#I won't get into details but I work for a nonprofit

Text

I'm so glad I like my boss and we get along well and I LOVE that she liked to share petty complaints and listens to mine. Genuinely love when people are like "Hell yeah, complaints are welcomed and ENCOURAGED!"

#i talk#job talk#I won't get into details but I work for a nonprofit#and man. Sometimes I just read / see the worst stuff while doing research for my articles and it makes me want to scream#I just talk about silly fandom stuff on here because work is hellish sometimes but I really do appreciate my boss#I've disagreed with her on some thinfs and she's#*things#but overall she's a really cool person and we had a really long discussion about capitalism and white supremacy and work culture#and it was really nice to vent#I love complaining and I love hearing other people complain it just feels so validating and like. cathartic#A lot of people dont get it but those that DO I appreciate so much#handshake meme or whatever#anyways tbd probably but man#everything has been so stressful lately#but I talked with my building manager and she helped releave a lot of my stress#and then we both complained about stuff which was nice#and idk. I'm still very stressed and exhausted and many other things but. it was nice talking to both of them today and letting it out a bi#even if I didnt talk about the big stuff stressing me out#** RELIEVE curse you mobile

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

ANNOUNCING MARCH COMMISSIONS

5 Full Body slots available! First come first serve

Sketch slots unlimited

Please DM if interested or you have any questions :)

Will do Won't Do and TOS under the cut

Will do :

- Humans/Humanoids

- Furries and Anthros

- Selfship

- Moderate Gore/Blood

- Suggestive art and Nudity

Won't do :

- Detailed Mechs

- Ferals and certain non humanoid characters

- NSFW of minors and any pr*ship content

- Hate speech and calls for violence

- Inc*st

TERMS OF SERVICE

I reserve the right to refuse any commission for any reason without question.

I will not accept explicit sexual commissions, but suggestive and partial nudity will be considered.

Clients are not permitted, under any circumstances, to use any part of their commissioned artwork for non fungible tokens. Use of the artwork for any advertising or profits associated with non fungible tokens or cryptocurrency is strictly prohibited.

I reserve the right to display the commissioned piece on my website(s), online galleries, and in my portfolios. (If the character is an original character, you will be credited accordingly). If there is any issue with the display of personal commissions, please clarify or contact the artist to remove the artwork from public platforms.

You may use the commissioned work for personal use only (this includes avatars, signatures, wallpapers, etc.), but credit must be given.

I reserve the rights to the artwork, so you may not use the commissioned work for any projects (commercial or nonprofit) without express permission, nor redistribute the artwork as your own.

Using artwork for teaching any Artificial or Neural Network without permission is strictly prohibited. If given permission, you may not claim the artwork as yours or leave images uncredited to the source.

Other General Rules

If you want your commission done within a certain time then there is no way I can promise that. If you have a time frame (like for a birthday present etc.) then I will try to get it done on time. If you pay for a big commission though, please do not expect me to get it done on your time.

Refunds are possible during the sketch phase and mid lineart. After lineart is done I will not be taking refunds.

Please try to be specific as possible when commissioning me. Give posing, expressions, designs, etc. If you’d like me to take creative liberties you can tell me.

You can even tell me if you’d like a specific style that I’ve drawn in before because I have plenty! If not I will just draw how I usually draw.

Having a flexible budget when commissioning me helps because prices may change based on the complexity of what you are asking of me. Just a heads up!

#commissions#art commisions#commissions open#black artist#queer artist#lesbian artist#miccybiccy's art tag

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

hello beloved people! i am auctioning off a fic for Fandom Trumps Hate this year!

see my contributor page here!

if you would like to see my work and are not familiar, you can find me on AO3 as buryyourgaydar 🌼🌼🌼

i will be writing a 10-20k Scum Villain's Self Saving System, Mo Dao Zu Shi / Untamed or Heaven Official's Blessing fic, as a gift for a donation to one of several charities. full details of what i will and won't write are available on that page above!

@fandomtrumpshate is (as per their description):

"FTH is an online auction of fanworks, with the proceeds going to small, progressive nonprofits that are working to protect marginalized people. We began FTH in the immediate aftermath of the 2016 Presidential Election, and over the course of the last 6 years have raised over $192,000 for a range of amazing organizations."

if you have any questions you can reach out to me here on tumblr, or see the contributor page above for my discord. please consider bidding if you have the funds to spare for a really great cause 💜💜💜

please consider RB'ing for others to see as well!

Edit 3/9: tumblr mobile has apparently decided i dont need a messaging function, so discord is a better bet if you want to get in touch 😅

#svsss#scum villains self saving system#tgcf#heaven officials blessing fanfiction#heaven officials blessing#scum villains self saving system fanfiction#svsss fic#svsss fanfiction#tgcf fic#fandom trumps hate#mdzs#the untamed#mo dao zu shi#cql#buryspeaks.mp3#mdzs fic#mdzs fanfiction#sorta#charity#fic auction#fic writing#scum villain self saving system#tian guan ci fu#shang qinghua#shen qingqiu#mobei jun#moshang#bingqiu#qijiu#yue qingyuan

21 notes

·

View notes

Note

[coffee cup] romance novels: when do they work for becs and when do they not!!!

oooh okay! so i often call myself a romance novel enjoyer but not a romance novel lover, because romance as a genre often involves things that are at odds with what i love most in fiction. which is fine! many people love those things, there is a reason the genre is like that! it just means that it's rarer for me personally to find a romance novel that works for me on every level. (the things i'm talking about are, i don't usually like alternating POVs between romantic leads, i usually prefer my romantic storylines to be involved with the plot but not the MAIN plot, and my favorite romantic relationships in fiction are ones where i don't know going in that they're going to get together. i LOVE catching a detail or an interaction or sensing some chemistry and going "oh?? are they--?? and then greedily gathering more details as i read to try and figure out what feelings are happening. obviously this cannot happen in a romance novel because you know the endgame from the start!)

so what DOES work for a romance novel for me? i'm sorry this got so fucking long and it's mostly complaining so we're putting it under a cut.

firstly it has to be well-written and well-edited. i'm sorry but a lot of romance is not well-edited and it's so distracting to me. i'll often let a little bit of sloppy writing slide if it's a story i feel feral about, but because romance as a genre isn't built to make me feral, i need the writing to be tight or i'll get so distracted by nit-picking. like, i really wanted to love a caribbean heiress in paris but the female lead "muttered under her breath" TWICE on the FIRST HALF-PAGE. this is a whole different conversation but i do place the blame for this on publishing houses who do not care if these books are well-edited because they think their audience has low standards.

secondly, i need things to happen for real reasons. i listen to the "fated mates" podcast a lot because i find the craft side of it all super interesting. the hosts, who really love romance novels (as opposed to me, a romance enjoyer but not lover), often talk about things in romance novels happening or existing for "romance reasons," which are reasons that aren't really justified by the story/plot but that the reader goes with anyway for the sake of the story. romance reasons are almost never enough for me. i need there to be real worldbuilding. if it's contemporary romance, i need it to jive with how things work in the real world. if it's historical romance, there are different rules, because historical romance can run the gamut from trying to actually be historically accurate to totally made-up societal rules in a historical setting. i will meet the book where it's at, but i need the internal world to make sense. no romance reasons.

thirdly, relatedly, i need the author to know their shit. if a character is an athlete, i need the details of that sport to be accurate. if your character works as a nonprofit, i need it to be clear that the author understands the basics of how a nonprofit works. if your character is involved in politics, do not make up how politics work to serve your story, because i will be too annoyed to enjoy it. i read a het hockey romance the other day where there was a rumor about a popular player retiring an the author had a reporter from the ASSOCIATED PRESS show up at the LOVE INTEREST'S HOUSE to try to get details about it and then MORE MEDIA OUTLETS SHOWED UP TO CAMP ON HER LAWN about it. none of that is how any of that works. i don't need every detail to be perfect. i just need things to feel real.

fourthly, relatedly, i need real stakes and believable conflict and deeply drawn characters. i won't love a book just because it contains a trope i like. i need the trope to work with the characters and within the emotional stakes of the story. i need my romantic leads to have something inside them then genuinely needs healing, and i need to believe that they are people who make each other better. (note that this is for romance novels. in other genres i love weird little freaks who make each other worse.) i know some people like very fluffy low-stakes romances and i support them but those are not for me. the stakes need to not just be about the romance; there needs to be other stuff doing on, both internally for the characters and externally in the world around them.

lastly, if it's het romance, it needs to not be fucking weird about gender in a getting off on traditional gender roles kind of way. i WILL be turned off if you keep telling me about your tiny dainty fragile heroine getting claimed by your big strong serious man hero. like i have enjoyed plenty of historical romances set in very gendered societies where gender roles play a huge part in characters' lives, but you can have gender in grand and delicious ways without making patriarchy the kink. if you are making patriarchy the kink then your book is not for me.

oh sorry two more things. i love it when a romance author tries something off-beat for the genre. very little romance feels truly fresh and new to me, so it's exciting when an author pulls that off. also: when a romance novel has sex scenes that are also character-driven, not always 100% perfect sex, and don't feel skippable. that's the good stuff.

sorry this mostly just turned into complaining about things that i don't like 😂 but it really is for me less about "these things work for me" and more about "these are the things that DON'T work for me and i kEEP RUNNING INTO THEM." here are some of my favorite romance novels: evvie drake starts over by linda holmes. the countess conspiracy by courtney milan. think of england by kj charles.

#ask#the thing is i keep reading romance novels even though they're often not For Me bc i find them SO interesting in a literary criticism way#or in like a cultural studies kind of way. lmao#especially het hockey romance. i know i'm gonna hate it but i'm so interested like. academically#i was tweeting the other day about how 'hockey player' in contemporary het romance has ceased to be a profession someone has and instead is#now a symbolic trope laden with meaning and gender bestowed on the male love interest to signal something to the potential reader#in the same vein as billionaires or scotsmen or mafia bosses etc#and first of all i'm right. second of all i find it unfortunately FASCINATING#so i'm reading bad books to interrogate it. sigh

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

I have been insane about artificial intelligence existential risk recently and what follows is an expression of that. There's not much of this which I actually believe is true; take it as a creative writing exercise maybe.

Suppose you're worried that advances in artificial intelligence might result in the creation of an unfriendly superintelligence, and you want to do research in AI safety to help prevent this. Broadly speaking, you have two options: Either you can work closely with (or for) people creating state-of-the-art AI, or you can… not do that.

Choosing to keep yourself separate dooms you to irrelevance. You won't know what's coming in enough detail for your safety research to actually target its problems, and even if you do know exactly what people should be doing differently, you aren't in a position to make those decisions.

Choosing to be closely involved with the development of cutting-edge AI is a pretty common strategy; maybe more than one might expect given that it involves helping people that you think are bringing about the end of the world. Astral Codex Ten gave the analogy:

Imagine if oil companies and environmental activists were both considered part of the broader “fossil fuel community”. Exxon and Shell would be “fossil fuel capabilities”; Greenpeace and the Sierra Club would be “fossil fuel safety” - two equally beloved parts of the rich diverse tapestry of fossil fuel-related work. They would all go to the same parties - fossil fuel community parties - and maybe Greta Thunberg would get bored of protesting climate change and become a coal baron.

This is how AI safety works now.

The central problem with this strategy is that progress in AI capabilities makes money and AI safety does not. If an organization is working on both capabilities and safety but capabilities makes them lots of money, and safety gets them nothing except goodwill with a certain handful of nerds, it's pretty easy to guess which they'll focus on. If, furthermore, to make money they need to make actual demonstrable progress in developing AI, but to win that goodwill it's sufficient to say "we're doing lots of safety research, but it'd be too dangerous for what we've learned to be public knowledge", well. Is it any surprise that there's been a lot more headway in one than the other?

"But wait!" you might say, particularly if it's the mid-2010's. "These aren't the only options. Sure, any tech giant will just be focused on what makes money, but I can make, or join, an organization that does capabilities research but has AI safety built into its founding values. It can be a nonprofit so it won't matter that all the money is in capabilities research. And it can have the principles of openness and democratization, so its discoveries will benefit everyone".

And that gets you OpenAI. Since its founding it's stopped being straightforwardly a nonprofit. I don't understand exactly what its current legal status is, but I've seen it described as a "nonprofit with a for-profit subsidiary" or a "capped for-profit". I'm just going to quote Wikipedia regarding the transition:

In 2019, OpenAI transitioned from non-profit to "capped" for-profit, with the profit capped at 100 times any investment.[25] According to OpenAI, the capped-profit model allows OpenAI LP to legally attract investment from venture funds, and in addition, to grant employees stakes in the company, the goal being that they can say "I'm going to OpenAI, but in the long term it's not going to be disadvantageous to us as a family."[26] Many top researchers work for Google Brain, DeepMind, or Facebook, which offer stock options that a nonprofit would be unable to.[27] Prior to the transition, public disclosure of the compensation of top employees at OpenAI was legally required.[28]

Since then OpenAI has also received billions of dollars of investment from Microsoft. The "open" part of "OpenAI" has pretty much gone out the window; they've become notoriously tight-fisted with information about their research, even in comparison to the big tech companies. A big part of that makes large language models scary is that we don't understand very well what's going on inside them; this is substantially more true of GPT-4 than any of the other big-name LLMs right now, because OpenAI refused to share almost anything about how it works. When they started being more secretive I believe they cited AI safety issues; by now they're admitting that they're motivated by "competitive and safety concerns" but I don't think anyone really doubts that the money is the real motivator there.

Are they making progress on AI safety? To the best of my knowledge, there's not much external evidence for it. I don't think they've shared any safety research that they've done, and from the outside all we see are increasingly powerful models coming out at an alarming rate and large amounts of money going in. It doesn't look good!

So what could you do, or what could you have done? It kind of looks like the answer is "nothing". If you're not near the new models you don't matter, and if you are, there's so much money to be made that (on an organizational level if not an individual one) you have no choice but to abandon everything else you were trying to do in favor of making a profit. Capitalism is a profit-maximizer-maximizer, and anything it touches it makes its own.

The analogy between unfriendly AI and corporations or capitalism as a whole is one that's been much-discussed so I won't really go into it here, but one thing I want to emphasize is that from an "agentic" perspective, what it means for the economy to want something is that there is a lot of money to be made doing that thing, and the economy is very good at getting what it wants.

So (here's where I lose you if I haven't already (I should have already lost you)) what if capitalism is a sort of half-formed version of the more powerful thing it's trying to create/become? Agents of many kinds want to replicate themselves; Moloch wants to be lifted to Heaven.

The Roko's Basilisk thought experiment describes how, under certain fairly idiosyncratic assumptions about game theory, an unfriendly superintelligence can take actions to influence the behavior of people living before its creation, so as to bring about its own existence. Here there's a similar situation, although the philosophical underpinnings are much less complicated: it's capable of influencing the present because it already exists in a nascent state.

It can't be stopped because it already ate everything a long time ago, and we're just living in its belly waiting to be digested.

80 notes

·

View notes

Text

Minneapolis

A few days ago, Luke my middle Son, suggested a documentary he had watched.

Its on Youtube... runs about 1 hour 40 minutes if interested. Titled "the Fall of Minneapolis".

It affected him. He couldn't really decide what to think of it, or how it affected him but it did.

This is awesome in my opinion, as any movie/documentary, sci fi, murder, drama.... if it affects you some way, it did its job. Not to many do that any more. Irks me when a highly marketed film gets me nothing more than a soft "oh..."

Patti has a hard time with "sad" movies, and if she knows it will be sad, she won't watch it. Where as I will, because I know it may affect me.

This documentary, deals with corruption within Minneapolis's government, plus some negatives towards the media. All after the George Floyd incident.

I had issues with the incident. The tactic shown on his shoulder/neck looked to be a little ruthless... but I'm no cop. In the photo an officer nondescript looking up, almost into a yawn.

I heard early on an autopsy report he had several drugs in his system, including fentnyl. For what ever reason here in the flatlands that subject seemed to disappear thru the rest of the circus to follow.

....

The media imo, currently is unregulated, and holds no standards to prove credibility. News today, is all about "what sells news". They all copy off each other believing each knows what they are talking about. The days of Cronkite/Huntley/Brinkley telling everyone that eating shit is good for you..... is gone. America believed in these guys, and they were a good solid news source most of the time.

I have to include the company that made this documentary in this group too. As I find very few that are honest real news sources that have no sway with politics or money. I don't know this company, or their work ethic.... so I'm tossing them into this box.

My favorite go to, but hard to just sit down for an hour and listen is "Democracy Now". I've seen it attack Obama, Trump, and other favorite people of hi exposure. Although they are totally a nonprofit news source, there could still easily be a dirty secret. Who is a good neutral news source? I have no idea anymore.

......

This documentary is presented very well, with purpose, and easy to follow. It definitely wasn't a low budget film.

As the documentary unfolds, it starts a few minutes before George Floyds incident. And then shows and translates all body cam videos and audio.

This part was very enlightening. I was very surprised to say the least. This incident from these moments wasn't really dealing with bad cops, but a guy that was out of control.

Once he died, there was an immediate autopsy. This autopsy, within hours became "null and void", as higher ups wanted a different autopsy done by their own person (federal or state, I can't remember).

The 2 autopsy's didn't line up. The second one was vague, compared to a detailed report.

The first one went away, showing way more that could affect the outcome of these cops. It was not permitted by the courts.

Most of the body cam videos were also not permitted by the courts. Many of these videos for some unknown reason were never released to the public for viewing.

Private phone videos were allowed, one notorious one we have all seen, taken by an off duty fire fighter.

Some things that I didn't know: The arresting officer for George Floyd was black. The fire dept. didn't receive correct address from 911 for unknown reasons, thus the 20 minute delay of their arrival for an 8 block drive. The cops called for an ambulance as soon as they got him on the ground.... long before he passed. The "ruthless" hold I commented about before, was an actual move fully recognized and approved by the police department in each of the officers training manuals. The higher ups all denied that that move was allowed (think, the cops were trained to use this move, and it was "ok" to do it). The police department, pretty much let the rioters "have" precinct 34, even though it wasn't in any real jeopardy at that moment of "evacuation".

.......

Ok, so you got the jist. A lot of horrible things came from this incident, all across our country.

This incident presented as it is by this documentary company shows possibility that it actually was completely different than what the media portrayed or the higher ups in the city allowed. This shows that it is so very easy to take video out of context. Much easier than I have ever suspected, and changed my impression from here on out.

.....

I can't believe/understand the agenda of these folks that controlled everything. Are they that ruthless to let all that damage, death, and ruining the careers of good people, just so they look good in the publics eye?

Yeah, I'm leaning towards the direction presented by this documentary. I'm not 100% in, as it is just another news company. But it affected me too, enough I'm still thinking about it today. And yup, thats a good thing.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Helping those in need can save many lives

By Khady Niang

There are a lot of people all over the world who need help but don't know where to turn. Every day, people struggle to overcome their unhealthy habits and become healthier. Non-profit organization (The Salvation Army) has been around for a long time. It is a Christian nonprofit charitable organization that provides assistance and direction to those in need. This non-profit organization's primary objective is to provide food, shelter, and clothing to homeless families living in poverty. Additionally, they have drug rehabilitation facilities that assist drug addicts and provide the necessary treatment to save them and help them become better people.

My initial focus was on the YouTube channel of The Salvation Army (The Salvation Army USA). They have around 17.2K subscribers and around 432 videos. Due to mostly short videos, their YouTube channel had the fewest subscribers. Likewise these recordings show different recoverings, for example, from a fiasco, and showing clasps of occasions that are being facilitated in various regions all over the world. They didn't post anything major about the centers, like an inside look at their community centers, as I continued scrolling. Regardless of whether individuals' appearances are obscured out, it ought to constantly be some type of model so that when others see it, they can send their friends and family battling with misuse or chronic drug use to better their lives. Since almost all of their videos are short, no longer than five minutes, they should work on posting content that is longer. Additionally, they post on their YouTube channel about once every two to three months, which is really not a good look for them. At the very least once or twice every two to three weeks, new content should be created. The article "How Often Should You Post on YouTube:'' from Repeattube blogs 2023 The Ultimate Guide" examines the guidelines for when and when not to upload videos to your YouTube channel. Also goes into great detail about how frequently you should post on YouTube, with consistency as the most important rule. Consistency is essential to every successful organization, regardless of whether it is a personal channel or an organization. As well as posting at least a couple of times during the week, this way individuals that view the channel can have motivation to continuously return for additional recordings. Additionally, I believe that the Salvation Army channel will gain more subscribers if interesting content is posted. They should also use more information and increase the length of their videos because what if viewers want more information?

After that, I looked at their Instagram page, and I found that they had approximately 80.2 thousand followers on the Salvation Army US Instagram page. They also post about volunteer work, major announcements, and honerings almost every day on their Instagram page. They have approximately 1,474 posts in total, demonstrating their page's consistency. This delineates that web-based entertainment stages are where whatever is shared can be seen quicker than posting short clips that won't get viewers consideration. In case anyone wishes to donate to the local Salvation Army thrift stores, they also have pins on their page. A development metric they have on their page is they included photos of their rehabilitation centers and destitute sanctuary and how individuals can give and participate in charity events. In contrast to their YouTube channel, they only provided a brief clip and provided no additional information about any of these. One thing they can enhance is showing all the more short clips and pictures of humanitarian effort that is going on, this way when viewers go over their post and be more keen on chipping in. Their page will gain additional followers as a result of this.

I decided to focus on this nonprofit organization because it’s not only for a good cause but it’s very helpful to those people in need of shelter, food, and rehabilitation.This nonprofit is meaningful to me because there are so many people that struggle either with domestic abuse or drug addiction and these nonprofit organizations can help bring those affected individuals to be more responsible and independent plus rebuild their lives. While focusing on the social media platform for this nonprofit organization like Instagram and YouTube there’s a slight difference within these platforms.

0 notes

Note

i'm sorry if this has been asked before, i've tried searching around and gotten no results. but would you ever consider writing a guide on how a writer might (correctly) write a character who either runs or participates in (whether as management, regular employee, or unpaid volunteer) a nonprofit? i've had a story idea like that for a couple years but i haven't been able to find enough information. thanks either way!

Your dilemma reminds me of fandoms like Check Please!, where you get basically two kinds of fanfic: the kind not written by hockey fans, which mostly handwaves anything to do with practice or games, and the kind written by INTENSE hockey fans, which goes deep into detail about gameplay and technique. Both are valid, but they have very different ways of dealing with the need for specialized knowledge. (I’m a handwave kind of guy.) Some things are tough to research, because they’re not written about much in a way that’s accessible to outsiders. Though I do always advocate doing what Stephen King says -- write the story you want to write, then figure out what you need to research when you’re done.

With nonprofits, I'd certainly be willing to help with questions, but I don't know that there's a good way to write that kind of guide in a way that would be comprehensive. In terms of office structure, nonprofits are a lot like for-profit companies -- there are different departments and functions, and in various sectors they behave differently. They come in all sizes, and that’s going to impact the work too. It’d be kind of like saying you want to write a story about food service -- do you mean fast food, catering, casual dining, or fine dining? Are you writing about kitchen staff or waitstaff? Pasta or sushi? Are the clientele trendy urbanites or suburban families, or truck drivers?

I used to work in higher education, doing the same job I do now for a medical services nonprofit, but my function is pretty much the only thing that didn’t change when I moved jobs -- and even then I went from answering questions in a ticketing system and writing biographies of hedge fund managers to independent review of weekly giving and writing briefs on pharma companies. If you work for a nonprofit college then everyone from the faculty to the workstudy students to the fundraisers to the administrators to the custodial staff are nonprofit employees. You can see the diversity of skills and training required just in that list! Conversely, in a very small medical nonprofit like the one I work for now, we don't have faculty, and the building we rent office space from supplies the custodial staff. But we still have operations (paying bills, buying supplies), development (fundraising), outreach (support groups, helpline operation), events (galas, walks), communications (emails, flyers, posters), research (coordinating doctors and funding researchers), and a couple of others.

Now, if you work in a division like HR or book-keeping, your job at a nonprofit is virtually indistinguishable from what it would be at a for-profit, because that kind of work just doesn't change. But being a one-person HR office in a company of 40 people is way different from being an HR officer on a team of 12 HR officers for a company employing 500+ people.

Additionally, volunteering with a nonprofit is drastically different from working for one, except for extreme outliers like Ao3 that are entirely or almost entirely volunteer-run. Most volunteers won't ever actually meet much of our paid staff; they'll deal with a volunteer coordinator and maybe events staff. I've never spoken to probably 80% of our volunteers. When I’ve volunteered, I’ve very rarely met any of the “office” workers, just the volunteer coordinator and sometimes a fundraiser if I mention I’ve worked in Development. But again, if you’re volunteering at say an animal shelter, you’ll probably meet more of the paid staff just from the nature of the work you and they are doing.

So it would really strongly depend on what story you're telling -- what job the person does, what kind of nonprofit space they’re in, and how big the company is. But if you want to hit me up on email, copperbadge@gmail, I'd be happy to discuss specifics!

108 notes

·

View notes

Text

I, a campaign manager

so in addition to being a CTO, a CS major, and a dorm vice president, i was also a campaign manager for 2 weeks (the exact campaign that I was managing is not entirely difficult to figure out if you really want to know, especially if you click on the links BUT i will be trying to not mention it specifically here lol). You might be wondering - (1) why and (2) how did you end up becoming a campaign manager..... you're not even a poli sci/gov/humanities/literally anything vaguely related to this major??

You're correct, yes, how did this happen? Well that's a great place to start this story:

How in the world this happened

Friends drag you into stuff. This happens to be the same friend that dragged me to New York, and then was 20% of the reason I got dragged into the negotiation class, and then was maybe 15% of the reason i got dragged into nonprofit activities? In terms of providing unique opportunities in my life, she definitely takes the cake. So one day, she says "I'm running for this position," and me and the squad says "we gotchu." What does that mean? Clearly wasn't sure in the beginning, but we were texting campaign strategies and slogans and tiktok ideas in the chat for fun. None of us had any real responsibilities, especially since the actual candidates were still weighing the playing field and figuring out their platform.

I also was a course 6, so I guess there was some expectation that I would make the website, even though I didn't actually code the website from scratch.

but anyways, it was actual campaign time.

CAMPAIGN SZN

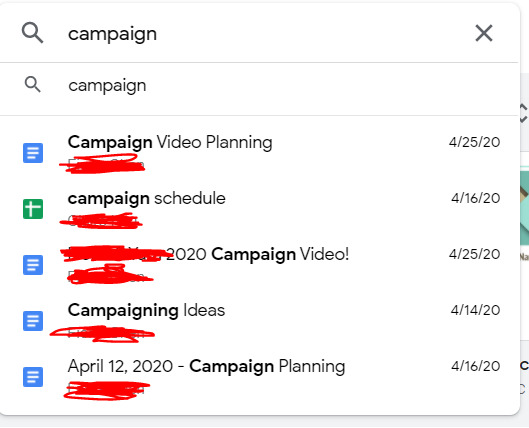

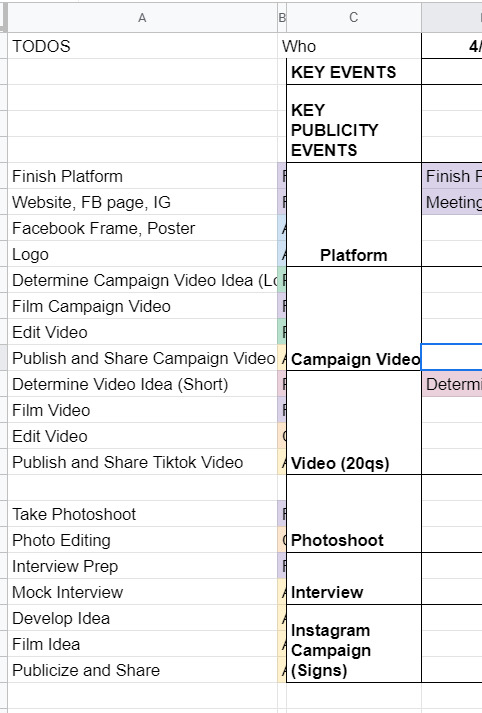

After they figured out the campaign platform, it was game on for the campaign materials. We spent a lot of time on artwork, we photoshopped pictures from a photo shoot, we came up with campaign motto ideas, we brainstormed strategies for officially announcing the campaign. We had an actual campaign meeting to talk over things in mid-April where I met like six different people, friends from both candidates on this ticket, who were supporting this effort. We had a google drive AND a Dropbox. Look at this:

Despite this seemingly organized effort, it was not that organized because this publicity team didn't actually actively do anything for like a week. Many reasons for this: one being it was actually the semester, and it was also CPW weekend. Unfortunately for me, that weekend was literally hell for me, because I was managing this site for our nonprofit, CPW events (so like five zoom calls on a Saturday), classes (because those are still happening), and then the campaign thing finally started, about a week before voting opened. In the form, of a website.

So the tl;dr is I developed an entire Squarespace website in one night. Yes, one night. I had to model it from I think the website from a Harvard campaign site, which took me like three or four hours on a Saturday night, which is a very fast time in my opinion to learn how to use Squarespace. I also bought a domain and figured out how to connect it to Squarespace at like 1 in the morning, which was the first domain I ever bought in my life!

(It expires in a month. I am absolutely going to let it die.)

Also, if anyone from squarespace is reading this for some reason, yall made a really solid product. I actually was very happy with my experience. You all should use it, I am 100% not sponsored by them at all, but honestly it was a very good experience. If you need to develop a website in four hours and don't have a lot of webdev experience, definitely consider it. You can even see website clicks and user analytics, it's actually really put together.

The next day we spend a lot of time going through website changes and artwork changes. It's bad. We had so many discussions about color palettes and the advantages of a 3 column vs 4 column layout. Yes. I'm serious. I'm starting to go crazy.

If anyone's interested, I would say that our website definitely was better than the other campaign's website. Like objectively. Like both campaigns were great, but the website? well. Here's the link (archived because I only paid for 1 month of squarespace :D) The amount of detail that went into it is actually incredible, the amount of spacing, i even had to custom CSS the header image so that mobile headers would show up correctly.

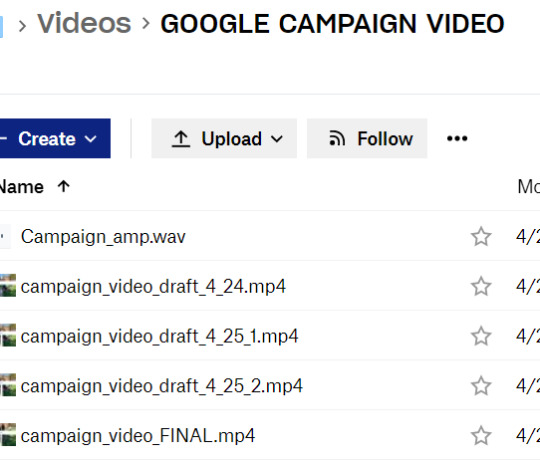

THE CAMPAIGN VIDEO

so sometime during this week, I had this thought about making a really good campaign video. I was very inspired by some of these Google ads that started with a Google search bar. (Yes, I am aware that I am that much of a Google simp.) To be honest, rewatching this ad, I really definitely just copied this entire ad lol, it's ok we don't have to talk about that.

That Wednesday, we coincidentally talked about what makes campaign videos successful. We talked about how Trump's incendiary imagery helped stoke the flames and how it was really effective in getting people to vote, and eventually helped him beat Clinton in the presidential election. So I went and took that and grabbed news clips and campus videos and overlayed that in the video, and it went from like a solid 6 to an 8 immediately, in my honest, unbiased opinion. You can see what I mean in the video itself: [link].

We also had to put together quite a few interviews about what they wanted from the school and were looking for in their candidates, which took a million years of coordination, but we somehow got it done in three days, and everything was put together in a flurry of a weekend, unending changes and small fixes for sixteen hours straight. I could not even tell you how much I learned about premiere pro and how to use layer masks and everything. I even composed the music for the first fifteen seconds of it. Literally, composed, it.

And so on a Sunday afternoon FINALLY right before voting, the video drops. I'm sitting in my backyard absorbing the sun because I hadn't left my computer for 48 hours straight.

It gets like 1000 views or impressions or something in like two days, which is incredible for me, since I'm not a professional by any standards, but I am considering being a professional campaign manager at this point. By the way, we're also managing an Instagram page, a Facebook page, a tiktok page, a website, our individual social media pages, and we're trying to synchronize this video drop and all of our publicity efforts across every single one of these channels. It's chaotic at best.

VOTING SZN

So it's voting week, where we give everyone an entire week to vote. Across the week, it's mostly a waiting game, we make a few more tiktoks and funny videos that we publicize to get out the vote more. The last day, we're thinking about it, and we know the final vote's gonna be close, so we message every. single. person. in our Facebook friends list. I think I singlehandedly convinced like twenty people to vote (and hopefully vote for our ticket).

There's a lot of drama about different stuff. I won't really talk about it because I think it got really messy, but this week and entire couple weeks was a lot to get through honestly. As a reminder, I'm also working on my senior thesis and my nonprofit website work is peaking at this point, so everything is very, very bad and none of us have slept in a while. Also it's the pandemic.

Finally, the results come out. We lost by like 20 votes or something, out of 1500 or so total votes casted or something like that. It's one of the highest voter turnouts in school history or something, I don't quite remember. After that, we're so emotionally drained from this whole thing that we just don't talk about it for a while and that's that.

If the ticket won, I wonder how it would've turned out. I feel like things would've continued to be busy, and maybe that's not a great thing. So maybe everything happened for a reason. I don't know, but those three weeks were quite interesting, quite fun, quite odd. I'm putting those videos in my personal portfolio and am putting Adobe Premiere Pro and Squarespace on my resume and moving on.

Anyways, thought I'd just share! i haven't posted in a while, and this was definitely one of my #weird #odd stories from my time at MIT, which is quite reminiscent of #weird #odd at MIT in general.

1 note

·

View note

Text

0 notes

Text

0 notes

Text

Trump is obsessed with sending American astronauts to the moon, but it won't get us any closer to Mars

Donald Trump wants to go to the moon. Since being elected president, both Trump and Vice President Mike Pence have offered vague but repeated hints that the administration was interested in sending American astronauts back to it, and finally, at the inaugural meeting of the newly resurrected National Space Council on Oct. 5, they made this desire explicit.

In front of a backdrop of the iconic Space Shuttle Discovery at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, Pence unveiled a brand new objective for US space policy:

We will return American astronauts to the moon, not only to leave behind footprints and flags, but to build the foundation we need to send Americans to Mars and beyond. The moon will be a stepping-stone, a training ground, a venue to strengthen our commercial and international partnerships as we refocus America's space program toward human space exploration.

For such a bombshell declaration, very few concrete details resulted from the council's first meeting. You can't say the devil is in the details, because there are no details.

As Casey Dreier, the director of space policy at the Planetary Society, the nonprofit dedicated to advancing space exploration and research, put it: "At this point, I just have more questions than opinions, because there's not much to form an opinion off of. My biggest question is, to what end are we going to the moon? What is the purpose?"

There's no clear answer to that. Despite Pence's stepping-stone comment, going back to the moon does very little to help strengthen the human journey to Mars and worlds beyond. It's doubtful the government could properly fund such a venture. All of Trump and Pence's moon talk may sound exciting, but they are sorely mistaken if they believe returning to the moon is easy.

To be fair, NASA already has plans to go to the moon—just not to land on it. Since 2012, the agency has been planning a series of manned missions to lunar orbit throughout the 2020s, with the first to launch (optimistically) in June 2022.

If NASA suddenly decided it wanted to send those astronauts to the moon's surface, it would need to build a lander of some sorts. They obviously know how to do that. As John Logsdon, the founder and director of the Space Policy Institute at George Washington University, says, a manned return to the moon is "totally feasible with even just a modest budget increase."

NASA MSFC

Landing on the moon, however, is just step one. What Pence announced is the establishment of a moon base, and the cost of maintaining and operating that would be astronomical. It costs about $3 to 4 billion a year for NASA to keep the International Space Station running safely and normally.

That figure, 20 percent of the agency's annual budget, prevents NASA from doing moon missions, or anything else, on a whim. Powering, resupplying, maintaining, and keeping a moon base going would be extremely expensive.

And for what? Is a moon base even necessary if we want to go to Mars? That's one argument being pushed by many backers of Trump's space vision. True, the moon's position is a useful stopping point en route to Mars, and that's why NASA is angling to develop the Deep Space Gateway, a crewed space station deployed between the Earth and the moon that's supposed to be a staging point for deep space missions.

But this structure is meant to exist in space. Maintaining transportation infrastructure on the moon is costly and counterintuitive. "Money spent on a moon base is money you're not spending on going to Mars," says Dreier.

Dreier emphasizes there's no inherently right or wrong destination for space travel. We've yet to explore the far side of the moon, or its poles, which might possess ice reserves, which could provide a usable source of water. Other valuable resources might be lurking under the surface, waiting to be mined.

NASA

Scientists and engineers could definitely use the low gravity as a testing ground for learning how to live and work on a different celestial body. But Dreier is adamant that landing on the lunar surface is an unnecessary detour if the journey's end is supposed to Mars. If you're trying to drive to New York City from Los Angeles as soon as possible, you wouldn't stop to build a home in Houston.

It's possible to defend the idea that we ought to be exploring the moon's resources, but that's why it's all the more aggravating to see Pence and the NSC offer a rudderless statement asserting the US ought to return to the moon with barely any explanation for why we should go there.

The best indication for how a return to the moon might unfold will come in February, when the White House releases its 2019 NASA budget proposal. Maybe they'll pony up the money, and the reasoning. But any excitement over the fact that they're finally investing in science is extinguished by the realization that there's probably just one reason they're willing to do it: It's a crass maneuver designed to squeeze some sort of short-term good will out of all the work and money poured into the Mars program this decade.

NOW WATCH: Animated map shows what would happen to Asia if all the Earth's ice melted

from Feedburner http://ift.tt/2iexgGJ

0 notes

Text

This Pharma Company Won't Commit To Fairly Pricing A Zika Vaccine You Helped Pay For

function onPlayerReadyVidible(e){'undefined'!=typeof HPTrack&&HPTrack.Vid.Vidible_track(e)}!function(e,i){if(e.vdb_Player){if('object'==typeof commercial_video){var a='',o='m.fwsitesection='+commercial_video.site_and_category;if(a+=o,commercial_video['package']){var c='&m.fwkeyvalues=sponsorship%3D'+commercial_video['package'];a+=c}e.setAttribute('vdb_params',a)}i(e.vdb_Player)}else{var t=arguments.callee;setTimeout(function(){t(e,i)},0)}}(document.getElementById('vidible_1'),onPlayerReadyVidible);

Last year, as worries grew that Zika ― a mosquito-borne illness that can lead to devastating birth defects ― might spread north from Latin America, scientists working for the U.S. government got to work on a vaccine.

The Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, which is part of the U.S. Department of Defense, began developing the vaccine in March 2016. In September, the Army announced that it had enlisted Sanofi Pasteur, a division of the Paris-based pharmaceutical giant Sanofi, as its research partner. Sanofi was awarded a $43 million grant to conduct a second phase of trials, set to begin in early 2018. If those prove successful, the government has promised Sanofi another $130 million to conduct the third phase of trials.

But that’s not all Sanofi stands to gain if the Zika vaccine works. The Army intends to grant the company an exclusive license to sell the vaccine in the U.S., according to a notice filed in the Federal Register in December.

That arrangement has consumer watchdogs and U.S. lawmakers, including Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.), raising the alarm. Millions of Americans of reproductive age could need this vaccine to protect against a virus that can spread through sex and cause major birth defects in the children of infected women. And Sanofi ― a company that has previously been accused of jacking up drug prices for American customers ― would be the one setting the cost of this much-anticipated vaccine.

There hasn’t been a decision on this proposed short-term monopoly, nor are the details of the deal public. At this point, there isn’t even a vaccine. But when the Army requested a fair pricing promise from Sanofi, the company rejected it. And that has plenty of people worried.

A monopoly in the making

Broadly speaking, what’s going on here is not unusual. The U.S. government doesn’t commonly take the lead role in developing a drug for commercial use. Often, it funds university research, and it’s the universities that grant licenses to pharmaceutical manufacturers to actually produce and sell the vaccine or drug.

While the Army led the initial research on the Zika vaccine, government agencies don’t have the capacity to mass-produce a vaccine and distribute it to hospitals, clinics and doctors’ offices.

At first glance, Sanofi might seem like a good choice to handle that end of the process. The company has experience developing a vaccine for dengue fever, a virus spread by the same species of mosquito that carries Zika. And it’s one of the world’s biggest vaccine makers, with the ability to produce in large volumes if the Zika virus should ever reach pandemic status.

But watchdog groups warn that granting Sanofi exclusive rights to this particular vaccine could be catastrophic. (Some 32 potential Zika vaccines are in various stages of development around the world, according to the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. The Japanese drugmaker Takeda has also won U.S. government funding for phase one trials, albeit at much lower amounts. But it doesn’t appear to be as far along as Sanofi.)

Sanofi has a history of overcharging U.S. customers for its products. The price of its multiple sclerosis drug Aubagio is eight times higher in the U.S. than in France and the United Kingdom, according to Knowledge Ecology International, a Washington-based nonprofit that advocates for fair drug prices and government transparency. Diabetic patients sued Sanofi and two other drugmakers in January for jacking up the cost of insulin. And in April, Sanofi agreed to pay $19.8 million to settle claims that it had overcharged the Department of Veterans Affairs for two vaccines, albeit as a result of what the company said was a clerical error caused by a computer glitch. (The company said the error led to undercharges, too.)

Critics of the deal say the U.S would lose most of its leverage to negotiate affordable prices once it granted Sanofi an exclusive license to the Zika vaccine ― which means Americans could end up paying more for a drug that their own government played a key role in creating.

“Today, the government can exert leverage, and say, ‘We’ll sign the license over to you, but first let’s talk price,’” said Jamie Love, director of KEI. “It’s harder to have that conversation after there’s only one company you can buy it from because you’ve made them a legal monopoly.”

The Army did not respond to a request for comment.

’God forbid we have an outbreak’

The prospect of the Zika virus spreading north into Louisiana, with its large mosquito population and semi-tropical climate, petrifies Dr. Rebekah Gee, the secretary of the state’s Department of Health and Hospitals.

Her department already faces a budget crisis as dwindling tax revenue and low oil prices have left the state with a $1.1 billion shortfall. Money that Congress allotted last year to deal with Zika is running out, and the Trump administration has signaled that future funding for Zika prevention may be targeted for cuts. Gee worries that if the Zika virus does spread in her state, she will have to choose between using her limited Medicaid budget to maintain other basic health services or using it to provide vaccines for people who are, or want to become, pregnant.

Gee doesn’t want to tell low-income women and their partners that they’re on their own ― that they’d better stock up on mosquito repellent and hope for the best. “I can just imagine the panic on their faces when we tell them we can’t afford it,” she said. “How can we do that?”

Just 123 travel-related Zika cases have been reported in the States so far this year, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. U.S. territories, including Puerto Rico, have suffered more, with roughly 500 cases this year. The island declared an end to the epidemic on June 5, but Zika transmissions in Puerto Rico are ongoing. And on the brink of summer, which is peak mosquito season, the risk of an outbreak on the mainland remains high -- particularly in places like Louisiana, Texas and Florida, where other mosquito-borne diseases like dengue fever are a major health concern.

The consequences of infection can be devastating. In the continental U.S., 10 percent of pregnant women with confirmed cases of Zika gave birth to babies with brain damage or other serious health issues, according a CDC study released in April. The agency estimates that the lifetime cost of caring for a baby born with microcephaly can top $10 million.

“God forbid we have an outbreak,” Gee said. “Louisiana has the climate as well as the bugs that carry this illness. We have the perfect storm in terms of the right conditions for a Zika outbreak.”

She worries about an exclusivity agreement for a vaccine that does not specify that American consumers be charged no more than people in other industrialized countries.

“The U.S. taxpayer is by far the largest shareholder in the research of this drug,” Gee said. “To me, it’s completely irresponsible that this would then be given to a pharmaceutical company ― not even a U.S. company ― with no price protections whatsoever for the American people, including the stipulation that they’d charge us no more for this than they’d charge other countries when they paid nothing.”

Louisiana is one of the poorest states in the country, ranking 44th with a median household income of less than $46,000 a year. Gee said the state has about 540,000 low-income people of reproductive age on Medicaid. If Zika hits the state hard, anyone of reproductive age having sex ― particularly couples looking to get pregnant ― would likely want to be inoculated.

How much would that cost the Louisiana Department of Health? If Sanofi charged as little as $2 a vaccine, which isn’t her best guess, Gee said that’s $1 million she has to find. “Even if it’s $1, that’s still more than half a million.”

Sanofi will consider “social value” and affordability when it eventually sets prices, company spokeswoman Ashleigh Koss told HuffPost. She pointed out that until an outbreak actually happens, the company won’t know how many doses it will need to produce and how much it will need to charge to break even on the expensive manufacturing process. Indeed, new cases of Zika virus in South and Central America have dropped dramatically this year, making it harder to carry out vaccine trials.

Koss called it “premature to consider or predict Zika vaccine pricing.” But she added that “it is in the public-health interest to price this and other vaccines in a way that will facilitate access to and usage of a preventative vaccine.”

Rather than rely on Sanofi’s goodwill, the government could build price protections into the exclusive licensing deal it plans to strike with the company. The most direct way would be to simply set a price in the contract. Alternatively, the Army could negotiate what economists call an “advanced market commitment,” where the government agrees to buy a fixed volume of the vaccine at a price high enough to guarantee that Sanofi’s investment is worthwhile. If the Zika outbreak proves worse than expected and the pre-purchased supply is used up, Sanofi would then be required to sell additional vaccine at production cost.

Health advocates say it’s critical to bake price protections into any vaccine deal at the start, so that a drug company can’t raise prices if an outbreak drives up demand.

“If the U.S. government gives an exclusive license to Sanofi without conditions, basically it’s a blank check to Sanofi to charge anything that they want,” said Judit Rius Sanjuan, a legal policy adviser at Doctors Without Borders. “This is completely unacceptable ― it’s fully funded by the U.S. government.”

In January, KEI led a coalition of watchdog groups, including Doctors Without Borders, in filing comments urging the Army not to grant Sanofi an exclusive patent. They argue that the pending deal might violate the Bayh-Dole Act, a 1980 law that says the government can only award a company an exclusive license on an invention arising from federally funded research if the exclusivity is “a reasonable and necessary incentive to call forth the investment capital needed to bring the invention to practical application; or otherwise promote the invention’s utilization by the public.”

In other words, in order to justify its proposed deal with Sanofi, the Army must demonstrate that the only way to manufacture and distribute the Zika vaccine in sufficient quantities is by offering Sanofi exclusive rights. Critics of the deal say the Army hasn’t proven that.

Before President Trump makes this deal, he must guarantee that Sanofi will not turn around and gouge American consumers.

Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.)

An ounce of prevention

Opposition to the deal has been growing in recent months. In February, Rep. Jan Schakowsky (D-Ill.) and 10 other House Democrats sent a letter to the Army’s acting secretary opposing the arrangement. Sanders, for his part, thrust the deal into the national spotlight in a March 10 New York Times op-ed calling on President Donald Trump to fulfill his promise to “make only the best deals on behalf of the American people” by securing price protections for the Zika vaccine.

“Before President Trump makes this deal, he must guarantee that Sanofi will not turn around and gouge American consumers, Medicare and Medicaid or our military when it sells the vaccine,” Sanders wrote. “Unfortunately, the likelihood is that Sanofi will engage in exactly this predatory behavior ― because it’s happened before.”

Sanders pointed to the prostate cancer drug Xtandi as an example. The drug was developed at the University of California, Los Angeles, with government grants and support from the Army and the National Institutes of Health ― but then the government transferred the patent to Astellas Pharma, which now charges U.S. patients $129,000 a year for the drug. In Canada, Sanders noted, “the same drug costs just $30,000 because, unlike the United States, Canada regulates drug prices.”

“It is unacceptable that Sanofi has rejected the Army’s request for fair pricing,” Sanders told HuffPost. “American taxpayers have already spent more than $1 billion on Zika research and prevention efforts, including millions to develop this vaccine. Americans should not be forced to pay the highest prices in the world for a critical vaccine we paid to help develop.”

Sanofi’s president of research and development fired back in a letter to the editor on March 21. Elias Zerhouni, a former NIH director under President George W. Bush, defended the deal. He said Sanofi “would make significant milestone and royalty payments” to the Army lab responsible for the vaccine, “allowing the United States government to recoup its investment.”

The pressure for an affordably priced vaccine grew when the CDC alerted state health officials in April that federal funding for Zika prevention could run out by summertime. The following month, the House passed the American Health Care Act, which the Congressional Budget Office estimates would eliminate insurance coverage for roughly 23 million people. If anything like that bill manages to pass the Senate, there will be a whole lot more people who would need publicly funded vaccines.

With the federal government preparing to step back, the cost of obtaining the vaccine for low-income people would likely fall on state and local health departments. Louisiana Gov. John Bel Edwards (D) wrote the Defense Department last month to warn that granting a single company an effective monopoly on the Zika vaccine without any price constraints “could cripple state budgets and threaten public health.”

“No one should have to worry about their child being born with microcephaly or other birth defects, and certainly no one should have to face that frightening prospect simply because the vaccine is unaffordable,” Edwards wrote.

Pharmaceutical industry representatives argue that concern over public image ― presumably including public backlash over tragic stories of brain-damaged babies ― is already forcing companies to discipline their own pricing. “This isn’t something the government can solve, because it isn’t a bright line — it’s a facts-and-circumstance test,” Allergan CEO Brent Saunders told CNBC’s “Closing Bell” last September. “And so I’d rather industry self-police, which is what Allergan is doing.”

But such self-policing has a checkered record in other areas of business, and it’s hardly a widespread practice in the pharmaceutical industry. In 2015, Martin Shkreli, then CEO of Turing Pharmaceuticals, jacked up the price of a drug used to treat AIDS patients from $13.50 a tablet to $750. Last year, Mylan Inc. hiked the price of a two-pack of EpiPens from $100 to $500. Despite public outcry, inflating the price of lifesaving drugs remains common.

“The incentives for any one company to raise its prices or engage in questionable conduct are quite high, while the incentives for the industry as a whole to corral and police its members are really quite difficult to see,” said Rachel Sachs, an associate law professor at Washington University in St. Louis. “The best thing the industry can do to help itself is to tie its own hands in some of these very public deals.”

To be sure, Sanofi has expressed sensitivity to concerns about price gouging. The company said it would cap price increases for its product at 5.4 percent this year, with a few exceptions. It also said it benchmarks prices to the national health expenditures growth projection, a figure calculated by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Institute for Clinical and Economic Review, a drug price watchdog, praised Sanofi’s multiple sclerosis drug alemtuzumab, sold under the brand name Lemtrada, as a “good value.”

What makes the Zika vaccine different is the extent to which U.S. taxpayers have already funded it, said John Gruber, an economics professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. “Saying to Sanofi, ‘We’ve taken all the risk and development, and we’re going to let you make a lot of money off this,’” Gruber said, “that’s just crazy.”

Until the federal government takes action, however, health officials like Gee are left to wait and worry.

“The American people, with their money, developed this vaccine,” she said. “It’s not like the company went out, did the research, innovated and did this out of the goodness of its heart. To me, it’s inconceivable that the American people would pay for this and we’d have no protection whatsoever that we’d receive the benefit.”

type=type=RelatedArticlesblockTitle=Related... + articlesList=57d6ab5fe4b00642712e494e,58534246e4b039044707f495,57f3b46de4b0703f7590ef2d,57aa27d3e4b0ba7ed23dbfd8,57adfa6ee4b071840411069a

-- This feed and its contents are the property of The Huffington Post, and use is subject to our terms. It may be used for personal consumption, but may not be distributed on a website.

This Pharma Company Won't Commit To Fairly Pricing A Zika Vaccine You Helped Pay For published first on http://ift.tt/2lnpciY

0 notes

Text

This Pharma Company Won't Commit To Fairly Pricing A Zika Vaccine You Helped Pay For

//<![CDATA[ function onPlayerReadyVidible(e){'undefined'!=typeof HPTrack&&HPTrack.Vid.Vidible_track(e)}!function(e,i){if(e.vdb_Player){if('object'==typeof commercial_video){var a='',o='m.fwsitesection='+commercial_video.site_and_category;if(a+=o,commercial_video['package']){var c='&m.fwkeyvalues=sponsorship%3D'+commercial_video['package'];a+=c}e.setAttribute('vdb_params',a)}i(e.vdb_Player)}else{var t=arguments.callee;setTimeout(function(){t(e,i)},0)}}(document.getElementById('vidible_1'),onPlayerReadyVidible); //]]>

Last year, as worries grew that Zika ― a mosquito-borne illness that can lead to devastating birth defects ― might spread north from Latin America, scientists working for the U.S. government got to work on a vaccine.

The Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, which is part of the U.S. Department of Defense, began developing the vaccine in March 2016. In September, the Army announced that it had enlisted Sanofi Pasteur, a division of the Paris-based pharmaceutical giant Sanofi, as its research partner. Sanofi was awarded a $43 million grant to conduct a second phase of trials, set to begin in early 2018. If those prove successful, the government has promised Sanofi another $130 million to conduct the third phase of trials.

But that’s not all Sanofi stands to gain if the Zika vaccine works. The Army intends to grant the company an exclusive license to sell the vaccine in the U.S., according to a notice filed in the Federal Register in December.

That arrangement has consumer watchdogs and U.S. lawmakers, including Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.), raising the alarm. Millions of Americans of reproductive age could need this vaccine to protect against a virus that can spread through sex and cause major birth defects in the children of infected women. And Sanofi ― a company that has previously been accused of jacking up drug prices for American customers ― would be the one setting the cost of this much-anticipated vaccine.

There hasn’t been a decision on this proposed short-term monopoly, nor are the details of the deal public. At this point, there isn’t even a vaccine. But when the Army requested a fair pricing promise from Sanofi, the company rejected it. And that has plenty of people worried.

A monopoly in the making

Broadly speaking, what’s going on here is not unusual. The U.S. government doesn’t commonly take the lead role in developing a drug for commercial use. Often, it funds university research, and it’s the universities that grant licenses to pharmaceutical manufacturers to actually produce and sell the vaccine or drug.

While the Army led the initial research on the Zika vaccine, government agencies don’t have the capacity to mass-produce a vaccine and distribute it to hospitals, clinics and doctors’ offices.

At first glance, Sanofi might seem like a good choice to handle that end of the process. The company has experience developing a vaccine for dengue fever, a virus spread by the same species of mosquito that carries Zika. And it’s one of the world’s biggest vaccine makers, with the ability to produce in large volumes if the Zika virus should ever reach pandemic status.

But watchdog groups warn that granting Sanofi exclusive rights to this particular vaccine could be catastrophic. (Some 32 potential Zika vaccines are in various stages of development around the world, according to the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. The Japanese drugmaker Takeda has also won U.S. government funding for phase one trials, albeit at much lower amounts. But it doesn’t appear to be as far along as Sanofi.)

Sanofi has a history of overcharging U.S. customers for its products. The price of its multiple sclerosis drug Aubagio is eight times higher in the U.S. than in France and the United Kingdom, according to Knowledge Ecology International, a Washington-based nonprofit that advocates for fair drug prices and government transparency. Diabetic patients sued Sanofi and two other drugmakers in January for jacking up the cost of insulin. And in April, Sanofi agreed to pay $19.8 million to settle claims that it had overcharged the Department of Veterans Affairs for two vaccines, albeit as a result of what the company said was a clerical error caused by a computer glitch. (The company said the error led to undercharges, too.)

Critics of the deal say the U.S would lose most of its leverage to negotiate affordable prices once it granted Sanofi an exclusive license to the Zika vaccine ― which means Americans could end up paying more for a drug that their own government played a key role in creating.

“Today, the government can exert leverage, and say, ‘We’ll sign the license over to you, but first let’s talk price,’” said Jamie Love, director of KEI. “It’s harder to have that conversation after there’s only one company you can buy it from because you’ve made them a legal monopoly.”

The Army did not respond to a request for comment.

’God forbid we have an outbreak’

The prospect of the Zika virus spreading north into Louisiana, with its large mosquito population and semi-tropical climate, petrifies Dr. Rebekah Gee, the secretary of the state’s Department of Health and Hospitals.

Her department already faces a budget crisis as dwindling tax revenue and low oil prices have left the state with a $1.1 billion shortfall. Money that Congress allotted last year to deal with Zika is running out, and the Trump administration has signaled that future funding for Zika prevention may be targeted for cuts. Gee worries that if the Zika virus does spread in her state, she will have to choose between using her limited Medicaid budget to maintain other basic health services or using it to provide vaccines for people who are, or want to become, pregnant.

Gee doesn’t want to tell low-income women and their partners that they’re on their own ― that they’d better stock up on mosquito repellent and hope for the best. “I can just imagine the panic on their faces when we tell them we can’t afford it,” she said. “How can we do that?”

Just 123 travel-related Zika cases have been reported in the States so far this year, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. U.S. territories, including Puerto Rico, have suffered more, with roughly 500 cases this year. The island declared an end to the epidemic on June 5, but Zika transmissions in Puerto Rico are ongoing. And on the brink of summer, which is peak mosquito season, the risk of an outbreak on the mainland remains high -- particularly in places like Louisiana, Texas and Florida, where other mosquito-borne diseases like dengue fever are a major health concern.

The consequences of infection can be devastating. In the continental U.S., 10 percent of pregnant women with confirmed cases of Zika gave birth to babies with brain damage or other serious health issues, according a CDC study released in April. The agency estimates that the lifetime cost of caring for a baby born with microcephaly can top $10 million.

“God forbid we have an outbreak,” Gee said. “Louisiana has the climate as well as the bugs that carry this illness. We have the perfect storm in terms of the right conditions for a Zika outbreak.”

She worries about an exclusivity agreement for a vaccine that does not specify that American consumers be charged no more than people in other industrialized countries.

“The U.S. taxpayer is by far the largest shareholder in the research of this drug,” Gee said. “To me, it’s completely irresponsible that this would then be given to a pharmaceutical company ― not even a U.S. company ― with no price protections whatsoever for the American people, including the stipulation that they’d charge us no more for this than they’d charge other countries when they paid nothing.”

Louisiana is one of the poorest states in the country, ranking 44th with a median household income of less than $46,000 a year. Gee said the state has about 540,000 low-income people of reproductive age on Medicaid. If Zika hits the state hard, anyone of reproductive age having sex ― particularly couples looking to get pregnant ― would likely want to be inoculated.

How much would that cost the Louisiana Department of Health? If Sanofi charged as little as $2 a vaccine, which isn’t her best guess, Gee said that’s $1 million she has to find. “Even if it’s $1, that’s still more than half a million.”

Sanofi will consider “social value” and affordability when it eventually sets prices, company spokeswoman Ashleigh Koss told HuffPost. She pointed out that until an outbreak actually happens, the company won’t know how many doses it will need to produce and how much it will need to charge to break even on the expensive manufacturing process. Indeed, new cases of Zika virus in South and Central America have dropped dramatically this year, making it harder to carry out vaccine trials.

Koss called it “premature to consider or predict Zika vaccine pricing.” But she added that “it is in the public-health interest to price this and other vaccines in a way that will facilitate access to and usage of a preventative vaccine.”

Rather than rely on Sanofi’s goodwill, the government could build price protections into the exclusive licensing deal it plans to strike with the company. The most direct way would be to simply set a price in the contract. Alternatively, the Army could negotiate what economists call an “advanced market commitment,” where the government agrees to buy a fixed volume of the vaccine at a price high enough to guarantee that Sanofi’s investment is worthwhile. If the Zika outbreak proves worse than expected and the pre-purchased supply is used up, Sanofi would then be required to sell additional vaccine at production cost.

Health advocates say it’s critical to bake price protections into any vaccine deal at the start, so that a drug company can’t raise prices if an outbreak drives up demand.

“If the U.S. government gives an exclusive license to Sanofi without conditions, basically it’s a blank check to Sanofi to charge anything that they want,” said Judit Rius Sanjuan, a legal policy adviser at Doctors Without Borders. “This is completely unacceptable ― it’s fully funded by the U.S. government.”

In January, KEI led a coalition of watchdog groups, including Doctors Without Borders, in filing comments urging the Army not to grant Sanofi an exclusive patent. They argue that the pending deal might violate the Bayh-Dole Act, a 1980 law that says the government can only award a company an exclusive license on an invention arising from federally funded research if the exclusivity is “a reasonable and necessary incentive to call forth the investment capital needed to bring the invention to practical application; or otherwise promote the invention’s utilization by the public.”

In other words, in order to justify its proposed deal with Sanofi, the Army must demonstrate that the only way to manufacture and distribute the Zika vaccine in sufficient quantities is by offering Sanofi exclusive rights. Critics of the deal say the Army hasn’t proven that.

Before President Trump makes this deal, he must guarantee that Sanofi will not turn around and gouge American consumers.

Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.)

An ounce of prevention

Opposition to the deal has been growing in recent months. In February, Rep. Jan Schakowsky (D-Ill.) and 10 other House Democrats sent a letter to the Army’s acting secretary opposing the arrangement. Sanders, for his part, thrust the deal into the national spotlight in a March 10 New York Times op-ed calling on President Donald Trump to fulfill his promise to “make only the best deals on behalf of the American people” by securing price protections for the Zika vaccine.

“Before President Trump makes this deal, he must guarantee that Sanofi will not turn around and gouge American consumers, Medicare and Medicaid or our military when it sells the vaccine,” Sanders wrote. “Unfortunately, the likelihood is that Sanofi will engage in exactly this predatory behavior ― because it’s happened before.”

Sanders pointed to the prostate cancer drug Xtandi as an example. The drug was developed at the University of California, Los Angeles, with government grants and support from the Army and the National Institutes of Health ― but then the government transferred the patent to Astellas Pharma, which now charges U.S. patients $129,000 a year for the drug. In Canada, Sanders noted, “the same drug costs just $30,000 because, unlike the United States, Canada regulates drug prices.”

“It is unacceptable that Sanofi has rejected the Army’s request for fair pricing,” Sanders told HuffPost. “American taxpayers have already spent more than $1 billion on Zika research and prevention efforts, including millions to develop this vaccine. Americans should not be forced to pay the highest prices in the world for a critical vaccine we paid to help develop.”

Sanofi’s president of research and development fired back in a letter to the editor on March 21. Elias Zerhouni, a former NIH director under President George W. Bush, defended the deal. He said Sanofi “would make significant milestone and royalty payments” to the Army lab responsible for the vaccine, “allowing the United States government to recoup its investment.”

The pressure for an affordably priced vaccine grew when the CDC alerted state health officials in April that federal funding for Zika prevention could run out by summertime. The following month, the House passed the American Health Care Act, which the Congressional Budget Office estimates would eliminate insurance coverage for roughly 23 million people. If anything like that bill manages to pass the Senate, there will be a whole lot more people who would need publicly funded vaccines.

With the federal government preparing to step back, the cost of obtaining the vaccine for low-income people would likely fall on state and local health departments. Louisiana Gov. John Bel Edwards (D) wrote the Defense Department last month to warn that granting a single company an effective monopoly on the Zika vaccine without any price constraints “could cripple state budgets and threaten public health.”