#It’s not about discovering authorial genius it is about

Text

My problem is that I cannot see wobbly loosely goosey world building that has fun bits without wanting to try and take them and rearrange them in a way that makes sense.

The result of this is that I CANNOT stop thinking about Foodcourtia and how this presumably Irken-controlled station functions in this genocidal space empire when most of the customers seem to be other aliens. I am trying to figure out how I can make it align with the “superior alien race” rhetoric that non-Irkens can go to space Burger King and essentially hassle the Irkens working there for gross hot dogs. All the whole knowing full well the authorial intent started and ended at “heehoo Zim works at Space McDonald’s”.

#clefairy squeaks#It’s not about discovering authorial genius it is about#Taking this polly pocket set and organising it in a way that makes sense to me#Invader Zim is a Space Barbie set and I am a 9 year old girl trying to organise my dollies#I can only assume there’s SOME level of stratification among non Irken races#And Irkens are like. ok they’re genocidal space fascists but they’re ALSO hyper capitalist right#There’s something you can string together that makes sense but leaves the key pieces intact.(#Bouncing between this and Imperial Radch for scrapings of hyperfixation juice is really funny#A surprising amount of overlap to be found

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

17th February: Frank Churchill longs to dance again

Read the post and comment on WordPress

Read: Vol. 2, ch. 11 (29); pp. 160–162 (“It may be possible to do without dancing” through to “quite amiable enough”).

Context

Emma and Mr. Woodhouse spend the evening at Randalls. Emma and Frank scheme after another opportunity for dancing.

We know that this occurs a “few days” (vol. 2, ch. 12; p. 167) before “two days” (ibid.) before “Tuesday” the 22nd (vol. 2, ch. 13; p. 172); thus it must be the 17th unless “a few” can be allowed to mean “two.”

This chapter was misnumbered XIII in the 1815 edition.

Note that the last paragraph of the first section (“The Advantage of Being in Vogue”) contains spoilers.

Readings and Interpretations

The Advantage of Being in Vogue

This section opens with the following memorable passage:

It may be possible to do without dancing entirely. Instances have been known of young people passing many, many months successively, without being at any ball of any description, and no material injury accrue either to body or mind;—but when a beginning is made—when the felicities of rapid motion have once been, though slightly, felt—it must be a very heavy set that does not ask for more. (p. 160)

For Graham Hough this is the “authorial” voice, separate from the narrator, which exists for no purpose other than to “establish a footing of agreeable complicity between author and reader” (p. 204). Rachel Oberman, however, argues that this passage originates with the narrator, a separate, “objective” personality who narrates characters’ “subjective” thoughts. She writes:

In many instances, it is difficult to distinguish the heroine’s voice from the narrator’s because their voices share a similar style and vocabulary, and this connection helps the narrator to fuse her voice to Emma’s less noticeably. In Emma the narrative voice is charming and high-spirited, much like the eponymous heroine’s voice. The narrative voice in [this] passage is as pleasant and worldly as Emma’s own voice. (p. 4)

Robert Polhemus writes that Austen’s irony “depends on its audience to detect and complete meanings extending beyond the literal sense of the language. […] Irony is her mind’s bridge between what is and what may be or ought to be, and at times it spans and supports alternative interpretations of reality, none of which she is ready to discard” (p. 66). He says of this passage:

At first this appears to be just a piece of rather obvious irony directed against the tendency of young people and others to make much of little. Of course it is “possible to do without dancing.” But on second thought there is a deeper irony. Humanity may be able to do without dances, but we can’t be very sure, since the race seems seldom to have tried. […] And that precise, yet generalizing, elegant, typically Austenian phrase “the felicities of rapid motion” extends the irony further. All dances are essentially mating dances, and the end, as well as the means, of dancing is the felicity of rapid motion. Through such prose and such manifold strands of irony Austen brings home the importances of the “little things” she writes about and of the whole tenor of women’s belittled lives. A conventional ironist might find balls trivial, much ado about nothing, but the ironist of genius may discover that dancing is even more significant than anxious dancers can imagine and that just as a dance may be much more important to a particular woman than a Napoleonic war, so might the fact of dancing be just as significant to the human race as the face of battle (p. 67)

Oberman’s argument that it can be “difficult to distinguish the heroine’s voice from the narrator’s” holds true when, a little further down the page, someone suggests that the “wicked aids of vanity” (p. 160) are increasing Emma’s wish to dance: is this narrator’s dour moral condemnation, or Emma’s knowing, playful self-mockery? As for Frank, of course his desire to dance again (and more specifically to re-collect the party that had been at the Coles’ two days before) can be explained by his thwarted attempt to dance with Jane Fairfax on that occasion.

Quite Amiable—Enough

Mr. Woodhouse, after the others have considered a scheme to dance across a passage between two rooms, laments that Frank Churchill “has been opening the doors very often this evening, and keeping them open very inconsiderately” (p. 161). Jonathan Grossman, who argues that “maintaining proper etiquette” is the “leisure class’s everyday work” in Emma (p. 146), writes of Mr. Woodhouse’s speech and Mrs. Weston’s reaction to it (from “it would be the extreme of imprudence” to “Every door was now closed”, p. 161):

At first glance Mr. Woodhouse’s reaction to Frank may seem little more than the ramblings of a petty hypochondriac. Yet when Mr. Woodhouse converts his fear of dancing in drafts into a condemnation of Frank’s “thoughtless” and “inconsiderate” behavior, his [class-based] authority is quietly asserted. […] Mr. Woodhouse’s lowered voice is heard by others besides Mrs. Weston, as is shown by the generalized and serious reaction to it that follows.

Registering Frank’s disrespect, Mr. Woodhouse acts not as a guiding autocrat but as a seismograph for tremors. He reacts. […] [P]reoccupied with matters that seem to be irrelevant, Mr. Woodhouse can all the more effectively test and register obedience to the strictures of politeness. (p. 147)

Grossman argues that this failure of etiquette is what makes Frank unmarriageable to Emma: “Her father’s disqualification of Frank Churchill is not lost on Emma, though she remains silent. In fact, her silence may suggest that she is thinking rather than hastening as usual to rescue her father from agitation and to smooth over discord” (p. 147). Later, Emma’s thoughts on the dance floor, “rendered in free indirect style, contain the novel’s first specific indication that she has decided that she is not interested in marrying Frank” (p. 148) (“Had she intended ever to marry him, it might have been worth while to pause and consider…”, p. 162).1

For J. F. Burrows, “Emma’s multi-faceted relationship with Frank Churchill […] can be epitomized at last in the rise and fall of her belief that he is “amiable” (p. 93). This is a word that Emma uses “more carefully” than do others in Highbury at this point of the novel, after having learned from her mistake in misapplying it to Elton (or when, for example, Miss Bates calls Miss Campbell “extremely elegant and amiable” (E vol. 2, ch. 1 [19]; p. 103), and Emma “comments drily on the proviso, ‘Yes, that of course’” (Burrows, p. 94).

Burrows argues, in particular, that Emma uses the term in a way that emphasizes its etymological association with love (and this is why Knightley responds as he does to her calling Frank “amiable”; E vol. 1, ch. 18; pp. 96–7). At first, Emma decides that Frank is “amiable” on the basis of his letter (ibid.); later, Emma’s “intimacy” with him ends after he teases Jane, against her protests, at the Coles’ party (and she “never confides in him again”; Burrows p. 93). Now she calls him “amiable” for the last time, but “in an ironically diminished sense” (p. 95): “Had she intended ever to marry him, it might have been worth while to pause and consider, and try to understand the value of his preference, and the character of his temper; but for all the purposes of their acquaintance, he was quite amiable enough” (E p. 162).

Footnotes

Earlier, though, Emma had been “guessing how soon it might be necessary for her to throw coldness into her air” towards Frank (vol. 2, ch. 8; p. 137). How Emma’s prediction that she may never marry at all interacts with her specific decision that she would not marry Frank Churchill is not always clear.

Discussion Questions

What is the narrative or thematic purpose of the paragraph about dancing that opens this section? At what level does its irony function?

What does Frank Churchill’s determination to dance say about him as a character, or his place in the narrative?

Why do the others give up the scheme of dancing across the two adjoining rooms as soon as Mr. Woodhouse objects?

Bibliography

Austen, Jane. Emma (Norton Critical Edition). 3rd ed. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, [1815] 2000.

Burrows, J. F. Jane Austen’s ‘Emma’. Sydney: Sydney University Press (1968).

Hough, Graham. “Narrative and Dialogue in Jane Austen.” Critical Quarterly 12.3 (1970), pp. 201–29. DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-8705.1970.tb02333.x.

Oberman, Rachel Provenzano. “Fused Voices: Narrated Monologue in Jane Austen’s Emma.” Nineteenth-Century Literature 64.1 (June 2009), pp. 1–15. DOI: 10.1525/ncl.2009.64.1.1.

Polhemus, Robert M. “Jane Austen’s Comedy.” In The Jane Austen Companion, ed. J. David Grey et al. New York: Macmillan (1986), pp. 60–71.

11 notes

·

View notes

Note

Heya, I was wondering when literary theory / critical theory really clicked for you? I’d love to be able to throw myself into it, and I do find it interesting, but there seems an inexhaustible quantity and tbh I struggle to understand a lot of it. I’m in the 2nd year of a literature course - did it take you a while to learn to navigate/appreciate theory, or is it just naturally your cup of tea? xx

Hi – tricky one, I think it all happened quite holistically and very slowly, it crept up on me. The short version is I spent many years faffing about and then it all kind of came together when I realised reading and writing theory is very personal/like a conversation. The long version is below the cut, seems the button isn’t coming up on the blog so click here if that’s the case

In my second ever seminar at university we talked about theories of interpretation and it was like a big light that had been off in my head for my whole reading life suddenly came on. I was excited, because the death of authorial-intention-based approach gave life to theory, empowered readers to enter into a relationship with the text that was meaningful and new. It made me feel like I could use my experience as a frame through which to view literature rather than just searching for a right or wrong answer to unlocking the text. Despite this I thought reading the actual theory was exceptionally boring (probably Saussure’s fault, or rather my fault for being too stupid to understand the genius implications of Saussure) and struggled to connect my excitement at reading fiction theoretically and, well, actually reading theory texts.

I was on a joint honours creative writing programme which I had been accepted to based on a portfolio of my prose, but my first year was terrible. It wasn't even that I was a bad writer, I was just painfully mediocre and felt I had nothing to say. I constantly felt I was contriving to make something meaningful, my tutor was encouraging enough that we shouldn’t wait for a muse or a moment of inspiration to write but though I pushed through I was consistently marked down in submissions and peer reviews. It was really tough and I wanted to drop out many times, to go and pursue art which was becoming a bigger part of my life all the time – I was making work with other artists and entering into the world of art school which seemed more exciting. At the end of my first year I was seriously thinking about dropping out to pursue fine art full time.

Something made me not do that, and I think it was theory – probably in the disguise of modern poetry. I had really enjoyed reading poetry before university but I was convinced I was not good enough to write or write about poetry myself. The class made me realise that poetry was a perfect example of the kind of reading and thinking I really loved: poems are puzzles, often they read like a big knotted textural wall of words at first, and then one line comes out like a thread and you pull it and it all starts to become understandable. The thread lodges itself in you, or becomes part of your own tangle. That’s like how theory feels to me, like the tangle of texts and ideas coming together to tell us something about our own tangles. I wanted more of that.

I had to choose whether to take a prose or poetry focused class in my second year creative writing programme, and given how poor I was at prose I decided to take a leap and try poetry. I still had a year to go before I had to choose for my final dissertation portfolio, so I figured it made sense to get a bit of both anyway. Basically I resigned myself to being lost and looked for guidance. I also took classes in the most basic principles of literature and culture – a class on Shakespeare, a class on Modern literature, a film class.

I fell in with a group of incredible young poets in my second year class. Their grasp on it was already so well-formed, they could do things with words in a ten-minute exercise that I couldn’t write in ten years. I fully assumed the role of the blank canvas and let the class shape my writing. I had some good tutors too who were hard on me at times but ultimately completely changed my approach. I think it’s something to do with having gone in completely humble to it second time around rather than in my first year when I thought I had an understanding already. One of the poets was really into theory. They showed me how it wasn’t all boring, how some of it was really radical and pushed the boundaries.

It wasn’t until my final year that I put two and two together I think. It was the thing of experience, reading, writing, all becoming the same process, informing each other. I chose poetry fully, threw myself into it, and I also discovered creative non fiction. The two together led me to theory in a big way – writing about my experience, reading about others’, writing about both. I don’t know if that even makes sense but that’s what it felt like. My portfolio, on liminality and duality and transnationality, argued for a personal, subjective approach to poetry, not an objective one. That was when it happened for me, reading about things I understood not because I was smart but because it spoke to me and my experiences, became part of my ‘tangle’.

Anyway this is a very long way to say theory is deeply personal and that approach worked more for me than any amount of academic commitment to marks, grades or careers. It’s a deep seated need to understand myself and the world that takes me to theory again and again. And the understanding too that the process with theory is never over, there’s always more, but not being overwhelmed by it – I find it comforting to know how little I know. That’s where my appreciation for it and my way of navigating it come from, just knowing it’s bringing a personal and subjective view as part of an enormous collective dialogue between all these different minds across all of time. The texts talk to each other and they talk to us, you just have to enter the conversation.

whew that was quite the brain dump!

111 notes

·

View notes

Text

the big light

The Mirror and the Light has been in the works for a long time. I read Wolf Hall shortly after its release in 2009, and loved it. Same with Bring up the Bodies in 2012. Two years after that my wife and I went to see Hilary Mantel read from The Mirror and the Light at the South Bank Centre. Back then it must have seemed like the release wasn’t too far away; had someone told me then that we wouldn’t see it till 2020 I would have thought them unhinged.

It’s long — well over 700 pages. At first glance the length might seem surprising because this is not (for want of a better term) the sexiest part of Henry VIII’s rule. The story is one of those notorious miscalculations of history: after the death of Jane Seymour, who is often thought Henry’s most beloved wife, a marriage is arranged between him and Anna of Cleves. She is a woman from a distant German state who Henry has never met; the union is essentially one of convenience, because England’s international situation has rarely been more complicated.

Following the reformation, England has been excommunicated by the Catholic church. In theory, both the nation and its ruler are fair game for invasion or murder by any loyal Christian nation. In practice, the uneasy relationship between the rulers of France, Italy and the Holy Roman Empire makes that far from straightforward, but the risk seems real all the same. Cromwell faces further trouble at home — riots and uprisings are becoming more of a problem, motivated in part by deep local affections for the old religion. Thomas is the most powerful he has ever been but he’s still surrounded by enemies, especially amongst the old families of England, who have never allowed him to forget his humble origins.

It may seem as though there’s a lot going on, but by the end of the novel I felt like there wasn’t enough to justify the sheer weight of paper in my lap. This is not to say the writing isn’t good. It is often great. But this is a novel light on surprises. I enjoyed reading it all the same – it’s enough for me to be carried along by Mantel’s authorial presence, which still feels absolute and omnipresent. Cromwell’s personality in these novels is one of the most compelling characters in fiction. Yet there’s very little in The Mirror and The Light which we haven’t encountered before in the two previous novels. The same scenes from his life come again and again — the death of his wife and children in Wolf Hall, and those endless scenes with Anne in Bring Up the Bodies. The same lines become like motifs: arrange your face, so now get up, and so on. Perhaps the problem with a novel where you see everything is that after a while you start to feel like you’ve seen everything.

We feel there isn’t much that is new to discover about Cromwell. There are a few exceptions; the rumours that grow up around Cromwell regarding prospective new marriages are not without interest. But I found little here which sticks in the mind like the scenes from the earlier books, and part of the problem is the whole concept of ‘scenes’ as they exist here.

The preceding novels have now had at least two major adaptations — one for the West End stage, and one for TV. I saw both, and they were good, solid, conventional. A cynical reader might declare that too much of The Mirror and the Light feels like it’s been written with dramatic adaptation in mind. At times it seems less like a novel and more like notes towards a screenplay. There are endless conversations which seem intended to be tense, dramatic confrontations, but which never seem to advance or demonstrate anything.

And yet as soon as the novel switches back into the interior mode, you almost want to forgive it everything. Being in Cromwell’s room is like working your way through a series of rooms in a museum — full of detail and diversion — and it’s wonderful, except the novel keeps pulling you out of it like an excitable tour guide who can’t help but subject you to another conversation, another insignificant moment from history, another scene.

I feel like the previous novels weren’t like this. But I still feel like I’m too close to them to go back now. The best I can say of The Mirror and the Light is that it consolidates the vision of Cromwell as perhaps England’s greatest ever reformer and renaissance man. He wins the long game in the ways that matter: not only the break from Rome, but in the idea of the monarch and state as deserving respect entirely separate from any religious obligations. In these books Cromwell also seems to stand for something profound in the idea of the British idea of the self-made man. He plays to our love of the self-starter, the man who started out with empty pockets and a seemingly infinite set of talents, and who took on the establishment. He won, but in the sense that he lived long to see himself become the establishment, and to be swallowed by a machine he had built to catch others. (And there’s something additionally satisfying in this kind of downfall. We love to see a man build himself up, but we also love to see him torn down to size.)

In the end, there is something drab and faintly disappointing about Cromwell as he emerges here. All his work was not in service to anything greater than himself. The pursuit of humanistic knowledge, the service of his prince, and the consolidation of his own power — what was his legacy outside of this? Part of Mantel’s genius is to work that thread of disappointment through the text here; Thomas is constantly looking to his own legacy, worrying that he hasn’t done enough; he is preoccupied with his mistakes and things he could have done better, like the death of William Tyndale. In this way he emerges as a bit more human: he is someone who, like any of us, is worried about what he will leave behind.

And yet it’s hard to feel too sorry for him by the final pages. Our sympathy is limited in part because his success has been so outlandish, and in part because of his lack of anything resembling sympathy for the world around him. He is devoid of intimate, empathetic connections. Alms for the poor and the foundation of a few schools don’t quite cut it — philanthropy is only the rich man’s way of paying his debt to society on his own vastly skewed terms. His servant Christophe is his most intimate friend, perhaps because he reminds him most of himself as a young man. In the end it seems there is nobody else who will miss him.

10 notes

·

View notes

Note

hey you, i only followed you recently and I really like your hinny fanfics and your poetry. Would you mind telling me about your process when you write? I really wanna learn how to write properly and you seem to take your craft so seriously. How do you built a story, how often do you edit, how much time do you spent on your work, what do you try to go for,...? Thanks xxx

Anon, this is the coolest ask I’ve EVER received, and I’m hanging it on my wall next to all the colour-coded flashcards with poems on them. This is going to be LONG, and by no means exhaustive - I’m gonna jump around and ramble a bit and if there’s anything specific you wanna hear more about, please ask! I fucking love talking about writing!

I’m gonna put most of this under a cut, but before we dive in: yes, I tAkE mY wRiTiNg sErIoUsLy in the sense that I’d like to publish some original bodies of work in my life and to have physical copies of them exist on a bookshelf that’s not my own. I don’t need it to pay the bills, but if you googled my full name I’d like for, like, a poetry collection to show up and not, I don’t know, the two poems I got published in a regional newspaper when I was eight.

(And please let the record show that they’re fine poems for a primary schooler. The cringe years came way after that, kids.)

So, even having some ambitions in the industry, the reality is that I’m a 19-year-old kid with a keyboard and a dodgy internet connection who discovered fanfiction when she was twelve and got hooked for life. We’re going to retire the idea of “writing properly” for now, because writing is supposed to be fun and I haven’t actually gotten accepted into that Creative Writing Bachelor’s degree I so desperately want to do. YET. Don’t let the fancy writing blog (@jessicagluch) fool you into thinking I know what the heck I’m doing. But, okay, with that out of the way, let’s get into what I’m personally doing right now, yeah?

Fanfiction

You asked about process, and the truth is, I don’t … really have one. For the Muggle/FWB AU called “Let Me love” I just published, I actually wrote a pretty detailed outline that I then filled in, which was fun, but it’s not a habit exactly. I’d written a lot of assorted scenes and pieces of dialogue for that one, too, so I had a lot of material and just had to put all the scraps and pieces in order and stitch it all together. After the brainstorming, word-vomity part of writing Let Me love, my #1 task was figuring out where everything went, and making sure it’s all there.

As soon as I’d written a full first draft, no gaps, and the anatomy of the whole thing had somewhat clicked into place, I moved away from it for a while. Wrote something else. Came back maybe a week or two later, polished up the prose a bit very late at night.

Figure out when your creative hours are, if you can pinpoint it at all. Mine are precisely “I was supposed to be asleep two hours ago and I’ve got an important thing tomorrow” o’ clock. Sigh.

Just - leave it alone for a bit, come back with fresh eyes. I love writing Let Me love - I’m working on part 2 right now - but after you’ve fucked around with the same sentence fifty times, you get sick of it. And I did. At some point you have to decide to put down the pen and let it be.

Especially because fanfiction isn’t something you’re writing for a publisher - hopefully, you’re writing it mostly for you - no one is holding a gun to your head to get rid of every last adverb or stuff like that. I can do what I want, MOM. I am allowed to make the thing I’m writing as tropey and campy as I want and hold up a big old middle finger to the rules, if that’s what I want to do.

Fanfiction, to me, is this grand, batshit writing playground. That’s why I fell for it in the first place - it’s inherently self-indulgent and hedonistic and that you can write everything EXACTLY as you please is the primary purpose it serves as a genre. So go wild.

(Process-wise, the one thing I do very consistently is making moodboards and playlists. I like having some inspiration material to swim around in, which helps me figure out what the story looks and feels and sounds like in my head.

Every fic has a soundtrack. SOUNDTRACKS ARE IMPORTANT, PEOPLE.

Like, Let Me love is all coloured lights and night-time London and texts left on read. It’s neon signs and wearing somebody else’s t-shirt, messy bedsheets and hangover breakfasts and quarter-life crises.

This is the Pinterest board.)

What I pay most attention to is the stuff that gives the text depth beyond the surface. I look for metaphors - and I personally prefer the ones that carry through the whole thing, ideas we explore throughout the story and revisit at the end. I look for themes that hold a story together beyond the plot. I look for subtext and imagery and I want symbolism, goddamnit.

(That’s the poet kicking in.)

And of course, I’m a product of my generation, so I love referencing other bodies of work and subverting tropes and stuff like that. Hey kids, intertextuality is fun!

(Like, do you see what I did there? See how the phrase “hey kids x is fun” in itself is a reference to something? See??? I’m a fucking genius.)

I think we need some examples. Allow me to toot my own horn for a minute.

In the Halloween 2018 oneshot I wrote, which is about Harry grappling with the anniversary of his parents’ death when he’s a little older, he visits the graveyard with Ginny and Lily Luna. Ginny comments that “it’s freezing”, to which Harry responds with the titular, “you’re warm”. And yes, it’s October, it’s probably cold. They’re keeping each other warm. And yes, it’s maybe about comfort in harsh situations in general, a more metaphorical warmth, if you will. I get it.

But when you remember this exchange is taking place on a graveyard, you might start to wonder about warm, living bodies as opposed to cold, deceased ones. And then you think about how this whole story is about the living remembering - in a sense, living with - the dead. And how it’s about death as a part of Harry’s life. And you can probably guess by now that all my literature teachers fucking adored me.

(But he’s also choosing a side here, maybe. But I’m merely the author, you don’t have to listen to me at all. My words beyond the words don’t mean shit unless you decide they do and even then you’re going to find yourself knees-deep in a debate around authorial intent in record-time. In the age of “Nagini was a cursed human woman all along”, I’m not sure I want that.)

I also reference other pieces of work a lot. Often poems, and even more frequently, songs. The songs in Let Me love are VERY IMPORTANT and I can’t show you the full playlist right now because SPOILERS. But the chapters are split into sub-sections via song lyrics. Those are part of the playlist. There’s also a lot of referencing songs in general because Harry is a big music fan in this one, but that’s just indulgence on my part. If I want to make a 21st century Harry a Mitski stan, then I will. And I did!

(AND Let Me love has a Friends reference. For funsies, but also, for much more than funsies.)

“I love you / please do not use it” was inspired by a poem by Savannah Brown called “organs”. (It’s linked in the author’s notes at the beginning.)

“It’s two sugars, right?” borrows and/or references a ton of lines and phrases from T. S. Eliot’s The Hollow Men. Most noticeably:

Sublety isn’t my middle name, exactly. (The forget-me-not-blue sky in The Bride On The Train, anyone?)

In short: I like when my fanfictions are worth rereading. I like when you can come out the second read having found a little more than you did the first. I like when you can wander around a little, and, like a treasure hunter, make some strange new discoveries.

Lastly: of course, writing from your own experience helps. Spy on your own life. Collect all the ways in makes you feel, like a thief, write it down, memorise it, put it in the story. Reuse! Recycle! ✊🏻

I fortunately don’t relate to Harry’s childhood trauma, but the feeling at the beginning of “We’ll figure it out” - which is a story set shortly after him and Ginny find out she’s pregnant and he’s struggling to connect with everybody else’s simple bliss, because he’s terrified, and he’s terrified of admitting he’s terrified - that was real. That “wait a minute, this moment is amazing. I’m supposed to be the happiest person on the planet right now. Why am I not feeling it? What is this emptiness? Am I not happy right now? Why am I having doubts? I’m not supposed to have any doubts! What the fuck is wrong with me?”, that was lifted from a specific experience.

Side note, I’m really proud of that one.

Okay, poetry!

Where there is even less rules and more fucking around ensues!

I read and promptly lost a quote recently about how explaining a song sort of defeats the purpose. (I’ll link it here if I ever find it again.) In some ways, poems and songs work really similarly, and I think it applies here as well: if you could really explain the whole poem in one sentence, or a few sentences, if you could accurately and concisely summarise exactly how it feels, then you wouldn’t really need the poem. My favourite poems (or songs) tend to be the ones that outline a really specific emotion via a few powerful images, but I couldn’t precisely tell you what the emotion is. Like, I know exactly what this thing is saying, I know this exact feeling, I GET-GET it, but don’t ask me to explain the thing, just READ the THING, and you’ll KNOW.

Mitski does this really well. Like, I couldn’t explain to you what Last Words Of A Shooting Star makes me feel, but it does. I can tell you that “I am relieved that I left my room tidy, they’ll think of me kindly when they come for my things” cuts through me like a hot blade but I can’t pinpoint exactly why and I don’t want to. All I know is she Gets It, and that I want her writing chops, goddamnit.

Or, like, look at Laura Gilpin’s Two-Headed Calf. Yeah, I’ve read that poem a hundred times and thought a lot about all the themes it’s presenting me with. But I have zero desire to explain those themes to you, because I’d kind of be robbing it of its magic. I don’t want to tell you what it’s about. I want you to read it and I want to simply sit with the knowledge that we know, we Get It, that “twice as many stars as usual” kicked you in the shins, emotionally speaking, as much as it did me.

Few words, max impact, is key.

In Mary Oliver’s words, we want something inexplicable made plain, not unlike a suddenly harmonic passage in an otherwise difficult and sometimes dissonantsymphony - even if it is only for the moment of hearing it.

I’m realising right now that leading with these shining examples and then following them up with my own thing is nerve-wracking. But I like to think that I accomplished something like that with a little poem I wrote called Basements.

It’s is based on the prompt “back to nature” and follows that, uhm, somewhat loosely, a little subverted. I think it’s about impermanence and nostalgia and the fact that the places we lived in continue to exist even when our lives in them don’t anymore. It’s about that and a lot of other things. Maybe. The truth is, I don’t want to explain it to you: I just want you to read it, and then I hope that it made you feel something, and I’m going to trust that you Get It. Maybe you don’t get the same things I did, but that’s great. I’d love nothing more.

Before it was all those things, it was a poem about my life. The neighbourhood with the yellow house across the graveyard that I spent nine mostly happy years in. (The house, not the graveyard.) Every single thing in there is true: my sister really bust her lip and we both cried; wild lilac really grew there; we did spend most of our summers catching tadpoles, and yes, that neighbourhood was a construction site from the first day we lived there to the very last.

And I really sat in the driver’s seat of the family car about a year ago and watched it from afar. I didn’t come up with that - it’s my life. I only went on a scavenger hunt through my own memories, through the places and records and mementos of my life, and arranged a few specific anecdotes in a way that would give them meaning.

It’s kind of what I’m proudest of when it comes to my poetry - that I get to just live my life and see the metaphor and the meaning and symbolism as I’m experiencing it. I sat in the car and I thought, huh, that’s definitely making me Feel A Thing right now, that I’m sitting in the driver’s seat looking at this place I haven’t really been to in years, my childhood home, where I don’t live anymore. That I drove here myself.

I think that, when done right, specific makes universal. If you arrange a kaleidoscope of memories in just the right way, what it’s making you feel will speak for itself, and you won’t have to explain it. Most people who’ve read “basements” probably didn’t spend countless summers playing in literal holes, originally dug out for basements that were never built because no one wanted to move there. Holes that then grew full of weeds and wild lilac and felt like miniature jungles right outside our parents’ houses. It was perfect, it was specifically mine, but the feeling behind it is universal, I think.

Like, that’s how half of Taylor Swift’s RED works. That’s how most good Taylor Swift songs work. That’s why the bridge in Out of the Woods is so good and why I love New Year’s Day so much and it’s EXACTLY why All Too Well is considered her best song by so many people. Because she zoomed in on the details of her life and let the world take a look. Because “we dance around the kitchen in the refrigerator light” is a line in that song. THAT’s why it MAKES YOU FEEL THE THING.

Back to poems? This:

So we tell them all about the dayWe planned revolutions on my bedroom floor, or how we onceSpent an entire Monday lunch break making life plans over ice creamAnd most of our parties talking politics over beerWe both paid for ourselves.About the days you drive me to school. In your carI am the girl, front-seat passenger of our lives,Who does not need reach for the steering wheel –The road is alright.

isn’t fiction. These are my memories, carefully selected and re-arranged for Politics at Parties Boy.

I didn’t make up these film stills of a non-romantic relationship that never became anything other than non-romantic because neither party ever made a move. What I did is look at my own life like it’s a piece of fiction. If these memories were a movie, you could pluck them apart and say, see, the screenwriters put this scene here to communicate that.

The truth is, I am the screenwriter and the protagonist and the actress and the director and the camerawoman. I looked at a teenage girl who refused to let her friend buy her a beer at a school party and decided “huh, I guess that tells us everything we need to know” because I was that girl.

And I did pay for the beer, so we’d never move into “let me buy you a drink” territory. He was already driving me to school.

That’s my best lesson on poetry, really. I look at my life like it’s a piece of fiction and then I make it one. I put personal memories in poems meant to be read by other people, I overinterpret everything that happens to me, am literally constantly thinking about how to work every knock-back and struggle into my narrative arc and look for symbolism in anything from the date, the weather, and the colour of my front door. I watch myself in third person all the time and thus become my own muse. I’m the painter and the painting.

It’s a somewhat narcissistic and masturbatory approach to poetry, but as far as writing about your own life goes, it’s what works for me.

As far as writing about not yourself goes - well, I’m a narcissist and I’m bad at that, but I wrote a poem about the Mars rover Opportunity that shut down this February called Spirit shuts down and Opportunity feels no tremble, no ache. For stuff like that, if you don’t happen to be Struck TM by a lightning bolt of inspiration (which is the exception, not the rule), a good old-fashioned mind-map helps. I just let my robot grief go wild on the page for a bit and what I ended up writing about was death and the human condition and being a teenage girl, maybe.

I really enjoy taking two concepts/ideas and juxtaposing them, watching a theme unfold in the overlap. Like, it’s a poem about a robot AND about being a teenage girl and in between those two lies a poem about the futile attempts to teach a robot human emotion. Maybe.

It’s a poem about how my mum always cries at the airport and about me making my own happiness my priority and it kind of ends up being about my intense guilt of making my parents watch me change and grow and leave.

It’s about the night I wandered through a quiet street in Central London at 1 a.m. and realised that the city of my dreams sleeps like any other place, that people wake up early and make coffee and go to work and have bad days here. That it’s not all dream. It’s some people’s lives. But it’s also about watching another person sleep - the way someone’s face changes when they do.

In the middle lay a poem about finding a friend in a lover. Not the daydream, but my life.

Lastly, I can’t talk about my own poetry without talking about my darling poem 5 disasters. It’s my pride and joy. Like, you could kill me write now and I’d be like, it’s okay, I’ve written the poem I want to be remembered for and it’s this one. I wrote it in less than a day and every time I think about the fact that I wrote

I cravedsomething more violent than death, somethingviolent enough to bea beginningand for my life to be thousands of themI wantednothingto remainexcept the girl that sentthe disastersand survived -may this wasteland bewhere I find her.

… I lose my shit a little bit.

(5 disasters was a rarity in how quickly I wrote it. It often takes me weeks. Sometimes months. There’s poems I’ve been meaning to write for years now and I still haven’t found the words. Take your time.)

5 disasters is a lot of things, but within the context of the poetry collection it’s hopefully going to exist in one day, it serves as almost an instruction manual for metaphors: here, the floods and rainfalls are always change and the forest fires are always my highschool demons and my friends and how they look the same. The colour yellow is always referencing the same love. Basically, I like pinpointing my symbolisms and then crafting a poem around them. You end up creating something like an in-poem universe that you get to navigate like a fantasy novel. Like you’re telling a story about a natural disaster, but it’s all a metaphor, Hazel Grace.

But I’m getting ahead of myself. As I do.

I hope this serves as a starting point of sorts, anon. Most importantly, have fun, don’t concern yourself with all the rules too much. Experiment, be bold, read lots.

Again, if you’ve got any questions, I’d be thrilled to help. Thanks for the opportunity to toot my own horn to this outrageous degree, it’s been a blast.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Dear diary, today I learned something about myself…” Nora mumbled to herself.

Nora HATED the daily writing assignments. It was the worst part of school. If you could call the one tiny room she and 7 other girls were shoved into a school. Nora was 16 and lived in a group home. Her parents were addicts who were never in her life longer than a month or so at a time. Nora had been in foster care as a small child, but she became more and more rebellious as the years passed, and the state deemed her “unfit for society”.

It’s not that Nora was a “bad kid” she was just misunderstood. The years of being bounced from home to home, new moms, new dads, handsy “big brothers”... anyone would crack under the situations she had been forced into as a child. Nightmares were her safe place, for reality was always way worse than her wildest dreams.

“Today, I learned that yet again... no one gives a fuxk about me.” Her mother had missed another visit- no big surprise there. Her mother had missed all but one visit in the last three years. What was really bothering her, was the note she had received at lunch a bit ago. Ivy was the “popular girl”, which wasn’t much of a title in a home of only 8 girls with no contact with other teens.

The note was from Ivy. Ivy was 17 and was considered the “popular girl”. Not that the title carries much weight in a place you only see 7 other teens and have no access to internet. Jade had dark brown hair, almost black. She had managed to obtain hair dye, which was a HUGE Nono in the group home and had a streak of teal on her hair. Her grey eyes always looked like they held a secret of yours.

Nora shied in comparison. Mousy brown hair, shit brown eyes, and glasses. She knew she was nothing special. But for some stupid reason she had jotted a note in Ivys journal asking her to meet behind the large tree at lunch. Her hands had shaken as she took the note from Ivy. She excused her self to the bathroom to read it as notes were forbidden.

The words she read burned in her head- Behind the large tree? Why so you can try and kiss me or something you dyke!

The accusation of being a dyke wasn’t what bothered Nora, she had been called that on and off for several years... since the first time she kissed a girl at 12. Was she a dyke? She wasn’t sure what or who she was. But she was upset that ivy wouldn’t even consider meeting her.

Why had she thought it was a good idea... furiously she kept scribbling in her journal as her internal monologue was beating her up inside.

“Not only does no one give a fuck about me, not my parents, not my teacher (sorry miss adams), not the other girls, but I don’t give a fuck about me. I’m not even me! I’m not Nora. I feel so wrong in this body. It doesn’t make sense. I don’t feel like me. I look in the mirror and see a stranger, I’m more than my shell. I’m more than my record, I’m more than my behavior. But does any one see the real me? No! They just see this spoiled girl, who doesn’t listen and is a burden. Fuck that. I’m tired of being everyone’s burden. I’m tired of being alive. I wish I were dead”

Chest heaving she stared at her own words that she wasn’t aware were inside her. She knew she meant them, but she wasn’t aware how deep her self hatred had run. She wasn’t aware she had been at her wits end for so long. She started to panic. Miss adams could NOT read this. They would send her away. But ripped out pages were grounds for punishment.

She looked around for something, ANYTHING she could spill on her paper. As she stood up to refill her water bottle hoping she could tip it over on her journal, Ivy snatched her journal.

“Miss Adams! Look at this! Nora is unsafe!”

Miss Adams was always two steps ahead of everyone. She grabbed the journal and begin to read the entry from the day. “Nora, will you please head to Miss Avarados office now please? Tracy, you will go with her till she is inside.”

Noras shoulders slumped, she knew that this would mean at BEST a week or two of restriction. And at worst... the trash bags of her belongings would move homes yet again...

The door opened with a creak as Nora stared at her torn off brand chucks. Miss Alvarado was in the doorway looking as foreboding as ever. With her voice that seemed to vibrate off walls she stared at Nora,”thank you Tracy, you may go”

Inside the office was only furnished by the therapists desk, and two chairs. One for the overbearing councilor, and one for which ever girls turn it was to be miserable for an hour 2x a week.

“Nora, you are normally one of the ones I don’t worry about which is surprising considering your... track record... why did I receive a call from miss Adams to check my inbox for your journal entry? Are you really that unhappy you want to take your life?”

Nora continued staring at her shoes, maybe if she pretended this wasn’t happening, she could will it into reality. THWACK. Miss Alvarado had smacked the desk with a file. Not just any file, but Noras file. “Nora, I think the best course of action would be to send you to St. Peter’s for a few days for your own safety. You may return once your bout in St. Peters is over “

Nora stayed stone silent for a few moments. Tears welling in her eyes that she would never release, she steadied her voice,” I understand miss Alvarado. I’ll pack my things”

“Nora this is a temporary stay, that won’t be necessary. Bobby will pull up the van and transport you from the office.”

The car ride seemed to go on forever. As the evening drifted into darkness, Nora realized it was much too long of a drive. They should have been there ages ago. City turned to country roads and green hills. She had never been this far from the city. In the distance she saw a small orange glow. She had ridden with Bobby in complete silence besides the flick of his bic as he light up a menthol cool. She decided it was time to finally break the silence.

“Bobby... I’m thirsty... are we almost there?”

Bobby barely acknowledged her besides a small grunt. The orange glow grew larger and she realized it was a small building. She hoped this meant she could at least empty her bladder. It definitely was not St. Peter’s, but at this point she didn’t care where they were as long as they stopped. They pulled into a gravel drive and Bobby parked the car. He got out and lit up yet another menthol.

Nora tried to open her door only to discover it was child locked. The house van never had child lock on it. She began to pound upon the window begging Bobby to let her out. He turned from her and leaned against the drivers side door, staring out into the darkness. The door of the building slowly opened with a blinding light. A figure walked out of the front briefly blocking the light. As the person walked closer Bobby stood up and shifted his gait nervously.

“This her?” The new comer asked gruffly.

“Hey Chase, yeah. She’s ready for transport.”

Transport? What did he mean transport? Wasn’t he supposed to take her to St. Peter’s? Who was this new guy. Why were they discussing her like she was an animal?

The door opened and she was pulled to her feet roughly. She began to fight to try and get away. Chase tackled her to the ground. There were suddenly 3 sets of hands pinning her to the dirt. Before she knew it she was hog tied behind her back. Sobbing and tasting blood she started to black out as she was lifted into the back of a small sedan. She woke up what must have been a few hours later. It was still pitch black and there were two people up front driving.

Chase was behind the wheel, and talking to a woman in the passengers seat. The lady noticed Nora had woken up and nudged him. Instantly the silence was deafening. Chase turned around and swore under his breath.

“Hey Emily, we’re almost to the pit stop. About another hour.”

Nora tried to speak but her mouth was so dry she could barely speak.

“Uh... Chase... I really need to use the bathroom, and could use some water.”

“You can wait.”

“Babe... the girl needs the bathroom. Come on we can grab a drink when we stop.”

Thank god for Emily. The car stopped and she cut off the zip ties on Nora that had been holding her wrists and sat her up. They had apparently stopped at a seedy bar... she couldn’t go inside, she wasn’t even 18 yet, how did these two genius’s think they were going to get her in?

Maybe she could make a run for it once she got inside? CLICK. The sound was a cold metal handcuff being slapped on her wrist. The other cuff was clapped on Emily’s wrist.

“Just incase you got any bright ideas kid.”

Do you know how awkward it is to pee handcuffed to someone else? And of course the cuff was on her dominant wrist so it was harder to wipe in a tiny ass stall. Coming out of the ladies room Chase handed Emily a beer. Nora started to ask for water but they rushed out the door with a nod and “Thanks Tim” to the bartender.

Back at the car they started arguing about if she needed to be hogtied again. Emily seemed to be more lenient. And seemed to get her way. The car ride was strange... her caretakers seemed to be messing with her head. They’d go from silent abs ignoring her to telling her that they were getting married, to telling her they were sister and brother. No matter what the situation was she didn’t care she just wanted the ride to stop.

The sun began to rise as she started drifting off to sleep. Next thing she knew the door was being opened yet again. They were in front of a HUGE old building in the middle of nowhere. The building read “Mercury Ridge”. She had no clue where in the hell they had taken her. The building gave off a energy tht made her stomach turn.

They walked up to the building in unison. A guard took down their information and ushered Nora inside. She turned around to ask Emily a question, and both her and Chase had already left. The door shut behind her with a loud SLAM. The room inside held a few old chairs that looked like they were from the 80’s. You know the old fabric ones with that awful wood arms? Yeah.. those.

There was a huge reception desk and a sign that said “ authorized people only behind this point.” The man behind the counter looked like he couldn’t be bothered to even look up. He was balding and had sunglasses on indoors as if the lights over head were assaulting his senses. The guard walked her a thick metal door. There were no handles on the door. With a swift beep from inside the door swung open.

A tall broad man with thick curly hair and a darker complexion walked through, he grabbed her by the wrist and disappeared behind the doors. Inside it smelt of sweat and urine. A faint hint of bleach wafted to her nostrils. The man introduced himself as Anjelo. But it was more formality, not for conversation.

They went down a maze of hallways and doors. Every door they encountered was locked and Anjelo opened them with a badge. He finally said, “Here we are. Your new home. Girls Unit A.” Then promptly left leaving her standing there not sure what to do. A tall redhead walked up, and finally someone seemed to be able to see her.

“Hey, I’m Tasha. This is Girls A. Welcome. First we have to take you to your room and get you changed. Follow me kid.”

As she followed, faces peered out of doorways at her. None of the bedroom doorways seemed to have doors. Abs she passed a room the size of a tiny closet with the walls and floors all carpeted. There was a door on it, with a TINY window. At the end of a hallway before another set of locking doors, Tasha stopped and motioned into a doorway.

Inside were two wooden beds with matching dressers. One bed was made perfectly, the other had a set of sheets folded on it. Nora was instructed to strip, and a full body search which included a cavity search followed. She changed into scrubs the color of milky oatmeal. She want even allowed her own underwear.

“After you make your bed just hang out till we call you for group. Oh, by the way... your roommate should be back from lunch shortly. Her names Melinda.”

Holding back tears after being violated in such a manner under the guise of a search, Nora stumbled to her bed and began to make it. Her mattress ( it was less of a mattress and more of a yoga mat) smelt of bad body odor, and cheese. Laying down she began to sob. The tears stung her cheeks and she wiped them away with the backs of her hands. She inhaled deeply as the tears touched the wounds on her wrists where she had been restrained during her journey.

No! She would not let them see her break. She would get her self together and figure out where and what the fuck she was doing there.

0 notes

Text

I wanna talk @wolf359radio, specifically their incredible juxtaposition of comedy with deeper themes, and their brilliant gamble about slow-building character investment. Because this is a podcast I feared I wouldn't like, but that became my motivation to become a patron of something for the first time, well before I was finished with season 1. So I wanna dissect precisely what they're doing so right on a crafting level. Mild spoilers up through the end of EP 11 below the cut.

I don't normally like what we've come to view as comedy. Primarily because it's come to be less about brilliant comedic timing on an actor's part and more about ridiculous physical/situational slapstick almost entirely driven by external factors. So when I heard that the first few eps of Wolf 359 were mostly office shenanigans in space, my stomach rolled and I almost ignored; but I'd heard that Gabriel and Sarah were fucking geniuses (yeah; pretty much perfect advertising), and I'd been recced it by two folks, so I figured I'd dive in.

Almost instantly, I was intrigued and on alert, because Zach's comedic timing was very reminiscent of something like Girl Friday for me, which I utterly adore. The humor derived almost exclusively from the way he chose to convey the monologue. And that brilliant opening patter monologue. By the time he started talking about the pizza delivery missing his hotel by a few thousand light-years, and calling Hilbert Russian Dr. Doom, I was clapping and cackling in sheer delight. And then, when you're like oh, that was a nice comedic moment in space, they slide that ending hook of Doug possibly discovering...something into place. And it's such an intriguing little hook, because all right, this was a false alarm, but you can't always be the boy who cried wolf with your hooks. So, clearly, they're setting up for a not false alarm. And then realizing Zach played Hilbert as well; I was just floored by his range and skill. Any show that netted this versatile an actor had to be something special.

So you're set up to have high expectations from the pilot, and then Little Revolución and Discomforts, Pains, and Irregularities form this incredible duology to further your investment. There're so many shows that cram character detail into the pilot. There's a frantic rush to have you be invested, to catch your attention with anything, that it becomes throwing paint at a wall and seeing what sticks. As much as making 359 on no budget those first couple years must've been an unmitigated nightmare in a lotta ways, this was their moon shot. No expectation, no profit margin, and by God if they were going to put in the work to make the thing, you were going to have to put in a little trust and time to love it. That created this marvelous, constantly expanding canvas, with this thrumming excitement on discovering which part of the canvas they were going to shade in or fill each episode. Anyway: I digress.

Little Revolución sets up Doug's melodrama and lays the seeds for the expanding family dynamic we continue to see throughout the season in one fell swoop. After all, if Hilbert and Minkowski are engaging in an extreme prank war, they can't be the figures of unremitting dread Doug's nicknames would make them out to be. And Doug, oh Doug. Zach's comedic timing and inflection continued to be stellar there, drawing me into stitches over Doug determined to die on his foolish hill. There were so many moments where dialogue and inflection melded seamlessly, and showed just how thoroughly Gabriel and the rest of the team understood how they wanted their words to resonate with the audience, and precisely what beats an actor would need to hit to get there. I'm thinking of something like Doug's explanation of the last time he was cajoled into accepting substitutions. It is obviously written to be amusing, and Zach utterly mines that potential. Even then, I couldn't imagine anyone else as Doug.

If EP 2 was watching Minkowski and Hilbert work together and starting to see Minkowski unbend, EP 3 made me fall in love with Commander Minkowski, and much of that was the way Emma sold the comic timing. Minkowski's sheepishness at avoiding the physical! Getting that moment of humanity from her, like unlocking a puzzle. And also in the best traditions of puzzles, really starting to realize that we're in the midst of an ongoing story. That moment when Doug says that he thought she was joking about the plant monster entirely spins the story around: he expects her to joke. As much as they often infuriate one another, there's also a comradeship. And then his nicknames start to feel more like snide sibling rivalry, glorious sibling rivalry. This's further strengthened by watching them work together against the plant monster. We expected Minkowski to be competent of course; Emma's usual no-nonsense tones guarantee that even if she weren't the commander. And we *knew* Doug had to be competent. But this; this is the moment we start to see it. And there again, the juxtaposition of serious and comedic elements. That they're not afraid to raise the stakes in the midst of what should be folks skiving off a physical utterly delighted me. The authorial confidence required to seesaw like that started to reassure me I was in very. very good hands, even if some of the genres employed weren't my usual fair.

It was EPs 4 and 5 that made me determined to watch through at least the rest of the season. Cataracts and Hurricanoes alchemized my liking for Minkowski into fierce adoration. And we continued to be exposed to more and more evidence that she and Doug's relationship was as sibling-like as it could be, considering the differences in rank. This's the first EP, too, where I realized Hera was very likely to steal my heart. Her concern for Doug was so well-acted. The way all the actors were able to spin, going from Doug and Minkowski bantering one second to deeply dangerous rescue the next was astounding. While I was coming to take for granted that the writing would veer, the spot-on casting, just how much these actors were starting to embody the versatility of the writing, get comfortable and play, took my breath away.

And then came EP 6, wherein I decided yeah Gabriel was a fucking genius. Because the juxtaposition of the dire and the hilarious actually *became a plot device* He whipsawed our perceptions of Hilbert madly throughout the episode. Had Doug's melodrama about the physical--which you could easily take in EP 3 as the clash of an overeager doctor with someone who. just didn't like doctors much--foreboded something more dire? And you really start to realize how *smart* Doug is here. Not just competent, but quick on his feet. The reveal at the end was so well-done; it would have been too early, too abrupt of a tonal shift, to pull us into true chaos. But Gabriel was starting to gradually give us a taste, and use the comedy as the tether to continue to ground us within the plot. Always bringing us back, centering us, like a skillful pilot starting to fly through mild turbulence.

EP 6 confirmed my deep Hera empathy. That moment when we see her show annoyance, and Doug acknowledge her programming for the first time. We start to see the gulf between them, but also the commonality. And again, we're whipsawing just a little, very gently, on Hilbert. The way he's slowly pulling back from the comedic elements, weaning us off gradually, while never entirely losing sight of them is so clever. Both the writing and the acting really show the understanding that to endure serious narrative often requires just the right proportions of levity mixed in. And again, we started to see hints of the serialized story from EP 1 by the end of 6, hints this will be the overarching plot. The way the show becomes comfortable tossing all sorts of genre elements about makes clear that very. very good hands should be revised to excellent. And then for anyone still watching but on the fence, there's no way to stop now with the mystery hook of the odd voices.

The way comedy is used in Sound and Fury is sheer perfection. How clearly uncomfortable Doug is lying, his desperate adroitness that fools no one--and the implication he knew it would fool no one-- had me in stitches. And we needed the levity desperately there, to balance out Hera's insecurity and vulnerability. Minkowski's insults would hurt far less if she were not quite so aware of her flaws, if she had not, I suspect, become far more sentient than she was intended to be. And with that comes a very human fear of not entirely belonging, of being dispensable.

I wanna skip now to 9-11, which isn't to say that the other EPs aren't amazing; they are! but much of what they do on a structural level are things done by the previous eps.

I loved seeing the core group functioning as a core group in these last few; we'd seen dyads before, but seeing that full puzzle snap together was marvelously breathtaking. I loved Emma's use of levity at the end of EP 9, because man oh man, that's where the writing really starts to preview a tenseness that's. well, my heart was pounding, let's leave it at that. That tone Emma adopted, of trying desperately to remain the straight-laced commander, but there starting to be real fear and vulnerability there, and then her just throwing up her hands and going yeah, I'm as pissed as them. popped the bubble of the tension so perfectly. And the writing, giving Minkowski that vulnerability: it makes this show feel so rewarding, like you're peeling back character layers like onion skin. Every moment you continue to be invested in the show will reward you with some greater revelation about these people you're coming to love.

And that just continues into the last two: Hilbert's gentleness in EP 10! contrasted with Doug's melodrama over the spider, which never felt campy and felt viscerally real for someone who regularly engages in melodrama over creepy crawlies. And Minkowski, being fierce gentle mother bear again; the best of Minkowski comes to the surface when her crew is under threat. Which was a theory from EP 4, but now we have it brilliantly confirmed.

And the juxtaposition of the droll with the dangerous in EP 11 was just masterful. The way Hilbert's thoughtful, almost mournful reflections about solitude and why we still fear it and Hera's wrenching struggle with not only not being quite human but with the folks she's closest to not quite understanding it were softened by Doug's brilliantly funny psych test was just enough. Just enough to ensure that those sections resonated, that there are still lines from both of them reverberating in my head a day later, without being crushing. Which leads me to another thought: the comedic elements are a herald of 359's underlying hope imho. Even in the midst of deeply bleak things, like Minkowski reconfirming Doug's unreliability that we'd almost forgotten about from EP 5 and that now seems to be a crew unreliability oh shit! is offset by that very gentle, fiercely human wish to send her best wishes and love to someone on their name day. That's the...not gentlest we've seen Minkowski, but perhaps the softest, and it made me a little weepy.

At any rate, there're my long, disjointed thoughts on 359, and how it does the brilliant things it does, at least so far.

#Wolf 359#My Meta#oh god so much meta; this got so long#but it's so good it deserves meta on precisely what was done to achieve that goodness#Podcasts#Podcast Babbling

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

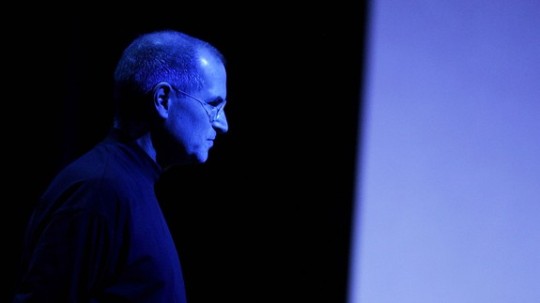

Genius or manchild? Reconsidering Steve Jobs after his daughter's book

The statement from Steve Jobs' widow arrived via email, unrequested, in the middle of Labor Day. "Lisa is part of our family, so it was with sadness that we read her book," it began, the "we" referring to Laurene Powell Jobs and her sister-in-law, the novelist Mona Simpson. "The portrayal of Steve is not the husband and father we knew," it continued. "Steve loved Lisa, and he regretted that he was not the father he should have been during her early childhood."

It's what any PR expert would call "getting ahead of the story" — the story being Small Fry, an autobiography by the Apple founder's first child Lisa Brennan-Jobs, daughter of Christine Brennan, which was released the next day. Never mind that Lisa was technically part of Steve's family circle before either Laurene or Mona (younger birth sister to Steve, who was put up for adoption). If you get your riposte in first, the advice goes, you control the narrative.

SEE ALSO: Lisa Brennan-Jobs shares tangled memories of her imperfect father, Steve Jobs

But as any journalist would tell you, it's the kind of statement that gets our spidey senses twitching, more for what it wasn't saying than what it was. It didn't refute any specific allegation in Brennan-Jobs' book. It didn't have anything to say about Powell Jobs telling Lisa "We're just cold people," or her regret that she married Jobs too young, or any one of a dozen scenes in which she does little to prevent her husband's controlling, heartbreaking, manchild-like behavior toward her stepdaughter.

As I discovered when I sped-read the thing so you don't have to, the statement had nothing on the book. Small Fry recounts simple scenes in Lisa's life in an unhurried fashion, with a novelist's eye for detail. (She openly admires her author aunt Mona, even after Mona writes a fictional version of Lisa's life without asking.) In contrast with most tell-all autobiographies, this one actually suspends authorial judgment.

What a relief that is, especially in 2018. Lisa Brennan-Jobs is the anti-Omarosa. Her book is an even-handed, surprisingly poetic, quietly devastating record of the witness that she bore, and is now sharing with us.

This testimony will make most readers think differently about Jobs. And in the age of Trump and #MeToo, Small Fry is another good example of why we should stop forgiving or enabling powerful men who act like assholes toward women and refuse to grow up.

"You get nothing!"

From an extract in Vanity Fair and an interview in the New York Times, we already knew a few of Small Fry's more shocking moments. Jobs bullied and gaslighted his daughter throughout her childhood — at first denying his paternity and child support payments, then repeatedly denying that he named the Apple Lisa computer after her. The lie tortured Brennan-Jobs until Bono, of all people, made him 'fess up.

But the shock of the big stuff is nothing compared to the accumulation of small details, through which you feel you're living Lisa's childhood and teenage years. She went to live with her father and Powell-Jobs during middle and high school, on condition that she stop seeing her mother. Her self-doubt and loneliness are painfully, almost claustrophobically real. She develops a tic where she can't control her hands, and breaks many glasses. She feels unable to breathe when her father pays her attention or affection. (More often he didn't, even point-blank refusing to swing by her room and say goodnight to her.)

Stuck in a cold bedroom because Jobs wouldn't fix the heat, made to wash all the dishes because he wouldn't fix the dishwasher (in high school, Lisa finally called a repair guy herself), babysitting her young half-brother whenever Laurene and Steve wanted her to, she comes across as a real-life Harry Potter — or, as she thought of herself at the time, Cinderella.

Brennan-Jobs' self-awareness in shaping her story is part of what makes her seem a reliable witness. "I was both the one hurt and the narrator of the hurt," she writes after telling a neighborhood boy her Cinderella story. "I would learn which complaints worked and which ones didn't trigger much sympathy in others."

Fundamentally, however, she is guileless and straightforward. She's lonely, she tells her father again and again. Even with a therapist sitting right there with them, it elicits no response.

Brennan-Jobs' mother almost comes off worse than Jobs. A wannabe artist who drifted from hippie boyfriend to hippie boyfriend, Christine openly admitted — usually with screaming and swearing — that she wasn't up to the task of motherhood. One time this happened when she was behind the wheel of a car. Brennan-Jobs stayed as quiet as possible, praying to a crack in the windscreen to keep them safe as her mother swerved across the road.

Lisa was lost, confused, and yearned for a connection with her remote, famous dad. But he blew up at her more often than he charmed her with trampolines and roller skate outings. "You get nothing!" he screamed at her when she asked for one of his many discarded Porsches. He became mad at wealthy neighbors who paid her way through college when he refused to do so. He made Lisa's friends cry with his insults, and he verbally assaulted waitresses while Mona and Laurene sat by, silently.

Then there's the sex stuff, which ... if it doesn't cross a line, it sidles right up to it. According to Lisa, he liked to point out to his child daughter that the Stanford tower "looks like a penis," and repeatedly told a story about a friend masturbating while watching Ingrid Bergman sunbathe. He draws his daughter a bath and later tells her she should masturbate.

And in the book's ickiest scene, he made Lisa watch as he began practically simulating sex with her stepmother, Powell Jobs. (He did much the same thing with his previous girlfriend, a woman named Tina, whom he later regrets leaving for Powell Jobs; Tina tells Brennan-Jobs that such ostentatious making out "was what he did when he felt uncomfortable.")

If I was Powell Jobs, I wouldn't want to remember my spouse that way, either. But we all have different memories of the dearly departed, especially when it comes to someone as mercurial as Jobs.

The child inside

I interviewed Jobs around a dozen times in the 2000s, when Apple was still just another tech company, before the iPhone secured his legacy. His tactics during an interview largely consisted of telling the reporter why their questions were "stupid." If you could withstand 20 minutes of this behavior, or if you started to use reverse psychology to get good quotes out of him, he'd suddenly smile: You were okay, you got it, you were in the club.

The other compelling memory I have of Jobs is him leaving a restaurant in Palo Alto. In jean shorts and a black T-shirt, with a plastic takeout bag in one hand, he idly made airplane shapes with his arms as he walked down the street. Exactly like a child.

The hectoring, reality-controlling Jobs that Brennan-Jobs writes about feels like one of the most true depictions we have. People longed to be drawn into his orbit for the good moments, the flashes of brilliance or mere attention, for which they slogged through the bad.

But maybe that isn't good enough any more. Maybe "Time's Up" not just in Hollywood, but also in the tech world. Maybe we need to stop spreading the lie that genius can only come from jerks.

In his 2012 authorized biography of Jobs, Walter Isaacson spends a lot of time considering this question: Would the Apple founder still have been a great man with a legacy of killer products if he hadn't been so cruel to his employees? If he hadn't become a millionaire in his mid-twenties? Did parking his Porsches in the disabled spots for his entire career make the iPhone happen any faster? What if he hadn't quit Apple in a snit in 1985? If he hadn't spent a decade down the rabbit hole of his failed next company, NeXT, might the modern world have arrived a little earlier?

What if he'd used his powers to motivate and inspire people with sternness, but also with love?

Brennan-Jobs tells how her father used to carry a picture of her around in his wallet, denying she was his kid even as he showed her off to others as the kid of a friend he was helping out. "He loves you," her mother said. "He just doesn't know that he loves you." It took the emotionally stunted Jobs a long time to learn what love meant. We can speculate on the reasons why, and to what extent his adoption had anything to do with it; we can also speculate whether that's just making excuses for behavior that was clearly abnormal.

At the very end of his life he apparently knew it: He cried and apologized on his deathbed, Brennan-Jobs tells us. He repeated the words "I owe you one" over and over. It's practically the textbook definition of "too late."

She has forgiven him, and the book ultimately leaves any questions of worldly remedies to the reader. But the final pages do contain the closest thing we get in this non-judgmental book to a judgment on her turbulent father (emphasis mine):

This is on all of us as a society, but men especially. We should stop giving our fellow men license to be jerks — for the sake of everyone around them, for the victims like Lisa, but also for their own sake. The more that men in positions of authority act poorly, the more they're missing out.

See Steve Jobs through his daughter's eyes and you're left with a profound sense of pity. He was a genius who didn't get what the whole family thing is supposed to be about, and he acted horribly. Nobody dared call him out for being a brat. In the future, when public figures and business leaders behave this way, we need to be less afraid of shining a spotlight on this behavior as it's happening.

Or as Jobs itself might put it, we need to learn to think different.

WATCH: Elon Musk opens up about the toll Tesla takes on him

#_author:Chris Taylor#_category:yct:001000002#_uuid:a425c0c7-193e-3556-977d-bfc2468f5eba#_lmsid:a0Vd000000DTrEpEAL#_revsp:news.mashable

0 notes