#Chadi Abdel Salam

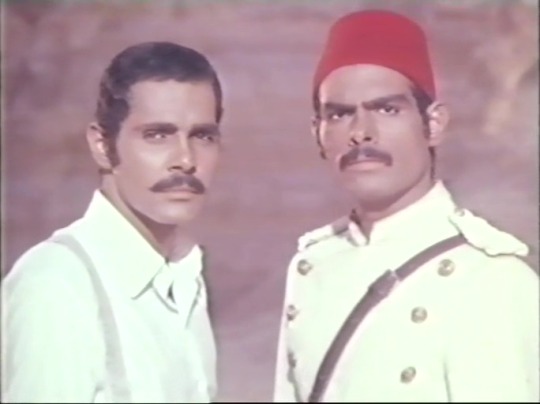

Photo

al-mummia / night of counting the years (eg, salam 69)

#al-mummia#night of counting the years#Chadi Abdel Salam#Ahmed Marei#Ahmad Hegazi#Nadia Lutfi#Abdel Aziz Fahmy

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Locarno70

Locarno is a dream territory for every cinephile. Not only does the festival have two key competitions revolving around the present and the future, the iconic leopard is always keeping a watchful eye on the past. Yet, the past in cinema is never passé but rather a treasure map, and so we will follow our new Canadian contributor Justine Smith as she reads this map for us...

In 1946, the inaugural Locarno Film Festival was launched at the Grand Hotel with a screening of Giacomo Gentilomo's film O SOLE MIO from that same year. Since its earliest days, Locarno has devoted itself to a risky and political cinema, preferring to highlight new filmmakers from new regions than to reaffirm the status quo. Part of that legacy has been the celebration of filmmakers of the past through their retrospectives, as they have highlighted lost, forgotten, and under-appreciated directors.

For the 2017 edition of the festival, also the 70th anniversary of Locarno, the festival focused its main retrospective programming on French filmmaker Jacques Tourneur curated by Roberto Turigliatto and Rinaldo Censi. As always, the festival similarly paid homage to notable figures in front of and behind the camera, including Jean-Marie Straub, Mathieu Kassovitz, Michel Merkt, and José Luis Alcaine. In celebration of the festival’s 70th year, the organizers also took the opportunity to look back at some of the highlights of the past seventy years – devoting the Histoire(s) du cinéma: Locarno70 sidebar to Locarno’s history of discovering new voices.

As one of Europe’s major film festivals, Locarno stands out by focusing its programming on emerging and political filmmakers. Beyond the grandeur of the Piazza Grande, where Hollywood films and crowd-pleasing auteurs wow audiences, the selection is systematically challenging and boundary-pushing. The way these retrospectives function within the wider confines of the festival’s identity is worth a closer examination. While the Tourneur line-up, which is rich and spans an often overlooked career, needs special attention, perhaps the most interesting retrospective of the 2017 edition of Locarno is the focus on the festival’s own history. Indeed, as one of the three oldest film festivals in Europe, Locarno occupies a unique space to reflect and redefine its signature identity. But how exactly do they do that?

Comprising of eleven films, this profile on the festival’s history crosses over five decades and spans four continents. The selection of just eleven titles, as a means of exploring and reflecting on 70 years seems like an astronomical task, and in doing so, the festival seeks to establish its legacy on its own terms. As Carlo Chatrian, the festival’s Artistic Director, explains in the programme notes, “Locarno has always been a place for breaking with the past or turning the present upside down.” The final selection of Histoire(s) du cinéma: Locarno70 films includes Marco Ferreri and Isidoro M. Ferry's THE LITTLE APARTMENT / EL PISITO (1958), Éric Rohmer's THE SIGN OF LEO / LE SIGNE DU LION (1962), Adolfas Mekas's HALLELUJAH THE HILLS (1963), Raúl Ruiz's THREE SAD TIGERS / TRES TRISTES TIGRES (1968), Chadi Abdel Salam's THE NIGHT OF COUNTING THE YEARS / AL-MOMIA (1969), Villi Hermann's SAN GOTTARDO (1977), Aleksandr Sokurov's THE LONELY VOICE OF MAN / ODINOKIY GOLOS CHELOVEKA (1987), Catherine Breillat's 36 FILLETTE (1988), Michael Haneke's THE SEVENTH CONTINENT / DER SIEBENTE KONTINENT (1989), Todd Haynes' POISON (1991), Alina Marazzi's FOR ONE MORE HOUR WITH YOU / UN'ORA SOLA TI VORREI (2002).

There is something almost teasing about this statement, which feels post-modern in its unfixed view of time and identity. The past and the present do not exist in a fixed reality but are malleable as they shift and change through new perspectives and experiences. This reflection on the past highlights integral moments from film history, like the French New Wave and the rise of American independent cinema. More importantly, though, this selection of films opens up a conversation between past and present, reflecting on the nature of time itself.

For example, in 1969, Raúl Ruiz’s TRES TRISTE TIGRE was in competition at Locarno and won the Pardo d'oro prize. This film was the filmmaker's first feature and examined the underground world of Chile during the 1960s. Groundbreaking during its release, in 1989 Caryn James reflected on this debut, as a retrospective of Ruiz’s work was mounted in New York City, saying, “the film's restless hand-held camera movement and its hemmed-in atmosphere of Santiago's small-time underworld seemed as fresh when it appeared in Latin America as the New Wave had in France a decade before.” Perhaps no title from Locarno70's retrospective has a more interesting conversation with the present, as it is the only film whose director took part in this year’s competition, with THE WANDERING SOAP OPERA / LA TELENOVELA ERRANTE (1990/2017). This should raise eyebrows of those who are aware that Ruiz died in 2011 – in fact, the film was shot all the way back in 1990. It is only recently that Ruiz’s long-time editor and wife, Valeria Sarmiento, assembled the film for its Locarno world premiere.

While it is not unusual that previously unfinished films are released posthumously at major festivals, it is almost unheard of that they should run in major competition, in particular for a festival that prides itself on the showcasing cinema of the future. This decision is iconoclastic and challenging to audiences, and likely the jury as well. While after all the film did not walk away with an award, it garnered well-earned praise. The feature, which is inspired by soap operas, tackles the Chilean identity right at the edge of a transitionary moment – just one year before Pinochet has been ousted from office. The film is broken up into seven days, seven different parts with their own contained narrative (even if some are more theme-driven). Among the best ones are those that poke fun at radical politics, such as one where two activists in a car are shot by two activists, who are shot by two activists, who are shot by two activists, etc. Though generally appealing, THE WANDERING SOAP OPERA would certainly attract a niche audience in that Chilean viewers will walk away with a greater understanding and appreciation of the film’s nuances and allusions that an average viewer with only a basic knowledge of Chilean politics and culture.

Among the other filmmakers who were featured in both the retrospective and this year’s programming is Todd Haynes. He returned to the festival with WONDERSTRUCK (2017), a film that has already earned mixed praises at other festivals, yet his first feature, POISON, was screened to an almost packed house at the newly revamped GranRex and presented by the filmmaker. Todd Haynes’ introduction of his full-length debut articulated how our relationships with films can be transformed by time. Made in 1991, POISON was a tryptic exploration of homosexuality at the height of the AIDS crisis. Inspired by the poetry of Jean Genet, the film examines through three different narratives about a sense of loss within the gay community in the face of violence and disease. The director's reflection on his own debut was centered as much on the experience of loss he now associates with the film, as with the production itself.

Before the screening, Haynes listed the many collaborators who died since the film’s production, including his long-time editor James Lyons. POISON is, in many ways, an angry film addressing the gay community’s culpability in violence against each other, as well as the disastrous implication of AIDS. That rage has not been dispelled in a rewatching of the film, if anything, is heightened by the sheer scope the AIDS crisis has had on young, gay men. Within the scope of a current political climate, where a renewed AIDS crisis has hit areas of the United States such as Indiana, the film has continued and horrified resonance in our modern-day.

Still, not all the Histoire(s) du cinéma picks had such overt connections from the past to the present. In fact, one film felt so out of time that it seems a small miracle it was even made at all. Restored several years ago, THE NIGHT OF COUNTING THE YEARS is considered the greatest Egyptian film of all time but is still rarely screened, so of the many discoveries of this year’s festival, this may be among the brightest. Set in 1881, the film reflects on the true incidents of an isolated Egyptian tribe who have relied for centuries on a cache of Pharaohic mummies to make their fortune. After the death of a family patriarch, members of the tribe become greedy, selling off more than they should, and drawing attention to the authorities.

THE NIGHT OF COUNTING THE YEARS examines the cost of identity, tackling the question of what it means to be Egyptian in the modern world. The film feels infused by the dusty desert air, the characters and their homes coated in the past, their past, that they are willing to sell off to the highest bidder. With bright infusions of color, such as fuchsia flower petals laid upon a gravesite, the film has a mythical atmosphere: one in which the living can return from the dead. Looking towards the past, the lack of canonical power of THE NIGHT OF COUNTING THE YEARS is a reflection on the westernized perspective of great art. Cinema of the Middle East and Africa is often relegated to a second-class status as the values and questions addressing cultures and people unlike the European powers, have been deemed, consciously or not, as less worthy. While the vast majority of Locarno’s retrospective on its history has maintained a Western point of view, the presence of THE NIGHT OF COUNTING THE YEARS justifies apprehensions and questions related to the cinematic canon, which privileges certain voices and points of view over others.

One of the greatest joys of a festival like Locarno is that it is a place not only for discovery but doubt. In my two experiences at the festival, debates over merit are quickly overturned in favor of debate over the politics of cinema. The retrospectives, in particular, can serve as an important measure for current dominant perspective on film history and how we conceive important and new cinema.

If you are a film industry professional, you can watch films from Locarno FF on Festival Scope.

#Locarno FF#Locarno70#Pardo d'oro#Jacques Tourneur#Jean-Marie Straub#Mathieu Kassovitz#Michel Merkt#José Luis Alcaine#Histoire(s) du cinéma#Marco Ferreri#Isidoro M. Ferry#Éric Rohmer#Adolfas Mekas#Raúl Ruiz#Chadi Abdel Salam#Villi Hermann#Aleksandr Sokurov#Catherine Breillat#Michael Haneke#Todd Haynes#Alina Marazzi#Chilean cinema#General Pinochet#American cinema#AIDS#Egyptian cinema#French New Wave#cinephilia#festival report#Justine Smith

1 note

·

View note

Photo

al-mummia - the night of counting the years (1969)

0 notes

Text

The Youssef Chahine Podcast No. 35: An Egyptian Perspective on Al-Momia/ The Night of Counting The Years

The Youssef Chahine Podcast No. 35: An Egyptian Perspective on Al-Momia/ The Night of Counting The Years

We return to chat some more about Chadi Abdel Salam’s great and beautiful Al-Momia/ The Night of Counting The Years at a most propitious time, since the day after our chat the mummified bodies of the kings were moved, with great ceremony, and for the first time, from where they were taken to rest at the end of the film to a new museum designed especially for them in Cairo. Central Cairo was…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

Japanese poster. The Night of Counting the Years (1969)

Directed by Chadi Abdel Salam

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

المومياء / Al-Mummia, شادي عبد السلام / Shadi Abdel Salam (1969)

#المومياء#al-mummia#شادي عبد السلام#shadi abdel salam#chadi abdel salam#1969#egypt#mummy#egyptian#1800s#Upper-Egyptian#mummies#tomb#kurna#antiquities#black#black market#DB320#Tomb DB32#tt320#tebas#theban necropolis#pinedjem#1881#deir al-bahari#horbat#clan#arabic#grave robbing#the night of counting the years

2 notes

·

View notes