#Leoš Janáček Czech Composer

Text

Kromatika 2023 2024 Slovenska Filharmonija Ljubljana

Slovenska Filharmonija – gov.si

Last night’s performance by the Slovenia Symphony Orchestra was exceptional. Seeing them live on stage was a fantastic experience! Bulgarian Conductor Rossen Milanov led the orchestra.

Rossen Milanov Conductor – cd-cc.si kromatika

Kromatika 2023 2024

The Kromatika 2023 2024 performance last night was the sixth in a series of nine. Kromatika concerts highlight the…

View On WordPress

#Academy of Music Ljubljana#Brass Quintet SiBrass#Brass Trio RTV Slovenia#Bulgarian Conductor Rossen Milanov#Cankarjev Dom Gallus Hall Ljubljana#Horn Soloist Mihajlo Bulajić#Kromatika 2023 2024#Leoš Janáček Czech Composer#Ljubljana Conservatory#Maribor Glasbena Matica Choir and Orchestra#Marjan Kozina Symphonic Poem Antiquity (Davnina)#Marjan Kozina Symphony in Four Movements#Novo Mesto Slovenia#Orchestral Rhapsody Taras Bulba by Czech Composer Leoš Janáček#Post-War Slovenian Philharmonic#Reinhold Glière Concerto for Horn#RTV Slovenia Symphony Orchestra Ljubljana#Russian Composer Reinhold Glière#Russian Novelist Nikolaj Gogol#Slovenia Composer Marjan Kozina#Slovenia Symphony Orchestra#Slovenian Partisan Army 1941-1945#Slovenska Filharmonija#Taras Bulba and Other Tales#Wind Quintet Quintologia#Zaporozhian Cossack Taras Bulba

0 notes

Note

you mentioned 'czech representation in hunter x hunter', and i'm curious about what you mean? i'm not being facetious btw, i'm just curious which characters are czech-coded. i'm a big Hunter x Hunter fan so i love to learn small details i missed C:

oh dear i'm sorry for how long this post will be! there is not a czech like character as in anyone being czech coded. it's more of some random inspiration from czech (and slavic overall) culture and it's fascinating to see because literally noone gives a fuck about czech republic.

anyway my Big Moravian HXH Theory:

there is (kinda) 4 czech things somewhat in the story and it's:

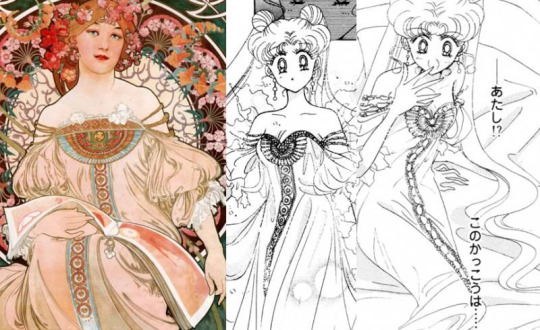

Alfons Mucha as in quite visible inspo for some character designs in the succession war arc (Lynch, Zakuro, Hinrigh, Camilla, Morena)

Leoš Janáček random cameo during Tserri's incelboy talk (a czech person's existence is canon in hxh)

Morena is the moravian/slovakian way of spelling the name of the slavic goddess of winter and death

Kakin most silent revolution that happened 30 years ago is literally velvet revolution (that happened 30 years ago)

Now the theory

Alfons Mucha is fucking beloved in Japan and Naoko Takeuchi literally used him as inpiration meaning Togashi absolutelly knows him

Alfons Mucha had giant exhibition in The National Art Center in Tokyo in year 2017 which consisted of The Slav Epic (gigantic painting of the history of slavs consisting both of mythology and real events). The exhibition happened during the 2017 hiatus which was before Morena was introduced (march 2018)

So my theory is that Togashi went to the exhibition, got very into some pamphlets/books about Mucha and slavic mythology.

Used moravian spelling of Morena because Mucha is moravian.

During that he found out about Leoš Janáček the czech (moravian again) composer who lived during the same time and the same places as Mucha (Mucha almost got a job as a church singer when he was teenager but the place was already taken by...teenager Janáček...bless South Moravia...)

Got into Czechoslovak history and that is how we got Velvet Revolution Kakin republic 1989

So yea this is czech representation as in me reading the Word's Most Popular Manga and seeing things only 20 people worldwide me including might relate to!!!

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Who is Nicky Spence? Everything you need to know about the Scottish tenor, including his best recordings

The winner of the 2022 BBC Music Magazine Personality of the Year award is well-known for his charisma and vocal stature

Who is Nicky Spence?

Nicky Spence is a Scottish operatic tenor known for his vocal and physical stature (right down to his Size 12 feet), his velvety vocal timbre, his open-minded approach to repertoire, and his charisma – qualities that won the 38-year-old singer the 2022 BBC Music Magazine Personality of the Year award.

Where does Nicky Spence come from?

Dumfries, near the Scottish Borders, where he grew up on a farm. He is still a supporter of the town's football team, Queen of the South ('The Doonhamers'), who currently play in Scottish League One.

How old is Nicky Spence?

Nicky Spence was born in 1983.

Is Nicky Spence married?

Nicky Spence is married to his accompanist Dylan Perez.

How did Nicky Spence get into music?

Although Spence originally wanted to play the trumpet - and briefly took it up as a child - his family could not afford to pay for lessons. Luckily a music teacher at his school spotted his talent for singing, which went on to win him the Dumfries and Galloway Young Musician of the Year Award when he was 14, as well as a place in the Scottish Youth Theatre and National Youth Music Theatre.

When did opera enter the picture?

After a neighbour offered the 15-year-old Spence a spare ticket for Mozart's The Magic Flute. He was hooked.

Where did he study?

At the Guildhall School of Music and Drama, where, during his final year, he got his first big break, receiving a five-record contract with Universal Classics. Within the space of just a couple of years, he released his first album (My First Love), was nominated for the 'Young British Classical Performer of the Year' Classical Brit Award, and toured with Katherine Jenkins and Shirley Bassey. He has said that he owes more to Tom Jones than to Pavarotti in finding his voice. Yet, when the time came to record his second album, Spence turned his back on the £1m contract, choosing instead to return to full-time study at the Guildhall to focus on opera.

And since then?

He has sung in opera houses and concert halls all over the world, with regular appearances at the Royal Opera House and English National Opera. Admitting that he has an aversion to the 'rum-ti-tum' operas of Donizetti and the 'sillier' side of Verdi, Spence has specialised in complex, truthful roles, frequently taking on repertoire by the Czech composers Leoš Janáček and Antonín Dvořák. He also has an affinity for Wagner, having appeared in The Mastersingers of Nuremberg, Der fliegende Holländer, Tristan und Isolde and Das Rheingold – and has sung a good deal of 20th century repertoire. But he still casts his net beyond classical music, freely professing his love of musicals and often embracing the sounds of Broadway in his work.

Anything else I should know about Nicky Spence?

Even by A-list singer standards, Spence has a particular talent for keeping busy. Last winter he was one of three mentors appearing on Anyone Can Sing, a TV series in which six would-be singers were given guidance by expert vocalists. During the pandemic he made every minute count, jabbing over 100 people every day as a volunteer in a vaccination clinic.

0 notes

Text

Genius Czech composer Leoš Janáček and his wife Zdenka (born Schulzová), around the time of their marriage. Hipsters way, way before it became mainstream. Brno, Margraviate of Moravia, Cisleithania, Austro-Hungarian Empire, 1881.

#janáček#leoš janáček#zdenka#zdenka schulzová#czech#czech republic#czechia#moravia#brno#composer#music#margraviate#cisleithania#austria-hungary#austro-hungarian empire#b&w#b&w icons#portrait#black and white#portrait photography#photography#style#hipster

29 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Leoš Janáček – Scientist of the Day

Leoš Janáček, a Czech composer, died Aug. 12, 1928, at the age of 74.

read more...

#Leos Janacek#music and science#composer#histsci#histSTM#19th century#history of science#Ashworth#Scientist of the Day

25 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Self-Portrait by Alphonse Mucha, 1899

Alfons Maria Mucha (Czech: 24 July 1860 – 14 July 1939), known internationally as Alphonse Mucha, was a Czech painter, illustrator, and graphic artist, living in Paris during the Art Nouveau period, best known for his distinctly stylized and decorative theatrical posters, particularly those of Sarah Bernhardt. He produced illustrations, advertisements, decorative panels, and designs, which became among the best-known images of the period.

In the second part of his career, at the age of 43, he returned to his homeland of Bohemia-Moravia region in Austria and devoted himself to painting a series of twenty monumental canvases known as The Slav Epic, depicting the history of all the Slavic peoples of the world, which he painted between 1912 and 1926. In 1928, on the 10th anniversary of the independence of Czechoslovakia, he presented the series to the Czech nation. He considered it his most important work. It is now on display in Prague.

Alphonse Mucha was born on 24 July 1860 in the small town of Ivančice in southern Moravia, then a province of the Austrian Empire (currently a region of the Czech Republic). His family had a very modest income; his father Ondřej was a court usher, and his mother Amálie was a miller's daughter. Ondřej had six children, all with names starting with A. Alphonse was his first child with Amálie, followed by Anna and Anděla.

Alphonse showed an early talent for drawing; a local merchant impressed by his work provided him with paper for free, though it was considered a luxury. In the preschool period, he drew exclusively with his left hand. He also had a talent for music: he was an alto singer and violin player

After completing volksschule, he wanted to continue with his studies, but his family was not able to fund them, as they were already funding the studies of his three step-siblings] His music teacher sent him to Pavel Křížkovský, choirmaster of St Thomas's Abbey in Brno, to be admitted to the choir and to have his studies funded by the monastery. Křížovský was impressed by his talent, but he was not able to admit and fund him, as he had just admitted another talented young musician, Leoš Janáček.

Křížovský sent him to a choirmaster of the Cathedral of St. Peter and Paul, who admitted him as a chorister and funded his studies at the gymnasium in Brno, where he received his secondary school education. After his voice broke, he gave up his chorister position, but played as a violinist during masses.

He became devoutly religious, and wrote later, "For me, the notions of painting, going to church, and music are so closely knit that often I cannot decide whether I like church for its music, or music for its place in the mystery which it accompanies." He grew up in an environment of intense Czech nationalism in all the arts, from music to literature and painting. He designed flyers and posters for patriotic rallies.

His singing abilities allowed him to continue his musical education at the Gymnázium Brno in the Moravian capital of Brno, but his true ambition was to become an artist. He found some employment designing theatrical scenery and other decorations. In 1878 he applied without success to the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague, but was rejected and advised to "find a different career". In 1880, at the age of 19, he traveled to Vienna, the political and cultural capital of the Empire, and found employment as an apprentice scenery painter for a company which made sets for Vienna theaters. While in Vienna, he discovered the museums, churches, palaces and especially theaters, for which he received free tickets from his employer. He also discovered Hans Makart, a very prominent academic painter, who created murals for many of the palaces and government buildings in Vienna, and was a master of portraits and historical paintings in grand format. His style turned Mucha in that artistic direction and influenced his later work. He also began experimenting with photography, which became an important tool in his later work.

To his misfortune, a terrible fire in 1881 destroyed the Ringtheater, the major client of his firm. Later in 1881, almost without funds, he took a train as far north as his money would take him. He arrived in Mikulov in southern Moravia, and began making portraits, decorative art and lettering for tombstones. His work was appreciated, and he was commissioned by Count Eduard Khuen Belasi, a local landlord and nobleman, to paint a series of murals for his residence at Emmahof Castle, and then at his ancestral home in the Tyrol, Gandegg Castle. The paintings at Emmahof were destroyed by fire in 1948, but his early versions in small format exist (now on display at the museum in Brno). He showed his skill at mythological themes, the female form, and lush vegetal decoration. Belasi, who was also an amateur painter, took Mucha on expeditions to see art in Venice, Florence and Milan, and introduced him to many artists, including the famous Bavarian romantic painter, Wilhelm Kray, who lived in Munich.

Count Belasi decided to bring Mucha to Munich for formal training, and paid his tuition fees and living expenses at the Munich Academy of Fine Arts. He moved there in September 1885. It is not clear how Mucha actually studied at the Munich Academy; there is no record of his being enrolled as a student there. However, he did become friends with a number of notable Slavic artists there, including the Czechs Karel Vítězslav Mašek and Ludek Marold and the Russian Leonid Pasternak, father of the famous poet and novelist Boris Pasternak. He founded a Czech students' club, and contributed political illustrations to nationalist publications in Prague. In 1886 he received a notable commission for a painting of the Czech patron saints Cyril and Methodius, from a group of Czech emigrants, including some of his relatives, who had founded a Roman Catholic church in the town of Pisek, North Dakota. He was very happy with the artistic environment of Munich: he wrote to friends, "Here I am in my new element, painting. I cross all sorts of currents, but without effort, and even with joy. Here, for the first time, I can find the objectives to reach which used to seem inaccessible." However, he found he could not remain forever in Munich; the Bavarian authorities imposed increasing restrictions upon foreign students and residents. Count Belasi suggested that he travel either to Rome or to Paris. With Belasi's financial support, he decided in 1887 to move to Paris.

Mucha moved to Paris in 1888 where he enrolled in the Académie Julian[18] and the following year, 1889, Académie Colarossi. The two schools taught a wide variety of different styles. His first professors at the Academie Julien were Jules Lefebvre who specialized in female nudes and allegorical paintings, and Jean-Paul Laurens, whose specialties were historical and religious paintings in a realistic and dramatic style. At the end of 1889, as he approached the age of thirty, his patron, Count Belasi, decided that Mucha had received enough education and ended his subsidies.

When he arrived in Paris, Mucha found shelter with the help of the large Slavic community. He lived in a boarding house called the Crémerie at 13 rue de la Grande Chaumière, whose owner, Charlotte Caron, was famous for sheltering struggling artists; when needed she accepted paintings or drawings in place of rent. Mucha decided to follow the path of another Czech painter he knew from Munich, Ludek Marold, who had made a successful career as an illustrator for magazines. In 1890 and 1891, he began providing illustrations for the weekly magazine La Vie populaire, which published novels in weekly segments. His illustration for a novel by Guy de Maupassant, called The Useless Beauty, was on the cover of 22 May 1890 edition. He also made illustrations for Le Petit Français Illustré, which published stories for young people in both magazine and book form. For this magazine he provided dramatic scenes of battles and other historic events, including a cover illustration of a scene from the Franco-Prussian War which was on 23 January 1892 edition.

His illustrations began to give him a regular income. He was able to buy a harmonium to continue his musical interests, and his first camera, which used glass-plate negatives. He took pictures of himself and his friends, and also regularly used it to compose his drawings. He became friends with Paul Gauguin, and shared a studio with him for a time when Gauguin returned from Tahiti in the summer of 1893. In late autumn 1894 he also became friends with the playwright August Strindberg, with whom he had a common interest in philosophy and mysticism.

His magazine illustrations led to book illustration; he was commissioned to provide illustrations for Scenes and Episodes of German History by historian Charles Seignobos. Four of his illustrations, including one depicting the death of Frederic Barbarossa, were chosen for display at the 1894 Paris Salon of Artists. He received a medal of honor, his first official recognition.

Mucha added another important client in the early 1890s; the Central Library of Fine Arts, which specialized in the publication of books about art, architecture and the decorative arts. It later launched a new magazine in 1897 called Art et Decoration, which played an early and important role in publicizing the Art Nouveau style. He continued to publish illustrations for his other clients, including illustrating a children's book of poetry by Eugène Manuel, and illustrations for a magazine of the theater arts, called La Costume au théâtre.

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

Leoš Janáček baptised Leo Eugen Janáček; (3 July 1854 – 12 August 1928) was a Czech composer, musical theorist, folklorist, publicist and teacher. He was inspired by Moravian and other Slavic folk music to create an original, modern musical style.

Until 1895 he devoted himself mainly to folkloristic research. While his early musical output was influenced by contemporaries such as Antonín Dvořák, his later, mature works incorporate his earlier studies of national folk music in a modern, highly original synthesis, first evident in the opera Jenůfa, which was premiered in 1904 in Brno. The success of Jenůfa (often called the "Moravian national opera") at Prague in 1916 gave Janáček access to the world's great opera stages. Janáček's later works are his most celebrated. They include operas such as Káťa Kabanová and The Cunning Little Vixen, the Sinfonietta, the Glagolitic Mass, the rhapsody Taras Bulba, two string quartets, and other chamber works. Along with Dvořák and Bedřich Smetana, he is considered one of the most important Czech composers.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

In many great dramatic texts, talk pins us to specifics. Tics of speech sprout up, as if organically, from the political contingencies and the geographical facts that give rise to character. A wonderful feature of the theatre is that, from one production of a work to the next, those verbal bursts can attach to new applications, sending their signals off to meet new satellites of place and time. The word “revival” becomes literal: let’s make this thing live again, but differently.

Yet in the latest revival of Harold Pinter’s Betrayal, written in 1978 and now on Broadway at the Bernard B. Jacobs Theatre, the director, Jamie Lloyd, declines this opportunity, to disorienting effect. Instead of setting Pinter’s love-triangle-told-backward amid freshly suggestive surroundings, Lloyd strips the production bare, leaving the play to speak in a near-vacuum, a head without a body.

Emma (Zawe Ashton) and Jerry (Charlie Cox) have carried on an affair for seven years; Robert (Tom Hiddleston), Emma’s husband and Jerry’s good friend, hasn’t been as much in the dark as Jerry thinks. The play unshrouds itself in bars and restaurants, at Emma and Robert’s house, and at the “home” to which Jerry and Emma retreat on furtive afternoons. Lloyd shrugs these locations loose, and instead places a marbled white wall behind his players and gives them the barest props. The actors move around a few wooden chairs. A folding table set lovingly in the secret apartment becomes, in the next scene, a two-top for a boozily charged, cryptically combative lunch between Jerry and Robert. The whole thing might be happening in a back hallway of a museum.

Indeed, the characters here seem a bit like objects on display. On such a naked stage, their heads cast uncanny shadows against that bare wall—the wall sometimes moves; stage depth and lighting are the only real sources of visual variance—and the shadows, often motionless when the actors are stuck in one of Pinter’s pauses, look like statuary monuments to impermanent emotional states.

Early in the play, Jerry, having a go at Emma for her conversational rustiness after a two-year absence, says, “You remember the form. I ask about your husband, you ask about my wife.” That line becomes a synecdoche for Lloyd’s entire undertaking: Betrayal itself becomes a kind of form; the implication of its placelessness is that its tangle of iffy loves and fading affections is an ever-unfolding human pattern, occurring not only in England in the nineteen-seventies, where Pinter placed it, but everywhere and all the time. Unanchored from the world that helped birth it, the play becomes a parable. Pinter’s time-bound references—to skillful letter writers and long holidays spent without thought to telephonic communication—chafe.

Another effect of this contextual antigravity is a new focus on the characters less as people than as types. Jerry is a literary agent; Robert is a publisher; Emma runs an art gallery—everybody’s close to art but not quite making it. Running referentially through the play is a writer named Casey, represented by Jerry and published by Robert, and, eventually, “seeing a bit of” Emma, who’s finally crawling away from the wreck of her marriage and marriage-like affair. I’d never before found the recurrent utterances of Casey’s name so funny, or so trenchant concerning Jerry and Robert’s shared parasitism—Robert calls Jerry “quite talented at uncovering talent.” These men, “friends” who maintain contact through professional orbits but never seem to achieve lasting intimacy, have taken their attitudes toward the likes of Casey and, unwittingly, applied them to Emma: she’s just another diamond in the rough, a recruitable talent.

Lloyd has directed Pinter before, so he’s familiar with the playwright’s uniquely jolting rhythms and the ironic, half-articulate music of his conversations. Those pauses bloom with interpersonal meaning and a kind of dread. Zawe Ashton is particularly deft at using the silences as ramps into and out of sonorous line deliveries. At one point, in the middle of an excruciating conversation, just before a deadly pause, she sighs two words—“I see”—turning them into a sad song’s final cadence. If Lloyd’s staging creates a kind of desert, the pauses are his crocuses—pale, fragile, miraculous.

More simply, the pauses act as phrase markers between graceful volleys of British-accented English speech. Michael Goldstein, one of Pinter’s childhood best friends and a lifelong intellectual interlocutor, put Pinter onto the composer Leoš Janáček, whose string quartet “Intimate Letters” tries to mimic spoken Czech. Michael Billington, in his biography of Pinter, suggests that this exchange, which eventually led the friends to a discussion of Beethoven’s use of silence, might have been one of several sources of Pinter’s own pauses. (Another feature of the show has a symphonic touch: at center stage there’s a rotating circle, with another moving ring around it. Between scenes, the characters spin through time, choreographing their adjustments of the furniture like Jamiroquai on his treadmill, sometimes moving in parallel and sometimes in wistful counterpoint.) I can’t tell if Lloyd’s interpretative minimalism makes Betrayal more or less culturally British, but Pinter’s words and tones—his native, brutal idiom—do shine through. Lloyd’s enjoyable, astringent experiment feels transitional, and plows new ground for interpreter-directors of Pinter to come.

#Tom Hiddleston#Zawe Ashton#Charlie Cox#Betrayal Broadway#The new yorker review#bernard b jacobs theater#jamie lloyd production#harold pinter play#Broadway debut#Theatre tom#tom hiddleston stage performance#tom as robert#zawe as emma#charlie as jerry#hiddles 2019#September 16 issue#new york city

49 notes

·

View notes

Link

In many great dramatic texts, talk pins us to specifics. Tics of speech sprout up, as if organically, from the political contingencies and the geographical facts that give rise to character. A wonderful feature of the theatre is that, from one production of a work to the next, those verbal bursts can attach to new applications, sending their signals off to meet new satellites of place and time. The word “revival” becomes literal: let’s make this thing live again, but differently.

Yet in the latest revival of Harold Pinter’s “Betrayal,” written in 1978 and now on Broadway at the Bernard B. Jacobs Theatre, the director, Jamie Lloyd, declines this opportunity, to disorienting effect. Instead of setting Pinter’s love-triangle-told-backward amid freshly suggestive surroundings, Lloyd strips the production bare, leaving the play to speak in a near-vacuum, a head without a body.

Emma (Zawe Ashton) and Jerry (Charlie Cox) have carried on an affair for seven years; Robert (Tom Hiddleston), Emma’s husband and Jerry’s good friend, hasn’t been as much in the dark as Jerry thinks. The play unshrouds itself in bars and restaurants, at Emma and Robert’s house, and at the “home” to which Jerry and Emma retreat on furtive afternoons. Lloyd shrugs these locations loose, and instead places a marbled white wall behind his players and gives them the barest props. The actors move around a few wooden chairs. A folding table set lovingly in the secret apartment becomes, in the next scene, a two-top for a boozily charged, cryptically combative lunch between Jerry and Robert. The whole thing might be happening in a back hallway of a museum.

Indeed, the characters here seem a bit like objects on display. On such a naked stage, their heads cast uncanny shadows against that bare wall—the wall sometimes moves; stage depth and lighting are the only real sources of visual variance—and the shadows, often motionless when the actors are stuck in one of Pinter’s pauses, look like statuary monuments to impermanent emotional states.

Early in the play, Jerry, having a go at Emma for her conversational rustiness after a two-year absence, says, “You remember the form. I ask about your husband, you ask about my wife.” That line becomes a synecdoche for Lloyd’s entire undertaking: “Betrayal” itself becomes a kind of form; the implication of its placelessness is that its tangle of iffy loves and fading affections is an ever-unfolding human pattern, occurring not only in England in the nineteen-seventies, where Pinter placed it, but everywhere and all the time. Unanchored from the world that helped birth it, the play becomes a parable. Pinter’s time-bound references—to skillful letter writers and long holidays spent without thought to telephonic communication—chafe.

Another effect of this contextual antigravity is a new focus on the characters less as people than as types. Jerry is a literary agent; Robert is a publisher; Emma runs an art gallery—everybody’s close to art but not quite making it. Running referentially through the play is a writer named Casey, represented by Jerry and published by Robert, and, eventually, “seeing a bit of” Emma, who’s finally crawling away from the wreck of her marriage and marriage-like affair. I’d never before found the recurrent utterances of Casey’s name so funny, or so trenchant concerning Jerry and Robert’s shared parasitism—Robert calls Jerry “quite talented at uncovering talent.” These men, “friends” who maintain contact through professional orbits but never seem to achieve lasting intimacy, have taken their attitudes toward the likes of Casey and, unwittingly, applied them to Emma: she’s just another diamond in the rough, a recruitable talent.

Lloyd has directed Pinter before, so he’s familiar with the playwright’s uniquely jolting rhythms and the ironic, half-articulate music of his conversations. Those pauses bloom with interpersonal meaning and a kind of dread. Zawe Ashton is particularly deft at using the silences as ramps into and out of sonorous line deliveries. At one point, in the middle of an excruciating conversation, just before a deadly pause, she sighs two words—“I see”—turning them into a sad song’s final cadence. If Lloyd’s staging creates a kind of desert, the pauses are his crocuses—pale, fragile, miraculous.

More simply, the pauses act as phrase markers between graceful volleys of British-accented English speech. Michael Goldstein, one of Pinter’s childhood best friends and a lifelong intellectual interlocutor, put Pinter onto the composer Leoš Janáček, whose string quartet “Intimate Letters” tries to mimic spoken Czech. Michael Billington, in his biography of Pinter, suggests that this exchange, which eventually led the friends to a discussion of Beethoven’s use of silence, might have been one of several sources of Pinter’s own pauses. (Another feature of the show has a symphonic touch: at center stage there’s a rotating circle, with another moving ring around it. Between scenes, the characters spin through time, choreographing their adjustments of the furniture like Jamiroquai on his treadmill, sometimes moving in parallel and sometimes in wistful counterpoint.) I can’t tell if Lloyd’s interpretative minimalism makes “Betrayal” more or less culturally British, but Pinter’s words and tones—his native, brutal idiom—do shine through. Lloyd’s enjoyable, astringent experiment feels transitional, and plows new ground for interpreter-directors of Pinter to come.

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Re: Rhett’s IG story

His “tasting” music is one of my all-time favorite pieces. It’s by a somewhat obscure Czech composer named Leoš Janáček. His music is SO lush and beautiful. I saw an opera of his be performed last year and I could only concentrate on the pit orchestra (kept having to remind myself to watch the stage 😜).

Anyways. It was the first movement of his Sinfonietta. I highly recommend a listen.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Conversation with Tasmin Waley-Cohen

Described by the Guardian as a performer of "fearless intensity", the recipient of 2016-2017 ECHO Rising Stars Awards Tamsin Waley-Cohen joined by pianist Huw Watkins released a new CD exploring folk-inspired Bohemia from before the First World War. It features works by Antonin Dvořák, Josef Suk and Leoš Janáček. Primephonic’s Rina Sitorus had a chance to talk to Tamsin about it.

Congratulations on your newest recording, Bohemia. What is the idea behind it?

Thank you very much. I’ve always really loved the music of Antonin Dvořák, and Leoš Janáček. In fact some of my earliest memories of playing chamber music was playing Dvořák quartet. The idea actually sits at the beginning of a series of albums I’ve done over the past few years, which between them, tell the story of the twentieth century. I wanted to do something which comes before the 1917 album. Although the Janáček is the latest work on this album, written right before the outbreak of the first World War, I wanted to do an album which in a way encapsulated the incredibly cultured world of central Europe, which was completely lost after the first World War.

How would you describe your collaboration with Huw Watkins?

Huw and I have been working together for many years. I premiered his Concertino when I was 15. He is my long time partner in violin and piano recitals and chamber music. We’ve recorded quite a lot together so it was only natural that we recorded Bohemia together. Actually it was his idea to include the Suk pieces. They fit perfectly. The works are very beautiful but quite strange and unexpected. There’s something about them which is a bit uncomfortable. They fit very well with the idea of a world that is disappearing.

What are the highlights of Bohemia that people may not yet be so familiar with?

Well, I think in fact the Dvořák sonata is almost never played, it is quite early, from before he had achieved his great fame. It has this almost fresh naivety about it and I think it's very charming. Many people may not know that. And the works from Suk are a gems which are not played at all these days, but they were very popular 50 years ago. Another highlight could be the four romantic pieces by Dvořák which he wrote later on when he went back to his country house in Bohemia. He was writing these melodies inspired by the music of the countryside.

Are you happy with how the recording turned out?

As a musician you’re always learning and improving. It doesn’t mean that something I did last year was not good, but I might do it differently.The thing with recordings is that they are snapshots of a few days. You put your heart and soul in these few days, you do your best in a recording. Of course later there will be things which I want to change or do differently, but I do feel that this is a very good representation of the works. I absolutely stand by what we did. And since recordings will be there forever, I’ll always make sure that I know from every note what I want and why I want it that way. And it comes from a lot of thoughts, analysis and reflections, so nothing is happening by chance.

I’m also very happy to work with producer Nick Parker and engineer Mike Hatch. They understood what we wanted, something tactile and intimate to go for the warmness of Janáček for example and tenderness for other moments.

How do you prepare a recording?

It is very very important to have a very good preparation. A lot of practise and rehearsals. For me it is just as important to perform the pieces on stage and sort of living that experience. I think you should perform it at least five times, but ideally more. And remember to record yourself before you go into the recording, so you are producing what you’re hoping for in your mind’s ears.

Do you still get nervous?

Yes of course. It is a different nervous feeling between recording and stage performance. You are recording for three days, but every take is different. It's more about this adrenaline that goes through you in these whole three days. Stage performance is about adrenaline rush for a shorter time. For me it’s a positive thing. It should lift up the performance and bring extra energy to the stage. I don't see nerves as a negative thing. Of course you need to know how to relate to it and manage it.

Could you tell me about your next projects?

My next recording plans are actually with my quartet, Albion. We have recorded four sets of Dvořák quartets. There are 14 of them and we are doing a sort of exploration of the cycles. I really love the music – it’s the kind of music which gives you joy and energy.

I’m also working on the complete violin and keyboard works by CPE Bach on modern instruments with James Baillieu. This is quite a big project. Apart from the many different pieces, it is also about entering into another world that is very different from any other composer. It's a wild and emotional style of writing. You can really see it on people like Schumann. The works are very very expressive, very virtuosic and very exciting to play. I played it in concert recently. The recording will be released as a double disc in 2019.

Also, I just recorded with the Czech Philharmonic a new concerto from an English composer Richard Blackford which they commisioned for me. The whole concerto tells about the Greek myth of Niobe. The violin plays the part of Niobe and it's very theatrical as the whole concerto is very dramatic. She basically showed off that she had 14 children, then she was punished and turned into a rock. We discussed a lot about Niobe and its relevance today, as she was punished for her boastfulness about her children. I think women all over the world still experience this unfair punishment for stepping outside of restricted boundaries. I think it’s very much a modern story that we can learn a lot from. The album will be out in summer 2018.

What about the Albion quartet, what is the story behind it?

It was officially just formed 18 months ago. The quartet consists of me, Emma Parker (violin), Rosalind Ventris (viola), and Nathaniel Boyd (cello). You know, for a string player, playing in a quartet is like the holy grail. I’ve always loved the idea but it is very difficult to find four people who really share the same vision because it is such an intimate platform. You have to have shared ideals of music and much respect for each other. Actually we have known each other for years. We met in the chamber music scene and we would just do projects. At some point, we said to each other: let’s do this seriously.

Quartet playing demands much more compared to a solo work. It needs so much refinement, nuance in interpretation, togetherness in a group, not only in how you change your sound, but also in the articulation and intonation as well. Quartet has always been a big love of mine, I’m happy that now I’m playing in one. We will be playing at Concertgebouw Amsterdam in April 2018.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Leoš Janáček (1854–1928) Czech composer, musical theorist, folklorist, publ… https://ift.tt/2J2uE9N

0 notes

Text

July 03 in Music History

1550 Birth of composer Jakob Handl.

1814 Birth of composer Janis Cimze.

1816 FP of Carafa's "Gabriella di Vergy" Naples.

1819 Birth of composer Louis Theodore Gouvy.

1836 Death of English soprano Cecilia Davies.

1842 Death of Italian soprano Matilde Palazzesi.

1846 Birth of Russian composer Achilles Alferaky in Ukraine.

1848 Birth of American music publisher Theodore Presser of Philadelphia. Also published The Etude magazine.

1850 Birth of composer Alfredo Kiel.

1852 Birth of Hungarian-American pianist Rafael Joseffy.

1854 Birth of Czech composer and conductor Leoš Janáček in Hukvaldy.

1860 Birth of Scottish composer William Wallace.

1860 Birth of bass Wilhelm Hesch in Labsky Tynec.

1861 Birth of German tenor Oskar Feuge in Reudnita.

1862 Birth of composer Friedrich Ernst Koch.

1871 Birth of Basque composer Vicente Arregui Garay.

1873 Death of Italian tenor Josef Poniatowski.

1874 Death of German pianist and composer Franz Bendel in Berlin.

1879 Birth of French composer Philippe Gaubert.

1880 Birth of composer Carl Schuricht.

1881 Death of Italian baritone Achille De Bassini.

1885 Birth of Swedish baritone Carl Richter in Stockholm.

1890 Birth of Austrian bass Jossef Manowarda.

1892 Birth of composer Wilhelm Rettich.

1894 Birth of Italian soprano Bianca Scacciati in Faenza.

1895 Birth of Russian bass Mark Reizen in Moscow.

1895 Birth of composer Oles' Semyonovich Chishko

1899 Birth of composer Klimenty Arkad'yevich Korchmaryov.

1899 Birth of composer Otto Reinhold.

1901 Birth of American composer Ruth Crawford Seeger.

1907 Birth of German composer Romeo Maximilian Eugene Ludwig Gutsche.

1907 Birth of Italian soprano Cesarini Valobra.

1912 Birth of German soprano Elinor Junker-Giesen in Berlin.

1920 Birth of American composer John Lessard.

1922 Birth of Scottish bass David Ward in Dumbarton, Scotland.

1923 Birth of American composer Jean Eichelberger Ivey.

1926 Birth of American composer Meyer Kupperman.

1930 Birth of German conductor Carlos Kleiber in Berlin.

1932 Birth of Italian tenor Tito del Bianco.

1933 Birth of Chilean mezzo-soprano Laura Didier in Santiago Chile.

1937 Birth of American filmscore composer David Shire.

1939 Birth of German mezzo-soprano Brigitte Fassbaender in Berlin.

1940 Birth of Irish mezzo-soprano Bernadette Tattan Greevy in Dublin.

1942 Birth of American baritone Thomas Jamerson in New Orleans.

1944 FP of Robert Wright & George Forest's musical The Song of Norway, with music of Norwegian composer Edward Grieg, in San Francisco.

1948 Birth of composer Peter Ruzicka.

1959 Birth of American composer Lawrence Dillon.

1957 Birth of German soprano Gabriele Maria Rounge in Hanover.

1960 Birth of soprano Susanna Anselmi.

1961 Death of soprano Edith De Lys.

1964 FP of Robert Ward's opera, The Lady from Colorado in Center City, CO.

1966 Death of American composer Joseph Deems Taylor, at age 80, in NYC.

1967 FP of Havergal Brian's Symphony No. 4 Das Siegeslied [1929], in London.

1976 FP of Alan Hovhaness' Violin Concerto Ode to Freedom Yehudi Menuhin and André Kostelanetz conducting, at Wolf Trap in Vienna, VA.

1979 Death of French composer Louis Durey in St. Tropez, France.

1981 Death of tenor John Brooks McCormack.

1998 Death of English romantic composer George Lloyd in London.

2004 FP of Dr. Phillip Smith's War Between the States - Music of the American Civil War and Les Marsden's 'American' Symphony on New and Old Tunes at Yosemite National Park.

2000 Death of American baritone Walter Cassel.

2006 Death of American mezzo-soprano Lorraine Hunt Lieberson.

9 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

April 22, 2019 | Tom Huizenga -- If just one thing can be confirmed from these compelling Tiny Desk performances by the Calidore String Quartet, it should be that the centuries-old formula – two violins, a viola and a cello – is still very much alive and evolving. Indeed, an impromptu show of hands in the audience before the concert began revealed that almost everyone had seen a string quartet perform live. The genre was born some 250 years ago and pioneered by Joseph Haydn, but composers today are still tinkering with its possibilities. Consider Caroline Shaw. The young, Pulitzer-winning composer wrote the opening work in this set, First Essay: Nimrod, especially for the Calidore String Quartet. Over a span of eight minutes, the supple theme that opens this extraordinary work takes a circuitous adventure. It unfolds into a song for the cello, is sliced into melodic shards, gets bathed in soft light, becomes gritty and aggressive and disguises itself in accents of the old master composers. Midway through, the piece erupts in spasms that slowly dissolve back into the theme. The Calidore players also chose music by the quirky Czech composer, Leoš Janáček who, in 1913, set one of his operas on the moon. He wrote only two string quartets but they are dazzling. The opening Adagio, from his first quartet, is typical Janáček, with hairpin turns that veer from passionate romance to prickly anxiety. Reaching back farther, the ensemble closes the set with an early quartet by Beethoven, who took what Haydn threw down and ran with it. The final movement from Beethoven's Fourth Quartet both looks back at Haydn's elegance and implies the rambunctious, even violent, risks his music would soon take. The performance turns out to be a fascinating through-line, traced from Beethoven's early incarnation of the string quartet, straight through to Caroline Shaw's new sounds, which occasionally glance backward. SET LIST Caroline Shaw: "First Essay: Nimrod" Janáček: "String Quartet No. 1, 'Adagio'" Beethoven: "String Quartet Op. 18, No. 4, Allegro - Prestissimo" MUSICIANS Jeffrey Myers, violin; Ryan Meehan, violin; Jeremy Berry, viola; Estelle Choi, cello CREDITS Producers: Tom Huizenga, Morgan Noelle Smith; Creative Director: Bob Boilen; Audio Engineer: Josh Rogosin; Videographers: Morgan Noelle Smith, CJ Riculan; Production Assistant: Adelaide Sandstrom; Photo: Amr Alfiky/NPR

0 notes

Note

since you mention opera, aka a cool thing, what is your: favourite opera? favourite opera you've seen? opera you want to see? :)

yaaaaaay i didn’t expect people actually would ask me anything about opera, thaaaanks this is so cool!

well the last opera I saw that really blew me away was Jenůfa by Leoš Janáček (who is a super cool Czech composer of the late 19th / early 20th century and you should definitely check him out if you’re into that kind of thing). It’s pretty dark, about a woman called Jenůfa who gets pregnant while unmarried, and in fear of being shunned by society she has to hide it. eventually her mother kills the baby so Jenůfa gets a second chance at having a good life. There’s this great aria the mother sings when she makes the decision to kill the baby, it’s called “Co chvíla...co chvíla”, and that’s one of the most soul crushing pieces of music i’ve ever heard. I saw this opera in a production at the State Opera in Munich and it was mindblowing, especially because Karita Mattila was playing the Kostelnička, the mother of Jenůfa. like... wow.

“favorite” opera in general is usually very hard to pick, because there are so many amazing ones, all different and great in their own way. but usually i reply to that question with “Orpheus ed Euridice” by Gluck, because that was the first opera I really knew, and I’m honestly so in love with the music. I’m also always here for alto women in drag (that’s honestly one of my favorite things about opera, not gonna lie). I’m also always blown away by Mozart’s “Don Giovanni” - that is music on a deep, dark, existential level I tell you. The ouverture alone daaaaammmnn.

Also, currently I have become very fond of “The Consul”, which is an opera from 1950 and by the way an excellent one to start with for anyone who wants to get into opera. It’s not at all popular or anything, but the music is great, a mixture of italian belcanto and film scores (and some more things), and the story is great: about the inhumanity of bureaucracy and a woman who fails to get a visa. sounds lame, but trust me, it’s super good and also pretty relevant, looking at stuff like the refugee situation in Europe and the Muslim Ban and stuff like that. (if you wanna give it a try, “To this we come” is the biggest and most important aria from it and I love it. the singing style in the link is a bit oldschool, but I love the voice.)

a few operas that I’d really love to see on stage are Mozart’s “Le nozze di Figaro”, Händel’s “Alcina”, Zimmermann’s “Die Soldaten”, pretty much everything Janáček has ever done, and also, there’s an actual “Brokeback Mountain” opera that came out just a few years after the movie and I’d be really interested to see that.

okay that was enough rambling about opera for now, I hope you enjoyed it :D

4 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

"In the Mists" is a piano cycle by Czech composer Leoš Janáček. It was composed in 1912, some years after Janáček had suffered the death of his daughter Olga and while his operas were still being rejected by the Prague opera houses; all four movements are anchored in "misty" keys with five or six flats; characteristic of the cycle are the frequent changes of meter. Czech musicologist Jiří Zahrádka compared the atmosphere of the cycle to the impressionist compositions, in particular those of Claude Debussy. The première took place on December 7, 1913, when Marie Dvořáková played it at a concert organized by the choral society Moravan in Kroměříž.

The cycle is divided into four movements:

I. AndanteII. Molto adagioIII. AndantinoIV. PrestoPicture: "Snow at Argenteuil" by Claude Monet.Pianist: Paul Crossley.

0 notes