#Brodavis baileyi

Text

Brodavis

B. americanus by Jack Wood

Etymology: Brodkorb’s Bird

First Described By: Martin et al., 2012

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoromorpha, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostaylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Hesperornithes

Referred Species: B. americanus, B. baileyi, B. mongoliensis, B. varneri

Status: Extinct

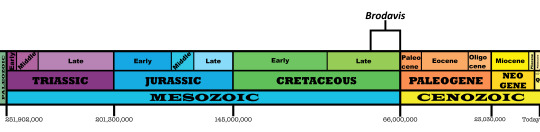

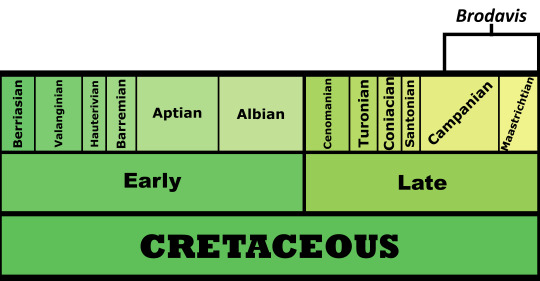

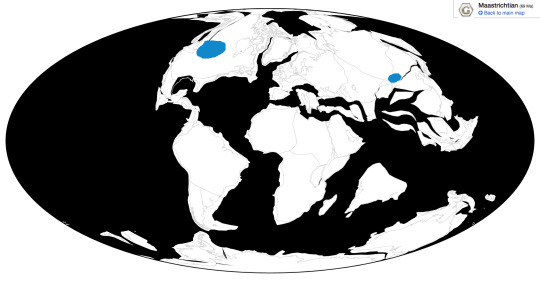

Time and Place: Between 80 and 66 million years ago, from the Campanian to the Maastrichtian ages of the Late Cretaceous

Brodavis is known from a variety of habitats, most within the Western Interior Seaway of North America, with one in Asia: the Frenchman Formation, the Hell Creek Formation, the Pierre Shale Formation, and the Nemegt Formation.

Physical Description: Brodavis was a large bird, but a small dinosaur, reaching up to 90 centimeters in body length (though some species were half that size). It had a cylindrical body and long legs, good for propelling it through the water. It had a lightly built skeleton, though, so it wasn’t well adapted to diving - and may have even still been able to fly, though not particularly well. It had a long, skinny neck, and a small head ending in a long and pointed beak. This beak was full will small, pointy teeth for catching fish. It is unclear whether or not it had webbing between its toes, but this is definitely possible. The colors of Brodavis are poorly known, but it was certainly covered with feathers all over its body.

Diet: Brodavis would have primarily eaten fish and other aquatic life.

Behavior: Being a water-based creature, Brodavis spent most of its time near the water, swimming through along the surface and looking for food. Based on other Hesperornithines, it swam mostly with its feet, propelling them like living animals such as grebes today. Its wings, which were still probably functional, would have not been used in the water. Still, given the presence of flight in Brodavis, it probably would have been able to take off from the water to avoid danger - and back to the water to avoid more danger still, given the large predatory dinosaurs it shared habitats with. It would have then gone to the coasts to rest and rejoin other Brodavis, and would have also had nests there that they had to take care of. How social it was, or other specifics on behavior, are unknown at this time - though it would not be surprising if they lived in large family groups, given how common such behavior is in modern aquatic birds and the fact that it’s a fairly common genus of dinosaur.

B. varneri By Scott Reid

Ecosystem: Being known from a wide variety of habitats, it’s nearly impossible to completely describe everything Brodavis ever lived with in one dinosaur article. That being said, Brodavis tended to live along the coast of major waterways (especially in freshwater areas), where it would spend most of its time underwater but go back to the shores to rest, mate, and take care of their young. Since Brodavis was found both in the Western Interior Seaway and the Seaway of Eastern Asia, it probably would have encountered a wide variety of other dinosaurs. In the Canadian Frenchman Formation, for example, it would have encountered the small herbivore Thescelosaurus, the large hadrosaur Edmontosaurus, the horned dinosaurs Triceratops and Torosaurus, the ostrich-like Ornithomimus, and the large predator Tyrannosaurus. In Hell Creek the companions of Brodavis were many, but included other dinosaurs like Tyrannosaurus, Ornithomimus, Triceratops, Torosaurus, Edmontosaurus, and Thescelosaurus like the Frenchman Formation - but also ankylosaurs like Denversaurus and Ankylosaurus, pachycephalosaurs like Sphaerotholus and Pachycephalosaurus, the small ceratopsian Leptoceratops, another ostrich-like dinosaur Struthiomimus, the chickenparrot Anzu, the raptor Acheroraptor, the opposite bird Avisaurus, and the modern bird Cimolopteryx - and more! In the Pierre Shale, Brodavis was accompanied by other Hesperornithines like Baptornis and Hesperornis. And, finally, in the Nemegt, Brodavis lived with another Hesperornithine Judinornis, the duck Teviornis, the ankylosaur Tarchia, the hadrosaur Saurolophus, the pachycephalosaurs Prenocephale and Homalocephale, the titanosaur Nemegtosaurus, the tyrannosaurs Alioramus and Tarbosaurus, Duck Satan Himself Deinocheirus, the ostrich-mimics Anserimimus and Gallimimus, the alvarezsaur Mononykus, the therizinosaur Therizinosaurus, the chickenparrots Avimimus, Elmisaurus, Nomingia, and Nemegtomaia; the raptor Adasaurus, and the troodontid Zanabazar. Given this wide variety of habitats and neighbors, Brodavis was probably able to live in freshwater habitats, unlike other hesperornithines, and it was decidedly a very adaptable dinosaur.

B. baileyi by Scott Reid

Other: Brodavis represents a unique group of Hesperornithines, though it’s possible the genus is overlumped, which would make the family that currently only has Brodavis in it (Brodavidae) actually informative.

Species Differences: These species differ mainly on where they’re from - B. americanus from the Frenchman Formation, B. baileyi from the Hell Creek Formation, B. mongoliensis from the Nemegt, and B. varneri from the Pierre Shale. As such, B. varneri is the oldest of the four, and may be its own genus. It is also the best known species.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources under the Cut

Aotsuka, K. and Sato, T. (2016). Hesperornithiformes (Aves: Ornithurae) from the Upper Cretaceous Pierre Shale, Southern Manitoba, Canada. Cretaceous Research, (advance online publication).

Bakker, R. T., Sullivan, R. M., Porter, V., Larson, P. and Saulsbury, S. J. (2006). "Dracorex hogwartsia, n. gen., n. sp., a spiked, flat-headed pachycephalosaurid dinosaur from the Upper Cretaceous Hell Creek Formation of South Dakota". in Lucas, S. G. and Sullivan, R. M., eds., Late Cretaceous vertebrates from the Western Interior. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 35, pp. 331–345.

Boyd, Clint A.; Brown, Caleb M.; Scheetz, Rodney D.; Clarke; Julia A. (2009). "Taxonomic revision of the basal neornithischian taxa Thescelosaurus and Bugenasaura". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 29 (3): 758–770.

Campione, N.E. and Evans, D.C. (2011). "Cranial Growth and Variation in Edmontosaurs (Dinosauria: Hadrosauridae): Implications for Latest Cretaceous Megaherbivore Diversity in North America." PLoS ONE, 6(9): e25186.

Carpenter, K. (2003). "Vertebrate Biostratigraphy of the Smoky Hill Chalk (Niobrara Formation) and the Sharon Springs Member (Pierre Shale)." High-Resolution Approaches in Stratigraphic Paleontology, 21: 421-437.

Estes, R.; Berberian, P. (1970). "Paleoecology of a late Cretaceous vertebrate community from Montana". Breviora. 343.

Glass, D.J., editor, 1997. Lexicon of Canadian Stratigraphy, vol. 4, Western Canada. Canadian Society of Petroleum Geologists, Calgary, Alberta, 1423.

Gradzinski, R., J. Kazmierczak, J. Lefeld. 1968. Geographical and geological data form the Polish-Mongolian Palaeontological Expeditions. Palaeontologia Polonica 198: 33 - 82.

Henderson, M.D.; Peterson, J.E. (2006). "An azhdarchid pterosaur cervical vertebra from the Hell Creek Formation (Maastrichtian) of southeastern Montana". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 26 (1): 192–195

Jerzykiewicz, T., D. A. Russell. 1991. Late Mesozoic stratigraphy and vertebrates of the Gobi Basin. Cretaceous Research 12 (4): 345 - 377.

Kielan-Jaworowska, Z., R. Barsbold. 1972. Narrative of the Polish-Mongolian Palaeontological Expeditions 1967-1971. Palaeontologia Polonica 27: 5 - 136.

Lerbekmo, J.F., Sweet, A.R. and St. Louis, R.M. 1987. The relationship between the iridium anomaly and palynofloral events at three Cretaceous-Tertiary boundary localities in western Canada. Geological Society of America Bulletin, 99:25-330.

Longrich, N. (2008). "A new, large ornithomimid from the Cretaceous Dinosaur Park Formation of Alberta, Canada: Implications for the study of dissociated dinosaur remains". Palaeontology. 54 (1): 983–996.

Longrich, N.R., Tokaryk, T. and Field, D.J. (2011). "Mass extinction of birds at the Cretaceous–Paleogene (K–Pg) boundary." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108(37): 15253-15257.

Novacek, M. 1996. Dinosaurs of the Flaming Cliffs. Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group Inc. New York, New York.

Martin, L. D., E. N. Kurochkin, T. T. Tokaryk. 2012. A new evolutionary lineage of diving birds from the Late Cretaceous of North America and Asia. Palaeoworld 21: 59 - 63.

Martyniuk, M. P. 2012. A Field Guide to Mesozoic Birds and other Winged Dinosaurs. Pan Aves; Vernon, New Jersey.

Pearson, D. A.; Schaefer, T.; Johnson, K. R.; Nichols, D. J.; Hunter, J. P. (2002). "Vertebrate Biostratigraphy of the Hell Creek Formation in Southwestern North Dakota and Northwestern South Dakota". In Hartman, John H.; Johnson, Kirk R.; Nichols, Douglas J. (eds.). The Hell Creek Formation and the Cretaceous-Tertiary boundary in the northern Great Plains: An integrated continental record of the end of the Cretaceous. Geological Society of America. pp. 145–167.

Tokaryk, T. 1986. Ceratopsian dinosaurs from the Frenchman Formation (Upper Cretaceous) of Saskatchewan. Canadian Field-Naturalist 100:192–196.

Varricchio, D. J. 2001. Late Cretaceous oviraptorosaur (Theropoda) dinosaurs from Montana. pp. 42–57 in D. H. Tanke and K. Carpenter (eds.), Mesozoic Vertebrate Life. Indiana University Press, Indianapolis, Indiana.

Watabe, M., S. Suzuki, K. Tsogtbaatar, T. Tsubamoto, M. Saneyoshi. 2010. Report of the HMNS-MPC Joint Paleontological Expedition in 2006. Hayashibara Museum of Natural Sciences Reasearch Bulletin 3:11 - 18.

Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; and Osmólska, Halszka (eds.): The Dinosauria, 2nd, Berkeley: University of California Press. 861 pages.

#Brodavis#Euornithine#Hesperornithine#Bird#Dinosaur#Theropod Thursday#Piscivore#North America#Eurasia#Cretaceous#Brodavis americanus#factfile#Brodavis baileyi#Brodavis mongoliensis#Brodavis varneri#Birds#Dinosaurs#prehistoric life#paleontology#prehistory#birblr#palaeoblr#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature

182 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Hesperorniths are most famously represented by the giant flightless Hesperornis, but there are at least 11 other known genera that filled a variety of niches and environments. Brodavis baileyi lived alongside T. rex at Hell Creek, and would’ve been somewhat between a loon and a merganser; a flying freshwater bird. Here, her little... hesperlings? join her for a ride on the water.

#brodavis#hell creek#montana#usa#late cretaceous#maastrichtian#hesperornithes#hesperornis#dinosaurs#birds#bird#paleoart#paleo#paleoblr#palaeoblr

15 notes

·

View notes