#Dundee Makar

Text

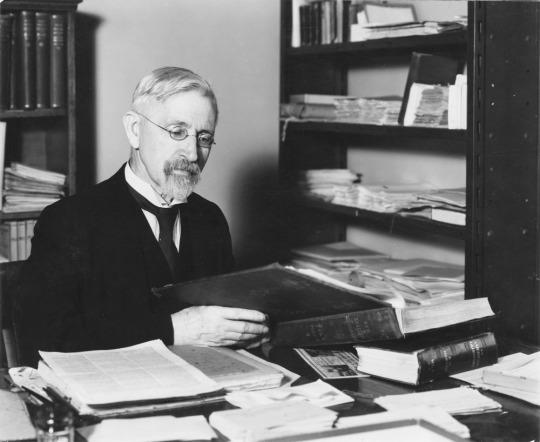

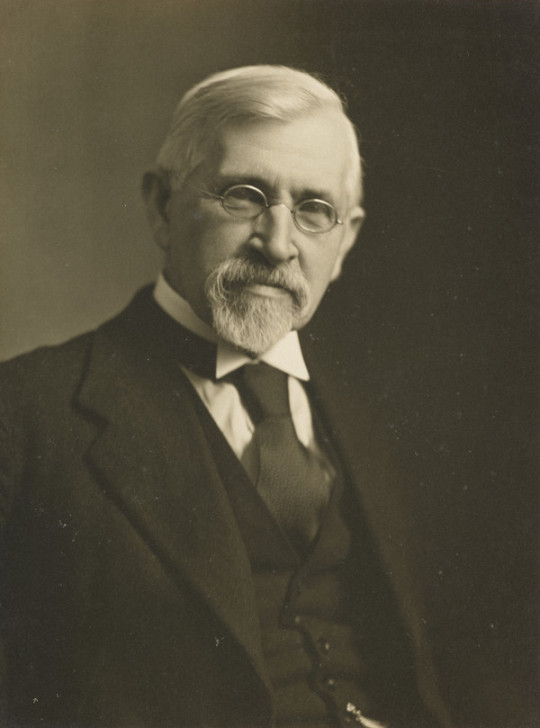

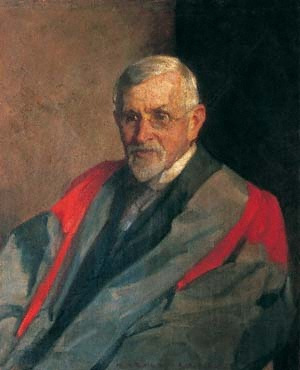

On 13th August 1867 William Craigie, the Scottish lexicographer, was born.

Isn’t it funny that us Scots started some of the most famous English establishments, like William Paterson who gave them The Bank of England, then Professor James Murray, the primary editor of the Oxford English Dictionary from 1879 until his death.

And we come to today’s subject, Sir William Craigie, a Scotsman from Dundee he was the third editor of the what is now commonly referred to as the ‘Oxford Dictionary’ or the ‘Oxford English Dictionary’(OED). He was editor of it for over 30 years.

It wasn’t always the English words for oor William though, born the youngest son of James Craigie and Christina Gow, William Craigie spent his formative years in his birth town of Dundee where, under the tutelage of his grandfather and older brother, he was introduced to Scottish Gaelic. This early taste of insular languages instilled in Craigie a passion that would endure for the rest of his lifetime. During his time studying at the West End Academy, Dundee, he began voraciously consuming the works of the early Scottish “Makars” – Robert Henryson, William Dunbar and Gavin Douglas – who would later become known among literary critics as the Scots Chaucerians for their role as the founding fathers of Scots literature.

As well as studying at St Andrews and Balliol College Oxford, where he learnt German, French, Danish and Icelandic, Craigie found himself at the University of Copenhagen where he added Medieval and Modern Icelandic to his ever-increasing list of languages.

Come 1897 Craigie’s lexicographical career began to take flight when the editorial board of the Philological Society’s New English Dictionary (soon to become the OED) were desperate to find a third Editor and Craigie’s name was put forward as a potential candidate. When Craigie received the fateful letter inviting him to work on the Dictionary on a trial basis; he was so keen, he even postponed his honeymoon with his newly wedded wife, Jessie Kinmond, to take up the position alongside the aforementioned James Murray, so you now had two Scots at the head of putting together the greatest collection of English words ever undertaken!

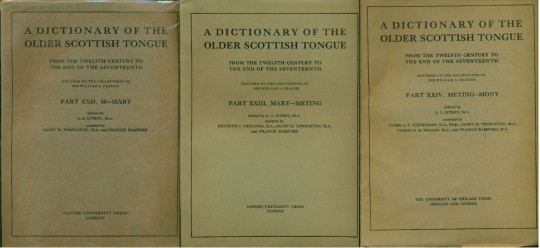

Let’s not forget, while he was employed full time on the English dictionary, Craigie continued with his other passion, A Dictionary of the Older Scottish Tongue (DOST) and in 1907, gave a lecture in Dundee on the action necessary to involve local people in collecting ‘Scots words, ballads, legends, and traditions still current’. The DOST was compiled over the following 8 decades and covers the language of Scotland from its earliest beginnings up to 1700. DOST has over 50,000 separate entries with over 581,000 illustrative quotations, and the 12 large printed volumes contain a total of 8,104 pages.

The print edition of the Oxford English Dictionary was once a constant companion to students, academics and writers across the English-speaking world. The Internet has now replaced it, but in it's day it was a priceless item, maybe not the OED, as it is known, but I think most households had a print edition dictionary, ours was used both for our homework from school, and many many games of scrabble, it certainly helped me understand the meanings of words and how they are spelled.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Great Slowing Down versus Poet MacDiarmid (3)

The Great Slowing Down versus Poet MacDiarmid (3)

3

The interiorising impulse is a normal part of most writers’ cycle of composition and publication, but it became stronger for me with my father’s death, after which I spent a couple of years darting off to any far-off place that invited me, blogging re the Dundee Makarship but not editing the posts into anything, and stringing tweets into absurd Informationist tales, which, probably sensibly,…

View On WordPress

#Charlie Chaplin#Chic Murray#Dundee Makar#Erin Farley#Hugh MacDiarmid#John Keats#Kirstie Blair#Lenin#Margaret Tait#Rainer Maria Rilke#T.S.Eliot#The Waste Land#William Donaldson#Xinjiang

0 notes

Text

Forensic Incoherence - TSP Edition

Ok I snapped and thought I’d get it out of my system. Also because I’m petty and I let things annoy me more than they should. I’d like to say first and foremost that people can and should still enjoy ‘The Spanish Princess’ as a fun tv show if they like, I’m simply pointing out that when it comes to Scotland, it bears even less resemblance to actual history than usual.

Also it is by no means the worst representation of Scotland! Which is saying something because it is NOT good. It’s about par for the course I’d say, with regards to the way mediaeval and early modern Scotland are portrayed in the media. Outlaw King and Outlander rise slightly above the mark but only just- i.e. they’re somewhat good pieces of historical media that are still inaccurate but are recognisably Scotland (and have some nice panning shots and good soundtracks). The middle point is probably inaccurate MQOS movies because they’re the least painful kind of inaccuracy that’s still kind of bad (but even their soundtracks don’t save them- I’m sorry John Barry). I will not say what the absolute worst piece of media is, I believe I have yet to encounter it and for that I am grateful. TSP is somewhere between the worst and the middle. The point is, most historical media about sixteenth century Scotland generally sucks, and this tv series is about the usual kind of bad. So I wouldn’t be so irritated with the people who made it if it weren’t for one or two individuals’ saying things about how ‘it really happened’.

With that in mind this is a good teachable moment. Usually there’s little point to a detailed analysis of where inaccuracy occurs in a tv show or movie- let’s face it, if they weren’t all a bit inaccurate they probably wouldn’t work too well on screen. However in this case it is such a classic example of the usual, standard depiction of Scottish history that it provides a great resource for showing where these things go wrong (which is everywhere).

So I thought I’d strip back a reasonably mediocre, not too terrible, not overly interesting piece and ask what we have left of sixteenth century Scotland after we’re finished.

I should point out I did not watch the first series of this show, and am basing this solely on the representation of the actual country in the first episode of season 2.

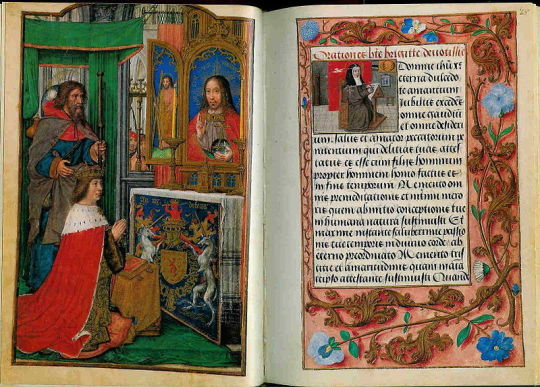

(Hours of James IV, source- wikimedia commons)

Now I’ve talked about James IV’s children in the first of the three scenes involving Scotland already. The last scene doesn’t have much meat in it except that I can confirm Margaret Tudor did lose multiple children and it WAS sad. So that leaves us with the second scene- the so-called ‘council’.

We open on your Usual Nonsense. Lots of men, many wearing tartan, with two famous surnames thrown in there for fun, arguing because The Clans Are Fighting Again.

I don’t have room to go into a whole analysis of the clan system and why our 21st century concept of ‘Highland clanship’ is not really applicable to many of the families at the centre of sixteenth century politics. Safe to say it is especially not applicable to the Red or Angus line of the Douglases (because yeah there were multiple different branches of that famous family), and only applicable to some of the branches of the Stewart family (and there were dozens of them, spread all over the country and operating in very different cultural worlds).

If Scottish politics worked the way that these writers seem to think it does- i.e. you support everyone who shares your family name against all others- then one wonders why James IV hasn’t taken the side of the Stewarts, seeing as that was his surname. Surnames and blood feud were very important in Scotland, both to traditional “clans” and to other families to don’t fit that bill, but they’re not everything. T.C. Smout famously said that “Highland society was based on kinship modified by feudalism, Lowland society on feudalism tempered by kinship.” Not everyone would agree wholly with that statement, but it’s a good starting point for beginners. Nonetheless, at no point should that confirm anyone’s belief that Scottish politics consisted basically of a bunch of clans with their own unique tartans and modern kilts running around the hills killing each other.

It’s also quite funny since James IV’s reign was one of the most (comparatively) peaceful in Scottish history between the Wars of Independence and the Union of the Crowns. He also had very little trouble controlling most of his subjects when it really mattered.

But I digress. We have Clans TM. They are Arguing. There are Douglases. There are Stewarts. It’s about as complicated as an Old Firm game, but less intellectual. This is supposed to be a serious political council.

(read more below)

Firstly, I can’t seem to find a good concise source, but based on a brief flip through the various charters, council decisions, accounts, and secondary sources on James IV’s reign I don’t think there were even any Douglases on the privy council in early 1511. Not that it’s a huge issue in itself- I don’t think that period dramas really put that much thought into representing the bewildering government reshuffles and that’s not really their main purpose anyway.

But what it leaves is this motley collection of characters, some of whom have historical figures’ names, and others who have vaguely plausible names that can’t be assigned to a specific person, and others who are unnamed set dressing but I get the feeling have probably been discreetly named something like Big Chief Hamish McTavish.

So among the few named characters you have George, Gavin, and “Angus” Douglas. These three are all presumably based on historical figures and it’s not too difficult to identify them, even if (like James IV’s children in another scene) they probably shouldn’t have been in the room.

“Angus” is presumably supposed to be Archibald Douglas, Margaret Tudor’s second husband, who became 6th Earl of Angus in 1513 (so two and a half years after this scene is set). “Angus Douglas” is not his name, in any way. It would be like me referring to Henry VIII as King England Tudor. Bit of a ridiculous mistake to make, if IMDB is not lying to me, since it implies that not only did the scriptwriters not even bother to use google, they didn’t even read the (somewhat inaccurate) novel that they based their show off.

Angus is not a common first name in the Douglas family during this period. In fact I don’t think I have ever heard of anyone called Angus Douglas from the sixteenth century or earlier. It was popular in some families from the west and the far north- mostly Gaelic-speaking families like the MacDonalds and the Mackays- but not really among the inhabitants of the Borders and Lowland east coast, which is where the Red Douglases held *most* (though not all) of their power. The earls of Angus took their title from a region in the east/north-east of the country, but they had a large power-base in the Borders and East Lothian too (not least the hulking red sandstone castle of Tantallon on the Berwickshire cliffs).

(The highlighted region is the modern version of Angus, between Dundee and Aberdeenshire. Nowadays, it has red-brown soil, old Pictish monuments, it grows wonderful raspberries and strawberries, and its main towns include Montrose, Arbroath (with its red sandstone abbey), Brechin, and Forfar. The urban and agricultural make-up would have been different in the sixteenth century though. The Borders meanwhile are pretty self-explanatory).

In 1511, Archibald’s grandfather, also Archibald, was still alive and held the title Earl of Angus. His eldest son George, Master of Angus (the younger Archibald’s father) was his heir apparent in 1511. Now the elderly 5th earl was still a wily character but he was old, and had also been held in custody on royal orders on the Isle of Bute until as recently as 1509, because the 5th earl and James IV had... well it was a complex relationship. We could perhaps assume that he was not able to travel easily- hence why his eldest son George, Master of Angus, seems to be the ‘George’ who is represented in that council scene. Somehow, I don’t see Archibald Junior being called his own grandfather’s title rather than his name when his father was in the room. George, Master of Angus, died at Flodden, which is why he did not succeed to his father’s earldom and the claim passed to his eldest son Archibald.

(There was another George Douglas worth mentioning, though he wouldn’t be in this scene- George Douglas of Pittendreich, Archibald’s younger- and, let’s be honest, smarter- brother. He was father to the Regent Morton).

The last is Gavin Douglas- probably the most interesting of the three to any literary scholars. He was the younger brother of the Master of Angus, and thus uncle to Archibald. He is one of the most important Scots poets- or makars- of James IV’s reign, and personally I would only place him beneath the great William Dunbar (the other big contenders, Henryson and Lindsay, respectively wrote most of their works before and after the adult reign of James IV). His works include the “Palice of Honour,” “King Hart”, and his greatest achievement the “Eneados”, completed c. 1513, which was the first full vernacular translation of the Roman poet Virgil’s Aeneid in either English or Scots. After Flodden, he became Bishop of Dunkeld, partly through Margaret Tudor’s influence, and didn’t find much time for writing any more poetry in the reign of James V, being consumed by political struggle. He died in exile in England in 1522.

Sixteenth century Scots had many complex and conflicting emotions and opinions, and one could severely hate and distrust England while remaining friends with certain Englishmen or respecting certain English customs. Nonetheless I find it a bit funny that Gavin Douglas is the one who is given the line ‘the English are the root of all our troubles’ since there was one thing that the English gave the world that no early sixteenth century Scots makar worth his salt could ever forget- and that was Geoffrey Chaucer (as well as his compatriots Lydgate and Gower). In his ‘Eneados’, Gavin Douglas himself described the great poet as “venerable Chaucer, principall poet but peir”. Which is not to say that such a character could not also have raged against the English on more than one occasion, this is merely to demonstrate that these three named men were rather more complex than the simplistic kilt-wearing, knife-wielding, drunk, Anglophobic, entirely uncultured stereotype we have on screen.

(And while I’m on the kilt and tartan thing- I literally JUST said that the Red Douglases were mostly centred on the Lowlands, and in particular the Borders. While it’s not impossible that they could have occasionally worn tartan, it’s not exactly everyday dress for them- unless you think it was also day dress for people in Carlisle as well. I notice Archibald Douglas himself isn’t really wearing any- perhaps this is to make him look more palatable. And don’t even get me started on the whole “the clans are fighting” thing).

(Look here’s a nice picture of Archibald Douglas, 6th Earl of Angus- admittedly when he was a bit older and had been in exile in England, but look! He’s dressed like other people in sixteenth century Europe! Nothing wrong with tartan but not your usual sixteenth century Borders earl gear.)

Funny thing is though, while the earls of Angus were undoubtedly important (and Gavin Douglas, being a university man, could act as an official), they’d lost their influence a bit by the end of the reign (again, the 5th Earl and James IV had a very layered relationship). Now, while lists of witnesses to charters do not necessarily reveal everything, if you were looking for powerful men who are likely to have been at the centre of government and on the king’s council in 1511 (and not just noblemen who were friends with the king but didn’t have government posts) I would look for some of the below first:

- Alexander Stewart, Archbishop of St Andrews and Chancellor of Scotland in 1511. He appears at the head of the witness list in almost every charter in the first half of 1511, and also signed off on the royal accounts. A young man, only about eighteen in 1511, who had studied under Patrick Paniter (see below), and then later had travelled on the continent and studies under humanists like Raphael Regius and Desiderius Erasmus. He was also James IV’s eldest son, though illegitimate- however although his promotion was undoubtedly nepotistic, there are signs that he would have made a pretty competent archbishop and he certainly actually did his job as chancellor. Although an archbishop (but never old enough to be fully consecrated or receive the revenues of his see), he followed his father to Flodden and died in battle. Erasmus famously eulogized him in his ‘Adages’, saying that:

“when a youth scarcely more than eighteen years old, his achievements in every department of learning were such as you would rightly admire in a grown man. Nor was it the case with him, as it is with so many others, that he had a natural gift for learning but was less disposed to good behaviour. He was shy by nature, but it was a shyness in which you could detect remarkable good sense.”

(A sketch from the Recueil d’Arras which is allegedly a copy of a painting of Alexander Stewart)

- William Elphinstone, Bishop of Aberdeen and Keeper of the Privy Seal in 1511. A man with many years of experience at the centre of government. After studying at Glasgow, Paris, and Orleans, he was made bishop of Ross and travelled to abroad on diplomatic missions. He had previously been High Chancellor of Scotland under James III, and even though he spent a small part of James IV’s early reign out in the cold he was soon brought back into the fold and played a leading role in government. Even though he was never chancellor again, he held the privy seal until the end of his career and often acted as de facto chancellor during the tenure of James IV’s younger brother the Duke of Ross (also an earlier Archbishop of St Andrews). William Elphinstone is also remembered for being a very active bishop in his diocese- he built a bridge over the River Dee, rebuilt part of the cathedral, and founded the University of Aberdeen, which received its papal bull in 1495. He organised the construction of King’s College, and the chapel built on his orders is still at the centre of the university’s campus today. He also sponsored the publication of the Aberdeen Breviary, on Scotland’s first printing press. He is supposed to have been against the invasion of England in 1513, but after the king’s death, Elphinstone was seen as the natural choice to succeed Alexander Stewart in the archdiocese of St Andrews, despite his age. He died in late 1514.

Andrew Stewart, Bishop of Caithness, Treasurer in 1511 takes third place on a lot of charters. Less can be said about him than the first two, though his rise at the centre of government really took off around 1509. He was Treasurer in 1511. It is not clear which branch of the Stewarts he hailed from, but it may have been the Stewarts of Lorne, which would have made him a distant cousin of the king and a slightly closer cousin of the king’s last known mistress, Agnes Stewart. Things are not made any simpler by the fact that, after his death, the next bishop of Caithness was ALSO called Andrew Stewart, and this one was an older half-brother of the Duke of Albany and a son of James IV’s uncle. The main takeaway- there are lots of Stewarts in Scotland, including the Royal Stewarts, and too many branches of the family for any simplistic tale of “clan” rivalry with the Red Douglases to be at all compelling or make sense. It is also worth noting that until 1469, Caithness would have been the most northerly diocese in the kingdom- whether Andrew spent more time there or at the centre of government is unclear.

(A rare contemporary painting of William Elphinstone, bishop of Aberdeen and Keeper of the Privy Seal)

Archibald Campbell, 2nd Earl of Argyll and Master of the Household in 1511- This post was less explicitly a ‘government’ post but the royal household still had an important political role. Even without this government post, though, the earl of Argyll was an important man. One of the two ‘new’ earldoms created in the reign of James II, the earls of Argyll were sometimes seen as royal ‘policemen’ in the West Highlands and islands. Their earldom was named after the large region on the west coast of the same name, cut up by sea-lochs and mountains. However they often had their own agenda and could exercise some independent policies in the Isles and northern Ireland. The earls of Argyll were usually the chiefs of Clan Campbell (look! An actual Highland clan for once!), including its many cadet branches. Clan Campbell has a very black reputation now (with some justification), though it is worth mentioning that in the sixteenth century they were also patrons of Gaelic culture and poetry, and frequently intermarried with the families they were meant to be ‘policing’. Notably, Archibald’s sister had been married to Angus Og (MacDonald), son (and supplanter) of the last “official” Lord of the Isles, but after Angus Og’s murder in the 1490s, the then earl of Argyll kept Angus’ son (his own grandson) Domnall in custody on behalf of the Crown- at least until he escaped and started causing all kinds of trouble in the early 1500s. Archibald Campbell, also called Gillespie, was the second earl of Argyll and rather less influential than his father had been, but he was still one of the most important laymen involved in government in the latter part of James IV’s reign. He died at Flodden in 1513.

Matthew Stewart, 2nd Earl of Lennox and Lord Darnley- Appears as a witness in many charters and is mentioned at council meetings on occasion. Yet another branch of the Stewart family- I must reiterate, a shared surname, though important, did not necessarily mean that everyone shared the same rivalries or stuck together through thick and thin. The Lennox is a region at the south-western edge of the Highlands, and north of the River Clyde- it is mostly centred around Loch Lomond. The Stewarts of Darnley had also had close links with France and in particular the Garde Écossaise for over a century. This earl of Lennox’s father led a short rebellion during the early years of James IV’s reign, but most of that was smoothed over in the end. In all honesty I don’t know that much about Matthew personally, except that he pops up a lot in government and court records (and there was also a very delicate case that came before the council in 1508 involving his daughter). I will need to look into him further. He died at Flodden- his son was the earl of Lennox who then died at Linlithgow Bridge in 1526, and his grandson married Margaret Douglas, daughter of the earl of Angus, and was the father of the infamous Lord Darnley who married Mary I.

Alexander Hume, 3rd Lord Hume and Great Chamberlain of Scotland in 1511. In the early sixteenth century, the Humes were borderers par excellence. Lord Hume was Warden of the East and Middle Marches, and had a great many kinsmen and friends (and a fair few enemies) throughout the borders counties. His great -grandfather and, especially, his father had also carved out a role for themselves at the centre of government. In the first couple of years of James IV’s reign, the Humes and even more so their neighbours the Hepburns (family of the earls of Bothwell) were practically running the show- this may have been one of the main causes of the earl of Lennox’s rebellion. In 1506 Alexander succeeded his father as 3rd Lord Hume and Great Chamberlain (less of an active administrative role by this point, but it still entitled the holder to access the centre of government and the royal household). He fought at Flodden but escaped- unfortunately for the Humes, rumours later circulated that they were partly responsible for the king’s death in the battle, and indeed James IV’s son the earl of Moray is supposed to have accused Hume of this in later years. Hume was one of the men who supported the appointment of the Duke of Albany as governor in 1515, after Margaret Tudor’s marriage to the Earl of Angus, but he very quickly grew dissatisfied with the duke, and by Christmas of the same year he had crossed the Border to join Margaret in Morpeth. After another few months of shenanigans in the Borders, Hume and his brother were captured by the Duke of Albany and executed in 1516- their heads were displayed above the Tolbooth in Edinburgh. This resulted in even more drama but I’m getting off topic and I think enough has been said on Lord Hume to give you an idea of his, um, colourful character. He is *supposed* to have had an affair with the second wife of the 5th Earl of Angus, Katherine Stirling, and was later the second husband of James IV’s last mistress Agnes Stewart, Countess of Bothwell.

(Restored windows in Stirling Castle Great Hall, the 20th century glass bearing the coats of arms of earls from the reign of James IV. The hall dates from around 1503 and was restored in the 1960s to look like it may have done in James IV’s time. It’s bright yellow and gorgeous and I’m furious it’s never used in anything).

Andrew Gray, Lord Gray and Justiciar in 1511- A lord of parliament like Hume, but with a less committed following, whose main interests lay in Angus (the region). Andrew Gray was one of the men who backed James IV in his rebellion against his father in 1488. Indeed, late sixteenth century legend has it that he was the one responsible for James III’s death- either arranging his murder in the mill at Bannockburn or carrying it out himself. However he acted as a loyal servant of the Crown until the end of his life, and as the justiciar he would have accompanied the king and other important nobles on justice ayres across the kingdom (and held some of his own). Traditionally, there had been two justiciars in Scotland- one for Scotia, north of the Forth, and one for south of the Forth (usually identified with Lothian- there was a third sometimes for Galloway as well). In the 1490s, Lord Drummond and the Earl of Huntly had also acted as justiciars at various points, but from around 1501 Lord Gray appears to have been the only justiciar. He died in early 1513.

Master Gavin Dunbar, Archdeacon of St Andrews and Clerk Register in 1511. Not to be confused with either of the poets Gavin Douglas or William Dunbar, nor with his nephew, Gavin Dunbar, Archbishop of Glasgow. This Gavin Dunbar was a graduate of the University of St Andrews and had travelled to France in at least one embassy in 1507. Technically, in 1511, Dunbar was clerk of the rolls, clerk register, and clerk of council- which is a lot of writing (if we assume he did it all himself, which I doubt). In 1518, Dunbar succeeded to William Elphinstone’s old diocese of Aberdeen and showed a decent amount of interest in the diocese. He undertook an extensive rebuilding programme at St Machar’s Cathedral and provided the nave with the wonderful heraldic ceiling that can still be seen today.

Master Patrick Paniter, Secretary to the King (among other things) in 1511. A very interesting individual. Paniter’s family were from the area around Montrose, in Angus, and he attended university at the College of Montaigu in Paris (as did many of his compatriots, including the contemporary theologian John Mair). He was clearly a bright spark since upon his return to Scotland he seems to have been appointed tutor to James IV’s young son Alexander and the two had a good relationship, with Paniter writing to the young archbishop as ‘half his soul’ and Alexander in turn keeping in touch with his ‘dear teacher’ while on the continent. By that time though, Patrick had moved onto bigger things, since the king appointed him royal secretary some time around 1505. Eventually Paniter became one of James IV’s most influential servants- in 1513, the English Ambassador Dr Nicholas West described the secretary as the man “which doothe all with his maister”. Of course Paniter enriched himself quite a bit too, becoming, among other things, archdeacon and chancellor of Dunkeld, deacon of Moray, rector of Tannadice, and Abbot of Cambuskenneth and, controversially, James IV also attempted to appoint him as preceptor of Torphicen. Paniter helped to direct the artillery at Flodden but unlike both his patron and former pupil, he survived the battle. He is also *reputed* to have been the father of David Paniter, bishop of Ross, by King James IV’s cousin Margaret Crichton.

The men whose careers I’ve outlined above all witnessed the majority of royal charters issued under the great seal in the first half of 1511 (by modern dating). A few others also appeared frequently- for example, Robert Colville of Ochiltree, John Hepburn the Prior of St Andrews, and George Crichton, Abbot of Holyrood. Obviously the make-up of the council changed frequently too. Equally though charters are not necessarily the only or best indication of who would have been part of the king’s ‘council’ and there are other officials and nobles whom we know were close to the king but rarely appear on these, either due to the date range or just their own status- Andrew Forman, bishop of Moray; the 1st earl of Bothwell (before his death); the 5th earl of Angus (in the 1490s anyway- I told you it was a complex relationship); John, Lord Drummond (especially in the 1490s), and others.

But why did I bother giving those long biographies? Well partly to demonstrate the complexity of individual stories in sixteenth century Scottish politics and that they did do important and interesting things. Also since several of these men held opposing political views and family interests, but were usually expected to cooperate at the centre of government, it underlines the point that sixteenth century Scottish politics was a bit more complex than ‘The Clans Are Fighting’. And also this is partly to show that we DO actually have this info at our disposal. Most tv shows and films just choose not to use it.

But the real reason for this long rant was mostly so I could ask, given the info I’ve provided above, WHO THE HELL IS THIS SUPPOSED TO BE:

It’s a bad picture, I know and again, nothing against the actor who seems to be having a lot of fun with the role. But other than James IV, Margaret, and the three Douglases (one of whom has the wrong name and they all have the wrong clothes and also none of them should have been there), this is the only named character in that scene. And I cannot for the life of me work out who he is supposed to be.

He’s given the name Alexander Stewart. As we have seen, there was certainly an Alexander Stewart on the king’s council in 1511- the king’s son who was born c. 1493 and was also Archbishop of St Andrews. Now this this man very much NOT younger than Margaret Tudor, and very unlike the boy Erasmus described, and even though that Alexander died fighting in battle I’m not sure he would have spent most of his days brandishing daggers and yelling abuse at the Douglases in council meetings. He is also probably not our man because as I discussed here, I think the archbishop’s supposed to be counted among James IV’s children in that other scene where this tv series wrongly implies that Margaret Tudor played nursemaid to all of James’ children (again, not one of those kids should have been in the room and it’s really weird that none of them seem to have aged even though two of them were probably older than Mary Tudor).

So who is he? There were definitely other Alexander Stewarts who were both associated with the royal household and who were kicking about sixteenth century Scotland more generally. One was in fact the half-brother of the Duke of Albany- but he really doesn’t seem to have played any role in government, and mostly he appears when his expenses were met by his cousin the king, presumably out of familial responsibility (see also the king’s other probable cousins Christopher, the Danish page, and Margaret Crichton). Another one was Alexander Stewart, Earl of Buchan, a more distant cousin of the king (he was the grandson of Joan Beaufort), but he was dead by 1511 and his son was called John- meanwhile his half-sister Agnes, the king’s mistress, was enjoying the profits of the earldom. In character he seems to come across more like an earlier earl of Buchan, that infamous Alexander Stewart who got the nickname ‘The Wolf of Badenoch’- but he died over a century before 1511. There are probably a couple of other Alexander Stewarts I’ve missed out- it’s a popular name- but none I can think of who would have had any sort of reason to be on the king’s council.

Also worth mentioning I’m not sure what he means when he accuses the Douglases of ransacking his family’s ‘Lowland lands’. That’s just so confusing I won’t even get into it.

ANYWAY there was a point to all this ranting. As I said above, people should absolutely enjoy this show if they want to. However, two things may be said- firstly that if a show is already fairly inaccurate about English history, I am always willing to bet that they have been 200% more inaccurate about Scotland- to the extent that it’s not even inaccuracy any more, it’s just a completely different world and story.

Secondly, when the producers or whoever (and no disrespect to them necessarily except when they say this) claim that they did their research and say stuff like "we are totally with her story, we're up in Scotland, we're sort of Spanish Princess meets Outlander" I would like to remind everyone that not only is this waaaay less accurate than even Outlander could manage:

- Probably none of the kids in the first scene should have been there

- Probably none of the men in the council scene should have been there (except James, obviously)

- The costumes are the same nonsense as usual.

- There were only five named historical figures and somehow they still managed to balls up one of the names (again, Angus Douglas??? How did they even manage to mess that one up??)

- The sixth named figure is a completely made up individual with a vaguely plausible name who appears to serve no other purpose than to get stabby and foul-mouthed and show that The Clans(TM), as they put it, Are Fighting Again.

- It’s heavily implied that absolutely nobody involved in the production has ever looked at a map of Scotland properly, or tried to work out where any of these guys come from. Which is amazing given it’s literally attached to the map of England. Essentially, the land and regions matter in Scottish history and it’s one of the biggest things that period dramas misunderstand or simplify.

- As usual the architecture is slightly off, though it could be worse. Despite the claim that ‘we’re up in Scotland’, suffers from the usual feeling that actually no camera crew made it any further north than Alnwick (though the CGI Warwick-Edinburgh thing kind of worked.).

- Everyone is a classic stereotype of the Barbarian Uncultured Scot and the only sop thrown is the bit with James and the teeth.

- The above thus implies that the creators have not considered that Scotland could ever have anything of any cultural value, such as a talented poet they are literally showing on screen or a bunch of bishops and other churchmen they aren’t. Which is just European Renaissance stuff, and not even getting into the highly impressive cultural world of Gaelic Scotland and Ireland.

- Everyone Is Sexist Except the English (for god’s sake, it’s the 16th century)

- Person wanders around yelling that they are the king/queen and expects this to work. No.

- Bruce and Wallace are (accurately) mentioned a lot but it’s probably more because that’s the only people the writers have heard of, rather than any nod to 16th century literary and historical tradition. No James Douglas or Thomas the Rhymer or St Margaret is expected to make an appearance.

- Incredibly evident that nobody has opened a book on the reign of James IV or even one of those dodgy biographies of Margaret Tudor. I’m not even entirely convinced that they read Gregory’s novel, which is supposed to be their source material.

So what do we actually have?

- James IV’s interest in medicine and alchemy and other proto-sciences is given a nod with the teeth thing

- We know there were black musicians at James IV’s court and that was shown.

- It is implied Margaret Tudor has lost babies. This is true. However there are still allegedly two alive so the maths doesn’t add up.

- Some modern Scottish accents, one done by a Northern Irishman.

- A handful of historical figures’ names scattered around willy-nilly (one of them incorrect).

The overall point is, once again, if you thought the inaccuracy about English history was bad, there isn’t even any inaccuracy in the Scottish stuff, because it’s not even sixteenth century Scotland any more. And that wouldn’t be an issue if the creators didn’t keep going on about how this is what really happened.

(King’s College, University of Aberdeen, with Bishop Elphinstone’s chapel to the right. On other sides of the chapel, the coats of arms displayed include those of James IV, Margaret Tudor, and Alexander Stewart, Archbishop of St Andrews- I think the Duke of Ross might be there too, can’t remember)

- Most of my sources for this included Norman McDougall’s biography of James IV, Macfarlane’s biography of Elphinstone, good general overviews, and a lot of primary sources- especially the register of the Great Seal. Also general knowledge about Scotland because, you know, I’m from there. HOWEVER if anyone wants a source for a specific detail I should be able to find that reasonably easily. Just let me know.

#Scotland#Scottish history#British history#Margaret Tudor#period drama#didn't know what to tag as sorry

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Threshold

Jackie Kay - on language and communication, story-telling and shared humanity

Let’s blether about doors.

Revolving doors and sliding doors;

Half-opened, half-closed:

The door with your name on it,

The heavy one - hard to open.

The one you walked out when your heart was broken,

The one you walked in as you came to your profession

(And the tiny door when you made your confession)

The school door at the end of a lesson,

(Yes, Shut the door in Gaelic is duin an doras!)

The wee door on your doll’s House, or

Ibsen’s Nora’s door, or Chekhov’s Three Sisters’

Doors imagined by writers the world over - Proust.

And the chickens coming home to roost!

Or Chris Guthrie’s open heart at the end of Sunset Song

Or the step left when the house is gone, the haw.

The door to the stable, bolted after the horse left,

Not Tam O’Shanter’s tail-less horse!

The one that shut suddenly behind you

Banged by a violent wind,

The painted red door code for asylum seeker,

The X that says Plague or Passover

The one turned into a boat to cross the ever-widening waters.

The North seas and the Aegean, reminders

Of the people cleared off their land, out their crofts

To whom the sea was their threshold - on, off.

Take the big key and open the door to the living, breathing past

The one you enliven over and over,

To the ship’s port, or the house of the welder;

To the library door of Donald Dewar.

Then picture yourself on the threshold,

The exact moment when you might begin again,

A new sitting, new keys jingle possibilities.

Hope comes with a tiny Greyfriar’s Bobby key ring.

Then come through the door to this Parliament, new session!

Pass round the revolving door (change in the revolutions,

In 360 degrees) – Take in the mirrored opposites:

The Dutch Gables, the cross step Gables…

Here - rising out of the sloping base of Arthur’s Seat

Straight into this City, a city that must also speak

For the banks and the braes, munros, cairns, bothies

Songs, art, poems, art, stories,

(And don’t forget the ceilidhs – who doesnie love a ceilidh? Heuch!)

A city that remembers the fiddlers of Shetland and Orkney

The folk of Colonsay, Bute, and Tiree

The Inner and Outer Hebrides, the glens and the Bens

The trees and the rivers and the burns and the lochs and the sea lochs

(And Nessie!)

The Granite City and Dumfries and Galloway

The Dear green place and Dundee…

Across the stars and the galaxy,

The night sky’s tiny keys, the hail clanjamfarie!

Find here what you are looking for:

Democracy in its infancy: guard her

Like you would a small daughter

And keep the door wide open, not just ajar,

And say, in any language you please, welcome, welcome

To the world’s refugees.

Scotland’s changing faces – look at me!!

Whose birth mother walked through the door

Of a mother and baby home here

And walked out of Elsie Inglis hospital without me.

My Makar, her daughter, Makar

Of Ferlie Leed and gallus tongues.

And this is my country says the fisherwoman from Jura.

Mine too says the child from Canna and Iona.

Mine too say the Brain family.

And mine! says the man from the Polish deli

And mine said the brave and beautiful Asid Shah.

Me too said the Black Scots and the red Scots

Said William Wallace and Mary Queen of Scots.

Said both the Roberts and Muriel Spark.

Said Emile Sande and Arthur Wharton.

Said Ali Smith and Edwin Morgan.

Said Liz Lochhead, Norman and Sorley

And mine said the Syrian refugee.

Here we are in this building of pure poetry

On this July morning in front of her Majesty.

Good Day Ma’am, Ma’am Good Day.

Good morning John and Helen Kay -

Great believers in democracy.

And in gieing it laldy.

Our strength is our difference.

Dinny fear it. Dinny caw canny.

歡迎 (Cantonese)

One language is never enough

Gbegbɔgblɔ ɖeka sese menyo tututu o (Ewe)

Welcome

Witamy (Polish)

It takes more than one language to tell a story

एक कहानी सुनाने के लिए, एक से अधिक भाषाएं लगती हैं (Hindi)

Welcome

ਜੀ ਆਇਆ ਨੂੰ (Punjabi)

One language is never enough

Une seule langue n’est jamais suffisante (French)

Welcome

Fàilte (Gaelic)

It takes more than one tongue to tell a story

It taks mair nor ae tongue tae crack (Doric)

Welcome

مرحبا (Syrian)

Welcome

Nnọọ! (Igbo)

Welcome

Wilkommen (German)

Welcome

Benvenuti (Italian)

It takes more than one language to tell a story

ہانی بتانے کے لئے ایک سے زیادہ زبان لیتا ہے (Urdu)

Lleva màs de un idioma contar una historia,

Bienvenidos

Un idioma nunca es suficiente

Bienvenidos (Spanish)

Eine Geschichte braucht mehr als eine Sprache.

Willkommen

Eine Sprache reicht nicht

Willkommen. (German)

خوش آمدید۔

ایک زبان کبھی کافی نہیں ہوتی۔

کہانی سنانے کے لیے ایک سے ذیادہ زبان چاہیے ہوتی ہے۔ (Urdu)

Ci vuole più di una lingua per raccontare una storia.

Benvenuto.

Una sola lingua non è mai abbastanza.

Benvenuto. (Italian)

Cal més d'un idioma per explicar una història.

Benvingudes.

Un idioma mai no és prou.

Benvingudes. (Catalan)

Ne samo jedan jezik je dovoljno je ispricati pricu.

Dobrodošli.

Jedan jezik nikad nije dovoljno.

Dobrodošli. (Serbian)

Щоб розповісти історію потрібно більше, ніж одна мова

Ласкаво просимо

Однієї мови ніколи не достатньо

Ласкаво просимо (Ukranian)

Több nyelven mondd el a mesét.

Üdvözlégy.

Egy nyelv sosem elég.

Üdvözlégy. (Hungarian)

Ai nevoie de mai mult de o limbă pentru a spune o poveste.

Bun venit.

O singură limbă nu este niciodată de ajuns.

Bun venit. (Romanian)

Nutamk atelk aq newte situm wjit a'tukwaqan.

Pjila'si.

Newte situn mu tepianuk.

Pjila'si.

Det behövs mer än ett språk för att berätta en historia.

Välkomna.

Ett språk räcker aldrig.

Välkomna. (Swedish)

Příběh potřebuje více než jeden jazyk

Vitejte

Nestačí mít jediný jazyk

Vitejte (Czech)

Потребни се повеќе јазици за да се раскаже приказна,

Добредојдовте

Еден јазик никогаш не е доволен

Добредојдовте (Macedonian)

Potrebno je više jezika da bi se ispričala priča

Dobrodošli

Jedan jezik nikad nije dovoljan

Dobrodošli (Montenegrin)

ஒரு கதை சொல்ல மேற்பட்ட தாய்மொழி எடுக்கும்

நல்வரவு

ஒரு மொழி போதுமானதாக இருக்காது

நல்வரவு (Tamil)

Več jezikov je potrebnih, da poveš zgodbo

Dobrodošli

En sam jezik ni nikoli dovolj

Dobrodošli (Slovene)

Ганц хэлээр тавтай морил

гэх нь хэзээ ч хангалтгүй

бөгөөд олон хэлээр өгүүлэн

ярилцах нь илүү нээлттэй (Mongolian)

Mae angen mwy nag un tafod i gyfleu stori

Croeso

Mae un iaith byth yn ddigon

Croeso (Welsh)

Een taal is nooit genoeg

Welkom

Er is meer dan een taal nodig om een verhaal te vertellen

Welkom (Dutch)

É preciso mais de uma língua para se contar uma história

Bem vindo

Uma língua nunca é o suficiente

Bem vindo (Brazilian Portuguese)

Inachukua zaidi kuliko lugha moja tu kutoa.

Karibu.

Hadithimoja ni kamwe ya kutosha.

Karibu. (Swahili)

Precísase mais dunha lingua para contar unha historia

Benvido

Unha lingua nunca é abondo

Benvido (Galician)

Go tsaá dipuô tse dintsi go bolela polelô,

O amogetswe

Puô ê nnwe ga e nke e lekana,

O amogetswe. (Tswana)

Potrebno je više od jednog jezika kako bi se ispričala priča.

Dobrodošao

Jedan jezik nikada nije dovoljan

Dobrodošao (Croatian)

Dit vat meer as een taal om ‘n verhaal te vertel

Welkom

Een taal is nooit genoeg nie

Welkom (Africaans)

Tarinan kertomiseen tarvitaan enemmän kuin yksi kieli,

Tervetuloa

Yksi kieli ei ikinä riitä

Tervetuloa (Finnish)

Potrzeba więcej niż jednego języka by opowiedzieć historię

Witaj

Jeden język nigdy nie wystarczy

Witaj (Polish)

Der skal mere end et sprog til at fortælle en historie

Velkommen

Et sprog er aldrig nok

Velkommen (Danish)

Нужен е повече от един език, за да се разкаже една история

Добре дошли

Никога не е достатъчен само един език.

Добре дошли (Bulgarian)

يحتاج الأمر أكثر من لغة واحدة لتحكي قصة

مرحباً

لا تكفي لغة واحدة ابداً

مرحباً (Arabic)

Nuk mjafton vetëm një gjuhë për të rrëfyer një tregim.

Mirësevjen

Një gjuhë nuk mjafton asnjëherë.

Mirësevjen (Albanian)

Il faut plus qu'une langue pour raconter une histoire

Bienvenue

Une langue n'est jamais assez

Bienvenue (French)

צריך יותר משפה אחת כדי לספר סיפור

ברוך הבא

שפה אחת לעולם אינה די

ברוכה הבאה (Hebrew)

Zimatengera chilankhulo choposa chimodzi kuti ufotokoze nkhani.

Takulandirani.

Chilankhulo chimodzi ndi chosakwanila.

Takulandirani. (Chichewa)

Hizkuntza bakarra baino gehiago behar dira istorio bat kontatzeko,

Ongi etorri

Hizkuntza bat inoiz ez da aski

Ongi etorri. (Basque)

物語を伝えるのは複数の言語がいります。

歓迎。

一つの言語は決して十分ではありません。

ようこそ。(Japanese)

Butuh lebih dari satu bahasa untuk menceritakan sebuah kisah

Memakai

Satu bahasa tidak pernah cukup

Memakai (Indonesian)

Чтобы рассказать историю, надо больше одного языка

Добро пожаловать

Одного языка никогда не достаточно

Добро пожаловать (Russian)

Om in ferhaal te fertellen hast mear as ien taal noadich,

Wolkom

Ien taal is noait genôch

Wolkom (Frisian)

Dobra Dosli

Jedan jezik nikad nosta

Dobra Dosli (Bosnian)

Benvegut

Una lenga basta pas jamai

Cal mai d'una lenga per contar una istòria

Benvegut (Occitan)

Tha ea 'toirt barrachd air aon chànan a dh' innseadh sgeulachd

Fàilte

'S e aon chànan riamh gu leòr

Fàilte (Gaelic)

It's ever so ard to tell a story wiv one langwidge

cummin and av a cuppa

One langwidge ain't nuffink like innuf

cummin and av a cuppa (South West London)

It taks mare than wan type o patter tae tell a yarn.

Mak yersel at hame.

Wan patter is naer enough.

Mak yersel at hame. (Glaswegian)

Welcome.

C’mon ben the living room.

Come join our brilliant gathering.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Death to the Cringe

From this article by Kenny Farquharson in the times.

http://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/2f6db088-d391-11e6-b721-fbd88801f92d I thought it was heading for extinction, like mullet haircuts or smallpox. Good riddance, was my view. It was a symptom of a less enlightened age. Modern life had overtaken it and rendered it obsolete.

I am talking about the Scottish cringe. Was there ever a more ridiculous affliction? The symptoms were easy to spot: an involuntary shudder at the sound of a glottal stop; an onset of the vapours when confronted with a fluttering Saltire; a pursing of the lips at any manifestation of Scottish working class culture.

If you had asked me about the cringe a decade ago I would have told you with confidence that its days were numbered. Scotland, with its shiny new parliament, had thrown off its inferiority complex. The clammy hand of uptight, middle class, Presbyterian respectability had been prised from its throat.

Scottish popular culture, as expressed through music, art, video games and literature, was in rude health. Not only was Scotland more cosmopolitan and multicultural, it was also more authentically itself. We were at ease with being Scottish.

That was then. Now I am not so sure. This week’s reaction to a simple 14-line poem has dented my confidence. Written in Scots by Jackie Kay, the Scottish makar, it was commissioned for the “baby box” scheme being piloted by the Scottish government. This idea, borrowed from Finland, gives the parents of every newborn a box full of clothes and babycare essentials, contained in a cardboard box that doubles as a rudimentary crib. Every box also contains Kay’s poem: O ma darlin wee one At last you are here in the wurld And wi’ aa your wisdom Your een bricht as the stars … A bit sappy for some cynical tastes, maybe. But if you can’t gush a little at the birth of a baby, when can you? Yet the reaction was extraordinary.

A small number of people were worried that the poem’s upbeat optimism might upset mums with postnatal depression. But a majority of the objections focused on the fact that it was written in Scots. “Ridiculous nationalist bullshit,” wrote one commenter on Mumsnet. “They didn’t need to decide to write it in Scots. But they have, for political reasons.”

Others on the thread were no more forgiving. “That poem is shite. It’s too Scottish for the sake of being Scottish.” Another wrote: “They do know that hardly anyone in Scotland actually speaks like that?” Another mum asked: “Do you actually believe that choosing to promote Scots after years of suppressing it, other than for picturesque national activities like Burns night, is anything other than a political decision?” The cringe, like a nasty rash, is back. Far from being extinct it is enjoying a new lease of life.

Doing down the Scots language has a long and inauspicious history. During the 17th century the introduction of universal schooling in Scotland was accompanied by a stipulation that children should be taught in English.

There were sensible reasons for this. If Scotland wanted to play a full part in the world, intellectually and commercially, it had to speak English. Yet too many teachers saw this as a zero-sum game and beat the use of native Scots out of their young charges.

As reflected in novels such as William McIlvanney’s Docherty, punishment in school for use of the Scots language would last into the second half of the 20th century.

When I was in my teens in Dundee in the 1970s there was a woman who lived near our house who made a good living as an “elocution teacher”. Some working class parents, afflicted with the cringe, paid her to flatten their children’s vowels, to fill in the glo'al stops, to eradicate the Scots vocabulary, in the belief that this was necessary to get ahead.

What a way to start out in life: being told that the way you express yourself is illegitimate, that the very words you use to describe your world are proof of your inferiority.

Now the denigration of Scots has another motivation, and it is political. The return of the cringe is a symptom of the kind of society we have become since the independence referendum of 2014.

The extent to which we are now two tribes rather than one nation has, on occasion, been overblown. Yet there is no denying that for a minority of Scots on both sides, the independence question has come to define who they are.

Arguments about this little poem are only one example of how deforming this can be. The Unionists who complain about Kay’s poem are guilty of a basic category error. They see any expression of national identity or national difference as evidence of political nationalism.

So a new ScotRail livery that includes a Saltire is part of a Nationalist plot. The use of the Scots language is an attempt to undermine support for the UK. And a simple poem about a newborn is SNP state indoctrination. This is facile. Worse, it is politically counterproductive.

To surrender all the characteristics of Scottishness to the SNP, to want only a deracinated Scotland indistinguishable from Surrey, is to admit defeat in the debate about Scotland’s future. The cringe is the SNP’s most effective recruiting sergeant, and always has been.

Usually I try to be relaxed about people holding views different to my own. Not on this occasion. The Scottish cringe is a cancer in the political, cultural and social life of the nation. Its influence is pernicious. It is a wet blanket thrown over the lives of young working-class Scots. Death to the cringe.

100 notes

·

View notes

Text

THIS - An exhibition celebrating the life and work of Jim Stewart

THIS – An exhibition celebrating the life and work of Jim Stewart

From the Curator of Museum Services at the University of Dundee : THISAn exhibition celebrating the life and work of Jim Stewart (1952-2016) Tower Foyer Gallery, University of Dundee Jim Stewart was an inspirational and much-admired author and teacher described by Dundee’s Makar, W N Herbert, as “one of the most significant poets of the last decade”. James Clark Quinn Stewart was born in…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

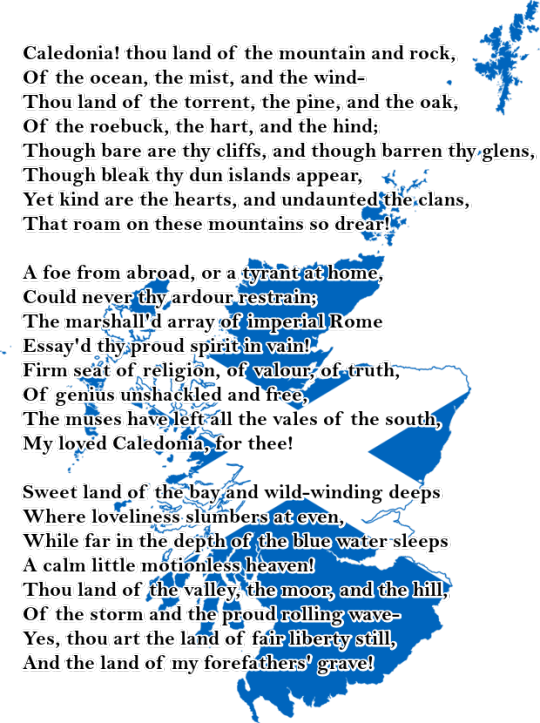

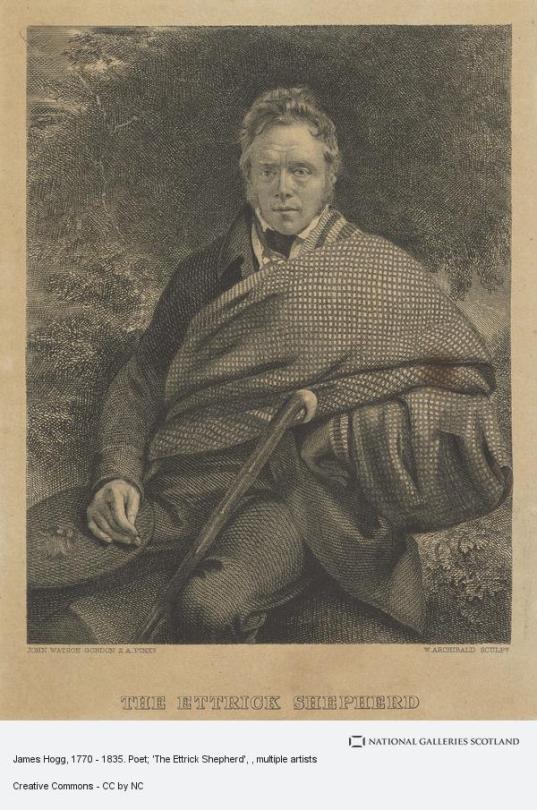

On November 21st 1835 the Scottish makar James Hogg, the poet died in Ettrick.

I say poet, but Hogg defied categorisation. As well as his poems he is known as a songwriter, playwright, novelist, short story writer and parodist, he wrote with equal skill in Scots and English. Labelled as the Ettrick Shepherd, the former Borders farmhand, whose life spanned the 18th and 19th centuries, befriended many of the great writers of his day, including Walter Scott, John Galt Lord Byron,and Allan Cunningham.

Even though he was celebrated off and on in his own lifetime, some details of the author’s life remain unclear. Records place his baptism on December 9, 1770. But Hogg long believed he was born in 1772, on January 25 – Burns’ Night no less.

Aside from mimicking medleys, Hogg’s own body of work is made up of mountains of bits and pieces – and must be enjoyed on those terms. Seeking conclusions or definitive statements will only frustrate. Tales can drift off into fragments of poetry both familiar and new. Within stories he flips perspectives with little warning.

His , The Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner us described as dark, humorous, violent, sweet, light, weird, wild,

Hogg’s mother, Margaret Laidlaw, was an important collector of Scottish ballads and a canny taleteller. His maternal grandfather, known as Will o’ Phawhope, was said to have been the last man in Selkirkshire to speak with fairies. Fairytale figures certainly fill Hogg’s most imaginative stories, most notably in his first collection of prose fiction, The Brownie of Bodsbeck and Other Tales (1818).

Burns was an early influence on Hogg, who considered himself to be the rightful heir to the Bard of Ayrshire and published his own collection less than four years after his idol’s death. Long before then, the locals dubbed him Jamie the Poeter, and he wrote countless songs for local girls to sing.

After writing a popular patriotic song, “Donald Macdonald”, in 1803, Hogg was recruited to collect ballads for Scott’s Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border. He also undertook extensive tours of the Highlands with a view to securing his own farm, but became more interested in the songs he heard along the way.

By 1819, he was recognised as a leading expert on Scottish ballads when the Highland Society of London commissioned him to produce the Jacobite Relics of Scotland, which became the benchmark of Scottish anthologies for many more decades.

He endured many failures on the way. In 1810, at the age of 40, Hogg moved to Edinburgh to settle into the life of a full-time writer. Within a year of starting it, his magazine The Spy folded. Readers weren’t ready for a publication that covered shocking themes such as extramarital sex!

Hogg spent the next few years scribbling more poetry and prose, and in 1817 he helped the subject of a post only yesterday, William Blackwood establish Scotland’s most influential literary periodical, the Edinburgh Monthly Magazine (later, Blackwood’s Magazine). In time, displaced by punchy younger contributors, Hogg eventually became a figure of fun in the same periodical. But he kept writing and writing. Winter Evening Tales, produced in the middle period of his life, is said to have been especially rewarding.

The University of Dundee recently produced a free online edition of The Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner, which includes explanatory notes and copies of the earliest reviews. Scotland’s great intermixer awaits new readers on the link below.

The statue of Hogg can be found at St May's Loch near Selkirk.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Great Slowing Doon has meant that it’s took ages for me to get roond to sharing this article here, a product of mony discussions, including those online with my fellow City Makars past and present across Scotland - especially Jim Carruth, Laura T Fyfe, Hannah Lavery, Niall O'Gallagher and Alan Spence. (Thanks of the heartfelt variety are due to the Scottish Poetry Library for providing the platform and support for this.)

#Dundee#Dundee Makar#City Makars#Scottish Poetry Library#Makar#Jim Carruth#Laura T Fyfe#Hannah Lavery#Niall O'Gallagher#Alan Spence#The Great Slowing Down

1 note

·

View note

Text

Phorgotography, 3

vii this is enough(This is another instance of Facebook popping up a few photos at random, me finding myself responding more thoughtfully to them than Ι’d expected – ie being a bit floored by the coincidence – only not to be able to post the result, as in the time it took, Facebook’s inexorable algorithms had already moved on.

In this case, just as I had hit the Post button, news came up of a…

View On WordPress

#Anhui#Beach Terrace#Broughty Ferry#Covid#Crete#Dundee Makar#Knossos#Michael and Margaret Snow#Nikola Madzirov#The Labyrinth#The Street of Knives#The Tay#Tiananman#Tianjin#W.S. Graham#Yang Lian

0 notes

Video

youtube

On September 1st 1863 the Angus poet Violet Jacob, author of “The Wild Geese” was born at the House of Dun near Montrose.

Her full name, take a deep breath, was Violet Augusta Mary Frederica Kennedy-Erskine, known for her novels of Scottish history and her poetry written in the rich dialect of Angus, Violet was born into an aristocratic family, and lived her adult life as an officer’s wife in England and abroad, the majority of her work however was from around Montrose, and Dun, the seat of her Family.

Perhaps here most famous work is the poem The Wild Geese a sad poem of longing for home, Violet is honoured at Makars Court just off the Lawnmarket, Royal mile with the line from the poem below “There’s muckle lyin’ ‘yont the Tay that’s mair to me nor life.”

Violet Jacob was described by a fellow Scottish poet Hugh MacDiarmid as “the most considerable of contemporary vernacular poets”.

She died of heart disease on 9th September 1946 and was buried beside her husband at the graveyard at Dun kirk.

There are many versions of this online but the best by far is by the late Dundee folk singer Jim Reid, please if you are going to listen to and watch one wee video today, make it this one, it’s only 3 minutes of your day and it’s worth it just for the spoken intro, rarely will you hear an Angus accent so rich. The song isnae twa bad either.

Norlan’ Wind (The Wild Geese)

This sad poem of longing for home, by Angus poet Violet Jacob, was set to music and popularised by Angus singer and songmaker Jim Reid.

Oh tell me what was on your road, ye roarin’ norlan’ Wind,

As ye cam’ blawin’ frae the land that’s niver frae my mind?

My feet they traivel England, but I’m deein’ for the north.

My man, I heard the siller tides rin up the Firth o Forth”

Aye, Wind, I ken them weel eneuch, and fine they fa’ and rise,

And fain I’d feel the creepin’ mist on yonder shore that lies,

But tell me, ere ye passed them by, what saw ye on the way?

My man, I rocked the rovin’ gulls that sail abune the Tay.

But saw ye naething, leein’ Wind, afore ye cam’ to Fife?

There’s muckle lyin’ ‘yont the Tay that’s mair to me nor life.

My man, I swept the Angus braes ye ha’ena trod for years.

O Wind, forgi’e a hameless loon that canna see for tears!

And far abune the Angus straths I saw the wild geese flee,

A lang, lang skein o’ beatin’ wings wi’ their heids towards the sea,

And aye their cryin’ voices trailed ahint them on the air –

O Wind, hae maircy, haud yer whisht, for I daurna listen mair!

The lyric is a conversation between the poet and the North Wind.

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

On 13th August 1867 William Craigie, the Scottish lexicographer, was born.

Isn’t it funny that us Scots started some of the most famous English establishments, like William Paterson who gave them The Bank of England, then Professor James Murray, the primary editor of the Oxford English Dictionary from 1879 until his death.

And we come to today’s subject, Sir William Craigie, a Scotsman from Dundee he was the third editor of the what is now commonly referred to as the ‘Oxford Dictionary’ or the ‘Oxford English Dictionary’(OED). He was editor of it for over 30 years.

It wasn’t always the English words for oor William though, born the youngest son of James Craigie and Christina Gow, William Craigie spent his formative years in his birth town of Dundee where, under the tutelage of his grandfather and older brother, he was introduced to Scottish Gaelic. This early taste of insular languages instilled in Craigie a passion that would endure for the rest of his lifetime. During his time studying at the West End Academy, Dundee, he began voraciously consuming the works of the early Scottish “Makars” – Robert Henryson, William Dunbar and Gavin Douglas – who would later become known among literary critics as the Scots Chaucerians for their role as the founding fathers of Scots literature.

As well as studying at St Andrews and Balliol College Oxford, where he learnt German, French, Danish and Icelandic, Craigie found himself at the University of Copenhagen where he added Medieval and Modern Icelandic to his ever-increasing list of languages.

Come 1897 Craigie’s lexicographical career began to take flight when the editorial board of the Philological Society’s New English Dictionary (soon to become the OED) were desperate to find a third Editor and Craigie’s name was put forward as a potential candidate. When Craigie received the fateful letter inviting him to work on the Dictionary on a trial basis; he was so keen, he even postponed his honeymoon with his newly wedded wife, Jessie Kinmond, to take up the position alongside the aforementioned James Murray, so you now had two Scots at the head of putting together the greatest collection of English words ever undertaken!

Let’s not forget, while he was employed full time on the English dictionary, Craigie continued with his other passion, A Dictionary of the Older Scottish Tongue (DOST) and in 1907, gave a lecture in Dundee on the action necessary to involve local people in collecting ‘Scots words, ballads, legends, and traditions still current’. The DOST was compiled over the following 8 decades and covers the language of Scotland from its earliest beginnings up to 1700. DOST has over 50,000 separate entries with over 581,000 illustrative quotations, and the 12 large printed volumes contain a total of 8,104 pages.

46 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

On September 1st 1863 the Angus poet Violet Jacob, author of “The Wild Geese” was born at the House of Dun near Montrose.

Her full name, take a deep breath, was Violet Augusta Mary Frederica Kennedy-Erskine, known for her novels of Scottish history and her poetry written in the rich dialect of Angus, Violet was born into an aristocratic family, and lived her adult life as an officer’s wife in England and abroad, the majority of her work however was from around Montrose, and Dun, the seat of her Family.

Perhaps here most famous work is the poem The Wild Geese a sad poem of longing for home, Violet is honoured at Makars Court just off the Lawnmarket, Royal mile with the line from the poem below “There’s muckle lyin’ ‘yont the Tay that’s mair to me nor life.”

Violet Jacob was described by a fellow Scottish poet Hugh MacDiarmid as "the most considerable of contemporary vernacular poets".

She died of heart disease on 9th September 1946 and was buried beside her husband at the graveyard at Dun kirk.

There are many versions of this online but the best by far is by the late Dundee folk singer Jim Reid, please if you are going to listen to and watch one wee video today, make it this one, it’s only 3 minutes of your day and it’s worth it just for the spoken intro, rarely will you hear an Angus accent so rich. The song isnae twa bad either.

Norlan’ Wind (The Wild Geese)

This sad poem of longing for home, by Angus poet Violet Jacob, was set to music and popularised by Angus singer and songmaker Jim Reid.

Oh tell me what was on your road, ye roarin’ norlan’ Wind,

As ye cam’ blawin’ frae the land that’s niver frae my mind?

My feet they traivel England, but I’m deein’ for the north.

My man, I heard the siller tides rin up the Firth o Forth”

Aye, Wind, I ken them weel eneuch, and fine they fa’ and rise,

And fain I’d feel the creepin’ mist on yonder shore that lies,

But tell me, ere ye passed them by, what saw ye on the way?

My man, I rocked the rovin’ gulls that sail abune the Tay.

But saw ye naething, leein’ Wind, afore ye cam’ to Fife?

There’s muckle lyin’ ‘yont the Tay that’s mair to me nor life.

My man, I swept the Angus braes ye ha’ena trod for years.

O Wind, forgi’e a hameless loon that canna see for tears!

And far abune the Angus straths I saw the wild geese flee,

A lang, lang skein o’ beatin’ wings wi’ their heids towards the sea,

And aye their cryin’ voices trailed ahint them on the air –

O Wind, hae maircy, haud yer whisht, for I daurna listen mair!

The lyric is a conversation between the poet and the North Wind.

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Four Roberts.

Robert Fergusson

1750-74

No sculptur'd Marble here nor pompous lay

No storied Urn nor animated Bust

This simple stone directs Pale Scotia's way

Fergusson was born in Edinburgh in 1750 - the third of four children. He was educated at high schools in Dundee and Edinburgh before completing his education at St Andrew's University.

His first poems were published in 1771 in Walter Ruddiman's Weekly Review. Origianlly he wrote in English but by 1772 he had started to use the Scottish dialect in the standard Habbie verse form - a form which would later be copied and made famous by the second of our Robert’s and more famous, Mr Burns. Rabbie’s use of this form of verse would later mean it became known as the Burns stanza.

Fergusson's promising poetic career was soon ended however when he sustained a head injury - possibly from a fall down some stairs - and became bedridden. He was then transferred to Bedlam against his will and he died there on October 17, 1774 at the age of 24.

Burns was happy to acknowledge his debt to Fergusson and contacted the Edinburgh Kirk on finding out he had an unmarked grave he offered to pay for one to be erected. Burns also composed the three verse epitaph - the first stanza of which was carved on the headstone as seen above, and on the first pic. The headstone was erected in 1787.

Later, Robert number three, Mr Louis Stevenson agreed to renovate the headstone - but his own premature death prevented him from making good his promise - though there is a plaque at the foot of Fergusson's grave recording his intention: 'This stone, originally erected by Robert Burns, has been repaired at the charges of Robert Louis Stevenson and is by him re-dedicated to the memory of Robert Fergusson as a gift of one Edinburgh lad to another.'

In a letter to Alexander Balloch Grosart - Stevenson writes touchingly about both Fergusson and Burns: 'We are three Robins (Roberts), who have touched the Scots lyre in this last century. Well the one is the world's, he did it and the other, ah, what bonds we have! Born in the same city, both sickly both pestered - one nearly to madness and one to the madhouse, both seeing the stars and the moon and wearing shoe-leather on the same ancient stones.'

Today, Fergusson is held in high regard in Scottish literary circles. Most of you who have visited Edinburgh may very well have seen his statue outside the Kirkyard.

From The Daft Days

Auld Reikie! thou’rt the canty hole,

A bield for many caldrife soul,

Wha snugly at thine ingle loll,

Baith warm and couth,

While round they gar the bicker roll

To weet their mouth.

Now I know those that may have ventured into the Kirkyard and seen this grave will know about the story, or perhaps you have read one of my previous posts about the three Roberts, I like to liven my posts up rather than just let you read the same moosh time after time, so I have added the fourth Robert to this tale, Robert Gairloch, a twentieth century Scottish poet and translator. His poetry was written almost exclusively in the Scots language, he was another native of Edinburgh, in 1962 he visited the grave and was to reflect that ‘here Robert Burns knelt and missed the mool’ [clay] this is what he wrote.

At Robert Fergusson’s grave

Canongait Kirkyaird in the failing year

is auld and grey, the wee rosiers are bare,

five gulls leam white agin the dirty air:

why are they here? There's naething for them here.

Why are we here oursels? We gaither near

the grave. Fergusons mainly, quite a fair turn-out,

respectfu, ill at ease, we stare

at daith - there's an address - I canna hear.

Aweill, we staund bareheidit in the haar,

murnin a man that gaid back til the pool

twa-hunner year afore our time. The glaur

that haps his banes glowres back. Strang, present dool

ruggs at my hairt. Lichtlie this gin ye daur:

here Robert Burns knelt and kissed the mool.

Now other poets have taken the pilgrimage to our relatively unknown makars grave, Sorley MacLean and Hugh MacDiarmid, to name but two, but they’re not called Robert so that’s the end of this post.

36 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

On September 1st 1863 the Angus poet Violet Jacob, author of “The Wild Geese” was born at the House of Dun near Montrose.

Her full name, take a deep breath, was Violet Augusta Mary Frederica Kennedy-Erskine, known for her novels of Scottish history and her poetry written in the rich dialect of Angus, Violet was born into an aristocratic family, and lived her adult life as an officer’s wife in England and abroad, the majority of her work however was from around Montrose, and Dun, the seat of her Family.

Perhaps here most famous work is the poem The Wild Geese a sad poem of longing for home, Violet is honoured at Makars Court just off the Lawnmarket, Royal mile with the line from the poem below "There’s muckle lyin’ ‘yont the Tay that’s mair to me nor life."

There are many versions of this online but the best by far is by Dundee folk singer Jim Reid, please if you are going to listen to and watch one wee video today, make it this one, it's only 3 minutes of your day and it’s worth it just for the spoken intro, rarely will you here an Angus accent so rich. The song isnae twa bad either.

The Wild Geese.

‘Oh tell me what was on yer road, ye roarin’ norlan’ Wind,

As ye cam’ blawin’ frae the land that’s niver frae my mind?

My feet they traivel England, but I’m deein’ for the north.’

‘My man, I heard the siller tides rin up the Firth o Forth.’

‘Aye, Wind, I ken them weel eneuch, and fine they fa’ and rise,

And fain I’d feel the creepin’ mist on yonder shore that lies,

But tell me, ere ye passed them by, what saw ye on the way?’

‘My man, I rocked the rovin’ gulls that sail abune the Tay.’

‘But saw ye naething, leein’ Wind, afore ye cam’ to Fife?

There’s muckle lyin’ ‘yont the Tay that’s mair to me nor life.’

‘My man, I swept the Angus braes ye hae’na trod for years.’

‘O Wind, forgi’e a hameless loon that canna see for tears!’

‘And far abune the Angus straths I saw the wild geese flee,

A lang, lang skein o’ beatin’ wings, wi’ their heids towards the sea,

And aye their cryin’ voices trailed ahint them on the air –’

‘O Wind, hae maircy, haud yer whisht, for I daurna listen mair!’

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Rosie

‘...it wasn’t only the ethos of the school that had moved to the new campus – but also a blackboard from the old premises which features the signatures of staff and pupils.’

When demolition follows faster on construction’s heels

till all our childhood’s classrooms catch up with long ago,

it almost seems we're knocking down our future

before it can arrive - what can we teach

that's primary about what we must keep?

A blackboard from a vanished school, always rolling,

never unspooled palimpsest that can never rest,

at once preserved and flitting, fittingly reveals

the hands that teach and those that learn

in literate dust. So a shroud of concrete is shrugged off

for a christening gown of classy new glass:

the Rosebank, still the Rosie, ’s aye the Rosie.

0 notes

Link

I meant to post this approximately a month ago, but personal stuff intervened, so it wiz anely in the last couple o weeks I actually got inside Dundee's V n A - and last night wiz the first time I read it no tae camera on the banks o Tay, but tae ackshul Dundonians in the Wighton Heritage Centre in Dundee Library, at an event organised and delivered by the excellent Erin Farley for Being Human Dundee and Book Week Scotland.

#Dundee#The V&A#The Wighton Heritage Centre#Dundee Public Library#Erin Farley#STV#Dundee Makar#Being Human Dundee#Book Week Scotland

0 notes