#Frederik L. Schodt

Text

Anime NYC and Japan Society Announces First-Ever American Manga Awards

The Press Release:

The 2024 American Manga Awards will be the first-ever awards program honoring manga: manga creators, great manga stories, and the publishing professionals who make it possible for readers in US/Canada to discover and enjoy these amazing characters and stories in English. It will culminate in a ceremony and reception hosted by author and translator Matt Alt and honor the works…

View On WordPress

#american manga awards#american manga awards 2024#anime nyc#announcements#awards show announcements#brigid alverson#frederik l. schodt#hiroko yoda#japan society#leftfield media#lynzee loveridge#matt alt#minovsky#nate piekos#renee scott#sasha head#shaenon garrity#shigekazu watanabe#tom orzechowski

0 notes

Text

Cover of the English translation of "Mobile Suit Gundam I: The Awakening" by Yoshiyuki Tomino, Del Rey Books, 1990

1 note

·

View note

Text

Animation Night 149: Toei

Hi there. It’s Thursday. You know what that means (yes, it means i’m freeeeee)

Today we will be rolling back to some of the earliest days of anime!

The story of Toei goes back to 1946. In the immediate aftermath of WWII, there were very few games in town when it came to Japanese animation (or, to be fair, animation in most places). During the war, animators had been recruited to make propaganda films such as Momotaro: Sacred Sailors, among them Akira Daikuhara.

In the immediate aftermath, Kenzō Masoaka (of Benkei tai Ushiwaka, for anyone who remembers AN24) began the first effort to make an animated film post-war. This film was titled Sakura: Haru no genso (Cherry Blossom: Spring’s Fantasy); it was followed by a series of three films about a cat called Tora-Chan. But Masoaka’s studio struggled, constantly closing and re-opening. At the time it was operating under the name 日本動画映画 Nihon Dōga Eiga or Japan Animated Films, or just the abbreviation 日動映画 Nichidō Eiga. In 1956, they were bought by live action studio Toei (itself approaching 20 years old, founded in 1938) and renamed to Toei Dōga, where they started making increasingly elaborate animated films.

Toei of this era was sometimes called the rather patronising name ‘Disney of the East’. There is some truth to it, in that their ambition, especially in the early years, was certainly to make animated films as elaborate as those of old Walt. Their first feature was 白蛇伝 Hakujaden (1958), based on a Song Dynasty Chinese legend about a lost pet snake who transforms into a woman in the hopes of reuniting with her former owner, a monk who thinks that’s sus, and two pandas who try to sort it all out; in English it’s variously translated as The White Snake Enchantress, Legend of the White Serpent or even Panda and the Magic Serpent.

Part of the goal of the film, to Toei Dōga president Hiroshi Ōkawa, was a gesture of reconciliation towards China after the whole ‘invading and occupying’ thing.

The film was Rintarō’s first animation job; it also left a massive impression on a young Hayao Miyazaki, who wrote the following in Gekkan ehon bessatsu: Animēshon (1979), trans. Beth Cary and Frederik L Schodt in Starting Point:

What I’m saying here is that when young people feel attracted to the heroes of a tragedy [context: such as The Diary of Anne Frank], whether in animation or other media, a type of narcissism is really involved; this attraction they feel is a surrogate emotion for something they have lost.

From personal experience, I can say that I first fell in love with animation when I saw Hakujaden, the animated feature produced by Toei Animation in 1958. I can still remember the pangs of emotion I felt at the sight of the incredibly beautiful, young female character Bai-Niang, and how I went to see the film over and over as a result. It was like being in love, and Bai-Niang became a surrogate girlfriend for me at a time when I had none.

It is in this sense that I think we can achieve a type of satisfaction, by substituting something for the unfulfilled portion of our lives.

The feelings evoked by Bai-Niang may go some way to explaining the role of similar girls in Miyazaki’s movies...

Hakujaden has some curious properties as a work of animation. It was, especially for the time, astonishingly elaborate and straining the technical capabilities of the industry (although the claim on Wikipedia that it had 13,590 staff seems rather dubious lmao). The drawing count is stratospheric thanks most scenes being animated on ones and twos - the opposite of the limited animation techniques that anime would later perfect. Despite that, it is also the work of an inexperienced team, and compared to later works its animation can feel awkwardly timed, the flood of inbetweens turning everything to mush.

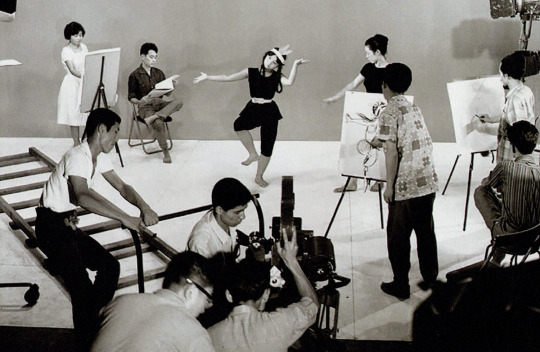

Nevertheless, there are two stars of the show in terms of animation. One is Yasuji Mori, who would later be one of Toei’s star animators, creating scenes such as the dance at the beginning of this post - as well as teaching Miyazaki after he joined Toei. The other is Akira Daikuhara, who was way ahead of the game on effects animation, creating the film’s transformation sequences. Daikuhara would go on to be one of Toei’s main animators of human characters, while Mori tended to take the animal/mascots; he has been a relatively forgotten figure, although that’s starting to change with articles like these ones by Matteo Watzky, whose research just digs deeper and deeper.

Toei’s early films tend to follow the precedent set in Hakujaden, adapting folktales from (mostly) China and Japan. In 1959 they covered a Japanese story in Shōnen Sarutobi Sasuke; 1960, they took on Saiyūki (Journey to the West); then Anju to Zushiōmaru (The Orphan Brother, 1961) and Arabian Nights: The Adventures of Sinbad (1962).

In this period of Toei, there was a lot of ambition, and also a feeling of inadequacy compared to the elaborate animated films being made in other countries. Hayao Miyazaki, who joined Toei in the 1963, wrote in 1982:

I used to create feature-length works for Toei Animation, but compared to the works just mentioned, they were obviously far inferior, at least technically. Sort of like showing rabbits slipping and falling, that sort of thing. We wondered if we would ever catch up to the level of what was being done in America, France or Russia, or if it were even possible to do so. Frankly, we really didn’t know.

To begin with, we didn’t even know what we had to do to reach the same level of excellent as the best works out there. We knew we had constraints, such as short production schedules, small budgets and so forth, but above and beyond that, we began to develop an inferiority complex: we wondered if we even had the basic talent needed to proceed. In retrospect, the only thing that probably kept us going, and drove us to pursue such a long-term goal, was our determination.

Miyazaki’s words should be taken with a grain of salt, since they definitely suit his personal myth-making. Still, conditions at Toei in the 60s were rough, leading to the first major unionisation struggle of anime history, which I wrote about in AN70. The studio started bringing on part-timers paid hourly rather than a salary, and created severe pay discrepancies, which were met with strikes and departures from the studio. Saiyūki took such a tole on its director Taiji Yabushita that he was hospitalised; Yasuji Mori would later create the term ‘anime syndrome’ for this sort of overwork because it was not the last time by any means.

However, I’m going to zoom over all of these to get to the わんぱく王子の大蛇退治 Wanpaku Ōji no Orochi Taiji (The Naughty Prince’s Orōchi Slaying, more commonly translated The Little Prince and the Eight-Headed Dragon) in 1963 - not because it’s necessarily more important, although it’s remembered as one Toei’s best films, but because I happen to have a fantastic analysis of one of its key scenes on hand thanks to AniObsesive and Toadette.

youtube

Wanpaku Ōji breaks from precedent in many ways, particularly its visual design, which takes on highly simplified shapes reminiscent of the then ultra-modern UPA style by way of haniwa figures. The story at least follows the pattern, adapting a Shinto myth in which the storm god Susanoo battles (guess what) an eight-headed dragon Yamat no Orochi. Susanoo is motivated by the death of his mother Izanami, and goes on a journey to try to find her, which leads him to the village of Princess Kushinada - a village with a dragon problem, which they’ve kept at bay only by sacrificing Kushinada’s seven sisters. Susanoo, horny for a princess who looks like his mum, decides it’s time to intervene.

The dance scene above comes in the middle of the movie, in which the goddess Ame-no-Uzume performs an increasingly mystical dance. It was an ambitious experiment of Makoto Nagasawa, who had joined as an inbetweener on Saiyūki, with large spacing and broad motion to create a snappy feeling. Animation Obsessive writes:

Typical motion at Toei, Nagasawa said, would be “neatly in-betweened from the first [key] pose to the last [key] pose.” In other words, in-betweens smoothed out the movement and made it longer, more complete and more realistic. By contrast, Nagasawa’s drawings of Uzume are often at wide intervals, with minimal in-betweens. Sometimes, she basically teleports from one frame to the next.

Even when the intervals aren’t that wide, the way Uzume moves remains big, broad, clear and non-real. Nagasawa pushes her gestures, increases her speed, shows us only what he wants to show us. The action is crisp, always holding its abstract shape. No naturalistic touches distract from the core form of what Uzume does.

Alongside Nagasawa, Yasuji Mori was now coming into a role close to that of the now-standard 作画監督 sakuga kantoku aka sakkan or animation director, an experienced artist whose job is to correct the drawings from many different key animators to keep them on-model. Modern anime productions tend to have a strictly hierarchical approach where the characters are designed by one or a few character designers, usually also the lead sakkan. At Toei, things had been a bit more fluid - the individual animators would often design the characters they were going to animate, with a division of labour closer to the old Disney style. On this film, it became more of a hybrid: Mori drew the final model sheets, but the animators would submit suggested designs to him.

For the most elaborate scenes, such as the dance, they went to great lengths to record a suitable score and record live-action footage with professional ballet dancers. I encourage you to read the AniObsessive article for the details.

At the time of Wanpaku Ōji, Toei was starting to face competition. The already-renowned mangaka Osamu Tezuka had founded MushiPro, which was rapidly taking over TV, and the sphere of TMS satellite studios were starting to get going and siphon away many of their best people such as Yasuo Ōtsuka. Still, the animators at Toei were determined to try and stand alongside international animators:

The team was well aware of the trends in world animation at that time. According to Nagasawa, they were watching work from Canada (Norman McLaren), Czechoslovakia (Jiří Trnka), Russia (The Snow Queen), France (The King and the Mockingbird) and so on. It was all bold, new animation. In The Little Prince, Toei took up the challenge this work presented, without simply copying it. The team contributed to modern animation while staying rooted in the ancient, and in Japan itself.

Subsequently, Japanese animation is sometimes divided into a ‘Toei tradition’ vs. a ‘MushiPro tradition’, of full vs limited animation respectively, followed by the various successors such as Ghibli on the one hand and Madhouse on the other. As ever this is not really very accurate, and both ‘lineages’ crossed over extensively (just look at Kanada).

Toei’s own output adapted to the times. Takahata’s Horus: Prince of the Sun (AN 70) might be the last of the ambitious movies in their old style; after this, the fairytale films were gradually replaced by gekiga animation such as Tiger Mask, super robots like Mazinger Z, and then at the end of the 70s increasingly science fiction adaptations of Leiji Matsumoto’s works (AN 146). In the 80s, shōnen exploded onto the scene and Toei made a lot of Dragon Ball and Saint Seiya, later joined by other franchises like PreCure, Digimon and One Piece. So Toei remains one of the largest and most robust animation studios in Japan. They’ve got a lot of salaried staff, a union(!), and regular work in the form of wildly popular franchises. But occasionally they’ll make something cool and weird within that remit, like Hosoda’s One Piece film (AN61), Kyōsōgiga (AN98) - or Interstella 5555 which we watched last week.

So! Tonight though we’re going to go back and look at those ambitious early days, where it started, with snakes and dragons and a bishōjo who’s 美 enough to inspire the entire career of Hayao Miyazaki. Animation Night 149 will begin at 20:00 UK time (UTC), (13:00 California time), at twitch.tv/canmom - hope to see you there!

And next week I have a serious treat for you, because the Inu-Oh BD finally dropped. Can’t think of something more perfect for #150 than returning to Masaaki Yuasa.

And now to spend the rest of the day until 8pm on intensive gamdev 😵💫

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The hallmark of [Kiki's Delivery Service] is the expression of the many faces of a person. In the presence of her parents, Kiki is childish, but on her own she thinks things over with a serious expression. She may speak roughly and bluntly to a boy her own age, but to her seniors, especially to people important to her, she acts politely."

– Hayao Miyazaki, "I Wanted to Show the Various Faces of One Person in This Film", Roman Album Kiki's Delivery Service (Majo no Takkyūbin), issued October 15, 1989 (Translated by Beth Cary and Frederik L. Schodt)

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blog post - 01

How we can feel the emotion in the comics and manga (image panel)

Comics and manga are visual mediums that rely on arranging and interpreting images to convey stories and emotions. Despite being made up of static images, comics and manga can effectively create emotional responses in readers through various storytelling techniques.

One way that comics and manga create emotion is by using panel layouts and composition. The way panels are arranged on the page can affect the pacing and flow of the story and can be used to create tension, suspense, or emotional impact. For example, a panel may be placed in the center of the page to draw the reader's attention or positioned off-center to create a sense of imbalance or unease. The size and shape of panels can also be used to convey emotion – for example, a large panel may be used to emphasize the importance of a moment. In contrast, a small panel may be used to create a sense of intimacy or vulnerability (McCloud, 1994).

Another way that comics and manga create emotion is through the use of facial expressions and body language. By using exaggerated or nuanced facial expressions and body language, creators can effectively convey the emotions of their characters and create a strong emotional response in readers (McCloud, 1994). This is especially effective in the manga, which often uses highly stylized and expressive character designs (McCloud, 1994).

For example, In the manga "Death Note," the character Light Yagami is often shown with a smug expression and body language that conveys his sense of superiority and manipulative personality. And in the comic "The Walking Dead," the character Rick Grimes is shown with a determined and resolute expression when he makes difficult decisions, which helps convey his sense of leadership and determination.

Use of body language: Comics and manga can also use body language to convey the emotions of their characters. For example, a character may cross their arms or turn away from someone to convey anger or frustration or hug themselves to convey sadness or insecurity.

Use of dialogue: The words and dialogue used in comics and manga can also convey emotions. For example, characters may use sarcasm or irony to convey anger or annoyance or may use pleading or desperate language to convey fear or sadness.

Use of settings and backgrounds: The setting and background of a comic or manga panel can contribute to the emotional impact of the image. For example, a scene set in a dark, gloomy forest may create a sense of foreboding, while a scene set in a bright, sunny field may create a sense of joy and optimism.

Use of symbolism: Comics and manga may also use symbolism to convey emotions. For example, a character may be shown standing in the rain to symbolize sadness or despair or surrounded by flowers to symbolize happiness and joy.

Overall, comics and manga can create powerful emotional responses in readers with panel layouts, composition, facial expressions, and body language. By effectively using these techniques, creators can effectively convey the emotions of their characters and create a rich and engaging reading experience.

References:

McCloud, S. (1994). Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art. New York, NY: Harper Perennial.

McCloud, Scott. Reinventing Comics: How Imagination and Technology Are Revolutionizing an Art Form. HarperPerennial, 2000.

McCloud, Scott. Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art. Harper Perennial Modern Classics, 1994.

Schodt, Frederik L. Inside the Robot Kingdom: Japan, Mechatronics, and the Coming Robotopia. Kodansha International, 1988.

0 notes

Text

Bloomsbury Comic Studies offers “Manga - A Critical Guide”

The latest Bloomsbury Comic Studies, released last week, focuses on manga

Bloomsbury Academic have just published Manga – A Critical Guide, edited by CJ Suzuki and Ron Stewart and hailed by Frederik L. Schodt as “stellar.”

This 280-page guide, released under the Bloomsbury Comic Studies brand, offers a wide-ranging, reasonably priced introductory guide for readers making their first steps into the world of manga. The team behind the book hope it helps readers explore…

View On WordPress

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Manga Review, 8/19/22

The Manga Review, 8/19/22

Attention manga shoppers! Kodansha is currently holding a blow-out sale on digital manga. And when I say “blow out,” I mean it: they’re offering deep discounts on over 3,000 titles, with first volumes priced as low as 99 cents, and later volumes discounted 50%. It’s is a great opportunity to try a buzz-worthy series such as Blue Period, Boys Run the Riot, Knight of the Ice, PTSD Radio, or Witch…

View On WordPress

#Azuki#Frederik L. Schodt#Gengoroh Tagame#Harvey Awards#Hiro Mashima#Kodansha Comics#Manga Industry Jobs#Okazu#Rica Takashima#sailor moon#Sazae-chan#Sho Murase#VIZ#yuri

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Around the Tubes

Check out some comic news and reviews from around the web! #comics #comicbooks

It was new comic book day yesterday! What’d you all get? What did you like? Dislike? Sound off in the comments below. While you think about that, here’s some comic news and reviews from around the web in our morning roundup.

The Beat – Frederik L. Schodt wins second annual Tom Spurgeon Award – Congrats!

Bloomberg – Warner Bros. Discovery Leadership Team Draws Ire Over Diversity – Keep an eye on…

View On WordPress

#action comics#black adam: the justice society files cyclone#comic books#Comics#frankenstein: new world#frederik l. schodt#keeping two#warner bros. discovery

0 notes

Photo

Guests at Anime North 2019!

We are happy to announce that Translator and Author Frederik L. Schodt is coming to this year's convention.

0 notes

Quote

...one of the few girls' manga a red-blooded Japanese male adult could admit to reading without blushing.

Frederik L. Schodt identifies Banana Fish as:

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

“If you plan to reflect what you really want to do in your own work, you must have a firm foundation. My foundation is this: I want to send a message of cheer to all those wandering aimlessly through life.”

— Hayao Miyazaki, Starting Point (trans. Beth Cary & Frederik L. Schodt)

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’ve been asked about how i find manga to read and I just have a hard time answering it because I always feel my picks are extremely obvious one way and another (I usually read manga or authors who are kinda popular currently or were in the past which is how I became aware of them). I’ve said it before but a general insecurity of mine is that I don’t have a niche i just really pick whatever, but I do have a list of criteria (and these are not strict, just ideal conditions)

Completed

Under 20 volumes (anything under 10 volumes end up high on the priority list)

Licensed in english

If its a Japanese manga then ideally I want a bunko edition for storage reasons

Recommended by friends! My picks are very friend influenced even if they sometimes have to peer pressure me for months

I think the cover looks nice :)

This is all very dictated by the fact that I collect the manga I read so I rarely bother with going out of my way for out if print works bc that’s an extra hassle… And while I am pro sampling anything that looks interesting… if it looks like garbage/something you won’t like, then trust your gut!!! Don’t just accept recommendations from anyone especially if their taste in media clearly does not mesh with yours, then you need a second opinion from someone with taste you do agree with.

And here’s the thing with manga in English, or any language that isn’t Japanese, is that for better or worse these spaces are highly curated. The scanlation scene is curated by the specific individuals who take their time to translate these titles for free. If i were to make an uneducated generalization i feel scanlators are more inclined to pick potential viral hits, or just anything cool looking that won’t be a huge project. While the English publishers who are the main paid licensors don’t always feel comfortable making huge monetary bets and will prefer anything that aren’t *too* long, + is in accordance with current trends in anime. These are simply my own observations and I know each scene do not act 100% according to them. I am pointing this out because we kinda need to accept that in English we will never get the true unrestricted full selection of everything that’s out there and the selection will be curated for us one way or another. Which is dizzying to think about! And also why I just don’t like talking about what I want to read, because now that i have little to no problem reading Japanese manga it genuinely instills me with existential dread knowing I won’t have time for everything i come across on a daily basis. But I’m excited for everything I’m guaranteed to read!

And I mostly find what I want to read by browsing stores, physical ones, online or jpn ebook stores. Or I read books about manga! The best ones are a little dated but I love old and complete series so its perfect for me. I will recommend Manga! Manga! The world of Japanese comics (1983) and Dreamland Japan: Writings on Modern Manga (1996) both by Frederik L. Schodt. He’s the original Guy Who Knows And Writes About Manga for an overseas audience so you don’t get a lot of regurgitated and straight up not true facts about manga history. And some of the works and authors he showcase in Dreamland Japan are still to this day not translated and are interesting in their own ways! I also think the coffee table book 100 Manga Artists by Taschen (and its older version simply called Manga) is a cool speed date book with a unique selection of artists. There’s so much out there and so many amazing artists whose work you can visually enjoy even if you can’t read it!

#horrible image selections in the taschen books tho will not elaborate i will just say the library copy i read had whole pages torn out#just wanted to get this out but yeah!! there’s lots waiting for you out there often in the last places you think of checking#and the commercial Japanese manga market is curated in its own unique way#just imagine everything that’s out there in the indie and original doujinshi scene😩😩#also this is a sales pitch to learning Japanese by reading manga its fun i promise!!!#long post

53 notes

·

View notes

Quote

For us something is far more likely to become an object of our longing when we don’t know what it is thinking. The more we humans anthropomorphize something and make it an easy target for empathy, the less interesting it becomes. From the beginning we seem to have a longing for a presence or a power that is far greater than ourselves and not easily understood, a presence beyond our current framework or whose origins are prehistoric. This longing isn’t unique to me, but rather is what we all feel, a memory repeated over and over from our ancestors. When I think of myself and the way I think of nature, I seem to want to comprehend it in such a way. I don’t know why, but nature exists as an incredible force, as something huge, far exceeding our own little good or evil ways. This is the view of nature that we have.

Hayao Miyazaki, from ‘Earth’s Environment as Metaphor: Interview with Tetsuji Yamamoto and Jun’ichi Takahashi, October 20, 1994’ in Starting Point 1979-1996, trans. Frederik L. Schodt and Beth Cary.

“a longing for a presence or a power that is far greater than ourselves and not easily understood, a presence beyond our current framework or whose origins are prehistoric [...] a memory repeated over and over from our ancestors”

“nature exists as an incredible force, as something huge, far exceeding our own little good or evil ways”

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Shigeru Mizuki: Shigeru Mizuki’s Hitler (1971)

#shigeru mizuki#hitler#1970s#manga#history#biography#graphic novel#comics#drawn and quarterly#nazi germany#Zack davisson#world war 2#Frederik l schodt

1 note

·

View note

Text

"Though we may seem to be living lives of routine each day, each experience is a once-in-a-lifetime event. Yet it is incredibly difficult for us to perceive the significance of the experiences in our own lives."

- Hayao Miyazaki, "As an Afterword", Turning Point: 1997-2008, translated by Beth Cary and Frederik L. Schodt

0 notes

Text

Helen McCarthy’s Words Broke Cultural and Gender Barriers in Manga

(This interview took place in 2019, now published for the first time in a two-part series. Read part two here.)

A longtime fan of Japanese comics, British writer Helen McCarthy was determined to showcase women’s place in art and fandom.

When British author Helen McCarthy set out to write a book about manga, Japanese comics, in the 1980s, few people were open to her idea of writing an English language book about Japanese animation. Yet McCarthy had already fallen in love with the way manga told stories through imagery; manga didn’t rely on words, which, to a writer, was remarkable and humbling.

“It took me 10 years of knocking on doors, being rejected, and having people hang up the phone on me,” McCarthy, 68 of London, said. “I knew nothing about how to write books. I knew nothing about pitching, but I was determined to do it and I kept going.”

Manga — the comic or graphic novel style telling of a story — and television-centric anime are distinct from Western animation. Both styles favor large, expressive eyes above minimally drawn noses and mouths (which can, conversely, also be overly exaggerated). Greater detail is given to things like eyelashes, hair, and clothing; colors have more variance and are shaded to add more depth, according to Lifewire.

While Western comics are often considered a “family-friendly superhero genre,” UK-based magazine Manga Big Bang noted, manga is more likely to explore darker themes and material like “sex, violence and scatology.”

“The reason for this freedom in exploring such concepts is cultural, as the primary religious affiliations of Japan is Shinto and Buddhism—religions that do not equate sex with shame,” the magazine added. “This allows the Japanese to be more liberal in exploring sexuality than most Americans.”

Perhaps because of this subject matter and lingering anti-Japanese sentiment in Britain following WWII, McCarthy was told time and time again that there was no interest in consuming or reading about Japanese animation. Yet her own experience voraciously reading manga would prove otherwise.

“It was actually the rejection that kept me going. People, it was mostly guys, were essentially saying, ‘Go away little girl and do something sensible,’” she said. “And why should I do something sensible? I'm going to do this. And I'll show all of you.”

McCarthy initially read everything she could find on Japanese animation in the UK library system, the British Library, and then the British Film Institute Library, though she found very little information. But being from a family of Irish immigrants (and, McCarthy says, the Irish love to read), she learned early on that “if there wasn't a book about you [or a topic] ... you go and write it yourself.”

“In 1983 Frederik L. Schodt published his seminal ‘Manga! Manga! a History of Japanese Comics,’ and I expected a flood of books to follow in its wake,” McCarthy explained via email, “but that didn't happen, so we just plodded on getting as much as we could, meeting the few other Brits who knew about anime and manga and building a small network.”

In her 30s, McCarthy began reaching out to anime/manga fans around the world and relied on the knowledge of fans from other fandoms like Star Trek and supermarionation (a style of puppetry popularized by British television production company AP Films in the 1960s) to learn more about the art form and the culture surrounding it. She travelled throughout Europe, purchasing cheap manga in French and Italian, which she understood enough to passively read.

In the 1980s, McCarthy noted, “there were very few people in Britain who could even pronounce the word anime. And as far as I know, nobody was doing any work on manga in English—even [UK based comics journalist] Paul Gravett hadn't got hooked at that point!”

Before a publisher would give her a chance on the misunderstood medium, McCarthy took things into her own hands. In 1991 she co-founded the magazine Anime UK, a worldwide publication that covered Japanese pop culture. McCarthy was inspired by Anime-zine, the first American semi-professional anime magazine, and the Japanese magazines she and her partner, Steve Kyte, loved. The magazine grew from a fan publication newsletter, also called Anime UK, created after British national sci-fi convention Eastercon in 1990. Wil Overton, who subscribed to the newsletter, shared the newsletter with his boss Peter Goll, who agreed to publish and fund Anime UK through his company, Sigma. Overton and Kyte worked for the magazine as designers and artists while McCarthy served as editor.

Anime UK hoped to tap the UK’s burgeoning anime fandom, and achieve the aesthetic beauty of those Japanese magazines, mirroring the “accessible yet authoritative writing of Anime-zine.” The magazine ceased publication in 1996.

A year later, McCarthy’s first book, Manga, Manga, Manga: A celebration of Japanese Animation at the ICA Cinema, was published.The book collected illustrations, offered plot synopsis, a term lexicon, and descriptions of prominent anime of the time such as Akira and Kiki’s Delivery Service. Since, McCarthy has published 12 books, won a handful of awards for her work and curation, and attended innumerable conventions (including one she chaired), where she has spread her love of Japanese animation across the globe.

CONTINUED IN PART TWO

--

Amanda Finn is a Chicago based freelance journalist who spends a lot of evenings in the theater. She is a proud member of the American Theatre Critics Association. Her work has been found in Ms. Magazine, American Theatre Magazine, the Wisconsin State Journal, Footlights, Newcity and more. She can be found on Medium and Twitter as @FinnWrites as well as her website Amanda-Finn.com.

8 notes

·

View notes