#Michael Polanyi

Text

For even the most elaborate objectivist nomenclature cannot conceal the teleological character of learning and the normative intention of its study. Its supposedly objective terms still do not refer to purposeless facts but to well functioning things. Something is a 'stimulus' only if it succeeds in stimulating. And though 'responses' may be meaningless in themselves, the state of affairs called 'reinforcement' functions as such by converting at least one particular response into a sign or a means to an end. Moreover, the result of a series of successful reinforcements is, by definition, a habit which the experimenter deems right. So even the most rigidly formalized theory of learning does lay down a system of rightness for the purpose of assessing and interpreting the rationality of the animal's behaviour.

Michael Polanyi, Personal Knowledge

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rolul cunoașterii tacite a lui Polanyi în analiza informațiilor

Sfetcu, Nicolae (2024), Rolul cunoașterii tacite a lui Polanyi în analiza informațiilor, Intelligence Info, 3:3, ppp,

The Role of Polanyi’s Tacit Knowledge in Intelligence Analysis

Abstract

Intelligence analysis, a field that requires the synthesis and interpretation of large amounts of data to make informed decisions, is inherently complex. It involves more than explicit data processing; it…

View On WordPress

#agenții de informații#analiza informațiilor#cunoașterea explicită#cunoașterea tacită#Michael Polanyi

0 notes

Text

The act of knowing includes an appraisal, a personal coefficient which shapes all factual knowledge.

Michael Polanyi

0 notes

Text

“The third philosophical belief which we shall consider is any deontological morality, which is ipso facto destructive of any economic system based on rewards and consequences because it makes responsibility for consequences (especially responsibility for wealth) morally irrelevant. This, too, comes from a predominately Kantian base, for Kant is the sine qua non of deontologists, the father of "duty" and the chief intellectual enemy of deontologism's opposite: a teleological ethic.

For it is a deontological, duty-centered, ethic which is in many ways at the base of the new "a priori" collectivist moralists. What motivates them, philosophically speaking? The answer lies in Kant's beliefs: "the basis of obligation must not be sought in human nature or in the circumstances of the world in which he man is placed, but a priori simply in the concepts of pure reason." “We must work out a pure ethics which, ‘when applied to man, does not borrow the least thing from the knowledge of man himself.’” And, as Copleston puts it: "Kant obviously parts company with all moral philosophers who try to find the ultimate basis of the moral law in human nature or in any factor in human life or society."

This means that ethics has nothing to do with man's nature, and particularly with his needs (as an individual, a species or a kind of living organism), or with the world as it is, with consequences, since consequences are the leitmotif of a teleological approach to morality. (Such as that of Aristotle in his Ethics.)

Against this kind of a mentality, "thinking economically” is more than useless. Yet this mentality is one of the major enemies of a free market. While, as Kristol implies but does not explicitly state, an older "anticapitalistic mentality" (to borrow Mises phrase) was teleological, and dealt in terms of cause and effect, of consequences of capitalism, the newer anticapitalistic mentality is predominately deontological, and is not concerned with objective consequences at all. Thus the older enemies of liberty could to some extent be met by "thinking economically" with demonstrations that capitalism did not produce wars, depressions, chaos, etc. But clearly the new opponents of capitalism cannot be met on this ground at all, and require that we define the new battlefield: philosophy.

The new anticapitalists are, in spirit and motive, deontologists, and thus criticize not so much the consequences of capitalism (though this teleological element is present), but motives, e.g., the profit motive, acquisitiveness, "materialism" and the like.

Why is "thinking economically" powerless to meet this onslaught? Because it is not aware of and does not defend its own presuppositions, the wider context - philosophical context - of work. Thus, such thinkers are powerless to defend the profit motive - in the fullest sense of the word "motive" - since this cannot be done without defending the wider, noneconomic "motive" of which the profit motive, qua motive, is a part: self-interest. And this lack of a concern with defining and validating proper or rational self-interest disarms the advocates of capitalism on a far deeper level than economics. For they can only apologize for the motor of capitalism as a motive by referring to its beneficial consequences. But to those whose primary focus is on motives and alleged moral character (character divorced from consequences is rather grotesque), this apology is just that. Thus the motor must be defined, advocated and justified, and this by taking up the moral issues at their root.

(…)

In fact and in reality, communism is based on a deontological, duty-centered ethic - despite the legions of communist concessions to motives of self-interest, that is, to reality. Everyone is expected to work to serve the state (society or fellow men) regardless of rewards. Under communism, the introduction of rewards serves the function of grafting a teleological aspect onto a deontological framework. But, then, "hypocrisy is the coin paid to virtue by vice."

The American system of private enterprise, based on risks and rewards, is founded on precisely the opposite premise as communism. In briefest terms, it is founded on a belief that man is an active agent, a free agent who is responsible for his actions, actions which have objective consequences. Teleology comes in on many levels, but none is more important than this: under capitalism, a man has the responsibility to choose his goals, to identify the actions necessary to attain them, and to accept the consequences of his choices and actions. Since man is not omniscient, and since ultimately no man can assume full control over or responsibility for the choices and actions of another human being, or even fully predict the actions of other men in any detail, this means that the factor of risk permeates every aspect of man's life, on every level from that of knowledge (particularly in the case of science) to that of choosing his role in the structure of production.

Under a thoroughgoing teleological framework, every man has the ultimate responsibility for his own life. If he chooses not to sustain it, then nature takes its course. If, however, he does choose to sustain his life, it is the teleological process of final causality, the relationship between ends and means, that comes into play.

But since time is always scarce in human lives, and since man is not omniscient, the element of risk becomes even more important here. This is because the number of decisions and considerations which must go into any choice are so vast that they are often sorted in lightning-like fashion by the human mind. Besides relying on explicit reasoning, therefore, man must always rely on certain subconscious processes, on what Polanyi has termed "tacit knowledge," knowledge which is not grasped explicitly but which still functions as a form of awareness. Since facts of reality change, therefore (which is a metaphysical fact), and human knowledge is always limited in scope (an epistemological issue), this necessitates a correlative psychological focus and choice, which every man can only perform for himself. In any decision, choice and action, there is always this tacit question: "Have I spent enough time in gathering relevant information, engaging in specialized study and in organizing and verifying what knowledge I do have?"

This fundamental fact of human nature, of reality, needs to be taken into account by any politico-economic system. Capitalism does; any form of collectivism does not.

(…)

There are obviously a great many other philosophical foundations of the capitalistic system, and the absence of these from the cultures of America and Western Europe is undoubtedly responsible for many of the internal conflicts in these cultures. For no culture is on a more firm foundation than its cultural-philosophical base. If the profit motive and the seeking of individual goals (particularly self-interested goals) comes under attack, and if the members of a society do not know how to deal with such attacks, a basic intellectual-cultural schism is bound to be the result. For that which has not been explicitly identified is not within a man's - or a nation's - conscious control. This applies to any of the foundations of a market system, whether it be the belief in free will or individual ownership of property, from epistemological and metaphysical issues to those on a much more journalistic level.

It was Kristol's thesis, in essence, that the case for liberty has been won on economic grounds, but that economics is not enough. It has been my thesis that one of the factors which should be considered in constructing a case for liberty and capitalism is philosophy, and to show how a few philosophical issues can have a bearing on very specific political matters. Certainly philosophy is not enough for a full defense of capitalism, particularly as it exists in the United States, but I think that it is vitally important that we see it as necessary.

For if wider philosophical issues are ignored, then we run the risk of seeing not only liberty disintegrate before our eyes, but the very foundations of civilization itself. And from that, recovery may not even be possible.” - ‘The Defense of Capitalism in Our Time’ (1975)

#roy childs#roy a childs jr#liberty#libertarian#libertarianism#capitalism#philosophy#kristol#irving kristol#kant#immanuel kant#deontology#teleology#ethics#polanyi#michael polanyi#hayek#friedrich hayek#walter block#ayn rand#hoppe#Hans hermann hoppe#henry hazlitt#economics#yaron brook#szasz#thomas szasz

1 note

·

View note

Text

Tacit knowledge and high value work

Tacit knowledge is at the heart of high value work. Why? Because it’s complex. New post.

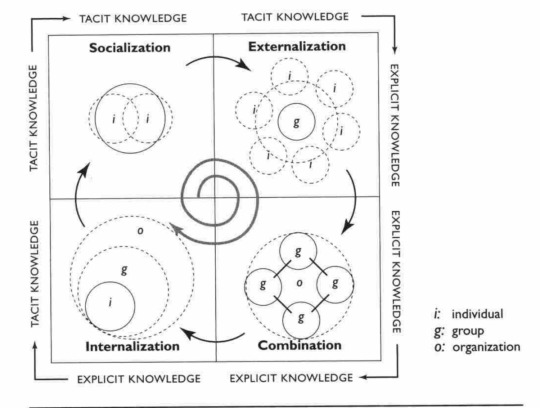

There was a lively discussion about the role of tacit knowledge over a couple of days at John Naughton’s daily blog recently. I’ll come back to the reason why the subject came up in a moment or so.

I came quite late in life to questions of knowledge management, and my first exposure was to the work of the Japanese professors Nonaka and Takeuchi, and their ‘SECI’ model, which argues explicitly…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Michael Polanyi (11 March 1891 – 22 February 1976)

Born Mihály Pollacsek in Budapest in 1891, Michael Polanyi first studied medicine at the University of Budapest before studying chemistry in Germany. He served in the Austro-Hungarian army as a medical officer during World War I, finishing a PhD on adsorption in the meantime, then returned to medicine after the war. He emigrated to Germany briefly, then again to the UK in 1933 after the rise of the Nazi party, working in the field of physical chemistry. Polanyi is often regarded as a polymath, with diversified interests throughout his life including chemistry, economics, and philosophy. In the field of materials science he is known for his work, simultaneous but independent from the work of Egon Orowan and G.I. Taylor, proposing a theory of plastic deformation in ductile materials using the theory of dislocations.

Sources/Further Reading: (Image source - Wikipedia) (infed.org) (ISI) (1996 article)

#Materials Science#Science#Plasticity#Dislocations#Scientists#Science history#ScientistSaturday#2024Daily

11 notes

·

View notes

Note

I picked up the funny Kuhn book on your rec, and noticed Karl Popper on the same shelf, framing himself in contrast. Do you have/know of any good critiques on Popper in general, or his indeterminism in particular? I'm guessing he didn't convince every Marxist and someone's bound to have responded by now.

yea popper sucks. i mean kuhn himself was responding to / critiquing popper; they very famously had a long ongoing dispute. but like i said before, kuhn is also not where it's at imo. like, not that academic citations are the be-all end-all of intellectual value, but there are reasons you don't typically see either of these guys cited by people working in history / philosophy of science these days lol.

anyway in regards to the marxism angle of this i will say: a major problem with hist/philsci is that these disciplines are pretty ensconced in universities (conservative institutionally & intellectually) and have also taken a long time to even start looking beyond the horizons of great man history, the 'western canon', &c. so the lack of marxists / communists in these fields is like, even more pronounced than in academic history more broadly. like it's insane that people like bob young and roger cooter and adrian desmond are still, like, standouts in this respect lol. so, although there are many many marxists who have responded to popper on those terms, and many many historians and philosophers of science who have responded on that side, the sliver of overlap here is a lot smaller than it should be.

i would definitely read with a critical eye and be on the lookout for places where these texts fail specifically because their authors are not engaging in materialist or properly historicised analysis, or are just blatantly reactionary themselves, in different ways to popper. but, a few places to start with political histsci and philsci critiques of him, or just useful accounts of his legacy and critics:

The Cambridge Companion to Popper (2016). Jeremy Shearmur and Geoffrey Stokes (eds.). <-usual disclaimer that cambridge edited vols. are methodologically, politically, and epistemologically playing it VERY safe. you often want to read them 'backwards', ie, read for what's not being said as much as for what's actually in there. consider this a document that shows what sorts of debates are being permitted, centred, and accepted as 'mainstream' and 'reasonable'.

Epistemological Battles on the Home Front: Early Neoliberals at War against the Social Relations of Science Movement (2021). Beddeleem, Martin. Journal of the History of Ideas Volume: 82 Issue: 4 Pages: 615-636. 10.1353/jhi.2021.0035

Relations between Karl Popper and Michael Polanyi (2011). Jacobs, Struan & Mullins, Phil. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Volume: 42 Pages: 426--435.

Thoughts on political sources of Karl Popper's philosophy of science (1999). Jacobs, Struan. Journal of Philosophical Research Volume: 24 Pages: 445-457

Popper and His Popular Critics: Thomas Kuhn, Paul Feyerabend and Imre Lakatos (2014). Agassi, Joseph. ISBN: 3319065866

Science and Politics in the Philosophy of Science: Popper, Kuhn, and Polanyi (2010). Mary Jo Nye. Chapter in: Epple, Moritz & Zittel, Claus (2010) Science as Cultural Practice. ISBN: 9783050044071

Karl Popper, the Vienna Circle, and Red Vienna (1998). Hacohen, Malachi Haim. Journal of the History of Ideas Volume: 59 Pages: 711-734.

Science, politics and social practice: Essays on Marxism and science, philosophy of culture and the social sciences in honor of Robert S. Cohen (1995) Gavroglu, Kostas; Stachel, John J.; & Wartofsky, Marx W. (Eds.). <-haven't read the popper chapter in this, can't promise it's good

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

The dependence of the higher on the lower, and the greater risks that come with the higher (sometimes "higher" just means "more complex", but more often than not there's an evaluative claim being made) - maybe it's trivial to say that those two basic ideas as expressed by Michael Polanyi here are recurring themes in The Four Loves, but it's something I've found helpful to keep in mind.

Lewis himself says in the Eros chapter that -

The love which leads to cruel and perjured unions, even to suicide-pacts and murder, is not likely to be wandering lust or idle sentiment. It may well be Eros in all his splendour; heart-breakingly sincere; ready for every sacrifice except renunciation.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

One early critic of human-level AI was Hubert Dreyfus. During the first wave of AI, Dreyfus argued that symbolically mediated cognitive processes require a context of tacit, informal background knowledge, in the sense indicated by Polanyi (1958), to render them meaningful (Dreyfus, 1965). A large portion of human knowledge, for example, domain-specific expertise, is tacit and informal and so cannot be represented symbolically. Thus, computation alone can- not account for knowledge with a tacit component (Dreyfus, 1976, 1992).

Stephen Roddy. 2023. “Creative Human-Machine Collaboration: Toward a Cybernetic Approach to Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning Techniques in the Creative Arts.” In AI and the Future of Creative Work, edited by Michael Filimowicz. London, Routledge.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Books read in 2022!!

rereads are italicized, favorites are bolded

1. Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire by JK Rowling

2. Boxers by Gene Luen Yang

3. Saints by Gene Luen Yang

4. The Maltese Falcon by Dashiell Hammett

5. The Murder of Roger Ackroyd by Agatha Christie

6. Immortal Poems of the English Language by Oscar Williams

7. Soldier’s Home by Ernest Hemingway

8. Shadow and Bone by Leigh Bardugo

9. Harry Potter and the order of the phoenix by JK Rowling

10. The Dead by James Joyce

11. Soldiers Three by Richard Kipling

12. The Hidden Life of Trees by Peter Wohlleben

13. Richard iii by William Shakespeare

14. Balcony of Fog by Rich Shapiro

15. All Systems Red by Martha Wells

16. Artificial Condition by Martha Wells

17. I have no mouth and I must scream by Harlan Ellison

18. Siege and Storm by Leigh Bardugo

19. The moment before the gun went off by Nadine Gordimer

20. The importance of being earnest by Oscar Wilde

21. A farewell to arms by Ernest Hemingway

22. Rogue Protocol by Martha Wells

23. Rules for a knight by Ethan Hawke

24. Harry Potter and the Half Blood Prince by JK Rowling

25. The Secret History by Donna Tartt

26. Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows by JK Rowling

27. Gerard Manley Hopkins: The Major Poems by Gerard Manley Hopkins

28. Highly Irregular by Arika Okrent

29. The Green Mile by Stephen King

30. The Swan Riders by Erin Bow

31. The King’s English by Henry Watson Fowler

32. The Truelove by Patrick O’Brian

33. The Glass Key by Dashiell Hammett

34. The Wine-Dark Sea by Patrick O’Brian

35. The Commodore by Patrick O’Brian

36. An Old-Fashioned Girl by Louisa May Alcott

37. Long Day’s Journey Into Night by Eugene O’Neill

38. The Disaster Area by JG Ballard

39. The Tacit Dimension by Michael Polanyi

40. Wicked Saints by Emily A Duncan

41. The Pillowman by Martin McDonagh

42. The Thief by Megan Whalen Turner

43. The Goldfinch by Donna Tartt

44. The Queen of Attolia by Megan Whalen Turner

45. Exit Strategy by Martha Wells

46. The King of Attolia by Megan Whalen Turner

47. A Conspiracy of Kings by Megan Whalen Turner

48. Thick as Thieves by Megan Whalen Turner

49. Return of the Thief by Megan Whalen Turner

50. Cat’s Cradle by Kurt Vonnegut

51. Confessions of St. Augustine by St. Augustine of Hippo

52. Little Lord Fauntleroy by Frances Hodgson Burnett

53. The Yellow Admiral by Patrick O’Brian

54. Bad Pharma by Ben Goldacre

55. The Russian Assassin by Jack Arbor

56. The ones who walk away from Omelas by Ursula K LeGuin

57. Captains Courageous by Rudyard Kipling

58. The Iliad by Homer

59. The Treadstone Transgression by Joshua Hood

60. The Hundred Days by Patrick O’Brian

61. Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are dead by Tom Stoppard

62. The Myth of Sisyphus by Albert Camus

63. Waiting for Godot by Samuel Beckett

64. Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, the Pearl, and Sir Orfeo (unknown)

65. Persuasion by Jane Austen

66. The Outsiders by SE Hinton

67. Bartleby the Scrivener by Herman Melville

68. The Odyssey by Homer

69. Dead Cert by Dick Francis

70. The Oresteia by Aeschylus

71. The Network Effect by Martha Wells

72. All Art is Propaganda: Critical Essays by George Orwell

73. This is how you lose the time war by Amal El-Mohtar

74. The Epic of Gilgamesh (unknown author)

75. The Republic by Plato

76. Oedipus Rex by Sophocles

77. On the Genealogy of Morals by Friedrich Nietzsche

78. Ere the Cock Crows by Jens Bjornboe

79. Mid-Bloom by Katie Budris

80. Blue at the Mizzen by Patrick O’Brian

81. 21 by Patrick O’Brian

82. To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee

83. Battle Cry by Leon Uris

84. Devils by Fyodor Dostoevsky

85. The Uncanny by Sigmund Freud

86. The Door in the Wall by HG Wells

87. Oh Whistle and I’ll Come to You My Lad by MR James

88. The Birds and Don’t Look Now by Daphne Du Maurier

89. The Weird and the Eerie by Mark Fisher

90. Blackout by Simon Scarrow

91. In Cold Blood by Truman Capote

92. No Exit and Three Other Plays by Jean-Paul Sartre

93. The Open Society and its Enemies volume one by Karl Popper

94. Mother Night by Kurt Vonnegut

95. The Ethics of Ambiguity by Simone de Beauvoir

96. The Cue for Treason by Geoffrey Trease

97. The things they carried by Tim O’Brien

98. A very very very dark matter by Martin McDonagh

99. The Road to Serfdom by Friedrich A Hayek

100. The Lonesome West by Martin McDonagh

101. A Skull in Connemara by Martin McDonagh

102. The Beauty Queen of Leenane by Martin McDonagh

103. Beyond Good and Evil by Friedrich Nietzsche

104. The Power and the Glory by Graham Greene

105. The Shepherd by Frederick Forsyth

106. Things have gotten worse since we last spoke and other misfortunes by Eric LaRocca

107. Each thing I show you is a piece of my death by Gemma Files

108. Different Seasons by Stephen King

109. Dracula by Bram Stoker

110. Inker and Crown by Megan O’Russell

111. Out of the Silent Planet by CS Lewis

112. Killers by Patrick Hodges

113. The Game of Kings by Dorothy Dunnett

114. The Rise and Reign of Mammals by Stephen Brusatte

115. Any Means Necessary by Jack Mars

116. The Birth of Tragedy by Friedrich Nietzsche

117. In A Glass Darkly by J Sheridan le Fanu

118. Collected Poems by Edward Thomas

119. The Longer Poems by TS Eliot

120. Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone

121. The Elegant Universe by Brian Greene

122. The Antichrist by Friedrich Nietzsche

123. Choice of George Herbert’s verse by George Herbert

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

The structural kinship between knowing a person and discovering a problem, and the alignment of both with our knowing of a cobblestone, call attention to the greater depth of a person and a problem, as compared with the lesser profundity of a cobblestone. Persons and problems are felt to be more profound, because we expect them yet to reveal themselves in unexpected ways in the future, while cobblestones evoke no such expectation. This capacity of a thing to reveal itself in unexpected ways in the future I attribute to the fact that the thing observed is an aspect of a reality, possessing a significance that is not exhausted by our conception of any single aspect of it. To trust that a thing we know is real is, in this sense, to feel that it has the independence and power for manifesting itself in yet unthought of ways in the future. I shall say, accordingly, that minds and problems possess a deeper reality than cobblestones, although cobblestones are admittedly more real in the sense of being tangible. And since I regard the significance of a thing as more important than its tangibility; I shall say that minds and problems are more real than cobblestones. This is to class our knowledge of reality with the kind of foreknowledge which guides scientists to discovery.

Michael Polanyi, The Tacit Dimension

An object-oriented ontologist would draw on the phenomenology of "adumbrations" or the profiles we can get from perceiving an inanimate thing and objéct that a cobblestone really can "reveal [itself] in unexpected ways in the future" just as a person or problem can.

I thought of an analogy with set theory a while back, namely the fact that there are different sets of numbers which enjoy greater or lesser cardinalities despite all having an infinite amount of elements. The ways a person can reveal (or conceal) themselves clearly has a much larger cardinality than that of a cobblestone. But maybe that doesn't capture the qualitative, difference-in-kind in our encounters with each other which I'm sure no OOOist actually doubts (and I hope my understanding of the very basics of set theory is adequate enough).

An OOOist might again objéct that such an account privileges the human, but I really do think it's significant that a cobblestone would never raise that complaint. And as far as animals go, I guess this all coincides with what Heidegger said about them being "poor in world", but not lacking world altogether.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thinking With Owen Barfield (dialogue with Ashton Arnoldy and Daniel Garner)

Ashton Arnoldy and Daniel Garner joined me to discuss the work of Owen Barfield. Here’s a quick summary of what we discussed:

Introduction to Barfield:

Daniel’s Journey: Daniel describes his journey from traditional philosophy to discovering alternative thinkers like Michael Polanyi, Alfred Korzybski, and eventually Rudolf Steiner, which led him to Barfield. He emphasizes how Barfield’s ideas…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

An Exploration of How Objectivity Is Practiced in Art - Siun Hanrahan

ANALYSIS OF THE ARTMAKING PROCESS

The art-making process begins with an initial idea or set of ideas, comparable to Monroe Beardsley's "incept" [20]. Something-be it verbal, visual, aural or whatever-strikes a chord or claims attention, although what is important about it need not be particularly clear.

https://www-jstor-org.ezproxy.massey.ac.nz/stable/24434910

https://philpapers-org.ezproxy.massey.ac.nz/rec/BEATAP-2

"restrainer/restrained" was the initial idea from which the art-making process proceeded; in the second series of sculptures the initial idea was an experience of movement.

"we can know more than we can tell"-a sense that exploring the thing/idea that strikes a chord will prove fruitful [21].

https://www-taylorfrancis-com.ezproxy.massey.ac.nz/chapters/edit/10.4324/9780080509822-7/tacit-dimension-michael-polanyi

once a set of ideas has been mapped onto a set of physical relations, adjusting the relations between the physical parts effects adjustments within the set of ideas.

In playing with the physical relations one can assign priority to either the materials' potential or the forms being generated.

An important part of the art-making process is standing back and considering what has been made. Such consideration generally focuses on three things:

1. The ways in which what has been made succeeds in manifesting its intended concerns.

2. The ways in which what has been made fails in manifesting its intended concerns.

3. What is evident in the work apart from its intended concerns? When a work is thus challenged, other points of view are anticipated.

Different viewers ask different questions of or bring different interests to bear upon, the work, and one's perception of the work may be re-structured by engaging in or adopting alternative points of view in relation to it.

what criticism or exposure to an alternative point of view does is draw one's attention to certain features so that from that point forward one sees those features [25].

https://books-google-co-nz.ezproxy.massey.ac.nz/books?hl=en&lr=&id=LiwgjNiHkm4C&oi=fnd&pg=PP11&dq=Ludwig+Wittgenstein,+Wittgenstein%27s+Lectures,+Cambridge&ots=DwT-5qybsL&sig=SItDbDfutpCxs7BSdWUXP4sb42U&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=Ludwig%20Wittgenstein%2C%20Wittgenstein's%20Lectures%2C%20Cambridge&f=false

This aspect of the making process is the most "objective." The first two questions above explore whether the intended dynamic is actually manifest in the work; can others see what the artist sees. The third question explores the resonance of the work (of its materials, technique and form) from points of view other than one's own.

t there is more and less in the "made thing" than was anticipated-that is, the work frequently exceeds expectations in some respects and falls short of expectations in other respects.

The key to this inter-subjective exposure is to determine whether or not the intended reading survives despite the effect of different perspectives and, following from this, what needs to be done to achieve or amplify this.

Difficulties identified in the work may be either "logical" or visual [26]. Logical flaws are ones in which the material interaction fails to exemplify the idea behind it. There is a breakdown in the manifestation of the idea. Visual flaws are ones in which the material interaction is not visually acceptable or satisfying

As used here "logical" applies to the step-by-step process through which "the conception" of a work is generated in the material interaction. Consequently its true equivalent is not the visual but the step-by-step process by which the visual is generated by the material interaction. Using these particular alternatives thus reveals a bias in my art practice. I prioritize the conception and so where there is a visual breakdown I search for a more elegant arrangement of the conceptual logic rather than the visual logic. Nonetheless, I would argue that this does not devalue the visual, as it is this that drives my refinement of the conception.

the logical and the visual are generally symbiotic; when a flaw is identified in the one, it can usually be resolved by re-thinking the other.

. Deciding which considerations are brought forward through further making generally involves both objective and subjective inflections of thought

A concern for inter-subjective judgment, or "objectivity," is reflected in modifications aimed at amplifying the intended reading of the work, given the effect of the different perspectives encountered.

A concern for "subjectivity" is reflected in modifications that are interesting but peripheral to the intended reading of the work.

Eventually, the making-considerationmaking dynamic must be brought to a halt and a decision taken to the effect that a "made thing" can stand on its own as an artwork

The making process must stop at some "made thing" which we decide to accept. If we do not come to any decision, and do not accept some "made thing" or other, then the "making process" will have led nowhere. But considered from a logical point of view, the situation is never such that it compels us to stop at this particular "made thing" rather than that, or else give up the "making process" altogether .... Thus if the "making process" is to lead us anywhere, nothing remains but to stop at some point or other and say that we are satisfied for the time being [28].

https://www-taylorfrancis-com.ezproxy.massey.ac.nz/books/mono/10.4324/9780203994627/logic-scientific-discovery-karl-popper-karl-popper

This decision, to let a "made thing" stand as an "artwork," is taken (1) if the "made thing" succeeds in manifesting its intended concerns, (2) if it has not been shown to fail in relation to its intended concerns, and (3) if what is evident in the "made thing" apart from its intended concerns does not inhibit or overwhelm them.

intuitive art-making

scientific investigation places greater emphasis upon the critical examination of proposed orders, while artistic investigation places greater emphasis upon conceiving alternative orders.

the relationship between art and science is not a matter of boundaries but of intertwined inflections of understanding. The order that science brings to our understanding of the world is complemented by art's exhibition of our ultimate responsibility for ordering the world.

0 notes

Quote

As the philosopher Michael Polanyi observed in 1966, “We can know more than we can tell,” meaning that our tacit knowledge often exceeds our explicit formal understanding.

AI Could Actually Help Rebuild The Middle Class | NOEMA

0 notes

Text

Epistemologia serviciilor de informaţii

Despre analogia existentă între aspectele epistemologice şi metodologice ale activităţii serviciilor de informaţii şi unele discipline ştiinţifice, pledând pentru o abordare mai ştiinţifică a procesului de culegere şi analiză de informaţii din cadrul ciclului de informaţii. Afirm că în prezent aspectele teoretice, ontologice şi epistemologice, în activitatea multor servicii de informaţii, sunt subestimate, determinând înţelegere incompletă a fenomenelor actuale şi creând confuzie în colaborarea inter-instituţională. După o scurtă Introducere, care include o istorie a evoluţiei conceptului de serviciu de informaţii după al doilea război mondial, în Activitatea de informaţii definesc obiectivele şi organizarea serviciilor de informaţii, modelul de bază al acestor organizaţii (ciclul informaţional), şi aspectele relevante ale culegerii de informaţii şi analizei de informaţii. În secţiunea Ontologia evidenţiez aspectele ontologice şi entităţile care ameninţă şi sunt ameninţate. Secţiunea Epistemologie include aspecte specifice activităţii de informaţii, cu analiza principalului model (Singer) folosit în mod tradiţional, şi expun o posibilă abordare epistemologică prin prisma conceptului de cunoaştere tacită dezvoltat de omul de ştiinţă Michael Polanyi. În secţiunea Metodologii prezint diverse teorii metodologice cu accent pe tehnicile analitice structurale, şi câteva analogii, cu ştiinţa, arheologia, afacerile şi medicina. Lucrarea se încheie cu Concluziile privind posibilitatea unei abordări mai ştiinţifice a metodelor de culegere şi analiză a informaţiilor din cadrul serviciilor de informaţii.

Read the full article

0 notes