#Ukraine Import Export Data

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Access verified Ukraine trade data, import export statistics, customs data, and trading partner insights with Eximpedia’s Exim Data Bank. Start exploring today!

#Ukraine Trade Data#Ukraine trade statistics#Ukraine Import Export Data#Ukraine Trading Partners#Ukraine Customs Data#Ukraine import data#Ukraine Export Data

0 notes

Text

Discover valuable global trade data by country with Seair Exim Solutions. Gain insights into market trends, import-export volumes, and optimize your business decisions.

#US Import Data#US Importer Data#ukraine import export data#Indonesia import export data#Bangladesh export import data

0 notes

Text

Top Ukraine Imports & Exports: Overview of Ukraine Import-Export Data

In today's global economy, understanding the import and export landscape of a country is crucial for businesses looking to expand internationally. Ukraine, located in Eastern Europe, is a key player in the international trade market. According to Ukraine import data and customs data on Ukraine imports, Ukraine’s goods imports reached a total value of $70.49 billion in 2024, an increase of 11% from 2023. As per the Ukraine export data, Ukraine exports accounted for $41.7 billion in 2024, a 13.4% increase from the previous year. In this article, we will delve into the top imports and exports of Ukraine, using data from Ukraine Import Data and Ukraine Export Data.

Ukraine Imports Overview

When looking at Ukraine's imports, it is clear that the country relies heavily on foreign goods to meet the needs of its population and industries. Some of the top imports of Ukraine include:

Energy Products: Ukraine is a major importer of energy products, such as oil, natural gas, and coal. These products are essential for powering the country's industries and meeting the energy needs of its people.

Machinery and Equipment: Ukraine imports a significant amount of machinery and equipment, including vehicles, electronics, and industrial machinery. These products are essential for modernizing the country's industries and infrastructure.

Chemicals: Ukraine also imports a large quantity of chemicals, including pharmaceuticals, fertilizers, and plastics. These products are crucial for various industries, such as agriculture, manufacturing, and healthcare.

Metals and Metal Products: Ukraine is known for its steel and metal production, but the country also imports metals and metal products to meet the demand of its industries.

Top 10 Ukraine Imports: Ukraine Import Data by HS Code (2024)

In the analysis of the top 10 Ukraine imports by HS Code for the year 2024, a comprehensive understanding of the country's trade dynamics is crucial. Ukraine's import data plays a pivotal role in recognizing the most significant goods being brought into the nation, shedding light on key sectors and economic trends. The top 10 goods that Ukraine imports, as per Ukraine customs data and Ukraine shipment data for 2024, include:

Mineral fuels and oils (HS code 27) $8.89 billion (12.62%)

Electrical machinery and equipment (HS code 85) $8.37 billion (11.87%)

Vehicles (HS code 87) $7.54 billion (10.7%)

Nuclear reactors and machinery (HS code 84) $6.54 billion (9.29%)

Commodities not elsewhere specified (HS code 99) $5.93 billion (8.42%)

Plastics and articles thereof (HS code 39) $2.86 billion (4.06%)

Pharmaceutical products (HS code 30) $2.43 billion (3.45%)

Optical, medical, or surgical instruments (HS code 90) $1.73 billion (2.46%)

Iron and steel (HS code 72) $1.48 billion (2.11%)

Aircraft, spacecraft, and parts thereof (HS code 88) $1.46 billion (2.06%)

Ukraine Exports Overview

On the export side, Ukraine is known for its agricultural products, energy resources, and industrial goods. Some of the top exports of Ukraine include:

Grains and Oilseeds: Ukraine is one of the world's top producers of grains and oilseeds, such as wheat, corn, and sunflower seeds. These products are in high demand globally for food and feed purposes.

Steel and Metal Products: Ukraine's steel industry is a major player in the global market, with the country exporting a large quantity of steel and metal products to various countries.

Energy Resources: Ukraine is rich in natural resources, including coal, natural gas, and oil. The country exports these energy resources to neighboring countries and beyond.

Chemicals and Pharmaceuticals: Ukraine also exports chemicals and pharmaceuticals, including fertilizers, medicines, and plastics. These products are in demand worldwide for various industries.

Top 10 Ukraine Exports: Ukraine Export Data by HS Code (2024)

In analyzing the top 10 Ukraine exports through the Ukraine Export Data by HS Code, a clear picture emerges of the country's key economic drivers. With a professional focus, these data reveal Ukraine's significant export strengths across various industries. From cereals and iron ores to machinery and electrical equipment, the export data showcases the diversification and competitiveness of Ukraine's export sector. The top 10 goods that Ukraine exports, as per Ukraine shipment data and Ukraine export statistics for 2024, include:

Cereals (HS code 10): $8.30 billion (22.96%)

Animal or vegetable fats and oils (HS code 15): $5.64 billion (15.61%)

Oil seeds and oleaginous fruits (HS code 12): $2.81 billion (7.79%)

Iron and steel (HS code 72): $2.64 billion (7.32%)

Ores, slag, and ash (HS code 12): $1.87 billion (5.17%)

Electrical machinery and equipment (HS code 85): $1.66 billion (4.6%)

Wood and articles of wood (HS code 44): $1.48 billion (4.11%)

Prepared animal food (HS code 23): $1.39 billion (3.86%)

Nuclear reactors and machinery (HS code 84): $957.15 million (2.65%)

Meat and edible meat offal (HS code 02): $892.29 million (2.47%)

Final Outlook

By acquiring Ukraine Import Data and Ukraine Export Data, businesses can gain valuable insights into the country's trade patterns and identify potential opportunities for growth and expansion. Whether you are looking to import goods into Ukraine or export products from the country, having access to reliable Ukraine trade data is essential for making informed decisions.

Conclusion

In conclusion, Ukraine plays a significant role in the global trade market, both as an importer and exporter. By exploring the top imports and exports of Ukraine with the help of Ukraine Import Data and Ukraine Export Data, businesses can unlock new possibilities and tap into the country's vibrant economy.

0 notes

Text

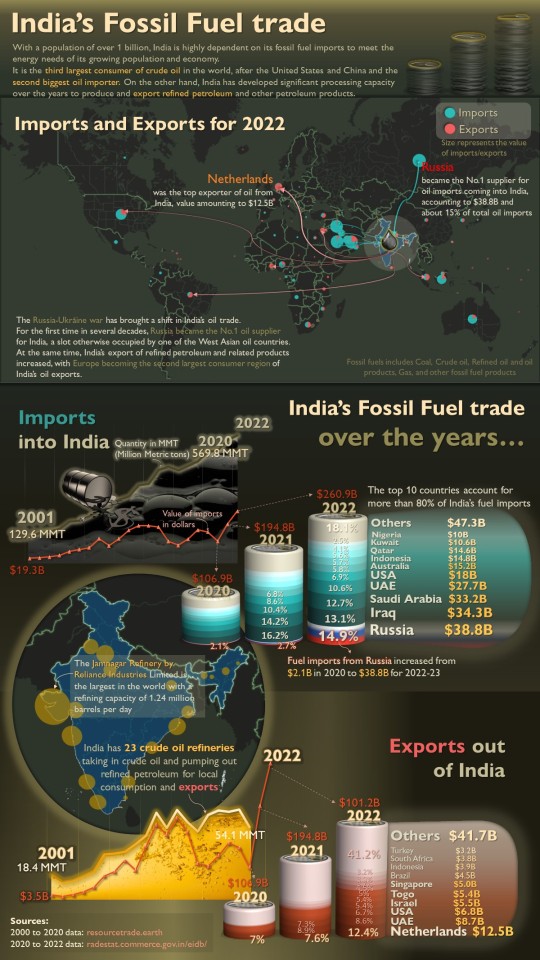

The Russia-Ukraine war and the ensuing oil embargos have been in the news for long now. The impact of this on India's oil trade and the corresponding trade figures are depicted here...

Data sources used: 2000 to 2020 data: https://resourcetrade.earth/ 2020 to 2022 data: https://tradestat.commerce.gov.in/eidb/

#data visualization#dataviz#russia ukraine war#oil and gas#oil trading#import export data#india#fossil fuels

1 note

·

View note

Text

MYKOLAIV, UKRAINE—Kateryna Nahorna is getting ready to find trouble.

Part of an all-female team of dog handlers, the 22-year-old is training Ukraine’s technical survey dogs—Belgian Malinois that have learned to sniff out explosives.

The job is huge. Ukraine is now estimated to be the most heavily mined country on Earth. Deminers must survey every area that saw sustained fighting for unexploded mines, missiles, artillery shells, bombs, and a host of other ordnance—almost 25 percent of the country, according to government estimates.

The dogs can cover 1,500 square meters a day. In contrast, human deminers cover 10 square meters a day on average—by quickly narrowing down the areas that manual deminers will need to tackle, the dogs save valuable time.

“This job allows me to be a warrior for my country … but without having to kill anyone,” said Nahorna. “Our men protect us at war, and we do this to protect them at home.”

A highly practical reason drove the women’s recruitment. The specialized dog training was done in Cambodia, by the nonprofit Apopo, and military-aged men are currently not allowed to leave Ukraine.

War has shaken up gender dynamics in the Ukrainian economy, with women taking up jobs traditionally held by men, such as driving trucks or welding. Now, as mobilization ramps up once more, women are becoming increasingly important in roles that are critical for national security.

In Mykolaiv, in the industrial east, Nahorna and her dogs will soon take on one of the biggest targets of Russia’s military strategy when they start to demine the country’s energy infrastructure. Here, women have been stepping in to work in large numbers in steel mills, factories, and railways serving the front line.

It’s a big shift for Ukraine. Before the war, only 48 percent of women over age 15 took part in the workforce — one of the lowest rates in Europe. War has made collecting data on the gender composition of the workforce impossible, but today, 50,000 women serve in the Ukrainian army, compared to 30,000 before the war.

The catalyst came in 2017, years before the current war began. As conflict escalated with Russia in Crimea, the Ukrainian government overturned a Soviet-era law that had previously banned women from 450 occupations.

But obstacles still remain; for example, women are not allowed jobs the government deems too physically demanding. These barriers continue to be chipped away��most recently, women have been cleared to work in underground mines, something they were prevented from doing before.

Viktoriia Avramchuk never thought she would follow her father and husband into the coal mines for DTEK, Ukraine’s largest private energy company.

Her lifelong fear of elevators was a big factor—but there was also the fact that it was illegal for women to work underground.

Her previous job working as a nanny in a local kindergarten disappeared overnight when schools were forced to close at the beginning of the war. After a year of being unemployed, she found that she had few other options.

“I would never have taken the job if I could have afforded not to,” Avramchuk said from her home in Pokrovsk. “But I also wanted to do something to help secure victory, and this was needed.”

The demining work that Nahorna does is urgent in part because more than 55 percent of the country is farmed.

Often called “the breadbasket of Europe,” Ukraine is one of the world’s top exporters of grain. The U.K.-based Tony Blair Institute for Global Change, which has been advising the Ukrainian government on demining technology, estimates that landmines have resulted in annual GDP losses of $11 billion.

“Farmers feel the pressure to plow, which is dangerous,” said Jon Cunliffe, the Ukraine country director of Mines Advisory Group (MAG), a British nonprofit. “So we need to do as much surveying as possible to reduce the size of the possible contamination.”

The dogs can quickly clear an area of heavy vegetation, which greatly speeds up the process of releasing noncontaminated lands back to farmers. If the area is found to be unsafe, human deminers step in to clear the field manually.

“I’m not brave enough to be on the front line,” 29-year-old Iryna Manzevyta said as she slowly and diligently hovered a metal detector over a patch of farmland. “But I had to do something to help, and this seemed like a good alternative to make a difference.”

Groups like MAG are increasingly targeting women. With skilled male deminers regularly being picked up by military recruiters, recruiting women reduces the chances that expensive and time-consuming training will be invested in people who could be drafted to the front line at a moment’s notice. The demining work is expected to take decades, and women, unlike men, cannot be conscripted in Ukraine.

This urgency to recruit women is accelerating a gender shift already underway in the demining sector. Organizations like MAG have looked to recruit women as a way to empower them in local communities. Demining was once a heavily male-dominated sector, but women now make up 30 percent of workers in Vietnam and Colombia, around 40 percent in Cambodia, and more than 50 percent in Myanmar.

In Ukraine, the idea is to make demining an enterprise with “very little expat footprint,” and Cunliffe said that will only be possible by recruiting more women.

“We should not be here in 10 years. Not like in Iraq or South Sudan, where we have been for 30 years, or Vietnam, or Laos,” Cunliffe said. “It’s common sense that we bring in as many women as we can to do that. In five to 10 years, a lot of these women are going to end up being technical field managers, the jobs that are currently being done by old former British military guys, and it will change the face of demining worldwide because they can take those skills across the world.”

Manzevyta is one of the many women whose new job has turned her family dynamics on their head. She has handed over her previous life, running a small online beauty retail site, to her husband, who—though he gripes—stays at home while she is out demining.

“Life is completely different now,” she said, giggling. “I had to teach him how to use the washing machine, which settings to use, everything around the house because I’m mostly absent now.”

More seriously, Manzevyta said that the war has likely changed many women’s career trajectories.

“I can’t imagine people who have done work like this going back and working as florists once the war is over,” she laughed.

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

𝐓𝐫𝐮𝐦𝐩’𝐬 𝐛𝐚𝐜𝐤 𝐢𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐬𝐚𝐝𝐝𝐥𝐞, 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐰𝐨𝐫𝐥𝐝’𝐬 𝐬𝐡𝐢𝐟𝐭𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐠𝐞𝐚𝐫𝐬—𝐟𝐚𝐬𝐭.

Take the EU: pre-Trump 2.0, they were coasting at €235 billion on defense in 2024—barely 1.6% of GDP, per the European Defence Agency.

Now?

Ursula von der Leyen’s ‘ReArm Europe’ plan’s jacking it up by $840 billion over four years—think €650 billion from national budgets, €150 billion in joint borrowing.

Why?

Because Trump’s Ukraine aid freeze and NATO tough talk (5% GDP or bust) lit a fire under them. Poland’s gone from €12 billion in 2014 to €31.6 billion in 2023, now buying 1,000+ tanks; Germany’s adding €60 billion to hit 3.5% GDP. That’s Trump’s genius—making allies pay up, not us.

~~~~~~

Domestically, he’s unleashing chaos on the swamp.

Deregulation’s got oil flowing—Keystone XL’s back, and XLE’s up 8% since January.

Tax cuts are cooking—leaks say 15% corporate rates for manufacturers, with Ford eyeing 2,000 new jobs in Michigan.

Border’s tighter—Border Patrol nabbed 30% fewer crossings in February after his wall push resumed.

Ohio steel’s roaring too—tariffs slashed Chinese imports by 25%, per early trade data.

~~~~~~~~

Globally, he’s rewriting the playbook.

Abraham Accords 2.0—Saudi’s joining Israel’s handshake, with $10 billion in deals inked. Iran’s oil exports? Down 40% since January sanctions hit—Tehran’s squealing.

Ukraine’s Zelensky’s on the ropes—Trump’s peace-or-bust ultimatum could end that war in some foreseeable future, when previously there was no end in sight.

𝐅𝐮𝐭𝐮𝐫𝐞’𝐬 𝐛𝐫𝐢𝐠𝐡𝐭: EU’s cash dump means we’re not footing their bill—$100 billion less U.S. aid projected by 2026.

Domestic GDP’s set to jump 3% with tax breaks and energy.

Globally, Trump’s forcing strength—NATO’s waking up, Middle East’s aligning, adversaries are scrambling. The man’s a bulldozer—2025’s his runway.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

The European Commission (EC) is reviewing legal mechanisms that would allow European energy companies to exit long-term contracts with Russian suppliers without incurring significant financial penalties. According to three EU officials cited by the Financial Times, the Commission is investigating whether the contracts could be invalidated under “force majeure” provisions—typically used when unforeseen circumstances prevent the fulfillment of contractual obligations.

One official emphasized that compensating Russia would defeat the broader EU objective of financially isolating Moscow. The initiative is part of the EU’s broader roadmap to eliminate reliance on Russian fossil fuels by 2027. Although pipeline gas from Russia has dropped to just 11% of total EU imports—down from nearly 40% in 2022—Russian liquefied natural gas (LNG) imports have surged over the past three years.

The Commission has not formally commented on the report. However, the effort to terminate gas contracts is unfolding at a sensitive time, as the EU seeks to reach an energy agreement with the United States in response to President Donald Trump’s tariff policies. The U.S., already the EU’s top LNG supplier, is seen as a logical alternative should Russian energy imports be further reduced.

According to data from the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air, the EU paid Russia €21.9 billion for oil and gas between February 2024 and February 2025. While coal imports from Russia have been banned, and 90% of oil imports are under embargo, natural gas imports remain unrestricted. Still, overall Russian gas deliveries to the EU are at their lowest levels since 2022, despite a 60% rise in LNG imports since then.

The release of the EU’s energy roadmap, initially scheduled for March, has been delayed by internal disputes. Key concerns include the risk of opposition from Hungary and Slovakia, both of which still depend heavily on Russian pipeline gas. Hungary’s government has openly opposed gas sanctions, which require unanimous support from all 27 EU member states.

Further delays stemmed from renewed discussions around the future of the Nord Stream pipeline between Germany and Russia, and from ongoing negotiations with the U.S. regarding a broader energy and trade deal. A European diplomat described the situation as “a mess,” questioning how the EU plans to diversify energy sources amid geopolitical uncertainty.

Despite calls from Brussels to scale back Russian LNG imports, many EU member states are reluctant to compel companies to terminate existing agreements due to fears of market instability and rising energy costs. Although the Commission has granted member states the authority to restrict Russian and Belarusian access to port infrastructure and pipelines, these measures fall short of providing a clear legal route to annul contracts.

The challenge for EU lawyers is the secrecy and variability of energy contracts. Invoking the war in Ukraine as a justification for “force majeure” may not hold up legally, an EU official cautioned. French, Spanish, and Belgian ports remain key entry points for Russian LNG, much of it originating from the Yamal LNG plant, which has ongoing deals with major energy firms such as Shell and Naturgy.

Meanwhile, the Brussels-based think tank Bruegel has argued in favor of imposing tariffs on Russian gas rather than implementing a full ban. Such a move would require only a majority vote among EU countries and could generate revenue while pressuring Russian exporters to lower prices. Bruegel warned that without a unified EU approach, Russia could exploit energy divisions among member states by offering selective gas supplies.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

News of the Week 2/10/25

DEI, Race and Gender

Anti-Trans Shenanigans:

Trump signs EO banning trans athletes from women sports (prior EO only affected school teams).

He also vows to deny visas to trans athletes looking to compete in women's Olympics events (RP).

NCAA bans trans athletes from competing.

The Advocate discusses the science on whether trans women really have a physical advantage over cis women in sports. (12ft.io)

ACLU is suing Trump admin over passports misgendering trans people or not being processed.

Three states sue Trump admin over denying gender-affirming care to minors. (RP)

Racist Shenanigans & DEI:

The non-white workers who welcome Trump's pushback against DEI. (RP)

The racist undercurrents in Trump's anti-DEI pushback. (RP)

A history of DEI initiatives in America.

Foreign Relations

Gaza:

Jeremy Bowen argues, Trump's Gaza plan won't happen but it will disrupt commitment to a two-state solution and embolden Israel's Far Right.

Arab leaders reject Trump's Gaza plan, won't normalize relations with Israel without a two-state solution (RP)

Experts say it would also violate international law. (RP)

A history of Gaza's role in the Middle East conflict.

The reaction from Dearborn.

A journalist from the Gaza Strip discusses how Trump doesn't understand Palestinians. (RP)

Iran: US issues sanctions against shipping network moving oil from Iran to China.

Russia:

Bondi ended a law enforcement group addressing foreign influences in American elections (RP), which Trump thought had opposed him unfairly.

Trump admin shut down Task Force KleptoCapture, a Biden-era push to seize assets from Russian oligarchs in response to Russia's war against Ukraine.

Canada: Trudeau claims Trump is serious about wanting to acquire Canada.

Tariffs:

Trump announces reciprocal tariffs on all foreign nations. (RP)

Essentially this means if a country charges a 5% tariff against American imports, we'd also charge an 5% tariff on their exports to us.

Trump also delayed imposing tariffs on low-value shipments from China (shipments valued <$800 USD).

Separately, Trump promises to impose 25% tariffs on steel and aluminum. (RP) Stocks fell in response. (RP)

Autocracy

Elon Musk:

DOGE was granted access to Medicaid and Medicare (RP), Social Security (12ft.io) payment systems, Veterans' sensitive data (RP).

A federal judge temporarily blocked DoGE's accessing the Treasury Department's data (RP), though his scathing response to the judge makes one doubt how thoroughly he'll comply. Musk has now called for the judge who blocked his access to be impeached. (RP)

Democrat lawmakers are also requesting a Treasury Dept. investigation on why DoGE was given access to their system

Federal employees are suing Treasury, claiming Musk received illegal access to their information (RP).

Why Musk was so interested in the Bureau of the Fiscal Services, America's 'Checkbook' (RP).

How Elon Musk's past mass firings at Twitter impacted the company. (RP)

Religion:

Trump spoke at the National Prayer Breakfast. (VIDEO)

He pledged to investigate anti-Christian bias and that AG Bondi would "fully prosecute anti-Christian violence and vandalism."

The executive order on anti-Christian bias was issued. (RP)

He will order a task-force to "eradicate anti-Christian bias. (RP)

Attacks on Journalism:

Trump calls for "termination" of 60 minutes after they release transcript of Kamala Harris interview.

Steve Benen (MSNBC) argues Trump is misinterpreting the transcript. (RP)

Several major mainstream media outlets submit to Trump.

On the "novel" legal theory Trump is using to go after news outlets. (RP)

Mass Firings of Federal Workers

Details on Musk's deferred resignation "buyout" (RP)

So far, 40,000 employees have accepted the offer. (RP) Only 2% of federal workers, but hard to imagine it won't affect services.

A past federal employee about life after resigning. (RP)

Judge prevents Trump admin from putting USAID workers on administrative leave.

EPA puts staffers who worked on environmental justice on leave.

Trump takes steps to fire Federal Election Commission member.

Trump dismisses several board members of Kennedy Center, appoints himself as Chair.

Many nonprofits still unable to access funding. Those that can discuss how the uncertainty affects their work. (RP)

Immigration

Mass Deportations:

DOJ sues Chicago & Illinois over sanctuary city policies.

US begins construction of tent city to house immigrant detainees at Guantanamo Bay. (RP)

DHS head Noem says non-violent immigrants could be held there. (RP) Initially Guantanamo was only supposed to be for violent criminal migrants.

Other Stories

Pam Bondi

She was confirmed and sworn in as attorney general. (12ft.io)

She issued fourteen memorandums (RP). Of note, several involve "re-investigating" the anti-Trump investigations and lifting the federal moratorium on the death penalty.

She also ordered DoJ to stop all funding to sanctuary cities. (RP)

Department of Education

Trump admin is drafting an EO to dismantle the Department of Education. (RP)

Eliminating the Department of Education, like any true department, would require an act of Congress.

What the Department of Education does (and doesn't do).

Gun Regulation: Trump orders review of federal gun revolutions, with goal of undoing Biden-era regulations. (12ft.io)

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

An investigation by Ukrainska Pravda (UP) has found that Russian oil continues to flow into the EU despite sanctions, with shipments under the flags of Liberia and Panama reaching the ports of Romania and Bulgaria, both EU and NATO members. Nearly three years on from Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Western sanctions designed to weaken the Russian economy have failed to halt its oil exports. Despite sanctions on Russian oil, the EU paid approximately €140 billion for oil and gas in 2022, including €80 billion for oil, according to the Financial Times. This financial support has enabled Russia to continue funding its military aggression against Ukraine. Russia's oil revenues are a key source of funding for its war operations, with military spending projected to rise to US$142 billion by 2025. "We’ll have a full import ban on Russian seaborne oil," European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen declared in May 2022, just two months after Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Yet an investigation by Ukrainska Pravda journalist Mykhailo Tkach, who was on the ground in Romania and later Bulgaria to witness shipments arriving first-hand, has revealed that Russian oil was still reaching EU ports in November 2024. Using data from MarineTraffic, a global platform providing real-time information on ship movements, Ukrainska Pravda tracked two Russian oil tankers as they arrived in EU countries. On 8 and 9 November 2024, the Lipari (Liberia-flagged) and Sredina (Panama-flagged) tankers, carrying 160,000 tonnes of light crude oil, docked at EU ports after departing from the Russian port of Novorossiysk. The Russian oil reached the EU on 10 November 2024, a day on which Russia’s attacks on Ukraine went on for over 15 hours.

continue reading

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bacardi is paying taxes to Putin which help him buy missiles to blow up maternity hospitals, schools, and apartment buildings in Ukraine.

If Bacardi can't quit Vladimir, pro-democracy people should quit Bacardi.

Ukraine’s national anti-corruption agency added Bacardi Limited to its list of international war sponsors, citing the company’s continued business and tax payments in Russia. In its announcement Thursday, Ukraine’s National Agency on Corruption Prevention (NACP) claimed the Bermudian spirits company is looking for new employees in Russia, despite Ukraine’s ongoing conflict with the country. “After the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine, Bacardi announced that it would stop exporting to Russia and stop investing in advertising, but this part later disappeared from the company’s official statement,” according to a statement from the NACP. “Therefore, the company continued to supply its products to the Russian Federation for millions of dollars and to look for new employees by publishing job advertisements.”

Bacardi has engaged in rather sketchy bookkeeping to hide its involvement in Russia. But they were inadvertently outed by Russia itself.

The NACP claimed the Russian division of the Bacardi Rus company “imported goods worth $169 million during the year of war with Ukraine.” The agency cited data from the Federal Tax Service of the Russian Federation, which it said showed the revenue of Bacardi Rus in 2022 increased by 8.5 percent to 32.6 billion rubles and had a net profit of 4.7 billion rubles, which is 206.5 percent more than its profit in 2021. The NACP said the company paid more than $12 million in income taxes to Russia.

Both Yale University School of Management and the Kyiv School of Economics maintain databases on involvement of foreign businesses in Russia.

They are somewhat similar but not identical. The KSE database covers twice as many companies as Yale. Yale uses five categories; the KSE uses six categories in the heading but then telescopes the four middle categories into two beneath the fold. The KSE offers more detailed information on each company. The latter also has a version in Ukrainian. Yale offers a continuous scroll running from worst to best grouping. At KSE you click one of the categories and are then shown the company profiles in groups of 120 or less. Both sites were updated on Thursday.

Over 1,000 Companies Have Curtailed Operations in Russia—But Some Remain | Yale School of Management (Yale)

Stop Doing Business With Russia (KSE)

Many of the listings are for consumer products companies. So the databases are worth a browse before the next time you shop. Support the good guys and take a pass on the bad guys.

#invasion of ukraine#sponsors of putin's war#bacardi#bacardi rus#companies still doing business with russia#boycott companies doing business in russia#nazk#nacp ukraine#national agency on corruption prevention#yale university school of management#kyiv school of economics#агрессивная война россии#спонсоры войны#бакарди рус#владимир путин#путин хуйло#союз постсоветских клептократических ватников#геть з україни#вторгнення оркостану в україну#україна переможе#національне агентство з питань запобігання корупції#київська школа економіки#деокупація#слава україні!#героям слава!

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Beginner’s Guide to Registering Chemicals in Ukraine

As Ukraine strengthens its alignment with EU standards, its Technical Regulation on Chemical Safety—often referred to as Ukraine REACH—has emerged as a critical framework for companies importing or manufacturing chemicals in the country. Whether you’re a global supplier or a local distributor, understanding how to register chemicals under this regulation is essential to maintain market access and compliance.

This guide breaks down the basics of the chemical registration process in Ukraine and how GPC Regulatory, a leading chemical regulatory consultant, supports businesses through seamless compliance solutions.

What Is Ukraine REACH?

Ukraine's chemical regulation mirrors the European Union’s REACH (Registration, Evaluation, Authorization, and Restriction of Chemicals) regulation. It requires companies to provide detailed information on chemical substances, including their properties, uses, and safety measures.

The regulation applies to:

Manufacturers and importers of chemical substances

Distributors of mixtures and articles

Non-Ukrainian companies via an Authorized Representative (AR)

Key Steps in Ukraine REACH Registration

Identify Obligations

Determine whether your chemical substance falls under the scope of the regulation.

Establish your role in the supply chain (manufacturer, importer, or downstream user).

Compile Substance Information

Collect data on physicochemical, toxicological, and ecotoxicological properties.

Prepare safety data sheets (SDS) and technical dossiers.

Submit Pre-Registration or Registration

Submit to the Ukrainian competent authority with necessary documentation.

Include classification and labelling details based on GHS/CLP.

Work with an Authorized Representative

Non-resident companies must appoint a Ukrainian-based AR to manage registration and communication with local authorities.

Challenges You Might Face

Language Barriers: Technical documents often need to be translated into Ukrainian. Regulatory Updates: The regulation is evolving and may align more closely with EU REACH over time. Data Gaps: Acquiring valid testing data or sharing data through consortia can be complex.

How GPC Regulatory Supports You

As a trusted chemical regulatory consultant, GPC Regulatory simplifies compliance with Ukraine’s chemical laws. We provide end-to-end support, from regulatory analysis to successful registration.

Our Ukraine REACH registration services include:

Substance inventory and data gap analysis

Preparation and submission of registration dossiers

Authorized Representative (AR) services in Ukraine

Ongoing compliance monitoring and updates

Multilingual support and document translation

We ensure your company stays compliant, competitive, and confident in the Ukrainian market—without navigating the legal maze alone.

Why Choose GPC Regulatory?

Experienced consultants with deep knowledge of global REACH-like systems

Tailored solutions for SMEs, large enterprises, and exporters

Proven track record of helping companies enter and expand in regulated markets

0 notes

Text

Eximpedia, which provides exclusive access to Ukraine import export data, can help you advance your company plan. Gain a competitive edge in the dynamic market by leveraging our comprehensive data solutions, ensuring informed decisions and successful navigation of the Ukrainian trade landscape.

0 notes

Text

Discover the major exports of Ukraine and its key export partners with Seair Exim Solutions. Gain insights into Ukraine's export market, trade statistics, and economic impact.

#exports of Ukraine#major export of Ukraine#hs code ukraine#Ukraine export products#Ukraine trade data#Ukraine export data#main export of Ukraine#ukraine top exports#Ukraine biggest export#Ukraine export by country#ukraine import export data

0 notes

Text

Cumene Price Index: Market Analysis, Trend, News, Graph and Demand

Cumene, a vital petrochemical used predominantly as a precursor in the production of phenol and acetone, has witnessed fluctuating prices over the past year due to a complex interplay of global economic factors, supply chain constraints, and changing demand dynamics. As of 2025, the cumene market remains highly sensitive to variations in crude oil prices, given that cumene is produced via the alkylation of benzene with propylene, both of which are derivatives of oil and gas. When crude oil prices soar, the cost of benzene and propylene also tends to rise, leading to upward pressure on cumene prices. Conversely, any slump in oil prices can ease input costs, thus affecting cumene prices accordingly.

The global market for cumene has been influenced by significant geopolitical developments and energy market shifts. In 2024, disruptions in oil-producing regions, coupled with the residual impact of the Russia-Ukraine conflict and tensions in the Middle East, led to unpredictable fluctuations in feedstock availability. This volatility trickled down to the cumene market, causing price surges at multiple points. Additionally, logistical challenges, including port congestion, container shortages, and increased freight costs, also played a role in inflating cumene prices in key export and import regions, especially in Asia and Europe.

In Asia, particularly in China and India, cumene prices have been relatively firm due to steady demand from downstream phenol and acetone sectors. These derivatives are integral to the production of bisphenol-A (BPA), polycarbonate, and epoxy resins, which are extensively used in automotive, construction, and electronics industries. With industrial output recovering in many Asian economies post-pandemic, the demand for these end-use products has grown, consequently pushing up the consumption and prices of cumene. However, regulatory measures around environmental compliance and emission control in some Chinese provinces have temporarily disrupted production, tightening regional supply and contributing to short-term price hikes.

Get Real time Prices for Cumene: https://www.chemanalyst.com/Pricing-data/cumene-1091

In the European market, cumene prices have been more volatile due to a combination of energy cost pressures and fluctuating demand from the phenol sector. Europe’s heavy dependence on natural gas, especially from external suppliers, exposed the region to high energy costs, which, in turn, raised the production costs for cumene. Moreover, phenol producers have occasionally scaled back operations in response to subdued downstream demand, creating inconsistency in feedstock procurement and contributing to a less stable pricing environment for cumene. Seasonal slowdowns and maintenance turnarounds in Europe’s petrochemical facilities have further compounded the issue, periodically tightening supply and resulting in temporary price spikes.

North America has shown a relatively more balanced cumene market over the past year. Strong domestic production capacity, access to competitively priced shale-based feedstocks, and steady demand from the packaging and electronics sectors have supported a stable pricing environment. However, weather-related disruptions, such as hurricanes in the Gulf Coast region, occasionally impact plant operations and logistics, causing short-term price volatility. The growing emphasis on sustainability and recycling in the U.S. market may influence the cumene supply-demand balance over the longer term, as industry stakeholders adapt to changing consumer and regulatory expectations.

Globally, the cumene market remains highly competitive, with price differentials often reflecting regional supply-demand imbalances, currency fluctuations, and trade tariffs. Exporters from regions with cost advantages, such as the Middle East and certain Southeast Asian countries, continue to influence global pricing trends through competitive offers in the international market. However, shifts in trade policies, such as anti-dumping duties or changes in import-export regulations, can affect pricing dynamics and market access for cumene across borders.

From a forecast perspective, cumene prices in 2025 are expected to remain moderately volatile, reflecting both upstream and downstream market conditions. Any significant increase in phenol and acetone demand, especially driven by the electric vehicle (EV) and renewable energy sectors, could spur a corresponding rise in cumene demand and prices. Additionally, innovation in lightweight materials, automotive composites, and flame-retardant plastics—many of which rely on cumene-derived intermediates—will likely sustain a positive long-term outlook for the market.

Environmental regulations and the global shift toward carbon neutrality may introduce new challenges and opportunities for the cumene industry. On one hand, stricter emissions standards could raise compliance costs for manufacturers, potentially pushing up cumene prices. On the other hand, improvements in process efficiency, recycling of downstream products, and the integration of bio-based feedstocks might offer cost advantages in the longer run. Investment in green chemistry and circular economy practices may gradually influence the supply chain and pricing structure of cumene as industries strive to balance economic and environmental priorities.

In conclusion, cumene prices are shaped by a dynamic mix of raw material trends, regional market activities, global trade flows, and end-user demand. Market participants must remain agile, closely monitoring crude oil prices, regulatory developments, and demand trends in phenol and acetone industries to navigate pricing challenges. As global industries evolve toward more sustainable and technologically advanced operations, the cumene market will continue to adapt, offering both risks and opportunities for suppliers, traders, and downstream manufacturers alike.

Get Real time Prices for Cumene: https://www.chemanalyst.com/Pricing-data/cumene-1091

Contact Us:

ChemAnalyst

GmbH - S-01, 2.floor, Subbelrather Straße,

15a Cologne, 50823, Germany

Call: +49-221-6505-8833

Email: [email protected]

Website: https://www.chemanalyst.com

#Cumene Price#Cumene Prices#Cumene Pricing#Cumene News#Cumene Price Monitor#India#United kingdom#United states#Germany#Business#Research#Chemicals#Technology#Market Research#Canada#Japan#China

0 notes

Text

Now that Donald Trump is returning to a second term as U.S. president, ascertaining the true state of Russia’s war economy is more important than ever. Trump’s advisors believe that Ukraine must settle for peace by whatever means necessary “to stop the killing.” Implicit in this argument is the view that Russia has the ability to sustain the war for many years to come. On close examination of the evidence, however, the narrative that Russia has the resources to prevail if it so chooses does not hold.

The apparent resilience of the Russian economy has confounded many strategists who expected Western sanctions to paralyze Moscow’s war effort against Ukraine. Russia continues to export vast quantities of oil, gas, and other commodities—the result of sanctions evasion and loopholes deliberately designed by Western policymakers to keep Russian resources on world markets. So far, clever macroeconomic management, particularly by Russian Central Bank Governor Elvira Nabiullina, has enabled the Kremlin to keep the Russian financial system in relative health.

At first glance, the numbers look surprisingly strong. In 2023, GDP grew by 3.6 percent and is expected to rise by 3.9 percent in 2024. Unemployment has fallen from around 4.4 percent before the war to 2.4 percent in September. Moscow has expanded its armed forces and defense production, adding more than 500,000 workers to the defense industry, approximately 180,000 to the armed forces, and many thousands more to paramilitary and private military organizations. Russia has reportedly tripled its production of artillery shells to 3 million per year and is manufacturing glide bombs and drones at scale.

Despite these accomplishments, Russia’s war economy is heading toward an impasse. Signs that the official data masks severe economic strains brought on by both war and sanctions have become increasingly apparent. No matter how many workers it tries to shift to the defense industry, the Kremlin cannot expand production fast enough to replace weapons at the rate they are being lost on the battlefield. Already, about around half of all artillery shells used by Russia in Ukraine are from North Korean stocks. At some point in the second half of 2025, Russia will face severe shortages in several categories of weapons.

Perhaps foremost among Russia’s arms bottlenecks is its inability to replace large-caliber cannons. According to open-source researchers using video documentation, Russia has been losing more than 100 tanks and roughly 220 artillery pieces per month on average. Producing tank and artillery barrels requires rotary forges—massive pieces of engineering weighing 20 to 30 tons each—that can each produce only about 10 barrels a month. Russia only possesses two such forges.

In other words, Russia is losing around 320 tank and artillery cannon barrels a month and producing only 20. The Russian engineering industry lacks the skills to build rotary forges; in fact, the world market is dominated by a single Austrian company, GFM. Russia is unlikely to acquire more forges and increase its production rate, and neither North Korea nor Iran have significant stockpiles of suitable replacement barrels. Only a decision by China to provide barrels from its own stockpiles could stave off Russia’s barrel crisis.

To resupply its forces, Russia has been stripping tank and artillery barrels from the vast stockpiles it inherited from the Soviet Union. But these stockpiles have withered since the start of the war. Combining current rates of battlefield loss, recycling from stockpiles, and production, Russia looks set to run out of cannon barrels some time in 2025.

Russia is consuming other weapons, too, at rates far faster than its ability to produce them. Open-source researchers have counted the loss of at least 4,955 infantry fighting vehicles since the war’s onset, which comes out to an average of 155 per month. Russian defense contractors can produce an estimated 200 per year, or about 17 per month, to offset these losses. Likewise, even Russia’s expanded production of 3 million artillery shells per year pales in comparison to the various estimates for current consumption at the front. While those estimates are lower than the 12 million rounds Russian forces fired in 2022, they are much higher than what Russian industry can produce.

We do not know when Russia will hit the end of the road with each equipment type. But there is little the Kremlin can do little to stave off that day. With the Russian economy essentially at full employment, Russian defense companies now struggle to attract workers. To make matters worse, these companies are competing for the same personnel as the Russian armed forces, which need to recruit 30,000 fresh troops each month to replace casualties. To this end, the military is offering lavish signing bonuses and greatly increased pay. Defense producers, in turn, have had to increase wages fivefold, contributing to an inflation rate that reached 8.68 percent in October.

Paradoxically, the same factors that are converging to restrict Russia’s ability to wage war also mean that it cannot easily make peace.

Russia’s economic performance—marked by low unemployment and rising wages—is a product of military Keynesianism. In other words: Vast military expenditures, which are unsustainable in the long term, are artificially boosting employment and growth. Almost all the new jobs are related to the military and produce little of value to the civilian economy, where most sectors have great difficulty finding workers.

Defense spending has officially jumped to 7 percent of Russia’s GDP and is projected to consume more than 41 percent of the state budget next year. The true magnitude of military expenditures is significantly higher. Russia’s nearly 560,000 armed internal security troops, many of which have been deployed to occupied Ukraine, are funded outside the defense budget—as are the private military companies that have sprouted across Russia.

Paring back these massive defense expenditures, however, will inevitably produce an economic downturn. If the Kremlin draws down the armed forces to a sustainable level, large numbers of traumatized veterans and well-paid defense workers will find themselves redundant. The experience of other societies—in particular, European states after World War I—suggests that hordes of demobilized soldiers and jobless defense workers are a recipe for political instability.

The magnitude of the post-war Russian recession will be all the worse because Russia’s civilian economy—particularly small- and medium-sized firms—has shrunk due to the war. In a phenomenon familiar to economists, high defense expenditures have bid up salaries and attracted labor away from nondefense firms. The Russian Central Bank’s policy of raising interest rates, which currently stand at 21 percent, has made it much more difficult for nondefense companies to raise capital through loans. In post-war Russia, a shrunken civilian sector will not be able to absorb the soldiers and workers cast off by the military and defense sector.

Therefore, Russia’s leaders face an unenviable set of dilemmas entirely of their own making. Russia cannot continue waging the current war beyond late 2025, when it will begin running out of key weapons systems.

Concluding a peace agreement, however, poses a different set of problems, as the Kremlin needs to choose between three unpalatable options. If it draws down the armed forces and defense industries, it will spark a recession that could threaten the regime. If Russian policymakers instead maintain high levels of defense spending and a bloated peacetime military, it will asphyxiate the Russian economy, crowding out civilian industry, and stifle growth. Having experienced the Soviet Union’s decline and fall for similar economic reasons, Russian leaders will probably seek to avoid this fate.

A third option, however, is available and likely beguiling: Rather than demobilizing or bankrupting themselves, Russian leaders could instead use their military to obtain the economic resources needed to sustain it—in other words, using conquest and the threat thereof to pay for the military.

Plenty of precedents exist. In 1803, French Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte ended 14 months of peace in Europe because he could not afford to fund his military based on French revenues alone—and he also refused to demobilize it. In 1990, Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein similarly invaded oil-rich Kuwait because he could not afford to pay the million-man army that he refused to downsize. In both cases, the mirage of conquest seemed attractive for sustaining overly large defense establishments without having to pay for them.

Russia could likewise exploit its expanded military to extract rents from other states. Even though Russia is running out of key weapons systems for its all-out war on Ukraine, its forces will still be capable of punctual acts of aggression. Indeed, it’s easy to imagine how Russia might pursue such a policy.

Substantial offshore gas reserves have been discovered in the Black Sea within Ukraine’s and Georgia’s internationally recognized exclusive economic zones (EEZs). Whenever Western states are distracted by other priorities, Russia could also renew its aggression against Ukraine in order to gain control of its agricultural, gas, and rare-earth resources. Finally, Russia might use threats of force rather than actually fighting in order to coerce European states to withdraw sanctions, unfreeze Russian assets, or reopen gas and oil pipelines.

Some important lessons emerge. First, Russia’s economy cannot indefinitely sustain its war against Ukraine. Labor and production bottlenecks will condemn Russia to defeat as long as Ukraine’s allies sustain it beyond the second half of 2025. Contrary to the myth of infinite Russian resources, the Kremlin’s armies are far from unbeatable. But Russia’s defeat demands a level of Western patience and commitment that a combination of vacillating Western leaders and volatile domestic politics renders questionable.

Second, the cessation of full-scale fighting in Ukraine will not end the West’s problems with Russia. Russia’s supersized military sector incentivizes the Kremlin to use its military to extract rents from neighboring states. The alternatives—demobilizing and incurring a recession or indefinitely funding a bloated military and defense industry—pose existential threats to Putin’s regime.

However Russia ends its current war, the country’s economic realities alone will generate new forms of insecurity for Europe. Far-sighted policymakers should focus on mitigating these future threats, even as they focus on how the current round of fighting in Ukraine will end.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Price of Myths: How Neighbors Manipulate the Topic of Ukraine’s EU Accession

Ukraine continues its gradual path toward membership in the European Union, but this path is accompanied by resistance, myths, and fears propagated by politicians and citizens of certain member states. The most significant concern lies in the economic dimension: will Ukraine become a burden on the EU budget, or, conversely, will it open new opportunities for the development of the entire Union? In this article, we analyze where the narratives about Ukraine as a burden come from, who promotes them, and why Ukraine’s accession to the EU is an investment, not a loss.

Hungary

On March 20, 2025, Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán stated on his X page that Ukraine’s EU membership would cost each Hungarian household 500,000 forints (1,200 euros) annually:

“9,000 billion HUF – that’s how much the war has already cost Hungarian families. 500,000 HUF per household, every year – that’s the price tag of Ukraine’s EU membership. Brussels wants Hungarians to pay the bill, but no decision will be made without the voice of the Hungarian people. A new member can only join with the unanimous support from all Member States. There can be no decision until the Hungarian people cast their votes. This decision belongs to our citizens, not Brussels!”

Screenshot of the post

First of all, where does this data come from? These are calculations by the Századvég Foundation, a think tank affiliated with Orbán. According to the foundation, “Ukraine has cost each Hungarian household 2.2 million HUF” (5,500 euros) or 9,000 billion HUF (22.5 billion euros) in total. The basis for the supposed losses includes three components: rising prices for imported gas, increased state spending due to higher yields on government bonds, and losses from reduced exports to Russia.

In reality, it refers to increased prices for imported gas due to changes in spot prices at the TTF Gas Hub in the Netherlands and additional budget expenditures due to the higher cost of state debt (due to geopolitical risks and inflation shocks, the yield on 5-year Hungarian government bonds rose from 2% to 4–6%). Additionally, bilateral sanctions – imposed by the EU on Russia and by Russia on the EU – affected Hungary’s trade volumes with the aggressor state. However, the root cause of these losses – Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine – is not mentioned in the Századvég Foundation’s analysis.

Secondly, what does 500,000 HUF (1,250 euros) from each Hungarian household for Ukraine’s EU accession mean? In reality, Ukraine will not “take” money from every Hungarian family. It is more about potentially foregone aid from the EU budget that the country currently receives, and possible increased expenditures from Hungary’s state budget.

These calculations are based on the potential reduction in receipts from the EU Cohesion Fund and subsidies under the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), contributions to support Ukraine amounting to 0.25% of GDP, additional pension costs for Ukrainians who supposedly will move to Hungary, and estimates of Hungary’s share in financing Ukraine’s reconstruction.

In general, there are several issues with the 500,000 HUF figure:

They are based on the assumption that Ukraine would join the EU today. In reality, the years leading up to Ukraine’s EU integration will bring changes both in Ukraine (for example, we need to harmonize legislation with EU standards) and in the EU itself. By the time of Ukraine’s accession, both the CAP and the distribution of Cohesion Fund expenditures will likely have been significantly revised. Discussions on such revisions have already begun.

Reconstruction costs for Ukraine are a separate international initiative, not part of the EU accession process, and not solely the responsibility of member states. Therefore, treating them as “future losses” for the population related to Ukraine’s EU accession is unfounded and manipulative.

The calculations of migration and pension burdens are based on speculative assumptions. For example, the claim that 5% of Ukrainian pensioners will move to Hungary. According to the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, at the end of February 2025, the share of Ukrainians who chose Hungary as a refuge was about 1% of the total number of refugees in European countries.

Finally, the estimates by the Századvég Foundation do not consider the positive economic effects of enlargement: new markets, investments, enhanced security, and stability in the region. According to IMF calculations, EU enlargement, particularly due to the integration of Ukraine, Moldova, and the Balkan countries, could increase the bloc’s GDP by 14% over 15 years.

By the way, Hungary’s accession to the EU in 2004 also involved both pre-accession financial aid and post-accession funding to support its integration and development through three programs: ISPA (Instrument for Structural Policies for Pre-Accession), PHARE (Poland and Hungary: Aid for Restructuring of the Economies), and SAPARD (Special Accession Programme for Agriculture and Rural Development). Between 1990 and 2006, Hungary received €1.987 billion (in prices of that time). But even after joining, the country continued to receive support — financial aid for 2021–2027 is planned at around €30 billion.

Hungary receives several times more from the Cohesion Fund and other EU funds than it contributes to the EU budget. Its contribution is relatively small (about €2 billion with a GDP of more than €200 billion), while the amount received is one of the highest in the EU among recipient countries (after subtracting contributions, Hungary received around €4.5 billion from the EU budget in 2023). If calculated per capita, each Hungarian hypothetically gives “out of their pocket” about €200, while receiving nearly €700.

Poland and Slovakia

Concerns and myths about Ukraine’s accession to the European Union exist not only in Hungary. Polish presidential candidate from the opposition party Law and Justice (PiS), Karol Nawrocki, stated that Poland cannot afford actions that would harm its economy:

“At the same time, Poland represents — and I want this to be understood — its interests and society. Therefore, it cannot afford actions that would strike our economy, agriculture, or the wealth of Polish wallets.”

Russian propaganda media, citing Nawrocki’s interview for Sieci, picked up on the narrative that Ukraine’s EU membership would be economically disadvantageous for Poland.

Polish journalist and commentator Łukasz Warzecha pointed out that large amounts of money would go to Ukraine, which would be a direct competitor to Poland:

“Imagine this: in a few years, in a prospective new budget, Poles will have to pay not only gigantic sums due to the EU’s absurd climate policy, but will also be informed that tens of billions of euros of our money will flow into Ukraine, which will be our direct competitor in the bloc.”

In Slovakia, social media users circulated several false claims about the negative impact of Ukraine’s accession to the EU on the national economy. In particular, they manipulated the words of MP Ľubica Karvašová from the “Progressive Slovakia” party, who said that Slovak farmers would have to grow different products if Ukraine joins the EU. Social media users claimed the politician proposed that farmers grow camels and oranges. The post added that farmers would go bankrupt because Ukraine would supply products that Slovaks have “been growing for centuries”.

Slovak politician and deputy chair of the “Hungarian Alliance”, György Gyimesi, claims that under current rules, Cohesion Fund money is allocated to those member states where GNI (gross national income) per capita is below 90% of the EU average:

“Ukraine’s accession, considering its low level of development, would lower the EU’s average level of development overall. This would mean some current beneficiary countries would no longer be eligible for funding. At the same time, their actual level of development would remain unchanged, but those member states that stayed below the threshold would receive less money,” he wrote.

He also noted that if Ukraine joined the EU, supposedly 30% of all money allocated under the Common Agricultural Policy would go to Ukraine. Gyimesi concluded that if Ukraine joined the EU, it would become the largest beneficiary of the EU budget:

“If the EU wanted to raise the GDP of a completely destroyed Ukraine to the level of its weakest member, Bulgaria, according to calculations, it would cost each EU citizen €600,” the statement read.

A new formula for solidarity: transform, not compete It is precisely the allocation of funds from these programs – the European Structural and Investment Funds and within the CAP – that Ukraine’s Eastern European neighbors mainly refer to when discussing potential losses (or rather, forgone income) for their households.

For example, the Cohesion Fund supports EU member states with a Gross National Income (GNI) per capita below 90% of the EU-27 average to strengthen the EU’s economic, social, and territorial cohesion. Under the current 2021–2027 program, 15 out of 27 countries are eligible for funding (Bulgaria, Czechia, Estonia, Greece, Croatia, Cyprus, Latvia, Lithuania, Hungary, Malta, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, and Slovenia). And the allocation of funds within the CAP depends on the area of arable land and the number and size of farming households.

Currently, all EU spending estimates related to Ukraine’s accession are based on the “here-and-now” assumption, that is, they consider the country’s current economic status, relative population size, and the configuration of the current EU institutional system. Under these assumptions, the potential volumes of support are impressive. For instance, according to estimates of researchers from the German Economic Institute in Cologne, if Ukraine had been an EU member in 2023, it would have received €130–190 billion: €70–90 billion in agricultural aid and €50–90 billion under cohesion regional policy. EU estimates are similar – €186 billion.

A transformation of budget priorities always accompanies EU enlargement. However, these changes are not a burden but an investment in economic, social, and political stability across the continent. Even before new members join, the EU begins investing in their transformation: supporting reforms, strengthening institutions, and modernizing infrastructure.

The example of Croatia, which joined the Union in 2013, demonstrates the effectiveness of this approach. Between 2007 and 2013, it received €998 million under the Instrument for Pre-Accession Assistance (IPA). After accession, Croatia received €12.2 billion through the European Structural and Investment Funds (ESIF), of which €9.1 billion came from EU Cohesion Policy funds. Additionally, in 2014–2020, Croatia received €2.3 billion under the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) Rural Development Programme.

The EU assisted Croatia in building institutional capacity, focusing primarily on preparing government institutions to comply with EU legislation and meet necessary criteria. The main focus was accelerating reforms in key areas such as the judiciary, anti-corruption, public administration reform, public finances, economic restructuring, and the business environment.

This strengthened the Croatian economy and the EU single market, into which local businesses integrated, expanding production chains. Accordingly, trade volumes increased. Add to this the new labor force and strengthened EU influence in the region. Croatia’s EU accession became a signal to other Balkan countries about the possibility of integration, provided reforms are implemented.

Under current conditions, Ukraine could become a net recipient of aid. At the same time, European countries that currently receive support would lose it, since Ukraine has the lowest GNI per capita and a high share of arable land. To integrate current candidates (which, in addition to Ukraine, include Moldova, Balkan countries, and Georgia), the EU needs to improve the efficiency of resource allocation. The EU budget and structural funds should consider current country indicators, growth potential, strategic importance, and benefits to the entire European Union.

Scholars and experts believe that if the EU enacts institutional reform, the costs of adapting Ukraine will be lower. Moreover, the efficiency of Ukraine’s agricultural sector is underestimated, and thus, subsidies for Ukrainian farmers may be significantly lower than the cited estimates.

Support for less developed regions is not only a matter of solidarity but also a mechanism for developing the internal market: new consumers and producers, reduced migration pressure, and strengthened regional security. People stay to live and work at home while purchasing goods produced in other EU countries.

Ukraine will bring unique assets to the EU: digital transformation, military resilience, flexible institutions, and civic engagement. While some European countries are slowly adapting to changes, Ukraine is already acting as a transformation accelerator.

Yes, integration requires investment. But these are investments in a new market, new energy, and a more resilient European space. Ukraine is not a “beneficiary” but a partner capable of strengthening and renewing the European Union.

Photo: depositphotos.com/ua

0 notes