#Jurassic nautilus fossil

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

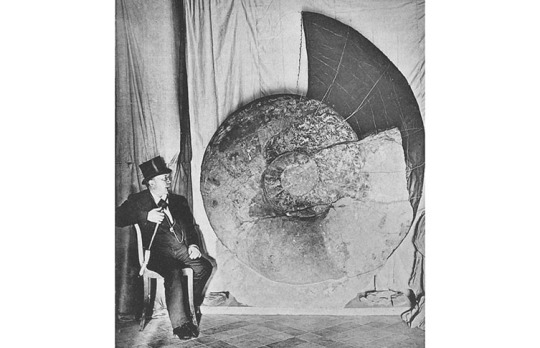

Photo

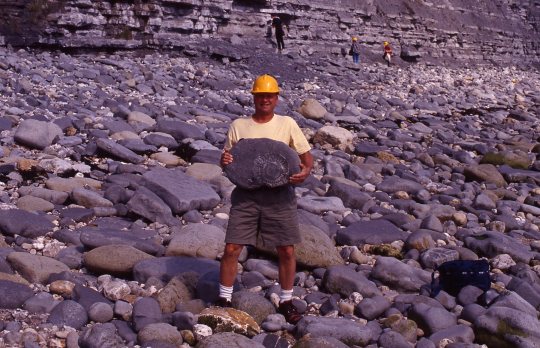

8" Rare Cymatoceras Nautilus Fossil – Toarcian, Jurassic – Dordogne, France – Authentic Fossil with Certificate – Alice Purnell Collection

Presenting a RARE 8" Fossil Nautilus (Cymatoceras) from the Toarcian Stage of the Early Jurassic Period, approximately 182 to 174 million years ago. This exceptional specimen was discovered in Dordogne, France, a region known for its Jurassic marine deposits, and comes from the celebrated Alice Purnell Collection.

Cymatoceras is an extinct genus of nautiloid cephalopods, known for their thick, rounded, and ornamented shells. These marine animals are related to modern-day nautiluses and were free-swimming predators of the ancient oceans. Cymatoceras is distinguished from other nautiloids by its more globular shape and strong ribbing, which adds to its visual appeal as a fossil display specimen.

The Toarcian Stage, part of the Early Jurassic, was characterised by widespread shallow seas teeming with marine life. The sedimentary limestone of Dordogne provided excellent fossil preservation, allowing rare finds like this Cymatoceras to be unearthed with their detail intact.

This 8-inch fossil is a stunning example, showing excellent definition of the shell structure and form. It serves as both a beautiful display piece and an important palaeontological specimen for collectors, educators, and enthusiasts of natural history.

Item Details:

Specimen: Cymatoceras Nautilus

Age: Toarcian, Early Jurassic (~182–174 million years ago)

Location: Dordogne, France

Collection: Alice Purnell Collection

Fossil Type: Nautiloid Cephalopod

Size: Approx. 8 inches (see scale cube = 1cm in photo)

Authenticity: Certificate of Authenticity included

ACTUAL AS SEEN: You will receive the exact specimen pictured. It has been carefully hand-selected and photographed for accurate representation. Due to the natural variation in fossil shape, slight discrepancies in measurements may occur. Colour may also vary depending on lighting conditions and screen display.

Once this item is sold, a replacement specimen will be listed with updated photos and sizing. We recommend saving a screenshot of the listing for your records.

Add a rare and beautifully preserved Jurassic Cymatoceras fossil to your collection today – a genuine relic from Earth’s ancient oceans.

#cymatoceras nautilus fossil#Jurassic nautilus fossil#rare French fossil nautilus#Dordogne fossil specimen#Toarcian marine fossil#authentic nautilus fossil France#fossil cephalopod Jurassic#8 inch nautilus fossil#Alice Purnell fossil collection#nautilus fossil with certificate

0 notes

Text

Наутилус (лат. Nautilus) — род головоногих моллюсков, которых относят к «живым ископаемым». Самый распространенный вид — Nautilus pompilius. Наутилусы относятся к единственному современному роду подкласса наутилоидей. Первые представители наутилоидей появи��ись в кембрии, а его развитие пришлось на палеозой. Наутилиды почти вымерли на границе триаса и юры, но все же дожили до наших дней, в отличие от своих родственников аммонитов. Некоторые виды древних наутилусов достигали размера в 3,5 м. Представители самого крупного вида современных наутилусов достигают максимального размера в 25 см.

Спиральный «домик» моллюска состоит из 38 камер и «построен» по сложному математическому принципу (закон логарифмической прогрессии). Все камеры, кроме последней и самой большой, где размещается тело наутилуса с девятью десятками «ног», соединяются через отверстия между собой сифоном. Раковина наутилуса двухслойная: верхний (наружный) слой – фарфоровидный – действительно напоминает хрупкий фарфор, а внутренний, с перламутровым блеском – перламутровый. «Домик» наутилуса растет вместе с хозяином, который перемещается по мере роста раковины в камеру попросторней. Пустое жилище моллюска после его гибели можно встретить далеко от его места обитания – после гибели «хозяина» их раковины остаются на плаву и перемещаются по воле волн, ветров и течений.

Интересно, что двигается наутилус «в слепую», задом наперед, не видя и не представляя препятствий, которые могут оказаться на его пути.И еще одно удивительное качество этих древних обитателей Земли – у них потрясающая регенерация: буквально через несколько часов раны на их телах затягиваются, а в случае потери щупальца быстро отрастает новое.

Nautilus is a genus of cephalopods, which are classified as "living fossils". The most common species is Nautilus pompilius. Nautilus belong to the only modern genus of the Nautiloid subclass. The first representatives of the Nautiloids appeared in the Cambrian, and its development took place during the Paleozoic. The Nautilids almost died out on the border of the Triassic and Jurassic, but still survived to the present day, unlike their Ammonite relatives. Some species of ancient Nautilus reached a size of 3.5 m. Representatives of the largest species of modern nautilus reach a maximum size of 25 cm.

The spiral "house" of the mollusk consists of 38 chambers and is "built" according to a complex mathematical principle (the law of logarithmic progression). All chambers, except the last and largest, where the nautilus body with nine dozen "legs" is located, are connected through holes with a siphon. The nautilus shell is two–layered: the upper (outer) layer – porcelain–like - really resembles fragile porcelain, and the inner, with a mother-of-pearl luster - mother-of-pearl. The nautilus's "house" grows with its owner, who moves as the shell grows into a larger chamber. The empty dwelling of a mollusk after its death can be found far from its habitat – after the death of the "owner", their shells remain afloat and move at the will of waves, winds and currents.

Interestingly, the Nautilus moves "blindly", backwards, without seeing or imagining the obstacles that may be in its path.And another amazing quality of these ancient inhabitants of the Earth is that they have amazing regeneration: in just a few hours, the wounds on their bodies heal, and in case of loss of tentacles, a new one grows quickly.

Источник:://t.me/+t0G9OYaBjn9kNTBi, /sevaquarium.ru/nautilus/, /habr.com/ru/articles/369547/, //wallpapers.com/nautilus, poknok.art/6613-nautilus-molljusk.html, //wildfauna.ru/nautilus-pompilius, /www.artfile.ru/i.php?i=536090.

#fauna#video#animal video#marine life#marine biology#nature#aquatic animals#cephalopods#Nautilus#nautilus pompilius#living fossils#ocean#benthic#coral#plankton#beautiful#animal photography#nature aesthetic#видео#фауна#природнаякрасота#природа#океан#бентосные#головоногие моллюски#Наутилус#живое ископаемое#коралл#планктон

187 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fossil Friday: Ammonite

Ammonite is a preserved shell belonging to an Ammolite or other creature belonging to the subclass Ammonoidea. These fossils are the remains of an extinct marine cephalopod (mollusc) from the Jurassic period (about 200 million years ago) to the late Cretaceous period (about 66 million years ago). Ammonites died off at roughly the same time as flightless dinosaurs. Ammonites were a unique group of creatures, likely having eight separate arms, resembling a coleoid (squids, octopuses, and cuttlefish), while the shell and it's shape closer resembling a nautilus. An estimated 10-20 thousand species of ammonite have been discovered, so no two fossils will be the same. The largest ammonite specimen found was over 1.8 metres (approx. 5.9 feet) in length, while being an incomplete fossil. Ammonite can be found at any location where prehistoric oceans once were. Ammonite is often used as an index fossil, being used to date the approximate age of the rocks it is embedded in. Ammonite is considered to be one of the world's rarest gemstones when the shell appears iridescent.

It is crucial to be aware of laws and regulations governing fossil collection in your area. Many places require all fossils found to be sent to a palaeontologist, and have strict regulations on the selling of locally found specimens.

More information about ammonites can be found here.

Stay tuned for next week's Fossil Friday!

#crystals#geology#minerals#rocks#fossils#rock collection#gemstone#geoscience#rock hounding#rock of the day#paleo#palaeontology#paleontology#fossil friday by let's talk rocks#fossil friday#let's talk rocks#ammonite

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

What is an ammonite?

Ammonites were shelled cephalopods that died out about 66 million years ago. Fossils of them are found all around the world, sometimes in very large concentrations.

The often tightly wound shells of ammonites may be a familiar sight, but how much do you know about the animals that once lived inside?

What were ammonites?

Before we understood what they were, one of the explanations for ammonites was that they were coiled-up snakes that had been turned to stone, earning them the nickname 'snakestones'. But ammonites weren't reptiles: they were ocean-dwelling molluscs, specifically cephalopods.

An ammonite fossil with a carved snake's head

Zoë Hughes, Curator of Fossil Invertebrates at the Museum, explains, 'Ammonites are extinct shelled cephalopods. All of them had a chambered shell that they used for buoyancy.'

The group Cephalopoda is divided into three subgroups: coleoids (including squids, octopuses and cuttlefishes), nautiloids (the nautiluses) and ammonites.

Ammonites' shells make the animals look most like nautiluses, but they are actually thought to be more closely related to coleoids.

'Some of their morphology was closer to that of the coleoid group,' says Zoë. 'We think it’s more likely that ammonites would have had eight arms rather than lots of tentacles like a nautilus, though the shell is more similar to that of a nautilus.'

Ammonites were born with tiny shells and, as they grew, they built new chambers onto it. They would move their entire body into a new chamber and seal off their old and now too-small living quarters with walls known as septa.

Ammonites looked a bit like nautiluses but are thought to be more closely related to coleoids, a group that includes octopuses and cuttlefish © Esteban De Armas/Shutterstock

Zoë adds, 'The ammonite would have lived in one chamber, but we don't know how often they built a new one.

'Previously it has been suggested this could have been a monthly occurrence, but there is no evidence for that. Some studies looking at the chemical composition of the shells - a field called sclerochronology - are starting to gain some insight of how long ammonites might have lived.'

Ammonites' growing shells typically formed into a flat spiral, known as a planispiral, although a variety of shapes did evolve over time. Shells could be a loose spiral or tightly curled with whorls touching. They could be flat or helical. Some species would begin growing their shell in a tight spiral but straighten it out through later growth phases. There were also some more unusual shapes - the species Nipponites mirabilis, which is found in Japan, is exceptionally rare and looks a bit like a knot.

Nipponites mirabilis ammonites grew in an unusual knot shape, rather than in a typical spiral

While ammonite shells are abundant in the fossil record, it was only recently that scientists have found a very rare fossil of the soft parts of an ammonite. However, fossilised evidence of ammonite arms is yet to be found.

Until now, a lot of what we know about ammonites has been inferred based on what we see in living cephalopods.

How old are ammonites?

The subclass Ammonoidea, a group that is often referred to as ammonites, first appeared about 450 million years ago.

Ammonoidea includes a more exclusive group called Ammonitida, also known as the true ammonites. These animals are known from the Jurassic Period, from about 200 million years ago.

Most ammonites died out at the same time as the non-avian dinosaurs, at the end of the Cretaceous Period, 66 million years ago.

Zoë says, 'We didn't quite lose all of them at the end of the Cretaceous. A few species continued into the Palaeogene in the Western Interior Seaway before dying out.'

The astroid that hit Earth 66 million years ago and ended the age of dinosaurs is also thought to have been responsible for the demise of most ammonites. Image by Donald E Davis courtesy of NASA/JPL-Caltech, via Wikimedia Commons

Read more

Why did ammonites go extinct?

At the end of the Cretaceous Period, an asteroid colliding with Earth brought on a global mass extinction. A lingering impact winter halted photosynthesis on land and in the oceans, which had a major impact on food availability and was devastating for ammonites.

Nautiloids, however, which had ancient relatives that lived at the same time as ammonites, survived this mass extinction. It is thought this is in part linked to these groups' preferred water depths.

Zoë explains, 'Nautilus survived probably because it lives deeper in the ocean. Deeper environments were less affected by what was going on in shallow water environments. This is a pattern that can be seen in other groups, aside from cephalopods – fish, for example.

Ammonites mostly died out 66 million years ago, but other cephalopods, such as nautiluses, survived © Manuae via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 3.0)

The size of hatchlings may also have played in the nautiluses' favour as they were larger and would have been less restricted by the size of food available to them.

How many ammonite species were there?

Scientists can tell species of ammonites apart through several attributes including shell shape, size, age, location, features such as the number and spacing of ribs, defensive spines or shell-strengthening ornamentation.

We know this specimen of Kosmoceras phaeinum is a male from the long prongs, known as lappets, sticking out near the opening of the shell. They might have been used by the male to hold onto the female during mating, a bit like shark claspers.

Read more

But figuring out exactly how many species have been found so far is a bit tricky.

Like modern cephalopods, ammonites displayed sexual dimorphism, which is the noticeable difference in appearance between sexes. But when ammonite fossils that looked unique were found in the past, they tended to be recorded as new species instead of as the microconch (male) or macroconch (female) of an existing species, as this difference between the sexes was not yet known about.

However, it is estimated that over 10,000 species of ammonite - possibly even over 20,000- have been discovered.

Zoë says, 'Ammonites were quite diverse and evolved rapidly, so if you sample stratigraphically through rocks, you can actually see the evolution and the changes through them.'

How big were ammonites?

Ammonites came in a range of sizes, from just a few millimetres to times bigger, with larger sizes more common from the Late Jurassic onwards.

The largest known species of ammonite is Parapuzosia seppenradensis from the Late Cretaceous. The largest specimen found is 1.8 metres in diameter but is also incomplete. If it were complete, this ammonite's total diameter could have been from 2.5-3.5 metres.

Parapuzosia seppenradensis is the largest known species of ammonite. Image via Wikimedia Commons

Where did ammonites live?

Ammonites lived all around the world. Like their modern-day cephalopod relations, they were exclusively ocean-dwelling. They tended to live in more shallow seas and may have had a maximum depth of about 400 metres.

What did ammonites eat and what ate them?

Though it would largely have depended on their size, ammonites would likely have eaten similar things to today's cephalopods, such as crustaceans, bivalves and fish. Smaller species would probably have eaten plankton. Some other species may have been scavengers, like living nautiloids can sometimes be.

Ammonites would also have served as food for other marine animals. There is evidence of mosasaurs and ichthyosaurs having eaten them, and some fish would likely also have considered them prey.

Ichthyosaurs were among the marine animals that would have preyed on ammonites

Why are ammonites important to science?

Ammonites can be a useful tool for scientists. Because they are so common and evolved so rapidly, they are excellent to help determine the age of the rocks they were fossilised in.

Much of the Mesozoic aged rock in Europe has been sectioned into 'ammonite zones', where rocks in different areas can be associated with each other based on the ammonite fossils found in them.

Zoë says, 'I've done a few identifications where there are bits of ichthyosaur and an ammonite has also been found, and they need it identifying. If you can identify the ammonite, you can really narrow things down. They're a really good indicator for biostratigraphy.'

Another potential use for ammonite fossils could be for telling us about how animals responded to climate change in the past.

Zoë explains, 'Shelled marine animals can help us look back into the past at what was going on in terms of climate change following extinction events. If we have known periods of warming or cooling, we can then infer that into modern climate science.

'Looking at size change will tell you an awful lot. Quite often after an extinction event a lot of shelled animals shrink because they don't have the resources they need to grow. If there isn't the resource to build their shells, it's a bit of a struggle for them. You see that in a lot of organisms.'

What is an ammonite? | Natural History Museum (nhm.ac.uk)

Ammonoidea

Animal

Ammonoids are extinct spiral shelled cephalopods comprising the subclass Ammonoidea. They are more closely related to living coleoids (i.e., octopuses, squid and cuttlefish) than they are to shelled nautiloids (such as the living Nautilus). The earliest ammonoids appeared during the Devonian, with the last species vanishing during or soon after the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event. They are often called ammonites, which is most frequently used for members of the order Ammonitida, which represented the only living group of ammonoids from the Jurassic onwards

Scientific name: Ammonoidea

Clade: Neocephalopoda

Domain: Eukaryota

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Mollusca

Ammonoidea - Wikipedia

Is an ammonite fossil worth money?

Well, the largest ammonites with special characters can fetch a very high value above $1,000. Most of them are below $100 though and the commonest ammonites are very affordable. Some examples : an ammonite Acanthohoplites Nodosohoplites fossil from Russia will be found around $150.

Ammonite fossil

6K notes

·

View notes

Photo

A nice mug of hot tea after a morning’s fossil hunting on the Jurassic Coast.

Charmouth Beach, England

#fossils#geology#ammonite#nautilus#fossil hunters#fossil hunting#charmouth#jurassic coast#england#hot tea#winter holidays#exploring#adventure#adventure blog#original blog#original content#original photography

104 notes

·

View notes

Photo

When it comes to how #beautiful the fossil is, the Nautilus is on top. 💎

These #fossils are the shells of a cleoniceras #ammonite and a cenoceras #nautilus. 🐚

.

Follow @neojurassica to see more #prehistoric wonders! 🦕

.

🖥 www.neojurassica.com

🦖 Dinosaur Specialists

🦴 Genuine Fossils

⚙️ Display Customisation

🚚 Free UK Delivery

✈️ International Delivery

.

#ammonites #fossils #fossil #extinct #evolution #jurassic #jurassicpark #jurassicworld #neojurassica #jurassiccoast #nature #wildlife #naturephotography #geology #science #paleontology #palaeontology #biology #beauty #whimsical #natural #garden #countryside #gems #minerals #wonder

https://www.instagram.com/p/CNkGDkSp9XG/?igshid=1h8jg9x7ceoe1

#beautiful#fossils#ammonite#nautilus#prehistoric#ammonites#fossil#extinct#evolution#jurassic#jurassicpark#jurassicworld#neojurassica#jurassiccoast#nature#wildlife#naturephotography#geology#science#paleontology#palaeontology#biology#beauty#whimsical#natural#garden#countryside#gems#minerals#wonder

9 notes

·

View notes

Video

tumblr

ryanunitedbmx

Was going to go biking today but with the bad weather I decided to go look for dead things on the Jurassic coast! Cold wind and rain perfect for it 😜 found my first phylloceras which I’m very happy with!

#fossil#nautilus#shell#fossils#fossilfriday#geology#video#instagram#jurassic coast#phylloceras#the earth story

57 notes

·

View notes

Link

Why We Love Dinosaurs Boria Sax, Nautilus

The Surprising History (and Future) of Dinosaurs Chantel Tattoli, Paris Review

How Do We Know What Dinosaurs Looked Like? Sara Chodosh, Popular Science

What It’s Like to Dig for Dinosaur Bones Steve Macone, The Atlantic

How We Elected T. Rex to Be Our Tyrant Lizard King Riley Black, Smithsonian Magazine

How to Weigh a Dinosaur Elizabeth Yuko, Lifehacker

WATCH: How to Build a Dinosaur Kimberly Mas, Vox

How to Outrun a Dinosaur Cody Cassidy, Wired

This Is What Dinosaur Meat Tasted Like Hilary Pollack, Vice

The Day the Dinosaurs Died Douglas Preston, The New Yorker

What If the Asteroid Never Killed the Dinosaurs? Daniel Kolitz, Gizmodo

How Dinosaurs Shrank and Became Birds Emily Singer, Quanta Magazine

On America’s Wild West of Dinosaur Fossil Hunting Lukas Rieppel, Literary Hub

To Date a Dinosaur Laura Poppick, Knowable Magazine

‘The Nation’s T. rex’: How a Montana Family’s Hike Led to an Incredible Discovery Steve Hendrix, The Washington Post

Why Does the U.S. Army Own So Many Fossils? Sabrina Imbler, Atlas Obscura

How Jurassic Park Changed the Way Movies Looked at Dinosaurs Keith Phipps, Vulture

The Real Science of Bringing Back the Dinosaurs Matt Blitz, Popular Mechanics

The Best Places to Visit for Dinosaur Lovers of Any Age Julie Vick, Afar

The Best Books on Dinosaurs Recommended by Paul Barrett, Five Books

#rawr means i love you in dinosaur#dinosaurs#paleontology#I was going to just do the link but what if the article link expires?#long post#I first learned that rawr means I love you in dinosaur from my nephew

14 notes

·

View notes

Note

prompt 62 and tsukki in honour of your username hehe -🍙

OMG I LOVE U SO MUCH I WAS HOPING SOMEBODY WOULD REQUEST THIS AHHHH I LOVE IT

Tsukishima + 62

62. “If history repeats itself, I am so getting a dinosaur.”

One of the best things about having a boyfriend who worked at a museum was that you could sometimes just pop in after hours and tour all of the exhibits by yourself while waiting for him to finish up. At first, you were quite hesitant and didn’t want to impose, but Tsukishima’s co-workers grew fond of ‘Tsukishima’s S/O’ who seemed to bring out the sweet side of their salty co-worker.

However, that also meant that Tsukishima took every opportunity to try and scare you.

“Roar,” you heard someone growl in your ear but you smirked to yourself, completely unsurprised.

“Reflections, Kei,” you said, pointing at the glass case protecting a nautilus fossil.

“Dang it,” you heard him curse before feeling him wrap an arm around your shoulder. “Oh well, at least I was able to scare the shit out of you while you were looking at the Tyrannosaurus Rex skeleton last week.”

“Not funny! You even forced me to watch Night at the Museum after Jurassic Park the night before!” you playfully hit his side as he laughed.

“Fine, I’ll make it up to you because you’re still not over that,” Tsukishima chuckled and took your hand. “Come on, I’ll show you something.”

You let yourself be dragged along, especially hearing the excitement in your boyfriend’s voice. He was recently put in charge of the Dinosaur Fossils exhibit and you had to practically drag him home to stop him from working overtime. And over dinner, you’d watch him excitedly talk about all the stuff he was working on, despite the fact that you kind of failed Geography/Geology class in high school.

The thing Tsukishima was excited to show you turned out to be a wall mural that had different dinosaurs painted on it, meant to showcase a rough idea of how big a dinosaur would be relative to your own size.

“Wow, this is amazing,” you laughed as Tsukishima stood beside the wall, grinning up at a drawing of a Triceratops.

“It took a lot of work, and a great deal of Math, but I think its something that kids especially would enjoy,” Tsukishima said, looking at the mural proudly.

“They’d love that, Kei,” you smiled up at him. He put his arm around your shoulders.

“Man, if history repeats itself, I am so getting a dinosaur,” Tsukishima sighed.

“You dork,” you nudged him with your hip. “Well, you better wait for some scientists to find a mosquito with dino DNA trapped in amber.”

“If something like that is discovered, I’m definitely not letting it fall into the hands of some corporate billionaire,” Tsukishima snorted.

“So, will you be running the all-new Jurassic Park?” you teased.

“You talk as if you don’t know your own boyfriend,” he rolled his eyes at you. “You bet I’m going to run that whole thing.”

“You’re cute, Kei.”

“Whatever.”

taglist (open to anyone who wants in): @oikaw-ugh @montys-chaos @miyumtwins @strawberriimilkshake @pocubo @sugawara-sweetheart

#tsukishima x reader#hq x reader#funny prompts!requests#hello i would love to tour an empty museum with tsukki#thank u for this prompt onigiri-anon i loved writing this#tsukishima kei#dino lover!tsukki#haikyuu!!#haikyuu!! scenarios

87 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bellerophon

By Ripley Cook

Etymology: Bellerophon, for the Greek mythological hero

First Described By: Montfort, 1808

Classification: Biota, Archaea, Proteoarchaeota, Asgardarchaeota, Eukaryota, Neokaryota, Scotokaryota Opimoda, Podiata, Amorphea, Obazoa, Opisthokonta, Holozoa, Filozoa, Choanozoa, Animalia, Eumetazoa, Parahoxozoa, Bilateria, Nephrozoa, Protostomia, Spiralia, Platytrochozoa, Lophotrochozoa, Mollusca, Conchifera, Gastropoda, Bellerophontida, Bellerophontina, Bellerophontoidea, Bellerophontidae, Bellerophontinae

Referred Species: Too many to list here

Status: Extinct

Time and Place: 453 to 251 million years ago, from the Katian of the Late Ordovician to the Induan of the Early Triassic.

In the Triassic, Bellerophon is known from Wyoming, Greenland, Italy, China, and eastern Russia.

Physical Description: What is it? It’s a snail. The only fossil remains we have of it are shells, which are wide, coiled, and may or may not have external ribbing. Unlike many modern snails, the coiling did not lean to one side. It superficially resembles the shell of a nautilus, but lacked the complex inner chambering cephalopod shells have. The interior of the shell was simply one large open space in which the snail’s body would have coiled. There would have been plenty of it outside the shell, though; the head, of course, and a large muscular foot which which it moved. With Bellerophon in particular, a good amount of the mantle and foot was exposed, and covered part of the outside of the shell. This was common among bellerophontidans.

Diet: Bellerophon’s diet is unknown. Modern marine snails can eat pretty much anything, so nothing is really out of the question for Bellerophon.

Behavior: Bellerophon probably lived like most snails today: slowly crawling across the seafloor, eating without a care in the world. As a large portion of the mantle was exposed, it may have had difficulty retreating into its shell when threatened by predators. Thus, it likely burrowed into the sandy seafloor to avoid predators, like some marine snails do today.

Ecosystem: Bellerophon lived in shallow marine habitats. It lived alongside brachiopods, bivalves, other gastropods (including other bellerophontids), and ammonites. Bellerophon-containing rocks do not contain a lot of charismatic vertebrate taxa (in part because a lot of charismatic vertebrate taxa were freshly dead).

Other: There’s quite a bit of discourse over which species actually belong to Bellerophon. A few Triassic species have been moved to Retispira. Dicellonema may or may not belong to Bellerophon. There’s even been an older hypothesis that Bellerophon wasn’t a snail at all, but a more basal mollusk (in the likely polyphyletic “Monoplacophora”). This sort of taxonomic minutiae is 60% of what mollusk paleontologists talk about. For the purposes of this article, we’re adopting a more sensu lato Bellerophon.

Why am I writing about this random snail? Because this genus was incredibly long-lived. It first evolved in the late Ordovician. The ORDOVICIAN! And amazingly enough, this genus survived the Permian-Triassic extinction. It lasted for just over 200 million years. Aaaaand then it died out, along with almost every other bellerophontidan, very shortly afterwards. This is a phenomenon known as dead clade walking - when an event isn’t bad enough by itself to completely wipe out a taxon, but it messes it up badly enough that the taxon is consigned to extinction shortly afterwards. Only a handful of bellerophontidans are found after the Induan, with the very very last possible member of the clade hailing from the Early Jurassic.

In this way, they parallel the fate of the clade’s namesake from Greek mythology: Bellerophon. From humble beginnings, Bellerophon ended up in the service of King Iobates, who wanted him dead (for you see, Bellerophon was accused of lusting after Iobates’ daughter). To get rid of him without killing him (because killing your guest would be rude), he was given the task of slaying the three-headed, fire-breathing Chimera. He captured and tamed the winged horse Pegasus, and armed only with his bravery and a block of lead on a stick, he slayed the Chimera. For this he became a famous hero. But the fame got to his head, and one day he tried to ride Pegasus up to Olympus. Zeus was pissed at this, so he sent a gadfly to sting Pegasus. Pegasus bucked Bellerophon off, and he landed on a thorny bush, which broke many of his bones and punctured both of his eyes. He spent the rest of his days morosely wandering the land until his death.

~ By Henry Thomas

Sources Under the Cut

Harper, J.A., Rollins, H.B. 1985. Infaunal or semi-infaunal bellerophont gastropods: analysis of Euphemites and functionally related taa.

Homer. 8th century BC, probably. Iliad.

Kaim, A., Nutzel, A. 2011. Dead bellerophontids walking - The short Mesozoic history of the Bellerophontoidea (Gastropoda). Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 308(1-2): 190-199.

Linsley, R.M. 1978. Locomotion rates and shell form in the Gastropoda. Malacologia 17: 193-206.

Smith, W. 1849. Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology.

Yochelson, E.L., Yin, H. (1985). Redesription of Bellerophon asiaticus Wirth (Early Triassic: Gastropoda) from China, and a Survey of Triassic Bellerophontacea. Journal of Paleontology 59(5): 1305-1319.

#bellerophon#bellerophontidan#bellerophontid#gastropod#mollusk#triassic#triassic madness#triassic march madness#paleontology#prehistoric life

109 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Cenoceras Fossil Nautilus - Beacon Limestone, Jurassic, Ilminster Somerset UK - Genuine Specimen with Certificate

This listing features a remarkable Cenoceras fossil nautilus, discovered on 18 April 2025 by our skilled fossil hunters Alister and Alison at Ilminster, Somerset, United Kingdom. The fossil has been meticulously cleaned, prepped, and treated by Alison, highlighting its coiled chambered shell and fine natural detail.

Cenoceras is an extinct genus of nautiloids that lived during the Jurassic period, particularly within the Beacon Limestone Formation. These ancient marine cephalopods are relatives of the modern nautilus, characterised by their planispiral shell structure with smooth whorls and internal chamber divisions that aided in buoyancy control.

The specimen you see in the photos is the exact fossil you will receive, photographed with a 1cm scale cube for reference.

Geological & Fossil Context:

Species: Cenoceras sp. (Nautilus)

Type: Fossilised marine cephalopod

Formation: Beacon Limestone

Location: Ilminster, Somerset, United Kingdom

Age: Jurassic (~201–174 million years ago)

Fossil Features:

Preservation: Outstanding, with defined whorls and chamber patterns

Preparation: Expertly cleaned and stabilised by Alison

Condition: Excellent; ideal for collectors, educational use, or scientific study

Product Highlights:

100% Genuine Fossil Nautilus

Discovered and prepared by Alister & Alison

Includes a Certificate of Authenticity

A striking specimen for fossil collectors and palaeontology enthusiasts

The Beacon Limestone of Ilminster is a renowned Jurassic fossil site celebrated for yielding exceptionally preserved marine life. This Cenoceras fossil nautilus is an exquisite representation of ancient ocean biodiversity and a must-have for any serious fossil collection.

Please refer to the listing photographs for sizing and condition. The item shown is the exact specimen you will receive.

Own a genuine piece of Jurassic marine history with this elegant Cenoceras nautilus fossil from Somerset.

#Cenoceras fossil nautilus#Jurassic nautilus fossil#Beacon Limestone fossil#Ilminster Somerset fossil#fossil nautiloid UK#fossil with certificate#genuine Jurassic fossil#fossil discovered by Alister and Alison#nautilus fossil cleaned by Alison#UK fossil specimen#fossil marine cephalopod#spiral fossil shell#ancient nautiloid fossil#fossil collector item

1 note

·

View note

Text

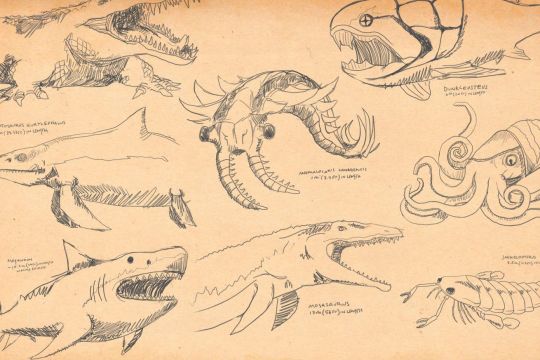

Here are 9 of the most badass animals ever to swim

Art by Tyson Whiting

Say hello to some horrifying sea monsters

This article was originally published on SB Nation a while ago, but was always intended for a Secret Base-y audience. So if you haven’t seen it yet, here you go!

The Earth has some very cool aquatic predators swimming about. Thanks to their intelligence and pack-hunting techniques, orcas are, perhaps, the most dangerous hunters ever to swim the ocean. Saltwater crocodiles are bulletproof murder tanks. And the great white shark, of course, needs no introduction. But now that we’re talking about terrifying underwater murder-beasts, why just settle for just the ones we have around now?

Underwater murder-beasts have a long and distinguished (pre-)history, and I thought it would be fun to introduce y’all to some new pals. TO THE IMAGINARY TIME MACHINE!

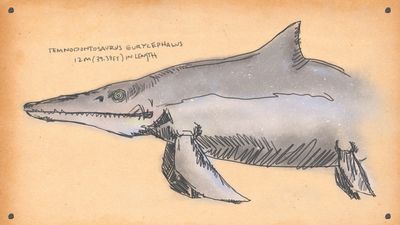

Temnodontosaurus eurycephalus

Grumpy croco-dolphin

Ichthyosaurs evolved 250 million years ago. In the aftermath of the Permian extinction, which killed off a frankly horrifying number of creatures, a group of terrestrial reptiles took to the depleted seas. Fast-forward a little bit and you have primitive ichthyosaurs, creatures so well adapted to oceanic life that they ended up looking like a cross between a crocodile and an extremely ill-tempered, extremely large dolphin.

Fast-forward even further, to the early Jurassic (175 million years ago), and you have Temnodontosaurus eurycephalus. It’s not the largest ichthyosaur ever to grace the seas, but it’s up there, and it’s a far more developed predator than its giant forebears. Somewhere around 30 feet long, T. emnodontosaurus was a powerful swimmer with strong jaws, well-equipped to chow down on other Jurassic swimmers. One closely-related species possessed the largest eyes of any known animal, perfect for hunting in deeper oceanic waters; another has been found with the remains of a different ichthyosaur in is stomach.

This monster considered 13-foot oceanic reptiles a delicious snack. It was also fast. Spare a thought for the poor ocean-going creatures minding their own business before one of these huge assholes rams into them from below at speed, opens those long, toothy jaws and turns them into lunch.

Deinosuchus hatcheri

Dinosaur hunter

Take a saltwater crocodile. Actually, it’s probably best not to. They are, after all, 20-foot, 2,000-pound apex predators more than happy to eat anything they come across, including you. Salties are strong, fast and surprisingly smart. They are at home in the open ocean as well as along the coast. Like all crocodiles, they’re ambush predators who use water as cover to attack their prey. Unlike most crocodiles they’re capable of jumping clear out of the water to get to it. They have the strongest bite of any living animal.

Right. Now that you have a saltwater crocodile in your head, make one, oh, twice as big. Yeah, like that. Decently boat-sized. Terrifying teeth in terrifying, dino-crushing jaws. Armored skin thick enough to turn aside more or less anything.

Your terrifying vision is Deinosuchus hatcheri, a crocodile adapted to more or less the exact same situation as a modern saltwater but in a world inhabited by giant dinosaurs. During the late Cretaceous (80 million years ago), North America was split by a shallow sea, the Western Interior Seaway. D. hatcheri was present on both the western side of the seaway (a slightly smaller species dominated the east), happily chowing through dinosaurs who were foolish enough to get too close.

Anomalocaris canadensis

Nightmare Shrimp

So far we’ve had a dolphin analogue in Temnodontosaurus and an actual crocodile. Cool, but nowhere near the sort of weirdness the past can provide. So let’s go to the deep, deep past, revealed wonderfully by the Burgess Shale. Here we shall find the NIGHTMARE SHRIMP.

One of the problems with studying the very earliest phase of animal life — we’re talking half a billion years at this point — is that it’s squishy, and squishy is not of much benefit when it comes to preserving fossils. Thanks to a fluke of geology, the conditions that produced the Burgess Shale were also capable of preserving soft tissue, giving palaeontologists a rare chance to look into what the seas looked like during the first days of the animal kingdom.

They looked extremely weird. The fauna found in the Burgess Shale was almost obnoxiously uncategorisable. One famous example is the worm Hallucigenia, which so confused everyone involved that it was reconstructed upside-down for the better part of a decade. Another is Opabinia, which looks sort of like a five-eyed miniature vacuum cleaner. I promise I am not making this up.

Anyway, all these critters were apparently food for the ocean’s first proper predator.

With good eyes set on flexible stalks and a surprising turn of speed, Anomalocaris canadensis cruised the Pre-Cambrian seas in death-shrimp mode. It was a full meter long, dwarfing most of its companions in the Burgess Shale. It was also delightfully strange-looking. It is so odd, in fact, that when it was discovered its various body parts were assigned to several different animals.

A. canadensis would be higher on this list if we could be sure of what it actually ate. Long-held to be a trilobite-hunter, recent studies have shown it would probably have had to restrict itself to soft-bodied prey due to relatively flimsy mouthparts, and therefore could only have actually eaten a trilobite just after a moult. But it’s much more fun to imagine this guy roaming the seafloor chomping down on everything, so that’s what we’ll do.

Disclaimer: an old friend of mine is a paleontologist who specializes in the Burgess Shale fossils. I did not contact him for this story, because I am consumed by envy whenever I so much as think about him.

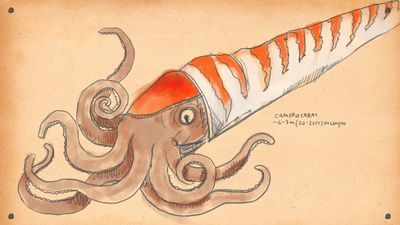

Cameroceras

Spiky death-squid

Back in the Palaeozoic and Mesozoic, cephalopods were armored critters, much like our modern nautilus. The most famous of them, and one of the most widely known extinct animals ever, is the spiral-shelled ammonite. Since they had hard shells, they’re extremely common in marine strata. They also got surprisingly large. The biggest-known ammonite was two meters across. Imagine that thing trying to swim.

Ammonites weren’t the only armored cephalopod prowling the ancient seas, however. The orthocones were straight-shelled versions, and some of those got really, really big. Like Cameroceras. Current estimates put Cameroceras’s shell at upwards of six meters long. That’s three average-sized men stacked on each others’ shoulders.

Somehow this monster was still able to get about in the Ordovician seas. It’s quite hard to imagine it chasing anything around, so it presumably surprised trilobites etc. at nighttime or dug it out of the mud, but since paleoecology is at least in part about imagination, right now I’m enjoying Cameroceras retracting its head deep into its shell and pretending to be a cave before trying to eat whatever entered. It wouldn’t be quite big enough to swallow the Millennium Falcon, buuuuuuuuut ...

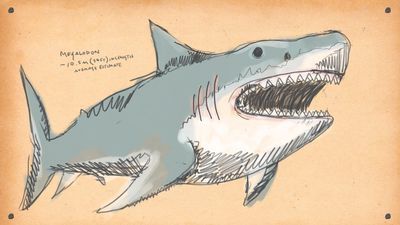

Carcharocles megalodon

The shark that eats planets

Megalodon needs no introduction. The great white shark has a profound hold on popular culture, but its long-gone big sister isn’t far behind. Megalodon made even the most vicious shark in today’s seas look like a toy. Since sharks are mostly soft tissue, they don’t fossilize as well as we’d like, but their teeth do, and Megalodon’s tell a terrifying story.

Megalodon died out only relatively recently. It wasn’t quite contemporaneous with human beings, but its extinction was recent enough that there are plenty of folks willing to tell tall tales of how it might still be swimming somewhere in the depths of the ocean. If it was, probably best not to get anywhere near it — a Megalodon may have had a bite force of up to 10 times the strength of a great white. That’d be a bad day.

What were those huge jaws for? Whales. Apparently, these things liked to swim up from underneath its prey and bite through their chest to reach their internal organs. The ability to kill a whole-ass whale with one bite is honestly horrifying, even if whales in Megalodon’s day were a little smaller than the current batch of great rorquals.

Jaekelopterus rhenaniae

Sea Scorpion

Did you know ‘sea scorpions’ were a thing? Sea scorpions were a thing. Since eurypterids (to give them their proper name) went extinct hundreds of millions of years ago, we don’t have very good comparisons for what these things were like. So let’s get creative. Let’s take a lobster. Despite their ferocious armament, lobsters are relatively placid creatures. They’re not averse to grabbing a fish here or a mollusk there, but they’re not built for hunting. Let’s make the required tweaks.

We need to add eyes. Let’s make them big and sensitive and set for stereoscopic vision, which allows those pincers to be used more effectively to grab prey. Let’s make them better swimmers, too — we’ll add some paddles for agility and short bursts of speed. Let’s make their claws spikier, just for sheer scare value.

Oh and let’s make them 10 feet long and perfectly happy to eat you alive. Now you have a Jaekelopterus. Aren’t you glad they’re dead?

Dunkleosteus terrelli

A, uh, fish-tank

When evolution first came up with bone, it got a little bit carried away. Well, a lot carried away. The era of armored fishes is one of the most fabulously strange in the entire history of the planet. (A personal favorite of mine is Lunapsis, which looks like a fish had a baby with Batman’s utility belt.) With bone-plated heads and upper bodies, these fish probably didn’t swim very well, but who cares? They looked cool as hell, and with that body armor they were well protected against predators.

Which, as it turns out, is the sort of inspiration nature needs to come up with some better predators*. Enter Dunkleosteus, a monster armored fish with a set of jaws which could rip straight through the armor of any other fish slowly swimming through the Devonian ocean. Known to be 20 feet long, it didn’t really have teeth so much as a huge bony beak, which honestly makes the whole contraption even more frightening, like some sort of mobile oceanic guillotine.

*I’m being overly teleological here. Forgive me. Nature, of course, does not ‘come up with’ anything.

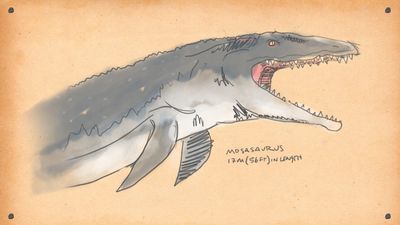

Mosasaurus hoffmanni

For whatever reason, the fauna of Cretaceous period got big. Really, really big. On land, we had Tyrannosaurus Rex. In the skies, azhdarchids the size of small aircraft coasted from thermal to thermal. And in the shallow seas, we had another monster: Mosasaurus.

Mosasaurus was essentially an enormous — estimates have it as almost 60 feet long — ocean-going lizard. Its legs were replaced with bladed paddles for maneuverability and it had a powerful tail for direct propulsion. Mosasaurus ate everything it could get in its mouth, which was a) double-hinged for extra capacity and b) already pretty capacious to begin with.

It would have hung around near the surface of the ocean, where there was an abundance of prey. Mosasaurus could have waited for other marine reptiles (such as Archelon, the largest turtle known) to come up to breathe, grab low-flying pterosaurs on fishing expeditions, or simply have picked off the many large fish that swam the Cretaceous seas.

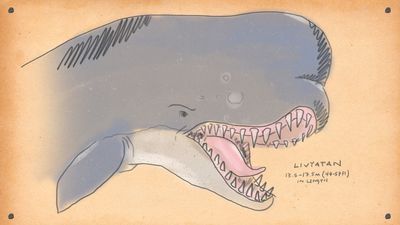

Livyatan Melvilli

Moby-Dick’s even-scarier dad

In 1820, the Essex was lost in the southern Pacific Ocean. The ship had been sent out to hunt for sperm whales (Physeter macrocephalus, since you asked), but soon had the tables turned when it was attacked and sunk by a ferocious bull. Of the 20 crew, only eight survived, and the incident went on to inspire a famous book about whales which you may have heard of.

What you probably haven’t heard of is Livyatan. Modern sperm whales are enormous creatures, but very rare boat attacks aside, they’re only really dangerous to their favorite prey, deep-swimming squid. But not so long ago, geographically speaking, there were also a group of ‘macroraptorial’ sperm whales. These didn’t eat squid. Instead, they competed with Megalodon to hunt other great whales.

Livyatan’s teeth are some of the most awe-inspiring fossils in the world. The biggest ones are 12 inches long and look like artillery shells. Estimates have Livyatan as sitting a touch smaller than its modern friends, but those teeth indicate that it would have been significantly more vicious, fully capable of cutting a sperm whale into very bloody chunks.

It’s not clear whether or not Livyatan hunted alone or in packs, like a modern killer whale, but it had the power and size to be able to plausibly compete with Megalodon even solo. The crew of the Essex found out that a bull sperm whale could be a formidable opponent; one suspects Livyatan would have left even fewer survivors.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cephalopod Fossils from Lyme Regis, England

My position as a Research Volunteer in the Section of Invertebrate Paleontology (IP) allows me to delve into stories about the collection that I find interesting. One of my research assignments is to investigate the fossils from Lyme Regis, England. The Lyme Regis fossils are part of the 130,000 specimens purchased by Andrew Carnegie from the Baron de Bayet of Belgium in 1903. Some of the Bayet fossils are incorporated into the museum’s Dinosaurs in Their Time (DITT) in the Triassic, Jurassic, Cretaceous, and a special Lyme Regis case that showcases 13 invertebrate and vertebrate fossils.

The village of Lyme Regis is situated on the Dorset Coast, and as such, receives some of the worst weather associated with the English Channel. The Lyme Regis cliffs and beaches have been a fossil hunting graveyard for two hundred years, first made famous by resident Mary Anning (1799 – 1847). When she was just twelve years old she found a large skeleton of a marine reptile known as an Ichthyosaur (literally “fish lizard”). Ichthyosaurs were predators that fed on Jurassic fishes and ammonites. It’s easy to see how she developed a love of fossils after discovering such a magnificent creature as a child. For years, she amassed collections of plesiosaurs, pterosaurs, fish skeletons, and other marine fossils and sold them for a living to paleontologists worldwide. In DITT, there are two examples of Ichthyosaur specimens, a skull (CM 877) and a three-foot-long skeleton (CM 23822). Unfortunately, Mary Anning was not recognized during her life for her accomplishments, probably because she was not a trained paleontologist and she was female. After her death, the collections became widely known to the scientific community, bringing about a better understanding of the paleontology of the Dorset coast.

A fascinating piece of trivia about Lyme Regis is the filming of the 1980 movie, The French Lieutenant’s Women, which depicts the lead male actor, Jeremy Irons, using a simple rock hammer to extract a fossil ammonite from the cliff. If only it was that easy to collect from the 300-meter sheer cliff. My supervisor, Albert Kollar, collected fossils along the Lyme Regis beach in 1999. He opined “most fossils are eroded naturally because of the storm waves coming in from the English Channel that eat away at the rock each year, collapsing to the beach in broken blocks that eventually expose the fossils over time.”

My project was to research the Lyme Regis mollusks i.e., ammonites, nautiloids, and belemnites, update their identification, and review the climate aspects of the Jurassic sea that once covered this part of Europe approximately 199 to 190 million years ago. Paleontologists use marine fossils to interpret past paleoclimates and the paleoenvironments in which the animals once lived. The Jurassic is commonly considered as an interval of sustained warmth without any well-documented glacial deposits at the polar regions. The Lyme Regis fossils are preserved in very discrete layers of limestone strata often named “Lias” by European geologists. The terminology used today is early Jurassic Sinemurian Stage. The fossil mollusks are singular specimen’s that measure approximately 1 inch to 8 inches in diameter. The Carnegie of Natural History collection contains 16 invertebrate specimens from the genera Acanthoteuthis, Asteroceras, Eoderoceras, Liparoceras, Lytoceras, Microderoceras, Nautilus, Radstockiceras, and Xipheroceras.

All Bayet fossils were recorded in the Carnegie Museum Catalog of Fossils. The Cephalopod Catalog contains ammonite, nautiloid, and belemnoid fossils assigned by Bayet and includes details such as collection localities and stratigraphic horizon. Some Lyme Regis specimens are recognized by having two letters “BK” and a painted number, as seen on CM 40666. In 1975, a Swiss paleontologist, Dr. Felix Wiedenmayer, was on a research sabbatical to study fossil sponges at the Carnegie Museum, as well as an expert on Mesozoic ammonites from Europe. He reviewed many Mesozoic ammonites providing updated identification to genus and species, and stratigraphic horizon data, including some of the Lyme Regis ammonite fossils.

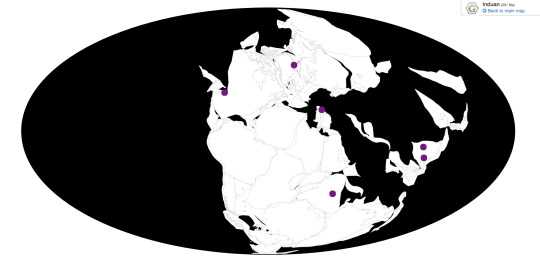

To complete the project, I created a virtual geology, paleontology, and exhibit folder in PowerPoint. This includes photographs of the specimens, a geologic map of Lyme Regis and the Dorset Coast, a Paleogeographic map, the distribution of genus and species in the collection, and references. The photographs in this study were taken by IP Research Associate/volunteer John Harper.

I have had a great experience at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History gaining knowledge about these fossil collections, stratigraphy, and geologic time. Now, I look forward to graduate school in part to study microfossils that lived in the seas during a climate “event” around 56 million years ago during the Paleogene Epoch. This event is called the “Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum” (PETM), and is so named because it demarcates the boundary between these two epochs of geologic time. It has been a pleasure looking at these exceptional cephalopods at the Carnegie Museum, and I look forward to any more potential collaborations in the future.

William Vincett is a research volunteer in the Section of Invertebrate Paleontology and a graduate student at the University of Delaware. Museum employees and volunteers are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

#Carnegie Museum of Natural History#Invertebrate Paleontology#Lyme Regis#Bayet fossils#Carnegie Museum Catalog of Fossils#Fossil#Fossils

132 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Almost-Living Fossils Month #12 -- The Other Nautiluses

Nautiloids are represented today by just two living genera (Nautilus and Allonautilus), but they have a lengthy evolutionary history going back almost 500 million years.

The peak of their diversity was during the first half of the Paleozoic, with many different shapes of shells from coiled to straight, then they began to decline when their relatives the ammonites and coleoids appeared and began to compete for similar ecological niches. Although a few groups of nautiloids survived through the end-Permian mass extinction, most of them had disappeared by the end of the Triassic, leaving just one major remaining lineage known as the Nautilina (or Nautilaceae).

During the mid-to-late Jurassic (~165 mya) two new groups split away from the ancestors of the modern nautiluses -- the cymatoceratids and the hercoglossids.

Cymatoceratids such as Cymatoceras sakalavum here had shells with a ribbed texture. Living during the Early Cretaceous, about 112-109 million years ago, this particular species is known from Japan and Madagascar and could reach a shell diameter of over 15cm (6″).

Hercoglossids, meanwhile, were much more smooth in appearance, but both groups also had more complex undulating sutures between their internal chambers than modern nautiluses do.

These nautiluses made it through the end-Cretaceous mass extinction and had a brief period of renewed success, filling the ecological roles left vacant by the extinct ammonites. But by the end of the Oligocene (~23 mya) both the cymatoceratids and hercoglossids vanished, possibly unable to deal with cooling oceans and the evolution of new predators.

Some of the hercoglossids’ Cenozoic descendants, the aturiids, managed to last a little longer into the Early Pliocene (~5 mya) before another period of cooling seems to have finished them off. Past that point, all that was left of the once-massive nautiloid lineage were their cousins the nautilids, who gave rise to today’s few living representatives.

(It’s also worth noting that the classification of the cymatoceratids seems to be in flux right now. Some paleontologists currently don’t consider Cymatoceras itself to actually be part of the group, instead being a nautilid much closer related to modern nautiluses. If this is the case then the cymatoceratids may not have actually survived past the Late Cretaceous -- but the Cymatoceras genus alone still counts as an “almost-living” fossil since its various species ranged from the Late Jurassic to the Late Oligocene.)

#almost living fossils month#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#hercoglossidae#cymatoceratidae#nautilina#nautilaceae#nautilus#nautilida#nautiloidea#cephalopod#mollusc#invertebrate#art#it's a peppermint

164 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Jurassic park? This creature ruled the seas for millions of years. Growing to the size of a small car, ammonites are one of the most beautiful extinct sea creatures. A soft shelled invertebrate (think squid in a shell) they leave behind their amazingly decorated shells for us to treasure. Leaf like patterns, druzy crystals, and even the magical rainbow sheen. Ammonites are known for that rainbow sheen, so special, it got its own gemstone name, called Ammolite. Once again mother nature never fails to impress. Do you need an ammonite today? Check out my etsy shop! Www.etsy.com/shop/rock2wrap Click section : ammonites and fossils #rock2wrap #crystal #crystalhealing #druzy #ammonite #ammolite #nautical #nautilus #prehistoric #fossil #fossils #sealife #jurassic #seacreatures #spiral #etsy #etsyshop #etsysellersofinstagram #invertebrate #cephalopod #oceanlife

#ammonite#sealife#crystalhealing#nautilus#fossils#jurassic#ammolite#seacreatures#oceanlife#rock2wrap#spiral#invertebrate#crystal#etsyshop#prehistoric#fossil#nautical#druzy#etsy#cephalopod#etsysellersofinstagram

1 note

·

View note

Text

Cephalopod evolution 101: the Beak

I received this question today, I have to say this puzzled me the whole day. Let’s delve into the subject I never thought I would delve in: cephalopod jaw evolution!

Behold, the beak of a very large species of squid. Some people use it as the perfect example of convergent evolution: both birds as well as cephalopods developed a sturdy beak to crack hard materials (e.g. nuts, shells or crabs). But to be quite honest, the evolution and possible precursor of the cephalopod jaws have puzzled scientists for ages.

Beak of a freshly caught squid. Royal society of Chemistry; Photographer: Mark Conlin

Let’s first address the elephant in the room, the squid jaws are not homologous with the radula we know from snails. Even more interesting, squid, octopi and cuttlefish even have a tongue-like radula behind the two jaws to scrape the flesh of their prey. But if the jaws are not a derived form of the radula, what are they derived from?

Let’s say you’re a cephalopod in the late Jurassic period, the sea is full of predators and you need to protect yourself. You have your hard shell, but the predators can just get in there through the front door. Thank your ancestors, because you have what you call an operculum, a hard plate you can use to close your shell. Dzik describes the evolution of the cephalopod operculum in detail as part of his thesis in 1981. Here he explains, based on fossils and previous findings by other authors, that the operculum in the “Hypothetical ancestor of all shelled mollusks (Coniconchia)” can also be found in the most basal groups of cephalopods (Endoceratida):

Evolutionary relationships between main groups of early Cephalopods, with medial sections and apertural views of all groups. Dzik, 1981

In more derived groups, something interesting happened: the operculum splits in two parts, in structures we call the Aptychi. During evolution, the aptychi migrated deeper inside the body, but could still be pushed to the outside to act as an operculum. While the aptychi are retracted, the pointy ends emerged a little and could be used as some way to destroy sturdy preys, like shelled invertebrates, thus functioning like mandibles or real “jaws”.

Some examples of aptychi (top right: Oppelia from Late Jurassic of Solnhofen, Germany; bottom left: aptychi (recto and versus) from Late Jurassic of Lombardy, Italy), and conceptual scheme of their function if indeed they were used to close the shell aperture, as opposed to being jaws. Wikipedia commons; Antonov

Aptychi are often found inside the shell of ammonoids, together with a single plate, what we call an Anaptychus. The function of the Anaptychus, closing the upper part of the shell-opening, can still be found in extant nautili (Nautilus sp.), where a leathery flap closes the shell. It is believed that modern day cephalopods simply removed the problem of protecting the shell entrance by having new structures take care of that (like in the case of the nautilus), or by just loosing the shell partially (e.g. cuttlefish, squid) or even entirely (octopi).

The diet of extinct cephalopods cannot easily be studied, so we cannot be totally sure on where the closing-hatches were used for. For now, this sounds like the most plausible explanation, but there’s still a lot to be discovered.

-Werner [http://www.paleo.pan.pl/people/Dzik/Publications/Cephalopoda.pdf Dzik, 1981]

#Wow I learned a lot#cephalopoda#Werner answers#werner's biology life#squid#biology#science#sciblr#bioblr#cephalopod

1K notes

·

View notes