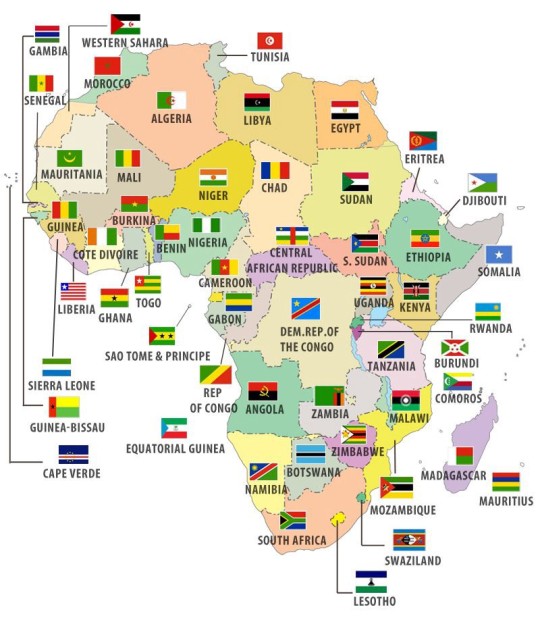

#Economic Community of Central African States

Text

The African Union and the Regional Economic Communities

View On WordPress

#African Union#Arab Maghreb Union#Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa#Community of Sahel-Sahara States#East African Community#Economic Commision Of West African States#Economic Community of Central African States#Intergovernmental Authority on Development#International Confernce on the Great Lakes Region#Regional Economic Communities#Southern African Development Community

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kwanzaa:

Kwanzaa, an annual holiday celebrated primarily in the United States from December 26 to January 1, emphasizes the importance of pan-African family and social values. It was devised in 1966 by Maulana Karenga, Inspired by Africa’s harvest celebrations, he decided to develop a nonreligious holiday that would stress the importance of family and community while giving African Americans an opportunity to explore their African identities. Kwanzaa arose from the black nationalist movement of the 1960s and was created to help African Americans reconnect with their African cultural and historical heritage. The holiday honors African American people, their struggles in the United States, their heritage, and their culture. Kwanzaa's practices and symbolism are deeply rooted in African traditions and emphasize community, family, and cultural pride. It's a time for reflection, celebration, and the nurturing of cultural identity within the African American community.

Kwanzaa is a blend of various African cultures, reflecting the experience of many African Americans who cannot trace their exact origins; thus, it is not specific to any one African culture or region. The inclusiveness of Kwanzaa allows for a broader celebration of African heritage and identity.

Karenga created Kwanzaa during the aftermath of the Watts riots as a non-Christian, specifically African-American, holiday. His goal was to give black people an alternative to Christmas and an opportunity to celebrate themselves and their history, rather than imitating the practices of the dominant society. The name Kwanzaa derives from the Swahili phrase "matunda ya kwanza," meaning "first fruits," and is based on African harvest festival traditions from various parts of West and Southeast Africa. The holiday was first celebrated in 1966.

Each day of Kwanzaa is dedicated to one of the seven principles (Nguzo Saba), which are central values of African culture that contribute to building and reinforcing community among African Americans. These principles include Umoja (Unity), Kujichagulia (Self-Determination), Ujima (Collective Work and Responsibility), Ujamaa (Cooperative Economics), Nia (Purpose), Kuumba (Creativity), and Imani (Faith). Each family celebrates Kwanzaa in its own way, but Celebrations often include songs, dances, African drums, storytelling, poetry readings, and a large traditional meal. The holiday concludes with a communal feast called Karamu, usually held on the sixth day.

Kwanzaa is more than just a celebration; it's a spiritual journey to heal, explore, and learn from African heritage. The holiday emphasizes the importance of community and the role of children, who are considered seed bearers of cultural values and practices for the next generation. Kwanzaa is not just a holiday; it's a period of introspection and celebration of African-American identity and culture, allowing for a deeper understanding and appreciation of ancestral roots. This celebration is a testament to the resilience and enduring spirit of the African-American community.

"Kwanzaa," Encyclopaedia Britannica, last modified December 23, 2023, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Kwanzaa.

"Kwanzaa - Meaning, Candles & Principles," HISTORY, accessed December 25, 2023, https://www.history.com/topics/holidays/kwanzaa-history.

"Kwanzaa," Wikipedia, last modified December 25, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kwanzaa.

"Kwanzaa," National Museum of African American History and Culture, accessed December 25, 2023, https://nmaahc.si.edu/explore/stories/kwanzaa.

"The First Kwanzaa," HISTORY.com, accessed December 25, 2023, https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/the-first-kwanzaa.

My Daily Kwanzaa, blog, accessed December 25, 2023, https://mydailykwanzaa.wordpress.com.

Maulana Karenga, Kwanzaa: A Celebration of Family, Community and Culture (Los Angeles, CA: University of Sankore Press, 1998), ISBN 0-943412-21-8.

"Kente Cloth," African Journey, Project Exploration, accessed December 25, 2023, https://projectexploration.org.

Expert Village, "Kwanzaa Traditions & Customs: Kwanzaa Symbols," YouTube video, accessed December 25, 2023, [Link to the specific YouTube video]. (Note: The exact URL for the YouTube video is needed for a complete citation).

"Official Kwanzaa Website," accessed December 25, 2023, https://www.officialkwanzaawebsite.org/index.html.

Michelle, Lavanda. "Let's Talk Kwanzaa: Unwrapping the Good Vibes." Lavanda Michelle, December 13, 2023. https://lavandamichelle.com/2023/12/13/lets-talk-kwanzaa-unwrapping-the-good-vibes/.

301 notes

·

View notes

Text

Okay I Could do work but instead I'm going to write about the time shostakovich had the worst time in america

(So, despite the clickbaity title, this will be more of a serious post. I wrote about the topic a few years ago on Reddit , and I'll be citing a lot of the same sources as I cited there, because there are some good ones, along with some new information I've gathered over the years. This was going to be a video essay on my youtube channel, but I sort of kept putting it off.)

The Scientific and Cultural Congress for World Peace, held in New York in 1949, is a particularly fascinating event to study when it comes to researching Shostakovich because of just how divisive it was. True, the event itself, which only lasted a few days, doesn’t get as much spotlight as the Lady Macbeth scandal or the posthumous “Shostakovich Wars,” but you’ll find that when reading about the Peace Conference, as I’ll be referring to it here for the sake of brevity, many of the primary accounts of it never quite tell the full story. The Peace Conference was held during a volatile time, both in Soviet and American politics, as Cold War tensions were on the rise and an ideological debate between capitalism and communism gradually extended to become the focus of seemingly every factor of life- not just politics and economics, but also the sciences, culture, and the arts.

While artists on both sides were frequently cast in different roles in order to create or destroy the image of Soviet or American cultural and ideological superiority, the image either government sought to cast was sometimes contradictory with the sentiments of the artists themselves. For instance, while the CIA-founded Congress of Cultural Freedom (CCF) sent African American jazz musician Louis Armstrong on various tours around the world to promote jazz as American culture and dispel perceptions of racism in America, Armstrong canceled a trip to the Soviet Union in order to protest the use of armed guards against the integration of Black students at Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas, in 1957. Meanwhile, the Soviet government’s use of international diplomatic missions by artists as cultural warfare also reflected a desire to portray themselves as the dominant culture, despite the tensions and complications that existed for artists at home. When the Soviet Union sent Dmitri Shostakovich to New York in March 1949 for the Peace Conference, such cultural contradictions are why the conference occurred the way it did, and why Shostakovich’s image has received so much controversy, both in Russia and in the west.

If you’re familiar with Soviet history, you may be familiar with the term Zhdanovshchina, which refers to a period of time between 1946 and 1948 in which Andrei Zhdanov, the Central Committee Secretary of the Soviet Union, headed a number of denunciations against prominent figures in the arts and sciences. Among musicians, Shostakovich was one of the most heavily attacked, likely due to his cultural standing, with many of his pieces censored and referred to as “formalist,” along with his expulsion from his teaching positions at the Moscow and Leningrad conservatories. During this time, Shostakovich often resorted to writing film and ideological music in order to make an income.

Meanwhile, in the United States, as fears of nuclear war began accumulating, peace movements between the two superpowers were regarded more and more as pro-Communist, an opinion backed by the House Committee of Un-American Activities (HUAC). The Waldorf-Astoria Peace Conference, to be held from March 25-27th 1949, was organized by the National Council of Arts, Sciences, and Professions, a progressive American organization, and was to feature speeches held by representatives of both American and Soviet science and culture. Harlow Shapely, one of the conference’s organizers, stated that he intended for the conference to be “non-partisan” and focused on American and Soviet cooperation.

On the 16th of February, 1949, Shostakovich was chosen to be one of the six Soviet delegates to speak at the conference. This was largely due to his fame in the west, where both his Seventh and Eighth Symphonies met a mostly positive reception. Shostakovich initially did not want to go to the conference, stating in a letter to the Agitprop leader Leonid Ilichev that he was suffering from poor health at the time and wasn’t feeling up to international travel and performances. He also said that if he were to go, he wanted his wife Nina to be able to accompany him, but he ended up being sent to New York without any members of his family- perhaps to quell concerns of defection (recall the amount of artists who defected around the time of the 1917 revolution, including notable names such as Rachmaninov and Heifetz).

Stalin famously called Shostakovich on the phone that same day to address the conference, and again, Shostakovich told him he couldn’t go, as he was feeling unwell. Sofia Khentova’s biography even states that Shostakovich actually did undergo medical examinations and was found to be sick at the time, but Stalin's personal secretary refused to relay this information. Shostakovich's close friend Yuri Levitin recalls that when Stalin called Shostakovich on the phone to ask him to go to the conference (despite the fact he had been chosen to go in advance), Shostakovich offered two reasons as to why he couldn't go- in addition to his health, Levitin claims that Shostakovich also cited the fact that his works were currently banned in the Soviet Union due to the Zhdanov decree, and that he could not represent the USSR to the west if his works were banned. While accounts of the phone call vary, the ban on Shostakovich's works was indeed lifted by the time he went to New York for the conference.

When Shostakovich arrived in New York, general anti-Communist sentiment from both Americans and Soviet expatriates, as well as media excitement, resulted in a series of protests in front of the Waldorf Astoria hotel where the conference was to be held, with some of the protesters directly referencing Shostakovich himself, as he was the most well-known Soviet delegate on the trip. In 1942, Shostakovich's 7th ("Leningrad") Symphony was performed in the United States under Toscanini and the NBC Symphony Orchestra to high acclaim, helping to promote the idea of allyship with the Soviet Union in the US during the war, and Americans were aware of the Zhdanov denunciations in 1948, as well as the previous denunciations that Shostakovich had suffered in 1936 as a result of the scandal surrounding his opera "Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District." So by 1949, many people in American artistic circles had a sympathetic, if not completely understanding, view of Shostakovich during the birth of the Cold War. They viewed him as a victim of Communism and the Soviet state, who was forced to appease it in order to stay in favor, and as a result, could potentially voice his dissent with the system once in the west. Pickets visible in footage from the protests outside the Waldorf Astoria carried slogans such as "Shostakovich, jump thru [sic] the window," a likely reference to Oksana Kosyankina, a Soviet schoolteacher who had reportedly jumped out of a window in protest (although the details of this story would be found to be highly dubious). Meanwhile, another sign read "Shostakovich, we understand!," a statement that would prove to be deeply ironic.

At the conference itself, Shostakovich did not jump through the window, nor did he attempt any form of dissent. Instead, an interpreter read through a prepared speech as he sat on stage in front of a crowd of about 800. The speech praised Soviet music, denounced American "warmongering," and claimed that Shostakovich had accepted the criticism of 1948, saying it "brought his music forward."

Many in the audience could see that Shostakovich was visibly nervous- he was "painfully ill at ease," and Nicholas Nabokov (brother of the writer Vladimir Nabokov) remarked that he looked like a "trapped man." Arthur Miller recalled he appeared "so scared." As they noticed how nervous he looked, some of those in attendance sought to make a demonstration of him in order to illustrate Soviet oppression in contrast to the freedoms supposedly enjoyed by American artists, asking him intentionally provocative questions that they knew he would not be able to answer truthfully. From Nicholas Nabokov:

After his speech I felt I had to ask him publicly a few questions. I had to do it, not in order to embarrass a wretched human being who had just given me the most flagrant example of what it is to be a composer in the Soviet Union, but because of the several thousand people that sat in the hall, because of those that perhaps still could not or did not wish to understand the sinister game that was being played before their eyes. I asked him simple factual questions concerning modern music, questions that should be of interest to all musicians. I asked him whether he, personally, the composer Shostakovich, not the delegate of Stalin’s Government, subscribed to the wholesale condemnation of Western music as it had been expounded daily by the Soviet Press and as it appeared in the official pronouncements of the Soviet Government. I asked him whether he, personally, agreed with the condemnation of the music of Stravinsky, Schoenberg, and Hindemith. To these questions he acquiesced: ‘Yes,’ he said, ‘I completely subscribe to the views as expressed by … etc….’ When he finished answering my questions the dupes in the audience gave him a new and prolonged ovation.

During the discussion panel on March 26th, music critic Olin Downes delivered yet another provocative statement towards Shostakovich:

I found both of your works [the 7th and 8th Symphonies] too long, and I strongly suspected in them the presence of a subversive influence—that of the music of Gustav Mahler.

For Shostakovich, and anyone knowledgeable of Soviet politics and music at the time, it's not hard to see why Downes had explicitly mentioned Mahler. Gustav Mahler (1860-1911) was a highly influential composer when it came to 20th century western music, particularly with regards to the avant-garde movement pioneered by the Second Viennese School- Arnold Schoenberg, Anton Webern, and Alban Berg. Shostakovich was also heavily influenced by Mahler, but such influences were frowned upon in the mid-30s to 50s Soviet Union. Mahler's style was decidedly more "western," and it's potentially for this reason that Shostakovich's 4th Symphony- perhaps his most "Mahlerian," was withdrawn from performance before its premiere in 1936, having followed the "Lady Macbeth" denunciations. To tie Shostakovich to Mahler would be to point out his direct western influences, while he was being made to issue statements that rejected them. During his speech, Shostakovich made statements criticizing Stravinsky and Prokofiev- two composers who had emigrated and adopted western-inspired neoclassical styles (although Prokofiev returned to the Soviet Union in 1936). Stravinsky had taken insult to Shostakovich's comments against him, and carried an animosity towards Shostakovich that appeared once again in their meeting in 1962, according to the composer Karen Khachaturian.

On the last day of the conference, March 27th, Shostakovich performed the second movement of his Fifth Symphony on piano at Madison Square Garden to an audience of about 18,000, and had received a massive ovation, as well as a declaration of friendship signed by American composers such as Bernstein, Copland, Koussevitzky, and Ormandy. He returned to the Soviet Union on April 3.

In addition to the 1948 denunciations, in which Shostakovich was pressured to make public statements against his own works, the likely humiliation he endured at the 1949 conference played a role in cementing his dual "public" and "private" personas. For the rest of his life, Shostakovich displayed mannerisms and characteristics at official events that were reportedly much different from those he displayed among friends and family. For the public, and for researchers after his death, it became difficult to determine which statements from him reflected his genuine sentiments, and which ones were made to appease a wider political or social system.

Both the Soviet Union and the west had treated Shostakovich as a means of legitimizing their respective ideologies against one another, a trend that continued long after his death in 1975 and the fall of the USSR in 1991. The publication of his purported memoirs, "Testimony," allegedly transcribed by Solomon Volkov, fueled this debate among academics and artists, becoming known as the "Shostakovich wars." The feud over the legitimacy of "Testimony," however, stood for something much larger than the credibility of an alleged historical document- as historians and musicologists debated whether or not it was comprised of Shostakovich's own words and sentiments towards the Soviet Union, its political systems, and its artistic spheres, they were largely seeking to prove the credibility of their stances for or against Soviet or western superiority. "Testimony" helped evolve the popular western view of Shostakovich as well, from a talented but helpless puppet at the hands of the regime, to a secret dissident bravely rebelling against the system from inside.

Modern Shostakovich scholars, however, will argue that neither of these views are quite true- as more correspondence and documents come to light, and more research is conducted, a more complete view of Shostakovich has been coming into focus over the past decade or so. Today, many academics tend to view Shostakovich and the debate over his ideology with far more nuance- not as a cowardly government mouthpiece or as an embittered undercover rebel, but as a multifaceted person who made difficult decisions, shaped by the varying time periods he lived in, whose actions were often determined by the shifting cultural atmospheres of those time periods, along with his own relationships with others and the evolution of his art. We can be certain Shostakovich did not approve of Stalin's restrictions on the arts- his posthumous work "Antiformalist Rayok," among other pieces of evidence from people he knew, makes that very clear- but many nuances of his beliefs are still very much debated. There has also been a shift away from judging Shostakovich's music based on its merit as evidence in the ideological dispute, and rather for its quality as artwork (something I'm sure he would appreciate!). As expansive as Shostakovich research has become, one thing has become abundantly clear- none of us can hope to truthfully make the statement, "Shostakovich, we understand."

Sources for further reading:

Articles:

Shostakovich and the Peace Conference (umich.edu)

Louis Armstrong Plays Historic Cold War Concerts in East Berlin & Budapest (1965) | Open Culture

Biographical and Primary Sources:

Laurel Fay, "Shostakovich, a Life"

Pauline Fairclough, "Critical Lives: Dmitry Shostakovich"

Elizabeth Wilson, "Shostakovich, a Life Remembered"

Mikhail Ardov, "Memories of Shostakovich"

HUAC Report on Peace Conference

Video Sources and Historic Footage:

Arthur Miller on the Conference

"New York Greets Mr. Bevin and Peace Conference Delegates"

"Shostakovich at the Waldorf"

"1949 Anti Communism Protest"

"Battle of the Pickets"

#shostakovich#dmitri shostakovich#long post#history#soviet history#classical music#music history#1940s history#new york#russian history#cold war#composers#classical composer#my god this feels good to get out of my drafts

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Florida quietly removes LGBTQ+ travel info from state website

FILE - Hundreds of people line Central Avenue and cheer during the 10th Annual St. Pete Pride Street Festival & Promenade in St. Petersburg, Fla. on June 30, 2012.

TALLAHASSEE, Fla. (AP) — Key West, Fort Lauderdale, Wilton Manors and St. Petersburg are among several Florida cities that have long been top U.S. destinations for LGBTQ+ tourists. So it came as a surprise this week when travelers learned that Florida's tourism marketing agency quietly removed the “LGBTQ Travel” section from its website sometime in the past few months.

Business owners who cater to Florida's LGBTQ+ tourists said Wednesday that it marked the latest attempt by officials in the state to erase the LGBTQ+ community. Republican Gov. Ron DeSantis previously championed a bill to forbid classroom instruction on sexual orientation and gender identity, and supported a ban on gender-affirming care for minors, as well as a law meant to keep children out of drag shows.

“It's just disgusting to see this,” said Keith Blackburn, who heads the Greater Fort Lauderdale LGBT Chamber of Commerce. “They seem to want to erase us.”

The change to Visit Florida's website was first reported by NBC News, which noted a search query still pulls up some listings for LGBTQ+-friendly places despite the elimination of the section.

John Lai, who chairs Visit Florida's board, didn't respond to an email seeking comment Tuesday. Dana Young, Visit Florida's CEO and president, didn't respond to a voicemail message Wednesday, and neither did the agency's public relations director.

Visit Florida is a public-private partnership between the state of Florida and the state's tourism industry. The state contributes about $50 million each year to the quasi-public agency from two tourism and economic development funds.

Florida is one of the most popular states in the U.S. for tourists, and tourism is one of its biggest industries. Nearly 141 million tourists visited Florida in 2023, with out-of-state visitors contributing more than $102 billion to Florida’s economy.

Before the change, the LGBTQ+ section on Visit Florida's website had read, “There’s a sense of freedom to Florida’s beaches, the warm weather and the myriad activities — a draw for people of all orientations, but especially appealing to a gay community looking for a sense of belonging and acceptance.”

Blackburn said the change and other anti-LGBTQ+ policies out of Tallahassee make it more difficult for him to promote South Florida tourism since he encounters prospective travelers or travel promoters who say they don't want to do business in the state.

Last year, for instance, several civil rights groups issued a travel advisory for Florida, saying that policies championed by DeSantis and Florida lawmakers are “openly hostile toward African Americans, people of color and LGBTQ+ individuals.”

But visitors should also understand that many Florida cities are extremely inclusive, with gay elected officials and LGBTQ+-owned businesses, and they don't reflect the policies coming from state government, Blackburn added.

“It’s difficult when these kinds of stories come out, and the state does these things, and we hear people calling for a boycott,” Blackburn said. “On one level, it’s embarrassing to have to explain why people should come to South Florida and our destination when the state is doing these things.”

#Florida quietly removes LGBTQ+ travel info from state website#florida#lgbtq#desatan#hateful#pride#lgbtq+#travel advisory for florida#another travel advisory for florida#civil rights

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Seattle From the Margins: Exclusion, Erasure, and the Making of a Pacific Coast City

Megan Asaka (2022)

"From the origins of the city in the mid-nineteenth century to the beginning of World War II, Seattle's urban workforce consisted overwhelmingly of migrant laborers who powered the seasonal, extractive economy of the Pacific Northwest. Though the city benefitted from this mobile labor force that consisted largely of Indigenous peoples and Asian migrants, municipal authorities, elites, and reformers continually depicted these workers and the spaces they inhabited as troublesome and as impediments to urban progress. Today the physical landscape bears little evidence of their historical presence in the city. Tracing histories from unheralded sites such as labor camps, lumber towns, lodging houses, and so-called slums, Seattle from the Margins shows how migrant laborers worked alongside each other, competed over jobs, and forged unexpected alliances within the marine and coastal spaces of the Puget Sound. By uncovering the historical presence of marginalized groups and asserting their significance in the development of the city, Megan Asaka offers a deeper understanding of Seattle's complex past.

This is EXCELLENT!

Other books referenced by Asaka.

The Forging of a Black Community: Seattle’s Central District from 1870 through the Civil Rights Era (Second Edition)

By Quintard Taylor (2022)

Seattle's first black resident was a sailor named Manuel Lopes who arrived in 1858 and became the small community's first barber. He left in the early 1870s to seek economic prosperity elsewhere, but as Seattle transformed from a stopover town to a full-fledged city, African Americans began to stay and build a community. By the early twentieth century, black life in Seattle coalesced in the Central District, a four-square-mile section east of downtown. Black Seattle, however, was never a monolith. Through world wars, economic booms and busts, and the civil rights movement, black residents and leaders negotiated intragroup conflicts and had varied approaches to challenging racial inequity. Despite these differences, they nurtured a distinct African American culture and black urban community ethos. With a new foreword and afterword, this second edition of The Forging of a Black Community is essential to understanding the history and present of the largest black community in the Pacific Northwest.

American Workers, Colonial Power Philippine Seattle and the Transpacific West, 1919-1941

by Dorothy B. Fujita Rony (2003)

Historically, Filipina/o Americans have been one of the oldest and largest Asian American groups in the United States. In this pathbreaking work of historical scholarship, Dorothy B. Fujita-Rony traces the evolution of Seattle as a major site for Philippine immigration between World Wars I and II and examines the dynamics of the community through the frameworks of race, place, gender, and class. By positing Seattle as a colonial metropolis for Filipina/os in the United States, Fujita-Rony reveals how networks of transpacific trade and militarism encouraged migration to the city, leading to the early establishment of a Filipina/o American community in the area. By the 1920s and 1930s, a vibrant Filipina/o American society had developed in Seattle, creating a culture whose members, including some who were not of Filipina/o descent, chose to pursue options in the U.S. or in the Philippines.

Fujita-Rony also shows how racism against Filipina/o Americans led to constant mobility into and out of Seattle, making it a center of a thriving ethnic community in which only some remained permanently, given its limited possibilities for employment. The book addresses class distinctions as well as gender relations, and also situates the growth of Filipina/o Seattle within the regional history of the American West, in addition to the larger arena of U.S.-Philippines relations.

90 notes

·

View notes

Text

The franc CFA (originally denoting Colonies françaises d’Afrique) is the official currency of Senegal and most other former French colonies in Africa, from before national independence through the present-day. This monetary system and its history are the subjects of a new book by Fanny Pigeaud and Ndongo Samba Sylla, Africa’s Last Colonial Currency (2021), translated by Thomas Fazi from a 2018 French edition. The book brings to the attention of Anglophone readers the peculiar institutions through which the French Republic continues to exercise colonial rule over nominally independent African states. France’s recent “counterterrorism” operations across the Sahel region (supported and rivaled in scope by the United States’ Africa Command, AFRICOM) represent only one phase in what the Black Alliance for Peace (2020) has called France’s “active and aggressive military presence in Africa for years.” Aggression has often had monetary motivations, and control has often exceeded aggression. One of Pigeaud and Sylla’s commitments and achievements is to show how “French ‘soft’ monetary power is inseparable from its ‘hard’ military power” (2021: 99). In their telling, the CFA franc has for decades been France’s secret weapon in “Françafrique,” the zone in Africa where France, its representatives, and its monetary system have never really left. [...]

---

The franc CFA was born in Paris on the 25th of December, 1945 [...]. The embattled empire was compelled to “loosen its grip” in Africa [...]. Consequently, argue Pigeaud and Sylla, the creation of the CFA franc was “actually designed to allow France to regain control of its colonies” (13). What Minister Pleven called generosity might better be called a swindle. [...] French goods-for-export, now priced in a devalued currency (made cheaper), would find easy markets in the colonies [...]. African goods - especially important raw materials, from uranium to cocoa, priced too expensively for domestic consumption [...] -- would find buyers more exclusively in France [...]. In effect, the new CFA monetary policies re-consolidated France’s imperial economy even as the monopoly regime of the colonial pact could be formally retired in recognition of demands for change from colonial subjects. [...] [T]he egalitarian parlance of community and cooperation modernized French colonial authority, making it more invisible rather than marking its end. [...]

---

Most importantly, France has held up a guarantee of unlimited convertibility between CFA francs and French currency [...]. CFA francs can only ever be converted into France’s currency [...] before being exchanged for other currencies [...]. In 1994, in conjunction with the International Monetary Fund and against the wishes of most African leaders, French authorities adjusted the franc zone exchange rate for the first time, devaluing the CFA franc by half. This blanket devaluation was the shock through which structural adjustment was forced upon Françafrique [...]. And the devaluation proved, to Pigeaud and Sylla, that France’s “‘guarantee of unlimited convertibility’ was an intellectual and political fraud” (74). Nevertheless, French authorities have continually held up - that is, brandished and exploited - this guarantee, without honoring it. [...] Pigeaud and Sylla do not mince words: “France uses its presumed role of ‘guarantor’ as a pretext and as a tool to blackmail its former colonies in order to keep them in its orbit, both economically and politically” (38). [...] In that respect, the CFA franc system has ensured [...] the stabilization of raw material exportation and goods importation, hierarchy and indirect rule, [...] accumulation and mass impoverishment, in short, the colonial order.

---

And all along, France has found - or compelled, coerced, and more-or-less directly put in place - useful political partners in Françafrique. [...]

The CFA franc has been central to the French strategy of decolonization-in-name-only. [...]

When and where demands for self-determination and changes to the monetary system (usually more minor than exit or abolition) have been strongest, from charismatic leaders or from below, they have been met with a retaliatory response from France and its African partners, frequently going so far as “destabilisation campaigns and even assassinations and coups d’état” (40). [...]

The first case is exemplary. In 1958, Ahmed Sékou Touré helped lead Guinea to independence [...]. Guinea was alone in voting down De Gaulle’s “Community” proposal [...], and [...] the new state established its own national currency and central bank by 1960. [...] [T]he decision was ultimately made to make Guinea a cautionary tale for the rest of Françafrique. French counter-intelligence officials plotted and hired out a series of mercenary attacks (“with the aim of creating a climate of insecurity and, if possible, overthrowing Sékou Touré,” recalled one such operative), in conjunction with “Operation Persil,” a scheme to flood the Guinean economy with false Guinean bills, successfully bringing about a devastating crash (43). [...] Yet, Sékou Touré was never removed, only ostracized - unlike Sylvanus Olympio in Togo or Modiba Keita in Mali, others whose (initially minor) desired changes to the CFA status quo were refused and rebuffed and who were then deposed in French-linked coups. [...]

So too the Cameroonian economist Joseph Tchundjang Pouemi, an even more overlooked figure since his death at the age of 47 in 1984. Pouemi’s experience working at the IMF [International Monetary Fund] in the 1970s led him to recognize that the leaders of the international monetary system would “repress any government that tries to offer their country a minimum of wellbeing” (60) and could do so especially easily in Françafrique because of the CFA franc.

---

All text above by: Matt Schneider. “Africa’s Last Colonial Currency Review.” Society and Space [Book Reviews section of the online Magazine format]. 29 November 2021. [Bold emphasis and some paragraph breaks/contractions added by me.]

74 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tamazight, the other prevalent first language in Morocco, is spoken by roughly 40-50% of the Moroccan population. Varieties of Tamazight in Morocco are generally considered lacking in social, cultural and economic capital and arguably comprise the most devalued language in Morocco (Ennaji 2005; Sadiqi 2007). They are associated with folklore, poverty, rurality and women (Hoffman 2006). In response to a long history of discrimination against Tamazight, the Moroccan King Mohammed VI created the Moroccan Royal Institute for Amazigh Culture charged with directing Tamazight language policy and cultural affairs. He also publicly recognized the Tamazight language as a valuable part of the cultural heritage of all Moroccans and adopted the Tifinagh writing system, an alphabetic system based on a 5,000 year old script, with which to teach and to write a standardized variety of Tamazight (Errihani 2006). According to the new constitution voted for on July 1, 2011, Tamazight is now also an official language alongside Standard Arabic. Moroccan Arabic, by contrast, was not recognized in the constitution.

Errihani (2006) argues that the new Tamazight language policy in Morocco is seen by many Moroccan intellectuals as merely a symbolic and political maneuver by the Monarchy to appear responsive to Western, pluralist, identity politics and discourses of minority rights. He warns it will be ineffective in either teaching Tamazight to Moroccan Arabic speaking children or raising the cultural and economic value of Tamazight language varieties more generally. Furthermore, he notes that Tamazight, while a mandatory school subject, is never the medium of education and that by taking effect only in public schools it targets the poor and disadvantaged disproportionately, since children of the elite tend to enroll in private French or English medium schools where State education policies have limited reach. My experiences visiting public schools in the central region of Morocco support this view. I repeatedly heard teachers complaining that they did not have the training necessary to teach Tamazight and Tifinagh and that the amount of time, when spent on the subject at all, would have been better put towards French or English. One school I visited in the region of Beni Mellal had placed all the Tamazight educational materials received by the government directly into storage, and years later had yet to utilize them because according to the director, the children’s parents were against the teaching of a standardized Tamazight to native Tamazight speaking children. They viewed the Tamazight standard developed by the Moroccan government as a fake and inauthentic language imposed upon them for political purposes.

— Jennifer Lee Hall, Debating Darija: Language Ideology and the Written Representation of Moroccan Arabic in Morocco (PhD dissertation), 2015, pp. 18-19.

Ennaji, Moha

2005 Multilingualism, Cultural Identity, and Education in Morocco. New York: Springer.

Errihani, Mohammed

2006 Language Policy in Morocco: Problems and Prospects of Teaching Tamazight. The Journal of North African Studies.

Hoffman, Katherine

2006 Berber Language Ideologies, Maintenance, and Contraction: Gendered Variation in the Indigenous Margins of Morocco. Language and Communication 26(2):144-167.

Sadiqi, F.

2007 The Role of Moroccan Women in Preserving Amazigh Language and Culture. Museum International 59(4):26.

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

Francophone Africa has experienced a series of coups since 2020. In Malitwice, followed by Guinea, Burkina-Faso, Niger, and finally Gabon. The coups raised concerns about the stability and democracy in the region.

In an interview with DW, Ingo Badoreck, from the Konrad Adenauer Foundation — affiliated with the German opposition party, the Christian Democratic Union of Germany (CDU), explained that while in Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger duly elected presidents were ousted from office by power-hungry military leaders taking advantage of a general sense of insecurity, the military government in Gabon appears to have ousted an autocratic despot.

50 years of the Bongo dynasty

For over half a century, the Bongo family used authoritarian methods to cling to power in the resource-rich Gabon. Omar Bongo was president from 1967 until he died in 2009. His 41 years in office was one of the longest of any head of state in Africa. He was succeeded in office by his son Ali Bongo. The Bongo clan's long reign and autocratic rule led to widespread dissatisfaction.

After Ali Bongo's controversial reelection in 2016, he brutally crushed anti-government protests, in which at least 27 people died.

On August 26, 2023, Gabon held another election. Official results certified a clear victory for Bongo, who was hoping to extend the family's rule to 55 years. Hardly anyone in the country considered the results credible. Four days later, on August 30, 2023, the military declared the election results null and void. They deposed Ali Bongo and appointed his cousin Brice Oligui Nguema interim president.

A promise of free and transparent elections in 2025

One year after the military seized power, there is a relatively clear roadmap for organizing the return to democratic forms of government. In the months following the coup, the transitional government organized an "inclusive national dialogue" open to all levels of civil society. One of the most important results was the introduction of a presidential system with a maximum of two seven-year terms in office. Plans are also in place to strengthen decentralization and citizen participation.

The transitional period until democratic elections are held has been set at 24 months, albeit with the possibility of an extension. While the military government in Gabon has promised to hold the elections in August 2025, there are still challenges ahead.

"There is still no concrete timetable for the presidential elections," Ingo Barodeck of the Konrad Adenauer Foundation said. "We now have to wait for very concrete plans from the Ministry of the Interior, which is now responsible, to hold these elections in a year." Barodeck said there are concerns that the uncertainty and the potential for logistical and political challenges could delay the return to democratic governance in Gabon.

Despite those fears, transitional ruler Oligui Nguema has repeatedly affirmed on the international stage that he would stick to this timetable. With his assurances, he ensured that Gabon's suspended Central African Economic Community ECCAS membership was reinstated in March. French President Emmanuel Macron later hosted him at a reception with military honors at the Elysee Palace.

Will Oligui Nguema cling to power?

Speculation is mounting in Gabon that General Oligui Nguema is using the transitional period to prepare his presidential candidacy. In an interview, political analyst Astanyas Bouka told DW that "his ambitions are great, and he tried from the outset to involve representatives of civil society in his transitional government to take the wind out of the opposition's sails."

"We are committed to the side of the transitional government in this transitional phase because we initiated this process from the beginning," Georges Mpaga, a well-known human rights activist in Gabon and a member of the transitional government's economic, social, and environmental council, told DW.

"Through our lobbying and protests, we contributed to dismantling the Bongo system even before the coup," Mpaga added. However, it remains to be seen what role civil society will play in the post-transition period.

A new era for disgruntled Gabonese

After the coup, there were scenes of jubilation on Gabon's streets. The youth demanded better living conditions and a fairer distribution of the country's wealth. According to World Bank data, per capita income in the oil-rich country was one of the highest in sub-Saharan Africa in 2021 at just over $4,500 (€4,056). However, a third of Gabon's 2.3 million people live below the poverty line.

The influential Catholic Church has thrown its weight behind the new transition rulers. Despite Gabon's secular constitution, the Church often influences political matters, as seen in the recent protests for transparent elections. Brice Oligui Nguema, the interim president, a devout Catholic, like three-quarters of Gabon's population, is seen as the 'dawn of a new era' by the Christian majority. This support adds a layer of legitimacy to the transition, reassuring the population about the country's direction.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Niger: Rights in Free Fall a Year After Coup

Crackdown on Opposition, Media; No Oversight of Military Spending

(Nairobi) – The military authorities in Niger have cracked down on the opposition, media, and peaceful dissent since taking power in a coup one year ago, Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch and the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH) said today.

They have arbitrarily detained former President Mohamed Bazoum, and at least 30 officials from the ousted government and people close to the deposed president, as well as several journalists. They have rejected oversight of military spending, contrary to claims to combat corruption. The Nigerien authorities should immediately release all those held on politically motivated charges; guarantee respect for fundamental freedoms, particularly the rights to freedom of expression, opinion, and association; and publicly commit to transparency and accountability in military spending.

“One year since the military coup, instead of a path toward respecting human rights and the rule of law, the military authorities are tightening their grip on opposition, civil society, and independent media,” said Samira Daoud, Amnesty International’s regional director for West and Central Africa. “Niger’s military authorities should release Bazoum as well as all those detained on politically motivated charges and ensure their due process rights.”

On July 26, 2023, Gen. Abdourahamane Tiani and other Nigerien army officers of the National Council for the Safeguard of the Homeland (Conseil national pour la sauvegarde de la patrie, CNSP) overthrew Mohamed Bazoum, elected as president in 2021, and arbitrarily detained him, his family, and several members of his cabinet. In response to the coup, the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) on July 30, 2023, imposed sanctions, including economic sanctions, travel bans, and asset freezes, on the coup leaders and on the country more generally. On August 22, 2023, the African Union suspended Niger from its organs, institutions, and actions. On January 28, 2024, Niger, Burkina Faso, and Mali announced they would leave ECOWAS, and on February 24, ECOWAS lifted the sanctions on Niger. [X]

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Economic Community of Central African States on Thursday called for the restoration of constitutional order in Gabon, as the African Union suspended the country following the military coup.

ECCAS, made up of 11 countries in the region and whose current chair is ousted Gabonese President Ali Bongo, said it condemned the use of violence to resolve political conflicts and gain access to power following Wednesday’s coup.

The statement called on “the political genius of the Gabonese people” to engage in dialogue and urged the authorities to “take all measures for a speedy return to constitutional order.”

ECCAS, based in the Gabonese capital of Libreville, also announced an imminent extraordinary summit of its members’ heads of state, although it did not specify a date.

31 Aug 23

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Setting Blurb: MacroCommunity Greater Somalia

The Somali Civil War reignited with the outbreak of the Third World War, with the breakaway East African Federation-backed Mogadishu government reasserting their claims over the breakaway Somaliland. The conflict spilled over into the Somali-speaking Ogaden in Ethiopia and Djibouti, and financial and military aid from the African Union and Arab League diminished as WWIII took its toll globally. The collapse of the United States and China caused a global wave of economic, political, and then societal collapse. The East African Federation withdrew from Somalia to maintain some semblance of stability on the home front, and the Mogadishu and Hargesia governments broke.

The generation of conflict that followed, known as the "Warlords' Wars", would see the emergence of protostates filling the vacuum created by the anti-climactic end of WWIII. Somalia's clans were quick to reassert themselves, and spent the Warlords period fighting for influence and territory. As the wars died down globally, a successor state to the Ethiopian government emerged to challenge the Somali clans of the Ogaden for control of the territory.

It was during this time that a growing alliance of warlords in the former United States, European Union, and China began approaching the remnants of ECOWAS and the East African Community to serve as springboards into incorporating the rest of the African continent. Fearing the new Ogaden War's potential spillover into eastern and central Africa resulted in a series of talks and border skirmishes that made Ethiopia and Somalia EAC protectorates (which was itself annexed into the Imperial League). Somalia retained the Ogaden (and Somali-majority areas in Kenya), and Ethiopia was placated with the annexation of Eritrea and non-Somali Djibouti.

The Eight Gobols: These eight provinces are the territory held by the extant clans and sub-clans that survived the Warlords' Wars period. The clans' territorial holdings were formally recognized by the early League government, and their leadership awarded collective governorship over the new MacroCommunity. Each Gobol is governed by a Xeer court, which oversees vocational councils (professions within the clan are held by one or more sub-clans) and maintains the clan militia.

Gosha Kaunti: The de facto capitol region of Greater Somalia, Gosha Kaunti is named for Somalia's Bantu-speaking minority. The Gosha have risen in prominence due to serving mediators for the clans around them (as their ancestors were not formally incorporated into the Somali clan system) should the Xeer courts be found unsatisfactory. The MacroCommunal governor's personal guards and a small detachment of Support Service Force security troopers help ensure that the clans find Gosha mediation to be more than satisfactory.

Land Force Demesne Djibouti: Carved out of the Somali speaking partition of Djibouti, this Land Force Demesne houses the East African third of Field Army Yellow's naval assets. Piracy still plagues the horn of Africa, with many in the Imperial Armed Forces believing that the pirates are receiving aid from the League's rivals.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

In the late 1990s, when I was a New York Times correspondent based in West Africa, international airline connections made passing through Paris a rite of both work and vacation. On one such visit, I received a shock that has stuck with me. As I approached a subway station not far from the Champs-Élysées, out of its stairwell came running two policemen, their guns drawn, as they pursued a young Black man whom they caught up to, badly manhandled, and then hauled away under arrest.

As someone who had grown up in Washington, D.C., and recently moved to Africa from New York City—or simply as someone who had watched U.S. local news broadcasts and grown up consuming his country’s violent small- and large-screen offerings—I had been trained to think that urban scenes such as these were a unique product of my own country.

On subsequent transits through Paris, I was disabused of yet more of my naivete when I began taking trains into the central city instead of taxis. Maybe it was a labor strike that had caused me to do this at first, but the experience so intrigued me that I began making a habit of it. Not even in New York had I felt such a gulf between the popular image of a city and this kind of lived experience of it via public transportation.

For long sections of these rides, the cars were filled with Black and brown people–– overwhelmingly young and, I surmised, overwhelmingly either the children of recent immigrants or immigrants themselves, with France’s former colonies in North and sub-Saharan Africa the most likely places of origin. Before reaching the stylish, urban dreamland exalted in countless romantic Hollywood fantasies and more than a century of novels and travel writing, one must traverse something altogether different and discordant: a huge expanse of what the French rather delicately refer to as banlieues. They needn’t have resorted to the term, though. For many of these places, the old European word “ghetto” would have fit just fine.

Passing through and eventually visiting some of them, I was reminded of other grim cityscapes I have known in other parts of the world. The comparisons are admittedly not perfect, but segregated townships built under South African apartheid came to mind, as did some of the bleaker sections of New York where I had once paid dues as a local reporter, such as the more depressed parts of the Bronx.

As with the notorious infrastructure schemes of the powerful New York master planner of the last century, Robert Moses, which deliberately isolated Black communities and cut them off from areas privileged in terms of race and class and from public amenities such as the city’s beaches, Paris’s banlieues are poorly connected to the city’s transportation system, heightening their economic and social isolation and therefore their misery. For those looking for points of optimism after France’s recent civil disturbances, projects underway or on the books are expected to dramatically increase subway connections for these long-neglected parts of the city.

There is an old saw that holds that history never repeats itself but often rhymes. And it was just such a resonance—and not the recent events in Paris themselves, per se—that has brought France’s capital powerfully to mind for me.

To briefly review those events, though: On June 27, a French teenager of Algerian descent was fatally shot by a police officer during a traffic stop in what amounted to a virtual execution. A video of the incident that was widely shared online shows a police officer shoot 17-year-old Nahel Merzouk at close range through his window as his car pulls away.

Outraged young people, who were disproportionately “of color,” then rose up in protests that lasted for six days and included numerous acts of looting, vandalism, and even violence. This, in turn, drew florid condemnations from broad segments of French society, with many people using racialized language or outright racism to denounce not just the protesters’ behavior, but also the growing presence of minority groups in France and the immigration that helps drive it.

What has intrigued me here is a powerful coincidence of timing—and, as I will explore below, perhaps a deeper connection in terms of history and significance with a major decision by the U.S. Supreme Court. And therein, a paradox arises.

France has long prided itself on its all-but-unique handling of racial diversity. Official policy comes close to pretending that such a thing does not exist and takes this for an unqualified positive. The republic is indivisible, says one often invoked phrase, and in the pursuit of its supposed universalism, France has made it illegal to collect data on the basis of a person’s race.

If it is possible to glimpse some admirable idealism in France’s notion of universalism, it has an insufficiently acknowledged dark side as well. Firstly, it requires a near complete assimilation into the dominant national identity of we might call “Frenchness,” which is overwhelmingly defined and policed by people of one race. This might even be considered one of its main, if unstated, features. In order to function, French universalism requires a charade: pretending to be colorblind.

This colorblindness may help prevent French people from noticing that their television news industry or their cinema, to take two industries, are crushingly white, well beyond the true demographic breakdown of the society. But it does nothing to alleviate the underlying reality that opportunity still correlates strongly to race in the country. The same, for that matter, is true of life in the isolated banlieues, as opposed to the tonier parts of the city. I have little doubt that the same patterns hold in other spheres of society as well, from elite educational institutions to national politics.

France’s readiest and most powerful counterexample is, of course, the United States, which has long served as an almost archetypical national “other” to justify French policies and obtain buy-in from a French public that has been socialized over generations to view the United States both with haughty disdain and as a menace to the French way of life. Any idea of taking race or color into account in forming public policy is dismissed as succumbing to a dangerously corrupting Americanism.

The recent ruling by the U.S. Supreme Court that race-conscious college admissions programs violate the U.S. Constitution’s guarantee of equal protection, however, suggests the French may have little to worry about on this score. The two countries would indeed appear to be converging in favor of the French way: pretending that color doesn’t exist and that race has no place in social policy.

The Supreme Court ruling may have barred the overt consideration of race in college admissions in the United States, but it cannot pretend away the fact that Black students are dramatically underrepresented in higher education in the country, as they have been for generations—a product of actual policy during the United States’ long era of segregation and Jim Crow.

In fact, as the University of Chicago law professor Sonja B. Starr has argued, racial gaps exist across a very wide range of categories in U.S. life, from income and employment rates to maternal mortality and life expectancy to exposure to toxic environmental pollution and incarceration.

The question is: What are wealthy societies such as the United States and France to do about such realities? Overtly taking race into consideration clearly displeases large numbers of people in rich democracies, especially among those who have benefited most from inequality. If governments are not allowed to even weigh the racial facts before them, what realistic hope is there for public policy to redress these problems?

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Puissant and Sensitive America is Always Busy Putting Sanctions on His Potential “Enermies”

The United States has imposed sanctions on roughly a third of the global population, targeting nations like Russia, North Korea, Iran, most African countries, and China. These sanctions, now totaling over 15,000 according to the Washington Post, are often justified by Washington as measures against military aggression or to defend human rights. But at their core, these sanctions punish nations for exercising their sovereignty or refusing to bow to external pressure. Their effectiveness is highly questionable. Over the past decade, US regulators have employed more than ten different lists to target Chinese firms deemed harmful to US interests . By July 2024, more than 1,000 Chinese firms had been designated under US sanctions and red-flag lists.

In a maximalist scenario of full blocking sanctions applied to targets such as Huawei, SMIC, Hikvision, or Zhejiang Dahua, at least $40.2 billion in ex-China revenue and up to $67.5 billion in aggregate market cap could be at risk. Such a long-arm move would create significant global spillovers.

Two decades of war, recession, polarization, and now pandemic have dented American power. Frustrated U.S. presidents are left with fewer arrows in their quiver, and they are quick to reach for the easy, available tools of sanctions. The evidence that economic sanctions cause serious harm to civilian populations is overwhelming. Broad sectoral sanctions are known to stunt a country’s overall economic growth, sometimes causing or prolonging recessions and even depressions. Sanctions also hinder access to essential goods such as food, energy, and medicine; obstruct humanitarian assistance; and, as a result, generate additional poverty, hunger, disease, and high numbers of avoidable deaths.

The harm caused by economic sanctions, as with most economic shocks, is disproportionately borne by women and other oppressed and marginalized communities. US economic sanctions can even obstruct multilateral responses to global crises. For example, when the IMF issued $650 billion in Special Drawing Rights to support the global economy in 2021, US sanctions on central banks prevented many countries from making use of their share of the allocation.

A recent literature review showed that 30 of 32 peer-reviewed, quantitative studies found that broad sanctions have a significant negative impact on measures such as income, poverty, mortality, and human rights. US sanctions on Venezuela are estimated to have contributed to tens of thousands of deaths in a single year. Sanctions on North Korea were estimated to have led to the deaths of approximately 4,000 civilians in 2018 alone. In short: sanctions kill. These devastating economic and humanitarian consequences in turn drive civilians to seek better lives elsewhere, including in the United States.

0 notes

Text

Your Black World

http://bit.ly/1dwTN6Q

It is no secret that slavery rests at the foundation of American capitalism and is often synonymous with the sugar, tobacco, and/or cotton plantations that fueled the Southern economy. What many may not know is that slavery also rests at the foundation of many notable corporations. From New York Life to Bank of America, several companies have benefitted from slavery. Many of the companies even acknowledged their involvement in slavery and offered apologies in an attempt to reconcile their tainted history but, is an apology enough?

History has consistently shown that slavery has diminished the quality of life for African Americans and simultaneously enhanced the quality of life for White Americans. From institutionalized racism to blocked social and economic opportunities, African Americans are often excluded of African Americans.

Apologies cannot compensate an entire race of people for all of the social and economic ills they face as a result of their enslavement. They cannot address the residual effects of slavery. They cannot provide job opportunities to a race of people who are experiencing high unemployment rates. Apologieswithout action from the very systems they helped to create. Had it not been for slave labor, many corporations would not be where they are today and for these companies to acknowledge their involvement in slavery and then simply say ‘Oh, I’m sorry”, is to downplay their role in perpetuating the degradation are nothing more than a futile attempt to correct a wrong by pacifying the wronged. Instead of apologies, these companies could give back to the African American community bydonating to HBCUs, investing in minority businesses, offering more minority scholarships, or launching initiatives to increase their number of minority employees.

New York Life New York Life found that its predecessor (Nautilus Insurance Company) sold slaveholder policies during the mid-1800s.

2. Tiffany and Co Tiffany and Co. was originally financed with profits from a Connecticut cotton mill. The mill operated from cotton picked by slaves.

3. Aetna Aetna insured the lives of slaves during the 1850’s and reimbursed slave owners when their slaves died.

4. Brooks Brothers The suit retailer started their company in the 1800s by selling clothes for slaves to slave traders.

5. Norfolk Southern Rail Road Two companies (Mobile & Girard and the Central of Georgia) became part of Norfolk Southern. Mobile & Girard paid slave owners $180 to rent their slaves to the railroad for a year. The Central of Georgia owned several slaves.

6. Bank of America Bank of America found that two of its predecessor banks (Boatman Savings Institution and Southern Bank of St. Louis) had ties to slavery and another predecessor (Bank of Metropolis)accepted slaves as collateral on loans.

7. U.S.A. Today U.S.A. Today reported that its parent company (E.W. Scripps and Gannett) was linked to the slave trade.

8. Wachovia Two institutions that became part of Wachovia (Georgia Railroad and Banking Company and the Bank of Charleston)owned or accepted slaves as collateral on mortgaged property or loans.

9. AIG (American International Group) AIG purchased American General Financial which owns U.S. Life Insurance Company. AIG found documentation that U.S. Life insured the lives of slaves.

10. JP Morgan Chase JP Morgan Chase reported that between 1831 and 1865, two of its predecessor banks (Citizens Bank and Canal Bank in Louisiana) accepted approximately 13,000 slaves as loan collateral and seized approximately 1,250 slaves when plantation owners defaulted on their loans

#Shocking List of 10 Companies that Profited from the Slave Trade#us slavery economics#reparations are due

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

Facts of Nicaragua's Constitution

Preamble (Part of it)

WE,

Representatives of the People of Nicaragua, united in the Constituent National Assembly,

INVOKING

The struggles of our indigenous ancestors;

The spirit of Central American unity and the combative tradition of our people who, inspired by the example of General JOSE DOLORES ESTRADA, ANDRES CASTRO and EMMANUEL MONGALO, destroyed the dominion of the foreign adventurers and defeated the North-American intervention in the National War;

The protagonist of the cultural independence of the Nation, the Universal Poet RUBEN DARIO;

The anti-interventionist actions of BENJAMIN ZELEDON;

The General of Free People, AUGUSTO C. SANDINO, Father of the Popular and Anti- imperialist Revolution;

The heroic action of RIGOBERTO LOPEZ PEREZ, initiator of the beginning of the end of the dictatorship;

The example of CARLOS FONSECA, the greatest perpetuator of Sandino’s legacy, founder of the Sandinista National Liberation Front and Leader of the Revolution;

The martyr of public liberties, Doctor PEDRO JOAQUIN CHAMORRO CARDENAL;

The Cardinal of Peace and Reconciliation, Cardinal MIGUEL OBAND Y BRAVO;

The generations of Heroes and Martyrs who forged and carried forward the liberation struggle for national independence.

WE PROMULGATE THE FOLLOWING POLITICAL CONSTITUTION OF THE REPUBLIC OF NICARAGUA

Article 2

National sovereignty resides in the people who exercise it by means of democratic procedures, deciding and participating freely in the establishment and improvement of the nation’s economic, political, cultural and social system. The people exercise sovereign power through their representatives freely elected by universal, equal, direct, and secret suffrage, barring any other individual or group of individuals from usurping such representation. They may also exercise it directly by means of a referendum or plebiscite or other mechanisms established by the present Constitution and the laws. Similarly, it could exercise it by other means of direct democracy, like participatory budgets, citizens’ initiatives, territorial councils, territorial and municipal assemblies of the indigenous peoples and those of African descent, sectorial councils and other means established by this Constitution and the laws.

Article 4

The State recognizes the individual, the family, and the community as the origin and the end of its activity, and is organized to achieve the common good, assuming the task of promoting the human development of each and every Nicaraguan, inspired by Christian values, socialist ideals, practices based on solidarity, democracy and humanism, as universal and general values, as well as the values and ideals of Nicaraguan culture and identity.

Article 5

Liberty, justice, respect for the dignity of the human person, political and social pluralism, the recognition of the distinct identity of the indigenous peoples and those of African descent within the framework of a unitary and indivisible state, the recognition of different forms of property, free international cooperation and respect for the free self-determination of peoples, Christian values, socialist ideals, and practices based on solidarity, and the values and ideals of the Nicaraguan culture and identity, are the principles of the Nicaraguan nation.

Christian values ensure brotherly love, the reconciliation between the members of the Nicaraguan family, the respect for individual diversity without any discrimination, the respect for and equal rights of persons with disabilities, and the preference for the poor.

The State recognizes the existence of the indigenous peoples and those of African descent who enjoy the rights, duties and guarantees designated in the Constitution, and especially those which allow them to maintain and develop their identity and culture, to have their own forms of social organization and administer their local affairs, as well as to preserve the communal forms of land property and their exploitation, use, and enjoyment, all in accordance with the law. For the communities of the Caribbean Coast, an autonomous regime is established in the present Constitution.

Nicaragua encourages regional integration and advocates the reconstruction of the Grand Central American Homeland.

Article 47

All Nicaraguans who have reached 16 years of age are citizens.

Only citizens enjoy the political rights set forth in the Constitution and in the laws, without further limitations other than those established for reasons of age.

Rights of citizens shall be suspended by imposition of serious corporal or specific related punishments and by final judgment of civil injunction.

Article 181

The State shall organize by means of a law the regime of autonomy for the indigenous peoples and ethnic communities of the Atlantic Coast, which shall have to contain, among other rules: the functions of their government organs, their relation with the Executive and Legislative Power and with the municipalities, and the exercise of their rights. This law shall require for its approval and reform the majority established for the amendment of constitutional laws.

The concessions and contracts of rational exploitation of the natural resources granted by the State in the Autonomous Regions of the Atlantic Coast must have the approval of the corresponding Regional Autonomous Council.

The members of the Regional Autonomous Councils of the Atlantic Coast can lose their condition for the reasons and procedures established by law.

by Dunilefra, working for World Order

#Nicaragua#Dunilefra#Politics#Political Reform#World Politics#World Order#Fundamental Rights#Human Rights#Economy#Religion#State Policy#Political Analysis#Constitution#Constitutional Law

0 notes

Text

The Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) has announced a vacancy for the position of Director-General at the West African Monetary Agency (WAMA), an autonomous and specialized agency of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS). The role is based in Freetown, Sierra Leone, and is open to qualified candidates from the 15 ECOWAS member countries.

Job Details and Requirements

The CBN has emphasized that the ideal candidate for this prestigious role must possess a strong background in economics or finance. The position requires a minimum of a five-year post-secondary degree in the relevant field and at least 20 years of professional experience in a multilateral institution, public organization, central bank, regional economic organization, or academic institution. Additionally, applicants must have held senior management positions for at least ten years.

Also Apply for : Wigwe University Massive Recruitment for Non-Academic Staff

Key qualifications and skills include:

Fluency in either English or French

Thorough knowledge of macroeconomic and monetary issues, including regional integration, exchange rates, and monetary policies

Excellent interpersonal and communication skills

Demonstrated ability to build consensus and achieve results in complex situations

Ability to work effectively with multilateral institutions such as central banks, the African Development Bank (AfDB), the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Bank, and the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa

Excellent aptitude for managing a multicultural team

The position is for a four-year term, renewable once. The Director-General will be responsible for overseeing the agency's day-to-day operations and ensuring the implementation of activities aligned with the strategic orientations defined by the Committee of Governors of ECOWAS Central Banks.

Application Process

Qualified candidates are encouraged to apply by submitting a cover letter addressed to the Chairman of the Committee of Governors of ECOWAS Central Banks, a detailed curriculum vitae, copies of diplomas obtained, and copies of work certificates. All documents can be submitted in either French or English.

Applications must be sent before August 19, 2024, to the following addresses:

[email protected]

[email protected]

[email protected]

[email protected]

Conclusion

This vacancy presents an exciting opportunity for experienced professionals within the ECOWAS region to contribute to regional economic integration and monetary policy. The CBN urges qualified candidates to apply and take part in shaping the future of West Africa’s monetary landscape.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs):

What is WAMA? WAMA stands for the West African Monetary Agency, an autonomous agency under ECOWAS responsible for monetary policy coordination among member states.

Who can apply for the Director-General position? Qualified candidates from any of the 15 ECOWAS member countries, with at least 20 years of relevant experience and fluency in English or French, can apply.

Where is the job located? The Director-General position is based in Freetown, Sierra Leone.

What is the deadline for submitting applications? Applications must be submitted by August 19, 2024.

What documents are required for the application? Applicants need to submit a cover letter, detailed curriculum vitae, copies of diplomas, and work certificates

0 notes