#Hesperornithine

Note

Trick or teeth?!

Hesperornis!

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

results from last nights Flocking #paleostream Archelon pulling a Jaws on a Hesperornithin

Edmontosaurus herd moving though a moody swamp, inspired by a Raúl Martín piece

a very floofy Leaellynasaura molting

2 Xenicibis clubing eachother in dual

90 notes

·

View notes

Photo

During the autumn rainy season, Sharn is hit with rain. Enormous, water-laden clouds spin off of the Stormreach Archipelago, delivering life-nourishing precipitation to Khorvaire. It is this rainfall that fuels the temperate rainforests of Zilargo. The area around Sharn also used to be apart of this rainforest, but was chopped down during centuries of occupation. This did not stop the rain, however. If anything, owing to the lack of trees to absorb it all, it made the rain worse. Over the centuries as the city grew and grew, its buildings not bound by gravity as others are. The initial period of building was a direct reaction to this flooding: making it so that the streets and floors would be above the water. However, once the water got into the foundations and started causing even more problems, it was apparent this wasn't going to work out.

During the Early Industrial Period, Galifar ir'Wynarn II, famous for bolstering the city to its current-day height, provided a solution. Using the royal army he dug a series of trenches through the streets called The Depths. These trenches were 30 feet lower than the ground-level of the city and connected directly to the Dagger River and the sea through the ancient sewer systems. This way water could pool up in The Depths until it was steadily drained. This system has been used for hundreds of years, although some would say it requires some updating. Some parts of the city have sunk in to the stone perch of the city over the years and experience flooding on the ground level. Unfortunately, because only the poorest of the poor live on the ground-level, it's unlikely action will be taken swiftly.

One of the side-effects of The Depths is the creation of a unique freshwater environment. In the height of the rainy season the Depths are teaming with life from the Dagger River. Species of water plant have even taken root, using strategies for normal droughts to survive the dry season in their canyon-like homes. While it's too early for new species to evolve, some native to the Dagger River have changed their ways of life to adapt to the man-made river. Like the rubber ducklings. Despite the name they are not related to ducks, instead they are goldfish-sized relatives of the marine hesperornithines. Their name comes from the general urban colloquialism of "if it's a bird in water it's a duck or a penguin" and the rubber toy-like squeak they make when grabbed.

Rubber ducklings normally live around the shallow edges of the Dagger River, eating small fish and invertebrates while avoiding larger predators. The Depths of Sharn provides them a safer opportunity to lay their eggs on land, usually in sewer openings away from large trout and crocodiles, and an abundance of food from otherwise unusual sources. While the people of the upper towers of Sharn feed pigeons, ground-dwellers feed rubber ducklings. Many have even been observed in the wild several miles up the Dagger to react positively to the presence of a humanoid, expecting food. Sharnites have taken to them so well in fact that breeding programs and unofficial "rubber duckling races" are held during the height of the rainy season. When the waters eventually retreat the ducklings and their new hatchlings follow the river northward to greener waters. A few rubber ducklings have been known to hang around until it's too late, becoming stuck in the drying mud of the former river-bottoms. Primary schools in Sharn use the drying of the Depths as a field trip and educational opportunity on the handling of animals, picking up ducklings and placing them back into the river waters so they can swim back.

--

Recently I've been holding a D&D game for friends set in Eberron. A slightly tweaked version of Eberron. I have no lover for the "so high fantasy it's nearly Sci-Fi" aesthetic that Eberron normally goes for, so I've tried to flavor it by bolstering the industrial revolution and Great War themes it has going on. In addition to a few other things. And, me being me, the first thing I wanted to do was populate it with little creachers. Considering Eberron already has dinosaurs running around, fish-sized hesperornithines wouldn't be too unusual. Also they're just too cute. Like a cross between a duck and a penguin you can hold in the palm of your hand. The little goblin girl knows what's up. (Also, note, please don't feed ducks or fantasy ducks chocolate-chip cookies)

Will this series continue. Maybe. ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

#d&d#eberron#fantasy creature#d&d creature#Hesperornis#hesperornithine#rubber duck#rubber duckling#goblin#sharn

19 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Possibly the closest dinosaurs have ever gotten to adopting a fully aquatic lifestyle, hesperornithines are some of the most remarkable Mesozoic dinosaurs, and they have been known to us for more than a century. Traditionally, loons and grebes have been considered the best functional analogues for them out of all modern diving birds, but a new study put this long-held assumption into question, and I write more about it here.

Image by "Quadell", under CC BY-SA 3.0.

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

Now that Prehistoric Planet is over, I'll compile a list of ideas I'd like to see if we ever get a season 2. This is going to assume we stick to the Maastrichtian, if we open it up to the whole Mesozoic we'll be here all day.

More marine reptile diversity! Would love to see how varied plesiosaurs were, especially Aristonectines, and also just how many niches mosasaurs occupied, including potentially stranger ones like Xenodens. Same for any other reptiles like turtles for that matter.

Honestly, more marine life in general. It wasn't just big reptiles. We saw ammonites briefly, how about more cephalopods? Different fish, we saw pycnodonts briefly, sharks could be nice too? Hell, give us hesperornithines, actual sea dinosaurs.

On the topic of birds, it's wild we didn't get many birds, and none that really got any focus. Already some interesting birds at this time, like various enantiornithines such as avisaurs, weird island birds in Europe, and even neornithines.

On the note of Europe... I'd love to see more Hateg Island. We didn't get to see any of the creatures in-depth, so exploring how islands shape the fauna there would be great. There were even crocodyliformes there! Also, Hatzegopteryx hunting bigger prey.

If we're talking islands, revisiting Madagascar would also be great. Another ecosystem that is quite varied. It may not have dwarf sauropods, but it has many dinosaurs beyond Masiakasaurus, as well as a host of unusual crocodyliformes.

Crocodyliformes in general. We somehow got NONE. Not even baurusuchids, not to mention all the other varied notosuchians out there. There's even the marine dyrosaurs, and close relatives of modern true crocodilians. Gimme weird mammal crocs and terrestrial dino hunter crocs!

Honestly? Mammals also got super snubbed. Mammals were way more diverse than we give them credit for in the Mesozoic, and this would be a perfect place to show it. Gondwanatheres, metatherians, multituberculates, even placentals like possible primate Purgatorius.

In terms of locations, I'd love to see India, especially to see the animals there living in close proximity to the Deccan Traps. Many dinosaurs there too, and even the snake Sanajeh.

For locations we already saw to explore further in depth, maybe also some more Zealandia, Antarctica and South America? Especially for looks at their ecosystems if we have the data for it.

Of course who knows if we'll even get a Season 2, but if we do, hopefully some of these come to pass.

97 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Couple of palaeoart watercolours - the Cretaceous hesperornithine bird Enaliornis and a non-descript Mesozoic mammal at the feet of its reptilian overlords (for now)...

#paleoart#paleontology#dinosaur#bird#seabird#watercolour#painting#natural history#scientific illustration#mesozoic#cretaceous#reptile#earth history#prehistoric

19 notes

·

View notes

Note

Apologies if this sounds dumb, but is it possible for an avian or reptilian (or an ancient both) to evolve teeth inside a beak?

This doesn’t sound dumb at all! In fact, it’s a subject of a bit of debate. Theoretically there’s nothing stopping animals from having teeth inside beaks. That said, animals that have teeth and beaks (such as Ichthyornis, hesperornithines, and various oviraptorosaurs and ornithischians) seem to have the beak and teeth in different parts of the mouth.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fossil Novembirb 2: The Survivors

The End-Cretaceous Extinction was one of the most devastating - and tragic - events on our planet.

In the blink of an eye, the world changed from a thriving biosphere to a decimated one. The asteroid caused worldwide wildfires, tsunamis, and the dramatic release of particles into the air that blocked out the sun.

Nothing over 25 kg could survive, because they had nowhere to hide from the devastation. Anything under that limit had to have somewhere to hide - water or burrowing worked best - and something to eat, which was easier said than done. When the plants can't eat, nothing can.

And yet, life survived - not just life, but dinosaurs themselves!

Conflicto, by @otussketching

In fact, one of the first fossils we have from the Cenozoic is Conflicto, a Presbyornithid - like "Styginetta" and Teviornis yesterday! - from Antarctica

Why these dinosaurs, and no others?

They had beaks, which would have helped them to access available food sources such as seeds and spores (plant material in a protective casing)

They did not live in trees, but usually near or with water - perfect places to hide

They were powerful fliers, allowing them to escape the flames and whatever else they needed to

Other than that? Random chance.

Much of the evolution of life on this planet is down to Sheer Dumb Luck

Tsidiiyazhi by Sean Murtha

What happened next was truly remarkable: an adaptive radiation of dinosaurs the likes of which is rarely seen

With all of those newly opened niches, Neornithines adapted quickly, so quickly we can't actually figure out how different major groups of Neoavians - aka, most birds - actually relate to one another.

After all, there was just *so much* free real estate!

Qianshanornis by @alphynix

In fact, many of these dinosaurs evolved right back into niches that their ancestors had famously lived in - penguins show up so quickly that we're giving marine birds their own day, replacing the now-lost Hesperornithines; Tsidiiyazhi and others quickly replaced the empty tree-bird niches left behind by the lost Enantiornithines; and raptors show up quickly too, already reminiscent of the lost Dromaeosaurs.

Qianshanornis, a mysterious raptor from China, had sickle claws just like its lost bretheren! In fact, it looks like it might be a Cariamiform, a group of dinosaurs including living Seriemas and the extinct Terror Birds, which often have sickle claws like Dromaeosaurs did!

Don't fix what isn't broken, I guess!

Australornis by @thewoodparable

Non-Neoavians diversified too, with fowl doing just fine across the boundary - Presbyornithids like Conflicto, as well as mysterious forms like Australornis.

Palaeognaths remain weirdly absent, but don't worry - the earilest ones will show up before the Paleocene epoch is done!

The Cenozoic begins with the Paleogene Period, which has the first epoch of the Paleocene - this was a climatic quagmire, with frequent fluctuations at the beginning before a dramatic rise in temperatures at the end. This climate confusion would affect bird evolution greatly - and lead to the diversification of many kinds, some of which we still have today!

Sources:

Ksepka, D. T., T. A. Stidham, T. E. Williamson. 2017. Early Paleocene landbird supports rapid phylogenetic and morphological diversification of crown birds after the K-PG mass extinction. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 114 (30): 8047 - 8052.

Mayr, 2022. Paleogene Fossil Birds, 2nd Edition. Springer Cham.

Mayr, 2017. Avian Evolution: The Fossil Record of Birds and its Paleobiological Significance (TOPA Topics in Paleobiology). Wiley Blackwell.

168 notes

·

View notes

Note

Joke fringe theory: birds are polyphyletic. Some are oviraptorosaurs, some are troodontids, at least one line are pterosaurs. None of them are related.

You're Grounded

sometimes I joke penguins are hesperornithines

89 notes

·

View notes

Note

An ask from the other day got me wondering... when did dinos lose their teeth? (evolutionarily, I mean, lol). Was this at the same time as the asteroid, as in, the dinos with teeth didn't survive? (because they were larger? Or flightless?) Or did some surviving species have teeth but lost them over time after the impact?

So dinosaurs have lost their teeth many times - there are many lineages of toothless dinosaurs

the line leading to living birds lost their teeth right at that divergence - so the first Neornithines (crown-birds) were toothless, but things right outside of Neornithes (like Hesperornithines) still had teeth

Neornithines were the only dinosaurs to survive because

they were under 25 kg

they were primarily associated with freshwater habitats, which would have provided cover during the global wildfires

they had beaks that they could use to open up tough sources of food, like seeds, which would have been plentiful as opposed to other sources of food (plants and fungi survive mass extinction by putting their gametes in extremely hard casings for protection - but beaks can open those)

at least, that's our current hypothesis

38 notes

·

View notes

Note

Idk I can't vote penguins bc part of my brain tells me there's penguimorphs from the mesozoic that we didn't get to find due to their location and general oceans not preserving fossils as well

we have penguin like dinosaurs from the mesozoic, they're called hesperornithines. and yeah sure there may have been other penguin like things, but penguins have ridiculously heavy bones for dinosaurs and that alone gives them points. in addition, have you SEEN WHAT THEIR FEATHERS LOOK LIKE. in ADDITION addition, nowhere in the mesozoic was it as cold as the antarctic conditions emperors deal with on a regular basis

we've normalized penguins too much. they're bizarre. bizarre I tell you

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

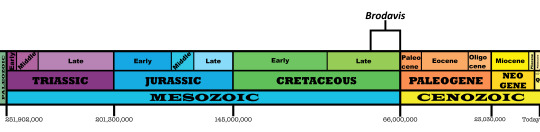

Brodavis

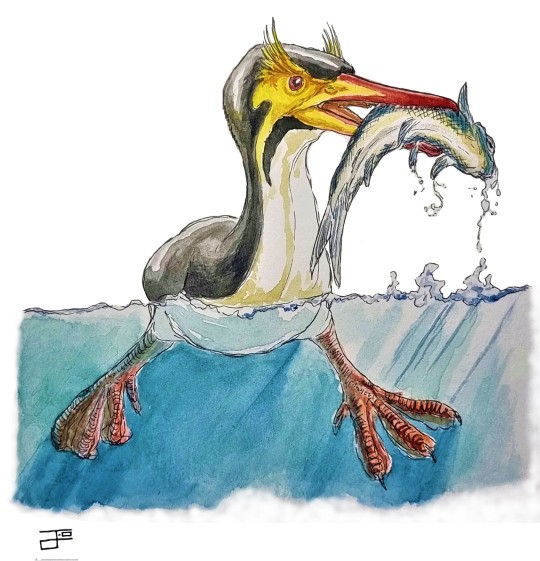

B. americanus by Jack Wood

Etymology: Brodkorb’s Bird

First Described By: Martin et al., 2012

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoromorpha, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostaylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Hesperornithes

Referred Species: B. americanus, B. baileyi, B. mongoliensis, B. varneri

Status: Extinct

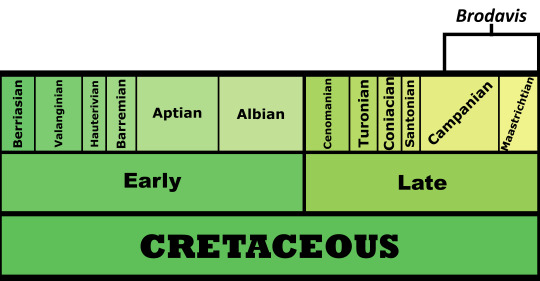

Time and Place: Between 80 and 66 million years ago, from the Campanian to the Maastrichtian ages of the Late Cretaceous

Brodavis is known from a variety of habitats, most within the Western Interior Seaway of North America, with one in Asia: the Frenchman Formation, the Hell Creek Formation, the Pierre Shale Formation, and the Nemegt Formation.

Physical Description: Brodavis was a large bird, but a small dinosaur, reaching up to 90 centimeters in body length (though some species were half that size). It had a cylindrical body and long legs, good for propelling it through the water. It had a lightly built skeleton, though, so it wasn’t well adapted to diving - and may have even still been able to fly, though not particularly well. It had a long, skinny neck, and a small head ending in a long and pointed beak. This beak was full will small, pointy teeth for catching fish. It is unclear whether or not it had webbing between its toes, but this is definitely possible. The colors of Brodavis are poorly known, but it was certainly covered with feathers all over its body.

Diet: Brodavis would have primarily eaten fish and other aquatic life.

Behavior: Being a water-based creature, Brodavis spent most of its time near the water, swimming through along the surface and looking for food. Based on other Hesperornithines, it swam mostly with its feet, propelling them like living animals such as grebes today. Its wings, which were still probably functional, would have not been used in the water. Still, given the presence of flight in Brodavis, it probably would have been able to take off from the water to avoid danger - and back to the water to avoid more danger still, given the large predatory dinosaurs it shared habitats with. It would have then gone to the coasts to rest and rejoin other Brodavis, and would have also had nests there that they had to take care of. How social it was, or other specifics on behavior, are unknown at this time - though it would not be surprising if they lived in large family groups, given how common such behavior is in modern aquatic birds and the fact that it’s a fairly common genus of dinosaur.

B. varneri By Scott Reid

Ecosystem: Being known from a wide variety of habitats, it’s nearly impossible to completely describe everything Brodavis ever lived with in one dinosaur article. That being said, Brodavis tended to live along the coast of major waterways (especially in freshwater areas), where it would spend most of its time underwater but go back to the shores to rest, mate, and take care of their young. Since Brodavis was found both in the Western Interior Seaway and the Seaway of Eastern Asia, it probably would have encountered a wide variety of other dinosaurs. In the Canadian Frenchman Formation, for example, it would have encountered the small herbivore Thescelosaurus, the large hadrosaur Edmontosaurus, the horned dinosaurs Triceratops and Torosaurus, the ostrich-like Ornithomimus, and the large predator Tyrannosaurus. In Hell Creek the companions of Brodavis were many, but included other dinosaurs like Tyrannosaurus, Ornithomimus, Triceratops, Torosaurus, Edmontosaurus, and Thescelosaurus like the Frenchman Formation - but also ankylosaurs like Denversaurus and Ankylosaurus, pachycephalosaurs like Sphaerotholus and Pachycephalosaurus, the small ceratopsian Leptoceratops, another ostrich-like dinosaur Struthiomimus, the chickenparrot Anzu, the raptor Acheroraptor, the opposite bird Avisaurus, and the modern bird Cimolopteryx - and more! In the Pierre Shale, Brodavis was accompanied by other Hesperornithines like Baptornis and Hesperornis. And, finally, in the Nemegt, Brodavis lived with another Hesperornithine Judinornis, the duck Teviornis, the ankylosaur Tarchia, the hadrosaur Saurolophus, the pachycephalosaurs Prenocephale and Homalocephale, the titanosaur Nemegtosaurus, the tyrannosaurs Alioramus and Tarbosaurus, Duck Satan Himself Deinocheirus, the ostrich-mimics Anserimimus and Gallimimus, the alvarezsaur Mononykus, the therizinosaur Therizinosaurus, the chickenparrots Avimimus, Elmisaurus, Nomingia, and Nemegtomaia; the raptor Adasaurus, and the troodontid Zanabazar. Given this wide variety of habitats and neighbors, Brodavis was probably able to live in freshwater habitats, unlike other hesperornithines, and it was decidedly a very adaptable dinosaur.

B. baileyi by Scott Reid

Other: Brodavis represents a unique group of Hesperornithines, though it’s possible the genus is overlumped, which would make the family that currently only has Brodavis in it (Brodavidae) actually informative.

Species Differences: These species differ mainly on where they’re from - B. americanus from the Frenchman Formation, B. baileyi from the Hell Creek Formation, B. mongoliensis from the Nemegt, and B. varneri from the Pierre Shale. As such, B. varneri is the oldest of the four, and may be its own genus. It is also the best known species.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources under the Cut

Aotsuka, K. and Sato, T. (2016). Hesperornithiformes (Aves: Ornithurae) from the Upper Cretaceous Pierre Shale, Southern Manitoba, Canada. Cretaceous Research, (advance online publication).

Bakker, R. T., Sullivan, R. M., Porter, V., Larson, P. and Saulsbury, S. J. (2006). "Dracorex hogwartsia, n. gen., n. sp., a spiked, flat-headed pachycephalosaurid dinosaur from the Upper Cretaceous Hell Creek Formation of South Dakota". in Lucas, S. G. and Sullivan, R. M., eds., Late Cretaceous vertebrates from the Western Interior. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 35, pp. 331–345.

Boyd, Clint A.; Brown, Caleb M.; Scheetz, Rodney D.; Clarke; Julia A. (2009). "Taxonomic revision of the basal neornithischian taxa Thescelosaurus and Bugenasaura". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 29 (3): 758–770.

Campione, N.E. and Evans, D.C. (2011). "Cranial Growth and Variation in Edmontosaurs (Dinosauria: Hadrosauridae): Implications for Latest Cretaceous Megaherbivore Diversity in North America." PLoS ONE, 6(9): e25186.

Carpenter, K. (2003). "Vertebrate Biostratigraphy of the Smoky Hill Chalk (Niobrara Formation) and the Sharon Springs Member (Pierre Shale)." High-Resolution Approaches in Stratigraphic Paleontology, 21: 421-437.

Estes, R.; Berberian, P. (1970). "Paleoecology of a late Cretaceous vertebrate community from Montana". Breviora. 343.

Glass, D.J., editor, 1997. Lexicon of Canadian Stratigraphy, vol. 4, Western Canada. Canadian Society of Petroleum Geologists, Calgary, Alberta, 1423.

Gradzinski, R., J. Kazmierczak, J. Lefeld. 1968. Geographical and geological data form the Polish-Mongolian Palaeontological Expeditions. Palaeontologia Polonica 198: 33 - 82.

Henderson, M.D.; Peterson, J.E. (2006). "An azhdarchid pterosaur cervical vertebra from the Hell Creek Formation (Maastrichtian) of southeastern Montana". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 26 (1): 192–195

Jerzykiewicz, T., D. A. Russell. 1991. Late Mesozoic stratigraphy and vertebrates of the Gobi Basin. Cretaceous Research 12 (4): 345 - 377.

Kielan-Jaworowska, Z., R. Barsbold. 1972. Narrative of the Polish-Mongolian Palaeontological Expeditions 1967-1971. Palaeontologia Polonica 27: 5 - 136.

Lerbekmo, J.F., Sweet, A.R. and St. Louis, R.M. 1987. The relationship between the iridium anomaly and palynofloral events at three Cretaceous-Tertiary boundary localities in western Canada. Geological Society of America Bulletin, 99:25-330.

Longrich, N. (2008). "A new, large ornithomimid from the Cretaceous Dinosaur Park Formation of Alberta, Canada: Implications for the study of dissociated dinosaur remains". Palaeontology. 54 (1): 983–996.

Longrich, N.R., Tokaryk, T. and Field, D.J. (2011). "Mass extinction of birds at the Cretaceous–Paleogene (K–Pg) boundary." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108(37): 15253-15257.

Novacek, M. 1996. Dinosaurs of the Flaming Cliffs. Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group Inc. New York, New York.

Martin, L. D., E. N. Kurochkin, T. T. Tokaryk. 2012. A new evolutionary lineage of diving birds from the Late Cretaceous of North America and Asia. Palaeoworld 21: 59 - 63.

Martyniuk, M. P. 2012. A Field Guide to Mesozoic Birds and other Winged Dinosaurs. Pan Aves; Vernon, New Jersey.

Pearson, D. A.; Schaefer, T.; Johnson, K. R.; Nichols, D. J.; Hunter, J. P. (2002). "Vertebrate Biostratigraphy of the Hell Creek Formation in Southwestern North Dakota and Northwestern South Dakota". In Hartman, John H.; Johnson, Kirk R.; Nichols, Douglas J. (eds.). The Hell Creek Formation and the Cretaceous-Tertiary boundary in the northern Great Plains: An integrated continental record of the end of the Cretaceous. Geological Society of America. pp. 145–167.

Tokaryk, T. 1986. Ceratopsian dinosaurs from the Frenchman Formation (Upper Cretaceous) of Saskatchewan. Canadian Field-Naturalist 100:192–196.

Varricchio, D. J. 2001. Late Cretaceous oviraptorosaur (Theropoda) dinosaurs from Montana. pp. 42–57 in D. H. Tanke and K. Carpenter (eds.), Mesozoic Vertebrate Life. Indiana University Press, Indianapolis, Indiana.

Watabe, M., S. Suzuki, K. Tsogtbaatar, T. Tsubamoto, M. Saneyoshi. 2010. Report of the HMNS-MPC Joint Paleontological Expedition in 2006. Hayashibara Museum of Natural Sciences Reasearch Bulletin 3:11 - 18.

Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; and Osmólska, Halszka (eds.): The Dinosauria, 2nd, Berkeley: University of California Press. 861 pages.

#Brodavis#Euornithine#Hesperornithine#Bird#Dinosaur#Theropod Thursday#Piscivore#North America#Eurasia#Cretaceous#Brodavis americanus#factfile#Brodavis baileyi#Brodavis mongoliensis#Brodavis varneri#Birds#Dinosaurs#prehistoric life#paleontology#prehistory#birblr#palaeoblr#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature

182 notes

·

View notes

Text

Baptornis advenus

By José Carlos Cortés on @quetzalcuetzpalin-art

PLEASE SUPPORT US ON PATREON. EACH and EVERY DONATION helps to keep this blog running! Any amount, even ONE DOLLAR is APPRECIATED! IF YOU ENJOY THIS CONTENT, please CONSIDER DONATING!

Name: Baptornis advenus

Name Meaning: Diving Bird

First Described: 1877

Described By: Marsh

Classification: Dinosauria, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Hesperornithes

Baptornis is our first decidedly in-order Hesperornithine, the group of diving, eventually fully aquatic & flightless almost-birds that so well occupy depictions of Late Cretaceous dinosaurian life. Baptornis is one that was fully aquatic, so not a transitional Hesperornithine - weirdly enough, the ones that show the process from an Ichthyornis-like ancestor to the weird and highly specialized Hesperornis are coming later in the week because I’m bad at scheduling. Baptornis was described a while ago, by Marsh, and this makes it one of the first Mesozoic near-birds described by paleontologists. It was found in the Niobrara Formation of Kansas, and as such, lived in the great Western Interior Seaway of North America, in the Coniacian to Campanian ages of the Late Cretaceous, about 83 or so million years ago. It is known from an extensive amount of material, possibly even more than Hesperornis itself.

By Scott Reid on @drawingwithdinosaurs

It had a wingspan of about 36 centimeters, and its body length was about 70 centimeters, though the length of its tail is unknown. It had a long and slender head with a slim toothed snout, as well as a long and slender neck, allowing it to dive and grab fish in its mouth. It had a cylindrical body and its wings really weren’t used for much of anything, though its legs were long. It was the smallest Hesperornithine in the Western Interior Seaway, and as such it probably lived in shallower water and fed on smaller fish, such as herring-like fish, and other small ocean foods than its close by relatives. It also had webbed feet, and was very clumsy on land, pushing itself around rather than walking, because its legs would have been tucked into its body and the feet spread out - it might have been able to waddle or hop, more so than Hesperornis, but still not great.

Sources:

Martyniuk, M. P. 2012. A Field Guide to Mesozoic Birds and other Winged Dinosaurs. Pan Aves; Vernon, New Jersey.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Baptornis

Shout out goes to @invisiblecake!

#baptornis#baptornis advenus#bird#hesperornithine#dinosaur#invisiblecake#birblyfe#palaeoblr#paleontology#prehistory#prehistoric life#dinosaurs#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature#factfile#Dìneasar#דינוזאור#डायनासोर#ديناصور#ডাইনোসর#risaeðla#ڈایناسور#deinosor#恐龍#恐龙

127 notes

·

View notes

Text

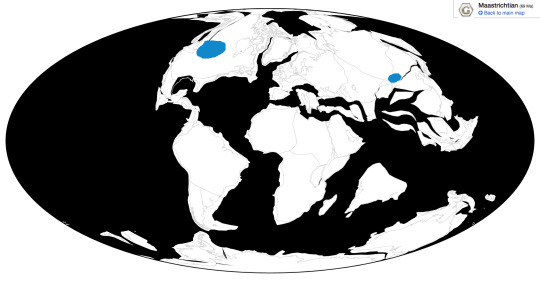

Enaliornis barretti, E. sedgwicki, E. seeleyi

By José Carlos Cortés on @quetzalcuetzpalin-art

PLEASE SUPPORT US ON PATREON. EACH and EVERY DONATION helps to keep this blog running! Any amount, even ONE DOLLAR is APPRECIATED! IF YOU ENJOY THIS CONTENT, please CONSIDER DONATING!

Name: Enaliornis barretti, E. sedgwicki, E. seeleyi

Name Meaning: Seabird

First Described: 1876

Described By: Seeley

Classification: Dinosauria, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Hesperornithes

Enaliornis is th eoldest known Hesperornithine, and it also is one that shows the transition from an Ichthyornis-esque ancestor to highlight specialized diving dinosaurs such as Hesperornis the best, as it was a small, swimming animal that also could dive, but were much more similar to “conventional” Euronithes. It was similar to loons and ducks, in a way, with a much more squat body. It lived in the Cambridge Greensand Formation of England, about 100 million years ago, in the Albian age of the Early Cretaceous to the Cenomanian age of the Late Cretaceous. It had a small skull and long legs for paddling and coastal diving, and it may have been a dipper, an dit probably could still fly. It had a body length of about 55 centimeters.

Sources:

Martyniuk, M. P. 2012. A Field Guide to Mesozoic Birds and other Winged Dinosaurs. Pan Aves; Vernon, New Jersey.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Enaliornis

Shout out goes to @frsphoto!

#enaliornis#bird#dinosaur#hesperornithine#birblr#palaeoblr#enaliornis barretti#enaliornis sedgwicki#enaliornis seeleyi#paleontology#prehistory#prehistoric life#dinosaurs#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature#factfile#Dìneasar#דינוזאור#डायनासोर#ديناصور#ডাইনোসর#risaeðla#ڈایناسور#deinosor#恐龍

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

Asiahesperornis bazhanovi

By Jack Wood on @thewoodparable

PLEASE SUPPORT US ON PATREON. EACH and EVERY DONATION helps to keep this blog running! Any amount, even ONE DOLLAR is APPRECIATED! IF YOU ENJOY THIS CONTENT, please CONSIDER DONATING!

Name: Asiahesperornis bazhanovi

Name Meaning: Asian Western Bird

First Described: 1991

Described By: Nessov & Prizemlin

Classification: Dinosauria, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Hesperornithes, Hesperornithidae

Asiahesperornis is a poorly known, fragmentary Hesperornithid from the Priozernyi Quarry of the Kushmuran Formation of Kazakhstan, living sometime between 70 and 66 million years ago, in the Maastrichtian age of the Late Cretaceous. It is known mainly from fragments of the limb, though those have been able to inform researchers that it was very closely related to derived Hesperornithines like Hesperornis itself. It had robust, short legs like other Hesperornithids, which would have been used for diving and propelling through the water. A marine-dwelling animal, it would have lived in the Turgay Strait, a shallow sea in Siberia and central Asia, which existed in the Cretaceous through the Oligocene of the Cenozoic. As such, it probably fed on fish and other animals in this sea. Recently, it was suggested that Asiahesperornis is actually a species of Parahesperornis, a better known Hesperornithid - it had similar toes, and in general the two are more similar to each other than they are to Hesperornis, though two species of Hesperornis are more similar to them than to Hesperornis (specifically, H. crassipes and H. chowi,) with these three seemingly adapted for coastal living near a large sea. As such, it is entirely possible that Asiahesperornis will be sunk into Parahesperornis in the future, though for now, it has not been confirmed through phylogenetic analysis.

Sources:

http://fossilworks.org/?a=taxonInfo&taxon_no=120326

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Turgai_Sea

Dyke, G. J., D. V. Malakhov, L. M. Chiappe. 2006. A re-analysis of the marine bird Asiahesperornis from northern Kazakhstan. Cretaceous Research 27 (2006): 947 - 953.

Zelenkov, N. V., A. V. Panteleyev, A. A. Yarkov. 2017. New Finds of Hesperornithids in the European Russia, with Comments on the Systematics of Eurasian Hesperornithidae. Paleontological Journal 51 (5): 547 - 555.

Shout out goes to @des4yun0

#asiahesperornis#asiahesperornis bazhanovi#bird#dinosaur#hesperornithine#birblr#palaeoblr#des4yun0#dinosaurs#paleontology#prehistory#prehistoric life#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature#factfile#Dìneasar#דינוזאור#डायनासोर#ديناصور#dínosaurio#risaeðla#ڈایناسور#deinosor#恐龍恐龙#динозавр

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fumicollis hoffmani

By Jack Wood on @thewoodparable

PLEASE SUPPORT US ON PATREON. EACH and EVERY DONATION helps to keep this blog running! Any amount, even ONE DOLLAR is APPRECIATED! IF YOU ENJOY THIS CONTENT, please CONSIDER DONATING!

Name: Fumicollis hoffmani

Name Meaning: Smoke Hills

First Described: 2015

Described By: Bell et al.

Classification: Dinosauria, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Hesperornithes, Hesperornithidae

Fumicollis is a recently described relative of Hesperornis - the almost-modern group of birds that were adapted to diving and swimming in the Cretaceous. It is known from fragments of the skeleton, from the Niobrara Chalk Formation in Kansas, living about 86 million years ago, in the Coniacian age of the Late Cretaceous. It was a fairly small Hesperornithid, compared to such members of the group as Brodavis and Hesperornis especially, though it was also fairly derived and closely related to Hesperornis and Parahesperornis compared to some of the more early derived members of the group. It actually shows a combination of basal traits seen in smaller Hesperornithines, which makes sense as it is a smaller one, as well as derived traits seen in later members - such as Fumicollis itself. This makes Fumicollis an intermediary member of this diving bird group. It was not a very advanced diving bird and thus wouldn’t have been able to dive very extensively compared to its later relatives, and it also would have been much slower underwater. This would have also allowed it to feed on different prey than other Hesperornithines that it shared its environment with in the North American Inland Sea of the Cretaceous, allowing for multiple different types of these birds to all coexist together.

Source:

Bell, A., L. M. Chiappe. 2015. Identification of a New Hesperornithiform from the Cretaceous Neobrara Chalk and Implications for Ecologic Diversity among Early Diving Birds. PLoS ONE 10 (11):e0141690.

Shout out goes to @starborn-vagaboo!

#fumicollis#fumicollis hoffmani#bird#dinosaur#hesperornithine#palaeoblr#birblr#starborn-vagaboo#paleontology#prehistory#prehistoric life#dinosaurs#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature#factfile#Dìneasar#דינוזאור#डायनासोर#ديناصور#ডাইনোসর#risaeðla#ڈایناسور#deinosor#恐龍#恐龙

36 notes

·

View notes