#Clayborne Carson

Text

I was the only Negro passenger on the plane, and I followed everybody else going into the Dobbs House to get lunch. When I got there one of the waiters ushered me back and I thought they were giving me a very nice comfortable seat with everybody else and I discovered they were leading me to a compartment in the back. And this compartment was around you, you were completely closed in, cut off from everybody else, so I immediately said that I couldn’t afford to eat there. I went on back and took a seat out in the main dining room with everybody else and I waited there, and nobody served me. I waited a long time, everybody else was being served. So finally I asked for the manager and he came out and started talking, and I told him the situation and he talked in very sympathetic terms. And I never will forget what he said to me.

He said, “Now Reverend, this is the law; this is the state law and the city ordinance and we have to do it. We can’t serve you out here but now everything is the same. Everything is equal back there; you will get the same food; you will be served out of the same dishes and everything else; you will get the same service as everybody out here.”

And I looked at him and started wondering if he really believed that. And I started talking with him. I said, “I don’t see how I can get the same service. Number one, I confront aesthetic inequality. I can’t see all these beautiful pictures that you have around the walls here. We don’t have them back there. But not only that, I just don’t like sitting back there and it does something to me. It makes me almost angry. I know that I shouldn’t get angry. I know that I shouldn’t become bitter, but when you put me back there something happens to my soul, so that I confront inequality in the sense that I have a greater potential for the accumulation of bitterness because you put me back there. And then not only that, I met a young man from Mobile who was my seat mate, a white fellow from Mobile, Alabama, and we were discussing some very interesting things. And when we got in the dining room, if we followed what you’re saying, we would have to be separated. And this means that I can’t communicate with this young man. I am completely cut off from communication. So I confront inequality on three levels: I confront aesthetic inequality; I confront inequality in the sense of a greater potential for the accumulation of bitterness; and I confront inequality in the sense that I can’t communicate with the person who was my seat mate.”

And I came to see what the Supreme Court meant when they came out saying that separate facilities are inherently unequal. There is no such thing as separate but equal.

The Autobiography of Martin Luther King Jr.

#MLK#Martin Luther King Jr#Clayborne Carson#The Autobiography of Martin Luther King Jr#1960s#civil rights#civil rights movement#black history#black history month#black lives matter#black history matters#black authors#history#blm#black voices#bipoc#african american#peaceful protests#nonviolent resistance#atypicalreads#noncooperation#passive resistance

529 notes

·

View notes

Text

1968

Tenho como referência no ativismo político o saudoso Martin Luther King, morto aos trinta e nove anos, no dia quatro de abril de mil novecentos e sessenta e oito. Representando os interesses afro-estadunidense, na busca incansável pelos direitos civis, com sua característica singular contra o racismo através da não violência. Seu poder de oratória conseguiu oferecer um fluxo real de transformação no tecido social. Promovendo reflexão e união por meio de profundidade filosófica e método pacifista na obtenção da liberdade e igualdade. Não podemos ignorar os fatos históricos, o mundo conheceu uma das figuras mais marcantes e inspiradoras.

Recomendo uma publicação de 2014 da editora Zahar; O livro “A autobiografia de Martin Luther King”. Já fiz essa leitura e gostei bastante, é uma obra respeitável e muito bem organizada por Clayborne Carson. Achei que seria interessante deixar essa dica literária, fundamental no esclarecimento e resistência contra os absurdos que lamentavelmente presenciamos até os nossos dias. O material serve como um guia, um belo trabalho de elucidação, como esses comportamentos excludentes devem ser lembrados e extintos de nossa sociedade, não podemos nos atentarmos apenas na situação horrenda do preconceito racial nos EUA, mas também em tantos outros países com profundas marcas deixadas pelo colonialismo.

@buenoslibrosblog

#books#bookstagram#bookaddict#bookblr#livros#bookstan#books & libraries#booksbooksbooks#literatura#martin luther king jr#buenoslibrosblog#history#brazil

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Endnotes

Davies, Philip, and Iwan Morgan. From Sit-Ins to SNCC: The Student Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2012. muse.jhu.edu/book/17752.

Carson, Clayborne and ACLS Humanities E-Book. 1981. In Struggle: SNCC and the Black Awakening of the 1960s. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press.

Raiford, Leigh. “‘Come Let Us Build a New World Together’: SNCC and Photography of the Civil Rights Movement.” American Quarterly 59, no. 4 (2007): 1129–57. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40068483.

Maheo, Olivier. "The Enemy within: The Long Civil Rights Movement and the Enemy Pictures." Angles (Société Des Anglicistes De l'Enseignement Supérieur) 10, no. 10 (2020).

Raiford, Leigh. “‘Come Let Us Build a New World Together’: SNCC and Photography of the Civil Rights Movement.” American Quarterly 59, no. 4 (2007): 1129–57.

Shaffer, Graham P. "The Leesburg Stockade Girls: Why Modern Legislatures should Extend the Statute of Limitations for Specific Jim-Crow-Era Reparations Lawsuits in the Wake of Alexander v. Oklahoma." Stetson Law Review 37, no. 3 (2008): 941.

Ibid

Ibid

Raiford, Leigh. "Lynching, Visuality, and the Un/Making of Blackness." NKA (Brooklyn, N.Y.) 2006, no. 20 (2006): 22-31.

Raiford, Leigh. “‘Come Let Us Build a New World Together’: SNCC and Photography of the Civil Rights Movement.” American Quarterly 59, no. 4 (2007): 1129–57.

SNCC Digital Gateway Project https://snccdigital.org/inside-sncc/sncc-national-office/photography/

Cheryl Lynn Greenberg, ed., A Circle of Trust: Remembering SNCC (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1998), 38

0 notes

Text

Hierophant. Weiser Waite Smith Tarot

A religious figure sits in his ceremonial vestments. He bestows the Pope’s blessing upon the unseen congregation: first three fingers up, last two fingers down. The crossed keys represent the keys to heaven.

The Hierophant is given the number five, which is the number of completion. He is a five in perfect balance: all four elements—water, earth, air, fire—combined with the fifth, spirit. He calls us to be our higher selves, to find a perfect balance and lead others to their own.

The Hierophant is another name for the Pope. Don’t worry, you don’t have to take up religion when you get this card. It is more about becoming a leader, thinking outside your own concerns, and doing what is best for a community. You know how some athletes, musicians, and celebrities get caught up with drugs or the law, and then, when their fans express disappointment, they say, “I never asked to be a role model”? This card is the opposite of that.

The Hierophant asks us to be better. Not just better, but the most balanced, the most compassionate, the most enlightened version of ourselves. It sounds nice, right? Who doesn’t want to be his or her highest self? That’s what we think until it comes time to actually do it, which means we have to stop grumbling, find two socks that match, stop eating potato chips, and start devoting ourselves selflessly to a cause.

You become your highest self by blending the four elements of the tarot deck—Cups (emotions), Wands (passion), Swords (intellect), and Coins (pragmatism)—with a sense of spirituality. You can substitute morality here if you like. You remove your own private concerns because there’s simply no room for them. It’s a bit like the detachment taught in Buddhism or the denial of the ego in Christianity. When we let the ego rule, we get stuck with the Devil, who is ten cards up at number fifteen. Here you put aside your own needs and work from a place of virtue. That’s how you become a leader.

That does not mean you stop being a human being. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. is an excellent example of the Hierophant. He knew that by becoming a visible, vocal figurehead of the civil rights movement he would be a target of the FBI, racist loonies, and hate organizations. And yet he continued to put himself in danger year after year because he was on a mission greater than himself.

Dr. King’s writings still resonate, and they still inspire groups who are struggling for equal rights all over the world. His work transcended his human life.

Complications arise, however, when the Hierophant becomes powerful, as many great leaders can attest. With power comes the temptation to abuse that power and to use it thoughtlessly. And so King succumbed from time to time, to affairs with other women and so on. That does not diminish his greatness—mostly because he did not allow that side of him to go wild. But certainly other religious and social leaders (insert any number of politicians or religious leaders caught sexting, embezzling, or getting violent here) were not so disciplined.

When the Hierophant shows up, we need to question whether we need to step up as a leader in some way, whether we need to become active in a cause, whether we can be of service to something. It’s also about coming together as a group to create something larger than ourselves. Find a way in your work to be of service to a greater good and find it in you to unearth your higher self.

Recommended material.

Calvary, film directed by John Michael McDonagh

A Call to Conscience: The Landmark Speeches of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., book edited by Clayborne Carson and Kris Shepard

The Essential Rosa Luxemburg (Reform or Revolution and The Mass Strike), book by Rosa Luxemburg

Jessa Crispin

0 notes

Text

(PDF) [Download] Revel for the Struggle for Freedom, Volume 1: To 1877 -- Access Card BY : Clayborne Carson

[Read] PDF/Book Revel for the Struggle for Freedom, Volume 1: To 1877 -- Access Card By Clayborne Carson

Ebook PDF Revel for the Struggle for Freedom, Volume 1: To 1877 -- Access Card | EBOOK ONLINE DOWNLOAD

If you want to download free Ebook, you are in the right place to download Ebook. Ebook/PDF Revel for the Struggle for Freedom, Volume 1: To 1877 -- Access Card DOWNLOAD in English is available for free here, Click on the download LINK below to download Ebook After You 2020 PDF Download in English by Jojo Moyes (Author).

Download Link : [Downlload Now] Revel for the Struggle for Freedom, Volume 1: To 1877 -- Access Card

Read More : [Read Now] Revel for the Struggle for Freedom, Volume 1: To 1877 -- Access Card

Description

For courses in History of African AmericansA biographical approach to the African American experience Revel(TM) The Struggle for Freedom: A History of African Americans provides a compelling narrative of the black experience in America centered around individual African American lives. Emphasizing African Americans' insistent call to the nation to deliver on the constitutional promises made to all its citizens, authors Clayborne Carson, Emma Lapsansky-Werner, and Gary B. Nash weave African American history into a larger story of American economic and political history. The 3rd Edition offers fully updated content on the legacy of Barack Obama's presidency, the state of the contemporary struggle for African American freedom, and the meaning of the 2016 presidential election.Revel is Pearson's newest way of delivering our respected content. Fully digital and highly engaging, Revel replaces the textbook and gives students everything they need for the course. Informed by extensive

0 notes

Photo

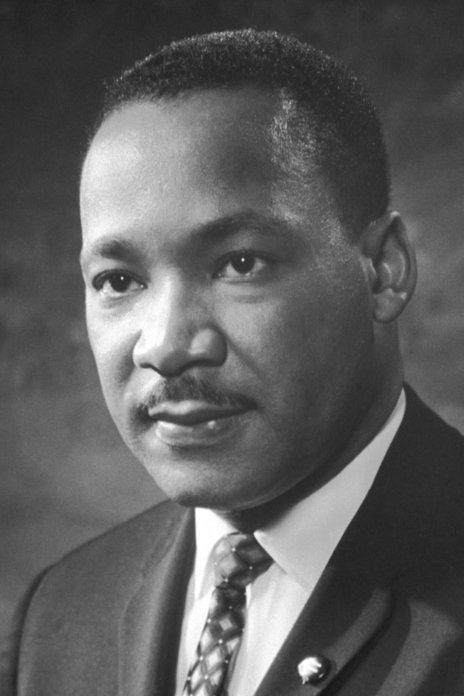

🕊Happy Martin Luther King Jr. Day! 🔊 Martin Luther King, Jr., was a religious leader and social activist who led the civil rights movement in the United States from the mid-1950s until his assassination in 1968. 📚 To learn more about Dr. King and his legacy, here are three book suggestions: * Martin Luther King Jr.: A Life, by Marshall Frady * The Autobiography of Martin Luther King, Jr., edited by Clayborne Carson * Parting the Waters: America in the King Years, 1954-63, by Taylor Branch . #mlkday #martinlutherking #civilrightsmovement #jeunesseglobal #civilrightsleader https://www.instagram.com/p/CnfQSgluKbG/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

0 notes

Text

"The history books, which had almost completely ignored the contribution of the Negro in American history, only served to intensify the Negroes' sense of worthlessness and to augment the anachronistic doctrine of white supremacy. All too many Negroes and whites are unaware of the fact that the first American to shed blood in the revolution which freed this country from British oppression was a black seaman named Crispus Attucks. Negroes and whites are almost totally oblivious of the fact that it was a Negro physician, Dr. Daniel Hale Williams, who performed the first successful operation on the heart in America. Another Negro physician, Dr. Charles Drew, was largely responsible for developing the method of separating blood plasma and storing it on a large scale, a process that saved thousands of lives in World War II and has made possible many of the important advances in postwar medicine. History books have virtually overlooked the many Negro scientists and inventors who have enriched American life. Although a few refer to George Washington Carver, whose research in agricultural products helped to revive the economy of the South when the throne of King Cotton began to totter, they ignore the contribution of Norbert Rillieuz, whose invention of an evaporating pan revolutionized the process of sugar refining. How many people know that multimillion-dollar United Shoe Machinery Company developed from the shoe-lasting machine invented in the last century by a Negro from Dutch Guiana, Jan Matzelinger; or that Granville T. Woods, an expert in electric motors, whose many patents speeded the growth and improvement of the railroads at the beginning of this century, was a Negro?

Even the Negroes' contribution to the music of America is sometimes overlooked in astonishing ways. In 1965 my oldest son and daughter entered an integrated school in Atlanta. A few months later my wife and I were invited to attend a program entitled "Music that has made America great." As the evening unfolded, we listened to the folk songs and melodies of the various immigrant groups. We were certain that the program would end with the most original of all American music, the Negro spiritual. But we were mistaken. Instead, all the students, including our children, ended the program by singing "Dixie"."

- Martin Luther King Jr., as quoted in Carson, Clayborne. 2001. The Autobiography of Martin Luther King, Jr., Grand Central Publishing. Cap: Black Power.

37 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Michael King Jr., commonly known as Martin Luther King Jr., was born on January 15, 1929 in Atlanta, Georgia. He was an American Baptist minister and activist who became the most visible spokesperson and leader in the civil rights movement from 1955 until his assassination in 1968. King is best known for advancing civil rights through nonviolence and civil disobedience, inspired by his Christian beliefs and the nonviolent activism of Mahatma Gandhi. He was the son of early civil rights activist Martin Luther King, Sr..

King participated in and led marches for blacks' right to vote, desegregation, labor rights, and other basic civil rights. King led the 1955 Montgomery bus boycott and later became the first president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). As president of the SCLC, he led the unsuccessful Albany Movement in Albany, Georgia, and helped organize some of the nonviolent 1963 protests in Birmingham, Alabama. King helped organize the 1963 March on Washington, where he delivered his famous "I Have a Dream" speech on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial.

The SCLC put into practice the tactics of nonviolent protest with some success by strategically choosing the methods and places in which protests were carried out. There were several dramatic stand-offs with segregationist authorities, who sometimes turned violent. FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover considered King a radical and made him an object of the FBI's COINTELPRO from 1963, forward. FBI agents investigated him for possible communist ties, recorded his extramarital liaisons and reported on them to government officials, and, in 1964, mailed King a threatening anonymous letter, which he interpreted as an attempt to make him commit suicide.

On October 14, 1964, King won the Nobel Peace Prize for combating racial inequality through nonviolent resistance. In 1965, he helped organize two of the three Selma to Montgomery marches. In his final years, he expanded his focus to include opposition towards poverty, capitalism, and the Vietnam War.

In 1968, King was planning a national occupation of Washington, D.C., to be called the Poor People's Campaign, when he was assassinated on April 4 in Memphis, Tennessee. His death was followed by riots in many U.S. cities. Allegations that James Earl Ray, the man convicted of killing King, had been framed or acted in concert with government agents persisted for decades after the shooting. King was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom and the Congressional Gold Medal. Martin Luther King Jr. Day was established as a holiday in cities and states throughout the United States beginning in 1971; the holiday was enacted at the federal level by legislation signed by President Ronald Reagan in 1986. Hundreds of streets in the U.S. have been renamed in his honor, and the most populous county in Washington State was rededicated for him. The Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., was dedicated in 2011.

Works

Stride Toward Freedom: The Montgomery Story (1958)

The Measure of a Man (1959)

Strength to Love (1963)

Why We Can't Wait (1964)

Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community? (1967)

The Trumpet of Conscience (1968)

A Testament of Hope: The Essential Writings and Speeches of Martin Luther King Jr. (1986)

The Autobiography of Martin Luther King Jr. (1998), ed. Clayborne Carson

"All Labor Has Dignity" (2011) ed. Michael Honey

"Thou, Dear God": Prayers That Open Hearts and Spirits Collection of King's prayers. (2011), ed. Lewis Baldwin

MLK: A Celebration in Word and Image Photographed by Bob Adelman, introduced by Charles Johnson

King was awarded at least fifty honorary degrees from colleges and universities. On October 14, 1964, King became the (at the time) youngest winner of the Nobel Peace Prize, which was awarded to him for leading nonviolent resistance to racial prejudice in the U.S. In 1965, he was awarded the American Liberties Medallion by the American Jewish Committee for his "exceptional advancement of the principles of human liberty." In his acceptance remarks, King said, "Freedom is one thing. You have it all or you are not free."

In 1957, he was awarded the Spingarn Medal from the NAACP. Two years later, he won the Anisfield-Wolf Book Award for his book Stride Toward Freedom: The Montgomery Story. In 1966, the Planned Parenthood Federation of America awarded King the Margaret Sanger Award for "his courageous resistance to bigotry and his lifelong dedication to the advancement of social justice and human dignity." Also in 1966, King was elected as a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. In November 1967 he made a 24-hour trip to the United Kingdom to receive an honorary degree from Newcastle University, being the first African-American to be so honoured by Newcastle. In a moving impromptu acceptance speech, he said:

There are three urgent and indeed great problems that we face not only in the United States of America but all over the world today. That is the problem of racism, the problem of poverty and the problem of war.

In addition to being nominated for three Grammy Awards, the civil rights leader posthumously won for Best Spoken Word Recording in 1971 for "Why I Oppose The War In Vietnam".

In 1977, the Presidential Medal of Freedom was posthumously awarded to King by President Jimmy Carter. The citation read:

Martin Luther King Jr. was the conscience of his generation. He gazed upon the great wall of segregation and saw that the power of love could bring it down. From the pain and exhaustion of his fight to fulfill the promises of our founding fathers for our humblest citizens, he wrung his eloquent statement of his dream for America. He made our nation stronger because he made it better. His dream sustains us yet.

King and his wife were also awarded the Congressional Gold Medal in 2004.

King was second in Gallup's List of Most Widely Admired People of the 20th Century. In 1963, he was named Time Person of the Year, and in 2000, he was voted sixth in an online "Person of the Century" poll by the same magazine. King placed third in the Greatest American contest conducted by the Discovery Channel and AOL.

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at http://justforbooks.tumblr.com

97 notes

·

View notes

Text

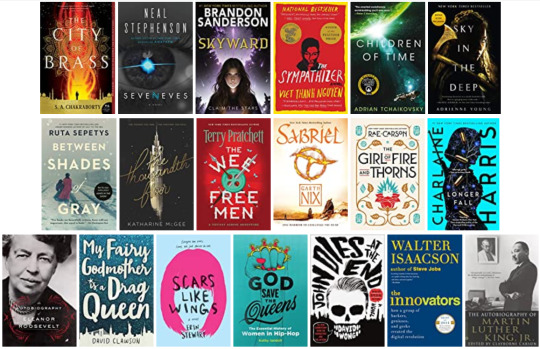

1/4 Book Deals

Good morning and a happy new year to you all! I realize I haven’t made a book deals post in a couple weeks, and this is my first major post so far this new year, so how are you all doing!? I hope you’ve all been doing super well and staying safe! Things have been getting pretty bad where I am (re: pandemic), so I’m just really hoping you’re all doing well wherever you are.

This year starts off with some great books on sale! I know that there were probably a lot of sales over the past week or so, but I was really just trying to take some time to relax and not focus on internet things so I probably missed them all, sorry! Today there’s a nice mix of fantasy, nonfiction, etc., so definitely have a look if you need some new books for the year! I’ve read a few of these and would highly recommend The Girl of Fire and Thorns, City of Brass, and Sabriel! I’ve been really wanting to check out The Sympathizer because I’ve heard wonderful things about it. Have you guys read any of these already?

Anyway, I hope you all have a wonderful first week of the new year! Hang in there, and happy reading! :)

Today’s Deals:

The City of Brass by S.A. Chakraborty - https://amzn.to/354Hejm

Seveneves by Neal Stephenson - https://amzn.to/2MxiFVX

Skyward by Brandon Sanderson - https://amzn.to/3ndmNqK

The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen - https://amzn.to/2XahAFC

Children of Time by Adrian Tchaikovsky - https://amzn.to/38eAn9c

Sky in the Deep by Adrienne Young - https://amzn.to/3oe1y9A

Between Shades of Gray by Ruta Sepetys - https://amzn.to/35bJAgy

The Thousandth Floor by Katharina McGee - https://amzn.to/2L0mMJF

The Wee Free Men by Terry Pratchett - https://amzn.to/35937y3

Sabriel by Garth Nix - https://amzn.to/3ncm893

The Girl of Fire and Thorns by Rae Carson - https://amzn.to/2Mtt70x

A Longer Fall by Charlaine Harris - https://amzn.to/3s0gwCz

The Autobiography of Eleanor Roosevelt by Eleanor Roosevelt - https://amzn.to/3oin39e

My Fairy Godmother is a Drag Queen by David Clawson - https://amzn.to/3rVl5h9

Scars Like Wings by Erin Stewart - https://amzn.to/3occqVm

God Save the Queens by Kathy Iandoli - https://amzn.to/3rSjZCT

John Dies at the End by David Wong - https://amzn.to/3ohjBLW

The Innovators by Walter Isaacson - https://amzn.to/3rRKyYO

The Autobiography of Martin Luther King, Jr. edited by Clayborne Carson - https://amzn.to/3oeDqDQ

NOTE: I am categorizing these book deals posts under the tag #bookdeals, so if you don’t want to see them then just block that tag and you should be good. I am an Amazon affiliate in addition to a Book Depository affiliate and will receive a small (but very much needed!) commission on any purchase made through these links.

#bookdeals#booksale#sa chakraborty#the city of brass#seveneves#neal stephenson#viet thanh nguyen#the sympathizer#children of time#adrian tchaikosky#adrienne young#ruta sepetys#terry pratchett#garth nix#rae carson#charlaine harris#eleanor roosevet#david wong#walter isaacson#mlk#martin luther king jr

33 notes

·

View notes

Note

can you assign books to psycho pass relationships like you did with musicals?

this is a great chance to rec my favorite romances! i shied away from tragedy and dourness and opted for empowered characters and hea’s (or otherwise emotionally satisfying endings)

if you like shinkane, you might vibe with:

the fire and thorns trilogy by rae carson – ya fantasy with latinx-inspired cultural elements centered on a coming-of-age story of an underestimated but savvy queen. it’s more focused on her journey but it also features her star-crossed relationship with her knight commander who serves as her personal guard and pines for her from afar.

the vampire academy series by richelle mead – one of the few unironically good things that came out of the vampire/paranormal-trend after twilight. the series is about a confident young woman who is training to be a guard for her best friend, a half-vampire princess. part of the heart of the story lies in this friendship but the other is in her romance with her russian mentor who is too serious and self-denying for his own good.

the winternight trilogy by katherine arden – russian medieval fantasy series featuring a rebellious misfit, vasya, who is outcast by her village because of her independent spirit and her ties with magic. this is less romance since it primarily focuses on vasya’s maturity as she becomes a warrior bent on saving her country from itself. but i had to add this one here because the (very koschei-esque death and the maiden) complicated romance she has with a frost demon king made me want to tear my hair out the same way as shinkane.

jane eyre by charlotte bronte – governess who has strong principles and a sense of self matches with a morally dubious byronic antihero blah blah old newsss

the governess affair by courtney milan – historical novella by my favorite romance author. i'm a huge historical romance reader but out of all of the ones i’ve read, a good portion of milan’s works strike me because the protags are not ducal or royalty and are truly ordinary people just trying to get by. the hero here is an enforcer who works for a duke and the heroine is a former governess seeking restitution for crimes the duke committed against her (cw for past rape but it’s only mentioned briefly and respectably as a plot point)

best of luck by kate clayborn – contemporary about a sheltered, kind woman who wins a lottery ticket and seeks to further the education she missed out on using the money. it's a “my best friend’s brother” kind of romance but i chose this one because the couple explores a dynamic echoed in shinkane: underestimated woman with a hidden spirit who falls in love with a wanderer who keeps moving because of his ghosts.

girl gone viral by alisha rai – contemporary interracial romance between a wealthy recluse suffering from anxiety disorder and ptsd and her faithful, tight-lipped bodyguard who is dealing with his own demons and has loved her for years. the seemingly unrequited pining and the mutual support are the highlights here.

ginaka

uprooted by naomi novik – fantasy stand-alone about a plucky, young woman who is chosen by the feared “dragon” as a sacrifice in exchange for her village’s well-being against the encroaching evil of the forest in their borderlands. the dragon mentioned is actually just howl jenkins if he was a prickly bastard who constantly underestimates the heroine. his ill regard slides off her like water on a duck’s back honestly she can’t be bothered lmao eventually when he realizes how compatible they are as partners, they start to work together to fend off the wood.

unraveled by courtney milan – uptight magistrate hell bent on doing his duty meets his match against a strong-willed seamstress who is just as stubborn in getting past his defenses as he is in putting them up. honestly, this remains like one of the hottest romance ive read that’s not an outright erotica

the duchess war by courtney milan – yes another milan but shes my fave i picked this one not necessarily because the characters have a likeness towards ginaka but because this is one of the few to feature a virgin hero with a genuine but also tender look into the development of a sexual relationship between two characters who are matched by their intellect rather than on their looks

north and south by elizabeth gaskell – i saw a text post that described this book as pride and prejudice for socialists which is apt lol i was going to pick p&p because darcy himself is someone who seems to be a curmudgeon asshole from a distance and is actually just misguided and proud but compassionate and socially awkward. so here’s a lesser-known pick with a similar archetype

the flatshare by beth o’leary – contemporary about two roommates who never see each other but begin an epistolary romance through post-it notes they leave around the flat. the heroine is bright and friendly while the hero is more reticent and sensible. (cw for stalking and emotional abuse)

love lettering by kate clayborn – contemporary between an artist who is passionate about her job and a business man who is decidedly not. i enjoyed this because it’s a book about mistakes and second chances. heroine is earnest and sometimes misguided while the hero is not necessarily a grump—just stoic and awkward.

you deserve each other by sarah hogle - a fun, light-hearted enemies-to-lovers of an established couple who realize that they might have rushed into an engagement without really getting to know each other. a battle of wills ensues on who gets to be the one to break things off but in the process of showing their true colors, they end up falling in love again. the core theme’s ultimately about breaking off from the constraints of other people’s expectations and reaffirming your authenticity. very ginaka-esque

well met by jen deluca - contemporary centered around the off-the-wrong-foot relationship between a spirited young woman and the too-serious high school teacher/director of a renaissance fair. the hero’s probably the closest in all of the romances ive read that’s most like gino

kougino

the soldier’s scoundrel by cat sebastian – one of the things i’m always wary about lgbt+ historical romance is the reality of history barging its ugly head. however, what i love about cat sebastian is that she really couldn’t give a shit like her books are grounded but they’re always optimistic. this one centers on the love story between a privileged and lonely former soldier and a private investigator with a sketchy reputation. kind of veers into enemies-to-lovers territory but the slow burn is honestly what makes it

second chance by jay northcote – hero a is a single father who escapes with his daughter back to his hometown where he reunites with his childhood best friend, hero b, who could not return his feelings at the time. what i loved about this was how honest their conversations were namely with hero a’s transition and issues of acceptance as a trans man and hero b’s alcoholism and depression. the story isn’t necessarily fluffy but it’s definitely not angsty at all. it’s a tender, uncontrived love story between two aging men with a shared history.

chaos station series by jenn burke and kelly jensen – sci-fi with kickass worldbuilding and a found family to cry over. at the heart of it is a second chance romance between two damaged soldiers who’ve been fucked over by their government and the war. i’m a huge sucker for us-against-the-world dynamics and this reminded me a lot of st*cky too believe it or not lmao

bad judgment by sidney bell – mystery/crime (one-sided) enemies-to-lovers between hero a seeking vengeance and hero b who is the bodyguard of a sketchy and dangerous asshole. this is not a fluffy read at all, probably the most intense out of all my recs but the slow burn is mariana zapata levels just with proper pacing and less purple prose (cw for violence and rape attempt)

a gentleman’s position by k.j. charles – historical with a king and lionheart dynamic. privileged and self-possessed noble denies himself his fixer/valet whom he’s loved for a long time because of class differences. the groveling here is simply chefs kiss

the wolf at the door by charlie adhara – shifter romance!! special agent paired with a werewolf to solve a string of murders. agent suspects his partner but is also incredibly attracted to him. this one has a nice blend of mystery/suspense and romance.

him by sarina bowen and elle kennedy – college hockey romance featuring “oh my god they were roommates” about two jock best friends who “ruin” their friendship with a one night stand. such a fun banter-y book that highlights their compatibility of being “bros” as much as their sexual chemistry of being lovers.

kunikara

gideon the ninth by tamsyn muir – recommended this before and i’m still in the middle of reading but i am having such fun with this one. it’s really a gift to find a loveable lesbian protagonist who is just genuinely cool and propped by gorgeous world building and plotting. what's really winning me over though so far is that the two women have intense chemistry but they are singularly fascinating characters individually. they are strong-willed and cutting and the instances they open up to each other to be tender are so well-earned

the lady’s guide to celestial machinations by olivia waite – the historical ff book of last year. it centers on an aspiring astronomer and the widow of a scientist. homophobia and sexism are very much present in the book but the core of it is just so soft and caring. like there’s no contrived drama or stupid misunderstanding. any conflict is just borne organically from the characters’ natural conceptions of their reality and their pasts.

and playing the role of herself by k.e. lane – seemingly one-sided love featuring an aspiring actress who gets a role acting alongside her more established and beautiful co-star. yayoi's anxieties in her relationship with shion echo so much in this book. but the care and love the two have for each other are undeniable and transgresses any fear or anxiety

tipping the velvet by sarah waters – aka cunnilingus (no im not kidding). this is less of the romance genre and more just a straight historical bildungsroman with lesbian romantic relationships. the main relationship centers on a girl who falls in love with a drag king performer and becomes her dresser. they become friends and fall in love, however reality interrupts. someone on goodreads described it as a dickenesque maurice but with lesbians and they would be exactly right.

the seven husbands of evelyn hugo by taylor jenkins reid – a confessional framed by a young journalist interviewing the elderly glam diva, evelyn hugo. the main core is evelyn’s journey as a willful cuban woman in hollywood who didn’t like that she was cuban or a woman. worse that she wasn’t afraid to be unlikable and strong-minded. the main emotional drive is the connection between the interviewer and evelyn but i had to include this here because evelyn’s relationship with the true romance of the story is heartbreaking and lovely (cw for domestic abuse and period-typical homophobia/biphobia)

the dark wife by sarah diemer – hades and persephone if hades was a woman! this retelling reinforces persephone’s agency from the original myth by emphasizing it alongside hades’s own affirmation of her journey. the other best parts about this is recasting demeter as less controlling and more protective for her own good reasons and zeus as the rightful villain that we know him to be.

proper english by k.j. charles – historical murder mystery set in edwardian england where sensible heroine meets her friend’s fiancée and initially dismisses her as being an airheaded pretty face but quickly falls in love. love a good u-hauling couple!

#reply.#anon.#pp.#notes.#edited to add well met! cant believe i forgot this gem#i’d rec some too for the ot3 but i dont read nearly enough poly romances to make a good list

23 notes

·

View notes

Link

On April 4, 1967, in front of a packed audience at the Riverside Church, King called the war “an enemy of the poor” that was swallowing the nation’s young men and its resources for antipoverty programs like a “demonic, destructive suction tube.”

King complained that black soldiers who couldn’t get their full rights at home were doing a disproportionate amount of the fighting in Vietnam. He also said that it was becoming difficult to tell young radicals in America not to pursue their agendas using violence when that’s what the nation was doing abroad.

Above all, the war in Vietnam symptomized a larger problem with American society, King said, calling for a rapid shift “from a thing-oriented society to a person-oriented society.”

“When machines and computers, profit motives and property rights, are considered more important than people, the giant triplets of racism, extreme materialism and militarism are incapable of being conquered,” King said.

Public condemnation came quickly, especially in the news media.

“Many who have listened to him with respect will never again accord him the same confidence,” the Washington Post said in an editorial. “He has diminished his usefulness to his cause, to his country and to his people.”

“The importance of King’s book — ‘Where Do We Go From Here?’ — we still haven’t answered that question,” said Clayborne Carson, the director of the MLK Research and Education Institute at Stanford University. “The ‘I have a dream’ speech is played 100 times as much as the Riverside speech...Probably every American knows the words — ‘I have a dream,’ ‘Free at last’ — those phrases.”

But when Americans listen to King speeches and see his memorials, Carson said, “You don’t see that phrase where he’s talking about the United States as ‘the greatest purveyor of violence in the world today.’”

247 notes

·

View notes

Text

“It must be remembered that genuine peace is not the absence of tension, but the presence of justice.” — Martin Luther King Jr.

#MLK#Martin Luther King Jr#Clayborne Carson#The Autobiography of Martin Luther King Jr#1960s#civil rights#civil rights movement#black history#black history month#black lives matter#black history matters#black authors#history#blm#black voices#bipoc#african american#peaceful protests#nonviolent resistance#atypicalreads#noncooperation#passive resistance

187 notes

·

View notes

Link

Published below is the introduction by World Socialist Web Site International Editorial Board Chairman David North to the forthcoming book, The New York Times’ 1619 Project and the Racialist Falsification of History. It is available for pre-order at Mehring Books for delivery in late January 2021.

The volume is a comprehensive refutation of the New York Times’ 1619 Project, a racialist falsification of the history of the American Revolution and Civil War. In addition to historical essays, it includes interviews from eminent historians of the United States, including James McPherson, James Oakes, Gordon Wood, Richard Carwardine, Victoria Bynum, and Clayborne Carson.

***

I should respectfully suggest that although the oppressed may need history for identity and inspiration, they need it above all for the truth of what the world has made of them and of what they have helped make of the world. This knowledge alone can produce that sense of identity which ought to be sufficient for inspiration; and those who look to history to provide glorious moments and heroes invariably are betrayed into making catastrophic errors of political judgment.—Eugene Genovese [1]

Both ideological and historical myths are a product of immediate class interests. … These myths may be refuted by restoring historical truth—the honest presentation of actual facts and tendencies of the past.—Vadim Z. Rogovin [2]

On August 14, 2019, the New York Times unveiled the 1619 Project. Timed to coincide with the four hundredth anniversary of the arrival of the first slaves in colonial Virginia, the 100-page special edition of the New York Times Magazine consisted of a series of essays that present American history as an unyielding racial struggle, in which black Americans have waged a solitary fight to redeem democracy against white racism.

The Times mobilized vast editorial and financial resources behind the 1619 Project. With backing from the corporate-endowed Pulitzer Center for Crisis Reporting, hundreds of thousands of copies were sent to schools. The 1619 Project fanned out to other media formats. Plans were even announced for films and television programming, backed by billionaire media personality Oprah Winfrey.

As a business venture the 1619 Project clambers on, but as an effort at historical revision it has been, to a great extent, discredited. This outcome is owed in large measure to the intervention of the World Socialist Web Site, with the support of a number of distinguished and courageous historians, which exposed the 1619 Project for what it is: a combination of shoddy journalism, careless and dishonest research, and a false, politically-motivated narrative that makes racism and racial conflict the central driving forces of American history.

In support of its claim that American history can be understood only when viewed through the prism of racial conflict, the 1619 Project sought to discredit American history’s two foundational events: The Revolution of 1775–83, and the Civil War of 1861–65. This could only be achieved by a series of distortions, omissions, half-truths, and false statements—deceptions that are catalogued and refuted in this book.

The New York Times is no stranger to scandals produced by dishonest and unprincipled journalism. Its long and checkered history includes such episodes as its endorsement of the Moscow frame-up trials of 1936–38 by its Pulitzer Prize-winning correspondent, Walter Duranty, and, during World War II, its unconscionable decision to treat the murder of millions of European Jews as “a relatively unimportant story” that did not require extensive and systematic coverage. [3] More recently, the Times was implicated, through the reporting of Judith Miller and the columns of Thomas Friedman, in the peddling of government misinformation about “weapons of mass destruction” that served to legitimize the 2003 invasion of Iraq. Many other examples of flagrant violations of even the generally lax standards of journalistic ethics could be cited, especially during the past decade, as the New York Times—listed on the New York Stock Exchange with a market capitalization of $7.5 billion—acquired increasingly the character of a media empire.

The “financialization” of the Times has proceeded alongside another critical determinant of the newspaper’s selection of issues to be publicized and promoted: that is, its central role in the formulation and aggressive marketing of the policies of the Democratic Party. This process has served to obliterate the always tenuous boundary lines between objective reporting and sheer propaganda. The consequences of the Times’ financial and political evolution have found a particularly reactionary expression in the 1619 Project. Led by Ms. Nikole Hannah-Jones and New York Times Magazine editor Jake Silverstein, the 1619 Project was developed for the purpose of providing the Democratic Party with a historical narrative that legitimized its efforts to develop an electoral constituency based on the promotion of racial politics. Assisting the Democratic Party’s decades-long efforts to disassociate itself from its identification with the social welfare liberalism of the New Deal to Great Society era, the 1619 Project, by prioritizing racial conflict, marginalizes, and even eliminates, class conflict as a notable factor in history and politics.

The shift from class struggle to racial conflict did not develop within a vacuum. The New York Times, as we shall explain, is drawing upon and exploiting reactionary intellectual tendencies that have been fermenting within substantial sections of middle-class academia for several decades.

The political interests and related ideological considerations that motivated the 1619 Project determined the unprincipled and dishonest methods employed by the Times in its creation. The New York Times was well aware of the fact that it was promoting a race-based narrative of American history that could not withstand critical evaluation by leading scholars of the Revolution and Civil War. The New York Times Magazine’s editor deliberately rejected consultation with the most respected and authoritative historians.

Moreover, when one of the Times’ fact-checkers identified false statements that were utilized to support the central arguments of the 1619 Project, her findings were ignored. And as the false claims and factual errors were exposed, the Times surreptitiously edited key phrases in 1619 Project material posted online. The knowledge and expertise of historians of the stature of Gordon Wood and James McPherson were of no use to the Times. Its editors knew they would object to the central thesis of the 1619 Project, promoted by lead essayist Hannah-Jones: that the American Revolution was launched as a conspiracy to defend slavery against pending British emancipation.

Ms. Hannah-Jones had asserted:

Conveniently left out of our founding mythology is the fact that one of the primary reasons the colonists decided to declare their independence from Britain was because they wanted to protect the institution of slavery. By 1776, Britain had grown deeply conflicted over its role in the barbaric institution that had reshaped the Western Hemisphere. In London, there were growing calls to abolish the slave trade … [S]ome might argue that this nation was founded not as a democracy but as a slavocracy. [4]

This claim—that the American Revolution was not a revolution at all, but a counterrevolution waged to defend slavery—is freighted with enormous implications for American and world history. The denunciation of the American Revolution legitimizes the rejection of all historical narratives that attribute any progressive content to the overthrow of British rule over the colonies and, therefore, to the wave of democratic revolutions that it inspired throughout the world. If the establishment of the United States was a counterrevolution, the founding document of this event—the Declaration of Independence, which proclaimed the equality of man—merits only contempt as an exemplar of the basest hypocrisy.

How, then, can one explain the explosive global impact of the American Revolution upon the thought and politics of its immediate contemporaries and of the generations that followed?

The philosopher Diderot—among the greatest of all Enlightenment thinkers—responded ecstatically to the American Revolution:

After centuries of general oppression, may the revolution which has just occurred across the seas, by offering all the inhabitants of Europe an asylum against fanaticism and tyranny, instruct those who govern men on the legitimate use of their authority! May these brave Americans, who would rather see their wives raped, their children murdered, their dwellings destroyed, their fields ravaged, their villages burned, and rather shed their blood and die than lose the slightest portion of their freedom, prevent the enormous accumulation and unequal distribution of wealth, luxury, effeminacy, and corruption of manners, and may they provide for the maintenance of their freedom and the survival of their government! [5]

Voltaire, in February 1778, only months before his death, arranged a public meeting with Benjamin Franklin, the much-celebrated envoy of the American Revolution. The aged philosophe related in a letter that his embrace of Franklin was witnessed by twenty spectators who were moved to “tender tears.” [6]

Marx was correct when he wrote, in his 1867 preface to the first edition of Das Kapital that “the American war of independence sounded the tocsin for the European middle class,” inspiring the uprisings that were to sweep away the feudal rubbish, accumulated over centuries, of the Ancien Régime. [7]

As the historian Peter Gay noted in his celebrated study of Enlightenment culture and politics, “The liberty that the Americans had won and were guarding was not merely an exhilarating performance that delighted European spectators and gave them grounds for optimism about man; it was also proving a realistic ideal worthy of imitation.” [8]

R.R. Palmer, among the most erudite of mid-twentieth century historians, defined the American Revolution as a critical moment in the evolution of Western Civilization, the beginning of a forty-year era of democratic revolutions. Palmer wrote:

[T]he American and the French Revolutions, the two chief actual revolutions of the period, with all due allowance for the great differences between them, nevertheless shared a great deal in common, and that what they shared was shared also at the same time by various people and movements in other countries, notably in England, Ireland, Holland, Belgium, Switzerland, and Italy, but also in Germany, Hungary, and Poland, and by scattered individuals in places like Spain and Russia. [9]

More recently, Jonathan Israel, the historian of Radical Enlightenment, argues that the American Revolution

formed part of a wider transatlantic revolutionary sequence, a series of revolutions in France, Italy, Holland, Switzerland, Germany, Ireland, Haiti, Poland, Spain, Greece, and Spanish America. … The endeavors of the Founding Fathers and their followings abroad prove the deep interaction of the American Revolution and its principles with the other revolutions, substantiating the Revolution’s global role less as a directly intervening force than inspirational motor, the primary model, for universal change. [10]

Marxists have never viewed either the American or French Revolutions through rose-tinted glasses. In examining world historical events, Friedrich Engels rejected simplistic pragmatic interpretations that explain and judge “everything according to the motives of the action,” which divides “men in their historical activity into noble and ignoble and then finds that as a rule the noble are defrauded and the ignoble are victorious.” Personal motives, Engels insisted, are only of a “secondary significance.” The critical questions that historians must ask are: “What driving forces in turn stand behind these motives? What are the historical causes which transform themselves into these motives in the brains of the actors?” [11]

Whatever the personal motives and individual limitations of those who led the struggle for independence, the revolution waged by the American colonies against the British Crown was rooted in objective socioeconomic processes associated with the rise of capitalism as a world system. Slavery had existed for several thousand years, but the specific form that it assumed between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries was bound up with the development and expansion of capitalism. As Marx explained:

The discovery of gold and silver in America, the extirpation, enslavement and entombment in mines of the aboriginal population, the beginning of the conquest and looting of the East Indies, the turning of Africa into a warren for the commercial hunting of black-skins, signalised the rosy dawn of the era of capitalist production. These idyllic proceedings are the chief momenta of the era of capitalist accumulation. [12]

Marx and Engels insisted upon the historically progressive character of the American Revolution, an appraisal that was validated by the Civil War. Marx wrote to Lincoln in 1865 that it was in the American Revolution that “the idea of one great Democratic Republic had first sprung up, whence the first Declaration of the Rights of Man was issued, and the first impulse given to the European revolution of the eighteenth century...” [13]

Nothing in Ms. Hannah-Jones’ essay indicates that she has thought through, or is even aware of the implications, from the standpoint of world history, of the 1619 Project’s denunciation of the American Revolution. In fact, the 1619 Project was concocted without consulting the works of the preeminent historians of the Revolution and Civil War. This was not an oversight, but rather, the outcome of a deliberate decision by the New York Times to bar, to the greatest extent possible, the participation of “white” scholars in the development and writing of the essays. In an article titled “How the 1619 Project Came Together,” published on August 18, 2019, the Times informed its readers: “Almost every contributor in the magazine and special section—writers, photographers and artists—is black, a nonnegotiable aspect of the project that helps underscore its thesis...” [14]

This “nonnegotiable” and racist insistence that the 1619 Project be produced exclusively by blacks was justified with the false claim that white historians had largely ignored the subject of American slavery. And on the rare occasions when white historians acknowledged slavery’s existence, they either downplayed its significance or lied about it. Therefore, only black writers could “tell our story truthfully.” The 1619 Project’s race-based narrative would place “the consequences of slavery and the contributions of black Americans at the very center of the story we tell ourselves about who we are.” [15]

The 1619 Project was a falsification not only of history, but of historiography. It ignored the work of two generations of American historians, dating back to the 1950s. The authors and editors of the 1619 Project had consulted no serious scholarship on slavery, the American Revolution, the abolitionist movement, the Civil War, or Jim Crow segregation. There is no evidence that Hannah-Jones’ study of American history extended beyond the reading of a single book, written in the early 1960s, by the late black nationalist writer, Lerone Bennett, Jr. Her “reframing” of American history, to be sent out to the schools as the foundation of a new curriculum, did not even bother with a bibliography.

Hannah-Jones and Silverstein argued that they were creating “a new narrative,” to replace the supposedly “white narrative” that had existed before. In one of her countless Twitter tirades, Hannah-Jones declared that “the 1619 Project is not a history.” It is, rather, “about who gets to control the national narrative, and, therefore, the nation’s shared memory of itself.” In this remark, Hannah-Jones explicitly extols the separation of historical research from the effort to truthfully reconstruct the past. The purpose of history is declared to be nothing more than the creation of a serviceable narrative for the realization of one or another political agenda. The truth or untruth of the narrative is not a matter of concern.

Nationalist mythmaking has, for a long period, played a significant political role in promoting the interests of aggrieved middle-class strata that are striving to secure a more privileged place in the existing power structures. As Eric Hobsbawm laconically observed, “The socialists … who rarely used the word ‘nationalism’ without the prefix ‘petty-bourgeois,’ knew what they were talking about.” [16]

Despite the claims that Hannah-Jones was forging a new path for the study and understanding of American history, the 1619 Project’s insistence on a race-centered history of America, authored by African-American historians, revived the racial arguments promoted by black nationalists in the 1960s. For all the militant posturing, the underlying agenda, as subsequent events were to demonstrate, was to carve out special career niches for the benefit of a segment of the African-American middle class. In the academic world, this agenda advanced the demand that subject matter that pertained to the historical experience of the black population should be allocated exclusively to African Americans. Thus, in the ensuing fight for the distribution of privilege and status, leading historians who had made major contributions to the study of slavery were denounced for intruding, as whites, into a subject that could be understood and explained only by black historians. Peter Novick, in his book That Noble Dream, recalled the impact of black nationalist racism on the writing of American history:

Kenneth Stampp was told by militants that, as a white man, he had no right to write The Peculiar Institution. Herbert Gutman, presenting a paper to the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History, was shouted down. A white colleague who was present (and had the same experience), reported that Gutman was “shattered.” Gutman pleaded to no avail that he was “extremely supportive of the black liberation movement—if people would just forget that I am white and hear what I am saying … [it] would lend support to the movement.” Among the most dramatic incidents of this sort was the treatment accorded Robert Starobin, a young leftist supporter of the Black Panthers, who delivered a paper on slavery at a Wayne State University conference in 1969, an incident which devastated Starobin at the time, and was rendered the more poignant by his suicide the following year. [17]

Despite these attacks, white historians continued to write major studies on American slavery, the Civil War and Reconstruction. Rude attempts to introduce a racial qualification in judging a historian’s “right” to deal with slavery met with vigorous opposition. The historian Eugene Genovese (1930–2012), the author of such notable works as The Political Economy of Slavery and The World the Slaveholders Made, wrote:

Every historian of the United States and especially the South cannot avoid making estimates of the black experience, for without them he cannot make estimates of anything else. When, therefore, I am asked, in the fashion of our inane times, what right I, as a white man, have to write about black people, I am forced to reply in four-letter words. [18]

This passage was written more than a half century ago. Since the late 1960s, the efforts to racialize scholarly work, against which Genovese rightly polemicized, have assumed such vast proportions that they cannot be adequately described as merely “inane.” Under the influence of postmodernism and its offspring, “critical race theory,” the doors of American universities have been flung wide open for the propagation of deeply reactionary conceptions. Racial identity has replaced social class and related economic processes as the principal and essential analytic category.

“Whiteness” theory, the latest rage, is now utilized to deny historical progress, reject objective truth, and interpret all events and facets of culture through the prism of alleged racial self-interest. On this basis, the sheerest nonsense can be spouted with the guarantee that all objections grounded on facts and science will be dismissed as a manifestation of “white fragility” or some other form of hidden racism. In this degraded environment, Ibram X. Kendi can write the following absurd passage, without fear of contradiction, in his Stamped from the Beginning:

For Enlightenment intellectuals, the metaphor of light typically had a double meaning. Europeans had rediscovered learning after a thousand years in religious darkness, and their bright continental beacon of insight existed in the midst of a “dark” world not yet touched by light. Light, then, became a metaphor for Europeanness, and therefore Whiteness, a notion that Benjamin Franklin and his philosophical society eagerly embraced and imported to the colonies. … Enlightenment ideas gave legitimacy to this long-held racist “partiality,” the connection between lightness and Whiteness and reason, on the one hand, and between darkness and Blackness and ignorance, on the other. [19]

This is a ridiculous concoction that attributes to the word “Enlightenment” a racial significance that has absolutely no foundation in etymology, let alone history. The word employed by the philosopher Immanuel Kant in 1784 to describe this period of scientific advance was Aufklärung, which may be translated from the German as “clarification” or “clearing up,” connoting an intellectual awakening. The English translation of Aufklärung as Enlightenment dates from 1865, seventy-five years after the death of Benjamin Franklin, whom Kendi references in support of his racial argument. [20]

Another term used by English speaking people to describe the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries has been “The Age of Reason,” which was employed by Tom Paine in his scathing assault on religion and all forms of superstition. Kendi’s attempt to root Enlightenment in a white racist impulse is based on nothing but empty juggling with words. In point of fact, modern racism is connected historically and intellectually to the Anti-Enlightenment, whose most significant nineteenth century representative, Count Gobineau, wrote The Inequality of the Human Races. But actual history plays no role in the formulation of Kendi’s pseudo-intellectual fabrications. His work is stamped with ignorance.

History is not the only discipline assaulted by the race specialists. In an essay titled “Music Theory and the White Racial Frame,” Professor Philip A. Ewell of Hunter College in New York declares, “I posit that there exists a ‘white racial frame’ in music theory that is structural and institutionalized, and that only through a reframing of this white racial frame will we begin to see positive racial changes in music theory.” [21]

This degradation of music theory divests the discipline of its scientific and historically developed character. The complex principles and elements of composition, counterpoint, tonality, consonance, dissonance, timbre, rhythm, notation, etc. are derived, Ewell claims, from racial characteristics. Professor Ewell is loitering in the ideological territory of the Third Reich. There is more than a passing resemblance between his call for the liberation of music from “whiteness” and the efforts of Nazi academics in the Germany of the 1930s and 1940s to liberate music from “Jewishness.” The Nazis denounced Mendelssohn as a mediocrity whose popularity was the insidious manifestation of Jewish efforts to dominate Aryan culture. In similar fashion, Ewell proclaims that Beethoven was merely “above average as a composer,” and that he “occupies the place he does because he has been propped up by whiteness and maleness for two hundred years.” [22]

Academic journals covering virtually every field of study are exploding with ignorant rubbish of this sort. Even physics has not escaped the onslaught of racial theorizing. In a recent essay, Chanda Prescod-Weinstein, assistant physics professor at the University of New Hampshire, proclaims that “race and ethnicity impact epistemic outcomes in physics,” and introduces the concept of “white empiricism” (italics in the original), which “comes to dominate empirical discourse in physics because whiteness powerfully shapes the predominant arbiters of who is a valid observer of physical and social phenomena.” [23]

Prescod-Weinstein asserts that “knowledge production in physics is contingent on the ascribed identities of the physicists,” the racial and gender background of scientists affects the way scientific research is conducted, and, therefore, the observations and experiments conducted by African-American and female physicists will produce results different than those conducted by white males. Prescod-Weinstein identifies with the contingentists who “challenge any assumption that scientific decision making is purely objective.” [24]

The assumption of objectivity is, she claims, a major problem. Scientists, Prescod-Weinstein complains, are “typically monists—believers in the idea that there is only one science … This monist approach to science typically forecloses a closer investigation of how identity and epistemic outcomes intermix. Yet white empiricism undermines a significant theory of twentieth century physics: General Relativity.” (Emphasis added) [25]

Prescod-Weinstein’s attack on the objectivity of scientific knowledge is buttressed with a distortion of Einstein’s theory.

Albert Einstein’s monumental contribution to our empirical understanding of gravity is rooted in the principal of covariance, which is the simple idea that there is no single objective frame of reference that is more objective than any other. All frames of reference, all observers, are equally competent and capable of observing the universal laws that underlie the workings of our physical universe. (Emphasis added) [26]

In fact, general relativity’s statement about covariance posits a fundamental symmetry in the universe, so that the laws of nature are the same for all observers. Einstein’s great (though hardly “simple”) initial insight, studying Maxwell’s equations on electromagnetism involving the speed of light in a vacuum, was that these equations were true in all reference frames. The fact that two observers measure a third light particle in space as traveling at the same speed, even if they are in motion relative to each other, led Einstein to a profound theoretical redefinition of how matter exists in space and time. These theories were confirmed by experiment, a result that will not be refuted by changing the race or gender of those conducting the experiment.

Mass, space, time and other quantities turned out to be varying and relative, depending on one’s reference frame. But this variation is lawful, not subjective—let alone racially determined. It bears out the monist conception. There are no such things as distinct, “racially superior,” “black female,” or “white empiricist” statements or reference frames on physical reality. There is an ascertainable objective truth, genuinely independent of consciousness, about the material world.

Furthermore, “all observers,” regardless of their education and expertise, are not “equally competent and capable” of observing, let alone discovering, the universal laws that govern the universe. Physicists, whatever their personal identities, must be properly educated, and this education, hopefully, will not be marred by the type of ideological rubbish propagated by race and gender theorists.

There is, of course, an audience for the anti-scientific nonsense propounded by Prescod-Weinstein. Underlying much of contemporary racial and gender theorizing is frustration and anger over the allocation of positions within the academy. Prescod-Weinstein’s essay is a brief on behalf of all those who believe that their professional careers have been hindered by “white empiricism.” She attempts to cover over her falsification of science with broad and unsubstantiated claims that racism is ubiquitous among white physicists, who, she alleges, simply refuse to accept the legitimacy of research conducted by black female scientists.

It is possible that a very small number of physicists are racists. But that possibility does not lend legitimacy to her efforts to ascribe to racial identity an epistemological significance that affects the outcome of research. Along these lines, Prescod-Weinstein asserts that the claims to objective truth made by “white empiricism” rest on force. This is a variant of the postmodernist dogma that what is termed “objective truth” is nothing more than a manifestation of the power relations between conflicting social forces. She writes:

White empiricism is the practice of allowing social discourse to insert itself into empirical reasoning about physics, and it actively harms the development of comprehensive understandings of the natural world by precluding putting provincial European ideas about science—which have become dominant through colonial force—into conversation with ideas that are more strongly associated with “indigeneity,” whether it is African indigeneity or another. (Emphasis added) [27]

The prevalence and legitimization of racialist theorizing is a manifestation of a deep intellectual, social, and cultural crisis of contemporary capitalist society. As in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, race theory is acquiring an audience among disoriented sections of middle-class intellectuals. While most, if not all, of the academics who promote a racial agenda may sincerely believe that they are combating race-based prejudice, they are, nevertheless, propagating anti-scientific and irrationalist ideas which, whatever their personal intentions, serve reactionary ends.

The interaction of racialist ideology as it has developed over several decades in the academy and the political agenda of the Democratic Party is the motivating force behind the 1619 Project. Particularly under conditions of extreme social polarization, in which there is growing interest in and support for socialism, the Democratic Party—as a political instrument of the capitalist class—is anxious to shift the focus of political discussion away from issues that raise the specter of social inequality and class conflict. This is the function of a reinterpretation of history that places race at the center of its narrative.

The 1619 Project did not emerge overnight. For several years, corresponding to the growing role played by various forms of identity politics in the electoral strategy of the Democratic Party, the Times has become fixated, to an extent that can be legitimately described as obsessive, on race. It often appears that the main purpose of the news coverage and commentary of the Times is to reveal the racial essence of any given event or issue.

A search of the archive of the New York Times shows that the term “white privilege” appeared in only four articles in 2010. In 2013, the term appeared in twenty-two articles. By 2015, the Times published fifty-two articles in which the term is referenced. In 2020, as of December 1, the Times had published 257 articles in which there is a reference to “white privilege.”

The word “whiteness” appeared in only fifteen Times articles in 2000. By 2018, the number of articles in which the word appeared had grown to 222. By December 1, 2020, “whiteness” was referenced in 280 articles.

The Times’ unrelenting focus on race during the past year, even in its obituary section, has been clearly related to the 2020 electoral strategy of the Democratic Party. The 1619 Project was conceived of as a critical element of this strategy. This was explicitly stated by the Times’ executive editor, Dean Baquet, in a meeting on August 12, 2019 with the newspaper’s staff:

[R]ace and understanding of race should be a part of how we cover the American story … one reason we all signed off on the 1619 Project and made it so ambitious and expansive was to teach our readers to think a little bit more like that. Race in the next year—and I think this is, to be frank, what I hope you come away from this discussion with—race in the next year is going to be a huge part of the American story. [28]

The New York Times’ effort to “teach” its readers “to think a little bit more” about race assumed the form of a falsification of American history, aimed at discrediting the revolutionary struggles that gave rise to the founding of the United States in 1776 and the ultimate destruction of slavery during the Civil War. This falsification could only contribute to the erosion of democratic consciousness, legitimize a racialized view of American history and society, and undermine the unity of the broad mass of Americans in their common struggle against conditions of social inequality and exploitation.

The racialist campaign of the New York Times has unfolded against the backdrop of a pandemic ravaging working-class communities, regardless of race and ethnicity, throughout the United States and the world. The global death toll has already surpassed 1.5 million. Within the United States, the number of COVID-19 deaths will surpass 300,000 before the end of the year. The pandemic has also brought economic devastation to millions of Americans. The unemployment rate is approaching Great Depression levels. Countless millions of people are without any source of income and depend upon food banks for their daily sustenance.

#new york times#wsws#1619 project#race#racism#racialism#whiteness#white privilege#american history#US history

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sources

Carson, Clayborne and ACLS Humanities E-Book. 1981. In Struggle: SNCC and the Black Awakening of the 1960s. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press.

Cheryl Lynn Greenberg, ed., A Circle of Trust: Remembering SNCC (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1998), 38

Davies, Philip, and Iwan Morgan. From Sit-Ins to SNCC: The Student Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2012. muse.jhu.edu/book/17752.

Kelen, Leslie G., Julian Bond, Clayborne Carson, Matt Herron, Charles E. Cobb Jr, and Project Muse University Press eBooks. This Light of Ours: Activist Photographers of the Civil Rights Movement, edited by Leslie G. Kelen. 1st ed. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2011;2012;.

Maheo, Olivier. "The Enemy within: The Long Civil Rights Movement and the Enemy Pictures." Angles (Société Des Anglicistes De l'Enseignement Supérieur) 10, no. 10 (2020).

Raiford, Leigh. “‘Come Let Us Build a New World Together’: SNCC and Photography of the Civil Rights Movement.” American Quarterly 59, no. 4 (2007): 1129–57. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40068483.

Raiford, Leigh. "Lynching, Visuality, and the Un/Making of Blackness." NKA (Brooklyn, N.Y.) 2006, no. 20 (2006): 22-31.

Shaffer, Graham P. "The Leesburg Stockade Girls: Why Modern Legislatures should Extend the Statute of Limitations for Specific Jim-Crow-Era Reparations Lawsuits in the Wake of Alexander v. Oklahoma." Stetson Law Review 37, no. 3 (2008): 941.

SNCC Digital Gateway Project https://snccdigital.org/.

1 note

·

View note

Text

In the present, a time of social crisis and uncertainty, the first and second Revolutions are the subject of intense controversy. The World Socialist Web Site will be celebrating the 244th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence by hosting a discussion with five eminent historians, Victoria Bynum, Clayborne Carson, Richard Carwardine, James Oakes and Gordon Wood. They will assess the Revolutions in the context of their times as well as their national and global consequences. Finally, the discussants will consider the possible implications of contemporary debates over the nature of the Revolutions for the future of the United States and the world.

#socialism#socialist equality party#wsws#independenceday#revolution#democracy#declaration of independance#fourth of july#independance day#historians

4 notes

·

View notes

Quote

I often say that if we, as a people, had as much religion in our hearts and souls as we have in our legs and feet, we could change the world.

The Autobiography of Martin Luther King, Jr, edited by Clayborne Carson

0 notes