#Kenny Rivero

Photo

Kenny Rivero (American, b. 1981), Vision of Church Flowers, 2020. Oil on canvas, 182.9 × 152.4 cm

166 notes

·

View notes

Text

instagram

Kenny Rivero

Video: detail views of Kenny Rivero, "Flower Ledger (Fallout Shelter)," 2022, Oil, acrylic, graphite, and oil pastel on linen, 72 x 108 inches (182.8 x 274.3 cm). Audio courtesy of Kenny Rivero (@champaint_papi)

1 note

·

View note

Photo

The Dominican-American Kenny Rivero (b 1981) was born and raised in Washington Heights, New York City. He received a BFA from the School of Visual Arts in 2006 and an MFA from the Yale University School of Art in 2012. Rivero has been a guest lecturer at El Museo del Barrio, Williams College, and the School of Visual Arts and a guest critic at The Cooper Union, The Mason Gross School of the Arts at Rutgers University, and New York University. He is the recipient of a Doonesbury Award, The Robert Schoelkopf Memorial Travel Grant, and has been awarded a Visiting Scholar position at New York University.

https://www.interviewmagazine.com/art/kenny-rivero

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

ICA Questions

What piece didn't you like or hated?

I didn't like the pieces done by Denzil Hurley. No disrespect to the artist, but I just didn't like how his pieces looked and they seemed structurally uninteresting to me, despite representing nonverbal graphics.

What piece relates to your current practice?

The Weight of the Oath by Ding Shilun relates the most to my current work. I like to create original characters in my works and place them in interesting settings. It reminds me of my own artwork as well with the unique style as I change my art style often and it shares similar elements to it. There also seems to be a holy or religious element to it that I really like that I also sometimes incorporate into my work.

What piece would you buy, and how much would you pay for it?

I would purchase Mark Handforth's Weeping Moon because I personally enjoy neon lights and symbolism relating to the moon. The colors of the lights are also a nice touch as I really enjoy the combination of pink and blue. I would buy it for around $130-$150 as it is an original work that's programmed to appear like an animation, the price is similar to other similar works so I think it is fair.

What piece would you like to move from its placement in the museum?

I would move Kenny Rivero's No One, No One because it's such a small sketch on what looks to be really small paper. It's a light sketch and the frame around it is also very light against the already white wall. It has barely any contrast against the white wall and it's in the corner of a room which makes it very easy to miss, because I almost did. I would move it to another spot, replace the frame with a darker one, or just replace the piece with another one entirely. Aside from that, the artwork is interesting and made me feel uneasy.

What piece would you incorporate into the collection?

I would incorporate art from Danial Ryan, an artist who paints a lot of plump cats smoking cigarettes or eating junk food. I feel like it would serve as a comical piece to brighten up the mood of the museum and remind guests that art can be silly and lighthearted. It would also most likely receive a lot of media attention because it's funny and people like to take photos of things they think are funny.

0 notes

Text

Coming soon: A Tale Of Three Dojos (Cobra Kai story)

Summary: Daniel, Johnny, and Kreese begin preparing their students for the All-Valley Tournament.

Rating: T

Warning: Swearing and violence

I couldn’t find good gifs of the characters in this story, so I had to use pictures. The pictures are not mine. I found them on Google. All credit goes to the rightful owners.

The Instagram posts in this story were made by @fakesocialmediaa. I would like to thank them.

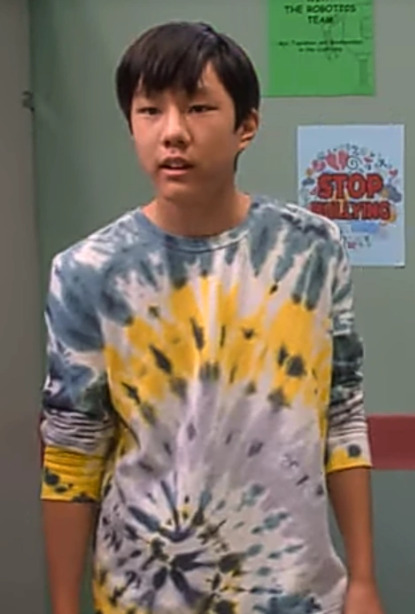

Cast

Gianni DeCenzo as Demetri Alexopoulos

Ralph Macchio as Daniel LaRusso

William Zabka as John “Johnny” Lawrence

Meg Donnelly as Sarah Lawrence

Xolo Maridueña as Miguel Diaz

Jacob Bertrand as Eli “Hawk” Moskowitz

Khalil Everage as Chris

Owen Morgan as Bert

Mary Mouser as Samantha “Sam” LaRusso

Aedin Mincks as Mitch

Nathaniel Oh as Nathaniel

Thomas Ian Griffith as Terrance “Terry” Silver

Martin Kove as John Kreese

Peyton List as Tory Nichols

Joe Seo as Kyler Park

Tanner Buchanan as Robert “Robby” Keene

Courtney Henggeler as Amanda LaRusso

Vanessa Rubio as Carmen Diaz

Rose Bianco as Rosa Diaz

Salome Azizi as Cheyenne Hamidi

Dallas Dupree Young as Kenny Payne

Brock Duncan as Zack Thompson

Griffin Santopietro as Anthony LaRusso

Jaden Labady as Marcus

Milena Rivero as Lia Cabrera

Paul B. Johnson as James Payne

Dan Ahdoot as Anoush Norouzi

Okea Eme-Akwari as Shawn Payne

Nick Marini as young Terrance “Terry” Silver

Barrett Carnahan as young John Kreese

Dustin Lewis as Mr. Palmer

Hannah Kepple as Moon

Dale Whibley as Riley Carter

Annalisa Cochrane as Yasmine

Bret Ernst as Louie LaRusso

Rebecca Lines as Kandace Nichols

Selah Austria as Piper Elswith

Jade Pettyjohn as Carly Bennett

Nichole Brown as Aisha Robinson

Oona O'Brien as Devon Lee

Michael Burgess as Principal Fitzpatrick

Paul Walter Hauser as Raymond “Stingray” Porter

P.J. Byrne as Greg Hughes

Randee Heller as Lucille LaRusso

Julia Macchio as Vanessa LaRusso

Diora Baird as Shannon Keene

Keith Arthur Bolden as Daryl

Kurt Yue as George

Cara AnnMarie as Sue

Matt Lewis as Ron

Carrie Underwood as herself

Yuji Okumoto as Chozen Toguchi

Something you need to know before you read this story:

It is the sequel to Johnny’s Daughter.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Kenny Rivero

Batman is Defeated by the Five Lions (Arm, Leg, Leg, Arm, Head), 2016

45 notes

·

View notes

Photo

'Futuro Modular' at Rachel Uffner hosting EMBAJADA

#Adriana Martinez#Alejandro Lafontant#Antoine Carbonne#ASMA#Básica TV#Chemi Rosado-Seijo#Christopher Rivera#Claudia Peña Salinas#Curtis Talwst Santiago#Dalton Gata#Embajada#Exhibitions#Gabriella Torres-Ferrer#Group Show#Guanina Cotto#Jorge González#José Luis Vargas#Kenny Rivero#Las Nietas de Nonó#Manuel Mendoza Sánchez#Mariana Murcia#Natalia Martínez#New York#Nobutaka Aozaki#Rachel Uffner#Rebecca Adorno#United States

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kenny Rivero, Homage to Homage, 2013, oil/acrylic/latex on canvas

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Downstate Tap (Aquaduct), 2021.

Chucka-chucka-chucka-poom-poom: Kenny Rivero

On learning not to paint when he (we?) should be looking.

A Watcher, 2021.

Sheep Thief: First Gen, 2021.

No Fuemo, 2014.

0 notes

Photo

Kenny Rivero - Batman is Defeated by the Five Lions, 2016

50 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Kenny Rivero (’17), Betye Saar (F ‘85, ‘14), Edra Soto (’00), Nari Ward (’91, F ‘03), and others

Spots, Dots, Pips, Tiles

Pérez Art Museum Miami

1103 Biscayne Blvd., Miami, FL 33132

June 30 – October 29, 2017

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Kenny Rivero, Ft. Wash Fire, 2013.

oil and acrylic on canvas, 30 x 40 inches

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Batman

Falling Bat by Kenny Rivero. 2017.

Nipsey Hustle, government name Ermias Asghedom, was gunned down in front of his store Marathon Clothing in his Crenshaw neighborhood of South Los Angeles by a member of his own gang, the Rollin’ 60’s Crips. Hustle and his business partners had only two months prior purchased the strip mall that included their store, with big plans to revitalize and transform the plaza into an edifying commercial and civic hub for the neighborhood. The murder of a rapper–especially one with gang ties–is unremarkable, but Hustle's death felt particularly tragic. He had made it from the bottom, and instead of reveling in fame and its glittery spoils, he chose to move different. Hustle talked about building communal wealth, business ownership, and financial literacy in his raps and interviews. Him and his partner, the actress Lauren London, could have easily posted up in Beverly Hills or Calabasas with the rest of the beautiful celebrities. Instead they chose to lay down roots and dedicate themselves to South LA and its people. Their good deeds were directly punished.

The history of black leaders and celebrities being violently taken before seeing the fulfillment of their work is as old as America itself. When I think about the murders of revolutionaries like Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X, and Fred Hampton, or artists like Nipsey Hustle, or the Notorious BIG, I am reminded and mildly comforted by the fact that, while they died grossly premature, they all had children: heirs to their formidable legacy and–in the case of the successful artists–often a significant monetary inheritance. These children, possessing the singular combination of revolutionary pedigree, a DuBoisian double-consciousness, personal trauma, and a trust fund are the only plausible persons capable of embodying a hero as complex as the Batman.

On the occasion of the release of the tenth Batman film, The Batman, starring Robert Pattinson, the sixth white man to portray the Dark Knight, I will explore the acutely black aspects of Batman. I will first trouble Batman’s perpetually and pathologically antagonistic relationship to the police and the government at large, in direct contrast to other superheroes that enjoy a problematically close proximity to law enforcement and entrenched systems of power. This leads to an examination of Batman’s doggedly local, yet supra-American purview. A dichotomy exists between Batman and the other titans of the superhero universe. Many of whom either gallivant the globe as unencumbered sovereign citizens or elect to become mascots and dogmatic mouthpieces of American nationalism.

Additionally, I will examine the actual person and body of Batman. As an artist, I want to formally analyze the body and visage of Batman and the ways in which the equally campy, erotic, and ghoulish semiotics of the Batman persona and costume illustrate Bruce Wayne’s conflicted relationship to his own racial and gender identity. In particular I want to examine Bruce Wayne as the black son of rich and famous parents, torn between the poles of his monetary privilege and marginalized racial identity, and made explicit by Wayne’s bizarre employment of his inherited wealth; his “talented tenth” elitism; and the code-switching double-consciousness inherent in any superhero alter-ego.

This is not a case for the recreational recasting Batman as black for a future Batman property, but an attempt to show that blackness is intrinsic to the character and key to the Dark Knight’s enduring relevance.

Public Enemy

Bruce Wayne witnesses the murder of his parents as a young child, which catalyzes him to rid Gotham City of the ills, both particular and systemic, that terrorize the city’s citizens. Through the various Batman properties there is ambivalence as to who actually killed Batman’s parents. In some retellings Batman’s eventual arch-nemesis, the Joker, is the gunman. In others, a nondescript mugger, Joe Chill–emblematic of the pervasive and indiscriminate violence of Gotham. Still, in some instances this Joe Chill is a patsy or hired gun for the mafia, intertwined in every facet of Gotham’s infrastructure and government, bent on ridding Gotham of its do-gooder first family, the Waynes. The inconclusiveness of this central event is reminiscent of the confusion surrounding the killings of Martin Luther King Jr., or Malcolm X, or the still unsolved murders of the Notorious BIG and Tupac Shakur. At the heart of all of these events is a suspicion of the government and an unknowability of their knowledge and/or involvement. Imbued with this inherent distrust and seeing the ineptitude and disinterest of Gotham’s government and police to protect its people, and in many cases outright abetting and colluding with organized crime to plunder its own, Batman opts for self-defense.

A perverted synergy often exists between superheroes and law enforcement. Despite not technically being Americans (or even humans), super-powered figures like Superman and Wonder Woman are spokespersons for the USA, and are routinely called on to bail the nation out of international conflicts requiring extraterrestrial might. These thorny superhero/geopolitical entanglements are keenly satirized in Alan Moore’s Watchmen. The Superman-like Dr. Manhattan is called on by a US government at the end of its rope to help put an end to the Vietnam war. Dr. Manhattan, who can control all matter down to an atomic level, savagely vaporizes all the Viet Cong, bringing the conflict to a swift end and becomes a national hero. Unlike other superheroes that are granted this honorary membership amongst the ranks of police and military, or have military/law enforcement backgrounds themselves (Captain America was literally created by the US government), Batman, despite all the good he performs, is inexplicably, almost pathologically, despised by the police. In the eyes of the state, Batman is a terrorist.

In practice, Batman is a weird amalgam of MLK’s nonviolent pacifism and the fire with fire, self-defense pedagogy of Malcolm X and the Black Panthers. To call Batman a pacifist is laughable, but he does operate within a byzantine moral code of distributing violence. The Batcave contains an arsenal of military grade tanks, air and watercraft (the Bat Boat!), weapons, gadgets, chemicals, and technology formidable enough to defend a medium-sized nation. But Batman does not use guns and is zealously against killing. However, he will stomp a foe within an inch of their life. This odd mix–a dogmatic code of virtue and bloody-knuckled brutality–may appear incongruous, unless you grew up a black man amongst black men. To be a black man in America is to confront injustice and brutality daily, and to know that no one, especially not the state, will protect you. It is also to know that you cannot confront that injustice and brutality in kind. Black people in their heart of hearts know that the constitution, and particularly the second amendment, does not fully apply to us. Stand Your Ground statues are not to be trusted in our case. For black folks, carry permits, like birth certificates, are fictitious to the larger white world. See Philando Castille.

Most summers I lived with my Uncle Frank and Aunt Romaine and my cousins Little Frank and Hugh. My mom insisted that she was sending me to live with my cousins to toughen me up, but really, my single-mom just needed a break after the long school year. I did not mind. I loved those summers spent roaming Baltimore for basketball courts with functional rims; accompanying my cousin Frank on house calls giving people tattoos in their kitchens; nights watching music videos on The Box while drawing X-Men, Spider-man, and characters we’d make up. My Uncle Frank is the calmest, coolest person I know. Only a few times I can recall him getting angry and losing his temper with me and my cousins. Usually, it involved us spoiling our appetites on junk food throughout the day and not being able to finish the dinner he made. One other time I remember vividly was in a dollar store. I reached for a neon orange water gun and asked Uncle Frank to buy it. He snatched the gun out of my hand and said something like, “Never!” His aggression was not towards me, but the gun. The speed with which he placed it back on its display peg with the rest of the toy guns was tinged with fear and danger, as if he was dismantling a bomb. My Uncle Frank had served in the Navy in the time directly after the Vietnam War and hated guns. Between Baltimore and the military, Uncle Frank had witnessed what guns did to those on both sides of the barrel. He also knew that a young black boy with a gun–even a translucent, neon orange, plastic one filled with water–was a target for the wrath of the state. See Tamir Rice.

Neighborhood OG

Thinking about my Uncle Frank some more, it is interesting to look at Batman through the lens of a baby-boomer American black man. Born in the mid 50’s, these men were the children of segregation, but witnessed the civil rights era live: its factions, phases and eventual fade. They attempted to justify their Americaness by serving in the military, but found more in common with the marginalized peoples in the various occupied cities where they were stationed. Since the Civil War black folks have opted into the American military-industrial complex as an attempt to assert and win their humanity in the eyes of White America, their patriotism and loyalty rarely requited. Black soldiers helped deliver victory to the North but were sold out by Northern Appeasement and the advent of Jim Crow. Black soldiers returned to the US after defeating facism in Europe only to be excluded from the heralded GI Bill and ghettoized at home. Dramatized in Spike Lee’s Da 5 Bloods, Vietnamese propaganda radio personality Hannah Hanoi, informed Black soldiers stationed in Vietnam that their hero, Martin Luther King Jr., had been assassinated in Memphis on the morning of April 4, 1968.

Every black family has that father or uncle that served abroad and is a-little-too-into non-western cultures and political thought; from embracing Islam and other eastern religions to espousing Marxism; somewhat on its individual merits, but more to spite the American capitalism that brought their ancestors west to work against their will. Uncle Frank's multicultural eclecticism is pretty mild, and ranges from listening to obscure world music to practicing Ikebana. Culturally, Batman is this Asiatic, Marxist black man. Batman spent his early adult years in Asia learning martial arts, which he now uses to fight crime in the streets of Gotham. The transcendence of restrictive American blackness through an embrace of eastern culture underlies the blaxploitation kung fu movies of the 70s, a motif later adopted by the Wu Tang Clan and satirized in the Martin character, Dragonfly Jones. Black men realize that they will never be fully American, so they should probably find another national identity.

Batman, similarly, is a man without a country. He does not have a vaguely patriotic credo like Superman (Truth, Justice, and the American Way), or nods to the red white and blue in his costume like both Superman and Spider-man. Batman is not a national hero. He is local. Ask any black man where he is from and he will rep his city: Atlanta, Memphis, Houston, Buffalo, Detroit. To actually speak of ourselves as Capital-A-American comes first with a hard swallow. Batman, similarly, has a myopic focus on his hometown of Gotham. Many assume Gotham is a stand-in for New York, but the DC comic universe already has a New York doppelganger: Metropolis, the home of Superman. Gotham on the other hand is the quintessential second-city; segregated, rife with inequality, post-industrial, a declining population, witness to rising crime rates, prey to predatory prospectors.

Embracing this more blue-collar interpretation of Gotham, the Christopher Nolan Batman trilogy dispenses with the Art Deco and technicolor production design of the Tim Burton and Joel Schumacher Batman films respectively, in which Gotham–complete with its own empire state building–was very much a stand in for New York. In The Dark Knight Rises, the football team, the Gotham Rogues, was modeled after the Pittsburgh Steelers, down to the black and yellow team colors, and even had then Steelers’ players Hines Ward and Ben Rothlesberger playing the Rogues. Personally, the Baltimore Ravens would have been a better model for a Gotham football team as they were named after Poe's famous gothic poem The Raven, and broadly I like to think of Gotham as Baltimore. Its gray skies and gargoyle-covered gothic architecture inspired Billie Holiday's blues, and the city is imbued with the revolutionary spirit of Harriet Tubman, Frederick Douglass, and Thurgood Marshall. A potentially overlooked exchange occurs between Bruce Wayne and his butler, Alfred, while first exploring the soon-to-be Batcave under Wayne Manor in 2005’s Batman Begins. Alfred informs Bruce that the passages were created by his great-grandfather and used to shelter runaway slaves during the underground railroad. The quick aside reveals the progressive pedigree of Bruce Wayne. Furthermore, what is the Bat Signal if not a constellation along the underground railroad? A symbol, not unlike the drinking gourd, serving as a light of hope in the face of governmental terrorism.

Rich Nigga

Batman’s wealth is traditionally foregrounded in the default assumption of Batman as a white man. As much as US economic policy has historically worked to sabotage black wealth, there are in fact rich black people. More precisely, the volatile mixture of blackness and affluence combines to create the particular catalyst necessary for the creation of a Batman. The book of Ecclesiastes frankly states “[M]oney is a shelter.” But in America financial success has never protected black people the way it does other groups, and in many cases carries with it a curse. The Notorious BIG wrote, Mo Money Mo Problems. Successful black people still die disproportionately from treatable or preventable diseases (Chadwick Boseman) or have their potentially fatal pain disregarded (Serena Williams). And, not that being a rich celebrity should shield you, but black celebrities routinely have their civil rights violated by police and other agents of the state like all black people. These individual anecdotes can be place alongside the targeted and unabated massacres of thriving black financial enclaves like Black Wall Street in Tulsa Oklahoma or Rosewood, Florida, as well as state supported actions by the FBI to surveil, sabotage, and in some cases murder, black leaders like Martin Luther king Jr., Malcolm X, and the Black Panthers.

Beyond the systemic and structural violence, to be black and rich is also to draw the attention of random evil actors. Quite different from invisible old money wealth, black affluence often comes with the spotlight of being a famous athlete or entertainer, where the specific dollar amounts of one’s fortune are typed in boldface on sports pages or the record sales charts. At a time when he was perhaps the most famous person on the planet, Michael Jordan’s father, James, was murdered by two teenagers at a North Carolina rest stop who carjacked him for his Lexus and dumped his body in a swamp. In tandem with these external threats, the burden of being black and rich exacts an internal toil. Right or wrong, black affluence comes with the burden to “give back”, to “not forget where you came from,” and to make up for the failure of the state to take care of those who look like you. Black billionaires are held to a higher standard and are demonized for participating in the same capitalistic practices that enriched the generations of wealthy whites before them. According to progressive politicians, “every billionaire is a failure of policy.” Conveniently, this chorus came into favor at the exact time when new demographics of persons were just beginning to take advantage of America's admittedly corrupt financial system.

Batman embodies this struggle of violence without and within. Undoubtedly, there is a sado-masochistic heart to the character. A billionaire who spends his nights in the seedy parts of town picking fights. Batman is Bruce Wayne slumming. Batman serves as Gotham's dominatrix; punishing the city for its bad behavior one leather gloved punch at a time. The pain also provides Wayne absolution for the survivor’s remorse he feels for both living through the deadly encounter that took his parents, and the burden of wealth that he carries as a black man. Bruce Wayne pours all of his time and fortune into crafting and maintaining his drag persona of Batman. He puts on eye black so that you can only see the whites of his eyes, adding to his ghoulish visage, but for some reason he does not apply the makeup to the area around his mouth that similarly peaks from under his mask, so avoiding full blackface. The avoidance of full blackface is not a decision of discretion or political correctness. This choice projects Bruce Wayne’s ambivalence.

He is projecting a hyper-masculine-hyper-blackness but by revealing his pale complexion under his masks he reminds those he encounters that he is not actually the full version of blackness that he is weaponizing. The Joel Schumacher directed films Batman Forever and Batman & Robin from 1995 and 1997 respectively did much establish this bombastically hyper-masculine performance that augments into a queer and racial appropriation. Memes before memes, the shots zooming in on the batsuit’s vacuum formed rubber buttocks, protruding codpiece, and chest of Batman, complete with articulated nipples, were played for comic relief. Val Kilmer and George Clooney were less playing superheroes and more male drag kings. However ludicrous, the ever more anatomically accurate suit made manifest the dangerous proximity of Bruce Wayne’s performance of Batman to black minstrelsy.

The selective utilization and negation of blackness is an age old tactic. The larger world devours black cuisine, fashion, and slang while at the same time denigrating its originators. A young Justin TImberlake parrots black music while simultaneously scavenging and scapegoating the black body of Janet Jackson; all in service of establishing his adult artist bona fides. Unfortunately, this form of parasitism is also equally expressed by black men. Kanye West erected his musical career on raps mining the history and images black slavery as evergreen symbols of black people’s continued oppression. “This grave shift is like a slave ship.” Years into his success–as he personally attempted to assert his post-racial autonomy through self-hating proximity to white supremacist demagoguery–he called slavery a “choice.” This is the dangerous prerogative of black identity construction. Amongst all black people there is a judicious deployment of blackness to both survive and capitalize within a racist society. One might need to turn on stereotypes of black hyper-sexuality while hitting on a woman at the bar, and then immediately dispel with the bluster while negotiating an interaction with the cops during a “routine” traffic stop on the way home. In every scenario there is the need to perform the “right” style of blackness.

Every one of these performative choices reifies the subjective status of blackness to the dominant culture. In Adrian Piper’s Mythic Being series the artist roams across New York city styled with an afro and thick push-broom mustache picking fights with white men and catcalling white women. The brilliance and continued relevance of Piper’s project lies in its reflexivity. Piper is parodying America’s reductive stereotyping of black men as dangerous and hyper-sexual. But she, as a mixed black woman, is also revealing, admitting, as the designer and performer of this character, that these depictions have been personally internalized. An interesting exchange occurs between Bruce Wayne and Alfred, as Bruce Wayne is first designing his Batman costume, again in 2005’s Batman Begins. Alfred asks the question we’ve all always wanted to ask, “Why bats?” Bruce Wayne insists that he’s terrified of bats and that he aims to embody that fear and project it onto the criminals of Gotham. “The’ll feel my fear.” Alfred appears persuaded, and the movie–feeling justified in its argument–moves on. But I call bullshit. How many grown men, especially ones that grew up in a large metropolitan area have a legitimate and debilitating fear of Bats? In the end, like Piper, it is Batman’s own blackness that he fears most, but also what he understands terrifies the larger society as well.

Dark Knight, For Real

The recent adaptation of Alan Moore’s Watchmen on HBO opens with a jolting depiction of the 1929 Tulsa Black Wall Street massacre and a young black boy who is protected by his parents from the holocaust as they themselves are slain in the carnage. In a subsequent episode we find out that this character is the legendary Hooded Justice, the first of the Minutemen, the superheroes of the Watchmen world. A victim himself of Jim Crow era terrorism against black people, Hooded Justice narrowly escapes being lynched and proceeds straightway to thwarting a mugging he stumbles upon during his escape. The burlap sack over his head and noose around his neck–once the barbarous apparatus of his demise–are repurposed into the symbol of vengeance and liberation for the black folks in his neighborhood, as well as the looming comeuppance for the perpetrators of white supremacist terror running and ruining the city.

This episode of Watchmen, written by Cort Jefferson who won an Emmy for his work, makes it plain: the foundational superhero emerged from a cauldron of racial oppression with a compulsion to fight on behalf of the marginalized. I would contend that this is the case for most, if not all super and everyday heroes broadly. Jurgen Habermas’ theories on the public sphere make an emphatic case that only those excluded from the center of public life have the vantage point to diagnose the inequities within, in addition to the actual impulse to rectify those injustices. Those who benefit from the status quo rarely possess the urgency to undermine their own comfortable station.

Superheroes, in their most familiar form, are a distinctly American export for better and worse. In many ways their fiction lies less in their superhuman strength, or ability to shapeshift, or bend time, but rather in their implausible goodness. They are moral, kind, selfless, and brave; all things that Americans, feeling ownership over these characters, would hope to project as their own. Which brings us back to the inherent blackness of Batman and the superhero broadly. And why–despite its triviality–it irritates me that these icons and all the good they represent–good most often derived from the resolve and courage necessary to survive exclusion and oppression–are so effortlessly co-opted by the larger white world, that we do not question the ability of a white man to adequately fill the black suit of Batman.

10 notes

·

View notes