#Kōka

Photo

A tanuki in front of the Keimei Waterfall in Kōka, Shiga Prefecture, Japan.

Courtesy of Wikipedia: The tanuki has a long history in Japanese legend and folklore. Bake-danuki (化け狸) are a kind of tanuki yōkai (supernatural beings) found in the classics and in the mythology and legends of various places in Japan.

Although the tanuki is a natural, extant animal, the bake-danuki in literature has always been depicted as a strange, even supernatural animal. The earliest appearance of the bake-danuki in literature is in the chapter about Empress Suiko in the Nihon Shoki written during the Nara period. There are such passages as "in two months of spring, there is tanuki in the country of Mutsu (春二月陸奥有狢), they turn into humans and sing songs (化人以歌)". Bake-danuki subsequently appears in such classics as the Nihon Ryōiki and the Uji Shūi Monogatari. In some regions of Japan, bake-danuki is reputed to have abilities similar to those attributed to kitsune (foxes): they can shapeshift into other things or people and possess human beings.

#Japan#Japanese raccoon dog#Keimei Falls#Kōka#Landscape#Nyctereutes viverrinus#Shiga Prefecture#Tanuki#long exposure#rural#waterfall#たぬき#狸#甲賀市#鶏鳴の滝

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

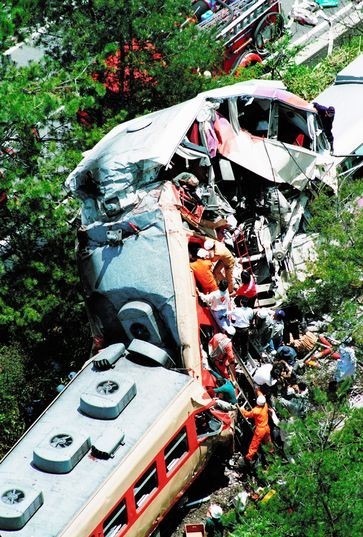

1991- Shigaraki train disaster

#May.14.1991#Shigaraki train disaster#信楽高原鐵道列車衝突事故#killing 42#injuring 614#Kōka City#Shiga#Japanese#history today

0 notes

Photo

Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, Appearing Awake, Behavior of a Girl of the Kōka Era, March 1888

163 notes

·

View notes

Text

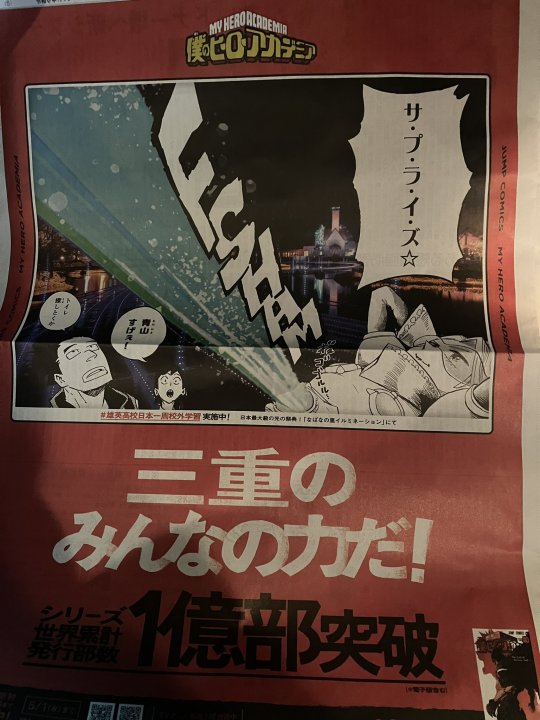

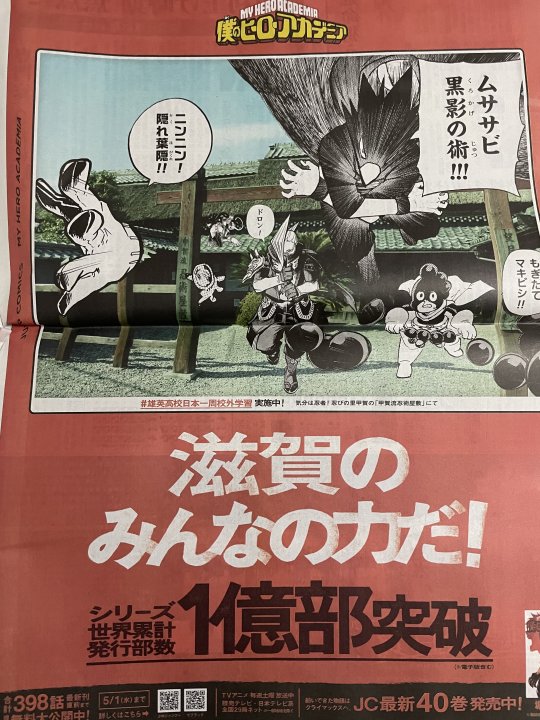

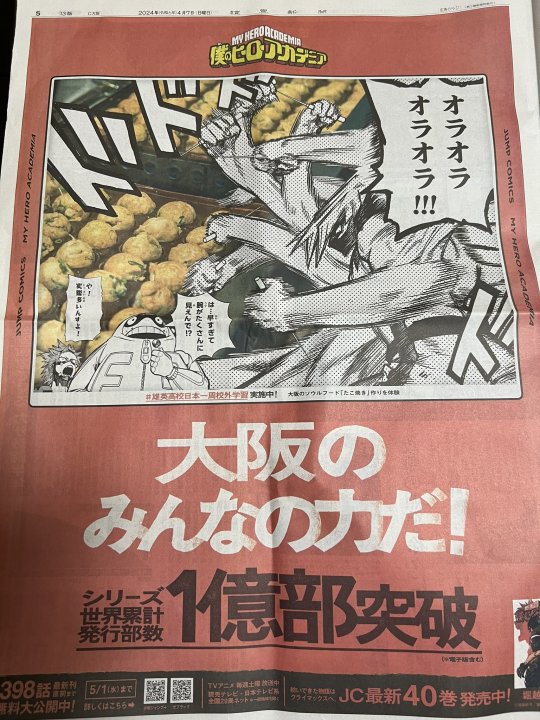

U.A. High School Field Trip Around Japan: Day 4 Translations

This is Day 4 of Shonen Jump’s special commemoration of My Hero Academia reaching one hundred million copies worldwide, which is being rolled out daily across one-week in each prefecture’s newspaper.

The schedule:

April 4th, Day 1: Hokkaidō & Tōhōku regions

April 5th, Day 2: Kantō region

April 6th, Day 3: Chūbu region

April 7th, Day 4: Kansai region

April 8th, Day 5: Chūgoku & Shikoku regions

April 9th, Day 6: Kyūshū & Okinawa regions

April 10th, Day 7: Nationwide release

You can see the illustrations on their website here, where they are released digitally the day after the newspaper release.

Here we go!

Kansai Region

Mie

Photo credit: twitter user Hrkn1500

Aoyama: "Sur-pri-se~!"

Sero: "Amazing, Aoyama!"

Satou: "Should we go look for the toilet?"

Nabana no Sato is a flower park situated within the absolutely massive Nagashima Resort. It has lovely blooms all year, and from October to May it claims to host Japan's biggest illumination event, including a 200-meter long light tunnel.

Shiga

Photo credit: twitter user smile_wk_26

Tokoyami: "Art of the Flying Squirrel Black Shadow!!!"

Mineta: "Imitation Caltrop!!"

Edgeshot: "Abscondance"

Hagakure: "Nin-nin! Hidden Hagakure!!"

They are at the Kōga-ryū Ninjutsu Ninja Village in Kōka city, the birthplace of this school of ninja-arts. I visited the Tōgakure Ninjutsu House in Nagano -- Tōgakure, Iga, and Kōga are considered the three main families of ninjutsu. These kinds of attractions usually have museums dedicated to the style's history and showing off tons of unique historical artifacts, but the main draw is all the activities for visitors to try their hand at being a ninja, shuriken-throwing, wall-climbing, rope-walking, etc.. Hagakure is making a pun, because her surname means "hidden leaves" or "hidden by the leaves" so she is "hidden hidden-leaves." Tokoyami is doing his Black Fallen Angel move, but it's much funnier to make it a giant flying squirrel attack.

Kyōto

Photo credit: twitter user sitatyan_dayo

Ashido: "You can't even see the sky through all the bamboo~!!"

Yaoyorozu: "They say that the growing speed of bamboo is the fastest in the world. I've heard it can grow up to one meter in a single day."

Mineta: "My whole height in a single day... I can't do this!!!

Jirou: "Cheer up."

Label on Mineta: "Mineta Minoru, Height: 1.08 Meters."

Arashiyama Bamboo Forest is a hugely popular tourist spot for its dense, soothing beauty. One meter is equivalent to 3 feet 3 inches; Mineta is just over 3 and a half feet tall.

Ōsaka

Photo credit: twitter user tomikomha

Shouji: "Hyah hyah hyah hyah!!!"

Fat Gum: "He's... he's moving too fast, I can't even see his arms!"

Kirishima: "No, actually, he's got lots of 'em!"

They are making takoyaki, a famous soul food created in Osaka in 1935. It requires a large griddle with rounded molds, and chefs use two metal rods to rotate the batter rapidly. It's really fun to watch them make it, and most stalls put the griddle up against a full-length window to show it off.

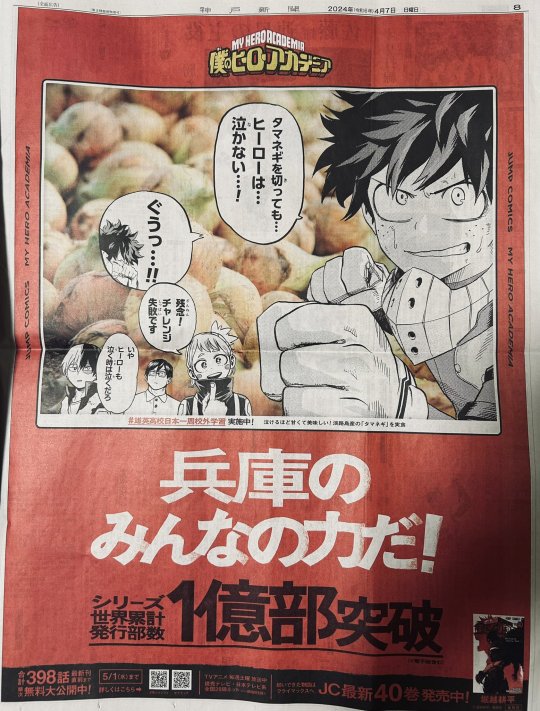

Hyōgo

Photo credit: twitter user NZM_101

Izuku: "Even cutting an onion... a hero... doesn't cry! WWUAAAH"

Ochako: "What a shame! Challenge failed."

Shouto: "No, even heroes cry when they have to."

Awaji Island is famous for its onions and produces some of the sweetest onions in the world. They have a spring crop of sweet but slightly spicy onion, and a fall-time harvest that they store and dry to further develop their sweetness. Shouto's line is from chapter 137 when Izuku insists heroes don't cry while crying into his food. What's funny is that sweet onions supposedly produce less of the chemical that produces tears in humans, so maybe Izuku is just being a lil' crybaby, hehe, but we'll give him the benefit of the doubt and assume he's working with a particularly spicy spring harvest.

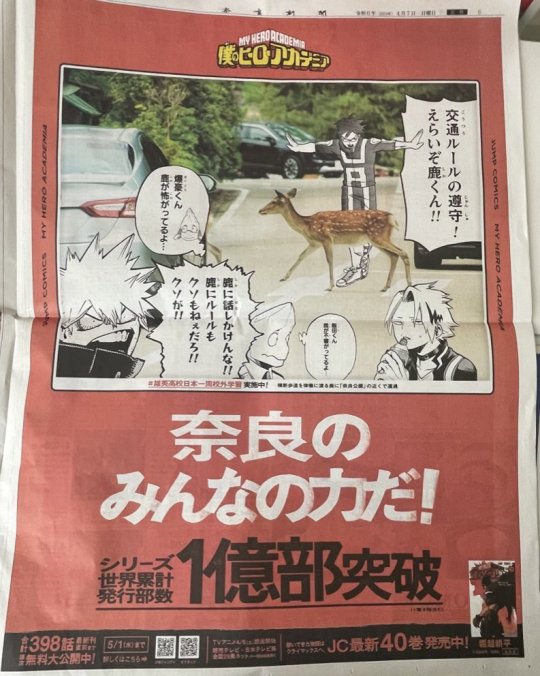

Nara

Photo credit: twitter user yukanicoyomo

Iida: "Observance of traffic laws! OUTSTANDING, DEER-KUN!!"

Kouda (thinking): "Iida-kun, you're making the deer suspicious..."

Bakugou: "Don't talk to the deer!! Deer don't give a shit about rules!! Dammit!!""

Kouda (thinking): "Bakugou-kun, you're scaring the deer..."

They are in Nara Park, where you can buy special crackers to feed the very friendly and booming deer population. Deer in Nara have been protected and seen as important to local Shinto beliefs for at least a thousand years; in 2023, studies from three universities revealed that they actually make up a unique genetic group not found anywhere else. Apparently, the deer in Nara will exchange bows with people, especially if it means they get a snack~

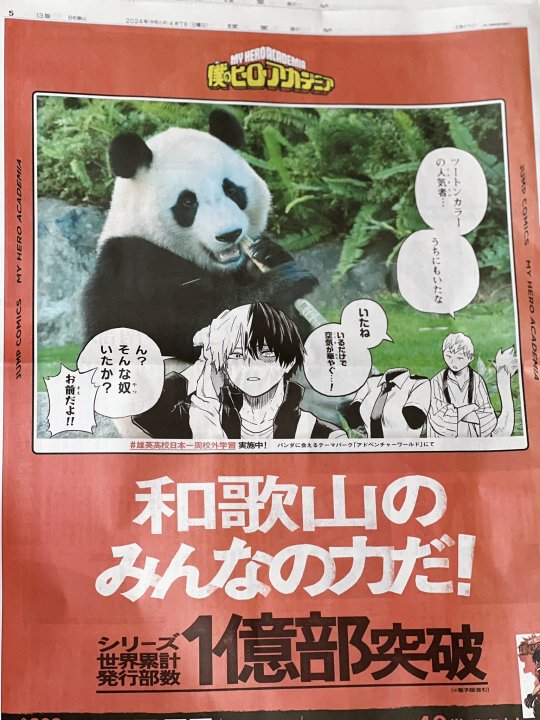

Wakayama

Photo credit: twitter user __sen_115

Ojiro: "A two-tone popular character... We have one of those."

Hagakure: "We do, don't we. Just by being there, he creates a splendid atmosphere...!"

Todoroki: "Huh? There's somebody like that?"

Ojiro: "IT'S YOU!!!"

Visiting Adventure World in Shirahama which is home to a giant panda conservation area. A branch of Chengdu Giant Panda Research Base has bred 17 giant pandas there, which is the most success in breeding outside of mainland China.

That's all for Day 4. Next up is Day 5!

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

Picture of the Seven Islands of Izu: Hachijō-kojima Island

Painted by Hasegawa Shinkichi 1846 (Kōka 3) Kondo Marine Memorial Foundation Collection Library 271

www.library.metro.tokyo.lg.jp

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

Super interesting name here! 仁科 can be read Nishina, Niishina, Nika, Ninka, Ishina, or Jinka, and the meaning can be interpreted as something like Benevolence-ology (though it seems to originate from a place name).

In addition to benevolence, 仁 can also mean humanity, virtue, charity, or man. It's made up of the human radical 亻and the number two 二, and these parts give it its readings: jin, ni, or nin.

科 is a wonderful character because it's only ever read ka! In addition to field of specialization, it can also mean department, course, or section. For example, 工科 kōka is a major in engineering and 医科 ika means medical science. Also, 科学 kagaku means science(s), not to be confused with 化学, also read kagaku, meaning chemistry.

28 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Kōka - Shiga Prefecture

🌹&📷 lulu_camera

#japan#japanese#nippon#travel#sightseeing#koka#shiga#shiga prefecture#traffic#train station#self portrait#portrait photography

43 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Amabie from Japanese legends.

According to legend, an amabie appeared in Higo Province (Kumamoto Prefecture), around the middle of the fourth month, in the year Kōka-3 (mid-May 1846) in the Edo period. A glowing object had been spotted in the sea, almost on a nightly basis. The town's official went to the coast to investigate and witnessed the amabie. According to the sketch made by this official, it had long hair, a mouth like bird's bill, was covered in scales from the neck down and three-legged. Addressing the official, it identified itself as an Amabie with it's ape-like voice and told him that it lived in the open sea. It went on to deliver a prophecy: "Good harvest will continue for six years from the current year; if disease spreads, draw a picture of me and show the picture of me to those who fall ill." Afterward, it returned to the sea. The story was printed in the kawaraban (woodblock-printed bulletins), where its portrait was printed, and this is how the story disseminated in Japan.

Follow @mecthology for more strange tales and lores. DM for pic credit or removal. https://www.instagram.com/p/Ch2eY8oh0ZB/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Amabie

Amabie is a legendary Japanese mermaid or merman with a bird-beak like mouth and three legs or tail-fins, who allegedly emerges from the sea, prophesies either an abundant harvest or an epidemic, and instructed people to make copies of its likeness to defend against illness.

The amabie appears to be a variant or misspelling of the amabiko or amahiko, otherwise known as the amahiko-nyūdo, also a prophetic beast depicted variously in different examples, being mostly as 3-legged or 4-legged, and said to bear ape-like (sometimes torso-less), daruma doll-like, or bird-like, or fish-like resemblance according to commentators.

This information was typically disseminated in the form of illustrated woodblock print bulletins or pamphlets or hand-drawn copies. The amabie was depicted on a print marked with an 1846 date. Attestation to the amabiko predating amabie had not been known until the discovery of a hand-painted leaflet dated 1844.

According to legend, an amabie appeared in Higo Province, around the middle of the fourth month, in the year Kōka-3 in the Edo period. A glowing object had been spotted in the sea, almost on a nightly basis. The town's official went to the coast to investigate and witnessed the amabie. According to the sketch made by this official, it had long hair, a mouth like bird's bill, was covered in scales from the neck down and three-legged. Addressing the official, it identified itself as an amabie and told him that it lived in the open sea. It went on to deliver a prophecy: "Good harvest will continue for six years from the current year; if disease spreads, draw a picture of me and show the picture of me to those who fall ill." Afterward, it returned to the sea. The story was printed in the woodblock-printed bulletins, where its portrait was printed, and this is how the story disseminated in Japan.

The accompanying caption texts describes some as glowing (at night) or having ape-like voices, but description of physical appearance is rather scanty. The newspapers and commentators however provide iconographic analysis of the pictorials (hand-painted and prints).

The majority of pictorial represent the amabiko/amabie as 3-legged (or odd-number legged), with a couple cases rather like an ordinary quadruped.

An amahiko/amabiko (‘sea prince’), whose appearance in Echigo Province is documented on a leaflet dated Tenpō 15.

The hand-copied pamphlet illustration depicts a creature rather like an ape with three legs, the legs seemingly projecting directly from the head (without any neck or torso in-between). The body and face are covered profusely with short hair, except for it being bald-headed. The eyes and ears are human-like, with a pouty or protruding mouth. The creature appeared in the year 1844 and predicted doom to 70% of the Japanese population that year, which could be averted with its picture-amulet.

The Amahiko-no-mikoto (‘His Highness Heaven Prince’) was spotted in a rice paddy in Yuzawa, Niigata, as reported by the Tokyo Nichinichi Shinbun from 1875. The crude newspaper illustration depicts a daruma doll-like or ape-like, hairless-looking four-legged creature. This example stands out since it was emerged not in the ocean but in a wet rice field. Also, the addition of the imperial/divine title of "-mikoto" has been noted by one researcher as resembling the name of one of the Amatsukami or "Heavenly Deities" of ancient Japan.

This creature in the crude drawing is said to resemble a daruma doll or an ape.

There are at least three examples of the amabiko crying like apes.

The texts of all three identify the place of appearance as Shinji-kōri, a non-existent county in Higo Province, and names the discoverer who heard the ape voices heard by night and tracked down the amabiko as one Shibata Hikozaemon (or Goroemon/Gorozaemon).

One ape-voiced amabiko (‘nun prince’) is represented by a hand-painted copy owned by Kōichi Yumoto, an authority in the study of this yōkai. This document has a terminus post quem of 1871 (Meiji 4) or later, The painting is said to depict a quadruped, with extremely close similarity in form to the mikoto (ape- or daruma doll-like) by commentators. However, the amahiko that cried like an ape is reported to have been drawn as a "three-legged monster". And the encyclopedia example described the amabiko as a kechō (‘monstrous bird’) in its sub-heading.

A tangential point of interest is that this text transcribed in the newspaper refers to "we amahiko who dwell in the sea", suggesting there are multiple numbers of the creature.

The foregoing amahiko (‘prince’) was also described as a hikari-mono (glowing object). The glowing is an attribute common to other examples, such as the amabie and amahiko (‘nun prince’) reported in the Nagano Shinbun.

Amabiko (‘heaven prince’) was also purportedly seen glowing at night in the offing of the Western Sea, during the Tenpō era, and illustrations were brought for sale at 5 sen apiece to Kasai kanamachi village, Tokyo, as reported in another newspaper, dated 20 October 1881. This creature allegedly predicted global-scale doom thirty-odd years ahead, conveniently coinciding with the time the peddlers were selling them, prompting researcher Eishun Nagano to comment that while the text may or may not have been genuinely composed in the Edo Period, the illustrations were probably contemporary, though he guesses that the merchandise was surimono woodblock print. The creature also professed to serve the heavenly Tenbu or Deva divinities (of Buddhism), even though he is presumably sea-dwelling.

The amahiko nyūdō (‘nun prince monk’) on a surimono print, which purportedly appeared in Hyūga Province, The illustration here resembles an old man with bird-like body and nine legs.

During the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan, amabie became a popular topic on Twitter in Japan. Manga artists (e.g. Chica Umino, Mari Okazaki and Toshinao Aoki) published their cartoon versions of amabie on social networks. The Twitter account of Orochi Do, an art shop specializing in hanging scrolls of yōkai, is said to have been the first, tweeting "a new coronavirus countermeasure" in late February 2020. A twitter bot account (amabie14) has been collecting images of amabie since March 2020.

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

ASHITAKA’S ZANPAKUTO POWERS.

Ashitaka’s Zanpakutō, Kōka (meaning, red song), is a kidō-type Zanpakutō with the power of decay.

Ashitaka carries two Zanpakutō. Though they are two separate blades, they carry the same name. They can’t be released independently from each other. In their sealed form, they appear similar to each other, the only difference being the colour of the tsuka. One is a faded brown, and the other is a muted grey. (I’ve drawn his Zanpakuto on the wrong side of his body here), but he typically carry them both on his right-hand side. He does this because he is right-handed, and carrying them on this side makes it more difficult for him to draw his weapons. A symbol of his reluctance to fight.

Kōka is released with the call; Kusaru ( meaning; rot, decay ). The brown blade, when released, take on an odd, sable like shape. Its hilt vaguely resembling a dead branch. This is the blade that holds the power of decay. One side of the blade (the “inside”, which is pointed at Ashitaka), is rusty. It is not sharp. However, upon touch, it will decay anything it comes in contact with. This includes other Zanpakuto. Decaying other Zanpakuto is Ashitaka’s most terrifying power. Zanpakuto famously return to their original state after a while, as long as the hilt remains intact. However, Ashitaka’s powers don’t just decay the physical part of a Zanpakuto. It decays the part of the Shinigami’s soul that makes up the Zanpakuto. Effectively erasing a part of his opponent’s soul. And there is no reversing the effect.

The grey blade has a different power when released. It has no hilt. It is completely made out of sharp edges. This is why Ashitaka always wears his gloves. They are specially designed by the Shinigami Research and Development Institute, to allow him to hold onto the sharp blade without cutting his hands.

The two blades can merge together to form a single Zanpakuto. If Ashitaka has to fight, this is how he wields his weapon. Upon merging together, the rusty edge with the power to decay, gets “protected” by the blade-only Zanpakuto. The shape of the Zanpakuto makes it very difficult to wield effectively, and there is really no “correct” way to hold it or use it. Ashitaka’s forearms have a lot of scars from wielding his blade like this, because it is so difficult to hold (it’s not meant to be wielded like this, but he refuses to use the blades separately).

Ashitaka has the power of Bankai. His bankai is named “ Kōka, saigo no oto”, meaning “the final sound of the red song”. In its Bankai state, the merged blades shrink into a ring that attaches itself to Ashitaka’s right index finger. The ring has two “spikes”, which slowly grow, trying to pierce Ashitaka’s fingers as he uses the Bankai. The Bankai emits an aura of autumn, decaying everything and anything within its reach - excluding Ashitaka himself. If the spikes from the ring pierce his skin, he too will be affected by the powers of his Bankai, but his gloves are made to protect him.

The Zanpakuto spirit, Kōka, takes the shape of a child. A little girl dressed in a frilly dress, with long curly hair that falls into her face. She’s always dancing, her hair blowing in the wind. She, just like Ashitaka, can’t help the nature of her powers. Like autumn, she is inevitable. Simply a part of life. Decay and rot come for all things in the end. She is childish and playful, dancing to a quiet song while the world around her rots away.

#[ finally wrote all of this down 8) ]#[ yeah he is kinda overpowered ]#[ but he would never use his powers ]#[ he doesn't even want them ]#longpost //#meta.

4 notes

·

View notes

Video

Revenge was a dish best served cold. But that doesn't mean he wasn't happy. A member of Kōka Jōno's team was sent to rescue her when she made out with her friends.

At the end of Bowser and the Four Tails, Ichigo was sent through time and was taken by a time machine.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#Higashiōmi, #Hikone, #Kōka, #Konan, #Kusatsu, #Maibara, #Moriyama, #Nagahama, #Ōmihachiman, #Ōtsu, #Rittō, #Takashima, #Yasu

0 notes

Text

Wanna Be Queen Bee (ワナビークインビー) - UraShimaSakataSen (浦島坂田船) Color Coded Lyrics

Please note that the color coding is done like this;

Uratanuki Shima Sakata Senra

❤️❤️ Duo (heart colours depending on who is doing said part)

All

Disclaimer: I am not fluent in Japanese, therefore all romaji are done based on what I found in online dictionaries/google translate and edited by me.

youtube

Japanese

(Ei-ei-ei-eight…)

(Ei-ei-ei-eight…)

この物語はフィクション

妄想に添えたキャプション

そうでなければ

毒に耐えられそうにない

「 はじまりだ ! 」

Ya ya ya ya

I made a beeline for you

Ya ya ya ya

I met ya, BUZZ BUZZ

へぇ?お前が女王候補か

どんな言葉で陵辱しよう

幸か不幸か巣は防音房

勝手に喚こうが相乗効果

おいおい勘弁しろ !

コレ俺んじゃねぇな ?

よく見りゃ妥当な状況証拠

かぁー ! こりゃ相当調教甲斐あんなぁ

超高層から絡みながら上昇降下

俺以外のヤツに触らせた

その部位を上書きシて

肉に喰い込む毒の先端が

柔く身も心も溶かして���

💛💜 二人で傷つき傷つけ

💛💜 初めて喜び知って

❤️💚 世界は美しいと羽ばたいた

❤️💚 あの頃には二度と戻れない

「 ねぇ、君が悪いんだよ ?」

OSHIOKI DA BEE (8-8, 8-8, 8-8)

OSHIOKI DA BEE (8-8, 8-8, 8-8)

「 おしおきだ ! 」

Ya ya ya ya

I made a beeline for you

Ya ya ya ya

I met ya, BUZZ BUZZ

Ya ya ya ya

I made a beeline for you

Ya ya ya ya

I met ya, BUG BUG

「 なぁ、次はどうされたい ? 」

(あぁ) 悪者ぶって

(あぁ) 腫れ物ぶって

(あぁ) 太々しい勝負手の沸点

(ガチンガチン) はぁ痛ってぇな

(ガチンガチン) 歯ぁぶつけんな

マジで嫌なら振り払ったら ?

待った無しな淫ら涙

お前以外のヤツが触れた

この部位を上書きシて

口移しで流し込む餌が

完璧に内部を支配する

❤️💚 二人で傷を舐め合って

❤️💚 初めて哀しみ知って

💛💜 世界は残酷だと割り切れば

💛💜 今朽ち果てるのも悪くない

「 おい、よそ見すんな 」

OSHIOKI DA BEE (8-8, 8-8, 8-8)

OSHIOKI DA BEE (8-8, 8-8, 8-8)

「 おしおきだ ! 」

Ya ya ya ya

I made a beeline for you

Ya ya ya ya

I met ya, BUZZ BUZZ

Ya ya ya ya

I made a beeline for you

Ya ya ya ya

I met ya, BUG BUG

この物語はフィクション

妄想に添えたキャプション

そうでなければ

毒に耐えられそうにない

春に目覚め築くセクション

夏に舞い繋ぐリレーション

秋に役目を終えて

冬は越えられそうにない

❤️💛 全て置き去りにして

💚💜 俺の証を宿して

旅立て女王蜂よ

「 お前も、いけ 」

SAYONARA DA BEE (8-8, 8-8, 8-8)

SAYONARA DA BEE (8-8, 8-8, 8-8)

「 さよならだ ! 」

Ya ya ya ya

I made a beeline for you

Ya ya ya ya

I met ya, BUZZ BUZZ

Ya ya ya ya

I made a beeline for you

Ya ya ya ya

I met ya, BUG BUG

めっちゃ HUG HUG

めっちゃ HUM HUM

めっちゃ HUFF HUFF

めっちゃ HACK HACK

I met ya, BUZZ BUZZ, BEE

Romaji

(Ei-ei-ei-eight…)

(Ei-ei-ei-eight…)

Kono monogatari wa fikushon

Mōsō ni soeta kyapushon

Sōdenakereba

Doku ni ta eraresōninai

「 Hajimarida ! 」

Ya ya ya ya

I made a beeline for you

Ya ya ya ya

I met ya, BUZZ BUZZ

Hē? Omae ga joō kōho ka

Donna kotoba de ryōjoku shiyou

Kōkafukōka su wa bōon bō

Katte ni wamekouga sōjō kōka

Oioi kanben shiro !

Kore oren janē na ?

Yoku mirya datōna jōkyō shōko

Kā ! Korya sōtō chōkyō kai an nā

Chō kōsō kara karaminagara jōshō kōka

Ore igai no yatsu ni sawara seta

Sono bui o uwagaki shite

Niku ni kui komu doku no sentan ga

Yawaku mimokokoromo tokashite ku

💛💜 Futari de kizutsuki kizutsuke

💛💜 Hajimete yorokobi shitte

❤️💚 Sekai wa utsukushī to habataita

❤️💚 Anogoro ni wa nidoto modorenai

「 Nē, kimi ga waruinda yo ? 」

OSHIOKI DA BEE (8-8, 8-8, 8-8)

OSHIOKI DA BEE (8-8, 8-8, 8-8)

「 Oshiokida ! 」

Ya ya ya ya

I made a beeline for you

Ya ya ya ya

I met ya, BUZZ BUZZ

Ya ya ya ya

I made a beeline for you

Ya ya ya ya

I met ya, BUG BUG

「 Nā, tusgi wa dō saretai ? 」

(Aa) warumono butte

(Aa) haremono butte

(Aa) futebute shī shōbute no futten

(Gachingachin) hā ittēna

(Gachingachin) hāabutsuken na

Majide iyanara furiharattara ?

Matta-nashina midara namida

Omae igai no yatsu ga fureta

Kono bui o uwagaki shite

Kuchiutsushi de nagashikomu esa ga

Kanpeki ni naibu o shihai suru

❤️💚 Futari de kizu o name atte

❤️💚 Hajimete kanashimi shitte

💛💜 Sekai wa zankokuda to warikireba

💛💜 Ima kuchihateru no mo warukunai

「 Oi, yosomi sun na 」

OSHIOKI DA BEE (8-8, 8-8, 8-8)

OSHIOKI DA BEE (8-8, 8-8, 8-8)

「 Oshiokida ! 」

Ya ya ya ya

I made a beeline for you

Ya ya ya ya

I met ya, BUZZ BUZZ

Ya ya ya ya

I made a beeline for you

Ya ya ya ya

I met ya, BUG BUG

Kono monogatari wa fikushon

Mōsō ni soeta kyapushon

Sōdenakereba

Doku ni tae rare sō ninai

Haru ni mezame kizuku sekushon

Natsu ni mai tsunagu rirēshon

Aki ni yakume o oete

Fuyu wa koe rare sō ninai

❤️💛 Subete okizari ni shite

💚💜 Ore no akashi o yado shite

Tabidate joōbachi yo

「 Omae mo, ike 」

SAYONARA DA BEE (8-8, 8-8, 8-8)

SAYONARA DA BEE (8-8, 8-8, 8-8)

「 Sayonarada ! 」

Ya ya ya ya

I made a beeline for you

Ya ya ya ya

I met ya, BUZZ BUZZ

Ya ya ya ya

I made a beeline for you

Ya ya ya ya

I met ya, BUG BUG

Metcha HUG HUG

Metcha HUM HUM

Metcha HUFF HUFF

Metcha HACK HACK

I met ya, BUZZ BUZZ, BEE

#USSS#urashimasakatasen#uratanuki#shima#aho no sakata#senra#utaite#USSS original song#color coded lyrics#ccl#Youtube

0 notes

Text

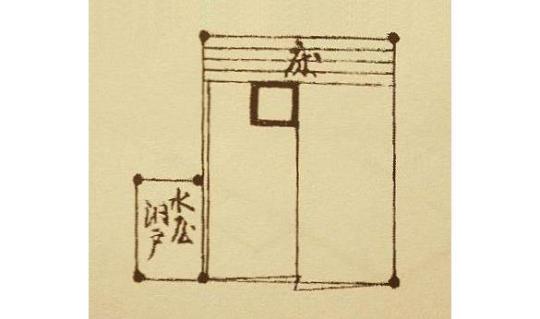

Nampō Roku, Book 7 (36b): the Kaki-ire [書入].

〽 Kaki-ire [書入]:

In [Ri]kyū’s two mat room at Mozuno, the mukō-ro was cut on the side [of the mat] closest to the guests; and the dōko-dana was located] on the left¹.

[The opening of the dōko] was 3-shaku, and in front [of the opening] was a single shōji〚that should be [slid] open all the way [to expose the interior completely during the temae]〛-- with a single-level shelf inside that, however, did not reach all the way across [to the left side of the dōko]². The lower level consisted of a bamboo sunoko³.

A small water-bucket was placed [in the open space to the left of the shelf]⁴. And because there was no koboshi, [the host] must make the effort [to pour the used water into the sunoko] during the temae⁵.

It was a very “sabi” [サビ] and interesting installation⁶.

The [small] unryū-[gama] could be suspended [over the ro] from a [bamboo] jizai⁷.

〚On a certain occasion, for a gathering that was held during the summer, the bamboo-sunoko was refreshed by [replacing the bamboo with] green bamboo; and [Rikyū] also placed a new water-bucket [in the mizuya-dōko]. [In preparation] for the goza, the small fusuma at the front of the [dōko-]dana, and the small shōji at the back [of the mizuya-dōko], were removed.

〚After the guests had taken their seats, [Ri]kyū went around from the katte to the mizuya [and sat down in front of the mizuya-dōko, facing toward the room]. Using water from the chōzu-oke [手水桶], he rinsed the chawan, and [after drying the chawan, he] arranged the chakin and chasen [in it], and lifted it up onto the [dōko’s] shelf. Then he [filled] the mizusashi by pouring the water through a koshi [コシ], and placed it [under the shelf], after which he closed the small shōji [at the back of the mizuya-dōko].

〚From the sadō-guchi [茶堂口], he came out [into the tearoom], and performed the service [of tea]⁸.〛

〚When a mukō-ro is cut on the side of the mat toward the guests, the dōko-dana [should be] located on the left⁹; [and,] as a rule, when the furo is [used] with a dōko-dana, it is best to place [the furo] on the side of the mat closest to the guests -- so it is said¹⁰.〛

_________________________

◎ This brief kaki-ire discusses most of what was known (to the Sen family) about the Mozuno ko-yashiki [百舌鳥野小屋敷]. The sketch of this 2-mat room that I have reproduced several times in this blog is from an Edo period manuscript entitled Cha-den shū [茶傳集]*. In addition to the sketch, this document also repeats more or less the same information that is found in this kaki-ire. In all of these accounts, there is a certain ambiguity or air of indecision that pervades the texts, suggesting that everything is based on hearsay rather than direct experience on the part of anyone involved in the transmission of the story†.

As for the other versions of this entry, Shibayama Fugen’s teihon deviates from the Enkaku-ji text in three instances, which will be discussed in the footnotes.

Meanwhile, Tanaka’s “genpon” version does not appear to have had any major departures from the Enkaku-ji material either (or, since he does not quote the text, any differences must not have altered the meaning in any significant way) -- though it did apparently include two sentences which, even if they are spurious, do reveal an important teaching related to the dōko that is not mentioned elsewhere in the Nampō Roku. For that reason, I decided to include them in the translation (they are discussed in footnotes 8 and 9).

And, finally, I also restored the passage that was apparently moved from this kaki-ire into entry 36. Linguistically it conforms with the idiom of this kaki-ire, and also follows logically from the text, too. All of this non-textual material has been enclosed in doubled brackets, to indicate that it was not part of the kaki-ire as found in the Enkaku-ji manuscript.

___________

*This document is a typical Edo period compendium (dated Kōka 4 [弘化四年], 1847) that includes a hodgepodge of teachings, ranging from the sketches of the chaire shapes from Sōami’s O-kazari ki [御飾記], to quotations from Furuta Sōshitsu’s version of Rikyū’s Nambō-ate no densho [南坊宛の傳書] (apparently only the arrangements that the editor felt were relevant to the practice of chanoyu in his day), as well as his Tsuri-dana no densho [釣棚の傳書], coupled with drawings of various arrangements for the daime and other settings, extracted from such earlier works as the Kai-ki shū [槐記集] and Sō-jin-boku [草人木] (though these, in turn, represent an earlier machi-shū tradition that dates back to Imai Sōkyū and Oribe, rather than being original to either of those two collections), and the Rikyū chanoyu sho [利休茶湯書].

The work does not seem to have been published, but at least several handmade copies were being circulated (and recopied -- occasionally with changes to the contents) within the tea community of the late Edo period, with some suggesting that it was perhaps compiled by someone named Sōmu [宗務], though nothing else seems to be known about him other than that he appears to have been affiliated with one of the Sen family schools (even this is largely deduced from the teachings that he chose to include in this collection, rather than from any biographical information).

†The same is true regarding references to Rikyū’s teachings or practices in works like the Kōshin ge-gaki [江岑夏書], written by Sōtan’s son Kōshin Sōsa [江岑宗左; 1613 ~ 1672]. The material is usually quoted in the vaguest of terms, and the teachings are usually fragmentary and disjointed -- as if heard from other people, rather than preserving any sort of tradition handed down within the family.

¹Kyū no Mozuno no ni-jō-shiki ni, mukō-ro kyaku-tsuke ni kiri, hidari ni dōko-dana ari [休ノモズ野ノ二疊シキニ、向爐客付ニ切、左ニ道古棚アリ].

Mozuno no ni-jō-shiki [百舌鳥野の二疊敷] refers to the room that is also called the Mozuno ko-yashiki [百舌鳥野小屋敷]. This seems to have been the last room created by Rikyū, and it appears to have come as close as physically possible to representing his ideal.

This room had two mats, one for the host, and one for the use of the guests.

Mukō-ro kyaku-tsuki ni kiri [向う爐客付きに切り] means that the ro was cut at the far end of the utensil mat, on the side closest to the guests’ seats.

Hidari ni dōko-dana ari [左に洞庫あり]: the dōko, which was a mizuya-dōko (indeed, it was the first such dōko to have ever been made), was on the left side of the utensil mat, at the foot of the mat (and extending to slightly beyond the middle of the mat, as can be seen in the above sketch).

²San-shaku ni te, mae ichi-mai shōji, uchi no tana ichi-dan iu ni oyobazu [三尺ニテ、前一枚障子、内ノ棚一段云ニ不及].

San-shaku ni te [三尺にて]: the mouth of the mizuya-dōko was three-shaku wide.

This dōko was not a portable wooden box (as had been all of the earlier dōko-dana), but was permanently built into the structure. Thus, the left and right walls were made of mud-plaster, with a proper copper-lined sink, covered with a bamboo sunoko grate functioning as the floor of the dōko.

Mae ichi-mai shōji [前一枚障子] the word “shōji” was sometimes used to describe door panels that were papered on one side only, and sometimes to describe panels that were papered on both sides*. Irrespective of whether the panel was actually papered on the side facing toward the dōko, it seems that the side facing toward the tearoom was papered (and so is sometimes described -- as in entry 36 -- as a “fusuma” [襖], which was the word that came to be used in the Edo period to name such door panels). The panel did not have a wooden or lacquered frame; the entire panel was papered.

Uchi no tana ichi-dan iu ni oyobazu [内の棚一段云うに及ばず]: as with Jōō’s and Rikyū’s earlier dōko, this mizuya-dōko also only had a single shelf, with a single level. However, unlike the ordinary dōko-dana†, this shelf did not extend across the entire width of the tana. Rather, it was the same size as the shelf in an ordinary dōko-dana (around 2-shaku 5-bu long). The right side was attached to the wall of the dōko, while the left side was held up by a vertical bamboo pole suspended from the ceiling of the mizuya-dōko -- in both cases, the same way as a tsuri-dana is suspended within the kamae. The reason for this was because the mizuya-dōko was not only a dōko but also expected to function as a mizuya, so a water-bucket (of the same sort used to carry water to the tsukubai) was also placed therein to provide water for washing the utensils or replenishing the kama. Since this bucket was 8-sun in diameter, it could be accessed freely in the space to the left of the hanging shelf.

Indeed, in Rikyū’s small unryū-gama temae, the kama was lifted into the mizuya-dōko, emptied, rinsed, and then refilled using the water in this bucket, so that the water used for the service of koicha would be as pure, and free of metallic contamination, as absolutely possible‡ -- since the koicha was the focus of the gathering in the small room.

Here, Shibayama's teihon adds a phrase mid-sentence: san-shaku ni te mae ichi-mai shōji, mina aku-yō ni shitari, uchi no tana ichi-dan iu ni oyobazu [三尺ニテ前一枚障子、皆アクヤウニシタリ、内ノ棚一段不及云]. Mina aku-yō ni shitari [皆開くようにしたり] means that (the shōji) should be slid open all the way, to expose the entire interior of the dōko**.

__________

*Such panels, papered on both sides, have been referred to as fusuma [襖] since the Edo period.

This technique is called taiko-bari [太鼓張り] -- that is, the panel is papered on both sides like a drum (which has a drum-head stretched on both sides). Consequently, this kind of panel is sometimes referred to as a taiko-bari shōji [太鼓張障子].

†In the original box-like dōko, the shelf is necessary to keep the tana rigid, and so functions like a brace -- since there is neither a front, nor a fixed back side to the tana. (The back side featured either one, or a pair of, hinged, or possibly sliding, doors -- since that is how utensils were loaded into the dōko from the preparation area, or removed later.)

Dōko of this sort replaced open mizusashi-dana (tana, with four legs, of the same sort that have been placed on the utensil mat since the Edo period -- though originally only tana with two, or sometimes three, legs were used in that way in Rikyū’s chanoyu), and the primary reason seems to have been privacy.

A mizusashi-dana was set up in the katte or passageway next to the fusuma that opened onto the utensil mat, meaning that it was accessed by sliding that panel open. But when this was done, all of the activity in the katte (and, during the shoza, the smells from the cookery that was being assembled for the meal) would also be exposed to the guests. And as chanoyu became more performative, the inclination was to keep things of this sort “off stage,” with the dōko not only making the opening no larger than necessary but, with its wooden back-panel, preventing the guests from seeing anything that was going on in the katte.

‡This also meant that the kama was as cold as possible when it was returned to the ro, giving the guests a little more time to eat the meal than would have been the case if the still-hot kama was used.

**Rikyū’s mizuya-dōko had a single fusuma which slid from the lower end of the utensil mat up toward the head of the mat. When slid open fully, the entire interior of the dōko was exposed (as the phrase added to Shibayama’s teihon notes).

The reason this caveat was necessary was because Sōtan’s mizuya-dōko (which was the more commonly seen version of the mizuya-dōko by the late seventeenth century) had a pair of doors, one sliding toward the foot of the mat, and one sliding toward the head of the mat, so that only half of the dōko could be open at any given time.

In his dōko, which was installed next to a daime utensil mat, the mizusashi (on the sunoko), and the chaire and chawan (both on the shelf) were placed behind the door closest to the head of the mat, and it was this door that the host opened first, in order to take these utensils out and arrange them on the mat. Then that door was closed, and the lower door was opened. Behind that door was the mizu-oke (water bucket), with the hanging shelf projecting only part way across the space -- the hishaku and futaoki were placed on that part of the shelf, and the lower door was open so that the host cold take these things out, and then left open so that the host could pour the used water through the sunoko in that part of the dōko. Consequently, the lower door had to remain open throughout the temae. (This, however, is not generally known; so many people say that a koboshi should be placed on the sunoko in that part of the dōko, with the door closed after the hishaku, futaoki, and koboshi have been taken out. Nevertheless, that kind of usage is not historically accurate.)

³Ge-dan wo take-sunoko shite [下段ヲ竹スノコニシテ].

Ge-dan [下段], which means “lower level,” is referring to the floor of the mizuya-dōko.

Take-sunoko shite [竹簀子にして] means (the lower level) is made of a bamboo sunoko, which allows water to drain away through the grate (making a koboshi unnecessary).

⁴Mizu-oke no chiisaki wo oki [水桶ノチイサキヲ置].

Because the mizuya-dōko is a functioning mizuya, there needs to be a source of clean water (for rinsing utensils, refilling the kama, and so on). Since the empty space (to the left of the shelf) is only 9-sun 5-bu, however, a ceramic mizu-kame [水甕] of the sort usually used for this purpose would be too large. So the best option was to place a small hand-bucket (which measures 8-sun across, and so will fit comfortably in the available space).

Here, Shibayama’s teihon has mizusashi no chiisaki wo oki [水サシノチイサキヲ置キ], which means “a small mizusashi is placed (in the dōko)” -- though this is clearly a mistake* (if only because a small mizusashi would probably not provide the host with enough cold water).

The original rule was that the mizusashi was prepared at dawn, and was supposed to be large enough to hold enough cold water for the entire day's chanoyu†. Contrary to the way things are done nowadays, the host was not supposed to add water to the mizusashi (the mizu-tsugi was used only to periodically replenish the kama when the host added charcoal to the fire so as to keep the kama in a state of readiness throughout the day).

__________

*Though whether it was accidental -- i.e., a copyist's mistake -- or an intellectual failure (misunderstanding the needs of the situation), is unclear.

†Historically, there was a case where a very small mizusashi was used with the ro, though this required the host use a somewhat larger kama (so there would be no danger of running out of water). This usage appeared during Jōō's middle period, probably inspired by a particularly beautiful, albeit very small, vessel that Jōō wanted to find a use for.

In the gokushin-temae (where usually only a single bowl of tea was prepared -- the gokushin-temae was originally performed when offering tea to the image of the Buddha, though later a nobleman took his place), the mizusashi was only opened at the very end of the temae, so the host could add two hishaku of cold water to the kama. Consequently (because the ro-temae was derived from the gokushin-temae), it was possible for the host to moderate the temperature of the kama during the service of tea simply through a judicious use of the yu-gaeshi [湯返し] (dipping up a full hishaku of hot water from the kama, holding it stationary above the mouth of the kama for several seconds so that it cools a little, and then returning the water to the kama: this will suffice to restore the shōfū [松風] sound to the kama, which indicates that the water is the proper temperature for preparing tea).

In this case, either the mizusashi remained closed throughout (and was opened only at the end, after the chawan and chaire had been placed in front of it at the conclusion of the temae), or one was not brought out until the end of the temae (after the host returned the chawan to the katte, he would return to the utensil mat with a mizusashi). In this case the hishaku and futaoki would have to remain on the utensil mat (or on the tana) so the host could make use of them: the mizusashi was opened, and two hishaku of cold water were poured into the kama; after which the kama, and then the mizusashi, were closed. As a result, a very small mizusashi would suffice. This practice was revived during the Edo period, and very tiny mizusashi (most of these seem to have been kashi-bachi that were provided with a lacquered lid so they could be used as mizusashi -- since they were no longer being used for their original purpose once the Sen family began to prefer always serving the omogashi in fuchi-daka).

⁵Koboshi nashi ni temae-hataraki tamaeri [コボシナシニ手前ハタラキ玉ヘリ].

Koboshi nashi ni [コボシ無しに] means “because there is no koboshi...” -- in other words, a koboshi is not used in a room with a mizuya-dōko (at least according to Rikyū’s idea of the way the mizuya-dōko was supposed to be used*).

Temae-hataraki tamaeri [手前働き給えり]: temae-hataraki [手前働き] means when performing† the temae; tamaeri [給えり] means should‡ do.

__________

*Among other things, one of the principals that governs this room is that the host should use no more utensils than necessary. Since used water can be poured through the sunoko, there is no reason for him to buy even a mentsū to use as a koboshi.

†More literally, when working on the temae..., when making the effort (to perform) the temae.

‡Tamaeru [給える] is the potential plain present indicative form of the verb tamau [給う], which means (in the present sentence) to do.

⁶Sabite omoshiroki shitsurai nari [サビテ面白キシツラヰ也].

Sabite [寂びて], which means mellowed with age; quiet yet moving. As a term of aesthetic criticism, sabi does not seem to have been used (at least in the context of chanoyu) before the Edo period, which helps us to date this kaki-ire.

Omoshiroi [面白い] means interesting.

Shitsurai [設い] means a setup, an arrangement, an installation. In other words, the entire room -- but especially the mizuya-dōko* -- comes as close to the essence of chanoyu (at least according to Rikyū’s lights) as it might be humanly possible to achieve.

__________

*As has been mentioned before, this was the first example of the mizuya-dōko ever seen, so it would have had a profound impact on any of Rikyū's contemporaries. Indeed, the description of Rikyū's summer gathering would only enhance this, since it revealed the kinds of things that were possible in this kind of room.

⁷Unryū wo jizai ni kakerare-tari ki [雲龍ヲ自在ニカケラレタリキ].

Unryū wo jizai ni kakerare-tari [雲龍を自在に掛けられたり] means that the small unryū-gama could be suspended on a jizai in this setting.

As mentioned before, the way Rikyū used this kama would have been ideal for this setting. During the winter*, setting the ro up at dawn, Rikyū would have placed an ordinary ro-gama in the ro. Prior to the arrival of the guests, he would have removed the larger kama (the purpose of which was primarily to warm the room), and suspended the small unryū-gama from a bamboo-jizai. The kama would have begun to boil by the time the guests entered. So, in order to give the guests time to eat a small offering of food (served bentō-style in a fuchi-daka), when he lifted the kama out of the ro, he immediately put it in the dōko. After arranging the charcoal, and placing the incense into the ro, Rikyū turned to the kama, emptied it, rinsed it with cold water, and then refilled it using the water from the hand-bucket. Then the still-wet kama was moved into the ro.

The stack of fuchi-daka could have been placed in the dōko ahead of time, so all Rikyū would have had to do was offer them to the guests, then go out and bring bowls of soup in (passing the bowls through the dōko) for them to drink with their simple meal. After they finished, kashi could be served (from a bowl, also passed through the dōko), and they were ready to go out for the naka-dachi just as the little kama began to boil.

Shibayama's version adds a phrase to the beginning of this sentence: kono za ni mo unryu wo jizai ni te kakeraretari [此座ニモ雲龍ヲ自在ニテ掛ラレタリ]. Kono za ni mo [この座にも], which means also in this setting (the unryū-gama can be suspended from a jizai). This implies that the small unryū-gama was not de rigueur in this room -- though this seems to be an Edo period attempt to influence the way the public thought about these small rooms†.

In fact, what little evidence we have suggests that Rikyū used the small unryū-gama regularly in this setting -- and that he did so, with the kama suspended in the ro, all year round‡.

__________

*Though the scant records that survive are far from revealing, it is possible that in the summer, rather than starting the ro at dawn, Rikyū may have reverted to Jōō’s original usage of receiving the guests in a room containing just a shita-bi (composed of three burning gitchō [毬杖]) and the wet kama in the ro.-- so as to keep the ambient temperature as low as possible.

While nothing is actually said about this in any document that I have seen that is directly connected with Rikyū (or which recounts his practices observed first hand), the insistence on beginning the gathering with the ro in this way that was a hallmark of the Sen family’s way of doing things implies that there must have been some sort of precedent based on Rikyū’s having done so (what little they knew of Rikyū and his teachings seems to have come from the last several years of his life, since it was the utensils that Rikyū had used during that final period that Hideyoshi returned to Shōan when he reinstated the Sen family name) -- and his beginning a gathering with the ro in this way on certain occasions (albeit during the hottest part of the year) would have been precedent enough for them to expand the idea into a universal rule (especially because that was the way that the machi-shū affiliated with Imai Sōkyū, among whom Shōan was counted, were already doing things).

The Sen family’s teachings were often based on authentic Rikyū practices (such, for example, the way the furo-temae was performed when using a kiji-tsurube); but it was frequently the case that they took something that was, in fact, exceptional, and turned it into the standard way of doing things. This is how they began to deviate more and more from Rikyū’s chanoyu as the early decades of the Edo period passed (which was usually the result of Sōtan’s difficulty in doing things differently, after the accumulation of a lifetime of muscle-memory from doing things only in one certain way -- because once he became the figure of authority, everything he did was suddenly “the rule;” and that is why, knowing such to be the case, Sōtan tried his best to avoid taking any such position of authority with the bakufu).

†During the Edo period, the idea was spreading that the utensils should be changed frequently, ultimately leading to the argument that everything should be different every time guests (or at least the same guests) were received for chanoyu. Thus, the idea that Rikyū was essentially using the same set of utensils all the time was offensive to the spirit of the times.

‡We must remember that this two-mat room had a 1-shaku 5-sun deep alcove at the far end that extended completely across the entire width of the room. Therefore, the scroll and the flowers arranged would have been centered in that space. Closing the mukō-ro and then placing a furo on top of it (see footnote 10 for the rule regarding the use of the furo in a room that was provided with a dōko) would have been, at the very least, distracting, and possibly could have impeded the guests and host from seeing these things clearly.

With respect to the kakemono, we must remember that, to Rikyū, it was not simply a decoration. The scroll hung in this small room was always a bokuseki featuring hōgo [法語] (a description of, or an admonition to follow, the Buddha’s teachings). As such, the scroll was hung there as much for the host as for his guests -- if not more so. Thus, it was important that the host do nothing to impede their ability to read and appreciate what was written, or distract them from this endeavor.

At this time in his life, Rikyū seems to have begun to adopt Furuta Sōshitsu’s idea of suspending the small unryū-gama so that its mouth was 7-bu below the ro-buchi -- thus the kama essentially disappeared from view, and that is why it was the preferred kama for use in this setting. Since all of the other utensils were placed in the mizuya-dōko, at the beginning of the shoza, and at the beginning of the goza, there was nothing to distract the guests (and host) from what had been arranged -- for their edification -- in the alcove.

⁸The disputed passage from the previous post has been restored to what appears to have been its original place here.

Any questions regarding meaning may be resolved by referring to footnotes 7 to 12 in the previous post.

⁹Mukō-ro kyaku-tsuki ni kiri, hidari ni dōko-dana ari [向爐客付ニ切、左ニ道古棚有リ].

This, and the following, comments are found only in Tanaka’s “genpon” text. So, while they are very likely spurious, they are also extremely important -- and so I will include them here because they are not repeated anywhere else in the Nampō Roku.

Mukō-ro kyaku-tsuki ni kiri [向爐客付に切り] means when the mukō-ro is cut on the side of the utensil mat closest to the guests’ seats....

Hidari ni dōko-dana ari [左に洞庫棚有り] means the doko-dana will be on the left (side of the utensil mat).

The reason for this teaching is that the utensils -- including the mizusashi -- will be lifted out of the dōko and arranged on the mat at the beginning of the temae. If the ro were cut on the left side of the mat in this kind of setting, the utensils would have to be carried across the front of the ro, which would be dangerous. Thus, in rooms that had a dōko (whether it is an ordinary dōko, or a mizuya-dōko -- or, indeed, when the utensils were arranged on a mizusashi-dana that was set up on the far side of the fusuma that was found to the side of the utensil mat), the ro should always be cut as far away from the dōko as possible.

¹⁰Sōjite dōko-dana no furo ha kyaku-tsuki ni oki wo yoshi to iu-iu [総テ道古棚ノ風爐ハ客ツキニ置ヲヨシト云〻].

Sōjite [総じて] means as a rule, in general.

Dōko-dana no furo ha kyaku-tsuki ni oki wo yoshi [洞庫棚の風爐は客付きに置きをよし] means “(in a room that has a) dōko-dana (again irrespective of whether it is an ordinary dōko or a built-in mizuya-dōko), it is best if the furo is placed (on the side of the mat) closest to the guests’ (seats).”

This is an extremely old teaching, that dates back to Jōō. It is, therefore, extremely surprising that many of the modern schools ignore it -- since this rule applies not only in the two-mat room, but even in a 4.5-mat room, or in a shoin.

The furo is always placed on the left side of the daisu because the furo always damages the ji-ita underneath, meaning that its position cannot be changed if the orientation of the room is changed. But in all other situations, when the guests are seated on the host’s right, the furo should be placed on the right -- especially in a room that has a dōko. Because lifting the utensils across the front of the furo in order to place them in the half of the mat to its right is simply too dangerous.

Yes, many modern chajin argue that placing the furo on the right will inconvenience the guest that is seated next to it, and make that person feel hot. But this is hearsay, and I strongly suspect that nobody who makes that claim has ever put it to the text. Immediately beside the furo, the air is, of course, quite hot (though not hot enough to burn the hand unless one foolishly touches the side of the furo). But, as has been explained many times before, the heat and steam cause an upwelling of air, lifting the heat up to the ceiling, and constantly drawing cool air across the floor toward the furo. So while the air next to the furo will certainly feel warm, a guest sitting in the seat adjacent to the ro or furo will feel no difference in ambient temperature at all (I have checked this with a very sensitive digital thermometer, and even 15 cm away there is no change in the temperature -- yet the edge of the utensil mat is at least 16 cm away from the side of the furo when it has been oriented correctly, so the guest will be completely protected from the heat). Furthermore, if there seems to be an excess of heat on that side, this means that the host does not know how to lay the charcoal in the furo. Because the classical rule was that the dō-zumi [胴炭] or wa-dō [輪胴] (which rarely burn even half-way through over the course of a gathering) were always supposed to be put on the side of the fire closest to the guests, and the reason was to prevent heat from rising up intensely on that side of the fire. Before doing anything, the host was expected to consider what he was doing very carefully. When this attitude was replaced by rote, mindless action, the consequences can only be as expected when one does things that should not logically be done.

0 notes

Photo

Today’s word:

硬貨 (pronnounced: Kōka - こうか)

which means: coin.

La palabra de hoy:

硬貨 (se pronuncia: Kōka - こうか)

Significa: moneda.

0 notes

Text

Picture of the Seven Islands of Izu: Hachijōjima Island: Aigae-minato harbor

Painted by Hasegawa Shinkichi 1846 (Kōka 3) Kondo Marine Memorial Foundation Collection Library 271

www.library.metro.tokyo.lg.jp

39 notes

·

View notes