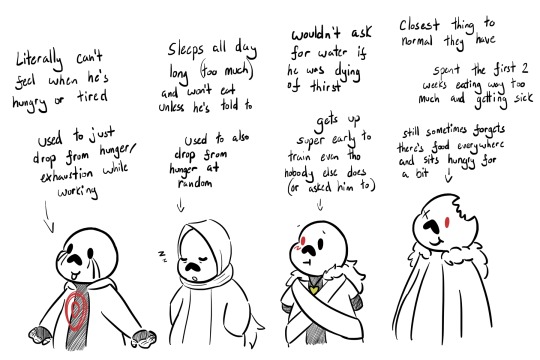

#Dust is the worst for food but Horror can coax him into enough food to get by

Text

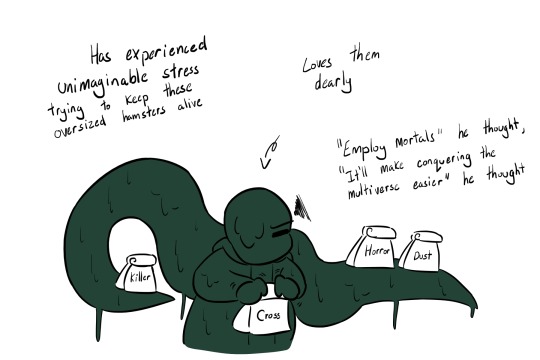

Thinking about how Nightmare has 4 mortals and 3 of them are so so bad at taking care of themselves

#UTDR#UTMV#My Art#Truce au#Killer Sans#Dust Sans#Cross Sans#Horror Sans#Nightmare Sans#''I don't feel like drawing a bunch I'll just do a quick silly doodle'' sits up until 1am finishing this#But this is about their bad habits not mine so#Killer and Cross are the worst offenders for sleep but they're pretty managable#Dust is the worst for food but Horror can coax him into enough food to get by#Horror was - for a short time when he first joined - Nightmare's clear favourite#Because he would actually ASK for things when he needed them#(Not that his joining didn't have problems of it's own but y'know#Nightmare was starting to expect it at this point)#I should ramble for 10 pages about the boys joining the gang someday#Not now cause I'm going to bed but y'know#Anyway goodnight gang!

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Wasteland, Baby!

Author: kpopfanfictrash

Pairing: Yoongi / Reader

Word Count: 3,098

Warnings: post-apocalyptic, depression, themes of death

Summary: A songfic, inspired by the song of the same title by Hozier (I’ve had this sitting in my drafts for months and finally decided to post)

The end of the world was not as terrible as everyone thought it would be.

Or – that is what you have told yourself since, citing the mantra to keep the demons at bay. On the days when it does not work, when you cannot convince yourself of this fact, it is hard – near-impossible – to get out of bed.

Today is a good day. Today, the end of the world is not so terrible.

Yesterday was a bad day.

Yesterday, Yoongi tried for twenty-four minutes to coax you from under the sheets. Eventually, he gave up and left to chop more wood for the fire. Six minutes into his absence, you woke in a sweat-soaked terror, hands scrambling through blankets to seek out his warmth. Visions flashed through your mind, one after the other, like the worst kind of picture show.

Ashen faces, choked breathing, bloody splotches. Deadened gaze.

In the end, the world did not end with bloodlust and rage – but with folly.

It was folly that humans chose to live so close to one another, packed into homes stacked on top of the other. It was humans who were so dependent on technology that they could not survive once it disappeared. Once there were not enough people to run the power plants and take care of the phone grids.

Truly, Yoongi is the only reason you are alive. On most days, you can convince yourself this is a good thing. When the disease first emerged, Yoongi was the one monitoring it all from his phone. In those days, he came home from the lab later than usual, brow permanently furrowed and sandwich crumbs on his sweater.

Those were the days when you were his anchor, when you were the one who coaxed him in and out of bed. Yoongi was your workaholic pathologist boyfriend and you were his rock. Now, the situation is reversed and you find this to be oddly appropriate. Everything should be flipped at the end of the world.

It was when the airports began closing Yoongi demanded you leave.

“Today,” he said, slamming the apartment door as he entered.

You looked up from your workstation, surprised by his appearance. Architecture papers were spread out before you, half-finished buildings drawn in blue and white lines. Typically, Yoongi did not get home until after dinner on weekdays. You were used to the hours spent alone, sketching at your table.

“Today… what?”

Yoongi’s eyes were red-rimmed; evidence of his many late nights. Circling your table, he came to a stop at the wardrobe. “My place outside the city,” Yoongi said, avoiding the question. “We can go there. Wait it out.”

“Wait what out?”

He paused before the drawer, one mustard-colored sock dangling over his hand. Swallowing, Yoongi seemed to wrestle with something. “Maybe nothing,” he said quietly. “Or… maybe something.”

You stared at him for a moment, debating how to respond. Granted, you thought Yoongi had gone insane. Everyone was saying this would blow over, like all the other scares. Avian Flu, Swine Flu and a million other Flus. Yoongi seemed serious though, as though he had not slept in weeks and likely, that was so. Everyone in Yoongi’s lab had been working overtime to search for a cure. Yoongi was one of the first among them to recognize the truth.

As an outsider, you were biased by precedent. As a human, you had always survived. This is another folly of humans – they think themselves invincible. They assume because they have survived thus far, they will continue to do so.

Most of the world’s population assumed this. Then again, most of the world’s population is now dead.

Something in Yoongi’s eyes convinced you. “Okay,” you said, standing up from your stool. It was better to humor him, at least. “What do I do?”

Forty minutes and one hastily packed trunk later, you two sped off down the highway. Few cars were on the road that day – in the early time of the sickness, most people stayed in. They quarantined themselves, only venturing out when absolutely necessary. It was merely a flu at that point – the world did not yet understand.

It was from Yoongi’s cabin you watched the world fall apart. The footage was horrifying – riots, looting when the hospitals became dead zones, and then the airports, and then everywhere. The TV stayed on until the cabin ran out of power, until the people were gone and there was nothing left to be said. You watched as, one by one, newscasters silently replaced one another. No one explained why, but you both knew the truth.

The world’s population was decimated in a matter of days. You and Yoongi watched it all happen, huddled on your couch and immobile with shock.

You two were lucky, you suppose. Yoongi kept his cabin stocked for his work rampages; the times he got a research hunch and would seclude himself for weeks in his reading. The cabin held everything one needed for the end of the world – canned goods, water purifiers, emergency candles and matches. The rations held out remarkably well while you determined a new way to survive.

Now, it has been three months since the lights went out.

For weeks you slept on edge, waking at the slightest brush of wind on the window. Living alone was a new kind of terror. Living in the city, there were dangers, but technology was always present to keep you protected. It warned you of intruders, kept the doors shut and updated you on your surroundings. No longer.

One month after the end, you ventured out in Yoongi’s car. Yoongi decided that, based on his research, most of the virus would be dead by that time. It needed living hosts to survive. Still, it was a risk and he would not let you leave the confines of the vehicle.

The closest town to the cabin was once called Roshone – a small, miniscule lake village of maybe two thousand. You say once because now, just two people remain.

You and Yoongi.

The drive through the streets was silent, chillingly so. Unplowed snow crunched under your tires. Yoongi peered out from the windshield, searching for life but finding nothing to speak of. No footprints in the snow, no flashes of movement from the corner of your eyes.

Many doors were marked with red x’s of paint – a makeshift Passover you quickly averted your gaze from. After about an hour, you returned to the cabin. This was the first of your dark days. For three days following, you did not rouse from your bed.

That was when you believed the world had truly ended; you two were merely ghosts, biding your time until you joined all the rest.

The silence was the worst part.

There were many days you forgot to speak, going from sunup to sundown with nary a word. Philosophy is what separates humanity from animals and so, when humanity is dead, what separates you then? What makes you different from the rest of the mammals when there is no one to talk to? Nothing. And so, you continued your motions of living – but only enough to survive. A gross pantomime of what you were before.

Yoongi clung to his routines.

He woke early each morning, as he did in the city. As long as there were beans, he made coffee over a fire. When the beans ran out, Yoongi heated plain water for tea. When his computer died, he dug out books from his study and poured over those. What he was searching for, you did not ask. It all seemed futile to you.

Yoongi had never been a very positive person and so, in many ways, he was better equipped for the end. Perhaps this is why he adapted better than you. He had a stoic realness about him which suited the end times.

When you needed food, Yoongi learned how to shoot. He researched how to garden and found books to prepare for the springtime. The sight nearly made you laugh, watching him read about plants. Yoongi had always made fun of Namjoon and his bonsai trees. Remembering, you winced, heart tightening at the memory. Namjoon was a cold dose of realism you could not ignore.

All of your neighbors stayed when you two fled from the city. You do not know if they made it out. Somehow, you doubt it.

You often find yourself wondering which was be worse – the disease, or its aftermath. Anything must be better than this. Anything but this silence, this sadness, this agonizing nothingness which tears you apart and –

Banging open the door, Yoongi walks in.

His entrance reminds you of that day so long ago when he convinced you to flee. Remembering, you stare blankly at him from the bed. Yoongi is framed by the door; silvery light filters past and for a moment, he seems like some kind of savior.

Then, he is over the threshold and the door is pulled shut. Dropping a bag to the ground, he shakes dust from his shoulders. The light disappears and he is no longer a savior, merely Yoongi.

Stubborn, brave, wonderfully human Yoongi.

“I found more candles,” he says, removing his jacket. The cabin is small – only three rooms, the front of which contains a bed, kitchen and sofa. Crossing to the bed, he settles beside you. Yoongi’s hand covers yours, his eyes dark and sad. “How are you today?”

Glancing past him, you stare at the bag. “You found candles? Where?”

Yoongi’s lips tighten in a way which lets you know you will not like the answer. “I went into town again.”

Swiftly, your gaze moves to his. “Yoongi! That could be dangerous!”

He exhales, rubbing his thumb against yours. “There’s no one there, babe.”

“… No one?”

“No.”

Quietly, you let this statement sink in. A month prior, his words would have crippled you. Now, it simply seems… usual. This fact should give you alarm. It should not be normal for you to think of an entire town dead and not feel some remorse. It should spark sadness, at least – or maybe some sort of horror, outrage, or despair.

Lowering his head, Yoongi brushes his lips to your hand. “Y/N,” he says, against your skin.

“Yes?”

He slowly looks up. “I feel numb.”

Freezing, you take in his expression. Yoongi stares back at you, helpless and you realize with shock he was counting on this. He was counting on there being someone left but finally, the evidence is too great and he is giving up. Yoongi, your steadfast in this ocean of madness – the one who coaxes you out of bed, who convinces you to make a plan – has given in.

He truly thought you were not alone.

And now, he does.

You can see it in his gaze. There is a haunted fear which can be explained in no other way. It is one thing to treat this as a vacation, a temporary respite before getting back to your life – it is another thing to accept this is reality.

Hesitantly, you push yourself into a seated position. Carding your hands through his hair, you examine his face. Yoongi’s locks are long, shaggy across the front where you cut them poorly with scissors.

“Numb?”

Gently, he closes his eyes. “Maybe you were right.” Lowering himself on his side, Yoongi scoots back to make room. “Maybe there isn’t a point anymore. Maybe we should just… sleep. I don’t know.”

His arm slips over your waist, pulling you into him. His breathing softens, warm on your throat and normally, you would sleep, too – except Yoongi is not supposed to be numb. He is not supposed to be the pointless one, the aimless one. The entire time you have known him, Min Yoongi has been driven by something. Without that…

The world has not yet ended, you realize.

It ends when you both think it has.

His snores rattle your body, letting you know he is sleeping. Once you are certain, you slip from his arms and lower both feet on the floor. The floorboards are cold, making you shiver. Pulling on his jacket, you deeply inhale. It smells like Yoongi, but not city Yoongi.

City Yoongi always wore the same jeans, used the same laundry detergent and slept in the same bed. He smelled of chemicals from the lab, shampoo from CVS and some fancy cologne. This Yoongi smells like woodsmoke; metal and iron and the bitter taste of wind.

It is not a bad smell. Glancing over your shoulder, you find him asleep, like a rock. Yoongi does not move, one arm dangled over the mattress to drag on the floor. Without pausing to think, you grab the keys of his car and walk into the cold.

Seated behind the wheel of Yoongi’s black Ford Taurus, you stifle a shiver. There is a knife on the floor of the passenger’s side. You glance at this quickly before looking away. Hopefully you will not need to use it. As you pull from the driveway, you follow Yoongi’s earlier tracks into town. It has been a long time since you drove. Even longer, since you went out alone.

The engine seems loud – near-deafening, compared to the silence of Main Street. Your gaze flicks uneasily over each storefront; despite Yoongi’s insistence that they are deserted, it is hard not to imagine the worst.

Pulling into a parking space – even at the end of the world, some habits die hard – you turn off the engine and sit for a moment. Your hands are shaking, clutching the wheel and you force yourself to let go.

Outside, the winter air is crisp on your skin. Despite the lack of humanity, the world has not yet noticed the void. Or, if it has, it does not care. The snow crunches beneath your feet as you cross the street, peering into a shop to pause on its curb.

The windows are dusty, untouched for months and the tables inside have not fared much better.

At last, you inhale and push open the door. It is unlocked, as though the former owner left in a rush. You winkle your nose at the staleness of air. Flies buzz past when the door swings shut behind you. Shadows stretch before you, elongating the worst parts of your imagination. Beneath the sweet smell of chocolate and sugar is a damp, rancid stench you know all too well.

You shiver. The virus should be dead but always, there is this fear. What if?

Ignoring this – and the back room from whence the smell stems – you cross the room and duck behind the register. Bags, boxes and canisters line the shelves at eye-level. Grasping the first one you see, you grit your teeth together and bolt towards the door.

Outside, seated in the driver’s seat, you finally exhale. Lowering your head to the steering wheel, you sit still for a second. Vision blurring, you stare at the vinyl wheel of the car. So many people are gone. The sheer magnitude always weighs on you, wondering why you survived when so many did not.

You glance sideways. The bag you took lies on the floor, beside the knife. For some reason, the image strikes you as funny. Your upper lip twitches.

Taking that bag makes you a thief. You have never stolen something before.

Of course, in this hellish landscape where the word means nothing, you find yourself a criminal.

A laugh escapes, too loud in the silence. Clasping trembling fingers over your mouth, you attempt to shove it back in, only to realize – why? No one is here. There is no one around to be quiet for and so, you laugh.

Again.

And again, until tears mix with the madness and slide down your cheeks.

Did Yoongi say he felt numb? Did you ever feel numb? Right now, you are the opposite. You are every emotion ever felt in the universe; a black hole drawing everything in and spitting out nothing. You are bursting, so full of anger you think you might break.

Full of sadness, as well. And hope.

It is a long time before you can see clearly enough to turn on the engine. Stubbornly, the car catches beneath you and in the fading rays of twilight, you drive back to the cabin. As you go, you keep wiping tears with one hand. It is lucky that no one else is on the road, since you are certainly a hazard to the silence’s safety.

As the cabin comes into view, you recognize something is wrong.

The front door is ajar, which is not how you left it. Footsteps are stamped in the snow – fresh ones, frantic ones which are not your own. Throwing the car into park, you stare at the doorway. Reaching out, you grab both bag and knife from the seat. The weapon seems foolish to hold, since you are not a killer, but you do so anyways.

Yoongi barrels around the side of the house.

He comes to a stop at the door, chest heaving. His eyes are wide, gun trained on your head.

Yoongi pauses.

“I,” he exhales, squinting into the cold. “…Y/N?”

“It’s me.” Regaining motion, you push open the door. Hurriedly, you drop the knife to the ground. “Yoongi, it’s me.”

“Y/N.” He repeats your name, slightly lost. “What are you doing?”

Unsure what to say, you walk towards him. Once he is there, your feet falter. “Here,” you say, thrusting the small bag upon him. “I – I went and got you coffee.”

Yoongi does not move. He stares at the package, not understanding. Wind ruffles his hair, exposing pale skin and hesitantly, Yoongi reaches out a hand. “Coffee?” he murmurs. Turning the bag over in his palm, he looks up. “Why?”

Staring at him, you feel oddly exposed. You thought you knew Yoongi, but here in this dead world, everything is new.

“Because,” you whisper, feeling somewhat foolish. “You like coffee. You need it… for, you know.”

To not be numb anymore.

Yoongi does not move for a moment. He stands there, bag of beans in one hand and looks wonderingly at you. Then, he drops the bag to the snow and crushes you hard to his chest.

Yoongi buries his face in your neck, exhaling brokenly. For the second time in the same hour, your vision blurs. Hugging him tightly, you burrow your face in his sweater. His large hand strokes your hair, winding in strands and keeping you firm in his arms.

Yoongi chuckles when he feels you wipe your nose on his front. “You know I’m still here?” he whispers into the shell of your ear. “Right?”

You nod, pulling back to see him. Tears cling to your lashes, and you blink them away. For the first time in months, you feel the breeze on your skin. It does not make you feel numb, but alive. The rustle of the wild is all around you.

The world is not dead – merely holding its breath.

Yoongi stares back.

“I know.” Lifting on tip toe, you brush a kiss to his lips. “I know. I’m here too, okay?”

Swallowing a smile, Yoongi nods. “I know.”

© kpopfanfictrash, 2019. Do not copy or repost without permission.

#btsbookclub#bangtanarmynet#yoongi fanfic#bts fanfic#yoongi imagines#bts imagines#yoongi writing#bts writing#yoongi angst#bts angst

738 notes

·

View notes

Text

She was quiet, and Trucy Wright was never quiet. She was a ball of endless, bubbly energy, spinning around and bouncing off the walls until finally collapsing in a heap of happy exhaustion. Collapsing into waiting arms, sometimes, like she had in the hotel room in Vienna - twirling her new cape around until she was dizzy and Miles caught her, and she and her father laughed like there wasn’t any darkness that could touch them.

Trucy Wright was quiet and still, and Miles waited to catch her.

“Are you hungry?” He glanced at her from the corner of his eye; she was staring through the window, curled up as close to it as she could, as though she was trying to find a way to be alone even in the close confines of the car. “It’s early, but -“

“You’re stalling, Uncle Miles.” Her voice was barely a murmur, barely there.

Fair enough. He didn't want to be in this car, either, driving to where he was going now. He wanted to be in Vienna, in the hotel room with two beds and the view overlooking the city, Trucy giggling and bouncing on the bed, pestering them with questions, and Phoenix -

Miles' hands tightened on the wheel. What wouldn't he give, to be back in Vienna for just one more moment.

"You didn't have to come." The tone was gentle but the words were all wrong, and Miles wasn't sure that he wasn't adding to her hurt. "I would have understood -" he tried again, but something in the words caught in his throat and clung, trying to drag his heart out of him against his will. That had been happening a lot in the past couple of days; he never seemed to see the mines around him until he'd already fully stepped onto one, stumbling on words and thoughts that robbed him of air and shredded through his chest. Innocent things, always - the grocery list on the fridge, Trucy's clinging hug, a glimpse into the closet before he turned off the light and firmly shut the door - in recent days, it took little to crumble Miles Edgeworth to pieces.

Trucy was looking at him now, taking in more than he meant to show. "I need to be there," she whispered, a little bit louder, a little bit stronger. Of course she was just like her father; of course seeing someone else who needed help let her pack away her own pain. Another landmine. "I want to see him."

And together, but somehow still so alone, they rode out the another wave of the aftershock.

The police hadn't found the source yet. All of the food in the house had been taken for testing, and Ema Skye personally sprayed every surface and item on the shelves. Nothing. Nothing to explain what happened, or to approach any sort of closure. Miles hadn't bothered to ask who and, to his extreme regret, Trucy hadn't had to ask, either. It made no difference - Kristoph Gavin had already been in and out of questioning, with no more doubt clinging to him than a bit of stray dust. He brushed the entire matter away with an offering of his condolences and an interest in visiting Mr. Wright.

Miles hadn't been able to think of a graceful way to tell him to go to hell, and so he hadn’t answered.

The room, when Miles and Trucy arrived, was sealed. The ICU didn't take chances with their patients, and certainly not this one, but there was a window to the room. Through it, they could see the machines, the tubes, the detritus of survival... and beneath it all, the person they'd come to see.

Phoenix Wright wasn't dead yet. But he was walking a narrow line.

The experience had been so different than the last. The call came in the middle of the day this time, from a panicked Trucy who didn't understand what was happening. The trip to the hospital had taken minutes instead of several long, agonizing hours, and he wasn't allowed anywhere near the room - which was just as well, because he had his arms filled with a crying girl asking for answers he couldn't give. There was no relief after speaking with the doctor, just the continued pain of he's hurting and I can't help him and I don't even know how long he'll last reverberating through him with every heartbeat.

And then he and Trucy had to go home, feeling like they'd left a limb behind, bleeding the whole way back.

"Hi Daddy," Trucy whispered to the glass. She was standing close enough that her breath fogged it. "I know it hasn't been that long, but it feels like it. I thought maybe I'd tell you about my day, but..." One of her hands had reached up to touch the window, like she could reach through. "Nothing much happened. I couldn't concentrate on anything, anyway."

Miles reached an arm around her shoulders, a gesture he'd learned from Phoenix and become more comfortable with as the years passed. When he felt Trucy lean into the touch, a little closer to him and a little farther from the window, he breathed easier. He was doing something right. So much depended on the little moments.

Her gaze was still firmly focused. "I miss you," she whispered, and he heard the same clawing thing in her own throat, threatening to come out.

"We both do," Miles managed.

He couldn't say how long they stayed at the window - longer than they should have, maybe, with no one but each other to coax them away. It was dark outside when they finally left the hospital and found Miles' car, hours after Trucy should have eaten. Phoenix would have reminded him. He would have to remember from now on. She deserved to be more than an afterthought.

When they were both sitting in the car and Miles’ key was already in the ignition, he sighed. “Trucy,” he began, hating the way his own voice sounded so quiet and thin, hating that he didn’t know if this would add to her hurt or break that fragile strength. “There’s something I need to talk to you about. I wish it could wait, but…” But Phoenix looked like a ghost on that bed, small and lost in the things keeping him alive. But Miles might get another phone call at any moment, and then it might be too late.

Trucy took a deep breath, gathering her courage. “What is it?”

He was going to have to tell her the truth: her father sat Miles down, years ago, with fear in his eyes, with the horror story they were all now in already a possibility in his mind. He asked Miles a question, and at the time it seemed too impossible to consider. Would he look after Trucy, if anything happened?

And somehow, as time passed, the question diminished. Somewhere, between Vienna and now, it stopped sounding impossible and became obvious. Of course he would look after Trucy. Anytime, anywhere, for any reason.

Even the worst reason.

“Your father and I… had a conversation, a long time ago. About what he wanted, if…” Another landmine, another earthquake trembling underneath him. Miles took a deep breath of his own. “About things that might happen. And about your future care.”

Glancing over at Trucy was a mistake; the night sky didn’t offer any judgment about his words, but the little girl next to him had her shoulders hunched almost to her ears as if she was waiting for a blow. He wanted to reach out to her and pull her into a hug, soothe that fear away, but he knew the best remedy was just to say the words.

“We found a provision in the law that allows for it, but we agreed that you should have a say.” She had, after all, had a say from the beginning. “Trucy, can I adopt you?”

Her shoulders slowly, slowly dropped. There was something tentative and very breakable in her eyes. Her voice was as soft and unsure as he’d ever heard it. “You aren’t going to leave me?”

This time, Miles couldn’t stop himself from reaching over to her, pulling her in as close a hug as he could manage across the console. She fell into him, clung to him with a vice grip. “I would never leave you, Trucy. Adoption or otherwise, whatever happens next, I will be here. I promise.”

For a while, neither of them spoke. Trucy sobbed into him, the first time since everything fell to pieces, and Miles held her in her collapse.

Silently, he promised her all of the things he couldn’t say. That he would catch the man who did this. That she would never have to fear being alone again. That if there was any justice in the world, their family would be whole again, someday.

When the sobs subsided and Trucy leaned back into her own seat, Miles waited for an answer. He got questions, instead. “Is that really something you can do? Adopt me when I’m adopted?”

“There is a legal precedent.” Few and far between, found after nights of digging through old adoption cases. Enough that, between them and his connections, he’d found a way.

"Would I have to change my last name?"

"No," he said, and in his mind where all of the other words he just couldn't say yet were, he thought: No, I would never ask you to give up any part of him. I would never take that away from you. I would never take him away from you. And if I can ever find a way to make any of this okay again, I would give anything. I would give everything. I would give Vienna and every place in between. “You can have whatever last name you’d prefer,” was what he said instead.

Trucy looked down at her hands. “I think I’d like to still be Trucy Wright, after the adoption.”

“It suits you,” Miles said, and she smiled at him with something painful, but not broken yet.

The two of them were not broken yet.

#ace attorney#miles edgeworth#trucy wright#angst#no character death but close to death#possibly :3#aa#aa4#and yes i know that's not how adoption laws work#murder trials also don't happen in three days#my city now

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

this is my @aftgexchange gift for @sirandking i’m not sure if this is quite what u were hoping for n it’s messy but idk i kinda like it

tw for mentions of alcohol as a coping mechanism, as well as super brief blink-and-you-miss-it mentions of riko, drugs and self-harm

ao3 link

“That sweater is new,” Kevin comments as he seats himself in the beanbag next to Andrew’s, passing over a mug of coffee as he does so. It’s a small, meaningless comment - the kind of small talk they both collectively despise - but it’s something, and since the death of Riko, Kevin’s found that there are not really any other threads connecting the two of them. Silence has panned out between them for weeks. He tells himself he’s irritated by it because it’s bad for the team’s dynamics - a rapport with your teammates is essential for a successful team. He won’t admit that Andrew is probably the closest thing to a friend Kevin has around here, except for maybe Neil.

He doesn’t expect his comment to be dignified with a response; he knows Andrew well enough to know to expect perhaps a nod of acknowledgement, or a stony look his way, questioning and judging his observation. Nevertheless, the silence makes him ever-so-slightly self-conscious, so as his eyes catch the way the sleeves fall over Andrew’s hands, he tacks on a lousy “–and too big for you.”

Andrew Minyard has always been best at defying expectations.

“It’s not mine,” he responds coolly, devoid of emotion or even acknowledgment, eyes still trained on the contents of his mug as he mutters, as though talking to no one.

It’s an easy enough admittance, casual and shameless, yet it still manages to leave Kevin embarrassingly taken aback. He knows, realistically, that he probably has the best insight into the relationship between Andrew and Neil than any other outsider, however he’s still never quite got it. The logical part of his brain tells him it shouldn’t work - two people both so shattered and fiery, like shards of broken glass, in such close proximity can only end in further shattering, as far as he’s aware. And flames. It’s concerning, something with so much power, with so many sparks - just one wrong move could become a savage wildfire that burns his team down to nothing more than ashes. It’s risky and dangerous and stupid and he hates it, is terrified of it, but this admittance that comes so easily changes something in him.

Because something about the idea of Andrew Minyard curled into a beanbag with a cup of coffee and his boyfriend ’s (and isn’t that in itself another unexpected and ever-so-slightly strange thing to wrap his head around) sweater on feels less like untamed sparks and more like a candle light. And that’s much more soothing than terrifying, even if it is still a little strange to him.

Perhaps trying to understand this would be a good idea, he concludes. So he asks “When did all this start for you anyway?” waving a hand conspiratorially to punctuate the question. And this time he’s almost convinced he’ll be ignored, or delivered a vague, meaningless answer as a result of the unspecific question, but the furrow of Andrew’s brow as he lifts his gaze up to Kevin’s tells him otherwise. It’s a strange, uncharted territory.

“February.”

“You liked him before then,” Kevin suddenly finds himself accusing before he can stop himself, still processing this new information, whilst considering every sign he could remember, the most poignant being the way Andrew did things for nobody but Neil. Could only have his arm twisted by Neil. Had always drifted towards Neil, had never raised a knife to Neil, had always been straight with admittances to Neil; Neil, Neil, Neil was the exception to every rule of the Andrew Minyard handbook, the one Kevin had studied meticulously and still never found a loophole in. He finds himself itching to know more.

“I hate him.” Andrew deadpans, a reflex at this point, and if Kevin was anyone else, he’d have furrowed his brow, wrinkled up his nose, frowned and found himself reprimanding Andrew, but he’s not anyone else, so he smirks instead, because he thinks he’s finally starting to understand how Andrew works, and this kind of understanding is as scintillating as it is spine-chilling, like watching a horror film, driving past a car crash or finding a spider in your room - the kind of fear that keeps you captivated, unable to tear your eyes away from it even when you know it’s awful, and you shouldn’t, and if this is what Andrew feels around Neil, no wonder he hates him. Andrew has never enjoyed feeling, as far as Kevin knows, and something so intense and contradictory, something that can’t be calculated and analysed can only be devastating.

The words “I know,” feel foreign and awkward on his tongue, his body tense as they slip out and it all multiplies when Andrew’s blank stare shifts from the mug he warms his hands on to Kevin’s face. “Why him?” he eggs on, trying to coax something out of Andrew, whether it be more answers and information, something to help him understand, or just a reaction, something to put the world back in order and dissolve the itchy curiosity and mere residue of fear that has settled on his skin.

Andrew ignores it entirely. “You’ve reached your daily quota of questions you can ask me for free.” He pauses, as though considering something for a moment, before finally deciding against whatever it is and dismissing Kevin with a curt “You can go now.”

Kevin goes.

The next time Kevin sees Andrew, it’s because he’s paused the exy game on his laptop and emerged from his room for the first time in hours after smelling something divine. He is greeted with the sight of an unholy amount of Indian food scattered across the table, and isn’t sure whether he wants to kiss Andrew (if he was not in a relationship, if Andrew was not in a relationship, if either of them were in any way attracted to each other and if he had a death wish - none of which are even remotely true) or kill him, because really , this is not how future professional athletes should eat, but he can hear Jean’s voice in his head telling him to relax, to loosen the tight leash of control he has over his life in order for total success, thus he reluctantly picks up the spare fork left on the side and a tub of something orange, before sitting on the other end of

the sofa to Andrew.

“Nicky and Aaron will be here soon,” Andrew states at the exact same time that Kevin asks “Where’s Neil?”, changing his course of action to start Kevin down instead.

There’s a handful of new mottled bruises adorning his face from who knows where, and a nasty looking cut beneath his eye that he’s certain Aaron will fuss over later, much to Andrew’s dismay, and for a moment he considers asking if he’s okay, before swiftly realising what a stupid idea that is and dismissing it completely as Andrew opens his mouth again.

“I’m not his keeper.”

“I know.” Again. Andrew sighs.

“Did I or did I not tell you that you have asked as many free questions as you are permitted to today?” This time, as Andrew snaps, Kevin hears it.

“Free?” he asks around a mouthful of rice, swallowing hastily before he continues. “So if I give you something, I can ask more?”

It’s a rhetorical question, but Andrew grants him a small nod anyway. “Neil and I have - had - a thing.” Kevin agonisingly anticipates his next words as Andrew scoops up another mouthful of food. Static silence stretches out between them until he swallows again. “Truth for truth. For everything you ask me, I ask you something.”

“Deal.”

“It’s my turn.” His gaze shoots skywards, face contorting in mock-thought. “Why are you so interested?”

“In?”

He rolls his eyes. “Do I have to spell it out?” is punctuated with a sigh. “Me and Neil.”

“I don’t understand it,” is all Kevin replies, because, really, he’s not all too sure.

“Understand what?”

“Any of it. It’s a lot to process.” Andrew nods as Kevin finishes, despite the answer being indisputably lame.

“It’s your turn.”

“Why him?” falls out of Kevin’s mouth again like a reflex. He watches as Andrew’s blank expression twitches and his eyes shut for a second in something akin to stoicism.

“He’s interesting.” Kevin knows how much that means from a perpetually bored man.

“He’s kind of messed up,” he replies hesitantly, though there’s really no “kind of,” - there’s not doubt that Neil’s messed up - and he isn’t sure whether his words are a challenge or a disagreement.

There’s something almost wistful in Andrew’s eyes. “Exactly.”

Kevin gets that, too. The reason things have always worked with Thea, even when others told him, told both of them , that they shouldn’t, is because she always got it. She knew what it was like to be a Raven, she knew the complicated relationship he had with Riko and the Moriyamas, she never judged, never told him his reactions were gratuitous or invalid, she just understood .

Understanding, true understanding, is unparalleled in rarity, and perhaps the most coveted trait of all.

“Why alcohol?” interrupts Kevin from his thoughts, and it takes him a moment longer than it should to process that it’s Andrew’s turn again.

“What?” Kevin asks, wrinkling up his face.

“You could have any coping mechanism you wanted: drugs, self-harm, running yourself to the bone, food addiction, therapy, adult colouring books…” he lists off, his eyes infinitesimally lighter than usual, and Kevin resists the urge to roll his eyes, because of course the only person who can amuse Andrew Minyard is Andrew Minyard. “Why alcohol?” he repeats.

“It’s the only thing that can make me forget.”

“There are drugs that could do that much easier,” Andrew replies, but there are lines in his forehead as he tacks on “probably.”

“After Seth and Aaron,” Kevin responds cautiously, “and you – cracker dust is the worst I swore I’d ever do. And that–” he pauses again, mind casting him back to nights at Eden, panic attacks in toilet stalls and the burn in his throat that leaves his brain null and void of all things Evermore. “–It’s not enough on its own.”

“It’s weak. And unhealthy.”

“I know.” He replies, and there’s something cold and cumbersome building up at the pit of his stomach as the topic is stretched out like an elastic band, millimetres away from snapping or closing back in on itself, so he tries his hardest not to trip over words as they stumble out of his mouth. “It’s my turn again. How does it work - you and him - after everything? Your past. How do you–”

“No.” Andrew cuts him off, fists clenching tighter around the cutlery in his hands. “You don’t get to ask that. Something else.”

Kevin doesn’t say sorry, but his face does, even if there’s something about pulling a reaction out of Andrew that sets his nerves on fire. “What are you scared of?”

Andrew blinks at him once, empty composure regained. “Heights.”

Kevin’s face wrinkles up. How can a man who has spent so long mocking Kevin for his fears of the Moriyamas, of the Ravens, of death , be afraid of something so trivial, something that is a fear of death, in a way, in itself. “I thought you said you weren’t afraid of death.”

“I’m not.” Andrew replies, a hint of a sneer on his face as he adds “And I hate that word.”

“Afraid?” Kevin asks, shrugging when Andrew nods. “If you’re not afraid of death, what is it about heights that you’re scared of?”

“Falling.” Andrew replies hollowly, and Kevin’s about to ask more, about to ask about how he can go to a rooftop so often with Neil - does Neil know? - when the conversation is interrupted by the sound of a key in the lock, and the two boys shift around just in time to watch a drenched Neil, looking like he’s just taken a fully-clothed shower, stumble through the door, flanked by Dan and Allison, both also varying levels of waterlogged.

As the girls immediately make their way over to the excess of food lying on the table, eyes wide and begging Andrew and Kevin to let them have some, Neil slides effortlessly into the space between them and turns to Andrew, who tentatively reaches out towards him and ruffles a hand through his hair, watching as Neil slides his soiled jacket off and finally wiping his now wet hand on Neil’s shirt to dry it.

The sides of Neil’s mouth twitch and Kevin battles with the urge to turn away, to leave.

“There’s enough food there to feed a small army,” Neil mutters, low enough that the words were really meant only for Andrew, and softer than Kevin’s ever heard. It’s more than slightly disconcerting.

“You’re a small army,” Andrew retorts, only Neil must be hearing something else completely in that, because next thing he knows, Neil’s turned around to face the girls who are still fawning over the makeshift banquet.

“Invite the rest of the team and you can help yourselves,” he states, watching with eyes showing something reminiscent of fondness as Allison immediately pulls her phone out and Dan digs through their drawers for extra cutlery.

Neil turns back to Andrew, the ghost of a smile hanging from his mouth fading after a second, face wrinkling up.

“Isn’t that sweater mine?”

Kevin’s mind may say “Disgusting,” but he can feel the sides of his mouth quirk upwards as he finds Andrew’s face encrusted with crumbs of fear like he’s tumbling, freefalling, into an abyss.

#the foxhole court#tfc#all for the game#aftg#aftgexchange#my writing#andreil#kevin day#andrew minyard#neil josten#aftg fic#tfc fic#writing#all for the game fic#queen of being the last person ever to do things#look it's not my fault my wifi is shitty

970 notes

·

View notes

Text

Going home.

I would never blame my mother for hiding the truth from me; I’m not sure I could have handled the nagging worry, the meditating on mortality, the sheer nostalgia, not when I was mid exam season anyway. Education first, there’s a principle my parents brought with them from India. So she bore the truth on her shoulders alone, and I was none the wiser until long after exams finished, when I moved back home for summer.

I didn’t realise the truth when we left. During the flight, I was thinking about which movie to watch and how much shopping we’d have time for. When we touched down in Kolkata, the dark part of the night and the oppressive heat welcoming us back like estranged children, I was overwhelmed with warm embraces and fatigue. Even when we reached the flat, the open door beckoning us back home, I was in a bubble of ignorant bliss. I had always been a fan of plans, and I had one: fly out, see your grandad, nurse him back to health, and be back in the UK in time for your brother’s graduation.

The façade cracked the next day.

When I woke, Dada was in his favourite armchair with my uncle sat beside him. His eyes were bright when he recognised me, brighter still when he began to ramble about how proud he was. He told us - for maybe the hundredth time - how he grew up a widow’s son, a village boy, a stereotype of abject poverty, and now he had grandchildren graduating from some of the best universities in the world. His eyes misted and I grasped his swollen, papery hand, comfortable in my knowledge that this was the greatest man I had ever known, and that I couldn’t imagine what he had gone through to provide the comfortable London upbringing I took for granted.

My grandfather was a proud man. When I was eleven, I was left at home with him and given strict instructions on giving him dinner and helping him to bed. I still remember walking downstairs to find him doing the washing up because he wanted to look after me more than I needed to look after him; that was the kind of proud my grandfather was. So it hurt when, at lunch, I watched the woman who cooked for him spoon mushy, overcooked rice into his lax mouth, remind him to swallow, pour water down afterwards. At least when you spoon feed a child you know they understand that they’re eating; with him, I wasn’t so sure.

After lunch he dozed whilst we replayed one of his old favourite movies, one he learned to love during his years in London. He slept in a state that we couldn’t fully wake him from. When his eyes flickered open there was no recognition in them anymore, he was lost in some past world, where a young man emigrated with his family and discovered English films for the first time, perhaps. I tried to doze too, but every time my eyes closed I found myself tearing up, knowing that he would have hated this, hated how he was babied and incapable and worst of all, upsetting us, his family. I was a pendulum, swinging from hope to misery: he’ll get better to he’s never been worse.

‘It’s been a good day,’ said my mother, from the other side of the sofa.

And the façade began to crack.

If this was a good day, what would a bad day look like? How could it be a good day when he couldn’t walk by himself, couldn’t remember if he’d already showered, couldn’t even swallow his water without someone holding his mouth shut? He didn’t know we’d brought him crumpets and English mustard, he barely knew we’d brought ourselves. If this was a good day, my God, it could get so much worse.

~

‘Wake up, I think we might have to call an ambulance.’

I shot up, wiping sleep from my eyes, my jetlag-induced nap suddenly seeming irresponsible.

‘What?’

‘It’s Dada, he can’t breathe, I think we have to call an ambulance,’ my brother repeated from the doorway. How had he gone from might to have to so quickly?

‘I’m coming, one second.’ I threw on a dress and half-ran the few steps to Dada’s room. He was sat doubled over, his breath ragged gasps, his body shaking, supported by my mother and brother and a second later, myself. If we’d let go he’d fall, and it terrified me that I didn’t know if he’d be able to get back up.

‘I don’t know what to do,’ Ma whispered. I stared at her blankly, the shock setting in. ‘Do we call an ambulance? Or should we…do we just make him comfortable?’

I wasn’t sure when I’d started crying but there were teardrops on my cheeks now. I felt like a petulant toddler, all I wanted was to throw a tantrum. This was my Dada - he had to get better, he wasn’t allowed to be like this. He had to get better so that he could come to graduation and puja and my wedding, so that he could tell me his stories, over and over, for the rest of my life, or at least for a little while longer.

‘No,’ I said. ‘No, maybe I’m selfish, but I’m not ready yet. Call the ambulance Ma.’ As she pulled out her phone, I kissed my grandfather’s forehead and began to pray away the last of my hope.

~

It was a good hospital, one of the best in India. The bureaucracy was awful, too many forms, not enough organisation, queues that lasted hours, but the doctors were excellent and that was what mattered. It was somewhere around the third or fourth cup of masala cha, with Dada two floors away in the ICU, surrounded by strangers, that I realised he would never be my grandfather again, that we’d flown thousands of miles not to help, but to say goodbye. I would have cried if I had any tears left.

He hated hospitals, ever since he lost his wife in one, hated the tubes and the smell and the way you always seemed to be waiting. It was like I could feel his pain, his frustration, how he just wanted to go home. I wasn’t sure if home was the flat we’d carried him out of on a stretcher, or somewhere much further away, where old friends were waiting to see him again.

I hated everything about the tube in his throat. I hated what it represented, how uncomfortable it must have made him, how little he tried to breathe without it. It seemed natural then, to get rid of it. No extreme measures is what Ma said, how the doctors phrased it, but we knew what it really meant when we signed the DNR. It may have been Ma’s signature, but my brother and I made that decision too. I considered it a silver lining that we could do that for her.

That first night that he was breathing by himself, I didn’t leave his side. I was too scared, in spite of my hunger, my nicotine craving, my need for a shower and a proper bed. When I was finally coaxed to get food and air it was only after I had whispered in his good ear that I would understand if he went without me, and that it would be okay, I just wanted him to be at peace.

Stubborn old git.

He lasted days. He lasted so many days that I began to pray that God would take him soon. I sat in the rain and stared at the heavens and begged them to tell us what he was waiting for, why he was dragging out his suffering. We were ready, I cried, he could go now, he’d done all he needed to.

Eventually, we decided to take him home. We hadn’t expected him to last more than a few hours, let alone most of a week. Maybe he was just waiting to go home. It had only been a few days since he’d been in the flat, but wheeling him back in on his hospital-prescribed bed, it felt like a lifetime ago. We settled him in the living room, and he turned his head and clasped his hands towards the portrait on the wall.

‘He’s praying!’ cried my uncle, ‘Look, he’s praying to his wife!’

I gripped my mother’s hand and blinked away the tears that came from being less naïve than him, and from knowing he couldn’t pray if he wanted to, not anymore.

~

‘Guys, can you help? I – I don’t know if he’s breathing.’

For the second time that week I was slapped out of sleep by the horror of reality. I don’t know if he was alive when Ma asked, or when I put my hand against his mouth to feel his breath, but by 6.07 a.m. I realised he’d finally gone. I was so relieved I felt weightless, shock keeping the grief at bay while we made tea and called the doctors and arranged a slot at the crematorium. It was strange, even after the doctor signed the death certificate it didn’t feel real.

One of his last wishes was that he didn’t want a hearse; he was a village lad, a traditional Indian man at heart, and he wanted to go the proper, old-fashioned way, up on shoulders. He looked beautiful, painted and dressed up and covered in flowers, finally peaceful. I’m not sure women are supposed to carry dead bodies, and I knew if I asked permission I would be told I was too weak, my sari too pretty to ruin, so I didn’t ask; I stepped into place between my brother and my cousin and felt his weight on my shoulder, and I smiled. I felt powerful as we walked, for once at peace with my tumultuous dual identity – today, I was Indian, I was the granddaughter of this incredible man, and the pride shone out of me.

I saw him put into the fire. Saw his name flash up on the screen, N. N. Mukherjee. Saw his ashes afterwards, carried the clay pot into the Ganges. I walked into a flat he’d never sit in again, consoled people he’d never see again, placed the glasses he’d never use again on a shelf to gather dust. Maybe it was then, or on the plane ride home, or maybe it was six months later when I understood why Ma cried over Colman’s English mustard in the supermarket. Maybe it was when I wanted to call and tell him about university, or when I found the postcard that I never got around to sending him. Maybe it was all at once, maybe it was gradual, maybe it never stops. But my world has seemed a little darker after that, a little less purposeful, and a little more scary; so I look to the heavens, and I hope he’s watching, and I thank the gods for the twenty years I got with the greatest man I could ever know.

~

Somewhere far away, a woman in her fifties kneads dough for roti, sat outside in the warm dusk. Her hair is long and dark, woven with grey, her sari pale and loose. She turns, as if hearing something alarming, rises and squints into the sunset, trying to discern something in the distance. Her face breaks into a smile it hasn’t known for a long time, and she calls out to the others. They come running, barefoot and dusty, little boys and old men leaning on sticks, women with tight plaits and youths with ink-stained fingers. They stand with her, and they watch, and they wait, and they know.

He’s come home.

0 notes