#Kogo Noda

Photo

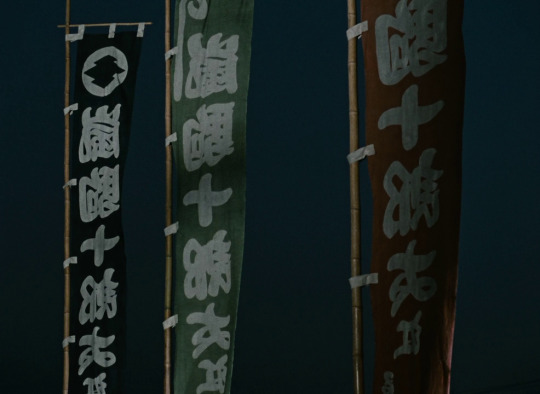

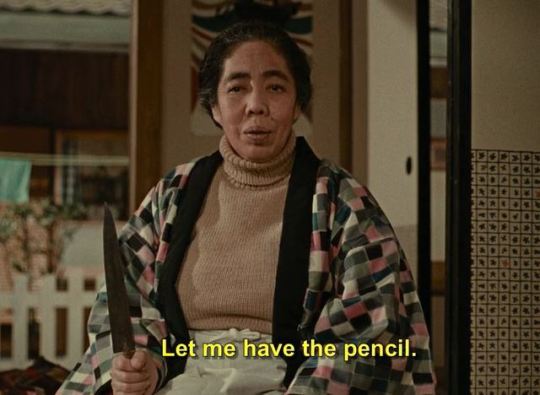

浮草 (Ukigusa - Floating Weeds), 1959.

Dir. Yasujirō Ozu | Writ. Kogo Noda & Yasujirō Ozu | DOP Kazuo Miyagawa

74 notes

·

View notes

Text

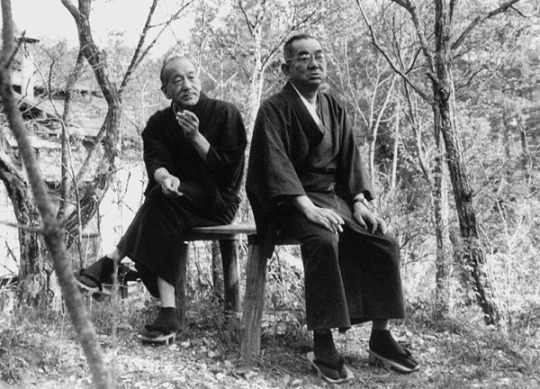

Kogo Noda, November 19, 1893 – September 23, 1968.

With Yasujiro Ozu.

48 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Beulah Bondi and Victor Moore in Make Way for Tomorrow (Leo McCarey, 1937)

Cast: Beulah Bondi, Victor Moore, Fay Bainter, Thomas Mitchell, Porter Hall, Barbara Read, Maurice Moscovitch, Elisabeth Risdon, Minna Gombell, Ray Mayer, Ralph Remley, Louise Beavers, Louis Jean Heydt. Screenplay: Viña Delmar, based on a novel by Josephine Lawrence and play by Helen Leary and Nolan Leary. Cinematography: William C. Mellor. Art direction: Hans Dreier, Bernard Herzbrun. Film editing: LeRoy Stone. Music: George Antheil, Victor Young.

As the music ("Let Me Call You Sweetheart") swelled, and the train taking her husband to California pulled out of the station leaving Lucy Cooper (Beulah Bondi) alone on the platform, I muttered, "Please end it here. Please end it here." And so Leo McCarey, bless him, did. He could have, as the studio wanted, moved on to a mawkish conclusion, pulling a sentimental rabbit out of the hat in which their children relented and found a place where Barkley (Victor Moore) and Lucy Cooper could live together, but thank whatever gods preside over cinema, he didn't. I thought, before my reading confirmed it, that Yasujiro Ozu must have seen Make Way for Tomorrow -- or as seems to have happened, his scenarist Kogo Noda did. This is one Hollywood picture from the '30s and '40s that has its head on straight, keeping its heart in the right place. The film gives us complex, fallible characters instead of sugary and vinegary stereotypes: The elder Coopers are as much to blame for the predicament in which they find themselves as their children are for not finding a satisfactory way to resolve it. As an aged parent, one who once faced the problem of an aged parent, I find the film's willingness not to lay blame on anyone refreshing: Barkley Cooper should not have allowed himself to get in the financial difficulty in which he finds himself; he and Lucy should have come clean to the offspring about their money difficulties long before they did. And though it's easy to see the children as hard-hearted and selfish -- the film does tilt a little more in that direction than it might -- what we see on the screen makes clear that housing Lucy and Barkley is a little harder than it ought to be. She seems oblivious to the burdens she puts on George (Thomas Mitchell) and Anita (Fay Bainter), and he is a cantankerous handful for Cora (Elizabeth Risdon) and Bill (Ralph Remley), refusing to follow the doctor's instructions. McCarey and his wonderful cast handle all of this superbly, with McCarey not only stubbornly refusing to provide a conventional movie ending, but also withholding some information a lesser director would have made much of, such as what Rhoda (Barbara Read) did when she disappeared that night, or what Barkley said to his daughter on the telephone when he informed her that he and Lucy weren't coming to their farewell dinner. (I think it's better that we don't know what he told her to do with that roast she was planning to serve.) A small, surprising treat of a movie.

gifs from manderley

7 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Kogonada immigrated from South Korea as a child, and was raised in Indiana and Chicago.[4] As of 2022, he resides in Los Angeles with his wife and two sons.

I like Chris Marker's idea about your work being your work. I’ve also never identified much with my American name, which always feels a little strange to see or hear ... And I'm quite fond of heteronyms.

His pseudonym is taken from Kogo Noda, a frequent screenwriter of Yasujirō Ozu's films.

"If I’m honest, the pseudonym was about being an Asian-American too. There is something about being an immigrant in America and having the power to name yourself."

Kogonada - Wikipedia

1 note

·

View note

Photo

@tcmparty live tweet schedule for the week beginning Monday, August 16, 2021. Look for us on Twitter…watch and tweet along…remember to add #TCMParty to your tweets so everyone can find them :) All times are Eastern.

Thursday, August 19 at 8:00 p.m.

LATE SPRING (1949)

A spinster attached to her father makes a change in her life with the help of her sister.

#schedule#yasijiro ozu#setsuko hara#summer under the stars#suts#jun osami#haruko sugim#kogo noda#1940s#world cinema#classic movies#classic film#tcm party#live tweet#turner classic movies

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

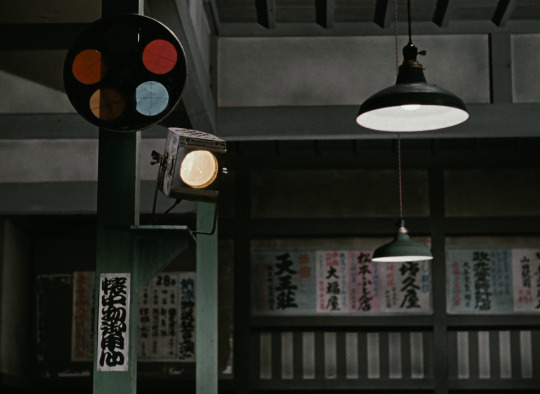

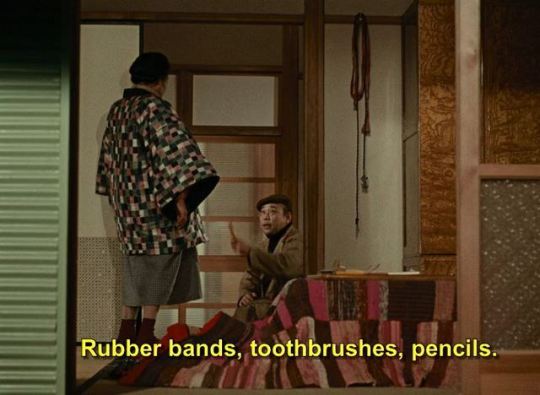

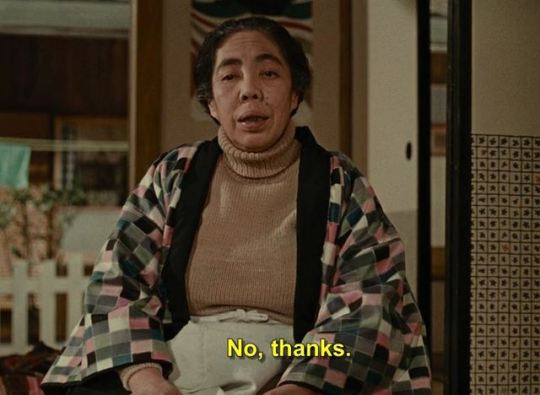

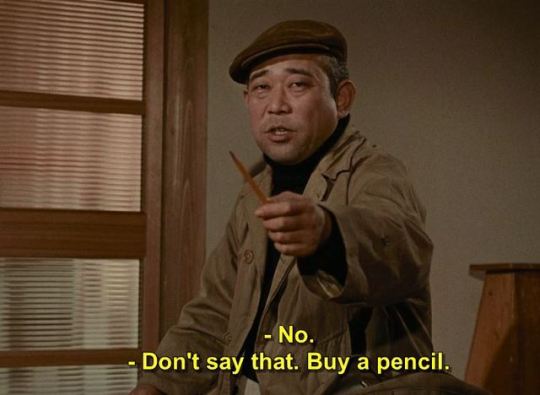

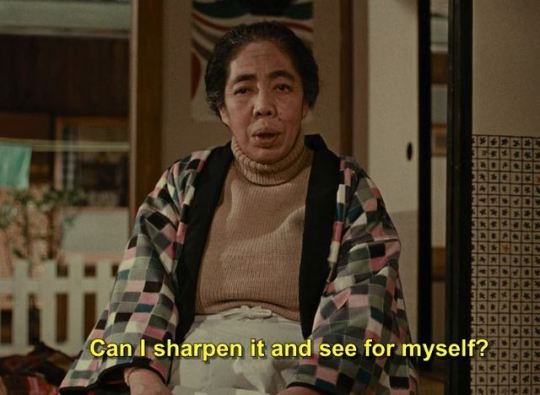

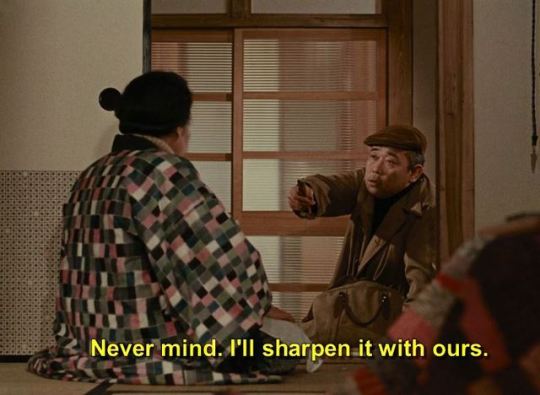

お早よう, 1959

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Floating Weeds (1959, Japan)

Director Yasujirô Ozu was tardy to synchronized sound in movies. With the introduction of sound in 1927, he did not make his first talkie until 1936. So too was he tardy with color. With black-and-white and color movies released together for decades, Ozu’s first color film came with Equinox Flower (1958), followed by Good Morning (1959; a remake of Ozu’s 1932 film I Was Born, But...). Later in 1959 another Ozu color talkie remake of one of his black-and-white silent films came to Japanese theaters: 1959′s Floating Weeds, a remake of A Story of Floating Weeds (1934). An already great original version is made better in this instance thanks to beautiful on-location shooting and a more mischievous sense of humor. In one of his most accessible pieces in his filmography, the cast includes many newer faces in this Ozu film. This is because Ozu’s contract with his home studio, Shochiku, had completed, and this next project was thanks to an invitation by Masaichi Nagata – the president of Daiei Film. Floating Weeds is made up largely of Daiei’s contracted actors, with one notable exception being Ozu mainstay Chishû Ryû.

Shot on the edge of the Kii Peninsula looking into Japan’s Inland Sea, Floating Weeds is a late-career testament to Ozu’s remarkable consistency as a director and storyteller, a crafter of dramas as compelling any drama could be – even when all the “showier” moments are never depicted, only discussed.

It is a sweltering summer in a lazy seaside town, with the occasional fishing vessel making its way through the harbor. A traveling kabuki troupe has arrived and they announce their new slate of shows with an impromptu parade and music. The troupe’s leader, Komajuro Arashi (Ganjirô Nakamura), is here not only to perform, but to see his old mistress, Oyoshi (Haruko Sugimura), and college-bound son, Kiyoshi (Hiroshi Kawaguchi). Oyoshi runs an intimate restaurant while Kiyoshi works at the local post office, building his savings before heading to university. Kiyoshi is told that Komajuro is his uncle – a secret that is threatened when Komajuro’s current mistress, Sumiko (Machiko Kyô), becomes jealous as he is not spending enough time with her during the daytime before performances. The film features a younger troupe actress named Kayo (Ayako Wakao) and the theater owner (Ryû). Character actors Kôji Mitsui and Haruo Tanaka also play bit roles.

The screenplay, co-written by Ozu and partner-in-crime Kôgo Noda, leans into the melodrama moreso than most Ozu films. Central to Floating Weeds are its characters speaking about permanence and belonging – like the original silent film version, the title is derived from the saying, “Floating weeds, drifting down the leisurely river of our lives.” For this film’s characters, it is difficult to always be traveling, living within the mercy of ticket sales, although the company of fellow troupe members makes the difficulty worth it. Komajuro is not an authoritarian boss to his fellow actors, but he is unable to see situations through others’ perspectives. Why are they not more like me, he wonders, as he is repeatedly surprised that the other members of his troupe imagine what life could be like without traveling across Japan. He cares for his fellow actors to the extent that everyone depends on each other for their roaming lifestyle. To his “nephew”, secrets remains unspoken behind an avuncular act that occurs every few years – Komajuro does not want Kiyoshi to follow or replicate a life that is dependent, rootless. It is how he remains Kiyoshi’s father, because he knows of no other way to do so. This concentration on Komajuro does come at the partial expense of understanding Oyoshi. It is no debate that she has been a wonderful mother to her son, but she is essentially a single parent that receives the occasional payment from an absent father. Does she harbor any spurned feelings for this arrangement? Is she content with what life has become or does she yearn for something else? Ozu and Noda never explore this quite enough.

Cinematic ellipsis is found in most of Ozu’s work, leaving the viewer to work together what has occurred in between scenes. Less-experienced Ozu viewers will be caught off-guard, claiming that characters seem to lack motivation, but Ozu has never been one to show the details of a steamy date, pomp and circumstance, or tearful departing words. As Ozu’s career progressed, his use of ellipsis generally increased – he became less interested in narrative flow, more interested in human perceptions and insights at a given moment. When Sumiko’s machinations involving Kayo are revealed to Komajuro and when Oyoshi tells her son about who his “uncle” is, all that has been built up to these dramatic reveals are moments of quiet or lightly reflective conversation. Melodrama here is empowered through objectively-shot conversation, oftentimes casual rumor-mongering or quotidian remarks about how the day has been. The static pillow shots in between scenes (Ozu’s innovation where, after a lengthy scene, he might show us a few seconds of the corner of a building or a shot of the sea’s edge or the neon lights of a narrow street to allow the viewer to reflect on what has just occurred) serve as periods do in writing. The idea of a scene may be picked up later, or maybe it has served its purpose in defining to the viewer the characters who gradually show who they are across the film (and in a handful of cases, minor characters who appear once or twice – to Ozu, even these characters have a significant role to the ideas the film expresses).

There are times where – other than the character names, the setting, the synchronized sound, and the color photography – Floating Weeds seems indistinguishable from A Story of Floating Weeds (the two films have similar opening pillow shots). By 1959, Ozu’s era of experimentation had long since concluded. Ironing out what became his signature style in the 1920s and 1930s, the tatami shot aesthetic (where the camera would be placed low to the ground, pointed slightly upwards) and the pillow shot became his trademarks. The ellipsis was a given (as was passable to terrible child dramatic acting, which Ozu never seemed to improve on – not as if children were essential to Ozu’s dramas). Differentiating between A Story of Floating Weeds and Floating Weeds is that the latter, mostly in its opening half, has a broader sense of humor, playfulness – one running joke, more easily understood by those familiar with Japanese filmmaking or culture at-large, is that this kabuki troupe is depicted as anything but a high-quality entourage. It is a welcome reprieve to what might otherwise have been a hard-hitting domestic drama with no easy resolutions. This might be because that Daiei Film was less associated with melodramas than Shochiku.

In his first Ozu film, cinematographer and Daiei contractee Kazuo Miyagawa (1950′s Rashômon, 1965′s Tokyo Olympiad) always keeps the camera static – as one would also expect from any Ozu feature. It is a beautifully shot movie, perhaps most notably for the following sequence. As Komajuro and Sumiko move in an argument that is carried across the street that separates them, the camera does not pan with them. Notice where the camera is located as the characters speak: not over anyone’s shoulder, but a set distance from each character as they make their points. The second way this is shot has the camera reverting back to showing us part of the rain-splattering street, far back enough so that neither character physically dominates the frame. This latter framing is an extraordinarily complex composition filled with vertical lines that almost threaten the frame’s geometry, but it serves to lend objectivity to the two characters arguing their views – so that cinematography does not have much say in giving unwanted sympathy to either character.

youtube

Composer Takanobu Saitô (1953′s Tokyo Story, Equinox Flower) usually had little of interest to do – musically, cinematically – in his scores for Ozu’s films. Flowing, pastoral string melodies without motifs are typically played over the opening credits. But this is, if only for one cue, an unusual score for Saitô. In the scene where the troupe enters town for the first time, Saitô has composed a cue where the melodies reside in the woodwinds and where percussion is prominent. It is carnival-like music, which may remind some Italian cinema aficionados of the exuberance of Nino Rota’s scores for ‘50s and ‘60s Fellini films.

Lacking the absolute serenity of many Ozu films, Floating Weeds is nevertheless an exemplar of Ozu’s inimitable style and how emotionally and philosophically effective it can be. Because it has more above-the-surface melodrama than most in Ozu’s filmography, Floating Weeds is a possible starting point for any neophytes to a type of filmmaking far removed from exposition-delivering and overt dramatics of mainstream Western cinema (not that all Japanese cinema has bucked Western influences – a vast majority of the most popular contemporary Japanese movies, live-action and animated, take notes from Hollywood and not Ozu). For those who make Floating Weeds their first or one of their first Ozu films, the film serves as an introduction to some of the unifying ideas in his entire filmography. Individual lives are inescapably altered by others. To repudiate or fail to intuit that truth is to invite suffering; to intuit that truth but not attempt to understand others’ actions is hubris.

My rating: 9/10

^ Based on my personal imdb rating. My interpretation of that ratings system can be found here.

#Floating Weeds#Yasujiro Ozu#Ganjiro Nakamura#Machiko Kyo#Ayako Wakao#Hiroshi Kawaguchi#Haruko Sugimura#Hitomi Nozoe#Chishu Ryu#Kogo Noda#Kazuo Miyagawa#Takanobu Saito#TCM#My Movie Odyssey

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ohayô, 1959, dir. Yasujiro Ozu

21 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Tokyo Story (東京物語 Tōkyō Monogatari) (1953)

Dir: Yasujirō Ozu

DOP: Yūharu Atsuta

“Children don't live up to their parents' expectations. Let's just be happy that they're better than most.”

#tokyo story#東京物語#tokyo monogatari#yasujiro ozu#kogo noda#chishu ryu#chieko higashiyama#setsuko hara#haruko sugimura#so yamamura#kuniko miyake#kyoko kagawa#eijiro tono#nobuo nakamura#elderly#reitred#family#couple#children#aging#age#old age#selfishness#mortality#japan#japanese#tokyo#social realism#drama#film

19 notes

·

View notes

Photo

浮草 (Ukigusa - Floating Weeds), 1959.

Dir. Yasujirō Ozu | Writ. Kogo Noda & Yasujirō Ozu | DOP Kazuo Miyagawa

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tokyo Story (1953) Review :-

The Elderly Hirayama couple take a trip to visit their adult children in Tokyo , their children however don't have much time to spend with their aged parents , as it leads to their daughter in law Noriko the widow of their younger son to spend time with her in-laws. As the movie progresses the somber mood infuses , revealing the death of Hirayama's son who went missing in the Asia pacific war , and how their children have grown apart . Yasujiro Ozu and Kogo Noda's writing flawlessly divulges the forthcoming and axiomatic relationship of a parent and child . The acting in the film flames out , as though the actors expose repetitive reactions . With only Haruko Sugimura delivering an exceptional performance of the elder selfish daughter . Nevertheless the Coda of the film imparts us with a sympathetic ending , and an impending solitude .

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Machiko Kyo and Ganjiro Nakamura in Floating Weeds (Yasujiro Ozu, 1959)

Cast: Ganjiro Nakamura, Machiko Kyo, Ayako Wakao, Hiroshi Kawaguchi, Haruko Sugimura, Hitomi Nozoe, Chishu Ryu, Koji Mitsue, Haruo Tanaka. Screenplay: Yasujiro Ozu, Kogo Noda, based on a screenplay by Tadao Ikeda. Cinematography: Kazuo Miyagawa. Production design: Hideo Matsuyama. Film editing: Toyo Suzuki. Music: Takanobu Saito.

The remake of his 1934 silent, A Story of Floating Weeds, Yasujiro Ozu's Floating Weeds adds not only the technological advances of sound and color, but also shows the maturing of Ozu's sensibility. It's clear that the director feels a deep identification with Komajuro (Ganjiro Nakamura), the "master" of the group of traveling players, who finds himself worried not only about his responsibility to the actors but also about his responsibility to his unacknowledged son, Kiyoshi (Hiroshi Kawaguchi), now that the young man is of an age to make the kind of mistakes Komajuro has made. The wonderful Machiko Kyo also brings great depth to the role of Sumiko, an actress in the troupe and Komajuro's current mistress. When she susses out the fact that Komajuro has a former mistress, Oyoshi (Haruko Sugimura), in the town where they're currently performing, and that Kiyoshi is his son by Oyoshi, she takes revenge by having the pretty young actress Kayo (Ayako Wakao) seduce the young man. It's a fairly conventional plot, to be sure, devised for the earlier film by Ozu and Tadao Ikeda, but it reverberates beautifully with the film's theme: a celebration of acting and all that it involves. Komajuro, after all, has been playing the role of Kiyoshi's "uncle," with Oyoshi's aid. And Kayo's acting as the seductress turns into a real love affair. Above all, though, it's the quiet mastery of film that shines through every frame of Ozu's work, made magical by Kazuo Miyagawa's cinematography and Hideo Matsuyama's production design. One of the great works by one of film's great humanists.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kogo Noda, November 19, 1893 – September 23, 1968.

With Yasujiro Ozu.

3 notes

·

View notes

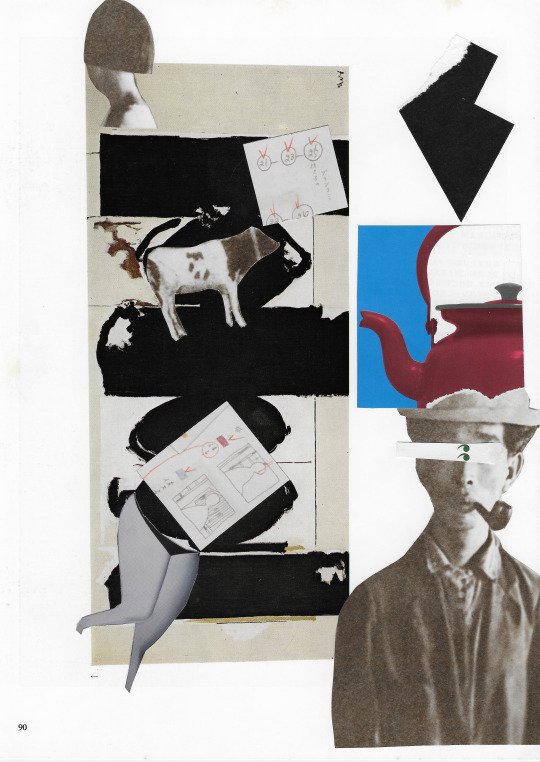

Photo

+Three Dedicated to Ozu is a play on the late great film director Abbas Kiarostami’s film, Five Dedicated to Ozu. It is a film made of only five static long shots (well except 1) where if you get the aesthetics can see why it is a tribute to (IMHO) the greatest film director Ozu Yasujiro. Here I took two analog photos and made one paper collage dedicated to Ozu. The paper collage is made of elements from the 50th anniversary exhibition brochure they had for him in 2013 in Tokyo with some pieces from vintage magazines I found in the trash that my neighbor threw out. The photo of the bottles recalls the script writing process of Ozu and his screenwriter Noda Kogo who based the value of their scripts on how much nihon-shu they drank doing it, lining the empty bottles in front the house. The second photo relates to how he used bicycles in Late Spring (1949) that for us, the audience, signified a love that never was. Bicycles in static long shot as a motif is something I used in my upcoming short film, Obscure, that should be out by Spring~

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

A MEDITATIVE EXPERIENCE

Tokyo Story

Director: Yasujiro Ozu

Starring or score: 99% Rotten Tomatoes

Genre: Drama

Tokyo Story (Tôkyô monogatari) is generally regarded as one of the greatest films ever made. It was directed by Ozu and also written by himself and Kogo Noda, a Japanese screenwriter. Ozu created films that were excessively Japanese. Because of this, his work was only recognised after his death in the 1960’s by Western countries. People starring in Tokyo Story were Chishū Ryū, Setsuko Hara, Chieko Higashiyama, Haruko Sugimura and So Yamamura. Some of these actors played in a few of Ozu’s films. Ozu created films that were calm, contemplative in nature. Often dealing with subjects like family life drama’s. Tokyo Story is a magnificent piece of art.

Tokyo Story’s plot is completely authentic in the fact that it is very minimal. Ozu takes ordinary life and turns it into a painting of sorts. A meditative experience. An elderly couple visits their children in Tokyo. Their children at first are excited to see them but they inevitably become a burden. The couple becomes aware of these feelings and begin their journey back home. These everyday events are told in a melancholic, beautifully crafted way that makes up for the fact that there is not much happening on screen. Because the film lacks a real plot drive, the film often feels too much for one sitting. Although we as viewers get so immersed in this world. A mere tea break will suffice.

The dominant theme of Tokyo Story is the generational conflict between parents and their children. At one point Noriko (Setsuko Hara) is asked. “Isn’t life disappointing?” She smiles a smile of pain but somehow found joy in the mundane through all the pain. She answers “Yes, it is”. Tokyo Story in its beauty is able to take your hurts and disappointments and transform it into art.

The visuals on screen were predominantly Japanese. Shot in Japanese homes, eating Japanese food and drinking Japanese drinks. Ozu created these characters to be very old fashioned in clothing choices like wearing kimonos and in culture. Ozu mostly used static shots to tell this story. The amount of times he moved the camera can be counted on one hand. The shots had precise composition and visual symmetry. The characters are often locked in frame by parallel lines. Ozu’s tone of the film was mostly somber and quiet. In times when he did add music it was lighthearted and immersive.

I would rate Tokyo Story a 9 out of 10. Tokyo Story is a must see for every appreciator for the art of film. A must see for the wounded and a must see for the contemplative.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

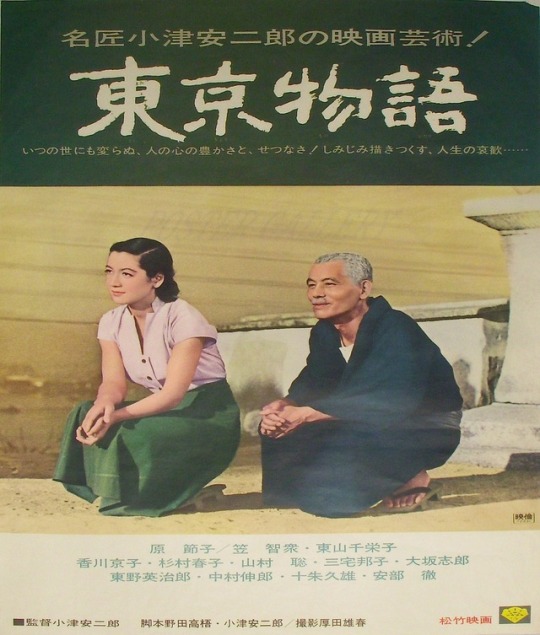

Yasujiro Ozu- Tokyo monogatari (1953)

Para la publicación nº 700 del blog que exije algo especial ante el fetichismo de los números redondos, vamos con una película monumental:

Tokyo monogatari es una película de una belleza visual inaudita, construida con paciencia y metódico sentido estético que desgrana plano a plano la quintaesencia del pueblo nipon y de su cine, preciosista e imponente.

Los paisajes (abiertos y cerrados) y esos encuadres fijos por el cual desfilan sus personajes, son el lenguaje que encontró y uso Yasujiro Ozu para ponernos a contemplar. La mayor parte de su decir esta implícita en esas imágenes de cálida y cautivadora factura en la que somos testigos de los problemas comunes de un mundo común.

La atmósfera que adquiere la cinta con su blanco y negro armonioso y cuidadosamente iluminado nos guiaran ante los problemas usuales del cine del maestro japones: La vejez, la pobreza, el costumbrismo, la tradición, la modernidad, la familia, la soledad, la desesperanza, el alcoholismo y el tercer ojo.

La película cuenta la historia de una pareja de ancianos que viajan desde Onomichi a Tokyo para visitar a su hijo y su familia. Al llegar, se encuentran con que tanto su hijo como su nuera están ocupados casi todo el tiempo y casi que no pueden compartir momentos. A partir de esto, deciden mandarlos a un hotel-balneario para que puedan ser mejor atendidos pero los viejos no se sienten a gusto. El olor a juventud no les repele, pero si les hace sentir excluidos, fuera del sistema. De esta forma encuentran amparo en su otra nuera, quien enviudase en la Segunda Guerra Mundial y que se las arregla para darle a los ancianos su tiempo y su amor. El padre también aprovecha su visita a Tokyo para re-encontrarse con dos viejos amigos y emborracharse pese a haber abandonado el vicio desde hacia tiempo. Así, de a fragmentos que ilustran la soledad del ser humano y su infranqueable intimidad, el fantasma de le guerra aun discurre en el Tokyo industrial que tan bien imprime en su celuloide Yasujiro Ozu. La gente se siente decepcionada de sus vida, los errores cometidos pesan en sus espaldas y la perdida del carácter espiritual les duele profundamente.

Uno de los pocos travellings de toda la carrera cinematográfica de Ozu se encuentra en esta película, en su centro, en su núcleo. La cámara se desplaza frente a un muro y nos muestra a los dos protagonistas casi de espaldas, sentados uno al lado del otro bañados por un halo de nostalgia resuelto y mágico. Un despertar de las emociones, un quiebre en la historia.

Una película reluciente por donde se la mire.

Pais: Japon

Director: Yasujiro Ozu

Guion: Yasujiro Ozu & Kôgo Noda

Reparto: Chishu Ryu, Chiyeko Higashiyama, Setsuko Hara, So Yamamura, Haruko Sugimura, Kinoko Niyake, Kyoko Kagawa

Musica: Takinori Saito

Genero: Drama

TRAILER

DESCARGAR

SUBTITULOS

#yasujiro ozu#tokyo monogatari#cuentos de tokyo#tokyo#japon#1953#japan#pelicula#movie#film#drama#familia#vejez#700#takinori saito#chishu ryu#kogo noda

0 notes