#Stephen Muecke

Text

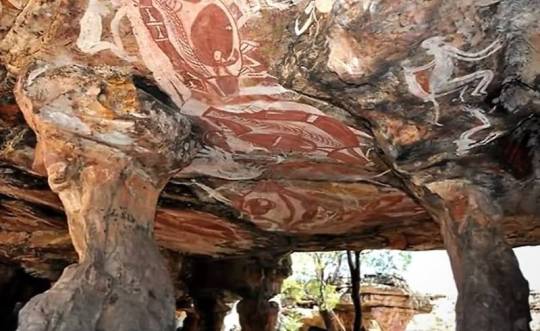

Australian aboriginal rock art at Gabarnmung.

* * * *

“Let’s hope we are learning more about the ‘arts of noticing.’ This kind of attention is not about relationships between the human brain and ‘the world out there’ but is all about immersion in living ecologies. Aboriginal people I have worked with learn about it from their elders. As children they are not encouraged to ask questions, just to be attentive. After a while they know. It is know-how more than knowledge. When an Aboriginal tracker sees things in the environment that the rest of us fail to notice, this is not a matter of a specialised psychology, but a matter of intergenerational attunement in a particular world. Noticing one thing may also depend on being attuned to many others: the sun, the wind and the way finches flock in that part of the country. It’s an art, but not necessarily an individual one. It comes in bursts, or in waves.”

~ Stephen Muecke, 'Academia Letters', November 2020

[Ian Sanders]

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ron Mueck with Self Portrait by Stephen Gill

76 notes

·

View notes

Text

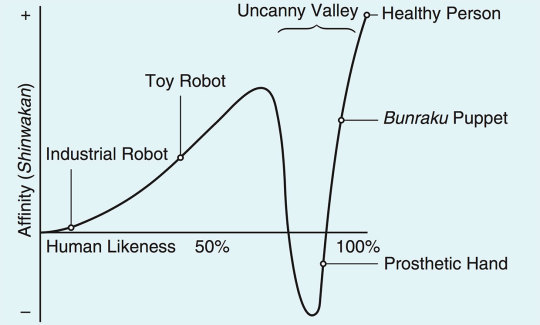

The Uncanny

The Uncanny as a term arose in 1919 as the title of Sigmund Freud’s essay exploring the junction between aesthetics and psychology. The writings explored the uncomfortable within the familiar, the blurred line that exists between the homely and human and the unnerving and alien. Some examples would include the doppelgänger, automaton, waxwork doll and mannequin, corpse and body-parts. Mirrors, abandoned houses and graveyards also are borderlands that could be considered uncanny. As a concept in art and pop culture, the idea of the uncanny has been used by writers, artists, sculptors, photographers and film makers for decades.

The Grady Twins, from Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining (1980), by Stephen King.

Laura Palmer’s doppelganger in Twin Peaks by Mark Frost and David Lynch, 1990.

The concept has also entered into science through the work of leading roboticist, Masahiro Mori, author of a 1970 paper titled The Uncanny Valley. The paper described that while increasing level of human likeness achieved in a humanoid robot’s design initially results in increasing our affinity towards it, this response is finite. Mori had recognised that at a certain level of human likeness, an android’s appearance becomes creepy and weird, resulting in a rapid drop off in affinity, termed Uncanny Valley. Although it was conceived in robot design, the graph is thought to apply to any design with a human likeness, from dolls to CGI characters.

The Uncanny Valley, Masahiro Mori, 1970.

Telenoid, an uncanny robotic communication device designed by Japanese roboticist Hiroshi Ishiguro.

Some key artists working in the uncanny:

Claude Cahun, Que me veux tu? 1929.

Hans Bellmer, (1902-1975), The Doll, c.1936.

William Eggleston, Sumner, Mississippi, c. 1969-70.

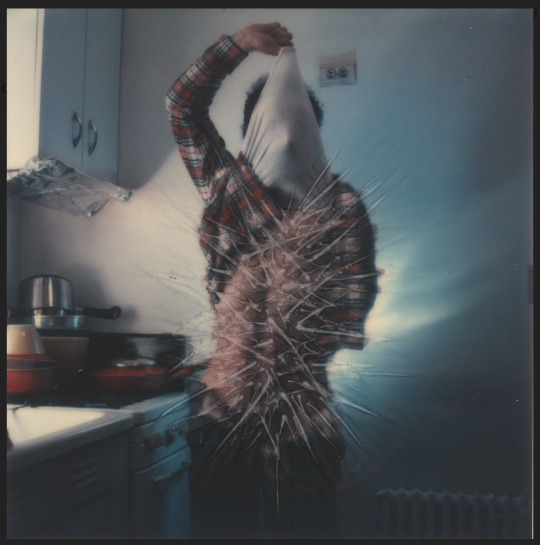

Lucas Samaras, Photo-Transformation, 1974.

Francesca Woodman (1958–1981), Untitled, from Angel Series, Rome, Italy 1977.

Cindy Sherman, Untitled #153, 1985.

Robert Gober, Leg, 1989.

Ron Mueck, Dead Dad (detail) 1996-7.

Mona Hatoum, Grater Divide, 2002.

Juno Calypso, A Cure For Death, 2018.

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Rita Felski and Stephen Muecke (eds.), Latour and the Humanities – Johns Hopkins University Press, September 2020 Rita Felski and Stephen Muecke (eds.), Latour and the Humanities - Johns Hopkins University Press, September 2020…

0 notes

Text

SPAM DEEP CUTS 2019

Hey there, it’s your favourite busiest post-internet poetry nerds! Continuing our annual tradition (check out last year’s), we’ve asked our SPAM-adjacent comrades, contributors, reviewers and editors to give us their Deep Cuts: aka favourite poetry books (pamphlets/collections/anthologies) of the year. If you feel like we’ve missed something out, why not drop us an email and suggest a review? We’re keen to hear from you!

~

Juana Adcock, Split (Blue Diode Press)

A collection of fragments, by fragments and poetic cadence felt through the varying shifting voices and remarkable inventive forms seen throughout. Juana’s meandering through different languages is seamless and adds so much breath mixed in with all its depth and humour. Split is truly a UK debut collection worth admiring. (SD)

Allison Adelle Hedge Coke, Brandy Nālani McDougall & Craig Santos Perez (ed. by) Effigies III (Salt)

Effigies III brings together four chapbook-length works by Pacific Islander poets. Kisha Borja-Quichocho-Calvo (Chamoru), Jamaica Heolimeleikalani Osorio (Kanaka ‘Ōiwi), Tagi Qolouvaki (Fijian/Tongan), and No‘u Revilla (Kanaka ‘Ōiwi) collectively present poetry as a form of connection between people, land, Indigenous languages and ways of knowing. The anthology also shows the range and movement within as well as between the writers’ bodies of work, interweaving vernacular address, creation stories and stories, found text and lyric description for a glimpse into the multiplicity of contemporary Pacific Island poetry.

Body and environment are inseparable in this book; as Qolouvaki writes, ‘all flesh and fluid mouths / feed’ and ‘all rivers snake / rivulets in earth’s flesh to the ocean’s arms.’ However, all undergo trauma through colonisation and its after-effects – from the sugar plantations and gendered violences ‘shattering, shattering’ generations of women in Revilla’s poems to the ‘SPAM-crazed golden arches’ of Borja-Quichocho-Calvo’s militarised Guam.

Yet poetry is part of decolonial struggle across the anthology’s wide-ranging genealogies of resistance. In ‘Kaona’, co-written with Ittai Wong, Osorio writes: ‘Ua ola ka ‘ōlelo i ka ho‘oili ‘ana o nā pua’ or ‘Our language survived through the language of flowers.’ ‘Kaona’ means ‘hidden meaning’ and the lines refer to the way that Queen Lili‘uokalani, overthrown and imprisoned by white Americans in 1893, continued to communicate with the Hawaiian people through richly allusive poems, songs and stories in newspapers wrapped around flowers.

Since July 2019, Native Hawaiians have been protecting the dormant volcano and sacred mountain Maunakea against the construction of an astronomical observatory known as the Thirty Meter Telescope (TMT). Kia‘i (protectors) successfully blocked the TMT construction in 2015, and poems by Osorio and Revilla from that time and included in Effigies III echo forwards to the present moment and backwards to longer trajectories of resistance; as Osorio puts it, ‘new roots sprouting from old seeds’. (KLH)

Rachael Allen, Kingdomland (Faber)

Kickstarting the year with enticing orange and the kind of lyrics that sizzle off the end of your tongue, Rachael Allen’s debut collection is teeming with cortisol spikes of visceral imagery, weird ecology and gendered shame. This is anthropocene poetics put through the meat grinder and released in slices of elegance, myth and bittersweet longing. (MRS)

Sophia Al-Maria, Sad Sack (Book Works)

I received this as a birthday gift from a trusted poet friend, the best anthropocene thinker I know. Sad Sack is the collected writings of artist and writer Sophia Al-Maria, a compendium of performances, poems, conversations, letters and art criticism. Think Ursula Le Guin’s ‘carrier bag theory of fiction’, endocrine disruption, anime, Gulf Futurism, jpeg poetics and Alice Coltrane filtered through the astral planes of late capitalism, presented on delectably acid-green paper. (MRS)

Fiona Benson, Vertigo & Ghost (Jonathan Cape)

cn: trauma, sexual violence, r*pe

Fiona Benson’s unsettling collection Vertigo & Ghost reimagines the figure of Zeus as a serial rapist. Taking much from Anne Carson’s (anti-)translation of Sophocles, Antigonick, Benson ventriloquises mythical characters through a contemporary feminist lens. Through this practice, the poet gives voice to previously silenced characters, remoulding ancient narratives to explore the seeming unspeakability of sexual violence. Riddled with classical allusions and manifestations of ancient figures, alongside contemporary references to the bleak, Trump-era political climate, Benson’s verse turns from a devastatingly sensual account of the violence of patriarchy to a study of the natural world. Through a series of delicately observed images, she explores the guttural, gory, yet utterly joyous experience of birth and motherhood, as well as the sheer aliveness of the natural world around us. Vertigo & Ghost is an extraordinary collection, coupling almost unutterable trauma and despair with a hope that persists despite the raw, unflinching bleakness of the early poems. (MS)

Lauren Berlant and Kathleen Stewart, The Hundreds (Duke University Press)

Maybe you’re technically not meant to say this but I do have a favourite book of this year and it is undoubtedly The Hundreds. Perhaps this is because I read this book in the last few weeks of this year, knowing it came out in January 2019 (and in its multitudes, it does seem to brilliantly reflect this year of confusion). Perhaps it’s because this is totally a book of collaboration and this in itself feels like a rebellion against isolated thinking and easy power structures. Or perhaps, it’s because the words/stories/thoughts/images just felt so real and familiar, with theory and prose and poetry coming together to explore the micro- the small tender thoughts, instances and conversations as the most expansive moments of thinking. I could go on and on about the ideas, excitement and energy generated by this book but I also might describe it as a constellation of prose poems on a diverse range of topics, that have been ascribed a specific rule: they must be written in units of a hundred and there are a hundred of them (side note: in a recent podcast interview with Lauren and Kathleen- go listen!- I found out that the word ‘hundred’ also pops up a hundred times!). The playfulness and satisfying quality of this rule-making by Lauren and Kathleen, combined with the fact we do not know if they wrote these small pieces together or separately, gives a sense of spontaneity to the words (I think this is captured beautifully in the opening piece ‘First Things’ which is a poetic exploration and interrogation of how we all encounter the world differently at the beginning of the day and the nakedness of this awakening). At the end of each short piece, there are references to other sources, which we guess must hint at what they were inspired by and/or reading at the time of writing; from theorists such as Freud, Deleuze, Sedgewick, Moten to more ambiguous concepts such as weak links, and quotidian ambitions (to give a very brief example- there are hundreds!). Lauren and Kathleen also asked other creative writers and thinkers- Fred Moten, Andrew Causey and C. Thresher, Susan Lepselter and Stephen Muecke - to provide their own creative indexes/interpretations of the book which are incredibly various in both form and ideas. They also wrote their own incredibly open ‘For Your Indexing Pleasure’; combined with their own collaborative creative pieces, this reaching out in the book brings a vastness to these micro pieces; it inspires you to go out, find these books, interrogate concepts that underpin Lauren and Kathleen’s words and just explore, explore, explore! It’s also a book that asks for more writing; this is part of the excitement of the reading experience. The Hundreds is asking you to set your own rules, to have more open discussions, embark on more collaborative projects and see what comes out of all that. It’s a conversation and the pages are filled with choice. I keep dipping back in, unable to resist the re-reading! (KD)

Jay Bernard, Surge (Penguin)

Recently, like many poets, I’ve been more and more vexed by the Lyric ‘I’. Part of the brilliance of Jay Bernard’s Surgeis their skilful reworking of this tradition. Rather than one speaker uttering an assumed universality, Surge’s beautiful, painful, celebratory ‘I’ slips effortlessly across bodies and histories. And this multiplicity continues with the inclusion of archive material and song alongside Bernard’s poetry, and of music, film and dance into their exceptional performance. Surge explores the events surrounding the New Cross Fire, before echoing these moments with the aftermath of Grenfell and today’s political climate. It is a collection that balances universal feelings of loss and love with the specific experiences of one black British community.

In a Q&A after their recent October performance of Surge in Glasgow, Bernard commented that in the ‘personal and political’ people often forget about the ‘and’. This is a collection filled with that ‘and’, which is questioning and complex and human. What results is a moving interrogation of the relationship ‘between public narration and private truths’. (EB)

James Byrne, The Caprices (Arc Publications)

A book of poetry that exists as a dialogical conduit and response between the 18th century Spanish artist and poet James Byrne, this collection consists entirely of ekphrasis poems situated alongside their corresponding picture. This book wonderfully bridges the gap of centuries by mirroring events, thoughts, politics and so much more that prevails in the impressions then, ‘Now that the state legitimises hate, / a wakeful trump of doom thunders / valley deep? (Where are the Blake’s/ and Miltons now?). Crises of mirrors / where my neighbour reasons only / with himself’, and now. The book drifts through the dark tones derived from Goyer’s uncertain life (explored in the preface) and how a contemporary poet is able to (or could?) respond to art to create more impressions from that same existing parallel space. (SD)

Vahni Capildeo, Skin Can Hold (Carcanet)

Among the major collections of Vahni Capildeo, I have to admit Skin Can Hold is my personal favourite. It is Vahni’s genius surfacing outright, in a solemn collection that left me wondering how some of the poetic measures were even achieved. Broken up into 6 segments, the 6 part poem ‘I am no Soldier: Syntax Poem’ resonates as a deep connection for me:

II

you fall I shall arise

there will I come

I am no soldier

I am my poem. I come to you.

It masterfully moves between so many forms that the brilliance for any voyager en-route is immediately palpable. (SD)

Tom Crompton’s bait-time (Distance No Object) and Caspar Heinemann’s Novelty Theory (The 87 Press)

The two poetry books which have probably most fucked up and affirmed the way I think and write this year are Tom Crompton’s bait-time (Distance No Object) and Caspar Heinemann’s Novelty Theory (The 87 Press). Both books get things done on the fly very distinctly, hitting you in the lungs and stealing time, anti-work vernaculars extemporising far more wittily and with far weirder, scrappier resources and gestures than most poetry collections I’ve read recently. They make a lot of stuff look static, mannered, po-faced and weary: irradiated surpluses bursting from the undercommons right against the things we loaf among. (DH)

~

You can think of bait-time as poems of the hyperlocalised everywhere. These are fugitive sequences that take aim at 'escapism from the need-chain', instead relishing in imagining new urgencies, touching off everywhere, moving to and from all the ‘festering particulars' of objects and attitudes woven deep into speech: it's defo something / it's all gonna be okay, lynx-clouds, dogrolls, canto grease, mini-motos, ash-crag, silk profiles. Bait-time is full of the thick matter of life lived in language, a rich rendering of the formations and deformations that happen in any type of collective work; even one as simple as just being together.

And as all this is happening, bait-time is more optimistic in poetry and 'the ambient' than anything else I read this year. It is aware that 'vocal geometry is not / social geometry', that alignments of sound, sense and occasion do not translate into prefiguration nor do they have to. Instead it gathers friends 'called / to articulate nothing' and delivers a reverie of pissing about, ludic and critical, a woodpecker or drill-bit. I’ve returned to bait-time, over and over, in the joy of its unfoldings and its attention—somewhere between documentary and free play. It is fieldnotes for catching voices and objects in interaction and never letting them sit idle, irreverently made against the powers that would compel quietude and contemplation. (MB)

Ellen Dillon, Sonnets to Malkmus (Sad Press)

A baroque paean to Pavement singer and indie hero Stephen Malkmus, Sonnets to Malkmus elicits a fabulous desire to indulge in one’s longest standing fandoms and make them into collaborations. It raises the possibility of taking in the world with all the idiosyncrasy and the impossible fun of co-habiting someone you love.

Ellen Dillon has produced a unique recombinatory sequence modelled after Rilke’s Sonnets to Orpheus and generated out of various acrostics of Stephen Malkmus’ name, lines and near-titles from Pavement songs. Churning out the palette of Pavement’s California surrealism into tender parataxis, the sonnets are endlessly imperative and present, with sound patterns that make them irresistible to read as you are led down into and back out from the underworld, accompanied by Malkmus, Dillon and all the singers who make of language something of a divine world for us to take part in.

Make it count quiet sound-booth

as both us smother a groan

leaving time to be marked a rest or pause

keeping beats & company bad

(MB)

Teddy Duncan Jr, An Absolute Study (death of workers while building skyscrapers)

Lucy Wilkinson’s press death of workers while building skyscrapers is doing amazing things around intimacy, affect and the small press. One of their recent titles is Teddy Duncan Jr’s An Absolute Study, which is a heady kaleidoscopic slice of collaged realism. The language is intense, fudgy, even fishy: ‘the bank of justice is bankrupt’; ‘toilet flushes and the rank odor’d person groans’ ; ‘Orlando’s tallest buildings reach for the grey storm sky’. It’s punctuated by photos, forms, medication. In other words it’s all the pharmacy has to offer: sweet sour poison... it’s oh so good. (CH)

Cathy Galvin, Walking The Coventry Ring Road with Lady Godiva (Guillemot Press)

In my corner of the literary internet (read: echo chamber) 2019 has been the year of psychogeography, and Cathy Galvin’s Walking The Coventry Ring Road with Lady Godiva is a gorgeous trip through Coventry’s turbulent past. There’s a discipline to Galvin’s verse – her poems sit in nice, ordered forms, with a regular metre and rhyme that’s pleasing to speak aloud:

Beside me in the Cheylesmore underpass,

she took my hand and said: Abandon fear.

Sky Blues in red Doc Martens threw their cans

and punks in two-tone sang their ghost town near.

Lady Godiva guides the narrator in a circuit of the city, following 'a road, a river, a prayer'. Coventry was bombed almost entirely to rubble in the Second World War, and ring road is as much littered with the 'melted bodies' of war dead as plastic bags and cans of K. As I say, I’ve been well on psychogeography this year and I like poetry that wants to dig up the past, shake it up, and show us the parts 'where goddesses wielded canes.' Galvin says her poems are dedicated 'to the people of Coventry', and I think it’s important to democratise history – make heritage accessible, not just something idiots can use to justify bad politics.

Also – referencing Dante’s Inferno and The Specials in the same stanza? Inject 👏 that 👏 into 👏 my 👏veins. (JP)

Colin Herd, You Name It (Dostoyevsky Wannabe)

I’ve said it once before and you know I’m going to say it again: I like to think of this collection as the luxurious bubble bath we all really do need right now. Released in late November by the brilliant Dostoyevsky Wannabe, this is the bubbling, overbrimming collection of poems that not only explores bubbles (of all kinds) but is capable of turning you into a bubble, into many bubbles; sending you flying, expanding and colliding across poems of queerness, soggy nightmares, yoghurt, fanciphobia, apples and Bubbles (the unforgettable character). Colin is one of the most giving poetic thinkers I know: a brilliant advocate of other writers’ work and a creative writing teacher and this collection reflects just that: these are generous, intimate poems that will make you want to spark up conversations with Colin about queer bubbles, foam, the Fancy, found poems, the embarrassing, the ridiculous, the surface and the depth, and the very real. These are micro, powerful bursts of warmth (also reflected beautifully in that orangey red combo on the cover). It’ll make you want to write your own bubbling words; it’s a poetry book for you, you and you. For a more detailed peek at Colin’s expansive imagination and thinking behind the book, have a wee read of our recent SPAM interview! (KD)

Wayne Holloway-Smith, Gravy (If a Leaf Falls)

Holloway-Smith’s Gravy is joyous. Its edible imagery weaves through the entire collection, from Yorkshire pudding, to cupcakes to the gelatinous love that is gravy. The poem comments on itself as it is being written and being read, creating the illusion of simultaneity and a glimpse inside the moving gears of the speaker’s mind. ‘Does this moment fully earn its place / within the rest of the collection’ the speaker asks, without the use of a question. The only punctuation Gravy allows is an occasionally used dash and this negation of a forced reading allows the words in each verse to flow from the initial capitalised letter, through to the end with nothing to impede their course—only the textured, guttural voice of the speaker remains. The speaker is uniquely impartial and self-flagellating in their anxiety over the perceived form of the very poem they are currently in the act of telling by the eventual reader. This collection is to be devoured quickly and then begun again to be devoured again and again, each reading bringing new texture and new tastes. ‘Yorkshire pudding are the best we / might hope for in this context’. (MGT)

Isaiah Hull, Nosebleeds (Wrecking Ball Press)

A brilliant, highly pressurised collection of poems that gush forth in what I think of as an otherworldly powers of horror sputter. Hull’s language pulls from all sorts of different discourses. There’s a poem called ‘Money’ in which is written: 'sweating cross the table long / neutered of his colloquial / Alex the accountant winks / complimentary water boy' - I just find this so weird and heady. At the start of the collection there’s a kind of invitation: 'a nosebleed is the first time you feel alien to yourself.' Well this poetry is language that makes you feel alien to yourself and that draws attention to the ways in which one gets alienated. The poetry is iron-rich, witty, precise, full of pathos and bathos to chew on and clot: 'Isn’t there a solar eclipse due / never mind'. (CH)

Harry Josephine Giles, The Games (Outspoken Press)

Wow - brilliant, funny, wickedly intelligent. Deadly serious. Loved the dry humour, stopped in my tracks by the political acuity. The feel for mendacity, the lies of public life, the cover ups, the forked tongues (is anything else more ‘2019’?). The weirdness of agriculture makes this fantastic eco poetry (what is it that we are farming? Still ploughing for verse). ‘Thing-Prayer’ seems pure Jane Bennett. Feels Scottish in the very best way (echoes Morgan, Leonard) with its wry slants on the English language. Although often (literally) punchy in its imagery, these poems are careful, surprising, touching negotiations of human feeling in the twilight world between the representation and the real. A real possibility-expander for me, loved it. (RW)

Petero Kalulé, Kalimba (Guillemot Press)

Bright yellow and full of music, murmur(ation), and the ‘blue pressings of more-ear’, Kalimba takes playing and listening seriously, commoves you to expand y/our range.

Words break at the bent note of a phoneme, the overdetermination of a poem’s ‘sakura f / low’ until:

s tumbling

it’ll reak, lines

in

dial loop

The poem as joy-noise and swung mood along wavelengths beyond the individualised body: ‘rain is a nectarous smirrle of petrichor, a giddyfizz of grass weeping, silent; bestilled .’

This is the kind of book you want to send to all your friends before you even get to the end. (KLH)

Ilya Kaminsky Deaf Republic (Faber and Faber)

In such times of political turmoil and insecurity, this collection stands as a collective symphony for those struggling to find a voice. What resonated with me in particular was the beautiful harmony between the tenderness of the characters against the backdrop of the tumultuous settings, mixing in varying crescendos hovering over different arcs. Literary activism at its staggering best, Deaf Republic reaches an operatic catharsis which left me motivated to not reside as just a silent bystander who simply ‘lived happily during the war’. (SD)

Katy Lewis Hood, SWATCH (glyph press)

The debut pamphlet from Midlands poet and critic Katy Lewis Hood (co-editor of amberflora) was a covetable hit, selling out in just a day or two. Lovingly stitched and bound in forest green, these patch-poems respond to Pantone colours while defiantly flying in the face of the company’s unfortunate decision to brand 2020 the year of tory ‘Classic Blue’. This is a tactile, thick, entangled poetics of care, harm, beauty, resilience, sense and elements. Although sold out, you can contact the poet or publisher for a pdf copy. (MRS)

Dorothea Lasky, Animal (Wave Books)

Whenever I’m feeling lethargic or jaded in life I listen to Dorothea Lasky give a lecture on poetry. She makes the act of intellectual delivery a participatory democracy of shimmer and strangeness and song. Animal is a compilation of Lasky’s poetry talks given as part of the Bagley Wright Lecture Series: encompassing topics such as ghosts, colours, animals and bees. It’ll make you feel wild and luminous in the middle of winter. (MRS)

Kirstie Millar, Curses, Curses (Takeaway Press)

Kirstie Millar’s pamphlet Curses, Curses features a series of poems that explore pain and the body, with illustrations by Alice Blackstock. From a utopian society where women evolve into centaurs, to a futuristic facility called The Institute For Secret Pain, where women unzip from their skins and meet their cures, the pamphlet situates women’s pain within a magical realist context, as a way of shedding light upon the lived experience of chronic illness.

However, it is the final poem ‘The Curse’ which I found to be the most striking. Reminiscent of the work of Carmen Maria Machado, and even Atwood’s Alias Grace, the poem comprises the diary entries of a young girl approaching menarche. One of the most nuanced explorations of menstruation I’ve read, the poem illustrates the conflict which arises when one’s body starts behaving against one’s will. (JH)

Iain Morrison, I’m a Pretty Circler (Vagabond Voices)

A beautiful gathering in of voices - Emily Dickinson, Belinda Carlisle, Frank O’Hara. Some short, but many chatty and meandering in the best way, explosions of words in my ears.. Such a firm but gentle feel for modern sensibility – its moments of swagger, its more usual second-guessing, going over, rehearsing, looking back. Great warmth and tenderness, and humour, so humane (‘It came out that that was about my father having nearly died | and the tears rolled down my cheeks and I felt woozy. | Maybe I should drink even more water.’) Brilliantly experimental poem generation, letting loose yet fantastically precise at the same time. Loved the skittish range of cultural references, and both the muffling and revelation of meaning. So glad I’ve read this! (RW)

Nisha Ramayya, States of the Body Produced By Love (Ignota Press)

Nisha Ramayya’s long-awaited debut is a startling collection that twists around poetry, notes, essay, image and song, by way of Tantric ritual and myth. Open it and you’ll release a jazzy, prismatic assemblage of goddesses, honey bees, Sanskrit, sound, infatuation and shame. Something to incant: a book of pleasure and the sacred, love and study. (MRS)

Ariana Reines, A Sand Book (Tin House Books)

The back blurb of Ariana Reines’ gilded slab of a collection reads simply, 'Mind-blowing'-- Kim Gordon. Gordon’s eloquent abrasions of noise rock is a fitting counterpoint to Reines’ luminous, uncompromising book of mourning, climate crisis, traumas of the state, gender violence, prophecy and love. Some of these lines bounce out of the sand like jewels. Give to your best friend; give, give, give. (MRS)

Roseanne Watt, Moder Dy | Mother Wave (Polygon New Poets)

Written in English and Shaetlan, the language spoken on the Shetland islands:

Really superb feel. Pared down, elegant, curious. I loved the sense of stone, of animal, of the land as sentient, of its agency - of its meeting with the poetic voice here (‘Out here | is where the dirt | is listening-in.’). Aching senses of loss, regret, grief, but moments of vivid life too (‘the doors of our house | all the rooms | they opened on’). Terrifying episodes of bodily possession - indeed, the sense of the body here is remarkable (‘a soft cling | of sinew at the absent body’s | join’) - and such a committed weighing of Shaetlan words in the mouth. Wonderful. (RW)

Jay G Ying, Wedding Beasts (Bitter Melon)

My favourite single pamphlet of the year, Wedding Beasts carries the reader on a journey through so much grief, conflict and finality, addressing personal and societal structures and spaces in attempts to find or make a semblance of meaning from it all. Sewn in with fantastic lines of clarity that prevails from the search:

'I watched him unstitch every hole like an order from the

for the newly felled muslin threads'

'All your ancient and future bodies crowded the unbuilt rooms in my dream'

This poem unravels itself like a beautifully woven tapestry. This pamphlet from Jay G Ying needs to be held and read (credit to the publishers for its stellar design and aesthetics) and held again that much closer. (SD)

~

Thank you to this year’s contributors, Mauricio Baiocco, Eloise Birtwhistle, Shehzar Doja, Kirsty Dunlop, Dom Hale, Jane Hartshorn, Colin Herd, Katy Lewis Hood, Jon Petre, Marina Scott, Maria Rose Sledmere, Meredith Grace Thompson, Rhian Williams. We’d also like to thank all the amazing publishers that keep making these pamphlets happen. Solidarity <3

~

Illustration: Maria Sledmere

0 notes

Text

The Hundreds - Lauren Berlant & Kathleen Stewart

The Hundreds

Lauren Berlant & Kathleen Stewart

Genre: Anthropology

Price: $23.99

Publish Date: December 21, 2018

Publisher: Duke University Press

Seller: Duke University Press

In The Hundreds Lauren Berlant and Kathleen Stewart speculate on writing, affect, politics, and attention to processes of world-making. The experiment of the one hundred word constraint—each piece is one hundred or multiples of one hundred words long—amplifies the resonance of things that are happening in atmospheres, rhythms of encounter, and scenes that shift the social and conceptual ground. What’s an encounter with anything once it’s seen as an incitement to composition? What’s a concept or a theory if they’re no longer seen as a truth effect, but a training in absorption, attention, and framing? The Hundreds includes four indexes in which Andrew Causey, Susan Lepselter, Fred Moten, and Stephen Muecke each respond with their own compositional, conceptual, and formal staging of the worlds of the book. http://dlvr.it/R1VBRV

0 notes

Link

L'origine des mondes culturels |Uluru ou Ayers Rock est un imposant rocher situé au centre de l’Australie, dans le Territoire du Nord. Lieu incontournable du tourisme sur le continent, c’est avant tout un site sacré pour les peuples aborigènes vivant dans cette partie du désert australien. Son ascension est désormais interdite.

C’est un symbole de l'Australie, une de ses représentations dans le monde entier : le rocher Uluru ou Ayers Rock dans le Territoire du Nord. Les touristes sont environ 300 000 à s’y presser chaque année, certains n’hésitant pas à escalader le mastodonte de près de 350 mètres de haut. Mais pour les peuples aborigènes présents dans cette région, ce site est avant tout sacré, témoin de leur histoire. À partir de ce samedi, l’ascension du rocher est donc interdite. Les autorités ont dénombré une trentaine de morts depuis les années 1950 lors de l’escalade du mont, réputée dangereuse, en raison de la difficulté physique de cette montée et de la chaleur qui y règne.

La montée du rocher désormais interdite

Ce 26 octobre 2019 fera une nouvelle fois date pour le peuple aborigène. Il y a 34 ans jour pour jour, le site d'Uluru leur a été rendu, après des années de combat. À partir de ce samedi, c'est l'ascension du rocher qui est désormais interdite, comme les Anangu, propriétaires traditionnels, le réclamaient depuis longtemps.

Vendredi, à la veille de l'interdiction de l'ascension, des centaines de touristes ont tenu à escalader une dernière fois le rocher, après avoir parfois attendu plusieurs heures l'autorisation de monter, une fois les vents violents passés. Un touriste polonais a ainsi expliqué à l'AFP juger "normale" l'interdiction d'escalader Uluru. Mais après avoir appris que c'était la dernière fois qu'il pourrait faire l'ascension, il a tout de même souhaité "essayer".

L'approche de l'interdiction d'escalader Uluru a provoqué un afflux de touristes ces derniers mois. Entre juin 2018 et juin 2019, plus de 395 000 personnes ont visité le Parc national, soit 20% de plus que l'année précédente, d'après Parks Australia. Toutefois, seuls 13% de ces visiteurs ont fait l'ascension, rapporte l'AFP.

Un site découvert il y a moins de deux siècles par les colons…

"Tout ce que l’on peut dire au sujet d’Uluru ne remplacera jamais ce que vous y découvrirez par vous-même." Ainsi est décrit dans le guide touristique du Petit Futé le rocher majestueux qui s’élève au milieu du désert australien. Le monolithe en grès de 348 mètres de haut et de 9,4 kilomètres de circonférence est entouré d’histoires sacrées. Un côté mystique renforcé par sa couleur rouge orange qui change en fonction du soleil, tournant au violet à la pénombre.

youtube

Si ce lieu a toujours fait partie du quotidien des peuples aborigènes qui vivent dans le désert depuis des milliers d’années, les colons ne l’ont découvert que récemment. Il a pour la première fois été aperçu en 1830 par des caravanes qui exploraient la région. Le site n’a été mentionné qu’en 1872, alors que les colons construisaient une station de télégraphe à 400 kilomètres de là. Les colons le baptisent alors Ayers Rock, du nom du Premier ministre d'Australie-Méridionale de l'époque, Henry Ayers.

"Il y a eu des massacres, une guerre de frontières, explique la linguiste et maîtresse de conférences à l’université d’Australie de l’ouest (Perth) Maïa Ponsonnet. Les blancs venaient pour exploiter essentiellement les terres. Puis dans les années 1950, les Aborigènes ont été parqués dans des réserves, c’était des années extrêmement difficiles pour les populations locales". C’est à cette période que les touristes commenceront à venir à Uluru. En 1985, la propriété du parc a été remise à ses propriétaires d’origine, les Anangu. Deux ans plus tard, Uluru est inscrit au patrimoine mondial de l'Unesco puis au patrimoine culturel en 1994.

Dès le départ, la question de monter ou non sur Uluru s’est posée. En 2016, dans l’émission de France Culture "Les Hommes aux semelles de vent", l’anthropologue, directrice de recherches au CNRS et chercheuse au Laboratoire d’anthropologie sociale du Collège de France Barbara Glowczewski déclarait : "Il faut imaginer l’Australie comme un immense réseau, un maillage de milliers de parcours qui relient des centaines de groupes de langues différentes au moment de l’arrivée des colons. Tous les lieux qui apparaissent aux Occidentaux comme naturels sont en fait culturels pour les Aborigènes. (...) Tout le continent australien est considéré comme appartenant aux Aborigènes dans une relation qui est réciproque, c’est-à-dire qu’ils disent aussi qu’ils appartiennent à la Terre."

À partir du 26 octobre 2019, plus personne ne pourra grimper sur Uluru, comme le demandent les Aborigènes, par respect pour leurs croyances, depuis des dizaines d'années• Crédits : Reinhard Kaufhold - Maxppp

C'est ainsi que pour Uluru,"les populations gardiennes du lieu ont demandé que les touristes ne grimpent pas sur ce rocher. Pendant les vingt premières années après sa restitution [à ses propriétaires d’origine, ndlr] dans les années 1980, cet interdit a été respecté. Les touristes pouvaient acheter dans une boutique de souvenirs des badges disant ‘Je ne suis pas monté sur Uluru’. Cette année [en 2016], cet interdit n’est plus respecté." Il aura donc fallu des années de lutte et une trentaine de morts pour que l’interdiction soit définitivement validée. Pour l’anthropologue et chargée de recherche au CNRS, spécialiste de la Terre d’Arnhem et des sociétés aborigènes, Jessica De Largy Healy, la montée des touristes a aussi eu des conséquences écologiques pour le rocher, un chemin a été tracé et une chaîne pour faciliter la montée installée.

La linguiste Maïa Ponsonnet estime qu’Uluru est devenu une sorte d’icône de l’Australie indigène "mais que c’est une manière très occidentale de percevoir l’Australie indigène".

C’est un symbole qui est aussi valorisé dans un contexte touristique, économique et donc c’est une manière pour l’Australie coloniale, blanche de réinvestir dans son capital indigène pour faire profiter d’un certain versant de l’économie… Ce côté à la fois monumental physique et culturel, antérieur à la colonisation, est réinvesti dans le symbole touristique d’Uluru.

Maïa Ponsonnet, linguiste et maîtresse de conférences à l'université d'Australie de l'ouest

À ÉCOUTER AUSSI

Réécouter L'économie du voyage (4/4) : Le voyage contre le tourisme

57 min

Entendez-vous l'éco ?L'économie du voyage (4/4) : Le voyage contre le tourisme

…Mais sacré depuis des milliers d’années pour certains peuples aborigènes

Difficile donc d’évoquer Uluru comme un symbole de l’histoire aborigène. _"Le terme ‘symbole’ réduit la réalité et le pouvoir de ces endroits sacrés et de leur histoire, à la fois humaine et non humaine"pour Barbara Glowczewski. Et il est difficile de qualifier l’histoire aborigène d’unique. Car en quelques 80 000 ans de présence en Australie ("d’après des découvertes archéologiques très récentes"_ selon Barbara Glowczewski), il existe autant d’histoires que de peuples sur le continent (et il y a plus de 300 langues différentes).

D’ailleurs, comme Uluru, "des milliers de sites sont sacrés en Australie pour les différents peuples qui en sont les gardiens" ajoute l’anthropologue. "Ils correspondent toujours aux traces laissées par les voyages d’ancêtres totémiques sous forme de rochers, de collines, de trous d’eau, de lit de sable, des ruisseaux, de carrières de pierres de taille, de gisements d’ocre ou de minéraux". C’est pour cette raison qu’Uluru et Kata Tjuta (les Monts Olga) sont sacrés, pour les Anangu ainsi que pour "d’autres peuples comme les gardiens du Mala*, dont les Warlpiri qui vivent plus au nord dans le désert Tanami et qui sont liés par des échanges rituels avec les Anangu" ajoute l’autrice des Rêveurs du désert (Actes sud/Babel). C’est la connexion des "rêves totémiques" ou Dreamings de ces peuples à Uluru qui en fait également un site sacré pour eux.

* un petit marsupial qui était en voie d’extinction et se reproduit à nouveau grâce un programme mis en place avec des rangers aborigènes

Le paysage comme patrimoine culturel

Dans leur livre Les Aborigènes d’Australie, Stephen Muecke (professeur émérite d’ethnographie à l’Université New South Wales de Sydney) et Adam Shoemaker (vice-chancelier de South Cross University, spécialiste de la littérature et culture aborigène) racontent ce Dreaming (qui a aussi été appelé Dream Time) qui entoure Uluru.

"Uluru est l’un des sites sacrés les plus importants pour les Aborigènes de la région car il fut le théâtre d’une terrible bataille entre les Kuniya (les Pythons des Rochers) et les Liru (les Serpents venimeux) qui marqua la fin du temps du rêve et inaugure l’âge des hommes."

En Australie, les Aborigènes considèrent que "le paysage contient la trace des événements du temps du rêve. Les récits parlent des ancêtres et de la création des caractéristiques de l’espace en expliquant la raison d’être de chaque élément du paysage (arbre, source, rocher). Les rêves ou héros totémiques qui ont parcouru le paysage et qui ont créé les sites en y laissant leurs empreintes sont associés à cet espace. Ainsi, l’espace n’est pas seulement une étendue géographique mais véhicule une signification religieuse et identitaire particulière (…) Les reliefs et les lieux ainsi désignés par les rêves constituent _le patrimoine culturel et spirituel des Aborigènes_. Chaque Aborigène en tant que descendant d’un ancêtre possède un lien spirituel avec un territoire et des sites donnés. Ce lien inaliénable et intransférable dans un autre lieu lui confère sa qualité et son devoir de gardien."

youtube

Les Aborigènes estiment ainsi que les esprits de leurs ancêtres sont toujours présents dans les lieux qu’ils ont formés, notamment à Uluru. "Ces sites ont donc un certain pouvoir, relate l’anthropologue Jessica De Largy Healy. Ce pouvoir va être canalisé durant les cérémonies faites par les Aborigènes pour permettre le renouvellement de la vie, le cycle de l’environnement, etc. Il y a sans doute toute une série d’êtres ancestraux qui ont des histoires associées à ce lieu et c’est donc un site sacré."

Pour se transmettre leur histoire, les Aborigènes utilisent ces cérémonies. En témoignage de leur présence sur les lieux, les Anangu ont aussi laissé quelques peintures rupestres. Généralement, elles ont été dessinées grâce à des minéraux naturels et des cendres. Mais ces peintures sur le rocher ont été abîmées par le temps. Le tourisme n’a pas arrangé les choses : lorsque les premiers touristes sont arrivés sur place, certains guides avaient même pour habitude de jeter des seaux d’eau sur les peintures pour raviver les couleurs sur leurs photos en noir et blanc. Sur ces peintures que l'on ne trouve pas seulement à Uluru mais dans plusieurs régions d'Australie, "des références aux origines, aux êtres ancestraux qui avaient une forme humaine et animale et qui au cours de leurs itinéraires dans le paysage se transformaient sont dépeints", d'après la chercheuse Jessica De Largy Healy. Mais la signification de ces peintures reste, elle, secrète, comme de nombreuses zones à Uluru où les Aborigènes ne transmettent leur histoire et leur culture qu'à un petit nombre d'initiés.

0 notes

Photo

Another science is possible : a manifesto for slow science / Isabelle Stengers ; translated by Stephen Muecke.

0 notes

Photo

Scallywag Reading 2017

I‘m surprised that a book was opened at all this year. So much of my time is reading online, so it seems a triumph of sorts that I am still managing to read books at all. It is not possible to do justice for all books mentioned here individually. They all add up to the string of pearls that sustains me in some sort of equilibrium and continues to provide threads to places that only a particular book can reveal, at the particular time you are reading.

Some of the books here were chanced on in bookshops. You never regret time spent in bookshops. There didn’t seem enough time this year though to enjoy this gentle past time. Which is probably a good thing for me, as I truly have enough books at home to read already. My daughter tries to stop me adding to my collection all the time. Can you imagine taking off one day, just to visit all the bookshops in the world?

One day this winter, heading down Bourke St after a meeting, I stepped into The Paperback Bookshop. There I chanced on a book of poetry by anthony lawrence called headwaters.

It has the lines

‘Her dreams have night vision, and in her sight

Our bodies leave a ghostprint where we’ve laid.

My darling turns to poetry at night

Between abstract expression and first light.’

I’ve just finished You Don’t Have to Say You Love Me - A MEMOIR by Sherman Alexie. Hard not to proclaim this book loudly enough. Strangely the book’s poetic, diaristic chapters look superficially like the incredible work of American fiction I read this year called Lincoln in the Bardo. Perhaps the Trump-dark atmosphere of 2017 made George Saunder’s romp with the ghost of Lincoln’s past presidential time and place so strangely alluring. (The book was purchased with intelligent guidance from Readings’ Acland St staff.)

The year began with the death of one of my favourite artists/writerJohn Berger. I remember we thought 2016 was bad for the death of larger than life artists. John Berger was such a great humanist. But I love that I can still read him and hear his fabulous voice in my head. I did order his last work of essays Confabulations and made a concerted effort to gather all the books I had by him in one place. They are now housed in my studio. Vale John Berger. I return to you all the time.

Thinking of artists, I loved reading the The Surreal Life of Leonora Carrington by Joanna Moorhead.

You might gather by the next titles we have Alzheimer’s in the family - my Dad has had the disease (as far as we know) the last 10 years. Books that have helped me try to understand what is happening for him and helping me deal with it this year have been:

Learning to Speak Alzheimer’s- A Groundbreaking Approach for Everyone Dealing with the Disease by Joanne Koenig Coste.

The Forgetting Alzheimer’s: Portrait of an Epidemic by David Shenk.

Being Mortal by Atul Gawande.

And In Pursuit of Memory- The Fight Against Alzheimers by Joseph Jebelli

I am rereading Missing Out by Adam Phillips with newly minted insights from thinking about memory and who we are without it.

I thoroughly enjoyed Geoff Dwyer’s book on Tarkovsky’s film Stalker called Zona. I need to see Stalker again but as Geoff Dwyer says- it has to be cinematic not at home! The ignition of crazy nuclear war thinking by America’s President Trump, who thinks he’s eviscerating ‘Rocket Man’ with a tweet, sets a dé ja vu tone reading about the haunted nuclear-strange Beckettian terrain of the film Stalker.

I love a good graphic novel and I have thoroughly enjoyed two by Riad Sattouf - THE ARAB OF THE FUTURE A Childhood in the Middle East 1) 178-1984 and 2) 1984-1985. I also enjoyed the short graphic novel by Jason Lutes called Jar of fools. One for the young at heart to the very young is by my friend Trace Balla- who wrote the book RiverTime. This year I read her book Rockhopping, taking me all the way to the source of the Glenelg River in Gariwerd (the Grampians).

Feeding into my marine thinking for projects, I am still working my way through The Sounding of the Whale Science and Cetaceans in the 20th Century by D.Graham Burnett. I am also in the midst of The Reef A Passionate history by Iain McCalman. Hoping that Pelican1 will be on her way North to the Reef next year too. As we have worked on the Cape a lot in the last 15 years, I have also been reading the story of the explorer Edmund Kennedy in a book I found second-hand (Daylesford) called Kennedy of Cape York- Edmund Beale. Trying to get some insight into the newly colonial world and the exploration of the Eastern Cape (before the impact of the gold rush). The book tells the story from a very colonial perspective. Larissa Beherendt’s book FINDING ELIZA Power and Colonial Storytelling was a good follow on read.

I then found myself rereading gularabulu - Stories from the West Kimberley by Paddy Roe edited by Stephen Muecke.

'This is all public,

You know (it) is for everybody:

Children, women, everybody.

See, this is the thing they used to tell us:

Story, and we know.

Paddy Roe

Back to the science books, I learnt a lot from Where The River Flows, Scientific Reflections on Earth’s Waterways by Sean W.Fleming. Had me looking at graphs of sine waves (there was a reason to learn about them in maths after all!), thinking about ‘Digital Rainbows’ and diving deeper into scientific connections between rivers, land and ocean and understanding that the physics of rivers and the quantum leap in understanding being made about their dynamics is one of the many tools that will be needed to help care for this crowded planet.

The Ocean Of Life-The Fate of Man and the Sea by Callum Roberts was another regular dip in as I gather ideas to try to incorporate plans for sea projects and understand our oceans more deeply (haha).

A new writer for me this year was Yi-Fu Tuan with his book ROMANTIC GEOGRAPHY in search of the sublime landscape- A geographer’s meditation on place and human emotions.

I found two new wonderful reference books, the first second hand from South Melbourne Market -The Seabirds of AUSTRALIA by Terence R. Lindsey. And SEAHORSES- A Life-Sized Guide to Every Species by Sara Lourie.

Looking at the politics and economics of our times I managed to read The Secret World of Oil by Ken Silverstein- an enlightening exposé of the behind the scenes snake-oil salesmen. The old rule of following the money results in a thorough investigation of oil’s all too human underbelly. I am still reading Kate Raworth’s book Doughnut Economics. 7 Ways to Think like a 21st Century Economist. A complete creative overhaul of economics, pulling it out of our old ways of understanding the world to make ideas for a better future world possible. Highly recommend.

It’s been another tough year for journalists and the book of writings by Anna Politikovskaya Is Journalism Worth Dying For? reported from Russian frontline and includes the piece that she was working on at the time of her murder.

‘What am I guilty of? I have merely reported what I witnessed, nothing but the truth.’

It was a journalist who wrote a difficult and intense book about the 2011 tsunami in Japan that I’ve just finished. GHOSTS of the TSUNAMI by Richard Lloyd Parry. I have not stopped thinking about that wave and our visit to Japan’s Irate prefecture 3 years post the event left an indelible memory and deep affection for all the people we met still picking up and recovering after the trauma and destruction from that most unsea-like wave.

Back to Oz I loved reading Sophie Cunningham’s book Warning: The Story of Cyclone Tracy. I was very fortunate to take part in one of Sophie’s walks, following the footsteps of William Buckley from Sorrento to Dromana. Though footsore, it was a terrific way to connect with the Bay, while thinking of this man’s path and how different, perhaps, Australia could have been if his attitude to the First People of this Country was shared across the country. I reread much of the fictionalised account again by Craig Robertson (Buckley’s Hope -The Real Story of Australia’s Robinson Crusoe) to get me in the frame of mind for the 20k meditative walk. It was on a recommendation that Sophie shared on Facebook that I now have Phillip Pullman’s latest book The Book of Dust by my bed.

The year has been a terrible one for our ongoing torture of refugees who are STILL languishing in our offshore prisons. I heard that New Zealand had offered to take ALL the men on Manus and that offer has been refused by Dutton and MT. I went to the launch of a book that was trying to navigate the extremely polarised political territory around asylum seekers and I highly recommend it. Bridging Troubled Waters Australia and Asylum Seekers by Tony Ward. During the year I went to a wonderful event organised by Behind the Wire (http://behindthewire.org.au) and came away with their incredible book of first-person narratives called They Cannot Take The Sky- Stories from detention. I reckon our pollies should be sat in a room and this is read aloud to them.

A book that has been a good one to read this year was Hope in the Dark Untold Histories, Wild Possibilities by Rebecca Solnit which I read with the new foreword and afterword.

From the gifts of Christmas I have a pile that includes John Clarke- A pleasure to be here. A very sad loss to the Australian landscape, he will be missed for a very long time. The Man who Climbs by James Aldred and looking forward to A.S. Patrić’s new book Atlantic Black. Also on the pile is Robert Mafarlane’s The Old Ways- A Journey on Foot.

And looking back out to sea with a beautiful book I have just started. The Seabird’s Cry - The Lives and Loves of Puffins, Gannets and Other Ocean Voyagers by Adam Nicolson.

Might have to do a separate post on the poetry that is always by my bedside but all I can say is as I get older, reading poetry becomes more and more pleasurable.

If you have got this far in my rambling through my ambling reading, I want to wish you a very Happy New Year, illuminated by many, many fine reading adventures….

0 notes

Text

Blog August 2017

Unpicking the installation submitted at the end of year show, August 2017

3. Edwardian rowing-deckchair, conclusion and reading list

The third element of the installation, the Edwardian rowing-deckchair is an anomaly. I will be brief about it because I have already treated its objectives in a previous blog. As well as the plaque and the book, the rowing-deckchair offers the possibilities of “passage, displacement, arrivals and departures: change” (Judith Tucker, 2007). And whilst we comfortably lie in our opulence, the deckchair provides a space for reflection on our decline and survival. Whatever the answer, the earth will continue to orbit regardless.

Reading list

Christophe Bonneuil and Jean-Baptiste Fressoz, translated by David Fernbach, The Shock of the Anthropocene, The Earth, History and Us,(Verso, 2017).

Noel Castree, The Anthropocene and Geography (v 2017/27 June).

Dipesh Chakrabarty, The Climate of History: Four Theses, Critical Inquiry 35 (Winter 2009), 197–222

Paul Claval, The Cultural Approach In Geography: Practices And Narratives , Proceedings of the Conference THE CULTURAL TURN IN GEOGRAPHY (2003).

James Hanssen‘s blog

Donna Haraway, Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Plantationocene, Chthulucene: Making Kin , Environmental Humanities 6 (2015), 159–165.

Cymene Howe, Timely, in Theorising the Contemporary, Cultural Anthropology (January 21 2016).

Simon Jarvis, ‘Quality and the non-identical in J.H.Prynne’s “Aristeas, in seven years”’, in Thomas Roebuck and Matthew Sperling, The Glacial Question, Unsolved’: A Specimen Commentary On Lines 1-31 (2010), p42.

Robert Macfarlane, Cultures of the Anthropocene, Course Outline (July 2016).

Timothy Morton’s Hyperobjects, in Stephen Muecke, Global Warming and Other Hyperobjects, Los Angeles Review of Books (February 20, 2014).

International Commission on Stratigraphy, the International Chronostratigraphic Chart (v2017/02).

Sam Solnick, Poetry and the Anthropocene: Ecology, biology and technology in contemporary British and Irish poetry (Routledge Environmental Humanities, 2016)

Judith Tucker, Resort viii, Solo exhibition curated by Daniel Hinchcliffe, Institute of Contemporary Interdisciplinary Arts (20 July-12 October 2007).

Well-being of Future Generations, (Wales) Act 2015, Welsh Government.

0 notes

Note

Could you (if you want) explain that Stephen Muecke quote? What he means by that?

I honestly just found the quote and took a liking to it so this will just be my personal interpretation. To me, the quote speaks of researchers studying away at our cultures and having no real desire to maintain our traditions and practices at the same time. Going by the full quote: "How does one justify the transformation of lived culture into museum culture without this desire for preservation, and this need for researchers to keep working?". Sure, they want to document everything but, going by the quote, I THINK he is talking about researchers being interested in their own personal gain whilst not even thinking about the culture and people they’re researching. I may be totally wrong though.

1 note

·

View note