#Carpenters in West Palm Beach

Text

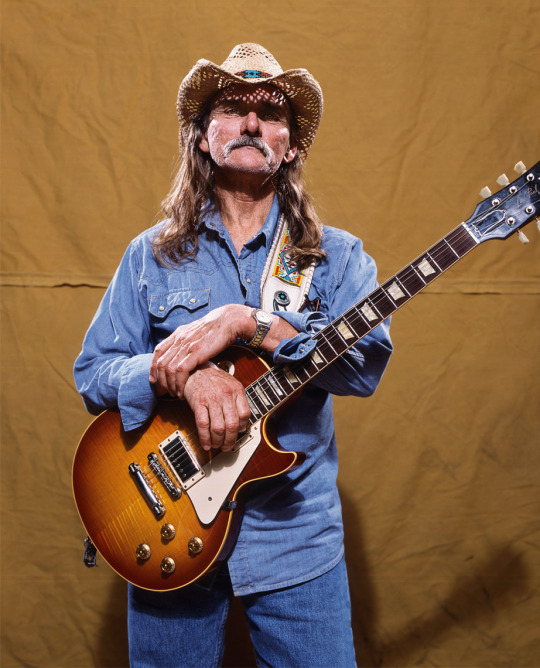

Dickey Betts

Guitarist, singer and founding member of the Allman Brothers Band best known for writing their 1973 hit Ramblin’ Man

Dickey Betts, who has died aged 80, was a founder member of the Allman Brothers Band, one of the most influential US “southern rock” groups of the 1970s. The hard-living outfit blazed out of Jacksonville, Florida, in 1969 with a mix of rock, blues, country and jazz that defined the genre, also influencing artists such as Lynyrd Skynyrd, ZZ Top, the Black Crowes and Kid Rock. They scored several platinum and gold albums and were inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame.

Although the six-piece band was ostensibly led by the blond- haired Allman brothers, Duane and Gregg (guitar and keyboards/vocals respectively), as joint lead guitarist, singer and main songwriter Betts played a crucial role. A larger than life character with his cowboy hats, long moustache and gunslinger good looks, Betts wrote many of the band’s best loved songs, including Jessica, Blue Sky and the 1973 US No 2 smash Ramblin’ Man, inspired by life on the road.

The signature duelling of Betts’s and Duane Allman’s lead guitars rewrote the rule book of how twin guitarists play together - previously one had played lead and the other rhythm. The band’s huge fanbase included President Jimmy Carter, and in 2020 Betts even received the rare accolade of a mention in a Bob Dylan song, when Murder Most Foul contained the line “Play Oscar Peterson, play Stan Getz/Play Blue Sky, play Dickey Betts.”

He was also the inspiration for the rock star character played by Billy Crudup in the former rock journalist Cameron Crowe’s film Almost Famous (2000), the director having been drawn to Betts’s aura of “possible danger and playful recklessness behind his eyes”.

Betts was born in West Palm Beach, Florida, one of the three children of Harold, a carpenter, and his wife, Sarah (nee Brinson), who wrote poetry and played the cornet in a Salvation Army band. Although his father was also a keen fiddler, Dickey’s first instrument was the ukelele, which he started playing aged five, later graduating to the mandolin and the banjo.

He was at West Gate elementary school when he wrote his first song, Seven Years With Pamela, about his sister. He then attended various West Palm Beach schools until seventh grade, dropping out of high school when he was 16, by which time his pursuits included carpentry, hunting and listening to the Grand Ole Opry on the family radio.

Hearing Chuck Berry’s Maybellene in his mid-teens prompted another switch of instrument, as he “started realising that girls like guitars”. He dropped out of high school aged 16 to tour the US with a travelling circus in his first band, the Swinging Saints, but was playing in Second Coming with the bassist Berry Oakley when Duane Allman invited both men to join his new group.

The lineup was completed by the drummer Butch Trucks and – unusually in white-dominated 60s southern rock - a black second drummer, James Lee Johnson, who had previously played with Otis Redding and Percy Sledge.

Although sales of their first two albums were sluggish, Duane Allman’s appearance on Eric Clapton’s 1970 album Layla and Other Assorted Love Songs – which included the classic hit Layla – boosted the heavy-touring Allman Brothers Band’s rising profile. Their 1971 live album At Fillmore East sold 1m copies.

After Duane Allman and Oakley were killed in motorcycle accidents in 1971 and 1972 respectively, Betts led a rejigged lineup. The 1973 album Brothers and Sisters – featuring Ramblin’ Man and the instrumental Jessica, later the theme to the television motoring show Top Gear – topped the US charts for five weeks, while 1975’s Win, Lose Or Draw went into the Top five. By then the band were succumbing to a familiar music industry cocktail of success, drugs, alcohol and feuding.

Betts and Gregg Allman both made solo albums, before Betts felt betrayed when the latter testified against the band’s road manager in a 1976 drugs case and refused to work with him again. Nevertheless, they regrouped in 1978, splitting again in 1982.

A second comeback in 1989 proved more enduring, although in 2000 Betts was fired over his drinking. That third spell in the band had been dogged by alcohol and drug abuse, lawsuits and arrests, and in 1996 he was charged with aggravated domestic assault after pointing a handgun at his fifth wife, Donna (nee Stearns), whom he had married in 1989. The charges were dropped after Betts agreed to enter rehab.

In his later years he returned with his own Dickey Betts Band and played in the band Great Southern with his son Duane. True to his ramblin’ man credentials, he remained on the road to the last, even after brain surgery following a 2018 fall at home, and he released live albums well into his 70s.

He is survived by Donna and his children, Kimberly, Christy, Jessica and Duane.

🔔 Forrest Richard Betts, musician, singer and songwriter, born 12 December 1943; died 18 April 2024

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at Just for Books…?

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tigers Thump Twins 12-3.

Tigers 12 Twins 3 W-Mize (3-1) L-Varland (1-1)

The Minnesota Twins had their last off day of the spring yesterday. They returned to action today against the Tigers. Detroit was ready from the start as Zack McKinstry led-off with a single and Matt Vierling walked. Kerry Carpenter singled home a run to put the Tigers on the board before the Twins grabbed a bat. Detroit quickly loaded up the bases in the second and Ryan Kreidler lined a run-scoring single to left. Zack McKinstry followed with a sac fy to center and Matt Vierling lined an RBI single to left. This gave the Tigers a five-run lead after two frames. Detroit kept adding on in the fourth as Ryan Kreider was hit by a pitch and Zack McKinstry singled to right. Matt Vierling hit a sac fly tto center and Carson Kelly drilled a Louie Varland fastball out to left-center for a two-run homer. The Tigers had an eight-run lead in a blink of an eye. Detroit kept adding on when Matt Vierling took Steven Okert deep in the sixth. The Twins finally found some offense in the seventh when Ryan Jeffers drilled a Joey Wentz fastball out to left for a solo homer. The Tigers would answer in the ninth when Bligh Madris reached on catcher's interference and Anthony Bemboom walked. Josh Crouch blasted a Jorge Alcala fastball out to left for a three-run homer. The Tigers took a 12-1 lead, but the Twins would rally in the bottom of the ninth. Will Holland dumped a single to left and Mike Helman doubled him home. Later in the inning, Chris Williams doubled home a run and the Twins had some life. Miguel Diaz eventually got out of the ninth and the Tigers picked up the win in Fort Myers today.

-Final Thoughts- Louie Varland got knocked around today. He went four innings and allowed eight runs on nine hits with three walks. Jay Jackson retired all five men he faced, Steven Okert got four outs and allowed a run with a strikeout, and Jeff Brigham struck out the sixth in the eighth. Jorge Alcala gave up the homer to Josh Crouch then exited the game after catching a hot liner back to him. Miguel Rodriguez got out of the ninth. The Twins scattered seven hits and went 1-for-5 with runners in scoring position. They left five men on base. The Twins will head over to West Palm Beach tomorrow and play the Nationals. Cole Sands gets the start for the Twins.

-Chris Kreibich-

0 notes

Text

Custom Kitchen Cabinets In West Palm Beach

Ultracraft presents an unlimited choice of cabinet types, together with seventy five door styles of various materials and unlimited custom modifications at no charge. UltraCraft Cabinets are additionally backed with an astounding 100-year Warranty. Additionally, we provide custom kitchen cabinets west palm beach a fantastic choice of residential cabinets- from inventory cabinets (ready-to-assemble), to semi-custom lines, all the way up to a totally custom kitchen or tub.

You can go to our custom cabinet design showroom and choose the cupboards exactly the way they will look in your kitchen. Another kitchen fad that you just should try – particularly if you're kitchen cabinets west palm beach florida not a fan of neutral kitchen designs – is a two-tone kitchen! Instead of choosing just one dominant colour and bringing it out in your cabinetry, why not opt for two robust colors that demand attention?

During the evaluation course of your sales rep shall be assigned, your pricing will be established and your account might kitchen countertops west palm beach be activated. Join the AD PRO Directory, our record of trusted design professionals. Diane Keaton went full throttle with shade in this kitchen.

Depending on the features you’re in search of, the semi-custom options may be ready a bit sooner and could price a bit lower than bespoke cabinetry. The custom cabinetry West Palm Beach constructed at Maurice’s Furnishings contains gorgeous closets, vanities, kitchen cabinets, kitchen islands, and media facilities. Many of our purchasers recognize the ability to help design their custom-built cabinetry, whether to increase custom kitchen cabinets west palm beach fl functionality or to have certain options in a cherished focus of their house. A sure type of self-importance may be a client’s dream, or a kitchen island with a selected sort of storage or seating could additionally be desired. Maurice’s expert builders can achieve elaborate ideas in beautiful cabinetry. Reclaimed wood is the fabric used at Maurice’s Furnishings to create matchless cabinetry.

A cabinet maker can offer full flexibility so that you get the most out of your house. They’ll bring design know-how to the table and will take notice of details that should add as a lot as a great-looking and efficient use of house. They’ll also be acquainted with frequent sizing restraints, uncommon wood types and finishes, and complex design parts. To top it all kitchen cabinets west palm beach off, N-Hance cabinet refinishing in West Palm Beach is highly affordable. Our refinishing services price a fraction of what it would cost to recolor, reface, or restyle your kitchen cabinets, making us a budget-friendly alternative to traditional remodeling. Our skilled designers will work carefully with you to find out your design objectives and assist you to choose the look and structure of your new kitchen or toilet.

Zimmerman Kitchen Design presents free design, and free estimates. After a buy order is made, we offer top of the road installation to ensure all work is finished west palm beach kitchen cabinets to the highest normal. Cabinet Refinishing Cabinets play a big position in the way in which that your kitchen appears.

These traces, plus Knapp’s signature custom line of cabinetry, Liliana Christine, may be seen at the state-of-the-art Knapp Showroom on South Olive Avenue in the coronary heart of West Palm Beach. As a premier high-end kitchen and bath supplier, Knapp companies Palm Beach Island, Jupiter and different pockets and communities throughout Palm Beach County. For updating a kitchen that's functionally already terrific, or has "good bones!" Our whole kitchen cabinets west palm beach fl team of specialists- carpenters, tile, wooden flooring, gra.. With the quick turnaround time on our kitchen cabinets, it can save you money and get what you need sooner than ever earlier than. We manufacture all of those in South Florida so in phrases of shopping for your subsequent set from us-you’ll solely have 4 or eight weeks to attend.

0 notes

Text

Carpenters West Palm Beach

Hire the Best Carpenters in West Palm Beach!

At Custom Carpentry Solutions, we are the experts when it comes to all things carpentry.

Our carpenters in West Palm Beach and its surrounding areas are the best in the business.

We are here to help bring your space to life. Book an Appointment Today!

#Carpentry Services#Carpenters in West Palm Beach#Custom Carpentry Solutions#Custom Decks and Carpentry

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Riddle House

Riddle House is located in West Palm Beach, Florida. This house is an old historic Victorian, and was built in 1905. It seems as though this house is unique in the fact that it doesn’t like men. Any males that visit the house have had ghostly activity performed on them that often turns into a physical nature. Steve Carr is a local carpenter in the West Palm Beach area who was working on the house. One day, the lid from an iron pot lifted three feet in the air, flung across the room and hit Steve in the head. Following this, Steve will never go back in the house again.

Since the attack on Steve Carr, no male visitors are allowed to go into the attic of the house. The reason why there is such a high activity of paranormal occurrences here is because it is believed that a man hung himself at the location. The image of the man is often seen in the north or west attic windows to other people that can see. Witness Jack Rodriguez claimed that he saw the image of the head and torso of a man in a black suit with a noose tied around his neck, peering down to him.

This man in black is believed to be that of a former boarder who hung himself in the attic. Before the title Riddle House was given to the structure in 1920, it was called the Gate Keeper’s Cottage. This was because it functioned as a funeral parlor and management for the Woodlawn Cemetery that is across the street. It was built on land owned by Joseph Jefferson, whom was one of the most famous actors of his time. Karl Riddle then became the first city manager and superintendent of Public Works, then following this he adopted the house as his home.

Moving into the 1980s, Riddle House served as the female dormitory for Palm Beach Atlantic College. However, it was abandoned due to disrepair, and the city threatened to demolish it. To settle the matter, the house was donated to John Riddle, who was the nephew of Karl. It was then split up into three sections and moved to Yesteryear Village. The diary of Karl Riddle tells the story of the death of a man on the property, but gives no concrete details.

Unexplained incidents started to occur almost immediately after it was moved. All sorts of investigators including psychologists, parapsychologists, and paranormal investigators have been to the attic. Many experiences with these professionals ensued. These experiences include revealing of orbs, temperature increases, and spirit energy. The most astounding result of the research was communicating with the dead spirit that haunts the attic. The spirit allegedly said that he took the fall for a crime that he didn’t commit.

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Fiona Apple’s Art of Radical Sensitivity

For years, the elusive singer-songwriter has been working, at home, on an album with a strikingly raw and percussive sound. But is she prepared to release it into the world?

by Emily Nussbaum for The New Yorker

Fiona Apple was wrestling with her dog, Mercy, the way a person might thrash, happily, in rough waves. Apple tugged on a purple toy as Mercy, a pit-bull-boxer mix, gripped it in her jaws, spinning Apple in circles. Worn out, they flopped onto two daybeds in the living room, in front of a TV that was always on. The first day that I visited, last July, it was set to MSNBC, which was airing a story about Jeffrey Epstein’s little black book.

These days, the singer-songwriter, who is forty-two, rarely leaves her tranquil house, in Venice Beach, other than to take early-morning walks on the beach with Mercy. Five years ago, Apple stopped going to Largo, the Los Angeles venue where, since the late nineties, she’d regularly performed her thorny, emotionally revelatory songs. (Her song “Largo” still plays on the club’s Web site.) She’d cancelled her most recent tour, in 2012, when Janet, a pit bull she had adopted when she was twenty-two, was dying. Still, a lot can go on without leaving home. Apple’s new album, whose completion she’d been inching toward for years, was a tricky topic, and so, during the week that I visited, we cycled in and out of other subjects, among them her decision, a year earlier, to stop drinking; estrangements from old friends; and her memories of growing up, in Manhattan, as the youngest child in the “second family” of a married Broadway actor. Near the front door of Apple’s house stood a chalkboard on wheels, which was scrawled with the title of the upcoming album: “Fetch the Bolt Cutters.”

One afternoon, Apple’s older sister, Amber, arrived to record vocal harmonies. In the living room, there was an upright piano, its top piled with keepsakes, including a stuffed toucan knitted by Apple’s mother and a photograph of Martha Graham doing a backbend. Apple’s friend Zelda Hallman, who had not long ago become her housemate, was in the sunny yellow kitchen, cooking tilapia for Mercy and for Hallman’s Bernese mountain dog, Maddie. In the back yard, there was a guesthouse, where Apple’s half brother, Bran Maggart, a carpenter, lived. (For years, he’d worked as a driver for Apple, who never got a license, and helped manage her tours.) Apple’s father, Brandon Maggart, also lives in Venice Beach; her mother, Diane McAfee, a former dancer and actress, remains in New York, in the Morningside Heights apartment building where Apple grew up.

Amber, a cabaret singer who records under the name Maude Maggart, had brought along her thirteen-month-old baby, Winifred, who scooched across the floor, playing under the piano. Apple was there when Winifred was born, and, as we talked about the bizarreness of childbirth, Apple told me a joke about a lady who got pregnant with twins. Whenever people asked the lady if she wanted boys or girls, she said, “I don’t care, I just want my children to be polite!” Nine months passed, but she didn’t go into labor. A year went by—still nothing. “Eight, nine, twenty years!” Apple said, her eyebrows doing a jig. “Twenty-five years—and finally they’re, like, ‘We have to figure out what’s going on in there.’ ” When doctors peeked inside, they found “two middle-aged men going, ‘After youuuu!’ ‘No, after youuuu! ’ ”

Amber was there to record one line: a bit of harmony on “Newspaper,” one of thirteen new songs on the album. Apple, who wore a light-blue oxford shirt and loose beige pants, her hair in a low bun, stood by the piano, coaching Amber, who sat down in a wicker rocking chair, pulling Winifred onto her lap. “It’s a shame, because you and I didn’t get a witness!” Apple crooned, placing the notes in the air with her palm. Then the sisters sang, in harmony, “We’re the only ones who know!” The “we’re” came out as a jaunty warble, adding ironic subtext to the song, which was about two women connected by their histories with an abusive man. Apple, with her singular smoky contralto, modelled the complex emotions of the line for Amber, warming her up to record.

“Does that work?” Apple asked Winifred, who gazed up from her mother’s lap. Abruptly, Apple bent her knees, poked her elbows back like wings, and swung her hips, peekabooing toward Winifred. The baby laughed. It was simultaneously a rehearsal and a playdate.

“Fetch the Bolt Cutters” is a reference to a scene in “The Fall,” the British police procedural starring Gillian Anderson as a sex-crimes investigator; Anderson’s character calls out the phrase after finding a locked door to a room where a girl has been tortured. Like all of Apple’s projects, this one was taking a long while to emerge, arriving through a slow-drip process of creative self-interrogation that has produced, over a quarter century, a narrow but deep songbook. Her albums are both profoundly personal—tracing her heartaches, her showdowns with her own fragility, and her fierce, phoenix-like recoveries—and musically audacious, growing wilder and stranger with each round. As her 2005 song “Extraordinary Machine” suggests, whereas other artists might move fast, grasping for fresh influences and achieving superficial novelty, Apple prides herself on a stickier originality, one that springs from an internal tick-tock: “I still only travel by foot, and by foot it’s a slow climb / But I’m good at being uncomfortable, so I can’t stop changing all the time.”

The new album, she said, was close to being finished, but, as with the twins from the joke, the due date kept getting pushed back. She was at once excited about these songs—composed and recorded at home, with all production decisions under her control—and apprehensive about some of their subject matter, as well as their raw sound (drums, chants, bells). She was also wary of facing public scrutiny again. Fame has long been a jarring experience for Apple, who has dealt since childhood with obsessive-compulsive disorder, depression, and anxiety.

After a while, she and Amber went into a small room—Apple’s former bedroom, where, for years, she had slept on a futon with Janet. After the dog died, she’d found herself unable to fall asleep there, and had turned the room into a recording studio, although it looked nothing like one: it was cluttered, with one small window and no soundproofing. There was a beat-up wooden desk and a computer on which Apple recorded tracks, using GarageBand. There was a mike stand and a Day of the Dead painting of a smiling female skeleton holding a skeleton dog. Every surface, from the shelves to the floor, was covered in a mulch of battered percussion instruments: bells, wooden blocks, drums, metal squares.

The sisters recorded the lyric over and over, with Apple at the computer and Amber standing, Winifred on her hip. During one take, Amber pulled the neck of her turquoise leotard down and began nursing her daughter. Apple looked up from GarageBand, caught her sister’s eye, and smiled. “It’s happening—it’s happening,” she said.

When you tell people that you are planning to meet with Fiona Apple, they almost inevitably ask if she’s O.K. What “O.K.” means isn’t necessarily obvious, however. Maybe it means healthy, or happy. Maybe it means creating the volcanic and tender songs that she’s been writing since she was a child—or maybe it doesn’t, if making music isn’t what makes her happy. Maybe it means being unhappy, but in a way that is still fulfilling, still meaningful. That’s the conundrum when someone’s artistry is tied so fully to her vulnerability, and to the act of dwelling in and stirring up her most painful emotions, as a sort of destabilizing muse.

In the nineties, Apple’s emergence felt near-mythical. Fiona Apple McAfee-Maggart, the musically precocious, emotionally fragile descendant of a line of entertainers, was a classically trained pianist who began composing at seven. One night, at the age of sixteen, she was in her apartment, staring down at Riverside Park, when she thought she heard a voice telling her to record songs drawn from her notebooks, which were full of heartbreak and sexual trauma. She flew to L.A., where her father was living, and with his help recorded three songs; they made seventy-eight demo tapes, and he told her to prepare to hustle. Yet the first tape she shared was enough: a friend passed a copy to the music publicist she babysat for, who gave it to Andrew Slater, a prominent record producer and manager. Slater, then thirty-seven, hired a band, booked a studio in L.A., and produced her début album, “Tidal.” It featured such sophisticated ballads as “Shadowboxer,” as well as the hit “Criminal,” which irresistibly combined a hip-hop beat, rattling piano, and sinuous flute; she’d written it in forty-five minutes, during a lunch break at the studio. The album sold 2.7 million copies.

Slater also oversaw a marketing campaign that presented his new artist as a sulky siren, transforming her into a global star and a media target. Diane McAfee remembers that time as a “whirlwind,” recalling the day when her daughter received an advance for “Tidal”—a check for a hundred thousand dollars. “I said, ‘Oh, my God, this is unbelievable!’ ” McAfee told me. They were in their dining room, and Apple was “backing away, not excited.” Because Apple was not yet eighteen, her mother had to co-sign her record contract.

The musician Aimee Mann and her partner, the musician Michael Penn, who was also signed with Slater at the time, remember seeing Apple perform at the Troubadour, in West Hollywood, at a private showcase for “Tidal,” in 1996. Mann glimpsed in the teen-ager the kind of brazen, complex female musicianship that she’d been longing for—a tonic in an era dominated by indie-male swagger. Onstage, Apple was funny and chatty, calling the audience “grownups.” After the show, she did cartwheels in the alley outside. Mann recalled Apple introducing the song “Carrion” with a story about how sometimes there’s a person you go back to, again and again, who never gives you what you need, “and the lesson is you don’t need them.” As Apple’s career accelerated, Mann read a Rolling Stone profile in which Apple spoke about having been raped, at twelve, by a stranger, who attacked her in a stairwell as her dog barked inside her family’s apartment. Mann said that it was unheard of, and inspiring, for a female artist to speak so frankly about sexual violence, without shame or apology. But Apple’s candor made her worry. Mann had experienced her own share of trauma; she’d also collapsed from exhaustion while on tour. “I was afraid of what would happen to her on the road,” she said. “It’s an unnatural way to live.”

In fact, the turn of the millennium became an electric, unstable period for Apple, who was adored by her fans but also mocked, and leered at, by the male-dominated rock press, who often treated her as a tabloid curiosity—a bruised prodigy to be both ogled and pitied. Much of the press’s response was connected to the 1997 video for “Criminal,” whose director, Mark Romanek, has described it as a “tribute” to Nan Goldin’s photographs of her junkie demimonde—although the stronger link is to Larry Clark’s 1995 movie, “Kids,” and to the quickly banned Calvin Klein ads depicting teens being coerced into making porn. When Apple’s oldest friend, Manuela Paz, saw “Criminal,” she was unnerved, not just by the sight of her friend in a lace teddy, gyrating among passed-out models, but also by a sense that the video, for all its male-gaze titillation, had uncannily absorbed the darker aspects of her and Apple’s own milieu—one of teens running around upper Manhattan with little oversight. “How did they know?” Paz asked herself.

Apple’s unscripted acceptance speech at the 1997 MTV Video Music Awards, in which she announced, “This world is bullshit,” further stoked media hostility. The speech, which included her earnestly quoting Maya Angelou and encouraging fans not to model themselves on “what you think that we think is cool,” seems, in retrospect, most shocking for how on target it is (something true of so many “crazy lady” scandals of that period, like Sinéad O’Connor on “Saturday Night Live,” protesting sexual abuse in the Catholic Church). But, by 2000, when Apple had an onstage meltdown at the Manhattan venue Roseland, instability had become her “brand.” She was haunted by her early interviews, like one in Spin, illustrated with lascivious photographs by Terry Richardson, that quoted her saying, “I’m going to die young. I’m going to cut another album, and I’m going to do good things, help people, and then I’m going to die.” Apple’s love life was heavily covered, too: she dated the magician David Blaine (who was then a member of Leonardo DiCaprio’s “Pussy Posse”) and the film director Paul Thomas Anderson, with whom she lived for several years. While Anderson and Apple were together, he released “Magnolia” and she released “When the Pawn . . . ,” her flinty second album, whose full, eighty-nine-word title—a pugilistic verse written in response to the Spin profile—attracted its own stream of jokes.

During this period, Mark (Flanny) Flanagan, the owner of Largo, a brainy enclave of musicians and comedians within show-biz L.A., became Apple’s friend and patron. (In an e-mail to me, he called her “our little champ.”) One day, Apple visited his office, wondering what would happen if she cut off her fingertip—then would her management let her stop touring? Flanagan, disturbed, told her that she could get a note from a shrink instead, and urged her to refuse to do anything she didn’t want to do.

As the decades passed, Apple’s reputation as a “difficult woman” receded. After she left Anderson, in 2002, she holed up in Venice Beach, emerging every few years with a new album: first, “Extraordinary Machine” (2005), a glorious glockenspiel of self-assertion and payback; then the wise, insightful “The Idler Wheel . . .” (2012). She was increasingly recognized as a singer-songwriter on the level of Joni Mitchell and Bob Dylan. The music of other nineties icons grew dated, or panicky in its bid for relevance, whereas Apple’s albums felt unique and lasting. The skittering ricochets of her melodies matched the shrewd wit of her lyrics, which could swerve from damning to generous in a syllable, settling scores but also capturing the perversity of a brain aflame with sensitivity: “How can I ask anyone to love me / When all I do is beg to be left alone?”

Today, Apple still bridles at old coverage of her. Yet she remains almost helplessly transparent about her struggles—she’s a blurter who knows that it’s a mistake to treat journalists as shrinks, but does so anyway. She’s conscious of the multiple ironies in her image. “Everyone has always worried that people are taking advantage of me,” she said. “Even the people who take advantage of me worry that people are taking advantage of me.”

Lurking on Tumblr (where messages from her are sometimes posted on the fan page Fiona Apple Rocks), she can see how much the culture has transformed, becoming one shared virtual notebook. Female singers like Lady Gaga and Kesha now talk openly about having been raped—and, in the wake of #MeToo, it’s more widely understood that sexual violence is as common as rain. Mental illness is less of a taboo, too. In recent years, a swell of teen-age musicians, such as Lorde and Billie Eilish, have produced bravura albums in Apple’s tradition, while young female activists, including Greta Thunberg and Emma González, keep announcing, to an audience more prepared to listen, that this world is bullshit.

Apple knows the cliché about early fame—that it freezes you at the age you achieved it. Because she’d never had to toil in anonymity, and had learned her craft and made her mistakes in public, she’d been perceived, as she put it to me ruefully, as “the patron saint of mental illness, instead of as someone who creates things.” If she wanted to keep bringing new songs into the world, she needed to have thicker skin. But that had never been her gift.

As we talked in the studio, Apple’s band member Amy Aileen Wood arrived, with new mixes. Wood, an indie-rock drummer, was one of three musicians Apple had enlisted to help create the new album; the others were the bassist Sebastian Steinberg, of the nineties group Soul Coughing, and Davíd Garza, a Latin-rock singer-songwriter and guitarist. Wood and Apple told me that their first encounter, at a recording studio two decades ago, was awkward. Apple remembered feeling intimidated by Wood and by her girlfriend, who seemed “tall and cool.” When Wood described something as “rad,” Apple shot back, “Did you really just say rad?” Wood hid in the bathroom and cried.

Now Wood and her father, John Would, a sound engineer, were collaborating with Apple on building mixes from hundreds of homemade takes. (Apple also worked with Dave Way and, later in the process, Tchad Blake.) The earliest glimmers of “Fetch the Bolt Cutters” began in 2012, when Apple experimented with a concept album about her Venice Beach home, jokingly called “House Music.” She also considered basing an album on the Pando—a giant grove of aspens, in Utah, that is considered a single living being—creating songs that shared common roots.

Finally, around 2015, she pulled together the band. She and Steinberg, a joyfully eccentric bassist with a long gray beard, had played live together for years, and had shared intense, sometimes painful experiences, including an arrest, while on tour in 2012, for hashish possession. (Apple spent the night in a Texas jail cell, where she defiantly gave what Steinberg described as “her best vocal performance ever”; she also ended up on TMZ.) Steinberg, who worked with Apple on “Idler Wheel,” said that her new album was inspired by her fascination with the potential of using a band “as an organism instead of an assemblage—something natural.”

The first new song that Apple recorded was “On I Go,” which was inspired by a Vipassana chant; she sang it into her phone while hiking in Topanga Canyon. Back at home, she dug out old lyrics and wrote new ones, and hosted anarchic bonding sessions with her bandmates. “She wanted to start from the ground,” Garza said. “For her, the ground is rhythm.” The band gathered percussive objects: containers wrapped with rubber bands, empty oilcans filled with dirt, rattling seedpods that Apple had baked in her oven. Apple even tapped on her dog Janet’s bones, which she kept in a pretty beige box in the living room. Apple and the other musicians would march around her house and chant. “Sebastian has a low, sonorous voice,” Garza said, of these early meetings. “Amy’s super-shy. I’m like Slim Whitman—we joke my voice is higher than Fiona’s. She has that husky beautiful timbre, and she would just . . . speak her truth. It felt more like a sculpture being built than an album being made.”

Steinberg told me, “We played the way kids play or the way birds sing.” Wood recalled, “We would have cocktails and jam,” adding that it took some time for her to get used to these epic “meditations,” which could veer into emotional chaos. Steinberg recalls “stomping on the walls, on the floor—playing her house.” Once, when Apple was upset about a recent breakup, with the writer Jonathan Ames, she got into a drunken argument with the band members; Wood took her drums to a gig, which Apple misunderstood as a slight, and Apple went off and wrote a bitterly rollicking song about rejection, “The Drumset Is Gone.”

There were more stops and starts. A three-week group visit to the Sonic Ranch recording studio, in rural Texas—where some band members got stoned in pecan fields, Mercy accidentally ate snake poison, and Apple watched the movie “Whiplash” on mushrooms—was largely a wash, despite such cool experiments as recording inside an abandoned water tower. But Garza praised Apple as “someone who really trusts the unknown, trusting the river,” adding, “She’s the queen of it.”

Once Apple returned to Venice Beach, she finally began making headway, rerecording and rewriting songs in uneven intervals, often alone, in her former bedroom. At first, she recorded long, uncut takes of herself hitting instruments against random things; she built these files, which had names like “metal shaker,” “couch tymp,” and “bean drums,” into a “percussion orchestra,” which she used to make songs. She yowled the vocals over and over, stretching her voice into fresh shapes; like a Dogme 95 filmmaker, she rejected any digital smoothing. “She’s not afraid to let her voice be in the room and of the room,” Garza said. “Modern recording erases that.”

The resulting songs are so percussion-heavy that they’re almost martial. Passages loop and repeat, and there are out-of-the-blue tempo changes. Steinberg described the new numbers as closer to “Hot Knife,” an “Idler Wheel” track that pairs Andrews Sisters-style harmonies with stark timpani beats, than to her early songs, which were intricately orchestrated. “It’s very raw and unslick,” he said, of the new work, because her “agenda has gotten wilder and a lot less concerned with what the outside world thinks—she’s not seventeen, she’s forty, and she’s got no reason not to do exactly what she wants.”

Apple had been writing songs in the same notebooks for years, scribbling new lyrics alongside older ones. At one point, as we sat on the floor near the piano, she grabbed a stack of them, hunting for some lines she’d written when she was fifteen: “Evil is a relay sport / When the one who’s burned turns to pass the torch.” “My handwriting is so different,” she marvelled, flipping pages. She found a diary entry from 1997: “I’m insecure about the guys in my band. I want to spend more time with them! But it seems impossible to ever go out and have fun.” Apple laughed out loud, amazed. “I can’t even recognize this person,” she said. “ ‘I want to go out and have fun!’ ”

“Here’s the bridge to ‘Fast as You Can,’ ” she said, referring to a song from “When the Pawn . . . .” Then she announced, “Oh, here it is—‘Evil is a relay sport.’ ” She continued reading: “It breathes in the past and then—” She shot me a knowing glance. “Lots of my writing from then is just, like, I don’t know how to say it: a young person trying to be a writer.” Written in the margin was the word “Help.”

Whenever I asked Apple how she created melodies, she apologized for lacking the language to describe her process (often with an anxious detour about not being as good a drummer as Wood). She said that her focus on rhythm had some connections to the O.C.D. rituals she’d developed as a child, like crunching leaves and counting breaths, or roller-skating around her dining-room table eighty-eight times—the number of keys on a piano—while singing Bob Dylan’s “Like a Rolling Stone.”

But Apple brightened whenever she talked about writing lyrics, speaking confidently about assonance and serendipity, about the joy of having the words “glide down the back of my throat”—as she put it, stroking her neck—when she got them exactly right. She collects words on index cards: “Angel,” “Excel,” “Intel,” “Gel.” She writes the alphabet above her drafts, searching, with puzzle-solver focus, for puns, rhymes, and accidental insights.

The new songs were full of spiky, layered wordplay. In “Rack of His,” Apple sings, like a sideshow barker, “Check out that rack of his! / Look at that row of guitar necks / Lined up like eager fillies / Outstretched like legs of Rockettes.” In the darkly funny “Kick Me Under the Table,” she tells a man at a fancy party, “I would beg to disagree / But begging disagrees with me.” As frank as her lyrics can be, they are not easily decoded as pure biography. She said, of “Rack of His,” “I started writing this song years ago about one relationship, and then, when I finished it, it was about a different relationship.”

When I described the clever “Ladies”—the music of which she co-wrote with Steinberg—as having a vaudeville vibe, Apple flinched. She found the notion corny. “It’s just, like, something I’ve got in my blood that I’m gonna need to get rid of,” she said. Other songs felt close to hip-hop, with her voice used more for force and flow than for melody, and as a vehicle for braggadocio and insults. There was a pungency in Apple’s torch-and-honey voice emitting growls, shrieks, and hoots.

Some of the new material was strikingly angry. The cathartic “For Her” builds to Apple hollering, “Good mornin’! Good mornin’ / You raped me in the same bed your daughter was born in.” The song had grown out of a recording session the band held shortly after the nomination hearings of the Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh; like many women, Apple felt scalded with rage about survivors of sexual violence being disbelieved. The title track came to her later; a meditation on feeling ostracized, it jumps between lucidity and fury. Drumsticks clatter sparely over gentle Mellotron notes as Apple muses, “I’ve been thinking about when I was trying to be your friend / I thought it was, then— / But it wasn’t, it wasn’t genuine.” Then, as she sings, “Fetch the bolt cutters, I’ve been in here too long,” her voice doubles, harmonies turning into a hubbub, and there’s a sudden “meow” sound. In the final moments, dogs bark as Apple mutters, “Whatever happens, whatever happens.”

Partway through, she sings, “I thought that being blacklisted would be grist for the mill.” She improvised the line while recording; she knew that it was good, because it was embarrassing. “It sounds bitter,” she said. The song isn’t entirely despairing, though. The next line makes an impassioned allusion to a song by Kate Bush, one of Apple’s earliest musical heroines: “I need to run up that hill / I will, I will, I will.”

One day during my July visit, Ames, Apple’s ex-boyfriend, stopped by, on his way to the beach. “Mercy, you are so powerful!” he said, as the dog jumped on him. “I’m waiting for her to get calmer, so I can give her a nice hug.” Apple had described Ames to me as her kindest ex, and there was an easy warmth between them. They took turns recalling their love affair, which began in 2006, when Apple attended a performance by Ames at the Moth, the storytelling event, in New York.

For years, Ames had written candid, funny columns in the New York Press about sex and his psychological fragilities, a history that appealed to Apple. They were together for four years, then broke up, in 2010; five years later, they reunited, but the relationship soon ended again, partly because of Ames’s concerns about Apple’s drinking. Ames recalled to Apple that, as the relationship soured, “you would yell at me and call me stupid.” He added that he didn’t have much of a temper, which became its own kind of problem.

“You would annoy me,” Apple said, with a smile.

“I was annoying!” he said, laughing.

They were being so loving with each other—even about the bad times, like when Ames would find Apple passed out and worry that she’d stopped breathing—that it seemed almost mysterious that they had broken up. Then, step by step, the conversation hit the skids. The turn came when Ames started offering Apple advice on knee pain that was keeping her from walking Mercy—a result, she believed, of obsessive hiking. He told her to read “Healing Back Pain,” by John Sarno. The pain, he said, was repressed anger.

At first, Apple was open to this idea—or, at least, she was polite about it. But, when Ames kept looping back to the notion, Apple went ominously quiet. Her eyes turned red, rimmed with tears that didn’t spill. She curled up, pulling sofa cushions to her chest, her back arched, glaring.

It was like watching their relationship and breakup reënacted in an hour. When Ames began describing “A Hundred Years of Solitude” in order to make the point that Apple had a “Márquezian sense of time,” she shot back, “Are you saying that time is like thirty-seven years tied to a tree with me?” Ames used to call her the Negative Juicer, Apple said, her voice sardonic: “I just extract the negative stuff.” She spun this into a black aria of self-loathing, arguing, like a prosecutor, for the most vicious interpretation of herself: “I put it in a thing and I bring out all the bad stuff. And I serve it up to everyone so that they’ll give me attention. And it poisons everyone, so they only listen to it when they’re in fucked-up places—and it’s a good sign when they stop listening to me, because that means that they’re not hurting themselves on purpose.”

Ames pushed back, alarmed. If he’d ever called her the Negative Juicer, he said, he didn’t mean it as an attack on her art—just that she could take a nice experience and find the bad in it. Her music had pain but also so much joy and redemption, he said. But Ames couldn’t help himself: he kept bringing up Sarno.

Somehow, the conversation had become a debate about the confessional nature of their work. Was it a good thing for Apple to keep digging up past suffering? Was this labor both therapeutic and generative—a mission that could help others—or was it making her sick? Ames said that he didn’t feel comfortable exposing himself that way anymore, especially in the social-media age. “It’s a different world!” he said. “You take one line out of context . . .” For more than a decade, Ames has been working in less personal modes; his noir novel “You Were Never Really Here” was recently made into a movie starring Joaquin Phoenix.

Apple said, “I haven’t wanted to drink straight vodka so much in a while.”

“I’m triggering you,” Ames responded.

“You are,” she said, smiling wearily. “It’s not your fault, Jonathan. I love you.”

When Ames stepped out briefly, Apple said that what had frustrated her was the idea that “there was a way out”—that her pain was her choice.

Zelda Hallman, Apple’s housemate, had been sitting with us, listening. She pointed out that self-help books like “The Secret” had the same problem: they made your suffering all your fault.

“Fuck ‘The Secret’!” Apple shouted.

When Ames came back and mentioned Sarno again, Apple interrupted him: “That’s a great way to be in regular life. But if you’re making a song? And you’re making music and there is going to be passion in it and there is going to be anger in it?” She went on, “You have to go to the myelin sheath—you know, to the central nervous system—for it to be good, I feel like. And if that’s not true? Then fuck me, I wasted my fucking life and ruined everything.”

She recalled a day when she had been working on a piano riff that was downbeat but also “fluttering, soaring,” and that reminded her of Ames. She said that he had asked her to name the resulting song “Jonathan.” (The lovely, eerie track, which is on “Idler Wheel,” includes the line “You like to captain a capsized ship.”) “No, no,” he said. “I didn’t!” As Ames began telling his side of the story, Apple said, icily, “I think that water is going to get real cold real soon. You should probably go to the beach.”

He went off to put on his bathing suit. By the time he left, things had eased up. She hugged him goodbye, looking tiny. After Ames was gone, she said that she hated the way she sometimes acted with him—contemptuous, as if she’d absorbed the style of her most unkind ex-boyfriend. But she also said that she wouldn’t have called Ames himself stupid, explaining, “He doesn’t talk the way that I talk, and like my brother talks, and get it all out, like, ‘What the fuck are you talking about? That’s stupid!’ I’m not necessarily angry when I’m doing that.”

The next day, she sent me a video. “We’ve been to the beach!” she announced, panting, as Mercy ran around in the background. “Because it’s her birthday!” Apple had taken Ames’s advice, she said, and gone for a walk, behaving as if she weren’t injured. So far, her knees didn’t hurt. “Soooo . . . he was right all along,” Apple said, her eyes wide. Then she glanced at the camera slyly, the corner of her mouth pulled up. “Orrrrr . . . I just rested my knees for a while.”

Apple goes to bed early; when I visited, we’d end things before she drifted into a smeary, dreamy state, often after smoking pot, which Hallman would pass to her in the living room. Late one afternoon, Apple talked about the album’s themes. She said, of the title, “Really, what it’s about is not being afraid to speak.” Another major theme was women—specifically, her struggle to “not fall in love with the women who hate me.” She described these songs as acts of confrontation with her “shadow self,” exploring questions like “Why in the past have you been so socially blind to think that you could be friends with your ex-boyfriend’s new girlfriend by getting her a gift?” At the time, she thought that she was being generous; now she recognized the impulse as less benign, a way of “campaigning not to be ousted.”

The record dives into such conflicting impulses: she empathizes with other women, rages at them, grows infatuated with them, and mourns their rejection, sometimes all at once. She roars, in “Newspaper,” “I wonder what lies he’s telling you about me / To make sure that we’ll never be friends!” In “Ladies,” she describes, first with amusement, then in a dark chant, “the revolving door which keeps turning out more and more good women like you / Yet another woman to whom I won’t get through.” In “Shameka,” she celebrates a key moment in middle school, when a tough girl told the bullied Apple, “You have potential.”

As a child, Apple longed to be “a pea in a pod” with other girls, as she was, for a while, with Manuela Paz, for whom she wrote her first song. But as an adult she has hung out mainly with men. She does have some deep female friendships, including with Nalini Narayan, an emergency-room nurse, whom she met, in 1997, in the audience at one of her concerts, and who described Apple as “an empath on a completely different level than anyone I’ve met.” More recently, Apple has become close with a few younger artists. The twenty-one-year-old singer Mikaela Straus, a.k.a. King Princess, who recently recorded a cover of Apple’s song “I Know,” called her “family” and “a fucking legend.” Straus said, “You never hear a Fiona Apple line and say, ‘That’s cheesy.’ ” The twenty-seven-year-old actress Cara Delevingne is another friend; she visited Apple’s home to record harmonies on the song “Fetch the Bolt Cutters.” (She’s the one making that kooky “meow.”)

But Apple has more complicated dynamics with a wider circle of friends, exes, and collaborators. Starting with her first heartbreak, at sixteen, she has repeatedly found herself in love triangles, sometimes as the secret partner, sometimes as the deceived one. As we talked, she stumbled on a precursor for this pattern: “Maybe it’s because my mother was the other woman?”

Apple’s parents met in 1969, during rehearsals for “Applause,” a Broadway musical based on “All About Eve.” Her mother, McAfee, was cast as Eve; her father, Maggart, as the married playwright. Maggart was then an actor on the stage and on TV (he’d been on “Sesame Street”); the sexy, free-spirited McAfee was a former June Taylor dancer. Throughout Apple’s childhood, she and her sister regularly visited the home, in Connecticut, where Maggart’s five other children and their mother, LuJan, lived. LuJan was welcoming, encouraging all the children to grow close—but Apple’s mother was not invited. Apple, with an uneasy laugh, told me that, for all the time she’d spent interrogating her past, this link had never crossed her mind.

Her fascination with women seemed tied, too, to the female bonding of the #MeToo era—to the desire to compare old stories, through new eyes. In July, she sent me a video clip of Jimi Hendrix that reminded her of a surreal aspect of the day she was raped: for a moment, when the stranger approached her, she mistook him for Hendrix. During the assault, she willed herself to think that the man was Hendrix. “It felt safer, and strangely it hasn’t ruined Jimi Hendrix for me,” she said. Years later, however, she found herself hanging out with a man who was a Hendrix fan. One night, they did mushrooms at Johnny Depp’s house, in the Hollywood Hills. Depp, who was editing a film, was sober that night; as Apple recalled, he “kind of led” her and her friend to a bedroom, then shut the door and left. “Nothing bad happened, but I felt kind of used and uncomfortable with my friend making out with me,” she said. “I used to just let things happen. I remember I wrote the bridge to ‘Fast as You Can’ in the car on the way home, and he was playing Jimi Hendrix, and my mind was swirling things together.”

That has always been Apple’s experience: the past overlapping with the present, just as it does in her notebooks. Sometimes it recurs through painful flashbacks, sometimes as echoes to be turned into art. The evening at Depp’s house wasn’t a #MeToo moment, she added. “Johnny Depp was a nice guy, and so was my friend. But I think that, at that time, I was struggling with my sexuality, and trying to force it into what I thought it should be, and everything felt dirty. Going out with boys, getting high, getting scared, and going home feeling like a dirty wimp was my thing.”

Apple came of age in a culture that viewed young men as potential auteurs and young women as commodities to be used, then discarded. Although she had only positive memories of her youthful romance with David Blaine, she was disturbed to learn that he was listed in Jeffrey Epstein’s black book. In high school, Apple was friends with Mia Farrow’s daughter Daisy Previn, and during sleepovers at Farrow’s house she used to run into Woody Allen in the kitchen. “There are all these unwritten but signed N.D.A.s all over the place,” she said, about the entertainment industry. “Because you’ll have to deal with the repercussions if you talk.”

She met Paul Thomas Anderson in 1997, during a Rolling Stone cover shoot in which she floated in a pool, her hair fanning out like Ophelia’s. She was twenty; he was twenty-seven. After she climbed out of the water, her first words to him were “Do you smoke pot?” Anderson followed her to Hawaii. (The protagonist of his film “Punch-Drunk Love” makes the same impulsive journey.) “That’s where we solidified,” she told me. “I remember going to meet him at the bar at the Mandarin Oriental Hotel, and he was laughing at me because I was marching around on what he called my ‘determined march to nowhere.’ ”

The singer and the director became an It Couple, their work rippling with mutual influences. She wrote a rap for “Magnolia”; he directed videos for her songs. But, as Apple remembers it, the romance was painful and chaotic. They snorted cocaine and gobbled Ecstasy. Apple drank, heavily. Mostly, she told me, he was coldly critical, contemptuous in a way that left her fearful and numb. Apple’s parents remember an awful night when the couple took them to dinner and were openly rude. (Apple backs this up: “We both attended that dinner as little fuckers.”) In the lobby, her mother asked Anderson why Apple was acting this way. He snapped, “Ask yourself—you made her.”

Anderson had a temper. After attending the 1998 Academy Awards, he threw a chair across a room. Apple remembers telling herself, “Fuck this, this is not a good relationship.” She took a cab to her dad’s house, but returned home the next day. In 2000, when she was getting treatment for O.C.D., her psychiatrist suggested that she do volunteer work with kids who had similar conditions. Apple was buoyant as Anderson drove her to an orientation at U.C.L.A.’s occupational-therapy ward, but he was fuming. He screeched up to the sidewalk, undid her seat belt, and shoved her out of his car; she fell to the ground, spilling her purse in front of some nurses she was going to be working with. At parties, he’d hiss harsh words in her ear, calling her a bad partner, while behaving sweetly on the surface; she’d tear up, which, she thinks, made her look unstable to strangers. (Anderson, through his agent, declined to comment.)

Anderson didn’t hit her, Apple said. He praised her as an artist. Today, he’s in a long-term relationship with the actress Maya Rudolph, with whom he has four children. He directed the video for “Hot Knife,” in 2011; Apple said that by then she felt more able to hold her own—and she said that he might have changed. Yet the relationship had warped her early years, she said, in ways she still reckoned with. She’d never spoken poorly of him, because it didn’t seem “classy”; she wavered on whether to do so now. But she wanted to put an end to many fans’ nostalgia about their time together. “It’s a secret that keeps us connected,” she told me.

Apple was also briefly involved with the comedian Louis C. K. After the Times published an exposé of his sexual misconduct, in 2017, she had faith that C.K. would be the first target of #MeToo to take responsibility for his actions, maybe by creating subversive comedy about shame and compulsion. When a hacky standup set of his was leaked online, she sent him a warm note, urging him to dig deeper.

One of the women C.K. harassed was Rebecca Corry, a standup comedian who founded an advocacy organization for pit bulls, Stand Up for Pits. Apple began working with the group, and, once she got to know Corry, she started to see C.K. in a harsher light. The comedy that she’d admired for its honesty now looked “like a smoke screen,” she said. In a text, she told me that, if C.K. wasn’t capable of more severe self-scrutiny, “he’s useless.” She added, “I SHAKE when I have to think and write about myself. It’s scary to go there but I go there. He is so WEAK.”

At times, Apple questioned her ability to be in any romantic relationship. Last fall, she went through another breakup, with a man she had dated for about a year. “This is my marriage right now,” she said of her platonic intimacy with Zelda Hallman. Apple told me that they’d met in a near-mystical way: while out on a walk, she’d blown a dandelion, wishing for a dog-friend for Mercy, then turned a corner and saw Hallman, walking Maddie. When Apple’s second romance with Ames was ending, she started inviting Hallman to stay over. “I’d have night terrors and stuff,” Apple recalled. “And one day I woke up and she was sitting in the chair—she’d sat there all night, watching me, making sure I was O.K. I was feeling safer with her here.” Apple fantasized about a kind of retirement: in a few years, she and Hallman might buy land back East “and move there with the doggies.”

Hallman, an affable, silver-haired lesbian, grew up poor in Appalachia; after studying engineering at Stanford, she worked in the California energy industry. In the mid-aughts, she moved to L.A. to try filmmaking, getting some small credits. Each woman called their relationship balanced—they split expenses, they said—but Hallman’s role displaced, to some degree, the one Apple’s brother had played. In addition, Hallman sat in on our interviews and at recording sessions; she often took videos, posting them online. They slept on the daybeds in the living room. Apple had made it clear that anyone who questioned her friend’s presence would get cut out. Hallman described their dynamic as like a “Boston marriage—but in the way that outsiders had imagined Boston marriages to be.”

Hallman said that she hadn’t recognized Apple when they met. Initially, she’d mistaken the singer for someone younger, just another Venice Beach music hopeful in danger of being exploited: “I felt relieved when she said she had a boyfriend in the Hills, to take care of her.”

“Oh, my God, you were one of them! ” Apple said, laughing.

After my July visit, Apple began to text me. She sent a recording of a song that she’d heard in a dream, then a recording describing the dream. She texted about watching “8 Mile”—“doing the nothing that comes before my little concentrated spurt of work”—and about reading a brain study about rappers that made her wonder where her brain “lit up” when she sang. “I’m hoping that I develop that ability to let my medial prefrontal cortex blow out the lights around it!” she joked. Occasionally, she sent a screenshot of a text from someone else, seeking my interpretation (a tendency that convinced me she likely did the same with my texts).

In a video sent in August, she beamed, thrilled about new mixes that she’d been struggling to “elevate.” “I always think of myself as a half-ass person, but, if I half-assed it, it still sounds really good.” She added that she’d whispered into the bathroom mirror, “You did a good job.”

In another video—broken into three parts—she appeared in closeup, in a white tank top, free-associating. She described a colorized photograph from Auschwitz she’d seen on Tumblr, then moved on to the frustrations of O.C.D.—how it made her “freak out about the littlest things, like infants freak out.” She talked about Jeffrey Epstein and the comfort of dumb TV; she held up a “cool metal instrument,” stamped “1932,” that she’d ordered from Greece. Near the end of the video, she wondered why she was rambling, then added, “Oh—I also ate some pot. I forgot about that. Well, knowing me, I’ll probably send this to you!”

Apple’s lifelong instinct has been to default to honesty, even if it costs her. In an era of slick branding, she is one of the last Gen X artists: reflexively obsessed with authenticity and “selling out,” disturbed by the affectlessness of teen-girl “influencers” hawking sponcon and bogus uplift. (When she told an interviewer that she pitied Justin Bieber’s thirsty request for fans to stream his new single as they slept, Beliebers spent the next day rage-tweeting that Apple was a jealous “nobody,” while Apple’s fans mocked them as ignoramuses.)

Apple told me that she didn’t listen to any modern music. She chalked this up to a fear of outside influences, but she had a tetchiness about younger songwriters, too. She had always possessed aspects of Emily Dickinson, in the poet’s “I’m Nobody” mode: pridefulness in retreat. Apple sometimes fantasized about pulling a Garbo: she’d release one final album, then disappear. But she also had something that resembled a repetition compulsion—she wanted to take all the risks of her early years, but this time have them work out right.

When I returned to Venice Beach, in September, the mood was different. Anxiety suffused the house. In July, Apple had been worried about returning to public view, but she was also often playful and energized, tweaking mixes. Now the thought of what she’d recorded brought on paralyzing waves of dread.

To distract herself, she’d turned to other projects. She accepted a request from Sarah Treem, the co-creator of the Showtime series “The Affair,” to cover the Waterboys song “The Whole of the Moon” for the show’s finale. (Apple had also written the show’s potent theme song—the keening “Container.”) Apple agreed to write a jokey song for the Fox cartoon “Bob’s Burgers,” and some numbers for an animated musical sitcom, “Central Park.” She was proud to hit deadlines, to handle her own business. “I have a sense of humor,” she told me. “I’m not that fucking fragile all the time! I’m an adult. You can talk to me.” But, before I arrived one day, she texted that things weren’t going well, so that I’d be prepared.

That afternoon, we found ourselves lounging on the daybeds with Hallman, watching “The Affair.” Apple had already seen these episodes, which were from the show’s penultimate season. In August, she’d sent me a video of herself after watching one, tears rolling down her face. That episode was about the death of Alison, one of the main characters. Played by Ruth Wilson, Alison is a waitress living in Montauk, an intense beauty who is grieving the drowning death of her son and suffers from depression and P.T.S.D. She falls into an affair with a novelist, and both of their marriages dissolve. The story is told from clashing perspectives, but in the episode that Apple had watched, only one account felt “true”: an ex-boyfriend of Alison’s breaks her skull, then drops her unconscious body in the ocean, making her death look like a suicide.

As we watched, Apple took notes, sitting cross-legged on the daybed. She saw herself in several characters, but she was most troubled by an identification with Alison, who worries that she’s a magnet for pain—a victim that men try to “save” and end up hurting. In one sequence, Alison, devastated after a breakup, gets drunk on a flight to California, as her seat partner flirts aggressively, feeding her cocktails. He assaults Alison as she drifts in and out of consciousness. She fights back, complaining to the flight attendant, but the man turns it all around, making her seem like the crazy one; she winds up handcuffed, as other passengers stare at her. Apple found the sequence horrifying—it reminded her of how she came across in her worst press.

Her head lowered and her arms crossed, she began to perseverate on her fears of touring. She ticked off potential outcomes: “I say the right thing, but I look the wrong way, so they say something about the way I look”; “I look the right way, but I say the wrong thing, so they say something mean about what I said.” She went on, “I have a temper. I have lots of rage inside. I have lots of sadness inside of me. And I really, really, really can’t stand assholes. If I’m in front of one, and I happen to be in a public place, and I lose my shit—and that’s a possibility—that’s not going to be any good to me, but I won’t be able to help it, because I’ll want to defend myself.”

Later, we tried to listen to the album. She played the newest version of “Rack of His,” but got frustrated by the tinny compression. She worried that she’d built “a record that can’t be made into a record.” When she’d get mad, or say “fuck,” Mercy would get agitated; wistfully, Apple told me that she sometimes wished she had a small dog that would let her be sad. Despite her fears, she kept recording—at the end of “For Her,” she’d multitracked her voice to form a gospel-like chorus singing, “You were so high”—and said that she wanted the final result to be uncompromising. “I want primary colors,” she said. “I don’t want any half measures.”

We listened to “Heavy Balloon,” a gorgeous, propulsive song about depression. She had added a new second verse, partly inspired by the scene of Alison drowning: “We get dragged down, down to the same spot enough times in a row / The bottom begins to feel like the only safe place that you know.” Apple, curling up on the floor, explained, “It’s almost like you get Stockholm syndrome with your own depression—like you’re kidnapped by your own depression.” Her voice got soft. “People with depression are always playing with this thing that’s very heavy,” she said. Her arms went up, as if she were bouncing a balloon, pretending to have fun, and said, “Like, ‘Ha, ha, it’s so heavy! ’ ” Then we had to stop, because she was having a panic attack.

Apple has tried all kinds of cures. She was sent to a family therapist at the age of eleven, when, mad at her sister, she glibly remarked, on a school trip, that she planned to kill herself and take Amber with her. After she was raped, she spent hours at a Model Mugging class, practicing self-defense by punching a man in a padded suit. In 2011, she attended eight weeks of silent Buddhist retreats, meditating from 5 a.m.to 9 p.m., with no eye contact—it was part of a plan to become less isolated. She had a wild breakthrough one day, in which the world lit up, showing her a pulsing space between the people at the retreat—a suggestion of something larger. That vision is evoked in the new song “I Want You to Love Me,” in which Apple sings, with raspy fervor, of wanting to get “back in the pulse.”

She tried a method for treating P.T.S.D. called eye-movement desensitization and reprocessing therapy, and—around the time she poured her vodka down the drain, in 2018—an untested technique called “brain balancing.” Articles about neurological anomalies fascinated her. The first day we met, Apple spread printouts of brain scans on the floor of her studio, pointing to blue and pink shapes. She was seeking patterns, just as she often did on Tumblr, reposting images, doing rabbit-hole searches that she knew were a form of magical thinking.

Apple doesn’t consider herself an alcoholic, but for years she drank vodka alone, every night, until she passed out. When she’d walk by the freezer, she’d reach for a sip; for her, the first step toward sobriety was simply being conscious of that impulse. She had quit cocaine years earlier, after spending “one excruciating night” at Quentin Tarantino’s house, listening to him and Anderson brag. “Every addict should just get locked in a private movie theatre with Q.T. and P.T.A. on coke, and they’ll never want to do it again,” she joked. She loved getting loose on wine, but not the regret that followed. Her father has been sober for decades, but when Apple was a little kid he was a turbulent alcoholic. He hit bottom when he had a violent confrontation with a Manhattan cabdriver; Apple was only four, but she remembers his bloody face, the nurse at the hospital. When I visited Apple’s mother at her Manhattan apartment, she showed me a photo album with pictures of Apple as a child. One image was captioned “Fiona had too much wine—not feeling good,” with a scribbled sad face. Apple, at two, had wandered around an adult party, drinking the dregs.

For decades, Apple has taken prescription psychopharmaceuticals. She told me that she’d been given a diagnosis of “complex developmental post-traumatic stress disorder.” (It was such a satisfyingly multisyllabic phrase that she preferred to sing it, transforming it into a ditty.) In December, she began having mood swings, with symptoms bad enough that she was told to get an MRI, to rule out a pituitary tumor. In the end, Apple said, she had to wean herself off an antipsychotic that she had been prescribed for her night terrors; the dosage, she said, had been way too high. As she recovered, she felt troubled, sometimes, by a sense of flatness: if she couldn’t feel the emotion in the songs, she said, she wouldn’t be able to tell what worked.

Earlier that fall, she had given an interview to the Web site Vulture, in which she was brassy and perceptive. People responded enthusiastically—many young women saw in Apple a gutsy iconoclast who’d shrugged off the world’s demands. She won praise, too, for having donated a year’s worth of profits from “Criminal”—which J. Lo dances to in the recent movie “Hustlers”—to immigrant criminal-defense cases. But the positive response also threw her, she realized. “Even the best circumstances of being in public may be too much,” she told me.

By January, the situation was better. Apple was no longer having nightmares, although she was still worried, at times, by her moods. One layer of self-protection had been removed when she stopped using alcohol, she said; another was lost with the reduction in medication. And, although she was enthusiastic about some new mixes, she felt apprehensive. She could listen to the tracks, but only through headphones.

So we talked about the subject that made her feel best: the dog rescues she was funding. She paid her brother Bran to pick up the dogs across the country, then drive them to L.A., for placement in foster homes. She and Hallman followed along through videos that Bran sent them. The dogs had been through terrible experiences: one was raped by humans; another was beaten with a shovel. Apple felt that she should not flinch from these details. Rebecca Corry, of Stand Up for Pits, had given her advice for coping: “You have to celebrate small victories and remember their faces and move on to the next one.”

Then, one day, Apple’s band came to her house to listen to the latest mixes. The next afternoon, her face was glowing again. She had wondered if the meeting would be awkward—if the band might disagree on what edits to make. Instead, she and Amy Aileen Wood kept glancing at each other, ecstatic, as they had all the same responses. At last, Apple could listen to the album on speakers.

Afterward, I texted Wood. “Dare I say it was magical?!” Wood wrote. “Everything is sounding so damn good!” Steinberg told me that the notes were simple: “Get out of the way of the music” and let Apple’s voice dominate. Apple knew what she wanted, he said. He described his job as helping her to recognize “that she was her own Svengali.”

It reminded me of a story that Bran had told me, about working in construction. One day, when he was twenty-eight, he strolled out onto a beam suspended thirty-five feet in the air—a task that he’d done many times. Suddenly, he was frozen, terrified of falling. Yet all he had to do was touch something—any object at all—to break the spell. “Because you’re grounded, you can just touch a leaf on a tree and walk,” he said.

Seeing her band again had grounded Apple. She felt a renewed bravado. She’d made plans to rerelease “When the Pawn . . .” on vinyl, but with the original artwork, by Paul Thomas Anderson, swapped out. “That’s just a great album,” she told me. Looking back on her catalogue, she thought that her one weak song might be “Please Please Please,” on “Extraordinary Machine,” which she wrote only because the record company had demanded another track: “Please, please, please, no more melodies.”

In the next few weeks, she sent updates: she was considering potential video directors; she was brainstorming ideas for album art, like a sketch of Harvey Weinstein with his walker. She’d even gone out to see King Princess perform. One night, after petting Janet’s skull and talking to her, Apple went into her old bedroom: she was able to sleep on the futon again, with Mercy. She’d also got a new tattoo, of a black bolt cutter, running down her right forearm.

On the day that Jonathan Ames came over, Apple had pondered the exact nature of her work. Maybe, she suggested, she was like any other artist whose body is an instrument—a ballerina who wears her feet out or a sculptor who strains his back. Maybe she, too, wore herself out. Maybe that’s why she had to take time to heal in between projects. In “On I Go,” the first song she’d written for “Fetch the Bolt Cutters,” she chanted about trying to lead a life guided by inner, rather than outer, impulses: “On I go, not toward or away / Up until now it was day, next day / Up until now in a rush to prove / But now I only move to move.” In the middle of the track, she screwed up the beat for a second and said, “Ah, fuck, shit.” It was a moment almost anyone making a final edit would smooth out. She left it in.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Decoration Ideas that Will Bring Your Living Room to Life

You need to blend your taste and preference, comfort and the beauty aspect in your living room. You have the ideas, but you still do not know how to put them together to bring a clear picture of how you expect your living room to look.

Use materials that are near you. There are a variety things you can do to decorate your living room without spending so much money and still make your living room attractive. Do not to buy new furniture if you do not need it. A highly skilled carpenter can change the couch cover clothes instead of buying a new set. Read more here!

Bring in unique shapes of furniture into the living room. You can use seats of different designs for you to achieve having the unique shapes of furniture. The stools and the tables do not have to be necessarily rectangle, square or round because these are common shapes. You should request for custom-made stools and tables of different shapes like a diamond and also those made of unique materials but will make it look attractive.

Use couch pillows with patterns. The couch pillows can also be of different colors that blend or contrast perfectly. You should use different sizes and shapes of couch pillows if you love shapes. Decorative bright colored couch pillows will make the dark-colored couches to shine. You can have your couch covered with covers of different colors to add uniqueness the living room.

The color of the walls should be the color scheme to guide you when you are choosing color for your furniture. You should work around the colors of the wall so that you can get furniture with color that blends with the wall colors. Bright colored furniture perfect in a room with bright colored walls so that the room does not reflect too much light. You can also bring it dark colored furniture when the walls are of bright color.

You can also use two-in-one furniture. A piece of two-in-one furniture means that the furniture has two different purposes. You can buy a sofa bed that as a seat in the day and the bed in the night. The furniture will tell you space if you have a small house. They are couches with storage. The drawers underneath the couches to enable you to store other items instead of leaving the living room looking messy.

You should consider the sizes of furniture so that they fit in the living room but also leave enough space for movements. The furniture should cover three-quarters of the area in the living room. This will enable you to make the room specials for easy movement. See used furniture West Palm Beach.

For additional info, visit this link - https://www.encyclopedia.com/literature-and-arts/fashion-design-and-crafts/interior-design-and-home-furnishings/furniture

1 note

·

View note

Text

Matt Carpenter Net Worth 2022

Matt Carpenter Net Worth $35miliions Matt Carpenter is an American who plays baseball in the major leagues. Carpenter is an infielder for the MLB team the St. Louis Cardinals. Carpenter made his MLB debut on June 4, 2011, with the Cardinals. Since the beginning of the 2013 season, he has been their main first batter.

He was chosen for the Mountain West Conference's second team three times, and he broke the school record for games played and at-bats. He is also second in hits, doubles, and walks. Early Life Matthew Martin Lee Carpenter was born in Galveston, Texas, on November 26, 1985. Rick and Tammie Carpenter are Carpenter's parents.

The older Carpenter played baseball in college and now works as a high school coach. When she was younger, his mother played softball. Before moving to Lawrence E. Elkins High School, Rick Carpenter taught and coached at La Marque High School for seven years with his family. Carpenter was on the first team of all-district for three years at Elkins High School and on the all-state tournament team twice.

Career Since his RS season made him old, he didn't have much negotiating power, so he settled for a $1,000 bonus. During his first year as a pro, he played for several A-level teams, such as the Batavia Muckdogs, the Quad Cities River Bandits, and the Palm Beach Cardinals. During the 2010 season, he was named a Topps Double-A All-Star, a Texas Mid-Season All-Star, and a Texas Post-Season All-Star. Carpenter also won the TCN/Scout.com Cardinals Minor League Player of the Year and Cardinals organisation Player of the Year awards for 2010. Carpenter started to get noticed after his performance in 2010. He was expected to compete for one of the last spots on the MLB Cardinals' roster at the next spring training.

Read the full article

0 notes

Text

70 Concert Production Jobs - National - Full Pay

Production Manager

Manager Production advances all event details for all shows. The Production Manager will be responsible for the production team and to set a plan in motion to execute the show as per the agreed terms in the contract. The Production Manager will adhere to a budget to ensure all costs are being tracked and monitored. They will ensure that all the needs of the show and performer are met.

Production - Event

West Palm Beach, FL

Full Time

https://www.aegworldwide.com/careers/jobs/AEGLV4453/production-manager?gh_jid=5615578002

Production Manager