#Khwe

Text

Table of the particles (ʔ)e, re, and (-ʔ)o in a number of African languages with description of the function(s) related to clause type marking in each language: vocative (VOC), imperative (IMP), interrogative (INTER), declarative (DECL) or subordination (SUB).

Fehn, Anne-Maria. 2024. “K’ui tii ‘Don’t speak!’ – Morphology and syntax of commands in Ts’ixa (Kalahari Khoe) and beyond”, Linguistique et langues africaines [Online], 10(1). URL: http://journals.openedition.org/lla/13288; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/123pu

#african language#Anne-Maria Fehn#clause#syntax#morphology#particles#Linguistique et langues africaine#linguistics#2024#Khwe#Ts'ixa#Shua#Tshwa#G|ui-G||ana#Naro#Nama#Hai||om#!Ora

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sarwa boy playing the guitar

7 notes

·

View notes

Note

hi, I know you're not too active on this blog anymore so I hope I'm not bothering. but I was wondering if you had info or sources to share about traditional Khoe and Bushman/San musical instruments ?

I also have a few more specific questions but don't just want to bombard you with them. would you mind if I sent them through in case you can point me in the right direction ?

Hi there,

thanks a lot for the message - and no worries, you're not bothering me at all :-) I once had that idea that I should blog more about my work / fieldwork, but the moment I step into Namibia/Botswana, I usually get so busy meeting people and doing things that I barely pay attention to my mail anymore ;-)

I admit I am not a super big expert on San music, but I do have recordings from various communities (Ts'ixa, Khwe, ||Ani and Tjwao) and I have a rough idea of the literature. Just go ahead with your questions and I see whether (and how) I can help you.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

SAN PEOPLE: THE WORLD’S MOST ANCIENT RACE/PEOPLE, OUR ANCESTORS.

They predate Christianity and Islam by at least 18,000 years! Why is this not taught in the schools of the world ?

The San 'Bushmen' also known as Khwe, Sho, and Basarwa are the oldest inhabitants of southern Africa, (and are part of the Khoi and San groups), where they have lived for at least 20,000 years. They are hunter-gatherer peoples of southern Africa. Genetic evidence also suggests the San Bushmen are one of the oldest peoples in the world. Their home is in the vast expanse of the Kalahari desert.

They are found in Botswana, Namibia, South Africa, Zambia, Zimbabwe and Angola, with loosely related groups in Tanzania.

Recorded history also placed them in Lesotho and Mozambique. Rock art and archaeological evidence can place them as far north as Libya, Egypt, Sudan and Ethiopia, with the evidence of legend and racial type suggesting some traces remain.

“Hottentot” (British and South African English) is a derogatory term historically used of the Khoikhoi, the non-Bantu indigenous nomadic pastoralists of South Africa.

The term has also been used to refer to the non-Bantu indigenous population as a whole, now collectively known as the Khoisan. Use of the term is now deprecated and considered offensive, the preferred name for the non-Bantu indigenous people of the Western Cape area being Khoi, Khoikhoi, or Khoisan.

The Khoi people also fought and defeated the British settlers. That’s why the Europeans derogatorily called them “Cannibals”, like they insulted all the native peoples of the world whose land they stole at gunpoint, with the help of the Christian missionaries/Islam and the Bible/Koran.

#BlackHistoryMatters #southafrica #sanpeople #bushmen #sarahhistorichomie

20 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The traditional leaders of three San groups in southern Africa have released an ethical code of conduct for researchers who wish to study the groups’ culture and biology.

The code of conduct was issued in early March from the !Xun, Khwe and !Khomani group leaders and encourage scientists to submit research proposals to be reviewed by a panel of community members.

One individual in particular was concerned with the fact that researchers come out of these studies enriched in San culture and knowledge, but San communities do not receive any benefits for allowing researchers to study them.

76 notes

·

View notes

Note

Chocobo/bird themed pronouns for prompto argentum, all based off of the chocobo wikipedia page because I know nothing about chocobo:

fea/ther/ther/thers/feaself

kweh/kweh/kwehs/khwes/khweself

gys/ahl/ahls/ahls/gyself

fly/fly/flys/flys/flyself

cho/co/chocos/chocos/choself

egg/egg/eggs/eggs/eggself

wing/wing/wings/wings/wingself

ok first thank you so much for actually going thru our system carrd I know it’s a headache and thank you so much for giving us some pronouns 🥺 we’ll keep these in mind for when he’s next around and see what he thinks!!! thank you so much!!!!!

#long post#thank you so much once again#I’ll put this under prom’s tag so he can find it later#prompto.txt

0 notes

Photo

MEDIA RELEASE 11 JUNE 2017

Strongest Visual Arts Festival Programme in South Africa for 2017

The visual arts programme of the 2017 Vrystaat Arts Festival is one of the most technically sophisticated and internationally engaged offerings on the South African festival calendar this year. From First Nations’ prints and interactive media art sculptures, to ecology focussed, robotic installations, through to retrospective shows of well-known South African artists and exhibitions of emerging and mid-career practitioners, this year’s festival has it all.

Ons kom vanaf ons stories/We Come from our Stories (18 July - 22 July 2017, Pluimbal Hall)

In 2017, the Vrystaat Arts Festival presents Ons kom vanaf ons stories (We Come from Our Stories). Ons kom vanaf ons stories is a print portfolio that visually retells traditional stories from the !Xun and Khwe First Nations peoples. The project was realised through a partnership between Free State Arts & Health, the National Association of Childcare Workers (NACCW) in Kimberley, Isibindi Youth Centre in Platfontein and the William Humprey Art Gallery (WHAG) in Kimberley. The prints were made by young artists from Platfontein as part of an intergenerational cohesion project that facilitates the transfer of cultural narratives from the older generation to the younger. In this way the programme is making a huge contribution to the conservation of First Nations languages, culture and heritage and creates a new generation of story tellers and/or artists, which is one of the main aims of the festival.

Giidanyba (Sky Beings) Tyrone Sheather (16 July - 30 July 2017 Oliewenhuis Art Gallery)

Giidanyba (Sky Beings) consists of seven figure-like sculptures, depicting nocturnal spirits that impart knowledge and guidance to the First Nation, Gumbaynggirr people of Australia. The Giidanyba transforms from unlit statues in the daytime to bright, shimmering beings in the evening. Emanating from within these spirit-like forms, are sounds and lights that are responsive to the movement of audiences. Tyrone Sheather, an Australian artist belonging to the Gumbaynggirr people from the mid-north coast of New South Wales, aims to explore identity and to reveal, through a combination of traditional and contemporary media, knowledge and stories that have been passed down over centuries within the Gumbaynggirr Dreamtime. Sheather explains: “In the Dreaming (Yuludarla), the Hero-Ancestors made and transformed the landscape with their special powers of creation and destruction. Simulating a Gumbaynggirr rite of passage, Giidanyba symbolises these Spiritual Ancestors, as they descend from the Muurrbay Bundani (tree of life) in the sky, to support people throughout their cultural journey and to guide them into the next stage of their lives.” Giidanyba is presented by Situate Art in Festivals, Tasmania as part of a First Nations project of the Programme for Innovation in Artform Development (PIAD), and initiative of the festival and the University of the Free State and supported by Oliewenhuis Art Gallery.

The Mesh Keith Armstrong (17 July - 11 Aug 2017, Stegmann Gallery)

The Mesh is an interactive, experiential solo exhibition by Dr Keith Armstrong. The five artworks on exhibition each investigate how a ‘mesh’ of environmental, social and cultural ecologies form our worlds, asking how we might re-imagine our place and actions within those networks through the lens of ‘re-futuring’ (i.e. concerted actions that help increase time left in the future). Retrospective works are shown together with international premieres. These include a sculptural text-based work O Tswellang, arising from collaborations with ‘change agents’ in the informal townships around Bloemfontein as part of the Seven Stage Futures project, presented during festival time in local informal settlements. Another of the five works, the international premiere of Eremocene (Age of Loneliness), reveals a mysterious, internally glowing creature, witnessed from several different vantage points and views. Traveling ethereally through a darkened tank this form is entwined with a dynamically evolving soundscape, suggesting a naturalised/artificially intelligent form, ambiguously isolated at the edges of fluid consciousness. The exhibition also sees the re-development of innovative video installations such as Shifting Dusts, originally commissioned for the Institute for Contemporary Arts (ICA) London in 2006, and Seasonal. Supported by Queensland University of Technology, Creative Lab Research Centre.

?Boek / Book? curated by Dead Bunny Society (17 July - 28 July, Centenary Arts Gallery, Centenary Complex, UFS)

In this exhibition the Dead Bunny Society explores a wide variety of manifestations of the book as an artwork. The genre is generally misunderstood as either a book that an artist works in or a visual diary. With this in mind the Dead Bunnies aim to explore the genre of book arts through the more accepted format of the artist book in a traditionally bound format as well as more alternative ways in which the book can take shape. The premise of the exhibition is to open up an understanding of the genre through exploring different methodologies in the binding and display process and will include the more traditional codex binding as well as the more alternative ways which would include the long stitch, secret Belgium binding, exposed spine bindings and single sheet binding to name but a few. The exhibition will also explore different ways in which an exhibition of this nature can be presented to the viewer, where the natural need to engage with a book through touching and turning the page will be encouraged as this forms one of the most important aspects of engaging with the book format.

[my] SELF curated by Angela de Jesus (17 July-22 July kykNET-Scaena Foyer)

In the exhibition [my] SELF artists explore the complexities of identity and belonging over the backdrop of our social, political and cultural climate. Using their own body as subject or point of departure, artists investigate issues of SELF in relation to language, race, religion and/or gender. The exhibition showcases works by local artists such as Sandy Little, Toni Pretorius, Gerrit Hattingh and Bonging Njalo alongside national artists like Angus Taylor. [my] SELF is the third addition of three exhibitions following the exhibition [my] PLACE in 2015 and [my] OBJECT in 2016. In the exhibitions artists have been invited to create works that explore land ownership, personalised inanimate objects and identity.

’n Terugblik Ben Botma (18 July - 27 Aug, Oliewenhuis Art Gallery)

Ben Botma quotes Chuck Palahniuk: “The unreal is more powerful than the real. Because nothing is as perfect as you can imagine it. Because it’s only intangible ideas, concepts, beliefs, fantasies that last. Stone crumbles. Wood rots. People, well they die. But things as fragile as a thought, a dream, a legend, they can go on and on.” Art, architecture, music, poetry - these are the manifestations of human dreams, fears, spirituality, thoughts. In these works local artist Botma is searching for an underlying subconscious line between some of these cultural manifestations. Included in this exhibition will be a selection of works from his student days until today, in a variety of media.

Carceral Spaces: Anticpating the sublime... Marieke Kruger (18 July - 20 Aug, Oliewenhuis Arts Gallery)

“An exploration of the sublime through the power of suggestive drawing trace towards the transformation of the self and the other.” In her body of drawings the artist specifically explores the transformative power of suggestion as a means of containing a certain presence which could lead to an experience of the sublime – specifically the awesome in drawing. Kruger focuses on large scale portrait drawings of the self and the other (in this case, prison inmates with whom she interacts) and its particular relationship to space thereby creating a means through which the psychological and spiritual effect of the sublime in drawing is explored, as well as the drawing’s subsequent transformative effect on the self and the other. Marieke Kruger is currently reading and researching towards a proposed PhD study on the sublime and its transformative effects on the self and the other through the power of large scale suggestive drawing trace.

Propitas Miné Kleynhans (18 July - 20 Aug, Oliewenhuis Arts Gallery)

The artworks in this exhibition flirt with contemporary marketing and poke fun at ideas about property and consumer products. The commercial offer made by these works target prevalent attitudes, expectations and desires in the average middle class household in a satirical yet solitary way. The works play imaginatively with elements from the insurance, security, marketing and spiritual industry by ways of the design of semi-commercial products with fictional pseudo-transcendental aspirations. The works speak thematically to, and about, human desires regarding cherishing, surety, significance and enchantment in commercial as well as domestic spheres. Min. Kleynhans is a local artist and final year Master of Fine Arts student at the University of the Free State.

The Elements of Incarnation I-IV Janna Kruger (18 July - 20 Aug, Oliewenhuis Arts Gallery)

The Elements of Incarnation I-IV is an exhibition of reinforced concrete sculptures accompanying the exhibition by Marieke Kruger in the Reservoir. Janna Kruger employs the process of sculpting to distil and elucidate spiritual notions and influences affecting his life. He then consolidates these abstract findings into tangible monuments as ‘beacons’ of reminiscence, deliberation and/or instruction. He was the winner of the Sculpture category of the 2015/2016 PPC Imaginarium Awards.

Air Cabinet Peter Burke (Hoffman Square 18 - 20 Jul 09:30 – 16:00. Part of Public Art Projects - PAP)

Air Cabinet is a ‘community service’ intended to generate discussion around the value of air. It features a public stall, a ‘doctor’ and a cabinet of small glass test tubes containing individual samples of the human breath. Visitors to PAP will be invited to donate, sell or swap their breath in a discursive installation. The ‘doctor’ (Peter Burke) broadcasts questions about air over a megaphone and draws the public into a lively and off-the-cuff debate about the value of air. ‘Donors’ from the general public will be invited take part in an intimate ‘test’ that involves filling a test tube with a single breath. Their unique sample will be permanently sealed, labelled and dated for display in a museum-style cabinet. They may give their air a descriptive title such as ‘the breath of love’, ‘the air of enthusiasm’ or ‘hot air’. Over the span of the festival an estimated 300 samples will be collected. They will form an ongoing installation that aims to provoke conversations about the significance of the human breath. The project expands explorations of air by Marcel Duchamp in his glass vial containing Air de Paris (50 cc of Paris Air) (1919).

Are we the one? Keith Armstong (UV-kampus / UFS Campus. Part of Public Art Projects - PAP)

A collaborative, performative and relational experience for two people, woven together by a custom digital phone app. Two walkers, who have never met, simultaneously use a phone app to record a personalised walk around their locality, crafting a series of special moments and surprises for each other. The app then allows participants to continue their two walks, but now directed by what the other person has just created for them. Finally, at the end of the experience they can then choose whether they would actually like to meet in person. Take part: [email protected] Commissioned by Arts House through the Australia Council for the Arts’ New Digital Theatre Initiative. Arts House is a program of the City of Melbourne.

Live Art

South African artists work, all participants of the biannual OPENLab interdisciplinary laboratory of the PIAD, include In These Streets by Wezile Mgibe, a live art and dance performance which speaks about his personal journey of self-discovery; PIE: Planning Impossible Errors by Ella Ziegler, Karin Tan, Skye Quadling and friends around the phenomenon of unexpected errors; and 29°06ʹS 26°13ʹE by Lhola Amira and Vasiki Creative Citizens, a performance work that explores significant past and present narratives in South Africa including The Cattle Killing of 1857, Ukuzika kuka Mendi of 1917 and the Shimla Park Brawl at the University of the Free State in 2016. Other projects part of the PIAD in 2017 include international work such as OnesieWorld by Adele Varcoe, which sees 1,000 onesies designed and made by fashion students and manufacturers in Bloemfontein given away to festival goers; and Dr Keith Armstrong’s Seven Stage Futures, a series of events created by local ‘change-agents’ part of Qala Phelang Tala (Start Living Green), set in informal settlements in and around Bloemfontein/Mangaung designed as community-led Meraka or gathering spaces.

Connected Vian Roos and Anneli Groenewald (Scaena Restaurant and Pluimbal Hall, 17 July - 22 July)

Connected is a visual arts vrynge exhibition. A photographic series by Vian Roos, the exhibition explores the different ways in which couples have relationships, whether a traditional heterosexual relationship, a homosexual relationship, a cross-cultural relationship or a relationship between individuals with large age gaps, among others. The portraits work in tandem with text by Anneli Groenewald, that documents and contextualises the realities of the relationships behind each image. The collaboration works to undermine prejudices that often underlie dislike and resentment towards so-called ‘nontraditional’ relationships.

For further inquiries contact:

Roxanne Konco Angela de Jesus

Marketing Manager Director Stegmann Gallery

Tel: +27 (0)51 404 7947 [email protected]

Tel: +27 (0)51 401 2706 [email protected]

#vrystaat kunstefees#vrystaat arts festival#vrystaat tsa-botjhaba#PIAD17#university of the free state#Volksblad

1 note

·

View note

Photo

These irresistible baskets are made by a small community of Khwe Bushmen in Northern Namibia, Southern Africa. Traditionally used for collecting veld food this almost extinct style of basket was recently revived thanks to the intervention of NGOs in the country. They are made in very limited numbers and are sometimes available for purchase through Design Afrika in Cape Town. Photo ©afrikani

www.designafrika.co.za

#African basket#Africa#Namibia#Khwe#bushman#handmade#khoisan#traditional craft#weaving#basket#first peoples

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Khoe-Kwadi: Khwe

Part 3 of my Khoe-Kwadi series: Khwe

Family Overview

Kwadi

Khwe (or Khwedam)

Khwe is a dialect cluster belonging to the Kalahari Khoe subgroup of the Khoe-Kwadi family’s Khoe branch. According to the seminal Khoe classification by Vossen (1997), Khwe is most closely related to Naro and Gǀui-Gǁana, two Kalahari Khoe languages spoken in the Central Kalahari. However, more recent research suggests that Khwe may be closer to the geographically adjacent Kalahari Khoe languages Ts’ixa and Shua.

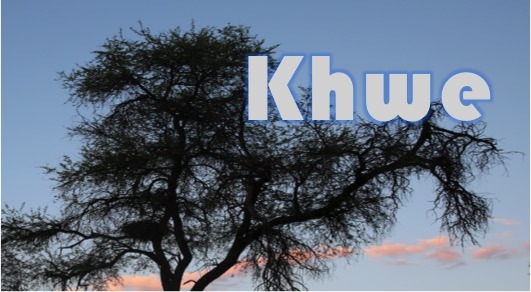

Where is it spoken?

Historically, Khwe speakers dwelt in a vast area reaching from southeastern Angola and western Zambia across the Namibian Caprivi strip into Botswana’s Okavango Delta. Only recent historical events like the civil war in Angola and the Namibian war of independence led to the present-day situation in which the majority of the 7,000–8,000 remaining speakers reside in the Bwabwata National Park of Namibia and along the Okavango panhandle in northwestern Botswana. Work-related migration, resettlement schemes and the establishment of National Parks during the second half of the 20th century further contributed to Khwe speakers abandoning their traditional settlements in favor of bigger villages close to the roadside.

(Map taken from Fehn 2019)

Where does the term “Khwe” come from?

The orthographic spelling “Khwe” derives from the root *khoe ‘person’, which is shared by all Khoe languages and ultimately gave its name to the language family. The Kwadi branch of the Khoe-Kwadi family has *kho ‘person’, suggesting that the -e ending is a suffix, possibly the common gender plural suffix -(ʔ)e still retained in Kwadi. To distinguish the Khwe dialect cluster from the Khoe language family, it was first spelt <Kxoe> by the linguist Oswin Köhler, and later - in agreement with the community - <Khwe>.

Are there dialects of Khwe?

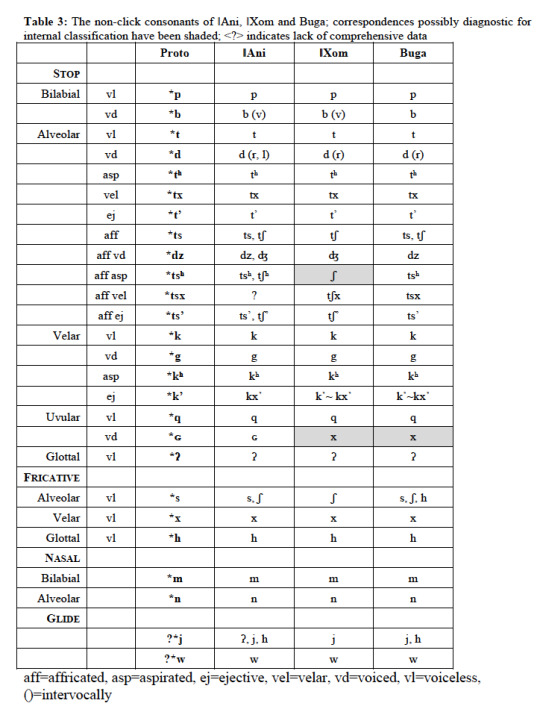

There are two main subgroups within the Khwe cluster: Khwe “proper” and ǁAni. Due to the current sociolinguistic situation which favors dialect leveling, the dialectal diversity within Khwe may be underestimated by most scholars studying the language. Within Khwe “proper”, at least three varieties (ǁXom, ǁXoo and Buga) can be distinguished by phonological, lexical, and possibly also structural isoglosses. It has also been suggested that there are two sub-branches of ǁAni, a western and an eastern variety. We know very little about the Khwe variants spoken in Angola before the war, but some word lists recorded by the South African scholar E.O.J. Westphal suggest that they may have been phonologically and lexically distinct from the well-studied variety now predominant in the West Caprivi (ǁXom).

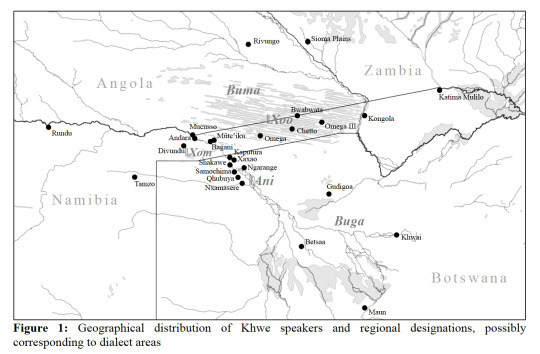

What does it sound like?

Different Khwe varieties have different phoneme inventories. Here’s a comparison of three varieties for which sufficient data is available (ǁXom, Buga and ǁAni):

(Tables taken from Fehn 2019)

While ǁXom and Buga have lost the alveolar click and replaced it by a velar or palatal stop (safe for some relic forms), ǁAni retains most of its alveolar clicks.

Although the phoneme inventory of Khwe is fairly large from a cross-linguistic perspective, it is smaller than that of Kalahari Khoe languages spoken in and around the Central Kalahari (Gǀui-Gǁana, and Naro), and substantially smaller than the phoneme inventories found in the southern African click-language families Kx’a and Tuu.

Typological features

In Khwe, the basic word order is SOV, but pragmatic considerations allow for both SVO and OSV. The basic constituent order in the noun phrase is head-final. Nouns in Khwe are optionally marked by portmanteau morphemes encoding person, gender and number (PGN). These clitics serve the function of specific articles and attach to about 75% of the language’s noun phrases. Like other Khoe languages, Khwe has a rich suffixing morphology: Derivational suffixes attach to both verbs and nouns, and a subset of the language’s tense-aspect morphemes is linked to the verb stem via a so-called juncture morpheme. Khwe distinguishes between two juncture morphemes triggering different morpho-tonological processes, one for NON-PAST and one for PAST. Khwe has nine suffixes marking tense-aspect, four in the domain of non-past, and five past-tense markers.

The direct object may optionally be marked by the postposition ʔà, which interacts with the argument’s information-structural properties. Oblique (peripheral) participants are obligatorily marked by a set of semantically specified postpositions. Khwe distinguishes between four syntactic verb classes, according to the number of core participants they may take: intransitives, transitives, ditransitives, and S/O-ambitransitives. Predicates may be simple or complex. Complex predicates display semantic features similar to serial verb constructions and involve two or more verbs, which are connected by the juncture morpheme.

Literature (just a small selection - there is lots of published literature on Khwe)

Brenzinger, Matthias. 1998. Moving to survive: Kxoe communities in arid lands. In Mathias Schladt (ed.), Language, identity, and conceptualization among the Khoisan, 321–357. Cologne: Rüdiger Köppe.

Fehn, Anne-Maria. 2019. Phonological and Lexical Variation in the Khwe Dialect Cluster. Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft 169(1): 9–39.

Heine, Bernd. 1999. The ǁAni: Grammatical notes and texts. Cologne.

Kilian-Hatz, Christa. 2003. Khwe Dictionary with a supplement on Khwe place-names of West Caprivi by Matthias Brenzinger (Namibian African Studies, 7). Cologne: Rüdiger Köppe.

Kilian-Hatz, Christa. 2008. A grammar of modern Khwe (Central Khoisan) (Research in Khoisan Studies, 23). Cologne: Rüdiger Köppe.

Köhler, Oswin. 1981. La langue kxoe. In Jean Perrot (ed.), Les langues dans le monde ancien et moderne, première partie: Les langues de l’afrique subsaharienne, 483–555. Paris: Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique.

Schladt, Mathias. 2000. A Multi-Purpose Orthography for Kxoe: Development and challenges. In Herman M. Batibo & Joseph Tsonope (eds.), The State of Khoesan Languages in Botswana, 125–139. Gaborone: Tasalls.

Vossen, Rainer. 1997. Die Khoe-Sprachen: Ein Beitrag zur Erforschung der Sprachgeschichte Afrikas (Research in Khoisan Studies, 12. Vol. 12. Cologne: Rüdiger Köppe.

Vossen, Rainer. 2000. Khoisan languages with a grammatical sketch of ǁAni (Khoe). In P. Zima (ed.), Areal and Genetic Factors in Language Classification and Description: Africa South of the Sahara, 129-145. Munich. Lincom.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

I was only working on a quick sketch grammar of the Shua dialect cluster and ended up wanting to do an entire reclassification of the Kalahari subgroup of the Khoe language family

I never thought that different orthographies and different methodological approaches can make languages look more different than they actually are.

Plus, apparently, previous research took into account some non-linguistic criteria, according to which the proper hunter-gatherers conforming to the “San” stereotype go into one subbranch (West) and all the rest goes into the other (East). Subsequently, it is claimed that the Eastern branch is somehow diluted by contact with Bantu-speaking peoples, hence the languages are no longer pure and irreversibly impoverished (as are the people and their culture...).

The only Kalahari Khoe language spoken by dark-skinned peoples following multiple subsistence patterns that underwent click loss and was still allowed to go into the Western branch is Khwe, supposedly because Oswin Köhler, the big anthropologist working on the people and the language, worked very hard to turn them into “real” San...

I now want justice for the peoples classified as “eastern” and their languages. As it is, any linguistic or cultural deviation from what is known from the Central Kalahari is still seen as “loss” or “dilution”, and it’s just bad and harmful. Especially for the speech communities who receive less attention from governments, NGOs and researchers, simply based on the fact that they do not correspond to an exotized stereotype from the early 20th century.

#Khoe-Kwadi classification#my current work#though this has been one of my pet peeves since I started working on Khoisan#I think that part of the historical work that has been done was heavily influence by extralinguistic factors#as is the data coverage#there is hardly any data from dark-skinned Khoe speaking foragers except for Khwe and Ts'ixa

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Talking about “Whites” in Khoisan

Inspired by this great post about Greenlandic, I thought it could be fun to make a post about how speakers of southern African “Khoisan” languages refer to white people.

The most widespread root to refer to white people in southern African “Khoisan” languages (Kx’a, Tuu, Khoe) is ǀhũũ. The presence of delayed aspiration, as well as the appearance of voicing in !Xun (gǀhũũ) suggests the form probably originated in either Kx’a or Tuu. So far, no etymology has been suggested. The only attested meaning of this root is ‘White person’.

A slightly more interesting case is Khwe (Kalahari Khoe) qo(w)a. Obviously, this is a borrowing (from Tswana lekgoa), but the etymologies commonly quoted to explain the origin of this term are so great I decided to include it here. The first hypothesis says that lekgoa derives from lewatle ‘ocean’ and go kqwa ‘to spit’, hence the meaning ‘those that were spit out by the ocean’. The second hypothesis suggests it is merely a nominalized version of go kgoa ‘to be impolite’… no additional explanation needed, I guess. I completely understand borrowing this term.

My favorite designations for white folks are both from Ts’ixa (Kalahari Khoe):

The more widespread term is the compound ǁʔau-khoe ‘fish-person’, sometimes simply shortened to ǁʔau ‘fish’. There are two explanations commonly given by the speakers: 1) White people look/feel like fish (legit, I guess); and 2) White people are like fish - they need water all the time. Also, the Ts’ixa really REALLY do not like fish, and they never eat it unless they absolutely have to. Although they now live in a riverine environment, they clearly identify as people of the savanna. I also wonder whether this could be a cross-reference to the Tswana etymology ‘those that were spit out by the ocean’, i.e., fish...

The second term nguu-ǀxoa-toe-khoe ‘people who move with a house’ is mostly used by older speakers. One lady explained to me that the first Whites her grandmother spotted were Afrikaners on their way from South Africa to Angola, some time in the 19th century. They were using covered wagons in which they were transporting their entire belongings, hence the moving house.

88 notes

·

View notes

Text

Would anyone be interested in me recording an online class on Khwe or Ts’ixa (both Kalahari Khoe, part of “Khoisan” aka “African click languages”)?

I have materials for both languages which I prepared for several university seminars I taught over the years. It’s not exactly a language class that will teach you how to speak, but depending on who’s interested, I could make it a little more “popular”, for example make a bigger introduction on Khoisan, click sounds, etc.

If you are interested, please like or message me with details on what you’d like to see.

34 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Dancing “Kavango Style”. Ethnic groups: Mbunza, Kwangali & Khwe. All pictures taken with permission.

The Mbunza and Kwangali live on the banks of the Kavango river in Namibia, speak closely related Bantu languages and subside on fishing and gardening. The Khwe are former hunter-gatherers who speak a Kalahari Khoe language (learn more) and once occupied a vast territory stretching from southeastern Angola into Botswana’s Okavango Delta.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Khoe-Kwadi, rated according to me

I decided to rate languages of the Khoe-Kwadi family according to a set of unspecified criteria. Because... why not?

Khoekhoe (Nama-Damara): Khoe language with highest number of speakers. Also literature and radio programs. Curiously, the most recent grammatical description is from 1977. There are many clicks and a syntactic structure quite different from what is seen in other languages . Contact influence from now extinct !Ui languages. Probably the most accessible member of the family, if you’re inclined to learn a Khoe-Kwadi language. 8/10

Naro: Some parts of the syntax suggest this is Khoekhoe in disguise. I have no idea what their 8 different pronominal paradigms are for, but given the confusing orthographical conventions used to write this language, I’m afraid I’ll never find out. Apart from the decision to write clicks as <c, x, tc, q> to match Bantu orthographies, there are no clues provided as to what is a particle, a clitic, or a suffix. Probably an exciting language, but I simply lack the patience to decipher the existing materials. 7/10

Gǀui-Gǁana: A lot of consonants… really, A LOT. Also, pharyngealized vowels and an elaborate aspect system that allows you to convey whether you performed an action standing, sitting or lying down (might come in handy, who knows?). Complex predicates galore. Would like to know more, but the consonants scare me. 8/10

Khwe: Is trying hard to become a synthetic language, and I suspect speakers of related languages have no idea what’s going on with their TAM system. An outlier in every respect, from lexicon to morphosyntax. Intriguingly wide historical historical distribution, from southeastern Angola into northern Botswana. Unfortunately, most materials available for this language are from a single dialect, so more research on other varieties will certainly yield exciting results. 9/10

Ts’ixa: Their preferred term of self-reference means “people with butts”, and I love it. Probably a remnant of a bigger dialect cluster. Syntax somewhere between SOV and SVO pattern, crazy embedding strategies, complex predicates you’ll need a week to figure out. Also a classification problem. They’re the rebels of the family. 10/10

Shua: Click loss and no overt nominal gender marking, so it’s understandable Khoisanists get skeptic just looking at the surface. But beware of twisted syntactic possibilities in present indicative clauses. I am intrigued by the hidden complexity and the absolutely confusing dialectal situation where any term of self-reference can be a clan, a language, or simply your favorite waterhole. Underrated underdog! 9/10

Tshwa: We know next to nothing about this subgroup. Probably the term lumps two different, not even very closely related, dialect clusters. Case and morphological marking of a focus slot appear to be important somehow. Has been progressively ignored by researchers, for reasons similar to those listed for Shua. Will probably yield interesting surprises if studied in the future. 8/10

Kwadi: Has been pronounced dead in the 1950s, but rememberers still keep popping up. A bit of a linguistic zombie. Clearly related to Khoe, but more of a distant cousin that came late to the party than an actual sister branch (IMO). Possibly also involves one or more substrates. Available mostly through the rough field notes of linguist EOJ Westphal, so studying this language involves a good deal of code breaking. 8/10

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

MEDIA RELEASE 30 JUNE 2017

WE COME FROM OUR STORIES: FREE STATE ARTS & HEALTH

Free State Arts & Health is a pioneering South African arts and health initiative that supports the involvement of the arts in the wellbeing of communities. The programme is a bi-lateral partnership of the Vrystaat Arts Festival and DADAA in Western Australia, supported by the Australia Council for the Arts and The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation through the Programme for Innovation in Artform Development (PIAD), an initiative of the festival and the University of the Free State (UFS).

Professor Francis Petersen, Vice-Chancellor of the UFS says: ‘Health and ability go hand in hand – and enabling our communities to participate in shaping and maintaining their well-being should be a priority for any institution. Especially for those institutions whose activity draws on the vitality and diversity of the communities that hosts them. This finds expression in the University of the Free State’s Human Project, on and off-campus. Our partnership with Free State Arts & Health is a valuable extension of the University’s mission to positively impact on society. The platforms and methods made available through this program is an asset to UFS and the province.’

HE Mr Adam McCarthy – Australian High Commissioner in Pretoria, South Africa comments: ‘We are very proud that Australian artists and arts organisations are partnernering with South African arts institutions to facilitate both cultural exchange and long-term, mutually beneficial arts and health programs. We share an interest in a peaceful and prosperous region and are committed to working with the countries of Southern Africa as a friend and partner.’

Rosemary Mangope, CEO of the National Arts Council of South Africa and Board Member of the International Federation of Arts Councils and Cultural Agencies (IFACAA), states: ‘Free State Arts & Health is an incredibly important pilot project for South Africa. It has the potential to upscale and impact significantly on both the arts and health communities of our country. We need to utilise the arts as a leading framework for a thriving future and health is primary to sustainability. The programme mobilises communities to raise the bar on their collective health and stimulates the growth of new cultural expression in Africa.’

Tony Grybowski, CEO of the Australia Council for the Arts says: ‘The Australia Council's Strategic Plan - A Culturally Ambitions Nation identifies reciprocity as a way to develop the arts globally and is proud to support international artist exchanges such as these to help practitioners share practices, develop new programs and build the profile of artists with disability at high profile international events. DADAA in Western Australia is a leading arts and disability organisation and through programs such as Free State Arts & Health they strengthen the South African and Australian arts industries by injecting new ideas and ways of thinking’

David Doyle, Executive Director of DADAA states: ‘Sometimes in my role I get to work on some extraordinary partnerships and this project is one. Its the partners shared passion for cultural inclusion and health impacts that is now gaining traction across the Free State due to the dedicated work of the Program Manager Mc Roodt and the project artists. Together we are forging a unique practice in Arts and Health across the Free State , that is uniquely South African. Working with the partners and project team has been an absolute pleasure.’

Annalize Dedekind, Chair of the Vrystaat Arts Festival says: ‘Significant progress has been made since the start of the Free State Arts &Health programme. Under the leadership of MC Roodt, the arts are being used as a medium to bring a certain message to communities regarding their health, be it physical, psychological or social. A good example is the programme in Platfontein, where the !Xun and Khwe people’s heritage is at a crossroads because of the influence of contemporary culture on the youth. Through this programme, the younger generation has had the opportunity to sit at the elders’ feet and hear stories of their people, which were on the way to never being told again if those elders died. The young ones now get the opportunity to depict those stories in their own art works, which will be exhibited at the Vrystaat Arts Festival and other venues in the country.’

In 2017, Free State Arts & Health will present two projects during the Vrystaat Arts Festival, namely, Ons kom vanaf ons stories (We Come from Our Stories) and Parallel to Pandemic.

Ons kom vanaf ons stories is a print portfolio that visually retells traditional stories from the !Xun and Khwe First Nations peoples. The project was realised through a partnership between Free State Arts & Health, the National Association of Childcare Workers (NACCW) in Kimberley, Isibindi Youth Centre in Platfontein, and the William Humprey Art Gallery (WHAG) in Kimberely. The prints were made by young artists from Platfontein as part of an intergenerational cohesion project that facilitates the transfer of cultural narratives from the older generation to the younger.

In this way the programme is making a huge contribution to the conservation of First Nations languages, culture and heritage and creates a new generation of story tellers and/or artists, which is one of the main aims of the festival.

Parallel to Pandemic, is an artist-led condom distribution and targeted messaging campaign that is co-produced by Free State Arts & Health and the PIAD. The project is a response by Free State Arts & Health to the health agenda of the Free State and a platform for young and emerging visual artists to speak to the health community of the festival.

A triannual Arts & Health Industry Newsletter will be also be distributed to the growing sector, to collate work currently dealing with arts an health and act as a discussion point for issues facing the industry. The first newsletter can be downloaded here: http://bit.ly/FSAHNewsletter

Roodt’s election as Chair of the first Arts & Health Special Interest Group (SIG) at the Public Health Association of South Africa (PHASA) goes to show that he has already made his mark in arts in health and that Free State Arts & Health is now a national leader in this field.

For further inquiries contact: MC Roodt, Free State Arts & Health Manager. Tel: +27 (0)51 404 7947 [email protected]

#Free State Arts & Health#vrystaat kunstefees#vrystaat tsa-botjhaba#vrystaat tsa botjhaba#university of the free state#programme for innovation in artform development#andrew w mellon foundation

0 notes