#Georges Charbonnier

Text

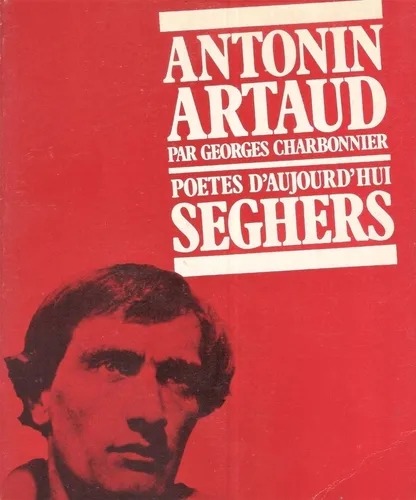

Georges Charbonnier, Antonin Artaud, Poètes d’aujourd’hui, Seghers, 218 pages, Paris 1976.

Georges Charbonnier, Antonin Artaud, Poètes d’aujourd’hui, Seghers, 218 pages, Paris 1976.

Une chronique de Lieven Callant

Georges Charbonnier, Antonin Artaud, Poètes d’aujourd’hui, Seghers, 218 pages, Paris 1976

Essai de Georges Charbonnier, cinquième édition.

Par définition et de manière intrinsèque la poésie échappe à la grille rigoureuse de l’analyse en lui ajoutant un fardeau dont elle aimerait se défaire: le raisonnable. Elle dépasse les mots qui tentent de l’encercler. Cela…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

Claude Laydu and Jean Danet in Diary of a Country Priest (Robert Bresson, 1951)

Cast: Claude Laydu, Jean Riveyre, Adrien Borel, Rachel Bérandt, Nicole Maurey, Nicole Ladmiral, Martine Lemaire, Antoine Balpêtré, Jean Danet, Léon Arvel. Screenplay: Robert Bresson, based on a novel by Georges Bernanos. Cinematography: Léonce-Henri Burel. Art direction: Pierre Charbonnier. Film editing: Paulette Robert. Music: Jean-Jacques Grünenwald.

The still above, of the young priest (Claude Laydu) happily accepting a ride on the back of a motorcycle from Olivier (Jean Danet) is not meant to be representative of the film as a whole. Quite the contrary, Olivier is a cousin of Chantal (Nicole Ladmiral), who, along with the rest of her family, has caused the priest much pain. Olivier is a soldier in the Foreign Legion, a character whose life is about as far from the priest's tormented spirituality as possible. The scene is a brief, liberated one, suggesting a world of potential other than that of the spiritual and physical suffering the priest has known in his assignment to the bleak and hostile parish of Ambricourt. The priest returns to his suffering after his motorcycle ride: He learns that he has terminal stomach cancer and dies in a slovenly apartment watched over by a former fellow seminarian, Fabregars (Léon Arvel), who is living with his mistress. As ascetic as the young priest has striven to be, he has to come to terms with a world that seems irrevocably fallen, even to the point of taking the last, absolving blessing from the lapsed Fabregars. Of all the celebrated masterworks of film, Bresson's Diary of a Country Priest may be the most uncompromising in making the case for cinema as an artistic medium on the same level as literature and music. In comparison, what is Citizen Kane (Orson Welles, 1941) but a rather blobby melodrama about the rise and fall of a newspaper tycoon? Even the best of Alfred Hitchcock's oeuvre is little more than crafty embroidery on the thriller genre. The highest-praised directors, from Ford, Hawks, and Kurosawa to Godard, Kubrick, and Scorsese, never seem to stray far from the themes and tropes of popular culture. Even a film like Ozu's Tokyo Story (1953) falls back on sentiment as a way of engaging its audience. But Bresson strives for such a purity of character and narrative, down to the refusal to use well-known professional actors, and such a relentless intellectualizing, that you can't help comparing his film favorably to the great works of Flaubert or Dostoevsky. Having said that, I must admit that it's a work much easier to admire than to love, especially if, like me, you have no deep emotional or intellectual connection to religion -- or even an outright hostility to it. Does the suffering of the sickly young priest really result in the kind of transcendence the film posits? Are the questions of grace and redemption real, or merely the product of an ideology out of sync with actual human experience? What explains the hostility he encounters in the village he tries to serve: the work of the devil or just the bleakness of provincial existence? On the other hand, just asking those questions serves to point out how richly condensed is Bresson's drama of ideas. I love the movies I've alluded to above as somehow lacking in the intellectual seriousness of Bresson's film, but there's room in the pantheon for both kinds of film. Diary of a Country Priest remains for me one of film's great puzzles: What are we to make of the young priest's intellectualized faith? Is it a film for believers or for agnostics? In the end, these enigmas and ambiguities are integral to its greatness.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

A golden age for aristocratic bastards

[Jean de Dunois, the Bastard of Orleans]

[..] The fifteenth century was the golden age of aristocratic bastards. The very fact that the word bâtard had honourable connotations in old French should alert us to its significance among the nobility but it seems that the late Middle Ages was a particularly favourable period for the illegitimate offspring of nobles for, although they could not inherit apanages or the propres of a family, no stigma attached to the bastard in higher noble circles. A survey of the higher civil and ecclesiastical offices held by bastards between 1345 and 1523 indicates an acceleration of the conquest of such positions in the first half of the fifteenth century and a great concentration in the second half, with 39 such posts held. There are a number of quite clear reasons for all this. Bastards actually bolstered the numbers within a noble family and were used to strengthen its influence either through marriage alliances or by the acquisition of administrative functions. They could be used to protect the influence of the legitimate members of the family without actually threatening their inheritance and, indeed, could be viewed as more trustworthy by their fathers since they posed no direct threat. As love children, they were often viewed as more handsome and personable than their legitimate siblings (the bastard of Dunois is the great case). Thus, as Harsgor reasonably argues, the expansion of their influence represented 'an aggrandisement of the sphere of influence of the nobility in general'. Although Contamine has observed a restriction of bastards' access to higher military commands at the end of the fifteenth century, aristocratic bastards played a significant part in the group of dominant figures, the 'masters of the kingdom', well into the sixteenth. Charles, last count of Armagnac, liberated from prison after the death of Louis XI, left a bastard, Pierre, who had a brilliant career at court under Charles VIII and Louis XII, was invested with the barony of Caussade, and whose legitimised son Georges, cardinal d'Armagnac, in turn became one of the great ecclesiastical statesmen of the sixteenth century. Georges in turn had a bastard daughter to whom La Caussade descended, while he made his nephew his vicar-general.

As far as the royal family itself was concerned, the kings of the fifteenth century tended to recognise only female bastards, using them for careful marriage alliances designed to assemble an affinity around the throne. Other great princely houses produced many more. The family of the Valois dukes of Burgundy produced not less than 68 bastards, many of whom filled important administrative posts and came to be 'a sort of bastardocracy'. Philip the Good alone sired 26 natural children, while there are spectacular cases like Jean II de Cleves with 63 bastards. One further explanation of their rise is the vast increase in military employment offered by the Hundred Years War. Roughly 4 per cent of the commands in the royal armies of the fifteenth century were held by aristocratic bastards.

[Antoine de Bourgogne, the Great Bastard of Burgundy]

While Harsgor argued that it was mainly the higher nobility that used bastards in this way, Charbonnier's study of Auvergne indicates the same pattern existed at the level of the middle and lower lordship. Among families like the Vernines and d'Estaing they were fully accepted and frequently found military employment and wielded their swords in the private feuds of their fathers. Well into the sixteenth century, we find bastards continuing their attachment to the lignage and fighting the feuds of their legitimate brothers. They replaced the earlier phenomenon of the younger sons who served their family but renounced a family of their own; few of them founded their own lignages, contrary to the pattern found among the higher nobility. However, they were mobilised in the service of the lignage, compensating the relative diminution of legitimate offspring, with the advantage of not dismantling the patrimony. However, from the middle of the sixteenth century, although there was no decline in the number of bastards at this level, there are signs that noble bastards were beginning to draw away from simple attachment to the service of their legitimate family and found lignages of their own.

The decline in recognised bastards took place after the first quarter of the sixteenth century, one of the signs being Francis I's reluctance to recognise illegitimate offspring. The Italian wars possibly provided less employment than the internal wars of the fifteenth century, but it seems just as likely that the main reason was the demographic expansion of the legitimate nobility and the squeeze on offices available for them generally. Added to that, both the Protestant and Catholic reforms took a dim view of sexual irregularity and sought to control it, while the higher robe and wealthy commoners had long viewed bastardy as an aristocratic foible to be avoided. For its part, the crown saw the expansion in the number of families exempt from taxes by the foundation of bastard noble lines as a danger. In 1600 and 1629, noble bastards lost their right to inherit nobility (this privilege was henceforth confined to the royal family).

David Potter- A History of France, 1460-1560- The Emergence of a Nation State

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

La Marche des rois - Chant trad. provençale repris par Bizet dans L'Arlésienne (partition,sheet music)

La Marche des rois - Chant trad. provençale repris x Bizet dans L'Arlésienne (partition,sheet music) Easy Piano Solo arr.

https://youtu.be/KsDBOdWDRwQ

The March of the Kings or The March of the Three Kings or, in Provençal, La Marcho di Rèi is a popular Christmas carol of Provençal origin celebrating Epiphany and the Three Kings. Its revival by Georges Bizet for his Arlésienne popularized the theme.

The precise origins of both the tune and the lyrics are uncertain and debated.

The words are regularly attributed to Joseph-François Domergue (1691-1728), priest-dean of Aramon, in the Gard, from 1724 to 1728, whose name appears on the first manuscript copy dated 1742 and kept at the library of Avignon.

The text is published in the Compendium of Provençal and Francois Spiritual Songs engraved by Sieur Hue published in 1759. Subsequently, the work was included in the various editions of the Provençal Christmas collection by the poet and composer of the 17th century Nicolas Saboly (1614-1675) to which it has often — and erroneously — been attributedNote.

According to the 1742 document, the song uses the air of a Marche de Turenne1. This mention corresponds to the established practice of noëlistes consisting in placing their texts on “known” French songs spread by the printing press. One hypothesis is that this Marche de Turenne would be a military march dating back to the 17th century, in honor of the victories of Marshal de Turenne, which some authors wanted to attribute to Lully, although no document corroborates this attribution.

An Avignon tradition rather dates the Marche de Turenne back to the 15th century, at the time of King René (1409-1480) while certain authors from the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century leaned towards a reference to Raymond de Turenne (1352 -1413), known as Le Fléau de Provence, grandnephew of Pope Clement VI and nephew of Pope Gregory XI.

In the 21st century, several American researchers postulate that the March of the Kings has a medieval origin dating back to the 13th century; it could then be one of the oldest Christmas carols listed with Veni redemptor gentium, and perhaps the first entirely composed in the vernacular language, and not in Latin.

According to research carried out by the scholar Stéphen d'Arve at the end of the 19th century, the only known score is that of Étienne-Paul Charbonnier (1793-1872), organist at the cathedral of Aix-en-Provence , who — perhaps taking it from the chain of its predecessors — had reconstructed it from memory, modifying its orchestration as new instruments were introduced.

Henri Maréchal, an inspector of the Conservatoires de France who did research at the request of Frédéric Mistral, thought, for his part, that 'La Marcha dei Rèis' must have been composed by the Abbé Domergue himself.

Covers and adaptations

The March of the Kings is one of the themes of the overture to L'Arlésienne (1872), incidental music composed by Georges Bizet for a drama on a Provençal subject by Alphonse Daudet.

According to the musicologist Joseph Clamon, Bizet was able to find the melody of this march in a book published in 1864. After the failure of the drama, Bizet drew from incidental music a suite for orchestra (Suite no 1) which met with immediate success.

In 1879, four years after the composer's death, his friend Ernest Guiraud produced a second suite (Suite no 2) in which the March of the Kings is taken up in canon in the last part of the revised work.

Certain passages are also found in Edmond Audran's operetta Gillette de Narbonne, created in 188219. The words of a song 'M'sieu d'Turenne', which can be sung to the tune of the March of the Kings, are due to Léon Durocher (1862-1918).

The March of the Kings has become a traditional French song and one of the most common Christmas carols in the repertoire of French-speaking choirs. It has had several covers by performers such as Tino Rossi, Les Quatre Barbus, Marie Michèle Desrosiers or, in English, Robert Merrill. The piece has been adapted many times, notably by the organist Pierre Cochereau through an improvised toccata in 1973 for the Suite à la Française on popular themes.

Read the full article

0 notes

Text

El escritor y su obra: entrevistas de Georges Charbonnier con Jorge Luis Borges

Creo haber visto todas las entrevistas que le han hecho a Borges que son posibles de encontrar en YouTube; varias de ellas las he visto en más de una ocasión, y las mejores (las de Carrizo y las de Soler Serrano, por ejemplo) por lo menos tres o cuatro veces. Incluso cuando se repite o cuando sabes de memoria lo que va a responder oírlo provoca un agrado que pocos otros escritores son capaces de causar al hablar: es casi literatura oral, y así se siente. El punto es que tenía ganas de oír a Borges, pero oírlo decir cosas diferentes o al menos de diferente manera. Lamentablemente, no encontré material videográfico que no conociese (al menos no lo suficientemente largo), por lo que me puse a buscarlo por escrito. Lo que hay en YouTube corresponde a una pequeña parte de las entrevistas que Borges dio en su vida, y aunque muchas de ellas se han perdido para siempre, muchas otras están transcritas y publicadas en libros. De estos encontré dos, y sobre ellos haré un comentario en esta ocasión.

El primer libro que leí corresponde a las entrevistas que le hizo Georges Charbonnier, y el segundo a las que le hizo Roberto Alifano. El de Charbonnier destaca sobre todo por acercarse más a un debate o a un diálogo que a una entrevista, y eso es poco frecuente de ver en las conversaciones que tuvo con periodistas o escritores (el propio Borges se lo reconoce). Entre los temas comentados aparecen varios de sus libros y cuentos, como Historia universal de la infamia, Pierre Menard, autor del Quijote o Funes el memorioso. El segundo libro es considerablemente más extenso y por eso los temas tratados son muchísimos más: sobre literatura policial (lo que agradezco mucho, pues pocas veces se le preguntaba a propósito de esto), sobre el Quijote, sobre la traducción, sobre las enciclopedias, sobre el tango (que no le gustaba nada, por cierto), sobre la poesía, sobre la política, sobre el budismo, sobre el tiempo o sobre los libros; en lo que respecta a escritores, se le pregunta por Carriego, Lugones, Quevedo, Kipling, Virgilio, James Joyce, Alfonso Reyes, Oscar Wilde y Kafka.

Habría muchísimo que citar, pero me quedaré solo con una idea. Dice Borges:

Los hombres vivimos insistiendo demasiado en nuestras pequeñas diferencias, en nuestros rencores y eso no está bien. Si hay algo que puede salvar a la humanidad son las afinidades, los puntos de coincidencia que nos unen a los demás hombres, y evitar, por todos los medios, de acentuar las diferencias.

Dejar de pelear con desconocidos por Twitter es el primer paso para ello. Yo hace bastante ya que decidí dejar de hacerlo, y puedo asegurar que además del tiempo ahorrado (no pocos de los libros aquí comentados no habrían podido ser leídos si hubiese gastado mi tiempo libre en discusiones por Internet) la paz mental que se obtiene vuelve a esta una de las mejores decisiones que se puede tomar.

0 notes

Text

“Shakespeare would have thought, ‘I am going to find words that correspond to Macbeth’s movement of consciousness.’”

Jorge Luis Borges, from Interviews by Georges Charbonnier with Jorge Luis Borges

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Journal d'un curé de campagne (Robert Bresson, 1951).

#journal d'un curé de campagne#Journal d'un curé de campagne (1951)#robert bresson#diary of a country priest#diary of a country priest (1951)#georges bernanos#paulette robert#pierre charbonnier#léonce-henri burel#robert turlure

118 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Stéphane “Charb” Charbonnier, communist cartoonist, head of redaction

Georges Wolinski, communist cartoonist

Jean “Cabu” Cabut, anarchist cartoonist

Bernard Maris, anti-globalization economist

Bernard “Tignous” Verlhac, libertarian-communist cartoonist

Elsa Cayat, psychoanalyst, columnist [likely killed because she was Jewish]

Philippe Honoré, cartoonist

Mustapha Ourrad, copyeditor

+ a building maintenance worker, a visitor, two policemen, and the days afterward another policewoman and four Jewish hostages in related attacks

#charlie hebdo#je suis charlie#charb#stéphane charbonnier#wolinski#georges wolinski#cabu#jean cabut#tignous#bernard verlhac#honoré#philippe honoré#franco-belgian comics

12 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Chaque mot écrit est une victoire contre la mort.

Michel Butor (Entretiens avec Georges Charbonnier)

#quote#quotation#citation#quotes#mot#words#word#écrire#written#victoire#victory#mort#death#livre#book#book lover#bibliophile#Michel Butor#entretiens#Georges Charbonnier#Charbonnier

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

http://www.sam-network.org/video/sur-l-archeologie-du-savoir?curation=0.6

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Capucine leaving the Cartier store, Place Vendôme , Paris, 1953. Photo by Jean-Philippe Charbonnie

Capucine and Claudia Cardinale in a 1963 promotional photo by Georges Dambier for the Blake Edwards film The Pink Panther

Capucine in a photo by Yale Joel, Paris, 1952

Capucine wearing a hat by Jean Barthet, 19522, in a photo by Georges Dambier

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Century Ago, a Donor Walked into the Carnegie Museum

Figure 1: Accession #6163, Donated By Major J.P. Young

What could have inspired someone to arrive at the Carnegie Institute, on a cold winter day to donate a small collection of fossils found while serving in World War I, less than a month after returning to the United States?

Albert D. Kollar, Collections Manager for the Section of Invertebrate Paleontology at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History, discovered this mystery while undertaking a multi-year project to take a fresh look at the Baron de Bayet Collection, a collection of 130,000 fossils purchased by Andrew Carnegie in 1903. While looking at the trilobites, an extinct group of arthropods, Albert noticed a few specimens missing the characteristic “BH” letters and/or labels that typically identify the Bayet collection. After some detective work, Albert uncovered evidence of a previously unknown collection, “a small collection of fossil shells,” from France, that had been donated by a “Major J.P. Young” in 1919. (Figure 1).

Major Young, born in 1873 in Middletown, Ohio, developed a love of collecting early in life, spotting artifacts from indigenous cultures of North America, while working as a surveyor, for the Pennsylvania Railroad. His connection to Pittsburgh was further strengthened by his marriage to Margaret Young Oliver, daughter of George T. Oliver, industrialist and United States Senator from Pennsylvania. After World War I, John and Margaret settled in Ithaca, New York, where John was affiliated with his alma mater, Cornell University, for the remainder of his life. From 1925-1935, he painstakingly illustrated eight volumes of diatoms, single celled algae with sharp exterior coatings made of silica. Many of these illustrations were published by Dr. Mathew Hohn in 1951. During World War II, John Young volunteered as a “dollar a year man;” so that a Cornell staff member could serve in the war effort. After the war, he returned to his fascination with indigenous artifacts when he reorganized the Seneca and Cayuga collections of the DeWitt Museum in Ithaca, New York. But his longest tenure of service involved the Cornell Paleontological Research Institution (PRI), which he joined in 1934. He served as president from 1941-43 and remained active until his death in 1957. Fellow members of the PRI described him as “scholarly and pleasant” in a memorandum published after his passing.

Which brings us back to those fossils. In 1917, at age 44, John Paul Young joined the United States Army, and was tapped to lead the 5th Trench Mortar Battalion, a unit of 600 soldiers. Sometime between September and November of 1918, while managing his soldiers’ cold, thirst, hunger, and conditions such as “trench foot,” a complication from extreme wetness and cold that could turn a soldier’s foot into a gangrenous mass, Major Young may have noticed fossiliferous rocks at the bottom of a trench along the Western Front in Vitrey-sur-Mance, France (Figure 2). Intrigued to find fossils in a trench, the Major collected and then later donated them to the Carnegie Institute in 1919.

Figure 2: French Locations of Carnegie Trilobites

This fall, Albert travelled to Paris to visit the Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle in Paris seeking to uncover this 100-year-old French trilobite mystery. Albert met with Dr. Sylvain Charbonnier, Collections Manager of Invertebrate Paleontology at the Muséum to discuss this puzzle. Albert’s query is to verify the genus, species, age, and stratigraphic locality of these trilobites. At this point, his preliminary research indicates that the Bayet trilobites are distorted and preserved in a black siltstone rock, that Albert recently coated with a white salt to enhance the fossil detail (Figure 3). In contrast, the three trilobites without labels possibly attributed to Major Young (see Figure 4) are also distorted; but preserved in a brown iron color siltstone. The iron oxide coating gives them a reddish appearance. They too are coated with a whitish salt to enhance detail.

Figure 3: Sample of a Bayet Trilobite from Vitré

Figure 4: Trilobites From Major Young Donation

An established paleontological collecting method, crucial to the identification of specimens, is to know the exact placement of the fossil to the stratigraphic locality (rock layer) which can support a known geologic age verified in the Geologic Time Scale. If someone makes a collection, such as the Baron de Bayet, and a paper label is preserved (Figure 3) then, Albert must confirm through paleontology literature and the geologic map of France, all known stratigraphic localities in the region for evidence of similar trilobites. For example, the Vitré label in Figure 3, establishes the location for this trilobite as Bretagne in the northwest of France. To ascertain the proper locality of the Major’s donation (Figure 4), we assume at this point, that it is from Vitrey-sur-Mance in the northeast of France; but further research is planned to resolve the exact location of the of the trenches that the Major occupied in World War I.

Following the advice of Dr. Charbonnier, Albert will proceed to digitize all 50 plus trilobites and send these images and other documentation to the Paris Muséum for further review. While we await the results, the fact that the fossils are sparking a new vein of research is probably exactly what the Major had hoped for all along.

Joann Wilson is the Interpreter for the Department of Education and Volunteer for the Section of Invertebrate Paleontology at CMNH and Albert Kollar is the Collections Manager for the Section of Invertebrate Paleontology. Museum staff, volunteers, and interns are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

Many thanks to the fabulous Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh staff, with special acknowledgment to Carnegie Museum Library Managers, Xianghua Sun and Marilyn Cocchiola Holt, and Carnegie Reference Librarians Joanne Dunmyre and Leigh Anne Focareta. Special thank you to Peter Corina at the Kroch Library, Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections at Cornell University.

#Carnegie Museum of Natural History#Invertebrate Paleontology#Bayet Collection#Trilobites#Fossils#Carnegie Institute

51 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Capucine leaving the Cartier store, Place Vendôme , Paris, 1953. Photo by Jean-Philippe Charbonnie

Capucine and Claudia Cardinale in a 1963 promotional photo by Georges Dambier for the Blake Edwards film The Pink Panther

Capucine in a photo by Yale Joel, Paris, 1952

Capucine wearing a hat by Jean Barthet, 19522, in a photo by Georges Dambier

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

“I like dance very much. Dance is an extraordinary thing: life and rhythm. It is easy for me to live with dance. When I had to compose a dance for Moscow, I had just gone to the Moulin de la Galette on Sunday afternoon. And I watched the dancing. I especially watched the farandole. Often, in the middle or at the end of a session there was a farandole. This farandole was very gay. The dancers hold each other by the hand, they run across the room, and they wind around the people who are standing around ... it is all extremely gay. And all that to a bouncing tune. An atmosphere I knew very well. When I had a composition to do, I returned to the Moulin de la Galette to see the farandole again. Back at home I composed my dance on a canvas of four metres, singing the same tune I had heard at the Moulin de la Galette, so that the entire composition and all the dancers are in harmony and dance to the same rhythm.”

Henri Matisse, Interview with Georges Charbonnier, 1951.

2 notes

·

View notes