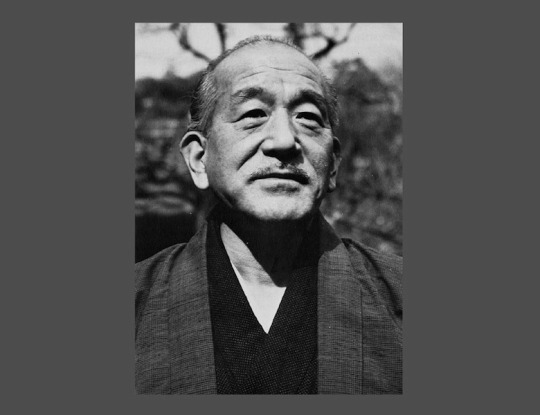

#Ganjirô Nakamura

Text

Odd Obsession(1959)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Assistir Filme Ervas Flutuantes Online fácil

Assistir Filme Ervas Flutuantes Online Fácil é só aqui: https://filmesonlinefacil.com/filme/ervas-flutuantes/

Ervas Flutuantes - Filmes Online Fácil

Companhia japonesa de teatro kabuki aporta numa pequena ilha de pescadores. Komajuro (Ganjirô Nakamura), um dos fundadores do grupo, passa a frequentar todos os dias a casa de sua antiga amante, Oyoshi (Haruko Sugimura), dona de um bar e mãe de Kiyoshi (Hiroshi Kawaguchi).

0 notes

Photo

Love Under the Crucifix (Ogin-sama), Kinuyo Tanaka (1962)

#Kinuyo Tanaka#Masashige Narusawa#Ineko Arima#Tatsuya Nakadai#Ganjirô Nakamura#Mieko Takamine#Osamu Takizawa#Kôji Nanbara#Manami Fuji#Yoshio Miyajima#Hikaru Hayashi#Hisashi Sagara#1962#woman director

17 notes

·

View notes

Photo

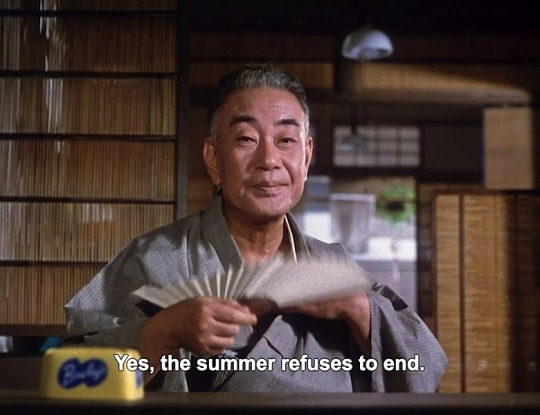

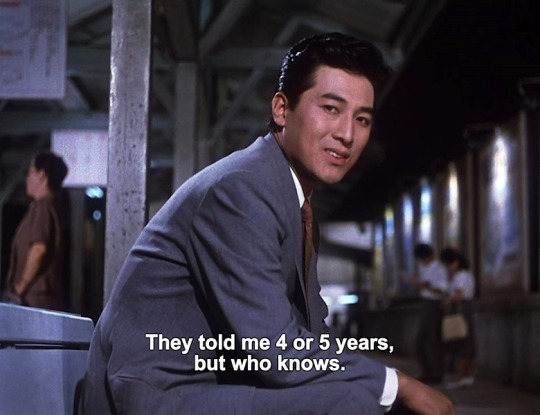

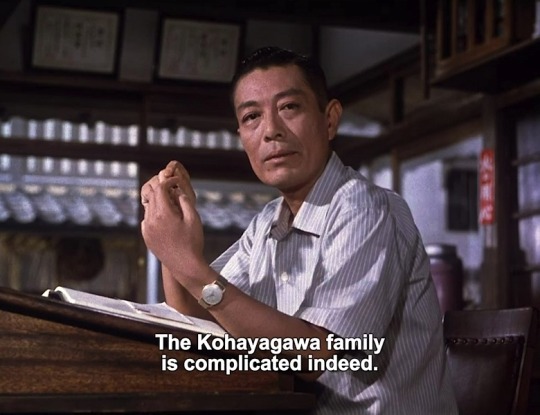

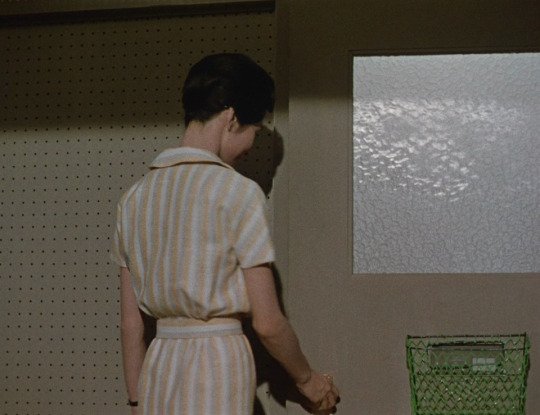

The End of Summer (Yasujirō Yasujirō Ozu 1961)

#The End of Summer#Yasujirō Ozu#ozu#yasujiro ozu#summer#Kohayagawa ke no aki#Kohayagawa-ke no aki#1961#hot#Ganjirô Nakamura#ganjiro nakamura#Akira Takarada

527 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kwaidan (1964)

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

kohayagawa-ke no aki / the end of summer (jp, ozu 61)

#Kohayagawa-ke no aki#the end of summer#Yasujirô Ozu#Ganjirô Nakamura#Setsuko Hara#Yôko Tsukasa#Michiyo Aratama#Asakazu Nakai

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

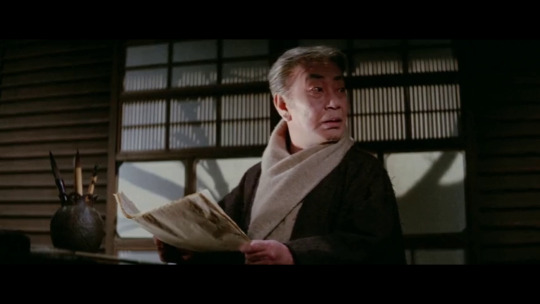

The Lower Depths | Akira Kurosawa | 1957

#Akira Kurosawa#Kurosawa#The Lower Depths#1957#Toshirô Mifune#Kyôko Kagawa#Bokuzen Hidari#Kichijirô Ueda#Akemi Negishi#Minoru Chiaki#Ganjirô Nakamura#Isuzu Yamada#Eijirô Tôno#Kamatari Fujiwara#Tadayoshi Fujitayama#Haruo Tanaka#Yû Fujiki#Atsushi Watanabe

73 notes

·

View notes

Text

2018 Movie Odyssey Awards

And that’s it folks. That’s all the posts they wrote on the 2018 Movie Odyssey. All the films featured here were films that I saw for the first time in their entirety over the last calendar year (the entire list of which you can see here). Except for the Worst Picture category at the bottom, this entire post is a roll call of cinematic excellence. You can’t go wrong with the winners and nominees in these many categories. Submitted for your consumption and reflection...

Best Pictures (I name ten, and never distinguish one above the other nine)

The Blue Angel (1930, Germany)

Charade (1963)

8½ (1963, Italy)

The Heiress (1949)

A Man Escaped (1956, France)

The Philadelphia Story (1940)

Pyaasa (1957, India)

Roma (2018, Mexico)

Shoplifters (2018, Japan)

Stalker (1979, Soviet Union)

This is the first Movie Odyssey Best Picture lineup without an entry from either the 1990s or 2000s. It is the first Best Picture lineup since 2015 without a silent film being among the top ten. But what is not here should detract from the excellence of what is here. There are no 9/10s here... The Blue Angel, Charade, and Pyaasa received 9.5/10s; everything else received a 10/10. From the romantic antics in Charade (as part-spy thriller) and The Philadelphia Story; lust masquerading for love in The Blue Angel and 8½; standing resolutely on one’s own self-worth in The Heiress and Pyaasa; the desperation of A Man Escaped and Stalker; and the modern instant classics of Roma and Shoplifters, this is the best Best Picture slate in the last three years.

Best Comedy

Blondie (1938)

Crazy Rich Asians (2018)

Incredibles 2 (2018)

My Neighbors the Yamadas (1999, Japan)

Overboard (1987)

The Philadelphia Story

Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse (2018)

Stowaway (1936)

The Whole Town’s Talking (1935)

Wonder Man (1945)

It didn’t make me laugh the hardest (that goes to Incredibles 2 and Spider-Verse), but The Philadelphia Story managed to reaffirm what is most important in loving someone and seeing in others what isn’t necessarily the most visible thing. Cary Grant, Katharine Hepburn, Jimmy Stewart, and Ruth Hussey are an amazing ensemble. Close behind are those two aforementioned animated movies and another animated peer, My Neighbors the Yamadas. The Whole Town’s Talking also was in the mix.

Best Musical

Girl Crazy (1943)

Grease (1978)

Moon Over Miami (1941)

The One and Only, Genuine, Original Family Band (1968)

Pete’s Dragon (1977)

Pyaasa

Seven Brides for Seven Brothers (1954)

South Pacific (1958)

A Star Is Born (2018)

Stowaway

This category favors musicals that are original, not adaptations. Seven Brides for Seven Brothers would never be made today, because no one would get the satire for its gendered misbehavior. But with its incredible musical score, outstanding choreography, and appealing performances despite a brow-raising plot, it is by far the best musical I saw this year for the first time. Girl Crazy, Family Band, and Pyaasa would have been next up.

Best Animated Feature

The Cat Returns (2002, Japan)

Incredibles 2

Mary and the Witch’s Flower (2017, Japan)

Mirai (2018, Japan)

My Neighbors the Yamadas

Perfect Blue (1997, Japan)

Pom Poko (1994, Japan)

Ralph Breaks the Internet (2018)

Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse

The Wacky World of Mother Goose (1967)

There was a lot of separation from the top films and the bottom films in this category. The excellent family comedy My Neighbors the Yamadas sends the late Isao Takahata a winner (its comedy entirely based on Takahata’s strengths in observing human behavior), in what was also the last Ghibli film I needed to see to complete the studio’s filmography. Close behind were Perfect Blue and the best animated feature of 2018, Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse.

Best Documentary

The Beatles: Eight Days a Week – The Touring Years (2016)

Don’t Look Back (1967)

Free Solo (2018)

Pick of the Litter (2018)

RBG (2018)

Won’t You Be My Neighbor? (2018)

It was the cinéma vérité of Don’t Look Back versus the emotional power of Won’t You Be My Neighbor? in the end. And at the end, what appealed to me most was the latter. Mr. Rogers was a part of my childhood, and I’m only learning more about him and the lessons he imparted to all his neighbors in my mid-twenties. I never imagined I would be revisiting him now, but here we are! The harrowing (at least, in the final half-hour) Free Solo - dont watch if you’re afraid of heights - was solidly in third in this category.

Best Non-English Language Film

The Blue Angel, Germany

8½, Italy

Floating Weeds (1959), Japan

Gojira (1954), Japan

A Man Escaped, France

My Neighbors the Yamadas, Japan

Pyaasa, India

Roma, Mexico

Shoplifters, Japan

Stalker, Soviet Union

With four entries, this was Japan’s to lose. In what was essentially a toss-up between Federico Fellini and Andrei Tarkovsky, it was the former’s film that will this category for me. I first saw a part of 8½ almost ten years ago now, deleting the recording after realizing there was something about the film that I, as a teenager, could not get. There is only one movie you need to watch, probably, about artist’s block, and that’s 8½. Considered just after that and Stalker are Roma, Pyaasa, and Shoplifters. Gojira - best known to all as Godzilla - was not expected to be here because I once saw the American cut/dub of the film (which cuts a lot of the tragic and allegorical elements). There is no better monster movie than the original Godzilla.

Best Silent Film

Camille (1921)

Caught in a Cabaret (1914 short)

It (1927)

Mabel’s Blunder (1914 short)

Mare Nostrum (1926)

Piccadilly (1929)

Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1927)

West Point (1927)

I honestly did not see enough silent films last year. But that doesn’t take away from how good West Point is - as a drama, a comedy, a romance, and a sports film. Edward Sedgwick’s film juggles a lot of hats, and by sheer charm of its performances, manages to find the right balance. Trailing West Point were Piccadilly and a strong adaptation of Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

Personal Favorite Film

Charade

Christopher Robin (2018)

A Corny Concerto (1943 short)

Gojira

Incredibles 2

The Journey of Natty Gann (1985)

My Neighbors the Yamadas

The Philadelphia Story

The Whole Town’s Talking

Won’t You Be My Neighbor?

1) The Philadelphia Story; 2) Won’t You Be My Neighbor?; 3) The Journey of Natty Gann; 4) Charade; 5) Incredibles 2; 6) My Neighbors the Yamadas; 7) Gojira; 8) The Whole Town’s Talking; 9) Christopher Robin; 10) A Corny Concerto

You folks have no idea how many times my top three switched places while considering this. So much to love about them all. Since I haven’t mentioned Natty Gann yet in my comments, let me do so here. Sometimes, I’m in the mood for a simple, but beautifully shot Disney film out in the wilderness. Meredith Salenger as the title character must make her way from Chicago to Washington state after an unfortunate accident where she is separated from her father. I just adore the nature shots, Natty’s wolfdog companion, and James Horner’s ridiculously beautiful score.

Best Director

Robert Bresson, A Man Escaped

Alfonso Cuarón, Roma

George Cukor, The Philadelphia Story

Stanley Donen, Charade

Guru Dutt, Pyaasa

Federico Fellini, 8½

Hirokazu Koreeda, Shoplifters

Michael Powell, 49th Parallel (1941)

Andrei Tarkovsky, Stalker

William Wyler, The Heiress

A bit of an upset here, but my goodness it takes incredible skill to pull off such social commentary with the amount of artistry Pyaasa does. Ambitious in structure, aesthetic, and thematic approach, it is Guru Dutt who will take this home. Next up would have been Tarkovsky and Fellini.

Best Acting Ensemble

All This, and Heaven Too (1940)

Crossfire (1947)

Cry, the Beloved Country (1951)

The Heiress

Imitation of Life (1934)

A Man for All Seasons (1966)

The Philadelphia Story

The Post (2017)

Shoplifters

Splendor in the Grass (1961)

An excellent set of nominees for Acting Ensemble, with few weak links among them all. They might not be the biggest ensemble, but pretty much everyone is pitch perfect in Imitation of Life - essentially bolstered by its supporting actresses in Louise Beavers and Fredi Washington. The Philadelphia Story in a close second.

Best Actor

Cary Grant, Charade

Emil Jannings, The Blue Angel

Burt Lancaster, Gunfight at the O.K. Corral (1957)

Canada Lee, Cry, the Beloved Country

James B. Lowe, Uncle Tom’s Cabin

Marcello Mastroianni, 8½

Ganjirô Nakamura, Floating Weeds

Sidney Poitier, A Warm December (1973)

Paul Scofield, A Man for All Seasons

Jack Webb, The D.I. (1957)

Paul Scofield, as Sir Thomas More, is a man on a mission - a mission to stop Henry VIII to stop screwing things up even more. Reprising his role from the stage, to me Scofield is clearly the winner as he imbues More with incredible authority yet knowing vulnerability. An astounding, career performance from Scofield is trailed only by Cary Grant and Marcello Mastroianni.

Best Actress

Yalitza Aparicio, Roma

Bette Davis, All This, and Heaven Too

Marlene Dietrich, The Blue Angel

Elsie Fisher, Eighth Grade (2018)

Olivia de Havilland, The Heiress

Audrey Hepburn, Charade

Katharine Hepburn, The Philadelphia Story

Waheeda Rehman, Pyaasa

Anna May Wong, Piccadilly

Natalie Wood, Splendor in the Grass

Olivia de Havilland’s growth throughout The Heiress is downright incredible to watch. How she asserts herself in the final minutes is the culmination of all that has happened up until that point - a film about a woman who finds the strength within herself to state her clearest intentions as pointedly as possible without breaking societal expectations. Just trailing are Yalitza Aparicio (please nominate her for this year’s Academy Awards) and the Hepburns.

Best Supporting Actor

Montgomery Clift, The Heiress

Sam Elliott, A Star Is Born

Rodney A. Grant, Dances with Wolves (1990)

Graham Greene, Dances with Wolves

Bob Odenkirk, The Post

Sidney Poitier, Cry, the Beloved Country

Anthony Quinn, Warlock (1959)

Mickey Rooney, The Black Stallion (1979)

Robert Ryan, Crossfire

Takashi Shimura, Gojira

I don’t know folks, this category seems to like villains. And Robert Ryan’s psychopathic, anti-Semitic murderer is as frightening as a film noir villain can get. Considering what I had seen from Ryan up to this point, there was no preparing me for that. Runners-up include Graham Greene (of Oneida descent), Sidney Poitier, Mickey Rooney, and Takashi Shimura.

Best Supporting Actress

Louise Beavers, Imitation of Life

Stockard Channing, Grease

Wendy Hiller, A Man for All Seasons

Ruth Hussey, The Philadelphia Story

Lesley Manville, Phantom Thread (2017)

Sandra Milo, 8½

Anne Revere, National Velvet (1944)

Millicent Simmonds, A Quiet Place (2018)

Fredi Washington, Imitation of Life

Michelle Yeoh, Crazy Rich Asians

No one could really touch Paul Scofield in Best Actor. Likewise, no one could touch Louise Beavers in Imitation of Life. Yes, Beavers’ role in the film is that of a stereotypical “mammy” at first glance. But looking deeper - and with a major assist from an extremely thoughtful screenplay - Beavers is allowed to give this role so much more than many of her fellow black actresses were ever permitted to have. In a film on racial identity and belonging, she is what makes Imitation of Life tick. The distant challengers were co-star Fredi Washington, Lesley Manville, and Sandra Milo.

Best Adapted Screenplay

Robert Alan Arthur, Warlock

Robert Bolt, A Man for All Seasons

Ruth and Augustus Goetz, The Heiress

Sadayuki Murai, Perfect Blue

Alan Paton and John Howard Lawson, Cry, the Beloved Country

Casey Robinson, All This, and Heaven Too

Donald Ogden Stewart and Waldo Salt, The Philadelphia Story

Arkadi Strugatsky and Boris Strugatsky, Stalker

Jo Swerling and Robert Riskin, The Whole Town’s Talking

Isao Takahata, My Neighbors the Yamadas

Best Original Screenplay

Rodney Ackland and Emeric Pressburger, 49th Parallel

Paul Thomas Anderson, Phantom Thread

Ari Aster, Hereditary (2018)

Robert Bresson, A Man Escaped

Robert Buckner, Dodge City (1939)

Bo Burnham, Eighth Grade

Alfonso Cuarón, Roma

Federico Fellini, Ennio Flaiano, Tullio Pinelli, and Brunello Rondi, 8½

William Inge, Splendor in the Grass

Hirokazu Koreeda, Shoplifters

Best Cinematography

Eduard Tisse, Alexander Nevsky (1938, Soviet Union)

Caleb Deschanel, The Black Stallion

William H. Clothier, Cheyenne Autumn (1964)

Dean Semler, Dances with Wolves

Gianni Di Venanzo, 8½

V.K. Murthy, Pyaasa

Philippe Rousselot, A River Runs Through It (1992)

Alfonso Cuarón, Roma

Alexander Knyazhinsky, Stalker

Nicholas Musuraca, Stranger on the Third Floor (1940)

Best Film Editing

Paul Crowder, The Beatles: Eight Days a Week – The Touring Years

Robert Dalva, The Black Stallion

Jim Clark, Charade

Leo Catozzo, 8½

Tom Cross, First Man (2018)

Eddie Hamilton, Mission: Impossible – Fallout (2018)

Robert Kern, National Velvet

Harutoshi Ogata, Perfect Blue

Ralph E. Winters, Quo Vadis (1951)

Barbara McLean, The Rains Came (1939)

Best Adaptation or Musical Score

S. D. Burman and Sahir Ludhiyanvi, Pyaasa

Adolph Deutsch and Saul Chaplin, Seven Brides for Seven Brothers

Al Kasha, Joel Hirschhorn, and Irwin Kostal, Pete’s Dragon

Alfred Newman, Moon Over Miami

Alfred Newman and Ken Darby, South Pacific

Benj Pasek and Justin Paul, The Greatest Showman (2017)

Walter Scharf, Hans Christian Andersen (1952)

Richard M. Sherman and Robert B. Sherman, The One and Only, Genuine, Original Family Band

Louis Silvers, Stowaway

George Stoll, Girl Crazy

It is one of the few wholly original musicals here. And though its score is not perfect, its highs are some of the best 1950s MGM has to offer.

Best Original Score (eleven nominees because this year’s slate was way too hard to decide on... even the ones I cut)

John Barry, Dances with Wolves

Aaron Copland, The Heiress

James Horner, The Journey of Natty Gann

Akira Ifukube, Gojira

Henry Mancini, Charade

Sergei Prokofiev, Alexander Nevsky

Nino Rota, 8½

Miklós Rózsa, Quo Vadis

Max Steiner, All This, and Heaven Too

Dimitri Tiomkin, The Alamo (1960)

Ralph Vaughan Williams, 49th Parallel

This was the most difficult category to call this year. This was the strongest collection of Best Original Score nominees in a few years, with arguments that could easily be made for John Barry, Akira Ifukube, Nino Rota, Max Steiner, and Dimitri Tiomkin. In the end, it was between the three composers not known for film scores, but their classical music: Aaron Copland, Sergei Prokofiev, and Ralph Vaughan Williams. Prokofiev took third place as I found that the placement of music in Alexander Nevsky paled a bit compared to The Heiress and 49th Parallel. In the end, I went with the Englishman because his distinct sound has never really been replicated for movies, and Vaughan Williams’ works are less available in North America. There are other Copland scores - and some that I feel more strongly about. So in this titanic battle of film score composers, congratulations to Ralph Vaughan Williams!

Best Original Song

“Bless Your Beautiful Hide”, music by Gene de Paul, lyrics by Johnny Mercer, Seven Brides for Seven Brothers

“Candle on the Water”, music and lyrics by Al Kasha and Joel Hirschhorn, Pete's Dragon

“Chaar Kadam”, music by Shantanu Moitra, lyrics by Swanand Kirkire, PK (2014, India)

“Charade”, music by Henry Mancini, lyrics by Johnny Mercer, Charade (1963)

“Gunfight at the O.K. Corral”, music by Dimitri Tiomkin, lyrics by Ned Washington, Gunfight at the O.K. Corral

“Love Is a Many-Splendored Thing”, music by Sammy Fain, lyrics by Paul Francis Webster, Love Is a Many-Splendored Thing (1955)

“Mystery of Love”, music and lyrics by Sufjan Stevens, Call Me by Your Name (2017)

“Rain”, music by Shin'ichi Nakajima, Saori Fujisaki, and Satoshi Fukase, lyrics by Saori Fujisaki and Satoshi Fukase, Mary and the Witch’s Flower

“Shallow”, music and lyrics by Mark Ronson, Lady Gaga, Anthony Rossomando, and Andrew Wyatt, A Star Is Born

“You're the One That I Want”, music and lyrics by John Farrar, Grease

Thanks to all those who participated in the preliminary and final rounds! And even those who didn’t participate but gave me the support power through this. Details are here!

Best Costume Design (TIE)

Konstantin Eliseev, Alexander Nevsky

Orry-Kelly, All This, and Heaven Too

Ruth E. Carter, Black Panther (2018)

Mary E. Vogt, Crazy Rich Asians

Sandy Powell, The Favourite (2018)

Edith Head and Gile Steele, The Heiress

Albert Wolsky, The Journey of Natty Gann

Elizabeth Haffenden and Joan Bridge, A Man for All Seasons

Mark Bridges, Phantom Thread

Herschel McCoy and Joan Joseff, Quo Vadis

You couldn’t make me choose, folks!

Best Makeup and Hairstyling

Peter Frampton, Paul Pattison, and Lois Burwell, Braveheart (1995)

Kazuhiro Tsuji, David Malinowski, and Lucy Sibbick, Darkest Hour (2017)

Samantha Denyer, The Favourite

Colin Arthur, The NeverEnding Story (1984)

Uncredited, Piccadilly

Charles E. Parker, Sydney Guilaroff, and Joan Johnstone, Quo Vadis

Uncredited, Rob Roy: The Highland Rogue (1953)

Amanda Knight and Francesca Crowder, Solo (2018)

Geoffrey Rodway and Biddy Chrystal, The Sword and the Rose (1953)

Perc Westmore, Jean Burt Reilly, and Ed Voight, The Woman in White (1948)

Best Production Design

Iosif Shpinel and Nikolai Solovyov, Alexander Nevsky

Peter Ellenshaw, John B. Mansbridge, Robert McCall, Al Roelofs, Frank R. McKelvy, and Roger M. Shook, The Black Hole (1979)

Hannah Beachler and Jay Hart, Black Panther

Otto Hunte, The Blue Angel

Max Rée, Cimarron

Ted Smith, Dodge City

Piero Gherardi, 8½

Edward Carrere and William L. Kuehl, The Fountainhead (1949)

John Meehan, Harry Horner, and Emile Kuri, The Heiress

William A. Horning, Cedric Gibbons, Edward C. Carfagno, and Hugh Hunt, Quo Vadis

Achievement in Visual Effects

The Absent-Minded Professor (1961)

The Black Hole

First Man

Flight of the Navigator (1986)

GoldenEye (1995)

Licence to Kill (1989)

Mare Nostrum

Mission: Impossible – Fallout

The Rains Came

Ready Player One

Solo

The Sword and the Rose

Tron (1982)

Wonder Man

All films in this category are declared winners. It would be unfair to compare a silent film to the newest Mission: Impossible film, so this is based on visual effects achievement in their respective time.

Worst Picture

Cimarron (1931)

The Curse of the Mummy’s Tomb (1964)

Die Another Day (2002)

It Happened at the World’s Fair (1963)

Kiss & Spell (2017, Vietnam)

The Lost World: Jurassic Park (1997)

Red Barry (1938 serial)

Rob Roy: The Highland Rogue

Tron

The Wacky World of Mother Goose

Holy mother of hell. Rankin and Bass, what did you DO?

Honorary Awards:

Albert R. Broccoli and Harry Saltzman, for stewarding the James Bond series and decades of entertainment

Peter Ellenshaw, for his esteemed career as a matte artist and visual effects wizard

Bill Gold (posthumously), for his artistry in movie poster design

Salt of the Earth (1954), for its courage to speak truth to power, persevering through the judgment of time despite being the only American film ever blacklisted

Vitaphone, for innovative achievements in sound recording

FILMS WITH MULTIPLE NOMINATIONS (excluding Worst Picture... 61)

Ten: 8½

Nine: The Heiress

Eight: Charade; The Philadelphia Story

Seven: Pyaasa

Five: All This, and Heaven Too; The Blue Angel; A Man for All Seasons; My Neighbors the Yamadas; Quo Vadis; Roma; Shoplifters; Stalker

Four: Alexander Nevsky; Cry, the Beloved Country; Dances with Wolves; Gojira; A Man Escaped

Three: The Black Stallion; Crazy Rich Asians; 49th Parallel; Grease; Imitation of Life; Incredibles 2; The Journey of Natty Gann; Perfect Blue; Pete’s Dragon; Phantom Thread; Piccadilly; Seven Brides for Seven Brothers; Splendor in the Grass; A Star Is Born; Stowaway; The Whole Town’s Talking

Two: The Beatles: Eight Days a Week – The Touring Years; The Black Hole; Black Panther; Crossfire; Dodge City; Eighth Grade; The Favourite; First Man; Floating Weeds; Girl Crazy; Gunfight at the O.K. Corral; Mare Nostrum; Mary and the Witch’s Flower; Mission: Impossible – Fallout; Moon Over Miami; National Velvet; Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse; The One and Only, Genuine, Original Family Band; The Post; The Rains Came; Solo; South Pacific; The Sword and the Rose; Uncle Tom’s Cabin; Warlock; Wonder Man; Won’t You Be My Neighbor?

WINNERS (excluding honorary awards and Worst Picture; 41)

3 wins: The Philadelphia Story

2 wins: 8½; The Heiress; Imitation of Life; Mission: Impossible – Fallout; Pyaasa; Seven Brides for Seven Brothers; Shoplifters

1 win: The Absent-Minded Professor; Alexander Nevsky; All This, and Heaven Too; The Black Hole; Black Panther; The Black Stallion; The Blue Angel; Charade; Crossfire; The Favourite; First Man; Flight of the Navigator; 49th Parallel; GoldenEye; Licence to Kill; Love Is a Many-Splendored Thing; A Man Escaped; A Man for All Seasons; Mare Nostrum; My Neighbors the Yamadas; Quo Vadis; The Rains Came; Ready Player One; Roma; Solo; Stalker; The Sword and the Rose; Tron; West Point; Wonder Man; Won’t You Be My Neighbor?

102 films were nominated in 26 categories.

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The End of Summer (1961)

Director: Yasujirô Ozu Writers: Kôgo Noda, Yasujirô Ozu Stars: Ganjirô Nakamura, Setsuko Hara, Yôko Tsukasa.

0 notes

Text

Cinema In The Rain | A Top 10 List

Cinema In The Rain | A Top 10 List

Follow @Distracted

For more Cinema In The Rain, you can check-out the full list of nominations here. This is my final selection of 10…

Buster Keaton in College, 1927… directed by Keaton and James W. Horne.

Machiko Kyô and Ganjirô Nakamura in Yasujirô Ozu’s Floating Weeds [1959]. Thanks to @PaulvonMitchell for this.

Hume Cronyn and Burt Lancaster in Brute Force [Jules Dassin, 1947]. And…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

The Son(1960)

0 notes

Photo

Kohayagawa-ke no aki, aka The End of Summer (1961), dir. Yasujirô Ozu.

#kohayagawa-ke no aki#the end of summer#yasujirô ozu#film#ganjirô nakamura#yôko tsukasa#akira takarada#chieko naniwa#michiyo aratama#reiko dan#keiju kobayashi#kyû sazanka#setsuko hara

1 note

·

View note

Photo

The End of Summer (Yasujirō Ozu, 1961)

#The End of Summer#Yasujirō Ozu#ozu#yasujiro ozu#back#faceless#long shot#interiors#setsuko hara#Ganjirô Nakamura#Yôko Tsukasa#yoko tsukasa#Michiyo Aratama#eiko Dan#Haruko Sugimura#aisuke Katô#kohayagawa-ke no aki#kohayagawa ke no aki#1961#chishu ryu#Chishū Ryū

303 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kwaidan (1964)

0 notes

Photo

The Lower Depths | Akira Kurosawa | 1957

Ganjirô Nakamura

26 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Floating Weeds (1959, Japan)

Director Yasujirô Ozu was tardy to synchronized sound in movies. With the introduction of sound in 1927, he did not make his first talkie until 1936. So too was he tardy with color. With black-and-white and color movies released together for decades, Ozu’s first color film came with Equinox Flower (1958), followed by Good Morning (1959; a remake of Ozu’s 1932 film I Was Born, But...). Later in 1959 another Ozu color talkie remake of one of his black-and-white silent films came to Japanese theaters: 1959′s Floating Weeds, a remake of A Story of Floating Weeds (1934). An already great original version is made better in this instance thanks to beautiful on-location shooting and a more mischievous sense of humor. In one of his most accessible pieces in his filmography, the cast includes many newer faces in this Ozu film. This is because Ozu’s contract with his home studio, Shochiku, had completed, and this next project was thanks to an invitation by Masaichi Nagata – the president of Daiei Film. Floating Weeds is made up largely of Daiei’s contracted actors, with one notable exception being Ozu mainstay Chishû Ryû.

Shot on the edge of the Kii Peninsula looking into Japan’s Inland Sea, Floating Weeds is a late-career testament to Ozu’s remarkable consistency as a director and storyteller, a crafter of dramas as compelling any drama could be – even when all the “showier” moments are never depicted, only discussed.

It is a sweltering summer in a lazy seaside town, with the occasional fishing vessel making its way through the harbor. A traveling kabuki troupe has arrived and they announce their new slate of shows with an impromptu parade and music. The troupe’s leader, Komajuro Arashi (Ganjirô Nakamura), is here not only to perform, but to see his old mistress, Oyoshi (Haruko Sugimura), and college-bound son, Kiyoshi (Hiroshi Kawaguchi). Oyoshi runs an intimate restaurant while Kiyoshi works at the local post office, building his savings before heading to university. Kiyoshi is told that Komajuro is his uncle – a secret that is threatened when Komajuro’s current mistress, Sumiko (Machiko Kyô), becomes jealous as he is not spending enough time with her during the daytime before performances. The film features a younger troupe actress named Kayo (Ayako Wakao) and the theater owner (Ryû). Character actors Kôji Mitsui and Haruo Tanaka also play bit roles.

The screenplay, co-written by Ozu and partner-in-crime Kôgo Noda, leans into the melodrama moreso than most Ozu films. Central to Floating Weeds are its characters speaking about permanence and belonging – like the original silent film version, the title is derived from the saying, “Floating weeds, drifting down the leisurely river of our lives.” For this film’s characters, it is difficult to always be traveling, living within the mercy of ticket sales, although the company of fellow troupe members makes the difficulty worth it. Komajuro is not an authoritarian boss to his fellow actors, but he is unable to see situations through others’ perspectives. Why are they not more like me, he wonders, as he is repeatedly surprised that the other members of his troupe imagine what life could be like without traveling across Japan. He cares for his fellow actors to the extent that everyone depends on each other for their roaming lifestyle. To his “nephew”, secrets remains unspoken behind an avuncular act that occurs every few years – Komajuro does not want Kiyoshi to follow or replicate a life that is dependent, rootless. It is how he remains Kiyoshi’s father, because he knows of no other way to do so. This concentration on Komajuro does come at the partial expense of understanding Oyoshi. It is no debate that she has been a wonderful mother to her son, but she is essentially a single parent that receives the occasional payment from an absent father. Does she harbor any spurned feelings for this arrangement? Is she content with what life has become or does she yearn for something else? Ozu and Noda never explore this quite enough.

Cinematic ellipsis is found in most of Ozu’s work, leaving the viewer to work together what has occurred in between scenes. Less-experienced Ozu viewers will be caught off-guard, claiming that characters seem to lack motivation, but Ozu has never been one to show the details of a steamy date, pomp and circumstance, or tearful departing words. As Ozu’s career progressed, his use of ellipsis generally increased – he became less interested in narrative flow, more interested in human perceptions and insights at a given moment. When Sumiko’s machinations involving Kayo are revealed to Komajuro and when Oyoshi tells her son about who his “uncle” is, all that has been built up to these dramatic reveals are moments of quiet or lightly reflective conversation. Melodrama here is empowered through objectively-shot conversation, oftentimes casual rumor-mongering or quotidian remarks about how the day has been. The static pillow shots in between scenes (Ozu’s innovation where, after a lengthy scene, he might show us a few seconds of the corner of a building or a shot of the sea’s edge or the neon lights of a narrow street to allow the viewer to reflect on what has just occurred) serve as periods do in writing. The idea of a scene may be picked up later, or maybe it has served its purpose in defining to the viewer the characters who gradually show who they are across the film (and in a handful of cases, minor characters who appear once or twice – to Ozu, even these characters have a significant role to the ideas the film expresses).

There are times where – other than the character names, the setting, the synchronized sound, and the color photography – Floating Weeds seems indistinguishable from A Story of Floating Weeds (the two films have similar opening pillow shots). By 1959, Ozu’s era of experimentation had long since concluded. Ironing out what became his signature style in the 1920s and 1930s, the tatami shot aesthetic (where the camera would be placed low to the ground, pointed slightly upwards) and the pillow shot became his trademarks. The ellipsis was a given (as was passable to terrible child dramatic acting, which Ozu never seemed to improve on – not as if children were essential to Ozu’s dramas). Differentiating between A Story of Floating Weeds and Floating Weeds is that the latter, mostly in its opening half, has a broader sense of humor, playfulness – one running joke, more easily understood by those familiar with Japanese filmmaking or culture at-large, is that this kabuki troupe is depicted as anything but a high-quality entourage. It is a welcome reprieve to what might otherwise have been a hard-hitting domestic drama with no easy resolutions. This might be because that Daiei Film was less associated with melodramas than Shochiku.

In his first Ozu film, cinematographer and Daiei contractee Kazuo Miyagawa (1950′s Rashômon, 1965′s Tokyo Olympiad) always keeps the camera static – as one would also expect from any Ozu feature. It is a beautifully shot movie, perhaps most notably for the following sequence. As Komajuro and Sumiko move in an argument that is carried across the street that separates them, the camera does not pan with them. Notice where the camera is located as the characters speak: not over anyone’s shoulder, but a set distance from each character as they make their points. The second way this is shot has the camera reverting back to showing us part of the rain-splattering street, far back enough so that neither character physically dominates the frame. This latter framing is an extraordinarily complex composition filled with vertical lines that almost threaten the frame’s geometry, but it serves to lend objectivity to the two characters arguing their views – so that cinematography does not have much say in giving unwanted sympathy to either character.

youtube

Composer Takanobu Saitô (1953′s Tokyo Story, Equinox Flower) usually had little of interest to do – musically, cinematically – in his scores for Ozu’s films. Flowing, pastoral string melodies without motifs are typically played over the opening credits. But this is, if only for one cue, an unusual score for Saitô. In the scene where the troupe enters town for the first time, Saitô has composed a cue where the melodies reside in the woodwinds and where percussion is prominent. It is carnival-like music, which may remind some Italian cinema aficionados of the exuberance of Nino Rota’s scores for ‘50s and ‘60s Fellini films.

Lacking the absolute serenity of many Ozu films, Floating Weeds is nevertheless an exemplar of Ozu’s inimitable style and how emotionally and philosophically effective it can be. Because it has more above-the-surface melodrama than most in Ozu’s filmography, Floating Weeds is a possible starting point for any neophytes to a type of filmmaking far removed from exposition-delivering and overt dramatics of mainstream Western cinema (not that all Japanese cinema has bucked Western influences – a vast majority of the most popular contemporary Japanese movies, live-action and animated, take notes from Hollywood and not Ozu). For those who make Floating Weeds their first or one of their first Ozu films, the film serves as an introduction to some of the unifying ideas in his entire filmography. Individual lives are inescapably altered by others. To repudiate or fail to intuit that truth is to invite suffering; to intuit that truth but not attempt to understand others’ actions is hubris.

My rating: 9/10

^ Based on my personal imdb rating. My interpretation of that ratings system can be found here.

#Floating Weeds#Yasujiro Ozu#Ganjiro Nakamura#Machiko Kyo#Ayako Wakao#Hiroshi Kawaguchi#Haruko Sugimura#Hitomi Nozoe#Chishu Ryu#Kogo Noda#Kazuo Miyagawa#Takanobu Saito#TCM#My Movie Odyssey

6 notes

·

View notes