#Eighteenth Street Methodist Church

Text

The evangelicals in 19th Century Williamsburg and Greenpoint. A Journey Retro

The evangelicals in 19th Century Williamsburg and Greenpoint. A Journey Retro

Williamsburgh, 1834. Illustration from Eugene L. Armbruster’s Photographs & Scrapbooks. Source: Brooklyn Historical Society.

The faith-flavored identity of New York City was decided on the frontiers of social controversy in religious places like the evangelical Protestant churches of Williamsburg and Greenpoint.

Early settlers in the area held private Sunday services in their homes or took a…

View On WordPress

#Brooklyn Abolitionists#Bushwick Dutch Reformed Church#Eighteenth Street Methodist Church#Eugene L Armbruster#First Baptist Church of Williamsburg#Greenpoint#Henry Reed Stiles#Jacob Riis#John LeConte#Joseph LeConte#Lenape Indians#Lydia Cox#North Third Street Mission#Panic of 1837#Phoebe Palmer#Samuel Cornish#Samuel Eli Cornish#Seventh Day Adventists#St John&039;s Methodist Episcopal Church#Sylvester Tuttle#Tony Carnes#William Hodges#Williamsburg#Williamsburg Bethel Independent Church#Williamsburg Bible Society#Williamsburg Methodist Episcopal Church#Williamsburg Temperance Society

0 notes

Text

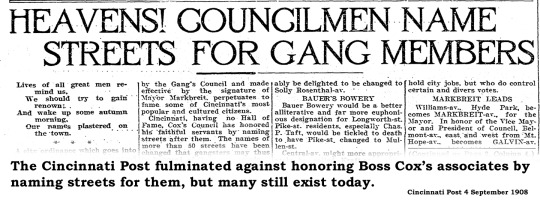

Some Cincinnati Street Names Still Honor Boss Cox’s Minions

On Friday, September 4, 1908 the Cincinnati Enquirer carried a substantial legal advertisement, comprising four columns of dense type announcing Ordinance 731 as ordained by Cincinnati City Council

“To change the names of certain streets, avenues, courts, terraces, places and alleys of the City of Cincinnati as designated therein.”

What followed was a list of hundreds of Cincinnati streets that, partially or completely, would receive new names by order of the city administration. The Enquirer, which had cozied up to the political machine of George Barnsdale “Boss” Cox, printed the ordinance without comment. The Cincinnati Post, a constant burr under the saddle of the Cox Machine (and therefore the recipient of no city advertising) smelled a rat. In that day’s edition, the Post identified the rodent:

“Cincinnati having no Hall of Fame, Cox’s Council has honored his faithful servants by naming streets after them. For, after erasing names of 50 old streets, Council has substituted names of its own members, and what streets were left were named for members of the Mayor’s office, the Service Board, the Police Department, the City Solicitor’s office, the City Engineer’s office, and even favored friends who don’t hold city jobs, but who do control certain and diverse votes.”

Buried in that long list of renamed streets were more than 50 for which the new name honored someone in the city administration, and everyone in the city administration owed their jobs to Boss Cox. Heading the list was Mayor Leopold Markbreit, whose name now graced the former Williams Avenue. The mayor pleaded humble ignorance:

“I tell you it’s impossible to tell when, or where, or how lightning will strike, likewise honors. A few years ago I never expected to have even a cat named after me. I’ll have to find out where Markbreit-av. is and see that it is kept clean.”

Vice Mayor John Galvin got a street in Lower Price Hill, where the former Belmont Avenue became Galvin Avenue. But it wasn’t just the top administrators who got their names assigned to street. The mayor’s secretary got a street in Avondale. A street in Fairmount was selected to recognize Louise Amthauer, stenographer to City Council (and the only woman on the list). Kuhfers Alley, between Findlay and Charlotte streets in Brighton still memorializes Police Detective Conrad Kuhfers. Hopkins Avenue in Avondale was renamed to honor Thirteenth Ward Councilman J.H. Asmann Jr.

While the Post went apoplectic, the Cox Machine blithely basked in the warm glow of their own genius. This was an era when political machines controlled quite a few American cities, from Boss Tweed’s Tammany Hall in New York City, Frank Hague in Jersey City, and Tom Pendergast in Kansas City. All of them bought votes, handed out jobs to supporters and made legal (and criminal) difficulties disappear. Now Cox had a new reward system, one that cost a lot less than a financial bonus – name a street for your good friends!

Cox, to be sure, kept his fingerprints away from this little gambit. The outrage fell upon City Council. In particular, the ringleader was revealed to be Edwin O. Bathgate, representing the Eighteenth Ward on City Council. Bathgate sat on Council’s Streets & Parks Committee and submitted the names in that capacity. A loyal Cox foot soldier, Bathgate had recently been indicted for buying votes.

In fact, there was a perfectly good reason to change many of these street names. Cincinnati was engaged in a voracious annexation binge, and had gobbled up Westwood, Clifton, Avondale, Linwood and Riverside in 1894. Evanston, North Avondale and Bond Hill were still being digested. Many of the new neighborhoods had existed as separate villages for a long time and had streets with names identical to street already in Cincinnati.

Price Hill had Second, Third, Fourth and Fifth avenues, for example. There were two Hand streets; one in the West End and one in Winton Place. Both Hyde Park and Mount Auburn had Erie Avenues. Mount Auburn’s became Thayer and, later, Glencoe.

Winton Place and Westwood both had Epworth Avenues (evidence of strong Methodist congregations). Council decided that Westwood’s Epworth would become Bethany Avenue, but had not calculated on James N. Gamble, president of Procter & Gamble, having a fondness for the Epworth Avenue that ran by his church. City Council backed down and the Winton Place Epworth became East Epworth.

Gamble’s intervention reveals a pattern in the street changes – most took place in poorer neighborhoods and it was mostly the wealthier residents who objected. Saloonkeeper Louis Schueler, representing Cumminsville on City Council, named a street for himself. He told the Post [9 September 1908] that he didn’t think anyone would miss the former Mad Anthony Street:

“Cumminsville residents don’t appreciate history. Why, when I was in Council 15 years ago, they asked me to change the name of that street. They said they didn’t care what other name I gave it. As to naming it for myself, I lived on the street over 30 years.”

Schueler told the Post that those who objected to the change because of its historic significance (Wayne was a Revolutionary War hero.) were the “high-brows” of the ward. The high-brows must have won, because Mad Anthony Street is still there.

Price Hill objected to changing Fifth Avenue to Milwaukee Avenue, and the city relented, naming it Rosemont Avenue.

The Louisville Courier-Journal [ 13 September 1908] weighed in:

“The Cincinnati Councilmen have presumed to change the names of streets having historical significance to names of no dignity whatsoever, such as the names of local bosses, stenographers, letter carriers, janitors and Councilmen.”

The Post ran a front-page cartoon complaining that this eruption of political vanity was destined to destroy the real estate market. Some of the names were changed back or changed again, but many of Boss Cox’s henchmen are still remembered on our daily commutes.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Magnolia Cemetery

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the graveyard was a gloomy place. It was a constant reminder that death was ever present. Today when we visit the graveyards around Charleston there is the signs of death all over, like the “Death Angel”, with the winged heads and skulls. The graveyard was not a place to celebrate life.

In 1711, Sir Islington Wren proposed more of a garden atmosphere for burial away from town. This idea didn’t gain popularity until the mid-1800’s. During the Victorian Era, views toward death changed. No longer were people wanting to be reminded of death, but rather a celebration of life.

In 1849 the first cemetery board assembled, known as the Magnolia Cemetery Company, they began searching for land to build a cemetery. Ninety-two acres of the Magnolia Umbra Plantation was donated to the company.

Magnolia Umbra Plantation was a rice plantation, located just north on the Charleston peninsula on the Cooper River. The plantation was owned by a Mrs. Lindrey.

The Magnolia Cemetery opened November 19, 1850 and was designed by Edward C. Jones. Jones designed Trinity Methodist Church on Meeting Street, as well as the Colonel John Ashe House on South Battery to name a few. He designed the layout of the cemetery grounds and a gothic chapel that has since been destroyed.

Walking through Magnolia Cemetery is like strolling through a garden, and for many the cemeteries were places for family outings and picnics. The cemetery has ancient live oaks draped in Spanish Moss, Magnolia trees, camellias and azaleas lining the roads and pathways that rival the gardens on the Ashley River. The best part is, it’s free!

Magnolia is the final resting place for national, state and local leaders. A few years ago, the last of the confederate soldiers were buried here after they were retrieved from the H.L. Hunley, and all three crews are buried here. There are many memorials to those who fought and died for southern independence. There are poets, authors, artist, and even a British War area.

The funerary art here is incredible. The marble, slate, and granite markers are inscribed, not just with names and dates, but also some of the most incredible carvings. The sculpted memorials equal the ones found ancient Rome and Greece. Magnolia Cemetery even has a pyramid facing the salt marsh toward the back of the property.

If you plan to visit Magnolia Cemetery, allow for about a half day. It is gorgeous out here and you can get wrapped up reading all the markers. You might want to pack a picnic, spread a blanket on the ground, and enjoy the peace and tranquility of one of Charleston’s hidden gems.

0 notes

Text

18th Street Methodist Episcopal Churchyard

An 1852 map shows the 18th Street Methodist Episcopal Church, with its grounds extending to 19th Street.

In 1836, members of the Methodist Episcopal Church of the City of New York established a church on property owned by the society on 18th Street, west of 8th Avenue. The church was erected on a site known as the “old Chelsea burying ground,” where, it was said, villagers had long been buried. Shortly after dedicating their new house of worship on 18th Street, the society built a number of burial vaults in the grounds surrounding the church. These were used by church members and residents of the rapidly growing neighborhood of Chelsea, and became a source of considerable income for the church. Approximately 500 bodies were interred in the vaults between 1836 and 1851, when a city ordinance forbade further burials below 86th Street.

A view of 18th Street Methodist Episcopal Church in 1885

The churchyard of the 18th Street Methodist Church consisted of a strip of land, 100 x 50 feet, running from the back of the church to 19th Street, and an additional 50 x 20 foot plot on the southeast corner behind the church parsonage. It contained 64 vaults, including large public vaults used by licenses, and smaller, private vaults acquired by deed. The vaults were “splendidly built of brickwork throughout;” the entrance to some was by a door on the side; to others admittance was gained by lifting a slab on top. In an 1886 article in the Evening Post, a Chelsea resident describes a funeral he attended in the 18th Street churchyard during the summer of 1849, when a neighbor and her and child during a cholera epidemic of that year. “I do not remember in what vault the young mother, with her babe asleep upon her quiet bosom, was laid away,” he recalled, “but I remember going down some steps that were green and slimy with the breath of decay, and looking with awe-struck curiosity at the contents of some shelves that were already occupied by crumbling tenants.”

The Daily Graphic illustrated the removals from the 18th Street Methodist churchyard in 1886. At left coffins are shown stacked in the vaults; at right the grounds dug up behind the church.

By the 1880s, the members of the 18th Street Methodist Church viewed their defunct vault yard with disfavor, considering it unused land that could be a source of revenue. The trustees of the church, a young, “vigorous and business-like” group with no sentimental attachment to a generation that had long since passed away, in 1882 offered a resolution to remove the dead from the vaults in the strip of land extending from the rear of the church to 19th Street. Although many of the vault owners initially resisted the plan to clear out the vaults and sell the ground, by 1886 the Trustees had obtained consent to proceed with the disinterments and the bodies were removed to plots at Woodlawn and Cypress Hills cemeteries. After the removals, the church sold the section of the property fronting on 19th street for $26,000 and townhouses were built there. It’s not known when or if the bodies from the smaller plot to the rear of the parsonage, or the bodies from the earlier Chelsea Village burial ground, were ever removed from the church grounds.

The 18th Street Church continued as a place of worship for the Methodists in the Chelsea section until 1945, when they merged with the Metropolitan-Duane Methodist Church at 7th Avenue and 13th Street and subsequently sold their property on 18th street. During demolition of the church in 1950, workmen unearthed eleven human skulls and several dozen arm and leg bones when digging belong the surface of the lot. No evidence of the old vaults was reported at that time; the remains, which were found in a large pile in the ground, likely were left behind during the earlier removals. A six-story apartment building sits atop the site today.

A 2016 aerial view of the former site of the 18th Street ME church grounds

Sources: Dripps’ 1852 Map of the City of New-York extending northward to Fiftieth St; The History of the Charter Church of New York Methodism, Eighteenth Street, 1835-1885 (Force 1885); “Their Ancestor’s Bones,” New York Times, Jan 22 1882; “The City’s Old Graveyards,” The Chronicle (Mt Vernon NY), Aug 25 1882; “Opening a Charnel House,” New York Herald, Nov 15 1886; “Emptying a Graveyard,” Daily Graphic, Nov 16 1886; “A Tour Around New York,” Evening Post, Dec 15 1886; “Skulls Unearthed in Old Churchyard,” New York Times Mar 25 1950

Advertisements

Source: https://nycemetery.wordpress.com/2018/12/06/18th-street-methodist-episcopal-churchyard/

0 notes

Text

Park Avenue Methodist Church - 106 East 86th Street

In 1768 property, 42 feet wide by 60 feet deep,was acquired on John Street, near Nassau by the first Methodist congregation in America. The John Street Church, popularly known as Wesley's Chapel, was opened in October that year. From that humble start, Methodism spread.

In the spring of 1837 a new congregation was formed well north of the city in the village of Yorkville. In a coincidence of timing, the venerable John Street Church was being demolished at the time. On February 1, 1837 that year The Herald had reported "The property on which the Methodist Church in John street stood is said to be forfeited by the late sale and conversion of it into stores."

Under the leadership of Rev. Daniel De Vinne the Methodist Episcopal Church in Yorkville purchased four plots on what would become East 86th Street, and according to The New York Times decades later (on November 12, 1882), the old structure "was purchased by the Eighty-sixth-Street congregation and removed to the site of their present house in 1837."

The Yorkville congregation outgrew the building within two decades. "In this venerable old edifice worship was conducted until 1858, when it was torn down and a new brick church was erected in its place at a cost of $9,800," reported The Times. But it was not entirely the end of the historic structure. The article went on to say "At the erection of the second church building a single beam of the old John-street wood was placed under the kneeling-board in front of the altar."

By 1882 Yorkville was no longer a distant hamlet; but a part of the steadily growing city. The congregation had once again outgrown its building. In August ground was broken for a new church directly across 86th Street and on November 12 The New York Times reported that the laying of the cornerstone would take place the following day. The article noted that the wood from the John Street Church "will be removed and placed in a similar position in the new...church so that the church will retain its claim to material, as well as spiritual descent from the first of American Methodist churches."

With the new building came a new name. On April 2, 1883 The New York Times announced "This organization will soon be known as the Park-Avenue Church, as it is now building a fine house of worship at Park-avenue and Eighty-sixth-street."

That impressive structure was designed by well-known architect J. Cleveland Cady. The eccentric design in included a 150-foot tall corner tower, "built after the style of the Campanile in Florence" and gargoyles on the Park Avenue elevation "which have the face of a tiger, the wings of a bat and the claws of an eagle." The cost, including the land, would equal $5.68 million today.

At the time the Park-Avenue Methodist Episcopal Church had a membership of more than 700, described by The New York Times as "fashionable." Nevertheless, it would be another 21 years before the $40,000 mortgage would be paid off. On March 18, 1905 the New-York Tribune reported that the debt was finally paid off. The celebratory service, predicted the newspaper "will be a memorable one in the long history of the Old Eighty-sixth Street Church, as it has always been known."

Debt would come again in the 1920's. A new concept was sweeping metropolitan areas--the "skyscraper church." Congregations from coast to coast were demolishing their old structures and building apartment or office buildings which incorporated a ground floor church space. In theory the congregation would reap tremendous income from the rental properties. Not everyone was thrilled by the concept. The New York Times, for instance, editorialized, "Must we visualize a New York in which no spire points heavenward?"

By now the Park Avenue corner sat within a much-changed neighborhood. Old houses and shops had been pulled down to be replaced by jazz-age apartment buildings. The property on which the church stood was ripe for similar development.

On July 6, 1924 The New York Times wrote "The decision of the Park Avenue Methodist Church to tear down its present edifice for the erection on the site of a fifteen-story apartment house, the lower four floors of which will be utilized for the continuance of the church activities, there is presented not only another striking illustration of the changing conditions for successful church management in certain parts of the city, but also additional evidence of the increasing popularity of East Eighty-sixth Street as an apartment residential thoroughfare."

As the trustees worked with architect Henry C. Pelton, the concept changed. A year later, on July 27, 1925, they announced that the 15-story apartment building plan would go ahead; but without the church. A separate, three-story structure would be erected for that purpose directly behind, on 86th Street.

The trustees estimated the rental income from the apartments at "not less than $10,000 a year," according to The Times. "The church believes that this sum will almost pay the running expenses of the congregation." Cady's brownstone structure was razed in July 1925 and construction was immediately begun on the new buildings.

The cornerstone of the church was laid on March 23, 1926. The Times noted that it "will be in the Byzantine style. It will contain an auditorium, to seat 537 people, on the street level, with Sunday School, social rooms and a pastor's study on the two upper floors." "Byzantine" was a broad description, and Henry C. Pelton's design drew heavily from the Southern Sicilian Romanesque style.

Three months after the dedication, Samuel H. Gottscho photographed the new building. from the collection of the Museum of the City of New York

The $250,000 structure was dedicated by Bishop Luther B. Wilson on January 8, 1927. A separate dedication service was held later that evening for the new Skinner organ.

For decades the annual New York Methodist Conference had taken place in the Park-Avenue Methodist Church, and they continued within the new building. At the time of its dedication Prohibition was a flashpoint of controversy as hundreds of thousands of citizens sought its repeal. The Methodist Church was firmly in favor of Prohibition, as evidenced in the Conference meetings here on April 3, 1927.

Dr. Clarence True Wilson, general secretary of the Board of Temperance, Prohibition and Public Morals of the Methodist Church asserted "The liquor traffic is in the course of ultimate extinction." He insisted that the newspaper accounts were fake news. "There are those who would have you believe there is a great uprising against prohibition, but this is not so."

Pelton carried on the Southern Sicilian Romanesque motif inside with the tile-paved floor and simple stenciled walls.

Four years later his stance was embraced by the Rev. Dr. James Josiah Henry, new pastor of the Park Avenue Methodist Church. In his sermon on October 25, 1931 he claimed that the New York newspapers were not giving a "true picture" of Prohibition; saying in part "It is this unfairness that has led so many people to state that the eighteenth amendment and the Volstead act cannot be enforced. This is utterly false."

In the meantime, the sometimes bland meetings of the New York Methodist Conference were enlivened by an arrest in April 1930. Two years earlier Rev. L. B. Haines conducted the wedding ceremony of John Willis and Ella Acker. Rev. Haines later learned that the 74-year old bridegroom was already married. Six weeks after the sham marriage Willis deserted Ella and returned to his first wife, who was none the wiser.

John Willis was described by The New York Times as being "fond of religious services." And so he attended a session of the Conference in the Park Avenue Methodist Church. The last person he expected to be there was the Rev. L. B. Haines. Haines slipped out of the church and found a policeman.

On April 8 The New York Times reported "With his two wives in court sympathizing with each other and united in indignation against him, John Willis, 76 years old, pleaded guilty to bigamy yesterday."

The "society room" with its plaster walls and tiled hearth had a monastic feeling. photo by Samuel H. Gottscho, March 25, 1927, from the collection of the Museum of the City of New York

From the pulpit Rev. John J. Henry did not hold back in his often spirited social and political opinions. Ardently anti-union, he announced in his July 22, 1934 sermon that "Reds and radicals" were responsible for the recent strikes on the West Coast. He told the story of a manufacturer who, when he found his plant was being picketed, invited the employees to go fishing with him. The next morning everything was fine within the factory.

"But you cannot treat radicals and Reds that way...They are simply suffering from industrial insanity and they are seeking to destroy our industrial system." He then turned to commercial isolation, the Depression Era version of America First. "We could not possibly supply the rubber needed by our great automotive industry. So it is well to remember when we grow too cocky that we could not get along without Brazil. If we close the door to Cuban sugar in order to aid our own sugar interests, we only punish ourselves. If a man makes a corner in wheat on the Chicago market, peasants on the slopes of the Alps may starve."

He broadened that stance in September 13, 1936 by including the welcoming of all peoples. The Times wrote "Nationalism and high racial feeling he described as evils which tend to destroy representative government."

In his sermon he said in part "I hope there will come a time in the future when you can love the man who lives in the Ukraine, Germany, Holland and other countries just as well as you love your own race and nation. I say this because I believe there is an Almighty God. Unfortunately, the world is not yet in that condition of mind. Too many still believe that 'blood is thicker than water.'"

Seven months after that sermon the Park Avenue Methodist Church was in trouble. The income from the apartment building, which the trustees had assumed would carry expenses, fell short. On April 26, 1937 The Times ran the headline "Park Ave. Methodist Faces Loss of Home." The original 10-year $800,000 mortgage on both properties--a considerable $13.7 million today--was now due. The article explained that Rev. Henry had asked members to "confer Friday evening on steps to prevent the threatened loss of the church of its place of worship."

As the financial crisis dragged on Rev. Henry returned his focus on social and political issues. Naturally, war, Nazism and Facism would soon be on the top of his list. Nearly three months before America was pulled into the conflict with the attack on Pearl Harbor he railed against Hitler and warned of repeating the mistakes of World War I.

In his September 14, 1941 sermon he cautioned against the "mistake of the 1918 Armistice." He said that just as the Allied armies were ready to enter Germany "and crush a power that was menacing the world," the Armistice stopped them. Now, he stressed, "as defenders of religion it is our duty to destroy sin and hate--everything that Hitler represents."

Rev. Henry stepped down because of poor health around 1945, ending a colorful chapter in the history of the Park Avenue Methodist Church. His retirement came at a time when the church's financial condition had once again become a crisis. The Methodist Church ordered the congregation to close in 1946; but appeals by members to the United Methodist Society resulted in financial support and a 10-year reprieve. In 1956 the apartment building was sold.

Financially secure today, the church continues to serve the the neighborhood--one drastically different from the rural hamlet where it was founded nearly 190 years ago.

photographs by the author

Source: http://daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com/2018/11/park-avenue-methodist-church-106-east.html

0 notes

Text

“At least she had loved him once. At least he had four good years with the girl he had loved since he was fifteen, since the night he had watched her sing “Pass It On” on the beach during a church youth group outing. (His family had been Taoists, but his mother had forced all of them to attend First Methodist so they could mix with a ritzier crowd.) He could still remember the way the flickering bonfire made her long wavy hair shimmer in the most exquisite reds and golds, how her entire being glowed like Botticelli’s Venus as she so sweetly sang:

It only takes a spark,

to get the fire going.

And soon all those around,

can warm up in its glowing.

That’s how it is with God’s love,

once you’ve experienced it.

You want to sing,

it’s fresh like spring,

you want to Pass It On.

“Can I make a suggestion, Astrid?” Charlie said as the junk made its way back to Repulse Bay to drop her off.

“What?” Astrid asked sleepily.

“When you get home tomorrow, do nothing. Just go back to your normal life. Don’t make any announcements, and don’t grant Michael a quick divorce.”

“Why not?”

“I have a feeling Michael could have a change of heart.”

“What makes you think that will happen?”

“Well, I’m a guy, and I know how guys think. At this point, Michael’s played all his cards, he’s gotten a huge load off his chest. There’s something really cathartic about that, about owning up to your truth. Now, if you let him have some time to himself, I think you’ll find that he might be receptive to a reconciliation a few months down the line.”

Astrid was dubious. “Really? But he was so adamant about wanting a divorce.”

“Think about it—Michael’s deluded himself into thinking he’s been trapped in an impossible marriage for the past five years. But a funny thing happens when men truly get a taste of freedom, especially when they’re accustomed to married life. They begin to crave that domestic bliss again. They want to re-create it. Look, he told you the sex was still great. He told you he didn’t blame you, aside from blowing too much money on clothes. My instinct tells me that if you just let him be, he will come back.”

“Well, it’s worth a try, isn’t it?” Astrid said hopefully.

“It is. But you have to promise me two things: first, you need to live your life the way you want to, instead of how you think Michael would want you to. Move into one of your favorite houses, dress however it pleases you. I really feel that what ate into Michael was the way you spent all your time tiptoeing around him, trying to be someone you weren’t. Your overcompensating for him only increased his feelings of inadequacy.”

“Okay,” Astrid said, trying to soak it all in.

“Second, promise me you won’t grant him a divorce for at least one year, no matter how much he begs for it. Just stall him. Once you sign the papers, you lose the chance of him ever coming back,” Charlie said.

“I promise.”

As soon as Astrid had disembarked from the junk at Repulse Bay, Charlie made a phone call to Aaron Shek, the chief financial officer of Wu Microsystems.

“Aaron, how’s our share price doing today?”

“We’re up two percent.”

“Great, great. Aaron, I want you to do me a special favor … I want you to look up a small digital firm based in Singapore called Cloud Nine Solutions.”

“Cloud Nine …” Aaron began, keying the name into his computer. “Headquartered in Jurong?”

“Yes, that’s the one. Aaron, I want you to acquire the company tomorrow. Start low, but I want you to end up offering at least fifteen million for it. Actually, how many partners are there?”

“I see two registered partners. Michael Teo and Adrian Balakrishnan.”

“Okay, bid thirty million.”

“Charlie, you can’t be serious? The book value on that company is only—”

“No, I’m dead serious,” Charlie cut in. “Start a fake bidding war between some of our subsidiaries if you have to. Now listen carefully. After the deal is done, I want you to vest Michael Teo, the founding partner, with class-A stock options, then I want you to bundle it with that Cupertino start-up we acquired last month and the software developer in Zhongguancun. Then, I want us to do an IPO on the Shanghai Stock Exchange next month.”

“Next month?”

“Yes, it has to happen very quickly. Put the word out on the street, let your contacts at Bloomberg TV know about it, hell, drop a hint to Henry Blodget if you think it will help drive up the share price. But at the end of the day I want those class-A stock options to be worth at least $250 million. Keep it off the books, and set up a shell corporation in Liechtenstein if you have to. Just make sure there are no links back to me. Never, ever.”

“Okay, you got it.” Aaron was used to his boss’s idiosyncratic requests.

“Thank you, Aaron. See you at CAA on Sunday with the kids.”

The eighteenth-century Chinese junk pulled into Aberdeen Harbour just as the first evening lights began to turn on in the dense cityscape hugging the southern shore of Hong Kong Island. Charlie let out a deep sigh. If he didn’t have a chance of getting Astrid back, he at least wanted to try to help her. He wanted her to find love again with her husband. He wanted to see the joy return to Astrid’s face, that glow he had witnessed all those years ago at the bonfire on the beach. He wanted to pass it on.”

Excerpt From: Kevin Kwan. “Crazy Rich Asians.” iBooks.

0 notes

Text

REFLECTIONS: May 21, 2017

In Acts 17:22-31, Luke writes of Paul standing before the gathered community to bring them the good word. They hear him say, ‘God is not found in fine houses of worship. Not infused in beautiful altars, nor in need of human touch as a way of service. God made everyone and everything as we know it.’ In verse twenty eight, he speaks the poetic line, “for in God we live and move and breathe and find our very being.” Paul goes on to say that God is not something to be owned like art or jewelry. Verse thirty-three, Luke tells us that Paul’s words of inspiration were met with scoffs.

The term scoff is an old term which in modern parlance would mean to disrespect or put down. Then and now it is a method of dismissing the thinking of those we disagree with. Any time a person of faith speaks the truth, they know in the love of God, there will be consequences and not necessarily good ones. The gospel is a difficult story to hear. It is a demanding narrative in terms of calling people to act in faith.

Paul exemplifies this by essentially saying to the people, “you have the trappings of faith, but not the heart.” The buildings, worship furniture, and art work don’t add up to much in the face of God’s holiness, which shows us the way, and shapes us. In a playful paraphrase on the journal of John Wesley (one of the founders of the Methodist tradition), one author illustrates how well Wesley’s preaching was received in the churches with high steeples of eighteenth century England. His diary reads, “Sunday A.M., May 5 Preached in St. Anne’s. Was asked not to come back anymore. Sunday P.M., May 5 Preached in St. John’s. Deacons said, ‘Get out and stay out.’ SundayA.M., May 12 Preached in St. Jude’s. I cannot go back there either. Sunday A.M., May 19 Preached in St. Somebody Else’s. Deacons called special meeting and said I could not return. Sunday P.M., May 19 Preached on street. Kicked off street. Sunday A.M., May 26. Preached in meadow. Chased out of meadow as bull was turned loose during service. Sunday A.M., June 2 Preached at the edge of town. Kicked off the road. SundayP.M., June 2 Preached in a pasture. Ten thousand people came out to hear me.” Having read some of his diary, I can attest this account of Wesley’s journal is at least partly apocryphal. It does have the ring of truth in that it points to an important element in the art of proclamation. The fact that sometimes people are either not ready and perhaps not able to hear the gospel message. When this happens, it becomes much easier and far more entertaining to scoff, gripe, complain or criticize. For true hearing requires not merely paying attention, but investing our heart, mind, and soul.

Dr. Joey K. McDonald

0 notes

Text

The evangelicals in 19th Century Williamsburg and Greenpoint. A Journey Retro

The evangelicals in 19th Century Williamsburg and Greenpoint. A Journey Retro

Williamsburgh, 1834. Illustration from Eugene L. Armbruster’s Photographs & Scrapbooks. Source: Brooklyn Historical Society.

The faith-flavored identity of New York City was decided on the frontiers of social controversy in religious places like the evangelical Protestant churches of Williamsburg and Greenpoint.

Early settlers in the area held private Sunday services in their homes or took a…

View On WordPress

#Brooklyn Abolitionists#Bushwick Dutch Reformed Church#Eighteenth Street Methodist Church#Eugene L Armbruster#First Baptist Church of Williamsburg#Greenpoint#Henry Reed Stiles#Jacob Riis#John LeConte#Joseph LeConte#Lenape Indians#Lydia Cox#North Third Street Mission#Panic of 1837#Phoebe Palmer#Samuel Cornish#Samuel Eli Cornish#Seventh Day Adventists#St John&039;s Methodist Episcopal Church#Sylvester Tuttle#Tony Carnes#William Hodges#Williamsburg#Williamsburg Bethel Independent Church#Williamsburg Bible Society#Williamsburg Methodist Episcopal Church#Williamsburg Temperance Society

0 notes