#Māori Knowledge Systems

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

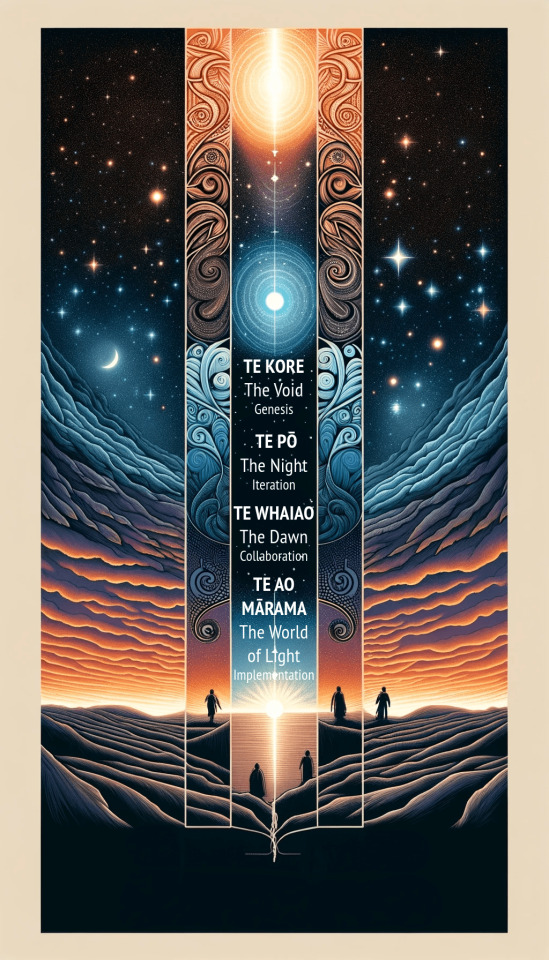

Te Ara Whakamārama: 4 Powerful Steps to Transformative Te Ao Māori-Inspired Development

Explore the transformative "Te Ara Whakamārama," a framework with four stages inspired by Māori wisdom. Embrace a journey of innovation from the conceptual void to the luminous world of realization and beyond. Dive into the essence of Te Ao Māori and unlo

Te Ara Whakamārama or The Pathway to Enlightenment By Conny Huaki and Graeme Smith The journey of creation, from the first seed of an idea to its full expression, is a sacred and transformative process. “Te Ara Whakamārama,” or “The Pathway to Enlightenment,” is a design and development framework that mirrors the natural progression from dusk till dawn, a symbolic representation of the journey…

View On WordPress

#Conceptual Design#Conny Huaki#Creative Journey#Cultural Design#Cultural Framework#Design Framework#educational innovation#Graeme Smith#holistic development#innovation#Māori Development#Māori Knowledge Systems#Māori Wisdom#New Zealand Indigenous#Realisation Process#te ao Māori#Te Ara Whakamārama

0 notes

Text

recently my dad, who dabbles in writing, happened to see something David Seymour said about privilege, and wrote an article about it in one furious sitting. That post is now gathering a fair amount of momentum on social media such as facebook and instagram. So fuck it, why not share it here:

"David Seymour said on twitter

"If you believe you have special rights because of your ethnicity, you’re going to be disappointed with the Treaty Principles Bill. When you’re used to special rights, equality feels like oppression."

A question I have for those who state that Māori get special privileges in Aotearoa New Zealand, Actually two questions.

1/What are they

2/what decade did they start in this country

Did they start in 1863 when the New Zealand government of the day started the Land Settlement Act? An act that confiscated millions of acres of land from the Māori because the Māori refused to sell, leading to the Māori land wars. An act that by the early 1900s meant that Maori held just 8% of the land they had held when they signed Te Tiriti O Waitangi and that percentage continued to fall. As of 2024 land currently owned by Maori is 5% and that's After Waitangi Tribunal Settlements.

The last bit of land was confiscated during WW2 to make an airfield.

Was this one of their special privileges that settlers to New Zealand didn't get?

Did they start in 1867 when the government signed the Native Schools Act, which decreed that all Native Schools would only be held in English? An act that is often blamed on a petition from tribal chiefs calling for a school for their Moku. Yes they did send such a petition but it asked for 2 things, that they be taught literacy, science, and numeracy and the second was that they be taught both in English and Māori. This act wasn't repealed till 1987 by which time several generations of children had had their language and culture beaten out of them. One of these was my Father, speaking Te Reo still makes his hands hurt and he's 80.

This must have been one of those special privileges that only Māori got as this privilege wasn't offered to Dutch or French or other European children who might have spoken another language at school

Was it being Blackbirded? For those that don't know it was the practice of kidnapping Māori and Pacifica and selling them as slaves in Queensland to work the sugar cane plantations.

Thats a privilege that will make you feel special

Was it in the 1850s when the Crown started confiscating Māori children and giving them to Pakeha families to greater assimilate them into the British way of life, An act that continued until well into the 1980s under the foster system leaving them subjected to mental, physical, and sexual abuse

Its a special privilege for special children

Was it a special privilege that John Ballance transported poisoned sugar and flour up the Wanganui River to sell to Māori an act that got overlooked when he became prime minister of this country

Someone was privileged anyway

Or was it in 1907 when the Government signed the Tohunga Suppression Act which banned Māori from access to their healers and medicines and made them rely on Western medicine instead? Did this get rid of a number of quacks, yes but it also suppressed a lot of local knowledge about medicine from local plants that had worked and it put them into the hands of the Western medical system that didn't have their best interests at heart either. It was also aimed at suppressing Māori religion and culture, after all, you suppress the belief system you suppress the people

The only laws aimed at suppressing a religion passed in this country were made against Māori so that must be one of their special privileges, but they did get to pick what religion they could be forced into, Protestant or Catholic so there's that

Is one of the special Privileges a shorter life span, on average 7 years shorter than Pakeha. Yes, the average life span for Māori in the 1700s was 30 but that was the same for Europeans. Is it because they have the privilege of having their symptoms overlooked in a medical system that has prioritised pakeha males, Is it that Pakeha women are more likely to be offered pain relief during childbirth than Māori women? Is it because they were often paid less than their pakeha counterparts at 81 cents to the dollar and so couldn't afford regular checkups? Is it because they were taught not to put themselves forward and to be noticed by society, to be a good Māori?

Is it a privilege that the New Zealand health system can no longer take their race into account when giving them treatment?

Better-researched people have written more on this special Privilege so I will move on

Was it in 1926 when old age and widow pensions came into this country and Māori were only paid 75 per cent of the going pension rate. In 1937 when pressed on why the Senior Treasury official Bernard Ashwin stated "On the face of it, it may appear equitable to pay the average Māori old-age pensioner the same amount per week as the average European pensioner, but in this matter questions of equity should be decided having regard to the circumstances, the needs and the outlook on life of the individuals concerned … the living standard of the Māori is lower – and after all, the object of these pensions is to maintain standards rather than to raise them.’" Or more simply a grass skirt is cheaper than a suit.

I guess being able to make do with less is a special privilege

Was it during the early to mid-20th century when signs saying No Māori's on pubs, hotels, theatres, and even drinking fountains were not uncommon and cinemas and pools had separate use days? In many places, Māori were only allowed to use the pools on Friday as they were cleaned on Saturday. It must have been that Privilege of trying to rent a property and seeing advertisement after advertisement saying Europeans only. Was it that privilege of being denied bank loans because they were Māori?

Being treated as lesser in your own country must be a privilege

Is it the privilege that Māori are jailed at 3 times the rate of Pakeha for the same crimes that will get a paler-skinned person a non-custodial sentence or no charges at all? They do get a special privilege that their race is taken into account when arrested, or charged or sentenced but that comes with the privilege of their race working against them every step of the way. During the mid-20th century often young Māori men were seen socialising together and harassed by police until they committed an antisocial crime like swearing in public and were sent to borstal

Is it a privilege that unjustified force is disproportionately used against Māori in police encounters and arrests

Constantly being under the watchful eye of the law must be a special privilege indeed

Was it a special privilege that Māori had to start occupying confiscated land in 1977 starting at Bastion Point in an effort to finally get some redress to the massive loss of tribal land, An occupation that lasted for over a year before it was brutally put down by the police and Army

Bash our heads, it's our privilege as Māori

And then there's that special privilege that Māori love and enjoy called the 2004 Foreshore and Seabed Act an act that takes the aforementioned and places them in the hands of the crown as opposed to the public domain or as was guaranteed by Te Tiriti and then promptly confiscated from guardianship and ownership of Māori. Luckily this bill was repealed in 2010 and replaced with the Marine and Coastal Act 2011 which guaranteed the right to access justice through courts but only if Māori could exercise that special privilege they have.

Can they show that their rights to the foreshore and seabed have been exercised since 1840, in accordance with Tikanga Māori, without substantial interruption and was not interrupted by law, say a law passed in 1863. Then if so, by special privilege then they can put it before the courts. In 2024 they got even more special privileges when the Government ignored the courts recommendation to lower the threshold of proof and required Māori to prove they had had continual exclusive use and ownership since 1840 to have a chance to get confiscated foreshore lands back

Yay the privilege of ever-moving goalposts

Did the privilege start in 1988 when the Crown returned Bastion Point to Ngati Whatua after a prolonged court case or was it in 1989 when the first Ti Tiriti O Waitangi settlement was done giving Waitomo Caves back to Uekaha Hapu or was it 1987 when Te Reo was recognised as an official Language or was it the early 2000s when Bilingual signs started being put up around Aotearoa or was it in 2024 when the Government banned Bilingual signs on roads and in government buildings?

Was it in 1867 when the Māori were granted 4 parliamentary seats, given the Maori population at the time compared to Pakeha it should have been more although it could have been 1868 when Māori men got the right to vote? Oddly it was 11 years before pakeha men were given that right, before then, only landowners could vote and because Māori held land in common all of them could vote

Was it in 1880 were several hundred prisoners from the Māori peaceful protest group Parihaka were held and treated to 2 years hard labour without trial and their settlements burnt and confiscated

Was it in 1977 when race was added to the Human Rights Commission as something you couldn't discriminate against as well as gender, religion or beliefs?

Was it in 1977 when a section was added to the Race Relations Act that made it illegal to publish, broadcast, or make public statements that were likely to incite hostility or ill-will against a group of people based on their: Color, Race, and Ethnic or national origins

Was it after 130 years of being ground down and stepped on and murdered and marginalised and robbed, that laws were made that said, you know we probably shouldn't have been doing that

Is the privilege the knowledge of what 184 years of all of the above does to a people, the hurt that it causes deep into the bone

Is it that in the 40 years since that Human Rights Commission rule that Māori have begun to hold up their heads, to be proud of who they are, to speak their language and to rediscover their culture?

To speak out against things that are wrong in the health system, the education system, the justice system, the welfare system and the political system. To demand, not ask but demand redress for the crimes that the Crown has not only done against them but encouraged others to do to them.

Did the Privilege start when the Waitangi Tribunal awarded 6 cents for every dollar of land confiscated? If you want that broken down, for every million dollars worth of land confiscated, the reparations were only $60000

Is it because New Zealand as a society got used to seeing them be shy, and humble and hard-working and lost amid the diaspora that pakeha society caused?

That society got used to being able to exploit the bits of Māori culture we liked, like the music and the humour and the strong back and compliance and when they found their voice and took it back and that redress was happening and suddenly, they were privileged because how dare they not be happy with scraps from the table.

That Māori were no longer being the Good Māori.

Is the privilege that in 2024, 184 years after the signing of Te Tiriti, Māori are finally getting a fraction of what they should have had if Te Tiriti had been honoured

One other question to the Pakeha of Aotearoa New Zealand

If all of this looks like a Privilege. Do any of you want to swap places?"

#maori#maori culture#new zealand politics#nzpol#treaty principles bill#treaty of waitangi#indigenous culture

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

The rapid expansion of AI infrastructure is driving a surge in data center energy consumption

Indigenous knowledge systems, such as Māori kaitiakitanga and Aboriginal Country, offer sustainable alternatives for digital governance that prioritize environmental and cultural responsibility.

The AI industry’s growing resource consumption, including massive energy and water use, highlights the urgency of integrating Indigenous data sovereignty frameworks into global technology policy.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

bog tour - countdown to 1 year of games

T MINUS 3 DAYS

In the penultimate bog tour post, where I post author's commentary on each of my games in the 16 days leading up to my 1 year TTRPG design anniversary, we're discussing 'Earth Mother, Sky Father'!

'Earth Mother, Sky Father' is a two player conversation game about the Māori creation story of Ranginui, the sky father, and Papatūānuku, the earth mother. The players will ask 7 questions between each other, following branching paths to explore different aspects of their relationship.

Thoughts

Hoooo, EMSF my absolute beloved!!!

To my knowledge, this is the first internet published Māori focused TTRPG, outside of like, extremely racist game settings of New Zealand. A kickstarter launched not long after I published this, claiming to be the first Māori TTRPG, but I disagree! The day after I posted this one, someone else posted a system agnostic Māori stories inspired setting guide. #trendsetter? Or just really good timing on my part, more likely!

Check up this unhinged way I tracked the branching paths and topics of questions:

Just noticed now I didn't finish the last few as I was writing them. Damn. Probably forgot to save! The part in the bottom left corner is bc I copy pasted the whole of the farmer and the bog body so I didn't have to redo the 'proceed to x' branches.

In this game, I made two PDFs, one that has audio links for each instance of te reo Māori used in the text and one that's just the text! It was a lot of work, and I wish I'd found a better way to embed the audio than linking to a google drive link ugh. If anyone knows one, please let me know and I can do an updated pdf!

I first thought of this game when I read Morgan Davie of Taleturn's 'The Oracle and The Curse' upon reading the 7 Questions RPG system, but didn't think I had the skills to do it at that point. At some point I was like 'fuck it, if I keep waiting till I think I'm skilled and knowledgeable enough, I'll never make it' and just did it!

One thing I do think about is if I should have made Rangi and Papa more tonally distinct.

Fav things

All the te reo Māori content! My good friend Ruataupare helped me with all the te reo translations. I gave my best attempt at the sentences, and they made them actually be right.

One of the question is 'Do you ever feel that we’re simply playing roles in a story?'. The meta narrative of it all!!!

The question: 'Will you ever stop looking for me in everything?'

This section, from Rangi to Papa:

Have I said yet that I love you? Have I said it lately? Have I told you that despite our distance, you remain in my heart, and will live there forever. A part of me is with you, and a part of you is with me. Our wholeness disappeared when our children pushed us apart. Have I told you that I love you? Have I impressed upon you the depth of my care and affection for you?

The question: 'What grief do you carry close to your heart, my love?'

Stats

'Earth Mother, Sky Father' has 802 views (the highest of my games!) and 145 downloads (2nd highest). It has 8 ratings, and is in 38 collections (5th highest).

'Earth Mother, Sky Father' is a game about the aftermath of the indigenous Māori creation story. Explore the relationships of two atua (deities), and their relationships with each other, their family, and the world around them. Get it for $2.99USD or for free if you're BIPOC, here.

Tomorrow is our final game commentary bog tour, with the game 'rhyme on the radar; an assemblage of micro rpgs'. Hei āpōpō, e hoa mā!

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

By: Robert E. Bartholomew

Published: Apr 30, 2025

“It is fundamental in science that no knowledge is protected from challenge. … Knowledge that requires protection is belief, not science.” —Peter Winsley

There is growing international concern over erosion of objectivity in both education and research. When political and social agendas enter the scientific domain there is a danger that they may override evidence-based inquiry and compromise the core principles of science. A key component of the scientific process is an inherent skeptical willingness to challenge assumptions. When that foundation is replaced by a fear of causing offense or conforming to popular trends, what was science becomes mere pseudoscientific propaganda employed for the purpose of reinforcing ideology.

When Europeans formally colonized New Zealand in 1840 with the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi, the culture of the indigenous Māori people was widely disparaged and their being viewed an inferior race. One year earlier historian John Ward described Māori as having “the intellect of children” who were living in an immature society that called out for the guiding hand of British civilization.1 The recognition of Māori as fully human, with rights, dignity, and a rich culture worthy of respect, represents a seismic shift from the 19th century attitudes that permeated New Zealand and much of the Western world, and that were used to justify the European subjugation of indigenous peoples.

Since the 1970s, Māori society has experienced a cultural Renaissance with a renewed appreciation of the language, art, and literature of the first people to settle Aotearoa—“the land of the long white cloud.” While speaking Māori was once banned in public schools, it is now thriving and is an official language of the country. Learning about Māori culture is an integral part of the education system that emphasizes that it is a treasure (taonga) that must be treated with reverence. Māori knowledge often holds great spiritual significance and should be respected. Like all indigenous knowledge, it contains valuable wisdom obtained over millennia, and while it contains some ideas that can be tested and replicated, it is not the same as science.

For example, Māori knowledge encompasses traditional methods for rendering poisonous karaka berries safe for consumption. Science, on the other hand, focuses on how and why things happen, like why karaka berries are poisonous and how the poison can be removed.2 The job of science is to describe the workings of the natural world in ways that are testable and repeatable, so that claims can be checked against empirical evidence—data gathered from experiments or observations. That does not mean we should discount the significance of indigenous knowledge—but these two systems of looking at the world operate in different domains. As much as indigenous knowledge deserves our respect, we should not become so enamoured with it that we give it the same weight as scientific knowledge.

The Māori Knowledge Debate

In recent years the government of New Zealand has given special treatment to indigenous knowledge. The issue came to a head in 2021, when a group of prominent academics published a letter expressing concern that giving indigenous knowledge parity with science could undermine the integrity of the country’s science education. The seven professors who signed the letter were subjected to a national inquisition. There were public attacks by their own colleagues and an investigation by the New Zealand Royal Society on whether to expel members who had signed the letter.3

Ironically, part of the reason for the Society’s existence is to promote science. At its core is the issue of whether “Māori ancient wisdom” should be given equal status in the curriculum with science, which is the official government position.4 This situation has resulted in tension in the halls of academia, where many believe that the pendulum has now swung to another extreme. Frustration and unease permeate university campuses as professors and students alike walk on eggshells, afraid to broach the subject for fear of being branded racist and anti-Māori, or subjected to personal attacks or harassment campaigns.

The Lunar Calendar

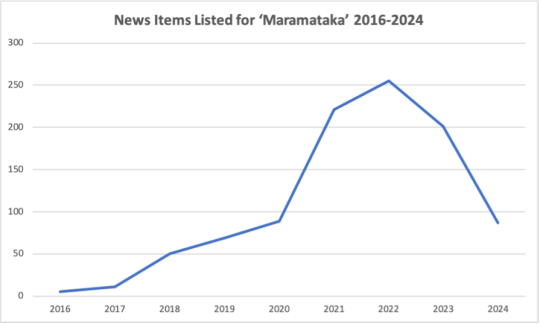

Infatuation with indigenous knowledge and the fear of criticising claims surrounding it has infiltrated many of the country’s key institutions, from the health and education systems to the mainstream media. The result has been a proliferation of pseudoscience. There is no better example of just how extreme the situation has become than the craze over the Māori Lunar Calendar. Its rise is a direct result of what can happen when political activism enters the scientific arena and affects policymaking. Interest in the Calendar began to gain traction in late 2017.

[ An example of the Maramataka Māori lunar calendar ]

Since then, many Kiwis have been led to believe that it can impact everything from horticulture to health to human behavior. The problem is that the science is lacking, but because of the ugly history of the mistreatment of the Māori people, public institutions are afraid to criticize or even take issue anything to do with Māori culture. Consider, for example, media coverage. Between 2020 and 2024, there were no less than 853 articles that mention “maramataka”—the Māori word for the Calendar which translates to “the turning of the moon.” After reading through each text, I was unable to identify a single skeptical article.5 Many openly gush about the wonders of the Calendar, and gave no hint that it has little scientific backing.

[ Based on the Dow Jones Factiva Database ]

The Calendar once played an important role in Māori life, tracking the seasons. Its main purpose was to inform fishing, hunting, and horticultural activities. There is some truth in the use of specific phases or cycles to time harvesting practices. For instance, some fish are more active or abundant during certain fluctuations of the tides, which in turn are influenced by the moon’s gravitational pull. Two studies have shown a slight increase in fish catch using the Calendar.6 However, there is no support for the belief that lunar phases influence human health and behavior, plant growth, or the weather. Despite this, government ministries began providing online materials that feature an array of claims about the moon’s impact on human affairs. Fearful of causing offense by publicly criticizing Māori knowledge, the scientific position was usually nowhere to be found.

Soon primary and secondary schools began holding workshops to familiarize staff with the Calendar and how to teach it. These materials were confusing for students and teachers alike because most were breathtakingly uncritical and there was an implication that it was all backed by science. Before long, teachers began consulting the maramataka to determine which days were best to conduct assessments, which days were optimal for sporting activities, and which days were aligned with “calmer activities at times of lower energy phases.” Others used it to predict days when problem students were more likely to misbehave.7

As one primary teacher observed: “If it’s a low energy day, I might not test that week. We’ll do meditation, mirimiri (massage). I slowly build their learning up, and by the time of high energy days we know the kids will be energetic. You’re not fighting with the children, it’s a win-win, for both the children and myself. Your outcomes are better.”8 The link between the Calendar and human behavior was even promoted by one of the country’s largest education unions.9 Some teachers and government officials began scheduling meetings on days deemed less likely to trigger conflict,10 while some media outlets began publishing what were essentially horoscopes under the guise of ‘ancient Māori knowledge.’11

The Calendar also gained widespread popularity among the public as many Kiwis began using online apps and visiting the homepages of maramataka enthusiasts to guide their daily activities. In 2022, a Māori psychiatrist published a popular book on how to navigate the fluctuating energy levels of Hina—the moon goddess. In Wawata Moon Dreaming, Dr. Hinemoa Elder advises that during the Tamatea Kai-ariki phase people should: “Be wary of destructive energies,”12 while the Māwharu phase is said to be a time of “female sexual energy … and great sex.”13 Elder is one of many “maramataka whisperers” who have popped up across the country.

By early 2025, the Facebook page “Maramataka Māori” had 58,000 followers,14 while another, “Living by the Stars” on Māori Astronomy had 103,000 admirers.15 Another popular book, Living by the Moon, also asserts that lunar phases can affect a person’s energy levels and behavior. We are told that the Whiro phase (new moon) is associated with troublemaking. It even won awards for best educational book and best Māori language resource.16 In 2023, Māori politician Hana Maipi-Clarke, who has written her own book on the Calendar, stood up in Parliament and declared that the maramataka could foretell the weather.17

A Public Health Menace

Several public health clinics have encouraged their staff to use the Calendar to navigate “high energy” and “low energy” days and help clients apply it to their lives. As a result of the positive portrayal of the Calendar in the Kiwi media and government websites, there are cases of people discontinuing their medication for bipolar disorder and managing contraception with the Calendar.18 In February 2025, the government-funded Māori health organization, Te Rau Ora, released an app that allows people to enhance their physical and mental health by following the maramataka to track their mauri (vital life force).

While Te Rau Ora claims that it uses “evidence-based resources,” there is no evidence that mauri exists, or that following the phases of the moon directly affects health and well-being. Mauri is the Māori concept of a life force—or vital energy—that is believed to exist in all living beings and inanimate objects. The existence of a “life force” was once the subject of debate in the scientific community and was known as “vitalism,” but no longer has any scientific standing.19 Despite this, one of app developers, clinical psychologist Dr. Andre McLachlan, has called for widespread use of the app.20 Some people are adamant that following the Calendar has transformed their lives, and this is certainly possible given the belief in its spiritual significance. However, the impact would not be from the influence of the Moon, but through the power of expectation and the placebo effect.

No Science Allowed

While researching my book, The Science of the Māori Lunar Calendar, I was repeatedly told by Māori scholars that it was inappropriate to write on this topic without first obtaining permission from the Māori community. They also raised the issue of “Māori data sovereignty”—the right of Māori to have control over their own data, including who has access to it and what it can be used for. They expressed disgust that I was using “Western colonial science” to validate (or invalidate) the Calendar.

This is a reminder of just how extreme attempts to protect indigenous knowledge have become in New Zealand. It is a dangerous world where subjective truths are given equal standing with science under the guise of relativism, blurring the line between fact and fiction. It is a world where group identity and indigenous rights are often given priority over empirical evidence. The assertion that forms of “ancient knowledge” such as the Calendar, cannot be subjected to scientific scrutiny as it has protected cultural status, undermines the very foundations of scientific inquiry. The expectation that indigenous representatives must serve as gatekeepers who must give their consent before someone can engage in research on certain topics is troubling. The notion that only indigenous people can decide which topics are acceptable to research undermines intellectual freedom and stifles academic inquiry.

While indigenous knowledge deserves our respect, its uncritical introduction into New Zealand schools and health institutions is worrisome and should serve as a warning to other countries. When cultural beliefs are given parity with science, it jeopardizes public trust in scientific institutions and can foster misinformation, especially in areas such as public health, where the stakes are especially high.

#Maramataka Māori#Maramataka#indigenous knowledge#Māori lunar calendar#pseudoscience#what science is#science#indigenous wisdom#other ways of knowing#epistemology#ways of knowing#mauri#objective reality#objectivity#Western colonial science#religion is a mental illness

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

the foundation of Thaumaturgy (worldbuilding symbol)

I was designing patterns for a character's clothing tonight and eventually got lost in creating sigils for my magic system. here I created what is probably going to be the most important and commonly used sigil throughout the world of Vär Mäne. A visual representation of the very foundation of Thaumaturgy, everything else thus building off of it.

I don't have a name for this sigil yet, that's something I'll need to think on for awhile (if you know anything about my writing, it's that I overthink names like a maniac). This symbol is a marriage of two already existing symbols: the Māori Koru, a symbol based on an unfurling fern frond; and the Celtic Triskelion. Don't worry, I'll rewrite what my notes say, I'm aware of my abhorrent handwriting.

The Koru represents new life, growth, continuous cycles of life, strength, and peace. This is presented through the spiral shape (nearly universally recognized as a symbol of life and cycles) and the plant effigy; the growth of a brand new life and the unfurling of its body, future, and potential.

The Triskelion represents many, many things. whether or not through strange coincidence, reality can be broken down into threes.

The Cycle: life, death, rebirth.

The Realms: earth, sea, sky.

The Family: mother, father, child.

The Triskele represents interconnectedness in every way. The symbol has no end and no beginning, it is simply an unending spiral. The Triskelion also has its roots in goddesses and women, sometimes being used as a symbol of female power. As we all know, women are the origin of all life and are the creators of witchcraft.

My blend of these symbols represents every one of these things. every state of being, every realm, every element. In the center is the Koru, or silver fern frond. it represents what we know. This is life and the present. our physical bodies, our senses, our experiences, our collective knowledge.

On the edges are the three spirals of the Triskelion. These are the cycles that have and will repeat through all of time. This is the past and the circle of life. Life or birth, death, and rebirth or afterlife (depending on who you ask or what practice of Thaumaturgy you are engaging in). These also represent the mind, body, and spirit; the earth, sky, and sea; and the physical world, spiritual world, and the gap(1)/bridge/intermingling between the two.

The three dots or ellipse petering off is also inspired by the Koru(2). it represents what we don't know yet. This is the future, death, and higher forms of existence that mortals cannot experience.

Lastly, the lines connected to all of these elements simply represent the inherent interconnectedness of all things. These lines can also be seen as Leylines, since Leylines are quite literally the energetic pathways between all living things.

This sigil can be built off of to create new symbols and perform acts of Thaumaturgy. Here is a very rough example:

I have added the Adinkra African symbol Aya, which is a fern (yes, you're seeing a lot of ferns here. If you're familiar with mythology or paganism, you'll know ferns are a pretty important plant. they're also just my favorite and cool as hell). Other than meaning "fern" in a simple language context, the Aya is a symbol of endurance, resourcefulness, resilience, and defiance. Ferns are famously hardy plants. They are incredibly tolerant and can grow in the worst conditions. extreme heat, cold, and damaged ecosystems. They are stubborn. After an upheaval event, ferns are one of the first plants to reestablish itself. Scientists have even suggested that ferns can act as facilitators for ecosystem recovery, easing the way for other plants and animals(3).

This is only a first-draft idea of the kinds of sigils that can be created, but I imagine this could be a sigil for an endurance spell. offering the resilient qualities of the fern to the affected Thaumaturgist. Which branch of the symbol that is being altered should be noted. I may change the place in which the Aya is added for this particular spell depending on which spiral represents what. Another layer I'll need to consider when creating more sigils.

This is all I have so far for the sigilistic/runeric property of Thaumaturgy. You can read this blog entry for some more context on Thaumaturgy and other terms used here that you may not be familiar with. Thank you for reading !!

Footnotes:

1. on Vär Mäne, this gap is called the Ginnungagap. Sometimes it is referred to as a literal place, a metaphysical plane, or state of mind or consciousness.

The Ginnungagap is a primordial, magical void from Norse mythology.

2. I am unsure if this is actually a part of the symbol. I saw it in a singular rendition of the symbol, but no others. I really, really like the way it looks though, so I included it.

3. https://phys.org/news/2024-12-ferns-ancient-resilience-aids-modern.html

#The Blackout#worldbuilding#fantasy#sigil magic#magic system#fantasy worldbuilding#fantasy writing#mythology#fantasy magic#symbols#witchcraft#runes

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

“The threats of data colonialism are real,” says Tahu Kukutai, a professor at New Zealand’s University of Waikato and a founding member of Te Mana Raraunga, the Māori Data Sovereignty Network. “They’re a continuation of old processes of extraction and exploitation of our land—the same is being done to our information.” To shore up their defenses, some Indigenous groups are developing new privacy-first storage systems that give users control and agency over all aspects of this information: what is collected and by whom, where it’s stored, how it’s used and, crucially, who has access to it. Storing data in a user’s device—rather than in the cloud or in centralized servers controlled by a tech company—is an essential privacy feature of these technologies. Rudo Kemper is founder of Terrastories, a free and open-source app co-created with Indigenous communities to map their land and share stories about it. He recalls a community in Guyana that was emphatic about having an offline, on-premise installation of the Terrastories app. To members of this group, the issue was more than just the lack of Internet access in the remote region where they live. “To them, the idea of data existing in the cloud is almost like the knowledge is leaving the territory because it’s not physically present,” Kemper says. Likewise, creators of Our Data Indigenous, a digital survey app designed by academic researchers in collaboration with First Nations communities across Canada, chose to store their database in local servers in the country rather than in the cloud. (Canada has strict regulations on disclosing personal information without prior consent.) In order to access this information on the go, the app’s developers also created a portable backpack kit that acts as a local area network without connections to the broader Internet. The kit includes a laptop, battery pack and router, with data stored on the laptop. This allows users to fill out surveys in remote locations and back up the data immediately without relying on cloud storage.

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

I hope you don’t mind me adding to your post! In Australia the aboriginal peoples had similar systems. The use of fire (and water wells) as a tool for manipulating the landscape is the topic of the book The Biggest Estate On Earth by Bill Gammage.

Most of the sources referenced in the book are actually from white European settlers / colonisers describing how the landscape looks as they ‘explore’ it. They talk about how it looks like the French palace gardens. They outline how there are specific areas that seem to work in harmony with each other e.g. shady forest next to short grass where kangaroos graze, separated by areas of dense bush. The authors of these recounts do not realise it was a purposeful creation by the indigenous peoples.

When the Europeans began committing a genocide upon the indigenous peoples, killing them and driving them away from the land, the land was no longer being looked after. One coloniser discussed how a journey which had taken 3 days three years previously, now took 5 days — much of which was spent cutting through dense bush, which had grown in place of the cultivated forests and grasslands of what is now regional New South Wales.

Today, just as in the North American continent, Australia has devastating bushfires, worsened through both climate change and the loss of indigenous fire practices. Many native flora and fauna are at risk of extinction, as imported plants and pest animals overtake their ecological niches.

I didn’t realise how similar the land management practices of First Nations’ peoples across continents were, so I thought I’d share the bit that I know. The purposeful erasure of indigenous knowledge and practices contributes to the ongoing colonisation of our nations, and does no good to the environment itself.

There’s also a book on the land practices of the Māori peoples in Aotearoa (New Zealand), called Ngā Uruora: The Groves of Life by Geoff Park. I haven’t read any of this book yet, but my impression of it is that it follows along the same vein.

What I was taught growing up: Wild edible plants and animals were just so naturally abundant that the indigenous people of my area, namely western Washington state, didn't have to develop agriculture and could just easily forage/hunt for all their needs.

The first pebble in what would become a landslide: Native peoples practiced intentional fire, which kept the trees from growing over the camas praire.

The next: PNW native peoples intentionally planted and cultivated forest gardens, and we can still see the increase in biodiversity where these gardens were today.

The next: We have an oak prairie savanna ecosystem that was intentionally maintained via intentional fire (which they were banned from doing for like, 100 years and we're just now starting to do again), and this ecosystem is disappearing as Douglas firs spread, invasive species take over, and land is turned into European-style agricultural systems.

The Land Slide: Actually, the native peoples had a complex agricultural and food processing system that allowed them to meet all their needs throughout the year, including storing food for the long, wet, dark winter. They collected a wide variety of plant foods (along with the salmon, deer, and other animals they hunted), from seaweeds to roots to berries, and they also managed these food systems via not only burning, but pruning, weeding, planting, digging/tilling, selectively harvesting root crops so that smaller ones were left behind to grow and the biggest were left to reseed, and careful harvesting at particular times for each species that both ensured their perennial (!) crops would continue thriving and that harvest occurred at the best time for the best quality food. American settlers were willfully ignorant of the complex agricultural system, because being thus allowed them to claim the land wasn't being used. Native peoples were actively managing the ecosystem to produce their food, in a sustainable manner that increased biodiversity, thus benefiting not only themselves but other species as well.

So that's cool. If you want to read more, I suggest "Ancient Pathways, Ancestral Knowledge: Ethnobotany and Ecological Wisdom of Indigenous Peoples of Northwestern North America" by Nancy J. Turner

61K notes

·

View notes

Text

“just a few things that justice requires of Tangata Tiriti:

1. Be tau (at peace) with your position. You need to be able to speak frankly about the process of colonization that created the space for you to be here in Aotearoa. Not ridden with guilt, and not trying to explain it or evade it, but ready to respond to the legacy of that story. Be aware of your own privilege that has descended down to you by virtue of that process. Even in describing your own class, gender, ability or sexuality based oppression, you should know how the legacy of colonization influences your experience of that oppression.

2. Respect boundaries. So much space has been taken from us, so primarily you need to respect our boundaries where we lay them down. Don’t argue with us when we insist on our own spaces. Don’t make it about your hurt feelings, or your need for inclusion. Don’t paint it as divisive. If you are mourning the space we have just reclaimed for ourselves, be comforted by the fact that pretty much the entire rest of the world is either yours, or shared with you. We require safe spaces to speak, just us. That will also require you to self identify and self vacate at times. Be proactive. Read the room. Remove yourself out of consideration for the space we need to safely continue a conversation.

3. Be prepared to make sacrifice. If you understand the story of privilege that has shaped Aotearoa you will understand there has been a mass transfer of power. Justice cannot be restored without addressing the power imbalance.

If you are only interested in discussing the past but not responding to it, then you are of no use to the process of restoring justice, and I do have to question whether you are really adverse to racism and the benefits you enjoy from it.

This will mean learning the art of saying no. No to sitting on panels on Indigenous issues. No to occupying roles and positions where you are paid to impart (and judge) Indigenous knowledge. No to opportunities where systemic failings allow you to accept funding to lead Indigenous projects.

4. There will be many spaces where your voice will be valued. Speaking to your fellow pākeha about being good Tangata Tiriti. Discussing what it means to be pākeha. Dispelling fear of decolonization. There is a perverse situation right now where pakeha do not want to do the work on themselves, but they DO want to do the work of telling Maori how to be Maori. Because the system supports this kind of behaviour, you wind up with Maori supplementing the workload, and spending way too much time teaching pakeha about their Tiriti responsibilities, rather than working with our own (which we’d much rather do). There is an important space for Tangata Tiriti right now, and it’s not teaching Maori – it’s working with each other on how to reckon with the historical injustice of their establishment, and what to DO about that, now.

5. Stand with us for our language rights, for our health rights, for the rights of our children and women and stop perceiving Indigenous rights abuses as an Indigenous problem, rather than a colonial inevitability.

6. Benchmark the discomfort of your decolonization experience against that of our colonization experience, every time you want to ask us to wait...

7. Understand that learning our content and knowing our experience are two different things. For this reason we do want you to learn, and lead, your own karakia and waiata… But that does not equate to permission to explain our own culture to us. Remember, boundaries. Learning the reo is not your get out of Treaty free card.

8. Don’t expect us to know everything about Te Ao Māori or have our own identity journey sorted out for you. Colonization has made, and is still making a mess of our identity, and our relationships, and that is difficult enough without having to explain ourselves to you. Especially when you have yet to do the hard work on your own identity as pakeha.

9. Nothing is automatically a 2 way street. I, for instance, can talk frankly about what a good Tangata Tiriti looks like. Tangata Tiriti cannot tell me what being a “good” Tangata Whenua is. This requires you to learn well beyond Treaty/Tiriti articles, or provisions, or principles. Privilege. Power. Bias. Racism. Learn how these operate in the context of Tiriti justice and you will get a better idea of how to navigate relationships as a Tangata Tiriti beyond the very flawed “anti-racism means treating everyone the same” fallacy.

10. Don’t expect backpats or thankyous. You may get them (in fact you probably will – it’s another product of our colonial experience that pakeha are thanked and recognized for doing Tiriti justice work much more than Māori), but it’s important you realise that justice work is as much for yourself as it is for anyone else. It’s self-improvement, and improvement of your children’s future. You’re not doing me favours that you aren’t also doing yourself.”

#what it means to be tangata tiriti#tangata tiriti#tangata whenua#māori rights#māori sovereignty#Tiriti o Waitangi#Aotearoa#Aotearoa NZ#New Zealand#pākehā#indigenous rights#indigenous sovereignty#anti colonialism#decolonization#decolonize the world

1 note

·

View note

Text

How Indigenous Groups Are Leading the Way on Data Privacy

Indigenous groups are developing data storage technology that gives users privacy and control. Could their work influence those fighting back against invasive apps?

Rina Diane Caballar

A person in a purple tshirt wallking in a forest

A member of the Wayana people in the Amazon rain forest in Maripasoula, French Guiana. Some in the Wayana community use the app Terrastories as part of their mapping project.

Emeric Fohlen/NurPhoto via Getty Images

Indigenous groups are developing data storage technology that gives users privacy and control. Could their work influence those fighting back against invasive apps?

Even as Indigenous communities find increasingly helpful uses for digital technology, many worry that outside interests could take over their data and profit from it, much like colonial powers plundered their physical homelands. But now some Indigenous groups are reclaiming control by developing their own data protection technologies—work that demonstrates how ordinary people have the power to sidestep the tech companies and data brokers who hold and sell the most intimate details of their identities, lives and cultures.

When governments, academic institutions or other external organizations gather information from Indigenous communities, they can withhold access to it or use it for other purposes without the consent of these communities.

“The threats of data colonialism are real,” says Tahu Kukutai, a professor at New Zealand’s University of Waikato and a founding member of Te Mana Raraunga, the Māori Data Sovereignty Network. “They’re a continuation of old processes of extraction and exploitation of our land—the same is being done to our information.”

To shore up their defenses, some Indigenous groups are developing new privacy-first storage systems that give users control and agency over all aspects of this information: what is collected and by whom, where it’s stored, how it’s used and, crucially, who has access to it.

Storing data in a user’s device—rather than in the cloud or in centralized servers controlled by a tech company—is an essential privacy feature of these technologies. Rudo Kemper is founder of Terrastories, a free and open-source app co-created with Indigenous communities to map their land and share stories about it. He recalls a community in Guyana that was emphatic about having an offline, on-premise installation of the Terrastories app. To members of this group, the issue was more than just the lack of Internet access in the remote region where they live. “To them, the idea of data existing in the cloud is almost like the knowledge is leaving the territory because it’s not physically present,” Kemper says.

Likewise, creators of Our Data Indigenous, a digital survey app designed by academic researchers in collaboration with First Nations communities across Canada, chose to store their database in local servers in the country rather than in the cloud. (Canada has strict regulations on disclosing personal information without prior consent.) In order to access this information on the go, the app’s developers also created a portable backpack kit that acts as a local area network without connections to the broader Internet. The kit includes a laptop, battery pack and router, with data stored on the laptop. This allows users to fill out surveys in remote locations and back up the data immediately without relying on cloud storage.

Āhau, a free and open-source app developed by and for Māori to record ancestry data, maintain tribal registries and share cultural narratives, takes a similar approach. A tribe can create its own Pātaka (the Māori word for storehouse), or community server, which is simply a computer running a database connected to the Internet. From the Āhau app, tribal members can then connect to this Pātaka via an invite code, or they can set up their database and send invite codes to specific tribal or family members. Once connected, they can share ancestry data and records with one another. All of the data are encrypted and stored directly on the Pātaka.

Another privacy feature of Indigenous-led apps is a more customized and granular level of access and permissions. With Terrastories, for instance, most maps and stories are only viewable by members who have logged in to the app using their community’s credentials—but certain maps and stories can also be made publicly viewable to those who do not have a login. Adding or editing stories requires editor access, while creating new users and modifying map settings requires administrative access.

For Our Data Indigenous, access levels correspond to the ways communities can use the app. They can conduct surveys using an offline backpack kit or generate a unique link to the survey that invites community members to complete it online. For mobile use, they can download the app from Google Play or Apple’s App Store to fill out surveys. The last two methods do require an Internet connection and the use of app marketplaces. But no information about the surveys is collected, and no identifying information about individual survey participants is stored, according to Shanna Lorenz, an associate professor at Occidental College in Los Angeles and a product manager and education facilitator at Our Data Indigenous.

Such efforts to protect data privacy go beyond the abilities of the technology involved to also encompass the design process. Some Indigenous communities have created codes of use that people must follow to get access to community data. And most tech platforms created by or with an Indigenous community follow that group’s specific data principles. Āhau, for example, adheres to the Te Mana Raraunga principles of Māori data sovereignty. These include giving Māori communities authority over their information and acknowledging the relationships they have with it; recognizing the obligations that come with managing data; ensuring information is used for the collective benefit of communities; practicing reciprocity in terms of respect and consent; and exercising guardianship when accessing and using data. Meanwhile Our Data Indigenous is committed to the First Nations principles of ownership, control, access and possession (OCAP). “First Nations communities are setting their own agenda in terms of what kinds of information they want to collect,” especially around health and well-being, economic development, and cultural and language revitalization, among others, Lorenz says. “Even when giving surveys, they’re practicing and honoring local protocols of community interaction.”

Crucially, Indigenous communities are involved in designing these data management systems themselves, Āhau co-founder Kaye-Maree Dunn notes, acknowledging the tribal and community early adopters who helped shape the Āhau app’s prototype. “We’re taking the technology into the community so that they can see themselves reflected back in it,” she says.

For the past two years, Errol Kayseas has been working with Our Data Indigenous as a community outreach coordinator and app specialist. He attributes the app’s success largely to involving trusted members of the community. “We have our own people who know our people,” says Kayseas, who is from the Fishing Lake First Nation in Saskatchewan. “Having somebody like myself, who understands the people, is only the most positive thing in reconciliation and healing for the academic world, the government and Indigenous people together.”

This community engagement and involvement helps ensure that Indigenous-led apps are built to meet community needs in meaningful ways. Kayseas points out, for instance, that survey data collected with the Our Data Indigenous app will be used to back up proposals for government grants geared toward reparations. “It’s a powerful combination of being rooted in community and serving,” Kukutai says. “They’re not operating as individuals; everything is a collective approach, and there are clear accountabilities and responsibilities to the community.”

Even though these data privacy techniques are specific to Indigenous-led apps, they could still be applied to any other app or tech solution. Storage apps that keep data on devices rather than in the cloud could find adopters outside Indigenous communities, and a set of principles to govern data use is an idea that many tech users might support. “Technology obviously can’t solve all the problems,” Kemper says. “But it can—at least when done in a responsible way and when cocreated with communities—lead to greater control of data.”

1 note

·

View note

Text

The First One Now Will Later Be Last…

Within the labyrinth of language, where meanings often intermingle, two words—"indigent" and "indigenous"—stand as a testament to the complexity and irony of expression. Despite their disparate origins and definitions, an unintended bridge forms between them, highlighting the unforgiving path that many indigenous communities have tread. This linguistic anomaly draws attention to the poignant reality that historical injustices and systemic inequalities have tragically transformed "indigenous" peoples into the "indigent."

The word "indigenous" comes from the Latin indigena, meaning "born in a country" or "native." It is formed from the prefix "in-" (meaning "in" or "within") and "dignus" (meaning "worthy" or "appropriate"). Over time, this term has evolved to refer to people, cultures, or things that are native to a particular region, indicating a deep historical connection to that place.

Conversely, "indigent" is derived from the Latin indigens, meaning "needy" or "lacking." It is formed from the prefix "in-" (meaning "not" or "without") and "egens" (meaning "needy" or "requiring"). The root egens is derived from egere, which means "to lack" or "to need." Thus, "indigent" describes individuals or groups who are lacking financial resources or living in poverty.

While these terms possess distinct roots and meanings, their phonetic similarity can sometimes lead to confusion or unintended associations. This phenomenon, known as "false cognates," typically refers to words in different languages that appear similar but have different meanings. Although "indigenous" and "indigent" are not false cognates in the traditional sense, they illustrate how language can sometimes create unexpected connections between unrelated concepts.

Unfortunately, many indigenous communities worldwide have become indigent due to historical manipulation, greed, and systemic oppression. The sad reality is that many Native American communities face significant persecutions leading to economic hardship and poverty. Historical injustices—such as forced displacement from ancestral lands, cultural suppression, and systemic discrimination—have contributed to their marginalized status within society.

And they was here first.

The plight of indigenous Australians, including Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, continues to expose socioeconomic disparities bestowed upon native peoples. Historical colonization, land dispossession and ongoing systemic issues have contributed to their indigent status.

Similarly, the Māori people in New Zealand have dealt with land confiscation, loss of cultural heritage, and socioeconomic disparities that have led to their indigent status in certain areas. In Canada, many First Nations communities have experienced intergenerational trauma from the legacy of residential schools, loss of land, and limited access to resources, leading to high poverty rates and other socioeconomic challenges similar to those faced by Native Americans.

In Africa, groups such as the Bushmen, Pygmies, and Maasai exemplify this struggle. The San people, known as Bushmen or Basarwa, inhabit regions in southern Africa and are renowned for their intricate knowledge of the land and their traditional hunting and gathering lifestyle. Pygmy groups like the Aka, Baka, and Mbuti are found in central Africa and have faced similar socio-economic challenges. The Maasai, a semi-nomadic pastoralist community in Kenya and Tanzania, are recognized for their distinct culture yet also contend with ongoing hardships.

In the somber aftermath of exploration, conquest, and colonization, the lives of many indigenous communities have been shaped by forces beyond their control. This linguistic interplay between "indigent" and "indigenous" reflects an uncomfortable truth: the proud inheritors of ancient traditions, custodians of ancestral lands, have found themselves ensnared and enslaved by poverty and marginalization.

And it ain't no accident

It's what we call manifest destiny.

The connection between "indigent" and "indigenous" serves as a powerful reminder of the systemic inequalities that persist today. Addressing these cruelties requires not only recognition of the linguistic and historical context but also a commitment to justice and equality. As we engage with these terms, we must consider our roles in perpetuating or dismantling these injustices.

To move forward, society must prioritize policies that empower indigenous communities, ensuring their voices are heard and their rights respected. This includes advocacy for land rights, access to education, and economic opportunities. By fostering a deeper understanding of these issues and striving for tangible change, we can work toward a future where the proud heritage of indigenous peoples is celebrated rather than overshadowed by the specter of indigence. Ultimately, we must recognize that the fight for justice and equity is ongoing and that we all have a part to play in shaping a more inclusive world.

Or we just keep building walls

0 notes

Text

27.12

As a located, embodied western thinker-creator-researcher

Collecting stones as crumbs or holograms of the earth and biosphere - metaphor for solid knowledge

Designing digital 'objects' as animate beings - the 'spirit' in these systems, machines and a experiences as well as in the hardware and materials used to drive and power them

Designing as bringing forth, becoming - best example of enactivism in practical terms

Documentary narrative as living storylines and songlines?

Finished Māori Philosophy. Annotation: Annotation #3: Stewart, G. (2020). Maori philosophy: Indigenous thinking from Aotearoa. Bloomsbury Publishing.

This introductory reader to indigenous Māori thinking, culture and worldviews is a 2020 short volume written by professor of Māori philosophy of education from Te Ara Poutama at AUT, Georgina Tuari Stewart. As a part of the Bloomsbury Introduction to World Philosophies series, the text is by no means extensive or exhaustive, but clearly outlines and neatly summarises some core aspects of contemporary Māori thinking with great personal, historical, and narrative examples illuminating and developing the concepts further. Stewart highlights the contemporary post-colonial context in which Te Ao Māori exists in Aotearoa New Zealand, and how this context and incommensurability between Māori and Pākeha worlds and thinking, frames a Māori philosophy informed by critical theory (?). The book makes explicit reference to the contradictions of a ‘Māori’ philosophy, especially given the historical fact that ‘Māori’ as a unified people only stemmed out of the post-colonial context of needing to unify in response to the arrival of Pākeha. Before the colonisation of Aotearoa, although sharing lineage from the first waka from the Pacific and overarching worldviews, Māori identified more with whakapapa, hapu and specific iwi connections. Stewart details an understanding of ‘Māori’ as a form of indigenous thinking and identity born out of a colonial context in order to strengthen the culture and survive (?). The text also makes a point that Māori worldviews and thinking is a living culture, originating in oral traditions, which makes a book written for general audiences in English, and using western paradigms and modes of analytical thought, a contradictory and ironic position. In addition to this post-colonial context, the author outlines the traditional holistic Māori cosmological vision, stemming from an animistic, interconnected view of humans and natural environments centred from the concept of ‘whakapapa’ (limitedly translated to ‘genealogy’ in English), as well as the more contemporary thinking of Kaupapa Māori research methods.

The text is written in a combination of theoretical, academic language in some sections, narrative and anecdotal in others, as well as framed within traditional Māori storytelling and explanatory approaches (?).

The relevance of this book to my practice is primarily in giving myself a more solid understanding of a non-dualist, holistic worldview from the global south - especially given that this worldview is from where I currently stand and have been born. It details a living example of a culture and philosophy which sits outside of the reductionist, and dualist western tradition, and one in which the world, people, animals, plants and other materials are viewed in an interconnected and mutually dependent way.

Christmas gift from Mim. Fish hook pounamu representing te Matau a Maui - Maui's fish hook - Hawkes bay, a reminder of this place, and a good luck charm, which I'll take forward on to the next challenge. Thinking about the aura of the Carver imbued into this piece and the pounamus aura as a material from the natural world and the 'experiences' this stone has been through.

0 notes

Text

Breaking Barriers and Building Bridges: The Māori Justice Movement in the Age of Social Media

As their name implies, peopleagainstprisonsaotearoa (PAPA) are a prison abolitionist group based in Aotearoa, advocating for incarcerated people and the end of prisons. The post which was posted to their Instagram account calls for people to sign its petition, which aims to implement all 12 recommendations of the Turuki! Turuki! Report into New Zealand’s current justice system. PAPA argues that the government should abandon its tough on crime rhetoric, and implement a preventative, restorative, and rehabilitative justice system that reflects the treaty of Waitangi.

New Zealand’s criminal justice system has long been a difficult terrain for Māori to navigate. Despite Māori being only approximately 15% of the New Zealand population, statistics show that they are overrepresented at every level in the criminal justice system. Māori represent 37% of people proceeded against by police, 45% of people convicted, and 52% of people in prison. PAPA, point to issues such as poverty and inequality, inadequate mental health support, poor educational outcomes, and other social issues as key drivers of crime in Aotearoa. According to PAPA, politicians are to blame for upholding the current criminal justice system that focuses on imprisoning people disproportionately affecting working-class, Māori, and ethnic minority communities.

Government inaction and lack of legislation to tackle these issues are underpinned by media representations of Māori. Abel (2016) argues that news media representations of Māori contribute to policymaking in relation to Māori and Treaty issues in New Zealand. News media is widely accepted as the primary source of people’s knowledge and attitudes, particularly regarding issues or groups of whom media audiences have little firsthand experience with (Abel, 2016). Research has shown that mainstream news media has often painted Māori in a bad light. News media on Māori, when included, frequently focuses on violence and crime. Negative portrayals of Māori in the media can perpetuate stereotypes and biases, further alienating Māori communities and reinforcing a sense of "otherness." This, in turn, affects the willingness of non-Māori citizens to engage in meaningful dialogue and act on issues related to criminal justice reform and indigenous rights. Pakeha in New Zealand represent 70% of the total population, a powerful majority of the voting electorate. Any government wanting to enact the type of policy and legislation that PAPA are fighting for, will need the support of the majority non-Māori population. Therefore, the attitudes and opinions of Pakeha and other non-Māori population are central to the policies any government will pursue (Abel, 2016). However, because mainstream news media has inadvertently fostered negative attitudes towards Māori, it is unlikely that any government will garner the type of support needed for such policy.

The Turuki! Turuki! report was released in 2019, calling for urgent transformative change to New Zealand’s justice system. The review was overseen by the Te Uepū Hāpai i te Ora – Safe and Effective Justice Advisory Group, under the leadership of Chester Borrows, a former National Party Minister for Courts comprised experts and advocates in the domains of Māori legal issues, healthcare, sociology, and criminology. The review was also informed by the community who offered their experiences, stories, and visions for a new system. Despite the extensive research that has gone into the review, 5 years on and successive governments have ignored its recommendations.

The prevalence of social media has challenged traditional ideas of how people participate in politics. People of marginalized groups who have historically felt left out of the political conversation are increasingly using social media platforms to amplify their voices and share their perspectives. Social media has proved a powerful avenue for bypassing traditional forms of media, who are often seen as the gatekeepers of objective knowledge. Citizens in numerous countries are progressively using specialized online platforms, mainstream social media, or blogs as channels to express their opinions, whether it is for advocacy, endorsement, or criticism of their elected officials, aiming to amplify their voices on the internet (Frame & Brachotte, 2015). In New Zealand, social media has played a crucial role in Māori political activism. Groups and individuals use platforms like Twitter and Instagram to advocate for indigenous rights, land rights, and social justice issues. It is important to highlight that there is still hope for achieving change through social media activism. Social media has become a powerful tool for grassroots movements, allowing marginalized communities to mobilize, gain visibility, and rally support for their causes. By leveraging the reach and influence of platforms like Instagram and Twitter, groups like PAPA and others can engage a wider audience, raise awareness, and build momentum for the transformative changes they seek in the criminal justice system.

0 notes

Text

Breaking Barriers and Building Bridges: The Māori Justice Movement in the Age of Social Media

As their name implies, peopleagainstprisonsaotearoa (PAPA) are a prison abolitionist group based in Aotearoa, advocating for incarcerated people and the end of prisons. The post which was posted to their Instagram account calls for people to sign its petition, which aims to implement all 12 recommendations of the Turuki! Turuki! Report into New Zealand’s current justice system. PAPA argues that the government should abandon its tough on crime rhetoric, and implement a preventative, restorative, and rehabilitative justice system that reflects the treaty of Waitangi.

New Zealand’s criminal justice system has long been a difficult terrain for Māori to navigate. Despite Māori being only approximately 15% of the New Zealand population, statistics show that they are overrepresented at every level in the criminal justice system. Māori represent 37% of people proceeded against by police, 45% of people convicted, and 52% of people in prison. PAPA, point to issues such as poverty and inequality, inadequate mental health support, poor educational outcomes, and other social issues as key drivers of crime in Aotearoa. According to PAPA, politicians are to blame for upholding the current criminal justice system that focuses on imprisoning people disproportionately affecting working-class, Māori, and ethnic minority communities.

Government inaction and lack of legislation to tackle these issues are underpinned by media representations of Māori. Abel (2016) argues that news media representations of Māori contribute to policymaking in relation to Māori and Treaty issues in New Zealand. News media is widely accepted as the primary source of people’s knowledge and attitudes, particularly regarding issues or groups of whom media audiences have little firsthand experience with (Abel, 2016). Research has shown that mainstream news media has often painted Māori in a bad light. News media on Māori, when included, frequently focuses on violence and crime. Negative portrayals of Māori in the media can perpetuate stereotypes and biases, further alienating Māori communities and reinforcing a sense of "otherness." This, in turn, affects the willingness of non-Māori citizens to engage in meaningful dialogue and act on issues related to criminal justice reform and indigenous rights. Pakeha in New Zealand represent 70% of the total population, a powerful majority of the voting electorate. Any government wanting to enact the type of policy and legislation that PAPA are fighting for, will need the support of the majority non-Māori population. Therefore, the attitudes and opinions of Pakeha and other non-Māori population are central to the policies any government will pursue (Abel, 2016). However, because mainstream news media has inadvertently fostered negative attitudes towards Māori, it is unlikely that any government will garner the type of support needed for such policy.

The Turuki! Turuki! report was released in 2019, calling for urgent transformative change to New Zealand’s justice system. The review was overseen by the Te Uepū Hāpai i te Ora – Safe and Effective Justice Advisory Group, under the leadership of Chester Borrows, a former National Party Minister for Courts comprised experts and advocates in the domains of Māori legal issues, healthcare, sociology, and criminology. The review was also informed by the community who offered their experiences, stories, and visions for a new system. Despite the extensive research that has gone into the review, 5 years on and successive governments have ignored its recommendations.

The prevalence of social media has challenged traditional ideas of how people participate in politics. People of marginalised groups who have historically felt left out of the political conversation are increasingly using social media platforms to amplify their voices and share their perspectives. Social media has proved a powerful avenue for bypassing traditional forms of media, who are often seen as the gatekeepers of objective knowledge. Citizens in numerous countries are progressively using specialised online platforms, mainstream social media, or blogs as channels to express their opinions, whether it is for advocacy, endorsement, or criticism of their elected officials, aiming to amplify their voices on the internet (Frame & Brachotte, 2015). In New Zealand, social media has played a crucial role in Māori political activism. Groups and individuals use platforms like Twitter and Instagram to advocate for indigenous rights, land rights, and social justice issues. It is important to highlight that there is still hope for achieving change through social media activism. Social media has become a powerful tool for grassroots movements, allowing marginalised communities to mobilise, gain visibility, and rally support for their causes. By leveraging the reach and influence of platforms like Instagram and Twitter, groups like PAPA and others can engage a wider audience, raise awareness, and build momentum for the transformative changes they seek in the criminal justice system.

0 notes

Text

Week 9 - Research

I've brainstormed the knowledge I've gained from reading about Kaupapa Māori on this poster that I've made. These insights strongly resonate with me regarding the ethics of working with others and being respectful as a creator. I'm eager to include these principles in my writing because they form the foundation of not just Māori culture but also align with many of my personal values.

Main notes:

Comes from Māori cultural frames to ensure safety and equality.

Kaupapa Māori principles are based on a whole cultural knowledge system. The Māori community shares the same beliefs and traditions that travel through generations and generations.

Born out of the need for research about Māori, to serve Māori communities. The principles are not just guidance but are the education foundation, customary practice, and values of Māori.

(Reading credits: Hoskins, T. K., & Jones, A. (2017). Critical conversations in Kaupapa Maori. Huia Publishers.)

Further research:

Leather & Hall (2004) state, "Mythology is more than just imaginative stories. Encoded within those stories were facts. If we can unlock the key to these stories, we can access the knowledge of our ancestors" (p.8).

This was a quote from an Maori astronomy book that I've read before and I think it aligns with my work that have used traditional Vietnamese and Asian mythology so I've decided to use it in my writings.

Book Reference:

Leather, K., & Hall, R. (2004). Tātai Arorangi, Māori Astronomy: Work of the Gods. Viking Sevenseas.

Artist research:

Ren Hang:

Ren Hang's relentless commitment to sharing their work is incredibly inspiring. They chose to self-publish their creations to circumvent state censorship, even in the face of police detention, numerous arrests, and exhibitions being banned. Hang's art represents an alternative perspective on humanity and identity that directly challenges state authority. Their work is a symbol of freedom, defiance, and intimate explorations of China's youth, delving into the intricacies of desire, identity, and society. As a creator, they motivate me to advocate for creative expression, maintain humility, and stand up for my beliefs.

Kenya Hara:

Kenya Hara's concept of "Emptiness." Hara (2010) claims that his renowned work "White" challenges the perception of white as a mere colour, delving into its more profound significance. This project explores 100 facets of white, including snow, Iceland, rice, and wax, underscoring white's importance in design as both a colour and a philosophy.

"When people share their thoughts, they commonly listen to each other's opinions rather than throwing information at each other. In other words, successful communication depends on how well we listen, rather than how well we push our views on the person seated before us". Hara's exploration of "Emptiness" delves into the depth of communication, highlighting the importance of genuine listening and understanding.

George Hajian's hard-working cover meaning:

"I tear, cut, fold, rip, and glue together printed images of the masculine performance," succinctly describes his analog artistry process, where he disassembles gendered language and imagery associated with "maleness."In doing so, he challenges conventional stereotypes related to "maleness," promoting a view of gender identity that is more fluid and multifaceted.

Through his compositions, he challenges stereotypes about "maleness" and emphasizes the diversity of gender identity. His project is a visually compelling narrative that underscores the power of craftsmanship in art and design.

0 notes

Text

just saw the movie uproar, new julien dennison. and Ohhh my lord.

it's about a boy called josh, who's half maori, in 1981 I THINK might have been 1984. irs about him finding his identity and finding who he is, and i fear i related to it jusr a little bit too much