#Food production

Link

Research has found that some dark chocolate bars contain cadmium and lead—two heavy metals linked to a host of health problems in children and adults.

The chocolate industry has been grappling with ways to lower those levels. To see how much of a risk these favorite treats pose, Consumer Reports scientists recently measured the amount of heavy metals in 28 dark chocolate bars. They detected cadmium and lead in all of them.

CR tested a mix of brands, including smaller ones, such as Alter Eco and Mast, and more familiar ones, like Dove and Ghirardelli.

For 23 of the bars, eating just an ounce a day would put an adult over a level that public health authorities and CR’s experts say may be harmful for at least one of those heavy metals. Five of the bars were above those levels for both cadmium and lead.

That’s risky stuff: Consistent, long-term exposure to even small amounts of heavy metals can lead to a variety of health problems. The danger is greatest for pregnant people and young children because the metals can cause developmental problems, affect brain development, and lead to lower IQ, says Tunde Akinleye, the CR food safety researcher who led this testing project.

“But there are risks for people of any age,” he says. Frequent exposure to lead in adults, for example, can lead to nervous system problems, hypertension, immune system suppression, kidney damage, and reproductive issues. While most people don’t eat chocolate every day, 15 percent do, according to the market research firm Mintel. Even if you aren’t a frequent consumer of chocolate, lead and cadmium can still be a concern. It can be found in many other foods—such as sweet potatoes, spinach, and carrots—and small amounts from multiple sources can add up to dangerous levels. That’s why it’s important to limit exposure when you can.

[...]

Some of the same concerns may extend to products made with cocoa powder—which is essentially pure cocoa solids—such as hot cocoa, and brownie and cake mixes, though they have varying amounts of cacao and possibly heavy metals.

(15 December 2022)

there’s a lot more detail in the article about specific brands, different ways lead and cadmium get into cacao, prior studies and litigation, etc.

the article is written with an optimistic tone about mitigation strategies for you as A Consumer—try to choose brands with lower levels of lead and cadmium! eat lower-percent-cacao chocolates, eat them less often, don’t give dark chocolate to kids, etc.—but it’s ultimately another example of food produced under capitalism being contaminated, and how you cannot escape that by just Shopping Smarter, or by hoping liberal regulation (or lawsuits) will prevent it. especially considering all of the other contaminated products mentioned or linked in the article as See Also’s:

MORE ON FOOD SAFETY

• Your Spices Could Contain Lead and Arsenic

• Is Our Ground Meat Safe to Eat?

• Everything You Ever Wanted to Know About Costco Chicken

• Heavy Metals in Baby Food

• PFAS Chemicals in Food Packaging

Calculating the exact amount of dark chocolate that’s risky to eat is complicated. That’s because heavy metal levels can vary, people have different risk levels, and chocolate is just one potential source of heavy metal exposure.

the unstated corollary (because this is Consumer Reports and not Labor Reports) is that the overall exposure to lead and cadmium surely has to be many times worse for the people who actually work in production (often child slaves [1] [2] [3]). (I did a cursory search for information about the farmers’ exposure, but unfortunately, haven’t been able to find anything among all the results about contamination in the final product? If anyone has sources about that, I would really appreciate seeing them)

#cocoa#cacao#chocolate#food safety#food#food production#supply chains#capitalism#agriculture#metal exposure#lead#cadmium#my uploads#my uploads (unjank)

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Hiii friends!! I'm currently writing a thesis and it would mean the world to me if you helped me out by taking this survey:

Please inform me if you find any grammatical or semantic errors!! If you have any questions, you can always write me in my DMs. Reblogs are very appreciated!! (I'm going to reblog this post several times, so you're welcome to block one of the tags, I understand that it may be annoying)

74 notes

·

View notes

Text

It's so weird how meat-forward American food culture is that Americans who don't eat meat every day will say to me "yeah I'm basically vegetarian I don't eat meat *every* day" like????? Please I'm begging you to consider other forms of protein the human body is not meant to only eat meat, we are omnivores.

Like. It was honestly pretty easy for me to switch to a vegetarian diet because I grew up in a kosher household and kosher meat is *expensive* so we only had meat on Shabbat (once a week). But then I'll talk to other Americans and they'll talk about eating meat every day and I'm like??? How???

I think humans are meant to eat meat and I think expecting everyone to give it up is wrong, but c'mon this is not sustainable you do not need to be eating meat every single day.

Why is America so meat obsessed?????

#food anthropology#food production#american food culture#meat industry#if I had the time I'd answer my question and the answer would be the legacy of colonialism and displacing indigenous#to make way for cattle pastures

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

Excerpt from this story from Grist:

One in 11 people worldwide went hungry last year, while one in three struggled to afford a healthy diet. These numbers underscore the fact that governments not only have little shot at achieving a goal, set in 2015, of eradicating hunger, but progress toward expanding food access is backsliding.

The data, included in a United Nations report released Wednesday, also reveals something surprising: As global crises continue to deepen, issues like hunger, food insecurity, and malnutrition no longer stand alone as isolated benchmarks of public health. In the eyes of the intergovernmental organizations and humanitarian institutions tracking these challenges, access to food is increasingly entangled with the impacts of a warming world.

“The agrifood system is working under risk and uncertainties, and these risks and uncertainties are being accelerated because of climate [change] and the frequency of climate events,” Máximo Torero Cullen, chief economist of the U.N.’s Food and Agriculture Organization, or FAO, said in a briefing. It is a “problem that will continue to increase,” he said, adding that the mounting effects of warming on global food systems create a human rights issue.

Torero calls the crisis “an unacceptable situation that we cannot afford, both in terms of our society, in terms of our moral beliefs, but also in terms of our economic returns.”

Of the 733 million or so people who went hungry last year, there were roughly 152 million more facing chronic undernourishment than were recorded in 2019. (All told, around 2.8 billion people could not afford a healthy diet.) This is comparable to what was seen in 2008 and 2009, a period widely considered the last major global food crisis, and effectively sets the goal of equitable food access back 15 years. This insecurity remains most acute in low-income nations, where 71.5 percent of residents struggled to buy enough nutritious food — compared to just 6.3 percent in wealthy countries.

Climate change is second only to conflict in having the greatest impact on global hunger, food insecurity, and malnutrition, according to the FAO. That’s because planetary warming does more than disrupt food production and supply chains through extreme weather events like droughts. It promotes the spread of diseases and pests, which affects livestock and crop yields. And it increasingly causes people to migrate as they flee areas ravaged by rising seas and devastating storms, which, in turn, can fuel conflict that then drives more migration in a vicious cycle.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Closing Loops in Soilless Gardening - Hydroponics and Aquaponics

What is the future of food production going to look like? Is the projected 10 billion people in 25 years, out of which two thirds will live in cities, going to require us to convert every square meter of arable land into intensive mono cultural farms? Please don't let that be true! There HAS to be some alternative. Fortunately, there are several. Two of them are different ways of growing plants without soil, a radically new method, which may be most appealing to urban food production.

image source

Hydroponics: Growing Plants in Water

When it comes to growing large amounts of food on a small area efficiently, hydroponic systems are often brought up as a solution. And the reasons sound pretty convincing: An efficient hydroponic farm uses 90% less water, and can yield 3-10 times the amount of produce per area, with 7-14 growth cycles in a year. IMPRESSIVE! But before getting too excited, let's not forget: the devil is in the details! It's worth looking into under exactly what conditions those plants grow, being fed by what light, and most importantly which nutrients, and where they come from.

image source

The basic concept, however, of growing plants vertically, in mostly water, with some kind of substrate, such as clay balls or vermiculite, is actually a pretty nifty way to grow food where there are no fields. The most basic form of this may be the Windowfarm technique, which I experimented with myself years ago in my Budapest apartment. Going to Shanghai, the whole idea seems to be taken to a whole new level.

https://static.dezeen.com/uploads/2017/04/sunqiao-urban-agricultural-district-Sasaki-architecture-industrial-china-shanghai_dezeen_hero-b.jpg

image source

Is That Really Sustainable? Or Even Healthy?

… not to mention, does hydroponics even fit into Permaculture? Because let's be honest: with a system that needs to be constantly managed and monitored you could not be further from a self-supporting ecosystem. Also, what exactly do those plants get to eat? The typical N-P-K made industrially out of petrochemicals? Most likely. So while it certainly reduces the transport related drawbacks, hydroponics is by no means energy efficient, and the nutritional value won't be any better than your most industrially grown veggies.

image source

How Does Aquaponics Compare?

Okay, so let's bring in the fish! For those not familiar with the difference between the two systems, aquaponics is the combination of hydroponics and aquaculture, which are simply fish farms. Having fish in a tank, they will naturally defecate into the water, requiring it to be changed regularly. Plants, however love to eat those nutrients that the fish excrete. Or to be more exact, they feed on the nutrients that have been converted by bacteria and other microbes. The ammonia will turn in to nitrites, which in turn become nitrates, that is food for the plants.

image source

So running the water from the fish through the plants growing substrate will on one hand feed the plants, as well as clean it for the fish to enjoy it again. So the system already closed a few loops there, making it more sustainable than just mere hydroponics. Also, the inclusion of microbes already offers a more diverse environment, bringing the system a bit closer to an ecosystem. But let's not get ahead of ourselves: Aquaponic systems still need close monitoring, as they are still a far cry from a self sustaining ecosystem of let's say a pond. Also, the water circulation / aeration is most likely going to require a pump, and depending on the exact setup of the system, maybe artificial lighting for the plants. All these aspects add to the energy requirement of the aquaponic system.

image source

A Truly Closed Loop? Consider the Food of the Fish!

When praising the sustainability of aquaponics, one thing that mustn't be ignored is the source of the fish food. Just like with the hydroponic systems, where the food for the plants or the fertilizer is considered, we can't ignore the feed we give to our fish to eat. If it is the same industrial feed, we may as well have kept to our hydroponics. Not true, since including fish already makes our system more diverse. So instead, let's continue in that same direction. What do fish eat? What is good for them? How can we grow that food ourselves?

image source

Making Your Own Sustainable Fish Food

Here I could probably start a number of individual posts, since talking about fish food is like opening up a can of worms. But fortunately, I already have a number of appropriate things written. Talking about worms, by the way, anyone who has been fishing knows that they are a favored delicacy, and anyone who composts will have no shortage of them. Since worms are mostly vegetarians, and many of us eat meat, it may have been a bit difficult to properly compost greasy, meaty, bony food wastes. That's where black soldier flies come in, whose larvae are also frequently mentioned for fish food. I still need to try growing those guys. As for green plants for the fish, duckweed makes also good fish feed, again something I have no experience with. What I do know, though, is spirulina, which is also super rich in nutrients, and I would be surprised if the fish didn't like it. So I can see throwing some composting worms, black soldier fly larvae, and spirulina into a blender, to make some great nutritious fish food. At the moment this is very theoretical for me, though.

image source

Don't Give Up the Soil Completely

So does this mean we should all focus on setting up our most sustainable fish-plant-compost combo cycles? Hells yeah! But please not at the expense of everything else! Soilless gardening, as exciting and revolutionary as it may sound, is still that: without soil. And let's face it: neither us, nor our beans and tomatoes, have evolved to live entirely without soil. That just seems wrong. Even in a small urban apartment it's worth having a bit of soil on your roof, balcony, or window sill, where you can dig your hands into a world of healthy microbial diversity on occasion. And if you do have the space, by all means, set up a pond, a dam, or another aquatic ecosystem, where fish, and frogs, and dragonflies, and numerous other species can live together without relying on our management. Apart from looking pretty, they will also provide food for us, that is nutritionally superior to anything industrially grown.

Sources: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8

116 notes

·

View notes

Text

Crossbreeding plants, veggies, and produce has been a thing for centuries, but a lot of people seem to mistake those practices with being exclusively associated with non organic and gmo stuff which is unfortunate and also confusing.

Like... lemons and large corn don't come from nature my guys... we did that... but they're not tainted because we did that.

They're tainted because of capitalism.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

International Harvester - the peacemaker of progress.

#vintage illustration#international harvester#harvester#tractors#food production#wwii history#wwii era#wwii#ww2 history#ww2#ww2 art#world war ii#world war 2#the 40s#farming

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

It was 1 kg and became 2 kg of meat.

Russian food producers are deceiving their customers

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wouldn't it be marvellous if all the world's growers could think of growing today's food as nurturing the soil ready for next year's harvest?

"Soil: The incredible story of what keeps the earth, and us, healthy" - Matthew Evans

#book quote#soil#matthew evans#nonfiction#wouldn't it be nice#marvelous#farmers#growers#food production#nurturing#harvest

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

[...]

Del Monte’s 80 sq km plantation sits on the border of Murang’a and Kiambu counties, about 40 kilometres northeast of Nairobi, in a landscape marked with lush green vegetation and rich red soil. The area is also blighted by poverty, unemployment and drug use. This deprivation is despite the money generated by Del Monte, whose pineapple exports earned the country’s economy more than $100m in foreign exchange in 2018. This financial firepower has provided the company with political clout.

Among local villagers, the vast farm is often described as kwa guuka, meaning “our grandfather’s”. It is a bitter reference to the fact that many families were forcefully evicted from the land when it was first acquired by the company’s predecessor several decades ago.

The farm is the single largest exporter of Kenyan produce to the world. This huge global operation means that, although countless pineapples are grown in the area every year, virtually the only ones sold locally are those that have been stolen from the farm.

“The boys around don't have anything much to do, and they need money for their survival. So the easiest way is to go and raid the farm, get the pineapples and sell to the public,” says Joel. “Mostly it's driven by peer pressure and poverty.”

These conditions stand in stark contrast with the lifestyle enjoyed by the 237 guards employed by Del Monte at the farm, who have fully serviced schools, hospitals and sports grounds on company premises.

[...]

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Floods, droughts and panic attacks: Climate change is taking its toll on Europe's farmers | Euronews

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

From Sand to Sprouts: The Rise of Agriculture in the GCC

The countries of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) – Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Qatar, Bahrain, Oman, and the United Arab Emirates – have traditionally been known for their oil reserves and desert landscapes. But in recent years, a surprising trend has emerged: the rise of agriculture.

This shift is driven by several factors. A growing population and a booming food industry are creating a surge in…

View On WordPress

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

@triviallytrue, @headspace-hotel

Re: this: I can't reblog the post, but "pre-Columbian North American giant wild bison herds had a similar total biomass to modern North American grazing cattle herds and converted grass to animal tissue at a similar rate" doesn't seem obviously silly to me.

Biologically, cattle are basically just more docile bison. Human selective breeding has probably made some difference to how much metabolic resources domestic cattle invest in growth vs. everything else, but cattle and bison are physiologically and structurally very similar organisms and meat is already a large percentage of a bison's mass, so I doubt it's an orders of magnitude difference. It's not like fruit, where you can easily selectively breed the plant to grow orders of magnitude bigger fruit.

There is the factor that with domestic cattle you can feed them stuff that isn't wild grass. You can feed them irrigated farmed animal feed crops extensively selectively bred for high yields that grow in monoculture fields with no competition and have their own growth supercharged by commercial fertilizers full of mined phosphorus and Haber process nitrogen etc.. That might make an orders of magnitude difference. But I have the admittedly vague impression that while modern cattle-raising does involve a significant amount of stable feeding with animal feed crops or agricultural waste, it also still involves quite a bit of basically just letting the cattle walk around the landscape and eat grass.

It's worth noting that there is at least one major biome where basically industrialized hunting is still a major modern food source for humans: the ocean. It doesn't seem crazy to imagine the same approach might work in terrestrial contexts; the oceans and the land have similar total productivity and the land is significantly more productive per average square kilometer. On the flip side, it's also worth noting that modern fishing isn't exactly a glowing model of sustainability and even there we're seeing a switch to aquaculture.

Like, I doubt "return the land to the bison and then industrially harvest them the way we harvest ocean fish" would actually be a good idea (or what Headspace Hotel actually wants to do), but it actually isn't obvious to me that it would be orders of magnitude less land-efficient than modern cattle ranching, at least in terms of meat production (a major advantage of cattle over wild bison is you can milk cattle, but we're talking about meat, so that isn't very relevant).

Now I wonder to what degree modern San Franciscan office workers eating way more meat than tenth century Chinese peasants has more to do with improvements in transport (railroads, trucks, motorized ships), food preservation (canning and refrigeration), weapons (guns and railroads enable agriculturalist states to conquer semi-arid nomad country and turn it into export-oriented meat factories), and the efficiency of specifically chicken production than with a general increase in the land efficiency of meat production.

Aside: I have no idea how realistic it is, but "basically treat bison the way we treat fish" gives me a mental image of giant vehicles that drive around the Great Plains to run down herds of bison and pull them in for efficient industrial slaughter, dismemberment, and packaging; basically exactly how fishing boats work, but on land! Giant vehicles roaming steppes and gathering up big wild herbivores for on-site slaughter and processing might be a neat idea for speculative fiction!

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

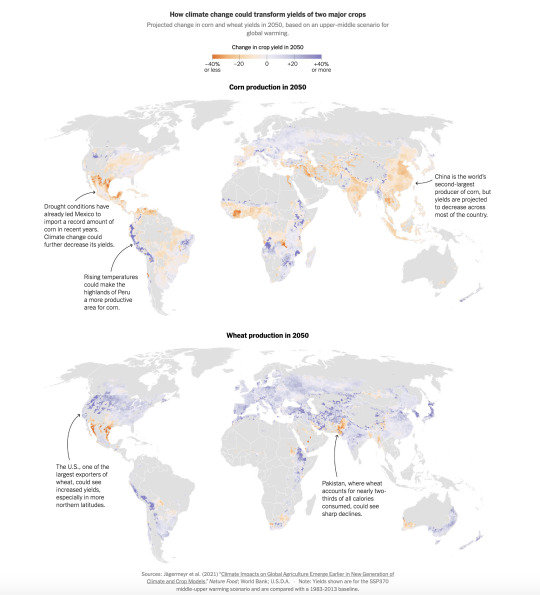

Food as You Know It Is About to Change. (New York Times Op-Ed)

From the vantage of the American supermarket aisle, the modern food system looks like a kind of miracle. Everything has been carefully cultivated for taste and convenience — even those foods billed as organic or heirloom — and produce regarded as exotic luxuries just a few generations ago now seems more like staples, available on demand: avocados, mangoes, out-of-season blueberries imported from Uruguay.

But the supermarket is also increasingly a diorama of the fragility of a system — disrupted in recent years by the pandemic, conflict and, increasingly, climate change. What comes next? Almost certainly, more disruptions and more hazards, enough to remake the whole future of food.

The world as a whole is already facing what the Cornell agricultural economist Chris Barrett calls a “food polycrisis.” Over the past decade, he says, what had long been reliable global patterns of year-on-year improvements in hunger first stalled and then reversed. Rates of undernourishment have grown 21 percent since 2017. Agricultural yields are still growing, but not as quickly as they used to and not as quickly as demand is booming. Obesity has continued to rise, and the average micronutrient content of dozens of popular vegetables has continued to fall. The food system is contributing to the growing burden of diabetes and heart disease and to new spillovers of infectious diseases from animals to humans as well.

And then there are prices. Worldwide, wholesale food prices, adjusted for inflation, have grown about 50 percent since 1999, and those prices have also grown considerably more volatile, making not just markets but the whole agricultural Rube Goldberg network less reliable. Overall, American grocery prices have grown by almost 21 percent since President Biden took office, a phenomenon central to the widespread perception that the cost of living has exploded on his watch. Between 2020 and 2023, the wholesale price of olive oil tripled; the price of cocoa delivered to American ports jumped by even more in less than two years. The economist Isabella Weber has proposed maintaining the food equivalent of a strategic petroleum reserve, to buffer against shortages and ease inevitable bursts of market chaos.

Price spikes are like seismographs for the food system, registering much larger drama elsewhere — and sometimes suggesting more tectonic changes underway as well. More than three-quarters of the population of Africa, which has already surpassed one billion, cannot today afford a healthy diet; this is where most of our global population growth is expected to happen this century, and there has been little agricultural productivity growth there for 20 years. Over the same time period, there hasn’t been much growth in the United States either.

Though American agriculture as a whole produces massive profits, Mr. Barrett says, most of the country’s farms actually lose money, and around the world, food scarcity is driving record levels of human displacement and migration. According to the World Food Program, 282 million people in 59 countries went hungry last year, 24 million more than the previous year. And already, Mr. Barrett says, building from research by his Cornell colleague Ariel Ortiz-Bobea, the effects of climate change have reduced the growth of overall global agricultural productivity by between 30 and 35 percent. The climate threats to come loom even larger.

It can be tempting, in an age of apocalyptic imagination, to picture the most dire future climate scenarios: not just yield declines but mass crop failures, not just price spikes but food shortages, not just worsening hunger but mass famine. In a much hotter world, those will indeed become likelier, particularly if agricultural innovation fails to keep pace with climate change; over a 30-year time horizon, the insurer Lloyd’s recently estimated a 50 percent chance of what it called a “major” global food shock.

But disruption is only half the story and perhaps much less than that. Adaptation and innovation will transform the global food supply, too. At least to some degree, crops such as avocados or cocoa, which now regularly appear on lists of climate-endangered foodstuffs, will be replaced or redesigned. Diets will shift, and with them the farmland currently producing staple crops — corn, wheat, soy, rice. The pressure on the present food system is not a sign that it will necessarily fail, only that it must change. Even if that progress does come to pass, securing a stable and bountiful future for food on a much warmer planet, what will it all actually look like?

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

From Pond Scum to Clean Fuel: How Algae Biofuels Are Revolutionizing Transportation

In the relentless pursuit of combating climate change and breaking free from fossil fuel dependency, the spotlight shines brightly on algae biofuels as a promising and sustainable solution within the transportation sector. These remarkable fuels are harnessed from photosynthetic microorganisms, presenting a compelling case for their potential to drastically reduce carbon emissions and pave the…

View On WordPress

#algae#biofuel#carbon neutral#clean energy#climate change#eco-friendly#energy security#food production#US Navy

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Saving food from waste with Olio and Too good to go

View On WordPress

#2023#bargains#best before date#blog#blogger#blogging#do your bit#food#food production#food waste#food waste app#live for less#londoner#money#oilio#reduced#reusing#saving money#savvy shopper#stop waste#supermarkets#surplus food#throwing food away#too good to go#yellow stickers

2 notes

·

View notes