#Sumerian Cylinder Seals

Video

youtube

Project Looking Glass | The Time Warriors of the 2012 Apocalypse

#youtube#The Why Files#Majestic 12#MJ 12#Project Looking Glass#Illuminati#Sumerian Cylinder Seals#wormholes#stargates#portals#UFO#UFOs#Area 51#Project Aquarius#remote viewing#time travel

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

ignore me i’m crying at the british museum because of cylinder seals

#this is the thing that’s convinced me that i definitely want to do a phd/pursue assyriology#literally only went and looked at the ancient near east section and experienced love at first sight#cylinder seals#ancient Near East#Mesopotamia#akkadian cylinder seals#neo Sumerian cylinder seals#assyriology#archaeology

2 notes

·

View notes

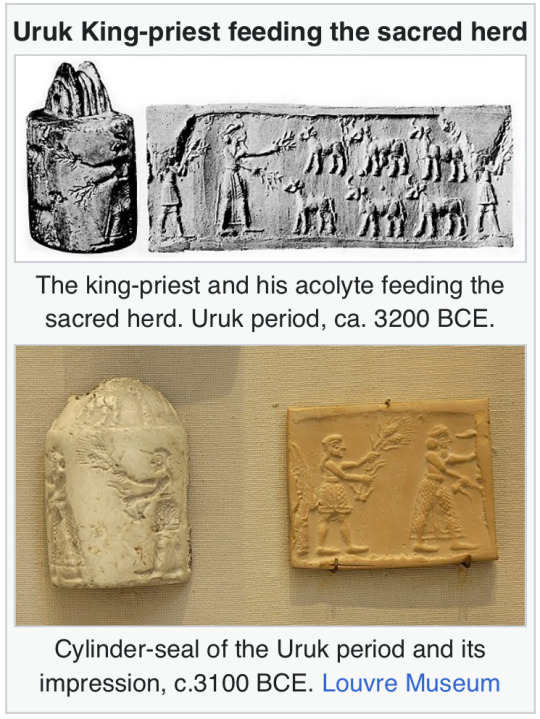

Photo

Seal impression of Baranamtara, queen of Lagash

Excavated at Tello (ancient Girsu), Iraq

Early Dynastic IIIb period, ca. 2400-2350 BCE

Musée du Louvre

#baranamtara#lagash#girsu#tello#mesopotamia#sumerian#early dynastic#cylinder seal#art history#archaeology#louvre

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

as per usual going insane over historical artifacts in order to stay sane about humanity source

#she's wearing a cylinder seal on a bracelet on her wrist!!!!!!#sumerian#ancient sumer#okay when i typed in that tag the suggestion was 'ancient sumeria' u all know that's... that's not what its called right#ancient hyperfixation#antiquity

0 notes

Photo

The Myth of Etana

The Myth of Etana is the story of the Sumerian antediluvian King of Kish who ascends to heaven on an eagle to request the Plant of Birth from the gods so that he might have a son. Etana is named as the first king of Kish in the Sumerian King List (composed c. 2100 BCE) which claims he reigned early in the 3rd millenium BCE. According to the Sumerian King List, Etana was known as "he who stabilized the lands" after the gods had created order out of chaos and established the concepts of kingship and government among humanity. Etana was, therefore, a well-known and highly respected figure and would have been chosen as the central character for precisely this reason. A central message of the myth is that one should trust in the gods and Etana, a great king, would have been chosen by the unknown author as the best exemplar in conveying that message.

Central Message

That the myth is very old is attested to by cylinder seals depicting Etana on the eagle's back which date from the reign of Sargon of Akkad (2334-2279 BCE). The British Museum has among its holdings a fragment of The Myth of Etana from King Assurbanipal's library at Ninevah, dating from the 7th century but, as G.S. Kirk points out:

The Neo-Assyrian version from Ashurbanipal's library happens to be the most surviving text, but where it overlaps with an Old Babylonian version of a thousand years earlier it corresponds with it very closely, sometimes word for word. A short Middle Assyrian fragment maintains the same accuracy. (25)

The story contains many motifs seen in myths of every culture: a great city created by the gods, a search for a worthy ruler, talking animals, broken oaths, divine intervention and a quest which brings the hero to the land of the gods (this one involving an eagle of mythic proportions). The myth may have been intended, as suggested by R. McRoberts, to convey a political message regarding kingship:

When this story is placed in the context of the First Dynasty of Kish, and its exceptional rule of twenty three consecutive kings, it can be seen as more than a tale of fantasy. Earlier dynasties in the King Lists show only a few kings ruling in succession. It is possible that the success of the First Dynasty of Kish could be owed in part to a new tradition of passing the monarchy on to a male heir of the previous king. The myth of Etana served as a colorful reminder that it was the king's duty to go to any lengths, or heights as the case may be, to produce that heir. (40)

While McRoberts' observation is certainly valid, the duty of the king was not only to his people but to the gods who had not only given him life but placed him in his position. According to Sumerian belief (and Mesopotamian belief in general), the gods had created humanity as co-workers to maintain order and keep the forces of chaos in check. The king was responsible to both the gods and his subjects to make sure the gods' will was followed. He could not perform this task if he had no faith in the gods himself and so the myth, in addition to its many other themes, would have emphasized Etana's faith in the gods even when it seems his prayers have not been answered.

Continue reading...

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

Akasha, still mortal. Designing her was challenging given the lack of extant reference, but this is what I came up with:

Apparently she was turned in 4000 bce, so I based my research in the Uruk Period of Mesopotamia (which was named for the Sumerian city of Uruk, now Iraq, where Rice said Akasha is from). In 4000, Kaunakes we’re not yet in style for Sumerians, instead wearing more straight-fitting kilts/net-dresses. I believe those also conformed to the rule of higher status =ankle length, lower class = knee length, so that’s what I did

On the fabric color—I read a paper that posited the ‘net’ of the net dress shown on the cylinder seal linked above/attached below, was actually a dyed pattern. The cylinder seal is dated @ ~3000 bce, BUT there is evidence of ochre-dyed cloth from Çatalhöyük, in Anatolia, from at least 5700 bce, so I think fabric dyeing in a less complicated pattern sounds feasible for 4000 bce.

Given 4000 was also the Chalcolithic Age/Copper Age in Mesopotamia, I wanted to include something copper. While I couldn’t find extant copper jewelry-jewelry, I did find these pins, and iirc Sumerian wrap-clothing was held with pins anyway

Re: necklaces, Akasha’s is based on this one.

I went with Iraqi-Lebanese actress Zahraa Ghandour as (partial) facial reference

Some assorted refs I don’t think are included in the links:

#I say ‘lack of extant reference’ bc everybody and their mother wants to talk abt 2000 bce onward. including me!!#I wanted to draw one a them leaf/feather headdresses:(#my art#iwtv#interview with the vampire#tvc#vampire chronicles#queen of the damned#qotd#akasha#historical dress#as for whether she should have a head covering for cultural reasons/just for the climate. I don’t think so.#I pirated a 200 page paper abt it so. I don’t think it was a thing yet for men or women#I think she should be fatter bc apparently Sumerians were stocky. but the page that said that was wrong abt something already#so I didn’t trust it/haven’t found another source#did make her a historically accurate shorty tho. which I love.#mother of all vampires wreaking terrible havoc. from 5 ft above sea level

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shirdal 'Lion-Eagle'

Talon Abraxas

Ancient origins of the griffin

A legendary creature with the body, tail, and back legs of a lion, the head and wings of an eagle, and, sometimes, an eagle's talons as its front feet first appears in ancient Iranian and Egyptian art dating back to before 3000 BCE. In Egypt, a griffin-like animal can be seen on a cosmetic palette from Hierakonpolis, known as the "Two Dog Palette", dated to 3300–3100 BCE. The divine storm-bird, Anzu, half man and half bird, associated with the chief sky god Enlil was revered by the ancient Sumerians and Akkadians. The Lamassu, a similar hybrid deity depicted with the body of a bull or lion, eagle's wings, and a human head, was a common guardian figure in Assyrian palaces.

In Iranian mythology, the griffin is called Shirdal, which means "Lion-Eagle." Shirdals appeared on cylinder seals from Susa as early as 3000 BCE. Shirdals also are common motifs in the art of Luristan, the North and North West region of Iran in the Iron Age, and Achaemenid art. The 15th century BCE frescoes in the Throne Room of the Bronze Age Palace of Knossos are among the earliest depictions of the mythical creatures in ancient Greek art. In Central Asia, the griffin image was later included in Scythian "animal style" artifacts of the 6th–4th centuries BCE.

In his Histories, Herodotus relates travelers' reports of a land in the northeast where griffins guard gold and where the North Wind issues from a mountain cave. Scholars have speculated that this location may be referring to the Dzungarian Gate, a mountain pass between China and Central Asia. Some modern scholars including Adrienne Mayor have theorized that the legend of the griffin was derived from numerous fossilized remains of Protoceratops found in conjunction with gold mining in the mountains of Scythia, present day eastern Kazakhstan. Recent linguistic and archaeological studies confirm that Greek and Roman trade with Saka-Scythian nomads flourished in that region from the 7th century BCE, when the semi-legendary Greek poet Aristeas wrote of his travels in the far north, to about 300 CE when Aelian reported details about the griffin - exactly the period during which griffins were most prominently featured in Greco-Roman art and literature. Mayor argues that over-repeated retelling and drawing or recopying its bony neck frill (which is rather fragile and may have been frequently broken or entirely weathered away) may have been thought to be large mammal-type external ears, and its beak treated as evidence of a part-bird nature that lead to bird-type wings being added. Others argue fragments of the neck frill may have been mistook for remnants of wings.

Lucius Flavius Philostratus (170 – 247/250 CE), a Greek sophist who lived during the reign of the Roman emperor Philip the Arab, in his "Life of Apollonius of Tyana" also writes about griffins that quarried gold because of the strength of their beak. He describes them as having the strength to overcome lions, elephants, and even dragons, although he notes they had no great power of flying long distances because their wings were not attached the same way as birds. He also described their feet webbed with red membranes. Philostratus says the creatures were found in India and venerated there as sacred to the sun. He observed that griffins were often drawn by Indian artists as yoked four abreast to represent the sun.

24 notes

·

View notes

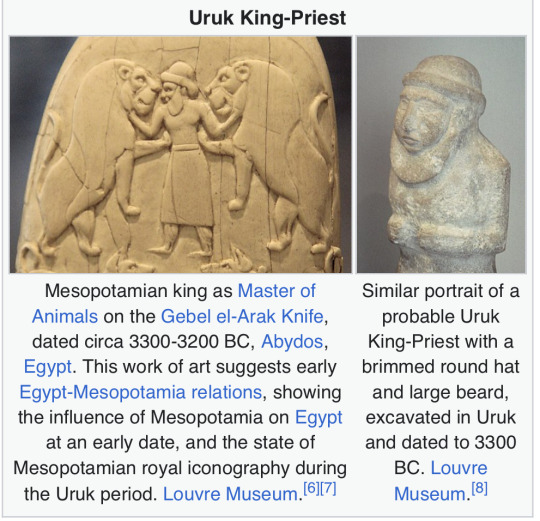

Photo

A Large Collection of Near Eastern Cylinder Seals, and other Near Eastern objects

Circa 4000-500 B.C.

including Jemdet Nasr, Uruk, Sumerian, Neo-Babylonian, Akkadian, Assyrian and Mitannian, engraved in lapis lazuli, serpentine, hematite, marble, and other stones, comprising a wide variety of subjects, as well as several Bactrian bronze stamp seals.

#Near Eastern Cylinder Seals Circa 4000-500 B.C.#ancient seals#ancient artifacts#archeology#archeolgst#history#history news#anicent history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations

586 notes

·

View notes

Text

I really hope my history professor from undergrad is still alive. Idk if he remembers me, but I remember him. He said I was the only student in all his years of teaching to say "I want to learn Akkadian." But that's not quite accurate: what I said was, "hey, I've been working through this book (it was Caplice) over winter break every day and I'm on chapter 8 and I think I'm doing ok, but I have some questions. Can you help me out?" And he was very impressed, I think. He answered all my questions; told me I got all the translations as correct as you can get them. He called me Lugal Edward, Sumerian for "king." He gave me printouts of all of Hammurabi's laws. He lent me his sign list that had every historical version of every single cuneiform sign ever. It was in French, but that didn't matter; I knew exactly what to do with a sign list. That summer I would skateboard to the library with my books and spend a few hours translating Hammurabi's laws. I developed my own cuneiform shorthand that only I know bc I wasn't about to literally draw out every santakku every single time. I went on a field trip to Yale with a few people from the class and we used real cylinder seals. I got to use a stylus much nicer than the one I made at home from chopsticks to write with. He pointed out to me on their replica Hammurabi the signs I knew and I could read it. On my 24th birthday, (he didn't know it was my birthday until I admitted it late in the day) he took me to a lecture at Yale by Stephanie Dalley who authored my favorite collection of translations of Mesopotamian myths. I got to meet her and meet all the guys I'd read all the books by (it's not a huge field so you do get to know who's who pretty quickly.) And he bragged about me to all of them. It was the best birthday ever. After Hammurabi, I worked my way up to translating historical texts and some of my favorite myths on my own. In grad school I finally got my hands on Enuma Elish. I didn't have as much time as I would have wanted to sit and translate it, what with my actual coursework, but I did go over my favorite parts. It was the myth that made me want to learn the language in the first place. I hope to god that he's alive and that I can reach out to him still - because forget all of that, literally: I had a bad life before I went to that school and I've made nothing of myself since I left grad school. But he made me feel like I was really worth something, and I want more than anything to thank him for that

#people think the grades I used to get or the shit I do just happens by magic#but it doesn't. it's hours upon hours upon hours of hard work#and I didn't even stand out much in grad school to say truth. we were all overachievers at that point#I won't do it today because it's 4 am and I'm on no sleep#but if I can I will do it this weekend. I hope to god he remembers me#when I tutored history I did everything the way I thought he would have done it. I passed his lessons on to my own students

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Submitted via Google Form:

What is the earliest point in evolution could humans evolve written language? Let's say biologically, human evolution was similar to reality, could say Neanderthals have written language already? Like before civilisations began? Also, written language is certainly not only for the elite. In fact, it got started in various families and then got spread among the tribes. So we have thousands of different tribes and familes across the world - each with their own languages and writing systems. Of course, there are some similarities as people have travelled a bit and met neighbouring tribes. So basically before society was properly formed into civilisations, there should already be writing but civilisation is actually what prodded society to centralise communications and languages. Does this work? Basically, I just want a society that had writing from much earlier on than reality and figuring out how it could have been done.

Tex: Writing is developed, much like any other tool, as a function of necessity. If it’s not necessary for a society to develop it, then writing won’t exist for them. Civilisation is also, as a concept, prone to periodic re-defining as we accumulate more data and our perceptions of the data shift (for example, one could define the pinnacle of civilisation as taxes, where before another defined it as religion).

Writing also has exceptionally little to do with biology as writing is a social construct meant to fill a void found in one’s culture. Consequentially, writing can also encompass a broad range of intentional markings that demonstrate specific meanings, from tally marks, to standardized pictures, to ideograms, to glyphs.

What does your world need writing for? What niche does it fill? What were the people using as its predecessor, and what happened to cause them to change systems? Did the scope of their needs change, or did the perception of their needs change? What information is important for them to record, on a societal and personal level? Who teaches writing? Who learns it? What is the method of transmission, and for those that teach writing, is it their sole occupation or something on the side?

Utuabzu: Writing is old. Really old. At least 5000 years old. This seems a long time, but humans have been living in permanent settlements and practicing forms of agriculture in West Asia for about 9000 years. Homo sapiens has been around for at least 300,000 years. But only in the last few thousand years, in a handful of places, did humans independently come up with the idea that the spoken word could be preserved using symbols that others could be trained to decipher.

The earliest writing as far as we can tell is cuneiform, from Sumeria in what is now southern Iraq. It may or may not have had some influence on the development of Egyptian hieroglyphs from pictographs to an actual script - we have found Sumerian cylinder seals in very early Egyptian sites, indicating that the two groups were in contact. But from these two points the idea of writing spread through the Mediterranean and West Asia. The Indus Valley civilisation also used a script, but we are unable to decipher it and have relatively few examples to work from, so we cannot tell if it even is a true script or if it predates contact with Sumeria.*

Shang Dynasty China also developed the earliest form of Chinese script from the Oracle Bone tradition not long after this. This also spread, together with Chinese ideas, agricultural and governmental practices across much of eastern Asia.

Meanwhile cuneiform script was adopted by a wide range of cultures in West Asia, and inspired other scripts like Elamite, Old Persian and Ugaritic, which while using similar shapes were structured very differently. Egyptian hieroglyphs inspired Anatolian hieroglyphs and were later in the early Iron Age the basis that the Phoenician alphabet** - ancestor of alphabetic, abjad and abugida scripts from the Philippines to Iceland - was derived from.

Another place we see writing develop entirely independently is in Central America, where a pictographic system was employed from the Olmec period all the way through to the 16th Century, but only became a true script in the Mayan region [at time, need to check when]. The system employed elsewhere in Mesoamerica did not have the capacity to accurately render speech, so far as we are aware.***

There are also a handful of other instances that might or might not be examples of true scripts developing entirely independently, from rorotongo on Rapanui to the quipus of the Andes to [pretty sure there's one in central africa, but can't remember the name just now]. We simply don't have enough information to be certain about any of them. Oftentimes, because the media they were written on does not survive all that well, or was deliberately destroyed.

But something you should bear in mind is that complex societies don't necessarily require writing for a lot of their history. Many of the most impressive cultures of the ancient world were not widely or at all literate. There's no indication that the Mississippian culture that built sites like Cahokia had writing, nor did Teotihuacán or the various cultures of the Andes. There's no evidence of writing at Great Zimbabwe, nor at Jomon sites in Japan.

Even in cultures that did have writing, it was frequently not a widely known skill. Your average ancient Egyptian couldn't read hieroglyphs, and Chinese hanzi still take years to master. This is part of why so many traditional scripts were displaced in the 19th and early 20th century. Most people couldn't read them and when authorities decided to use Roman or Cyrillic or something else in mass education, it very quickly became much more widely understood than the traditional script.

To my knowledge, there's no examples of a pre-agricultural society developing writing independently. Some have derived scripts from those they came into contact with, or made entirely unique ones inspired by writing they knew of. But so far as I am aware, none have ever created a script entirely from scratch with no prior exposure to the concept of writing.

*the Sumerians appear to have called the Indus Valley Civilisation 'Meluhha', and were actively trading with it from at least the Bronze Age. Ur III records even tell of a colony of Meluhha merchants at Guabba, near Lagaš, and Sumerian cylinder seals have been found in Indus Valley sites.

**actually an abjad.

*** the conquistadors burned almost all pre Columbian codices, so we can't ever be 100% certain that no other variants of the system developed into true scripts. But it's unlikely.

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some people have asked me why I believe the Ark of the Covenant is an electrostatic device, and I would encourage them to look into the work of Maurice Denis-Papin, who was a descendant of the famous inventor, and who determined that the Ark was capable of holding 500-700 volts per vertical meter when contained in a dry space, dischargeable to the earth by means of it's garlands- and this is even before it has a superconductive substance in it like monoatomic atoms (manna), and before it is placed in something like the Great Pyramid, which has its own electrostatic potential. I would also point out Bruce Rux's research in his book Architect of the Underworld, where he mentions:

"The story of the flood is the conclusion of one of those mythical, epic conflicts. There were others. Sitchen pieces together the story of two civil wars in his work, "The Pyramid Wars", taken largely from the Sumerian "Myths of Kur" tablets, the Lugal-e epic, F.Hrozny's "Mythen von dem Gotte Ninib", J.Bollenrucher's "Gebete und Hymnen an Nergal", and George A. Barton's "Miscellaneous Babylonian Texts", as well as fragmentary tablets from the region. These texts constitue strong evidence for the two Great Pyramids at Giza having been in existence long before Egyptology claims they were. A cylinder seal shows the symbol of Ninurta (Horus) with a victory wreath, between two objects which could only be pyramids- not only are they triangles, bit they are composed of tiers of rectangular blocks. Reference to one of these is given as "the mountains the gods assembled". Inside it were lethal "stones" , with which "the Great Serpent" nearly killed Ninurta in his battle against (the serpent), with their "strong power". ..to "grab and kill, with a tracking which seizes". The "stones" glowed in the dark in different colors, set in various recesses which may be found in the Great Pyramid....one of the weapons was a net, the device of which was located in a secret chamber in the Pyramid." It should also be pointed out that the ancient name of the Sphynx is ARQ UR, possibly related to where the name "Ark" itself came from...

Now even if such an Ark wasn't placed in the Great Pyramid, but instead was placed in a tabernacle in the dessert with WOOL curtains, which, of course, pick up static on their own, then what do you think the Ark would do inside that location? It would just absorb more static electricity of course, until it began to discharge out of the top- as the "presence of God!" Our Order has found six arks, and we know where there is another four, and it is possible that there were hundreds in the ancient world before they got melted down for the previous metals... This reasonably suggests that they were being used for that electrostatic potential in different ways. They are depicted all over the Egyptian temple walls...yet people only think of the Torah or Old Testament when discussing it...

4 notes

·

View notes

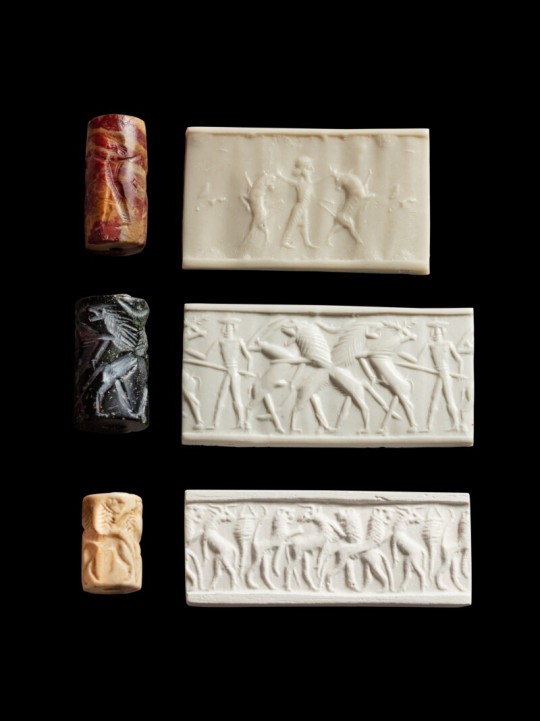

Photo

Cylinder seal with goddesses Ninishkun, the subject of three hymns attributed to Enheduanna, and Ishtar, Mesopotamia, Akkadian, Akkadian period (ca. 2334–2154 BCE),

Cuneiform inscription: “To the deity Niniškun, Ilaknuid, [seal]-cutter, presented (this), Limestone”

This cylinder seal was dedicated to a little-known goddess, Ninishkun, who is shown interceding on the owner's behalf with the great goddess Ishtar. Ishtar places her right foot upon a roaring lion, which she restrains with a leash. The scimitar in her left hand and the weapons sprouting from her winged shoulders indicate her war-like nature.

Poet Enheduanna (ca. 2300 BCE), the earliest-named author in world literature. Bringing together a spectacular collection of her texts alongside other works made circa 3400–2000 BCE.

Enheduanna received her name, which means “high priestess, ornament of heaven” in Sumerian, upon her appointment to the temple of the moon god in Ur, a city in southern Mesopotamia, in present-day Iraq.

The daughter of the Akkadian king Sargon, Enheduanna left an indelible mark on the world of literature by composing extraordinary works in Sumerian. Her poetry reflected her devotion to the goddess of sexual love and warfare — Inanna in Sumerian, Ishtar in Akkadian.

Whereas much of ancient Mesopotamian literature is unattributed, Enheduanna introduced herself by name and included autobiographical details in several poems. Her passionate voice had a lasting impact in Mesopotamia, as her writings continued to be copied in scribal schools for centuries after she died.

The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, acquired 1947; A27903.

Text courtesy: Hyperallergic

#art#design#tablet#enheduanna#priestess#sumeria#mesopotamia#iraq#royal#poetry#king sargon#history#style#inanna#ishstar#akkadian#cylinder#ninishkun

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

We can only guess at what an average smith in Ur or a shepherd in Akkad felt about the Old Akkadian Empire’s rise and fall. Even for the elites, their lives are most often captured only by brief snapshots, such as the cylinder seals that attest to their existence and little else. That is part of the intrigue that clings to Enheduana’s poems. ‘The Exaltation’ seems to offer a personal account of the political drama of the Old Akkadian period, told by the daughter of the emperor herself. Enheduana was not so much an eyewitness to the insurrection as the eye of its storm.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Day 14: Aya

The “Lady of the Dawn” an archetypical divine bride. In Mesopotamia proper she was regarded as married to Shamash/Utu the sun god. Her Sumerian name was Sherida. She was also adopted into and had popularity in the Hurrian pantheon, where she was known under the name Nin-Aya and was married to the Hurrians sun god Simige.

In her depictions on cylinder seals she usually has a tiered dress, but I’ve drawn those a lot already so I decided to draw her in Hurrian garb. Aside from the garments in the seals she sometimes has a breast exposed, which I assumed is too risqué for tumbr so it’s getting censored 😅

#Aya#annunaki#inktober2022#mesopotamian mythology#mythtober2022#lots more to be learned about her#last year when I drew shamash I was unaware of her existence for some reason

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ancient Sumerian cylinder seal impression showing the god Dumuzid being tortured in the Underworld by galla demons

3 notes

·

View notes

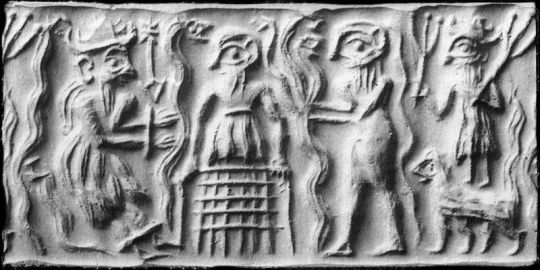

Photo

Cylinder Seal

Cylinder Seals were impression stamps used by the people of ancient Mesopotamia. Known as kishib in Sumerian and kunukku in Akkadian, the seals were used by everyone, from royals to slaves, as a means of authenticating identity in correspondence. In time, they came to be recognized as one's personal identification.

They originated in the Late Neolithic Period c. 7600-6000 BCE in the region known today as Syria (though, according to other claims, they originated later in Sumeria, modern Iraq) and were made from semiprecious stone (marble, obsidian, amethyst, lapis lazuli, to name only some) or metal (gold or silver). These seals were worn by their owners on strings of leather or other material around the neck or wrist or pinned to a garment.

The purpose of seals was to serve as a personal signature on a document or package to guarantee authenticity or legitimize a business deal; in the same way one signs a letter or form today or writes one's return address on an envelope or package to be mailed. The seal was rolled onto the moist clay of the document as an offical, binding, signature. Cylinder seals were also used in Egypt and developed completely independently in Mesoamerica as evidenced by archaeological finds of Olmec cylinder seals dating to c. 650 BCE. The Mesopotamian cylinder seal is the best known, however, and was the most widely used.

Cylinder Seals & Stamp Seals

Contemporaneous with cylinder seals were stamp seals which were smaller and less ornate in design. The typical cylinder seal was between 3-4 inches (7-10 cm) long while stamp seals were less than an inch (2 cm) in total and more closely resembled the later signet ring. It would make sense that the stamp seals preceded the cylinder seals as the former are more rudimentary but evidence suggests the seals were in use at the same time with one type favored more than the other in different regions. Scholar Clemens Reichel (whose essay is included in Englehardt's work, Agency in Ancient Writing) suggests the reason for this was simply a matter of necessity.

Those areas which favored the stamp seal (the regions of modern-day Syria and Turkey) had no need for the elaborate design imprint of the cylinder seal while the regions to the south, which had a more highly developed bureaucracy, required more detailed information in a seal.

The city of Uruk, for example, had a highly complex bureaucracy of different agencies which required detailed information on who was signing what document and, further, which office it originated from. The simpler and smaller stamp seals could not provide the space on which to carve such information while the longer cylinder seals fit the need perfectly.

The longer cylinder seals would have provided the name of the agency and name and title of the individual within that agency who was signing the document. In order to accurately represent and identify the owner of such a seal, a skilled artist was required who carved the story of the individual on the stone cylinder in exacting detail.

Continue reading...

47 notes

·

View notes