#David O. Selznick

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Gone with the Wind (1939), David O. Selznick

#gone with the wind#david o. selznick#cinematography#ernest haller#american cinema#scarlett o'hara#vivien leigh#1930s

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cosplay the Classics: Alida Valli in Walk Softly, Stranger (1950)

My closet cosplay of Alida Valli in Walk Softly, Stranger

The Star

When Alida Valli arrived in America, she arrived with ten years of screen experience under her belt and thirty credits—a substantial resume for a twenty-six-year-old. By the 2000s, Valli had committed over one hundred roles to film, on top of her television and theatrical work. In her seven-decade film career, Valli demonstrated outstanding versatility as genres shifted and styles evolved. In a half dozen countries, a bevy of heavy hitters directed her: Alfred Hitchcock, Pier Paolo Passolini, Luchino Visconti, Carol Reed, Mario Bava, Georges Franju, Margarethe von Trotta, Dario Argento, Bernardo Bertolucci, Michelangelo Antonioni, and Claude Chabrol, to name just a few.

She became one of the most accomplished performers to ever emerge from Italian cinema, though Alida Valli’s American period seems like a footnote to her rich biography and filmography. (With the exception, of course, of the British-American production, The Third Man (1949)). How did Hollywood stardom evade such a talented, experienced young actor with a face that photographed beautifully from every angle? Well, let’s begin at the beginning.

Alida Altenburger, later Valli, was born in what was Pola, Italy—and is now Pula, Croatia—to a noble family that would soon relocate to Como in the north of Italy. When Alida was in her teens, she enrolled in the Centro sperimentale di cinematografia in Rome to study screen acting. The young Alida must have displayed some natural talent because her first film credit came just a year or so later.

Valli quickly became a popular star—primarily in telefoni bianchi (White Telephone) films. Telefoni bianchi was a film genre/stylistic movement aesthetically characterized by art deco. The films often depicted luxurious and/or bourgeois lifestyles; as a white telephone was a symbol of status, it in turn became a symbol of the genre. Telefoni bianchi films are typically comedic or light in tone and they avoid suggestions of intellectual depth or addressing social issues. As you probably already know, to consciously avoid “politics” is always a political decision. This movement was part of a broader push under Mussolini’s National Fascist Party to cultivate an aspirational fiction of affluent urbanity and to forge a new ideal of Italian-ness based largely on consumerism and consumer goods. The relatively carefree lifestyles depicted in the telefoni bianchi films was far removed from the lived reality of the majority of Italians during the global depression of the 1930s.

(Oversimplified-but-probably-necessary historical notes here: Italy as a single, unified nation was only about sixty-years-old at this point; meaning a unified sense of Italian-ness was kinda new. Then, in the first half of the twentieth century, Europe saw huge cultural and social changes engendered by industrialization, imperialism, and war. Use of mass media was a key factor in the nationalist goals of Mussolini’s government to shape a new new definition of modern Italian-ness.)

The rise of telefoni bianchi films was in large part due to Italy cutting down on importing American movies in the 1930s. Telefoni bianchi were one way to fill that gap, not simply by reflecting the polish and sheen of Hollywood productions but also by retooling American-style propaganda for Italian audiences. The emphasis on simplified narratives in telefoni bianchi stories, where any problem can be faced with good, traditional values and hard work, is a direct descendant of similar American films of the period. [1]

Alida Valli in the telefoni bianchi film Ore 9: lezione di chimica (1941)

Likewise, up-and-coming stars, like Alida Valli, were built up to replace (and hopefully surpass) American stars who were popular in Italy. One fan magazine somewhat superficially compared Valli to Loretta Young. They were both fresh-faced starlets who started to work professionally from a very young age, but their typical roles and styles of characterization were very different. However, I do think it’s worth noting that both actresses were often paired with older male leads early in their careers. The teen-aged Valli made multiple films with Amadeo Nazzari, who was fourteen years her senior. Teen-aged Young had some of her first major roles opposite Lon Chaney (thirty years older), Conway Tearle (thirty-five (!!!) years older), Ronald Colman (twenty-two years older), and John Barrymore (thirty-one years older). Additionally, in my opinion, playing in adult roles so young had the unintended consequence of both actresses playing more mature roles sooner than seems logical.

Of this period in Valli’s career, in his book Mussolini’s Dream Factory, Stephen Gundle wrote:

“Valli was predominantly an ingénue. She played fiancées, schoolgirls, daughters of industrialists and taxi drivers, dancers, secretaries and students. She was one of the many new faces that lent their countenances to a gallery of female types that corresponded to roles available to young women at the time.”

The two most cited films of Valli’s telefoni bianchi era are Mille lire al mese / A Thousand Lire per Month (1939) and Ore 9: lezione di chimica / Schoolgirl Diary (1941). I have yet to track down a copy of Mille lire, but, if Ore 9 is a representative indication of Valli’s telefoni-bianchi work, the reason for her massive popularity is clear: Valli’s Anna has youthful exuberance tempered with an acerbic and headstrong edge. From a technical perspective, Valli displays sharp comedic timing and perfectly executed control over her voice, facial expressions, and body language. (These are skills I knew Valli had from her later work, but it is a revelation to see that she already had them at only 19-20 years old!)

Though she was a staple star of telefoni bianchi, Valli branched out into more dramatic roles by the end of the decade; making a mark especially in period dramas. The characterization that first proved Valli’s dramatic chops was Luisa in Piccolo mondo antico / Old-Fashioned World (1941). Piccolo mondo was part of yet another emergent, albeit short-lived, Italian cinematographic movement: calligrafismo. This movement was more stylistically diverse than telefoni bianchi, but has likewise been criticised for avoiding deeper themes or social commentary. Calligrafismo films focused on formal sophistication—meant to emphasize film as art and Italian technical prowess—and literary source material—usually from the 19th century. Piccolo mondo is a lauded representative of calligrafismo and its director, Mario Soldati, is considered one of the movement’s premiere practitioners.

Alida Valli in Piccolo mondo antico (1941)

Valli’s character Luisa is a woman of bourgeois status who marries a nobleman for love and has to suffer the consequences. The events of Piccolo mondo take place over the course of a decade and so the then twenty-year-old Valli had to play Luisa as: a hopeful but anxious young bride, a faithful and self-possessed wife and mother, and many stages of extreme grief over the loss of a child and estrangement from her husband. Giving such a role to a performer that young, I think, could easily result in histrionics, but Valli genuinely pulls it off. Valli managed to give Luisa dignity and melancholy that belied her performer’s age. Her work particularly in the last third of the film is very strong and effectively heart-rending.

At the start of the decade, Valli firmly established the breadth of her technical abilities as an actor, but, in 1943, Mussolini’s fascist regime collapsed. Reflecting later in 1965 on her work in the 1930s and early ‘40s, Valli stated:

“I was a young girl, 16, 17, 18 years old and I was successful and privileged. Everything was easy and when things come to you easily you do not stop to ask if things are right or not. I made films as automatically as a secretary types a letter. If no one explains to you what evil is, how do you know what is evil? … I never thought that a cinema like that [i.e. white telephone films] was wrong or that it would end, because no one thought that Fascism would end.” [2]

Valli’s candor here is appreciated; highlighting the ignorance that privilege can breed. It’s a strange position for a teenager to be in, not formally tied or allegiant to Fascism, but still part of the corporatist machine that props it up.

The new government of Italy signed an armistice with the Allies, but then Nazi Germany invaded and occupied the north of Italy. The majority of professionals in the film industry, which was centered almost exclusively in Rome at the time, refused to collaborate with the invaders. Some filmmakers fled to Venice to establish a film colony there. Valli made the decision to “retire” from acting. Her refusal to work on films for the occupiers made Valli a target, but, with the help of friends, she was able to stay in her beloved Rome, albeit in hiding. It was while Valli was in hiding that she met and married her husband, musician Oscar de Mejo.

Valli’s “retirement” ended in 1945, though she had not been absent from Italian screens in the interim, as her earlier films were still circulating. Valli soon had an especially well-regarded turn in Eugenia Grandet (1946) as the long-suffering daughter of a wealthy miser. Valli’s performance as the title character displays all of the variety and depth she had cultivated in her first decade in film—and it was captured beautifully by cinematographer Václav Vích. Returning to the screen after the war, and contending with your star image potentially being associated with a fallen fascist regime, must have been massively challenging for the twenty-five-year-old. Despite her success in Eugenia Grandet, the potential of a fresh start in America must have seemed promising for Valli—with her husband and baby in tow, of course.

Alida Valli in Eugenia Grandet (1946)

Unfortunately, the notorious David O. Selznick was the one who scouted Valli.

The first film she made for Selznick was The Paradine Case (1947), directed by Alfred Hitchcock. Valli was still learning English while the film was in production and, as a result, had to study her lines phonetically. You would never guess that watching the film as Valli gives a layered performance with intriguing nuance in much of her line delivery. The Paradine Case had a troubled production and it is understandably regarded as a lesser film of Hitchcock’s, Valli’s work is the strongest aspect of the film.

Selznick’s plans for Valli lacked forethought and were in no way based on her versatility or unique skills as a performer. Selznick’s marketing for the star harped on her becoming the next Bergman or Garbo, rather than the first Alida Valli. Starting with Valli’s very first Selznick production, rather than getting a typical title card for her credit, she was represented solely as “Valli” with a cursive namemark. Selznick explained this odd decision as a way to evoke Garbo-ness. (Although, it was actually Nazimova who originated the namemark gimmick in the US.) The “Valli” gimmick did not offer the mystique Selznick had imagined. Alida Valli herself recounted how foolish the marketing was if for no other reason than that there was an established, popular star called Rudy Vallée around. Having David O. thoughtlessly micromanaging her star image meant that Valli’s adjustment to the Hollywood system of filmmaking was the equivalent of playing on hard mode.

“‘In Europe, actors are just people. We have to do things for ourselves,’ she explained. ‘But suddenly, I sign the American contract, and everything is done for me as if by magic. I am no longer a person—I am a Thing.’” —Valli quoted in “Double Life” by Inez Robb in Modern Screen, June 1948[3]

Valli’s second American film was the forgettable The Miracle of the Bells (1948). However, while The Third Man would be Valli’s next release, the film I’m cosplaying here, Walk Softly, Stranger, was already in the can. Selznick disliked the original ending of WSS and demanded re-writes and re-shoots. Selznick’s ending satisfied no one. Howard Hughes, whose distribution company, RKO, was handling the film’s release, reportedly chose to shelve WSS. But, after the success of The Third Man, Hughes wished to capitalize on the pairing of Joseph Cotten and Valli. WSS was un-shelved nearly two years after it was produced; unfortunately retaining its egregious, tacked-on “happy” ending (which I’ll talk more about later).

Portrait of Alida Valli from Modern Screen, June 1948

After her fifth film, The White Tower (1950), Valli bought herself out of her contract and returned to Europe. Why Valli left so abruptly is likely a mix of personal and professional issues. While filming The White Tower, Valli was having marital issues and she was pregnant with her second child. According to Valli, Selznick did not want his star to be pregnant. Working under Selznick seemed nightmarish. In addition to the ridiculous constraints on how she was meant to conduct her personal life, it must have been clear to Valli by 1950 that she would never have the opportunities to build a career with the same range that she had proven herself capable of in Italy.

Why Valli left Hollywood is maybe not such a great mystery. Regardless, it’s also clear that if the rigid studio system had thoughtfully cast Valli in higher quality material and/or allowed her to do comedy—something she brought up multiple times in the press while she was in the US—the American viewing public might have had a better chance to appreciate her skill. Selznick instead took a stellar actress and limited her to a knock-off Bergman. What a massive waste.

Valli’s American period was inarguably difficult, but it seemed to galvanize her for her return to Europe. Despite a rather large hiccup in her personal life that affected her career in the early 1950s, Valli found international acclaim. Valli not only worked in her native Italy, but also Spain, France, Britain, Mexico, and, yes, even the United States again. From the 1950s to the 2000s, Valli traversed new genres, styles, and movements freely and with dauntless creativity. If you mostly know Alida Valli for The Third Man (or perhaps for her supporting roles in giallo classics like Suspiria (1977) or Lisa and the Devil (1973)), take this essay as a prompt to check out more of her work! I plan to as well because I’ve seen her in over a dozen films and still feel like I’ve only scratched the surface!

——— ——— ———

[1] I’ve seen the work of Sicilian-born American director Frank Capra listed as a primary influence on these films—something I’d like to research further to be perfectly honest!

[2] from O. Fallaci, ‘Lo specchio del passato’, L’Europeo, 14 January 1965. but cited from Gundle’s Mussolini’s Dream Factory. Gundle doesn’t specify, but I assume this is his own translation from the original Italian.

[3] If you’ve researched fan magazines before (or have read any of my “Lost, but Not Forgotten” series), you already know that the historical value of fan magazine profiles and interviews is less about facts and more about what they express about what stars/their management/their studios wanted the public to think about them. For example, highlighting that a star is an avid reader to give the viewing public the notion that the star is intellectual or focusing on a star engaging in domestic activities to create a wholesome image. Though I’m using what isn’t likely a direct and unedited quote from Valli here, she expressed very similar sentiments in television interviews in France and Italy in the latter half of her life. So, while anything printed in these profiles should typically be taken with a grain, or a whole shaker-full, of salt, having the same sentiment spoken on camera by Valli herself makes this quote more compelling in its accuracy!

——— ——— ———

The Film

Joseph Cotten and Valli in Walk Softly, Stranger

To defer to Eddie Muller: Walk Softly, Stranger is a noir “near miss.” Rather than a proper film noir, it’s a romantic melodrama with a little noir seasoning, marred by studio interference. But, WSS’s complicated romantic storyline and noir-ish subplot, not to mention great performances by the leads and support, stick with you—even if the aforementioned tacked-on ending spoils the final effect.

My closet cosplay of Alida Valli in Walk Softly, Stranger

A Mysterious Stranger (Cotten) arrives in Ashton, a picture-postcard of small-town America—down to the big factory owning practically everything in said small town. With a touch of recon, the stranger ingratiates himself to a magnanimous local widow, Mrs. Brentman (Spring Byington). She even helpfully produces his pseudonym for him: Chris Hale, the boy child of the family who lived in her house before her. In this opening sequence, Chris is established as an adept wheeler dealer.

After securing lodging, Chris’s next target becomes Elaine Corelli (Valli), the daughter of the factory’s owner. Chris lays it on thick, but he’s missing a key bit of information: Elaine is now in a wheelchair. A few months prior to their meeting, Elaine took a bad fall on a ski jump and took permanent damage. So begins a fraught love story between Chris and Elaine.

Chris starts getting comfortable in his new identity. He has a home, a job, friends, a doting auntie, and is dating the richest girl in town. What’s initially meant to be a chance to lie low starts to seem like a genuine second chance at a normal life. The suspense kicks in when this unexpected peace is put in jeopardy as a character from Chris’s old life shows up in town unannounced. When Chris is eventually cornered by his criminal former cohorts, it results in Chris getting ventilated, a massive car accident, and then, unexpectedly, Chris still alive and headed to prison.

Collage of the hair and makeup reference photos of Valli I used for this cosplay

WSS is a languidly paced movie, matching the sleepy-but-contented nature of Ashton. It’s an unsung example of one of my favorite narrative devices: the city as a character. Personally, I think this is a key reason why WSS’s ending is so jarring. Ashton is socially stratified, but it’s still a town with communal spirit. It’s exactly this spirit that gives Chris the false hope of a fresh start—a nostalgic yearning not for what-was but for what-could-have-been. In the original script’s ending, Chris’ death is implied and Mrs. Brentman passes along the poem “John Brown’s Body” to Elaine. It’s a melancholic ending that both matches the Sehnsucht-ish tone of the film and taps into the film’s theme of alienation within an idyllic image of the American Dream. The re-worked ending has a rambunctious energy, nonsensical Will-Hayes-ian logic, and a troubling continuation of Chris and Elaine’s relationship.

In addition to the regrettable ending, I also feel that WSS missed an opportunity to examine Elaine’s character arc thoughtfully. Elaine first appears alone on the patio of the Ashton country club while there’s a lively party going on inside. We get to know Elaine along with Chris; as we share his perspective for the whole of the film. It’s clear that her recent disabling event has left her in a well of self-pity. There’s not much time devoted to Elaine’s new quotidian reality, because the film is really Chris’ story. So, a lot of what we learn about Elaine is indirect. For example, we learn how long it’s been since Elaine’s accident via a social column. From the way Elaine speaks and the micro-expressions and reactions that Valli registers, it can be inferred that Elaine was a social butterfly before her St. Moritz accident—but also that her social circle was composed of fair-weather friends. Elaine is almost always by herself when we (and Chris) encounter her. This makes her seem not only chronically isolated, but vulnerable. And, since we know Chris is not exactly on the level, this creates an interesting tension that the filmmakers seem only mildly aware of.

Much of Elaine’s dialogue about herself is rife with internalized ableism. She even goes so far as to liken her current state to death. Of course, Elaine is still new to her disability and the grief experienced during the adjustment period from able-bodied to disabled in an ableist society is real and common. WSS would be a stronger film if this element had been examined with a bit more perspective. The film does, however, touch on a complicating factor to Elaine’s experience of disability: the privileges she’s afforded as a wealthy person. Even though Elaine is often reliant on others to compensate for the lack of accessibility you would expect in 1940s America, she has the resources and capacity to take long trips and go out and socialize. There’s certainly no hint of trouble in paying medical bills—she’s literally the richest girl in town. Addressing Elaine’s social and economic privilege is not very thoughtfully done however, as Chris’ challenge to Elaine’s self-pity is flattened into patronizing abled savior type stuff.

That said, to Chris, Elaine is neither a target of pity nor someone who needs to be taken care of. She’s simply a very pretty, very rich girl that he’s very attracted to. Her disability is not coupled with any infantilization or inherent character defect—both all too common tropes in Hollywood films. I’ll admit, for a film to admit that a woman being disabled doesn’t make her less desirable is nice to see (and unfortunately is still a novelty), but how WSS handles it leaves a lot to be desired.

Alida Valli in Walk Softly, Stranger

There’s more depth to Elaine than we usually get for disabled women on film—particularly women with visible disabilities—even though she’s not a fully-developed lead. Valli’s performance imbues Elaine with intellect, dignity, and complex, layered emotions. There’s a scene shortly before the climax of the film where Elaine and Chris have an earnest conversation about where they stand with one another. It’s revealed that Elaine has known Chris was a phony from their very first meeting when he slipped up with one of his lies. Through this one reveal, we learn by implication that Elaine was never a dupe and that in those situations where she seemed vulnerable to him, she wasn’t. Regardless of how many windows Chris entered by unbidden, Elaine had more control of the situation than we, and Chris, realized.

Chris’ and Elaine’s arcs in the film align in that both learn to accept a new way of life. For Chris, it’s about recognizing that he can, in fact, lead an honest life and that he’s entitled to one (after righting his past wrongs of course). For Elaine, it’s recognizing that St. Moritz was not the end of her life and that her future will be different but still full of potential. This theme of new life is sublimated in the scene where Chris and Elaine lay their respective cards on the table—this discussion doesn’t take place in the library, where they normally hang out, but in a solarium surrounded by lush plants.

WSS careens disjointedly into its final sequence. Chris has survived an encounter with a gambling kingpin and he’s serving time. (For which crime though? And under his assumed name?) Elaine is there to meet him as he’s transferred from the hospital ward to the penitentiary. Elaine explains that she’s going to wait for him. This revelation is couched in a self-hating, ableist monologue. Where it seemed just a few scenes ago that Elaine was making progress, suddenly she thinks that she and Chris will “deserve” one another more when he’s an ex-convict, broken by the system. (???) Her own estimation of herself should have transformed by this point in the story. In what’s supposed to be a hopeful coda, any suggestion of character development for Elaine is summarily wiped out.

All that said, I still recommend checking out WSS. It’s a nuanced, affecting melodrama and a complicated entry in the evolution of disability representation in Hollywood films. The dialogue is snappy and it has an interesting story structure; buffeting between the relative peace of Ashton life and Chris’ criminal undertakings. Alida Valli and Joseph Cotten are always worth watching and Spring Byington is as delightful as ever as the lonely and sweet landlady.

If you’d like a noir-inspired double feature with Walk Softly, Stranger, Out of the Past (1947) also features a former criminal who tries to find a new life on the straight and narrow, which turns out to be too narrow. Or watch it with Hollow Triumph (1948), where a criminal tries to hide out in a small town by taking over a local’s identity. (An added benefit to HT is that it has some entertainingly off-the-wall plot devices.)

——— ——— ———

☕Appreciate my work? Buy me a coffee! ☕

——— ——— ———

Further Reading/Viewing

Mussolini’s Dream Factory: Film Stardom in Fascist Italy by Stephen Gundle

Spellbound by Beauty: Alfred HItchcock and His Leading Ladies by Donald Spoto

Il romanzo di Alida Valli by Lorenzo Pellizzari and Claudio M. Valentinetti

The RKO Story by Richard B. Jewell and Vernon Harbin

Alida / Alida Valli: In Her Own Words (2021)

#Alida Valli#1940s#1950s#cosplay#film#cinema#american film#classic movies#classic film#cinema italiano#film stars#filmblr#film history#history#David O. Selznick#film noir#noir#noirvember#robert stevenson#classic cinema#old hollywood#cosplay the classics#closet cosplay#classic hollywood#hollywood#Joseph Cotten

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

David O, Selznick poses in front of a portrait of Vivien Leigh as Scarlett O'Hara in GONE WITH THE WIND (1939), his most famous production.

103 notes

·

View notes

Text

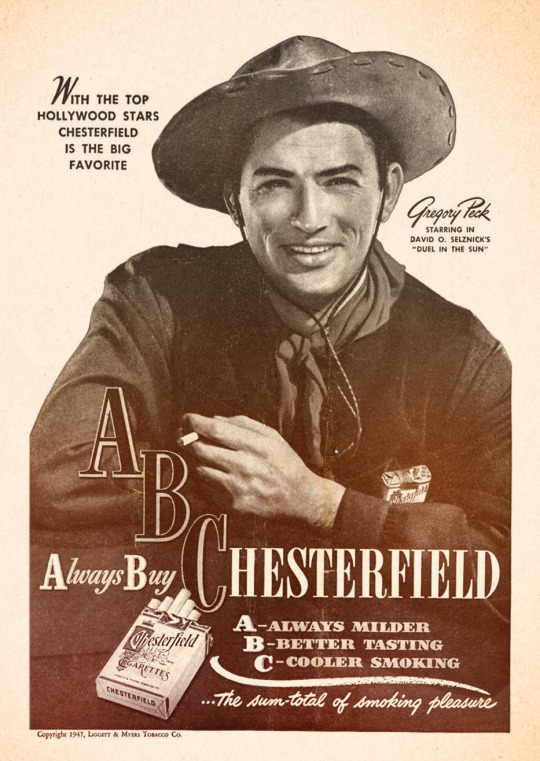

Gregory Peck for Chesterfield cigarettes.

#vintage advertising#cigarettes#cigarette advertising#tobacco#big tobacco#chesterfield cigarettes#gregory peck#the 40s#40s movies#duel in the sun#david o. selznick

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

Notorious (1946, Alfred Hitchcock)

25/01/2024

Notorious is a 1946 film directed by Alfred Hitchcock.

In 2001 the American Film Institute placed it 38th on its list of the 100 best thrillers and horror films of all time, and in 2002 it placed 86th on its list of the 100 best romantic films of all time. In 2006 the film was chosen for preservation in the National Film Registry of the United States Library of Congress.

Miami, Florida.

The next morning the stranger reveals his identity to Alicia: he is the secret agent T. R. Devlin and she contacted her on behalf of the United States Government, to ask her to participate in a mission to Brazil, aimed at unmasking a pro-Nazi plot. Alicia, in love and eager to redeem her family's honor, decides to accept and leaves with him for Rio de Janeiro.

The agent discovers that the cellar is where the uranium ore in wine bottles is hidden.

However, he can no longer bear the torment that the role he has taken on causes him and asks to be transferred to Spain.

David O. Selznick sold the screenplay, actors, and director to RKO for eight hundred thousand dollars and fifty percent of the profits.

David O. Selznick, during the filming of Spellbound, had proposed to Hitchcock a story entitled The Song of the Dragon by John Taintor Foote. A previous film had already been made from the story, Convoy, directed in 1927 by Joseph C. Boyle and Lothar Mendes (the latter uncredited).

Hitchcock was joined on the screenplay by Ben Hecht, who also wrote the screenplay on the previous film Spellbound.

Ingrid Bergman plays the female protagonist; it was a choice strongly desired by Hitchcock himself. The actress had just played the role of Dr. Constance Peterson in Spellbound and it was therefore her second collaboration with the British director; with Hitchcock she will get another leading role playing Lady Henrietta in the film Under Capricorn.

Cary Grant plays the male protagonist, the policeman Devlin, also, after Suspicion, in his second collaboration with Hitchcock, with whom he would work twice more in the following decade: in North by Northwest and To Catch a Thief.

#Notorious#1946#alfred hitchcock#2001#american film institute#AFI's 100 Years 100 Thrills#2002#AFI's 100 Years 100 Passions#2006#national film registry#library of congress#united states#miami#florida#brazil#rio de janeiro#uranium#spain#David O. Selznick#spellbound#John Taintor Foote#convoy#Joseph C. Boyle#Lothar Mendes#ben hecht#ingrid bergman#Under Capricorn#cary grant#Suspicion#north by northwest

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

tony curtis as david o. selznick in moviola: the scarlett o'hara war

primetime emmy award nominee for outstanding lead actor in a limited series or movie

#tony curtis#david o. selznick#moviola#the scarlett o'hara war#lead actor in a limited series or movie#1980

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

'Thirteen Women' – Irene Dunne vs. Myrna Loy on Criterion Channel

Thirteen Women (1932) is a “Ten Little Indians”-style thriller set in a circle of sorority sisters whose planned reunion is marred with premonitions of death, murder, and suicide sent by a swami (C. Henry Gordon) whose astrological readings are all the rage in their society. Irene Dunne is Laura Stanhope, the good girl center of the sorority society, and Myrna Loy is Ursula Georgi, the exotic…

View On WordPress

#1932#C. Henry Gordon#Criterion Channel#David O. Selznick#DVD#Florence Eldridge#George Archainbaud#Irene Dunne#Jill Esmond#Kay Johnson#Mary Duncan#Myrna Loy#Ricardo Cortez#Thirteen Women#Tiffany Thayer#VOD

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Rebecca (1940) dir. Alfred Hitchcock

Rebecca | Alfred Hitchcock | 1940

#joan fontaine#judith anderson#rebecca#alfred hitchcock#rebecca 1940#daphne du maurier#mrs dewinter#mrs danvers#i dewinter#david o. selznick#1940s#classic film#classic movies#old hollywood

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

Reckless

If you just read a detailed synopsis of Victor Fleming’s RECKLESS (1935, TCM) you’d think producer David O. Selznick, who signed the original story Oliver Jeffries, was out of his mind. What starts as a romantic comedy with Jean Harlow, as a Broadway star, torn between sports promoter William Powell and feckless Southern millionaire Franchot Tone, turns into high drama with more than a few similarities to Libby Holman’s disastrous marriage to tobacco heir Zachary Smith Reynolds. If that shift in tone works at all (and it got past my nitpicking Aristotelian critical faculty), it’s thanks to the three stars, who are so engaging they could make almost anything work.

When the benefit at which she’s performing turns out to be a private show for Tone, Harlow agrees to go out with him, even though it means breaking dates with Powell, who’s been her friend and champion ever since he helped her transition from the carnival to the Great White Way. Touched by Tone’s need to find himself, Harlow marries him, and they go back to his family’s Southern plantation. Although she’s met with resistance from her father-in-law (Henry Stephenson), Harlow wins over most of Tone’s younger friends, including his ex-fiancee (Rosalind Russell). But Southern society rejects Tone, leading him to drink more and eventually commit suicide. Harlow has to face a battle over custody of their child, scandalous headlines and moralists trying to prevent her from returning to the stage.

The opening scenes have some very funny lines, and the dialog almost throughout has a crackle to it. Though the script was credited to P.J. Wolfson, other writers who contributed include Joseph L. Mankiewicz, Philip Barry, S.N. Behrman, Val Lewton and Norman Krasna. Whoever wrote the scene in which Powell tries to propose to Harlow accomplished the near impossible. The scene, beautifully and lightly played by Powell, helps the script switch from romantic comedy to melodrama as he transitions from joking to vulnerability.

Tone and Powell are particularly adept at putting the lines over, and by this point Harlow had learned to sell a punch line (though her big dramatic moments don’t always work; she wiggles her shoulders too much). Her star quality, the empathy she generates, makes you want her to come out on top. You also get May Robson, delightfully acerbic as Harlow’s grandmother, and Nat Pendleton and Ted Healy as Powell’s low-brow associates. Russell is natural and appealing, a far cry from the acting institution she would become in later years. Also on hand are Mickey Rooney as a lemonade stand owner fronted by Powell, a silent Leon Ames as Russell’s rebound husband and Margaret Dumont as a woman’s group member.

Then there are the musical numbers, added at the last minute when Louis B. Mayer decided the film needed something more (it didn’t work; this was a rare flop for Harlow). The big title number, by Jerome Kern and Oscar Hammerstein, is one of those extravaganzas that wouldn’t fit on any stage, with three sets on elevators and lightning quick changes for Harlow. It also has an absurd plot, with Harlow as a young woman who’s determined to “go places and look life in the face” and ends up shot after taking up with a bandit in a Mexican cantina. Harlow only delivers the patter in her songs, with the actual singing dubbed. And you can easily spot when they bring in a double to do the dancing (at one point Harlow moves behind a chorus group, and the dance double comes out the other side). After the death scene, Nina Mae McKinney comes out to sing a final chorus. Her part was originally larger, but her other two numbers were cut for fear she’d overshadow the star. And that’s Hollywood.

#romantic comedy#melodrama#victor fleming#mgm#david o. selznick#joseph l. mankiewicz#philip barry#s.n. behrman#norman krasna#val lewton#jean harlow#william powell#franchot tone#rosalind russell#henry stephenson#may robson#nat pendleton#ted healy#nina mae mckinney#margaret dumont#mickey rooney

1 note

·

View note

Text

need someone to fuck around with time to be with me. that’s how much i need to be needed

1 note

·

View note

Text

Gone with the Wind (1939), David O. Selznick

#gone with the wind#victor fleming#david o. selznick#cinematography#ernest haller#american cinema#scarlett o'hara#vivien leigh#1930s

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Remains to this day an all-time favorite. 🎬 💕

Rebecca | 1940 | USA

Director: Alfred Hitchcock

#rebecca#joan fontaine#laurence olivier#alfred hitchcock#david o. selznick#i dewinter#max dewinter#mrs danvers#classic film#old hollywood#classic movies#rebecca 1940#1940s#judith anderson

847 notes

·

View notes

Text

Elfújta a szél

Ma 85 éve mutatták be a filmet, ami a következő évben 10 Oscar-díjat nyert (és további 5 jelölést kapott). Olivia de Havilland (Melanie Hamilton) egy 1939-es felvételen (public domain) Az Elfújta a szél (Gone with the Wind) 1939-ben bemutatott színes amerikai film, ami Margaret Mitchell azonos című, Pulitzer-díjas regényéből készült. A történet az amerikai polgárháború idején és az azt követő…

View On WordPress

#Clark Gabl#David O. Selznick#Elfújta a szél#Gone with the Wind#Inni és élni hagyni#Margaret Mitchell#Olivia de Havilland#Oscar#Oscar-díj#Pulitzer-díj#Scarlett O`Hara#Tara Thornton#True Blood#Vivien Leigh

0 notes

Text

Constance Bennett and David O. Selznick entering Sardi’s in New York City in 1932.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Astaire & Rogers and the 1930s Aesthetic Part One: Flying Down to Rio

View On WordPress

#"Carioca"#"When Orchids Bloom in the Moonlight"#1930&039;s#42nd Street#Adele Astaire#Albert Chase McArthur#Arizona Biltmore#Cimarron#Claire Boothe Luce#Clark Gable#Dancing Lady#David O. Selznick#David Sarnoff#Dolores del Rio#Film Booking Office of America#Flying Down to Rio#Fred Astaire#Gene Raymond#Ginger Rogers#Gold Diggers of 1933#Hermes Pan#Joan Crawford#Joseph P. Kennedy#Keith-Albee-Orpheum Vaudeville Circuit#KEM Weber#Lela Rogers#M-G-M#Merian C. Cooper#R-K-O Radio Pictures#Raul Roulien

1 note

·

View note

Text

'A Star is Born' – the original Hollywood drama on Max

A Star is Born (1937) is the quintessential show-biz drama, a grand fable of Hollywood stardom done up with romantic glamour and tragic melodrama and a cynical undercurrent of caustic wit. Janet Gaynor is the improbably named Esther Blodgett, whose Cinderella story rise to movie star is counterbalanced by the fall of her husband, former matinee idol turned bitter alcoholic Norman Maine (Fredric…

#1937#A Star Is Born#Adolphe Menjou#Andy Devine#Blu-ray#David O. Selznick#Dorothy Parker#DVD#Fredric March#Guinn "Big Boy" Williams#Janet Gaynor#Lionel Stander#Max#May Robson#VOD#William Wellman

0 notes