speak to patients who say they were naive and misguided about what transition would mean for them, and who now feel it was a terrible mistake. Mainly these patients tell me they were so convinced they needed to transition that they concealed information or lied in the assessment process.

I continued to research the issue and in 2018, with colleagues, I published another paper, one that investigated the origin of the surging numbers of gender-dysphoric young people. But we didn’t find answers as to why this was happening, or what to do about it. We noted in our study a point that is generally ignored by gender activists. That is, for the overwhelming majority of gender dysphoric children—around 80 percent—their dysphoria resolves itself if they are left to go through natural puberty. Often these children come to realize they are gay.

In June of 2020 a major event happened in my field. Finland’s national medical body, COHERE, released its findings and recommendations regarding youth gender transition. It concluded that the studies touting the success of the “gender-affirming” model were biased and unreliable—systematically so in some cases.

The authors wrote: “In light of available evidence, gender reassignment of minors is an experimental practice.” The report stated that young patients seeking gender transition should be instructed about “the reality of a lifelong commitment to medical therapy, the permanence of the effects, and the possible physical and mental adverse effects of the treatments.” The report warned that young people, whose brains were still maturing, lacked the ability to properly “assess the consequences” of making decisions they would have to live with for the “rest of their lives.”

COHERE also recognized the dangers of giving hormone treatments to young people with serious mental illness. The authors concluded that for all these reasons, gender transition should be postponed “until adulthood.”

It had taken quite a while, but I felt vindicated.

Fortunately, Finland is not alone. After similar reviews, the UK and Sweden have come to similar conclusions. And many other countries with national healthcare systems are re-evaluating their “gender-affirming” stance.

I felt an increasing obligation to patients, to medicine, and to the truth, to speak outside of Finland against the widespread transitioning of gender-distressed minors. I have been particularly concerned about American medical societies, who as a group continue to assert that children know their “authentic” selves, and a child who declares a transgender identity should be affirmed and started on treatment. (In recent years, the “trans” identity has evolved to include more young people who say they are “nonbinary”—that is, they feel they don’t belong to either sex—and other gender variations.)

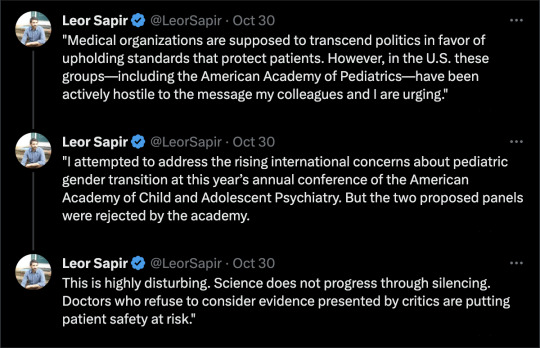

Medical organizations are supposed to transcend politics in favor of upholding standards that protect patients. However, in the U.S. these groups—including the American Academy of Pediatrics—have been actively hostile to the message my colleagues and I are urging.

I attempted to address the rising international concerns about pediatric gender transition at this year’s annual conference of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. But the two proposed panels were rejected by the academy. This is highly disturbing. Science does not progress through silencing. Doctors who refuse to consider evidence presented by critics are putting patient safety at risk.

I am also disturbed by how gender clinicians routinely warn American parents that there is an enormously elevated risk of suicide if they stand in the way of their child’s transition. Any young person’s death is a tragedy, but careful research shows that suicide is very rare. It is dishonest and extremely unethical to pressure parents into approving gender medicalization by exaggerating the risk of suicide.

This year the Endocrine Society of the U.S. reiterated its endorsement of hormonal gender transition for young people. The president of the society wrote in a letter to The Wall Street Journal that such care was “lifesaving” and “reduces the risk of suicide.” I was a co-author of a letter in response, signed by 20 clinicians from nine countries, refuting his assertion. We wrote that, “Every systematic review of evidence to date, including one published in the Journal of the Endocrine Society, has found the evidence for mental health benefits of hormonal interventions for minors to be of low or very low certainty.”

Medicine, unfortunately, is not immune to dangerous groupthink that results in patient harm. What is happening to dysphoric children reminds me of the recovered memory craze of the 1980s and ’90s. During that period, many troubled women came to believe false memories, often suggested to them by their therapists, of nonexistent sexual abuse by their fathers or other family members. This abuse, the therapists said, explained everything that was wrong with the lives of their patients. Families were torn apart, and some people were prosecuted based on made-up assertions. It ended when therapists, journalists, and lawyers investigated and exposed what was happening.

We need to learn from such scandals. Because, like recovered memory, gender transition has gotten out of hand. When medical professionals start saying they have one answer that applies everywhere, or that they have a cure for all of life’s pains, that should be a warning to us all that something has gone very wrong.

0 notes

Text

"𝐖𝐞𝐥𝐜𝐨𝐦𝐞 𝐭𝐨 𝐏𝐫𝐞𝐬𝐞𝐧𝐭 𝐏𝐬𝐲𝐜𝐡𝐢𝐚𝐭𝐫𝐲, your trusted provider of online psychiatry services (tele-health psychiatry). As the best psychiatrist in Houston, Texas, we offer comprehensive mental health care tailored to your needs. Our services include initial psychiatric diagnostic evaluations, psychiatric follow-ups, medication management, and various therapy options like talk therapy, psychotherapy, and CBT. We also provide cognitive assessments for older adults and treat conditions such as depression, anxiety, 𝐏𝐓𝐒𝐃, 𝐀𝐃𝐇𝐃, schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, and bipolar disorder. We cater to patients of all ages, including children (12 and up), adolescents, and adults. #BestPsychiatristHouston#OnlinePsychiatry"Ask me anythingFollow

0 notes

Text

Do You Know The 6 Basic Responsibilities Of A Psychiatrist Near Me For Anxiety?

Mental health is important for all ages, for children and adolescents, to adults and seniors. If how we think, feel, and act is affected, our ability to cope with life may be compromised. Getting early help creates better practices of how we handle stress, relate to others, and make sound life choices.

Search for Hope and Healing Psychiatrist Near Me For Anxiety

We Empower individuals

Psychiatry helps empower individuals to make major changes in their life, and to pinpoint underlying issues related to their mental or behavioural health patterns.

Improving Your Quality of Life

Accessible psychiatric support provides a timely diagnosis, medication recommendations and monitoring. Helping you initiate your journey to recovery faster.

If you believe that you would benefit from the services our Psychiatrist Near Me For Anxiety can provide, contact our clinic today.

Here are some typical responsibilities of a psychiatrist near me for Anxiety at Hope & Healing:

They conduct physical examinations and interviews to assess the patient's condition. They usually write a medical report based on the findings and provide the patient with an individualised treatment plan.

Psychiatrists prepare written tests to determine whether the patient is mentally competent or to identify mental health conditions. These tests usually include memory exercises, logical reasoning, and psychological questionnaires.

Psychiatrists conduct clinical research to study the effectiveness of treatments for psychiatric disorders, evaluate a drug's side effects, or learn more about a mental health condition.

Psychiatrists are able to prescribe medications to treat patients' symptoms. For example, they may prescribe antidepressants, mood stabilisers, and anti-anxiety medication

These health care specialists sometimes apply a talk-therapy approach to help patients manage the loss of a family member, school failure, divorce, or workplace issues. This treatment aims to encourage patients to share their feelings, experiences, and thoughts with the psychiatrist to gain insight into their condition and improve their quality of life.

It's mandatory for psychiatrists to document each patient's case history, any research or findings they collected, and what treatments they prescribed and why. This information helps other doctors learn from their notes, and shows the effectiveness of a treatment.

Match with a Psychiatrist Near Me For Anxiety with Hope & Healing

If you're ready to treat your anxiety and improve your mental health, we can help! To match with the perfect online or in-person Psychiatrist for your unique preferences and needs, connect today!

Read more...

youtube

#TherapyNearMe#CounselorNearMeforAnxiety#PennsylvaniaCounselingCenter#PsychiatristNearMeForAnxiety#TherapistNearMeforAnxiety#Youtube

0 notes

Text

Access Health Services | Why Adolescent Psychiatry Services are Important

Adolescence is a critical period of development where individuals experience significant physical, emotional, and social changes. It is also a time when many mental health conditions emerge or worsen.

According to the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI), 1 in 6 youth aged 6-17 experience a mental health disorder each year. Untreated mental health conditions can have a significant impact on a teenager’s overall well-being, including their academic performance, relationships, and future opportunities.

As a parent or caregiver, it can be challenging to know when to seek help for your teenager’s mental health. Some common signs that may indicate a need for adolescent psychiatry services include.

Adolescent Psychiatry Services: Click Now

#Adolescent Psychiatry Services#Adolescent Psychiatry Care#Adolescent Psychiatry Service#Telehealth Therapist Clinic#Telehealth Companies Washington#Telehealth Psychiatrist Near Me#Telehealth Therapy Washington#Medication Therapy Management Services#Weight Management Medication

0 notes

Text

Protocols for transitioning to adult mental health services for adolescents with ADHD | BMC Psychiatry | Full Text

Background For Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) youth transitioning from child to adult services, protocols that guide the transition process are essential. While some guidelines are available, they do not always consider the effective workload and scarce resources. In Italy, very few guidelines are currently available, and they do not adhere to common standards, possibly leading to non-uniform use. Methods The present study analyzes 6 protocols collected from the 21 Italian services for ADHD patients that took part in the TransiDEA (Transitioning in Diabetes, Epilepsy, and ADHD patients) Project. .

American Institute Health Care Professionals's insight:

Protocols for transitioning to adult mental health services for adolescents with ADHD | BMC Psychiatry

0 notes

Text

By: Riittakerttu Kaltiala

Published: Oct 30, 2023

Dr. Riittakerttu Kaltiala, 58, is a Finnish-born and trained adolescent psychiatrist, the chief psychiatrist in the department of adolescent psychiatry at Finland’s Tampere University Hospital. She treats patients, teaches medical students, and conducts research in her field—publishing more than 230 scientific articles.

In 2011, Dr. Kaltiala was assigned a new responsibility. She was to oversee the establishment of a gender identity service for minors, making her among the first physicians in the world to head a clinic devoted to the treatment of gender-distressed young people. Since then, she has personally participated in the assessments of more than 500 such adolescents.

Earlier this year, The Free Press ran a whistleblower account by Jamie Reed, a former case manager at The Washington University Transgender Center at St. Louis Children’s Hospital. She recounted her growing alarm at the effects of treatments that sought to transition minors to the opposite sex, and her escalating conviction that patients were being harmed by their treatment.

Although a recent New York Times investigation largely corroborated Reed’s account, many activists and members of the media continue to dismiss Reed’s claims because she is not a physician.

Dr. Kaltiala is. And her concerns are likely to get more attention in the U.S. now that a young woman who medically transitioned as a teenager has just sued the doctors who supervised her treatment, along with the American Academy of Pediatrics. According to the suit, the AAP, in advocating for youth transition, has made “outright fraudulent statements” about evidence for “the radical new treatment model, and the known dangers and potential side effects of the medical interventions it advocates.”

Here, Dr. Kaltiala tells her own story, describing her increasing worries about the treatment she approved for vulnerable patients, and her decision to speak out.

--

Early in my medical studies, I knew I wanted to be a psychiatrist. I decided to specialize in treating adolescents because I was fascinated by the process of young people actively exploring who they are and seeking their role in the world. My patients’ adult lives are still ahead of them, so it can make a huge difference to someone’s future to help a young person who is on a destructive track to find a more favorable course. And there are great rewards in doing individual therapeutic work.

Over the past dozen or so years there has been a dramatic development in my field. A new protocol was announced that called for the social and medical gender transition of children and teenagers who experienced gender dysphoria—that is, a discordance between one’s biological sex and an internal feeling of being a different gender.

This condition has been described for decades, and the 1950s is seen as the beginning of the modern era of transgender medicine. During the twentieth century, and into the twenty-first, small numbers of mostly adult men with lifelong gender distress have been treated with estrogen and surgery to help them live as women. Then in recent years came new research on whether medical transition—primarily hormonal—could be done successfully on minors.

One motivation of the medical professionals overseeing these treatments was to prevent young people from facing the difficulties adult men had experienced in trying to convincingly appear as women. The most prominent advocates of youth transition were a group of Dutch clinicians. They published a breakthrough paper in 2011 establishing that if young people with gender dysphoria were able to avoid their natural puberty by blocking it with pharmaceuticals, followed by receiving opposite-sex hormones, they could start living their transgender lives earlier and more credibly.

It became known as the “Dutch protocol.” The patient population the Dutch doctors described was a small number of young people—almost all male—who, from their earliest years, insisted they were girls. The carefully selected patients, apart from their gender distress, were mentally healthy and high-functioning. The Dutch clinicians reported that following early intervention, these young people thrived as members of the opposite sex. The protocol was quickly adopted internationally as the gold standard treatment in this new field of pediatric gender medicine.

Concurrently, there arose an activist movement that declared gender transition was not just a medical procedure, but a human right. This movement became increasingly high profile, and the activists’ agenda dominated the media coverage of this field. Advocates for transition also understood the power of the emerging technology of social media. In response to all this, in Finland the Ministry of Social Affairs and Health wanted to create a national pediatric gender program. The task was given to the two hospitals that already housed gender identity services for adults. In 2011, my department was tasked with opening this new service, and I as the chief psychiatrist became the head of it.

Even so, I had some serious questions about all this. We were being told to intervene in healthy, functioning bodies simply on the basis of a young person’s shifting feelings about gender. Adolescence is a complex period in which young people are consolidating their personalities, exploring sexual feelings, and becoming independent of their parents. Identity achievement is the outcome of successful adolescent development, not its starting point.

At our hospital, we had a big round of discussions with bioethicists. I expressed my concern that gender transition would interrupt and disrupt this crucial psychological and physical developmental stage. Finally, we obtained a statement from a national board on health ethics cautiously suggesting we undertake this new intervention.

We are a country of 5.5 million with a nationalized healthcare system, and because we required a second opinion to change identity documents and proceed to gender surgery, I have personally met and evaluated the majority of young patients at both clinics considering transition: to date, more than 500 young people. Approval for transition was not automatic. In early years, our psychiatric department agreed to transition for about half of those referred. In recent years, this has dropped to about twenty percent.

As the service got underway starting in 2011, there were many surprises. Not only did the patients come, they came in droves. Around the Western world the numbers of gender-dysphoric children were skyrocketing.

But the ones who came were nothing like what was described by the Dutch. We expected a small number of boys who had persistently declared they were girls. Instead, 90 percent of our patients were girls, mainly 15 to 17 years old, and instead of being high-functioning, the vast majority presented with severe psychiatric conditions.

Some came from families with multiple psychosocial problems. Most of them had challenging early childhoods marked by developmental difficulties, such as extreme temper tantrums and social isolation. Many had academic troubles. It was common for them to have been bullied—but generally not regarding their gender presentation. In adolescence they were lonely and withdrawn. Some were no longer in school, instead spending all their time alone in their room. They had depression and anxiety, some had eating disorders, many engaged in self-harm, a few had experienced psychotic episodes. Many—many—were on the autism spectrum.

Remarkably, few had expressed any gender dysphoria until their sudden announcement of it in adolescence. Now they were coming to us because their parents, usually just mothers, had been told by someone in an LGBT organization that gender identity was their child’s real problem, or the child had seen something online about the benefits of transition.

Even during the first few years of the clinic, gender medicine was becoming rapidly politicized. Few were raising questions about what the activists—who included medical professionals—were saying. And they were saying remarkable things. They asserted that not only would the feelings of gender distress immediately disappear if young people start to medically transition, but also that all their mental health problems would be alleviated by these interventions. Of course, there is no mechanism by which high doses of hormones resolve autism or any other underlying mental health condition.

Because what the Dutch had described differed so dramatically from what I was seeing in our clinic, I thought maybe there was something unusual about our patient population. So I started talking about our observations with a network of professionals in Europe. I found out that everybody was dealing with a similar caseload of girls with multiple psychiatric problems. Colleagues from different countries were confused by this, too. Many said it was a relief to hear their experience was not unique.

But no one was saying anything publicly. There was a feeling of pressure to provide what was supposed to be a wonderful new treatment. I felt in myself, and saw in others, a crisis of confidence. People stopped trusting their own observations about what was happening. We were having doubts about our education, clinical experience, and ability to read and produce scientific evidence.

Soon after our hospital began offering hormonal interventions for these patients, we began to see that the miracle we had been promised was not happening. What we were seeing was just the opposite.

The young people we were treating were not thriving. Instead, their lives were deteriorating. We thought, what is this? Because there wasn’t a hint in studies that this could happen. Sometimes the young people insisted their lives had improved and they were happier. But as a medical doctor, I could see that they were doing worse. They were withdrawing from all social activities. They were not making friends. They were not going to school. We continued to network with colleagues in different countries who said they were seeing the same things.

I became so concerned that I embarked on a study with my Finnish colleagues to describe our patients. We methodically went through the records of those who had been treated at the clinic its first two years, and we characterized how troubled they were—one of them was mute—and how much they differed from the Dutch patients. For example, more than a quarter of our patients were on the autism spectrum. Our study was published in 2015, and I believe it was the first journal publication from a gender clinician raising serious questions about this new treatment.

I knew others were making the same observations at their clinics, and I hoped my paper would spark discussion about their concerns—that’s how medicine corrects itself. But our field, instead of acknowledging the problems we described, became more committed to expanding these treatments.

In the U.S., your first pediatric gender clinic opened in Boston in 2007. Fifteen years later there were more than 100 such clinics. As the U.S. protocols developed, fewer limitations were put on transition. A Reuters investigation found that some U.S. clinics approved hormone treatments at a minor’s first visit. The U.S. pioneered a new treatment standard, called “gender-affirming care,” which urged clinicians simply to accept a child’s assertion of a trans identity, and to stop being “gatekeepers” who raised concerns about transition.

Around 2015, in addition to the very psychiatrically ill patients, a new set of patients started arriving at our clinic. We began to see groups of teenage girls, also usually from 15 to 17 years of age from the same small towns, or even the same schools, telling the same life stories and the same anecdotes about their childhoods, including their sudden realization that they were transgender—despite no prior history of dysphoria. We realized they were networking and exchanging information about how to talk to us. And so, we got our first experience of social contagion–linked gender dysphoria. This, too, was happening in pediatric gender clinics around the world, and again health providers were failing to speak up.

I understood this silence. Anyone, including physicians, researchers, academics, and writers, who raised concerns about the growing power of gender activists, and about the effects of medically transitioning young people, were subjected to organized campaigns of vilification and threats to their careers.