#Chishū Ryū

Text

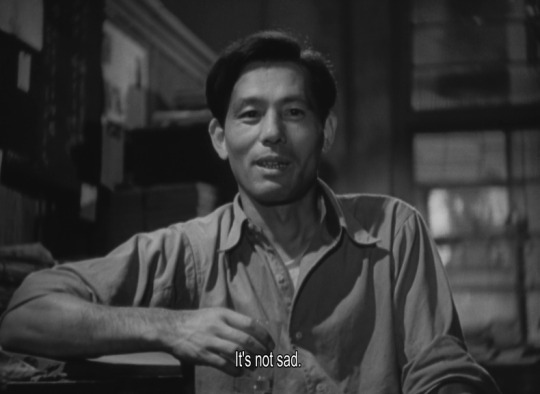

Yasujirō Ozu

- A Hen in the Wind

1948

#Yasujirō Ozu#Yasujiro Ozu#小津安二郎#A Hen in the Wind#風の中の牝鶏#Shuji Sano#佐野周二#Chishu Ryu#笠智衆#jazz#japanese film#1948#Chishū Ryū#Shūji Sano

179 notes

·

View notes

Text

An Autumn Afternoon (1962) | dir. Yasujirō Ozu

#an autumn afternoon#yasujirō ozu#chishū ryū#shima iwashita#keiji sada#mariko okada#films#movies#cinematography#screencaps#yasujiro ozu

159 notes

·

View notes

Text

SETSUKO HARA and CHISHŪ RYŪ in:

LATE SPRING (1949) dir. Yasujirō Ozu

TOKYO TWILIGHT (1957) dir. Yasujirō Ozu

#late spring#tokyo twilight#yasujirō ozu#worldcinemaedit#classicfilmcentral#classicfilmsource#cinemaspast#filmauteur#setsuko hara#chishū ryū#yasujiro ozu#chishu ryu#late spring 1949#filmgifs#shgif#ozugifs#parallellis#ellisgifs#ozu parallels#fofm#japanese movie#ozu was foul for this. im lying facedown on the floor#fissues#queue

157 notes

·

View notes

Text

#movies#polls#tokyo story#50s movies#yasujiro ozu#yasujirō ozu#chishū ryū#chishu ryu#have you seen this movie poll

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Until the End of The World [Bis ans Ende der Welt] (1991)

Director - Wim Wenders, Cinematography - Robby Müller

"The present will look after itself, but it's our duty to realize the future with our imagination."

#scenesandscreens#Until the End of the World#wim wenders#robby müller#solveig dommartin#Chick Ortega#jeanne moreau#Jimmy Little#max von sydow#Chishū Ryū#allen garfield#lois chiles#David Gulpilil#Elena Smirnova#Kuniko Miyake#Ernie Dingo#sam neill#rüdiger vogler#Eddy Mitchell#william hurt#Adelle Lutz#Bis ans Ende der Welt

23 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Chishū Ryū & Kinuyo Tanaka in "Ornamental Hairpin" (1941) dir. Hiroshi Shimizu

#chishū ryū#kinuyo tanaka#笠智衆#田中絹代#film#cinema#japanese film#movie#movie stills#film frames#cinematography

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

vimeo

Las canciones de Higanbana

彼岸花 (Higanbana) [Yasujiro Ozu, 1958]

#Cine japonés#Japanese Cinema#Shin Saburi#Ryūji Kita#Nobuo Nakamura#Toyo Takahashi#Chishū Ryū#Canciones en el cine#Cinema Songs#Japanese songs#Canciones japonesas

0 notes

Text

#Le Goût du saké#Après-midi d'automne#秋刀魚の味#An Autumn Afternoon#Sanma no aji#Yasujirō Ozu#Chishū Ryū#Shima Iwashita#Keiji Sada#1962

1 note

·

View note

Text

“Early Summer is about the difference between the married and the unmarried, how the married try to persuade or (worse) coerce the unmarried into getting married, and how maybe that isn’t always such a good idea. This theme is explicitly called out more than once in the film.

Early Summer further implies that there may be a good reason why some unmarried people, including Noriko (but not just Noriko), don't want to marry: they may be “that type of person,” as the young lesbian Fumi described herself in Takako Shimura's manga Aoi hana. This subtext rises briefly to the level of text at least once before being ambiguously dismissed.

Both Ozu and Hara remained unmarried until their deaths, and to my knowledge neither were ever credibly reported as having a romantic relationship with anyone. Per Donald Richie’s commentary on the Criterion release (referenced in the next post), Ozu was reported to become angry at any talk of his marrying. Meanwhile Hara, though termed “the eternal virgin” by a film producer for her film image, in real life had close friendships with many women, including a hair and makeup artist whose friendship with Hara began early on and continued after Hara retired into obscurity at the height of her career.

In modern terms we could therefore hypothesize Early Summer as a queer film subtly but firmly protesting compulsory heterosexuality, made by a (possibly) queer director and starring a (possibly) queer actor.

…

Early Summer opens with three establishing shots: first a shot of a dog walking freely on the beach with the ocean in the background, then a shot of a single bird in a cage outside, and then a final shot of birds in cages inside a house. This is the house in the oceanside town of Kamakura in which Noriko (Setsuko Hara’s character) lives, along with her brother Kōichi (Chishū Ryū), his wife Fumiko (Kuniko Miyake), Noriko and Koichi’s father (Ichiro Sugai) and mother (Chieko Higashiyama), and Kōichi and Fumiko’s two young boys.

If we wish, we can interpret the first and third shots as showing a strong contrast between freedom in nature on the one hand, and the restrictions imposed by society and the Japanese family system on the other. In this interpretation the second shot represents Noriko, who has a degree of independence that her mother and Fumiko do not have, but is still constrained by the bonds of family and society.

In the following scenes Kōichi takes an early train to his job as a physician, while Noriko goes to the Kita-Kamakura station to catch a later one. There she meets Kenkichi, another physician who works with Kōichi and who (along with his mother) is the family’s next-door neighbor. Kenkichi tells her that he’s been reading a book, implied to have been recommended by Noriko. The Criterion release describes it only as “this book,” but the BFI release names it as Les Thibaults.

Les Thibaults (published in Japanese as Chibō-ka no hitobito, and apparently relatively popular in Japan at the time) is a multi-volume French novel that begins as one of its protagonists is discovered writing passionate messages to a fellow schoolboy — something Ozu himself was apparently falsely accused of — and is then separated from his friend. Later volumes describe their diverging paths in life. Why might have Noriko recommended this particular novel to Kenkichi? Hold that thought.

We then see Noriko at work, as a secretary and executive assistant to the head of a small firm (Shūji Sano). As she talks with her boss regarding café recommendations, her best friend Aya (Chikage Awashima) arrives, there to collect payment for the boss’s spending at the restaurant her mother owns. Noriko’s boss wonders when they’ll both get married, and refers to them as “old maids.”

(Before becoming a movie actress, Chikage Awashima was a musumeyaku top star in the Takarazuka Revue and occasionally played “pants roles,” i.e., as a female character dressing as a man for plot reasons. Osamu Tezuka was a fan of hers, and she supposedly inspired the main character Sapphire, “born ... with a blue heart of a boy and a pink heart of a girl,” in his manga Princess Knight. Why might this be relevant to Early Summer? Again, hold that thought.)

After work, Noriko meets Kōichi and Fumiko for dinner. While they eat, Kōichi complains about post-war women (“[They’ve] become so forward.”) and Noriko corrects him: “We've just taken our natural place.” Kōichi then claims that’s why Noriko can’t get married, and she rebukes him: “It’s not that I can’t. I could in a minute if I wanted to.” (Note: a bit of foreshadowing here.)

Next occur the two key events that set the main plot in motion. First, Noriko’s great-uncle (Seiji Miyaguchi) arrives for a visit. He wonders why she isn't married yet. “Some women don't want to get married,” he tells her. “Are you one of them?” Noriko laughs and leaves the room, but the seed has been planted in the minds of her family.

Noriko’s boss also thinks it's time for her to get married, and he has just the man for her: “He’s never been married. Not sure if he's still a virgin.” Her boss has photographs to show her, and won’t leave her leave without taking them.

Meanwhile Noriko and Aya mercilessly tease one of their married friends, and after attending another friend’s wedding have dinner with that friend and another married friend, with a side dish of sexual innuendo. One of the married friends brags about how she spent a rained-out honeymoon playing with a “spinning top”: “My husband is very good at it.” Her friend cautions her: “You shouldn't flaunt it in front of the single girls.”

However, Aya is not impressed with the implied amazingness of heterosexual intercourse: “Silly! We don’t play with tops, do we?” Noriko enthusiastically agrees with her: “That’s for children, isn’t it?” The debate between the married and the unmarried continues, after which Noriko goes home, where Kōichi and Fumiko are scheming regarding the marital candidate proposed by Noriko’s boss.

Kenkichi’s mother then visits Noriko’s mother, and tells her that a man from a detective agency has been asking about Noriko: “I realized it was about her marriage.” We also learn that Kenkichi’s wife died two years ago (leaving him with a young daughter), and that he's not interested in remarrying: “All he does since his wife died is read books” (like Les Thibaults). Finally, we learn that Kenkichi’s best friend, Noriko’s brother Shoji, went missing in the war.

We now come to the climax of the first half of the movie. As Noriko’s nephews and their friends play with their model train set downstairs (one nephew asking if their father will buy them more train track), Aya visits Noriko and they talk in her room upstairs. Their married friends have made various excuses for why they couldn’t also visit; Noriko recalls how close they were at school and laments their drifting apart.

Throughout the first half of Early Summer Noriko and Aya are shown as mirroring each other’s gestures and speech. That mirroring continues in this scene (for example, they sit down next to each other at the exact same time and in the exact same manner), and then a very interesting thing happens. Ozu’s typical modus operandi is to continue a shot until someone stops speaking or moving, or even until they leave the room. But here he cuts immediately from Noriko and Aya simultaneously raising their glasses to drink, to Noriko’s father and mother simultaneously bringing food to their lips, as they relax sitting on a street curb in town.

If I were to speculate about what this juxtaposition might mean, if anything, I’d speculate as follows: that Ozu intended to show that, whatever Aya and Noriko might be to each other, they are as close, secure, and happy in their relationship as Noriko’s mother and father are in theirs — as much a couple as any other in the film, but not formally recognized as such.

Noriko’s father tells his wife, “This may be the happiest time for our family,” although he’s sad at the thought of Noriko leaving. They continue their conversation, and then are interrupted by the site of a balloon rising into the sky. “Some child must be crying,” Noriko’s father remarks. “Remember how Kōichi cried when he lost his balloon?”

…

The good times continue as Noriko brings home a cake to eat with her sister-in-law Fumiko, and their neighbor Kenkichi drops in unexpectedly and is invited to share it with them. The scene re-introduces Kenkichi and brings up the subject of his remarrying — something he doesn’t want, but his mother (played by Haruko Sugimura) does.

…

In the meantime Noriko’s brother Kōichi has been pursuing the idea of a marriage between Noriko and an unseen bachelor first suggested by Noriko’s boss, including asking his friends and associates for more information on the proposed groom. The results are “very promising”: “He’s in the social register, and seems to be a fine businessman.” “How nice,” replies his mother, but, “how old is he?”

…

Then Noriko’s boss asks a few questions that we’ve been asking ourselves. While Noriko is away from work, Aya stops by, and the boss questions Aya on whether Noriko will go through with the match or not: “I don't understand her ... Is she interested in men?” Aya at first demurs: “What do you think?” Noriko’s boss has seen indications both ways, and presses the question: “Has she always been like that?” Aya responds in the affirmative. The questioning goes on. Aya tells him that Noriko’s apparently never been in love, “but she has an album of ... Hepburn photos this thick,” holding her thumb and forefinger about 4 centimeters apart.

Here we have the first of two translation issues. Aya actually refers to “Hepburn” without mentioning a given name. The Criterion subtitles — by Donald Richie, who should have known better — make this a reference to Audrey Hepburn, who’d had only small roles by then. It’s almost certain that this is instead a reference to Katherine Hepburn, who was a major star by the time Noriko would have entered middle school. Was the teenaged Noriko besotted by the androgynous beauty of Katharine Hepburn (who would have made a stunning otokoyaku)? It sure looks like it.

The subtext now threatens to become text, as Noriko’s boss learns that “Hepburn” refers to an American actress, and asks the obvious follow-up question about Noriko. In the Criterion subtitles it’s translated as “So she goes for women?” The BFI translation puts it more bluntly: “Is she queer?” What is Noriko’s boss really asking? Japanese speakers can correct me here, but I believe his actual question uses the term “hentai.”

Western fans are used to thinking of “hentai” as referring to pornography. However, my understanding is that at the time of the film “hentai” in colloquial Japanese would have referred specifically to sexual behavior that was considered abnormal. So if Noriko’s boss did use the term, another possible translation might have been “Is she a pervert?” Both the Criterion and BFI translations soften the question; in particular BFI’s “is she queer?”, while defensible, risks projecting our current ideas about “queer” (including its positive connotations) onto a film created in a different time.

In any case, Aya is determined to shut down any discussion of Noriko’s proclivities. “No!” she firmly replies. Noriko’s boss is apparently unconvinced: “You can never know. She’s very strange, in any case.” His prurient instincts aroused, Noriko’s boss then envisions another solution to the problem of Noriko, and queries Aya about it: “Why don’t you teach her?” “About what?” “Everything.” “What do you mean, everything?” He pats her shoulder and admonishes her: “Don’t try to be coy,” as we viewers pause to consider the implications of what he’s asking her to do.

Aya rejects this line of inquiry as well: “Don’t talk to me like that! That was rude!” Noriko's boss laughs, offers a half-hearted apology, and then (after telling Aya that Noriko won’t be back that day) invites her to lunch and quizzes her on her preferences in sushi: “Tuna” she says. He continues, “How about an open clam?” (which Donald Richie's commentary helpfully informs us is a euphemism for the vagina). “Sure,” she replies. “And a nice long rice roll?” “No, thank you!” His final words are, “You’re strange too,” and again I think I hear the word “hentai” enter the conversation.

…

Recall that Kenkichi decided to accept an offer as a department head in a hospital in Akita, several hundred kilometers north of Tokyo and on the opposite coast. Noriko meets him in a café before her brother Kōichi is to host him at a farewell dinner party, and they talk about Shoji, Noriko’s other brother who went missing in action during the war. Kenkichi recalls how he and Shoji were best friends in school, often eating at this very café, indeed at this very table. Kenkichi tells Noriko that he still keeps a letter that Shoji sent him, with a stalk of wheat enclosed (probably indicating that Shoji was deployed in northern China). Noriko asks if she can have the letter, and Kenkichi agrees.

Afterward Noriko visits Kenkichi’s mother, while Kenkichi himself is still at his farewell party. Kenkichi's mother tells Noriko her secret dream (“please don’t tell Kenkichi”): “I just wish Kenkichi had gotten remarried to someone like you.” She apologizes and asks Noriko not to be angry (“It’s just a wish in my heart”), but Noriko stares at her with an intense expression (her usual smile absent), and asks her, “Do you mean it? ... Do you really feel that way about me?” Kenkichi’s mother apologizes again, but Noriko presses on: “You wouldn’t mind an old maid like me?” Then before Kenkichi’s mother can respond, Noriko speaks: “Then I accept.”

Kenkichi’s mother is incredulous. She asks Noriko several times to confirm what she’s saying, thanks Noriko effusively and weeps tears of joy at her good fortune, but continues to question Noriko about her decision even as Noriko leaves to go home. (Incidentally, this scene features a bravura performance by Haruko Sugimura.)

After she leaves the house, Noriko encounters Kenkichi, just returned from his farewell party. Noriko exchanges some small talk with him, but says absolutely nothing about what she just told his mother.

Noriko's decision then plays out across multiple scenes:

At first Kenkichi doesn’t understand what his mother is trying to tell him (“She accepted.” “Accepted what?”). When he finally gets the message (“She agreed to marry you. To become your wife!” “My wife?” “Yes. Isn’t it wonderful?”), he looks absolutely gobsmacked. His mother breaks down in tears again telling him how happy she is, and how happy he should be. He tries to play along (glumly echoing, “Yes, I’m happy”), but he looks for all the world like a man who would sooner eat nails than enter into another marriage.

Kenkichi’s mother doesn't understand why he’s not happy. She concludes, “What an odd boy you are.” The Japanese word here appears to be “hen,” which I understand to be a softer adjective than “hentai,” and not sexual in nature. But note that Kenkichi is now the third person after Noriko and Aya to be referred to as not normal in some way.

Meanwhile Noriko is interrogated about her decision by her family, especially by Kōichi, in a beautifully framed and shot scene — Noriko in white, her head bowed, her brother in black, barking questions like a prosecutor cross-examining a criminal. Noriko is unrepentant: “When his mother talked to me, I didn’t feel a moment’s hesitation. I suddenly felt I’d be happy with him.” Her parents retire upstairs to chew on their disappointment — Noriko walking silently past them on her way to her room — while Kōichi tells Fumiko, “What could we do now? She’s made up her mind. You know how she is.”

…

Meanwhile Noriko and Aya have their last scene together. It starts by echoing and completing the action at the end of their previous scene: then they raised their glasses together to drink, now they lower their glasses in a simultaneous gesture. Aya tells Noriko that she can’t believe Noriko would ever end up like this: she thought Noriko would be a modern woman living “Western-style, with a flower garden, listening to Chopin,” “wearing a white sweater, with a terrier in tow,” and greeting Aya in English — “Hello, how are you?”

Instead Aya now imagines Noriko wearing farmers clothes in rural Japan, speaking the local dialect. She playfully imitates country speech, and Noriko responds in kind: “Ya don’t look it, but ya talk like the locals.” “I figure to live in Akita when me and my man get hitched.” The subtext here I read as follows: Noriko knows how to pretend to be something she is not — a conventional heterosexual woman in a conventional heterosexual marriage — and she will accept doing so in her self-imposed exile from Tokyo, the price she must pay for avoiding what she considered to be a worse fate.

The tone then turns serious. Aya recalls meeting Kenkichi when they were in school, on a hiking trip with Noriko and her brother Shoji, and presses Noriko about her choice: “Did you already love him then?” “No, I had no particular feeling for him. ... I never imagined myself marrying him.” Noriko evades Aya’s questions about how she came to love Kenkichi, refusing time after time to acknowledge her feelings for him as those of love. Instead she insists, “No, I just feel I could trust him with all my heart and be happy.”

But trust Kenkichi for what? we want to ask Noriko. To respect her for who and what she is? To not want a conventional relationship with her? To not press her for sex or for children (after all, he already has one)? To keep her secrets, as she might keep any secret of his?

…

The family then gathers for one last commemorative photo. Without Noriko's salary they can no longer afford the house in Kamakura, so they break up: the parents to live with the great-uncle; Noriko to Akita with Kenkichi, his mother, and his daughter; and Kōichi, Fumiko, and their sons to some other less-expensive dwelling (perhaps an apartment in the Tokyo suburbs).

The parents recall when they moved into the house: “It was spring and Noriko had just turned 12.” Kōichi remembers that time as well: "She used to wear a ribbon in her hair, and she was always singing." But “children grow up so quickly,” her parents remark, and living together forever, "that's impossible."

Her usual smile nowhere in evidence, Noriko takes it all upon herself: “I’m sorry, I’ve broken up the family.” Despite reassurances from her father (“It’s not your fault. It was inevitable.”) she flees from the room, goes upstairs to her own room, and cries her heart out, distraught about the turn that her and their lives have taken.

The final scene shows Noriko’s parents at the great-uncle’s house, far from the sea. They glance at a wedding procession walking through the fields (“Look there. A bride is passing by. I wonder what sort of family she’s marrying into?”), think of Noriko, and resign themselves to the family's fate: “We shouldn’t ask for too much.” “We've been really happy.”

— Frank Hecker, “Ozu’s Early Summer Seems Pretty Darn Queer to Me”

#yasujiro ozu#ozu#queer history#setsuko hara#early summer#film criticism#queer film#gay subtext#queer coding#long post

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

An Autumn Afternoon (1962) | dir. Yasujirō Ozu

#an autumn afternoon#yasujirō ozu#chishū ryū#shima iwashita#keiji sada#mariko okada#films#movies#cinematography#screencaps#yasujiro ozu

184 notes

·

View notes

Text

—tokyo story (1953) dir. yasujirō ozu

#tokyo story#yasujiro ozu#tokyo monogatari#setsuko hara#chishu ryu#filmgifs#setsukoharaedit#japanese movie#yasujirō ozu#chishū ryū#ozuedit#ozugifs#shgif#ellisgifs#going insane about the parallel between this (their first conversation) and their last conversation in the whole film#her days are so empty of meaning and substance and purpose#but that emptiness is so time consuming#queue

51 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Movies I watched this Week #123 (Year 3/Week 19):

When thinking of Ozu, what’s the first thing that comes to mind? Refined domestic dramas, tatami shots, chrysanthemums flowers - or fart jokes? ... Good morning, my 5th film by Yasujirō Ozu, is apparently one of the few films he directed that is not about old people but about children.

A gentle and delightful comedy about two boys who refuse to speak until their parents buy a television set, it is full with ‘Pull my finger’ (rather ‘Touch on my forehead’) moments. With Ozu's favourite actor Chishū Ryū. 8/10.

🍿

Let him go, a wonderful discovery by a Thomas Bezucha, a director previously-unknown (to me). A moving, and slow-moving, neo-Western that turns 180 degrees for the third act. Salt of the earth, retired sheriff Kevin Kostner and taciturn wife Diane Lane grieve after the death of their son, then try to rescue their only grandson from some unsavory hillbillies. A tense story about loss. 8/10.

There are some magnetic and gorgeous actresses I am completely attracted to. Beside Diane Lane, there are Léa Seydoux, Maggie Cheung, Catherine Deneuve, Charlize Theron, Sidse Babett Knudsen, Isabelle Huppert, Anna Kendrick, La Binoche, Etc.

So I’m going next to watch Lane’s two 1983 back-to-back Coppola films, ‘The Outsiders’ and ‘Rumble fish’.

🍿

First watch: The ruthless, brutal City of God, a Brazilian ‘Goodfellas’, but worst, not as funny, and so much bloodier and grittier. I was reluctant to watch it for a long time and for a good reason. Merciless crimes in the favelas, cruel, senseless killings committed by children, the poorest of the poor, and based on a true story.

🍿

Lianna, my first relationship drama by independent director John Sayles, picked randomly from a list. An honest exposition about a vulnerable woman [who’s married to a prick named ‘Dick’!] and a mother of two who suddenly realizes that she’s a lesbian. She comes out, sans heroism, and faces the difficult and lonely struggles of being herself. Hard to imagine that it was written (so well) by a man, and in 1983.

🍿

‘Meet me at the top of the Empire State Building in 3 months’ X 3:

🍿 Re-watch: Warren Beatty and Annette Bening’s Love Affair is broadly panned as one of the worst remakes ever made, but for me it’s one of my favorite romances. I love everything about it, from Ennio Morricone’s theme (which did tend to repeat itself again and again, but was glorious) to the sappy chemistry between the two lovers, and to this being Katharine Hepburn’s final role. 9/10.

🍿 It was based on Leo McCarey’s 1939 original Love Affair with Charles Boyer and Irene Dunne. But I found it a stiff and slow tearjerker in spite of its pedigree - "If you can paint, I can walk".

🍿 Leo McCarey’s own remake, the 1957 An Affair to remember, with Cary Grant and Deborah Kerr was better (because it was newer?). Still I prefer the later Beatty-Bening version.

🍿

The Novelist’s Film, my 10th art film by the always-the-same Korean naval-gazer Hong Sang-soo. Two women, one a prolific writer who all of a sudden can’t find the energy to write, and the other pretty actress Kim Min-hee who doesn’t want to work any more, meet randomly during a walk in the park, and on the spot decide to make a film together. As usual in his movies, the whole concept is but a series of mundane conversations, usually over coffee and drinks (this time over Makgeolli rice wine) which eventually adds up to a small and subtle epiphany. 7/10.

🍿

Sapphire, my third by forgotten British director Basil Dearden. While it’s not as compelling as the first two groundbreaking films of his that I saw (‘Victim’ and ‘All night long’), this murder mystery again dealt with a social problem of the day, one not usually explored on film. This time it was bigotry and racial discrimination, and it did so openly and honestly.

How is Dearden not better appreciated today?

🍿

Dogtooth, my third uncomfortable art film by Yorgos Lanthimos (after ‘The killing of a sacred deer’ and ‘The lobster’). A weird, freaky and perverse metaphor for fascism, or at least for the cult of the patriarchy. A Fritzl-like story about a father who isolates his three adult children in the family compound and keeps them home-schooled and emotionally stunted. Unpleasant and joyless.

🍿

“I've known you for all of two mins & already I don't like you...”

Midnight Run, my 3rd re-watch in 3 years (and possibly my 20th re-watch in 20 years...), one of my all-time favorite movies, a perfect comedy-action buddy-cop with a heart. Best roles for (newly father of 7) Robert de Nero, as well as for FBI Special Agent Alonzo Mosely, Dennis Farina, Joe Pantoliano, and a fantastic Danny Elfman score. 10/10 again (and again).

Strangely enough, this brilliant script and impeccable dialogue were written by one prolific George Gallo, who also wrote 27 other scripts and directed 21 movies none of which I ever heard of. And most all his other movies have between ZERO to 30 ‘Rotten Tomato Scores’!

(Photo Above).

🍿

William Wyler’s 1966 How to Steal a Million. The idea of seeing Audrey Hepburn and Peter O'Toole [whose names, both first and last, are euphemisms for 'Cock'] in a light romantic comedy is irresistible. But the movie itself was a big letdown: All style and no substance. 2/10.

🍿

2 counties:

🍿 "Here I was for the first time in my life having a nice peaceful time and you had to come and spoil it".

County hospital, a 1932 Laurel and Hardy 2-reeler, simple and not too slapsticky. What a strange relationship these two “friends” had...

🍿 I used to lived in Anaheim Hills & Yorba Linda, CA when the third-rate teen ‘comedy’ Orange County premiered, but I only tried to see it now for the first time. Sadly, I couldn't stand this superficial and Clichéd low-brow piece of nepotism, just like (many of) the people who used to live there, and I had to click it off after 15 torturous minutes. 1/10

🍿

I got talked into watching Saul Goodman’s violent action flick Nobody again. It’s still generic and unoriginal, and I hope they never do a sequel. 4/10.

🍿

Moviewise is a YouTube channel offering interesting film essays by a guy with a deep voice and a strange accent who often gives reactionary /masculine analyses. Last week I saw his ‘The camera and the mirror, a love story’. Here are some that I saw this week:

Why ‘The Banshees of Inisherin’ has no ending *

How to Immediately Identify a Great Director *

What is the Encyclopedic Film genre *

Why ‘All about Eve’ is a perfect screenplay *

Why ‘Jeanne Dielman 23, Quai du Commerce’ is boring and does not deserve to be called ‘World’s Best film’ *

How are “Puzzle film” different from surreal ones *

Breaking down film dialogue into the ‘Practical’ and the ‘Analytical’ *

Why Succession’s Logan Roy Always Wins *

But he’s also funny sometimes, as he is in A Guide for Analyzing Movies.

Many more inside. In spite of his endocentric chauvinism, his readings are still worth the watch.

And talking of Succession, I’m looking forward to bingeing on Season 4 at the end of May, when it’s all done.

🍿

3 shorts:

🍿 Of course I know about them, but I never actually seen any ‘Star Wars’ or JRR Tolkien movies. Caleb Ward used Midjourney AI tools to create two fictional trailers for alternative films directed by Wes Anderson, one for Star Wars, and another for Lord of the Rings: Cute.

🍿 In the end, what it felt like to almost die. A woman tells the story what she experienced when she had a massive pulmonary embolism.

🍿

(My complete movie list is here)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Oh. Mystery solved. At some point Bern and Lambda watched the Noriko Trilogy together and their takeaway was that marriage is for people similar to the late Ryū Chishū and absolutely no one else.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Traditions in transition: cinematic perspectives on the modernization of post-war societies (¼)

The following article is the first in a four-part series looking at how cinema depicts post-war societies’ transformations, and more precisely the transition from a traditional society to a modern one. In order to examine our topic from all angles, every installment of this series will be dedicated to a separate movie, each originating from a different country. Since context is essential to better understand what lies beneath images, and thus propose an in-depth analysis, I will always start by introducing the director and the significant historical events surrounding the films’ releases.

In this inaugural piece, we deal with Yasujirō Ozu’s An Autumn Afternoon (1962) portrayal of westernization and women’s emancipation amidst the Japan societal shifts of the 1960s. Through this work, I wish to highlight the multifaceted societal changes that come with post-war modernization, be it urban and rural spaces experiencing deep transformations due to industrialization, or the evolution of social norms and behaviors.

Part 1. An Autumn Afternoon (秋刀魚の味 The taste of Sanma, Yasujirō Ozu, 1962): westernization of Japanese everyday life and Women’s emancipation

youtube

An Autumn Afternoon's Original Trailer

Japan was propelled into the modern era because of the “Meiji Restoration”, a political event that took place in 1868 and brought about notable changes in the pre-modern feudal society. Commodore Matthew Perry’s visit in 1853 had a part to play in these transformations by leading the Japanese government to realize their “late-developing” status, thus causing the demise of the long-reigning Tokugawa shogunate and the disintegration of a status-ordered system. Accordingly, the “Meiji Restoration” saw the development of small-scale industries, an explosive growth of urban populations, the rise of commerce and the dissemination of education. Despite adopting Western models in areas like law, economy, politics, science and technology, Japan kept its customs and traditions alive. However, upon the completion of its industrial revolution in 1910, Japanese society went through a stagnating period. In fact, economic and social restructuring, which had become crucial, was still not fully achieved.

35 years later, the Axis defeat led to Japan’s occupation by the Allied Forces. Until the Peace Treaty was concluded in September 1951, The S.C.A.P (Supreme Commander for Allied Powers) imposed several reforms, including the adoption of a new constitution in May of 1947. The principle of popular sovereignty was established, and the patriarchy family system abolished. The focus was now on economic reconstruction.

Please CHECK the following article for further historical information

By the 1960s, Japan had emerged from the devastation of World War II and embarked on a path of economic growth, technological advancements and international integration. This era, known as the “economic miracle”, witnessed significant generational shifts. All of which deeply influenced Yasujirō Ozu’s filmography. Especially as the filmmaker was born in 1903 into a middle-class family and has lived through a good part of these dramatic changes.

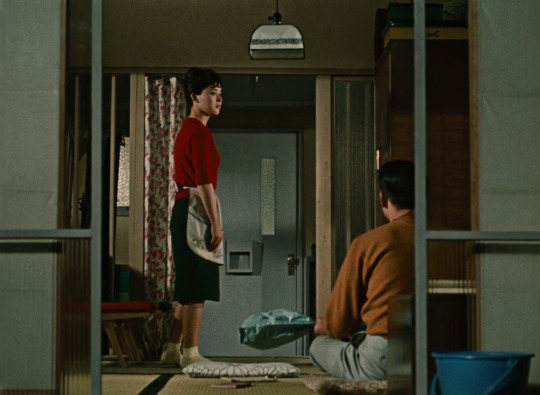

Set in post-war Japan, An Autumn Afternoon stars Ozu’s regular Chishū Ryū as Shūhei Hirayama, a middle-aged widower and executive at a factory. Hirayama lives with his grown daughter, Michiko (Shima Iwashita), and younger son, Kazuo (Shinichirō Mikami). His elder son, Kōichi (Keiji Sada) has moved out to live with his wife, Akiko (Mariko Okada), leaving Shūhei to be looked after by Michiko. As was the custom in Japan, in the event of the mother’s death, the daughter looks after the family and the household until she eventually marries. At the same time, women are expected to take on domestic roles and marry at a young age, because “older never marry”. As the story unfolds, Shūhei Hirayama’s colleagues and friends begin to express their concern about Michiko’s unmarried status and urge him to find her a suitable husband. Feeling the weight of societal expectations and his own sense of duty, he resigns himself to arrange a marriage for his daughter and encourage her departure from their home. Although the emphasis on this theme may seem, at first, antiquated and patriarchal, women's desire for emancipation is very much present in the atmosphere. Michiko and Akiko, while accepting the traditional roles that society had accorded them, often express their disapproval of certain male behaviors, by refusing to serve them as expected or by questioning their decisions. Both are not afraid to make their voices heard.

Equinox Flower, Yasujirō Ozu, 1958

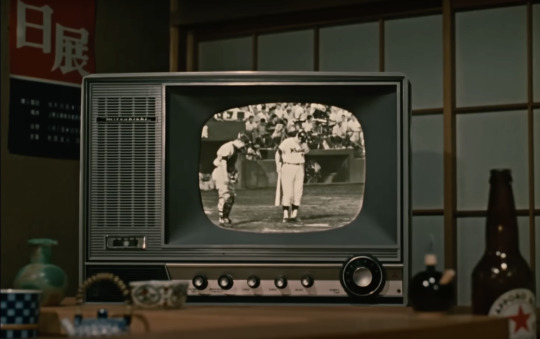

Notwithstanding the progress in the early 1960s, Japan remained dependent on Western technology imports for a long time, which were really expensive. This period also sees the transition towards television as a dominant medium of communication and entertainment. Due to this Western mass media exposure (movies, commercials, sport events, etc.), younger generations were greatly influenced by Hollywood and American popular culture. Equinox Flower, directed in 1958 already depicted urban dwellers, soda lovers.

An Autumn Afternoon, Yasujirō Ozu, 1962

In one of the most memorable scenes of An Autumn Afternoon, Shūhei Hirayama and his friends are seated on the floor, around a low table, as was the custom in traditional Japanese restaurants and households. The scene is filmed in Ozu’s regular static low-angle shots, commonly called “tatami” shots. On the opposite side of the restaurant, other clients are having dinner while watching a televised baseball match. Everyone sits around the same Western-style table, but there's no exchange. This juxtaposition beautifully encapsulates the fading traditions and Western growing influence in post-war Japanese society. The setting serves as a microcosm of the societal shifts portrayed throughout the film.

An Autumn Afternoon's opening sequence, Yasujirō Ozu, 1962

I can't conclude this first article without mentioning Ozu’s use of factory shots in the opening sequence. Also known as “pillow shots”, they are devoid of human presence and serve no narrative purpose other than marking time passing and transitions. In this case, they are a nod to the deep spatial transformations caused by industrialization. Factories and industrial areas are very much present in Ozu’s cinema, and are more often than not used as “pillow shots” or a backdrop, as in The Only Son (1936).

The Only Son, Yasujirō Ozu, 1936

An Autumn Afternoon is Ozu’s last movie before his death in December 1963. The original title of this film means “The taste of Sanma”, where Sanma is a mackerel pike. While never translated correctly, it carries a sense of nostalgia for a vanishing world, its customs and traditions. Like a Proust madeleine, “The taste of Sanma” dredges up a long-lost memory, reflecting on the complexities of post-war Japanese society.

Thank you for joining me on this journey. I genuinely appreciate your interest and support. Please stay tuned so you don't miss my upcoming article. Next time, We’ll be leaving for 1950s Norway through Kitchen Stories (2003). We’ll studying how social and environmental impacts of the Norwegian post-war industrial boom are depicted by movie director Bent Hamer.

Ruth Sarfati

0 notes

Photo

Tokyo Story (1953) dir. Yasujirō Ozu

#tokyo story#東京物語#tōkyō monogatari#yasujirō ozu#chishū ryū#chieko higashiyama#japanese movies#japanese films#japanese cinema#1950s movies#1950s films#50s movies#50s films#tokyo story 1953#cinephile#cinematography

74 notes

·

View notes