#The Dominicans or Black Friars

Text

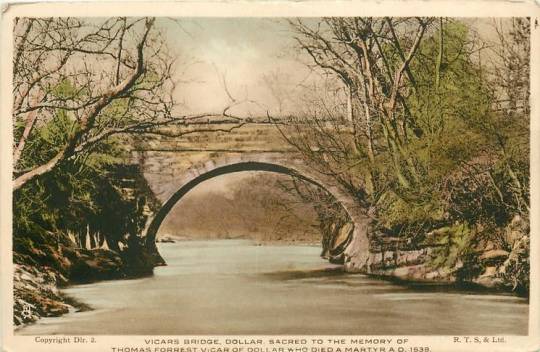

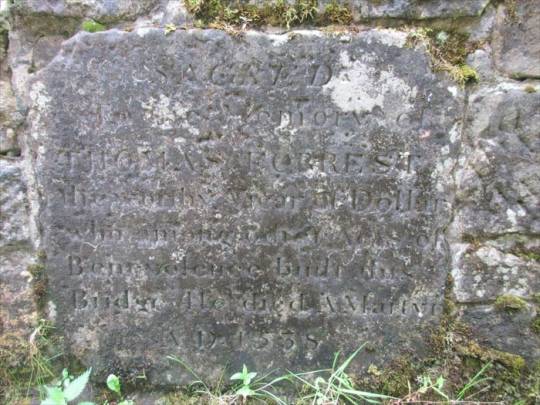

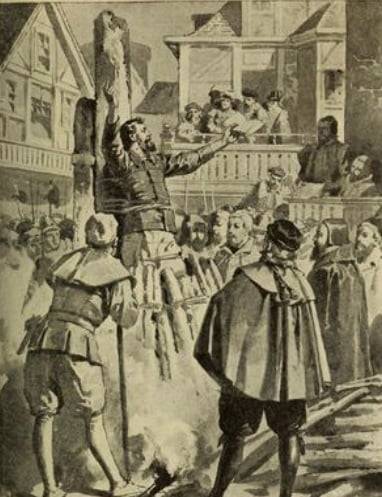

On 28th February, 1539, Thomas Forret, the Vicar of Dollar, John Keillor and John Beveridge, two black-friars, Duncan Simpson a priest, and a gentleman named Robert Forrester, were all burned together on the Castle Hill on a charge of heresy.

The persecution of Protestants in Scotland, at least if measured in martyrdoms, peaked in 1539, shortly after Cardinal David Beaton, a zealous opponent of reform, was appointed primate of the country, although from the info I have picked up one John Lauder, would have been the man condemning these men, he was Scotland’s Public Accuser of Heretics at the times. Heretics being anyone who didn’t follow the Catholic faith.

Of the five “heresiarchs” executed in Edinburgh, none had quite so fascinating a tale as Thomas Forret, an Augustinian monk turned Vicar whose passion for Scripture and preaching, coupled with frank observation of the institutional Church’s doctrinal and practical failings, earned him a place at the stake at the crest of the Royal Mile, just east of Edinburgh Castle.

Forret had been warned by the high heid yins about his behaviour on the pulpit a few times, one occasion said his sermons might lead to “make the people thinke” but, a very smart man, he rebuked the accusations of going against the lords work by quoting scriptures and his quick wit. At the time in Scotland the sermons were traditionally performed by “Black Friars” and “Grey Friars” That’s Dominican and Franciscan Monks to you and I!

It would all come undone in 1539 when Forret attended the wedding of the Priest of Tullibody, which attendance, no less than the marriage itself, flouted the Church’s stance position on clerical celibacy. Forret had added insult to injury by eating meat at his fellow curate’s wedding celebration, despite the fact that it was Lent.

So grievous were Forret’s collective crimes that, at his trial, he was condemned to death “without anie place for recantatioun.”

Subsequently brought to the place of his execution, a certain Friar Hardbuckell encouraged him to save his soul by confessing his faith in God. “I beleeve in God,” Forret replied. Hardbuckell then encouraged him to confess his faith in the Virgin Mary by adding the words “and in our Ladie.” Forret answered, “I beleeve as our Ladie beleeveth,” thereby maintaining to the end the perfect and full sufficiency of Christ’s saving work for sinners.

Forret’s wit and knowledge of Scripture stayed with him to his very last breath. Having been preceded to the gallows by one of his fellow martyrs, Forret called the same a “wily fellow” who wished to arrive at the feast awaiting them in heaven before the others in order to secure a good seat. As the noose was placed around his neck, he began to recite Psalm 51 in Latin: Misere mei, Deus, secundum magnam misericordiam tuam. “Have mercy on me, O God, according to your steadfast love.” Thus he continued “till they pulled the stoole frome under his feete, and so wirried [hanged], and after burnt him.”

Pics are of a memorail stone and bridge over the River Devon between the village of Blairingone and Dollar on the border of Clackmannanshire and Kinross-shire

Much more on the unfortunate man here https://www.reformation21.org/.../scotlands-protestant...

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

a couple months ago a coworker of mine told me that a teacher of hers at a Catholic school she went to told her that black people and gingers are descended from the devil and can't go to heaven (the coworker was black). it had wrecked her faith.

I almost blew a fuse.

👏HERESY👏ISN'T👏HARMLESS👏

somebody needed to call the Dominicans Friars on that teacher's ass. unacceptable.

And now through the new Adam, who is Christ, there is established a brotherly union between man and man, and people and people; just as in the order of nature they all have a common origin, so in the order which is above nature they all have one and the same origin in salvation and faith; all alike are called to be the adopted sons of God and the Father, who has paid the self same ransom for us all; we are all members of the same body, all are allowed to partake of the same divine banquet, and offered to us all are the blessings of divine grace and of eternal life.

-Pope Leo XIII, encyclical In Plurimis

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

SAINT OF THE DAY (August 17)

Hyacinth was a Polish Dominican priest and missionary who worked to reform the women's monasteries in his native Poland.

He was one of the first members of the Dominicans ('Order of Preachers').

He is called the "Apostle of the North" and the "Apostle of Poland."

Hyacinth was born into nobility in 1185 at the castle of Lanka at Kamin in Silesia, Poland.

He received an impressive education, becoming a Doctor of Law and Divinity before traveling to Rome with his uncle, Ivo Konski, the Bishop of Krakow.

In Rome, he met St. Dominic and decided to join the Order of Preachers immediately, receiving his habit from Dominic himself in 1220.

After his novitiate, he made his religious profession and was made superior of the little band of missionaries sent to Poland to preach.

In Poland, the new preachers were well received and their sermons produced a deep conversion in the people.

Hyacinth also founded communities in Sandomir, Kracow, and Plocko on the Vistula in Moravia.

He extended his missionary work through Prussia, Pomerania, and Lithuania.

Then, crossing the Baltic Sea, he preached in Denmark, Sweden, Norway, and Russia, reaching the shores of the Black Sea.

On his return to Krakow, he died on 15 August 1257.

Some of his relics can be found at the Dominican church in Paris.

St. Hyacinth is a patron of Poland.

One of the major miracles attributed to Hyacinth came about during the Siege of Kiev in 1240.

As the friars prepared to flee the invading forces, Hyacinth went to save the ciborium containing the Eucharist from the tabernacle in the monastery's chapel, when he heard the voice of Mary asking him to take her too.

Hyacinth lifted the large, stone statue of Mary, as well as the ciborium.

He was easily able to carry both, even though the statue weighed far more than he could normally lift. Thus, he saved them both.

For this reason, he is usually shown holding a monstrance (though they did not come into use until several centuries later) and a statue of Mary.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

I can't set your world on fire so I will set my own ablaze

Because as much as I hate you for this I would never hurt you

But I will scorch my own earth to the third degree

Grotesque burns

Covering all the masses

Makes up for all the ones I never went to

Went to church for the first time in years

Black Friars in Oxford

They say the word

Dominican

And I can only think of you

- G.M

#poem#poetry#original poem#original poetry#writersblr#creative writing#spilled ink#spilled poetry#poets of tumblr#poetblr#writeblr#writeblrcafe#poeticstories

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

MARKING THE FACE, CURING THE SOUL?: READING THE DISFIGUREMENT OF WOMEN IN THE LATER MIDDLE AGES

“It is taken as read that the sight of a mutilated female face could engender horror and shock in the medieval viewer, and that this generated (and possibly exaggerated) the reports we now have of its occurrence. It was precisely this response that the Franciscan missionary William of Rubruck intended to elicit when he reported his encounter with the wife of the Mongol leader ‘Scacatai’ in 1253.

William commented that: De qua credebam in veritate, quod amputasset sibi nasum inter oculos ut simior esset: nihil enim habebat ibi de naso, et unxerat locum ilium quodam unguento nigro, et etiam supercilia: quod erat turpissimum in oculis nostris. [I was really under the impression that she had amputated the bridge of her nose so as to be more snub-nosed, for she had no trace of a nose here, and she had smeared that spot and her eyebrows as well with some black ointment, which to us looked thoroughly dreadful.]

Elsewhere he deduced from this that such flatness was a marker of beauty within Mongol culture, and that ‘Quæ minus habet de naso pulchrior reputatur. Deturpant etiam turpiter pinguedine facies suas’ [the less nose one has, the more beautiful she is considered, and they disfigure themselves horribly, moreover, by painting their faces]. William’s comments are of course designed to convey to the western European readers of his report – most notably King Louis IX of France to whom he addressed it – the strangeness of his hosts.

Part of the process of ‘othering’ the Mongols was to draw contrasts between their behaviours and those of Westerners, and the appearance and practices of the women, although not strictly a matter with which a Franciscan friar should have been concerned, was just one noticeable difference among many. There is, however, another dimension to William’s sketch of the Mongol women: although he highlights the flatness of their noses as ‘hideous’ and attributes at least one case to deliberate surgery, he does not draw any comparisons about the meaning of this facial feature in his own world.

Yet the bridgeless or flattened nose was commonly thought in the later medieval West to be a sign of leprosy, which itself was associated with dubious morality, whilst a deliberately cut or maimed nose came increasingly to signify a punishment for sexual misdemeanour on the woman’s part. He left it to his readers to make such connections.

The Vita of St Margaret of Hungary (d. 1270), however, provides a striking counterpart to William’s text. For, against the same background of Mongol aggression, this Hungarian princess, given to the Dominican order in childhood, stated that, should the ‘Tartars’ invade Hungary, she would cut off her lips to ensure they found her so repulsive as to leave her unviolated.

Yet her hagiographer relates that when repelling (Western) suitors for her hand in marriage, she declared that she would rather cut off her nose and lips, and gouge out her eyes, than marry any of the three royal suitors proposed. Herein lies the paradox of facial damage for women.

The account of Margaret’s threat of self-mutilation to preserve her virginity against both pagan aggressors and Christian suitors belonged to a long tradition of ‘the heroics of virginity’: St Brigit of Ireland was said to have gouged out her own eye to avoid marriage, whilst one of the most celebrated cases of collective self-mutilation was that of Abbess Ebba and the nuns at Coldingham in England, faced with the prospect of Viking invaders.

Nevertheless the action that Margaret was proposing – which in the context of the approaching pagan Mongols had strong parallels with Ebba’s –would not only leave her open to wound-related infection or even death, but also render her face similar to mutilated criminals, adulterers, pimps and fornicators.

A generation earlier than William’s expedition and Margaret’s vita, legal texts were being promulgated in southern Europe which threatened the slitting of women’s noses (and thus flattening them in grotesque form) for instances of sexual misdemeanours. For example, the laws of Frederick II for Sicily (based on earlier provisions of King Roger II) imposed nose-slitting on adulteresses and mothers who pimped their daughters.

The chronology matters: such a measure had been unknown in western Europe before the eleventh century (although, as we have seen, it was mentioned in earlier Byzantine law). Thus earlier examples of threatened or actual self-mutilation differed starkly from Margaret’s message to her parents: if they forced her to break her monastic vow, they gave her no choice but to carry out an action that would reduce her –irremediably – to the status of marked whore.

The fear of sexual violation, then, drove Margaret’s intention to maim herself, mirroring contemporary legal punishments for sexual and other transgressions. Like most of the cases considered in this chapter, however, it was merely the threat of self-mutilation, rather than its actual practice, that was an effective deterrent. This is a point somewhat overlooked by those convinced that the high and late Middle Ages were a theatre of cruelty.

Moreover, we need to ask how Margaret’s religious commitment, and its subsequent reporting in hagiography, may or may not reflect the secular world. The records we have of actual judicial processes often stop at a court’s verdict – the sentence of mutilation, rather than its actual execution – and women form a very small minority of those so sentenced. In fact, cases of women actually being judicially mutilated are quite rare, and not all examples were for cases of immorality.

Helen Carrel has argued that ‘The threat of harsh punishment, which was then ultimately remitted, was a set piece of medieval legal practice’, and suggests that, although mutilation was prescribed for many offences, it was rarely put into practice after the late thirteenth century. Margaret’s threat, therefore, might be understood as just that – its extremity designed to convey her deep-seated religious commitment through the idea of radical, physical self-harm, invoking an image in the reader’s mind but not carried out in practice.

Elsewhere in the secular world, the late fifteenth- and early sixteenth-century German and Swiss urban records studied by Groebner reveal definitive evidence of actual facial mutilation taking place, but the targeting of the face of suspected or actual adulterers outlasted formal, juridical ‘mirror punishments’ by the authorities by the fifteenth century, and seems to have been an extreme, and unsanctioned, act of anger carried out on the face of a spouse suspected of adultery, or her/his lover, or even on the innocent partner of the lover.

Such ‘private’ attacks, Groebner suggests, were still driven by the association of adultery with facial punishment, but these incidents make it into the records so that the attackers might be censured (somewhat lightly, given the injuries they inflicted). This unofficial understanding of violent, facial punishment against women for their perceived lapses may already have been an accepted social norm in other regions by the thirteenth century.

Again, evidence comes from the records of proceedings against the perpetrator of the violence. A hearing before the podestà’s court in Venice in May 1291 centred on the assault of Bertholota Paduano of Torcello by a priest from the island of Burano. Bertholota testified that when she defended her friend Maria against the priest’s slanderous words: et percussit dictam Bertholotam sub oculo sinistro cum digito, et postea cum pugno bis per caput, scilicet semel per vultum iuxta nasum, talieter quod sanguis exivit ei per buccam et per nasum et alia vice iuxta aurem, et postea iniuravit ei dicens, ‘Turpis vilis meretrix, nunc aliquantulum feci vincdictam [sic] de te, vade acceptum bastardos quos fecisti de Valentio, quia sum dolens et tristis quod non proieci ipsam in aquam’.

[The above parish priest raised his hand and hit the above Bertholota with his hand below her left eye, and then twice with his fist on her head: that is, on her face by her nose, so that blood began to flow from her mouth and nose, and another way by her ear, and afterwards he injured her, saying: ‘You shameful and vile whore, now I have given you a little punishment [my emphasis], go, and take the bastards you had by Valentio with you, for I am grieving and sad that I did not throw her [Maria] in the water.’]

Further witnesses added that they heard the priest say, ‘Illa turpis meretrix; modo feci quod cupivi et, nisi fuisset pro presbitero qui eam defensavit, male apparassem eam.’ [‘She is a filthy whore; now I have done what I wanted to do, and had it not been for the priest who defended her, it would have gone badly for her.’] We do not know how this case ended – presumably the clerical perpetrator of the assault would have objected to being hauled up before the secular podestà’s court and the case may well have been referred to his clerical superiors, which would explain the lack of sentencing as it survives in the podestà’s records.

What the hearing did to Bertholota’s reputation is also unknown, but the record is revealing in how it presents the case, and what it chooses to include. Arguably, the victim’s physical appearance after the attack (temporarily bloodied face and black eyes, and more permanently a probable broken nose) would have raised questions about her status as a respectable woman, but it is striking that she is named in the record whilst her assailant is not, and that her reputation as a whore was rehearsed in court (twice) and then written down.

The case itself may therefore have been more punitive on her than on him, and this may have been the latter’s intention. He was, after all, a priest, and may well have considered himself within his rights to challenge Bertholota’s (and Maria’s, for that matter) way of conducting their lives, particularly if Bertholota’s children had been born out of wedlock as the record suggests. But it is clear that there was a distinction to be drawn between legally-sanctioned punishment, controlled by the Venetian state, and the violence occasioned by this individual’s sense of outrage against the women.

Religion is present here of course – the assailant was a priest – but his actions were hardly designed to bring Bertholota to repentance. The theme of the punished fornicator brings us to our second holy woman, in the form of St Margaret of Cortona. Her lengthy vita, consisting almost entirely of Margaret’s dialogues with Christ (and thus effectively positioning her in a face-to-face relationship with him), centres on Margaret’s remorse at her previous life of sexual freedom that had resulted in her bearing an illegitimate child.

Margaret was apparently strikingly beautiful, and the motif of denying this beauty recurs throughout the life, as she struggles ever closer to her true love, Christ himself. Early in the life Christ says: ‘Recordare, quod tui aspectus decorem, quem hactenus in mei magnam injuriam conservare conata es, imo et augere, adeo abhorrere et odire coepisti, ut nunc abstinentia, nunc lapidis allisione, nunc pulveris ollarum appositione, nunc diminutione frequenti sanguinis, delere desiderasti.’

[‘Remember how you previously endeavoured to maintain and even increase your beautiful appearance, much to my injury, and now you have begun to abhor and hate it, so that now you desire to rub it out with fasting, by dashing your skin with stones, by covering it with dust, and by frequent bleeding.’]

But such trials are not yet enough – when Margaret asks Christ to call her ‘daughter’, he replies rather tersely, ‘Non adhuc vocaberis filia, quia filia peccati es; cum vero a tuis vitiis integraliter per generalem confessionem iterum purgata fueris, te inter filias numerabo’ [‘You won’t be called daughter yet, for you are the daughter of sin. Only when you are completely purged of your vices by constant confession, then I will count you among my daughters.’].

This handily reminds us that Margaret had to overcome not only her past life, but her very status as woman, as a daughter of Eve, whose original sin marked her with a sexuality that fasting, scarification and the denial of bodily comforts could only control, not destroy. Margaret’s request to become a recluse is also refused, by God, who has other plans for her.

The vita was written by Margaret’s confessor, and he has a major role to play as she becomes increasingly frustrated by her failure to achieve her goal. Seeing that her abstinence is not destroying the beauty of her face fast enough, she secretly hides a razor and asks her confessor’s permission to use it to cut off her nose and top lip, for ‘Et merito, inquit, hoc vigilanter desidero, quia vultus mea decor multorum animas vulneravit’ [‘I deserve it and strongly wish it, since the beauty of my face has injured the souls of many’].

But he refuses permission, and threatens not to hear her confession again if she carries out her intent. Margaret’s later request to Christ, to afflict her with leprosy, meets a similar refusal. If she wanted to reach Christ, the message appears to be that she had to do it the hard way, not by quick solutions such as enclosure, self-harm or disease.”

- Patricia Skinner, Medicine, Religion, and Gender in Medieval Culture

#cw: racism#cw: self harm#beauty#gender#religion#medieval#christian#patricia skinner#medicine religion and gender in medieval culture

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

© CC BY-SA 4.0/JMkissme

Filipinos have been praying to Our Lady of the Rosary since the 17th century

The Basilica of Our Lady of Piat is located on the outskirts of the town of Piat, in the province of Cagayan, Philippines.

In 1604, Dominican friars brought to the Philippines a statue of the Black Madonna, invoked as "Our Lady of the Holy Rosary". The statue was enthroned in Piat, in a small shrine, on the feast of Saint Stephen, December 26, 1623. It was incredible that such a great multitude should have gathered there, given that the area was not densely populated, and the work of evangelization had only begun 25 years earlier.

Our Lady of Piat was carried in procession to other towns, which is why she is also called Our Lady of the Visitation.

In the 17th century, the Visitation was celebrated on July 2, so the shrine's feast day is still celebrated on July 2.

On June 22, 1999, the shrine was elevated to the rank of Minor Basilica.

Our Lady of Piat is credited with many miracles.q

Marian Encyclopedia

0 notes

Photo

San Vicente Ferrer, Tayabas A small coastal town in between Gumaca and Lopez, Tayabas (now Quezon and Aurora), named after its patron Saint, Saint Vincent Ferrer, a Spanish Dominican missionary and logician who also had a sticky record regarding conversion of Jewish people to Christianity. Established by the Dominicans decades after the founding of Gumaca, it was nestled at the foot of the Sierra Madre mountain range with its rainforests and the coastal line of Lamon Bay, a part of it populated by mangroves and another part by black sand. People rely on farming and fishing for sustenance. First administered by Dominican friars, the gobernadorcillos later replaced them as heads of the town throughout the Spanish period. Later on, the presidentes municipal headed the town during the American occupation. It was a town fortified by a long line of walls and little fortresses to protect itself from invaders, though now the walls were reduced to rubble. The town celebrated the feast of its patron saint on April 5, but there were times it overlapped with the remembrance of the Holy Week. Youngsters would joke that whenever it did occur, they would spend more time mumbling prayers and listening to the pasyon than the lively band music and flirting with each other whenever they could. If they did, it would be after the Holy Week. Prominent families dominating the politics of the town include the Herreras, a family of public servants headed by the one-time presidente municipal Don Gerardo; the Asilos, known for their patriarch's and young scion's poltical and business savvy (the patriarch also participated in taking down the Rios Revolt); the Dinsmores, whose head of the family was an American who settled in the Islands and were just as unscrupulous; the de Ocampos with its overtly religious patriarch with the tendency to stick with anyone just as powerful in the land; and the Villareals who once made their mark with their liberal ideas only to be taken down by enemies on imagined allegations.

#municipality of san vicente ferrer#san vicente ferrer#fictional town#original fic#original fic: los cuentos de san vicente ferrer#graphics

0 notes

Text

Black Friars (Dominicans/Order of Preachers) Chapel, Oxford University

1 note

·

View note

Photo

On 28th February, 1539, Thomas Forret, the Vicar of Dollar, John Keillor and John Beveridge, two black-friars, Duncan Simpson a priest, and a gentleman named Robert Forrester, were all burned together on the Castle Hill on a charge of heresy.

The persecution of Protestants in Scotland, at least if measured in martyrdoms, peaked in 1539, shortly after Cardinal David Beaton, a zealous opponent of reform, was appointed primate of the country, although from the info I have picked up one John Lauder, would have been the man condemning these men, he was Scotland’s Public Accuser of Heretics at the times. Heretics being anyone who didn’t follow the Catholic faith.

Of the five “heresiarchs” executed in Edinburgh, none had quite so fascinating a tale as Thomas Forret, an Augustinian monk turned Vicar whose passion for Scripture and preaching, coupled with frank observation of the institutional Church’s doctrinal and practical failings, earned him a place at the stake at the crest of the Royal Mile, just east of Edinburgh Castle.

Forret had been warned by the high heid yins about his behaviour on the pulpit a few times, one occasion said his sermons might lead to “make the people thinke” but, a very smart man, he rebuked the accusations of going against the lords work by quoting scriptures and his quick wit. At the time in Scotland the sermons were traditionally performed by “Black Friars” and “Grey Friars” That’s Dominican and Franciscan Monks to you and I!

It would all come undone in 1539 when Forret attended the wedding of the Priest of Tullibody, which attendance, no less than the marriage itself, flouted the Church’s stance position on clerical celibacy. Forret had added insult to injury by eating meat at his fellow curate’s wedding celebration, despite the fact that it was Lent.

So grievous were Forret’s collective crimes that, at his trial, he was condemned to death “without anie place for recantatioun.”

Subsequently brought to the place of his execution, a certain Friar Hardbuckell encouraged him to save his soul by confessing his faith in God. “I beleeve in God,” Forret replied. Hardbuckell then encouraged him to confess his faith in the Virgin Mary by adding the words “and in our Ladie.” Forret answered, “I beleeve as our Ladie beleeveth,” thereby maintaining to the end the perfect and full sufficiency of Christ’s saving work for sinners.

Forret’s wit and knowledge of Scripture stayed with him to his very last breath. Having been preceded to the gallows by one of his fellow martyrs, Forret called the same a “wily fellow” who wished to arrive at the feast awaiting them in heaven before the others in order to secure a good seat. As the noose was placed around his neck, he began to recite Psalm 51 in Latin: Misere mei, Deus, secundum magnam misericordiam tuam. “Have mercy on me, O God, according to your steadfast love.” Thus he continued “till they pulled the stoole frome under his feete, and so wirried [hanged], and after burnt him.”

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

SOUTH SUBURBAN CHAPTER EVENT OCTOBER 20

Thursday, October 20 at 7:30 PM CT

(In-Person and via ZOOM)

South Suburban Archaeological Society (SSAS) presents:

"Archaeological Excavations at the Black Friary in Trim, Ireland"

with Dr. Rachel Scott, DePaul University

In AD 1263, Geoffrey de Geneville, Lord of Trim, founded a Dominican friary north of the town wall. The Black Friary was a powerful institution in medieval Trim, as indicated by its extensive lands and its use for ecclesiastical and governmental meetings. Following its dissolution under Henry VIII, the friary fell into disrepair and was eventually sold as a quarry in the 1750s. The memory of the place, however, remained, and the site was never built over. Ongoing excavations since 2010 are uncovering a complex sequence of burial and other activities dating from the 13th to the 20thcenturies. During the late medieval period, the friary provided a final resting place for the Dominican friars, as well as lay individuals living around Trim. Post-dissolution, the local Catholic population continued to inter their dead within the church and cemetery. Then, after the demolition of the buildings, the site was used for both farming and the burial of unbaptized children. Dr. Scott will trace the history of the Black Friary, illuminating its long relationship with the town of Trim.

NOTE: Dr. Scott will be appearing in person at the Irwin Center (18120 Highland Ave., Homewood, IL). Please join us for light refreshments before the program. This event is free and open to the public.

Those who wish to view this presentation remotely via Zoom should send an email requesting access to the link below. If at all possible, please make your request at least 24 hours prior to the program. Include enough information in the email to verify your identity. A day or two before the program, the host will respond with an invitation to attend through Zoom.

[email protected]

For further information, please visit the website of the South Suburban Archaeological Society.

0 notes

Text

SOUTH SUBURBAN CHAPTER EVENT OCTOBER 20

Thursday, October 20 at 7:30 PM CT

(In-Person and via ZOOM)

South Suburban Archaeological Society (SSAS) presents:

"Archaeological Excavations at the Black Friary in Trim, Ireland"

with Dr. Rachel Scott, DePaul University

In AD 1263, Geoffrey de Geneville, Lord of Trim, founded a Dominican friary north of the town wall. The Black Friary was a powerful institution in medieval Trim, as indicated by its extensive lands and its use for ecclesiastical and governmental meetings. Following its dissolution under Henry VIII, the friary fell into disrepair and was eventually sold as a quarry in the 1750s. The memory of the place, however, remained, and the site was never built over. Ongoing excavations since 2010 are uncovering a complex sequence of burial and other activities dating from the 13th to the 20thcenturies. During the late medieval period, the friary provided a final resting place for the Dominican friars, as well as lay individuals living around Trim. Post-dissolution, the local Catholic population continued to inter their dead within the church and cemetery. Then, after the demolition of the buildings, the site was used for both farming and the burial of unbaptized children. Dr. Scott will trace the history of the Black Friary, illuminating its long relationship with the town of Trim.

NOTE: Dr. Scott will be appearing in person at the Irwin Center (18120 Highland Ave., Homewood, IL). Please join us for light refreshments before the program. This event is free and open to the public.

Those who wish to view this presentation remotely via Zoom should send an email requesting access to the link below. If at all possible, please make your request at least 24 hours prior to the program. Include enough information in the email to verify your identity. A day or two before the program, the host will respond with an invitation to attend through Zoom.

[email protected]

For further information, please visit the website of the South Suburban Archaeological Society.

0 notes

Text

SAINTS OF THE DAY (February 17)

The Seven Holy Founders of the Servite Order were seven men from the town of Florence who became bound to each other in a spiritual friendship.

The Seven Holy Founders are Saints Bonfilius, Alexis Falconieri, John Bonagiunta, Benedict dell'Antella, Bartholomew Amidei, Gerard Sostegni, and Ricoverus Uguccione.

They led lives as hermits on Monte Senario. They had a special devotion to the Blessed Virgin Mary.

On Friday, 13 April 1240, the hermits received a vision of Our Lady.

She held in her hand a black habit, and a nearby angel bore a scroll reading "Servants of Mary."

Mary told them:

"You will found a new order, and you will be my witnesses throughout the world. This is your name: Servants of Mary.

This is your rule: that of Saint Augustine.

And here is your distinctive sign: the black scapular, in memory of my sufferings."

They accepted the wisdom of Our Lady, wrote a Rule based on Saint Augustine and the Dominican Constitutions, adopted the black habit of an Augustinian monk, and lived as mendicant friars.

The men founded the Order of Servites, which received the approval of the Holy See in 1304.

Servite, a Roman Catholic order of mendicant friars — religious men who lead a monastic life, including the choral recitation of the liturgical office, but do active work — founded in 1233 by a group of seven cloth merchants of Florence.

They are venerated on February 17 because it is said to be the day on which Saint Alexis Falconieri, one of the seven, died in 1310.

All seven were beatified on 1 December 1717 by Pope Clement XI. They were canonized by Pope Leo XIII on 15 January 1888.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Black legend of the spanish inquisition

Saying that the Spanish crown attempted to mitigate the worst abuses by passing laws, or that these systems resembled indigenous systems like the mit’a in Peru, hardly justifies the slavery and barbarism that resulted. Similarly, it has been argued that with the Spanish Inquisition, procrastination and rationalization were the norm, unlike those other European powers where witch trials and executions were carried out more thoroughly.īut is evil a relative term? It really is impossible to defend the encomienda and repartimiento and hacienda forced labor systems employed throughout the Spanish colonies. It has been argued that in fact the Spanish were half-hearted imperialists, compared with the other European powers, and that unlike those others they were subjected to harsh internal criticism early on by Las Casas ( A Brief Account of the Destruction of the Indies/Brevísima relación de la destrucción de las Indias, 1552). The term "The White Legend" was invented subsequently, during the Franco era, to present Spain's imperial era in a more positive light. But the extremely graphic images of death and dismemberment created an image of Spanish imperialism that would persist for centuries. But were they also propaganda?ĭe Bry, who was born in Liège in 1561 into a Lutheran family, printed engraved illustrations that purported to show life in the Americas (he was based in Frankfurt). The woodcuts illustrated books by the Dominican friar Bartolomé de las Casas and the Italian traveler Girolamo Benzoni, among others, and they were bestsellers. This was a time when the woodcuts of Theodor de Bry (like the one above) appeared and they swayed public opinion. The formative period for The Black Legend was in the 1590’s and early 1600’s, following the Spanish occupation of the Netherlands and the threatened invasion of England in 1588. Was colonialism and occupation worse under the Spanish? He had a point of course, but he argued this when Spain’s empire was already over. Those enemies, he argued, were Protestant countries who engaged in their own empire-building – the Dutch, the English, the Germans and the French too - enemies who resented Spain’s successes. He was referring to the way Spain’s era of imperial conquest in the Americas had been blackened over the centuries by Spain’s enemies. The Black Legend (La leyenda negra) was a term invented by Spanish historian Julián Juderías y Loyot in 1914.

0 notes

Photo

The Dominicans or Black Friars

The thirteenth century saw the romantic rise, the marvellous growth, and then the inevitable decay of the Friars, the two orders whose careers form one of the most fascinating and impressive stories in modern history. The Franciscans, or Grey Friars, founded in 1212, the Dominicans, or Black Friars, founded in 1216, by the middle of the century had infused new life throughout the Catholic world. By the end of the century their power was spent, and they had begun to be absorbed in the general life of the Church. It was one of the great rallies of the Papal Church, perhaps of all the rallies the most important, certainly the most brilliant, most pathetic, most fascinating, the most rich in poetry, in art, in devotion. For the mediaeval Church of Rome, like the Empire of the Caesars at Rome, like the Eastern Empire of Constantinople, like the Empire of the Khalifs, which succeeded that, seems to subsist for centuries after its epoch of zenith by a long series of rallies, revivals, and new births out of almost hopeless disorganisation and decay sofia city tour.

But the thirteenth century is not less memorable for its political than for its spiritual history. And in this field the history is that of new organisations, not the dissolution of the old. The thirteenth century gave Europe the nations as we now know them. France, England, Spain, large parts of North and South Germany, became nations, where they were previously counties, duchies, and fiefs. Compare the’ map of Europe at the end of the twelfth century, when Philip Augustus was struggling with Richard 1., when the King of England was a more powerful ruler in France than the so-called King of France in Paris, when Spain was held by various groups of petty kinglets facing the solid power of the Moors, compare this with the map of Europe at the end of the thirteenth century, with Spain constituted a kingdom under Ferdinand in. and Alfonso x., France under Philip the Fair, and England under Edward I.

At the very opening of the thirteenth century John did England the inestimable service of losing her French possessions. At the close of the century the greatest of the Plantagenets finally annexed Wales to England and began the incorporation of Scotland and Ireland. Of the creators of England as a sovereign power in the world, from Alfred to Chatham, between the names of the Conqueror and Cromwell, assuredly that of Edward I. is the most important. As to France, the petty counties which Philip Augustus inherited in 1180 had become, in the days of Philip the Pair (1286-1314), the most powerful nation in Europe. As a great European force, the French nation dates from the age of Philip Augustus, Blanche of Castile, her son Louis ix. (the Saint), and the two Philips (ill. and iv.), the son and grandson of St. Louis. The monarchy of France was indeed created in the thirteenth century. All that went before was preparation: all that came afterwards was development. Almost as much may be said for England and for Spain.

Hundred years of European history

It was an age of great rulers. Indeed, we may doubt if any hundred years of European history has been so crowded with great statesmen and kings. In England, Stephen Langton and the authors of our Great Charter in 1215; William, Earl Mareschal, Simon de Montfort, Earl of Leicester, and above all Edward 1:, great as soldier, as ruler, as legislator — as great when he yielded as when he compelled. In France, Philip Augustus, a king curiously like our Edward 1. in his virtues as in his faults, though earlier by three generations; Blanche, his son’s wife, Regent of France; St. Louis, her son; and St. Louis’ grandson, the terrible, fierce, subtle, and adroit Philip the Fair.

Then on the throne of the Empire, from 1220 to 1250, Frederick II., ‘the world’s wonder,’ one of the most brilliant characters of the Middle Ages, whose life is a long romance, whose many-sided endowments seemed to promise everything but real greatness and abiding results. Next, after a generation, his successor, less brilliant but far more truly great, Rudolph of Hapsburg, emperor from 1273 to 1291, the founder of the Austrian dynasty, the ancestor of its sovereigns, the parallel, I had almost said the equal, of our own Edward 1. In Spain, Ferdinand 111. and his son, Alfonso x., whose reigns united gave Spain peace and prosperity for fifty-four years (1230-1284).

0 notes

Photo

The Dominicans or Black Friars

The thirteenth century saw the romantic rise, the marvellous growth, and then the inevitable decay of the Friars, the two orders whose careers form one of the most fascinating and impressive stories in modern history. The Franciscans, or Grey Friars, founded in 1212, the Dominicans, or Black Friars, founded in 1216, by the middle of the century had infused new life throughout the Catholic world. By the end of the century their power was spent, and they had begun to be absorbed in the general life of the Church. It was one of the great rallies of the Papal Church, perhaps of all the rallies the most important, certainly the most brilliant, most pathetic, most fascinating, the most rich in poetry, in art, in devotion. For the mediaeval Church of Rome, like the Empire of the Caesars at Rome, like the Eastern Empire of Constantinople, like the Empire of the Khalifs, which succeeded that, seems to subsist for centuries after its epoch of zenith by a long series of rallies, revivals, and new births out of almost hopeless disorganisation and decay sofia city tour.

But the thirteenth century is not less memorable for its political than for its spiritual history. And in this field the history is that of new organisations, not the dissolution of the old. The thirteenth century gave Europe the nations as we now know them. France, England, Spain, large parts of North and South Germany, became nations, where they were previously counties, duchies, and fiefs. Compare the’ map of Europe at the end of the twelfth century, when Philip Augustus was struggling with Richard 1., when the King of England was a more powerful ruler in France than the so-called King of France in Paris, when Spain was held by various groups of petty kinglets facing the solid power of the Moors, compare this with the map of Europe at the end of the thirteenth century, with Spain constituted a kingdom under Ferdinand in. and Alfonso x., France under Philip the Fair, and England under Edward I.

At the very opening of the thirteenth century John did England the inestimable service of losing her French possessions. At the close of the century the greatest of the Plantagenets finally annexed Wales to England and began the incorporation of Scotland and Ireland. Of the creators of England as a sovereign power in the world, from Alfred to Chatham, between the names of the Conqueror and Cromwell, assuredly that of Edward I. is the most important. As to France, the petty counties which Philip Augustus inherited in 1180 had become, in the days of Philip the Pair (1286-1314), the most powerful nation in Europe. As a great European force, the French nation dates from the age of Philip Augustus, Blanche of Castile, her son Louis ix. (the Saint), and the two Philips (ill. and iv.), the son and grandson of St. Louis. The monarchy of France was indeed created in the thirteenth century. All that went before was preparation: all that came afterwards was development. Almost as much may be said for England and for Spain.

Hundred years of European history

It was an age of great rulers. Indeed, we may doubt if any hundred years of European history has been so crowded with great statesmen and kings. In England, Stephen Langton and the authors of our Great Charter in 1215; William, Earl Mareschal, Simon de Montfort, Earl of Leicester, and above all Edward 1:, great as soldier, as ruler, as legislator — as great when he yielded as when he compelled. In France, Philip Augustus, a king curiously like our Edward 1. in his virtues as in his faults, though earlier by three generations; Blanche, his son’s wife, Regent of France; St. Louis, her son; and St. Louis’ grandson, the terrible, fierce, subtle, and adroit Philip the Fair.

Then on the throne of the Empire, from 1220 to 1250, Frederick II., ‘the world’s wonder,’ one of the most brilliant characters of the Middle Ages, whose life is a long romance, whose many-sided endowments seemed to promise everything but real greatness and abiding results. Next, after a generation, his successor, less brilliant but far more truly great, Rudolph of Hapsburg, emperor from 1273 to 1291, the founder of the Austrian dynasty, the ancestor of its sovereigns, the parallel, I had almost said the equal, of our own Edward 1. In Spain, Ferdinand 111. and his son, Alfonso x., whose reigns united gave Spain peace and prosperity for fifty-four years (1230-1284).

0 notes

Photo

The Dominicans or Black Friars

The thirteenth century saw the romantic rise, the marvellous growth, and then the inevitable decay of the Friars, the two orders whose careers form one of the most fascinating and impressive stories in modern history. The Franciscans, or Grey Friars, founded in 1212, the Dominicans, or Black Friars, founded in 1216, by the middle of the century had infused new life throughout the Catholic world. By the end of the century their power was spent, and they had begun to be absorbed in the general life of the Church. It was one of the great rallies of the Papal Church, perhaps of all the rallies the most important, certainly the most brilliant, most pathetic, most fascinating, the most rich in poetry, in art, in devotion. For the mediaeval Church of Rome, like the Empire of the Caesars at Rome, like the Eastern Empire of Constantinople, like the Empire of the Khalifs, which succeeded that, seems to subsist for centuries after its epoch of zenith by a long series of rallies, revivals, and new births out of almost hopeless disorganisation and decay sofia city tour.

But the thirteenth century is not less memorable for its political than for its spiritual history. And in this field the history is that of new organisations, not the dissolution of the old. The thirteenth century gave Europe the nations as we now know them. France, England, Spain, large parts of North and South Germany, became nations, where they were previously counties, duchies, and fiefs. Compare the’ map of Europe at the end of the twelfth century, when Philip Augustus was struggling with Richard 1., when the King of England was a more powerful ruler in France than the so-called King of France in Paris, when Spain was held by various groups of petty kinglets facing the solid power of the Moors, compare this with the map of Europe at the end of the thirteenth century, with Spain constituted a kingdom under Ferdinand in. and Alfonso x., France under Philip the Fair, and England under Edward I.

At the very opening of the thirteenth century John did England the inestimable service of losing her French possessions. At the close of the century the greatest of the Plantagenets finally annexed Wales to England and began the incorporation of Scotland and Ireland. Of the creators of England as a sovereign power in the world, from Alfred to Chatham, between the names of the Conqueror and Cromwell, assuredly that of Edward I. is the most important. As to France, the petty counties which Philip Augustus inherited in 1180 had become, in the days of Philip the Pair (1286-1314), the most powerful nation in Europe. As a great European force, the French nation dates from the age of Philip Augustus, Blanche of Castile, her son Louis ix. (the Saint), and the two Philips (ill. and iv.), the son and grandson of St. Louis. The monarchy of France was indeed created in the thirteenth century. All that went before was preparation: all that came afterwards was development. Almost as much may be said for England and for Spain.

Hundred years of European history

It was an age of great rulers. Indeed, we may doubt if any hundred years of European history has been so crowded with great statesmen and kings. In England, Stephen Langton and the authors of our Great Charter in 1215; William, Earl Mareschal, Simon de Montfort, Earl of Leicester, and above all Edward 1:, great as soldier, as ruler, as legislator — as great when he yielded as when he compelled. In France, Philip Augustus, a king curiously like our Edward 1. in his virtues as in his faults, though earlier by three generations; Blanche, his son’s wife, Regent of France; St. Louis, her son; and St. Louis’ grandson, the terrible, fierce, subtle, and adroit Philip the Fair.

Then on the throne of the Empire, from 1220 to 1250, Frederick II., ‘the world’s wonder,’ one of the most brilliant characters of the Middle Ages, whose life is a long romance, whose many-sided endowments seemed to promise everything but real greatness and abiding results. Next, after a generation, his successor, less brilliant but far more truly great, Rudolph of Hapsburg, emperor from 1273 to 1291, the founder of the Austrian dynasty, the ancestor of its sovereigns, the parallel, I had almost said the equal, of our own Edward 1. In Spain, Ferdinand 111. and his son, Alfonso x., whose reigns united gave Spain peace and prosperity for fifty-four years (1230-1284).

0 notes