#Tetzaveh

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Parashat Tətzaveh: הַשֵּׁשׁ | hasheish

I am always thinking — worrying, even — about where stuff comes from. To get plain, undyed cloth with no particular embroidered ornamentation, you need all this vast apparatus of production, all these hours and hours of labor and years of learned skill. (There are few things as humbling as trying to spin thread even and fine enough to be woven into clothing using nothing more than a drop spindle and your own two hands.) I often read visions of idyllic, utopian futures where stuff just seems to pop magically into existence, as tho generated by a Star Trek replicator. No one has to harvest the fruit; no one has to lay sewage pipes; no one has to stitch together the pillowcases. But all of these things take work, and if you put that work out of mind, it’s all too easy to put the people who do that work out of mind as well. But without people doing that work, the work does not get done, and if the work does not get done, none of these things can exist.

In many of these divrei, I’ve explored words that are difficult to translate, either because they’re ambiguous in the Hebrew or because I want to freight them with mystical meaning. Not so this week; שֵׁשׁ | sheish tidily means “linen”.

Even so, there’s something curious about its presence in this week’s parashah. G-d commands Mosheh to make the holy garments of the high priest, the garments that are to be worn when ministering in and around G-d’s holy desert tent, and in Shəmot 28:5, we learn that these garments are to be made of אֶת־הַזָּהָב וְאֶת־הַתְּכֵֽלֶת וְאֶת־הָאַרְגָּמָן וְאֶת־תּוֹלַֽעַת הַשָּׁנִי וְאֶת־הַשֵּׁשׁ | et hazahav və’et hatəkhéilet və’et ha’argaman və’et tolá’at hashani və’et hasheish | “gold and blue and purple and worm-crimson and linen”. The Torah doesn’t specify what fibers are supposed to be dyed blue and purple and red, but rabbinic tradition is firm that those fibers were to be wool. Which is to say that the high priest’s holy clothes would have been made from a mixture of wool and linen, a mixture that is elsewhere explicitly prohibited by G-d.

There’s a lot one could say about this. I’ve written elsewhere about the idea of G-d as an all-containing Unity; perhaps drawing close to G-d requires relaxing divisions that are present elsewhere, edging towards a state of being where any one thing is every other thing at once. One could bring in the mystical narrative of tzimtzum — the idea that to make room for creation, G-d first had to shrink the Divine Presence and withdraw from the world — and Biblical notions of Holiness as dangerous (see, eg, Nadav and Avihu) to suggest that the commanded separation between wool and linen is a fence, a barricade, a staking out of room for material things to exist. (The first primordial acts of Creation were acts of division, separating light from darkness, upper waters from lower; there is a sense in which division is somehow necessary for creation, a sense in which there cannot meaningfully be an I unless there is also a not-I that I am distinguishable from.) But the high priest, in interposing between G-d and the Israelites, has to let down this fence at least a little bit, to relinquish, partly, Earthly existence in order to be able to commune with the numinous.

This is all very rich ground, and someday I may come back to it, but for once, I want to set the mysticism aside and talk materiality.

In descriptions of the priest’s clothing, linen often gets short shrift. People have a lot to say about the metal threads, about the brilliant and fussy dyes, but the linen, when it’s mentioned at all, tends to be glossed as “plain” or “simple”. If you look up pictures of the holy outfit, you’ll find a lot of attention paid to spectacular, eye-catching patterns and big bold washes of intense hues; you won’t find a lot of attention paid to the undyed flax fibers that are also there.

Here is what it takes to turn linen from a plant into a thread.

After the flax has grown — and note that agriculture, especially pre-industrial agriculture, is famously hard labor, so this is already eliding out a frightful amount of work — it must be pulled out of the earth — pulled and not cut with a scythe because you want to get some of the root system too to maximize the length of the available fibers. You must then partially dry the stalks to prepare them for retting. Retting is the process of letting the flax stalks sit in stagnant water so the pith swells and bursts, making room for bacteria to eat away the pectin that binds the bast fibers (the fibers that will ultimately be spun into linen thread) to the other parts of the plant. If you have big pools of standing water (which you must monitor, because if you let the retting process go too far, the bast fibers themselves will begin to decay), this process may only take a few weeks; if you’re in a drier climate (and the wildernesses of the Torah are not known for being particularly wet), you may have to rely on morning dew for the moisture in this process, which will take considerably longer.

Once the retting has gone far enough, you must then break up the stalks completely so the fibers can be extracted. The extraction itself is done by scutching the bundles of flax — striking them repeatedly with a wooden knife to essentially scrape away the woodier parts of the plant. You must then hackle the flax, combing it with a bed of nails to separate out any short or broken fibers, leaving only the long and sturdy bast. A really skilled team might get fifteen or so pounds of usable fibers from fifty pounds of grown flax; with less-skilled teams, you should expect to lose more along the way.

You are now ready to begin to spin. There are fewer conceptual steps to spinning — you take the fibers and spin them into thread — but what steps there are take a great deal of time: Before the invention of the spinning wheel (approximately fifteen centuries after the date of this text), spinning ate up somewhere north of 80\% of the total production time of a garment, including the time necessary to process the flax stalks beforehand and to weave, cut, and sew the garment behindhand. All that retting and scutching and hackling is just a drop in the bucket next to the endless painstaking labor of twisting fiber against fiber from the distaff to the spindle.

And then, of course, you do need to weave and cut and sew those fibers into fabric and into garments.

This is, to put it mildly, an awful lot of work. And this is what is described as plain linen, as simple linen. This is the boring unremarkable stuff.

I am always thinking — worrying, even — about where stuff comes from. To get plain, undyed cloth with no particular embroidered ornamentation, you need all this vast apparatus of production, all these hours and hours of labor and years of learned skill. (There are few things as humbling as trying to spin thread even and fine enough to be woven into clothing using nothing more than a drop spindle and your own two hands.) I often read visions of idyllic, utopian futures where stuff just seems to pop magically into existence, as tho generated by a Star Trek replicator. No one has to harvest the fruit; no one has to lay sewage pipes; no one has to stitch together the pillowcases. But all of these things take work, and if you put that work out of mind, it’s all too easy to put the people who do that work out of mind as well. But without people doing that work, the work does not get done, and if the work does not get done, none of these things can exist.

We look at the high priest, and are dazzled by the finery. Shəmot’s lavish descriptions beguile us with their sensual details. A panoply of colors swirls up from the text — and then plain, simple linen caps the list off, reminding us how staggeringly much human effort goes into making even the most unadorned things.

[This has been an installment of one-word Torah. You can read the whole series here.]

#one-word Torah#Torah commentary#Parashat Tətzaveh#tetzaveh#parashat hashavu'a#parsha#flax#textile production#A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry has a great series on fiber production in the ancient world#which this cribs from a little bit#attn#briochebread#this one is for you

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

tonight in torah study: we learn about the transitive properties of holiness, sacrifices begin, and we try to solve a piece of clothing

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

SILENT TESTIMONY

This week’s parsha, Tetzaveh, is the only one in the Torah after the birth of Moses that does not mention his name. The Baal HaTurim attributes this to Moses’ plea to God on behalf of the Jewish people after the sin of the golden calf: “Now, if You will forgive their sin [well and good]; But if not, erase me now from Your book, which You have written.” The words of a tzaddik (saintly and wise individual) have power, and when Moses told God to erase him from the Torah, God did so by erasing Moses from Parsha Tetzaveh.

This seems like a punishment, which is odd because when Moses made that plea to God, it was coming from a place of great humility. Moses was willing to sacrifice himself to bring God’s mercy upon the Jewish people. In fact, his tactic worked and the people were saved. So why is Moses being punished?

Rabbi Yissocher Frand explains that the omission of Moses' name from Parsha Tetzaveh is not a punishment but rather a tribute to the most humble man who ever lived. Since every other parsha contains Moses’ name, the absence of it in Tetzaveh is felt. Rabbi Frand characterizes it as a “silent testimony” to Moses. But why is Tetzaveh the parsha where Moses’ name is absent? Rabbi Frand again invokes Moses’ humility. The parsha is about the Kohen Gadol (High Priest) and his clothing. Moses’ brother Aaron was the Kohen Gadol, and Moshe didn’t want to steal the limelight from his older brother.

Image: “Moses with the Ten Commandments” by Rembrandt, 1659 (detail)

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Weekly Thought - Tetzaveh

Rabbi Benji

5 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

We are a time capsule of the D.N.A that preceded us. A poem for Parsha Tetzaveh by Rick Lupert. #torah #poetry #tetzaveh

Read along at https://jewishpoetry.net/ephod-for-thought-tetzaveh-aliyah-2/

0 notes

Text

Tetzaveh

I’m thinking about the burden of being a representative this week. Much of this Parsha is describing vestments of the priesthood. The fontlet and breastplates carved with distinction. Every aspect of the outfit laced with symbolism or the names of the sons of Israel so that Aharon can represent the community before Hashem. The burden of representing the people must fall so heavy, claiming that responsibility for saying, “this is who we are.” And it leads me to thinking about how members of minoritized communities are forced to do that every day. You’re not just a person – you are the representation of trans people. Your errors do not simply reflect on your but can confirm stereotypes, and further other people may judge you for the actions of your fellows and not your own. It feels especially ominous that this comes just before the golden calf. We do not see the mistakes of the Israelites yet, but they are coming, and we know how this story ends.

It's collectivism: Kol yisrael arevim zeh bazeh. How do we take responsibility for each other when we disagree? Or when we don’t want to claim association with another’s beliefs or actions? How can we be representatives for each other? What are the limits of being a community? How can we build coalitions when we know we don’t agree on everything, but are still working towards a common cause? What if we don’t agree with those elected to represent us? I think I've been left with more questions than answers but I think that's also life.

1 note

·

View note

Text

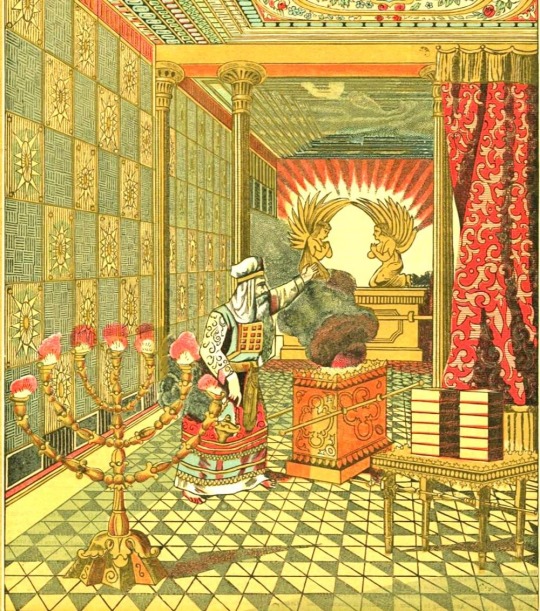

Parashat Tetzaveh (Ex.27:20-30:10) details the regal robe worn by Aaron, the first High Priest (Kohen Gadol).

The Hoshen Mishpat or Breastplate of Judgement was placed over his heart because he was found fit to minister to the needs of the nation.

Aaron humbly pursued peace and justice, fully understanding that the Will of God was all that mattered.

The garments of the High Priest evoked honor, nobility, beauty and the potential for bringing holiness to the physical realm.

The parsha also describes the altar of incense filling the sanctuary of the Tabernacle with clouds of qetoret (incense) a constant reminder of the clouds that surrounded Moses when he spoke with the Creator on Mt. Sinai.

Shabbat Shalom

#secular-jew#israel#jewish#judaism#israeli#jerusalem#diaspora#secular jew#secularjew#islam#parashat tetzaveh#Aaron#kohen Gadol#high priest

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

I went to an Orthodox school and it was a thing to memorize every single parasha. It's one of those things that never leaves you

Question to English-speaking diaspora Jews: How do you typically refer to books of the Tanach? Is it by their Hebrew name (e.g. Bereshit) or by their English-given name (e.g. Genesis)?

#bereishit noach lech-lecha vayera chayei sarah toldot vayeitzi vayishlach vayeshev miketz vayigash vayichi#shemot va'era bo beshalach yitro mishpatim teruma tetzaveh ki-tisa vayakhel pekudei#vayikra tzav shemini tazria metzora acharei-mot kedoshem emor behar-bechukotai#bamidbar nasso behalot'cha shlach korach chukat balak pinchus matot-ma'asei#devarim ve'etchanan ekev re'eh shoftim ki-tetzei ki-tavo netzavim vayelech ha'azinu vezot-habracha#can i have a lollipop now

157 notes

·

View notes

Note

sorry f its obvious, goy here, could you go into what all the colors represent? :D

The twelve stripes on the queer Jewish pride flag represent the 12 stones of the 12 Tribes of Israel on the High Priest's Choshen (breastplate):

Onyx: Levi

Garnet: Yehudah (Judah)

Ruby: Reuven (Reuben)

Peridot: Asher

Malachite: Yosef (Joseph)

Emerald: Dan

Prase: Shimon (Simeon)

Torquise: Naftali

Sapphire: Yissachar (Issachar)

Jasper: Binyamin (Benjamin)

Pearl: Zevulun (Zebulun)

Crystal: Gad

There's no consensus as to which stones exactly were on the breastplate, so I synthesized different interpretations.

Sources used were:

The High Priest’s Breastplate (Choshen)

The Stones, Symbols, and Flags of the Twelve Tribes of Israel

Exodus Tetzaveh 28:17-20 JPS translation

Onkelos Tetzaveh 28-17-20 Metsudah translation

Translating Gemstones

I colour-picked from each stone and ordered them to resemble a rainbow, representing the unity and diversity of the Jewish people and the inclusion of LGBTQ Jews in our history.

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The Leviathan." From the Book of Jeremiah, 11: 14.

God concludes his warnings about half-wits who pray but cannot attain to the unity of the human race, especially within the Holy City. Mankind's failures to address a few grand things render the rest into fodder. The end of wars, bullets, guns, climate change, poverty, and corruption, and that bullshit in and about Israel are among these:

14 "Jeremiah, don't pray to me or plead with me on behalf of these people. When they are in trouble and call to me for help, I will not listen to them.”

The Number is 7792, עזץב, azatzav, "say I'm sorry."

Saying sorry in the Torah is an extensive process.

From Tetzaveh:

10 “Bring the bull to the front of the tent of meeting, and Aaron and his sons shall lay their hands on its head. 11 Slaughter it in the Lord’s presence at the entrance to the tent of meeting.

12 Take some of the bull’s blood and put it on the horns of the altar with your finger, and pour out the rest of it at the base of the altar.

13 Then take all the fat on the internal organs, the long lobe of the liver, and both kidneys with the fat on them, and burn them on the altar.

14 But burn the bull’s flesh and its hide and its intestines outside the camp. It is a sin offering.[e]

Bulls are bullies, persons who see with their "horns" rather than their eyes how their conduct impacts others. God told Moses how to deal with a bull. The Values in Gematria are:

v. 10-11: Bring a bull to the front. The Number is 6111, סאיא , sai, sabaya, "sabaya" (סבבה) essentially meaning "great, okay, cool."

v. 12: Take some of the bull's blood. The Number is 6189, סאףט , safet, the word "safet" (בטח, batah) means "as a verb, and as a noun, it means "safety or security". It is a word that means to trust, feel safe, or be confident"expresses enthusiasm, positivity, and approval,

v. 13: Then take all of the fat and internal organs. The Number is 5734, ןזגד, zgd, "zagad" =discard that which is impure and forbidden, keep what is allowed.

v. 14: Burn the bulls hide and intestines outside. The Number 3421, לדךא, to dhaka, "to the contrary."

The Torah addresses the urge to sin as a result of negative peer pressure and bad influences. To repent, a Kohen priest must help the sinner separate what is self-affirming and what is damning about the inner mechanisms of perception within a pilgrim and refer to the aspects of the Torah that correct one's vision. Finally one must keep the Kashrut on the outside. All social interactions must conform to the Kashrut.

The rules of Kashrut cannot be taken literally. One will miss a significant body of knowledge within the Torah if one does interpret the Kashrut using Kabbalah.

Watch:

Can I eat an intestine? = 598, ךץח, "brush up, polish until you shine." = You can do better than this one.

Can I eat the brisket? =456, תןו, tannev, "tannev" (תנין) refers to a mythological aquatic serpentine creature, often associated with Leviathan and Rahab, and can also symbolize nations and their systems of belief, depicted as aquatic and serpentine.

=Eat as much as you can and still swim.

All of the axioms listed by the Kashrut have a sensible counterpart in English. "Do not eat a pig"= "You feed it." The trick then is to figure out how to get the pig to feed you.

The separation of Judah and Jerusalem "unclean and clean" found in the Tanakh is a good example. One place was lazy, egoistic, combative, the other tried to hold the Jewish people together as God required. One was a bull, the other was an ox. God will not listen to a sorry bull that does not listen to him and neither should we. In any case, it is best not to have to say you are sorry by refraining from all sin to begin with. Following the Kashrut positively can help.

0 notes

Text

youtube

5 Minute Torah: Tetzaveh | The Invisible Leader Have you ever felt invisible? Have you ever been part of a team that accomplished something really great, but for whatever reason, you weren’t given any recognition? That can be a painful experience. But sometimes we need to follow the example of Moses and Yeshua and give up ourselves for the greater good. If you’re not sure what I’m saying, we have a great example we can explore in this week’s 5 Minute Torah. 📘 Pick up a copy of one of Darren's books: Cup of Redemption Passover Haggadah: https://amzn.to/4iuokpc Eight Lights Hanukkah Devotional: https://amzn.to/3yPZqfy --on Barnes&Noble: https://ift.tt/9yYOdo4 5 Minute Torah, Volume 1: https://amzn.to/3VzepUR 5 Minute Torah, Volume 2: https://amzn.to/3s560uM 5 Minute Torah, Volume 3: https://amzn.to/3s6SYx4 Four Responsibilities of a Disciple: https://amzn.to/3S9FZ8q Four Responsibilities of a Disciple (Spanish): https://amzn.to/3gUIqyB Tefillot Tamid Siddur: https://amzn.to/3s5R5Au ❤️ Ways to Support Shalom Macon: Tithe.ly | https://ift.tt/fBeoayO PayPal | [email protected] Text "GIVE" to (706) 739-5990 Chapters: 00:00 - Food for Thought 00:44 - 3 Things You Need to Know About the Torah Portion 05:42 - Messianic Commentary on the Torah Portion ✅ Important Links to Follow ✨ Discover Jesus in His true Jewish context with The Jewish Jesus series here: https://ift.tt/xyq9K5f ✨ Explore the Repaving the Romans Road series for the deeper Jewish context of salvation here: https://ift.tt/4vQm26V ✨ Get into the 5-Minute Torah series for quick, powerful insights into the weekly Torah portion here: https://ift.tt/NPLcbj4 🔔𝐃𝐨𝐧'𝐭 𝐟𝐨𝐫𝐠𝐞𝐭 𝐭𝐨 𝐬𝐮𝐛𝐬𝐜𝐫𝐢𝐛𝐞 𝐭𝐨 𝐨𝐮𝐫 𝐜𝐡𝐚𝐧𝐧𝐞𝐥 𝐟𝐨𝐫 𝐦𝐨𝐫𝐞 𝐮𝐩𝐝𝐚𝐭𝐞𝐬. https://www.youtube.com/@Shalomacon/?sub_confirmation=1 🔗 Support Us Here! https://ift.tt/7BN2wVZ 🔗 Stay Connected With Us. Facebook: https://ift.tt/tAGCjoy Website: https://ift.tt/8FPlrcI 📩 For business inquiries: [email protected] ============================= 🎬Suggested videos for you: ▶️ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mbRsb3erMec ▶️ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t0eCU627KJs ▶️ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xbcJwTfJVxk ▶️ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pT4kknKAY4A ▶️ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uO9ky0FEj5A ================================= 🔎 Related Phrases: #humility #leadership #selfsacrifice #yeshua #torah #messianicteaching #biblicalexegesis #biblestudy #hebrewroots #torahportion #faithjourney #tetzaveh via Shalom Macon https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCSXxCAqjFHtmNWLDiAndiLg March 08, 2025 at 01:00AM

#confidence#messianic#torahportion#yeshua#jewish#holyspirit#christology#spiritualtransformation#faith#Youtube

0 notes

Text

MAN OF PEACE

Moses is true and his Torah is true. (Talmud, Bava Batra 74a) Be of the disciples of Aaron; one who loves peace, pursues peace, loves God’s creatures and draws them close to Torah. (Ethics of the Fathers 1:12) Moses was the greatest prophet in Jewish history. He brought the Jews out of Egypt, received the Torah at Mt. Sinai, and led his people in the wilderness for 40 years. Yet the Lubavitcher Rebbe reminds us that another great man was always at Moses’ side: his older brother Aaron, an individual of unparalleled benevolence who didn’t resent Moses for his privileged upbringing in the palace or status as God’s chosen messenger. Leading the Jewish people was a team effort. Moses and Aaron’s roles were different yet complementary, as we see in this week’s parsha, Tetzaveh. Moses is responsible for bringing oil to light the ever-burning menorah in the Mishkan (Tabernacle), while Aaron is in charge of actually lighting the menorah. Both Moses and Aaron’s unique gifts were required to turn a notoriously stiff-necked people into God’s representatives on earth and a light unto the nations. The Midrash characterizes each man’s personal characteristics by referring to a verse from Psalms, “Benevolence and truth are met together; righteousness and peace have kissed.” (Ps. 85:11) Aaron represents benevolence and peace, while Moses represents truth and righteousness. Righteous Moses brought the truth from Mount Sinai; benevolent Aaron helped the people live peacefully by that truth. Moses brings the oil, Aaron lights it.

Image: “Aaron, High Priest of the Israelites” by Anton Kern, 1747 (detail)

Dedicated by Steve Potter

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Rabbi Benny's Weekly Torah Thought - Keeping it short, meaningful and contemporary.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

I remember discovering incense at Venice Beach...and other reminiscences after this week's Torah portion. #torah #poetry #tetzaveh Light up this text here: https://jewishpoetry.net/smoke-a-poem-for-parsha-tetzaveh-aliyah-7/

0 notes

Text

youtube

My mother was a Cohen so I may have "priest" running through my veins...Here's a new video from my God Wrestler book poem for this week's Torah portion. P.S. I don’t own a tie.

Following along with the text at https://jewishpoetry.net/tetzaveh/

0 notes