#Geocities Institute

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

And right from Olia (of, among other things, the Geocities Institute that runs oneterabyteofkilobyteage), a collection of Geocities dogs:

Enjoy!

original url http://www.geocities.com/nancyandfrankie/

last modified 2008-09-19 14:15:43

617 notes

·

View notes

Text

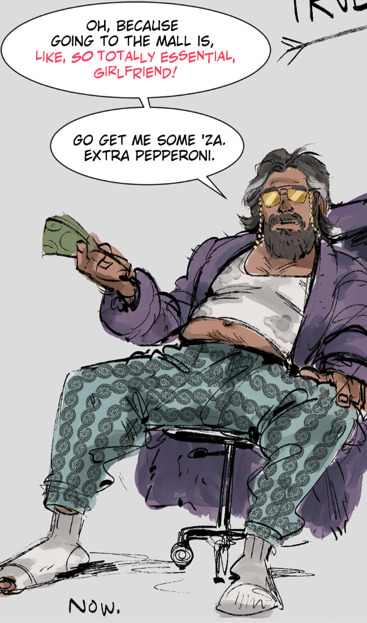

supe npc (Then and Now) for a MASKS: A New Generation game I'm gonna be running for some friends. TrueStrike, mentor to the protégé character. left was him before he disappeared from the public eye after the intense ridicule brought on from accidentally killing destroying a city institution: the giant, beloved balloon mascot of the city's favorite donut shop (Dino Donut, the D-Rex, of Dino Donut), traumatizing a generation of children who loved it and all the adults who grew up with it. there were a lot of kids screaming, crying, The Day Dino Donut Died. The Dino Donut balloon has since been replaced with a statue of a hipper version of the D-Rex that wears a backwards baseball cap and everyone hates it.

TrueStrike currently lives inside a storage unit, monitoring the city with all his high tech computers as he sinks deeper into paranoia and self-pity, missing his ex-wife and kid, and tries not to spend too much time refreshing the FUCK TRUESTRIKE geocities page. he mostly uses his protégé to get him pizza.

#masks a new generation#masks: overlook#truestrike#superhero#original character#original characters#npc#he is an absolute disaster and i am obsessed with him#we have yet to play but we have been over the moon with the life and death of Dino Donut#he is so hot then and now i'm sorry but i'm so (BRAIN RATTLES)#fuck i forgot to put his logo on his chest. oopsie.#he can't explain he killed Dino Donut protecting one of the PCs with a specific exploitable power#so he just comes off as more callous and unlikeable#reporters did eventually catch him angrily ranting that balloons don't have a soul but he does#antonio salvo#if you read all of this you get a gold star#masks ttrpg#pbta

105 notes

·

View notes

Text

What is the logic behind the selection ?

The GeoCities website is organized into various categories.

"Athens" is considered an important category within the site.

This category includes keywords such as:

Education

Literature

Poetry

Philosophy

Based on these keywords, a site was selected that aligns with the theme of "Athens."

The selected site is located near institutions relevant to these themes, such as:

The Architecture College of Athens

A library nearby

0 notes

Text

Guess who's anniversary it is!! Here are some web graphics if you celebrate :)

Badges

Backgrounds

Don't use the images above for your background, unless you plan on scaling them down: they're just the uncompressed versions, the images below work better.

Page art (I didn't make any of these, I just compressed them. click the full-size art to see the origin link.)

If you couldn't figure it out, it's Journey Into Imagination's 40th. Happy Anniversary!

#pixel art#retro#2000s web#geocities#old web#90s web#web 1.0#retro web#walt disney world#disney world#epcot#journey into imagination#figment#epcot center#imagination institute#website stuff#web graphics#88x31#88x31 buttons#disney parks

65 notes

·

View notes

Text

The worst thing people think about the early web is that they think most of the users were making their own pages rather than most of the users simply reading things already on a page. Because that's the thing, most of the user base was passive consumers of the media placed before them. Which largely came from either a large business or a large educational institution - itself often essentially a business because many were private.

And then if they wanted to interact with that page they read? Usually you would have to email the author, and wait for them respond. Or for news sites and business and even many pages on educational institutions, wait for a sales or pr rep to respond. Sometimes you could exchange chat messages with them instead, but that often required just as much waiting for them to be online to be able to respond, or at least not busy with something else.

People love to pretend that there's less common user made content online then in the past but honestly the proportion that comes from everyday people vs professionals has never stopped increasing. It's just that we have this weird bias that "social media" and not having private subdirectories or subdomains or full domains makes it lesser than things that had their own.

Like the notion that say .edu/~username/index.htm or geocities.com/Area/Neighborhood/0000/ or username.domain is inherently more of a contribution, more of an act of creation than something at .com/post/99876543876447664332256/ or .com/username/status/189345917944610816

But the geocities account was just as much as say a Tumblr account, a free but small space granted on a massive corporation's servers with the goal of attracting investment and ad revenue from others. The small user directory on a college's servers was, as much as a set of tweets from someone average, just a place allocated within a large institution. and subject to arbitrary removal if the provider felt you were causing a problem!

And of course when you weren't riding on free allowances from corporations or large institutions, back then hosting your own site was massively more expensive. Especially when your little thing got noticed by a large group of other people - often merely hundreds or thousands would do it - and suddenly your content became unviewable forever more because your hosting demanded a massive payment for increased traffic or simply shut off access until the next billing period cuz you filled up your allotment. Popularity could cause sudden bills in the thousands of dollars to keep your little web thing going, and of course that's 90s dollars, or even early 2000s dollars, so it hit the wallet even harder.

And when that popularity hit on free hosting of course, you'd be equally likely to get kicked off the service or have your web presence throttled severely for daring to make something popular. Between free hosting booting you and paid hosting essentially holding sites ransom for high bills, tens of thousands of sites and pages got destroyed forever within days of hitting a large web portal or newsletter's site of the day/week/etc list.

And these frequent destructions of pages were part of why average people weren't into posting their own stuff on the web. Because they were afraid of the risks in putting in the work to make something when it might drop them into a heavy financial burden or deletion/blocking of said work.

That's before we get into the way you'd need fairly expensive equipment to be online or an organization on hand willing to provide it. The way that online access time was usually metered by the hour or minute, with "unlimited" monthly plans often being quite a bump in upfront cost each month. These factors heavily gated who could participate at all, and who could afford the time to actively create their own web content whether writing or art or sound etc. Lots of people developed workflows for getting the most efficient pattern of opening things they might want to read for the day and heading right back offline to save on billed time, preparing any such input as new emails or replies to a newsgroup while offline, to be sent in the most efficient manner in another short window of online time.

Naturally these habits took different forms in different situations. The person working in a networked office who would only really do online things during work hours and might not even have an internet connection at home. The people who had to go to the library for short blocks of internet time. College kids who might have free access in their dorm room or only at special facilities in various places on campus, which usually wouldn't be open 24/7 - the famous September phenomenon of internet usage jumping during the main semesters of North American college attendance that would fall off at major break periods and the summer. The random people who'd gotten a home internet connection but still had to budget access carefully. Really, it's all a lot more messy than the modern mode where the majority of the population has near constant access in some form!

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dear TMNT Fandom,

I am a panromantic demisexual demigirl in my forties who 1) didn't even know those terms until recently, calling myself a bisexual who didn't want casual sex for a decade, and 2) found some memories from the late 90s of conversations with folks with ties to Mirage Studios, and I need to say this:

I cannot believe we as a fandom have to explain that the Ninja Turtles, fantasy creatures, can be headcanoned as Asexual not just because it is a real thing and not weird like some are saying, but because specifically the original Mirage Turtles were asexual, not attracted to humans, and as the series went on and they grew up, more concerned with their own unique bond as the only members of their kind over romantic relationships.

For example: Mike's fling with the Styracodon princess Seri was a manipulation, and Future Leonardo being with Raven Shadowheart was a choice. They're still asexual, even maybe gray or demi. We never got to know if Seri's eggs were Mikey's but we know he didn't have feelings for her.

In all the cartoon versions, we see various relationships happen which reflect some of the era and audience. Great example is 2012.

Actually, since Peter hated romance and Kevin was the one to sign off on the Next Mutation which was the straw that broke the camel's back for their split, we know Kevin is supportive of a lot of headcanons, even the actually weird ones, and thanks to my brain suddenly yelping "holy shell I remember that" I know how a lot of TMNT franchise crew members support inclusive headcanons even if they might not be canon. So someone saying "why are fan writers and artists making the turtles ace [or trans or NB], I think it's so weird" is absolutely one of the more bizarre things to come from the fandom. Because... they're turtles. They're mutants. Hell, to get super technical they're essentially genetically aliens, since the mutagen was created by aliens and fused with their DNA. They have more turtle in them than human. They're not human, the actual entire point of the characters, so the other entire point is how they learn to become psychologically and socially human, which rules to follow, which morals to have that don't need to be human. Thus, it extends to fans who create Alternate Universes and Canon Divergent worlds. And asexuality, the ace spectrum, is a real world thing that has always existed even if we didn't always know the words. To try to insist that these not-real fantasy creatures - ones that don't exist, have no bearing on real life except our imaginations, and should't be so restricted - cannot represent orientations and identities for fans who share with fans is, at the very least, disingenuous, controlling, upsetting, and exasperating.

I didn't spend nearly thirty years fighting oppression as both LGBTQIA and disabled to see my my favorite fandom pushed against by aphobia, transphobia, and bullying in general.

Although, really, I am a fool, I should have seen all this. I know Tumblr is completely different than other platforms, completely different from my Olde Fann favorites like Livejournal and the old Geocities forums, and online social communities are now faster than, say, my ADHD thoughts in a hyperfocus, but I still want to be Old Man Yells At Cloud and Get Off My Lawn You Kids when it comes to this very specific fandom thing and I totally see how weird that is on its face. I've been studying neuropsychology a lot, I usually notice my own weirds and faults more than usual.

Anyway. Aaanyway. Uh. So. *exhales*

Haa, panic attacks are the worst, aren't they? Also, I gotta stop believing the depression and anxiety monsters in my head, they take up too much real estate and I'm tired and getting too old for this weird AAAAAA-ness.

(One of my inner voices is like, "Woman, you are talking about ninja mutant turtle creatures that were created as a parody of gritty superheroes, who are you calling weird and AAAA?" and all I can do is shrug with a "you got me smile" and a long sigh. But I try, oh my god do I try, all the time, in this institution - *pause to break into song I said hey hey hey* - and I keep learning from my fictional sunshine child as I go so I can keep up with all the So Which Of My Identities Is Being Threatened In Society This Time discourse and especially the memes. All the memes.

I am a cautious optimist, after all. Nihilistic Optimist maybe? All I know is my entire life is multiple piles of junk cluttering a small room and everything is shiny even when it's hidden in shadows. Just smile until it feels better.

#tmnt#tmnt fandom#tmnt history#fandom history#i love this fandom#fandom grandma#fandom#tmnt fanfiction#tmnt headcanons#i have too many headcanons#tmnt is my autistic special interest#the neuropsychology of michelangelo#thesis#i created this tumblr because of michelangelo#i've been in fandom for decades and bullying is worse now#this is why fandom bullying today confuses me#being queer#pandemisexual#polyamorous mikey#let people have their headcanons#social anxiety#autistic anxiety#adhd rsd#give mikey caffeine for his adhd#give rebel leo a chance#mikey has a dimension x psionic brain#rottmnt#untitled rottmnt fanfic#the creators love the fans#hi i'm weird

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

AW was never diagnosed and never wanted a diagnosis. Their dumb asses never were EVEN pathologized to begin with when DID was misrepresented often as a spiritual phenomenon or LITERAL FANTASY MAKE-BELIEVE, they very blatantly hated – and still hate! – psychiatry and want it dead in the water, simple as. Just like scaryarcade and other grifters they pretend to be against "an institution" but the moment you give them any form of bait– they'll reveal how staunchly anti-science (and yes, they wanted the ENTIRE FIELD OF RESEARCH GONE) they are. Just go scrolling through AW today where they claim medicating kids for anything is abuse, which you clearly haven't despite totally being here since before the dinosaurs, we get it, you're a fossil. Endos existed before empowered multiples, you don't need to subscribe to the ableists to prove your validity

I thought the community's interpretation of the label doesn't matter? We don't trust anti-endos when they say they're not the same anti-endos from the 90s, why should we trust the endos who say they're not the same endos from the 90s? Oh right, because endos are an oppressed race and anti-endos are slaver nazis, totally, thanks, i missed the memo. Anyway, peace offering not accepted, because your community loves pretending empowered multiples never happened or was just "questionable takes" and "weird opinions". You don't let your racist uncle come to the barbecue because "he just has questionable takes", and since you insist on doing it, we're no longer letting you come to the barbecue.

yes, it is eugenics to want to remove the diagnosis and eventually ban psychiatry – the field of studying mental illnesses – altogether, which was AW's goal to anyone who doesn't have the mental capacity of a large slab of foam. "Societal assistance and programs will help you!" Doesn't fucking work for DID systems who are formed by these """"""support systems"""""" being fucking dogshit to the point of severe repeated trauma. Guess what, medication RELIES on pathology to even exist, numbnuts, otherwise how will you even tell what's a negative effect and what isn't? When even doctors make so many fucking prescription errors it's a literal cliche among us pharmacists, asking us to trust you uneducated laymen is fucking hilarious. We should just be giving lithium to people haphazardly! Quick, get this guy some hydralazine for the dissociation– sorry i mean Very Normal State of Mind Indistinguishable from Other States of Mind!

Some people. As in not all. As in we shouldn't remove the diagnosis from the fucking DSM because there are still people who need it. You really just followed them blindly and don't wanna admit it, huh? It's okay if you were 10 yourself and really were wowed by the big strong mysterious geocities site run by the larping anarchists weaponizing abuse responses as praxis. They did want to remove the fucking diagnosis, and no amount of "well a doctor was awful to me" excuses wanting to destroy an entire support system and drag everyone screaming with you to the pits of unregulated philanthropy-run psych wards, where more children get tortured and killed on the daily than any hospital. shitty doctor? Get them FUCKING FIRED instead of attacking the vulnerable because you can't get your hands on the head honcho. Subjecting the innocent to trauma responses isn't vigilante justice, it's just abusive.

Maybe you shouldn't have been "fighting" with your eyes closed and head wedged firmly up your ass.

"Read and learn" hey bud? Yeah so I was/am friends with several people who were in the community thirty years ago, I've read their blog posts from the Era, and while it is not free of ableism I need you to understand that

1. MPD pathologized ALL plurality/multiplicity. All of it. The fact that some systems didn't wish to be pathologized is not ableism. Again, I can tell you about the ableism; it was definitely there.

2. I was there several years before the -genic labels were created, the term endogenic was meant to be a peace offering to the DID community who took offense at the old terms.

3. Eugenicist?????? Huh?????? Even given the most uncharitable interpretation of EM's intentions how the fuck is it eugenicist? Do you know what that means??????

4. Abuse at the hands of psychiatrists was a real thing, especially in the 90s, when every therapist and psychologist and their mother wanted to get a fucking book deal and exploit trauma survivors for money. Given the history of sensationalizing and selling of the narrative of MPD in the past, I can understand why certain people rejected their diagnoses--especially if every single case of multiplicty/plurality was seen as inherently mentally ill, and the patients had other ideas and wanted to define themselves.

5. Dude. Of course I have already seen this shit. I've been fighting in these fucking trenches for 12 years.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

My Personal Cyber Infrastructure

I coded my first website in 1999, two years after I got connected to the internet using FrontPage Express and uploading the files to Geocities. I learned HTML by studying the code generated by FrontPage and comparing it to a laminated reference guide that I still have.

I never uploaded anything interesting until one day a teacher recommended we posted the reports he assigned online and introduced my classmates and me to the Industry of Knowledge ran by a fellow teacher Fernando Galindo Soria, who we called "Doc" and had a project of having millions of websites with useful information.

Because of that I got involved in teaching others how to make websites using free tools like the aforementioned FrontPage Express or Netscape Composer. Although Doc tried to secure us a folder within the schools server, he wasn't able to do so and we ended up uploading the websites to free servers.

He recommended we had our own personal cyber infrastructure. He told us to buy a domain name and find some cheap hosting that gave us ftp access, a database and full control over our server. It wasn't until I started charging for making websites a few years later that I got my own domain name and a shared server.

Never have I been able to secure a website space in any of the institutions I have worked for, even as a Teacher, so I have my personal cyber infrastructure implemented and buy domain names when I need them and cancel them when I don't.

0 notes

Text

<< Ankerson, the web-history researcher, said that some platforms are better than others at maintaining archives, but the best hope for holding on to the internet is people. Amateurs, fans, or anybody who has “a passion to save something”—as was the case with the people who saved most of Geocities, or those organizing the current effort to document the pandemic year of Animal Crossing: New Horizons—will save much more than any institution will. I’ve noticed this myself, while doing research for a book about One Direction fans and the complicated arguments they had with one another on Tumblr in 2011 and 2012, before the site had an in-house data scientist or really any understanding of what was happening on its own platform. Many old posts no longer exist, or they’re preserved on the Wayback Machine but covered in blank patches where images and GIFs did not survive. Typically, I had my best luck interviewing people who remembered specific conversations or memes that were important to them—or just odd enough to leave an impression. >>

0 notes

Text

Podcast: Psych Central Turns 25 This Year

It’s Psych Central’s 25th anniversary! In today’s show, we celebrate the Internet’s largest and oldest independent mental health site with founder Dr. John Grohol. Just a few years after the World Wide Web became public domain, Dr. Grohol was inspired to create an online resource for everyone — a site where patients, clinicians and caregivers could come together to access and share valuable mental health and psychology information.

Join us as Gabe and Dr. Grohol talk about the past, present and future of Psych Central.

SUBSCRIBE & REVIEW

Guest information for ‘John Grohol-Psych central’ Podcast Episode

John M. Grohol, Psy.D. is a pioneer in online mental health and psychology. Recognizing the educational and social potential of the Internet in 1995, Dr. Grohol has transformed the way people could access mental health and psychology resources online. Pre-dating the National Institute for Mental Health and mental health advocacy organizations, Dr. Grohol was the first to publish the diagnostic criteria for common mental disorders, such as depression, bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. His leadership has helped to break down the barriers of stigma often associated with mental health concerns, bringing trusted resources and support communities to the Internet.

He has worked tirelessly as a patient advocate to improve the quality of information available for mental health patients, highlighting quality mental health resources, and building safe, private support communities and social networks in numerous health topics.

About The Psych Central Podcast Host

Gabe Howard is an award-winning writer and speaker who lives with bipolar disorder. He is the author of the popular book, Mental Illness is an Asshole and other Observations, available from Amazon; signed copies are also available directly from the author. To learn more about Gabe, please visit his website, gabehoward.com.

Computer Generated Transcript for ‘John Grohol-Psych Central’ Episode

Editor’s Note: Please be mindful that this transcript has been computer generated and therefore may contain inaccuracies and grammar errors. Thank you.

Announcer: You’re listening to the Psych Central Podcast, where guest experts in the field of psychology and mental health share thought-provoking information using plain, everyday language. Here’s your host, Gabe Howard.

Gabe Howard: Hello, everyone, and welcome to this week’s episode of The Psych Central Podcast. Calling into the show today, we have Dr. John Grohol. Dr. Grohol is the editor in chief of PsychCentral.com and the man who founded Psych Central 25 years ago. John, welcome to the show.

Dr. John Grohol: Great to be with you today, Gabe. It’s an exciting achievement.

Gabe Howard: I’ve never done anything for 25 years. It’s incredibly impressive. And I want to start back twenty six years ago, twenty seven years ago before Psych Central existed. When you were coming up with the idea for this Web site, how did you get this idea?

Dr. John Grohol: So it all began when I was in grad school down in Florida and I had a bad first year in school because I learned about the death of my childhood best friend who took his own life. And that was a difficult thing to come to terms with because none of us saw the situation at the time that he was going through and he didn’t feel comfortable in reaching out to anyone. This was back in 1990 and I needed help, but I didn’t exactly know where to turn. One of the places I ended up turning to was a support group online, and that support group was on a section of the Internet we call Usenet, which hosts newsgroups. We call them newsgroups, they are actually just what we would today call like a discussion forum like Reddit or something or even Facebook, similar in the sense of these were groups set up to discuss specific topics. One of those topics was a depression group. And I just found it astounding, amazing that there was an online support group for depression in 1990.

Gabe Howard: And this is before the Internet was a household name.

Dr. John Grohol: Yeah, this, well, this predates the Web, and that’s why it’s hard to explain and hard to have people wrap their minds around it, because here we are 30 years later and to understand that people were doing online support, emotional support and information sharing thirty years ago. So these are not new phenomenon. So for people to sort of look at the Internet and say, oh, you know, it’s not real or you can’t have a real emotional connection with other people, I laugh at them because we’ve been, people have been having real emotional connections through Internet technologies for well over 30 years, actually goes back even further than that.

Gabe Howard: Yeah, I remember the old, like, bulletin board system days.

Dr. John Grohol: Yeah, yeah, absolutely. CompuServe, AOL and Prodigy too were the commercial services and they also had the equivalent of support groups in their respective services.

Gabe Howard: They did. I used to work for CompuServe serve, and that’s where I found the Internet. So it’s interesting. We’ve got a similar story so far with technology really helping us get through difficult times. And of course, I’m really sorry about the loss of your friend.

Dr. John Grohol: Thank you. It was a really difficult time in my life, and using that support group really helped me and it really helped me understand the power that such support groups held for people, if only they knew about them. The fact that I came upon it, it was only because I had some mad computer skills at the time. Computers were a hobby of mine. So I understood how to search for that type of group on Usenet. At the time, it was not a simple process and you had to be in academia. Back then, you had to be associated with the university as a student or a professor or something even to access that part of the Internet. So that got me thinking, well, if this helped me so much, and it’s helping other people as much as I can see that it is, wouldn’t it be great if more people knew about this? So I started collecting, I started indexing all these support groups that existed back in 1990 and 1991. And I published those indexes on those groups to let people know about other great emotional support and psychology groups that existed so people could find them and find each other.

Gabe Howard: And this was all before PsychCentral.com was a registered domain name.

Dr. John Grohol: Yep, yep.

Gabe Howard: And now here we are. So it’s obviously you did this for five years, which is not an insignificant amount of time. This wasn’t a whim for you. This was something that was a major part of your life for half a decade.

Dr. John Grohol: I was actually deeply involved in newsgroups back then because that was the modality that people used to have online discussions. There was no Reddit. There was no other way of doing that. Well, that’s not entirely true. There’s a thing called mailing lists that still exists today, too. And that’s where you get the online discussion, it comes right to your email box. And those remain widely used in many parts of the Internet.

Gabe Howard: So now we’re at 1995. Twenty five years ago.

Dr. John Grohol: So 1995, it looked like the Web was going to be the phenomena that turned out to be, and I said, well, this is a good place to publish a Web site and to put these indexes, to give them a home. To point people to a Web site and say, here you can go and find an online support group here. You can go and find a group about psychology or some related topic. And it’s so much easier than trying to publish these on newsgroups. So the first couple of years, there was no PsychCentral.com domain because domains back then were also pretty expensive. So what most people did is that they would use an Internet service provider’s domain and they would have lots of users, much like, if you remember, early Web sites allowed people to build their own Web site like GeoCities

Gabe Howard: Like GeoCities

Dr. John Grohol: So, yes, that’s the one. So you had your Web site and it hung off the GeoCities.com domain. That’s where Psych Central originally lived at first in upstate New York, where I did my internship. Eventually, I went out and spent the, I think it was like $50 or $60 a year to have a dot.com domain back then. So that’s a pretty significant investment. So I had to make sure that I was ready to make that commitment to PsychCentral.com. And it was perfectly OK before like 2002 to not like have your own domain. That was more of a corporate thing.

Gabe Howard: So here we are, we’ve now registered PsychCentral.com. What did this site look like when you made the leap from, you know, hanging off somebody else’s domain name? What sort of took place in these transitional years, these startup years?

Dr. John Grohol: Well, at first, it was more of a hobby site for me. I mean, it literally was a way of publishing these indexes and learning HTML and coding for the Internet and doing that and understanding how graphics worked and how. You had to do it all back then. There was no such career as a web developer. HTML was built to be simple and easily learned. And so anybody could create their own Web site. I taught many conference workshops about how a clinician, how therapists could build their own Web site, because it was that easy. And you can still do it today. You can build a very simple Web site using raw HTML coding directly from an application like notepad or word pad or something like that. So for the first couple of years, the Web site didn’t have a lot. It was maybe like a dozen pages and a bunch of those pages were the indexes of the support groups.

Gabe Howard: To put it in 2020 talk, it was basically just a list of links.

Dr. John Grohol: Yes, it was a list of links, because that’s. It’s hard to understand this, but Yahoo at the time in 1995 was the only search directory and Yahoo was just a list of links curated by human editors. And that’s what made it special. But back in 95, 96, 97, the Web was small enough that you could actually have humans go around looking for new Web sites to put into their directory. And so that’s basically what I was doing. I was doing a specialized directory of links for mental health, for psychology.

Gabe Howard: Did that have a blog on it? Were you writing articles back then? Or is this?

Dr. John Grohol: So that’s a good question about blogging, because I did start blogging and I believe it was 1999. And I wasn’t satisfied with any of the blogging software available at the time because it was all pretty rudimentary and didn’t quite do everything that I wanted it to do. And so I coded my own blog software to be become a blogger, and I coded that in Perl. And I maintained it for a couple of years until WordPress came around. And that was in the early 2000s.

Gabe Howard: When did PsychCentral.com start looking how it looks today? And I don’t mean design wise, I mean, you know, having all of the blogs, having the forums, having the news and all of the stuff that people have come to rely on today.

Dr. John Grohol: From 1995 to 2006, those first eleven years it grew bit by bit, piece by piece. I worked on it in my spare time. It was not my full time gig. I had other jobs working for other companies, helping them build mental health Web sites. I added pages here and there where I could, when I could, when I had the time. And it was kind of done, you know, randomly, haphazardly. I didn’t really have a clear vision for what I wanted it to be and become because I was doing this work for other companies. But I did see it that it had a good traffic profile, that it still continued to get a lot of traffic, despite it not being as big as some other Web sites out there or as in depth about different mental health issues. I also encouraged a lot of people to publish on the site if they had an article or if they wanted to tell their personal story about dealing with mental health issues or dealing with treatment and whatnot. So I published a lot of other people’s stories, other people’s writing on the site as well. In 2006, that’s when I decided I had enough of working for the man and different start ups and seeing all the ways that they were doing things wrong and spending money on things that didn’t matter. And I was so sick of seeing that. I was seeing, you know, millions of dollars just basically be wasted and poured down the drain. And so in 2006, I said, look, I can do this better. I can do this more thoughtfully. And I can do this independent of any industry influence, whether it be pharma, whether it be my own biases toward psychotherapy. I believe we can create a better mental health Web site that has information that we keep updated, that we add new stuff to, that we have a blog. 2006 was really the tipping point, the turning point for Psych Central, because I started focusing on it full time. It started paying my bills and it allowed me to hire my first couple of staffers.

Gabe Howard: We’ll be right back after we hear from our sponsors.

Sponsor Message: This episode is sponsored by BetterHelp.com. Secure, convenient, and affordable online counseling. Our counselors are licensed, accredited professionals. Anything you share is confidential. Schedule secure video or phone sessions, plus chat and text with your therapist whenever you feel it’s needed. A month of online therapy often costs less than a single traditional face to face session. Go to BetterHelp.com/PsychCentral and experience seven days of free therapy to see if online counseling is right for you. BetterHelp.com/PsychCentral.

Gabe Howard: We’re back discussing the 25th anniversary of PsychCentral.com with founder Dr. John Grohol. Now, I know that Psych Central’s credo is to provide the best evidence based mental health and psychology information, regardless of profession. All voices are important and should be elevated in the discourse about mental illness and mental health. When did that credo come along?

Dr. John Grohol: The background for the credo comes from my seeing back in my graduate school days, my observing that the professions didn’t talk to each other. Psychiatrist didn’t talk to psychologists. Clinical social workers didn’t talk to a psychiatrists or psychologists. That each of these were their own individual silos in training and then in practice, in research and then trying to get those research results disseminated to clinicians. And there was no reason for it. We’re all trying to work on the same disorders. And I found it so frustrating because at the end of the day, all the mental health professionals and there’s, you know, five, six, seven, eight, nine different types of mental health professionals, they’re all doing the same kinds of things. They’re trying to help people grapple with difficult things in their lives, whether they be diagnosed mental illness or personality concerns or just coping with a life issue. And I saw no reason for this disconnect between the professions. It really annoyed me. And I talked to other colleagues and found, surprisingly, that they were open to the idea. That there is this desire to coordinate and communicate more between professions, but it just doesn’t happen. So from the onset of building Psych Central, I very strongly believed that we should be agnostic in our development and in our communications, the way we write content, the topics we focus on. We should try and be as objective as possible, as independent as possible.

Dr. John Grohol: And really just look at what does the research say? Does the research say therapy works best for this disorder? Or does the research say medications work best? Or some combination of the two? Or is there a third modality that you should consider? And I just put aside any professional biases as much as humanly possible and tried to create the content that reflects that belief in the credo. The last part of the credo is that it’s not a conversation just for professionals to be having among themselves. The most important part of the conversation is patients, our clients, and they need to be a part of the conversation. Their stories need to be heard. And from day one, I always believed that. And I try and I tried to create a platform where patient stories could also be a part of the conversation. And in my view, the most important part.

Gabe Howard: John, it’s interesting, I was diagnosed with bipolar disorder back in 2003, and it was 2006, 2007 before I would say that I started to become a mental health advocate. And for years, I sort of bopped around in the siloed system that you speak of. I was a person with lived experience or I was a consumer, a peer, a patient. And when I met up with websites that wanted to talk about, you know, the research and the facts, they had no interest in my voice because they believed that my voice was opinion. And then I met up with you. And that was fantastic because you understood that the patient voice is relevant and the clinician voice is relevant and the caregiver voice is relevant and PsychCentral.com really has all of these voices coexisting in perfect harmony. So it’s no surprise that somebody like me ended up on Psych Central, because my only other choice would really to be on just a patient only Web site. And I, like you, feel that just leaves so much information out. And it also sort of makes us hostile to each other. Do you find that everybody coexists well, on PsychCentral.com?

Dr. John Grohol: You know, that’s the goal, that that is what we strive to be, what we strive for the site to reflect, that all of these voices are equal. I don’t know that, you know, we always are successful at doing that as well as we could, but we do try. And it is rooted firmly in the belief that the patient voice isn’t just one of many. I would argue it’s the most important. It’s the one that’s least heard and is often left out of the conversation altogether. And I find that just horrible, horrible bias in a lot of Web sites out there that they don’t include the patient voice or it’s sectioned off into its own special patient section. You know, here are the patient stories. I don’t believe in that. I believe that it should be as integral and as well integrated into the conversation as much as any other voice, because we’re talking about patient lives here. They need to be a part of the solution. They need to be a part of, an active part of their treatment, or in many cases, the treatment simply isn’t that effective.

Gabe Howard: Well, John, obviously you’re going to get no argument from me. I do want to commend you strongly for doing this, because I think that people who don’t live with mental illness don’t realize how often the patient voice is pushed down. So I was very surprised when I found Psych Central just as a user. It came up in a Google search. And I liked this because it forced me to learn about all sides. And I think that made me not only a better mental health advocate, but honestly, I think it allowed me to get better care. And I know that is a common thing that I hear running the podcast and doing the work that I do. So, of course, complete kudos to you.

Dr. John Grohol: Thank you. Thank you. But it’s not me. I have a hard time accepting such things because I do the platform and I do what we’ve created here with the help and support and standing on the shoulders of dozens of staffers like yourself. It wouldn’t be possible to have the great resources that we have on Psych Central without people like you, without people like our managing editor Sarah Newman, without all the other great editors and contributors that we have. It’s just they are all individually amazing people and they’ve helped, you know, make Psych Central what it is today. And of course, it would be nothing today if we weren’t able to actually speak to people in a way that they find useful. Because we have somewhere between six and seven million unique users every month. That also helps us do the kind of work that we’re trying to do.

Gabe Howard: John, we’ve talked about the past, we’ve talked about the present. What’s the future of Psych Central?

Dr. John Grohol: The future of Psych Central is always a question in my mind, because we’ve had a great 14 years as a full time ongoing concern. The online landscape over the past four or five years has definitely gotten a lot more difficult to navigate with Google and primarily Google, because that’s the search engine that everybody uses and their algorithm changes. A small digital publisher like Psych Central has a much more challenging time navigating these kinds of algorithm changes that don’t seem to make very much sense to us or to a lot of other health publishers. That’s definitely been a challenge for us. So in the future, I’d like to hope that Google continues to listen to small publishers like us and is aware that when they change the algorithm, and it can really hurt publishers that have been providing health information before they were even, before they were even a business, before they were even a company. I mean, we’ve been around before WebMD. We’ve been around long before Google. Part of the future of Psych Central is trying to maintain our leadership position as an independent mental health resource.

Dr. John Grohol: I think some of the ways that we can improve and do some awesome things in the space is, for instance, to put together a great app. We’ve done an app in the past, but it was more just a way of interacting with our Web site. And we’d like to do an app that is more intervention based and helps people wherever they are in their own mental health journey to try and become a better person, to try and cope better with those kinds of things that life is throwing at them, whether they’re mental health issues or relationship issues. And I see a lot of potential there. So that’s something that we’re looking to get started with this year and hopefully have something out within a year’s time or so. The future is, Tom Petty reminds us, is wide open. And I believe that we have still only touched the tip of the iceberg in terms of what’s possible to help people with mental health issues and concerns in their own daily lives.

Gabe Howard: Well, John, I can’t thank you enough for starting Psych Central, and I can’t thank you enough for being open to evolving. It wasn’t three years ago, actually on November 19, 2017, we aired the very first episode of The Psych Central Podcast where we had you as a guest telling us all about Psych Central. And I listen to that episode sometimes and it really just reminds me of how far we have come with the podcast in the last three years. And of course, thank you for being willing to invest in podcasting at a time when, well, frankly, most people were rolling their eyes and saying, everybody has a podcast.

Dr. John Grohol: Yeah, I mean, it’s just one of those things that we like to innovate. We like to see what kind of platforms, what kind of things people are interested in doing and trying to reach them wherever they are. I think that’s so important. If they’re into podcasting, why wouldn’t you have a platform? Why wouldn’t you have some podcasts to try and help people understand mental health better? Psychology better?

Gabe Howard: Well, I guarantee that every listener of this show could not agree with you more, John. This was great. You want to come back in say five years for the 30th anniversary of PsychCentral.com?

Dr. John Grohol: Gabe, I think that would be a great thing to look forward to, and I’m going to put it on my calendar.

Gabe Howard: Well, John, I agree, and it’s a date. All right, everybody, here’s what we need you to do. If you like the show, please subscribe. Please rank us. Review us. Use your words and tell people why you like us. Share us on social media. Send us in e-mails, mention us in support groups. If you’re at dinner with your mother and you’re bored, tell her all about The Psych Central Podcast. And remember, you can get one week of free, convenient, affordable, private online counseling anytime, anywhere, simply by visiting BetterHelp.com/PsychCentral. And we will see everybody next week.

Announcer: You’ve been listening to The Psych Central Podcast. Want your audience to be wowed at your next event? Feature an appearance and LIVE RECORDING of the Psych Central Podcast right from your stage! For more details, or to book an event, please email us at [email protected]. Previous episodes can be found at PsychCentral.com/Show or on your favorite podcast player. Psych Central is the internet’s oldest and largest independent mental health website run by mental health professionals. Overseen by Dr. John Grohol, Psych Central offers trusted resources and quizzes to help answer your questions about mental health, personality, psychotherapy, and more. Please visit us today at PsychCentral.com. To learn more about our host, Gabe Howard, please visit his website at gabehoward.com. Thank you for listening and please share with your friends, family, and followers.

Podcast: Psych Central Turns 25 This Year syndicated from

0 notes

Text

Podcast: Psych Central Turns 25 This Year

It’s Psych Central’s 25th anniversary! In today’s show, we celebrate the Internet’s largest and oldest independent mental health site with founder Dr. John Grohol. Just a few years after the World Wide Web became public domain, Dr. Grohol was inspired to create an online resource for everyone — a site where patients, clinicians and caregivers could come together to access and share valuable mental health and psychology information.

Join us as Gabe and Dr. Grohol talk about the past, present and future of Psych Central.

SUBSCRIBE & REVIEW

Guest information for ‘John Grohol-Psych central’ Podcast Episode

John M. Grohol, Psy.D. is a pioneer in online mental health and psychology. Recognizing the educational and social potential of the Internet in 1995, Dr. Grohol has transformed the way people could access mental health and psychology resources online. Pre-dating the National Institute for Mental Health and mental health advocacy organizations, Dr. Grohol was the first to publish the diagnostic criteria for common mental disorders, such as depression, bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. His leadership has helped to break down the barriers of stigma often associated with mental health concerns, bringing trusted resources and support communities to the Internet.

He has worked tirelessly as a patient advocate to improve the quality of information available for mental health patients, highlighting quality mental health resources, and building safe, private support communities and social networks in numerous health topics.

About The Psych Central Podcast Host

Gabe Howard is an award-winning writer and speaker who lives with bipolar disorder. He is the author of the popular book, Mental Illness is an Asshole and other Observations, available from Amazon; signed copies are also available directly from the author. To learn more about Gabe, please visit his website, gabehoward.com.

Computer Generated Transcript for ‘John Grohol-Psych Central’ Episode

Editor’s Note: Please be mindful that this transcript has been computer generated and therefore may contain inaccuracies and grammar errors. Thank you.

Announcer: You’re listening to the Psych Central Podcast, where guest experts in the field of psychology and mental health share thought-provoking information using plain, everyday language. Here’s your host, Gabe Howard.

Gabe Howard: Hello, everyone, and welcome to this week’s episode of The Psych Central Podcast. Calling into the show today, we have Dr. John Grohol. Dr. Grohol is the editor in chief of PsychCentral.com and the man who founded Psych Central 25 years ago. John, welcome to the show.

Dr. John Grohol: Great to be with you today, Gabe. It’s an exciting achievement.

Gabe Howard: I’ve never done anything for 25 years. It’s incredibly impressive. And I want to start back twenty six years ago, twenty seven years ago before Psych Central existed. When you were coming up with the idea for this Web site, how did you get this idea?

Dr. John Grohol: So it all began when I was in grad school down in Florida and I had a bad first year in school because I learned about the death of my childhood best friend who took his own life. And that was a difficult thing to come to terms with because none of us saw the situation at the time that he was going through and he didn’t feel comfortable in reaching out to anyone. This was back in 1990 and I needed help, but I didn’t exactly know where to turn. One of the places I ended up turning to was a support group online, and that support group was on a section of the Internet we call Usenet, which hosts newsgroups. We call them newsgroups, they are actually just what we would today call like a discussion forum like Reddit or something or even Facebook, similar in the sense of these were groups set up to discuss specific topics. One of those topics was a depression group. And I just found it astounding, amazing that there was an online support group for depression in 1990.

Gabe Howard: And this is before the Internet was a household name.

Dr. John Grohol: Yeah, this, well, this predates the Web, and that’s why it’s hard to explain and hard to have people wrap their minds around it, because here we are 30 years later and to understand that people were doing online support, emotional support and information sharing thirty years ago. So these are not new phenomenon. So for people to sort of look at the Internet and say, oh, you know, it’s not real or you can’t have a real emotional connection with other people, I laugh at them because we’ve been, people have been having real emotional connections through Internet technologies for well over 30 years, actually goes back even further than that.

Gabe Howard: Yeah, I remember the old, like, bulletin board system days.

Dr. John Grohol: Yeah, yeah, absolutely. CompuServe, AOL and Prodigy too were the commercial services and they also had the equivalent of support groups in their respective services.

Gabe Howard: They did. I used to work for CompuServe serve, and that’s where I found the Internet. So it’s interesting. We’ve got a similar story so far with technology really helping us get through difficult times. And of course, I’m really sorry about the loss of your friend.

Dr. John Grohol: Thank you. It was a really difficult time in my life, and using that support group really helped me and it really helped me understand the power that such support groups held for people, if only they knew about them. The fact that I came upon it, it was only because I had some mad computer skills at the time. Computers were a hobby of mine. So I understood how to search for that type of group on Usenet. At the time, it was not a simple process and you had to be in academia. Back then, you had to be associated with the university as a student or a professor or something even to access that part of the Internet. So that got me thinking, well, if this helped me so much, and it’s helping other people as much as I can see that it is, wouldn’t it be great if more people knew about this? So I started collecting, I started indexing all these support groups that existed back in 1990 and 1991. And I published those indexes on those groups to let people know about other great emotional support and psychology groups that existed so people could find them and find each other.

Gabe Howard: And this was all before PsychCentral.com was a registered domain name.

Dr. John Grohol: Yep, yep.

Gabe Howard: And now here we are. So it’s obviously you did this for five years, which is not an insignificant amount of time. This wasn’t a whim for you. This was something that was a major part of your life for half a decade.

Dr. John Grohol: I was actually deeply involved in newsgroups back then because that was the modality that people used to have online discussions. There was no Reddit. There was no other way of doing that. Well, that’s not entirely true. There’s a thing called mailing lists that still exists today, too. And that’s where you get the online discussion, it comes right to your email box. And those remain widely used in many parts of the Internet.

Gabe Howard: So now we’re at 1995. Twenty five years ago.

Dr. John Grohol: So 1995, it looked like the Web was going to be the phenomena that turned out to be, and I said, well, this is a good place to publish a Web site and to put these indexes, to give them a home. To point people to a Web site and say, here you can go and find an online support group here. You can go and find a group about psychology or some related topic. And it’s so much easier than trying to publish these on newsgroups. So the first couple of years, there was no PsychCentral.com domain because domains back then were also pretty expensive. So what most people did is that they would use an Internet service provider’s domain and they would have lots of users, much like, if you remember, early Web sites allowed people to build their own Web site like GeoCities

Gabe Howard: Like GeoCities

Dr. John Grohol: So, yes, that’s the one. So you had your Web site and it hung off the GeoCities.com domain. That’s where Psych Central originally lived at first in upstate New York, where I did my internship. Eventually, I went out and spent the, I think it was like $50 or $60 a year to have a dot.com domain back then. So that’s a pretty significant investment. So I had to make sure that I was ready to make that commitment to PsychCentral.com. And it was perfectly OK before like 2002 to not like have your own domain. That was more of a corporate thing.

Gabe Howard: So here we are, we’ve now registered PsychCentral.com. What did this site look like when you made the leap from, you know, hanging off somebody else’s domain name? What sort of took place in these transitional years, these startup years?

Dr. John Grohol: Well, at first, it was more of a hobby site for me. I mean, it literally was a way of publishing these indexes and learning HTML and coding for the Internet and doing that and understanding how graphics worked and how. You had to do it all back then. There was no such career as a web developer. HTML was built to be simple and easily learned. And so anybody could create their own Web site. I taught many conference workshops about how a clinician, how therapists could build their own Web site, because it was that easy. And you can still do it today. You can build a very simple Web site using raw HTML coding directly from an application like notepad or word pad or something like that. So for the first couple of years, the Web site didn’t have a lot. It was maybe like a dozen pages and a bunch of those pages were the indexes of the support groups.

Gabe Howard: To put it in 2020 talk, it was basically just a list of links.

Dr. John Grohol: Yes, it was a list of links, because that’s. It’s hard to understand this, but Yahoo at the time in 1995 was the only search directory and Yahoo was just a list of links curated by human editors. And that’s what made it special. But back in 95, 96, 97, the Web was small enough that you could actually have humans go around looking for new Web sites to put into their directory. And so that’s basically what I was doing. I was doing a specialized directory of links for mental health, for psychology.

Gabe Howard: Did that have a blog on it? Were you writing articles back then? Or is this?

Dr. John Grohol: So that’s a good question about blogging, because I did start blogging and I believe it was 1999. And I wasn’t satisfied with any of the blogging software available at the time because it was all pretty rudimentary and didn’t quite do everything that I wanted it to do. And so I coded my own blog software to be become a blogger, and I coded that in Perl. And I maintained it for a couple of years until WordPress came around. And that was in the early 2000s.

Gabe Howard: When did PsychCentral.com start looking how it looks today? And I don’t mean design wise, I mean, you know, having all of the blogs, having the forums, having the news and all of the stuff that people have come to rely on today.

Dr. John Grohol: From 1995 to 2006, those first eleven years it grew bit by bit, piece by piece. I worked on it in my spare time. It was not my full time gig. I had other jobs working for other companies, helping them build mental health Web sites. I added pages here and there where I could, when I could, when I had the time. And it was kind of done, you know, randomly, haphazardly. I didn’t really have a clear vision for what I wanted it to be and become because I was doing this work for other companies. But I did see it that it had a good traffic profile, that it still continued to get a lot of traffic, despite it not being as big as some other Web sites out there or as in depth about different mental health issues. I also encouraged a lot of people to publish on the site if they had an article or if they wanted to tell their personal story about dealing with mental health issues or dealing with treatment and whatnot. So I published a lot of other people’s stories, other people’s writing on the site as well. In 2006, that’s when I decided I had enough of working for the man and different start ups and seeing all the ways that they were doing things wrong and spending money on things that didn’t matter. And I was so sick of seeing that. I was seeing, you know, millions of dollars just basically be wasted and poured down the drain. And so in 2006, I said, look, I can do this better. I can do this more thoughtfully. And I can do this independent of any industry influence, whether it be pharma, whether it be my own biases toward psychotherapy. I believe we can create a better mental health Web site that has information that we keep updated, that we add new stuff to, that we have a blog. 2006 was really the tipping point, the turning point for Psych Central, because I started focusing on it full time. It started paying my bills and it allowed me to hire my first couple of staffers.

Gabe Howard: We’ll be right back after we hear from our sponsors.

Sponsor Message: This episode is sponsored by BetterHelp.com. Secure, convenient, and affordable online counseling. Our counselors are licensed, accredited professionals. Anything you share is confidential. Schedule secure video or phone sessions, plus chat and text with your therapist whenever you feel it’s needed. A month of online therapy often costs less than a single traditional face to face session. Go to BetterHelp.com/PsychCentral and experience seven days of free therapy to see if online counseling is right for you. BetterHelp.com/PsychCentral.

Gabe Howard: We’re back discussing the 25th anniversary of PsychCentral.com with founder Dr. John Grohol. Now, I know that Psych Central’s credo is to provide the best evidence based mental health and psychology information, regardless of profession. All voices are important and should be elevated in the discourse about mental illness and mental health. When did that credo come along?

Dr. John Grohol: The background for the credo comes from my seeing back in my graduate school days, my observing that the professions didn’t talk to each other. Psychiatrist didn’t talk to psychologists. Clinical social workers didn’t talk to a psychiatrists or psychologists. That each of these were their own individual silos in training and then in practice, in research and then trying to get those research results disseminated to clinicians. And there was no reason for it. We’re all trying to work on the same disorders. And I found it so frustrating because at the end of the day, all the mental health professionals and there’s, you know, five, six, seven, eight, nine different types of mental health professionals, they’re all doing the same kinds of things. They’re trying to help people grapple with difficult things in their lives, whether they be diagnosed mental illness or personality concerns or just coping with a life issue. And I saw no reason for this disconnect between the professions. It really annoyed me. And I talked to other colleagues and found, surprisingly, that they were open to the idea. That there is this desire to coordinate and communicate more between professions, but it just doesn’t happen. So from the onset of building Psych Central, I very strongly believed that we should be agnostic in our development and in our communications, the way we write content, the topics we focus on. We should try and be as objective as possible, as independent as possible.

Dr. John Grohol: And really just look at what does the research say? Does the research say therapy works best for this disorder? Or does the research say medications work best? Or some combination of the two? Or is there a third modality that you should consider? And I just put aside any professional biases as much as humanly possible and tried to create the content that reflects that belief in the credo. The last part of the credo is that it’s not a conversation just for professionals to be having among themselves. The most important part of the conversation is patients, our clients, and they need to be a part of the conversation. Their stories need to be heard. And from day one, I always believed that. And I try and I tried to create a platform where patient stories could also be a part of the conversation. And in my view, the most important part.

Gabe Howard: John, it’s interesting, I was diagnosed with bipolar disorder back in 2003, and it was 2006, 2007 before I would say that I started to become a mental health advocate. And for years, I sort of bopped around in the siloed system that you speak of. I was a person with lived experience or I was a consumer, a peer, a patient. And when I met up with websites that wanted to talk about, you know, the research and the facts, they had no interest in my voice because they believed that my voice was opinion. And then I met up with you. And that was fantastic because you understood that the patient voice is relevant and the clinician voice is relevant and the caregiver voice is relevant and PsychCentral.com really has all of these voices coexisting in perfect harmony. So it’s no surprise that somebody like me ended up on Psych Central, because my only other choice would really to be on just a patient only Web site. And I, like you, feel that just leaves so much information out. And it also sort of makes us hostile to each other. Do you find that everybody coexists well, on PsychCentral.com?

Dr. John Grohol: You know, that’s the goal, that that is what we strive to be, what we strive for the site to reflect, that all of these voices are equal. I don’t know that, you know, we always are successful at doing that as well as we could, but we do try. And it is rooted firmly in the belief that the patient voice isn’t just one of many. I would argue it’s the most important. It’s the one that’s least heard and is often left out of the conversation altogether. And I find that just horrible, horrible bias in a lot of Web sites out there that they don’t include the patient voice or it’s sectioned off into its own special patient section. You know, here are the patient stories. I don’t believe in that. I believe that it should be as integral and as well integrated into the conversation as much as any other voice, because we’re talking about patient lives here. They need to be a part of the solution. They need to be a part of, an active part of their treatment, or in many cases, the treatment simply isn’t that effective.

Gabe Howard: Well, John, obviously you’re going to get no argument from me. I do want to commend you strongly for doing this, because I think that people who don’t live with mental illness don’t realize how often the patient voice is pushed down. So I was very surprised when I found Psych Central just as a user. It came up in a Google search. And I liked this because it forced me to learn about all sides. And I think that made me not only a better mental health advocate, but honestly, I think it allowed me to get better care. And I know that is a common thing that I hear running the podcast and doing the work that I do. So, of course, complete kudos to you.

Dr. John Grohol: Thank you. Thank you. But it’s not me. I have a hard time accepting such things because I do the platform and I do what we’ve created here with the help and support and standing on the shoulders of dozens of staffers like yourself. It wouldn’t be possible to have the great resources that we have on Psych Central without people like you, without people like our managing editor Sarah Newman, without all the other great editors and contributors that we have. It’s just they are all individually amazing people and they’ve helped, you know, make Psych Central what it is today. And of course, it would be nothing today if we weren’t able to actually speak to people in a way that they find useful. Because we have somewhere between six and seven million unique users every month. That also helps us do the kind of work that we’re trying to do.

Gabe Howard: John, we’ve talked about the past, we’ve talked about the present. What’s the future of Psych Central?

Dr. John Grohol: The future of Psych Central is always a question in my mind, because we’ve had a great 14 years as a full time ongoing concern. The online landscape over the past four or five years has definitely gotten a lot more difficult to navigate with Google and primarily Google, because that’s the search engine that everybody uses and their algorithm changes. A small digital publisher like Psych Central has a much more challenging time navigating these kinds of algorithm changes that don’t seem to make very much sense to us or to a lot of other health publishers. That’s definitely been a challenge for us. So in the future, I’d like to hope that Google continues to listen to small publishers like us and is aware that when they change the algorithm, and it can really hurt publishers that have been providing health information before they were even, before they were even a business, before they were even a company. I mean, we’ve been around before WebMD. We’ve been around long before Google. Part of the future of Psych Central is trying to maintain our leadership position as an independent mental health resource.

Dr. John Grohol: I think some of the ways that we can improve and do some awesome things in the space is, for instance, to put together a great app. We’ve done an app in the past, but it was more just a way of interacting with our Web site. And we’d like to do an app that is more intervention based and helps people wherever they are in their own mental health journey to try and become a better person, to try and cope better with those kinds of things that life is throwing at them, whether they’re mental health issues or relationship issues. And I see a lot of potential there. So that’s something that we’re looking to get started with this year and hopefully have something out within a year’s time or so. The future is, Tom Petty reminds us, is wide open. And I believe that we have still only touched the tip of the iceberg in terms of what’s possible to help people with mental health issues and concerns in their own daily lives.

Gabe Howard: Well, John, I can’t thank you enough for starting Psych Central, and I can’t thank you enough for being open to evolving. It wasn’t three years ago, actually on November 19, 2017, we aired the very first episode of The Psych Central Podcast where we had you as a guest telling us all about Psych Central. And I listen to that episode sometimes and it really just reminds me of how far we have come with the podcast in the last three years. And of course, thank you for being willing to invest in podcasting at a time when, well, frankly, most people were rolling their eyes and saying, everybody has a podcast.

Dr. John Grohol: Yeah, I mean, it’s just one of those things that we like to innovate. We like to see what kind of platforms, what kind of things people are interested in doing and trying to reach them wherever they are. I think that’s so important. If they’re into podcasting, why wouldn’t you have a platform? Why wouldn’t you have some podcasts to try and help people understand mental health better? Psychology better?

Gabe Howard: Well, I guarantee that every listener of this show could not agree with you more, John. This was great. You want to come back in say five years for the 30th anniversary of PsychCentral.com?

Dr. John Grohol: Gabe, I think that would be a great thing to look forward to, and I’m going to put it on my calendar.

Gabe Howard: Well, John, I agree, and it’s a date. All right, everybody, here’s what we need you to do. If you like the show, please subscribe. Please rank us. Review us. Use your words and tell people why you like us. Share us on social media. Send us in e-mails, mention us in support groups. If you’re at dinner with your mother and you’re bored, tell her all about The Psych Central Podcast. And remember, you can get one week of free, convenient, affordable, private online counseling anytime, anywhere, simply by visiting BetterHelp.com/PsychCentral. And we will see everybody next week.

Announcer: You’ve been listening to The Psych Central Podcast. Want your audience to be wowed at your next event? Feature an appearance and LIVE RECORDING of the Psych Central Podcast right from your stage! For more details, or to book an event, please email us at [email protected]. Previous episodes can be found at PsychCentral.com/Show or on your favorite podcast player. Psych Central is the internet’s oldest and largest independent mental health website run by mental health professionals. Overseen by Dr. John Grohol, Psych Central offers trusted resources and quizzes to help answer your questions about mental health, personality, psychotherapy, and more. Please visit us today at PsychCentral.com. To learn more about our host, Gabe Howard, please visit his website at gabehoward.com. Thank you for listening and please share with your friends, family, and followers.

from https://ift.tt/2W2kXhE Check out https://peterlegyel.wordpress.com/

0 notes

Text

Podcast: Psych Central Turns 25 This Year

It’s Psych Central’s 25th anniversary! In today’s show, we celebrate the Internet’s largest and oldest independent mental health site with founder Dr. John Grohol. Just a few years after the World Wide Web became public domain, Dr. Grohol was inspired to create an online resource for everyone — a site where patients, clinicians and caregivers could come together to access and share valuable mental health and psychology information.

Join us as Gabe and Dr. Grohol talk about the past, present and future of Psych Central.

SUBSCRIBE & REVIEW

Guest information for ‘John Grohol-Psych central’ Podcast Episode

John M. Grohol, Psy.D. is a pioneer in online mental health and psychology. Recognizing the educational and social potential of the Internet in 1995, Dr. Grohol has transformed the way people could access mental health and psychology resources online. Pre-dating the National Institute for Mental Health and mental health advocacy organizations, Dr. Grohol was the first to publish the diagnostic criteria for common mental disorders, such as depression, bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. His leadership has helped to break down the barriers of stigma often associated with mental health concerns, bringing trusted resources and support communities to the Internet.

He has worked tirelessly as a patient advocate to improve the quality of information available for mental health patients, highlighting quality mental health resources, and building safe, private support communities and social networks in numerous health topics.

About The Psych Central Podcast Host

Gabe Howard is an award-winning writer and speaker who lives with bipolar disorder. He is the author of the popular book, Mental Illness is an Asshole and other Observations, available from Amazon; signed copies are also available directly from the author. To learn more about Gabe, please visit his website, gabehoward.com.

Computer Generated Transcript for ‘John Grohol-Psych Central’ Episode

Editor’s Note: Please be mindful that this transcript has been computer generated and therefore may contain inaccuracies and grammar errors. Thank you.

Announcer: You’re listening to the Psych Central Podcast, where guest experts in the field of psychology and mental health share thought-provoking information using plain, everyday language. Here’s your host, Gabe Howard.

Gabe Howard: Hello, everyone, and welcome to this week’s episode of The Psych Central Podcast. Calling into the show today, we have Dr. John Grohol. Dr. Grohol is the editor in chief of PsychCentral.com and the man who founded Psych Central 25 years ago. John, welcome to the show.

Dr. John Grohol: Great to be with you today, Gabe. It’s an exciting achievement.

Gabe Howard: I’ve never done anything for 25 years. It’s incredibly impressive. And I want to start back twenty six years ago, twenty seven years ago before Psych Central existed. When you were coming up with the idea for this Web site, how did you get this idea?

Dr. John Grohol: So it all began when I was in grad school down in Florida and I had a bad first year in school because I learned about the death of my childhood best friend who took his own life. And that was a difficult thing to come to terms with because none of us saw the situation at the time that he was going through and he didn’t feel comfortable in reaching out to anyone. This was back in 1990 and I needed help, but I didn’t exactly know where to turn. One of the places I ended up turning to was a support group online, and that support group was on a section of the Internet we call Usenet, which hosts newsgroups. We call them newsgroups, they are actually just what we would today call like a discussion forum like Reddit or something or even Facebook, similar in the sense of these were groups set up to discuss specific topics. One of those topics was a depression group. And I just found it astounding, amazing that there was an online support group for depression in 1990.

Gabe Howard: And this is before the Internet was a household name.

Dr. John Grohol: Yeah, this, well, this predates the Web, and that’s why it’s hard to explain and hard to have people wrap their minds around it, because here we are 30 years later and to understand that people were doing online support, emotional support and information sharing thirty years ago. So these are not new phenomenon. So for people to sort of look at the Internet and say, oh, you know, it’s not real or you can’t have a real emotional connection with other people, I laugh at them because we’ve been, people have been having real emotional connections through Internet technologies for well over 30 years, actually goes back even further than that.

Gabe Howard: Yeah, I remember the old, like, bulletin board system days.

Dr. John Grohol: Yeah, yeah, absolutely. CompuServe, AOL and Prodigy too were the commercial services and they also had the equivalent of support groups in their respective services.

Gabe Howard: They did. I used to work for CompuServe serve, and that’s where I found the Internet. So it’s interesting. We’ve got a similar story so far with technology really helping us get through difficult times. And of course, I’m really sorry about the loss of your friend.

Dr. John Grohol: Thank you. It was a really difficult time in my life, and using that support group really helped me and it really helped me understand the power that such support groups held for people, if only they knew about them. The fact that I came upon it, it was only because I had some mad computer skills at the time. Computers were a hobby of mine. So I understood how to search for that type of group on Usenet. At the time, it was not a simple process and you had to be in academia. Back then, you had to be associated with the university as a student or a professor or something even to access that part of the Internet. So that got me thinking, well, if this helped me so much, and it’s helping other people as much as I can see that it is, wouldn’t it be great if more people knew about this? So I started collecting, I started indexing all these support groups that existed back in 1990 and 1991. And I published those indexes on those groups to let people know about other great emotional support and psychology groups that existed so people could find them and find each other.

Gabe Howard: And this was all before PsychCentral.com was a registered domain name.

Dr. John Grohol: Yep, yep.

Gabe Howard: And now here we are. So it’s obviously you did this for five years, which is not an insignificant amount of time. This wasn’t a whim for you. This was something that was a major part of your life for half a decade.

Dr. John Grohol: I was actually deeply involved in newsgroups back then because that was the modality that people used to have online discussions. There was no Reddit. There was no other way of doing that. Well, that’s not entirely true. There’s a thing called mailing lists that still exists today, too. And that’s where you get the online discussion, it comes right to your email box. And those remain widely used in many parts of the Internet.

Gabe Howard: So now we’re at 1995. Twenty five years ago.