#So long as they keep doing the bela lugosi dracula and boris karloff Frankenstein then the peter lorre impressions will continue to go on

Text

Okie doke so I have a lot of asks piled up but I’m gonna need to take my time with them. So in the meantime I’m gonna give you guys a few of my own personal writings while i weed through my writers block. I hope you can understand, I have fourteen prompts to get to but I am a little muddied on getting through each one.

David Headcanons

Italian food used to be his favorite when he was alive. Santa Carla was flooded with immigrants from all over, especially a high concentration of Europeans so he had experienced real Italian cuisine from the few family owned joints that would come and go. When he was turned he tried to defy his vampire roots after learning that garlic didn’t hurt him- only to find out it didn’t hurt him EXTERNALLY. The tragic tango of pasta primavera in his stomach had him sick as a dog for days! Since he’s opted for other cuisines, but secretly he misses when he could freely ingest copious amounts of garlic

Outside of rock, David really loves classical music. Particularly foreign opera. Why? Because it is some of the most intense sounds you will ever hear. The melancholic arias of tortured souls left on the brink of tragedy soothe his untamed internal rage. However, he often doesn’t get to because as soon as he does Paul pitches a fit.

“Aw whaaat? Classical? Who invited the old lady to the party?! “

“Will you shut up and let me listen to my music, asshole?”

“Ooooh excuse me! Yes of course, Lord Snooty von Dickweed. Would you care for your pet poodle and a plate of caviar? Hey! Maybe we can find your balls, dude”

Of course he could just kick him out but it’s far too much of a hassle. He’s genuinely pleased, albeit subtly so, when he managed to snatch up a walkman off a victim so he can listen to his music in peace.

We’ve seen him smoke, but no one really gathers just what a chimney this guy is. David smokes practically every hour, when one burns out he just snags another. Any reason is a good reason to pull out a cigarette. Stressed? Smoke. Hungry? Smoke. Tired? Smoke. Happy? Smoke. But worst of all are his nicotine withdrawals. Seriously, do not approach him when he’s run out of cigarettes. It doesn’t matter who you are. Last time Paul tried to tease him while he was waiting for nightfall, David nearly threw him out into the sun. Withdrawal is far worse as a vampire than it was for him as a human. His restless legs get far more jittery, his back can cramp, it’ll give him an agonizing headache, and his hunger is somehow amplified.

Surprisingly, he can’t stand the 1931 film of Dracula with Bela Lugosi. Not that Lugosi doesn’t do a good job. In fact, it’s far too good. While not appearing visually the same as Vlad Dracul, the bastard who just so happened to be responsible for turning him and his friends back in 1906, his personality is extremely close. Just watching him slink in the shadows, waltzing about in that chilling Hungarian-Romanian accent boils David’s undead blood. If he’s going on the Universal monsters, he prefers Boris Karloff in Frankenstein.

Over the years David has picked up Russian and French. When you’ve been unchanged in an abandoned wreckage of a hotel for over eighty-one years, you learn to pick up a few things. Currently he’s learning German which he finds rather easy so far although he finds himself speaking a tad choppy at times. Sometimes he’ll use the wrong language and end up asking Paul to bring him the wine bottle of blood in Russian. Needless to say he was utterly confused and had to be retold in English.

Despite what one might assume, David does not enjoy having sex with multiple partners. Not polyamory, just sex in general. He finds that hollow humping up against some seasoned tart behind a bar before bidding adieu does nothing for him. If there’s no intense intimacy there’s less really keeping him invested. Now love isn’t exactly what is required, but there has to be some sort of connection to give him the desire to pursue a lover. Quality over quantity. Getting to know his partner is an exciting endeavor that allows him to take control, dominating him or her until they are utterly helpless to his will. A quick fuck is nothing but a way to kill time, which frankly he can find so many more productive things to do when he’s bored that require much more brain power and a lot less sticking himself in something, sorry, someone that he honestly doesn’t know where they’ve been.

Halloween, of course, is his favorite time of year. However he also has a soft spot for Christmas. Frankly the whole peace on Earth and goodwill towards men crap makes him sick simply because no one had ever given a crap about him, but the entire feeling of it all did give him a sense of calm. The lights are a stunning sight for sure, and he'd even have a few less shitty humans mistaking him for one of the teen runaways living on the Santa Carla streets. Well, he wasn't , but he wasn't about to tell that to some sweet old lady handing out rusty tins of fresh brownies. Who the hell could waste brownies? Not him. His favorite memory goes back to 1904 when he and the boys managed to scrape up enough dough between pick pocketing gigs to share a room at a decent hotel. The managers wife even brought them up the leftovers from their own Christmas dinner, half a roast bird, a plate of rolls, a fat bowl of mashed potatoes and some gravy. They of course were grateful, and Paul couldn't help but flirt just to kiss ass. Dwayne got Paul a new knife, Marko got David this pretty swanky looking cigarette case he snatched off some rich dick who mistook him for a shoe shiner, David found some old iron ring they couldn't sell and gave it to Dwayne, and Paul got a few bottles of rum for them to get Yuletide hammered. Sure it didn’t sound like much of a big deal, but sitting on a real bed for once by a fireplace slamming back booze and roast chicken while whooping Marko’s ass in black jack was the first time in a long time he had genuinely laughed. Since then its been particularly blase, but Marko and Paul will often make a tradition out of a few bottles of booze, throwing some cheap decorations around the hotel, and they all spend the night playing card games over some take out roast chicken and a few quick sides.

#lost boys 1987#lost boys imagine#the lost boys#lost boys fanfiction#fanfiction#fanfiction writing#lost boys#fanfic#80s movies#lost boys david#lost boys head canon#headcanon#fandom#fanfiction author

117 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bela Lugosi’s Dead | Notes on the Work of a (Possible) Blood-drinking Aristocrat

It’s a sad fact that Hollywood has never been very good in terms of diversity in front of or behind the camera (and still has a long way to go), and over the years has often limited opportunities or slotted actors in roles that play to their “otherness”. This weighed heavily on my mind as I watched White Zombie, as I don’t know if any actor has taken control of that otherness and used it to such unsettling effect as Bela Lugosi does so here. Lugosi’s presence is so distinct and his delivery so mannered that he seems not to be playing a villain so much as embodying evil itself and piercing through the artifice of the film around him. Lugosi’s performance also ties into the film’s racial politics, which are queasy as can be expected for a horror film about Haitian voodoo, but complex. A character decries local practices as “sins that even the devil would be ashamed of”, yet the plot centres on a foreign, colonial presence exploiting those practices, and it isn’t a stretch to read his act of turning his enemies into zombies as a metaphor for slavery.

The film exists in an eerie dream state between silent and sound film, and any imperfections only enhance that feeling. Dialogue and sound intrude jarringly into silence or music (particularly the shriek of a vulture, which never stops being unnerving), and any stilted acting brings to mind the zombies enslaved by the villain. The atmosphere is evocative and foreboding, with images that sear themselves into our mind. Victor Halperin would go on to direct a sequel, Revolt of the Zombies, which does not star Lugosi but recycles the same shot of his eyes. Lugosi’s absence is sorely felt, as is any semblance of the atmosphere or visual style present in this film, and its handling of race lacks the complexity offered by this earlier effort. The movie briefly perks up when the revolt in the title finally happens, producing a handful of interesting images, but for a movie that runs about an hour, it easily feels thrice as long.

I would be remiss to delve into Lugosi’s work without revisiting his iconic work in Tod Browning’s Dracula. I don’t know if I actually think the movie is any better this time around, but I did find myself more endeared by it. It’s hard to find interesting things to say about his work here, but while what we know of Lugosi’s life suggests that he probably wasn’t really a centuries old blood-drinking aristocrat, the lived-in quality of his performance might have you fooled. George Melford’s Spanish language version is a much more dynamic film on the whole (and is on the shortlist of my favourite vampire movies), yet there’s no denying Lugosi’s absence isn’t felt. (The wonders of modern technology have allowed the the transplant of Jim Carrey into The Shining and many of our beloved celebrities into hardcore pornography; I would argue that deepfaking Lugosi into the Melford Dracula is just as worthwhile an experiment.) It’s safe to say that he’s much better than the movie he’s in, the stage origins of which are apparent (characters are frequently shot staidly, centre frame; much of the action takes place in the same room with characters entering and exiting in lieu of actual incident), yet that stylistic stiffness yields great dividends when the action moves to Dracula’s castle, with those scenes having an aura of entombment.

Perhaps this approach was an extension of Browning’s view of the genre. Many vampire movies emphasize the sensual, striving to demonstrate the erotic allure of the condition; Browning’s film argues that the living dead lead a pretty dismal existence. “There are far worse things awaiting man than death.” An arguably dismissive attitude towards vampirism could be read into Mark of the Vampire, which reunites Lugosi and Browning. The movie is at times quite atmospheric, particularly when Lugosi is onscreen, yet in a way that feels fairly divorced from the energy of the film as a whole. (He also unfortunately has no dialogue until the end, although he makes the most of it.) If Dracula suffers in comparison to the stylishness of James Whale’s Frankenstein movies, then Mark of the Vampire could have used some of the tongue-in-cheek energy Whale brought to The Old Dark House.

The Devil Bat finds Lugosi working with a much smaller production by Producers Releasing Corporation, a Poverty Row studio. It’s not an especially dynamic work, featuring a not terribly convincing bat puppet and a scene where his character awkwardly confesses to his crimes and schemes up a murder on the fly to cover his tracks, yet his professionalism can’t be denied and he’s quite good in the role. Bela Lugosi Meets a Brooklyn Gorilla, which has a technically accurate but misleading title, finds his career in more obvious decline. Your enjoyment may depend heavily on your tolerance for Jerry Lewis style shrillness, yet once again Lugosi treats his role as serious as a heart attack. This movie is also of interest to fans of Duke Mitchell, showing him well before he developed the vulgar charisma of his wannabe Godfather characters in Massacre Mafia Style and Gone with the Pope. Towards the end of his life Lugosi came into the orbit of Ed Wood, considered by many to be the worst director of all time. The extent of Lugosi’s role in Plan 9 From Outer Space is well known, but his last speaking part came in Bride of the Monster. Neither film did much for me (Wood’s distinct brand of badness has little effect on me for whatever reason, and Bride didn’t seem all that worse than some of the other films I’ve seen this month, to be honest) but Lugosi makes the film just a bit more engaging whenever he’s onscreen.

Going back to his prime years, Murders in the Rue Morgue finds Lugosi on stage at a carnival sideshow, pleads with an unappreciative audience, and by extension, the viewer (“Heresy? Do they still burn men for heresy? Then burn me monsieur, light the fire! Do you think your little candle will outshine the flame of truth?”). There’s a sense of resentment here, of doing great yet unappreciated work in squalid conditions, that I suspect might have resonated with him over the course of his career. The out of place aristocracy he brings to the role makes him all the more magnetic and, at the same time, undeniably creepy, which makes the relatively explicit (by 1932 standards) content resonate. (A gruesome knife fight and a sexually charged torture scene are among the highlights spicing up the first act.) The movie definitely loses a little whenever Lugosi isn’t onscreen, yet Robert Florey’s visual direction, heavily influenced by German expressionism, is dynamic enough to always keep things engaging. This is the movie Lugosi made after walking away from Frankenstein, and while there are similarities in visual style, Lugosi’s performance here couldn’t be more different from Boris Karloff’s in the other film.

It’s hard to discuss Lugosi without mentioning Karloff, that other titan of early sound horror films. Karloff’s career ended with more dignity (his last film, Targets, offers a reflection on his career, the horror genre and violence in ‘60s America), yet going head to head in The Black Cat, Lugosi wins. Karloff is great, giving an eerily mannered, subtly monstrous performance, yet Lugosi is able to create a character that not only is implied to have the same capacity for monstrous behaviour, but get us to empathize with him. There’s an early line delivery that might be one of the best I’ve ever heard with its mixture of menace and deep psychological wounds. (I will quote it, but hearing it delivered by the man himself will send chills down your spine. ”Have you ever heard of Kurgaal? It is a prison below Omsk. Many men have gone there. Few have returned. I have returned. After fifteen years... I have returned.”) He grounds the twisted headspace that the movie inhabits, which Edgar G. Ulmer evokes with a bold visual style and uncanny art direction. The cumulative result is the best horror film I’ve seen in quite some time.

#film#movie review#white zombie#revolt of the zombies#victor halperin#dracula#mark of the vampire#tod browning#the devil bat#jean yarbrough#bela lugosi meets a brooklyn gorilla#william beaudine#murders in the rue morgue#robert florey#the black cat#edgar g. ulmer#plan 9 from outer space#bride of the monster#edward d. wood jr.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

1931’s Frankenstein and the “Slow Turn”: The Lost Art of the Subtle Scare

A friend of mine recently asked for my thoughts on subtle scares in horror. I asked her to elaborate and she responded “You know, those scares that aren’t exactly in your face but are still super effective!” Immediately, my brain shot to one of my favorite scenes in classic monster cinema: Boris Karloff as Frankenstein’s Monster, and his slow turn towards the audience. Here, we’ll discuss that particular shot and why I think it’s the perfect example of what I feel is a lost art in today’s cinematic climate.

In the age of the jump scare, it’s easy to see why some horror fans may feel jaded when watching what Hollywood has offered up as of late. However, in an effort to avoid beating a particularly dead horse, I don’t want to spend this article talking about how bad jump scares are. Overused as they may be, jump scares aren’t new, and they aren’t always a bad thing. The real problem is that big budget production companies have a tendency to get the wrong impression of what audiences want. We’ve seen it happen time and time again, where a franchise ratchets up the gore and jump scares in lieu of the more subtle elements that made the original films so well received, ie The Conjuring and Saw. As I said, jump scares aren’t always bad, and we can look back to two iconic examples to see where they’re utilized extremely well.

The first example comes at the end of the very first Friday the 13th film, where just as Alice (Adrienne King) thinks she’s home free, a rotting Jason Voorhees (Pre-Kane Hodder behemoth incarnation, here played by Ari Lehman) jump scares her out of a dream. It’s a closing jump scare that we still see used now a days, albeit without the same effectiveness the original had. Another great example comes by way of Freddy Krueger (Robert Englund) during the intro of A Nightmare on Elm Street. This jump scare signals the beginning of a chase scene through a dark alley way, jolting our adrenaline like a gun going off at the start of a race. Now a days, that jump scare would get a laugh out of the audience instead, draining all tension from the scene and revealing it’s just one of the protagonist’s friends popping out of the dark to ask them out for drinks.

With my applauding these last two examples, why is it I find the scene where we first see the Monster’s face in James Whale’s Frankenstein to be so effective? One thing that sticks out to me right away is the lack of a score in the original Frankenstein. We have been trained to recognize a coming scare the same way a boxer learns to read body language, and a lot of this has to do with musical cues. Movie goers know that when they see their protagonist stare into a dark corner of their room, the ambient noise and score of the movie slowly dropping out til it’s completely silent, a loud musical stab is sure to pop out of the darkness to startle them. However, Universal’s Frankenstein has no musical aid to warn the audience of what they’re about to see. We watch as Boris Karloff, beginning with his back to the audience and filling up the frame of a doorway, enters the room and turns ever so slowly towards the audience. The camera then cuts between shots, pulling in closer and closer on the Monster’s face with each cut, all of this playing out free of a musical score.

As synonymous as Bela Lugosi is to Dracula, as is Boris Karloff to Frankenstein’s Monster, and his legendary face creeping in closer to the audience is extremely startling. Much of this of course has to do with Karloff’s facial structure itself, but the icing on the cake comes from make up wizard Jack Pierce. Pierce is responsible for most of Universal Studios’ most iconic monster makeups, and his work on Frankenstein is one of my favorites. He and Karloff worked tirelessly on the look of the Monster, and I believe it was Karloff who suggested pulling out a bridge he wore in his mouth to help give his cheek a sunken in, corpse-like look. The blend of practical effects, and a face made for scaring audiences resulted in one of Universal’s most terrifying shots.

Of course, it takes more than just great makeup and stark silence to make for an effective and understated scare. The direction of this scene plays a big part in its delivery, and our response to it as audience members. Imagine how differently the scene might have played out if the Monster entered the room facing us, as opposed to walking in backwards. He would walk out of the shadows and into the light of the shot without the build up of the original. The decision to have the Monster enter the room with its back to the audience does two important things:

First, it gives us a sense of how disoriented the Monster is. The hulking corpse hobbles backwards and gives us a sense of his size and mass as he slowly, and carefully, turns to face his creator.

Second, by forcing us to sit through this slow, and quiet reveal, it helps to draw the audience closer towards the screen. As I watch Karloff take his time revealing the Monster’s face, I can feel my back come away from my couch as I lean forward to meet his gaze. As an audience, we are frightened and intrigued, but most importantly, we are engaged. This last piece of the puzzle is what great directors strive for, and Whale did a fantastic job capturing the moment.

Although the “Slow Turn” is a technique that’s used less often these days, it doesn’t mean it’s completely absent. A great example comes from the classic Halloween, directed by John Carpenter and released in 1978. The shot of Michael Myers, The Shape, slowly manifesting from out of the darkness behind Laurie Strode (Jamie Lee Curtis) is perhaps the closest to this “Slow Turn” idea we see used in Frankenstein. The mask seems to appear out of the dark like a ghost and the dread that moment cooks up is wonderful. Andy Muschietti’s IT holds another great example as Ben Hanscom (Jeremy Ray Taylor) flips through a book of Derry, Maine’s gruesome history. You’re likely to miss it, but in the background is Pennywise the Dancing Clown, here disguised as a librarian, staring menacingly at Ben. There is a faint smile visible, and the distance it keeps from his intended prey helps to up the “Slow Turn” scare factor of the shot. We even get a tribute of sorts to the “Slow Turn” in Capcom’s classic video game Resident Evil. A decomposing zombie looks up from its meal and turns to meet the player’s horrified gaze in an iconic cut scene that gave me nightmares for quite a while.

Frankenstein has long been my favorite of the Universal Monster movies, and I’ve often sited this moment, lasting all of 21 seconds, as one of my favorite shots in the entire film. The patience with which the scene is shot, the make up on Karloff’s face and the amount of character he puts into simply turning towards the audience is so beautifully effective. As I said, jump scares have their place, but the “Slow Turn” is an art form that embodies all that I love about classic horror. Though we may be able to find other examples of it in horror cinema history, for me, the Monster’s entrance is a moment whose electricity is hard to resurrect.

#frankenstein#frankenstein’s monster#boris karloff#james whale#victor frankenstein#universal monsters#horror movies#classic horror movies#friday the 13th#a nightmare on elm street#jason voorhees#freddy krueger#halloween#john carpenter#it 2017#andy muschietti#resident evil#moonlight madness#moonlight madness reviews

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

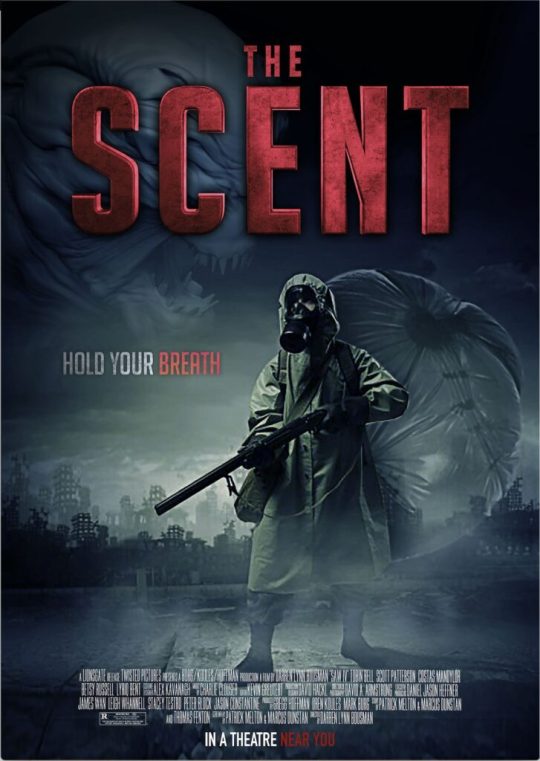

The Scent Movie 2020

Allow us to lower proper to the chase...or proper to the screaming as lots of the people on this record would like! Not solely am I married to a prime house haunter, I've been a giant fan of horror films (additionally known as monster films) for years. In my expertise, as a fan of the style, listed below are my prime ten monsters of all time! The Scent Movie 2020

10. Kraken (1981)

From the 1981 Conflict of the Titans, this can be a creature that stirs the creativeness. Though the Kraken is a creature of delusion, it's the movie model that everybody remembers. Who might overlook the top scene of the unique Conflict of the Titans the place the Kraken comes for Andromeda? (What he wished her for isn't clear to me. Did he plan to eat her? Invite her to go for a swim?) At any charge, the Kraken was delivered to life by the stop-motion animation of Ray Harryhausen, a legend in horror and fantasy films. The picture of Perseus turning the Kraken to stone is basic and so is that this multi-armed monster on this author's opinion.

9. Creature From the Black Lagoon (all variations)

There have been many films about terrifying sea creatures, however Creature From the Black Lagoon continues to be the very best. (Sorry, Jaws!) Launched in 1954, it incorporates a monster-like gill-man found on an expedition within the Amazon. Like many well-known monsters of the silver display screen, the Creature spawned sequels. The unique Creature of the Black Lagoon film is being remade for a 2011 launch, in keeping with the IMDB Web page.

See Also

eight. Mummy (Boris Karloff)

Boris Karloff makes his first look on our record! The Mummy, directed by Karl Freund, is a 1932 horror movie from Common Studios. It starred Karloff as a revived historical Egyptian priest known as Imhotep. Whereas the film isn't a drop-dead scare fest, it's a basic that's within the collective reminiscence of our society. When individuals consider mummies, they invariably consider Karloff shuffling out of his sarcophagus in bandages. The Mummy was semi-remade in The Mummy's Hand (1940) but it surely was Karloff's model that started the Mummy films.

7. Michael Myers (all variations)

Michael Myers is the one who began the slasher style. He first confirmed up in 1978's Halloween as a younger boy who murders his older sister, after which returns house years later to kill once more. His fights with Jamie Lee Curtis within the first two Halloween films are excellent examples of how scary film chases ought to work. Though, I believe Michael's fights with Donald Pleasence (who performed Dr. Loomis) are the very best components of the Halloween movies. The one detrimental features to the Halloween films to me are the continuity points. As an example, Halloween III, though not a foul film, has nothing to do with the opposite installments. Additionally, Halloween H20: 20 Years Later virtually ignores established continuity from earlier films with no clarification.

6. Dracula (Bela Lugosi)

Bela Lugosi was a Hungarian actor, finest recognized for enjoying Rely Dracula within the Broadway play and basic Common Studios Dracula movies, too. The now basic Dracula that made Lugosi a star got here out in 1931. Though the film is a little bit gradual and never as thrilling as different Common classics, such because the Frankenstein movies, Lugosi made the movie work. Irrespective of what number of vampire films are made, too, that is essentially the most memorable. Ask anybody who's Dracula they usually instantly consider Bela's Dracula. His Dracula is an icon.

5. Freddy Krueger (Robert Englund)

Robert Englund is finest recognized for enjoying serial killer Freddy Krueger within the Nightmare on Elm Road movie sequence. Based on Wikipedia, he acquired a Saturn Award nomination for Greatest Supporting Actor for A Nightmare on Elm Road three: Dream Warriors in 1987 and A Nightmare on Elm Road four: The Dream Grasp in 1988. I'm not shocked. He was glorious as Freddy. The brand new Freddy can not maintain a candle, or dingy pink sweater, to Englund. He approached taking part in Freddy with a mix of horror and comedy. His witty banter along with his victims is the stuff of legend.

four. Wolfman (Lon Chaney Jr.)

"Even a person who's pure in coronary heart and says his prayers by evening, could turn out to be a wolf when the wolfbane blooms and the autumn moon is vivid."

If you speak about werewolves, there may be none higher than Lon Chaney's Wolfman within the 1941 Common Studios film. From the long-lasting make-up to the gypsy curse, it's Chaney's Wolfman that society is aware of finest, and with good cause - it's a darn good film that stands the take a look at of time.

three. Frankenstein's Monster (Boris Karloff)

Do I actually have to write down that Boris Karloff's portrayal of the Frankenstein Monster is a basic creature of the cinema? The crash of thunder, the scorching laboratory machines, the monster's hand moving-these are the pictures all of us have embedded in our minds. No model of the Frankenstein Monster will get higher than Karloff's model from the basic 1931 horror movie.

2. Leatherface (all variations)

Leatherface is the principle killer in The Texas Chainsaw Bloodbath horror-film sequence. He wears masks product of his victims' pores and skin (which is the place the identify Leatherface comes from) and is the character from the film who usually carries a chainsaw. Not solely is Leatherface one of many first slasher-type villains however he's drop-dead scary! Whereas I believe all variations of Leatherface are scary as heck, the very best Leatherface actors have been Gunnar Hansen (from the primary Texas Chainsaw Bloodbath) and Invoice Johnson (The Texas Chainsaw Bloodbath 2). I nonetheless assume the scene in Bloodbath 2 when Leatherface runs, chainsaw roaring, out of the darkened radio station towards the lead feminine actor is horrifying.

Related Links:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Scent

https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/web-series/reviews/bengali/tasher-ghawr/ottmoviereview/77925626.cms

1. Jason Voorhees (all variations)

Certain, Kane Hodder has performed Jason greater than every other actor, however I am unable to choose one Jason that's higher than one other. Every actor who performed the undead slasher Jason Voorhees introduced one thing new to the position. Jason Voorhees is the killer from the Friday the 13th sequence. He first appeared in Friday the 13th (1980); though, he was not the principle villain within the first film. Jason is a superb character due to the long-lasting hockey masks, the creepy camp setting, and since you really feel some sympathy for him. He was a deformed youngster who was mocked by friends and ignored by camp counselors. He additionally loves his mommy. (Watch the films and you will notice what I imply.) As a result of he evokes sympathy within the viewers, he's a little bit like Frankenstein's Monster however undoubtedly extra evil.

Agree with my selections? Disagree with me? Put up a remark. And bear in mind to look at over your shoulder when strolling within the woods at evening. The blokes above could also be stalking.

It might be no nice coincidence that the scariest film of all time was launched within the 1970s, a decade infamous for cult killings, hallucinatory medicine, civil unrest, stunning imagery, and a public consciousness that was nonetheless very entrenched within the wrath of God versus the duplicity of the Satan. "The Exorcist", directed as a play of insanity and hellfire by William Friedkin (and primarily based on a e-book that was supposedly primarily based on a "true story") is a superb movie that set the usual for horror--so excessive in reality, that it spawned 1,000,000 sequels, imitators and montage methods that we so simply take as a right within the CGI age. To see The Exorcist immediately continues to be a visceral delight, although it is unlikely viewing it can result in any miscarriages or seizures, prefer it did throughout its debut, little question benefiting from a little bit of group hysteria. It's a movie that has aged barely, however that also packs an emotional wallop, even with a whole technology of desensitized nihilists who grew up taking part in GTA.

Horror and Gore

The Exorcist goes for scares over gore, although there are a number of bloody homicide scenes right here and there. Friedkin rightly understood that the inexplicable and the surreal are really the scariest components of a nightmare, which is why he went all out to rework an innocuous little lady into an obscenity-spewing, spider-crawling demon crammed with nothing however contempt for mankind. Friedkin's inventive use of low-cost visible results is spectacular, and more practical than 100 computer-animated corpses. Pazuzu is really one among cinema's best villains, and maybe due to the spirit's random, indiscriminate nature. Nobody was protected from an offended spirit, and the truth that Friedkin allowed it to own a tragic little youngster (surpassing Hitchcock's in-the-shower vulnerability) was really the top of our fourth wall consolation zone.

Find out how to Watch It

The subliminal messages within the movie add to the creepiness issue. For the very best outcomes, watch it sober, at the hours of darkness, and watch it earlier than all of the tens of millions of imitators. Do not be shocked in case your honey calls for you to place the DVD outdoors the home earlier than returning to mattress!

Did You Know?

It's rumored that Ellen Burstyn solely agreed to play the position of Chris MacNeil, if she did not must say the scripted line "I imagine within the satan". After all she received her means.

Related Topics:

How Creating How-To Videos Can Benefit Your Business 2020?

Ten Mistakes Beginner Filmmakers Make

0 notes

Text

123Movis

We as movie watchers have come a long way since the introduction of movie tapes and watching movies from our home. From beta max to the VCR tapes, we have rented and recorded thousands of movies and still do. Now with the advent of Dvds , movie quality has come full circle to what movie watchers demand, theater quality movies anytime anywhere. Now the demand is shifting with the increase in computer speeds and high speed internet bandwidth. No longer do you have to goto to a brick and mortar stores to find movies to watch. With a few clicks and a search, you can literally be watching your favorite movies on your computer in less time than it takes to drive to the store. This shift in demand is why there are sites offering you to

download full version movies

for about the same price to goto the movie theater or movie rental store. Now you can download unlimited movies with no per download cost. Imagine your own movie database to download as much and as many movies as you want.

The major benefit of joining a movie downloading site is that members get access to a variety of movies from the latest releases to all the classic movies. Download as much and as often as you like for one fee, without having to pay late fees or per download fees. There are other benefits of joining a movie downloading site. Here is a list of a few:

Downloading movies have become a convenient way of finding the movies you want to watch without having to goto the movie rental or movie theater. No more late fees and sold out movies. There are literally thousands of movie titles to choose from and you are not limited to what or when to download.

The movies you download can be played from your computer, copied to a disk to make a DvD, or transferred to a portable movie player. The software used at most of the movie download site or easy to use and also come with the membership.

When you Download Full Version Movies using a movie download membership site you are getting a secure database to download from without the worries of catching a computer virus or other infections such as spyware or malware. The majority of the sites offer free scanning software to make sure your downloading experience is SAFE and Easy.

The Price is one of the biggest factors in how many DvDs you buy. Well that has changed because you get unlimited access and unlimited downloads without any per download fees or hidden costs. You can be on your way to making that movie data base that you always wanted relatively cheaply and safely.

These are just a few benefits you get when you join a membership site to Download Full Version Movies. It truly has become convenient for us to have another way of getting the movies we want. Downloading movies has never been easier or safer with the price of a tank of gas. If you are a movie fanatic like I am then you must check out this new trend in

movie downloading

About Us

We are here to provide you with the best movies you want to watch whenever you want wherever you like.You can either download them, watch them online or do both. Enjoy the finest quality hd movies here. Trust us, you wont regret the visit.

Blogs

A Great Reason Why People Need to Watch Comedy Movies

Everyone needs a good laugh from time to time. That is when we go to see a good comedy. There are many reasons why this genre of movies is good. Everyone needs a little bit of laughter at some point in their life. They have to smile because things in this life just wear us out and break us down. However, there is a good thing or two to know about comedies.

Comedies are suitable for people from all age groups. There are cartoons for kids and more matured content for adults and teenagers.

Comedy

is a way to keep people from all walks of life entertained. Some comedies are based on family values, therefore making it suitable for parents and children to watch and enjoy together.

Nevertheless, some of the materials used to make people laugh have been pretty controversial. There have been some comedies that are based on jokes that demean a person’s sexual orientation. Gays and lesbians have been bashed greatly in most comedy flicks. It is very common to turn on your TV to watch a movie, and to find that there is a gay or lesbian in the movie that has all the perceived characteristics associated with homosexuals.

There are also some films that make comedy out of racist jokes. People tend to laugh when they show a movie where a Mexican is driving a van recklessly when there are other drivers on the road. Some make racist jokes about black people. Contrary to what is being fought for by human rights, our society has taught us that making fun with racism is very acceptable.

There might have been times that come you have gone to watch a comedy movie and left the cinema finding that the movie is not funny at all. There are some movies that just try too hard to be funny. You probably would have seen at least one of these lousy comedies. We wonder where the directors came up with such a plot for these films. It is almost as though someone who was smoking weed had put random videos together and called it a movie.

However, there are some comedies that touch the heart and stick to you. Many favored movies that made jokes about previous movies that have been released. Many of you will remember the

Scary Movies

films which made fun of several horror movies. We laughed because Scary Movie made fun of other horrific and scary movies, and turned it into a light-hearted movie.We should have a little time for comedies in our lives. It is what we need after a tough or bad day. Sometimes, we don’t want the fairy tale ending. We don’t want to think. We just want to laugh and enjoy the show. This is what top 10

comedy movies

do for us. It is also the type of movie you can go to when you want to watch something alone. And at the same time, you can watch comedies together with a group of friends. Finally, comedies will be perfect if you just need to calm down and lose yourself for the moment.

Article Source:

https://www.123movis.us

The History Of Horror Movies — Tribute to Horror in Cinemas

From time to time, we see so many

horror movies

come and go. Spooky, haunted houses, serial killers, slashers, maniacs, mentals, satanic and many others have been pictured in the movie. A lot of sub genres, a lot of remakes, a lot of variations, twist and all that can easily be found through the ages. Yeah, it’s all true. But have we ever thought where it all came from?Or how does the horror movies genre change from time to time?

For you who share the same passion about horror movies, and want to know the road that have been travelled by Horror movies, allow me to have the honor to be your guide. Buckle up, here we go.

Where It All BeganThe year was 1922, place: German. I can say that it was the birth of horror movies. W Murnau started the terror and fear through Nosferatu, nosferatuthestory about bloodsucking vampire. It wasn’t the first vampire movie, as in 1896 Georges Melies made Le Castle Du Diable, but Nosferatu was the first movie where we saw vampire destroyed by sunlight. This one boasted remarkable animalistic makeup that has not been replicated, even with moderntechnology. Dozens of

vampire movies

followed after that. In 1931 Universal Studio launched 2 legendary horror movies, Dracula with Bela Lugosi and Frankenstein with Boris Karloff. Both of the movie became a classic and very successful. Boris Karloff even became a legendary name in horror movies history. The Mummy (1932) a silent picture with horror icon Boris Karloff in the title role, remains a classic, with unforgettable make-up and atmosphere. In 1935, the sequel of Frankenstein,The Bride Of Frankenstein was made.This isn’t silent anymore.

Psycho

During 40’s the world’s on war, and it has changed the genre. Horror was almost forgotten as patriotic movies and war has taken the place. It slowly raised again around 50’s, where comedy and musical movies ruled. There were good ones took place at this time, House of Wax is one of the example. 1960 was the time for Hitchcock to make a memorable movie: Psycho. Too bad, this is the only horror movie by Hitchcock, cuz then he made lots of suspence thriller goodies like Rear Window, Vertigo,North by Northwest,Dial M For Murder that kinda changed the genre again. And remember, spaghetti western Movies in the late 60’s also had its moment.

The 70'sThis is the most creative year of

Horror movies

.Unlike before, horror movies got big exploration, where so many variation of story and evil came in. Note there were lots of controversy and protest happened here.The Exorcist (1973) for example showed disgusting scenes that never been imagined before, like the green puke to the face transformed to evil. This movie was controversial when Catholic Church protested that the demon cast-out in the movie was against the code of conduct. The shining, that based on Stephen King’s novel was one of the best one during 70’s. Later on from this decade to 80s and 90s, lots of movies was made based on his scary novel such as Carrie, Christine, Cujo, It, , Cat’s Eye, Dream Catcher, are the example. Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974) was a low budget movie that reached a great result. This one introduced “the slasher movie” to the world that later followed by Halloween (say hi to Michael Myers) , Friday the 13th, Scream in the 80’s and 90’s and so on. Omen is a bonechillin’ movie that can still giveyou nightmare even with today’s technology of making movie.Simply unforgettable. Amityville Horror, based on the true story was the first movie that took place in the actual location. The report said a lot of bizarre and dreadful things were experienced by cast and crew in location.

The 80's

Freddie Kruger

This is the decade of madness. All gory stuff were shown sadistically for viewing. cutted off body parts were seen everywhere. Nightmare on Elm Street that launched Freddy Krueger to horror hall of fame, and Jason Voorheyes slashing games in Friday the 13th are one of the example. These two had some of their sequels during 80s, together with 3 of Halloweens. And remember how Italian horror movies that have a very sick super bloody vision? Count Romero and Argento for this category. This is also the era where horror expanded to tv.

The 90'sFunny thing happened in 90s. There’s a tendency of self defense and self actualization by horror character on terror they have made to people. For example Ghost, Bram Stocker’s Dracula that told the story about CountDracula’s painful love to Mina, or Interview With Vampires that unlocked the mystery of vampire lives. Scream started a new genre, teen horror movies, slashing-serial-killer-who-did-it,which soon followed by I Know What You Did Last Summer, Urban Legend, and some more. A note in 1999, an independent movie Blair Witch Project became a big phenomena,using a documentation technique to give us fear,tense and mental disturbance. This one inspired some other movies like St.Francisville Experiment, The Lamarie Project andtv series Freaky Links.

2000's

Ringu

Still too early maybe to talk about horror movies in 2000s, but looks like Hollywood has running out of ideas. They are trying to widen up their view to see new ideas outside that can give new vision on the term of horror. The Ring, remake from Japanese movie was their first success. Followed by The eye, and some other remakes from Asian cinemas.This decade seems being led by Japan and Korea, by making so many horror movies with lack of effects or gory blood but still successfully tortured our feeling. They don’t go with the Hollywood pattern, they just dig everything else that hasn’t been touched yet. Thailand is also emerging as a good horror maker. Indonesian movies too, with amusing number of horror movies every year. We also mark the decade 2000 for the decade of sequels and remakes too, such as Halloween H2O, Freddy vs Jason, modern version of Bram Stocker’s Dracula, Dracula 2001,Halloween Resurrection, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre , House of The Dead, The Amityville Horror and so on.While the effort to combine some genres and produce something new has still been going on. Saw for example, combine the psycho thriller ala Hitchkock with slasher, sadistic, bloody and graphic scenes.

Article Source:

https://www.123movis.us

Privacy Policy

Who we are

Our website address is: https://themashaall.tumblr.com/post/188489209036/123movis

What personal data we collect and why we collect it

Comments

When visitors leave comments on the site we collect the data shown in the comments form, and also the visitor’s IP address and browser user agent string to help spam detection.

An anonymized string created from your email address (also called a hash) may be provided to the Gravatar service to see if you are using it. The Gravatar service privacy policy is available here:

https://automattic.com/privacy/.

After approval of your comment, your profile picture is visible to the public in the context of your comment.

Media

If you upload images to the website, you should avoid uploading images with embedded location data (EXIF GPS) included. Visitors to the website can download and extract any location data from images on the website.

Cookies

If you leave a comment on our site you may opt-in to saving your name, email address and website in cookies. These are for your convenience so that you do not have to fill in your details again when you leave another comment. These cookies will last for one year.

If you have an account and you log in to this site, we will set a temporary cookie to determine if your browser accepts cookies. This cookie contains no personal data and is discarded when you close your browser.

When you log in, we will also set up several cookies to save your login information and your screen display choices. Login cookies last for two days, and screen options cookies last for a year. If you select “Remember Me”, your login will persist for two weeks. If you log out of your account, the login cookies will be removed.

If you edit or publish an article, an additional cookie will be saved in your browser. This cookie includes no personal data and simply indicates the post ID of the article you just edited. It expires after 1 day.

Embedded content from other websites

Articles on this site may include embedded content (e.g. videos, images, articles, etc.). Embedded content from other websites behaves in the exact same way as if the visitor has visited the other website.

These websites may collect data about you, use cookies, embed additional third-party tracking, and monitor your interaction with that embedded content, including tracking your interaction with the embedded content if you have an account and are logged in to that website.

How long we retain your data

If you leave a comment, the comment and its metadata are retained indefinitely. This is so we can recognize and approve any follow-up comments automatically instead of holding them in a moderation queue.

For users that register on our website (if any), we also store the personal information they provide in their user profile. All users can see, edit, or delete their personal information at any time (except they cannot change their username). Website administrators can also see and edit that information.

What rights you have over your data

If you have an account on this site, or have left comments, you can request to receive an exported file of the personal data we hold about you, including any data you have provided to us. You can also request that we erase any personal data we hold about you. This does not include any data we are obliged to keep for administrative, legal, or security purposes.

Where we send your data

Visitor comments may be checked through an automated spam detection service.

Contact us

Like & follow us on social networking sites to get the latest updates on movies, tv-series and news.

123MOVIES | Watch Free Movies Online | 123MOVIS.US

On 123Movies You can watch all new cinema and series movies free online in HD quality. TV Shows online for free. Watch…123movis.us

0 notes

Text

Come Out, Come Out, Whoever You Are!

New Post has been published on http://iofferwith.xyz/come-out-come-out-whoever-you-are/

Come Out, Come Out, Whoever You Are!

Review

Nathan Tipton

Harry M. Benshoff, Monsters in the Closet Homosexuality and the Horror Film. (Manchester: Manchester U P, 1998.) $18.95.

Come Out, Come Out, Whoever You Are!

1. “The plot discovered is the finding of evil where we have always known it to be: in the other” (97). So wrote Leslie Fiedler in The End of Innocence (1955), his summation of the McCarthy-era horrors. Although ostensibly referring to the 1953-54 McCarthy hearings, Fiedler discloses the societal fear of difference operating within the “Us versus Them” dialectic. Moreover, by finding evil in an Otherness “where we have always known it to be,” he acknowledges both the historical construction and destruction of the Other and, in effect, explains society’s genocidal predilections in the name of moral preservation. Nevertheless, Fiedler’s comment leaves larger questions unanswered. How, for instance, does society arrive at this conflation of evil and “other?” And does society need to create monsters for the sole purpose of destroying them?

2. Harry M. Benshoff “outs” his Monsters In the Closet with the conceit of a “monster queer” universally viewed as anyone who assumes a contra-heterosexual self-identity, including those outside the established gay/lesbian counter-hegemony (“interracial sex and sex between physically challenged people” [5]). For the sake of brevity, his work focuses on homosexual males and their presence, either tacit or overt, in the modern horror film. In so doing, Monsters also proposes (with more than a passing nod to gay historiographer George Chauncey), an extant gay history created through the magic of cinema. For Benshoff, however, the screening room quickly morphs into a Grand Guignol-styled Theatre of Blood, and gays become metaphorical monsters whose sole purpose in horror films is to subvert society before meeting their expected demise.

3. Benshoff draws a provocative, decade-by-decade timeline to illuminate his thesis. He begins in 1930s Depression-era America, the “Golden Age of Hollywood Horror.” In a chapter entitled “Defining the monster queer,” the cultural construction of the modern homosexual is placed alongside (and within) classic horror films such as Frankenstein and Dracula (both 1931). Benshoff notes the decade’s movement from viewing homosexuals as gender deviants to those engaging in “sexual-object choice (48),” thus underscoring the ideological shift from Other-as-Separate to Other-Among-Us. This, then, becomes his foundation motif for the modern horror cinema: the fears within us are the fears of us.

4. While the chapter concentrates heavily on the actors and their presumed sexuality (including “name” stars such as Charles Laughton and Peter Lorre) rather than the films, Benshoff highlights an obvious thread of filmic homosociality, particularly in the films pairing Boris Karloff and Bela Lugosi. For example, 1934’s The Black Cat features two “mad” scientists ostensibly competing for one female (although she is later revealed to have been dead all along). Benshoff convincingly reads this arrangement as a homoerotic love triangle, with Poelzig (Karloff) and Werdegast (Lugosi) engaged in teasing flirtation, and finally sado-masochistic torture. The torture scene includes bare-chested Karloff being menaced by scalpel-wielding Lugosi, who threatens (and then proceeds) to “flail the skin from [Poelzig’s] body, bit by bit”(64). Though Benshoff reads the film’s homosociality as a positive step, he nonetheless fails to critique the rather obvious, time-honored homosexual tropes of sado-masochism and murderous psychosis.

5. “Defining the monster queer” also includes a surprisingly short section on director James Whale (on whose life the current film Gods and Monsters is based). Benshoff notes, “A discussion of homosexuality and the classical Hollywood horror film often begins (and all too frequently ends) with the work of James Whale, the openly gay director who was responsible for fashioning four of Universal Studio’s most memorable horror films: Frankenstein (1931), The Old Dark House (1932), The Invisible Man (1933), and Bride of Frankenstein (1935)” (40). While Frankenstein is arguably the most recognizable film in this quartet, Benshoff instead contextualizes Whale’s work through his most explicitly homosexual film, The Old Dark House, in which Whale parodies and, ultimately, subverts the above-mentioned stereotypical cinematic tropes.

6. This film, like many “clutching hand” horror films of the period, uses the device of “normal” people trapped in a defiantly non-normal mansion peopled with maniacs and monsters. The Old Dark House is occupied by the Femm (!) family members, who each have gayly-coded personas. Patriarch Roderick Femm is enacted by a woman (actress Elspeth Dudgeon); son Horace is played by known homosexual Ernest Thesiger in, Benshoff wryly notes, a “fruity effete manner” (43); and sister Rebecca (Eva Moore) is a hyper-religious zealot who is, nevertheless, a closet lesbian. The heterosexual Wavertons (Raymond Massey and Gloria Stuart), along with their manservant Penderel (Melvyn Douglas), spend the vast majority of the film trying to fend off none-too-subtle homosexual overtures from the Femms, although they too are viewed queerly as an “urban ménage à trois” (44).

7. The story is further complicated by Morgan (Boris Karloff), the drunken butler who “may or may not be an illegitimate son of the house” and Saul (Brember Wills) “the most dangerous member of the family” (45), who is understood as a repressed homosexual. Saul sees in Penderel a kinship but, because of his paranoid repression, must instead kill this object of his desire (with, Benshoff points out, a “long knife” [45]). In the ensuing tussle, Saul falls down the stairs, dies, and is carried off by Morgan, who “miserably minces up the steps, rocking him, his hips swaying effeminately, as if he were some nightmarish mother cradling a dead, horrific infant” (45).

8. Benshoff convincingly hints that the film’s over-the-top depiction of homosexuality was the primary cause of its being “kept out of circulation for many years . . . for varying reasons (legal and otherwise) . . . [and] it was not released on commercial videotape until 1995” (43). In fact, the Production Code established in 1930 forbade any openly (or, Benshoff adds, “broadly connotated”) homosexual characters on-screen and, subsequently, “banished [them] to the shadowy realms of inference and implication”(35). But the problem still remains that even in their connotative presence, homosexuals are portrayed as monsters. Although Whale’s Dark House attempts to imbue some non-normals (such as Morgan) with a sympathetic aura, it does so at the expense of Saul, whose death seems to connote a reinforcement of normality. This status quo death-by-design, indeed, becomes a decades-long device in horror films.

9. As the book progresses, Benshoff moves from homosocial film “outings” to socio-filmic movie interpretations and, in this area, he is clearly more comfortable. In particular, the chapter entitled “Pods, Pederasts and Perverts: (Re)Criminalizing the Monster Queer in Cold War Culture” casts a probing look at the so-called “perfect” 1950s. This decade becomes a touchstone for Benshoff because of the close interrelationship between oftentimes-surreal politics (the McCarthy/HUAC hearings) and “real” cinema. Early films such as Them and The Creature from the Black Lagoon (both 1954) exemplify the dialectic between Us and Them while exploring the dynamic of social denial. Benshoff notes, “As for the closeted homosexual, the monster queer’s best defense is often the fact that the social order actively prefers to deny his/her existence” (129) and thus keep its monsters safely in their closets. His queer reading of Creature, while effective, does not approach the astute discussion of the later films I Married a Monster from Outer Space (1958) and especially the Black Lagoon sequel, The Creature Walks Among Us (1956), which not only riff on the Marxist dialectic but present the more insidious scenario of the “incorporated queer.”

10. The title of The Creature Walks Among Us, for example, serves as an overt play on people’s paranoia, both of Communists and Queers (terms which, during the McCarthy hearings, were used synonymously), and the film focuses on intense male rivalries, ostensibly over one woman, Helen Barton. However, her husband, Dr. Barton, has paranoid fantasies about her sleeping with Captain Grant, the hunky captain of Barton’s yacht (which, Benshoff notes, is based in San Francisco). Benshoff easily reads Dr. Barton as a repressed homosexual who would much rather be sleeping with Grant. At the film’s climax, he murders Captain Grant (thus killing the object of his desire) and is, in turn, killed by the Creature. Helen reflects on the sad scene by trying to explain her husband’s rather obvious sexual repression. She states, “I guess the way we go depends upon what we’re willing to understand about ourselves. And willing to admit”(136). But her words also can be read as a plea for societal tolerance of “Them,” in whatever form they appear.

11. Benshoff furthers his discussion of Them Among Us by exploring the phenomenon of the “I Was a . . .” films, which “purported to deliver subjective experiences of how political deviants operated” (146), again through horrifically-packaged political treatises such as 1951’s I Was a Communist for the FBI or “real-life” horror films along the lines of I Was a Teenage Werewolf (1957). These films seek not only to uncover the hidden queer but to expose their insidious agenda of pederastic recruitment. However, for the quintessential 1950s homo-cruitment film Benshoff chooses How to Make a Monster (1958) which, despite its menacing tagline “It Will Scare the Living Yell Out of You,” is viewed as remarkable for “the wide range of signified to which the signifier ‘monster’ becomes attached, and the complexity with which it manipulates these signifiers” (150-51). Translation: How to Make a Monster contains many not-terribly-subtle queer-friendly images that are visible the typical moviegoer, hetero- or homosexual.

12. Benshoff pulls out all the stops in his filmic exploration of How to Make a Monster by deploying a Laura Mulvey-esque theoretical pastiche of deconstruction, Lacanian psychoanalysis, cultural criticism, and Marxism. He concludes that “the film hints at the revolutionary potential of ‘making monsters’ against those same ideological forces . . . which simultaneously create and demonize the monster queer” (151).

13. So what exactly marks this particular Monster for greatness (indeed, a detail of the movie’s poster is part of the book’s cover art)? For starters, the film contains all the elements of a perfectly queer horror flick: a homosexually-coded mad scientist couple Pete and Rivero (complete with “requisite butch/femme stereotyping” [151]) who are, as an added bonus, also tacit pederasts. They are balanced by two “normal” heterosexual teenage All-American boys, Larry and Tony, who nevertheless get “made up” and engage in a clearly homoerotic “Battle of the Monsters.” The story is further complicated by a Marxist interlude during which capitalist movie studio executives arrive and sever their ties with the monstrous director and his makeup-artist-partner. Benshoff observes, “The scene explicitly links the patriarchal order with capitalism, and Pete [the now fired director] and his monstrous world as opposing it. As Pete turns down the offer of severance pay, one of the studio executives clucks ‘Turn down money — maybe you’ve been living too long with monsters'” (153). Pete, rather than accepting his fate, formulates a revenge plot against the capitalist studio executives, and herein invokes another horror film trope — “that which is repressed (in this case the Hollywood monster movie) must eventually return.” However, Benshoff continues, “these particular monsters are not going to be of the imaginary/Make-Believe/Movie/ Sexuality kind; they are going to be deadly” (154).

14. While this revenge plot is a precursor to the spate of 1980s “Everyman” horror films, both heterosexual (Falling Down) and homosexual (The Living End, Swoon), How to Make a Monster utilizes a novel approach for its monstrous aims. As Benshoff explains, “Back in the make-up lab, Pete tells Rivero of his plan to control the young actors through a special novocaine-based make-up: ‘Now — this enters the pores and paralyzes the will. It will have the same effect chemically as a surgical prefrontal lobotomy.1 It blocks the nerve synapses. It makes the subject passive — obedient to my will.'” (154). Ignoring for the moment the clearly Freudian implications of Pete’s speech, the special make-up also predicts date-rape drugs such as “mickeys” or “roofies,” thus adding another sinister aspect to the scene. Moreover, because Pete and Rivero are coded pederasts, the make-up also predicates accusations of “homosexual agenda” brainwashing leveled by the present-day Religious Right.

15. Of course, Freudian phallocentrism is never far away. Benshoff notes, “Rivero attempts to tell Pete that he thinks Pete has made a mistake in bringing the boys to his home. Pete cannot accept Rivero’s taking an active (vocal) role in the proceedings and stabs Rivero in the belly with a knife, asserting his dominance within the active/passive nature of their relationship” (156). The knife, which naturally is read as a phallus, “sends the boys into a homosexual panic: a struggle ensues and the room is set on fire. Pete dies with his melting creations á la Vincent Price in House of Wax (1953), and the cops break down the door and rescue/apprehend Larry and Tony” (156).

16. All’s well that ends well? Benshoff hedges his bets on Larry and Tony, thinking that they have probably been assimilated (he wryly adds that, before the struggle, the boys try to escape by telling Pete, “Larry and I have sort of a dinner date” [156]), but more because they have been repeatedly tainted by the monster queer. Although his overall critique of the film is favorable by citing its pleas for tolerance, he nevertheless condemns it on Marxist grounds for remaining first and foremost a product of the capitalist system. Benshoff argues that, even though How to Make a Monster attempts to subvert society’s view of homosexuals, it remains a product of a system that routinely exploits women and homosexuals. It does so by constructing their images in stereotypically specific ways and, he writes, “As such, the film contains within itself the seeds of its own destruction” (157).

17. This particular critique is borne out in his viewing of 1960s and 70s horror films, which, even with the advent of both the women’s and gay liberation movements, as well as the weakening of the Production Code, still resort to the same “tired” tropes. He selects productions from the UK’s Hammer Films (which produced horror films from the 1950s until 1973) for scrutiny, noting that “the weakening Production Code’s loosening restrictions on sex and violence helped the horror film define itself in new and explicit terms” (177), and singling out Hammer for capitalizing on this new openness. He further adds, “For the first time in film history, openly homosexual characters became commonplace within the genre, sometimes as victims . . . but more regularly as the monsters themselves (the lesbian vampire)” (177).

18. This lesbian vampire becomes a recurring motif in late Hammer films including the “first overtly lesbian film, The Vampire Lovers (1970)” (192), in which hyper-feminine women seduce and destroy other hyper-feminine women. While this is a welcome change from the stereotypical “butch lesbian” seen in earlier horror films, Benshoff cites Bonnie Zimmerman in his enumeration of Hammer’s sins: “lesbian sexuality is infantile and narcissistic; lesbianism is sterile and morbid; lesbians are rich, decadent women who seduce the young and powerless” (23). The Vampire Lovers, for example, features Carmilla (taken from J. Sheridan LeFanu’s 1872 vampire novel of the same name) seducing a bevy of “young nubile women in diaphanous nightgowns” (193) and then draining their blood. Her victim Emma, a “rather dim-witted ingenue . . . who, in all of her innocence, tumbles into bed with Carmilla after romping nude together through the bedroom” (193), is nevertheless a heterosexual. After Carmilla expresses love for her, Emma (who doth protest too much, methinks) refuses and instead asks, “Don’t you wish some handsome young man would come into your life?” to which Carmilla replies, “No — neither do you, I hope” (193). Naturally, Carmilla must be and is destroyed by, Benshoff notes, “patriarchal agents” (194) (although he doesn’t specify who these agents are) and Emma and her boyfriend Carl are reunited.

19. Benshoff astutely comments on Hammer Films’ success among heterosexual males by noting, “the appeal of these Hammer films was ostensibly directed to the straight male spectator through soft-core nudity and sexual titillation” (196). The film(s), rather than focusing on the lesbianism (although this is a significant, though unspoken, “guilty pleasure”), instead rely on “ample cleavage and sheer peignoirs” (194), and therein lies their appeal. While these nymphet vampire lesbians faded from view in the later 1970s, the scantily-clad “screaming Mimi” victims remain firmly entrenched in postmodern horror films of the 1980s and 90s, although they are primarily coded as exclusively heterosexual.

20. The advent of the postmodern horror film in the 1980s and 90s heralds a new look at old tropes, particularly the monster among us. In “Satan spawn and out and proud: Monster queers in the postmodern era,” these films, repeatedly deploying overt homoeroticism, riff on the perils of difference, repression, and (not surprisingly) coming-out, thus giving Benshoff fertile ground for exploration. For example, 1981’s Fear No Evil, a Religious Right-esque shockumentary, pits Lucifer (portrayed initially as Andrew, a shy, effeminate high-school senior before “coming out”) against the forces of Absolute Good (read: “normal” heterosexuals). The film is highlighted by a nude gym shower teasing/quasi-seduction scene involving Andrew and Tony, the requisite high-school bully figure, in which “Tony mockingly asks [Andrew] for a date, and then a kiss. Rather improbably, Tony does kiss Andrew, to the accompaniment of a rumbling, reverberating, grunting sound-track and swirling camerawork” (239, emphasis added).

21. Fear No Evil further exacerbates the thematic homosexual menace with what Benshoff terms a “retrograde ideology,” in that “When the Devil/Andrew again kisses [him,]Tony . . . manifest[s] female breasts. The implication here is unmistakably clear and totally in line with traditional notions of gender and sexuality: Devil = homosexuality = gender inversion. Upon manifesting the breasts, Tony does the only decent thing he can do . . . and stabs himself to death” (239). Stabbing, indeed, seems to be the preferred method of dispatch in horror films, and it is easy to see Tony’s action as a phallic impaling. Furthermore, it also reflects back to Larry’s and (another!) Tony’s homosexual panic in How to Make a Monster, although the postmodern Tony, who has tacitly “given in” to his homosexuality, must die.

22. Two problems, however, immediately arise in Benshoff’s reading: his use of the word “traditional” and the ignorance of the multiple kisses. His pronouncing the pairing of homosexual panic and gender inversion as a “traditional notion” would be acceptable for 1950s films but becomes highly suspect for postmodern-era films. While not to denigrate audiences of 1950s schlock-horror, audiences in the 1980s and 1990s are imbued with a cynicism that, upon viewing this ridiculous scene, would manifest itself in guffaws. Moreover, Benshoff misses or fails to comment on the view of latent homosexuality apparent in Tony. What, then, does it really say about Tony that he asks (teasingly?) Andrew for a date and then kisses him not once but twice, apparently of his own free will? Benshoff reads the scene as an overt metaphor for homosexual panic as gender inversion but fails to see the potential (positive?) societal comment that any homophobic bully is likely acting against his own homosexual feelings.

23. Additionally, given the “rumbling, reverberating, grunting sound-track and swirling camerawork” in Fear No Evil, it is surprising that Benshoff doesn’t draw a correlation between the postmodern horror film and outright pornographic films — other than the snide comment, “Apparently, the Devil really knows how to use his tongue” (239). His “Epilogue,” however, does comment on gay porno’s appropriation of vampiric themes immediately following the release of Interview With the Vampire. Indeed, these films acknowledge a number of gay pornographic productions including Does Dracula Really Suck? (1969), Gayracula (1983), and the non-porno (read: sans explicit sex) Love Bites (1988) which, Benshoff notes, “approached the generic systems of gothic horror in an attempt to draw out or exorcise the monster from the queer” (286).

24. While this reading is plausible, it problematically equates gay porno audiences with those of “conventional” cinema. The reading elides the fact that the ostensible “motivation” for any porno film is a memorable climax (and not necessarily from the film’s actors). Benshoff, however, cites Love Bites as exemplary, not for escaping the confines of porno, but for rewriting “generic imperatives from a gay male point of view” and “allow[ing] both Count Dracula and his servant Renfield to find love and redemption with modern-day West Hollywood gay boys” (286). The film, therefore, both creates a “positive” monster and aspires to mainstream appeal.

25. Benshoff concludes that mainstream postmodern horror films also show remarkable progress in the area of homosocial qua homosexual cinematic portrayals. Fright Night (1985), gay author Clive Barker’s Night Breed (1990), and “straight queer” Tim Burton’s Edward Scissorhands (also 1990) receive especially high praise for their positive attempts at positing an “alternative normal” while not resorting to stereotypical queer tropes. However, the films share the common subversive element of camp, and it is through this humor that they ultimately succeed in humanizing the monster queer. Benshoff quotes Clive Barker as stating, “We should strive to avoid feeding delusions of perfectibility and instead celebrate the complexities and contradictions that, as I’ve said, fantastic fiction is uniquely qualified to address. . . . But we must be prepared to wear our paradoxes on our sleeve” (Jones 75) and indeed, camp manifests itself as a paradox.

26. Again, however, Benshoff surprisingly misses an opportunity to view the films as critiques of suburbia and inbred suburban intolerance, for many of the postmodern films concern themselves with spinning a new urban/suburban dialectic. The urban, ostensibly viewed as the dangerous inner city (and exclusively home to black and gay ghettos) is contrasted with the idyllic (read: white heterosexual and, paradoxically, nostalgically 1950s-esque) suburban landscape.

27. Fright Night riffs on this suburban Invasion of the Body Snatcher motif, but this time the queers are clearly “out” and bent on infiltrating Fortress Suburbia. In the film, Chris Sarandon’s vampiric alter-ego Jerry Dandridge is posited as a tacitly gay antique dealer, replete with bourgeois trappings and attitudes. In other words, Jerry is tailor-made for the postmodern suburbia that Benshoff negatively reads. He subtly voices the same problematic anti-assimilationist view held by many quasi-Marxist queer theorists and activists (Urvashi Vaid, former head of NGLTF — the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force, being the most prominent) that has subsequently led to fracturing, rather than unifying, the gay “body politic.” This view is further exacerbated by Benshoff’s resigned comment that the film, “despite its fairly realistic representation of what a gay male couple in the suburbs might look like . . . nonetheless still partakes of the same demonizing tropes as do less sophisticated horror films: queerness is monstrous” (252, emphasis added). I accept Benshoff’s statement within the book’s context, but am troubled by its pessimistic implication that homosexuals can never rise out of their monstrous otherness.

28. Monsters in the Closet is by no means a perfect book. There are flashes of brilliance, humor, and dead-on cinematic readings and critiques. It is, however, balanced by often pedantic (or worse, supra-academic) jargon, generalizations, and sometimes far-fetched film interpretations. More often than not, his cinematic evidence comes through “close readings” of these horror films but reaches problematic status when he draws tenuous connections with exploitation (especially blaxploitation) and quasi-horror films (such as 1974’s Earthquake).

29. Benshoff also deploys an authorial predilection for outing that, at times, repeatedly belabors the queerness of the films. This is particularly troublesome in the first chapter, which seems more concerned with the sexualities of the stars than how they performed their roles. In later chapters, he occasionally indulges in outright finger pointing as illustrated by his noting that “many gay fans considered Tom Cruise’s acceptance of the role of Lestat [in 1994’s Interview With the Vampire] more or less a coming-out declaration” (273). While Cruise’s sexuality has been subject to continual speculation in the gay community, Benshoff’s comment adds nothing to his overall critical appraisal of the film and reads more as his own wistful and wishful fantasy. Moreover, in “Pods, pederasts and perverts,” he perplexingly hides behind the wall of murky Hollywood history when discussing older “stars like James Dean, Montgomery Clift, Farley Granger, Sal Mineo, Anthony Perkins, Rock Hudson, and Marlon Brando” whose sexualities Benshoff cautiously defines as “non-straight” (173). No Signorile he, Benshoff’s evident conflating of the terms “non-straight” and “queer” as anything outside the norm becomes problematic because it denies the definitively gay identities of Clift, Mineo, Hudson, and Perkins, thereby lessening any possible socio-political ramifications.

30. In these respects, it is ultimately weak as film criticism. However Monsters is, despite its drawbacks, a worthy entry into the field of Gay and Lesbian historical constructions. Its decade-by-decade “timeline” deftly illustrates, through the medium of film, a recurring queer presence that survives, transforms, and, against all odds (much like its monstrous counterparts), keeps popping up in the most unexpected places.

Note

1 Interestingly enough, this “device” was also used in another 1950s “real-life horror film,” Tennessee Williams’s Suddenly Last Summer (1959), about which Vito Russo notes, “Sebastian Venable is presented as a faceless terror, a horrifying presence among normal people, like the Martians in War of the Worlds or the creature from the black lagoon. As he slinks along the streets of the humid Spanish seacoast towns in pursuit of boys (‘famished for the dark ones’), Sebastian’s coattail or elbow occasionally intrudes into the frame at moments of intense emotion. He comes at us in sections, scaring us a little at a time, like a movie monster too horrible to be shown all at once.” (117).

Works Cited

Benshoff, Harry M. Monsters in the Closet: Homosexuality and the Horror Film. Manchester: Manchester U P, 1997.

Fiedler, Leslie. “McCarthy as Populist.” An End to Innocence. Boston: Beacon, 1955. Rpt. in The Meaning of McCarthyism, 2nd ed. Ed. Earl Latham. Lexington, MA: Heath, 1973.

Jones, Stephen, ed. Clive Barker’s Shadows in Eden. Lancaster, PA: Underwood-Miller, 1991.

Russo, Vito. The Celluloid Closet: Homosexuality in the Movies. Rev. ed. New York: Harper, 1987.

Zimmerman, Bonnie. “Daughters of Darkness: Lesbian Vampires.” Jump Cut 24.24 (1980): 23-24.

Contents copyright © 1998 by Nathan Tipton.

Format copyright © 1998 by Cultural Logic, ISSN 1097-3087, Volume 2, Number 1, Fall 1998.

0 notes