#Paul Kowert

Text

youtube

Song Review: Aoife O’Donovan & Hawktail - “Reason to Believe” (Live, March 26, 2023)

Swapping out Bruce Springsteen’s grizzled vocals for the soothing sweetness of Aoife O’Donovan’s voice and outfitting the song with bluegrass instrumentation, O’Donovan and Hawktail transformed “Reason to Believe” without erasing the Boss man’s fingerprints.

Recorded live in New York March 16, 2023, and just released, the track is expertly mixed allowing two acoustic guitars, Dominick Leslie’s mandolin, Paul Kowert’s double bass and Brittany Haas’ fiddle to intertwine with gorgeous singing from O’Donovan and fellow guitarist Jordan Tice on harmonies. Add in just enough crowd reaction to reinforce how special this performance was and remains and this exquisite version of “Reason to Believe” is almost unbelievable.

Grade card: Aoife O’Donovan & Hawktail - “Reason to Believe” (Live - 3/26/23) - A+

1-2-24

#Youtube#aoife o'donovan#hawktail#bruce springsteen#reason to believe#brittany haas#crooked still#paul kowert#punch brothers#dominick leslie#molly tuttle & golden highway#jordan tice

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

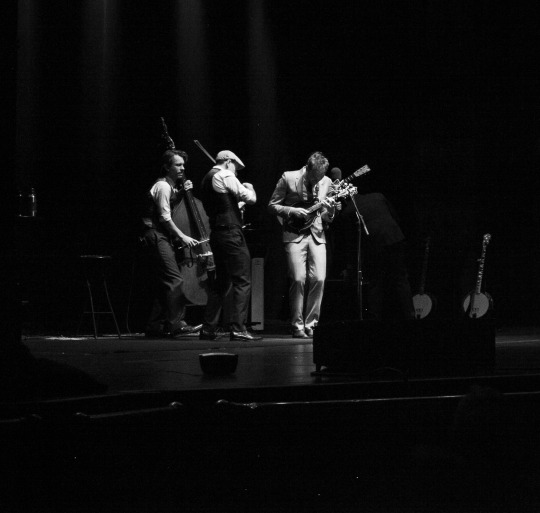

Gillian Welch & David Rawlings Live Show Review: 9/6, Cahn Auditorium, Evanston

David Rawlings & Gillian Welch

BY JORDAN MAINZER

In 2020, right before COVID shut down the country, a tornado outbreak tore through Nashville, killing 25, injuring hundreds, and leaving tens of thousands without electricity. Among the destruction was Woodland Sound Studios, the home studio of contemporary folk legends Gillian Welch and David Rawlings, which they spent the next years rebuilding, all while excavating treasure troves of unreleased tunes. But the first true phoenix to rise from the flames is Woodland (Acony), their latest studio album, which pays tribute not so much to a place that was and stands again, but the very act of creating in the face of loss. And the duo's performance of many of the album's songs last Friday at Cahn Auditorium, a pre-show for the inaugural Evanston Folk Festival, cemented the extent to which their creative power conquers all.

Welch

Welch and Rawlings dare you to focus away from absence. Though Woodland as an album benefits from various studio flourishes and guest players, its songs are strong in any capacity. During "Empty Trainload of Sky", the duo's tight vocal harmonies and Rawlings' bluesy picking didn't make you miss the studio version's propulsive percussion; instead, you were focused primarily on the way in which Welch turns a visual hallucination into a treatise on knowledge and doubt. "Was it spirit? Was it solid? Did I ditch that class in college?" she sings, simultaneously winking and full of wonder. Similarly, the poetry of "Hashtag" proved the studio version's French horns and strings to be borderline superfluous, the duo's Guy Clark-inspired musings garnering equal amounts laughs and existential crises. Even some songs themselves juxtapose elements that seem to be lacking, in a vacuum, with others that are more whole, the overall sum becoming something rather beautiful. On the wonderful "What We Had", Rawlings' cracking Neil Young falsetto contrasted the might of his guitars, as he and Welch harmonized and traded verses about impermanence: "What we had is broken, though we thought we'd never lose it." The rolling "The Day The Mississippi Died", which imagines this country's preeminent river drying up, sees a mix of tragedy and jubilation in the apocalypse, the best song of its kind since Joan Shelley's "The Fading".

Paul Kowert, Rawlings, & Welch

Of course, when listening to a Welch and Rawlings album, or witnessing one of their life-affirming live shows, you can't help but be wowed by the interplay of the two singers and players. If I hadn't written it down, I wouldn't have been able to tell you on which songs they were joined by upright bassist Paul Kowert; even though his playing was terrific, Welch and Rawlings draw your attention. Rawlings' prickly leads played off of Welch's high-register, rhythmic wincing on "The Bells and the Birds". In terms of stage presence, Welch is the silent and still warrior, Rawlings jerky, his expressions embedding within her strums on "Lawnman" and her mournful declarations on classic "Revelator". Perhaps the song that best encapsulated both their creative partnership and their strengthened appreciation for music-making was "Howdy Howdy". "Dry your eyes, don't you cry, ain't gonna rain no more," Welch sings to Rawlings', as if she's comforting him in the face of tragedy; the chorus of "You and me are always gonna be howdy howdy / You and me, always walk that lonesome valley" acts as a statement of purpose. Before playing the song on Friday, Welch was having trouble tuning her banjo, so Rawlings nursed it back to health so they could move on. On both Woodland and forever, Welch and Rawlings have each other's back.

Rawlings & Welch

#live music#gillian welch & david rawlings#acony#evanston folk festival#woodland#gillian welch#david rawlings#woodland sound studios#cahn auditorium#acony records#guy clark#neil young#joan shelley#paul kowert

1 note

·

View note

Text

Brittany Haas, Paul Kowert, Jordan Tice: Down The Hatch

youtube

1 note

·

View note

Text

Jordan Tice with an opening set by Elise Leavy Wednesday, October 19th! Doors 7:30, music at 8pm

Thrilled to be welcoming Jordan Tice back to the House of Love! It’s been forever since he was here--first with Brittany Haas and Paul Kowert...in the days when Hawktail was known as Haas Kowert Tice, and then 6 years ago with his band Horse County. And Nashville neighbor Elise Leavy is opening the show. Should be a sweet autumnal evening...and it’s the unofficial 10th anniversary of the first House of Love show in 2012! We’re planning some additional fanfare around that fact in the nearish future, but for now, come raise a glass and celebrate with Jordan and Elise. Maybe it’ll even be warm enough to be outside in the backyard again. If not, masks are strongly encouraged.

Hope to see you!

xo

Jordan Tice with an opening set by Elise Leavy • Wednesday, October 19th, doors 7:30, music at 8pm. $25 suggested donation, all for the musicians (as always). Venmo @amyhelfand in advance if you can, please, to reserve a spot, along with an email rsvp to [email protected]. Otherwise Venmo or cash donation at the door. Exact address emailed when you rsvp.

Bring your favorite libations. See you soon!

0 notes

Text

A Brief History of Magnificent Bird

In the aftermath of a year off the internet, I’ve become low-key obsessed with Lewis Hyde’s book The Gift, in which he argues that the movement of a gift—or a work of art—from one individual to another helps to define the community in which the gift or artwork circulates.

Today, my fifth album, Magnificent Bird, is released into the world, and it is, for me, most fundamentally, an expression of my community. There are no hired guns: only musicians whom I cherish as much for their humanity and friendship as I do for their artistry. So I thought it would be appropriate to mark the unveiling of this project with a little history & chronology of a dozen-and-a-half musical relationships that have made this record possible.

1989 - At our respective homes in Rochester, New York, Ted Poor and I play boogie-woogie duets: me on piano, Ted on drums. We’re also on the same Little League team; he often plays first-base, I’m over at shortstop for a quick 6-3 on a ground ball to the left side of the infield. Twenty-five years later, he plays drums in The Ambassador, my first piece for the Brooklyn Academy of Music. Ted was so incredibly generous on this project, recording 3,287 versions of “Hot Pink Raingear” before we arrived at the approach heard on the album. His sense of rhythm lights a room, and he is my oldest friend — not just on this LP, but in life.

2006 - The Nickel Creek bus drops Chris Thile (as well as Sean and Sara Watkins) at my parents’ house in Santa Rosa, California. We start playing music at around 1am. Fifteen years, hundreds of cups of coffee, and dozens of alcohol-fueled arguments about the “correct” approach to rhythm in the music of J.S. Bach later, Chris is one of my closest friends, and also a hero. We all know what a monster, once-in-a-generation talent he is. What is maybe less apparent is the insane work ethic that undergirds his seemingly effortless command of his instrument, an ethic I got to witness up close while opening some 60 shows for Punch Brothers. The only person whose approach to rhythm is as continually mind-boggling as Ted Poor’s is Chris’, hence the mando-drums on “To Be American.”

2007 - I meet Alex Sopp through her new music ensemble, yMusic. I will forever be spoiled by the fact that she’s the first flutist I work with: her tone singing, her sense of phrase totally intuitive and poetic. Over the course of fifteen years, we share with each other many, many, many photographs of our cats. Her collaborative spirit was evident in her work on this album: for “Hot Pink Raingear,” I asked if she could play a synth riff on some “messed up whistles and flutes,” and she sent back, thirty-six hours later, fourteen different tracks of various antique wind instruments. I wish I had kept all of it for you to hear, but sometimes less is more.

2008 (part one) - I hear Elizabeth Ziman sing at a tiny cafe in Park Slope, Brooklyn. I am instantly in love with her voice and songwriting. I would happily listen to her sing tax returns or technical manuals or the transcripts of municipal water supply hearings; she is magic. Somehow, after an almost fifteen year friendship, this is the first time we’ve worked together on record; her singing on “Sit Shiva” is, for me, what makes the song.

2008 (part two) - Outside a rural elementary school in Switzerland, I am approached by a young man, who, seeing my banjo case, announces that he “plays folk music, too.” It’s Paul Kowert, who that autumn would join Punch Brothers as its bassist. Years later, we travel around the country while I’m opening for his band, playing chess over coffee, getting lost on long walks in unfamiliar cities, talking endlessly about music. He is a one of the most supremely gifted bass players of our time.

2009 - Holcombe Waller and I are set up on a West Coast co-bill tour by a friend who warns me that Holcombe is extremely flamboyant. I write to Holcombe, and in a postscript, mention—sort of in jest, sort of not—that I’m 18% gay. He writes back, “I’ve worked with less.” A friendship is born. Need help understanding obscure financial instruments or fledgling cryptocurrencies? Ask Holcombe. Need a quick tutorial on the history of energy policy in the Northwest? Ask Holcombe. Need the most sublime falsetto (but also booming bass-baritone) you’ve ever heard? Ask Holcombe. Happily, we now live less than a mile from one another in Northeast Portland. Holcombe, can I borrow some sugar??

2010 (part one) - I’m playing a gig in upstate New York accompanied by a string quartet. At soundcheck, one of the violinists mentions that she “writes a little music, too.” Next thing I know, that kind and quiet musician—Caroline Shaw—has won the Pulitzer Prize. Over the years, we email with eccentric frequency about Lunchables (can’t remember how that one started), and have occasionally appeared together in concert. What I admire most about Caroline is the absolute honesty of her music. Many of us work for years building up artifice, then tearing it down. Not Caro: she knows, and seems always to have known, who she is. When I first heard her overdubs for the record, I cried.

2010 (part two) - Casey Foubert and I have known each other for a few years when he begins to mix my second album, Where are the Arms. Working on that record reveals to me the uncanny depth of Casey’s musical knowledge, spanning, as it does, obscure 60’s piano-driven folk-pop to free jazz. One of the most versatile and multivalent artists I’ve ever encountered, Casey is the only musician who has played on all of my records (with the exception of Book of Travelers, which is just me). He’s also a profoundly curious person, and a super generous spirit. He now lives with his family in rural Illinois, and I love that there’s a bit of that energy on this album.

2011 - It’s a dark and dreary evening in Peterborough, NH, when I find myself sitting at the piano in a little cabin, singing standards with a young woman named Amelia Meath. We keep in touch here and there, and then a few years later, I hear a band called Sylvan Esso and think, that voice sounds familiar! Over the last few years, Amelia and I have had long, deep phone calls about everything from literature to TikTok to systemic racism to the music biz. She encouraged me, while we were working on “Linda & Stuart,” to embrace the cognitive dissonance between the cheerful groove and the sense of grief that pervades the lyric.

2014 (part one) - Driving from the Denver Airport, Chris Morrissey tells me that he does a great BBC newscaster impression. I immediately try to one-up him. (Mine is better.) Every year on his birthday, to commemorate my small victory of superior British dialect, I leave Chris a three-minute voicemail in a preposterous BBC voice. Chris is a complete musician, and a complete human. One of the things that drew me to him when we first met was how emotionally available he was. So glad he’s on this joint.

2014 (part two) - A recording studio in New Jersey. yMusic has a new cellist on the session. We get through one take of my arrangement of Beck’s “Mutilation Rag,” for the Song Reader album, and Gabriel Cabezas, maybe 22 years old, says, without a trace of attitude or ostentation, “oh, this is a twelve-tone row, right?” What a punk! One memorable night years later ends drunkenly at my house, where we cook both carbonara and cacio e pepe after a long conversation about how the best pasta sauces are emulsified using the cooking water.

2014 (part three) - I’m not sure that the classroom at the fancy private school in Laguna Beach, California, was where I first met Joseph Lorge, but it sticks out in my memory for some reason. He’s there with a friend of his, a songwriter, who performs two beautiful songs as part of a master class that I was giving. By 2017, Joseph has become indispensable to my process as a studio artist. He records and mixes Book of Travelers, and acts as mix engineer and house psychologist during this project. He is tall and shy, quietly hilarious, with a heart of gold. His ears and imagination are astonishing; without him, this record would not exist.

2015 - In the lobby of the newly opened Ordway Theatre in St. Paul, Minnesota, I am accosted by a blonde man with a cheerful face and intense eyes. “I have a question to ask you,” he says, betraying the slightest hint of a Northern European accent. “On your song ‘Charming Disease,’ from your album Where are the Arms, is it three clarinets or one claviola that appear suddenly in the second verse?” This was Pekka Kuusisto, a true magician of the violin, and one of my dearest friends. I have fond memories from 2019 (“the before times”) of walking down to the water—his house in Finland sits against the Baltic Sea—in nothing but towels, freezing our asses off before retreating to the warmth of his wood sauna, which I guess is what Finns do in February? When his violin enters halfway through the tune, I feel the chill of that numinous, Scandinavian wind insinuate itself into the harmonic field.

2016 (part one) - St. Paul, again! Sam Amidon and I have known each other for a decade by this point, but it’s over burritos at Chipotle that we bond for real, talking about our shared love of Herman Melville and obscure jazz records. If I’m reading a great book, Sam is often the first person I want to tell. In a world brimming with highly individualized voices, Sam’s artistry—from his singing voice to his banjo and fiddle playing—stands out for its idiosyncrasies and emotional depth.

2016 (part two) - On a tour bus somewhere in Montana, Andrew Bird and I get to talking about how folk and orchestral music can coexist. A few years later, we work closely on Time Is A Crooked Bow, a cycle I orchestrated comprising six of his songs. Getting to hear him sing every night was a real master class. Andrew has magnetic rock star energy, but he is also a kind, gentle, quiet and deeply thoughtful soul. And no one plucks the violin quite the way he does. When I wrote the riff he plays on “To Be American,” I knew it had to be him.

2017 - From time to time, I head uptown to hear the NY Philharmonic. One evening, I’m hypnotized by a sound—serene, expressive, otherworldly— emanating from from the principal clarinet chair. Eventually I muster the nerve to write to Anthony McGill and tell him what I huge fan I am. It’s thrilling when he tells me that he knows my music and would love to do something together. And now, at last, we have.

2019 - Nathalie Joachim sends me mixes of her album Fanm D’ayiti. It is so damn gorgeous. We’ve been casual acquaintances for five years at this point, but now I am *a fan*. Over the course of the pandemic, we talk more frequently, counseling each other about the various challenges of being an artist in these confounding times. She joins the Creative Alliance with the Oregon Symphony, where I serve as Creative Chair. This June, the Oregon Symphony will present the world premiere of an orchestral song cycle drawn from Nathalie’s album that made such an impression. The combination of Nathalie & Alex on the title track, along with Holcombe’s vocal feature, has me feeling that my cup truly runneth over.

Appendix A:

Tony Berg is a joyous contrarian whom I’ve known for a dozen years, during which time he has shown me only generosity of spirit, resources, and wisdom. He co-produced Book of Travelers (which we recorded at his old home studio in LA), and was an indispensable early sounding board for the songs on this album. And now he’s got a dog named Bing-Bong. How about that?

Having said all that, may I remind you that tour begins on Monday?

The workings of the music business are murkier than ever, but the bottom line is that even an art-house oasis like Nonesuch can’t afford to keep putting out interesting music if no one is paying for it. I’m so grateful to all of you for your continued support, and hope you’ll consider picking up a copy of the record in one format or another if you’ve not yet done so.

All my best, and hope to see you at a gig in the next few months,

Gabriel

#andrew bird#chris thile#caroline shaw#sylvan esso#anthony mcgill#pekka kuusisto#nathalie joachim#paul kowert#punch brothers#elizabeth and the catapult#ymusic#sam amidon#ted poor#chris morrissey#holcombe waller#alex sopp#gabriel cabezas#casey foubert#joseph lorge#nonesuch#new music#art song#song cycle#gabriel kahane

32 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Fiona Apple performs “Every Single Night” on Live from Here in 2017.

#fiona apple#live from here#chris thile#live music#madison cunningham#rich dworsky#paul kowert#ted poor#sean watkins#gabe witcher#music#video#2017

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pickles looking happy:

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

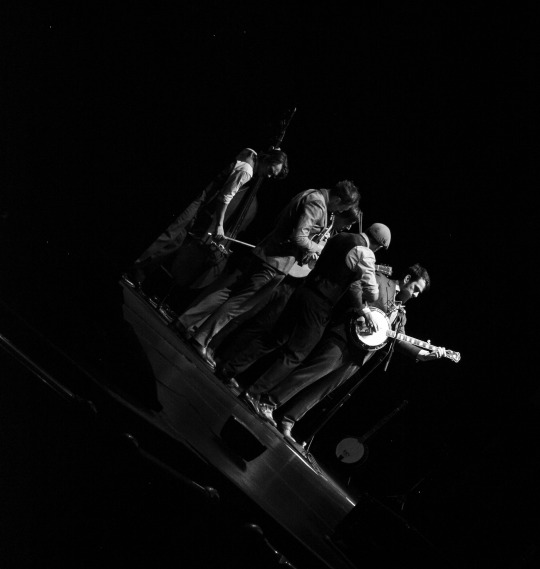

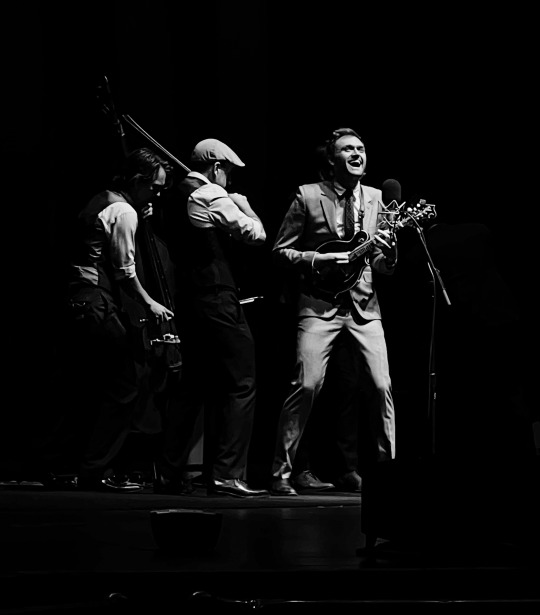

Punch Brothers’ Considerable Talents on Display at Beacon Theatre

Punch Brothers – Beacon Theatre – March 2, 2022

“Don’t judge a book by its cover” is a well-worn idiom we’ve all been told—there’s more than meets the eye. With the Punch Brothers, that’s certainly the case. To look at the quintet in front of a packed house at the Beacon Theatre on Wednesday night was to see a classic string band: mandolin, banjo, guitar, fiddle and upright bass all huddled around a single microphone in the center of the stage. And in fact, the first half of their set leaned heavily on classic material taken from their latest album, Hell on Church Street. That album is a reimagining of the late Tony Rice’s Church Street Blues album, which is itself a progressive take on bluegrass traditionals. So yes, the no-relation Brothers—Chris Thile on mandolin, Noam Pikelny on banjo, Chris Eldridge on guitar, Gabe Witcher on fiddle, and Paul Kowert on bass—were wearing the “cover” of a traditional bluegrass band. But by the time these songs got to the stage Wednesday night, the story they told went well beyond the picture on the cover.

The second half of the show was a masterful weaving of musical storylines and genre-defying compositions. “The Blind Leaving the Blind” was a full-on song suite, Thile leading the group through a downright Mozartian set of sections, dizzying complexities matched by the skill of the musicians. The instrumental “Jungle Bird” felt equally byzantine with little symphonic pieces interacting with one another, mind-enhancing solos on banjo, fiddle, guitar and mandolin that went beyond categorization but maintained a groove, nonetheless. “It’s All Part of the Plan” was more terrestrial, an indie-rock vibe with a prog-rock-on-strings twist, Thile’s vocals going mandolin staccato then violin drawn-out, Pikelny providing one of many impressive banjo solos midway through.

The set had a controlled inertia as songs bled from one into the next, the band orbiting around the single microphone, creating and then manipulating the dynamics of volume and tempo as a single unit. The closing pair of “The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald,” one of the covers-of-a-cover-of-a-cover tracks from the album, and “Rye Whiskey,” a crowd-favorite Punch Brothers original, was an exercise in dynamics to the extreme, everyone in the audience on their feet, hooting along with the band by the end. The encore opened an instrumental hootenanny, “Watch ’at Breakdown,” Pikelny again combining progressive notions to the traditional banjo solo, Thile playing just one more of countless wow! mandolin solos throughout the night, and Eldridge saving his best for last, not quite channeling Tony Rice, but infused with his beyond-Americana spirit. The performance ended with “Julep,” the Punch Brothers at their best—singing about booze, all five instruments in a complicated, beautiful dance together, the whole concept of genre reduced to nothing, a book without a cover altogether. —A. Stein | @Neddyo

(Punch Brothers play the State Theatre in Portland, Maine, on Saturday.)

Photos courtesy of Maggie V. Miles | @Maggievmiles

#Aaron Stein#Beacon Theatre#Chris Eldridge#Chris Thile#Church Street Blues#Gabe Witcher#Hell on Church Street#Maggie V. Miles#Noam Pikelny#Paul Kowert#Photos#Punch Brothers#State Theatre#Tony Rice

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Composer/singer/songwriter Gabriel Kahane's new album, Magnificent Bird, is out now. On the album, Kahane chronicles the final month of a year spent off the internet, reveling in the tension between quiet, domestic concerns, and the roiling chaos of a nation and planet in crisis. "Deft, prose poem-like songs: an illuminating humanity is absolutely key," says Mojo. "A most eloquent exploration of our current lot." The San Francisco Chronicle calls it "a gorgeous, intimate collection ... glistening and magical." Among the many guest musicians are Sam Amidon, Punch Brothers' Chris Thile and Paul Kowert, Caroline Shaw, and Mountain Man's Amelia Meath. Gabriel Kahane tours the US starting Monday.

#gabriel kahane#magnificent bird#sam amidon#punch brothers#chris thile#paul kowert#caroline shaw#mountain man#amelia meath#nonesuch#nonesuch records

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Song Review: Willie Watson - “Real Love”

“Real Love” is a song of romantic love. But former Old Crow Medicine Show man Willie Watson also makes clear his love of music, with allusions to Woody Guthrie, Little Richard and others in the lyrics.

It’s a country ballad with high-powered players, including Punch Brother Paul Kowert on bass, former Punch Brother Gabe Witcher on piano, Benmont Tench on organ and Sami Braman on fiddle, helping to fashion the music. The track announces Watson’s forthcoming self-titled LP, produced by Witcher and Milk Carton Kid Kenneth Pattengale and due Sept. 13.

With six verses - the title appended to two of them - and no chorus, “Real Love” is Dylanesque in its construction. It’s a little long as it approaches six minutes, but, seeing as it’s a lead single, a radio edit might soon address that.

Grade card: Willie Watson - “Real Love” - B-

6/21/24

#Youtube#willie watson#old crow medicine show#real love#woody guthrie#little richard#punch brothers#paul kowert#gabe witcher#benmont tench#tom petty and the heartbreakers#sami braman#kenneth pattengale#milk carton kids#bob dylan

9 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Punch Brothers

- Passe pied -

(Claude Debussy)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gabriel Kahane Interview: Ethic of Love

Photo by Jason Quigley

BY JORDAN MAINZER

During a time when the only safe way for us to connect with each other was in the digital realm, Gabriel Kahane was offline.

In late 2019, the singer-songwriter and composter decided to run an experiment: spend a year away from the Internet and see what happens. Like many of us, Kahane was addicted to his phone, whether on social media, reading the news, or constantly taking in podcasts or records. He was curious to see how his life and maybe even his brain changed as a result of new habits. The curiosity didn’t come out of nowhere, either; Kahane had always been up for some sort of technology-less adventure of diaristic discovery, like the time he took an almost 10,000-mile train trek without his phone the day after Donald Trump was elected President, a journey that eventually make up his 2018 album Book of Travelers. Perhaps his Internet-less year would inspire another record.

We all know what happened in March 2020. A few days before the shit hit the fan with COVID, the then-NYC-based Kahane traveled to Portland for what was supposed to be one week. He never returned and now lives there. Despite being forced to lock down, Kahane for the most part stuck to his promise to himself to refrain from logging on. In the middle of spending time in a new city and finding composer work, he tried to write some songs about his perception of the world at large, an experience he told me over the phone last month was “paralyzing.” Finally, during his final month offline, Kahane started a new experiment: Write a new song every day. “It forced me to write about smaller, more modest things instead of attempting to write the Great American Novel in every song,” he said. Finally, from that experiment, came Kahane’s new album Magnificent Bird, out March 25th on Nonesuch.

The 10-song album is very much a collaborative effort, and yes, Kahane is aware of the irony that it wouldn’t have been possible without the technology to record remotely during the pandemic. He doesn’t feel the need to justify the contradiction; after all, it’s better to be safe, and this was an easy way for Kahane to interact with some of his good friends who were busy with their own projects. Remarkably, many of the songs sound like they were recorded live, all musicians in the same room. Casey Foubert’s drums and Alexandra Sopp’s flutes and whistles bolster “Hot Pink Raingear”. Pekka Kuusisto’s gorgeous violin provide a contrast in depth to Kahane’s stark piano and spacey synthesizers on “The Hazelnut Tree”. Caroline Shaw provides harmonically perfect backing vocals on “To Be American”, which also features Americana and indie rock giants like Andrew Bird and Chris Thile and Paul Kowert of the Punch Brothers. And Sylvan Esso’s Amelia Meath duets with Kahane on “Linda & Stuart”, a tune about an elderly couple in isolation during COVID.

As you might expect, Magnificent Bird is riddled with references to Kahane’s year offline juxtaposed with a world filled with instant access to goods and services. “The trucks judder down city block / Young men bobble boxes full of almond milk and cell phone chargers / Packed up in the skin of dying trees / Baby, if that ain’t progress / Then what’s it gonna be?” Kahane sneers on “Hot Pink Raingear”. But he avoids self-righteousness with genuine reverence for the natural world. Whether paying tribute to his favorite arborous giant on “The Hazelnut Tree” or straightforwardly lamenting natural disasters on “To Be American”, Kahane recognizes that the physical world as exists in front of us is changing rapidly independent of any individual’s actions. He can, however, better himself by recognizing his faults. On the stunning title track, he admits to feelings of professional jealousy and explicitly references his Internet-less year as a means to avoid feeling envious. If the rest of us were spared from in-person FOMO during the pandemic, Kahane spared himself from, well, almost everything, and he’s critical of himself for doing so.

Magnificent Bird ends with “Sit Shiva”, which references one of the few times Kahane bent the rules, to attend a virtual shiva for his maternal grandmother. Over swirling electric guitars and synthesizers, acoustic guitars from Foubert, and backing vocals from Elizabeth Ziman, Kahane tries to make sense of something so absurd. “My mother, describing her mother / Fought back tears, it’s weird, I thought, / The intimacy of seeing someone try / Not to cry in close-up on a screen.” The interplay between the tangible sight of a tear and the virtual barrier of a screen has likely mucked up the emotions of similar experiences for a lot of other folks throughout the pandemic. You can’t help but think of folks who weren’t able to say goodbye to their loved ones in person because of overcrowded hospitals with contagious COVID patients. The image of a virtual shiva, Kahane unable to fully understand the experience but rolling with the punches, is a microcosm of what Kahane refers to as an “ethic of love.” While the idea comes from the Civil Rights Movement and leaders like Bayard Rustin and Martin Luther King Jr. persisting in the face of those who didn’t recognize their basic humanity, Kahane uses it to adopt a semblance of empathy, whether on a days-long train trip with total strangers or interacting via screens with loved ones.

Read the rest of my conversation with Kahane below, edited for length and clarity. Catch him at Constellation on May 21st.

Since I Left You: When I first listened to Magnificent Bird, what immediately stood out to me was that it was pretty short in terms of runtime, and each song was like a vignette. Were you going for that feel?

Gabriel Kahane: I can’t say I was going for that, but...there was more stream of consciousness in the lyric-writing, which is something that interests me. In a weird way, some of these songs have more of a journey, even though they’re really short, than some songs I’ve written in the past that drop you into a moment and evoke a mood or a feeling. On earlier records, I’m using the three-minute song to tell a story that has a certain amount of plot. In these songs, there’s often some kind of psychological movement that happens where I start in one place and end up somewhere else. I think that’s a function of the diaristic writing process and coaxing these free-writes into lyrics.

These songs are definitely vignettes of my life here, and the world creeps in along the edges. There was also a deliberate attempt to reset after writing a big orchestral piece--emergency shelter intake form, a deep dive into inequality through housing issues and homelessness--around the release of my last record. I was running the risk of being pigeonholed as the “issues, ideological composer guy” but also feeling that there’s a real danger in the notion that beauty for beauty’s sake is a luxury or a privilege, when in fact, I think quite the opposite. That notion is kind of classist. There’s a great essay by the poet and feminist Audrey Lorde called Poetry is Not a Luxury that I had been thinking about a lot in terms of who has access to what kind of art. In a time as divided as the one that we’re living in, we’re so often closed off to each other’s experience, it feels like there’s something kind of radical and quite political in reaching someone’s heart. There’s a weird way in which the movement towards writing about domestic life, which seems anti-political, feels really political to me.

SILY: I’m reminded of the New York Times going into Midwest diners trying to find real America. It’s through such an Internet lens, whereas your project seems more genuine.

GK: It’s funny you mention that, because that sort of “man in the street,” the journalistic nickname for that kind of reporting of, “Let’s go into the diner and interview people” is kind of what was happening with [Book of Travelers] and the election in 2016. This is the antithesis of that.

SILY: You write on Magnificent Bird about learning about news through the newspaper, without the immediacy of the Internet. I read that you still don’t really use your smartphone. What do you still use the Internet for, and what do you not use it for that you used to use it for?

GK: The biggest practical shift is that I got rid of my smartphone. That was partly out of self-preservation, because I was pretty addicted to it, and some of those addictive tendencies have returned. I’m posting very little to social media--maybe once or twice a month--but I’m still looking at it, which actually feels worse. I feel like I need to be completely off of it or give in. I’m still mostly getting my news from the newspaper and radio. One of the big things I was reminded of in my time offline was that even the 24-hour news cycle is a construct. We talked about the Twitter news cycle being fake and constantly self-correcting as things that are reported turn out to be untrue. But as my news intake slowed down to at least once a day, I started to see what was being reported on a 24-hour cycle was even different [than the day before], particularly during the final year of the Trump administration. There was a lot of palace intrigue, stuff that’s not really worth anyone’s time to read about. Nothing to do with policy or the quality of anyone’s life, just salacious reporting about the disrepair and disfunction. There is a whole kind of genre of journalism that’s, “Let’s take you behind the scenes of what’s happening in Washington,” and I now have very little tolerance for that.

The signal moment for me in thinking about the news specifically was that I didn’t look at any online news for the first 10 months of my time offline, and the first time that I broke my rule--there were moments throughout where I broke the rules or bent the rules for various reasons where I felt like I didn’t have another option--was when there were horrific wildfires within 30 miles of Portland. I started looking at the local news online to look at the air quality and whether the fires were going to burn our house down. What was humbling about that was, in retrospect, how much I obsessively kept up with news that had very little impact on my life. I was reading it as much as entertainment even though I was telling myself for a long time that it was a sort of activism, even though it was just armchair activism, so not activism at all. That was a big shift for me in recognizing the advantages that I have in my life culturally and economically have made it such that I’ve often been at a remove from the most destructive things government is doing because they don’t have an impact on me. They obviously have an impact on people I care about, like everyone.

The other big shift, which was more psychological than having to do with specific technologies, was realizing that when I had a smartphone, I always felt like I had to be taking something in. I was always in input mode, listening to a podcast or the record or the news. Less and less was I able to just be with my thoughts and imagination. It took several months of being offline to realize I was trying to do that even when off the Internet, trying to find ways to constantly feed myself information. Even with reading, I realized I needed to spend some time not taking things in. We’re conditioned because there’s such a glut of information, and all these different companies and interests trying to buy a slice of our attention, to resist that is a project unto itself.

SILY: Like when you sing on “The Hazelnut Tree”, “The sun on the hazelnut tree / That’s something I still believe.”

GK: That was the first song I wrote for this project, on October 1st. There’s also a line in that song, “That’s more information than I need.” There’s also something going on there, feeling like information overload. In one way, it’s a privilege to step back from that, but in another sense, part of what plagues American politics is that a huge swath of the electorate is working 80 hours a week for basically slave wages and can’t pay attention to the news because they’re trying to make ends meet. I was never tuning things out. I’m inherently too interested in the world and the idea of democracy that I would never be able to check out. But there’s a question of how granular you have to get in the degree to which you’re paying attention in order to be an informed citizen.

SILY: I like the line on “To Be American”, “One criminal’s soft defeat can’t change the fact that we’re broken.” Are you basically saying, “Trump being removed isn’t going to fix everything?”

GK: It’s funny because I wrote that song in the second week of October. The reason I took the train trip after the election in 2016 is the feeling that Trump was more a symptom of systemic rot in the country than the problem. There are so many ways of talking about that. The challenges that we face are so much greater. Obviously, one person can do a huge amount of damage to the public trust, but his genius was tapping into a real kind of rage and twisting it in the ugliest possible direction. He’s not the only aspiring authoritarian: We’re seeing it all around Europe and in Brazil.

I really try to not editorialize in my song, and that line is a little bit where I’m editorializing a bit. [laughs] My reading that sounds a little Hallmarky is that there’s not a lot of love in our politics and in our organizing right now. I spent a good amount of time when I was offline reading work by the leaders of the 1960s Civil Rights movement, and one of the things I find the most moving and inspiring about people like Bayard Rustin, Martin Luther King, James Baldwin, and Audrey Lorde later is how committed they were to an ethic of love in the space of people who didn’t recognize their basic humanity. That song is both about nostalgia and critical of nostalgia. And with that line, we can see quite clearly that a year and a half later, we’re mired in a certain set of problems, and some have certainly continued.

SILY: On the opening track “We Are the Saints”, when you sing, “It’s mourning in America,” I noticed on the lyrics sheet it was spelled “m-o-u-r-n-i-n-g.” Were you trying to be ambiguous? It’s very likely folks listening won’t have the lyrics sheet.

GK: “Morning in America” was a Reagan slogan. If you hear it as “morning,” it’s deeply ironic, the Reagan callback but with a sneer. So it can be either way. Does the Reagan version of that phrase have any resonance for you? I weirdly know that phrase because it was referenced in a musical I worked on when I was in my 20s, and then I went back and watched the Reagan commercials.

SILY: I know the context, and as much as political ads are inherently cringeworthy, for someone like Reagan whose policies were so cruel, that slogan is especially vomit-inducing.

GK: [laughs] But yes, ambiguity is baked into it on purpose.

SILY: There’s further irony on the album, like that you spent a year off the Internet but it was made with the help of the Internet, as you were able to collaborate digitally. Track 2, “Hot Pink Raingear”, is one where I listened to it and thought, “This sounds like everybody’s in the room together.” On a lot of records made over the pandemic that were made remotely, the artists seemed to lean into the digital collaboration, whereas others were trying to still make it sound like it was recorded live. Where were you on that spectrum?

GK: The paradox of making a record with all these people is that I planned to make a really sparse record. For the first time living out here in Portland, I put together a modest recording studio in my backyard, what had previously been a woodshop, with a piano and some microphones. I had planned to record more of the 30 songs, and there are some I recorded but left off the record, but it focused around these 10 songs that felt like they had an arc to them. Initially, my thinking was that I would bring in one person per song and feature one friend/collaborator. I realized afterwards that everyone who I asked to play on the record was someone I really loved as a person. Even though I was talking on the phone offline, it became really isolating as the pandemic began, both because of lockdown but also because everyone was so online all the time, that people were too exhausted to talk on the phone. I spent a lot of time looking inward, meditative, and alone. When I was done, making this record was a good excuse to be in touch with my friends, some of whom can be hard to pin down. I guess I was trying to make it feel as natural as possible.

It’s funny you mention “Hot Pink Raingear”, because I think we made three versions of it with totally different arrangements and instrumentation. It was the last piece of the puzzle to figure out. It’s the most tortured song. It makes me happy that to you it sounded like people in a room. Ted Poor, one of the two drummers on the song, had a lot to do with it. He has an amazing way of playing around a click track. One of the things that can make recording remotely very frustrating is the dominance of the click track, and it can suck the life out of things. Ted has this way of ignoring the click track, being very much in time but also playing around it. There’s something about the energy of his drumming that’s very wonderful. My friend Casey, an amazing multi-instrumentalist who has played on every one of my records and actually lives in Galesburg, Illinois, figured out a different drum idea for the chorus. That track is mostly Ted and Casey and me playing everything.

It never would have occurred to me to lean into sounding remote, and none of the mixing does so. If one were to come away with that impression, it’s not on purpose. [laughs] The first and fifth song [“Chemex”] are the ones that are basically just me, and those are very much studio jams of me trying to create a world by myself. Everything else is some version of trying to emulate people in a room.

SILY: Is the record meant to be listened to on vinyl?

GK: Yeah. I guess I started maybe two records ago, with The Ambassador in 2014, [thinking about] the experience of each side. I’d say yes in the sense that this album more than any other I’ve made feels like every song is in a really particular place. I wouldn’t want people to listen to it on shuffle. I think because it’s a short record, I love the idea of people listening to it twice in a row. I do feel like the end of “Chemex” really feels like the end of the first side, and I was thinking about introducing the little bit of electronic texture as a way to prime the listener’s ear for the beginning of the second side [“Linda & Stuart”], which is a very different sonic world. In that sense, I love the idea of someone getting to the end of the first side and thinking, “I wonder what’s gonna happen now?” and then flipping it and saying, “Okay, we’re over here.” What’s the question or observation behind the question?

SILY: Just that the liner notes said “Side A/Side B” and that the track order started over in them.

GK: That’s a convention with my label, not an artistic choice. [laughs]

SILY: In the song “Linda & Stuart”, I’m curious about the line, “Linda tells me she’s taking a writing class / On the art of the short story, and I say, ‘Hey that’s great, ’cause / We all need a way to make sense of the world.’” Is that in a way the summary of the entire record?

GK: I think that’s for you to decide. [laughs] I will leave it at that. You’re my first interview on this album cycle, and I’m usually much cagier about lyrics. I’ve said more to you in your questions about lyrics than I normally do. My usual stock response is, “What do you think?” [laughs] The problem with an artist telling you what they think a lyric is about is it deprives you of your ability to make your own meaning or makes your own meaning compete with the artists’. I leave you to decide whether that’s the thesis statement of the album.

SILY: I think it is.

GK: To take a step back, it’s so important for the world that we have people who care about music enough to write about it, and I really believe in people who care about music enough to write about it to have autonomy. I also feel like once I’ve made something, it’s not mine anymore. I truly believe that the meaning you make around something is the relationship you have with it as a listener. I don’t know if I would have thought of that reading, but I really like it. [laughs]

SILY: When did you decide to name the record after the title track?

GK: That came very late. There were a couple different titles floating around, and I thought [Magnificent Bird] sounded good as a title. I feel like that song is perhaps the song I’ve written where I, as the narrator, come across in the least flattering light. On the one hand, professional jealousy is a common experience, but on the other hand, it’s an ugly feeling. The transparency of that speaks to what I was trying to achieve with the record. It’s also the only song on the record that explicitly alludes to my time offline.

SILY: You talk about how you’re partaking in your Internet-less year in order to avoid the shame of envy. It’s a very self-reflexive and self-critical part of the album.

GK: The thing that I like about that song is that it comes around to this place of generosity of spirit, putting a record on and trying to sing along to it. In a way, it connects back to the ethic of love and generosity, something I’ve struggled with myself but am always striving to be greater at. In that song, the narrator is both engaging in a shameful feeling of jealousy and coming out the other end in a slightly better place.

SILY: What’s the story behind the album art?

GK: John Gall is a really great book designer, the head of designer for [The Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group]. He’s done lots of covers for Nonesuch going back about two decades. I love to read, and I love book covers. The last three records I made have had these really brooding covers, and the last two were these full-bleed, emotionally dark photographs. He and I had one conversation, and I said I was interested in something with an inset and a collage--he does a lot of collage-based work in his book design--and as a reader and wannabe literary guy, I kind of like that the cover feels adjacent to a book cover as much as a record cover. I don’t want to be too specific. He’s left a lot of Easter eggs in the cover art, and I’ll leave them there for listeners to decide what’s happening.

SILY: Anything you’ve been listening to, watching, or reading lately that’s caught your attention?

GK: There’s a book I’ve been proselytizing everywhere I can called How To Blow Up A Pipeline by historian and activist Andreas Malm, a short and interesting book about the limitations of nonviolent action. He’s not necessarily advocating that people blow up pipelines, but looking at what other nonviolent movements have used to get their agenda past the finish line, from Civil Rights to Women’s Suffrage. The Gift by Lewis Hyde has really rocked my world. It was initially published in 1983 and was for me a life-changing book about how to be creative and hold on to the center of your practice while living in capitalism, something I’ve been thinking about over the past year. My decision to go offline had a lot to do with feeling like so much of our digital world is the most distilled expression of capitalism. If the point of capitalism is to take friction out of transactions, the smartphone is the ultimate frictionless device, whether we’re communicating, buying stuff, or selling stuff. I’ve increasingly found myself uncomfortable with that premise. The Gift was a really helpful way for me to orient myself, because it’s hard to resist desire and wanting to be famous. It’s kind of what’s going on in the title track, working through that stuff.

youtube

#interviews#gabriel kahane#nonesuch#pekka kuusisto#caroline shaw#amelia meath#elizabeth ziman#constellation chicago#ted poor#magnificent bird#jason quigley#book of travelers#casey foubert#alexandra sopp#andrew bird#chris thile#punch brothers#paul kowert#sylvan esso#bayard rustin#martin luther king jr.#nonesuch records#constellation#emergency shelter intake form#audrey lorde#poetry is not a luxury#james baldwin#the ambassador#john gall#lewis hyde

0 notes

Text

I WILL NEVER NOT TALK ABOUT HOW MUCH I LOVE THE PUNCH BROTHERS

#THEIR NEW ALBUM IS NO EXCEPTION#HOLY SHIT THERE IS NOT A SINGLE MISS#AND IT JUST GETS BETTER THE MORE I LISTEN#punch brothers#hell on church street#chris thile#gabe witcher#paul kowert#chris eldridge#Noam pikelny#I don’t know how they do it#i can only hope to be that musically gifted one day

1 note

·

View note

Audio

“Send My Love (To Your New Lover)”

Original by Adele

Covered by I’m With Her feat. Paul Kowert

8 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

American Tune

Chris Thile, the Preservation Hall Jazz Band, Margaret Glaspy, Rachael Price, Rich Dworsky, Matt Chamberlain, Brittany Haas, Paul Kowert, and Sean Watkins

A Prairie Home Companion

#A Prairie Home Companion#Chris Thile#the Preservation Hall Jazz Band#Margaret Glaspy#Rachael Price#Rich Dworsky#Matt Chamberlain#Brittany Haas#Paul Kowert#Sean Watkins#Paul Simon#America#American Tune#Music#Video

15 notes

·

View notes