#Britain's involvement in the slave trade

Text

youtube

This is a very interesting video.

We British are not taught this piece of history unless we research it ourselves and I don't know why.

Why teach black young people that they're all descended from slaves who were brought here (which isn't even true — many came here looking for a better life as free men and women)?

Why teach white kids that we're all descended from slave traders? That isn't true, either.

There was a very brief moment in British history when we were part of the slave trade. It happened because Queen Elizabeth I wanted her little group of friends to do as they pleased, basically. She had the power and the privilege to override any law she liked and she used it to undo centuries of freedom and national pride for the benefit of herself and a group of friends.

British people are still expected to feel the shame one royal brought on us all as a nation today.

#abolition of slavery#slave trade#Britain's involvement in the slave trade#royal navy#learn history#Youtube

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

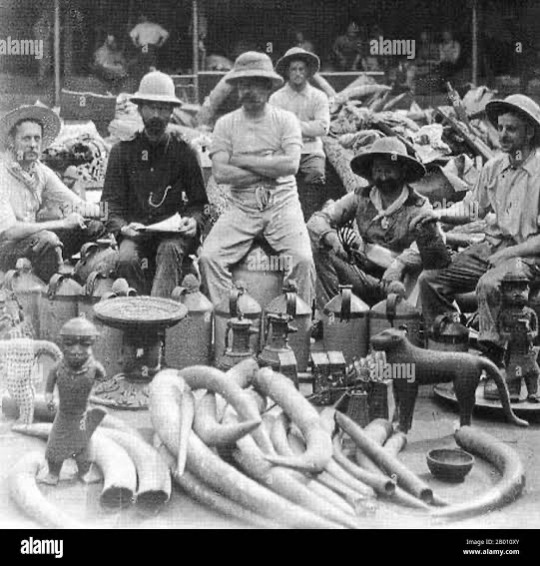

AN ARTICLE ON THE BRITISH LOOTING FROM AFRICA

AND SUFFERING OF AFRICANS

The British should return every loot of all kinds back to Africa

IF THEY CONDEMN SLAVE TRADE THEY SHOULD START BY RETURNING THE LOOTS COLLECTED FROM AFRICA ALL IN THE NAME OF TRADE AND RELIGION ,IF OUR CULTURE WAS BAD WHY DID THEY TAKE AWAY OUR HERITAGE AND STORE THEM IN A MUSEUM ?

The looting of Africa during the colonial era occurred through a combination of methods and strategies employed by European colonial powers, including Britain. Here are some of the ways in which Africa was looted during this period:

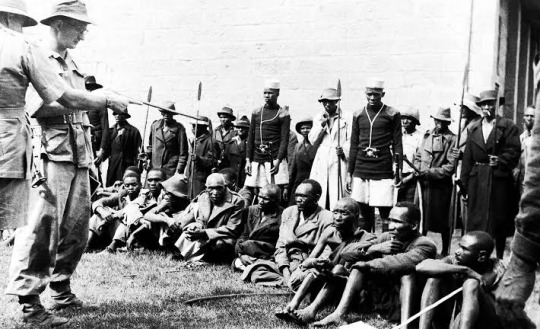

Military Conquest: European colonial powers, including the British, often used military force to conquer and control African territories. This involved armed conflicts, wars of conquest, and the suppression of local resistance movements. Through these military campaigns, colonial powers gained control over land and resources.

Resource Extraction: One of the primary motivations for colonialism in Africa was the exploitation of its abundant natural resources. European colonial powers, including Britain, extracted valuable resources such as minerals, rubber, timber, and agricultural products from African colonies. These resources were often taken for the economic benefit of the colonial powers.

Forced Labor: Colonial powers imposed forced labor systems on Africans to work in mines, plantations, and other labor-intensive industries. These labor practices were exploitative and often involved harsh working conditions and little compensation.

Taxation and Economic Exploitation: Africans were subjected to unfair taxation systems that drained wealth from their communities. Colonial administrations imposed taxes on land, crops, and other economic activities, forcing Africans to generate revenue for the colonial authorities.

Land Dispossession: Africans frequently lost access to their ancestral lands as colonial governments allocated land to European settlers and corporations. This land dispossession disrupted traditional agricultural practices and led to social and economic dislocation.

Confiscation of Cultural Artifacts: Colonial powers often confiscated cultural artifacts, sculptures, art, and religious items from Africa. These items were frequently transported to Europe and ended up in museums, private collections, or auction houses.

Unequal Trade Agreements: Colonial powers imposed trade agreements that favored their own economies. Africans often received minimal compensation for their raw materials and agricultural products, while European countries reaped significant profits from these trade relationships.

Suppression of Indigenous Cultures: The suppression of indigenous African cultures and languages was another aspect of colonialism. European powers sought to impose their own cultural norms and values, often devaluing or erasing African traditions.

Missionaries played a complex role in the context of colonialism and the looting of Africa. While their primary mission was to spread Christianity and convert indigenous populations to Christianity, their activities and interactions with colonial authorities had various effects on the looting of Africa:

1. Cultural Influence: Missionaries often sought to replace indigenous African religions with Christianity. In doing so, they promoted European cultural norms, values, and practices, which contributed to cultural change and, in some cases, the erosion of traditional African cultures.

2. Collaboration with Colonial Powers: In some instances, missionaries worked closely with colonial authorities. They provided moral and religious justification for colonialism and sometimes acted as intermediaries between the colonial administration and local communities. This collaboration could indirectly support the colonial exploitation of resources.

3. Access to Resources: Missionary activities occasionally granted them access to valuable resources and artifacts. They may have collected religious objects, manuscripts, and other items from indigenous communities, which were sometimes sent back to Europe as part of ethnographic or religious collections.

4. Education and Healthcare: Missionaries established schools, hospitals, and other institutions in African communities. While these services were aimed at spreading Christianity, they also provided education and healthcare to local populations, which could have positive impacts on individuals and communities.

5. Advocacy for Indigenous Rights: Some missionaries, particularly in later years, became advocates for the rights of indigenous populations. They witnessed the injustices of colonialism and spoke out against the mistreatment of Africans, including forced labor and land dispossession.

6. Conversion and Social Change: The conversion of Africans to Christianity brought about significant social changes in some communities. It could lead to shifts in social hierarchies, family structures, and gender roles, sometimes contributing to social upheaval.

1. Cultural Bias: The British, like many Europeans of their time, often viewed their own culture, including Christianity, as superior to the indigenous cultures and religions they encountered in Africa. This cultural bias led to the condemnation of indigenous African religions and gods as "pagan" or "heathen."

2. Religious Conversion: Part of the colonial mission was to spread Christianity among the indigenous populations. Missionaries were sent to Africa with the aim of converting people to Christianity, which often involved suppressing or condemning traditional African religions and deities seen as incompatible with Christianity.

3. Economic Interests: The British Empire, like other colonial powers, was driven by economic interests. They often saw the resources and wealth of African societies as valuable commodities to be exploited. This economic agenda could involve looting or confiscating sacred artifacts, including religious objects, for financial gain.

4. Ethnographic Research: Some British colonial officials and scholars engaged in ethnographic research to study African cultures, including their religious practices. While this research aimed to document indigenous cultures, it could sometimes involve the collection of religious artifacts and objects, which were then sent to museums or private collections in Europe.

5. Cultural Imperialism: Colonialism was not just about economic and political domination; it also involved cultural imperialism. This included an attempt to impose European cultural norms, values, and religious beliefs on African societies, often at the expense of indigenous traditions.

The issue of repatriating cultural artifacts looted from Africa during the colonial era has gained significant attention in recent years. Countries and communities in Africa have long called for the return of these treasures, which hold deep cultural and historical significance. Among the former colonial powers, Britain stands at the forefront of this debate. This article explores the ongoing discussion surrounding Britain's role in returning looted artifacts to Africa.

A Legacy of Colonialism:

Britain's colonial history left a profound impact on many African nations, including the removal of countless cultural treasures. During the height of the British Empire, valuable artifacts, sculptures, manuscripts, and sacred items were taken from their places of origin. These items found their way into the collections of museums, private collectors, and institutions in Britain.

The Case for Repatriation:

Advocates for repatriation argue that these artifacts rightfully belong to the countries and communities from which they were taken. They emphasize the importance of returning stolen cultural heritage as a step towards justice and reconciliation. Many African nations view these artifacts as integral to their cultural identity and heritage.

International Momentum:

In recent years, there has been a growing international momentum to address this issue. Museums and institutions worldwide are engaging in discussions about repatriation. Some institutions have initiated efforts to return specific items to their countries of origin, acknowledging their historical and moral responsibility.

Britain's Response:

Britain, home to several renowned museums housing African artifacts, has faced increasing pressure to address this issue. The British Museum, for instance, has faced calls to repatriate numerous artifacts, including the Benin Bronzes and the Elgin Marbles, which have origins in Africa and Greece, respectively.

In response to these demands, some British institutions have started to collaborate with African countries to explore the possibility of returning certain artifacts. These discussions aim to find mutually agreeable solutions that respect both the historical context and the cultural significance of these items.

Challenges and Complexities:

Repatriation is a complex process involving legal, ethical, and logistical challenges. Determining rightful ownership and ensuring proper care and preservation upon return are critical considerations. Additionally, questions arise about how to address the legacy of colonialism and rectify historical injustices.

The Way Forward:

The debate over repatriation is ongoing and highlights the need for respectful dialogue and cooperation between nations. While the return of looted artifacts is an essential step, it should also be part of broader efforts to promote cultural understanding, collaboration, and acknowledgment of historical wrongs.

The issue of Britain returning looted artifacts to Africa is part of a global conversation about justice, cultural heritage, and historical responsibility. While there are complexities to navigate, the growing recognition of the importance of repatriation signifies a potential path forward towards reconciliation and healing between nations and their shared history. The ongoing discussions reflect a commitment to addressing past injustices and fostering a more inclusive and culturally rich future.

They condemn slave trades yet they’re still with our treasures and cultural artifacts and heritage

#life#animals#culture#aesthetic#black history#blm blacklivesmatter#anime and manga#architecture#black community#history#blacklivesmatter#black heritage#heritage

213 notes

·

View notes

Text

While enslaved people were mostly overseas, in colonies, out of sight, slavery funded British wealth and institutions from the Bank of England to the Royal Mail. The extent to which modern Britain was shaped by the profits of the transatlantic slave economy was made even clearer with the launch in 2013 of the Legacies of British Slave-ownership project at University College London. It digitised the records of tens of thousands of people who claimed compensation from the government when colonial slavery was abolished in 1833, making it far easier to see how the wealth created by slavery spread throughout Britain after abolition. “Slave-ownership,” the researchers concluded, “permeated the British elites of the early 19th century and helped form the elites of the 20th century.” (Among others, it showed that David Cameron’s ancestors, and the founders of the Greene King pub chain, had enslaved people.)

But as Bell-Romero would write in his report on Caius, “the legacies of enslavement encompassed far more than the ownership of plantations and investments in the slave trade”. Scholars undertaking this kind of archival research typically look at the myriad ways in which individuals linked to an institution might have profited from slavery – ranging from direct involvement in the trade of enslaved people or the goods they produced, to one-step-removed financial interests such as holding shares in slave-trading entities such as the South Sea or East India Companies.

Bronwen Everill, an expert in the history of slavery and a fellow at Caius, points out “how widespread and mundane all of this was”. Mapping these connections, she says, simply “makes it much harder to hold the belief that Britain suddenly rose to power through its innate qualities; actually, this great wealth is linked to a very specific moment of wealth creation through the dramatic exploitation of African labour.”

This academic interest in forensically quantifying British institutions’ involvement in slavery has been steadily growing for several decades. But in recent years, this has been accompanied by calls for Britain to re-evaluate its imperial history, starting with the Rhodes Must Fall campaign in 2015. The Black Lives Matter protests of 2020 turbo-charged the debate, and in response, more institutions in the UK commissioned research on their historic links to slavery – including the Bank of England, Lloyd’s, the National Trust, the Joseph Rowntree Foundation and the Guardian.

But as public interest in exploring and quantifying Britain’s historic links to slavery exploded in 2020, so too did a conservative backlash against “wokery”. Critics argue that the whole enterprise of examining historic links to slavery is an exercise in denigrating Britain and seeking out evidence for a foregone conclusion. Debate quickly ceases to be about the research itself – and becomes a proxy for questions of national pride. “What seems to make people really angry is the suggestion of change [in response to this sort of research], or the removal of specific things – statues, names – which is taken as a suggestion that people today should be guilty,” said Natalie Zacek, an academic at the University of Manchester who is writing a book on English universities and slavery. “I’ve never quite gotten to the bottom of that – no one is saying you, today, are a terrible person because you’re white. We’re simply saying there is another story here.”

321 notes

·

View notes

Text

The rise of the European empires [...] required new forms of social organization, not least the exploitation of millions of people whose labor powered the growth of European expansion [...]. These workers suffered various forms of coercion ranging from outright slavery through to indentured or convict labor, as well as military conscription, land theft, and poverty. [...] [W]ide-ranging case studies [examining the period from 1600 to 1850] [...] show the variety of working conditions and environments found in the early modern period and the many ways workers found to subvert and escape from them. [...] A web of regulation and laws were constructed to control these workers [...]. This system of control was continually contested by the workers themselves [...]

---

Timothy Coates [...] focuses on three locations in the Portuguese empire and the workers who fled from them. The first was the sugar plantations of São Tomé in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. The slaves who ran away to form free communities in the interior of the island were an important reason why sugar production eventually shifted to Brazil. Secondly, Coates describes working conditions in the trading posts around the Indian Ocean and the communities of runaways which formed in the Bay of Bengal. The final section focuses on convicts and sinners in Portugal itself, where many managed to escape from forced labor in salt mines.

Johan Heinsen examines convict labor in the Danish colony of Saint Thomas in the Virgin Islands. Denmark awarded the Danish West Indies and Guinea Company the right to transport prisoners to the colony in 1672. The chapter illustrates the social dynamics of the short-lived colony by recounting the story of two convicts who hatched the escape plan, recruited others to the group, including two soldiers, and planned to steal a boat and escape from the island. The plan was discovered and the two convicts sentenced to death. One was forced to execute the other in order to save his own life. The two soldiers involved were also punished but managed to talk their way out of the fate of the convicts. Detailed court records are used to show both the collective nature of the plot and the methods the authorities used to divide and defeat the detainees.

---

James F. Dator reveals how workers in seventeenth-century St. Kitts Island took advantage of conflict between France and Britain to advance their own interests and plan collective escapes. The two rival powers had divided the island between them, but workers, indigenous people, and slaves cooperated across the borders, developing their own knowledge of geography, boundaries, and imperial rivalries [...].

Nicole Ulrich writes about the distinct traditions of mass desertions that evolved in the Dutch East India Company colony in South Africa. Court records reveal that soldiers, sailors, slaves, convicts, and servants all took part in individual and collective desertion attempts. [...] Mattias von Rossum also writes about the Dutch East India Company [...]. He [...] provides an overview of labor practices of the company [...] and the methods the company used to control and punish workers [...].

---

In the early nineteenth century, a total of 73,000 British convicts were sentenced to be transported to Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania). There, the majority were rented out as laborers to private employers, and all were subjected to surveillance and detailed record keeping. These records allow Hamish Maxwell-Stewart and Michael Quinlan to provide a detailed statistical analysis of desertion rates in different parts of the colonial economy [...].

When Britain abolished the international slave trade, new forms of indentured labor were created in order to provide British capitalism with the labor it required. Anita Rupprecht investigates the very specific culture of resistance that developed on the island of Tortola in the British Virgin Islands between 1808 and 1828. More than 1,300 Africans were rescued from slavery and sent to Tortola, where officials had to decide how to deal with them. Many were put to work in various forms of indentured labor on the island, and this led to resistance and rebellion. Rupprecht uncovers details about these protests from the documents of a royal commission that investigated [...].

---

All text above by: Mark Dunick. "Review of Rediker, Marcus; Chakraborty, Titas; Rossum, Matthias van, eds. A Global History of Runaways: Workers, Mobility, and Capitalism 1600-1850". H-Socialisms, H-Net Reviews. April 2024. Published at: h-net.org/reviews/showrev.php?id=58852 [Bold emphasis and some paragraph breaks/contractions added by me. Presented here for commentary, teaching, criticism purposes.]

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Persuasion: The Paperwork Problem

I am obsessed with the fact that Captain Wentworth does Mrs. Smith’s paperwork for her, and not just because having a male romantic protagonist do paperwork as part of demonstrating his ultimate worthiness (and swoon-worthiness) proves that no one is doing it like Jane Austen. No, I am obsessed with it because Britain’s transatlantic economy is in flux in the early nineteenth century. And because this Persuasion reread has convinced me that Austen does everything in this novel on purpose to make me suffer. Here is my theory: what Wentworth is doing is divesting from slavery. What? you may exclaim, gentle readers, and I am here to lay evidence for my tenuous little theory before you.

Point 1: Wentworth’s behavior here is explicitly contrasted with that of Mrs. Smith’s wastrel husband. These are alternate models of masculinity. And Mrs. Smith’s narrative for Anne very clearly links not only the late Mr. Smith’s moral corruption with his mismanagement of this property, but also Mr. Elliot’s lack of moral backbone with his failure to manage it for her. And this is property “in the West Indies,” which at the turn of the nineteenth century means basically one thing: sugar. And sugar, in turn, means slavery. But things are changing! From 1807, the transatlantic slave trade is illegal in Britain and its possessions. I’m not going to dwell here on the obvious ongoing horrors of slavery, but one of the relevant consequences here is that the plantation economy of the British West Indies basically tanks. ...Sort of, at least. There’s scholarly debate on the question of how much this happens, why it happens, and when it happens. Which brings me to:

Point 2: whichever combination of factors we accept for the decline of the plantation system -- Napoleonic Wars, beet farming in South America, British economic commitment (eventually, sort of) to the abolition of slavery -- it makes sense for Wentworth’s management of Mrs. Smith’s property to be part of this. Admittedly, Persuasion is a novel where, in contrast to Mansfield Park, the vast and sinister machinery of the British Empire is allowed to be mostly invisible, especially to the modern reader. But we are told that Mrs. Smith suffers partly because the property is “under a sort of sequestration,” in theory (or initially) to pay Mr. Smith’s debts, but now controlled by the courts because of some combination of greed, incompetence, indifference, and inertia. And Wentworth knows, he knows to his core, he knows from experience, exactly how cheaply the empire values the lives of its subjects. We, in turn, know that he knows this because of light dinner table conversation. Jane Austen, everyone.

Point 3: Jane Austen makes choices about what to emphasize in Wentworth’s naval career. There are a lot of glamorous actions that he could have been linked to. But there’s no name-dropping of the Nile or Trafalgar. No, most of what he’s been doing is chasing privateers and French ships, maintaining a balance of power favorable to the British interest, and making a lot of money while doing so. And routinely risking his life in ways that make Anne very distressed even in retrospect. The exception, the only named military endeavor to which Frederick Wentworth is linked, and which earned him a promotion, is “the action off San Domingo.” This stunning British victory was, of course, aimed at breaking French power in the Caribbean. And this is what we get told about. Among other things, this means that it’s entirely possible that Wentworth also saw action in the Haitian Revolution (again, the British involvement in this was cynical. But still.) Also relevant here, I would argue, is that we are told that the Crofts have never been in the West Indies (and Mrs. Musgrove, a perfectly nice woman but also one perfectly capable of blinding herself to unpleasantness, cannot accuse herself of having ever called Caribbean islands anything in the whole course of her life.) I am convinced that all of this, in this minor miracle of a novel, matters.

Point 4: economic logic. In 1815, there is no way for Mrs. Smith’s economic fortunes to recover and her property to start creating (rather than losing) income if she is trying to manage a sugar plantation. It’s just not going to happen. In a way, this is coming back to Point 1, but without the character-driven elements. If we take this seriously as plausible, I think we have to draw the conclusion that Wentworth has taken in hand arrangements to alter how that property is being used.

Point 5: Anne. The first thing we learn about Anne is that she is not only willing but eager to force irresponsible members of the landed gentry -- even her own family, especially her own family -- to give up luxuries which they think of as necessities. This is the context in which we are introduced to her. This is the first way we learn who Anne Elliot is. The first thing we are allowed to see Anne wanting is “indifference for everything except justice and equity.” In other words, this is a woman who refuses sugar in her tea. And however different she and Wentworth are in temperament, we are also told (from Anne’s perspective!) that there are “no tastes so similar, no feelings so in unison.” So I don’t think it’s too much of a stretch to take her morality as an indicator of his probable actions.

In short: I think Persuasion’s coda can be read as anti-slavery. Because of paperwork.

#persuasion reread#persuasion#*chews glass harder*#no i will not be normal about this thanks for asking#jane austen#will not let us REST#i suffer in niche ways#maybe this is all just FAR too tenuous for a proper lit crit take#but i YEARN to see academic writing on empire and/in persuasion#(yes i looked in the databases while losing sleep over this)#eta: please debate this with me#i live alone and have no one to yell at about this

424 notes

·

View notes

Note

TELL US ABOUT QUAKERISM

This is an absolutely hilarious thing to find in my inbox in all caps thank you so much 😂 I was going to say something like, "I'll try to keep this brief" but realistically I know I'm gonna waffle so BRACE FOR WAFFLING.

Quakers - also known as the Religious Society of Friends - are a denomination of Christianity that was founded in the mid-1600s in the north of England. It was part of the Dissenters movement, which is a term for a collection of Protestant denominations that grew up around that time out of criticism, dissatisfaction and... dissent... with the Church of England.

The branch of Quakerism that I belong to is actually in the global minority for Quakers. Most Quakers worldwide belong to evangelical branches and I'm not at all clear on how their theology differs from mainstream evangelical Christianity.

Those meetings (the Quaker term for churches/congregations) are what's called "programmed", which means their worship takes the form of a service easily recognisible by most Christians with hymns, a minister, prepared readings from the Bible, etc. I really can't speak much to that side of things as I know almost nothing abou it!

In contrast, my branch of Quakerism - by far the most common in Britain and Ireland, and I think I'm right in saying the most common in Europe and North Amerca though I'm not 100% sure - is "unprogrammed". There's no service, instead we sit together for an hour in silence. That silence might be broken by any person taking part who feels moved to stand up and speak - this is called "ministry" and for theist Quakers, it's understood as being a response to the promptings of what some people call the Light, some people call God, some people call the Holy Spirit.

This unusual worship style is an expression of the foundational Quaker belief that nobody has more of a connection to the holy than anyone else. A minister isn't better able to speak to God than a layperson, and we place a lot of emphasis on speaking to your own experiences of the divine and respecting others' experiences. A phrase often used to describe this idea is "There is that of God in everyone."

As well as unprogrammed worship, this side of Quakerism has historically been very socially and theologically liberal/radical. Early Quakers were very involved in prison reform and abolition of the slave trade, and that social consciousness has carried through the centuried to see Quakers involved in all sorts of social justice causes from pacifism and anti-war work to climate justice and queer liberation.

Quakerism is a non-credal faith, which means there's no list of beliefs you have to subscribe to in order to be a Quaker. It's also non-sacramental, so we don't have things like christenings, baptisms, communion, etc.

There is a difference between being a "member" of a meeting and being an "attender", but the differences are largely administrative and effect what kinds of roles you can take in the meeting rather than whether you're considered a "full" Quaker or not. Those roles are things like treasurer or clerk - logistical roles related to the running of the meeting rather than spiritual leadership - and they change hands regularly.

That said, there are some basic concepts aside from "that of God in everyone" that guide most Quaker ideas. These are called "testimonies", and there's no total consensus on what they are - I have a feeling different Quakers in the world have a different list - but the ones I'm familiar with are Peace, Equality, Truth and Simplicity. Some people add Sustainability, personally I think that's accounted for under the first four, namely Equality and Simplicity.

The Peace testimony might be the most famous Quaker principle. Quakers are a pacifist group (though not all Quakers agree on what that pacifism should look like...) and have oppose war and violence in all sorts of ways, from refusing to join the military and being conscientious objectors to not buying their children toy guns and so on.

Equality is pretty simple to get your head round! If all people have something holy in them, they all deserve to be treated fairly. Quakers resist personal and structural inequality, and we organise ourselves in a way that reflect that as well as working to make the world around us more equal and fair. This is both on a broad scale and on a granular one - some Quakers still use "thee/thou" because early Quakers did as a way of rejecting social hierarchies. Personally I prefer not to use salutations which stem from the same thing.

Simplicity is often simplified to a kind of general anti-consumerism, which is why I think Sustainability falls under this (I think it goes under Equality too because of the social impact of climate change etc). With this testimony, you're encouraged to find joy in simple pleasures and to appreciate the world around you. You don't need more stuff to be happy, and we owe it to ourselves and others to think carefully about how much we consume, what we consume, and why.

Finally, Truth or Integrity is about living up to your principles. It's about being honest with yourself about whether you're living your faith and putting your values into action, and about speaking the truth in all cases. Early Quakers refused to take legal vows or oaths, because they committed to always speaking the truth so it made no sense theologically for them to say "OK but for real now I'm actually being honest". I'd still "affirm" in court rather than take a vow, for the same reason.

All in all, I'm really proud of being a Quaker and personally I can see a lot of Quakerism in Monstrous Agonies (and all my writing!) which isn't very suprising because Quakerism informs a huge part of my life and worldview. It's not some kind of perfect, historically spotless religion - as well as being abolitionists, some Quakers were also slave-owners, for example, or were involved in the residential schools for Native Americans, and individual Quakers are as flawed as any other group. But I think we make a good effort at repairing those wrongs, being honest about our failings and making reparations.

Also, the porridge oats are nothing to do with us.

#im not sorry and im not going to pretend to be#i am simply not a person capable of being asked to tell someone about something and not Telling Them#monstrous askbox#always open to questions about quakers!!#quakerism#i am and remain the best looking and most fuckable quaker in podcasting

147 notes

·

View notes

Text

It was bound to happen sooner or later: a guest on the BBC’s Antiques Roadshow presented an artefact, which derived from the slave trade – an ivory bangle.

One of the programme’s experts, Ronnie Archer-Morgan, himself a descendant of slaves, said that it was a striking historical artefact but not one that he was willing to value.

‘I do not want to put a price on something that signifies such an awful business,’ he said.

It’s easy to understand how he feels. The idea of people profiting from the artefacts left over from slavery is distasteful.

Yet, as Archer-Morgan said, it is not that the bangle has no value: it has great educational value.

It should be bought by a museum and displayed in order to demonstrate the complex nature of slavery and as a corrective to the narrative that slavery was purely a crime committed by Europeans against Africans.

The bangle was, it seems, once in the possession of a Nigerian slaver who was trading in other Africans.

It’s a reminder that slavery was rife in Africa long before colonial government.

It could also remind us that, though slavery was a global institution, the country that led the world in the rebellion against this barbarism – and played a bigger role than perhaps anyone else in its eradication – was the United Kingdom.

Britain did not invent slavery.

Slaves were kept in Egypt since at least the Old Kingdom period and in China from at least the 7th century AD, followed by Japan and Korea.

It was part of the Islamic world from its beginnings in the 7th century.

Native tribes in North America practised slavery, as did the Aztecs and Incas farther south.

African traders supplied slaves to the Roman empire and to the Arab world. Scottish clan chiefs sold their men to traders.

Barbary pirates from north Africa practised the trade too, seizing around a million white Europeans – including some from Cornish villages – between the 16th and 18th centuries.

It was in fear of such pirates that the song ‘Rule Britannia’ was written: hence the line that ‘Britons never ever ever shall be slaves.’

Even slaves who escaped their masters in the Caribbean went on to take their own slaves.

The most concerted campaign against all this was started by Christian groups in London in the 1770s who eventually recruited William Wilberforce to their campaign, and parliament went on to outlaw the slave trade in 1807.

British sea power was then deployed to stamp it out.

The largely successful British effort to eradicate the transatlantic slave trade did not grow out of any kind of self-interest.

It was driven by moral imperative and at considerable cost to Britain and the Empire.

At its peak, Britain’s battle against the slave trade involved 36 naval ships and cost some 2,000 British lives.

In 1845, the Aberdeen Act expanded the Navy’s mission to intercept Brazilian ships suspected of carrying slaves.

Much is made about how Britain profited from the slave trade, but we tend not to hear about the extraordinary cost of fighting it.

In a 1999 paper, US historians Chaim Kaufmann and Robert Pape estimated that, taking into account the loss of business and trade, suppression of the slave trade cost Britain 1.8 per cent of GDP between 1808 and 1867.

It was, they said, the most expensive piece of moral action in modern history.

The cost of fighting the slave trade cancelled out much, if not all of Britain’s profits from it over the previous century.

There are those who continue to demand reparations for slavery from the UK government and other western powers, yet they rarely, if ever, acknowledge Britain’s role in all but eradicating the evil of the transatlantic slave trade, a cause on which we spent the equivalent of £1.5 billion a year for half a century.

Britain’s role in hastening slavery’s extinction is a remarkable achievement.

It’s astonishing that we have forgotten it almost entirely in the 21st century.

It would be difficult to find anyone in the world whose ancestral tree does not somewhere extend back to a slave-trader.

Huge numbers of us, too, will have been partly descended from slaves.

Britain should not minimise or deny the extent to which it traded slaves to the colonies in the early days of Empire.

But it is also important to remember the thousands who served and died with the West Africa Squadron while seizing 1,600 slave ships and freeing some 150,000 Africans.

We must examine and remember everything about the history of the slave trade, including the forces – moral and military – that eventually brought it to an end.

It’s profoundly worrying that slavery evolved to be a near-universal phenomenon among human societies and inspiring that it came to be all but eradicated within a single human lifespan.

#Britain#slave trade#Antiques Roadshow#Ronnie Archer-Morgan#ivory bangle#artefacts#Rule Britannia#William Wilberforce#Aberdeen Act#slavery#suppression of slave trade#moral action#transatlantic slave trade#BBC

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kate Middleton the slave liberator by proxy. Are you serious?

Article in the Daily Mail

The British press — and specifically the Mail titles — have outdone themselves again. This morning we learnt that contrary to what the Sussexes may have implied about racism in the British Royal Family, it simply cannot be true. This is because an “ancestor” of Kate Middleton, the Princess of Wales, was the ‘greatest American abolitionist’.

Of course the Daily Mail’s brilliant writer neglects to mention that Harriet Martineau, an Englishwoman who only visited America for a few months in the 1830s, never married nor had children. The Mail itself says she’s Kate’s “great-great-great-great-great-aunt”, so how she came be an “ancestor” and an American is a mystery.

Nevertheless, this woman I’d never heard of was so powerful that it was through her lobbying of Presidents Monroe and Jackson that the slaves were freed. Including, the Mail points out helpfully, “the Duchess of Sussex’s great-great-great-great-grandfather, Stephen Ragland”. So clearly the Duchess of Sussex is beholden to the Princess of Wales for not being a slave today.

The Mail details the ‘connection’ between Kate’s ‘ancestor’ and Meghan Markle

It’s not even funny. It is deeply offensive to me, a descendant of slaves, whose ancestors fought the British like hell for over two centuries for our freedom.

It is offensive to the memory of all the freedom fighters of the Americas, from Toussaint Louverture, to Nanny of the Maroons, to Frederick Douglass, to Harriet Tubman, to John Brown — to everyone in the emancipation movement — to assert that all it took was some lobbying from one white British visitor in America to free the slaves.

The movement to abolish slavery was global, hard fought and hard won. That the writers and editors of the Daily Mail think differently is an indictment on Britain’s entire system of education. History is clearly not taught. Not the history of Britain, slavery, and the slave trade, and certainly not the history of British racism.

Another offensive part of this story is the idea that an abolitionist couldn’t be a racist. Go back and read Uncle Tom’s Cabin, written by Harriet Beecher Stowe, an abolitionist. (See what I wrote about Harriet some years ago, below.)

Many people felt that slaves should be freed in the same way they felt people shouldn’t be cruel to animals. But they didn’t think Black people were their equals. Abraham Lincoln was notoriously racist. So, an abolitionist is not automatically absolved of racism.

Whatever Kate Middleton’s distant relative’s actual feeling about Black people, it is ludicrous to posit that therefore the Royal Family can’t be racist. It’s not just the fact that Kate is only a royal by marriage, it is that you cannot inherit anti-racism by blood.

If one could, as opposed to being anti-racist because of an aunt-in-law lost in the mists of time, how much more likely would it be that Kate’s husband Prince William and her father-in-law King Charles III would have inherited racism from the long line of documented slavery profiteers and racists in the British Royal family?

Prince William’s namesake William IV, when he was Duke of Clarence, actually spoke in the House Lords in favour of maintaining the slave trade, and outlined nicely how the British Royal Family had been involved in it for centuries.

And we don’t have to go that far back to see evidence of how Black and other ethnic minorities are treated by the British Royal Family. They were banned from employment in Buckingham Palace up to the late 1960’s and probably later — since they are exempt from fair labour laws.

In 2021, Prince William and Kate declined to publish diversity figures for their Kensington Palace office, though his grandmother’s Buckingham Palace and his father’s Clarence House did. We suspect because they had no diversity to report.

So have done. No matter how much you want to exalt Kate at the expense of Meghan, please stop the foolishness. We see right through you, and you are offensive and not very bright.

Meghan Markle is probably as astonished as we feel (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

Why I’m not celebrating Harriet Beecher Stowe

The Episcopal Church celebrates Harriet Beecher Stowe on July 1. While appreciating the efforts Stowe and her brother Henry Ward Beecher made in the cause of the abolition of slavery in America, in my opinion, she was not an unmixed blessing to the ‘Negro Race’, as she’d have called us.

Uncle Tom’s Cabin was highly, highly influential. It was the best selling book of the 19th century apart from the Bible. It was the principal vehicle Stowe used to open the eyes of the good people of the US to the evils of slavery.

However, its picture of the childlike African, to be pitied and made an object of gracious condescension, has had lasting effects. The image of the good and humble Uncle Tom, who was too Christian to even dream of fighting back when he was whipped to death by Simon Legree, made white folks believe that is the quintessential good negro.

There was more. The ‘good’ woman on the plantation, who gave her master’s white child her children’s food before she fed her children. All the good Black people who put the white people first, since first is the proper place for white people.

And, the paler the black people were — the closer to white — the closer they were to human. The mulatto slave woman who drowned herself rather than be sold into slavery contrasted with the Black people who were less sensitive. Topsy, the lying child, who didn’t cry when she was whipped, because she didn’t feel it much, was very dark-skinned.

Then there were the last two mulattos, a man who could pass for white, and his very pale wife, who were so bright and articulate, who escaped slavery and went north to Canada. But eventually they realized their proper place was in Africa.

Stowe pitied the plight of the black slaves, and she thought they were inhumanely treated, but she didn’t think they were ‘equal’.

Their proper place was to be grateful for the benevolence of the good white people, but the negroes really didn’t belong in the Americas. She clearly thought they should have been returned to their native habitat — Africa — so white people would be clean from the stain of slavery.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

The British Crusade Against Slavery | Sargon of Akkad

What really bothers me is Frankie Boyle's attempt to make British people feel ashamed of Britain's involvement in the slave trade.

That really gets my goat because Britain's involvement in the slave trade is one of the most proud accomplishments of British history.

And i know what you're thinking: oh my, goodness slavery is bad. And that's correct.

Which is why the British ended it.

For everyone.

[..]

The Portuguese did take a few Africans back to Europe, but they didn't need to set up operations, because they discovered that there were already thriving slave trades in Africa.

And so they bought slaves from African rulers and traders. The vast majority of slaves taken out of Africa were sold by African rulers, traders and military aristocracy who grew wealthy from the business. Most slaves were acquired through wars or by kidnapping.

And before you start thinking that this is excessively barbaric,

this was the standard for almost every civilized society all across the world.

[..]

The point is that slavery was ubiquitous. No matter where on Earth you traveled, you found slaves. In Europe, in China, in the Middle East, in the New World, in India, in Scandinavia, in Africa.

Slavery was as common an institution as animal husbandry.

[..]

The West Africa Squadron was a detachment of the Royal Navy that was given the task of blockading Africa, the continent, to make sure that slave traders were not taking slaves to the Americas.

Needless to say, in 1807 there was only a token force performing this operation, comprising of two ships. This number was increased to five ships until the war of 1812 with the United States, but after 1815 with Britain victorious in Europe and supreme at sea, the Royal Navy turned its attention back to the challenge.

The institution of slavery was formally abolished in the British Empire in 1833 and by the 1850s, around 25 vessels and 2 000 officers and men were on the station, supported by nearly a thousand "kroomen," experienced fishermen recruited as sailors from what is now the coast of modern Liberia.

[..]

All of this was done against the vested financial interests of hundreds of thousands of people. Entire nations were against the idea of abolishing slavery and the slave trade.

The very notion was alien to the human existence until Britain made it happen.

In the 19th century if you saw a ship bearing down on you flying this flag and you were a slave trader, you knew that this flag stood for liberty. This was the flag of a nation that defied human convention for a point of principle, and spent its blood sweat, tears and treasure to enforce it on the world.

This is the flag of the nation that accepted the absolute moral truth that slavery is wrong. No matter what riches can be amassed, no matter what power can be gained, no matter the cost, slavery had to be abolished. That was the British crusade.

When Britain held the reigns of world power, that is what she did with it.

Reaction:

youtube

youtube

#Sargon of Akkad#transatlantic slave trade#West Africa Squadron#Blockade of Africa#history#slavery#history of slavery#British crusade#religion is a mental illness

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

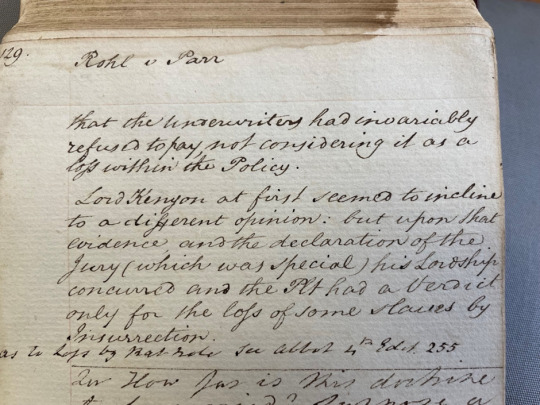

Rohl v Parr: A blog post by Middle Temple Library Intern Natasha Southall.

For the past few months I have been transcribing and cataloguing MS17, ‘Cases at Nisi Prius’, containing nominate reports of cases at Nisi Prius. The manuscript belonged to Sir Vicary Gibbs (1751-1820), and may have been written by him. The cases date from the 1760s to 1810s and vary in nature, from libel charges and indictments of fraud, to actions of trover and bills of exchange. I came across several insurance claims for ships that had been damaged at sea. In most of these cases, the contents of the cargo were not specified. One which caught my attention was a case brought by the slaver named Rohl in 1796, where two significant details of the circumstances of the claim are provided: at one point during the voyage there was a slave insurrection, resulting in the death of eight enslaved Africans, and the ship was “destroyed by destructive worms that infest the River of Africa” (folios 128-129). Both factors were integral in determining the success of the insurance claim in court.

1. Rohl’s voyage from Saint Barthélemy to Cape Coast (original map from www.freeworldmaps.net)

On 1st September 1792, the Zumbee sailed from St Bartholomew (Saint Barthélemy) to the River Gombroon on the coast of Africa [1]. Here, it was reported, a slave insurrection resulted in the loss of eight slaves (seven were killed and one died from falling) out of a total of forty-nine. The report claimed that the ship then struggled to get to Cape Coast because the bottom had been “taken by the worm”, likely to be toredo worms/shipworms, which were a common cause of damage to wooden ships in this period. At Cape Coast, the ship was “condemned as irreparable” and sold.

2. Rohl v Parr, folio 128 with ‘worms’ in the margin

The insurance claim was predicated on the policy of damage due to ‘peril at sea’. However, Lord Kenyon and the special jury agreed that the destruction by shipworms, being “an animated substance moving to destroy [the ship]” rather than “an inanimate substance striking against the ship’s bottom”, did not meet the terms of the ‘peril at sea’ policy. Consequently, the counsel for the plaintiff tried instead to recover the partial loss of the enslaved cargo resulting from the slave insurrection. Luckily for Rohl this was granted, as the loss was calculated as more than 5% at the time when the slaves were killed.

3. Figure 2 Rohl v Parr, folio 129

The transatlantic slave trade witnessed the forced transportation of over twelve million enslaved African men, women and children from Africa across the Atlantic to the Americas. Portugal, Brazil, Britain, France, the Netherlands, Spain, Uruguay, the United States of America and Denmark were all involved. One way we are able to catch a glimpse of the mechanisms underpinning the transatlantic slave trade is through legal records like those in the Gibbs manuscript. The records documenting these horrific and treacherous voyages have been made accessible to the public by the SlaveVoyages initiative [2].

This case of Rohl and Parr does not shed much light on the lives of the individuals who were enslaved and travelled on board the Zumbee; the horrors they must have experienced can only be imagined. The case does make clear, however, the financial risks involved for slavers who embarked on the voyage across the Atlantic to Africa. The underlying threat of insurrection was always on the horizon. Yet it would be the workings of the ‘destructive worms’ that rendered slavers like Rohl defenceless both at sea and in the English courtroom.

Citations

[1] Rohl v Parr, Saturday, Feb. 27th 1796, 1ESP.444., Reports of Cases Argued and Ruled at Nisi Prius.

[2] Slave Voyages, https://www.slavevoyages.org/ (last accessed 26/03/2024).

Natasha Southall,

King’s College London

#Africa#black-history#historicaldocuments#history#law#Law library#Library#MiddleTempleLibrary#slave-trade#slavery#transatlantic slave trade

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

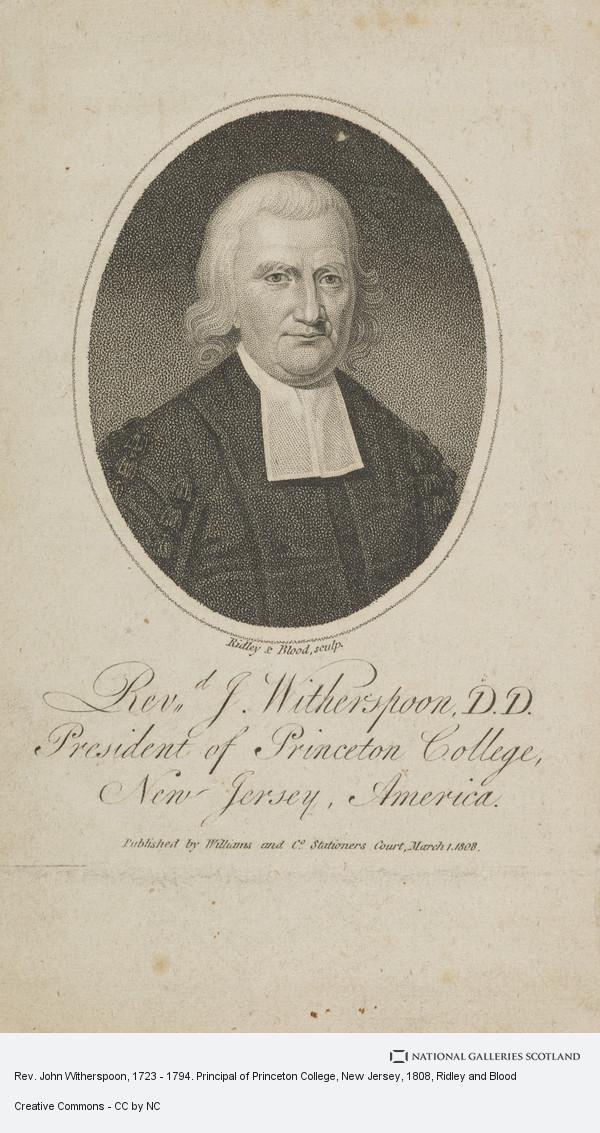

On February 5th 1723 John Witherspoon, clergyman, writer, President of Princeton University, signatory to American Declaration of Independence was born.

Witherspoon was educated at Edinburgh University and was ordained as a minister in 1745. One of his ancestors was John Knox who had been a major force in the Reformation of the church in the middle of the 16th century. Witherspoon’s first charge was as minister of the Auld Kirk in Beith in Ayrshire where he preached for twelve years. He was regarded as a brilliant orator and was “head hunted” by a number of churches in Scotland (and abroad) before moving to Paisley.

While he was at Paisley, Witherspoon met 21-year-old Benjamin Rush who was born in America of Scottish parents, and attended the College of New Jersey (later Princeton University), Rush had then enrolled at the University of Edinburgh’s medical school. Armed with letters from Benjamin Franklin, Rush convinced the 42 year old Witherspoon to leave Scotland and become president of the College of New Jersey in 1768 and a delegate to the 2nd Continental Congress.

Witherspoon was soon supporting the independence fight in America because he believed that his native land had “gone soft on religion”. Of course, the Presbyterian church’s principles of egalitarianism and the natural antipathy of the Scots to the English rulers were factors too.

Witherspoon became what in today’s politics would be regarded as a senator. And in the first draft of the Declaration of Independence in 1776, he demanded the deletion of a phrase that complained that the king of Britain had sent to America “not only soldiers of our common blood, but Scotch and foreign mercenaries.”

However, when some of the representatives from the thirteen American colonies gathered to decide whether to break completely with Britain, some of the delegates realised the difficulty of taking on the might of the British Empire. It was Witherspoon who urged them to sign the Declaration of Independence, saying “There is a tide in the affairs of men, a nick of time. We perceive it now before us. To hesitate is to consent to our own slavery.”

It is worth noting also that of the 56 men who signed the document, 21 had some Scottish ancestry. Witherspoon was the only clergyman to sign this historic document, which has been compared to the Declaration of Arbroath which proclaimed Scottish freedom for the first time.

Witherspoon also became a member of the congress which conducted the war and later helped to draft the peace agreement which brought the war to an end.

After leaving Congress in 1782, Witherspoon was involved in the rebuilding of Princeton College (destroyed during the war). He was its President from 1768 until his death in 1794. More than any other university, Princeton in those days had students from all over the United States, not just from its home state and so Witherspoon’s influence on the country was that much more significant.

As with most white landed gentry of the era Witherspoon was involved in the slave trade. Beginning in 1779, he acquired two enslaved laborers for his country estate. About eight years later, both mysteriously disappeared. New research suggests that at least one may have been freed and settled on his own land. Their demise, sale or escape are other, less cheery, possibilities. Another two enslaved individuals were listed among Witherspoon’s possessions in an inventory dated November 1794, alongside six cows, 10 horses, 12 pigs and 24 sheep. He also recruited the sons of wealthy Southern planters to finance Princeton through donations and tuition.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

"..."The governor of the Royal African Company was James II, otherwise known as the Duke of York," she (Esther Stanford-Xosei) noted, referring to one of the major business enterprises involved directly in enslaving and transporting Africans in the 17th and 18th centuries.

"They also found ways of branding African people with the inscription 'DY,' for Duke of York," Stanford-Xosei said. So many slaves will literally have had the initials of a senior member of the royal family permanently and indelibly etched onto their bodies.

Contemporary members of the British royal family, including Prince William, Harry's brother and the heir to the throne, have expressed sadness about their links to the slave trade, but none has ever apologized for the direct role their ancestors played.

"The appalling atrocity of slaver forever stains our history," William said on a visit to Jamaica last year. "I want to express my profound sorrow."

"The reason why he doesn't go further is that he's aware [of] what it will mean to actually apologize, in terms of the legal obligation to make reparation," suggested Stanford-Xosei. She said William and his family feared it would cost the monarchy, "not only money, but status… He will be exposing the criminality of this institution."

Historians say it's impossible to calculate exactly how much wealth the monarchy generated from trafficking human beings, but when William and Kate visited Jamaica last year, they were met by protests demanding not just an apology, but reparations.

The trip was criticized as a damaging throwback to the days of colonialism, including a meeting with local children who were kept apart from the royal couple by a fence.

Prince Harry is the one royal who has addressed his family's connection to slavery more explicitly.

In Spare, he acknowledges that the monarchy rests upon wealth generated by "exploited workers and thuggery, annexation and enslaved people."

"In terms of Prince Harry going this far, it's really, really important," Stanford-Xosei told CBS News. "We can see the establishment reaction, including… the establishment media, who are seeking to belittle him, demonize him..."

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

In a recent post, I quoted historian Rodney Stark extensively about how religions are not all the same. The different theologies of god in the world religions produce very different kinds of moral systems—some religions have no moral features at all. Consequently, monotheism, and Christianity in particular, was uniquely capable of theologies of God and humanity that made slavery incompatible with faithfulness. It was only when the Bible was corrupted by unchristian motivations that it was perverted to excuse an evil and sinful institution.

From the beginning of the church, Christianity developed theology that condemned slavery. The church in the American South and other Christians throughout history who used the Bible to justify their bigotry and enslavement of human beings were the tragic exceptions to the rule. Their abuse of the Bible stood against the broad and historical understanding of what Christians believed the Bible taught about the equality and intrinsic value of every human being, not matter their race.

Some excerpts from Rodney Stark’s book For the Glory of God: How Monotheism Led to Reformations, Science, Witch-Hunts, and the End of Slavery:

Antislavery doctrines began to appear in Christian theology soon after the decline of Rome and were accompanied by the eventual disappearance of slavery in all but the fringes of Christian Europe. When Europeans subsequently instituted slavery in the New World, they did so over strenuous papal opposition, a fact that was conveniently “lost” from history until recently...

Except for several early Jewish sects, Christian theology was unique in eventually developing an abolitionist perspective...

As early as the seventh century, Saint Bathilde (wife of King Clovis II) became famous for her campaign to stop slave-trading and free all slaves; in 851 Saint Anskar began his efforts to halt the Viking slave trade. That the Church willingly baptized slaves was claimed as proof that they had souls, and soon both kings and bishops—including William the Conqueror (1027-1087) and Saints Wulfstan (1009-1095) and Anselm (1033-1109)—forbade the enslavement of Christians. Since, except for small settlements of Jews, and the Vikings in the north, everyone was at least nominally a Christian, that effectively abolished slavery in medieval Europe...

The first shipload of black slaves [arrived in Portugal in the 15th century], and as black slaves began to appear farther north in Europe, a debate erupted as to the morality and legality of slavery. A consensus quickly developed that slavery was both sinful and illegal.... The principle of “free soil” spread: that slaves who entered a free country were automatically free. That principle was firmly in place in France, Holland, and Belgium by the end of the seventeenth century. Nearly a century later, in 1761, the Portuguese enacted a similar law, and an English judge applied the principle to Britain in 1772.

Although exceptions involving a single slave servant or two, especially when accompanying a foreign traveler, were sometimes overlooked, “beyond a scattering of servants in Spain and Portugal, there were very few true slaves left in Western Europe by the end of the sixteenth century”...

The problem wasn’t that the Church failed to condemn slavery; it was that few heard and most of them did not listen...

In 1787 the Quaker-inspired Pennsylvania Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery was headed by Benjamin Franklin and Benjamin Rush, two of the most respected and influential living Americans. Not to be outdone, many Christian groups and luminaries took up the cause of abolition, and soon abolitionist societies sprang up that were not associated with a specific denomination. But, through it all, the movement (as distinct from those it made sympathetic to the cause) was staffed by devout Christian activists, the majority of them clergy. Indeed, the most prominent clergy of the nineteenth century took leading roles in the abolition movement...

Moreover, as abolition sentiments spread, it was primarily the churches (often local congregations), not secular clubs and organizations, that issued formal statements on behalf of ending slavery. The outspoken abolitionism expressed by Northern congregations and denominational gatherings caused major schisms within leading Protestant denominations, eventuating in their separation into independent Northern and Southern organizations...

[A] virtual Who’s Who of “Enlightenment” figures fully accepted slavery.... It was not philosophers or secular intellectuals who assembled the moral indictment of slavery, but the very people they held in such contempt: men and women having intense Christian faith, who opposed slavery because it was a sin.

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

King Charles you will never be the king of bling

well most of the present collection of crown jewels date from around charles ii's time/the restoration of the monarchy so in a way charles iii will be the king of bling

a good bit of continuity too, given a lot of the present royal jewellery comes from countries that we colonised and enslaved, and charles ii was the dude who Officially started britain's involvement in the transatlantic slave trade (something that horrible histories weirdly neglected to mention like, ever) so... the royal family is as the royal family does!

#sorry i know this was a joke but.#asks#anonymous#the royal family#charles iii#charles ii#history#Admin Dominique

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

every day i think about the article i read about britain’s involvement in the slave trade that called the united states “britain’s biggest alibi” or something to that effect

#its really stuck with me#its part of the larger ”imperial amnesia” of britain that makes me feel insane

1 note

·

View note

Text

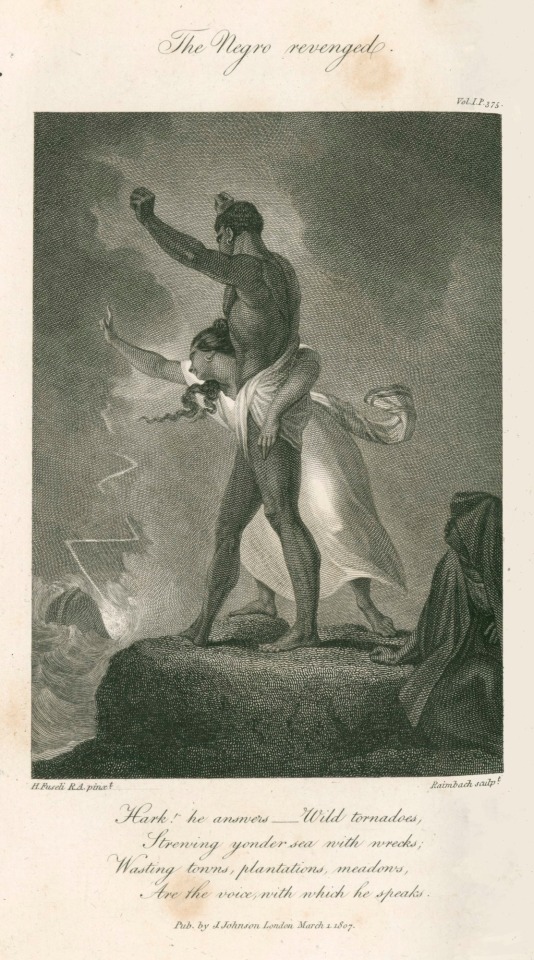

The Negro Revenged, 1 March 1807

After Henry Fuseli RA (1741 - 1825)

Raimbach's engraving reproduces a composition by Henry Fuseli RA which illustrates a poem by William Cowper entitled 'The Negro's Complaint'. The image was published in Poems by William Cowper, 1808. The poem, composed in 1788, is written from the perspective of an enslaved African and became very popular in Britain especially among supporters of abolition. The stanza of the ballad illustrated by Fuseli describes extreme weather conditions and natural disasters around Britain as a form of divine retribution for the country's involvement in the slave trade.

Below the image, lines from the poem are reproduced:

‘Hark – he answers. Wild tornadoes / Strewing yonder sea with wrecks, / Wasting Towns, Plantations, Meadows, / Are the voice in which he speaks.’

Fuseli illustrated this by depicting a Black couple standing on a cliff top, both looking towards the sea where lightning illuminates the hull of a wrecked slave ship. Both of the man's fists are clenched in a gesture of triumph while the woman holds up her right hand with index finger raised as if in warning.

The word ‘Negro’ was used historically to describe Black people. Since the 1960s however, it has fallen from usage and today can be considered highly offensive. The term is repeated here in its original historical context.

2 notes

·

View notes