#IsshoNihongo

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Furigana & Okurigana

As you progress with your Japanese studies, you will see two very important kinds of Hiragana. They are called furigana and okurigana. In this post let’s take a look at each of them and how they both help Japanese learners and natives read Kanji!

But first, let me introduce a chart for the vocabulary that you’ll see in this post. Each word is written in Kanji and then in Hiragana, with its part of speech and meaning.

1) Furigana

Furigana, also known as よみがな or ruby, are the Hiragana characters either on top or to the side of Kanji characters.

As you can see, if the writing is horizontal, the furigana will be on top and if the writing is vertical, it will be on the right side. Either way, furigana tell you how to pronounce the Kanji characters.

There may be anywhere from 1 to 5 Hiragana characters represented by a single Kanji character!

We Japanese learners need furigana when we start studying Kanji and reading Japanese text. But Japanese children also need furigana when they are learning Kanji and even Katakana. Here you can see furigana used to learn Katakana characters.

Whether or not you see furigana depends on a few different factors:

the intended readers

the rarity of the Kanji

Generally, you won’t see many examples of furigana. However, if you pick up a book/novel intended for elementary-aged children, you might see lots of furigana. This is because (like us!) they either haven’t learned the Kanji’s readings or the writer intended the Kanji to be read in a certain way.

Some websites, books, IG posts, Youtube videos, etc that are intended for non-Japanese readers will also have a fair amount of furigana. Granted, it is helpful at first, but it’s a good idea to wane yourself off of furigana as you get better (or if you WANT to get better). The more you see a Kanji character, the more likely you are to remember its reading.

Gikun

Sometimes furigana doesn’t actually tell you the reading of the Kanji. Instead it’s used to add details or add shades of nuance, as in the examples below:

In these cases we call the furigana gikun, which loosely translates to “a false reading”.

On the left, the Kanji reads 希望, which means “desire or wish” but the furigana reads ひかり, which means “light”. This conveys to the reader that light is a metaphor for hope in whatever setting you are seeing that Kanji.

On the right, the Kanji reads ��きゅう, which means “Earth” but the furigana reads ふるさと which means “home town” or “where someone is from”. This tells the reader that someone is an Earthling – as compared to a Martian or an alien from another planet.

This is a more-advanced way that furigana is used, so you won’t see it unless you are reading manga or novels aimed for native speakers.

First the Word, Then the Kanji (Ateji & Jukujikun)

On the day that I arrived in Japan, they asked me for my name in Katakana at the airport. I hadn’t really thought about it so they wrote my name how it sounds to the Japanese ear.

A few days later, I was thinking about this, and it occurred to me that in the same way that they just “assigned me” katakana, I could also give myself Kanji for my name! My name is Albert but I took my nickname Al and “Hiraganized” it, getting ある. At this point I needed 1 or 2 Kanji that sounded out ある. I eventually decided on 亜琉. I’ll come back to this a bit later.

亜琉 is what is called ateji. I started with a word and “worked backwards” to end up with Kanji, based on their readings. Another example of ateji is the Japanese word for The United States. Written with Hiragana it’s あめりか, but written with Kanji it becomes:

亜 read as あ 米 read as め 利 read as り 加 read as か

Keep in mind that these Kanji have nothing to do with the meaning of “America” or “The U.S.” (whatever that is lol). They were only chosen based on the way you read each Kanji. This is the idea of ateji.

A similar concept is Jukujikun. The word あさって means “the day after tomorrow”. When it came time to assign Kanji to this word, the following 3 were chosen:

明 meaning “tomorrow” 後 meaning “after” 日 meaning “day”

You can reasonably see how this combination of Kanji can come to mean “the day after tomorrow”. The thing is, the actual way you read those Kanji are nowhere close to あさって!They were chosen because of their meanings and not their readings. It’s almost the reverse of ateji. 2 more examples are:

今日 is read as きょう but 今 is not きょ and 日 is not う

下手 is read as へた but 下 is not へ and 手 is not た

When it comes to jukujikun, because the furigana can’t be separated between the characters, it will appear either in the middle of the characters or stretched across them.

As for my Kanji, because the characters sound out ある, 亜琉 is ateji. However, I also chose 2 Kanji with meanings that I liked. 亜 means “Asia” and 琉 means “gem” so I chose my name to mean “gem of Asia”.

2) Okurigana

Now, let’s talk about okurigana. It is similar to furigana, except that it only appears next to Kanji. Okurigana is thought of as “hanging off of” Kanji characters.

The okurigana tells you how you should read the 食 Kanji. In this particular example, both words mean “to eat” so mixing them up is not the end of the world (depending on who you are talking with!). Other times, however, the meanings will be drastically different so okurigana is a vital part of Japanese.

Adjectives and Verbs

Most of the time, you’ll find okurigana with adjective and verb forms. This is because they have a core part (called the stem) that will not change, and an ending that changes to add different shades of nuance to the core meaning. Think of the difference between “kick”, “kicks”, and “kicked” in English.

Notice that sometimes the adjective or verb stem doesn’t overlap with the okurigana (Type 1). Other times, part of the stem is included in the okurigana (Type 2). The main thing to remember is, the okurigana is the Hiragana after the Kanji.

Another time you will see okurigana is with compound verbs. This is where two verbs are combined into one. In these cases, there will be okurigana both between and after Kanji characters. Examples are:

思い出す, which means “to remember” 食べ残す, which means “to leave food half-eaten”

Nouns

Most of the time, nouns are made up of only Kanji. However, there are some occasions where they will have okurigana. Most times, they will end in a character from the い VSG.

This is because they actually come from verbs! Here are some examples:

匂い (from 匂う) 好き (from 好く) ーーーーーーーーーー 乗り場 (from 乗る) 立ち飲み (from both 立つ and 飲む)

Other times, they aren’t derived from verbs, they are just simply nouns:

勢い, which means “force, power” 後ろ, which means “behind, rear” 全て, which means “all, everything” 情け, which means “pity, sympathy” 斜め, which means “diagonal, slanted”

Same Kanji, Different Okurigana

The function of okurigana is to point you in the right direction of how to pronounce a given Kanji. There would be no reason for this if each Kanji had only 1 possible reading. As it turns out, a single Kanji can have many different ways to say it. Here are some examples:

As you can see, depending on the okurigana, 汚 can be read as きたな or as よご. On the other hand, the Kanji 広 is read as ひろ in all 5 of those words! For this reason, I would recommend learning Kanji like 広 early in your studies. It will be much easier for you to remember a Kanji with only 1 or 2 readings than a Kanji with many different readings.

Same Kanji, Same Okurigana

It’s rare, but there are times when the okurigana unfortunately won’t tell you decisively how to pronounce the Kanji. Here is an example:

As you can see (with the help of the furigana!) BOTH the Kanji and the okurigana are the same, making them different words but homographs. If it weren’t for the furigana, you might not know which reading of the kanji to use. In this situation, they both mean “to open” but the way and the kind of opening is different. Japanese often separates very similar meanings by using different Kanji. In English, we just take it for granted that you can open your eyes and you can also open a door. In Japanese, they are two different kinds of actions, and so different Kanji are used. (It won’t matter when you speak, but when you write or type, it would be good to be aware of the difference.) In these kinds of cases, you will have to rely on either context or on furigana to know which reading is correct.

Conclusion

As you can see, both furigana and okurigana will help you when it comes to reading Kanji. Sometimes you will have both, other times there will only be okurigana. Later on in the Kanji section, we will take a look at other ways to help you guess a Kanji’s reading. Until then, good luck with your Japanese journey!

And with that, you are finished with the Hiragana section. Congrats!

Rice & Peace,

– 亜琉 (アル)

👋🏾

#learn hiragana#hiragana#japanese language#learn japanese#japanese#study kanji#kanji#learn kanji#japanese studyblr#japanese langblr#learning japanese#japanese kanji#study blr#language blr#日本語の勉強#日本語#日本語勉強#langblr#漢字#isshonihongo

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

tagged by @aro-langblr! タッグしてくれてありがとう!!

🌸 last song: the man who sees tomorrow by uwade

🌸 last show: season 6 of the uk taskmaster

🌸 currently watching: x files rewatch with my bf (who hasn’t seen it) (i’m curating it so we just get the good ones lol)

🌸 currently reading: the kingdoms by natasha pulley

tagging: @onigiriforears @chouhatsumimi @isshonihongo @tokidokitokyo and genuinely anyone else who wants to!!

#this was actually slightly difficult bc i hardly ever watch tv#the taskmaster and txf things are not exactly ''recent'' lol#relatively recent#but i AM actively reading the kingdoms#love natasha pulley#sasha.txt#not langblr

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

JLPT N5 - あげる

At its simplest, あげる means “to give”. At the N5 level, it’s used for giving physical things such as presents, money, water (to plants), food (to pets), etc. There is another way it can be used, but that is for a later JLPT level. For now, let’s get into ONE of the ways you can talk about giving in Japanese.

First, here is the vocabulary for this post.

【The Grammar of あげる】

Basically there are 4 parts to every あげる sentence that you should be thinking about. The first 3 are marked with particles and the last part is the verb.

Here is an example sentence:

① 【けんじは】【トムに】【腕時計を】あげた。

= As for Kenji, to Tom, a watch gave

= Kenji gave Tom a watch.

In a sentence like #1 it’s easy to see the 3 parts clearly marked with particles and then the verb at the end. Unfortunately you WILL NOT always see simple sentences like this, so let’s look at each part one by one, along with the cultural context behind あげる.

【The Giver】

Most of the time, the giver will be marked by the は (or sometimes the が) particle. This is because あげる sets up the action of giving from the giver’s perspective.

Sometimes, it is obvious who the giver is, so that phrase can be completely left out of the sentence.

② 【会社の人たちに】【お土産を】あげると思う。

= to the people at (my) company, souvenirs will give I think

= I think I’m going to give the people at my company souvenirs.

In this sentence it would be clear that the speaker is the giver. Therefore it’s not necessary to include a 私は phrase.

【The Relationship Between Giver and Receiver】

Before we move on, let’s get into a very big cultural difference between Japan and English-speaking cultures. When you use あげる, you have to think about the relationship between the giver and the receiver. In English, this doesn’t affect the words we use, but in Japanese it is actually very important when it comes to word choice. Take a look at this image:

The green circle would include close friends, family, your lover, etc. Pets and plants would also fall into this circle. Outside of the green circle are strangers, teachers, professors and depending on your job, your customers. This is because showing respect is directly connected to setting up a kind of psychological distance. You have to work hard and gain trust before you are moved into the green circle.

Some people, like coworkers and bosses, may be inside the green circle in some situations, but outside of it in other situations! A common example is when you go out drinking with coworkers. As the alcohol flows throughout the night you’ll notice that psychological space slowly disappearing - that is until the next day at work. They might act like the person you drank with was a COMPLETELY different person!

This way of thinking is called うちそと, and can be a very difficult part of Japanese culture for many foreigners. Here’s the thing: the culture of うちそと extends to the concept of giving as well.

【Giving Culture and あげる】

When it comes to giving, there are 4 situations where it’s appropriate to use the verb あげる:

① When you give something to someone inside your inner circle

② When you give something to anyone outside your inner circle

③ When someone in your inner circle gives something to someone outside your inner circle

④ When someone outside your inner circle gives something to another person outside your inner circle

Numbers 1-3 can be described as the act of giving while moving from a smaller circle to a bigger circle. Number 4 can be described as giving that doesn’t happen in your inner circle.

There are of course more possibilities when it comes to giving (and receiving). However, those situations won’t use the verb あげる!

【What Is Being Given】

In most sentences, whatever is being given is very simply marked with the を particle. However, there are times when the を particle or the positioning of what is being given will change. Take a look at these three example sentences:

Example 3a is the “default version”. The doll is marked with the を particle so we immediately know that it will be given to someone (the section manager’s wife).

For example 3b I want you to imagine that you are in a souvenir shop. You’ve bought a couple of things already, but you haven‘t decided which gifts will go to whom. All of a sudden, you see a doll that catches your eye. You immediately think to yourself, “that doll is perfect for the section manager’s wife”. Putting the item being given (that is, the doll) at the head of the sentence shows that 1) you are putting the focus of your sentence on that item and 2) there is a kind of impulsiveness to the giving. It’s kind of an instant decision.

Compare that with example 3c. Now I want you to imagine that you are in your house. You bought a bunch of dolls but you haven’t decided which one will go to whom. You pick up one of them and after some thought you say, “Ok I’ll give THIS one to the section manager’s wife.” Marking the doll with は serves to emphasize that there are several dolls, but you are highlighting one of them for a specific reason. It also shows that it WAS NOT an instant decision; some thought went into your decision.

This kind of distinction takes a really long time to understand and really “feel” but I hope that by explaining it to you now, it might stay with you somewhere deep inside your mind. You might even experiment with using sentences like 3b and 3c and surprise your Japanese friends!

【Alternative Verbs】

Lastly, let’s talk about your choice of verbs. You can actually adjust the level of “closeness” that the reader / listener feels by changing the verb that you use! あげる, あげた, あげます, あげました, etc. is used for a “default” level of closeness.

However, if the receiver is someone in a higher social position (for example a professor, a doctor, a boss, a politician, etc.) you would instead use the similar verb さしあげる. This verb actually serves to humble yourself - and thus elevates the listener / reader.

④ 【この本は】ただでさしあげます。

= as for this book, for nothing will give

= I will give you this book for free.

From this sentence you can tell that the giver and the receiver are on different levels, socially. (This is a little different than うちそと.) The listener will feel an elevated level respect simply by hearing the さしあげる verb.

On the other hand, if the receiver is someone VERY close to you, you can show that closeness by using the verb やる instead of あげる. やる is often used with pets and plants.

⑤ 【彼女は】【犬に】【えさを】やるのを忘れた。

= as for her, to (her) dog food giving forgot

= She forgot to give her dog food.

As it turns out, this is why I keep on saying “what is given” instead of “a present” or “a gift”. Giving water to plants or food to pets is not a present or a gift.

Here is a visual representation of the 3 different verbs that you can use when talking about giving (from the giver’s perspective):

Here is 1 last example:

= as for apples I give to you, there are none

= I don’t have any apples to give you.

As you can see in #6, it’s possible to state a giver, a receiver and then あげる in order to describe what is being given. Once you do that, you will then have a topic which you can then go on to make a comment about!

【Conclusion】

So there you have it! あげる and its related verbs (さしあげる and やる) all express the idea of giving from the giver’s perspective. However, you have to keep the Japanese concept of うちそと in mind. Later we’ll talk about giving but from the receiver’s perspective. Stay tuned!

Rice & Peace!

-AL (アル)

👋🏾

#日本語#japanese studyblr#japanese grammar#japanese language#isshonihongo#japanese culture#あげる#jlptn5#jlpt#japanese#learn japanese#japanese lesson#japanese study#studying japanese#japaneselessons#learnjapanese#japanese langblr#japanese vocab#japanese vocabulary#language#languages#language study#language studyblr#language blr#日本語の勉強#にほんご

120 notes

·

View notes

Text

9.1) The Basics of the Receptive and Causative Forms

Hey everyone! In this post I’d like to go over some basics before we break down receptive and causative sentences.

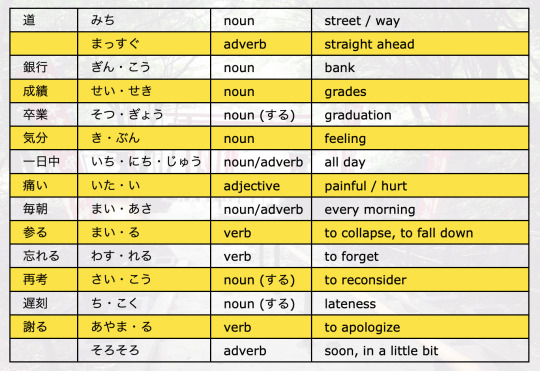

Here is your vocabulary, short and simple:

【The Endings】

First, let’s look at the endings:

It’s time to reveal something about these endings. These are not just endings. In actuality they are helping verbs! THAT is the reason why the final -る can be inflected.

As a reminder, here is how we can inflect that final る:

-る ➡️ -ない、-たい、-ます、-れば、-た、-て

Notice that we attach those endings directly to the verb stems. Does that remind you of anything?? Yes, れる、せる、られる and させる are all Ichidan verbs!

On top of that, remember that -ない、-たい and -ます can further inflect (because they are ALSO helping verbs!) giving you lots and lots of possibilities. This info will come in handy a bit later.

【Receptive Sentences】

In the next post when we get to receptive sentences, there are 4 parts of each sentence that I want you to think about. Here is a visualization that will help:

As is always the case in Japanese, what comes at the end is super important so let’s “zoom in” and start by looking at the 2 end sections.

【The Internal and Received Actions】

Because れる / られる and せる / される are actually verbs, it’s important to recognize that every receptive sentence actually contains 2 actions going on simultaneously. There is the action of “receiving” and there is an “internal action”. Let’s look at some examples:

① 褒められた

When you see this at the end of a receptive sentence, in your mind you can break this word down into two different actions - the action that was “received” and the “internal” action. The two parts are:

られた = received 褒め (to praise) is the internal action = was praised

In this case, once you figure out the actions, you only need to figure out who received the praising and who did the praising.

Here’s another example:

② 買われました

Let’s break down example 2:

れました = received (polite) 買わ (to buy) is the internal action = was bought (polite)

Because this is a Godan verb, the stem of the helping verb is れ. That won’t change. However the ending of the helping verb CAN change, and in this case it’s ました. Does it all make sense?

One more example:

③ 尊敬されたい

In this case, we have a する noun. No problem!

れたい = wants to receive 尊敬さ (to respect) is the internal action = wants to be respected

Now, is there anything you notice about those internal actions!?

For Ichidan verbs, する and 来る, the internal actions are just the verb stems! For Godan verbs, the internal action will always be the stem + its あ sound adapter.

The れる and られる verbs might have different endings too, but we already know the possibilities so it’s no problem. Now it should be much much easier to understand what is going on in all receptive sentences!

【Causative Sentences】

Causative sentences express the idea of either forcing or allowing an action to happen. These sentences basically have the same things going on as receptive sentences, except for the helping verbs at the end.

Whether the action was forced or allowed to happen, the end result is that the topic or subject “caused” the action. This is where the name causative comes from. Let’s look at some examples:

④ 食べさせた させた = forced or allowed to 食べ (to eat) is the internal action = allowed to / made to eat

When we get to the post on the causative form we will see how you know if it’s the “forced to” or the “allowed to” interpretation.

Here’s one more example:

⑤ アパートに入れさせなかった させなかった = didn’t force or allow to アパートに入れ (entering the apartment) is the internal action = was not let into the apartment

In example 5 it’s unlikely that someone was not forced to go into an apartment, so we go with the “not allowed to” interpretation.

【The Particles】

The particles in receptive and causative sentences will be very important. は、が、に、を and から will all be working together in harmony to express certain nuances. We’ll talk more about this in detail in the respective posts.

【Conclusion】

Well there you have it! Receptive and causative sentences were very hard for me to understand when I started studying Japanese. They still trip me up at times, but it helps to have this baseline of knowledge.

Now I believe that you are ready to look at full receptive and causative sentences. See you next post!

Rice & Peace,

– AL (アル)

👋🏾

#japanese verbs#japanese grammar#japanese receptive form#learning japanese#learn japanese#japanese studyblr#studyblr#japanese language#language#langblr#日本語の勉強#日本語#日本語勉強#にほんご#isshonihongo

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

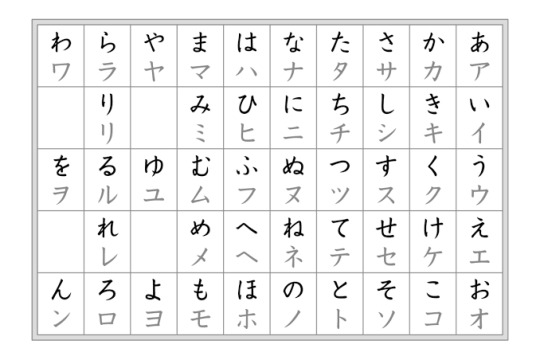

The Basic 46

This may be your very first page on your road to learning Hiragana! Either way, welcome!

There are 46 basic Hiragana characters. 6 of them are represented by a single English letter, while 3 of them are represented by three letters. The remaining 37 are all represented by two characters.

【Romaji】

First let’s talk about Romaji. You may have heard that Japanese has 3 sets of characters to express the language – Hiragana, Katakana, and Kanji. While that is true, there is a fourth set of characters and that is Romaji!

If you see the word “sake” you automatically read it as a word that rhymes with “take” and means “for the benefit of someone or something”. However, this is the English reading of the word. If you look at that word as Romaji, it is pronounced as “sah-keh” and it means Japanese alcohol.

Romaji is not English. It is an attempt at writing Japanese words with the English alphabet. There are sounds in each language that are not in the other, so relying on Romaji for too long is not a good idea. It is really only useful when you are beginning to learn Hiragana (and maybe 1 or 2 instances after that).

【Order】

Just like how we have something called “alphabetical order”, there is also an order to Hiragana (and katakana as well). To remember the order, there are several mnemonics that people use but the one I’ve always used is:

Kana Signs, Think Now How Many You Really Want

Keep in mind that these are only for the consonant sounds. And with that, now let’s look at those 46 characters!

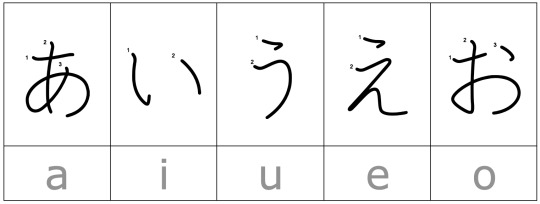

【The Vowel Group (あいうえお)】

These 5 characters are the vowels of Japanese. While English (depending on where you are from) can have anywhere from 24 to 27 different vowel sounds, the GOOD NEWS is that Japanese only has these 5!

【The K Sound Group (かきくけこ)】

At this point we need to be aware of a big difference between Japanese and English. If I asked you to break down the sounds of the word “kid”, you would tell me the 3 individual sounds for each letter. But in Japanese, the ”k” and “i” sounds MUST go together. The majority of Japanese hiragana characters are made up of a consonant-vowel pair.

This is why almost all of our remaining hiragana characters need either two or three English letters. The K Sound Group 2 is simply the consonant “k” sound and each of the 5 vowel sounds.

【The S Sound Group (さしすせそ)】

Our next group is made up of the consonant “s” sound and each of the 5 vowel sounds. However, in this group we have our first irregular character!

According to the pattern so far, you would think that the し character would be pronounced “si”, as in the Spanish word for “yes”. In actuality, it’s pronounced “shi” like the English word “she”. This is something to take a mental note of.

【The T Sound Group (たちつてと)】

The next group is mostly made up of consonant “t” sound and each of the 5 vowel sounds. This time, we have two irregular characters! Instead of sounding like the English word “tea”, the character ち sounds like the second syllable of the English word “catchy”.

Unfortunately, the character つ doesn’t have any equivalent sound in English. Instead of sounding like the Spanish word for you (tu), the closest we can get is trying to make the “t” sound while saying the name “Sue”! This character took me a bit of practice and a lot of time to master.

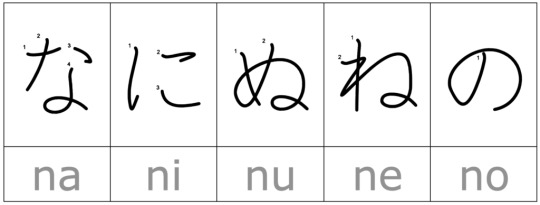

【The N Sound Group (なにぬねの)】

Good news: The next group doesn’t have any irregular characters, so it is pretty straightforward!

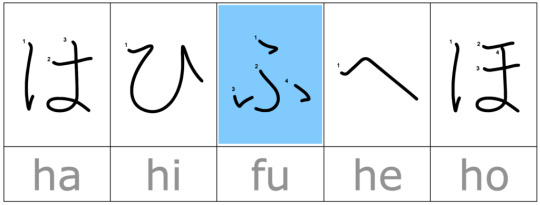

【The H Sound Group (はひふへほ)】

The H Sound Group has one irregular character. You might be tempted to think that ふ is pronounced as “hu”. If you look at the English representation, you might think that it’s pronounced as the first part of the word “fool”. In actuality it is pronounced somewhere in between! Just like つ, this character took me some time to get right.

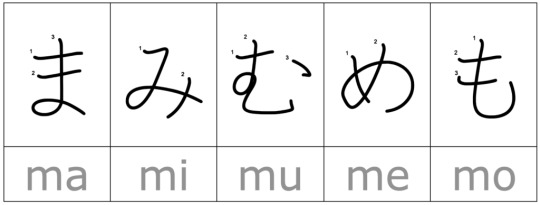

【The M Sound Group (まみむめも)】

This group is also pretty straightforward. No irregular pronunciations here!

【The Y Sound Group (やゆよ)】

You’ll notice that this group only has three characters. There used to be characters for the sounds “yi” and “ye” but they dropped out of modern use.

Also, these 3 characters are very important for making another set of sounds. We’ll get into that in a later post.

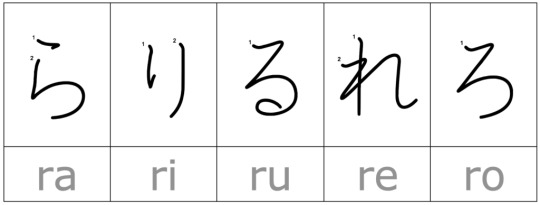

【The R Sound Group (らりるれろ)】

This group appears to be simply the 5 vowel sounds added to the consonant “r” sound, however it isn’t that simple.

As you may or may not know, Japanese people have a very hard time pronouncing and differentiating between the English “r” and “l” sound. The reason is that they don’t have those sounds in Japanese. Unfortunately that also means that these 5 characters are not easy for native English speakers to pronounce. Each character’s pronunciation is actually somewhere between an “r” and an “l” sound. These characters took me the longest time to master (especially in long words!)

【The W Sound Group (わを)】

This group only has 2 characters. The thing of note here is that を sounds almost identical to the character お. を is only used as a particle, so it will never appear in the middle of a word. Also, when it’s used as a particle, you might be able to hear a slight pause after it. These kinds of tricks make it easy to figure out when you are hearing を and when you are hearing お.

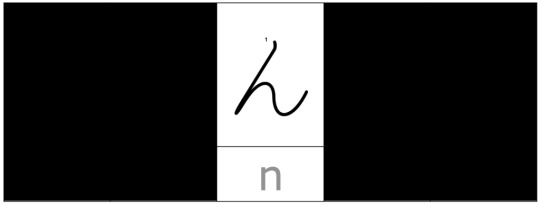

【ん】

The last basic character is ん. This is actually the only character that can be represented by a single consonant. It is mostly easy to tell when you are hearing this character, but there will be times when its pronunciation changes. More on that later.

【Conclusion】

So there you have it! Some people say that you can learn all 46 characters in 2 days, others say it should only take a week. It took me longer than that and so I say, take your time! There is no race to learn them so go at your own pace. Make sure that you have a good time while you practice; you’ll be more likely to remember the characters that way. Hiragana are important for learning Kanji down the line so it’s best to do it right the first time. Good luck!

#learn hiragana#hiragana#japanese#日本語#japanese studyblr#japanese language#learn japanese#日本語の勉強#language studyblr#にほんご#isshonihongo#language blr#languages#studying japanese#japanese study#studyblr

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

JLPT N5 - している [Part 2]

Hey everyone, welcome to Part 2 of talking about している. This N5 grammar point is very basic but also very important. Let’s get into it shall we!

But first, here is your vocabulary:

【English Helping Verbs】

As I mentioned in Part 1, the “して“ in している can stand for any verb in て form. Sometimes it is actually する, but most times it will be some other verb.

Ok great, but what is the いる part?? Take a look at the following English sentences:

① Traffic accidents often occur here.

② I am eating.

③ The window is open.

Two of these sentences have both a helping verb and a main verb. In #1, there is only a main verb, which is “occur”. In #2 the main verb is “eating” and the helping verb is “am”. In #3 the main verb is “open” and the helping verb is “is”. Notice that one of the main verbs has the -ing suffix while the other two don’t. Make a mental note of this for later. 😉

【The いる in している】

Japanese also has helping verbs. Allow me to introduce you to one of the most common ones: いる!

The いる helping verb* adds nuance to the main verb. But here’s the thing - there are different versions of いる!In the している Part 1 article, you actually saw what I call the いる of Repetition. This いる does not translate to the -ing form of our verbs in English. If you see よく起きている for example, you should think “often occur(s)”. This is similar to example #1 above.

Examples #2 and 3 are not actions of repetition. For them, we need the other いる, which I call the いる of State or Condition. This いる sometimes makes us use that -ing suffix in our English translations. So if you just see 食べている, by default it would mean “started eating and then stayed in that state for some period of time”. Instead of all that, in English we would simply say “is eating”. This is similar to example #2 above.

開く is a different type of verb than 食べる**. Because of this, the いる of State or Condition does not lead to us using the -ing form. In this case, something is open and stays in that state for some period of time. We don’t say “is opening”. Instead we just say “is open”. For verbs like 開く, their English translations won’t use that -ing form. Instead they will be like example #3 above.

The key to the している grammar point is understanding what kind of main verb you have, and then which helping verb いる you are reading/hearing!

【いる of State or Condition】

Here are some examples where the helping verb いる expresses a state or condition.

This is how you say example #3 in Japanese.

= Tom is currently in the Philippines.

Interestingly, you could also say the following:

⑥ トムはフィリピンに来ています。***

⑦ トムはフィリピンにいます。

#5, 6 and 7 all say that Tom is in the Philippines but the nuance is different in each of them!

#5 says that Tom went to the Philippines and stayed there. This means that the speaker is NOT in the Philippines. On the other hand, #6 says that Tom came to the Philippines and then stayed there, meaning that the speaker is also there. #7 simply says that Tom is in the Philippines. We don’t have any information about where the speaker is located.

= Mizuki is wearing a white skirt and hat.

#8 has several things that I want to point out: First is that the て form of a verb can mark the end of a comment. Example 8 has two comments of equal value. This is one version of a Japanese compound sentence.

The second thing is that the ending helping verb can actually apply to TWO DIFFERENT main verbs! Native speakers hear #8 and understand the verbs to be both はいています as well as かぶっています.

The last thing is that verbs connected to clothes are very interesting. When you attach the helping verb いる, they can sometimes express the state of wearing something. However, in some contexts they can instead express the action of putting something on. For the N5 level luckily you won’t have to distinguish between wearing and putting on clothing so no worries. It is good to keep this tidbit in the back of your mind for the future though.

【Conclusion】

So there you have it. Now you know that the している grammar point can express several situations. You could have:

・Repetition - there will be a word/phrase that indicates that the action happens repeatedly. The English translation won’t use the -ing form of a verb

・State or a Condition - there MAY or may not be a word/phrase indicating repetition. The main thing to focus on is whether the verb is an action verb or not. This will help you decide if you need -ing or not.

As always, keep your eyes and ears open for different kinds of examples and try to notice patterns. You can do it!

Rice & Peace,

– AL

👋🏾

*I purposely say “the helping verb いる“because there is also the regular いる verb. It’s the same with the “be”, “do” and “have” verbs in English. “Am” in “I am a teacher” plays a different role than the one in “I am eating.”

** 食べる is a transitive verb while 開く is an intransitive verb. Usually transitive verbs will translate to -ing and intransitive verbs won’t. Of course there are exceptions so keep an open mind.

*** When choosing between 来ている、行っている、and いる think about where the speaker is located as well as if you want to stress the movement of the subject.

#japanese#japanese studyblr#japanese language#japanese grammar#日本語#isshonihongo#jlpt n5#jlptn5#jlpt#nihongo#japanese langblr#learn japanese#japanese lesson#japanese study#studying japanese#japaneselessons#learnjapanese#language#languages#language study#language studyblr#language blr#日本語の勉強#にほんご

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

Small つ (Soku-on)

In the last post, we talked about how we can lengthen the 5 vowel sounds of Japanese. In this post, it’s time to look at what we can do to the consonant sounds. Let’s get into it!

What Does っ Do?

The small version of つ is called a soku-on, ちいさい 「っ」 , or just small つ. Here is a side-by-side comparison:

つ and っ

Putting the small つ in front of a consonant will double that consonant. To pronounce a doubled consonant, you very briefly stop the airflow in the space between your vocal cords. This space is called the glottis, and so the sound is called a glottal stop. Most of the time, small つ tells you to make a glottal stop.

Now, you might think that with the exception of あ、い、う、え、and お, you can use soku-on to double any other hiragana character… Luckily for you, that’s not how it works!

As it turns out, small つ can only come before characters in the K, S, T and P sound groups.

The K Sound Group

For these 8 situations, the soku-on simply tells you to make a glottal stop. The same characters with a soku-on and without a soku-on will make completely different words. Here are some examples:

みか is a woman’s name but みっか means “three days” or “the third day of a month”.

ゆっくり means “at your own pace” but ゆくり is not a word.

The S Sound Group

These 8 situations are pronounced a little differently. They are made not with a glottal stop, but by elongating the “s” sound.

いっしょ means “together” but いしょ means “a will” or “a note left by someone who has died”

The name of this blog is いっしょにほんご when you write it in Hiragana.

The T Sound Group

These 8 characters with a soku-on are pronounced with a glottal stop.

The super popular digital Tamagotchi pets are an example of using そくおん. You would spell it as たまごっち in Hiragana.

くっつく means “to stick together” but くつく is not a word.

The P Sound Group

Finally we have the regular P Sound Group.

いっぱい = one cup / bowl of something しっぱい = failure, mistake, blunder しゅっぱつ = departure, leaving やっぱり = as expected, it makes sense (that) りっぱ = splendidness, being fine, handsomeness いっぽう = one way (out of two) いっぽん = one long cylindrical thing にっぽん = a more formal way of saying Japan

An Ending っ

Sometimes you will see small つ at the end of a word or a sentence. This is just a way for the speaker or writer to express emotions (usually anger, surprise, or sadness). You may see small つ used together with long vowel sounds like below:

Just keep in mind that these are all basically pronounced the same so the difference is mainly when reading them. Because you have the ability to use / mix and match long vowel sounds, ちょうおんぷ and the small つ, it gives you a lot more flexibility to express emotions through text.

The Character Before っ

Let’s take a look at the word がっこう. It means “school”. We’ve been focusing on the small つ and the character after it.

っこ ➡️ kko

But now I’d like to focus on the small つ and the character before it.

がっ

We will deep-dive into this in the Kanji section, but it turns out that many times, the small つ actually means that there was a sound change!

For がっこう, there is actually a “hidden character” (く) under the small つ!Crazy stuff!

Just for your own curiosity, when you learn new words with the small つ, look them up in a dictionary and see how many times there is a hidden character under the small つ. It’s not 100% of the time, but you might be surprised at how often it happens.

Conclusion

And there you have it! The soku-on or small つ can completely change the meaning and the pronunciation of words. In my experience, getting used to hearing and pronouncing words with small つ was easier than words with long vowels. But with time, you’ll get the hang of both concepts. Good luck!

Rice & Peace,

– AL (アル)

👋🏾

#hiragana#learn hiragana#isshonihongo#japanese#language studyblr#language blr#study blr#にほんご#日本語の勉強#日本語#日本語勉強#japanese language#langblr#learn japanese#learning japanese

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Five More Sound Groups

After you learn the basic 46 Hiragana characters, the next set belong to 5 different sound groups.

First, there are 20 characters that change their pronunciation by adding a small mark to them. The mark looks like a quotation mark and is called a dakuten.

1) The G Sound Group

These sounds are completely regular. Just combine the “g” sound with the 5 vowel sounds of Japanese - あ、い、う、え and お.

Here is a practice game for the G Sound Group.

2) The Z Sound Group

For these 5 sounds, there is only 1 irregular pronunciation. Instead of “zi” the already-irregular し becomes “ji”. Other than that, you just combine the “z” sound with the あ、う、え and お sounds.

Here is a practice game for the Z Sound Group.

3) The D Sound Group

In this sound group, the already-irregular ち and つ become “ji” and “zu”. Other than that we have the “d” sound combined with the あ、え and お sounds.

Notice that instead of “di”, the ぢ character is pronounced as “ji” and instead of “dsu” the づ is pronounced as “zu”. They are pronounced exactly the same as じ and ず in most parts of Japan, though historically, they had different pronunciations. See what Wikipedia has to say about these characters.

Here is a practice game for the D Sound Group.

4) The B Sound Group

Good news! This group is completely regular. Just combine the “b” sound with あ、い、う、え and お.

Here is a practice game for the B Sound Group.

5) The P Sound Group

For these last 5 characters, things are slightly different. Instead of a dakuten mark, these characters have what looks like the degree symbol next to them. This mark is called a han-dakuten. These characters are just the “p” sound combined with あ、い、う、え and お.

Here is a practice game for the P Sound Group.

Sorting the Characters

Lastly, we should talk about character order. How would you look up these characters in a dictionary or on a website? There are 3 different ways that you might find them sorted.

The first possibility is that these 25 characters will be separated from the basic 46 Hiragana characters. That is what I’ve done here. However, this is very rare. For Japanese-learners, this is a useful way to sort the characters, but you won’t really find this grouping out in the wild very often.

Most of the time, these characters will not be separated on their own. That is to say, they will be grouped together with their regular Hiragana counterparts. (か and が will be together, as will き and ぎ and so on.) The question is, will the dakuten and han-dakuten characters appear after or mixed together with the regular characters?

In the following picture, there is no separation. Several areas of Tōkyō are listed. An area called ぎんざ (銀座) is listed in the か row. There is no separate が row. Notice that it comes before an area called きば (木場).

On the other hand, the main dictionary that I use sorts words in a different way. This time, there is a kind of separation.

The か section still contains words that start with が, but they appear at the end. THEN it moves on to the き section. Here is a picture:

Conclusion

If you’d like an interesting mnemonic to remember these characters, here you go:

Giant Zebras Dance Boldly in the Park!

Do with that what you will 😂

Congrats, you now know a whopping 71 Hiragana characters! There are only a few more left before you know every character. You’re almost there! See you next post.

Rice & Peace,

– AL (アル)

👋🏾

#hiragana#learn hiragana#isshonihongo#learning japanese#learn japanese#日本語の勉強#日本語#日本語勉強#japanese language#japanese studyblr#langblr#japanese#japanese langblr#japanese lesson#language studyblr#にほんご#japanese study#language study#studying japanese#japaneselessons#language blr#studyblr#study blr#learnjapanese

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

JLPT N5 - している [Part 1]

している is a grammar point that is very very important in Japanese. The “して” part represents a verb in the て form. The “いる” part is the verb いる, which will change to different forms (for example います、る or ます).

している actually appears in several levels of the JLPTs - from N5 all the way to N2! As for the N5 level, there are 2 main ways that you will see it used. In this post let’s look at one of them!

First, here is your vocabulary.

【Repeated Actions】

First let’s look at how している is used with repeated actions. These actions are mostly physical.

= I climb Mt. Fuji every year.

Notice the two highlighted words, 毎年 and 登って. If 毎年 weren’t there you would almost always translate 登っています as “am climbing”. However, because 毎年 expresses repetition, it forces us to translate 登っています as “climb”.

= Traffic accidents happen on this street often.

起きる is a verb that can mean “to wake up” or “to occur”. If sentence #2 didn’t have the word よく it would be understandable to translate 起きています as “are occurring”. However because of the よくwe understand that there is repetition and so we go with the “occur” translation instead.

= Well you see, Dad has been going to China for work once a month since last year.

This time the word / phrase that expresses repetition is 毎月1回 meaning “once a month”. This tells us that 行ってる is “goes” instead of “is going”. Also, the い in the helping verb いる can be dropped, making 行ってる a more casual way of saying 行っている. It also works for います so that 行ってます is more casual than saying 行っています。

Finally, take a look at the nuance section. This んです is actually a different JLPT grammar point. The gist is that it’s used when you want to answer a question with extra details that you think the listener/reader wants to know. The ん is a shortened version of the particle の.

【Occupation or Social Position】

している is also used to talk about someone’s occupation or social position.

= Taiki teaches Japanese at a Thai university.

There is no period of repetition stated outright, but we understand that teaching is a job that you do over and over. Thus, you should use 教えています instead of 教えます。

= Aya is a trading company manager.

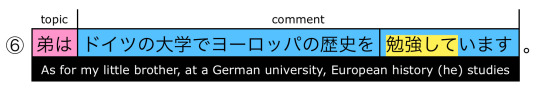

In this case, the しています simply means “is” or “has the position of”.

= My little brother studies European history at a German university.

This last example is a good one to remember. Most times, if you say 勉強しています it will mean “currently studying”. However when it comes to being a student, the translation shifts to “studies (for an extended period of time)”. Actions that can be interpreted either way (like studying) will sometimes have time words / phrases like 今 (now) or 2、3時間 (for a few hours). That tells you that it is an action in progress. Other than those kinds of phrases, usually the meaning will be repetitive.

【Conclusion】

So there you have it! The first している is associated with repeated actions, occupations, or positions in society or work. It’s fairly easy to figure out if the sentence is talking about an occupation or a position. For repeated actions, the key is to look for words / phrases that express repetition and remember that they cause you to use the している version of your verb. With that, you should be fine!

Rice & Peace,

– AL

👋🏾

#japanese#japanese studyblr#japanese grammar#japanese language#日本語#isshonihongo#jlpt#jlpt n5#一緒日本語#している

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pair Characters (Yō-on)

Hello and welcome back 😊

I have good news for you! With the 71 Hiragana characters you’ve learned, there are no other new character shapes that you need to learn!

However, there are 3 more groups of sounds that will be represented by character pairs. Let’s look at what sounds they make and how they are written.

Small (Yō-on) Characters

In our last post, we talked about Vowel Sound Groups. In this post we will need 12 characters from the い VSG:

Disregarding the い, we will be adding a small version of the Y Sound Group to each character. These miniature versions are called Yō-on, which means “contracted” or “distorted” sounds. For comparison, here are the Y Sound Group characters and the Yō-on characters side-by-side:

やゆよ、ゃゅょ

By the way, on a keyboard if you want to type those small Hiragana characters, you type the letter “x” followed by one of the three characters. (Type “xya” to get ゃ, etc.).*

The ゃ Sound Group

As you can see, adding the ゃ character to each of the 12 sounds in the い VSG results in the や Sound Group. With the exception of しゃ, ちゃ, じゃ and ぢゃ, all of those characters have “ya” in their pronunciations.

In modern Japanese, (especially in the Tokyo area) if you hear the sound “ja” you can be fairly sure that it will be written as じゃ. ぢゃ is rarely if ever used.

The ゅ Sound Group

The next group of sounds are formed by adding the ゅ character. Again, you will probably never see the sound of “ju” represented by ぢゃ. You will see it as じゅ.

The ょ Sound Group

Finally, we have the sounds formed by adding the ょ character. Just like with ぢゃ and ぢゅ, if you hear the sound “jo” it will almost always be represented by じょ instead of ぢょ.

Different Sounds and Words

An important point to highlight is that ゃ,ゅ and ょ make completely different sounds than や,ゆ and よ. Technically ゃ,ゅ and ょ don’t make any sound by themselves. The sound is completely dependent on the (regular) character that they are paired with.

This means that しゃ is a VERY different sound compared to しや. You have to be careful because you might be saying a completely different word.

しや = field of vision, one’s outlook しゃ = 1) company, 2) vehicle, 3) hut

If written in Kanji, しや is one word with 2 Kanji characters. However, しゃ can be written in many ways, and each different meaning has a different single-Kanji representation. Seeing and associating words with Kanji will help you to separate them in your head.

The ”NY” Problem

Now, as a native New Yorker, I have to say that this section is not about a problem with New York! This is actually a problem with writing words in Romaji. Look at these 4 Japanese words:

konya, honyaku, onyomi, kunyomi

Let’s take those first 2 words, konya and honyaku. konya means “this evening” or “tonight”. Honyaku means “the Japanese translation of a word.” The problem though, is that “nya” combination of letters. If we were to write those words in Hiragana, should it be “にゃ” or “んや”??

In order to get around this problem, we need to use an apostrophe to indicate whether you need 1 or 2 Hiragana characters. If there is an apostrophe after the “n”, it means you need the ん character. If there is no apostrophe, you will have either the にゃ、にゅ or にょ characters.**

Of course, as your Japanese improves, you’ll see those words written in Kanji. Through studying Kanji, you’ll get a much better sense of how Japanese words are separated.

Conclusion

There you have it! Now you’re one step closer to mastering Hiragana! There’s no shortage of reading and writing practice for Hiragana out there. Have fun and take pride in the fact that you’ve made it this far.

Next post we’ll look at long vowel sounds. Until then I’ll leave you with the full version of my handy Hiragana chart! Practice until you know every character without needing Romaji. Good luck!

Rice & Peace,

– AL (アル)

👋🏾

*There are 5 more small versions of Hiragana characters that can be written. We will see them in the next post.

**The correct way to write those 4 words is: konya, honyaku, on’yomi, and kun’yomi. We’ll talk about on’yomi and kun’yomi in the Kanji section.

#learn hiragana#hiragana#isshonihongo#japanese language#japanese#studying japanese#japanese study#studyblr#language studyblr#language study#日本語#japanese studyblr#learn japanese#日本語の勉強#にほんご#japanese lesson#japanese langblr#japaneselessons#learning japanese#language blr#study blr

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hiragana Page

Hello everyone! Welcome to my page for the basics on Hiragana!

Hiragana are the gateway into Japanese. It all starts here. The posts below will help you get familiar with these basic Japanese characters. Enjoy!

① The Basic 46 ② Five More Sound Groups (Dakuten & Han-dakuten) ③ Vowel Sound Groups (VSGs) ④ Pair Characters (Yō-on)

⑤ Long Vowel Sounds (Chō-on) ⑥ Small つ (Soku-on) ⑦ Pronouncing ん (Hatsu-on)

⑧ Furigana & Okurigana

For matching practice activities, click here.

#learn hiragana#hiragana#isshonihongo#learning japanese#learn japanese#日本語の勉強#日本語#日本語勉強#langblr#japanese studyblr#japanese language#language blr#study blr#language studyblr#language study

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vowel Sound Groups

So far we’ve talked about 15 Hiragana sound groups and 71 characters in all! Here is a chart that you can use to review what you’ve learned:

If you look at that handy chart, you’ll notice that I went horizontally from right to left when I introduced each character.

However, in this post we’re going to switch it up. Let’s talk about what we see if we read that chart vertically instead of horizontally.

The あ Vowel Sound Group

The first group all end in the あ vowel sound. Some of these sounds will be very important when we talk about negation in verbs. They will also be important when we talk about receptive and causative sentences.

The い Vowel Sound Group

The next VSG will be very important when we talk about our last set of 36 Japanese sounds. They will also be important when using the polite forms of verbs and when you want to say that you want to do an action.

Keep in mind that ぢ is rarely used in modern Japanese words.

The う Vowel Sound Group

9 of the sounds in this group will be very important when we talk about Japanese verbs.

Just like ぢ, づ is not often used in modern Japanese words.

The え Vowel Sound Group

This group will be important when we talk about how you say you are able to do something, and also when you want to say ”if I do X, then Y”.

The お Vowel Sound Group

This final group is used when you want to say “let’s do 〜” and also when you talk to yourself about doing an action.

Conclusion

Grouping the characters by their ending vowel sounds will become very useful later on as we get into the grammar of Japanese. For now, it can be a useful way of reviewing and remembering the characters you’ve already learned. See you next post!

Rice & Peace,

– AL (アル)

👋🏾

#learn hiragana#hiragana#isshonihongo#japanese language#learning japanese#learn japanese#日本語の勉強#日本語#日本語勉強#japanese studyblr#langblr#japanese study#studyblr#studying japanese#japanese#language studyblr#にほんご#language study#japanese lesson#japanese langblr#japaneselessons#language blr#study blr

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hello everyone! I just wanted to give everyone a quick update!

For the past 2 years, being a full-time teacher in the Japanese system really was kicking my butt. This year though, I’ve reduced my workload so I hope to be able to post more often. Thank you so much for reading, liking, reblogging and being patient. I hope this blog helps in even a small way.

I made a Ko-fi account! If you are able, feel free to show your support. I truly appreciate it. See you next time!

Rice & Peace

👋🏾

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

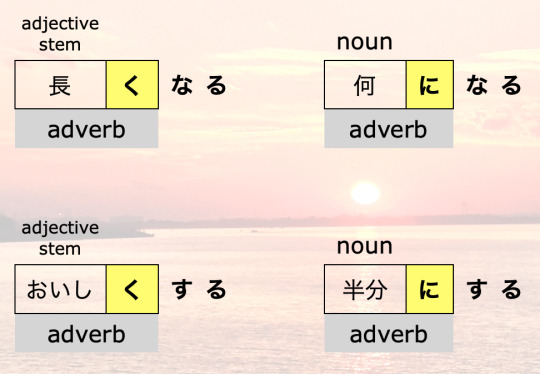

JLPT N5 - くなる and くする

This grammar point is very simple. You use くなる when the condition of something becomes a certain way by itself. On the other hand, くする is used when the condition of something is changed by an outside agent (either a person or a thing). In this post, let’s look at these two very basic constructions and how the Japanese works.

Here is your vocabulary:

【The Grammar】

The grammar is very simple. First, you take an adjective or a noun and change them to their adverbial forms. For example, the adjective 長い has an adverbial form of 長く. The noun ひま has an adverbial form of ひまに.

After you make the adverbial forms of the adjective or the noun, you just put it before either なる or する. That’s it!

We talked about the く connector in this post and about the adverbial に in this post.

I should point out that while this grammar point appears in most JLPT books and websites as くなる and くする, as you can see in the picture above, nouns don’t use く! For that reason, I choose to call this point adverb ✙ なる and adverb ✙ する.

【adverb + なる】

Here are some examples with なる:

① 熱が下がって、気分がだいぶ{よくなりました}。

=fever will go down and then feeling became considerably better

= My fever went down and then I felt much better.

② この仕事が終わったら、少し{ひまになる}と思います。

= when work finishes, a little bit, will become free, I think

= I think that when work finishes, I’ll have more time.

③ このごろ仕事が減って、前ほど{忙しくなくなった}。

= these days, work decreased and so as much as before, became not busy

= These days, I have less work and so I’m not as busy as before.

④ きみは{大人になったら}、{何になりたい}の。

= when you become an adult, what want to become

= When you grow up, what do you want to be (and explain)?

Some things to notice:

In example 1, the sense is that when the fever went down, the person’s mood got better by itself.

In example 2, the condition of having more free time arises naturally when work decreases. (ひま can have the connotation of having absolutely nothing to do and can be considered rude by some people. I use the word for myself sometimes, but I never seriously refer to other people as ひま.)

Concerning example 3, the negative form of 忙しい is with 忙しくない. If you want to make THAT into an adverb, it will become 忙しくなく. This was very difficult for me when I was just beginning Japanese.

Finally, Example 4 shows that the question word of 何 can be treated as a noun. This makes sense if you think of it as a placeholder for whatever answer the listener will give. Also, because the speaker uses the word きみ we know that the speaker and listener are close. It would make sense if it were a parent-child relationship. きみ is NOT used with people that you have just met or that you don’t know well!

【adverb + する】

Here are some examples with する:

⑤(父が子どもに)もっと部屋を{きれいにしなさい}。

= father to his child: a little bit more the room, make it clean

= Clean up your room a bit more.

⑥ このケーキ、ちょっと大きいから、{半分にして}ください。

= this cake, a bit big and so make it half please

= This cake is a bit (too) big so please cut it in half.

⑦ スカートを5センチぐらい{短かくして}ください。

= this skirt, about 5 centimeters make it short please

= Please shorten this skirt about 5 centimeters.

Notice that examples 5, 6 and 7 all include someone (other than the speaker) making a thing (a room, a cake, and a skirt) a different condition than the current one. This is when you will want to use adverb + する.

【Conclusion】

The grammar points of adverb ✙ なる and adverb ✙ する are pretty simple to understand. That is why they are considered Level N5. Adverb ✙ なる shows a person or a thing becoming a different condition by itself. Adverb ✙ する shows a person or a thing changing to a different condition by a different person or thing.

Thanks for reading, and see you next time!

Rice & Peace,

– AL (アル)

👋🏾

#japanese#japanese grammar#learn japanese#japanese language#japanese lesson#japanese study#japanese vocabulary#japanese vocab#studying Japanese#japaneselessons#learnjapanese#japanese studyblr#japanese langblr#JLPT#JLPT N5#jlptn5#にほんご#日本語#日本語の勉強#一緒日本語#language#languages#language study#language studyblr#language blr#IsshoNihongo

393 notes

·

View notes

Text

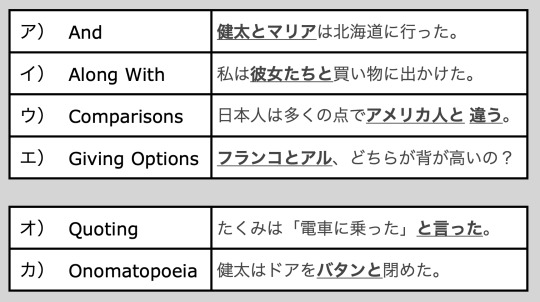

8.4) Conditional Forms (と)

The last conditional form we will talk about is the conditional と particle. First though, it’s important to distinguish between this usage and other usages of the と particle. Just like に and で, there are many ways you will see/hear the conditional と used!

Below are 6 sentences that use the と particle, but NOT the conditional と.

If you want to read about these uses, check out these posts I made about them:

【Examples ア-エ】

【Examples オ and カ】

Also, I already wrote a post about the conditional と particle that you can read here. In this post I’m going to be looking at conditional と in a different way. Here is your vocabulary:

【The Grammar of と】

The conditional と particle can attach to verbs, adjectives and noun-copula pairs (but only in the form of noun+だ).

【Did It Happen Or Not?】

When you look at sentences with the conditional と, there are two possibilities when it comes to the second clause:

If we think of this with English counterparts, here are two examples:

[Case1] When / If water reaches 100℃, it boils.

[Case2] When I walked in the room, the students stopped talking.

In case 1, the event in the first clause (water reaching 100℃) inevitably leads to the event in the second clause (it boiling). That is to say, the second clause hasn’t actually happened yet... but if the first clause happens, it will.

Compare that to case 2, where both events have already happened. This is a big difference between the two cases. Now, here are some Japanese examples:

①{この道をまっすぐ行くと}、{銀行があります}。

= when/if the/this street go straight, there will be a bank

= When/if you go straight down this street, there will be a bank.

②{成績が悪いと}、{学校を卒業できないよ}。

= when/if grades are bad, can’t graduate from school, you know

= When/if your grades are bad, you can’t graduate.

③{学校に行くと}{休みだった}。

= when go to school, it was rest

= When I went to school, it was closed.

【The Timing of と】

Another thing to think about when using the conditional と is the timing of the events. と gives the nuance that both happen almost at the same time.

④{天気がいいと}{気分がいい}。

= when/if the weather is good, feel good

= I feel good when/if the weather is good.

Example 4 is saying that the weather being good directly leads to the speaker also feeling good. The nuance of the timing is that as soon as or soon after the weather is good, the speaker feels good. Sometimes, this means that you can translate the と as “once”.

We will come back to this idea of timing when we compare the conditional forms. 😉

【When or If?】

In general, if the second clause is in past form, the English translation will use “when”.

Here are two more examples:

⑤ 一日中{パソコンを使うと}、{目が痛くなります}。

= all day when/if use a computer, eyes hurt

= When / If I use the computer all day, my eyes hurt.

⑥ 毎朝{起きると}{コーヒーを飲む}。

= every day when wake up, drink coffee

= Every day when I wake up, I drink coffee.

For example 5, there won’t be a difference if you think of the と as “if” or as “when”. However, there is a HUGE difference between “when I wake up” and “if I wake up”! This shows that the action or adjective in the first clause is the key to the English translation. Some words will naturally translate to “if”, and some words will naturally translate to “when”. Many words though, can use either and make sense.

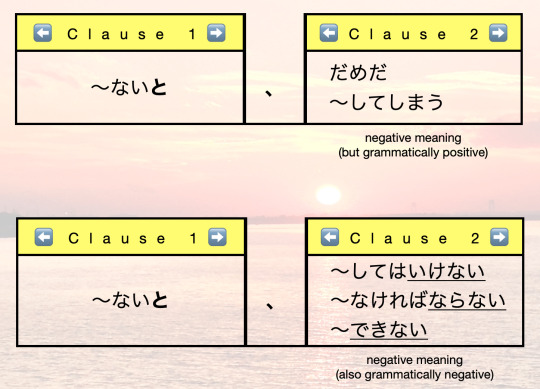

【〜ないと】

The last thing we should talk about is the “warning” usage of conditional と. Because the conditional と expresses a natural consequence or an inevitability, it is often attached to the negative form of a verb in order to warn the listener of some... negative consequence. An extension of this is indicating the speaker’s responsibility or duty to do something.

There are three kinds of clauses you will see / hear after a ないと clause: (1) a grammatically positive phrase with a negative meaning or (2) a grammatically negative phrase with a negative meaning. Here are some examples:

だめ simply means “it’s not good”.

〜してしまう has a nuance of something unexpected happening. For example if you use the verb 参る with しまう, you get 参ってしまう which means “unexpectedly collapse or fall down”.

〜してはいけない is a roundabout way of saying “don’t do 〜”. For example if you use the verb 忘れる in this construction you get 忘れてはいけない. This basically means “don’t forget”.

〜なければならない means “have to do 〜”. If you use the word 再考する in this construction, you will get 再考しなければならない。This means “have to reconsider”.

Finally, 〜できない means “can’t do 〜”

Here are some examples with Japanese sentences:

⑦{早く起きないと}{遅刻するよ}。

= in an early way, if don’t get up, will do lateness

= If I don’t get up early, I’ll be late!

⑧{アンに謝らないと}{いけない}。

= to Ann, if I don’t apologize, it won’t go/do

= I have to apologize to Ann.

Notice how clause 2 in example 7 is grammatically positive (遅刻する) but has a negative meaning. On the other hand, clause 2 in example 8 is negative (いけない) and also has a negative meaning. This is something you will see quite often after a ないと phrase.

The third possibility for what comes after a ないと clause is... nothing! Japanese often avoids being direct by simply not saying a phrase or a word. With ないと clauses, everyone knows that the following clause is something negative so it’s ok to just not say anything. The listener or reader can use their imagination to figure out the negative consequence(s). Here is an example:

⑨{そろそろ寝ないと}。

= well... soon if don’t sleep...

= Well... I need to sleep soon.

First off, we don’t actually know who the subject is in example 9 but we can assume that it is the speaker though. The speaker intentionally leaves off the second clause. We don’t actually know what will happen if he/she doesn’t sleep but because of the ないと, we know it won’t be good!

【Conclusion】

And that is what you should know about using the conditional と. I hope this post was helpful and informative. As always, if you have any questions, let me know!

The next post will be the last one in this conditional forms section, so look out for that. Good luck with your Japanese learning adventure!

Rice & Peace,

– AL (アル)

👋🏾

#japanese#japanese grammar#learn japanese#japanese language#japanese lesson#japanese study#japanese vocabulary#japanese vocab#studying Japanese#japanese particles#japaneselessons#japanese langblr#learnjapanese#japanese studyblr#japanese conjunctions#japanese conditionals#language#languages#language study#language studyblr#language blr#日本語#日本語の勉強#一緒日本語#IsshoNihongo

155 notes

·

View notes

Text

8.2) Conditional Forms (-たら)

Hey everyone! 👋🏾 Sorry I’ve been MIA for a few months. I moved up to full time at my high school this school year, so work has been kicking my butt. Anyway, here we go with a new post, just for you!

Last time we talked about the conditional なら and 4 ways to use it. In this post, let’s look at a different conditional form and when you might use / see it in everyday Japanese.

Here is your vocabulary:

【The Grammar】

Japanese has many helping verbs that add extra meaning to verbs and adjectives. One of these helping verbs is た, which shows that a verb is in past tense. Because た is a helping verb, it turns out that there are different forms you can use for different purposes*. たら is the conditional form of た!

In the same way that た can be attached to verbs and adjectives, so can たら. There is also a たら version of the copula for nouns. In addition, it can also attach to the negative forms of verbs, adjectives and nouns.

【What It Means】

A たら clause indicates that there is an event that needs to happen first in order for a second event to happen. This will translate to either “when”, “after” or “if” clauses in English, depending on the situation. Take a look at the following 3 English sentences:

Even though たら has 3 different interpretations, the timing of the events is always the same. The event of the たら clause (clause 1) will always happen before the second event (clause 2).

【たら = When】

Let’s look at situations when たら means “when”:

①{昨日、デパートへ行ったら}、{友達に会った}。

= yesterday when went to the department store, saw friend

= Yesterday when I went to the department store, I saw my friend.

②{試験が済んだら}{長期休暇をとるつもりだ}。

= when tests were completed, take long vacation plan exists

= When my tests are done, I plan to take a long vacation.

【たら = After】

Sometimes, たら translates instead to “after”

③{薬を飲んだら}、{頭痛が治った}。

= After medicine drank, headache was cured

= After I took some medicine, my headache went away.

④{食べたら}{宿題をし始める}。

= after ate, homework will start

= After I eat, I’ll start my homework.

Notice that the literal translation of the たら clause is past tense however it’s the tense of the second clause that determines the real translation. Example 3′s second clause is in past tense, so the first clause will also become past tense. In example 4, the second clause is not in past tense, so the translation is not in past tense either.

【たら = If】

The majority of the time though, たら translates to “if”.

⑤{雨が降ったら}、{タクシーで行きましょう}。

= If rain fell, by taxi let’s go

= If it rains, let’s take a taxi (there).

⑥{お母さんがお金をくれなかったら}{どうしよう}。

= if Mother didn’t give us money, what should do

= If Mother doesn’t give us money, what should we do?

⑦{もしよかったら}、{コーヒーでも入れてくれませんか}。

= if it was good, can I receive you making some coffee =

If it’s OK, can you make some coffee for me?

In order to clearly show the “if” meaning of たら、the adverb もし is often used at the beginning of the sentence. It also helps to soften the meaning of the sentence.

【Alternate Reality たら】

たら sometimes is used to talk about alternate realities. The nuance here is that either something didn’t happen or that if something didn’t happen the outcome would be very different.

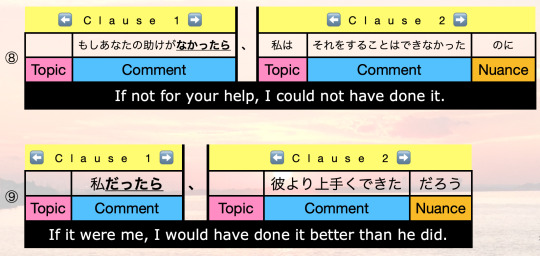

You can see that example 8, the speaker imagines a reality where he/she didn’t have the listener’s help in the first clause. Because the second comment is something that is not good (できなかった) this ends up showing appreciation. In example 9, the speaker imagines a reality where he/she did something. The comment says that it would have been better so this ends up expressing disappointment / annoyance.

In these kinds of sentences, the nuance section is very important because it will tell you if the sentence is expressing appreciation, regret, disappointment or just imagining a different timeline. Common sentence endings are のに (for regret) and だろう (for asserting a point).

【たら = How About If...?】

The final way that たら sentences are sometimes used is for suggestions.

⑩ もうちょっと塩味をきかせてみたら?

= if you added a little more salt (that might solve your problem)?

= You should add a little more salt.

As you can see, the nuance is that by doing what comes before たら, it might be a solution to whatever is the problem. In keeping with たら meaning “if”, you can think of this usage as “How about if...?”. But a more natural way to think of this is a suggestive “you should...”.

【The Second Clause】

Let’s end by talking a bit about the second clause. One thing to remember is that it has to be something that the speaker can’t control. In example 1, seeing a friend wasn’t something planned so this sentence sounds natural. If you replaced 友達に会った with 服を買った, it would sound strange because buying clothes is something that you can control.

Example 4 might seem like it goes against this rule. The truth is, because we can’t control the future, starting your homework is taken as intent and not as forecasting the future. Japanese is very weary of saying that something will happen if it’s not 100% guaranteed to happen.

【Conclusion】

So there you have it! I hope that now when you see たら tacked on to the end of words that you will have a better idea of what is going on. I hope that you also try using it in your daily conversation and see how your listener reacts. Smooth conversation means you did it right!

Next time, we’ll continue our look at conditional forms. See you then!

Rice & Peace,

– AL (アル)

👋🏾

* There are three forms of the た helping verb: (1) た (2) たら and (3) たろう.

たろう is rarely used but it asserts that something would have been the case. For example, “If he didn’t help me, I would have failed.” This is similar to the alternate reality section in this post.

#japanese#japanese grammar#learn japanese#japanese language#japanese lesson#japanese study#japanese vocabulary#japanese vocab#studying Japanese#japaneselessons#japanese langblr#learnjapanese#japanese studyblr#language#languages#language study#language studyblr#language blr#日本語#日本語の勉強#一緒日本語#IsshoNihongo#japanese conditionals

208 notes

·

View notes