#Alexander weheliye

Text

The recognition of the suffering hasn’t really in any way mitigated the actual suffering. It’s just migrated onto different paths… And another thing is also only certain kinds of suffering are acknowledged… one has to present one’s suffering and oneself in a certain way in order to be recognized.

ALEXANDER WEHELIYE /// CLAIMING HUMANITY: A BLACK CRITIQUE OF THE CONCEPT OF BARE LIFE

#Alexander Weheliye#Funambulist#critical theory#black critical theory#I highly recommend the whole interview#Weheliye is absolutely excellent and on point as always#anyway i am obviously very much thinking about this in the context of palestine#the western demand for ‘proof’ of suffering followed by the complete refusal to mitigate it

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

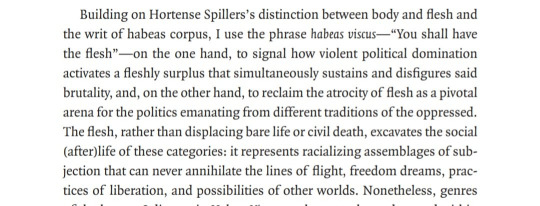

one of my favourite excerpts from alexander g. weheliye’s habeas viscus:

alt ID: Building on Hortense Spiller’s distinction between body and flesh and the write of habeas corpus, I use the phrase habeas viscus-- “you shall have the flesh”-- on the one hand, to signal how violent political domination activates a fleshy surplus that simultaneously sustains and disfigures said brutality, and, on the other hand, to reclaim the atrocity of flesh as a pivotal area fro the politics emanating from different traditions of the oppressed. The flesh, rather than displacing bare life or civil death, excavates the social (after)life of these categories: it represents racializing assemblages of subjection that can never annihilate lines of flight, freedom dreams, practices of liberation, and possibilities of other worlds.

#adventures in academia#critical theory#biopolitics#alexander g weheliye#habeas viscus#assemblage is kind of incomprehensible as a term (imo) so i tend to think of it as like a collection of actions that span the human#and nonhuman#also this book reads really nicely in relation to achille mbembe's necropolitics

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

going through some recent essays from e-flux Journal on intersections of gender and trans-ness with colonialism and imperial imaginaries (of music, architecture, geography). all can be read online:

"Hija de Perra: Writings from a Poor, Aspirational, Sudaca, Third World Perspective" by Julia Eilers Smitth (Journal Issue #140, November 2023)

"Anarcho-Ecstasy: Options for an Afri-Queer Becoming" by KJ Abudu (Journal Issue #139, October 2023)

"Sadistic Chola Manifesto" by Olga Rodriguez-Ulloa (Journal Issue #137, June 2023)

"Reluctantly Queer" by Akosua Adoma Owusu and Kwame Edwin Otu (Journal Issue #137, June 2023)

"Don't Take It Away: BlackFem Voices in Electronic Dance Music" by Alexander Ghedi Weheliye (theme issue "Black Rave", Journal Issue #132, December 2022)

"Dark Banjee Aesthetic: Hearing a Queer-of-Color Archive within Club Music" by Blair Black (theme issue "Black Rave", Journal Issue #132, December 2022)

"A Whale Unbothered: Theorizing the Ecosystem of the Ballroom Scene" by Julian Kevon Glover (theme issue "Black Rave", Journal Issue #132, December 2022)

"Editorial: Black Rave" by madison moore and McKenzie Wark (December 2022)

"Pasolini and the Queer Revolution in Beirut" by Raed Rafei (Journal Issue #126, April 2022)

"Inappropriate Gestures: Vogue in Three Acts of Appropriation" by Sabel Gavaldon (Journal Issue #122, November 2021)

"Taking the Fiction Out of Science Fiction: A Conversation about Indigenous Futurisms" by Grace Dillon and Pedro Neves Marques (Journal Issue #120, September 2021)

"Editorial: trans femme aesthetics" by McKenzie Wark (Journal Issue #117, April 2021)

"The Cis Gaze and Its Others (for Shola)" by McKenzie Wark (Journal Issue #117, April 2021)

"Our Own Words: Fem & Trans, Past & Future" by Rosza Daniel Lang/Levitsky (Journal Issue #117, April 2021)

"Post-genitalist Fantasies / Temporalities of Latin American Trans Art" by Kira Xonorika (Journal Issue #117, April 2021)

"S/pacific Islands: Some Reflections on Identity and Art in Contemporary Oceania" by Greg Dvorak (Journal Issue #112, October 2020)

"Capitalocene, Waste, Race, and Gender" by Françoise Vergès (Journal Issue #100, May 2019)

"Non-Aligned Extinctions: Slavery, Neo-Orientalism, and Queerness" by Ana Hoffner ex-Prvulovic (Journal Issue #97, February 2019)

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

https://www.miamiherald.com/news/local/education/article278582149.html

Tallahassee

When Florida rejected a new Advanced Placement course on African American Studies, state officials said they objected to the study of several concepts — like reparations, the Black Lives Matter movement and “queer theory.”

But the state did not say that in many instances, its reviewers also made objections in the state’s attempt to sanitize aspects of slavery and the plight of African Americans throughout history, according to a Miami Herald/Tampa Bay Times review of internal state comments.

For example, a lesson in the Advanced Placement course focused on how Europeans benefited from trading enslaved people and the materials enslaved laborers produced. The state objected to the content, saying the instructional approach “may lead to a viewpoint of an ‘oppressor vs. oppressed’ based solely on race or ethnicity.”

In another lesson about the beginnings of slavery, the course delved into how tens of thousands of enslaved Africans had been “removed from the continent to work on Portuguese-colonized Atlantic islands and in Europe” and how those “plantations became a model for slave-based economy in the Americans.”

READ MORE: DeSantis says AP African-American studies class was ‘pushing an agenda’

In response, the state raised concerns that the unit “may not address the internal slave trade/system within Africa” and that it “may only present one side of this issue and may not offer any opposing viewpoints or other perspectives on the subject.”

“There is no other perspective on slavery other than it was brutal,” said Mary Pattillo, a sociology professor and the department chair of Black Studies at Northwestern University. Pattillo is one of several scholars the Herald/Times interviewed during its review of the state’s comments about the AP African American Studies curriculum.

“It was exploitative, it dehumanized Black people, it expropriated their labor and wealth for generations to come. There is no other side to that in African American studies. If there’s another side, it may be in some other field. I don’t know what field that is because I would argue there is no other side to that in higher education,” Pattillo said.

Alexander Weheliye, African American studies professor at Brown University, said the evaluators’ comments on the units about slavery were a “complete distortion” and “whitewashing” of what happened historically.

“It’s really trying to go back to an earlier historical moment, where slavery was mainly depicted by white historians through a white perspective. So to say that the enslaved and the sister African nations and kingdoms and white colonizers and enslavers were the same really misrecognizes the fundamentals of the situation,” Weheliye said.

DeSantis’ efforts to transform education in Florida

The commentary is also an example of how Gov. Ron DeSantis has transformed the state’s education system in his quest to end what he calls “wokeism” and “liberal indoctrination” in schools — a fight that began in the aftermath of the pandemic and the Black Lives Matter movement that followed the high-profile murder of George Floyd at the hands of police in Minnesota.

“It’s not really about the course right? It’s kind of about putting down Black struggles for equality and freedom that have been going on for centuries at this point in time and making them into something that they are not through this kind of distorted rightist lens,” Weheliye said.

When asked about the findings of the previously unreported internal reviews, the Florida Department of Education said the course was rejected after state officials “found that several parts of the course were unsuitable for Florida students.”

Cailey Myers, a spokesperson for the agency, cited the work of many Black writers and scholars associated with the academic concepts of critical race theory, queerness and intersectionality — a term that she said “ranks people based on their race, wealth, gender and sexual orientation.” The term, however, refers to the way different social categorizations can interact with discrimination.

Brandi Waters, the executive director of the AP African American Studies course, said it is hard to understand the Florida Department of Education’s critiques on the content because state officials have not directly shared their internal reviews with the College Board. The state and the College Board, however, were in communication about the course for several months before it was rejected.

Waters maintains the coursework submitted to the state was the most holistic introduction to African American Studies.

A deeper look at Florida’s objections

The course materials provided by the College Board were reviewed by Florida Department of Education’s Bureau of Standards and Instructional Support and the decision to reject the course was made by “FDOE senior leadership,” records show.

John Duebel, the director of the state agency’s social studies department, and Kevin Hoeft, a former state agency official who now works at the New College of Florida in Sarasota, were identified as the two evaluators in the review. Hoeft is listed as an “expert consultant” to the Civics Alliance, a national conservative group that aims to focus social studies instruction in the Western canon and eliminate “woke” standards. His wife is a member of the conservative group Moms for Liberty.

Duebel declined to comment on the story and referred questions to the Department of Education, which did not respond. Hoeft did not respond to a request seeking comment. While the documents say that Duebel and Hoeft led the state reviews, much of the comments included in the state review are not attributed, making it hard to tell who said what.

The documents reviewed were provided to the Herald/Times by American Oversight, a left-leaning research organization that sued the state Department of Education for the records.

“We sued the Florida Department of Education to shed light on the DeSantis administration’s efforts to whitewash American history and turn classrooms into political battlegrounds,” American Oversight Deputy Executive Director Chioma Chukwu said in a statement. “The records obtained by American Oversight from Florida’s internal review of the AP African American Studies course expose the dangers of Gov. DeSantis’ sweeping changes to public education in Florida, including preventing students from learning history free from partisan spin.”

READ MORE: How a small, conservative Michigan college is helping DeSantis reshape education in Florida

The documents offer more detail into the state’s reasoning for rejecting the pilot course from being offered to high school students in Florida — and how topics related to racism, identity and gender were continually flagged out of concern that lessons were biased, misleading or “inappropriate” for students.

And, in cases where state officials did not find a violation of a state law or rule, concerns were often raised about how educators would teach the content, underscoring the growing distrust between state officials and educators as disputes over social issues engulf local school politics.

For example, the state worried educators teaching about how the 1960s Black is Beautiful movement helped lay a foundation for multicultural and ethnic studies movements, could “possibly teach that rejecting cultural assimilation, and promoting multiculturalism and ethnic studies are current worthy objectives for African Americans today.”

“This type of instruction tends to divide Americans rather than unify Americans around the universal principles in the Declaration of Independence,”the state officials wrote about a lesson in the course.

Records also show how some of the comments made by the state evaluators contained contradictions, such as advocating for primary sources and then later writing that certain primary sources contained “factual misrepresentations.” Many comments from the state pushed for the material to include perspectives from “the other side” but failed to elaborate whose perspective they wanted to be added.

Slavery

One of the lessons in the course, for example, set out to teach students how slavery set back Black people’s ability to build wealth.

“Enslaved African Americans had no wages to pass down to descendants, no legal right to accumulate property, and individual exceptions depended on their enslavers’ whims,” the College Board’s lesson plan said.

When reviewing the content, however, state reviewers said the lesson plan might violate state laws and rules because it “supposes that no slaves or their descendants accumulated any wealth.”

“This is not true and may be promoting the critical race theory idea of reparations,” state officials wrote in documents reviewed by the Herald/Times. “This topic presents one side of this issue and does not offer any opposing viewpoints or other perspectives on the subject.”

While there were scattered instances where enslaved people were given the chance to earn money to pay for their freedom, the wealth they accumulated still did not belong to them, said Paul Finkelman, the editor-in-chief of Oxford University Press’ “Encyclopedia of African American History 1619-1895.”

“Under the law of every slave state, including Florida, no slave could own anything. That is, slaves did not own the clothes on their back. They did not own the shoes on their feet,” said Finkelman. “So for the Florida Education Department to question whether slaves accumulated property is to not understand that slaves owned no property. In fact, they were property belonging to slave owners.”

Even in cases where slaves were allowed to make money, Finkelman argued, it would be a stretch to say they were able to accumulate wealth.

Black middle class

Evaluators also objected to a lesson plan that taught how Black Americans, even after slavery, continue to experience wealth disparities due to ongoing discrimination.

The coursework included the following statement: “Despite the growth of the Black middle class, substantial disparities in wealth along racial lines remain. Discrimination and racial disparities in housing and employment stemming from the early 20th century limited Black communities accumulation of generational wealth in the second half of the 20th century.”

State reviewers, however, said the unit could potentially violate state rules because it failed to offer other reasons outside of systemic racism and discrimination for the wealth disparity between Black Americans and other racial groups.

“The only required resource in this topic cites ‘systemic racism,’ ‘discrimination,’ ‘systemic barriers,’ ‘structural barriers,’ and ‘structural racism’ as a primary or significant causative factor explaining this disparity of wealth,” wrote one evaluator. “This topic appears to be one-sided as non-critical perspectives or competing opinions are cited to explain this wealth disparity.”

Pattillo said that while many of the comments made by the state in the review claimed that they wanted to see more balance of perspectives in the course materials, she felt state officials largely tried to minimize the topics of discrimination.

Abolitionist Movement

When it came to teaching students about the movement to end slavery, the College Board highlighted some of the prominent activists who led that abolitionist movement and the ways the government tried to stop those who resisted slavery.

“Due to the high number of African Americans who fled enslavement, Congress enacted the Fugitive Slave Acts of 1793 and 1850, authorizing local governments to legally kidnap and return escaped refugees to their enslavers,” the lesson plan stated.

Primary sources were scrutinized

When the College Board addressed the resistance to slavery, it wanted to teach students how to “describe the features of 19th-century radical resistance strategies promoted by Black activists to demand change.” In that unit, the state objected to two primary sources: “The Appeal” by David Walker and “An Address to the Slaves of the United States” by Henry Highland Garnet.

State reviewers said that “The Appeal” included “content prohibited under Florida law,” but does not offer more details; and that “An Address to the Slaves of the United States” contains “factual mis-representations” and potential violations of state rules.

“They complain that this primary source is not historically accurate. Well, of course it’s not historically accurate because it’s a political speech. It is not a piece of history, but it’s a perfectly historically accurate primary source to understand the anger of a Black abolitionist,” Finkelman said.

However, earlier in the review, the evaluators applauded the College Board for stating that “anchoring the AP course in primary sources fosters an evidence-based learning environment” and that the course will be focused on the works and documents of African American studies rather than “extraneous political opinions or perspectives.”

“This is exactly how all courses are to be taught in the state of Florida and we commend [the] College Board on this position,” wrote the state reviewer .

Scholars’ political leanings questioned

In one review, one of the state evaluators questioned the balance of the content because of the individuals the College Board picked to develop the coursework.

But one of the evaluators had a gripe: they claimed that there were no conservative Black scholars. This was a concern because, as the state evaluator put it, there may not be an “adequate level of intellectual balance.”

“Conservative and traditional liberal members may need to be added to the committees to bring balance and ensure compliance with Florida statutes, rules, and policies,” the state evaluator wrote.

Waters said the College Board is focused on having scholars on their committees who are the leaders in the field of African American studies and that their political background isn’t something they take into consideration.

“In terms of the scholars, we never really asked them ‘what is your political background?’,” Waters said. “I don’t assume that is a characteristic that remains static in a person’s life over time.”

“What we do is look for scholars who represent the expertise needed for the course. So who is leading the field in how we understand the origins of the African diaspora? Who is leading the field in cutting edge research on unearthing new perspectives of the civil rights movement? We look for their expertise and also the different backgrounds that they represent,” she added.

How did we get to this point?

While Florida law requires the study of African American history, the state reviews of the AP course show how the DeSantis administration and Republican policymakers are implementing changes to how schools can teach about race, slavery and other aspects of Black history.

In 2021, Florida barred lessons that deal with critical race theory, a 1980s legal concept that holds that racial disparities are systemic in the United States and not just a collection of individual prejudices. Critical race theory was not being taught in Florida schools. The state also barred lessons about “The 1619 Project,” a New York Times project that reexamines U.S. history by placing the consequences of slavery and contributions of Black Americans at the center.

A year later, the Republican-led Legislature approved a new law, known as the “Stop W.O.K.E. Act,” which prohibited instruction that could prompt students to feel discomfort about a historical event because of their race, ethnicity, sex or national origin.

To DeSantis, the restrictions are a necessary effort to protect students from what he sees as a cultural threat that, as he puts it, teaches “kids to hate this country.” But the policies have been widely criticized by Democrats, educators, historians and even a few Republican lawmakers who see the laws as an attempt to distort historic events.

State officials’ interpretation of these policies collided with many of the learning objectives outlined in the A.P. courses. This collision, some scholars say, is emblematic of the chilling effect the state’s vague laws can foster in academia.

“I think this is the point that many people have been saying,” Pattillo said. “That the misguided blanket use of this term critical race theory, and in the absence of some definition of what that means or what they think it means, makes any teaching of racism questionable per that vagueness...”

Based on the state reviews the Herald/Times provided to him, Finkelman said it appeared the state was “hunting for bias.”

“And if you hunt long enough, you can find bias anywhere,” Finkelman said, noting that “anyone can find faults, and even small mistakes with any scholarly enterprise.”

To do the job right, Finkelman said, the state should ensure the course is reviewed by historians, with expertise in the specific subject area — not political scientists or state bureaucrats. He questioned whether the state prioritized reviewers’ credentials after seeing the state’s comments on the topics of slavery, or subjects that took into account the issue of racism and identity.

Based on Finkelman’s review of the content, he said, the state reviewers were more interested in correcting content based on their reading of the material over “scholarly accuracy.”

Read more: Only 3 reviewers said Florida math textbooks violated CRT rules. Yet state rejected dozens

Since Florida rejected the pilot course in January, students in other parts of the country have been taking part in the pilot program. Education officials in only one other state — Arkansas — are disputing whether to make the AP course eligible for credit. The Arkansas Department of Education — led by Florida’s former K-12 Chancellor Jacob Oliva — recently removed the class from its course code listing.

In November, the College Board plans to submit the final version of the course’s curriculum for approval. But with Florida’s laws still in place, the fate of the course remains in limbo — and the outcome could potentially make Florida students in public high schools less likely to have access to the course. If approved, parents and students can choose to enroll in the course.

College Board officials are aware of this possibility, but remain hopeful.

“We certainly hope that Florida students will have the opportunity to take this course,” said Holly Stepp, a spokesperson with the College Board.

Myers, the Florida Department of Education spokesperson, said the College Board is welcome to resubmit the course for review in November.

But, Myers said, “at this point, it is inappropriate to comment on what the future could hold – it is just speculation.”

This story was originally published August 29, 2023, 5:30 AM.

#florida#white washing history#Black Lives Matter#Black History Matters#ron desatan#white lies#florida department of education#florida students

117 notes

·

View notes

Text

Florida reviewers of AP African American Studies sought ‘opposing viewpoints’ of slavery

This excellent article from the Miami Herald, looks at some of the previously unreported objections Florida had to the AP African American Studies course.

“It’s not really about the course right? It’s kind of about putting down Black struggles for equality and freedom that have been going on for centuries at this point in time and making them into something that they are not through this kind of distorted rightist lens."

--Alexander Weheliye, African American studies professor, Brown University

When Florida rejected a new Advanced Placement course on African American Studies, state officials said they objected to the study of several concepts — like reparations, the Black Lives Matter movement and “queer theory.”

But the state did not say that in many instances, its reviewers also made objections in the state’s attempt to sanitize aspects of slavery and the plight of African Americans throughout history, according to a Miami Herald/Tampa Bay Times review of internal state comments.

For example, a lesson in the Advanced Placement course focused on how Europeans benefited from trading enslaved people and the materials enslaved laborers produced. The state objected to the content, saying the instructional approach “may lead to a viewpoint of an ‘oppressor vs. oppressed’ based solely on race or ethnicity.”

In another lesson about the beginnings of slavery, the course delved into how tens of thousands of enslaved Africans had been “removed from the continent to work on Portuguese-colonized Atlantic islands and in Europe” and how those “plantations became a model for slave-based economy in the Americans.”

In response, the state raised concerns that the unit “may not address the internal slave trade/system within Africa” and that it “may only present one side of this issue and may not offer any opposing viewpoints or other perspectives on the subject.”

“There is no other perspective on slavery other than it was brutal,” said Mary Pattillo, a sociology professor and the department chair of Black Studies at Northwestern University. Pattillo is one of several scholars the Herald/Times interviewed during its review of the state’s comments about the AP African American Studies curriculum.

“It was exploitative, it dehumanized Black people, it expropriated their labor and wealth for generations to come. There is no other side to that in African American studies. If there’s another side, it may be in some other field. I don’t know what field that is because I would argue there is no other side to that in higher education,” Pattillo said.

Alexander Weheliye, African American studies professor at Brown University, said the evaluators’ comments on the units about slavery were a “complete distortion” and “whitewashing” of what happened historically.

“It’s really trying to go back to an earlier historical moment, where slavery was mainly depicted by white historians through a white perspective. So to say that the enslaved and the sister African nations and kingdoms and white colonizers and enslavers were the same really misrecognizes the fundamentals of the situation,” Weheliye said.

[emphasis added]

The entire article is well worth reading, and I encourage people to do so.

80 notes

·

View notes

Text

Book review -- Monstrous Intimacies

There are a great many ways to know chattel slavery. The worst cast slavery in terms of violations against humans' rights while simultaneously positioning it as opaque and unthinkable, a doubled label that renders Black trauma and survival raw material for mobilizations against 'wage slavery,' 'white slavery,' and other issues considered pressing to the white population. Alternatively, scholars like Charles Mills and Alexander Ghedi Weheliye have analyzed chattel slavery and the mid-Atlantic slave trade as institutions of utter dehumanization. Chattel slavery is a social death, a cutting of people from society via the 'largest forced transfer of people in the history of the world,' an institution built around moving enslaved people so far from home that they had nowhere to run. Chattel slavery created race as we know it, and it made 'human' as we know it through an Enlightenment humanism that prefigured Black people as categorically inhuman. This makes framing slavery as the violation of a human's rights seem inadequate, because despite modern attempts at inclusion, 'human' was something that was never intended to include enslaved people.

But while there's something clear to the way that blackness is foundationally positioned as against the category of human, it's not sufficient to describe the social dynamics of slavery and its aftermath. As Hartman notes in Scenes of Subjection, there are "qualities of affect distinctive to the economy of slavery," patterns of empathy and ambivalent joy which intensify subjection. We return from utter abjection to a horribly ambivalent state, and the question now becomes: how do we consider affect without implicitly positioning it as a reprieve from, or existing outside, the violence and subjection of slavery? The public/private // male/female dyad of Anglo-American gender renders emotion, intimacy, and desire as categorically outside power relations, and even efforts to break this distinction and 'make the personal political' often frame power (typically only patriarchal power) as a sort of infection into the pure world of feeling. In Monstrous Intimacies, Sharpe makes a significantly stronger effort to this end, considering the 'double status' of subjectification, the ways that enslaved people were both humanized and dehumanized, often in contradictory ways, leading to certain conditions of 'relative freedom within unfreedom.' Her eponymous monstrous intimacies mark the ways that "slavery and the Middle Passage were ruptures with and a suspension of the known world that initiated enormous and ongoing psychic, temporal, and bodily breaches," which, combined with the white domestic domination of enslaved people, yielded intimate brutalities which continue to structure post-slavery life.

Sharpe starts with amalgamation, incest, and the ways the two were rendered as one under various legal codes. She argues that this collapse was "one nodal point around which subjectivity in the New World was reorganized and around which it cohered;" that is, interracial relationships were considered along the same lines as incestuous ones due to the subjectification of enslaved people. There's one clear material reason for this: because of the systemic rape of enslaved women by white enslavers, and because of the intergenerational nature of chattel slavery, the two taboos became one. Sharpe lays out these monstrous intimacies through a review of the letters of James Henry Hammond and a close reading of Corregidora, a novel which follows Ursa Corregidora and her family's history with, and efforts to reckon with, their monstrous intimacies with Corregidora during and after slavery. In both cases, Sharpe looks at Black subjectivity not in spite of, but in part through the horrific emotion and empathy of white slaveowners, and the ambivalent effort to survive through it and build something after the end of slavery.

This first chapter establishes the frame of monstrous intimacies through perhaps its most vivid example, showing, through Corregidora, the strange ambivalence that squats inside these horrific acts of subjectification. Now that this monstrosity is established, she's free to move to yet more ambivalent acts of emotion. The second chapter explores the intimacies of Black liminality, the ways that blackness has been utilized in the US and Europe to define the 'edge' of human and object through the rhetorical use of people like Saartje Baartman. Sharpe argues that "In much (white) South African writing the Bushman (KhoiSan), the mulatto, and the so-called coloured in apartheid’s racial nomenclature were each, individually and at times interchangeably, figures of monstrosity" -- that is, different ethnic groups in South Africa were often differently instrumentalized as boundary objects in a similar manner to Baartman. Sharpe takes Maru as the object of study in the latter part of the chapter, and she discusses the ways that its protagonist stands as a sort of living impossibility.

The third chapter's excellent. This is the clearest analysis of S/M and slavery that I've ever seen, and Sharpe works very clearly between different critics without falling into the disavow etc. trap -- not that describing rightness is /bad/, but Sharpe uses the ambivalence she's built over the first two chapters excellently to talk about something she could probably never navigate readers through if this chapter had been at the start of the book. This feels like a climax (ha), and it manages to do it without spectacularizing or isolating S/M -- in fact, the interweaving of S/M and the monstrous intimacies of slavery serves to despectacularize S/M itself -- the current is pushing in the other direction! This is what's so fascinating about reading Sharpe. She's clearly in Hartman's tradition, and has gotten incredibly good at pushing on different forms of spectacularization and narrativization in ways that make them paradoxically cancel out -- or maybe the tools she's developed to despectacularize Black subjectivity just apply really well to sexual spectacle? Either way, this is the best analysis I've seen of S/M in general, and I don't think that's a coincidence.

The last chapter's alright. I am not an art person, but it really felt like Sharpe was trying to draw water from a stone. The section seemed as much about the reactions to the art, and about trying to rescue the artist as anything else -- which I am all for, but I'm also not inseparably invested in what Sharpe's saying here. I think the best comparison is to chapter 3 -- Sharpe seems to be using these tools to tackle more and more spectacular portrayals, but at this point it feels like the spectacle is devouring everything else. Unlike chapter 3, there's not a ton of analysis of the media itself. I think this is maybe overshooting the performativity/materiality balance here?

The book in general is very good; seems like a natural inheritor of Hartman's work, or at least she's thinking the same interesting things, or maybe this is more widespread and I haven't read it yet. It seems like Sharpe broke further away in The Wake. Chapters 1 and 3 I like and feel like I understand; Chapter 2 has more I'm missing, I think, and I like what I have already. 4 is mediocre. The book starts very strong and keeps adding, though, and I felt like everything intro through 3 was building on itself and saying new and potent things, which is pretty uncommon for books. This is very dense, and very focused, dense not because it's saying a wide range of things, but because it really takes a few good pieces for everything they have.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

As Pal Ahluwalia and Robert Young among others have shown, the Algerian war in particular, and decolonization in general, provided the impetus for a generation of French intellectuals (Jacques Derrida, Pierre Bourdieu, Hélène Cixous, and Jean-François Lyotard, for example, who would later be associated with post-structuralism), to dismantle western thought and subjectivity. The nearly simultaneous eruptions of ethnic studies and post-structuralism in the American university system have been noted by critics such as Hortense Spillers and Wlad Godzich, yet these important convergences hardly register on the radar of mainstream debates. That is to say that the challenges posed to the smooth operations of western Man since the 1960s by continental thought and minority disclosure, though historically, conceptually, institutionally, and politically relational, tend to be segregated, because minority discourses seemingly cannot inhabit the space of proper theoretical reflection, which is why thinkers such as Foucault and Agamben need not reference the long traditions of thought in this domain that are directly relevant to biopolitics and bare life.

-- Alexander Weheliye, Habeas Viscus

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Replacing the designation black with African American signals foremost a turn away from a primarily political category toward an identitarian marker of cultural and/or ethnic specificity; diaspora suggests a concurrent de-emphasizing of specificities in the embrace of transnational frames of reference and a return of said particularities via the comparison of black populations that differ in nationality.

Alexander Weheliye, Habeas Viscus

0 notes

Quote

We are in dire need of alternatives to the legal conception of personhood that dominates our world, and, in addition, to not lose sight of what remains outside the law, what the law cannot capture, what it cannot magically transform into the fantastic form of property ownership.

Alexander Weheliye, “Habeas Viscus”

1 note

·

View note

Link

My new article, in Political Theory. The abstract:

What would it mean to take antiblackness seriously in theories of biopolitics? How would our understanding of biopolitics change if antiblack racialization and slavery were understood as the paradigmatic expression of biopolitical violence? This essay thinks through the significance of black studies scholarship for disentangling biopolitics’ paradoxes and dilemmas. I argue that only by situating antiblackness as constitutive of modernity and of modern biopolitics can we begin to meet the theoretical and political challenges posed by biopolitics. While Roberto Esposito formulates some of the most important questions about biopolitics, his responses will always be insufficient insofar as he engages in no discussion of blackness, antiblackness, slavery, white supremacy, or the role of sociopolitical processes of racialization, violence, and domination. I move from a critique of Esposito to explore the modernity-making processes of the imbrication of antiblackness and biopolitics. To do so, I analyze the biopolitics of birth and of flesh, and interrogate the (im)possibility of an affirmative biopolitics. Ultimately, the essay argues that theories of biopolitics can be genuinely critical only to the extent that they center antiblackness.

#political theory#biopolitics#roberto esposito#modernity#antiblackness#slavery#afro-pessimism#hortense spillers#alexander weheliye#jared sexton#frank wilderson

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

When all of it actually is important...

0 notes

Quote

Because black suffering figures in the domain of the mundane, it refuses the idiom of exception.

from Habeas Viscus: Racializing Assemblages, Biopolitics, and Black Feminist Theories of the Human by Alexander G. Weheliye

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

Overview

This project was inspired by and drew from Alexander Weheliye’s Habeas Viscus, Hortense J. Spillers “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe: An American Grammar Book” (1987) and Sylvia Wynter’s “‘No Humans Involved’: An Open Letter to My Colleagues” (1994) in connection to the Black woman’s body through time and space in conjunction with “Fragment of a Queen’s Face,” a figure in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (The Met) in New York.

Theory I: Flesh and Fragment

Theory I is an epistolary to “The Fragment of a Queen’s Face.” The figure was made from yellow jasper during the Amarna Period (ca.1353-1336) during the reign of Pharaoh Akhenaten in the late 18th Dynasty. The most significant feature of the figure is that more half of the head is missing and only the lips are visible. In the letter, I use personal history and connect various works that articulate historical and sociopolitical views of the Black female body.

The Visits describes my first visit and subsequent returns to the “Queen’s Face” and my affinity to the figure. Decoding the Hieroglyphics features theoretical groundings of how the “Queen” came to be. #SayHerName challenges the silence about the violence experienced by Black women throughout history. The Killmonger in Me discusses the role Black women in science and cultural institutions. The Riddle connects the past to the present. P.S. The Ties that Bond makes universal connections.

The Visits

I first met you when I was 16. As an US History assignment, I had to visit cultural institutions and landmarks around New York City including The Met. When we got there, my home girl and I headed towards the Ancient Egyptian section. I was in awe of all the artifacts. Out of them all, I was most intrigued by your warm and welcoming polished yellow jasper. I was looking at half of you, yet you still seemed complete. I had never seen anything like you. Your label read, “Fragment of a Queen’s Face.” Who were you and why do you look foreign yet familiar? We circled the museum and bounced, but since then I have always returned to see you. When I was bored, when I broke up with him, when I started college, when I wanted to escape New York without leaving the city—it was a no-brainer, all I needed was a MetroCard and time.

I have since wondered about how you were damaged: who damaged you? Why do I feel such an affinity with you? The damage done aligns with the history of removing noses is hardly a coincidence. The fracture right above your cupid’s bow looks like whoever struck you was trying to destroy your nose and ended up taking off most of your head. However, I see the attention to detail that went into creating you. Your smile line, the creases in your neck…You were loved. Your plaque reads: She cannot be securely identified with certainty.

The Met speculates that you are either Queen Nefertari or Kiya. The museum also gives possible reasons for what happened to you, among them a territorial conquest, but after looking up other the images and figures of Nefertari and Kiya—some of their noses are missing as well. Apparently, when the artists created their works with wide noses, they were likely to be destroyed.

In November of 2017, I needed to escape and decided to pay you a visit, but this time was different. My knowledge of the Black experience had grown exponentially, now you weren’t just a face of curiosity. In my naiveté, I was a bit voyeuristic; now I looked and thought of you critically. Without words and sealed lips, you began to tell a story. I listened with my eyes.

She cannot be securely identified with certainty.

Decoding the Hieroglyphics

hieroglyph, n.

1.

a. A hieroglyphic character; a figure of some object, as a tree, animal, etc., standing for a word (or, afterwards, in some cases, a syllable or sound), and forming an element of a species of writing found on ancient Egyptian monuments and records; thence extended to such figures similarly used in the writing of other races. Also, a writing consisting of characters of this kind.

2.

a. transf. and fig. A figure, device, or sign having some hidden meaning; a secret or enigmatical symbol; an emblem.

b. humorously. A piece of writing difficult to decipher.

3. One who makes hieroglyphic inscriptions. Rare.

A few ways that we identify people is by how they look (from their physical appearance to their fashion statements), the way they speak (soda vs. pop) and their name (Hayashi vs. Hernandez). This is not perfect because it is always an incomplete picture. I state this because somewhere along my life journey, I learned how looters and destroyers—who called themselves archaeologists, soldiers, historians, geographers, and the likes—visited Egypt and did as they pleased. Their colonial practices excavated and disrupted histories and legacies in the name of research, imperialism and culture. Despite the great cultural history here, ankhs as a symbol of religion and wide noses, signifying Blackness, were damaged and destroyed.

“I would make a distinction in this case between ‘body’ and ‘flesh’ and impose that distinction as the central one between captive and liberated subject-positions. In that sense, before the ‘body’ there is the ‘flesh,’ that zero degree of social conceptualization that does not escape concealment under the brush of discourse, or the reflexes of iconography.” (Spillers, 1987: p.67)

By highlighting the works of Hortense Spillers and Sylvia Wynter, Alexander Weheliye (2014) argue that racial assemblages—humans, not-quite humans and non-humans—determine differentiation and hierarchy of races through sociopolitical processes. Using the term habeas viscus (you shall have the flesh), Weheliye relies on Spillers’ distinction between the flesh and the body along with the writ habeas corpus (you shall have the body) to examine the “breaks, crevices, movements, languages and such zones between the flesh and the law” (p. 11).

I decided to look at Spillers’ (1987) and Wynter’s (1994) work and how they examine language in relationship to the violence against Black bodies. In reference to the violence committed against Black bodies during slavery, Spillers (1987) argues that flesh tells the narrative of the body and when it came to physical trauma—breaks, fractures, brandings, punctures, missing parts, etc.—the body kept score. This is what Spillers called the hieroglyphics of the flesh.

According to Spillers, the hieroglyphics of the flesh is not just the violence committed against the Black body, like the “chokecherry tree” on Sethe’s back in Toni Morrison’s Beloved, but the flesh itself as a marker for racial violence no matter the institution whether scientific, social, political, educational or economic, it is the color of the flesh, which determines if and what kind of violence is inflicted on someone (Spillers, 1987). For example, the impact of mass incarceration on the Black and Latino communities versus white communities. Blacks and Latinos get harsher sentences than their white counterparts simply because they are not white.

Wynter’s and Spillers’ work overlaps when they discuss “captivity.” Spillers writes about the “captive body” while Wynter references James Baldwin’s term “captive population” which describes how Black lives are viewed and how we are a nation within a nation (Baldwin, 1968/2017). From these captivities emerge questions surrounding the value of captive lives and how they communicate our truths and what happens when we refuse the hegemonic “truth.”

“A riot is the language of the unheard.” Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

When discussing the rhetoric of the hegemonic “truth,” Wynter (1994) calls out grammarians, the scholars (gatekeepers) who over centuries have perpetually reproduced gender and racial inequities through their literature. Wynter argued that rhetoric in the Humanities and the Social Sciences creates and maintains a caste system of racial hierarchy where whites are on top (dominant) and Blacks on the bottom (inferior). However, grammarians, who can identify as any gender or race, erase race and codify racialized language using economic and geographical terms such as “middle class suburbia” to mean white and “inner city poor and jobless” to equal young Black males (Wynter, 1994). Of course, there are exceptions to who is being identified and discussed within these categories, as previously mentioned, but for the most part, this framing of language conceals the racial oppression and the “hidden cost” of “subjective understanding” (pg. 60).

I wanted to argue about “today’s world,” but truthfully the hidden cost has always been a thing post-1492. In Spillers’ analysis about the “truth” value of the words that represent race, she wrote “We might concede, at the very least, that sticks and bricks might break our bones, but words will most certainly kill us (p. 68).”

You not only have markings, but part of you is missing. Was someone clumsy or was it a violent sociopolitical process used to maintain hierarchy? If those who committed this act against you were rivals during ancient times, why didn’t they just break you down to rubble? What purpose does keeping half of a face serve? We know the natives used to go in and steal gold and things that bling bling. You’re not that. Or maybe your lips weren’t destroyed because they thought no one would listen to what you had to say? I study your fractures again, especially the groove above your cupid’s bow…

The Met can keep their postulations. I’m wiser now.

She cannot be securely identified with certainty.

#SayHerName

While looking at you, Sarah Baartman (1789-1815) came to mind. Of course there is a huge difference between the exploited life of a Black woman and the exploited life of statue of a Black woman, but parallels are present. Born approximately 4,000 miles south from where you were on the same continent, Sarah Baartman was called a “freak” and was used for “science and spectacle” because of her large buttocks (McKittrick, 2010 p. 117). Enslaved people were commonly being used for medical research without any ethical consideration (Spillers, 1987). Sarah Baartman was no different because her body was used to explain inherent Black inferiority. As McKittrick (2010) argued:

“…across time and space, and sometimes across race, Baartman is the analytical template through which racist pornography, the grotesque, and the lewd seduction of black female popular-culture figures can be understood in relation to a history of racial imprisonment, bodily dismemberment, sexism, and white supremacy.” (p. 118)

I sat with that. In between those lines is a patriarchal component that we, as Black women, sometimes unconsciously privilege before our own lives: the lives of our brothers. Sometimes we don’t think or know how to articulate the violence inflicted on us (Love, 2017). I think of my brothers safety in this world knowing that I am just as vulnerable. Not until the last two years, did I center the violence inflicted on me because that is the way the world turns and I have things to get done….until one day it caught up to me. I began to do a survey of my spirit injuries—more than I thought—and some were unrecognizable, a hieroglyph. I guess I should consider myself lucky because I know what needs healing while many others don’t and/or can’t. Adrien Katherine Wing argues that if there are many injuries it results into a what Williams calls a “spirits murder” (1990).

Then there is the actual murdering of Black (trans)women and the lack of recognition when she has taken her last breath at the hands of the state. Things are starting to change with social media platforms like Twitter, to share our sisters’ stories. Think tanks such as African American Policy Forum (Crenshaw, Ritchie, Anspach, Gilmer, Harris, 2015) and sites like Black Perspective that make sure these women are not erased. The margins in which these stories reside are now disrupting the mainstream. We are learning their stories, honoring their lives, finally having these conversations and saying their names…

#ShantelDavis #MyaHall #KendraJames #LaTanyaHaggerty #FrankiePerkins #KathrynJohnson #DanetteDaniels #AlbertaSpruill #EleanorBumpurs #MargaretMitchell #ShellyFrey #YuvetteHenderson #KaylaMoore #TanishaAnderson #ShereeseFrancis #MichelleCusseaux #KyamLivingson #ShenequeProctor #RekiaBoyd #AiyannaJones #TarikaWilson #AuraRosser #JanishaFonville #NewJersey4 #YvetteSmith #FrankiePerkins #KathrynJohnson #DanetteDaniels #AlbertaSpruill #DuannaJohnson #NizahMorris #IslanNettles #RosannMiller #SonjiTaylor #MalaikaBrooks #DeniseStewart #ConstanceGraham #PatriciaHartley #KorrynGaines #AlteriaWoods #CharleenaLyles #MorganRankins #CariannHithon

The Killmonger in Me

After Baartman’s death in 1815, her body was dismembered and placed in the Museum of Natural History in Paris until 2002. You, Queen, were “gifted” to the Met in 1926…The year my favorite girl was born…In Black Panther, when Killmonger stared at the mask with intrigue and Ulysses Klause asked if it was from Wakanda, Killmonger replied, “Nah. I’m just feeling it.” Killmonger wasn’t just “feeling it.” The connection is much deeper than that. N’Jadaka (Killmonger) saw something in that Igbo mask. There was an affinity; a connection. I thought of our relationship, me and your fragmented face. I am not a psychoanalyst, but I know a lil’ sumthin’ sumthin’. For me, we are both fragments of a disjointed story. Our story.

Killmonger effortlessly challenges the history of artifacts placed in the museum. “How do you think your ancestors got these? Do you think they paid a fair price? Or did they take it…like they took everything else?” Art reflecting life.

Killmonger later states, “You got all this security in here watching me since I walked in…” He is addressing the surveillance of the Black body which determines the imprisonment, dismemberment and sexist cataloguing the body is to undergo (McKittrick, 2010; Spillers, 1987). As I write this there has been a surge of videos in where white people are calling the police because of the mere presence of Black people, which demonstrates the criminalization that follows the Black body in different spaces Anderson (2004) and the non-police surveillance of Black bodies (Dancy, Edwards and Davis, 2018).

Your life in a glass case is for the white gaze. You weren’t initially placed there for me to learn about my history. Of course, some could argue that if you weren’t brought to the museum, how would I get to see you. To that I say, if my ancestors and their artifacts weren’t brought over here, there wouldn’t be anything to debate. Therefore, I will need the colonizer and their pigmented minions to stay silent on the matter.

Speaking of pigmented minions, on May 25, 2018 at approximately 3:30pm, Mike and I went to the Met and I was showing him another sculpture with a missing nose and as I was raising my hand to its’ face, a security guard standing by the partition of your gallery and Gallery 119 yells at me, “Don’t touch!” My back was turned so I don’t know how long she was watching me, but clearly she had her eyes on me. I finessed a clapback that let her know I’m not the one without getting kicked out. She tried it.

Anyways, you’re made of jasper, a semi-precious stone which is a six and half to a seven on the Mohs scale of mineral hardness. Jasper can be harder than steel depending on the composition and when broken has a conchoidal fracture. Your impeccable smoothness and detail may have confused a perpetrator into thinking that you were actually weaker than you looked. Perhaps thinking you were going to break like granite, which was used for many of the figures. I think of all the Black women who have endured so much, but you wouldn’t know by looking at them. Even if you can see it, they are still standing despite the violence committed against them.

She cannot be securely identified with certainty.

The Riddle

Another movie filmed in a museum came to mind…when I was a little girl, I used to watch Don’t Eat the Pictures: Sesame Street at the Metropolitan Museum of Art all the time. Long story short, in the movie, a young Ancient Egyptian prince, Sahu or the “hidden one”, was trapped in the Met until he met two criteria: to answer the riddle, “Where does today meet yesterday?,” and his heart had to be lighter than a feather. If he fulfilled the requirements, he would reunite with his family as a star in the sky. The Sesame Street gang was also locked in and tried to help Sahu.

As the night went on, Big Bird and Snuffleupagus kept thinking of the answer. Finally, Big Bird figured out the answer: a museum. He also negotiated the weight of Sahu heart that was heavier than a feather because he missed his family. In the end, Sahu was able to reconnect with his family. That was real cut and dry, but my point is, like the riddle, you are part of my history and I am part of your future and we met at a museum; where today meets yesterday.

She cannot be securely identified with certainty.

P.S…The ties that Bond

“Words are a pretext. It is the inner bond that draws one person to another, not words.” Rumi

I started to grow impatient with this project because I started it in the fall of 2018; the seasons changed, life and death happened. Black Panther and Everything is Love were released. I continued to learn about Black women, #Blackgirlmagic, Black Feminist Theory, Black Girls Rock!, Professional Black Girls, the ways in which Black women heal, the ways in which we love, and most importantly, our different survival mechanisms. We have survived a lot (shout out to Lorde and Gumbs).

I also realized that the universe is in concert, seeing N’Jadaka (Killmonger) in the museum scene staring at that Igbo mask gave me goosebumps. When I saw Beyonce at Coachella donned in Ancient Egyptian garb, it motivated me to step up and complete this project despite my demanding priorities and Murphy’s Law. Beverly Bond’s book, Black Girls Rock!, is filled with the narratives of Black women, young and old for us to embrace each other and to tell our stories. Then the Carters dropped Everything Is Love and their visual for “Apeshit” in the Louvre (the Met of Paris); lyrical references “I will never let you shoot the nose off my Pharaoh” and a nod to Prince’s Purple Rain (a project I completed, but not ready to share with the world) in “Black Effect”; “Black queen, you rescued us, you rescued us, rescued us” on “713” and; how can I forget the mature Jamaican woman explaining love and laughing. I realized we are all telling stories of Black women, Black experience. No matter where you get the message from the story will be told through the screen, audio and text whether in print or digital format. Kruger, Bond, The Carters…and people like me. We were all telling these stories in our own way. (Shout out to the homies, Kia Perry and EbonyJanice!)

Of all the bonds connected to this work, this is in honor of my grandmother, aka My Favorite Girl and my shweeheart. The woman who only had a third grade education, but a Ph.D. in Life from the School of Hard Knocks. The woman whose heart was bigger than her body and had a warrior spirit. In honor of her strength, her courage, her sense of humor (because sometimes you can’t do anything, but laugh) and her undying love. Although she is no longer here physically, her prayers, love and lessons still with me. Every once in awhile a lesson whispers in my ear. As I was making final edits, I heard: Nothing is due before its’ time. I miss you and thank you.

Sources

Anderson, E. (2004). The Cosmopolitan Canopy. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 595, 14-31.

Baldwin J. (1968/2017) “Captive population.” Esquire.

Crenshaw, K. Ritchie, A., Anspach, R., Gilmer, R., Harris. L., (2015). “Say her name: Resisting police brutality against Black women,” African American Policy Forum, Center for Intersectionality and Social Policy Studies, Columbia Law School

Dancy, T. E., Edwards, K. T., & Earl Davis, J. (2018). Historically white universities and plantation politics: Anti-blackness and higher education in the black lives matter era. Urban Education, 53(2), 176-195.

Love, B. L. (2017). Difficult knowledge: When a Black feminist educator was too afraid to #SayHerName. English Education, 49(2), 197–208.

McKittrick, K. (2010). Science quarrels sculpture: The politics of reading Sarah Baartman. Mosaic: An Interdisciplinary Critical Journal, 43(2), 113-130. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/44030627

Spillers, H. J. (1987). Mama’s baby, papa’s maybe: An American grammar book. African American Literary Theory, 257-279.

Weheliye, A. G. (2014). Habeas viscus: Racializing assemblages, biopolitics, and black feminist theories of the human.

Williams, P. (1997). Spirit‐murdering the messenger: the discourse of fingerprinting as the law’s response to racism in: A. Wing (Ed.) Critical race feminism: a reader New York New York University Press 229-236

Wing, A.K. (1990). ‘Brief reflections toward a multiplicative theory and praxis of being’ Berkeley Women’s Law Journal, Vol. 6: 181–201.

Wynter, S. (1994). “‘No Humans Involved’: An Open Letter to My Colleagues.” Forum N.H.I.: Knowledge for the 21st Century, in N.H./. Forum: Knowledge for the 21st Century’s inaugural issue “Knowledge on Trial.” 1, no. 1 : 42-73.

Theory I: Flesh and Fragment Overview This project was inspired by and drew from Alexander Weheliye’s Habeas Viscus, Hortense J. Spillers “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe: An American Grammar Book” (1987) and Sylvia Wynter’s "'No Humans Involved': An Open Letter to My Colleagues" (1994) in connection to the Black woman's body through time and space in conjunction with “Fragment of a Queen’s Face,” a figure in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (The Met) in New York.

#Alexander weheliye#beverly bond#Beyonce#black girls rock!#black panther#black women#fragment of a queens face#future#habeas viscus#hiergyphs#hortense spillers#James Baldwin#jasper#jay-z#kashema#killmonger#metropolitan museum of art#my favorite girl#no humans involved#past#present#Sarah baartman#sesame street#truth

0 notes

Quote

We were never meant to survive into adulthood, at least not as sensitive femme/feminine Black boys.

from 808s&Heartbreak by Katherine McKittrick&Alexander G. Weheliye

18 notes

·

View notes

Quote

How do we tell the story outside of the splash of sexual violence (and thus anti-blackness), since summoning the violence encountered by Black folks is so often bullied into doing the psychic, physiological, and affective dirty work for white supremacy? Whenever there is some type of crisis around “intimate” violences in particular, Black folks are summoned as ciphers through which that labor is accomplished without it having to affect the actual structures of white supremacy. Instead of confronting the many violences, sexual and otherwise, white men and women committed against Black female persons (“high crimes against the flesh,” Spillers calls it), the broken and torn black person, lynched, stands in as representative-knowable-enclosed-locked-down violence.

from 808s&Heartbreak by Katherine McKittrick&Alexander G. Weheliye

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Book Review -- Ordinary Notes

I read a best-selling new novel by a young white woman. I force myself to finish it because perhaps it is necessary to witness, again, the effortless and unremarked-upon cannibalization of Black life.

The ordinary notes of our use and erasure.

Ordinary Notes, Sharpe's third book, is a hard thing to review. It's much more loosely organized than Monstrous Intimacies (built around closeness and affect) and In the Wake (built around the wake, remembering, long breakings). It's a collection of 1-2 page notes which aren't explicitly related to one another, notes on whiteboys, reading, self-strangulation, the academy, pictures. These are notes, small short things without the time to explain themselves, and too ordinary to deserve that explanation anyways. So the notes are presented quasi-ethnographically with redactions that make the flesh of them glimmer and slowly connect over the course of the book.

It's a mode of presentation that reminds me of two different styles. First, there's the work of Donna Haraway and Alexander Ghedi Weheliye, both authors that seem to cram hundreds of good theses in just a few pages, all things that could have been unrolled and explained, but they aren't, so their writing starts to fold in on itself as they continue to pile more new things onto the reader. The notes feel like this; some are self-contained, some are not, but the reader's initially drowned in them. Second, there's the introduction of a book called Discreet indiscretions: the social organization of gossip, by Jörg Bergmann. Here, he notes one key problem in the study of gossip -- gossip, by definition, is not considered a thing worthy of study, not considered a thing with hidden meaning, or any meaning at all. Gossip is foundationally useless, and so studying it is a paradox. The ordinary-ness of the concept means that study mutates gossip into something very different.

So this is the frame I'm using here. Ordinary Notes are ordinary and notes; they resist conventional epistemics and appear in such grand quantities that they bury the reader. The 248 notes in the book connect only loosely, and trying to wrap them all into one grand narrative would lobotomize them. But that's no excuse for leaving them untouched; that would be worse, leaving the notes isolated, alone, rendered narratives. Soft connections can and should be made.

The book operates along several key lines. First, there is a consistent theme of the insidiousness of spectacle. In discussing 'the ordinary notes of our use and erasure,' Sharpe details 'the everyday sonic and haptic vocabularies of living life under these brutal regimes.' Antiblackness is intimate, full of emotion, and stunningly non-spectacular. It is a gossip-thing, and its spectacular forms cleave paradoxically from itself. Ordinary antiblack notes operate casually, phenomenologically; they are not inevitable or unstoppable, but they are everywhere, and they positively structure everyday life, building intimacies on Black social death. But spectacle is not just something to be ignored to get at the 'real world.' It is a relation of power, 'the right to capture, to capture what is deemed abjection, and the right to publish it.' It is a relation of seeing that renders the seen thing seen and a thing, a living spectacle that has, miraculously, managed to move and talk and shit.

There's also tenderness. Sharpe's far from naïve about the power of care -- her first book, Monstrous Intimacies, explored all the horrific forms affect and care can take in the process and aftermath of slavery. But she doesn't reject it, and she doesn't reject beauty either. "With beauty, something is always at stake;" this isn't a disavowal, but a vow, a study of the ways monstrous intimacies have shifted, twisted, into something new. The way her grandmother sits elegant for the camera, sitting for her stepfather, 'in his loving look.' Where did she learn that? How can she sit, now, for the camera, the gaze shifting into something so different? She wasn't supposed to be married, then -- what's with the ring on her finger? Sharpe's interested in beauty, care, things that seem like a performance with notes formed in antiblackness, but which have acquired an intense life of their own. Her grandmother sits for the camera, and nothing else, loving eyes, composing, cleaving her history into something different by sitting, annotating herself.

This is one view of Ordinary Notes, using Sharpe's methods of annotation and redaction as proposed In The Wake. The ordinary notes are themselves a form of redaction; the bonds are cut, pictures are made to stand alone, despectacularized, in ways which make them more themselves in certain ways. And Sharpe places other pictures too, masterworks of annotation by other people, using them in ways which cut along the lines they're most resilient to, letting them stand mostly whole while the chaff falls away. The book's doing a lot of things all at once -- it has the density for it -- but this seems like one aspect of it, that Sharpe is looking for ways to cut and cloak spectacle differently.

1 note

·

View note