#John Goodenough

Text

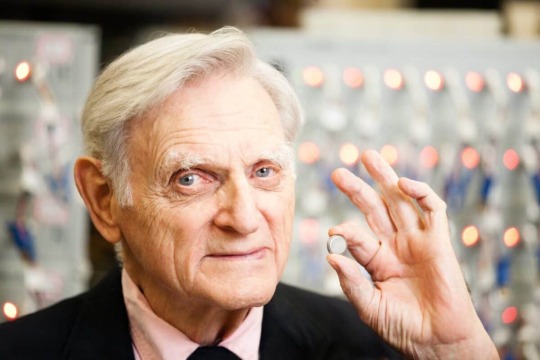

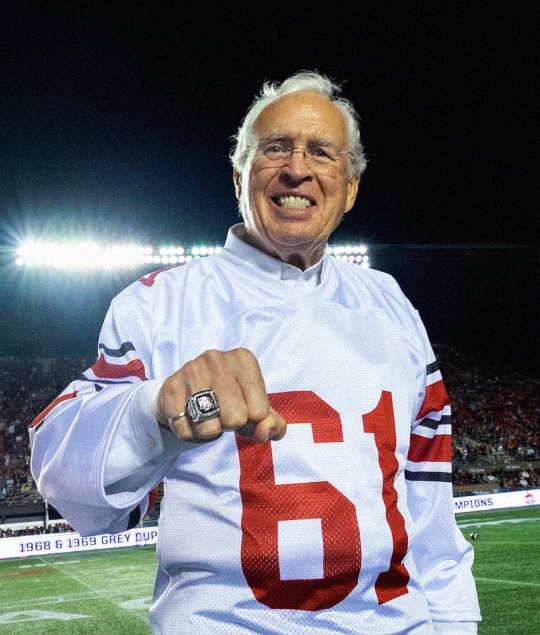

Alfred Nobel stipulated that his annual prizes be awarded to those who “have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind”. Few scientific advances have had a greater impact on our lives than that made by the American materials chemist John Goodenough, a chemistry Nobel laureate in 2019 for his role in inventing the rechargeable lithium battery.

If you are reading this on a handheld device, it will almost certainly have a lithium battery inside. These power packs have been instrumental to the advent of electric cars, and their ability to store power such as that generated by ephemeral renewable sources could aid the transition away from a fossil-fuel energy economy.

For year after year Goodenough, who has died aged 100, featured in the list of Nobel predictions. Only his remarkable longevity saved the Swedish committee from an embarrassing injustice – he is the oldest person to have been awarded a Nobel. He seemed phlegmatic about being repeatedly overlooked, even though he did not enjoy any financial reward for his breakthrough either: in the 1980s he was not encouraged to take out a patent on the battery breakthrough he made at Oxford University. He was glad enough still to be able to do research, which he sustained almost until the very end of his life.

He left Oxford in 1986 for the University of Texas at Austin to escape compulsory retirement at 65, convinced – rightly – that he had a lot more still to offer. “Why would anyone retire and simply wait to die?” he asked. His vitality and enjoyment in the lab well into his 90s, punctuated by his loud and high-pitched laugh, was a constant cause of amazement.

One would hardly have guessed from that demeanour how unhappy his childhood had been, as the second of three children of extremely distant parents in what he called “a disaster” of a marriage. He was born in the city of Jena, Germany, to Helen (nee Lewis) and Erwin Goodenough.

They were both Americans who were living in Oxford – Erwin was studying for a DPhil at the university and, according to his son, “enjoyed the culture of the Weimar Republic; he spent much of his long summer vacations in Germany as well as in Rome”.

John was taken as a baby to the US, where his father became a professor of religious history at Yale University. John grew up mostly in a boarding school in Massachusetts, from where, despite being an undiagnosed dyslexic, he won a place to study mathematics at Yale. After wartime military service as a meteorologist, he gained a doctorate in physics at the University of Chicago and in 1952 began research on magnetic materials for information storage at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

That work qualified him to switch to inorganic materials chemistry when in 1976 he moved to Oxford. At that time, interest was growing in electric vehicles, which were being held back by the lack of suitable batteries.

The potential benefits of electric cars as quieter and less polluting than those using the petrol-fired internal combustion engine had been recognised since their inception. But the lead-acid batteries used as starter batteries and the power source for vehicle electronics were utterly unequal to the task of supplying the motive power: they were too heavy and offered too little power.

The dream of battery-powered cars was resurrected in the 60s, but it was only a decade later, with the Opec oil crisis in full swing, that the industry took them seriously.

The key was to find the right materials for the battery electrodes. Lithium metal looked attractive because it is lightweight and capable of delivering high voltages. The idea was that lithium at the positive electrode would provide electrically charged ions that travel to the negative electrode, where they could be trapped between the layers of atoms in materials called intercalators.

The British chemist Stanley Whittingham, one of Goodenough’s co-laureates, working at the Exxon laboratories in New Jersey, found a suitable intercalator called titanium disulfide in 1976. Four years later, Goodenough in Oxford identified the material – a form of cobalt oxide – that became the industry standard, offering a higher voltage and greater power density.

Early lithium batteries had a tendency to catch fire because of the high chemical reactivity of pure lithium. But the third 2019 laureate, the Japanese researcher Akira Yoshino, of the Asahi Kasei Corporation in Tokyo, replaced lithium electrodes with graphite-like carbon made from petroleum coke, which also intercalates lithium so that the ions merely shuttle back and forth between the two sets of layers, making them easily rechargeable.

The lithium-ion battery was commercialised in 1991 by the Sony Corporation, and now commands an estimated $92bn market. Without it there could have been none of today’s handheld electronics – laptops, smartphones, tablets. Elon Musk’s Tesla electric cars depend on them.

There is still room for improvement and Goodenough never stopped seeking it. In the past decade he was working, among other things, on making batteries that operate at low temperatures, suitable for powering cars in the winter.

He was also seeking a new, safer way to reinstate pure lithium electrodes, which could give lithium batteries more energy capacity. At the same time, he expressed concerns about the international tensions that might arise over the limited global supplies of lithium.

Goodenough maintained a strong Christian belief throughout his life, seeing no conflict with his scientific work. “The scientist is trying to do something for society and for his fellow man,” he said. “In that sense why should there be a conflict?” During his 90s he cared for his wife, Irene (nee Wiseman), who had Alzheimer’s disease. They had married in 1951; she died in 2016.

“I’d like to get all the gas emissions off the highways of the world”, Goodenough said in 2018. “I’m hoping to see it before I die.” It was always an ambitious aspiration, even for someone with his staying power. But if it happens one day, Goodenough will have played a central part in that.

🔔 John Bannister Goodenough, materials scientist, born 25 July 1922; died 25 June 2023

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at http://justforbooks.tumblr.com

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

John Goodenough, investigador y pionero de las baterías, murió a la edad de 100 años

John Goodenough, investigador pionero que ayudó a transformar las baterías de iones de litio, falleció el domingo a los 100 años.

Sus inventos, que ayudaron a desarrollar los ordenadores modernos y a comercializar las baterías de iones de litio, afectaron a la vida de todos los habitantes del planeta. Sin embargo, pocos le conocían y su trabajo no le reportó riquezas, aunque sí le valió un…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

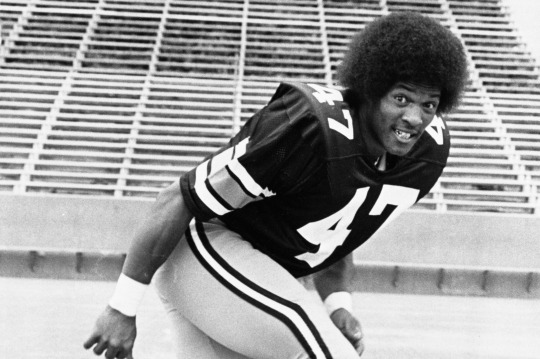

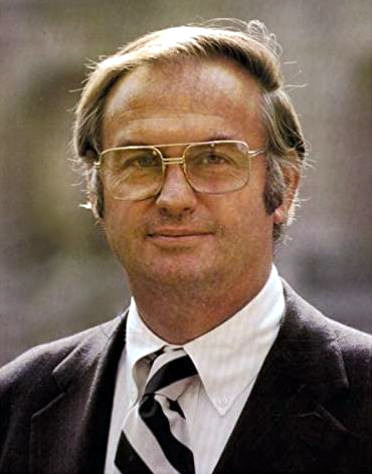

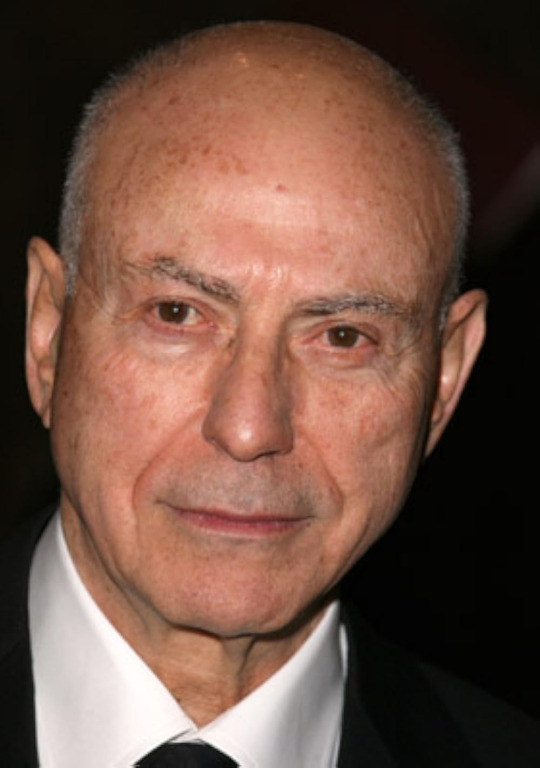

look guys it's him, it's mr. goodenough

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

if you ever need a fun fact at some social engagement, may i present you with the fact that the guy who invented the lithium-ion battery was named john b goodenough, also he won a nobel prize, lived to a 100 years old and the b stands for bannister

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lithium-Ion बैटरी निर्माता वैज्ञानिक जॉन बी गुडएनफ का 100 वर्ष की आयु में निधन

New York: उम्रदराज नोबेल पुरस्कार विजेता और लिथियम-आयन बैटरी के निर्माता वैज्ञानिक प्रोफेसर जॉन बी गुडएनफ का टेक्सास के ऑस्टिन में रविवार को निधन हो गया। उन्होंने 100 वर्ष की आयु में दुनिया को अलविदा कहा। यह जानकारी टेक्सास विश्वविद्यालय ने दी। इस विश्वविद्यालय में वह इंजीनियरिंग के प्रोफेसर रहे हैं।

प्रो. जॉन बी गुडएनफ को अभूतपूर्व लिथियम-आयन बैटरी, रिचार्जेबल पावर स्रोत के निर्माण में…

View On WordPress

#died on Sunday in Austin#Professor John B. Goodenough#Texas.#the oldest Nobel laureate and inventor of the lithium-ion battery

0 notes

Note

what are your thoughts on theology and climate change issues? any book recommendations on that?

ecotheology centers god's creative genesaic movement, and it matters. in my work, this means making visible animacy, sacrificial/levitical bodies, and the bodyscape's extension into and across materiality, in the ancient near east. so i recommend, in particular, neumann's handbook of senses in ane, freud's totem and taboo, adegbite's life under the baobab tree, shellenberg's sounding sensory profiles in the ane, kim's bodies, embodiment and theology of the hb , and hsu's expression of emotions in ancient egypt and mesopotamia.

but it's more likely you want christian ecotheology, or contemporary ecotheology. sally mcfague, ursula goodenough, ibrahim abdul-matin, s. lily mendoza and george zachariah, mary evelyn tucker and john grim, melanie harris

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

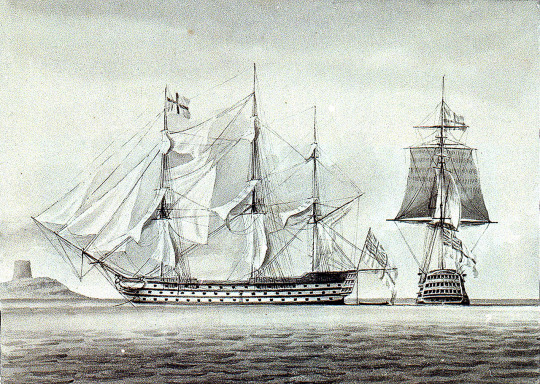

HMS Excellent, 108 Guns, 1834–1835 (Art UK). The former first-rate line of battle ship served as a gunnery training school for decades of Royal Navy midshipmen.

Like his eighteenth-century counterpart, the early Victorian naval instructor does not seem to have featured prominently in the histories of the period, although he occasionally appears in biographies and memoirs and is invariably remembered with affection. Commodore J G Goodenough was taught by Naval Instructor William Johnstone, 'a man of cultivation and ability who possessed the rare talent of not only teaching well but of inspiring his pupils with interest in and liking for their studies'. Admiral John Moresby related brief details of his studies on board the gunnery ship HMS Excellent in 1849 where, 'under the poop was the mathematical study for all officers and here a menagerie of diverse pupils confronted dear old Stark, our Scottish instructor'. He also served in HMS Caledonia under the tuition of 'the most lovable of naval instructors' Michael Rainback, a man much admired and teased by his pupils and 'who might have served Dickens for the original of Mr Pickwick'.

— H. W. Dickinson, Educating the Royal Navy: Eighteenth- and

Nineteenth-Century Education for Officers

HMS Caledonia (1808) in two positions, by William Innes Pocock (NMM). This first-rate ship also had a secondary career, renamed Dreadnought and converted to a hospital ship in 1856.

#midshipman monday#age of sail#naval history#royal navy#hms excellent#hms caledonia#midshipmen#education#military history#educating the royal navy#victorians#victorian era#early victorian era

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

John B. Goodenough, 100, Dies; Nobel-Winning Creator of the Lithium-Ion Battery

He was, he said in a memoir, “Witness to Grace” (2008), the unwanted child of an agnostic Yale University professor of religion and a mother with whom he never bonded. Friendless except for three siblings, a family dog and a maid, he grew up lonely and dyslexic in an emotionally distant household. He was sent to a private boarding school at 12 and rarely heard from his parents.

With patience,…

View On WordPress

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

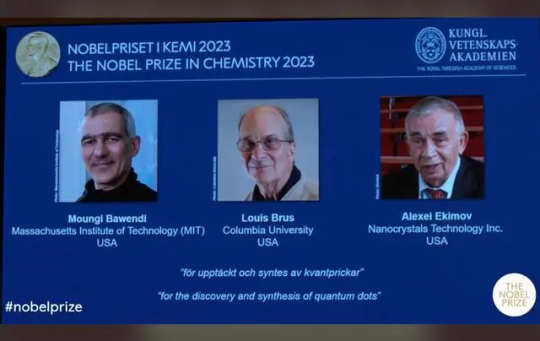

2023年诺贝尔化学奖揭晓,美国三位科学家获奖

2023年诺贝尔化学奖获得者:

北京时间10月4日17时45分许,在瑞典首都斯德哥尔摩,瑞典皇家科学院宣布,将2023年诺贝尔化学奖授予美国麻省理工学院教授蒙吉·G·巴文迪(Moungi G. Bawendi)、美国哥伦比亚大学教授路易斯·E·布鲁斯(Louis E. Brus)和美国纳米晶体科技公司科学家阿列克谢·伊基莫夫(Alexey I. Ekimov),以表彰他们在量子点的发现和发展方面的贡献。

2023年每项诺贝尔奖的奖金由去年的1000万瑞典克朗,增加到1100万瑞典克朗,约合人民币725万元。

化学奖是瑞典化学家、硝化甘油炸药发明人阿尔弗雷德·伯恩哈德·诺贝尔(Alfred Bernhard Nobel)在遗嘱中提到的设立奖项的研究领域之一。

“上述利息应分为五等份,分配如下:/- - -/一份给做出最重要的化学发现或改进的人……”1895年11月27日,诺贝尔在巴黎签署了他的第三份,也是最后一份遗嘱,将他留下了大部分财富用于设立一系列奖项,即诺贝尔奖。

1901年首次颁发的诺贝尔奖奖章。图:Alexander Mahmoud

据诺贝尔奖官网(www.nobelprize.org)公布的数据,1901年至2022年间,共有189 人获得诺贝尔化学奖。

迄今为止最年长的诺贝尔化学奖获得者是美国物理学家约翰·B·古迪纳夫(John B. Goodenough)。他在 2019 年获得化学奖时已经97岁了。他也是诺贝尔奖所有奖项类别中最年长的获奖者。

迄今为止,最年轻的诺贝尔化学奖获得者是法国物理学家弗雷德里克·约里奥( Frédéric Joliot)。与妻子艾琳·约里奥-居里(Irène Joliot-Curie)一同在1935年获得诺贝尔化学奖时,他年仅35岁。

英国生物化学家弗雷德里克·桑格(Frederick Sanger)和美国化学家巴里·夏普莱斯(K. Barry Sharpless)都曾两次获得诺贝尔化学奖。

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

aw dude john goodenough died that sucks

salutations man. your batteries were good enough to encircle the world

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

As conquistas do Dr. John Goodenough não se limitam às baterias

(foto: Universidade do Texas em Austin) O Dr. John Goodenough, criador das baterias de íon-lítio, morreu aos 100 anos, anunciou a Universidade do Texas em Austin (EUA). Baterias desse tipo são amplamente utilizadas em smartphones, laptops e veículos elétricos. Os cientistas pesquisam baterias de lítio há muito tempo, mas apenas o Dr. Goodenough fez uma grande descoberta. Em 1980, na Universidade de Oxford, desenvolveu um cátodo com camadas de óxido de lítio e cobalto, que ajudava a fornecer alta tensão e um nível aceitável de segurança. O novo tipo de bateria acabou por ter uma capacidade superior às suas antecessoras, a bateria de chumbo-ácido (que continua a ser utilizada nos automóveis) e a bateria de níquel-cádmio (utilizada em eletrónica portátil). A tecnologia não ganhou terreno até que o Dr. Akira Yoshino substituiu o lítio bruto por íons mais seguros. Ele construiu um novo tipo de bateria para a Asahi Kasei Corporation, e a Sony iniciou a produção em massa delas em 1991. Como resultado, tornou-se possível criar telefones e laptops menores com bateria de maior duração, veículos elétricos também se tornaram uma realidade. As contribuições do Dr. Goodenough não se limitam às baterias. Durante seu tempo no Instituto de Tecnologia de Massachusetts, ele participou do desenvolvimento da tecnologia de memória RAM para computadores. O professor continuou trabalhando até os 90 anos, dedicando seus últimos anos a uma nova geração de tecnologia de baterias que promete um avanço no campo de fontes de energia renováveis e transporte elétrico. Em amplos círculos, o nome do Dr. Goodenough permanece pouco conhecido, mas seus méritos foram reconhecidos por inúmeros prêmios, incluindo o Prêmio Nobel de Química em 2019. Em alguns anos, os fabricantes de automóveis planejam eliminar gradualmente a tecnologia de baterias de íons de lítio em favor de baterias de estado sólido mais maiores, mais potentes e mais seguras.

0 notes

Text

2023 In Memoriam Part 26

(William) Lee Rauch, 58

Betta St. John, 93

Dahrran Diedrick, 44

(Finis) Dean Smith, 91

2Lt. Raymond Cassignol, 102

Rowena Heath, 96

Wilhelm Büsing, 102

James Crown, 70

Prof. John B. Goodenough, 100

Leo Insam, 48

Bishop François Thibodeau, 83

Tony Bouza, 94

Prof. R.B. Bernstein, 67

Tom Beynon, 81

Nicolas Coster, 89

Rob Palmer, 66

Scott Pelleur, 64

Vladimir Sedov; Jr., 35

Mike Spivey, 69

Ryan Mallett, 35

María García aka Carmen Sevilla, 92

Joana Brito, 76

P. Chitran Namboodirippad, 103

Bobby Osborne, 91

Lowell Weicker; Jr., 92

(Willie) Christine Farris, 95

Marvin Kitman, 93

Alan Arkin, 89

Tassanee Bunyagupta, 100

Mohammad Ali, 29

Berendina Ballintijn, 100

#Religion#Tributes#Celebrities#Music#Ohio#Movies#U.K.#Sports#Football#Jamaica#Canada#Ontario#Races#Texas#Planes#Haiti#Florida#TV Shows#Washington#Animals#Germany#Money#Illinois#Colorado#Hockey#Italy#Spain#Minnesota#New York#New York City

0 notes

Text

Máme alternativu k lithium-iontovým bateriím?

V diskuzích k těžbě lithia se často objevují vědoucí komentáře: “Lithium je zbytečné, protože pokrok jde dál. Vždyť jsou k dispozici i články na bázi sodíku!” Jak to je doopravdy?

Nezbytné elektrochemické minimum

Abychom mohli na otázku v titulku odpovědět opravdu komplexně, je třeba úplně základní uvedení do elektrochemie: odpusťte mi to a přijměte to s trpělivostí, prosím.

Okřídlenou historku o italském lékaři Luigim Galvanim, kterému se cukala žabí stehýnka, pravděpodobně znáte. Galvani pohyb přisoudil živočišné elektřině; ve skutečnosti proud elektronů přecházel mezi zinkovými svorkami a měděným drátem. Zinek (jako neušlechtilý kov) se chtěl oxidovat (tedy: zbavit elektronů), měď naopak redukovat. Galvani to jen popsal, ale nerozuměl tomu; to se povedlo až mladému Alexandru Humboldtovi (tu scénu čtivě - až hororově - zachycuje v jedné kapitole románu Vyměřování světa Daniel Kehlmann, vřele doporučuji kliknout na odkaz). Zinek s mědí tvoří elektrody tzv. Daniellova článku, jeho napětí je asi 1,1 V a v návodech k pokusům pro mladší školní věk ho najdete obvykle pod názvem např. “ovocná baterie” (zapíchnete plíšek z mědi a zinku třeba do citronu a pociťte na jazyku ránu; o to ovoce pochopitelně vůbec nejde, citronová šťáva tam funguje jako elektrolyt).

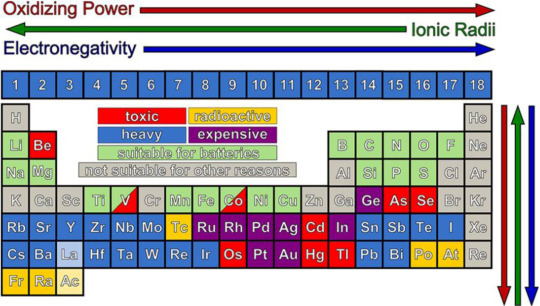

Dnes říkáme, že zinek má nižší standardní redukční potenciál než měď. “Chemické nepřátelství kovů” - rozdíl v potenciálech - je napětí, které může průchod elektronů mezi oběma kovy (elektrodami) přinést. Lithium má z celé periodické tabulky standardní redukční potenciál úplně nejnižší, konkrétně -3,04 V. Račte se sami přesvědčit v tabulce. A teď už můžeme na baterie.

Požadavky na skvělou baterii

Budete-li vynalézat nový typ baterie, musíte při hledání kovů pro jeho elektrody vzít v úvahu následující podmínky:

Co nejnižší standardní redukční potenciál (aby baterie dávala slušné napětí, potřebujete nějaký málo ušlechtilý kov s hodně zápornou hodnotou potenciálu)

Co nejvyšší kapacita (obvykle vztažená vůči hmotnosti)

Netoxicita

Vysoký počet nabíjecích cyklů

Ekonomická, technologická a politická dostupnost (máme to kde získat? je tam stabilní režim?).

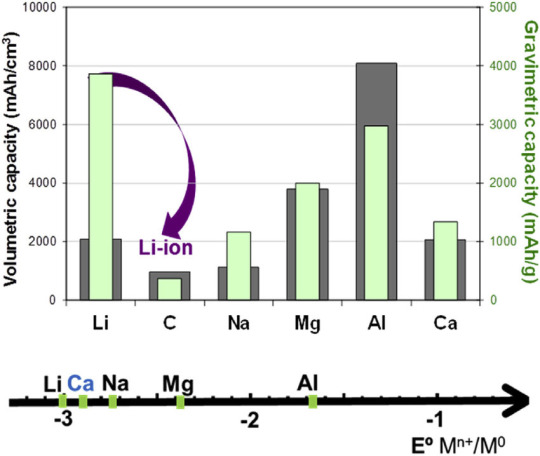

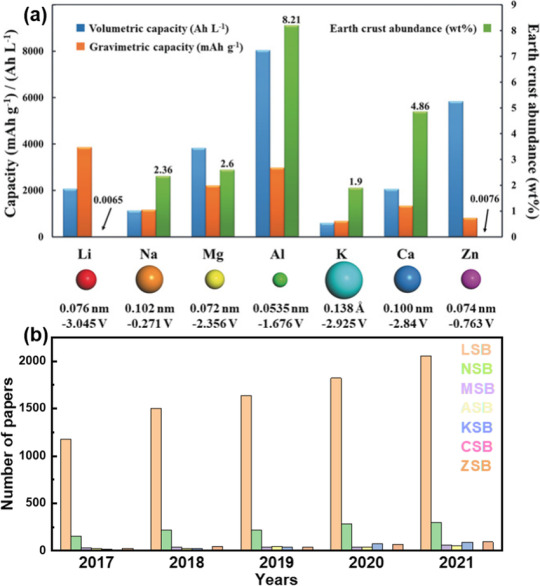

Podívejte se na tuhle tabulku (zdroj):

Tady je vidět, že ty nejlepší možnosti už jsme vyzkoušeli: Když pomineme toxické, drahé a těžké kovy, moc nám toho nezbývá. Z uvedených prvků má nejnižší standardní potenciál právě lithium.

Porovnáme-li lithium s jeho nejbližším příbuzným sodíkem na druhém grafu, vidíme, že jeho gravimetrická kapacita je asi 3x vyšší. Třetí graf (zdroj) ukazuje to stejné, přidává ale ekonomický a geografický aspekt: Zatímco zdroje lithia jsou rozmístěny nepravidelně a není jich mnoho, o sodíku (resp. sodných iontech) to neplatí.

Chceme-li tedy procházet jen potenciálně konkurenceschopné varianty, stačí prozkoumat jen několika málo případů.

“Dostatečně dobré” baterie

Otcem (prakticky ve všech významech toho slova) moderních baterií je John B. Goodenough (1922-2023), nositel řady ocenění, včetně Nobelovy ceny za chemii z roku 2019. Vedle mnoha jiných významných objevů má na svém kontě i lithium-iontové baterie. Z výše uvedeného je zřejmé, proč Goodehough sáhl právě po lithiu. V závěru života (v 94 letech!) publikoval objev nového typu článku, tzv. skleněné baterie. Mezitím se ale začaly objevovat baterie sodík-iontové. Pojďme se podívat na jednu po druhé.

Lithium-iontové baterie

Goodenough vymyslel několik baterií na bázi lithia. Nejčastěji se vyrábějí lithium polymerové baterie (elektrolytem je polymerní gel) s LiCoO katodou a grafitovou anodou, anebo s fosforečnanen lithno-železnatým LiFePO4, v elektromobilové branži označovaném jako LFP), případně s lithiem a oxidy manganu nebo LiNiMnCoO2. Kromě lithia takové baterie tedy obsahují i další kovy, jako je nikl, kobalt, nebo mangan.

Česká inovace

Baterie HE3DA je vynález Čecha Jana Procházky, se kterým se snaží prosadit někdy od roku 2010. Opět jde o Li-ion baterii, rozdíl je v konstrukci; to má přinést až dvojnásobnou hustotu skladované energie.

Baterie se od roku 2020 vyrábějí; podnik má ale podle průběžných mediálních zpráv problémy. Pro naši otázku (“Máme alternativu k Li-ion bateriím?”) je technologie HE3DA pořád je Li-ion baterií.

Sodík-iontové baterie

Zásadní inovací, o níž se hovoří, jsou Li-ionkám analogické sodík-iontové články. Hlavní výhodou je dostupnost sodíku, vyrobitelného třeba elektrolýzou chloridu sodného (kuchyňské soli). Nevýhodou má být nižší energetická hustota (tedy vyšší hmotnost baterie, kterou je třeba do elektromobilu/kola dát) a nižší počet nabíjecích cyklů, tedy nižší životnost. Oběma parametry Na-ion tedy proti Li-ion neobstojí. Pro stacionární ukládání elektřiny, kde nevadí vysoká hmotnost (třeba přebytky z domácí fotovoltaiky) by nový typ mohl být vhodný; u aut bude výhodnější Li-ion. V konkrétních číslech: Na-ion má dosahovat 160 Wh/kg, zatím Li-ion běžně dosahuje 200-300 Wh/kg; výše zmíněná HE3DA deklaruje cca dvojnásobek.

Technologie je relativně nová a málo vyzkoušená. Po internetu proto koluje řada informací, obvykle nadšených: Zejména čínská produkce hlásí nastupující boom a velké ambice ve věci odstranění výše zmíněných nedostatků. Za projekty stojí velké čínské automobilky, které jsou na dodávkách lithných surovin z Austrálie a Jižní Ameriky závislé a stejně jako Evropa hledají cestu k surovinové soběstačnosti. Jestli jsou výhledy na 70% cenu (někdy ale taky jen čtvrtinovou) a zároveň srovnatelné technické parametry reálné, zatím nelze posoudit. I v přejících textech se píše o neúplných dodavatelských řetězcích a problémech, které výrobu podle všeho potkají.

V Evropě se Na-ionkám v průmyslovém měřítku věnuje jen švédský Northvolt, v Kalifornii výrobu chystá Natron (více na webu firmy). Informaci, že čínský investor staví na Slovensku gigafactory k produkci sodík-iontových baterií, nelze ověřit. Z veřejných zdrojů vyplývá, že podnik bude vyrábět klasické Li-ion akumulátory.

Skleněné baterie

Posledním typem je tzv. skleněná baterie, za níž opět stojí John Goodeough. Její elektrody jsou opět z alkalického kovu (tedy, zase z lithia nebo sodíku), sklo má funkci elektrolytu. O efektivitě se vedou debaty; pro zodpovězení naší otázky ale stačí tvrzení, že se opět jedná o upravenou Na-ion, resp. Li-ion baterii.

Nenahraditelné lithium? Jak kde

Nelze vyloučit, že v budoucnu lidé vynaleznou zcela jiný typ baterie; s dosavadním poznáním to ale není pravděpodobné. Jak vidíme i na zmíněných inovacích, prakticky vždycky se jedná o konstrukční (HE3DA) nebo chemické (Na-ion) alternativy k Li-iontovým bateriím.

Sodík-iontové baterie si umím dobře představit pro domácí přebytky elektřiny z fotovoltaiky; vzhledem k nižšímu počtu nabíjecích cyklů ale bude ekologičtější i ekonomičtější vyrobenou elektřinu rovnou spotřebovat nebo prodat, například prostřednictvím smart-grids, komunitního sdílení elektřiny nebo jinak.

V automobilech (elektrokolech, koloběžkách ad.), kde každá zátěž navíc zvyšuje provozní náklady, je lithium špatně nahraditelné. Pokud chceme šetřit lithiem, ideální je, když budeme vyrábět méně aut (jak upozorňuje třeba Asociace pro mezinárodní otázky).

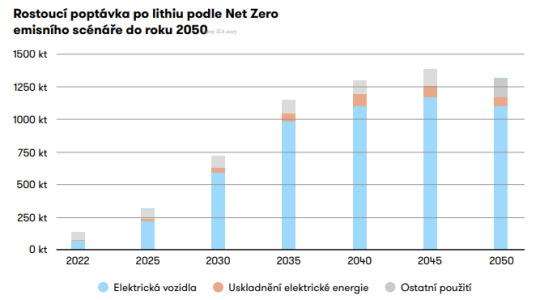

Výstižně to shrnuje predikce International Energy Agency, který do grafu zpracoval Jaroslav Kopřiva z AMO: Majorita poptávky po lithiu je způsobena očekávanou poptávkou po elektromobilech.

Bez lithia se tedy - při zachování dosaženého standardu a zároveň žádané dekarbonizaci ekonomiky - v dopravě neobejdeme. To ovšem není generální argument pro jeho těžbu za jakoukoli cenu.

Ke studiu:

HOUSECROFT, Catherine E. a SHARPE, A. G. Anorganická chemie. Přeložil David SEDMIDUBSKÝ, přeložil Ondřej BENEŠ, přeložil Karel HANDLÍŘ, přeložil Petr HOLZHAUSER, přeložil Irena HOSKOVCOVÁ, přeložil Jaroslava KALOUSOVÁ, přeložil Jan KOTEK, přeložil Václav SLOVÁK, přeložil Jarmila ŠPIRKOVÁ, přeložil Miroslav VLČEK. Praha: Vysoká škola chemicko-technologická v Praze, 2014. ISBN 978-80-7080-872-6.

0 notes

Text

Antonio Velardo shares: Notable Deaths 2023: Science and Technology by Unknown Author

By Unknown Author

Remembering Gordon E. Moore, Paul Berg, Harald zur Hausen, Ian Wilmut, Virginia Norwood, John B. Goodenough, Susan Love, K. Alex Müller, Ferid Murad, William A. Wulf, Roland Griffiths, Kevin Mitnick, John Warnock, Luiz Barroso and many others who died in 2023.

Published: December 18, 2023 at 11:37AM

from NYT Obituaries https://ift.tt/pg59U1W

via IFTTT

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

John Bannister Goodenough Miterfinder der Lithium-Ionen-Batterie ist verstorben

John Bannister Goodenough ist der Miterfinder der Lithium-Ionen-Batterie und stammt gebürtig aus Jena in Thüringen. Er zählt zu den wichtigsten Pionieren im Bereich der Akkuforschung und -entwicklung. John Bannister Goodenough wurde am 25. Juli 1922 als Sohn amerikanischer Eltern geboren. Nun starb er als einer der wichtigsten Köpfe hinter dem Lithium-Ionen-Akku im Alter von 100 Jahren am 25.…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Happy Fall!

Afterlife by Julia Alvarez

Antonia Vega, the immigrant writer at the center of Afterlife, has had the rug pulled out from under her. She has just retired from the college where she taught English when her beloved husband, Sam, suddenly dies. And then more jolts: her bighearted but unstable sister disappears, and Antonia returns home one evening to find a pregnant, undocumented teenager on her doorstep. Antonia has always sought direction in the literature she loves - lines from her favorite authors play in her head like a soundtrack - but now she finds that the world demands more of her than words.

Afterlife is a compact, nimble, and sharply droll novel. Set in this political moment of tribalism and distrust, it asks: What do we owe those in crisis in our families, including - maybe especially - members of our human family? How do we live in a broken world without losing faith in one another or ourselves? And how do we stay true to those glorious souls we have lost?

At the Edge of the Orchard by Tracy Chevalier

1838: James and Sadie Goodenough have settled where their wagon got stuck - in the muddy, stagnant swamps of northwest Ohio. They and their five children work relentlessly to tame their patch of land, buying saplings from a local tree man known as John Appleseed so they can cultivate the fifty apple trees required to stake their claim on the property. But the orchard they plant sows the seeds of a long battle. James loves the apples, reminders of an easier life back in Connecticut; while Sadie prefers the applejack they make, an alcoholic refuge from brutal frontier life.

1853: Their youngest child Robert is wandering through Gold Rush California. Restless and haunted by the broken family he left behind, he has made his way alone across the country. In the redwood and giant sequoia groves he finds some solace, collecting seeds for a naturalist who sells plants from the new world to the gardeners of England. But you can run only so far, even in America, and when Robert's past makes an unexpected appearance he must decide whether to strike out again or stake his own claim to a home at last.

Harvest of Secrets by Ellen Crosby

It’s harvest season at Montgomery Estate Vineyard - the busiest time of year for winemakers in Atoka, Virginia. A skull is unearthed near Lucie Montgomery’s family cemetery, and the discovery of the bones coincides with the arrival of handsome, wealthy aristocrat Jean-Claude de Marignac. He’s come to be the head winemaker at neighboring La Vigne Cellars, but he’s no stranger to Lucie - he was her first crush twenty years ago when she spent a summer in France.

Not long after his arrival, Jean-Claude is found dead, and while there is no shortage of suspects who are angry or jealous of his ego and overbearing ways, suspicion falls on Miguel Otero, an immigrant worker at La Vigne, who recently quarreled with Jean-Claude. When Miguel disappears, Lucie receives an ultimatum from her own employees: prove Miguel’s innocence or none of the immigrant community will work for her during the harvest. As Lucie hunts for Jean-Claude’s killer and continues to search for the identity of the skeleton abandoned in the cemetery, she is blindsided by a decades-old secret that shatters everything she thought she knew about her family. Now facing a wrenching emotional choice, Lucie must decide whether it’s finally time to tell the truth and hurt those she loves the most, or keep silent and let past secrets remain dead and buried.

This is the ninth volume of the "Wine Country Mysteries" series.

The Cider Shop Rules by Julie Anne Lindsey

The Fall Festival is in full swing. Civil War reenactors from three counties are partaking in Blossom Valley’s tribute to John Brown. Blue Ridge Mountain foliage is in full bloom. And best of all is Jacob Potter’s pumpkin farm where his hay rides, piglet races, pumpkin picking and corn maze are time-honored draws for locals and tourists alike. That’s why it’s such a shock when Mr. Potter is found dead, hidden under a tarp in the back of Winnie’s pickup truck. This certainly betrays Potter’s reputation as one of the town’s most popular citizens. Fortunately, when it comes to solving a murder, no one has a patch on Winnie. Now, all eyes are on her to do it. Unfortunately, that includes those of the killer who’ll do anything to keep an orchard full of secrets buried.

This is the third volume of the "A Cider Shop Mystery" series.

#fall reading#fiction#reading recommendations#reading recs#book recommendations#book recs#library books#tbr#tbr pile#to read#booklr#book tumblr#book blog#library blog#readers advisory

0 notes