#Khoe-Kwadi

Text

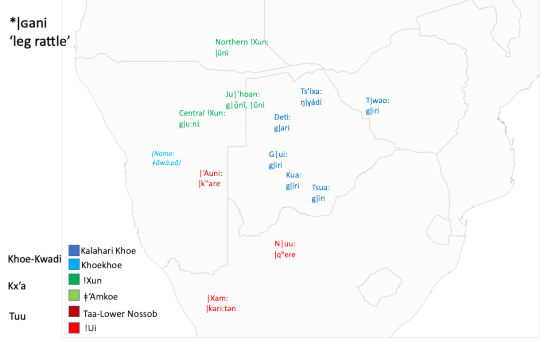

Leg rattles in southern African music

Question (@culmaer): I've been slowly making my way through Percival Kirby's book on South African instruments (published in 1934), and I assume the spellings he uses for words from the various 'Khoisan' languages are ad hoc, phonetic transcriptions and not the standardised spellings in use today. part of me was hoping there was maybe a contemporary survey of instruments, or perhaps just easily accessible dictionaries/word-lists I could go through to check the spellings he uses

Kirby mentions ankle rattles made of springbok ears of the "Qung Bushmen" and cites the name from Bleek and Lloyd's Bushman Folk-lore as |keriten. I assume by Qung he means !Kung, but I'm not sure how similar !Kung and |Xam are, or if Kirby is making an attribution error ? nevertheless, are you able to verify that name and spelling ?

then, I'm particularly curious about a springbok horn flute, per Kirby, "used by the Kalahari Bushmen near Haruchas, SWA, [which] they call |garras or |garris" as well as a similar instrument used by the "Berg-Dama" called ǂnunib, although their version apparently stopped the horn with wood to create a more specialised embouchure, which I would love more details on. are these instruments still played ?

!Xun (<!Kung>) and |Xam belong to different language families: !Xun is a Kx’a language spoken along the northwestern Kalahari Basin fringe (northern Namibia, southern Angola, northwestern Botswana). |Xam was Tuu language of the !Ui subbranch which was spoken in the west of South Africa, all the way down to the Cape. |Xam went extinct during the first half of the 20th century, while !Xun is still a vibrant language with multiple dialects. !Xun and |Xam speakers were probably not in contact with each other in historical times, but received both influence from Khoekhoe herders (who speak an unrelated language of the Khoe-Kwadi family).

Kx’a and Tuu are resident language families exclusively spoken by foragers, while Khoe-Kwadi languages were introduced from the east around 2,000 years ago; at present, they are spoken by foragers (“Kalahari Khoe”) and herders (“Khoekhoe” and the extinct Angolan language “Kwadi”).

The ‘leg rattle’ word you cite here seems pretty widespread:

Interestingly, the root *ǀɢani (my reconstruction) is indeed distributed across all three families. The underlying uvular onset (uvularity is still visible in N|uu) is responsible for the sound changes /a/ > /u/ and /n/ > /r/. It is impossible to say which of the three families is the source and I am inclined to believe that this root may be very old and refer to a very widespread cultural practice (i.e., dancing with leg rattles) (this is not to say it is evidence for a “Khoisan” family; just for a very old contact area).

I wonder whether Kirby’s “|garras or |garris” ‘springbok horn flute’ is actually the same root. The word is certainly from Khoekhoe because it has the feminine singular suffix -s. The location where it was recorded, Haruchas, also seems Nama-territory to me, so I strongly doubt this was recorded among “Kalahari Bushmen”. Haacke & Eiseb (2002) have an entry <ǀgȁríb> ‘quick grass, esp. Cynodon dactylon’, but that does not seem to make a lot of sense here - unless, of course, Kirby got confused and the word he lists actually denotes a grass flute. Damara ǂnunib appears to be the standard Khoekhoe word for ‘flute, play flute’ (Haacke & Eiseb 2002: 415).

Leg rattles are still very common in many San and San-descendant groups from southern Africa. They are also used by some Bantu groups like the Tswana, probably due to influence from neighboring hunter-gatherers.

In the Botswanan San group I worked with for many years, leg rattles are especially used in ritual performances which are not meant for strangers to witness. However, I have videos from a cultural workshop in which a San group from Zimbabwe performs with leg rattles. I'll share the videos as soon as I am back in office next week.

The Khoekhoe flutes are, to the best of my knowledge, no longer used. I will make a post on that (and the terms associated with the flute ensembles) tomorrow.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

TOC: Diachronica Vol. 40, No. 5 (2023)

2023. iii, 114 pp.

Table of Contents

INTRODUCTION

Claire’s corner

Claire Bowern

pp. 569–570

Obituary: Terry Kaufman

Lyle Campbell & Sarah Grey Thomason

pp. 571–577

ARTICLES – AUFSÄTZE

Gender reduction in contact: The case of Romani in nineteenth-century Hungary

Márton A. Baló & Zuzana Bodnárová

pp. 578–608

Lost in translation: A historical-comparative reconstruction of Proto-Khoe-Kwadi based on archival data

Anne-Maria Fehn & Jorge Rocha

pp. 609–665

EDITORIAL

Diachrony and Diachronica http://dlvr.it/T5yHMJ

0 notes

Text

countries most closely correlated with a single language family (roughly ranked)

Japan, Japonic

Georgia, Kartvelian

Central African Republic, Ubangian (controversial classification as Niger-Congo)

Mongolian, Mongolic (point of diversity is in Mongolia, but most of the branches/subbranches are centered in Russia or China)

Australia, Pama-Nyungan (pre-contact; non-Pama-Nyungan was historically only spoken in a small part of the country)

Indonesia, Austronesian (while Taiwan is clearly the point of diversity for Austronesian, and there are several branches not spoken in Indonesia, i.e., Palauan, Chamorro, Polynesian, various Philippine branches... and there are Papuan languages spoken in Indonesia, Indonesia contains most Austronesian speakers and contains many Malayo-Polynesian branches)

India, Dravidian (~20% of the country speaks a Dravidian language, and the only language centered outside India is Brahui)

Thailand, Kra-Dai (~60% of speakers of languages in this family are Thai speakers, and 96% of Thailand speaks it as L1 or L2)

Sudan, Nilo-Saharan (This may be one of the most arbitrary. Assuming settlement of native ethnic groups was similar before Arab settlement, almost everyone in what is now Sudan spoke a language classified as Nilo-Saharan. Of course, Nilo-Saharan is a very controversial language family. Also, there were [controversial?] Niger-Congo speakers in the Kordofan/Nuba Mountains, and Beja on the Red Sea. Several few Nilo-Saharan branches aren't spoken in Sudan at all; Kunama, Nara, Surmic, Songhay and Kuliak. A few are barely spoken in the country, like Nilotic or Maban. There are so many holes to poke in this, but if you assumed the demographics of non-Arabs in the country would be directly extrapolated to 100% pre-contact, I think it would make the top 15 in the world in correlation between language family and political borders)

Korea, Koreanic (if it was a unified country)

Bougainville, Northern Bougainville & Southern Bougainville (It's hard to determine speaker counts for these languages; while the largest language in the hypothetical future country is Austronesian, these two Papuan [non-Austronesian] language families dominate the main island)

Guatemala, Mayan (Mamean, K'iche'an and Q'anjob'alan are centered in the country. Yucatecan, Huastecan and Ch'olan-Tzeltalan are not.)

Nicaragua, Misumalpan

Bolivia, Aymara (there are many language families with members in Bolivia, and isolates in Bolivia, but... about 80% of speakers are in Bolivia, and about 40% of indigenous language speakers in Bolivia speak Aymara)

Paraguay, Tupi-Guarani (While there are many minor Tupi-Guarani languages spoken outside of Paraguay, and several other language families and isolates spoken in Paraguay, the majority of people in Paraguay speak Guarani, there are still monolingual speakers, etc.)

Panama, Chibchan (pre-contact)

Uruguay, Charruan (pre-contact)

Namibia, Khoe-Kwadi (Kwadi was centered in Angola and Kalahari Khoe is centered in Botswana, but the majority of speakers of a Khoe language are Khoekhoe speakers, and 11% of people in Namibia speak Khoekhoe. Certainly not as close a correlation as in many of these countries)

East Timor, Timor-Alor-Pantar

In terms of US states, the following stick out:

Oklahoma, Caddoan (pre-contact; I know nomadic groups can be hard to pin down, apply that disclaimer to some of the items above, too)

New York, Iroquoian (there were also Algonquian languages spoken in New York, and Tuscarora, Nottoway and Cherokee were spoken further south, while Huron-Wyandot was spoken in Canada... please note that Lake Iroquoian was not the point of diversity for the family. This situation is a lot like Mongolia, with other branches being spoken outside of the state, and the sister branch, Huron-Wyandot, being spoken elsewhere, too)

Washington, Salishan (it's bizarre that anywhere on the west coast could be very closely correlated to a single language family, given the west coast is overall the most diverse area in North America, linguistically, by far. There are Chimakuan languages and a Wakashan language, Makah, spoken at the northern end of the Olympic peninsula. There are Chinookan and Sahaptian/Plateau Penutian languages spoken at the southern and eastern edges of the state. Kwalhoquia-Tlatskanai is a subbranch of Northern Athabaskan spoken in the state, too. And of course, Bella Coola and Tillamook are divergent branches of the family spoken outside of Washington, and there are Coast Salish languages in BC; the Interior Salish area also extends into BC, Idaho and Montana. However, probably at least 80% of land in Washington was settled by Salishan peoples at the time of contact)

Florida, Timucua

A lot of this is really hard to quantify, but it's an interesting overlap of figures to consider.

0 notes

Text

Scientists have found a population of people in Africa‘s Namib desert that were believed to have disappeared 50 years ago. Anthropologists initially believed that the community disappeared when the languages spoken in the region died out. However, experts are now realizing that this group kept its genetic identity when their native language disappeared.The Kwepe, one of the groups in southern Africa’s Namib Desert, spoke the Kwadi language.“Kwadi was a click-language that shared a common ancestor with the Khoe languages spoken by foragers and herders across Southern Africa,” said researcher Anne-Maria Fehn, according to SciTechDaily.Through DNA research, experts found the descendants of the people who spoke Kwadi. The team also traced Bantu-speaking and other groups whose language was believed to be lost.The team of researchers included scientists from the University of Bern in Switzerland, as well as the University of Porto in Portugal and the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Germany. According to the researchers, the Kwadi-speaking descendants share a common ancestry, which is only found in groups from the Namib desert.“Previous studies revealed that foragers from the Kalahari desert descend from an ancestral population who was the first to split from all other extant humans. Our results consistently place the newly identified ancestry within the same ancestral lineage but suggest that the Namib-related ancestry diverged from all other southern African ancestries, followed by a split of northern and southern Kalahari ancestries,” said researcher Mark Stoneking.The people who spoke Kwadi started speaking Bantu languages more recently, scientists said.“A lot of our efforts were placed in understanding how much of this local variation and global eccentricity was caused by genetic drift — a random process that disproportionately affects small populations — and by admixtures from vanished populations,” said researcher Dr. Sandra Oliveira from the University of Bern.

0 notes

Text

‘cow/ox/generic bovine’ is pretty similar in a lot of the world’s languages

this post is a joke I don’t believe in proto world

K’XA *gumi

!XÓÕ gùmi

KHOE KWADI

— Khoekhoegowab gomas

— ||Ani góɛ̀

BANTU (some pre-nasalisation..)

— Swahili-Chichewa ng’ombe

— Rwanda-Rundi inka

— Nguni-Sotho n/a (Khoe loan)

ATLANTIC

— Wolof nag

— Fula, Fulani nagge

— Akan, Twi nantwie

MANDÉ & VOLTA (don’t fit the pattern...)

NILOTIC / SUDANIC / SAHARAN / SONGHAY ???

URALIC (mostly doesn’t fit the pattern)

— Inari Sámi kussâ

— Finnish nauta

P. INDO-EUROPEAN *gʷṓws

P. SEMITIC *θawr (cow) doesn’t fit, but see the root for ox below

— Hebrew baqár

— Arabic baqara (compare the /b/ to the labialisation in PIE and Sinitic)

OLD TURKIC ingek

DRAVIDIAN (mostly doesn’t fit the pattern)

— Telugu âvu (if it’s < ‘avu < gawu, then it fits !)

AUSTROASIATIC

— Vietnamese bò (initial labial again)

— Lao ngua

AUSTRONESIAN (doesn’t fit at all :/ )

SINO-TIBETAN

— Burmese nwa:

— Old Chinese *ŋʷə, or *ŋʷɯ

IN THE AMERICAS

— Proto-Yupic *nakacuɣ-na-

— Cherokee waga

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

||Gana

Linguistic Diversity Challenge — Regional Edition

Post # 9 / 12: Southern Africa

What is the language known as to linguists, and by the speakers themselves?

//Gana, G//ana, Dxana, G//anakhwe, Gxana, Gxanna, /Khessakoe, //Ganakhwe, Kanakoe (etc.)

Where is the language spoken?

Central district: Boteti subdistrict, cattleposts south and west of Rakops; Ghanzi district: New Xadi and Ghanzi, Ghanzi commercial farms, Central Kalahari Game Reserv; Botswana

How many speakers does the language have?

between 1000 and 1500; it is endangered

What are some of the languages relatives and is it part of a contact area?

Khoe-Kwadi >> Khoe >> Non-Khoekhoe >> West-Kxoe >> Naro-Ana >> Ana >> //Gana

Its main dialect G|ui is member of the Kalahari Basin Sprachbund

Is the language written? If it is, with what script?

basically none; a practical orthography has been suggested by Nakagawa (1996) however

What is the language like grammatically?

i have no idea and could not find any useful information

What is the language like phonologically?

Gǀui has five modal vowels, a e i o u, three nasal vowels, ã ẽ õ, and two pharyngeal vowels, aˤ oˤ. There are diphthongs o͜a and o͜aˤ, but they are allophones of o. Gǀui also has breathy-voice vowels, but they are described as part of the tone system.

Clicks are the most salient feature of the language, and its inventory is impressive (source: Nakagawa 1996):

What made you choose the language?

This was a self-challenge: I wanted a language from Botswana (where I had a penpal in the 1980s/90s) and randomly selected [i.e. took my glasses off and clicked] ||Gana on the glottolog map.

Resources:

https://glottolog.org/resource/languoid/id/gana1274

https://www.ethnologue.com/language/gnk

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/G%C7%81ana_language

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/G%C7%80ui_dialect

http://www.language-archives.org/language/gnk

http://endangeredlanguages.com/lang/596

Nakagawa (1996): An Outline of |Gui Phonology

https://repository.kulib.kyoto-u.ac.jp/dspace/bitstream/2433/68374/1/ASM_S_22_101.pdf

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fwd: Postdocs: CIBIO_Portugal.HumanEvolutionaryGenetics

Begin forwarded message: > From: [email protected] > Subject: Postdocs: CIBIO_Portugal.HumanEvolutionaryGenetics > Date: 4 October 2019 at 06:33:09 BST > To: [email protected] > > > > The Human Evolutionary Genetics group at CIBIO is currently accepting > applications to fill two 15 months contracts for PhD researchers to work on > the analysis of genomic/linguistic data and on computational modelling aiming > at the development of evolutionary and demographic models to infer the > demographic history of the Khoe-Kwadi language dispersal, at CIBIO-ICETA- > Research Centre in Biodiversity and Genetic Resources, Porto, Portugal. > > Preferred candidates must possess a PhD a relevant discipline (e.g. > population genetics, computational biology, quantitative linguistics, > statistics, bioinformatics, evolutionary genetics), and > > I. Solid background in computational / statistical skills > II. Previous experience in the field of human evolutionary history and > population genetics or linguistics > > Please see more details using the link: > > https://ift.tt/2ocVFQd > > The applications are formalized at the electronic address > https://ift.tt/3576JPB > > with following documents in a digital form, in PDF format: > > i) Curriculum vitae; > ii) Motivational Letter; > iii) Qualifications Certificate; > iv) Other relevant documentation > > > *Deadline for application submission is October 30th, 2019. > > > Jorge Rocha, Principal Researcher > > CIBIO - Research Centre in Biodiversity and Genetic Resources > Campus Agrario de Vairao, Rua Padre Armando Quintas > 4485-661 Vairao, Portugal > > > Magda Gayà >

via IFTTT

0 notes

Text

Khoe-Kwadi

https://allthingslinguistic.com/post/184998894180?utm_source=dlvr.it&utm_medium=tumblr

0 notes

Text

Ts’ixa grammar and dictionary

For those Tumblr folks roaming the internet in search for free language materials, I thought I’d share my work on Ts’ixa, a Kalahari Khoe (Khoe-Kwadi) language of northern Botswana. There are less than 300 speakers of Ts’ixa, many of whom are truly enthusiastic about their language.

I just uploaded the first draft of my community dictionary, which can be downloaded for free here.

The dictionary is a work in progress which I am currently developing with my local collaborators in Botswana.

It is a companion piece to the Ts’ixa grammar I finished in 2014. You can download the grammar here, but note that I completely changed my tonal analysis, meaning that the tone markings provided in the grammar are no longer up-to-date.

I cannot provide links for my other research papers, due to copyright restrictions, but if you message me on Researchgate or Tumblr, I will be happy to share the files with you.

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Khoe-Kwadi: Khwe

Part 3 of my Khoe-Kwadi series: Khwe

Family Overview

Kwadi

Khwe (or Khwedam)

Khwe is a dialect cluster belonging to the Kalahari Khoe subgroup of the Khoe-Kwadi family’s Khoe branch. According to the seminal Khoe classification by Vossen (1997), Khwe is most closely related to Naro and Gǀui-Gǁana, two Kalahari Khoe languages spoken in the Central Kalahari. However, more recent research suggests that Khwe may be closer to the geographically adjacent Kalahari Khoe languages Ts’ixa and Shua.

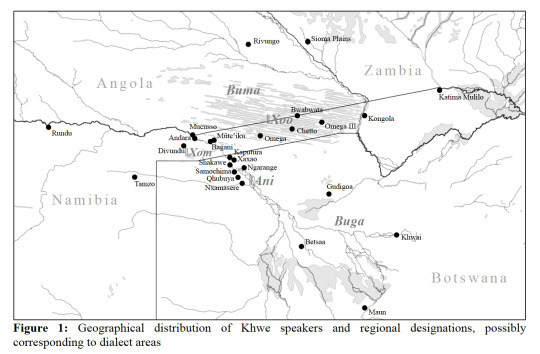

Where is it spoken?

Historically, Khwe speakers dwelt in a vast area reaching from southeastern Angola and western Zambia across the Namibian Caprivi strip into Botswana’s Okavango Delta. Only recent historical events like the civil war in Angola and the Namibian war of independence led to the present-day situation in which the majority of the 7,000–8,000 remaining speakers reside in the Bwabwata National Park of Namibia and along the Okavango panhandle in northwestern Botswana. Work-related migration, resettlement schemes and the establishment of National Parks during the second half of the 20th century further contributed to Khwe speakers abandoning their traditional settlements in favor of bigger villages close to the roadside.

(Map taken from Fehn 2019)

Where does the term “Khwe” come from?

The orthographic spelling “Khwe” derives from the root *khoe ‘person’, which is shared by all Khoe languages and ultimately gave its name to the language family. The Kwadi branch of the Khoe-Kwadi family has *kho ‘person’, suggesting that the -e ending is a suffix, possibly the common gender plural suffix -(ʔ)e still retained in Kwadi. To distinguish the Khwe dialect cluster from the Khoe language family, it was first spelt <Kxoe> by the linguist Oswin Köhler, and later - in agreement with the community - <Khwe>.

Are there dialects of Khwe?

There are two main subgroups within the Khwe cluster: Khwe “proper” and ǁAni. Due to the current sociolinguistic situation which favors dialect leveling, the dialectal diversity within Khwe may be underestimated by most scholars studying the language. Within Khwe “proper”, at least three varieties (ǁXom, ǁXoo and Buga) can be distinguished by phonological, lexical, and possibly also structural isoglosses. It has also been suggested that there are two sub-branches of ǁAni, a western and an eastern variety. We know very little about the Khwe variants spoken in Angola before the war, but some word lists recorded by the South African scholar E.O.J. Westphal suggest that they may have been phonologically and lexically distinct from the well-studied variety now predominant in the West Caprivi (ǁXom).

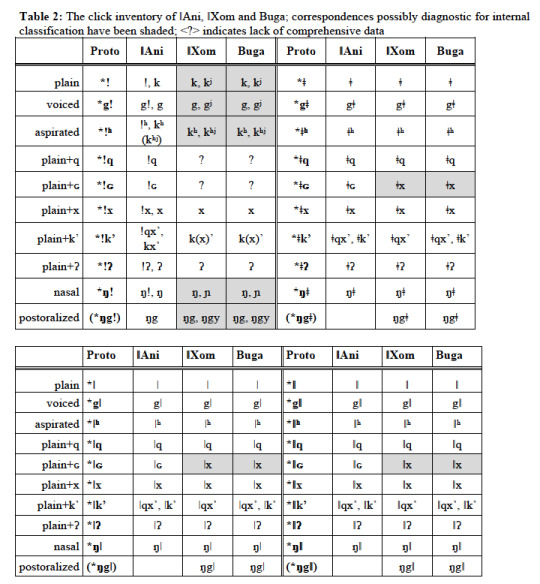

What does it sound like?

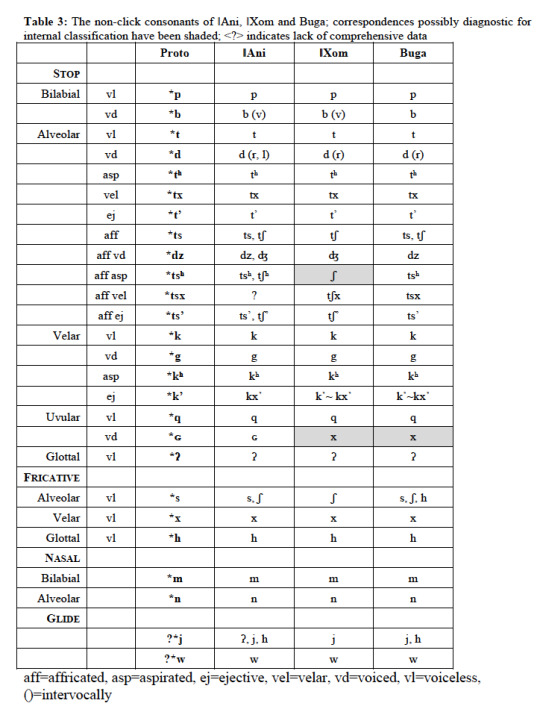

Different Khwe varieties have different phoneme inventories. Here’s a comparison of three varieties for which sufficient data is available (ǁXom, Buga and ǁAni):

(Tables taken from Fehn 2019)

While ǁXom and Buga have lost the alveolar click and replaced it by a velar or palatal stop (safe for some relic forms), ǁAni retains most of its alveolar clicks.

Although the phoneme inventory of Khwe is fairly large from a cross-linguistic perspective, it is smaller than that of Kalahari Khoe languages spoken in and around the Central Kalahari (Gǀui-Gǁana, and Naro), and substantially smaller than the phoneme inventories found in the southern African click-language families Kx’a and Tuu.

Typological features

In Khwe, the basic word order is SOV, but pragmatic considerations allow for both SVO and OSV. The basic constituent order in the noun phrase is head-final. Nouns in Khwe are optionally marked by portmanteau morphemes encoding person, gender and number (PGN). These clitics serve the function of specific articles and attach to about 75% of the language’s noun phrases. Like other Khoe languages, Khwe has a rich suffixing morphology: Derivational suffixes attach to both verbs and nouns, and a subset of the language’s tense-aspect morphemes is linked to the verb stem via a so-called juncture morpheme. Khwe distinguishes between two juncture morphemes triggering different morpho-tonological processes, one for NON-PAST and one for PAST. Khwe has nine suffixes marking tense-aspect, four in the domain of non-past, and five past-tense markers.

The direct object may optionally be marked by the postposition ʔà, which interacts with the argument’s information-structural properties. Oblique (peripheral) participants are obligatorily marked by a set of semantically specified postpositions. Khwe distinguishes between four syntactic verb classes, according to the number of core participants they may take: intransitives, transitives, ditransitives, and S/O-ambitransitives. Predicates may be simple or complex. Complex predicates display semantic features similar to serial verb constructions and involve two or more verbs, which are connected by the juncture morpheme.

Literature (just a small selection - there is lots of published literature on Khwe)

Brenzinger, Matthias. 1998. Moving to survive: Kxoe communities in arid lands. In Mathias Schladt (ed.), Language, identity, and conceptualization among the Khoisan, 321–357. Cologne: Rüdiger Köppe.

Fehn, Anne-Maria. 2019. Phonological and Lexical Variation in the Khwe Dialect Cluster. Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft 169(1): 9–39.

Heine, Bernd. 1999. The ǁAni: Grammatical notes and texts. Cologne.

Kilian-Hatz, Christa. 2003. Khwe Dictionary with a supplement on Khwe place-names of West Caprivi by Matthias Brenzinger (Namibian African Studies, 7). Cologne: Rüdiger Köppe.

Kilian-Hatz, Christa. 2008. A grammar of modern Khwe (Central Khoisan) (Research in Khoisan Studies, 23). Cologne: Rüdiger Köppe.

Köhler, Oswin. 1981. La langue kxoe. In Jean Perrot (ed.), Les langues dans le monde ancien et moderne, première partie: Les langues de l’afrique subsaharienne, 483–555. Paris: Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique.

Schladt, Mathias. 2000. A Multi-Purpose Orthography for Kxoe: Development and challenges. In Herman M. Batibo & Joseph Tsonope (eds.), The State of Khoesan Languages in Botswana, 125–139. Gaborone: Tasalls.

Vossen, Rainer. 1997. Die Khoe-Sprachen: Ein Beitrag zur Erforschung der Sprachgeschichte Afrikas (Research in Khoisan Studies, 12. Vol. 12. Cologne: Rüdiger Köppe.

Vossen, Rainer. 2000. Khoisan languages with a grammatical sketch of ǁAni (Khoe). In P. Zima (ed.), Areal and Genetic Factors in Language Classification and Description: Africa South of the Sahara, 129-145. Munich. Lincom.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Khoe-Kwadi, rated according to me

I decided to rate languages of the Khoe-Kwadi family according to a set of unspecified criteria. Because... why not?

Khoekhoe (Nama-Damara): Khoe language with highest number of speakers. Also literature and radio programs. Curiously, the most recent grammatical description is from 1977. There are many clicks and a syntactic structure quite different from what is seen in other languages . Contact influence from now extinct !Ui languages. Probably the most accessible member of the family, if you’re inclined to learn a Khoe-Kwadi language. 8/10

Naro: Some parts of the syntax suggest this is Khoekhoe in disguise. I have no idea what their 8 different pronominal paradigms are for, but given the confusing orthographical conventions used to write this language, I’m afraid I’ll never find out. Apart from the decision to write clicks as <c, x, tc, q> to match Bantu orthographies, there are no clues provided as to what is a particle, a clitic, or a suffix. Probably an exciting language, but I simply lack the patience to decipher the existing materials. 7/10

Gǀui-Gǁana: A lot of consonants… really, A LOT. Also, pharyngealized vowels and an elaborate aspect system that allows you to convey whether you performed an action standing, sitting or lying down (might come in handy, who knows?). Complex predicates galore. Would like to know more, but the consonants scare me. 8/10

Khwe: Is trying hard to become a synthetic language, and I suspect speakers of related languages have no idea what’s going on with their TAM system. An outlier in every respect, from lexicon to morphosyntax. Intriguingly wide historical historical distribution, from southeastern Angola into northern Botswana. Unfortunately, most materials available for this language are from a single dialect, so more research on other varieties will certainly yield exciting results. 9/10

Ts’ixa: Their preferred term of self-reference means “people with butts”, and I love it. Probably a remnant of a bigger dialect cluster. Syntax somewhere between SOV and SVO pattern, crazy embedding strategies, complex predicates you’ll need a week to figure out. Also a classification problem. They’re the rebels of the family. 10/10

Shua: Click loss and no overt nominal gender marking, so it’s understandable Khoisanists get skeptic just looking at the surface. But beware of twisted syntactic possibilities in present indicative clauses. I am intrigued by the hidden complexity and the absolutely confusing dialectal situation where any term of self-reference can be a clan, a language, or simply your favorite waterhole. Underrated underdog! 9/10

Tshwa: We know next to nothing about this subgroup. Probably the term lumps two different, not even very closely related, dialect clusters. Case and morphological marking of a focus slot appear to be important somehow. Has been progressively ignored by researchers, for reasons similar to those listed for Shua. Will probably yield interesting surprises if studied in the future. 8/10

Kwadi: Has been pronounced dead in the 1950s, but rememberers still keep popping up. A bit of a linguistic zombie. Clearly related to Khoe, but more of a distant cousin that came late to the party than an actual sister branch (IMO). Possibly also involves one or more substrates. Available mostly through the rough field notes of linguist EOJ Westphal, so studying this language involves a good deal of code breaking. 8/10

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

I was only working on a quick sketch grammar of the Shua dialect cluster and ended up wanting to do an entire reclassification of the Kalahari subgroup of the Khoe language family

I never thought that different orthographies and different methodological approaches can make languages look more different than they actually are.

Plus, apparently, previous research took into account some non-linguistic criteria, according to which the proper hunter-gatherers conforming to the “San” stereotype go into one subbranch (West) and all the rest goes into the other (East). Subsequently, it is claimed that the Eastern branch is somehow diluted by contact with Bantu-speaking peoples, hence the languages are no longer pure and irreversibly impoverished (as are the people and their culture...).

The only Kalahari Khoe language spoken by dark-skinned peoples following multiple subsistence patterns that underwent click loss and was still allowed to go into the Western branch is Khwe, supposedly because Oswin Köhler, the big anthropologist working on the people and the language, worked very hard to turn them into “real” San...

I now want justice for the peoples classified as “eastern” and their languages. As it is, any linguistic or cultural deviation from what is known from the Central Kalahari is still seen as “loss” or “dilution”, and it’s just bad and harmful. Especially for the speech communities who receive less attention from governments, NGOs and researchers, simply based on the fact that they do not correspond to an exotized stereotype from the early 20th century.

#Khoe-Kwadi classification#my current work#though this has been one of my pet peeves since I started working on Khoisan#I think that part of the historical work that has been done was heavily influence by extralinguistic factors#as is the data coverage#there is hardly any data from dark-skinned Khoe speaking foragers except for Khwe and Ts'ixa

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Makgadikgadi Pans National Park near Nata in northeastern Botswana.

The pans are remnants of an ancient lake which covered an area as vast as Switzerland. They occasionally flood during the rainy season and host a remarkable variety of wildlife. Recent research (which you should take with a grain of salt) suggests that Makgadikgadi is the cradle of humanity.

Before the establishment of the Makgadikgadi and Nxai Pan National Parks, the arid plains were home to hunter-gatherers speaking various dialects of the Khoe-Kwadi language Shua. They have since been resettled and now live in towns and villages close to the roadside where they suffer from social and economical marginalization.

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

▲▼▲ THE LANGUAGES OF SOUTH AFRICA ▲▼▲

AND THEIR RELATIONSHIPS TO OTHER LANGUAGES

★ Official languages : Afrikaans, English, isiNdebele, Sesotho, Sesotho sa Leboa, Setswana, siSwati, Xitsonga, Tshivenḓa, isiXhosa, isiZulu

☆ Dutch : a former official language (until 1984)

☆ |Xam : language of the National Motto !ke e: /xarra //ke (‘diverse people unite’ or ‘unity in diversity’)

☆ Khoekhoegowab (Nama) : the first of the so-called Khoisan languages to be added to the school curriculum (in the Northern Cape province)(x)

the Khoikhoi and the San/Bushman are the indigenous peoples of Southern Africa. their languages form part of three families : Khoe-Kwadi, Tuu and K’xa, and are characterised by the large number of click phonemes. the three families were previously grouped together as the ‘Khoisan’ languages.

during the Bantu Expansion, Bantu-speaking peoples spread across much of the continent, and reached southern Africa around the 3rd or 4th Century. Bantu languages are known for their extensive noun-class systems, and due to contact with the Khoe, Tuu and K’xa languages, languages like isiXhosa, isiZulu and Sesotho have acquired a few click phonemes too.

in 1652, the Dutch East-India Company (VOC) established a permanent settlement at the Cape of Good Hope. many Dutch settlers declared themselves vrÿburghers (free citizens), cutting themselves off from the VOC and the Netherlands. the Dutch spoken by these vrÿburghers (later Boers) and their Malay slaves would eventually evolve into Afrikaans. in 1814, the British acquired the Cape and thence set out to colonise much of the African continent, introducing English as an official language

#languages#langblr#african languages#south africa#bantu languages#khoisan languages#afrikaans#khoekhoegowab#xhosa#zulu#sesotho#map#I mainly focused on living languages for the trees#and on the main dialects/ macro-dialects#so this is not an exhaustive list#also#I've linked to wikipedia articles#mine#I labelled the map and made the family trees#so any errors are my fault#pls do no hesitate to correct me (in a friendly manner)

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Postdoc: CIBIO_Portugal.HumanEvolution

The Human Evolutionary Genetics group at CIBIO is currently accepting applications to fill a 30 months contract for a PhD researcher under a work contract for a non-fixed term to work on computational modeling aiming at the development of evolutionary and demographic models using genetic/linguistic data to infer the demographic history of the Khoe-Kwadi language dispersal, at CIBIO-ICETA- Research Centre in Biodiversity and Genetic Resources, Porto, Portugal. Preferred candidates must possess a PhD a relevant discipline (e.g. population genetics, computational biology, quantitative linguistics, statistics, bioinformatics, evolutionary genetics), and I. Solid background in computational / statistical skills II. Previous experience in the field of human evolutionary history and population genetics or linguistics Please see more details using the link: http://www.eracareers.pt/opportunities/index.aspx?task=showAnuncioOportunities&jobId=114157&idc=1 The applications are formalized at the electronic address http://www.cibio.pt with following documents in a digital form, in PDF format: i) Curriculum vitae; ii) Motivational Letter; iii)Qualifications Certificate; iv) Other relevant documentation *Deadline for application submission is May 29th, 2019. Jorge Rocha, Principal Researcher CIBIO - Research Centre in Biodiversity and Genetic Resources Campus Agrario de Vairao, Rua Padre Armando Quintas 4485-661 Vairao, Portugal Magda Gayà

0 notes

Text

Khoe-Kwadi

http://allthingslinguistic.com/post/184998894180?utm_source=dlvr.it&utm_medium=tumblr

0 notes