#Robyn Creswell

Text

I feel the desire to pray. I don’t know whom to address.

— Iman Mersal, from "As if the world were missing a blue window," The Threshold, tr. Robyn Creswell

#quote#iman mersal#poetry#the threshold#out of my collection#As if the world were missing a blue window#robyn creswell

705 notes

·

View notes

Quote

English can do wryness, but Arabic verse has musical possibilities that I don’t think contemporary poetry in English can really capture. Because written Arabic is a literary language—it isn’t spoken except in formal situations—it’s possible to be grandly symphonic or virtuosically lyrical in a way that’s hard to imagine in English. You’d have to be a Tennyson to match the musical effects in Darwish’s late poetry, for example. But of course trying to be Tennysonian would be fatal.

With Iman [Mersal] the difficulty for an English translator is different, and I would say more manageable. In a poem about her father, she wonders whether he might have disliked her “unmusical poems.” I don’t think they’re actually unmusical (I don’t think Iman does either), but their rhythms and cadences and sounds have a lot in common with the spoken language. She writes in fusha, sometimes called “standard” Arabic, but her style shares many features of the vernacular: she doesn’t use ten-dollar words, her syntax is typically straightforward, economy is a virtue. She also uses tonal effects—sarcasm, for example—that we tend to associate with speech.

We talked a lot about “A grave I’m about to dig.” I’m still not sure Iman likes my choice of “diagonal” for the Arabic ma’ilan, to describe the way a bird falling out of the sky might appear to an observer on the ground (but that’s how I think of Iman: she sees things at a slant). The last phrase of the poem, “were it not for the sneakers on my feet” is a typical moment of self-deprecation, a comedy of casualness. There are no feet in the Arabic original, however, which just says “were it not for my sneakers” (or, more literally, “my sports shoes”). I thought adding the phrase “on my feet” was needed, both for musical reasons and because it suggests a pun that isn’t available in Arabic, where verse meters aren’t called feet. For me, Iman’s (musical, metrical) feet really do wear sneakers: they’re quick and agile, casual but spiffy. They’re what we wear today.

Robyn Creswell, from “Interview with Robyn Creswell”, published in Four Way Review, 15 September 2022

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

from “Elegy for the Times” // Adonis

The wind is against us and the ash of war covers the earth. We see our spirit flash on a razor blade, a helmet’s curve. The brackish springs of autumn salt our wounds.

Doom drags at history’s face—our history needled with terror, a meadow of wild thorns.

In what salt rivers will we wash this story, stale with the smell of old maids and widows back from the hajj, our history stained with the sweat of dervishes’ loins, its springtime a feast for locusts?

Night thickens and a new day crawls forth over dead sparrows. The door rattles but doesn’t open. We cry out and dream of weeping and the eyes have no tears.

My country is a woman in heat, a bridge of lusts. Mercenaries cross her, applauded by the massing sands. From distant balconies we see what there is to see: animals slaughtered on the graves of children; smoking censers for holy saints; the black rock of tombstones. The fields are full of bones and vultures. The heroic statues soft cadavers.

So we go, chests bared to the sea. Old laments sleep under our tongues and our words have no heirs.

We reach out for alien islands, scenting a virgin strangeness in the sea’s abyss. We hear the sorrowful moan of our ships at port. Sorrow: a new moon rising, evil in its infancy. Rivers issue into the dead sea, where the night births weddings of sea scum and sand, locusts and sand.

So we go and fear scythes us down, crying out on muddy slopes. The earth bleeds all around us. The sea is a green wall.

—Translated from the Arabic by Robyn Creswell

#poetry#Adonis#Ali Ahmad Said Esber#Syrian poetry#Arabic poetry#Robyn Creswell#the sea#war#history#terror#violence#pacifist poetry#anti-war poetry

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

NTA's 2023 Poetry Longlist Includes Iman Mersal's 'The Threshold,' tr. Robyn Creswell, and Vénus Khoury-Ghata's 'The Water People,' tr. Marilyn Hacker

SEPTEMBER 1, 2023 — The American Literary Translators Association (ALTA) today announced the longlists for the 2023 National Translation Awards (NTA) in Poetry and Prose.

Although there were no Arab or Arabic titles on this year’s prose longlist, there were two on the 12-book poetry longlist: Iman Mersal’s The Threshold, translated from Arabic by Robyn Creswell, and Vénus Khoury-Ghata’s The Water…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

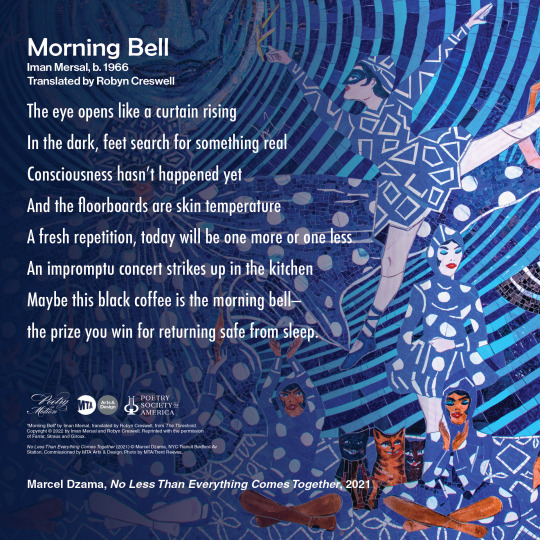

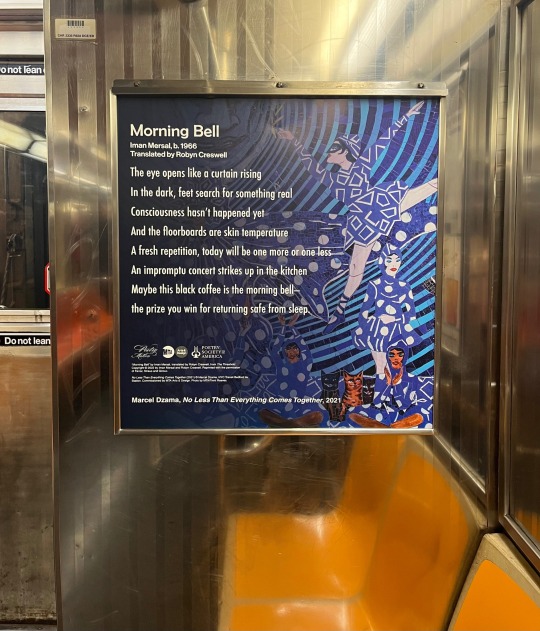

Sharing a new addition to the Poetry in Motion collection!

Selected in collaboration with @poetrysociety, “Morning Bell” by Iman Mersal is set with imagery from Marcel Dzama’s mosaic “No Less Than Everything Comes Together” (2021) at Bedford Av (L) station. Dzama’s artwork, containing curious characters set in a palette of nighttime blues, was inspired by Walt Whitman’s iconic poem “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry.” A beautiful coincidence unbeknownst to the artist at the time, Whitman’s poem was part of the Poetry in Motion program’s pilot release in 1992.

Find “Morning Bell” throughout the transit system, presented in print and on digital screens throughout the subway, and on digital screens in commuter rail cars and stations.

"Morning Bell" by Iman Mersal, translated by Robyn Creswell, from The Threshold. Copyright © 2022 by Iman Mersal and Robyn Creswell. Reprinted with the permission of Farrar, Straus and Giroux. No Less Than Everything Comes Together (2021) © Marcel Dzama, NYC Transit Bedford Av Station.

Commissioned by MTA Arts & Design. Photo by MTA/Trent Reeves.

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

books of 2023

A Guest in the House by Emily Carroll

A Series of Unfortunate Events 5-13 by Lemony Snicket

Abbott: 1973

Alone in Space: A Collection by Tillie Walden

Aquaman: The Becoming

Aquamen (2022)

Arkham City: The Order of the World

Batgirl (2000)

Bylines In Blood

Cuckoos Three by Cassandra Jean, Mosskat

Crush & Lobo

The Daughters of Ys by M.T. Anderson, Jo Rioux

DC Pride: Tim Drake Special

Elektra (2014)

The Forest by Thomas Ott

Galaxy: The Prettiest Star by Jadzia Axelrod, Jess Taylor

Gimmick! by Youzaburou Kanari

House of Slaughter, Volumes 1-2

The Illustrator by Steven Heller, Julius Wiedemann

Island of the Blue Dolphins by Scott O'Dell

Jessica Jones (2016)

Jessica Jones: Blind Spot

Justice League: A League of One

The Liminal Zone by Junji Ito

Men I Trust by Tommi Parrish

Metro Survive by Yuki Fujisawa

Midnighter (2016)

Mister Miracle: The Great Escape by Varian Johnson, Daniel Isles

Moon Knight (2011)

More is More is More: Today's Maximalist Interiors by Carl Dellatore

Ms. Marvel (2014), Volumes 1-2

Natsume's Book of Friends, Volumes 12-28 by Yuki Midorikawa

Nimona by N.D. Stevenson

Nubia: Real One by L.L. MicKenney, Robyn Smith

Power Girl Returns

Pretty Deadly

The Prince and the Dressmaker by Jen Wang

Rogue Sun, Volume 2

Rough Terrain by Annbeth Albert

Run Away With Me, Girl by Battan

Runaways (2003-2008)

SFSX (Safe Sex)

Silver Diamond, Volumes 1-9 by Shiho Sugiura

Sins of the Black Flamingo

Soulless: The Manga by Gail Carringer

Spider-Man/Deadpool, Volumes 1-6

The Sprite and the Gardener by Rii Abrego, Joe Whitt

Still Life: Contemporary Paintings by Amber Creswell Bell

Storm (2014)

Street Unicorns: Extravagant Fashion Photography From NYC Streets and Beyond by Robbie Quinn

Ultimate Comics Spider-Man (2011)

Until I Meet My Husband by Ryounosuke Nanasaki

Wakanda

Watercolor: Paintings of Contemporary Artists

What Did You Eat Yesterday? Volume 19 by Fumi Yoshinaga

Wheels Up by Annabeth Albert

The Well by Jake Wyett, Choo

The Wendy Project by Melissa Jane Osborne, Veronica Fish

The Wild Orphan by Robert Froman

Wonder Woman: Black & Gold

X-Men (2013)

Yellowface by R.F. Kuang

You Brought Me the Ocean by Alex Sanchez, Julie Maroh

Young Avengers (2005-2012)

#queerical reads#bold means strongly recommended#some of these were re-reads#i didnt include the books i finished but didnt like

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Then What Happened?" by Robyn Creswell (on The Annotated Arabian Nights: Tales form 1,001 Nights, translated by Yasmine Seale, edited by Paulo Lemos Horta)

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

‘Free Speech Is Hard Work’

One stumbles upon insight gold. Here’s a line from the title poem of Egyptian poet Iman Mersal’s book The Threshold:

One long-serving intellectual screamed at his friend / When I’m talking about democracy / you shut the hell up.

It’s quoted here in the blog ArabLit & ArabLit Quarterly. The book’s translator from Arabic to English is Robyn Creswell. As wicked captures do, Mersal’s verse struck…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

A Celebration

by Iman Mersal

The thread of the story fell to the ground, so I went down on my hands and knees to hunt for it. This was at one of those patriotic celebrations, and all I saw were imported shoes and jackboots.

Once, on the train, an Afghan woman who had never seen Afghanistan said to me, “Triumph is possible.” Is that a prophecy? I wanted to ask. But my Persian was straight from a beginner’s textbook and she looked, while listening to me, as though she were picking through a wardrobe whose owner had died in a fire.

Let’s assume the people arrived en masse at the square. Let’s assume the people is not a dirty word and that we know the meaning of the phrase en masse. Then how did all these police dogs get here? Who fitted them with parti-colored masks? More important, where is the line between flags and lingerie, anthems and anathemas, God and his creations—the ones who pay taxes and walk on earth?

Celebration. As if I’d never said the word before. As if it came from a Greek lexicon in which the victorious Spartans march home with Persian blood still wet on their spears and shields.

Perhaps there was no train, no prophecy, no Afghan woman sitting across from me for two hours. At times, for his own amusement, God leads our memories astray. What I can say is that from down here, among the shoes and jackboots, I’ll never know for certain who triumphed over whom.

—Translated from Arabic by Robyn Creswell

via Paris Review, Issue no. 197 (Summer 2011)

#celebration#iran#iman mersal#imersal#iman#mersal#robyn creswell#rcreswell#robyn#creswell#thread#story#hands#knees#celebrate#patriot#afghanistan#persian#life#death#fire#square#god#creator#pay#tax#earth#train#prophecy#women

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Elias Khoury, The Art of Fiction No. 233

INTERVIEWER: How do you continue to write novels when every day seems to bring news of some new atrocity or human calamity in your backyard?

KHOURY: I’ve lived my life under a state of near permanent war. I was born in 1948 and have vivid memories of the “small” civil war of 1958. The defeat of 1967 brought me to political consciousness. And I began writing novels during the first years of our major civil war. I try not to write about war, but to write from within it. One has to write through these calamities and atrocities. I think it’s good practice—for writing and for living—but it isn’t ever easy. On the other hand, I suppose that writing is always a mixture of torture and delight. This was something I tried to explore in Yalo, whose protagonist is tortured and then forced by his inquisitors to write a confession. So writing is both a torturer’s technique and a means of liberation—a way of understanding yourself. By writing, you transform reality into material for the imagination.

- Elias Khoury, The Art of Fiction No. 233, Interviewed by Robyn Creswell for the Paris Review, Issue 220, Spring 2017.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’m a fair-minded person.

I’ll give you more than half the air in the room

so long as you see me for what I am.

— Iman Mersal, from "Amina," The Threshold, tr. Robyn Creswell

845 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Sara Elkamel: Iman [Mersal]’s poems typically take on different forms as well as registers–at times indulging in the lyric, and at times sacrificing it for the sake of a more restrained, almost academic language. She recently told me that she believes poems don’t have “forms” as much as “personalities.” Do you find you have to “get to know” a poem of hers before you approach a translation? If so, what does that process look like?

Robin Creswell: I think translation is the process—or a process—of getting to know a poem. My first versions tend to be awkward, formal, overly reliant on obvious equivalents (something like the French faux amis). That isn’t so different from the way one talks with a new acquaintance: conventions can be useful. It’s only later, and gradually, that you begin to see what makes the poem—if it’s a good poem—worth spending time with.

Robyn Creswell, from “Interview with Robyn Creswell”, published in Four Way Review, 15 September 2022

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Idea of Home // Iman Mersal

I sold my earrings at the gold store to buy a silver ring in the market. I swapped that for old ink and a black notebook. This was before I forgot my pages on the seat of a train that was supposed to take me home. Whenever I arrived in a city, I felt my home was in a different one.

Olga says, without my having told her any of this, “Your home is never really home until you sell it. Then you discover all the things you could do with the garden and the large rooms—like you’re seeing it through the eyes of a broker. You stored all your nightmares in the attic, now you have to pack them in a suitcase or two.” Olga falls silent, then suddenly smiles, a monarch among her subjects, there in the kitchen between her coffee machine and a window with a view of flowers.

Olga’s husband wasn’t there to witness this queenly speech. Maybe that’s why he still thinks the house will be a loyal friend even when he loses his sight—a house whose foundations will hold steady, whose stairs will mercifully protect him from falls in the dark.

I’m digging around for a key that always gets lost in the bottom of my handbag, here where neither Olga nor her husband can see me, training myself in reality so I can give up the idea of home.

Every time you go back home with the dirt of the world under your nails, you stuff everything you could carry with you into its closets. But you refuse to define home as the resting place of junk, as a place where these dead things were once confused with hope. Let home be that place where you never notice the bad lighting, let it be a wall whose cracks keep growing until one day you take them for doors.

translated from the Arabic by Robyn Creswell

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Iman Mersal & Robyn Creswell Make 2023 Griffin Poetry Prize Longlist with 'The Threshold'

MARCH 15, 2023 — Organizers of the Griffin Poetry Prize — one of the world’s biggest international poetry prizes — have announced this year’s ten-book longlist. Among them was Egyptian poet Iman Mersal’s The Threshold, beautifully translated by Robyn Creswell.

The prize, which previously had been split into Canadian and International prizes, has now combined into one overall International Prize,…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

A Massive Mother’s Day Discount On All Thames & Hudson Books!

A Massive Mother’s Day Discount On All Thames & Hudson Books!

Mother's Day Must Haves

by Lucy Feagins, Editor

From Left: Kerstin Thompson Architects, Encompassing people & place by Leon van Schail ($59.99), Go Lightly by Nina Karnikowski ($29.99), Art Design Life by Ken Done + Amber Creswell Bell ($80), Painting the Ancient Land of Australia by Philip Hughes ($80), Utsuwa, Japanese Objects for Everyday Use by Kylie Johnson and Tiffany Johnson ($59.99), Kaffe Fassett in the Studio by Kaffe Fassett ($59.99), A Room Of Her Own by Robyn Lea ($65), Field, Flower, Vase by Chelsea Fuss ($45). Photo – Eve Wilson for The Design Files. Styling – Lucy Feagins. Art Direction – Annie Portelli.

When it comes to beautiful, inspiring, gift-worthy books, you can’t go past Australian publisher Thames & Hudson. And this Mother’s Day, they’re offering TDF readers a massive 30% site-wide discount!

The offer applies across all Thames & Hudson Australia titles, but we’ve got a few faves on our wishlist for the design-savvy mums out there.

Mums who love to have a little interiors stickybeak will like A Room Of Her Own, by Australian photographer, author and director Robyn Lea, who takes readers inside the dazzling lives and homes of some seriously fabulous creative ladies across the globe.

Jungalow: Decorate Wild by Justina Blakeney promises interior design advice for creating bright and bold spaces that break all the rules, and on the other end of the décor spectrum, the Principles of Pretty Rooms by American designer Phoebe Hall offers tried and true decorating tips and strategies for creating timeless, chic interiors.

For the nature-loving mums out there, The Garden State explores some of the most beautiful private gardens in Victoria, while Field, Flower, Vase is a practical guide to creating seasonal arrangements with foraged flora.

As our passion for travel is rekindled after a year of staying close to home, Go Lightly by Australian writer Nina Karnikowski is a useful handbook for how to travel without hurting the planet. And while we’re on sustainability, Pre-Fab Living by Avi Freedman is an excellent resource for innovative homes that cost less – economically and environmentally!

Thames & Hudson Mother’s Day Must Haves offer:

30% off all products site-wide when you use the discount code TDF30 at the Thames & Hudson Australia online store checkout. Offer ends Wednesday 5th May, 2021 while stocks last. Purchase by Monday 3rd May, 2021 for guaranteed delivery before Mother’s Day to Australian addresses. Discount code available to Australian and New Zealand addresses only, excluding PO boxes.

0 notes

Text

Emma Ramadan es una traductora literaria de poesía y prosa, proveniente de Francia, el Medio Oriente y Norteamérica. Recibió la beca Fulbright de traducción otorgada por NEA, el premio PEN/Heim y en 2018 el premio Albertine. Sus traducciones incluyen obras de Anna Garréta como Sphinx y Not One day; Pretty Things de Viginie Despentes, The Shutters de Ahamed Bouanani y My Part Of Her de Javad Dhavahery. Recide en Providence, Rhode Island en donde es co-propietaria del la librería/bar Riffarff.

Identidad, historia cultural y el poder del lenguaje.

La traductora literaria Emma Ramadam comparte las complejidades de crecer en un hogar multilingüe, el valor cultural de una buena traducción, y cómo nuestra propio entendimiento del ser se encuentra envuelto en el lenguaje.

¿Creciste en un hogar multilingüe?

La lengua materna de mi madre es el inglés. Es británica. Pero también habla un francés fluido, y al parecer también habla alemán, aunque nunca la he escuchado hablarlo. La lengua materna de mi padre es el árabe, luego el francés y luego el inglés. Mis padres sólo nos hablaban a mi hermano y a mí en inglés. Toda la familia de mi padre vivía in el sur de California con nosotros. Cada fin de semana hacíamos una gran reunión familiar en casa de mis abuelos, acompañada de mucha comida libanesa y en la cual había demasiado árabe y demasiada transición entre el árabe, el inglés y el francés. Pero yo sólo hablaba inglés.

¿Entonces no entendías lo que decían en árabe?

En absoluto. Probablemente había algo con respecto a que mi mamá no pudiera entender árabe, por lo que mi papá no quería que tuviera un idioma con él que la excluyera. Pero no sé si él quiso alguna vez enseñarme árabe. Nunca me habló de Líbano. Mis padres hablaban francés y pasamos mucho tiempo en Francia. Este era el idioma que mis padres tenían sin mí y mi hermano, así que cuando querían hablar de algo enfrente de nosotros, tenían su lenguaje secreto. En cuanto pudo, mi hermano empezó a aprender francés en la escuela y yo también. Queríamos poder entender y responder a lo que decían. Lo disfrutaba mucho, así que continué haciéndolo. Mi mamá hablaba muy bien francés y me ayudaba a practicar y con mi tarea. En algún punto, por ejemplo con mi trabajo de traducción, ya no fue capaz de ayudarme. Se hizo muy claro muy rápido que su francés no era un francés literario complejo. Comencé a hacerle preguntas de proyectos de traducción en los que estaba trabajando y me decía “no tengo idea.” En algún punto mi francés se volvió diferente al de mis padres.

¿Cuándo decidiste ser traductora?

Cuando estaba en la universidad. Estaba estudiando Literatura Comparada y la verdad no sabía qué hacer con eso. Sabía que me gustaban mucho los libros y me gustaba mucho leer, el francés y el lenguaje, pero en Brown no había tronco común y literalmente todo lo que hacía era tomar clases en donde leía y escribía ensayos acerca de los libros. Disfrutaba hacerlo, pero también se sentía súper insatisfactorio. No estaba interesada en convertir los libros en tarea, algo que estás diseccionando y analizando con el mero propósito de conseguir una A. Ese esquema le consumía la esencia que tenía para mí. Estaba compartiendo esto con alguien, y ella dijo, “¿no sabes que hay un área de traducción? Es un área de Composición literaria donde tomas talleres de escritura y clases de lingüística y básicamente usas tu amor por los libros y tu amor por el lenguaje para traducir y crear algo nuevo en inglés.” La traducción, para mí, era una manera de conectar con la literatura, en una manera satisfactoria y en la que no matas la magia de la literatura, sino que le das más vida. La idea sonaba increíble.

Estudié en Francia e intenté traducir por mi cuenta y luego regresé a Brown. Tan pronto como regresé, me cambié al área de traducción en Literatura Comparada. Tuve grandes mentores en Brown: Cole Swensen, Forrest Fander, Robyn Creswell. Después de graduarme, comencé inmediatamente la maestría en Traducción Cultural en la Universidad Americana de París, donde aprendí cómo ser consciente de lo que significa traducir de una cultora a otra, y de las disparidades entre culturas. Ese tipo de preguntas no se me habían preguntado en Brown, preguntas que no me habría forzado a pensar de haber intentado traducir por mi cuenta. Era perfecto porque estaba viviendo en un país franco parlante practicando más el idioma. Leíamos acerca de teoría de la traducción, teoría literaria y teoría cultural y participábamos en talleres. Formábamos parte, traducíamos libros. Teníamos un consejero. Sentía estar puliendo algo. Tenía la posibilidad de hablar mucho acerca de la traducción y la filosofía de la traducción, y todos estábamos intentando descubrir qué tipo de traductores queríamos ser. Me llevó a un nuevo nivel en el que me sentía más preparada para traducir.

¿Qué tipo de preguntas hace n traductor cuando están traduciendo cultura?

Extranjerizar contra domesticar, que es lo opuesto a extranjerizar, es hacer algo familiar para acercar a los lectores. En los 80s se estaban realizando muchas traducciones y en los libros que se estaban publicando se borraban las referencias culturales con el fin de hacerlos más legibles para el público estadounidense. Yo creo que la gente ya dejó de hacerlo, o por lo menos está pasando menos. Además ahora tenemos notas al pie, tenemos glosarios, ahora tenemos esto y aquello. Pero también se trata acerca de ser generoso con el lector y con la cultura que estás traduciendo, y no borrar nada solo por la comodidad del lector al que va dirigido.

A veces, en tu trabajo, por ejemplo, traduciendo Pretty Things de Virginie Despente’s Pretty Things, traduces subculturas ¿cómo es eso?

Es bastante difícil para mí porque yo no me proclamo como parte de esa subcultura. Seguido, traduzco cosas de alguna subcultura o cultura en específico, de la cual no soy parte y a la que no tengo acceso. Pero la manera en la que las traducciones funcionan sin importar su contenido, es por la investigación. Tu trabajo es familiarizarte con esa cultura, aprender acerca de esa cultura o subcultura y luego reproducirla de manera precisa. Recuerdo cuando comencé a traducir a Anne Garréta, en donde casi todo toma lugar en discotecas, y mi consejero me dijo “necesitas ir a antros. Estás en París y tienes que ir antros”. Y yo como “okay…” porque era investigación. Y con el libro de Despentes, fue más preguntarle a mis amigos ciertas preguntas. Hay referencias a ciertas bandas. Así que preguntarle a algún amigo conoces a esta banda, quién escucharía a esta banda, qué edad tienen estas personas?” Y la jerga…O sea, si existe algún tipo de jerga usada en una subcultura en Francia, eso no significa que sea similar a la jerga de la subcultura de aquí. Sólo intento hacerla sonar auténtica. No siempre significa recrearla. Para mí, era como ver a una subcultura de personas de veintitantos en París, preguntarme “¿cómo hablan los veinteañeros en Estados Unidos?” no “¿cómo hablan en Francia?” y luego imitarlo.

Además de ir a antros ¿qué otras maneras de investigación se requieren?

Eso depende de cada lubro. Con la poesía marroquí en los que estuve trabajando recientemente, de Ahmed Bouanani, estuve en Marruecos por un año. Involucró ir a su casa, ir a los lugares a los que él iba y hablar con su familia. Su poesía tiene muchas referencias culturales, de leyendas marroquíes, cuentos marroquíes, edificios, los colores de las calles. Puedes acceder a mucha de esta información si eres un académico con acceso a diferentes fuentes. Pero no soy estudiante, así que estar en los lugares, ser capaz de ver que él está hablando de este color, es de mucha ayuda. “Okay, está hablando acerca cómo los minaretes ver hacia el cielo, está hablando acerca de esta leyenda que nada que googlee me va a ayudar a descifrar”. Pero si voy a preguntarle al bibliotecario de este lugar, él me va a poder decir de qué se trata.

Eso está genial. Debe ser muy emociónate, graduarte de la universidad y volverte traductor, viajar y vivir todas estas cosas nuevas como parte de tu investigación.

Sí. También es importante para mí traducir del francés a autores que vivieron en otros lugares además de Francia. Hay muchos lugares en el mundo donde se habla francés; donde la gente está escribiendo en francés. Eso es algo impresionante acerca del francés. O sea, es desafortunado que esto ocurra por la colonización, pero significa que como francoparlante, tengo acceso a mucha más literatura que si hablara húngaro, por ejemplo. No quería enfocarme sólo en Francia y quería encontrar trabajos que vinieran de una perspectiva diferente y de una nación diferente. No hay muchos libros en Marruecos que estén siendo traducidos. No hay muchos libros de Argelia que estén siendo traducidos. No hay muchos libros de Senegal que estén siendo traducidos. Todos estos lugares donde hay escritura en francés, hay mucha reticencia o, no sé, tal vez falta de iniciativa por parte de traductores y publicistas. Si presentar y tener un libro marroquí más publicado que de otra manera no lo hubiera estado, es algo positivo.

0 notes