#Ailsa is Caithness

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

Do you have Faroe Islands and Aaland islands OCs? 😊 Or other children of the Nordics. How do you view them? I would like to know

I do have Faroe and Åland oc's though they're both kinda work in progresses still 😅

for a total list you have

Denmark's kids

Kalmar Union - Henrik (deceased)

Kristiania - Benedikte

Sweden's kids

Åland - Kristiina

New Sweden - Johan (deceased)

Ladonia - Arvid

Norway's kids (not particularly in age order; my man got around during the viking age lmao)

Shetland - Liv

Orkney - Bodil

Faroe - Ida

Iceland - Ari

Isle of Man - Erik

Caithness - Ailsa

Sutherland - Solveig

Greenland - Sia

Helluland - Anders (deceased)

Markland - Aksel (deceased)

Vinland - Dagny (deceased)

how I view all of them would be a really long post so i'll just do what I have for Åland because out of the two you asked for I have more on her haha ( side note; I hc Finland as being trans and all three of Sweden's kids were mothered by Fin)

So anyway; Kristiina was born in the 1380s around the same time Kastelholm Castle was built. That makes her younger than all of Norway's kids by a good 300 years, but older than Denmark's oldest by about 10-15 years (aka her and Henrik were physically about the same age). Her childhood was interesting, cause not only was it a time when upper class/noble parents weren't all that involved in raising their children but also Björn wasn't around all that often, and Kasper really didn't get along all that well with Björn at the time and was distant not wanting to acknowledge they had a child together. All of her cousins were either far older, or had more responsibilities than her; because I do believe her and Henrik did a few years of their basic schooling together he reached about ten and suddenly was being taught things 'not appropriate for young ladies'. So she's alone again.

In August of 1521 when Harald and Björn got into their Last Big Fight, the Straw that would break the camels back; all she remembers about actually leaving are snippets where she woke up to her papa carrying her, and her parents whisper arguing about something (she couldn't tell you what). She was told she woke up at some point and asked where they were going but was just told not to worry about it, and to be quiet. There was a year or two where she was left in Lübeck in Germany with a couple different people to watch over her. She didn't really see either of her parents for those two years, they didn't even technically come back for her. A letter just came one day asking for her to brought to Stockholm. At the time she was just relieved to see her parents again, but now she sometimes look back at it in a bittersweet way, it took two years of being apart for them to be excited to see her.

I'm gonna jump forward to 1809; she's about fifteen physically when Finland and Åland are ceded to Russia. For the first time in her life she had no one to speak to except her mother, Kristiina had always gravitated towards Björn because he never well... he never seemed as if he regretted her existence, to be blunt. Even when he was gone on months long trips for some reason or another she would beg to go with him to avoid being stuck with just her mother. But her uncle was there at least, and Kasper turned into an entirely different person around Kalev; a happier person, even if comparatively the situation was worse.

It was still super odd for Kris, she had been around mostly her dads family her entire life and suddenly she's been moved from her home and is interacting far more with her mom's side of the family (her Finnish is iffy at best at this point). And her mother, a woman she had always known to be very quiet and fidgety was suddenly loud and always getting in dumb fights with her siblings. The big turning point in their relationship would be a fight they would get into where something along the lines of "Don't you want to go back to Stockholm? Don't you want to go home?" "Stockholm was never home." would be said.

jumping to modern day bc i'm bored

she's kind of distant by now, her relationship to both her parents became odd once she went to live by herself, and even a little more when Arvid was born because both of her parents were happy about him and it upsets her seeing them treat him differently.

It's not as if her relationship with them is absolute garbage, and she's bitter and isolates herself now. She's just an adult, and there's things from her childhood, and with her relationships to her parents she's had to reconcile. I think she's accidentally become very close to Kalev because he seemed like Kasper's opposite while still being family and someone she could see regularly. She did want to be apart of Sweden again for a little bit, but not in a 'would be upset if it didn't happen' way because she is also trying to be on better terms with Kasper.

I don't know... she just had a long and complicated childhood most nations do, and now she's just doing her best to hang on to the things she did like about it, while also trying to forget most of it? If that makes sense.

also kinda random side note: I think she prides herself on being more 'quiet and stoic' like Sweden but anyone who's been around her for more than five minutes knows she is neither of those things and is far more like Finland. Though no on is going to tell her that.

#hws åland#hws sweden#hws finland#sorry this took so long!!#hetalia#i know it's kinda rambly and long i'm bad at talking about oc's personalities without giving entire histories about them

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Isobel Bruce, Queen of Norway (c.1272-1358)

It may come as a surprise to some that the infamous King Robert I was not the first Bruce to wear a crown. That distinction goes instead to one of his many sisters, Isobel, who, in 1293, became Queen of Norway as the wife of King Eirik II, long before her brother got anywhere near the throne.

Isobel Bruce was the daughter of Marjorie, Countess of Carrick, and her second husband Robert Bruce, 6th Lord of Annandale. Some Norwegian historians place Isobel's birth c.1280, but I’m more inclined to agree with other sources that she was the eldest daughter and closer in age to her brother Robert, who was born in 1274. We have almost no certain information about Isobel’s youth, though we can perhaps theorise about her early social surroundings. Bruce ambitions and experiences- especially for Isobel’s generation- were shaped by many diverse political and cultural contexts. The family had a stake in the largely Gaelic world of Irish Sea politics, from Ulster to Carrick; in English-speaking territories as different as Annandale and Essex; and as part of a French-speaking elite among the English and Scottish nobility, with both continental and insular ambitions. The Bruces were also a large family, Isobel having five brothers (Robert, Niall, Edward, Thomas and Alexander) and at least as many sisters (including Christian, Mary, and Matilda). The antiquated assertion that she was married before the Norwegian match (explaining how Thomas Randolph might be nephew to King Robert) seems extremely unlikely however, and it is more probable one of her parents had another daughter named Isobel who was Randolph's mother.

(The lighthouse here is perched on top of what little is left of Turnberry Castle, seat of Isobel’s mother as countess of Carrick, and one of the childhood homes of the Bruce children, maybe even the birthplace of her brother Robert I. It is situated on the Ayrshire coastline, with Ailsa Craig out to sea. Not my picture)

However, despite the lack of information about her early life, Isobel Bruce’s importance increased in the 1290s- as did her family’s importance more generally. King Alexander III of Scotland had died in 1286, his only living descendant being his granddaughter Margaret of Norway, daughter of Eirik II of Norway by his first wife Margaret of Scotland. But in 1290 the Maid of Norway also died, which provoked a competition for the throne commonly called the Great Cause. I won't go into detail here, but briefly the two main contenders were John Balliol and Isobel’s grandfather Robert Bruce, 'the Competitor’. Eventually, Balliol's case triumphed but this didn't extinguish Bruce ambitions regarding the throne. And it was during the final stages of the Great Cause in 1292- not long before her mother’s death in that same year- that the prospect of Isobel marrying the king of Norway initially surfaced.

Eirik II of Norway had been one of the claimants for the Scottish throne, attempting to inherit through Norse reversionary law as the father of the dead Maid of Norway, though probably the Norwegians never had any serious hope of this claim succeeding, and instead used it as an opportunity to wring political and financial concessions from the Scottish and English crowns. Eirik Magnusson was roughly twenty-four years old in 1292, he had been a widower since the age of fifteen, and the late Margaret of Norway had been his only known child (his brother Duke Håkon however was the more viable heir). Aside from these obvious reasons though, it is a little unclear why he married Isobel Bruce the next year. It is possible that the plans had been made in advance of the decision in favour of Balliol’s claim to the Scottish throne in November 1292, and could have represented the Norwegians’ allying themselves with the Bruce claim as another claimant Florence, Count of Holland had. Alternatively, if the plans were made after Balliol’s claim had won out, the Norwegian king may have been strengthening his relations with the Bruces as powerful magnates who were deeply opposed to the new king of Scots, and in doing so strengthened his relationship with Edward I of England. However given that in 1295 Norway entered into a treaty with France- who had also made a treaty with King John of Scotland which would eventually lead to his deposition by Edward I- promising aid against England, it is very difficult to pin down the exact political strategy which Isobel Bruce’s marriage represented. Nonetheless on 28th September 1293*, Isobel and her father Robert Bruce- named as Earl of Carrick though he had resigned the earldom the previous year to his son- received a safe-conduct from Edward I of England to travel to Norway by Christmas that year, and Isobel and Eirik II were likely married in Bergen soon afterward.

Though sources are sparse for Isobel’s marriage, an inventory of some of her belongings does exist, providing rare evidence of a thirteenth century queen’s trousseau. An indenture dated 25th September 1293, preserved in the English archives, lists certain items to be delivered to Audun Hugleiksson (one of Eirik II’s most trusted advisors) and Weyland de Stiklaw in Bergen before Michaelmas, by Henry de Stiklaw, ‘Master’ Nigel Campbell, Lucas de Tany, and Ralph de Arden. The items were for ‘the most serene lady’ the Queen of Norway, and evidently formed part of an expensive trousseau. Among other furnishings and clothing are listed robes of scarlet and miniver, with tunics and supertunics to form four or more outfits, furred cloaks and hoods, coverlets and bed hangings in cloth of gold and miniver (one bearing the arms of France), various cushions and curtains for two couches, and silk to make a cushion for the Queen’s regalia. The list is topped off with 24 silver plates, 12 cups, 24 salt cellars, basins and pitchers and the like, not to mention two small crowns. For a young bride such possessions served as an expression of status as she travelled far from home, and while they were not as extravagant as the more famous trousseau of Isabella of France, they were still rich pickings for the daughter of an earl, calculated to impress as far as her father could afford...

(Eirik Magnusson, king of Norway. In Norwegian history he is known as ‘priest-hater’ and is remembered for his wars with Denmark and for being dominated by his barons. In Scottish history, he is remembered as having two Scottish queens and especially for being the father of the Maid of Norway. Picture from Wikimedia commons.)

After Isobel’s wedding we lack sources again. Little is known about her life as queen consort, excepting the birth of her daughter in 1297. Ingebjørg Eiriksdatter, likely named for her paternal grandmother, was the only one of Eirik II's two known children to survive him; her half-sister, the unfortunate Margaret, had of course died long before Ingebjørg was born. Thus when Eirik himself died in 1299 the crown passed to his younger brother Duke Håkon, and Isobel, consort for only six years, was left a widow with an infant daughter.

Despite the insecurity that could come with widowhood, Isobel was not in any hurry to remarry. She remained on good terms with King Håkon and the new queen, Eufemia of Rügen, and attended important state occasions. Nevertheless, the winds of change were blowing in Norway. Håkon V’s rule was quite different to his late brother's, and he wasted little time disposing of certain former royal councillors, notably imprisoning and executing Audun Hugleiksson by the dishonourable method of hanging. Håkon also favoured Oslo, and during his reign the city began to outstrip Bergen as a centre of royal power. While Norway under Håkon would have more of an eastern outlook, however, Isobel remained in the west for most of her widowhood, playing an important role in the spiritual life of Bergen.

She still had her daughter’s future to think about however, and in 1300 this may have resulted in a plan to marry Ingebjørg to Jon Magnusson, Earl of Orkney and Caithness, though as this betrothal is only recorded in the Icelandic Annals it is difficult to assess its context. Earl Jon was, by each earldom respectively, subject to Norway and Scotland, and his status was defined by this dual allegiance. During the Wars of Independence, he may have inclined towards the Bruce camp, but this is ultimately unclear. But he was still just as much a Norwegian magnate, and perhaps this convenient position between the two kingdoms was what influenced Isobel's choice. Despite the fact that the prospective bride was only three and the earl much older, these plans may also have been put in place to safeguard her daughter’s future given her uncertain inheritance: Barbara E. Crawford believes that the proposed match, “seems to have been a desperate attempt to find a protector for the fatherless child”. The marriage was not to be, however, as Earl Jon died soon after.

This may not have been the end of Isobel’s interests in Orkney however, as a royal official previously strongly associated with her rose to power there soon afterwards. Weyland de Striklaw, who we already met briefly receiving delivery of the goods for Isobel’s trousseau, had once been a canon of Dunkeld and maybe even Alexander III’s chamberlain, but from the 1290s onward he and his brother Henry were more associated with the Bruces. It seems that he may also have had strong personal feelings on the political situation in Scotland, as in 1297 it was recorded that he had been banished by the English regime in Scotland for failing to obey their government. In any case he found employment in the service of the Norwegian Crown, probably as a result of his association with Isobel (then queen consort) whose patronage may partly account for his prominence in Norwegian royal documents during the last years of the reign of Eirik II and the early years of King Haakon’s rule. Fortune favoured him further after the death of Jon, Earl of Orkney, when he somehow managed to become guardian to the earl’s successor, Magnus, and gained control of administration in Orkney and later Caithness. We have little evidence of Isobel and Weyland’s direct cooperation in this affair, but it seems plausible that, given his earlier association with the queen it was partially her influence that helped him secure his position in Orkney, and could be taken as evidence of Isobel’s discreet political activity after her husband’s death.

(A much later depiction- with anachronistic kilts- of Isabella’s sister Mary Bruce imprisoned in a cage outside Roxburgh)

Meanwhile, since Isobel's departure in 1293, Scotland had plunged into the first phase of a bitter and prolonged war, both with England and internally. John Balliol had been deposed by Edward I but rebellions still occurred and others claimed the Scottish throne, most notably Isobel’s brother, Robert. In 1306, he had himself crowned king at Scone, but the first year of his ‘reign’ did not go well and he was forced to flee into the west. It is probable that he took refuge in the Western Isles, and also in the islands of Ireland, though some historians have argued that he could perhaps have gone to Orkney or perhaps even Norway. Certainly the ladies of his court, before being captured and handed over to the English, appear to have been heading to the safety of Orkney, where they would then be able to seek protection in the name of the queen dowager. Instead they remained in English captivity until after 1314. Two of the ladies- Isobel's sister, Mary and Isabella, Countess of Buchan- were quite literally imprisoned in ‘cages’ suspended outside the castles of Roxburgh and Berwick. Another of Isobel’s sisters, Christian, endured a slightly less extreme imprisonment at Sixhills nunnery in Lincolnshire, while her sister-in-law, Robert’s queen Elizabeth de Burgh, was held under house arrest. Young Marjorie Bruce, Isobel’s niece had also originally been intended for a cage but was instead transferred to a convent. Isobel’s brother Niall, who had defended Kildrummy Castle while the women escaped north, was executed by the degrading method of being hanged, drawn, and quartered, while two more of her brothers, Thomas and Alexander, were hanged following a failed invasion of Galloway the following year.

Isobel’s feelings about these family tragedies are unknown, though she might at least have been relieved not to be in Scotland. Even so, she did not forget her kin across the sea and would work to muster troops and funds to send to Scotland in support of her brother's claim. She may also have been a positive influence on the proceedings at Inverness in 1312, where the Scots under her brother Robert I confirmed the Treaty of Perth, which had transferred the Western Isles to Scotland in 1266, with the Norwegians. This event is notable for being the first major diplomatic settlement achieved by Robert the Bruce and it is entirely plausible that his sister played a role as a mediator, though we unfortunately again we lack evidence. She is known to have communicated with Christian (who proved a redoubtable woman in her own right), after her sister's release in 1314, and several decades later the two ladies interceded with their nephew David II on behalf of at least one Norwegian merchant. In the end, of course, their brother Robert did become king of Scots in more than name, enjoying an unparalleled ascendancy in his final years. However Isobel’s only other surviving brother, Edward, was not quite so fortunate in his bid to become High King of Ireland, being killed in battle in 1318 and his corpse quartered. Isobel herself never returned to Scotland; nevertheless, she seems to have kept abreast of affairs there, and was certainly contact with the court of her nephew King David, while she maintained at least some some Scottish servants.

(Bergenhus fortress- this would have been the site of the major royal residence in Bergen during Isobel’s day. The hall on the left was built in the mid-thirteenth century during the reign of her husband’s grandfather Håkon IV- the same king famous in Scotland for his involvement in the Battle of Largs. The tower on the right incorporates the only other surviving mediaeval bit of the fortress, ‘the keep by the sea’, built in the 1270s by Magnus VI, and rebuilt into its present form in the sixteenth century by then governor Erik Rosenkrantz, employing Scottish workmen. Photo from wikimedia commons).

Meanwhile Isobel was busy in Norway. She continued to use her position as queen dowager to influence political affairs and remained on good terms with both Håkon V and, much later, his successor Magnus VII. The latter king was the son of Isobel’s niece, another Ingebjørg, one of the two daughters of King Håkon. In 1312, in a double wedding in Oslo, Isobel’s daughter Ingebjørg and her cousin of the same name married two younger brothers of the king of Sweden. Ingebjørg Håkonsdatter married the elder of the two, Erik the Duke of Södermanland (and other territories), while Ingebjørg Eiriksdatter married Valdemar, Duke of Finland, Uppland, and Öland. Isobel was present at the wedding and probably had a hand in organising the match, but her daughter’s marriage would not last long. The two Swedish princes had long been mistrusted by their elder brother King Birger, and eventually, in 1317, they were arrested at a banquet at Nyköping Castle and held in the dungeons until their suspicious deaths there sometime after January 1318, having possibly been starved to death. Their widows, the Duchesses Ingebjørg, did not simply roll over and accept this, however, and became the leaders of their husbands’ supporters, who in 1318 sent King Birger into exile in Denmark and crowned Magnus, the son of Ingebjørg Håkonsdatter, king of Sweden, while he succeeded his grandfather Håkon V as king of Norway in 1319. The regency was held by Magnus’ mother and grandmother, and Ingebjørg Eiriksdatter also held a seat on the regency council, though it is difficult to ascertain how much influence she actually wielded. We also have no evidence of her relationship with her mother Isobel, which again is very frustrating, but it is likely that Isobel followed the events in Sweden closely, and she would have been even more interested after Magnus VII became king of Norway too, as she remained on friendly terms with the new king.

Most notably, Isobel was heavily involved in the promotion of religious activity in Bergen. In 1305, she attended the consecration of Arne Sigurdsson as bishop of Bergen, an important public occasion at which King Hakon and Queen Eufemia were also present. Whether she was also present in 1301 for the execution of the ‘false Margaret’- a woman who had claimed to be the late Maid of Norway and who inspired a small martyr cult- is unknown, though her strong association with both Bergen and Orkney would have meant that she was well acquainted with the details. In 1324 Bishop Arne’s brother and successor, Audfinn Sigurdsson gifted her several religious houses in Holmen, in return for her donations and patronage of the Church in Bergen. She continued to be associated with the bishops of Bergen in other ways- for example, in 1339, when Isobel and Bishop Haakon Erlingsson successfully interceded with King Magnus on behalf of a prisoner, and the two seem to have worked together politically on other occasions. Religious patronage was often an important part of queenship, but surviving records indicate that Isobel was particularly active in Bergen during her widowhood, and had a strong relationship with the city’s bishops.

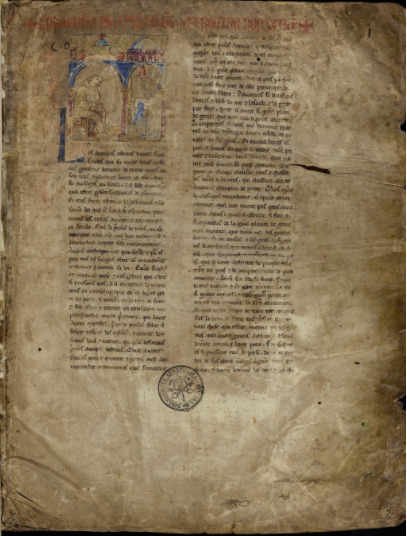

(Above: the first folio from an Old French version of William of Tyre’s “Historia rerum in partibus transmarinis gestarum”, which belonged to Isobel Bruce, and the ex libris announcing her ownership is in red ink across the top of the page. Below: one of the illuminations from the Ms. See here for more of the book.)

Although the church in Bergen where she was buried no longer stands, one particularly fascinating object associated with Isobel has luckily survived the centuries- a manuscript known as Bibliotheca Apostolica Vaticana Pal. Lat. 1963, which contains an Old French translation of William of Tyre’s “Historia rerum in partibus transmarinis gestarum”. This was a crusading chronicle and history of the kingdom of Jerusalem written in the twelfth century, originally in Latin, whose Old French translation became particularly popular in western Europe in the thirteenth century. The version which survives in Pal. Lat. 1963, however, is particularly interesting as it is the only work in French known to have been in Norway in its time period, and furthermore the manuscript itself appears to have been made in the middle east, probably in Antioch, thus raising many questions as to how it ended up in Norway (various Scottish, English, French, Norwegian, and ecclesiastical routes have been theorised, see the article in sources for more). We can be certain that it belonged to Isobel at some point however, as on the first and last folios, the words “Liber Domine Isabelle, Dei gratia Regina Norwegie” are clearly printed in red.

It is unclear what conclusions we can draw about her literary interests from her possession of this book, though Isobel might have had many reasons to be interested in William of Tyre’s chronicle- her father and grandfather are both supposed to have gone on crusade, while it was famously her brother Robert Bruce’s ambition to lead a crusade himself, thus Isobel came from a family with a strong interest in crusade and it is not impossible that this interest was shared by daughters as well as sons. The Norwegians also had their own crusading tradition, most notably during the First Crusade, which is the conflict primarily dealt with in William of Tyre’s history. Even if we cannot be sure that the subject matter reflects Isobel’s personal interests, an indication that at least one of the book’s readers had an interest in Scottish affairs is evident from a piece of thirteenth century marginalia on folio 78vb. Written in French, this is inserted next to a passage which gives a list of various kings (including of England and France) who were on the throne when Jerusalem was captured in the First Crusade in 1099, and adds, ‘et en escoce le bon Roy David le p’mier de ce nom’ (loosely, ‘and in Scotland the good king David the first of this name’). In fact David I did not succeed to the Scottish throne until 1124, but despite this mistake it is interesting that at some point someone reading the manuscript- whether Isobel or perhaps someone associated with her- felt it important to add some Scottish context to the events of this very precious book. (It is also worth noting that the Bruces derived their claim to the throne through their descent from David I’s youngest grandson, while Isobel’s nephew was to become David II). It is unclear if Isobel owned any more books- though given her spirituality and rank it’s entirely possible- and was never famed as a literary patron as her contemporary Queen Eufemia was, but the fact that this book survives offers a fascinating glimpse into the life and interests of an otherwise very shadowy queen.

Isobel lived a long life and she never remarried. Her daughter appears to have predeceased her, and though some sources indicate Ingebjørg may have had children, when she died in Sweden in 1357, Isobel was named as her heir under reversionary law. Around about the same time (1356/7) her similarly long-lived sister Christian died and was interred in Dunfermline, where Robert I was also buried. Isobel herself probably died in 1358, in Bergen. She was possibly in her eighties by then, and had outlived her husband by nearly sixty years. Though we know little about her, and her activity is often shadowy, it seems that she quite ably wielded influence as a queen, particularly as dowager, and her patronage may have been of importance to the careers of men like Weyland de Stiklaw, though often this influence and patronage was exercised discreetly. Her contribution to the histories of Scotland and Norway may have been small, and certainly less adventurous than that of her brother, but nonetheless her career throws up some interesting perspectives on the cultural links of Norway and Scotland, the role of women and queens, and the history of the Bruce dynasty.

*The calendar says the safe-conduct was issued in 1292, but I agree with Barrow that it’s probably misplaced and refers to the following year.

Selected references:

Regesta Norvegica- here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, and here (calendared not originals)

Calendar of Documents relating to Scotland, Vol. II

“Islandske Annaler Indtil 1578″, Gustav Storm.

“North Sea Kingdoms, North Sea Bureaucrat: A Royal Official Who Transcended National Boundaries”, Barbara E. Crawford in the Scottish Historical Review, 1990

“A Manuscript of the Old French William of Tyre (Pal. Lat. 1963) in Norway”, by Bjorn Bandlien

“Norwegian Foreign Policy and the Maid of Norway”, Knut Helle in the Scottish Historical Review, 1990

“Robert Bruce: King of Scots”, G.W.S. Barrow

I should also mention that Isabella Bruce has a chapter in “Eufemia: Oslos middelalderdronning” (ed.) Bjorn Bandlien, but the nearest library copy is in London so I was not able to consult it. However if I ever do get the chance I will update any of this as necessary. There were some other books I consulted as well but the above were the major sources.

#Isabel Bruce#Scottish history#British history#Bergen#mediaeval#norwegian history#Robert the Bruce#Eric II of Norway#Norway#people#Scots Abroad#Kings and Queens#women in history#thirteenth century#fourteenth century#Wars of Independence#Hakon V#north sea#House of Bruce#House of Sverre#literary culture#Books and treasures#queenship#illuminated manuscript#Language#clothing

60 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Aberdeen Scotland late 1940's /50's

Everything is so grey and stark. The only other colour is green

It’s easy to see how things could fall off the back of a lorry.

The quarry may be Rubislaw in Aberdeen. Some of the world’s best granite came from there, Caithness and Ailsa Craig. Ailsa Craig is an island, a volcanic plug. It’s a bird sanctuary now where the only granite is allowed to be taken is for curling stones only and there are limited allowances.

0 notes

Text

Shetland - Liv

Orkney - Bodil

Faroe - Ida

Iceland - Ari

Isle of Man - Erik

Caithness - Ailsa

Sutherland - Solveig

Greenland - Sia

Helluland - Anders

Markland - Aksel

Vinland - Dagny

*insert joke about how Norway got around during the Viking age*

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shetland: Wait, where's Ailsa? She loves Dungeons and Dragons.

Orkney: I thought Ida invited her.

Faroe: Well I thought Ari invited her.

Iceland: and I thought Sia invited her.

Greenland: and I never invited her.

#Ailsa is Caithness#aph shetland#hws shetland#aph orkney#hws orkney#aph faroe#hws faroe#aph iceland#hws iceland#aph greenland#hws greenland#aph Caithness#hws caithness#hetalia#hetalia incorrect quotes#aph nordics#hws nordics

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Norway: I hate to break this news, but, one of you is adopted.

Shetland: ...

Orkney: ...

Faroe Islands: ...

Iceland: ...

Caithness: ...

Greenland: ...

Iceland: Is it Ailsa?

Caithness: HEY-

#hws norway#hws shetland#hws orkney#hws faroe islands#hws iceland#hws caithness#hws greenland#hetalia#hetalia incorrect quotes#hetalia nordics

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Britannia's Children

Ireland - Molly (Hibernia)

Scotland - Angus (Caledonia)

Wales - Dylan (Rome)

England - William (Germania)

Grandchildren

Shetland - Fiona (Scotland)

Orkney - Bodil (Scotland)

Caithness - Ailsa (Scotland)

Canada - Matthieu (England [by adoption?])

USA - Alfred (England)

New Caledonia - Bruce (Scotland)

Australia - John (England)

New Zealand - William Jr. (England)

Northern Ireland - Fiachra (Ireland)

Sealand - Peter (England)

#hws britiannia#hws scotland#hws ireland#hws wales#hws england#hws canada#hws america#hws new caledonia#hws australia#hws new zealand#hetalia#hetalia hc#my hc#hws n. ireland#hws sealand

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Scandia's Children

Denmark - Njal (Germania)

Sweden - Björn (Germania)

Norway - Sigurd (Germania)

Grandchildren

Shetland - Fiona (Norway)

Orkney - Bodil (Norway)

Faroe - Ida (Norway)

Caithness - Ailsa (Noway)

Iceland - Ari (Norway)

Greenland - Aputsiak 'Sia' (Norway)

Vinland - Dagny (Norway)

Åland - Kirsi (Sweden)

Kalmar Union - Karl (Denmark)

New Sweden - Johan (Sweden)

Freetown Christiania - Benedikte (Denmark)

Ladonia - Arvid (Sweden)

#hws scandia#hws denmark#hws sweden#hws norway#hws shetland#hws orkney#hws faroe#hws caithness#hws iceland#hws greenland#hws vinland#hws åland#hws kalmar union#hws new sweden#hws christiania#hws ladonia#who let this woman have so many grandkids#hetalia#hetalia hc#my hc

16 notes

·

View notes

Note

who are Norway's kids?

Shetland - Fiona Orkney - Bodil Faroe - Ida Caithness - Ailsa Iceland - Ari Greenland - Aputsiak Vinland - Dagny (deceased)

They all have different human mothers, except for Shetland & Orkney who have the same mother; and Greenland who's mother was a Inuit personification.

As of modern day none of Norway's kids live with him, Shetland, Orkney, & Caithness live with Scotland. Faroe and Greenland live with Denmark; and Iceland is obviously independent.

#aph shetland#hws shetland#aph orkney#hws orkney#aph faroe islands#hws Faroe islands#aph caithness#hws caithness#aph iceland#hws iceland#aph greenland#hws greenland#aph vinland#hws vinland#hetalia#aph nordics#hws nordics#hetalia hc

14 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you have any hcs for other misc grandkids of Germania ?

Hey anon, sorry this has taken me 3 days. I wasn't sure exactly what you meant but this so I have not one, but two forms of answer for you.

Answer 1. All of Germania's grandkids (in age order, including human names, and parent [that is Germania's kid])

Shetland - Fiona (Norway)

Orkney - Bodil (Norway)

Faroe - Ida (Norway)

Caithness - Ailsa (Norway)

Iceland - Ari (Norway)

Greenland - Aputsiak 'Sia' (Norway)

Vinland - Dagny [deceased] (Norway)

Åland - Kirsi (Sweden)

Kalmar Union - Karl [deceased] (Denmark)

Canada - Mathieu (England)

USA - Alfred (England)

New Netherlands - Otto [deceased] (Netherlands)

New Sweden - Johan [deceased] (Sweden)

Liechtenstein - Liesl (Austria)

Australia - Jack (England)

Germany - Ludwig (Austria/Prussia)

Luxembourg - Henri (Belgium)

New Zealand - Liam (England)

Austria-Hungary - Edith [deceased] (Austria)

Sealand - Peter (England)

Freetown Christiania - Benedikte (Denmark)

Kugelmugel - Franz (Austria)

Ladonia - Arvid (Sweden)

(there are definitely more that could be in this list but for now they're who I have)

Answer 2. actual hc, about them interacting with each other.

Tbh its a good thing Germania isn't alive, bc sleepovers at grandpas would be insane with this group.

You know how with cousins there is absolutely the age gap groups? The group that gets to sit at the adult table first vs the group that's gonna be at the kids table for the next decade?

group 1 is Fiona to Dagny

group 2 is Mathieu to Liesl

group 3 is Jack to Edith

and group 4 is Peter to Arvid

Karl and Kirsi got to be their own group :p (too young for the viking age cousins, too old for the America's cousins (and brother))

they have a stupid tradition when they play board games at family reunions to leave 5 extra settings(?) for the game out.

They throw stuff at each other at UN meetings.

Half of them don't understand each other even if they're all speaking the same language. (Henri stopped trying to understand a single word from Jack years ago)

Because of travel and stuff they didn't see each other regularly until like 50 years ago.

Now they rarely go 2 months without a full blown get together.

Norways kids, so Fiona to Sia, claim absolute reign as the eldest kid :)

The elders have gotten in trouble multiple times for sneaking the youngers out

Benedikte technically only has one older sibling, and Karl is obviously not around anymore. So Norways kids are basically her surrogate siblings <3

Henri! is the only only child in the group! He's got only child habits! his cousins are hellbent on getting rid of those!

#I rlly hope the hc part made sense#it was a lot of rambles#aph shetland#hws shetland#aph Orkney#hws Orkney#aph Faroe islands#hws Faroe islands#aph caithness#hws caithness#aph iceland#hws iceland#aph greenland#hws greenland#aph vinland#hws vinland#aph åland#hws åland#aph kalmar union#hws kalmar union#aph canada#hws canada#aph america#hws america#aph new netherlands#hws new netherlands#aph new sweden#hws new sweden#aph Liechtenstein#hws liechtenstein

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Me: Never talks about my orkney oc, ever, all y'all know about her is that her name is Bodil.

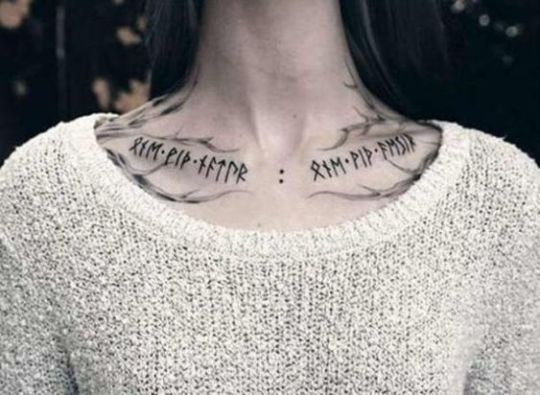

Me: anywho here are tattoos she has.

Bodil got the highland cow because Ailsa (Caithness) really wanted one but was scared to get it by herself <3

#aph orkney#hws orkney#I;m gonna ramble about her and shetland tonight#I've been thinking about them all day#hetalia#hetalia oc#hetalia hc#aph british isles#hws British isles#aph nordics#hws nordics#ig

5 notes

·

View notes