#Masoretic Hebrew

Text

The Nature of God, Trinity Doctrine, and LDS Beliefs

Eric Johnson's claim that Latter-day Saint teachings lack evidence is easily refutable. Extensive scholarly research and ancient texts, combined with modern theological studies, offer a robust body of evidence supporting these teachings.

Members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints Are Christians: Here’s Why

Members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints Are Christians: Here’s WhyBiblical Definition of a ChristianMatthew 16:24-26Romans 12:1-3God Was Never a SinnerThe Concept of ‘Mormon Jesus’Jesus and Satan as Brothers: Historical ContextSatan as a Son of God: Biblical References in Job 1 and 2Symbols…

View On WordPress

#Anti-Mormon Rhetoric#Arianism#Bible#Christianity#Come Follow Me#Dead Sea Scrolls#Divine Council#Dr. Michael Heiser#Eric Johnson#faith#Gnostic Christianity#God#Godhead#Hebrew Idioms#Jesus#LDS Beliefs#Masoretes#Masoretic Text#mormonism research ministry#Nicene Creed#Sabellianism#Satan#Septuagint#Sons of God#Trinity#Valentinus#YHWH

0 notes

Text

What is the primary sacred text of Judaism?

There are 24 books Judaism claims as its holy writings. They are the five books which tell of the origin of the Israelites and discuss the laws their God gave to them, the Torah (law); eight books written by or about the prophets of ancient Israel, the Neviʾim (prophets); and eleven books which contain wisdom and miscellaneous aspects of Israelite history, the Ketuvim (writings). Altogether, these books comprise the Tanakh.

The Christian Old Testament as used by Protestants has the exact same content as the Tanakh, but arranges the constituent books differently and usually splits the books of Samuel, Kings, Chronicles, and Ezra-Nehemiah into two each, and the book of the minor prophets into twelve. Jews are generally uncomfortable with this name, as it implies that the Tanakh is complete without the New Testament, along with different misconceptions on how Christians have translated and presented the Tanakh, discussed below. For the rest of this FAQ, this set of books will be referred to as the Tanakh except in its capacity of a constituent part of the Christian Bible.

Non-Protestant Christians include a number of books written during the Second Temple era or later in their Old Testament canons. These books are collectively known as the Apocrypha or Deutercanon, and are outside the scope of this FAQ.

What language(s) was the Tanakh written in?

Almost the entire Tanakh was written in Hebrew, while parts of the Daniel and Ezra(-Nehemiah), along with words and phrases from throughout the Tanakh, were written in Aramaic.

Was Biblical Hebrew written with vowels?

The Tanakh was originally written in a writing system called the Paleo-Hebrew alphabet, found in the Dead Sea Scrolls and other very early examples of Hebrew writing, and retained by the Samaritans. During the time of the Second Temple, the Jews gradually adopted a script derived from the Imperial Aramaic script, and modified it to become the square script, which is now the more familiar "Hebrew script." Both were ultimately derived from the Phoenician alphabet, and operate on similar principles, to the point where there is essentially a one-to-one correspondence. They are both technically defined as abjads rather than proper alphabets, the reason being that they lack letters whose primary use is to express vowel sounds.

Why wasn't Biblical Hebrew written using a system that clearly marked vowels?

Hebrew is a member of a larger family called the Semitic languages, most of which do not have (or did not use to have) many distinct vowels. Arabic only has three, and there is no strong evidence that Akkadian had more than four. Aramaic, Ge'ez and Amharic all have at least five, and there is evidence that Ugaritic did as well, but the additional vowels in these languages do not converge the way they would if they had been inherited from a common ancestor.

At the beginning of its written history, a predecessor of Hebrew, either Proto-Northwest Semitic or an immediate descendant, likely had three vowel qualities /a i u/. Its writing system, the Proto-Sinaitic alphabet, accordingly lacked vowel letters, as a given consonant sequence would have been substantially less ambiguous than in other languages with larger vowel inventories.

In the stages between PNWS and Hebrew, and in Hebrew itself, a number of different sound changes caused its vowel inventory to expand, ultimately adding two, possibly three, more vowel sounds /e o (ǝ)/. As Hebrew developed, so did the variant of the Proto-Sinaitic script used to write it, albeit more slowly, giving rise to both the Paleo-Hebrew alphabet and the square script. As the written forms of a language are more conservative than their spoken forms, and the changes which brought about these additional vowels were very gradual, there was no impetus for any group of scholars to sit down and propose the addition of vowel letters to be used in writing Hebrew before it went extinct around the beginning of the fourth century.

That being said, four letters, alpeh א, waw ו, he ה, and yodh י, used ordinarily to express consonants /ʔ w~v h j/, took on a secondary role of expressing vowels in variant spellings. The letters aleph and he were used for essentially any vowels, waw for rounded vowels, and yod for front vowels. In this capacity, such a letter is called an ʾem qriʾa or mater lectionis.

How do we determine the pronunciation of Biblical Hebrew if it is extinct and did not have proper vowel letters?

Hebraicists rely on a number of different methods for determining the pronunciation of Biblical Hebrew words. Even though Hebrew went extinct, it was retained liturgically in Judaism, leading to three different vocalizations, the Tiberian, Babylonian, and Palestinian. During the high middle ages, a group of Jewish scholars called the Masoretes developed systems of vowel markings called the niqqud to clarify these vocalizations in Hebrew writing. Only the Tiberian vocalization survived the middle ages or was extensively covered by niqqud, and it is referenced when determining the pronunciation of Biblical Hebrew.

The matries lectionis produced variant spellings of certain words, which also clarifies the pronunciation.

In ancient times, a Greek translation of the Tanakh was produced called the Septuagint (abbreviated LXX). Its origins are shrouded in fable, but it is generally agreed by historians of the Bible that in the mid-third century BC, about seventy rabbis gathered in Alexandria and translated at least the Torah into Hebrew, with the rest of the Old Testament completed by the first century. As Greek is written in a proper alphabet, the vowels used in proper nouns and loanwords give insight into how these words would have been pronounced in Hebrew.

Around the middle of the third century AD, a critical edition of the Tanakh called the Hexapla was produced. Consisting of six columns, it placed the Hebrew text alongside an attempt to write the Hebrew text with the Greek alphabet (in the second column, this text is called the Secunda), and four different Greek translations. Though it exists in fragmentary condition, the Secunda gives some insights into the pronunciation of Hebrew.

Syllable timing can be predicted based on Biblical poetry.

Finally, as it is part of a larger language family, Hebrew can be compared with other Semitic languages that have been spoken constantly since antiquity. Special emphasis is put on comparison to its closest living relatives, Aramaic and Arabic.

What is the Tetragrammaton?

It is a name for God used well over 6000 times in the Tanakh, spelled using four Hebrew letters, יהוה.

Have any of the above methods been useful in determining the pronunciation of the Tetragrammaton?

Judaism developed a taboo against pronouncing the Tetragrammaton during the Second Temple Period. For this reason, except for one possible exception (and even that is doubtful), no LXX manuscript presents a genuine effort to transliterate the Tetragrammaton; the only remaining fragments of the Secunda which include sections featuring the Tetragrammaton replace it with the Hebrew form amidst the Greek letters; and Tiberian vocalization lacks a pronunciation for it. In addition, all four of its letters can be matries lectionis, and it lacks known cognates in other Semitic languages.

Samaritanism developed the taboo later, and a group of Jewish mystics that survived a century or so after the destruction of the Second Temple never had it. In the fourth century, Theodoret, in his Quaestiones in Exodum, records a Samaritan pronunciation of /i.a.ve/, consistent with Clement of Alexandria recording a mystic pronunciation of /i.a.we/ in the fifth book of his Stromata. Since /v/ and /w/ were never distinguished readily in any form of Hebrew, this points to a pronunciation /jah.weh/, hence the spelling Yahweh.

The name "Jehovah" was an earlier rendering of the name, produced from a misconception among Christian Hebraists when encountering the Tetragrammaton in Masoretic texts. To prevent anyone from even accidentally saying the name aloud, a practice arose of saying it with the vowels in the word for "Lord," אדוני adonai. Christian Hebraicists did not realize this was a hybrid word and thought it was God's actual name, producing /ja.ho.vah/, eventually Jehovah.

Is Lashawan Qadash as promoted by various Black Hebrew Israelite groups remotely authentic to the actual pronunciation of ancient Hebrew?

As with almost all other particular teachings of the BHIs, the Lashawan Qadash lacks any kind of historical evidence and is easily disproven.

For example, under LQ, the name of God is not "Elohim," but rather "Alahayam." However, the first element is cognate with Arabic إله /ʔi.laːh/ and is an element of a mile-long list of different theophoric names from the Tanakh, such as Elijah, Daniel, etc, consistently spelled ηλ /eːl/ in the LXX. This points to a front vowel, both long before Hebrew became a distinct language, and towards its extinction. The second vowel is confirmed by the spelling variant which includes a waw, indicating a rounded vowel. However, the BHIs who employ LQ do not use a variant "Alahawayam." The word itself is the plural of the word "eloah" (please note that verbs always indicate grammatical number in Hebrew, and that the actions of the God of Israel are described using singular verbs in the Tanakh) which has always had a letter waw. The same plural ending shows a consistency with vowels in Aramaic plural endings. The pronunciation of the entire word is consistent with the form ελωειμ as found in the Secunda for Psalm 72:18. Black Hebrew Israelitism is usually conspiratorial, and BHIs will suggest the pronunciations of Hebrew proposed through accepted methods of historical methods are actually some kind of wicked plot perpetrated by the Jesuits, Masoretes, adherents of Babylonian mystery religion, or some combination thereof, usually in cahoots with each other. Whatever shadowy force(s) which acted to produce the pronunciation "Elohim" would have had to alter every last Hebrew scroll and carving which contains the singular "eloah," waw in tow, and every last Septuagint and New Testament manuscript containing a theophoric name containing "El" to include the letter ēta, including those manuscripts which laid in dark caves and buried in the desert for centuries; every remaining Secunda fragment to spell the name as ελωειμ; convinced millions of Arabic speakers, men, women, and children, rich and poor, to say "ilah" and write accordingly; and convinced millioned of Aramaic speakers, men, women, and children, rich and poor, to use front vowels when saying nouns in the plural, and write accordingly, centuries before anyone seriously proposed that Arabic, Aramaic, and Hebrew were related languages. This is all that would have had to have been done just to deceive the whole world of the pronunciation of just one word. There are far more words which also present a host of problems under LQ.

The existing evidence suggests that LQ originated in 20th-century Harlem, without any historical precedent whatsoever, and does not belong in any serious discussion of Biblical Hebrew.

Why is it said that Hebrew "went extinct" when it has been in constant use by the Jews until the present day?

The term "extinction" in linguistics is used of languages without living native speakers. When the last native speaker of a language dies, that language is then extinct. Sumerian is extinct. Ancient Egyptian is extinct. Gaulish is extinct. Wampanoag is extinct. Ubykh is extinct. No informed person disputes any of these languages are actually extinct. However, many Jews and philosemites take offense at the term "extinction" when used to describe the ultimate fate of Biblical Hebrew.

The fact of the matter is that Assyria dispersed most of the tribes of Israel, and Babylon captured what was left. We do not know what happened to the 10 lost tribes, but the members of Judah and Levi began to speak Aramaic. Even after Cyrus the Great allowed the Jews to resettle Judaea, most Jews continued to speak Aramaic and teach it to their children. Through the Second Temple Era, Hebrew went from threatened to endangered. It did not matter that Hebrew was used in the synagogues; whether a language is alive or dead is determined at the cradle rather than the altar.

Bar Kochba attempted to reinvigorate Hebrew during his revolt around AD 130. After this revolt was suppressed by the Romans, any hope of Hebrew continuing were essentially dashed. The Mishnah, thought to have been among the final documents written in Hebrew during the lifetime of any native speakers, was completed around the turn of the third century, and was in a form that showed obvious changes one would expect of a language approaching extinction. There is not a shred of evidence that there were any native speakers more than a century after the Mishnah.

Extinct languages find use liturgically in different religious traditions throughout the world. No Jewish person or philosemite would deny, given sufficient information, that Avestan is extinct, despite its continuing use in Zoroastrianism. Nor would they deny the same about Coptic, Latin, Ge'ez, or Sanskrit, nor would they deny that Sumerian was in use by various pagan groups as long as 2000 years after it went extinct. Yet, for these same people, it is "inaccurate" or even "bigoted" to suggest the same regarding Hebrew. The knowledge of Hebrew during late antiquity and the middle ages was restricted almost exclusively to rabbis and Jewish literati, exactly 100% of whom spoke some other language natively. Yes, Hebrew was revived during the modern period, but it took great effort in creating enough vocabulary to describe the modern world, and there are enough difference between modern and Biblical Hebrew to motivate Avraham Ahuvya to create a modern Hebrew translation (for lack of a better term) of the Tanakh.

Simply put, if these people want to discuss historical linguistics, they need to use terms which are found in historical linguistics, as they are defined by historical linguistics, terms which specialists in the field, Jew and gentile, accepted a long time ago. This includes the term “extinction.”

Why don't Christians use Hebrew source texts when translating the Tanakh?

They do, and have been doing so constantly since the Reformation.

The printed Hebrew edition of the Tanakh, by Daniel Bomberg, was arranged from several Masoretic manuscripts collected and collated by Jacob ben Hayyim. This was the primary base text of the Old Testament in all Protestant English translations of the Bible from at least the Geneva Bible (first published 1557) up until at least the Revised Version (published 1885), and seemingly the Darby Bible of 1890 and American Standard Version of 1901. Only Catholic Bibles used the Vulgate as a source, and an obscure translation of the LXX by Charles Thompson was printed in 1808; this translation made its source clear on the title page, not that almost anyone paid attention to it.

A scholar of the Tanakh named Rudolph Kittel collated an even greater set of Masoretic manuscripts, creating the Biblia Hebraica Kittel (BHK), first published 1906. Later, it was determined that a manuscript, which had been produced in Cairo, mysteriously ended in the possession of a Russian Jewish collector named Abraham Firkovich, was displayed in Odessa, and then later in St. Petersburg (later Leningrad) was in fact the oldest complete copy of the Tanakh in Hebrew. It is now known as the Westminster-Leningrad Codex, and was made the primary source of printings of the BHK from 1937 onward, and by extension the OT of the Revised Standard Version. It later became the primary basis of the Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia (BHS), first published 1968, and by extension the OT in the New American Standard Bible, New International Version, Good News Bible, New RSV, New KJV, Contemporary English Version, World English Bible, English Standard Version, and New Living Translation, just to name a few. Another printed edition of the Old Testament in Hebrew, the Biblia Hebraica Quinta, was completed last year, also derived from the WLC, and there is no reason to believe it will not serve as the basis of future translations.

The LXX, Targumim, Dead Sea Scrolls, and Samaritan Pentateuch are occasionally consulted, mostly to illuminate the meaning of obscure Hebrew words or phrases, or solve inconsistencies among Masoretic manuscripts. The translators invariably place conspicuous footnotes to indicate such. If you do not believe Jewish translators of the Tanakh do the same thing, you need to explain how “amber” appears three separate times in the book of Ezekiel (1:4, 1:27, and 8:2) in the JPS Tanakh, in exactly the same places as it appears in Christian translations, despite the mystery which would surround the meaning of the base word, חשמל apart from the LXX.

#Hebrew#Hebrew language#Hebraicist#Hebraicists#Hebrew studies#Tetragrammaton#Language death#Tanakh#Old Testament#Seputagint#LXX#Dead Sea Scrolls#DSS#Targum#Targumim#Masoretes#Masoretic#Textual criticism#History of the Bible

0 notes

Text

Watching a debate between a Jewish and Christian scholar is fascinating, because there is as stark difference in how the Christian and Jewish person will conduct themselves when they stand at the podium. Obviously, there is a sense of professionalism, but there will also be a manner of articulating your points and arguments from boths sdies.

The Jewish scholar tends to be academical and often refer to sources to debuke any Christological and ecclesial supposition about the Tanakh/OT, whereas the Christian often appeals to emotion and will speak in a charismatic way to reinforce his belief in Christ rather than to substantiate their argument. The other issue I find with the Christian debater is that they attempt to substantiate their belief through the New Testament, a scripture which holds no weight to a Jewish person; it is as useful as a brick.

The challenge in debating a Jewish scholar is the fact that a Jewish scholar studies Hebrew and Aramaic and are often fluent in respective language, thus possessing an advantage in textual and hermeneutical analysis of the Masoretic text, whereas a Christian often make use of an already translated Bible, which has been prone to corruption, distortion and christological alterations throughout centuries.

548 notes

·

View notes

Note

my understanding of the apocrypha were most were recognized as canon by the Roman Catholic Church and other Orthodox Churches but as I'm trying to find more information online I'm getting more confused about what's considered canon by who (mostly the Roman Catholic Church as that is what I was raised in) do you have resources that clearly explain and/or list which denominations recognize which apocrypha?

So there’s a distinction to be made between what we on the show call capital-A Apocrypha and lower case-a apocrypha.

The capital-A type is also known as the Deuterocanon, and it represents the various late-era books that are present in the Greek translation of the Hebrew Scriptures called the Septuagint, but which are *not* included in the authoritative Hebrew text of the Bible known as the Masoretic text. (NB: the Septuagint is many centuries older than the Masoretic text.)

When Martin Luther translated the Bible into German, he separated these texts and put them at the end as being worthy of study but not as authoritative as the other material. Later American English editions of the Bible would subsequently cut the Apocrypha/Deuterocanon altogether to save on printing costs. So if you grew up in a Protestant church and don’t know what Bel and the Dragon is, that’s why.

These books include Tobit, Judith, and 1 and 2 Maccabees, among about a dozen others. You will find these in pretty much any Catholic Bible.

In addition, the Eastern Orthodox Church accepts a small handful more, including 3 and 4 Maccabees, 1 and 2 Esdras, and a bonus Psalm. If you buy a copy of a study version of the NRSV such as a NOAB or the new SBL study Bible, you should find that it contains all of the Deuterocanon of both the Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches.

Where things start to get broader is in some of the Oriental Orthodox churches, most notably the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church, which has over 80 books in its broader canon (numbers differ), including Jubilees and 1 Enoch.

Where the confusion comes, I think, is from the fact that the word apocrypha is also used to refer to works that were never part of any official canon despite their popularity and influence. Elements of these books have come into Catholic belief through tradition, however, even though they have never been official scripture. The Infancy Gospel of James is a major example of a book that has never been canon but which nevertheless has had an outsize influence on Catholic teaching.

Wikipedia has a chart that you may or may not find useful depicting which books are canon where

A short rule of thumb is this: the only Apocrypha considered canon by any church is Jewish in origin. There is no New Testament apocrypha held as canon by any major church

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shavuot is about collective revelation so I wanted to celebrate with artistic collaboration! This one was made with Rabbi Evan Schultz. You can find more of his poetry here: barefootrabbi.wordpress.com

Thank you for supporting my work!

Patreon.com/kimchicuddles

Text reads: the hebrew word

for tradition,

masoret מסורת,

has not one,

but two,

hebrew roots.

the root

alef-samech-resh

means

to bind

to tie up

to imprison.

and the root

mem-samech-resh

means

to pass down

to transfer

to deliver.

so please understand

part of who i am was

chosen for me

and part each day

i choose to be.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Goliath (/ɡəˈlaɪəθ/ gə-LY-əth)[a] is a Philistine warrior in the Book of Samuel. Descriptions of Goliath's immense stature vary among biblical sources, with the Masoretic Text describing him as 9 feet 9 inches (2.97 m) tall. Goliath issued a challenge to the Israelites, daring them to send forth a champion to engage him in single combat; he was ultimately defeated by the young shepherd David, employing a sling and stone as a weapon. The narrative signified King Saul's unfitness to rule, as Saul himself should have fought for Israel.

Modern scholars believe that the original slayer of Goliath may have been Elhanan, son of Jair, who features in 2 Samuel 21:19, in which Elhanan kills Goliath the Gittite, and that the authors of the Deuteronomic history changed the original text to credit the victory to the more famous character David.

The phrase "David and Goliath" has taken on a more popular meaning denoting an underdog situation, a contest wherein a smaller, weaker opponent faces a much bigger, stronger adversary

Goliath's name

Tell es-Safi, the biblical Gath and traditional home of Goliath, has been the subject of extensive excavations by Israel's Bar-Ilan University. The archaeologists have established that this was one of the largest of the Philistine cities until destroyed in the ninth century BC, an event from which it never recovered. The Tell es-Safi inscription, a potsherd discovered at the site, and reliably dated to between the tenth to mid-ninth centuries BC, is inscribed with the two names ʾLWT and WLT. While the names are not directly connected with the biblical Goliath (גלית, GLYT), they are etymologically related and demonstrate that the name fits with the context of the late tenth- to early ninth-century BC Philistine culture. The name "Goliath" itself is non-Semitic and has been linked with the Lydian king Alyattes, which also fits the Philistine context of the biblical Goliath story. A similar name, Uliat, is also attested in Carian inscriptions. Aren Maeir, director of the excavation, comments: "Here we have very nice evidence [that] the name Goliath appearing in the Bible in the context of the story of David and Goliath… is not some later literary creation."

Based on the southwest Anatolian onomastic considerations, Roger D. Woodard proposed *Walwatta as a reconstruction of the form ancestral to both Hebrew Goliath and Lydian Alyattes. In this case, the original meaning of Goliath's name would be "Lion-man," thus placing him within the realm of Indo-European warrior-beast mythology.

The Babylonian Talmud explains the name "Goliath, son of Gath" through a reference to his mother's promiscuity, based on the Aramaic גַּת (gat, winepress), as everyone threshed his mother like people do to grapes in a winepress (Sotah, 42b).

The name sometimes appears in English as Goliah

Elhanan, son of Jaare-Oregim the Bethlehemite (Hebrew: אֶלְחָנָן בֶּן־יַעְרֵי אֹרְגִים בֵּית הַלַּחְמִי ʾElḥānān ben-Yaʿrē ʾŌrəgīm Bēṯ halLaḥmī) is a character in 2 Samuel 21:19, where he is credited with killing Goliath:

"There was another battle with the Philistines at Gob, and Elhanan son of Jaare-oregim the Bethlehemite killed Goliath the Gittite, the shaft of whose spear was like a weaver's beam."[1]

In 1 Chronicles 20:5, he is called Elhanan son of Jair (אֶלְחָנָן בֶּן־יָעִיר ʾElḥānān ben-Yāʿīr), indicating that Jaare-oregim is a garbled corruption of the name Jair and the word for "beam" used in the verse (ʾōrəgīm). The passage in 2 Samuel 21:19 poses difficulties when compared with the story of David and Goliath in 1 Samuel 17, leading scholars to conclude "that the attribution of Goliath's slaying to David may not be original," but rather "an elaboration and reworking of" an earlier Elhanan story, "attributing the victory to the better-known David.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Unicorns of the Bible

Job 39:9 (KJV) "Will the unicorn be willing to serve thee, or abide by thy crib?"

Job 39:10 (KJV) "Canst thou bind the unicorn with his band in the furrow? or will he harrow the valleys after thee?"

Psalm 92:10 (KJV) "But my horn shalt though exalt like the horn of an unicorn: I shall be anointed with fresh oil."

Deuteronomy 33:17 (KJV) "His glory is like the firstling of his bullock, and his horns are like the horns of unicorns: with them he shall push the people together to the ends of the earth: and they are the ten thousands of Ephraim, and they are the thousands of Manasseh."

Numbers 23:22 (KJV) “God brought them out of Egypt; he hath as it were the strength of an unicorn.”

Numbers 24:8 (KJV) “God brought him forth out of Egypt; he hath as it were the strength of an unicorn: he shall eat up the nations his enemies, and shall break their bones, and pierce them through with his arrows.”

Isaiah 34:7 (KJV) "And the unicorns shall come down with them, and the bullocks with the bulls; and their land shall be soaked with blood, and their dust made fat with fatness."

Psalm 29:6 (KJV) "He maketh them also to skip like a calf; Lebanon and Sirion like a young unicorn."

Note: When considering the most popular English translations of the Christian Bible - including the Hebrew texts, of which all of these verses originate- the King James Version (KJV) is considered to be one of the least accurate to the original language, despite using the Masoretic Hebrew as the reference text, which is used as the authorative Hebrew. No other popular translations use "unicorns." Instead, the reader will usually see "wild ox."

[I'm a seminarian who has several semesters of Biblical Greek and Hebrew]

#good omens#hermeneutics#gomens#noah's ark#unicorns#unicorns of the Bible#crowley#good omens season 1#gomens 1#gomens season 1#good omens 1#neil gaiman#bible#unicorn#oy shem

20 notes

·

View notes

Note

I like to imagine some spn scenarios on my head and one of those is a daughter or some kind of being connected to Amara having powers from darkness, kinda like archangels and angels have powers whose are fractions from Chuck.

The concept of Amara is so interesting that i wished to ser more of her.

I always try to reblog the Amara meta I find. She is so special to me.

It's here nor there, but you might be interested in theorizing on who the LITTLE GIRL was in The Garden in Destiny's Child s15.

My friend @13x02 and I did some rather incoherent Hokmah musings over here. “The one who finds me, finds life.”

The word'dmnon is central to an understanding of the poem, because it describes Hokmah's relationship to Yahweh. By use of the preposition 'esel, translated "beside," this word provides the key link between Yahweh and Hoknrah.

First we have Yahweh creating the universe, while Hoknrah, a little girl, plays at his side. Unfortunately, the word'dmon remains indecipherable cipherable in the Masoretic 'Iext.14 Some of the Rabbis and the Septuagint read'dnron as "master architect" or "builder." Other traditions translate it "nursling" or "child."''

This wide disparity of early traditions suggests that by the first centuries of the Common Era, readers already had lost the meaning. Interpreting the word as "nursling" or "little child" seems the best option. Language of birth and playing infer the presence of a child. In these verses Hokmah is born. She delights and plays. A "little child" does such things. In Proverbs 8, 1lokmah does not create or design the universe (although she does build a house with pillars), and so "master architect" would seem out of place."

The term remains ambiguous, and this adds to Hokmah's mystery and independence.'' This interpretive knot, the intractability of the word'innon, is perhaps a key feature of the text. It creates ates an open symbol that different communities fill in different ways.

In Proverbs 8, is not an emanation of God, but rather Yahweh's weh's daughter. The writing is mythological and not hypostatic.

David Penchansky. Twilight of the Gods: Polytheism in the Hebrew Bible (Kindle Locations 685-686). Kindle Edition.

#asks#you can usually count on me to have things to say about#weird things precious few care about#mysticism#polytheism

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Part III

It is true, that before the Masoretic points were invented (which was after the beginning of the Christian era), the pronunciation of a word in the Hebrew language could not be known from the characters in which it was written. It was, therefore, possible for that of the name of the Deity to have been forgotten and lost. It is certain that its true pronunciation is not that represented by the word Jehovah; and therefore that that is not the true name of Deity, nor the Ineffable Word.

Morals and Dogma - 13th Degree

Royal Arch of Solomon

#freemasonry#freemasons#Albert Pike#masonic lodge#illustration#masons#masonic temple#Masonic Education#symbolism#esoteric#art#morals and dogma#occult#hermetic

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

i think the hoshen (the breastplate) could be a good inspiration for modern fashion. big colorful gems on your chest. use it for divination. anyway. apparently the hoshen is the origin of the concept of birthstones!

The first-century historian Josephus believed there was a connection between the twelve stones in Aaron's breastplate (signifying the tribes of Israel, as described in the Book of Exodus), the twelve months of the year, and the twelve signs of the zodiac.

In the eighth and ninth centuries, religious treatises associating a particular stone with an apostle were written so that "their name would be inscribed on the Foundation Stones, and his virtue."[3]: 299 Practice became to keep twelve stones and wear one a month.[3]: 298 The custom of wearing a single birthstone is only a few centuries old, though modern authorities differ on dates. Kunz places the custom in eighteenth-century Poland, while the Gemological Institute of America starts it in Germany in the 1560s.[3]: 293

nobody knows what the gems really were though

Unfortunately, the meanings of the Hebrew names for the minerals, given by the masoretic text, are not clear,[9] and though the Greek names for them in the Septuagint are more clear, some scholars believe that they cannot be completely relied on for this matter because the breastplate had gone out of use by the time the Septuagint was created, and several Greek names for various gems have changed meaning between the classical era and modern times.[9] However, although classical rabbinical literature argues that the names were inscribed using a Shamir worm because neither chisels nor paint nor ink were allowed to mark them out,[11][12] a more naturalistic approach suggests that the jewels must have had comparatively low hardness in order to be engraved upon, and therefore this gives an additional clue to the identity of the minerals.[2]

theres a bunch of stuff in the wiki article talking about what the gems could have been

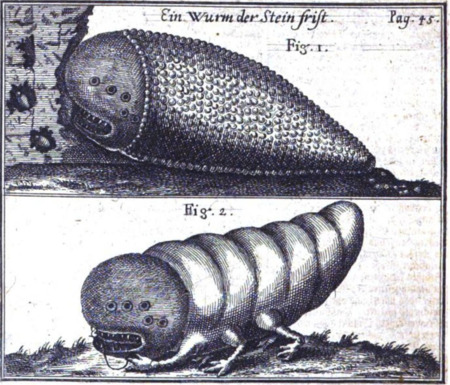

According to a rabbinic tradition, the names of the twelve tribes were engraved upon the stones with what is called in Hebrew: שמיר = shamir, which, according to Rashi, was a small, rare creature which could cut through the toughest surfaces,

In the Gemara, the shamir (Hebrew: שָׁמִיר šāmīr) is a worm or a substance that had the power to cut through or disintegrate stone, iron and diamond. King Solomon is said to have used it in the building of the First Temple in Jerusalem in the place of cutting tools. For the building of the Temple, which promoted peace, it was inappropriate to use tools that could also cause war and bloodshed.[2]

Referenced throughout the Talmud and the Midrashim, the Shamir was reputed to have existed in the time of Moses, as one of the ten wonders created on the eve of the first Sabbath, just before YHWH finished creation.[3] Moses reputedly used the Shamir to engrave the Hoshen (Priestly breastplate) stones that were inserted into the breastplate.[4] King Solomon, aware of the existence of the Shamir, but unaware of its location, commissioned a search that turned up a "grain of Shamir the size of a barley-corn".

Solomon's artisans reputedly used the Shamir in the construction of Solomon's Temple. The material to be worked, whether stone, wood or metal, was affected by being "shown to the Shamir." Following this line of logic (anything that can be 'shown' something must have eyes to see), early Rabbinical scholars described the Shamir almost as a living being. Other early sources, however, describe it as a green stone. For storage, the Shamir was meant to have been always wrapped in wool and stored in a container made of lead; any other vessel would burst and disintegrate under the Shamir's gaze. The Shamir was said to have been either lost or had lost its potency (along with the "dripping of the honeycomb") by the time of the destruction of the First Temple[5] at the hands of Nebuchadnezzar in 586 B.C.

20 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A Light For All People

1 The people that walked in darkness Have seen a great light;

They that dwelt in the land of the shadow of death,

Upon them hath the light shined.

2 Thou hast multiplied the nation,

Thou hast increased their joy;

They joy before Thee according to the joy in harvest,

As men rejoice when they divide the spoil.

3 For the yoke of his burden,

And the staff of his shoulder, The rod of his oppressor,

Thou hast broken as in the day of Midian.

4 For every boot stamped with fierceness,

And every cloak rolled in blood,

Shall even be for burning, for fuel of fire.

5 For a child is born unto us,

A son is given unto us;

And the government is upon his shoulder;

And his name is called

Pele-joez-el-gibbor-Abi-ad-sar-shalom;

6 That the government may be increased, And of peace there be no end,

Upon the throne of David, and upon his kingdom,

To establish it, and to uphold it

Through justice and through righteousness From henceforth even for ever.

The zeal of the LORD of hosts doth perform this.

7 The Lord sent a word into Jacob,

And it hath lighted upon Israel.

— Isaiah 9:1-7 | JPS Tanakh 1917 (JPST)

The Holy Scriptures according to the Masoretic text; Jewish Publication Society 1917.

Cross References: Judges 7:25; Judges 8:10; 1 Samuel 30:16; Job 12:23; Psalm 46:9; Psalm 72:3; Matthew 1:1; Matthew 1:23; Matthew 4:15-16; Luke 1:32; Luke 1:79; Luke 2:32; Luke 24:27; Hebrews 7:24

#prophecy#Jesus' birth#throne of David#justice#righteousness#Isaiah 9:1-7#Book of Isaiah#Old Testament#JPST#JPS Tanakh 1917#The Holy Scriptures according to the Masoretic text#jewish publication society 1917

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

I feel like the Catholics losing their shit over vernacular bible translations would have been slightly more defensible if they were reading it in the original Hebrew and Greek instead of Latin. Honestly even if they were just reading the Greek? The Septuagint obviously isn't the original language or even the same textual tradition as the Masoretic Text but it was what all the early Christians were reading and quoting from...

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Who is Jesus of Nazareth?

A Devotional Study of the Gospel of Mark

Mark 4:30-32 — Nothing Like It

By xapitos. All rights reserved. 2023.

Introduction

This study of the Gospel of Mark from the Christian Scriptures follows the premise to take a book at face value. This is a common practice for books. Thus, this study will look at the historical, cultural, archaeological and grammatical context of Mark’s Gospel to see if it truly is what it claims to be, namely the words of the God of the Hebrews, without any errors and final in authority to all that it speaks, claiming that Jesus of Nazareth is the Christ, the Messiah of Israel, who shall deliver his people, and the world of mankind from our rebelliousness against the holy LORD of Israel, King of the universe. If errors are discovered, then the Gospel of Mark will be assumed to be false. Until such a discovery, the book is accepted at face value.

I translate the Gospel of Mark from its Greek manuscripts and follow the paragraph divisions of The Greek New Testament, Third edition by the United Bible Societies. Thus, my Scripture reading may vary from yours here and there in small details. The Hebrew Scripture references are from the Masoretic Text of the Hebrew Scriptures in the Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia edition of the Masoretic Text. The Masoretic Text was copied by Hebrew scribes about 1000 A.D. and has been substantiated by various Hebrew manuscripts, the Dead Sea Scrolls, and the Septuagint (dated third to second centuries B.C.), which is the Greek translation of the Hebrew Scriptures. The English version of the Holy Bible used in this study is the New International Version, known as the NIV.

It is necessary to say a word about the translation of the Greek text. I intentionally translate the Greek as it is written, not smoothing out the English translation, as is done in English Bibles based on the original biblical languages of Hebrew, Aramaic, and Koine Greek. At times, the translation will come across awkward, wooden, and repetitive in English. Translating from one language to another can appear this way. Another involved factor is that it is obvious that God wrote the New Testament the way he did to emphasize what he wanted to emphasize through the Greek grammar and sentence structure. Without translating this way, such divine emphases might be missed by the English.

It is interesting to note, to me at least, that Mark continues to use the conjunction “and,” at the beginning of almost every clause. Some might call this poor grammar. I call it a “child’s heart.” Remember when your children were (or are) young and when they became excited, they just talked and talked, almost without breathing? This is what Mark’s continual use of “and” shows me. He is so excited about Jesus and his story, that it appears that he cannot wait to tell us everything he learned from the apostle Peter (Simon) about Jesus. May each of us have such a child’s heart.

Study

Mark 4:30-32 (30) And he was saying, “How shall it be likened the kingdom of God, or with what parable shall we describe it? (31) Like a mustard seed, which when it is planted in the earth, the smallest of all the seeds which are in the earth, (32) and when it grows, it ascends and becomes the greatest of all of the garden herbs and makes a shadow great, so that to be able under the shadow of it the birds of heaven dwell.

(30) And he was saying, “How shall it be likened the kingdom of God, or with what parable shall we describe it? This is the fourth parable Jesus speaks to describe the Kingdom. The Kingdom is so important to the Messiah and to God that they take four short parables in a row to describe it. Whenever the Lord repeats something in the Bible, it is done for emphasis to the listener/reader. In other words, the Kingdom of God is God’s emphasis to us. Pay attention! This is of eternal importance for your eternity and mine.

(31) Like a mustard seed, which when it is planted in the earth, the smallest of all the seeds which are in the earth, (32) and when it grows, it ascends and becomes the greatest of all of the garden herbs and makes a shadow great, so that to be able under the shadow of it the birds of heaven dwell. Jesus picks the smallest of the garden seeds used in his day. Some try to use this passage to show that Jesus made a mistake and was ignorant. Not so. The context is always the guide to understanding Scripture. The context here is gardening (not flower gardens) for the purpose of growing food. This is the fourth agrarian related parable describing the Kingdom of God. It is not a study about the smallest seed on the planet. Secondly, it was common proverbial speech in Jesus’ day, and before his day, to use the mustard seed as a figure of speech to describe something small. This usage appears in the Mishnah and the Talmud (Jewish writings and interpretations of the Hebrew Scriptures). Thus, our parable in question has a clearly cultural form of interpretation that dated to before the time of Jesus (Biblical Historical Context, “The smallest of all the seeds” biblicalhistoricalcontext.com/hermeneutics/the-smallest-of-all-the-seeds/). Thirdly, those who say that Jesus made a mistake by saying that the mustard seed is the smallest of all seeds have not taken into account the possibility (a very plausible one) that the seeds in existence now are different than the seeds of his time. In other words, macro-evolution (Answers in Genesis, “Are Mustard Seeds the Smallest or Was Jesus Wrong?, by Harry F. Sanders III, August 4, 2018, answering genesis.org/bible-questions/are-mustard-seed-the-smallest-or-was-Jesus-wrong/). Thus, there is the contextual explanation of the agrarian context and the proverbial context, with which Jesus and his contemporaries were very familiar, as well as the very possible macro-evolutionary context, that we are more familiar with, and lastly, parables are a form of communicating a literal idea. They use figures of speech and cannot be forced to be literal in every point. The main idea of any parable is the literal point being communicated. Just ask a poet.

The conclusion is that Jesus’ parable is safe and accurate to which he was speaking, namely the Kingdom of God, and neither crumbles by a modern, scientific interpretation from our time being forced upon this passage.

(32) and when it grows, it ascends and becomes the greatest of all of the garden herbs and makes a great shadow, so that to be able under the shadow of it the birds of heaven dwell. Verse 32 gives us the main idea of this parable: the Kingdom of God is large enough for all to live in and enjoy its place of rest, structure and existence. As a large mustard tree casts a big shadow that all the types of birds can enjoy and in which they find shelter from the sun, rain, wind and storms, so the Kingdom of God is large enough for all humans, male and female, black, yellow, white, brown, to enjoy and live in.

Self-reflection

How are you communicating about the kIngdom of God to others in your life?

Are you living out the Kingdom of God in the way that this parable communicates, namely, to cast a very large Kingdom of God shadow, in which any human can find spiritual rest, peace, safety, and well-being?

What can you do to improve in yourself the above concepts and the Kingdom of God lifestyle reflected in your answers?

7 notes

·

View notes

Note

are you aware that king james was a freemason? (Lodge Scoon and Perth No. 3, Perth, Scotland). so were most of the translators of his bible. this is no secret. english and scottish masons swear their oath on the KJV

I'm aware of king James being one yes. As far as the translators I haven't been able to find as such but to be honest, it doesn't matter. God will work his ways through who he chooses. James only commissioned the bible to be made, and the teams didn't "create" a new translation, they built off of the bibles before hand that came from the Hebrew Masoretic texts and Byzantine texts. People back then actually knew, studied, and cherished their bibles. So even if the KJV came out full of apostasy, the reformers would have known it and gone back to the Geneva Bible and the KJV would have been a dead fish on the shore. So if someone wants to pull the freemason card as a reason not to read the kjv, by all means go to the Geneva Bible, you will get nearly the same words.

As far as Mason and their bibles. They have four in their lodges. The Christian Bible, Koran, Hebrew, and another I can't remember the name of off my head. In Albert Pike, and others own writings they state that the Bible is just furniture. That depending on what religion the person is that is joining, they will swear on that Bible. A Muslim won't swear on the kjv, he will swear on the Koran. This is all a ruse for the initiate anyways because ultimately they will unknowingly be praying to lucifer. Now, however, when a person goes from freemasonry into the Shriners, they will swear oath on the Koran, regardless of their religion. This just digs the whole deeper for a "christian". Christians can not be masons, and still be a Christian. Everyone else it doesn't matter, they do not believe in Jesus as the Son of God anyways. There soul is damned right there. All the idol worship, oaths, and prayers to the gaotu is just fuel to their fire.

None of us are perfect, not one. And if God worked his ways through perfect people only, this world would be far more gone than it is.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Bible Attributes the Hidden Name of God to Greece

Eli kittim

The Greek New Testament Unlocks the Meaning of God’s Name

The meaning of God’s name (YHVH) was originally incoherent and indecipherable until the appearance of the Greek New Testament. In Isaiah 46:11, God says that he will call the Messiah “from a distant country” (cf. Matt. 28:18; 1 Cor. 15:24-25). Similarly, in Matt. 21:43, Jesus promised that the kingdom of God will be taken away from the Jews and given to another nation. That’s why Isaiah 61:9 says that the Gentiles will be the blessed posterity of God (through the messianic seed). Paul also says categorically and unequivocally, “It is not the children of the flesh [the Jews] … but the children of the promise [who] are regarded as descendants [of Israel]” (Rom. 9:6-8).

These passages demonstrate why the New Testament was not written in Hebrew but in Greek. In fact, most of the New Testament books were composed in Greece. The New Testament was written exclusively in Greek, and most of the epistles address Greek communities. Not to mention that the New Testament authors used the Greek Old Testament as their Inspired text and copied extensively from it. That’s also why Christ attributed the divine I AM to the Greek language (alpha and omega). Now why did all this happen? Was it a mere coincidence or an accident, or is it because God’s name is somehow associated with Greece? Let’s explore this question further.

YHVH (I AM)

Initially, God did not disclose the meaning of his name to Moses (Exod. 3:14), but only the status of his ontological being: “I Am.” The four-letter Hebrew theonym יהוה (transliterated as YHVH) is the name of God in the Hebrew Bible, and it’s pronounced as yahva. In Judaism, this name is forbidden from being vocalized or even pronounced.

Hebrew was a consonantal language. Vowels and cantillation marks were devised much later by the Masoretes between the 7th and 10th centuries AD. Thus, to call the divine name Yahva is a rough approximation. We really don’t know how to properly pronounce the name or what it actually means. But, through linguistic and biblical research, we can propose a scholarly hypothesis.

God Explicitly Identifies Himself with the Language of the Greeks

Since God’s name (the divine “I AM”) was revealed in the New Testament vis-à-vis the first and last letters of the Greek writing system (“I am Alpha and Omega, the beginning and the end” Rev. 22:13), then it necessarily must reflect a Greek name. The letters Alpha and Omega constitute “the beginning and the end” of the Greek alphabet. Put differently, the creator of the universe (Heb. 1:2) explicitly identifies himself with the language of the Greeks! That explains why the New Testament was written in Greek rather than Hebrew. That’s also why we are told “how God First concerned Himself about taking from among the Gentiles a people for his name” (Acts 15:14):

“And with this the words of the Prophets agree, just as it is written, … ‘THE GENTILES WHO ARE CALLED BY MY NAME’ “ (Acts 15:15-17).

This is a groundbreaking statement because it demonstrates that God’s name is not derived from Hebraic but rather Gentile sources. The Hebrew Bible asserts the exact same thing:

“All the Gentiles… are called by My name” (Amos 9:12).

The New Testament clearly tells us that God identifies himself with the language of the Greeks: “ ‘I am the Alpha and the Omega,’ says the Lord God” (Rev. 1:8). In the following verse, John is “on the [Greek] island called Patmos BECAUSE of the word of God and the testimony of Jesus” (Rev. 1:9 italics mine). We thus begin to realize why the New Testament was written exclusively in Greek, namely, to reflect the Greek God: τοῦ μεγάλου θεοῦ καὶ σωτῆρος ἡμῶν ⸂Ἰησοῦ Χριστοῦ⸃ (Titus 2:13)! Incidentally, God is never once called Yahva in the Greek New Testament. Rather, he is called Lord (kurios). Similarly, Jesus is never once called Yeshua. He is called Ἰησοῦς, a name which both Cyril of Jerusalem (catechetical lectures 10.13) and Clement of Alexandria (Paedagogus, Book 3) considered to be derived from Greek sources.

Yahva: Semantic and Phonetic Implications

If my hypothesis is accurate, we must find evidence of a Greek linguistic element within the Hebrew name of God (i.e. Yahva) as it was originally revealed to Moses in Exod. 3:14. Indeed, we do! In the Hebrew language, the term “Yahvan” represents the Greeks (Josephus Antiquities I, 6). Therefore, it is not difficult to see how the phonetic and grammatical mystery of the Tetragrammaton (YHVH, commonly pronounced as Yahva) is related to the Hebrew term Yahvan, which refers to the Greeks. In fact, the Hebrew names for both God and Greece (Yahva/Yahvan) are virtually indistinguishable from one another, both grammatically and phonetically! The only difference is in the Nun Sophit (Final Nun), which stands for "Son of" (Hebrew ben). Thus, the Tetragrammaton plus the Final Nun (Yahva + n) can be interpreted as “Son of God.” This would explain why strict injunctions were given that the theonym must remain untranslatable under the consonantal name of God (YV). The Divine Name can only be deciphered with the addition of vowels, which not only point to “YahVan,” the Hebrew name for Greece, but also anticipate the arrival of the Greek New Testament!

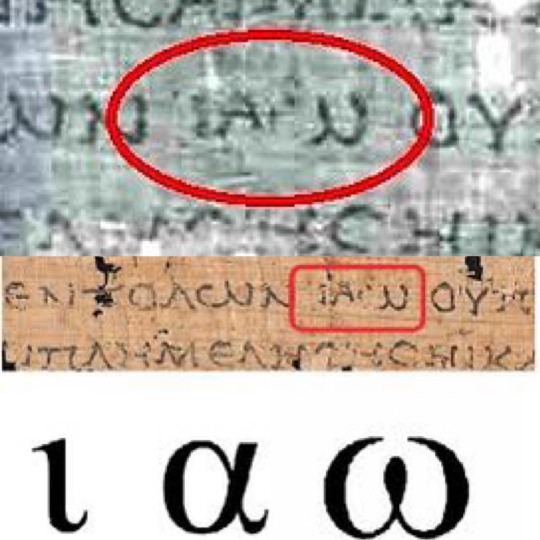

There’s further evidence for a connection between the Greek and Hebrew names of God in the Dead Sea Scrolls. In a few Septuagint manuscripts, the Tetragrammaton (YHVH) is actually translated in Greek as ΙΑΩ “IAO” (aka Greek Trigrammaton). In other words, the theonym Yahva is translated into Koine Greek as Ιαω (see Lev. 4:27 LXX manuscript 4Q120). This fragment is dated to the 1st century BC. Astoundingly, the name ΙΑΩΝ is the name of Greece (aka Ἰάων/Ionians/IAONIANS), the earliest literary records of whom can be found in the works of Homer (Gk. Ἰάονες; iāones) and also in the writings of the Greek poet Hesiod (Gk. Ἰάων; iāōn). Bible scholars concur that the Hebrew name Yahvan represents the Iaonians; that is to say, Yahvan is Ion (aka Ionia, meaning “Greece”).

We find further evidence that the Tetragrammaton (YHVH) is translated as ΙΑΩ (IAO) in the writings of the church fathers. According to the Catholic Encyclopedia (1910) and B.D. Eerdmans, Diodorus Siculus refers to the name of God by writing Ἰαῶ (Iao). Irenaeus reports that the Valentinians use Ἰαῶ (Iao). Origen of Alexandria also employs Ἰαώ (Iao). Theodoret of Cyrus writes Ἰαώ (Iao) as well to refer to the name of God.

Summary

Therefore, the hidden name of God in the Septuagint, the New Testament, and the Hebrew Bible seemingly represents Greece! The ultimate revelation of God’s name is disclosed in the Greek New Testament by Jesus Christ who identifies himself with the language of the Greeks: Ἐγώ εἰμι τὸ Ἄλφα καὶ τὸ Ὦ (Rev. 1:8). In retrospect, we can trace this Greek name back to the Divine “I am” in Exodus 3:14!

#ΌνομαΘεού#יהוה#exodus3v14#Theonym#onomastics#thelittlebookofrevelation#Yahvan#i am#alpha and omega#javan#Yavan#GentileGod#ΙΑΩ#τομικροβιβλιοτηςαποκαλυψης#Yahva#ΙΑΩΝ#GreekGod#ελικιτιμ#orthonym#Elikittim#4Q120#church fathers#Homer#hesiod#dead sea scrolls#hebrew bible#new testament#koine greek#name of god#bible study

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

hi, an unbeliever keeps questioning me on the accuracy of the Bible after being translated from it's original language. how might I answer his questions about how we know it to be accurate? he seems to be stubborn and as though I am not very smart for believing in the Bible. I know that I can't change his mind rather possibly sew a seed. I'm just not sure how to approach this question specifically because I feel it will lead to him debating me which I do not want.

The translation of the Bible into English was an incredibly detailed, laborious, careful work. The English Bible can be deemed a “literal” translation that attempts to stick as closely as possible to the Greek and Hebrew texts, while still being readable English.

Q. How does the translation process impact the inspiration, inerrancy, and infallibility of the Bible?

A. This question deals with three very important issues: inspiration, preservation, and translation.

The doctrine of the inspiration of the Bible teaches that scripture is “God-breathed”; that is, God personally superintended the writing process, guiding the human authors so that His complete message was recorded for us. The Bible is truly God’s Word. During the writing process, the personality and writing style of each author was allowed expression; however, God so directed the writers that the 66 books they produced were free of error and were exactly what God wanted us to have. See 2 Timothy 3:16 and 2 Peter 1:21.

Of course, when we speak of “inspiration,” we are referring only to the process by which the original documents were composed. After that, the doctrine of the preservation of the Bible takes over. If God went to such great lengths to give us His Word, surely He would also take steps to preserve that Word unchanged. What we see in history is that God did exactly that.

The Old Testament Hebrew scriptures were painstakingly copied by Jewish scribes. Groups such as the Sopherim, the Zugoth, the Tannaim, and the Masoretes had a deep reverence for the texts they were copying. Their reverence was coupled with strict rules governing their work: the type of parchment used, the size of the columns, the kind of ink, and the spacing of words were all prescribed. Writing anything from memory was expressly forbidden, and the lines, words, and even the individual letters were methodically counted as a means of double-checking accuracy. The result of all this was that the words written by Isaiah’s pen are still available today. The discovery of the Dead Sea scrolls clearly confirms the precision of the Hebrew text.

The same is true for the New Testament Greek text. Thousands of Greek texts, some dating back to nearly A.D. 117, are available. The slight variations among the texts—not one of which affects an article of faith—are easily reconciled. Scholars have concluded that the New Testament we have at present is virtually unchanged from the original writings. Textual scholar Sir Frederic Kenyon said about the Bible, “It is practically certain that the true reading of every doubtful passage is preserved. . . . This can be said of no other ancient book in the world.”

This brings us to the translation of the Bible. Translation is an interpretative process, to some extent. When translating from one language to another, choices must be made. Should it be the more exact word, even if the meaning of that word is unclear to the modern reader? Or should it be a corresponding thought, at the expense of a more literal reading?

As an example, in Colossians 3:12, Paul says we are to put on “bowels of mercies” (KJV). The Greek word for “bowels,” which is literally “intestines,” comes from a root word meaning “spleen.” The KJV translators chose a literal translation of the word. The translators of the NASB chose “heart of compassion”—the “heart” being what today’s reader thinks of as the seat of emotions. The Amplified Bible has it as “tenderhearted pity and mercy.” The NIV simply puts “compassion.”

So, the KJV is the most literal in the above example, but the other translations certainly do justice to the verse. The core meaning of the command is to have compassionate feelings.

Most translations of the Bible are done by committee. This helps to guarantee that no individual prejudice or theology will affect the decisions of word choice, etc. Of course, the committee itself may have a particular agenda or bias (such as those producing the current “gender-neutral” mistranslations). But there is still plenty of good scholarship being done, and many good translations are available.

Having a good, honest translation of the Bible is important. A good translating team will have done its homework and will let the Bible speak for itself.

As a general rule, the more literal translations, such as the KJV, NKJV, ASB and NASB, have less “interpretative” work. The “freer” translations, such as the NIV, NLT, and CEV, by necessity do more “interpretation” of the text, but are generally more readable. Then there are the paraphrases, such as The Message and The Living Bible, which are not really translations at all but one person’s retelling of the Bible. (Source: https://www.gotquestions.org/translation-inspiration.html)

Something every Christian should read in order to appreciate their Bible further: What is the history of the Bible in English?

9 notes

·

View notes