#What's a deviant sexuality? It depends on what the culture defines as normal

Text

Every ✌️🏳️🌈💖queer vocab as gaeilge 💖🏳️🌈✌️ infographic I see has like aerach, maybe ait, and then the same list of terms that were directly translated from English by USI in like 2016. Cowards. Tell me the slurs.

#There's a serious conversation to be had about how terms for queer experiences can't be clearly translated across cultural and linguistic#Boundaries. B/c like. How does each culture define gender transgression?#What's a deviant sexuality? It depends on what the culture defines as normal#And EXTREMELY IMPORTANTLY FOR PPL WRITING THESE VOCAB LISTS#just importing English terms makes it seem like queerness is foreign and like. That Ireland didn't have queers#Until the Brits told us what bisexual and transgender were#So while I understand ppls discomfort with inclusing slurs. Well. They're proof that we've always been here.#I'm infinitely interested in the fact that dyke I.e. pejorative term for lesbian is the same as the verb to complain#That at least one person I know got called 'pale/white boy' growing up. Like that was how kids would call each other gay insultingly#And that 'queer ' is best embodied by words meaning strange and crooked#I want to know what queer Irish speakers called themselves!! I want to know how they were understood by their communities#Even when it was negative !#I wanna know all the slurs and idioms and double entendres. Idc about leispiach#Unless! That was a term that was used! In that case i want to know the hows and wheres very badly pls!!!#queer tag#irish language#An ghaeilge#gaeilge#Irish shit#Gotta say trasinscneach is adorable tho :-) tras!

226 notes

·

View notes

Text

Alternative Sexualities

In today's evolving society, the concept of sexuality has expanded beyond traditional norms. Alternative sexualities, including but not limited to homosexuality, bisexuality, pan sexuality and asexuality, are gaining recognition and acceptance. This blog aims to reach inside the social analysis of alternative sexualities and explore the underlying factors, social attitudes and impact on individuals and communities.

It is essential to define and understand what we mean by alternative sexualities. Alternative sexualities incorporate sexual orientations and identities that stray from society’s assumed norm of heterosexuality. These sexualities embrace various desires, emotional connections, expression of attraction, and promote a more inclusive and accepting society.

The observation of alternative sexualities requires an awareness of cultural and historical context. The acceptance and understanding of alternative sexualities have varied across different societies and time periods. Ancient cultures, like the Romans and Greeks celebrated same-sex relationships with citizens and non-citizens, whereas many modern societies have typically stigmatized and criminalized non-heterosexual orientations. Society constructs and reinforces norms that control what is considered “deviant” or “normal”. In the book A Sociology of Sex and Sexuality by Gail Hawkes “A longer historical perspective may recognize that the fragility of the heterosexual hegemony, and the binary which is its supporting structure, depends as much on enabling human agency as it does on constraining structure." We can challenge the heteronormative assumptions by critically examining the norms and values in a society that often marginalize individuals with alternative sexualities.

There is an intersectionality structure which emphasizes how various aspects of an individual's identity such as gender, race, and class intersect with their sexual orientation. This analysis sheds light on the challenges faced by individuals of many marginalized identities. In the article Imitation and Gender Insubordination by Judith Bulter, she mentions her struggles with identity “I’m permanently troubled by my identity categories, consider them to be invariable stumbling-blocks, and understand them, even promote them as sites of necessary trouble.” Understanding the interaction between alternative sexualities and other aspects of identity is critical for recognizing the diverse experiences people in this community face. They have often been stigmatized, leading to discrimination, violence, and prejudices. Research has shown that there is a great impact of societal stigma on the well-being and mental health of individuals with alternative sexualities. These communities have played a profound role in supporting equal rights and promoting social changes.

The sociological analysis of alternative sexualities offers important insight into the complexity between culture, society, and individual experiences. By investigating historical aspects, societal constructions, intersectionality and mental health impacts, we can promote a more accepting and inclusive environment for the people in these communities.

Works Cited

Butler, Judith, “Imitation and Gender Insubordination” in Jackson and Scott, eds., Feminism and Sexuality, NY: Columbia, pp. 162-165.

Hawkes, Gail, Ch 8, “Subverting Heterosexuality,” pp. 144 in A Sociology of Sex and Sexuality, Open University Press, 1999.

ChatGPT was used.

0 notes

Text

an essay i wrote for class that im posting to link to it later

Ingrown: Compulsory Feminine Hairlessness, Perpetuation of the Gender Binary, and Patriarchal Control of the Feminine-Coded Body

This essay discusses gendered perceptions of body hair, the feminine hairlessness norm as perpetuating the gender binary, and the expectation of feminine hairlessness as a form of patriarchal control over feminine-coded people. ‘Feminine-coded’ is the term I am using to describe people which are normatively placed in the category of ‘woman’, which has no singular definition (Bettcher, 403).

The topic of feminine body hair is often shunned, classified as too trivial to discuss, yet, the pervasiveness of ‘mundane’ feminine hair removal suggests cultural significance. Socially mandated maintenance rituals that concern the feminine-coded body can be inspected as a microcosm reflecting a larger patriarchal system; patriarchy being the sociopolitical system that privileges masculinity over femininity. While I acknowledge there are many forms of appearance modification normatively expected of feminine-coded bodies, (such as dieting, makeup, hair styling, nail care, and skincare (Bartky, 99) and varying degrees of expectations defined by specific cultural norms and individual history, I wish to focus on feminine-coded body hair removal norms of the West (which I refer to as “the hairlessness norm” (Toerien and Wilkinson, 333)) and their implications.

Carol Hanisch’s 1969 memo, now referred to as “The Personal is Political” illuminated how problems that afflict women are commonly disregarded as “personal issues”, ignoring the fact that feminine-coded people experience patriarchal violence because of the system they are located in (Hanisch, 1969). From personal experience, the way my facial and body hair has been policed (by peers, employers, teachers, family, romantic partners, and strangers) has led me to develop trichotillomania (or “trich”, an obsessive hair pulling disorder). Exploring trich has led me to discover that the shame, guilt, and disgust I feel at my own body (hair) is socially produced through patriarchal systems. I can’t be the only one, and through this essay I wish to explore how the cultural production of feminine hairlessness enforces forms of violence and control to feminine-coded bodies. I wish to echo Hanisch’s sentiment that personal problems are political problems (Hanisch, 1969), the norm of feminine hairlessness is one of the many “mundane” ways patriarchal economic and social system exert control over feminine bodies and seek to define them as “unacceptable if unaltered” (Toerien and Wilkinson, 333).

I would like to define a few terms for this paper, ‘body hair’ will refer to facial and body hair that is normatively deemed inappropriate on feminine-coded bodies, including ‘ungroomed’ brows and unibrows, moustaches, beard/chin/cheek hair, breast, belly, and back hair, ‘ungroomed’ pubic hair, leg, toe, foot, hand, knuckle and other (non-scalp or eyelash) hair.

The ‘gender binary’ is a system in Western culture wherein individuals are expected to participate in socially produced gendered behaviour, where gender is classified as two distinct, opposite forms of masculinity and femininity. Upon birth (sometimes before), individuals are classified as either boys or girls according to their external genitalia (Bettcher, 393). During childhood, individuals learn through socialization and education what it means to “do” (perform) gender as a boy or a girl (Bettcher, 393). The gender binary system fits into Foucault’s notion of “discipline” and exists within a patriarchal power relationship, as feminine-coded bodies are expected to be altered in ways masculine-coded bodies are not. “Discipline” describes the way types of power are exercised: they are systems enforced to define and order populations, increasing the docility and utility of individuals to control them (Foucault, 136-137). Control of individuals is achieved partially through normative definitions of the body (highly subjective, but defined as “objective” by medical, governmental, popular, or social forces of their time) and what is appropriate for the body (Foucault, 140-141). Performing gender is expected in mainstream Western society, but the effort and cost for producing an ‘appropriate body’ for feminine-coded people is socially policed and informed by patriarchal institutions. For feminine-coded people, smooth, hairless, (preferably white and young) skin is expected, (especially on the face), and (in mainstream contexts,) those who ‘fail’ to meet this norm are often mocked, shamed and policed into conformity. For trans women, and feminine-coded people with darkly pigmented hair, the expectations of hairlessness are often enforced more violently and aggressively.

Hair growth patterns on different individuals vary substantially depending on factors such as age, genes and ‘race’, and the balance of testosterone and estrogen, both of which are present in most human bodies and are hormonal factors in hair growth (Toerien and Wilkinson, 335). Despite this, there is a widespread assumption that ‘men’ are ‘naturally’ hairier than ‘women’ (Toerien and Wilkinson, 335). This perspective is simplistic, binary, and discounts many relevant factors to hair growth distribution patterns. Feminine-coded people have an “equivalent potential for hair growth to men...women have hair follicles for moustache, beard, and body hair” (335 Toerien and Wilkinson), yet, popular assumptions expect the feminine body to be depilated to be viewed as “appropriately feminine”. The myth of ‘men’ as ‘naturally hairier’ is perpetuated by cultural assumptions of binary gender norms, how femininity is presented (in media and culture), and by medical definitions of what ‘counts’ as ‘normally’ or ‘abnormally’ hairy. Several scales to ‘rate’ hair growth have been proposed, but there exists no firm biological boundary to establish between the “normally” and “abnormally” hairy woman (Toerien and Wilkinson, 336). Frustratingly, within mainstream Western culture, virtually any hair on the feminine body outside the lashes, brows and scalp is considered ‘excess’, and the psychological and social consequences for feminine-coded people with ‘excess’ body hair can be profound, including depression, anxiety, stress, shame, and isolation. A study by Kitzinger & Willmott (2002) found that female-identifying participants with excessive body hair characterized their hair negatively, describing it as “‘upsetting’, ‘distressing’, ‘embarrassing’, ‘unsightly’, ‘dirty’ and ‘distasteful’” (para. 2).

Invoking a feminist curioisty (Enloe), one must ask, that if all genders may grow body hair (excluding individuals with autoimmune disorders such as alopecia), why is it that feminine hairiness is considered abnormal? The cultural context is significant. Feminine hairiness has historically been associated with negative assumptions about innapropriate conduct: masculine attitudes/aggression, deviant, repressed or queer sexuality, uncleanliness, mental illness, and witchcraft (Toerien and Wilkinson, 338). Masculine hairiness has been historically associated with virility, strength, and maturity (Toerien and Wilkinson, 337). The removal of feminine body hair is not a new or purely Western phenomena, (Toerien and Wilkinson, 333), but the current Western norm for large surfaces of hair to be removed is relatively recent, the act of removing hair from underarms and legs was “not widely practiced by most U.S. women until 1915”, when the first “womens razor” was marketed by Gillette (the “Milady Decolletée”), and as restrictions on feminine-coded bodies as needing to be completely covered were diminishing. (Toerien and Wilkinson, 333). Still, however, during the 1800’s in the West, any visible hair on feminine-coded faces was pathologized and defined as needing treatment (Toerien and Wilkinson, 333). Feminine hairlessness can be perceived as a binary-enforcing social demarcation tool to differentiate between ‘women’ and ‘men’ (Toerien and Wilkinson, 335).

Feminine hairlessness has been theorized to to suggest a child-like status afforded to feminine-coded people, unlike the adult status afforded to masculine-coded people. This relates to historical and cultural patriarchal patterns of viewing the “feminine” as lacking, incomplete, and passive (Toerien and Wilkinson 338). The term “baby smooth” often applied to freshly depilated feminine skin could be evidence of the childlike/feminine association.

For many people, body hair begins developing during puberty. During this time, individuals are often exposed to new expectations as to how to appropriately performing gender. For many feminine-coded individuals, this involves pressure from peers, parents, partners, teachers, and media, to remove hair from the face, legs, underarms, stomach, and/or pubic area. In many cases, pubescent feminine-coded people will be reliant on a caregiver for permission to depilate the body, adding a sense of lack of control or shame for many who do not have the resources or permission to depilate their bodies.

Feminine body hair is conceived of as unsanitary and often treated with the same disgust of other body products (like blood, odor and sweat) in a way that male-coded body hair is not (Toerien and Wilkinson, 338). This is perpetuated by standards of what is considered ‘good grooming’ for feminine-coded people (Toerien and Wilkinson, 338), where body hair is associated with dirtiness, and a lack of body hair with ‘cleanliness’. The association of feminine body hair with ‘dirtiness’ is tied up with racism, where more visible, pigmented hair is conceptualized as ‘dirtier’ than blond hair (Toerien and Wilkinson, 339). The “dirtiness” of feminine body hair is linked to its socially produced shamefulness, where unwanted hair is both embarrasing to develop and to remove; most cis women in hetrosexual relationships are expected to hide their depilitory “tools of transformation” (Bartky, 104) from men, to maintain the illusion of natural hairlessness. Feminine coded people who spend money to professionally remove body hair are often ridiculed for their “self indulgence” and “vanity”; this perception fails to critically examine the context within which choices to grow or remove body hair are made (Gill, 75). Adherence to “prevailing standards of bodily acceptability is a known factor in economic mobility” (Toerien and Wilkinson, 338), yet resources are required to maintain the ‘norms of bodily acceptability’, which for poor feminine-coded people, (and anyone who does not wish to depilate constantly), may be inaccessible, contributing to their exclusion from mainstream social, and professional environments.

The media plays a significant role in constructing and defining what ‘counts’ as appropriate femininity. Feminine-coded people who have hairy bodies or faces are generally absent in popular media, or used for comedic, insulting, or tokenizing purposes. The vast majority of commercials and advertisements for depilation products don’t show body hair (the first one to show body hair in 100 years came out in 2018); already-hairless legs are lathered and ‘shaved’ in commercials: perpetuating the myth that hair is unnatural, unsanitary and too taboo to even witness. The advertisement industry exploits feelings of inadequacy, shame, embarrassment, and a desire to fit in and appear ‘sexy’, ‘feminine’, and ‘confident’ in order to sell shaving creams, balms, after shaves, hair bleaches, hot and cold wax, depilatory creams, tweezers, buffing tools, electrolysis and laser treatments. The necessity for feminine bodies to absorb a ‘specialized knowledge’ in order to appropriately construct their hairless bodies is time and resource consuming (Bartkey, 99). Feminine coded people are expected to learn how to prevent and treat ingrown hairs, razor burn, how to not cut oneself shaving, burn oneself waxing, or otherwise injure oneself in an attempt to depilate. They must learn how and how often to depilate, and the proper exfoliation and after care treatments to ensure smooth and ‘properly’ hairless skin. The feminine body is transformed into a “docile body”, a body which is highly modified, policed, disciplined, and practiced, it is constantly surveilled in a panoptical sense of constant self surveillance (Bartky, 95). Everyone it seems, yet no one in particular, is enforcing the hairlessness norm; there are no public sanctions against body hair, but propagandistic norms that defines feminine hairlessness as ‘the way things are’ contribute to an invasion of the feminine-coded body by patriarchal ideologies (Bartky, 107).

The normative expectation for feminine-coded bodies to be hairless, and the disciplining by media and social systems which reward feminine-coded people who adhere to normative beauty standards, punish or mock those who don’t, and frame hairlessness as a natural, easily achievable, enjoyable, and fundamentally feminine, function to produce a disciplined, feminized, subject who devotes capital and time to a patriarchal system. The mainstream norm for feminine hairlessness is beneficial to corporate interests of keeping feminine-coded people ashamed of their bodies, burdened with expectations to alter their body, and incentives to purchase products to maintain a constant facade of natural hairlessness. It serves patriarchal interests of upholding a gender binary and maintaining norms of the feminine as passive, decorative, ‘not fully adult’, and in constant need of modification (Toerien and Wilkinson, 339).

Bibliography:

Bartky, Sandra Lee. “Foucault, Femininity and the Modernization of Patriarchal Power’ -

Chapter 5” Feminism & Foucault: Reflections on Resistance, edited by Irene Diamond and Lee Quinby, Northeastern University Press, 1988.

Bettcher, Talia Mae. “Trapped in the Wrong Theory: Re-Thinking Trans Oppression and

Resistance.” Signs, vol. 39, no. 2, 2014, pp. 383–406

Enloe, Cynthia. The Curious Feminist. University of California Press, 2004. Open WorldCat,

http://public.eblib.com/choice/publicfullrecord.aspx?p=223994.

Foucault, Michel. “The Subject and Power.” Critical Inquiry, vol. 8, no. 4, 1982, pp. 777–95.

JSTOR.

Gill, Rosalind C. “Critical Respect: The Difficulties and Dilemmas of Agency and ‘Choice’ for

Feminism: A Reply to Duits and van Zoonen.” European Journal of Women’s Studies, vol. 14, no. 1, Feb. 2007, pp. 69–80. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.1177/1350506807072318.

Hanisch, Carol. “The Personal Is Political: The Original Feminist Theory Paper at the Author’s

Web Site.” Carol Hanisch, 2009, http://www.carolhanisch.org/CHwritings/PIP.html.

Kitzinger, Celia, and Jo Willmott. “‘The Thief of Womanhood’: Women's Experience of

Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome.” Social Science & Medicine, vol. 54, no. 3, 2002, pp. 349–61.

Toerien, Merran, and Sue Wilkinson. “Gender and Body Hair: Constructing the Feminine

61 notes

·

View notes

Link

The foundations for good mental health are laid down in the emotional development that occurs in infancy and later childhood and appears to be dependent upon the quality and frequency of response to an infant or child from a parent or primary caregiver (O'Hagan 1993; Oates 1996).

...Where a child experiences a warm, intimate and continuous relationship with her or his mother or other care-giver, that child would thrive. Conversely, an unresponsive parent, or one who responds inappropriately to a child's needs, would increase the likelihood of the child becoming anxious and insecure in its attachment.If a parent inadvertently or deliberately engages in a pattern of inappropriate emotional responses, the child can be said to have experienced emotional abuse (O'Hagan 1993).

...[Emotional abuse] is increasingly considered to be the core issue in all forms of child abuse and neglect (Hart, Germain & Brassard 1987; Navarre 1987; McGee & Wolfe 1991).

Not only does emotional abuse appear to be the most prevalent form of child maltreatment, but some professionals believe it to produce the most destructive consequences (Garbarino & Vondra 1987). The effects of emotional abuse may be manifested in the sense of helplessness and worthlessness often experienced by physically abused children (Hyman 1987), in the sense of violation and shame found in sexually abused children (Brassard & McNeil 1987), or in the lack of environmental stimulation and support for normal development found in neglected children (Schakel 1987). O'Hagan (1993) has further argued that it is the emotional and psychological trauma associated with physical and sexual abuse that has the most detrimental impact on the development of children, a view supported by the United Kingdom's National Commission of Inquiry into the Prevention of Child Abuse (1996).

Definition

Briggs and Hawkins note that by 'the very nature of adult-child relationships and cultural influences, most adults will have inflicted emotional abuse on children, probably without realising it' (1996, p.21). ... Depending upon which of the many definitions is employed, emotional abuse may involve passive or neglectful acts, and/or the deliberate, cruel and active rejection of a child (Briggs & Hawkins 1996).

...In what is widely regarded as the seminal work in the field of emotional abuse, James Garbarino and associates (Garbarino 1978; Garbarino, Guttman & Seeley 1986) have provided the basis for more recent attempts at defining what Garbarino terms 'psychological maltreatment' - 'a concerted attack by an adult on a child's development of self and social competence, a pattern of psychically destructive behaviour' (Garbarino, Guttman & Seeley 1986, p.8).Under this definition, 'psychological maltreatment' is classified into five behavioural forms:

rejecting: behaviours which communicate or constitute abandonment of the child, such as a refusal to show affection;

isolating: preventing the child from participating in normal opportunities for social interaction;

terrorising: threatening the child with severe or sinister punishment, or deliberately developing a climate of fear or threat;

ignoring: where the caregiver is psychologically unavailable to the child and fails to respond to the child's behaviour;

corrupting: caregiver behaviour which encourages the child to develop false social values that reinforce antisocial or deviant behavioural patterns, such as aggression, criminal acts or substance abuse.

Garbarino has also argued that each of these forms of psychological maltreatment has a differential effect on children depending on their passage through the four major developmental stages of infancy, early childhood, school age and adolescence (Garbarino, Guttman & Seeley 1986).

For example, rejection in infancy will result from a parent's refusal to accept and respond to a child's need for human contact and attachment. In early childhood, rejection is associated with a parent who actively excludes the child from family activities. At school age, rejection takes the form of a parent who consistently communicates a negative sense of identity to the child, and in adolescence, rejection is identified by a parent's refusal to acknowledge the young person's need for greater autonomy and self-determination (Garbarino, Guttman & Seeley 1986).

...Hart, Germain and Brassard (1987) extended Garbarino's original typology of psychological maltreatment by including two other behaviours: the denial of emotional responsiveness; and acts or behaviours which degrade children.

Garbarino and Vondra (1987) included: stimulus deprivation; influence by negative or inhibiting role models; forcing children to live in dangerous and unstable environments (e.g. exposure to war, domestic violence or parental conflict); and the sexual exploitation of children by adults and parents who provide inadequate care while under the influence of drugs or alcohol.

... Pillari (1991) argued that emotional abuse is intergenerational, highlighting deeply rooted patterns of scape-goating in families where children become the source of blame for the inability of parents to resolve the detrimental consequences of their own experiences of rejection and family trauma. Pillari notes that some professional systems continue to blame children for parental disturbances, further compounding the effects on the child and minimising the potential for parents to change behaviours and attitudes towards children.

...While a variety of forms have been proposed and debated, the elements common to most conceptualisations of emotional abuse are: that the inappropriate adult behaviour must be of a sustained and repetitive nature and considered within a cultural context; and that community standards about appropriate caregiver behaviour are constantly changing and are not homogenous or easily identifiable.

With regard to the effects on the child, it is commonly agreed that: the subjective meaning constructed by victims of their experience of violation should be incorporated into the definition; a developmental perspective should be adopted in the consideration of the abuse; emotional abuse can undermine the development of children's cognitive competency and skills; emotional abuse can have a detrimental effect on children's trust and on the way they form relationships and express emotions.

Prevalence

Emotional abuse does not leave physical injuries and its ongoing nature usually means there is no crisis which would precipitate its identification by the health, welfare or criminal justice systems (Oates 1996). For that reason emotional abuse is the most hidden and underestimated form of child maltreatment.

Of the data available, and depending on the definition adopted, estimates of the prevalence of 'psychological maltreatment' vary from between 0.69 to 25.7 per cent of children (Fortin & Chamberland 1995). Emotional abuse accounts for approximately 7 per cent of all reported cases of child maltreatment across the United States (Second National Incidence Study 1986, NCANDS 1990, as cited in National Research Council 1993). However, the absence of operational definitions and true standards of severity means that the true occurrence of the extent of emotional abuse is unknown (National Research Council 1993).

The most recent national Australian data, produced by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, indicate that in 1995-96 emotional abuse cases accounted for 31 per cent of substantiated child maltreatment cases. The rate of emotional abuse among those aged 0-16 years (based on the number of substantiated child protection cases for the year) was 0.2 per cent (Broadbent & Bentley 1997). No other estimates of the prevalence or incidence of emotional abuse in Australia are known to the authors.

Causes

...Adults or parents who emotionally abuse are frequently described as poorly equipped with the knowledge to cope effectively with children's normal demands at different developmental stages (Oates 1996). A study comparing emotionally abusive parents with a closely matched control group of 'problem' parents in a day nursery (Brazelton 1982, as cited in Oates 1996), indicated that emotionally abusive parents showed poorer coping skills, poorer child management strategies, and more difficulty in forming and maintaining relationships. These parents also reported more deviant behaviour in their children displayed than parents in the control group.

Previous Clearing House publications have described a number of parental and child characteristics that may enhance the potential for emotional abuse.

For example, two of the most prevalent mental disorders identified as affecting parents who maltreat their children, namely depression and substance abuse (Chaffin, Kelleher & Hollenberg 1996), are likely to increase the potential for emotionally abusive responses (see Child Maltreatment and Mental Disorder (Tomison 1996b) and Child Maltreatment and Substance Abuse (Tomison 1996c) for a more detailed discussion).

Similarly, neuropsychological deficits or intellectual disability may increase the likelihood for inappropriate parenting and/or emotional abuse as a function of the added stress such conditions may produce (Tomison 1996a).

With regard to child characteristics, a child with a physical or intellectual disability may be more vulnerable to emotional abuse because of the greater potential for disruptions in mother-child bonding and/or greater parental stress (see Child Maltreatment and Disability (Tomison 1996a)).

Types of Emotional Abuse

Verbal Abuse

Verbal abuse is, perhaps, the core emotionally abusive behaviour.

Schaefer (1997) sought to determine which specific parental verbal utterances were generally perceived as psychologically harmful. A sample of 151 local mental health professionals and parents (120 women, 31 men) completed a questionnaire which described 18 categories of parental verbalisations commonly associated with psychological maltreatment in the literature.

Eighty per cent of respondents rated 10 of the 18 categories as being 'never acceptable' parenting practices. These were: rejection or withdrawal of love; verbal putdowns; perfectionism; negative prediction (e.g. 'you'll never amount to anything'); negative comparison (e.g. 'Why can't you be more like your sister?'); scapegoating; shaming; cursing or swearing; threats; and guilt trips (e.g. 'How could you do that after all I've done for you?').

Non-organic Failure to Thrive

Non-organic failure to thrive is one of the few forms of emotional abuse that generates observable physical symptomology for the child, and has produced a specific body of literature, particularly in the medical field.

Failure to thrive is a general term used to describe infants and children whose growth and development is significantly below age-related norms (Iwaniec, Herbert & Sluckin 1988). Cases can be classified into two categories (Oates 1982): organic failure to thrive, where a disease has caused the problem and medical treatment is prescribed; and nonorganic failure to thrive, where psychosocial factors are responsible and the treatment involves adequate feeding in combination with efforts to ensure the child's emotional needs are met. Non-organic failure to thrive has been described as the meeting point of emotional abuse and neglect (Goddard 1996).

... In contrast, other studies have reported that insufficient diet is the sole cause of non-organic failure to thrive (American Humane Association 1992, as cited in Goddard 1996; Whitten, Pettit & Fischoff 1969, as cited in Oates 1996). Yet others have concluded that the probable cause is a combination of emotional abuse and inadequate diet (Oates 1982).

Investigation of non-organic failure to thrive cases has indicated that there are often multiple family problemsoccurring, including poverty, housing problems, unemployment and marital discord (Oates 1996). The parents may have unconventional beliefs or perceptions about what constitutes a normal diet for an infant (Oates 1996); the primary caregiver (in the vast majority of cases, the mother) may be emotionally unresponsive to the child (Iwaniec, Herbert and Sluckin 1988; Oates 1996); and the mother-child relationship may appear fraught and unhappy (Iwaniec, Herbert and Sluckin 1988).

Mothers in these cases have been found to have poor parenting skills; to be immature or depressed; or to have a knowledge of parenting but to have failed to use it because of the overwhelming nature of other family problems. Some have wholly negative perceptions of their infants, accusing them of being deliberately naughty to annoy them (Oates 1982).

The infants in such cases have been described as being lethargic, anxious, fussier, more demanding and unsociable, less adaptable, more inconsolable and less happy than other babies (Iwaniec, Herbert & McNeish 1985; Oates 1996). It is not clear whether these factors merely increase the likelihood of failure to thrive, or result from it.

Witnessing Domestic Violence

There is growing recognition that domestic violence and child physical and sexual abuse are strongly associated (e.g. Goddard & Hiller 1993; Tomison 1995a). A growing body of research also suggests that children who witness domestic violence, but who are not actually physically assaulted, may suffer social and mental health problems as a result (Edleson 1995).

Systems Abuse

Systems abuse may be defined as the 'harm done to children in the context of policies or programs designed to provide care or protection. Children's welfare, development or security is undermined by the actions of individuals or by the lack of suitable policies, practices and procedures within systems or institutions' (Cashmore, Dolby & Brennan 1994, p.10).

... Typically, systems abuse can be characterised as involving one or more of the following: the failure to consider children's needs; the unavailability of appropriate services for children; a failure to effectively organise and coordinate existing services; and institutional abuse (i.e. child maltreatment perpetrated within agencies or institutions with the responsibility for the care of children (Cashmore, Dolby & Brennan 1994).

Emotional abuse inflicted via systems abuse may occur as a consequence of: traumatic child protection investigations, as a function of the out-of-home care experience (in particular, having multiple placements, a lack of continuity of care, and separation of siblings in care); the practice of removing a sexually abused child rather than the perpetrator in cases of intrafamilial abuse; the failure to punish an abuser, combined with the removal of the child (which may appear to the child as punishment for disclosing the abuse); the failure to protect children in the care system from further abuse; the experience of child witnesses in the court system; and the experience of children in the Family Court system (in particular where access or custody issues exist) (Cashmore, Dolby & Brennan 1994; Briggs & Hawkins 1996).

Schools

A particular form of systems abuse that is not frequently mentioned in the literature, is emotional abuse within educational settings. A number of studies have indicated that a proportion of teachers commonly use emotional abuse in conjunction with other punitive disciplining practices as a means of exerting control (Hart, Germain & Brassard 1987; Briggs & Hawkins 1996).

While physical punishment has been banned in most educational settings, emotional abuse often passes without comment (Briggs & Hawkins 1996). Briggs and Hawkins (1996), in their book Child Protection: A Guide for Teachers and Child Care Professionals, cite studies by Krugman and Krugman (1984) and Hyman (1985), which found that teachers emotionally abused children by: overly restricting access to toilets for very young children; threatening to tell parents of a child's misbehaviour or unsatisfactory work; rejecting the child or their work; verbally abusing children; harassing, or allowing other children to harass children; labelling children as 'ineducable', 'dumb' or 'stupid'; screaming at children till they cried; and providing a 'continuous experience of failure by setting ... tasks that are inappropriate for their stages of development' (Briggs & Hawkins 1996, p.37).

... Finally, Briggs and Hawkins (1996) highlight as emotionally abusive the failure of teachers to deal with allegations or suspicions of child maltreatment, along with the experience of bullying by peers.

Media Reporting

Finally, although not strictly a form of systems abuse, the extent of media reporting on child abuse and children may, in itself, constitute emotionally or psychologically abusive activity at the societal level (Franklin & Horwath 1996).

Since the Victorian era, the general perception of childhood has been one of a period of innocence - that children are 'innately good' (Franklin & Horwath 1996). More recently, however, children, and adolescents in particular, have been the victims of negative stereotypes held by the public and by professionals in western society (Franklin & Horwath 1996).

Media representations are the prime source of information on social problems for many people (Hutson & Liddiard 1994). Franklin and Horwath (1996) describe an ominous shift in society's perception of children, as evidenced in recent media reports in the United Kingdom. In an infamous case of child homicide in the United Kingdom in 1993, James Bulger, a two-year-old boy, was murdered by two ten-year-old boys. At the time, the two young offenders were described in the press as evil, 'powerful, destructive human being[s]' (Franklin & Horwath 1996, p.315).

Over time the media began surreptitiously to generalise their criticisms of the two boys such that the character of all children was impugned, challenging the concept of childhood innocence and the perception that children are 'innately good'. According to Franklin and Horwath, since the Bulger case media presentations of children and childhood in the United Kingdom have continued to be presented in a distinctive and sinister fashion.

Implications

It is contended that the promotion of negative stereotyping of children and young people is directly and indirectly emotionally and psychologically abusive.

First, developing the perception of children as powerful, evil creatures both dehumanises children and acts both as justification and reinforcement for the behaviour of perpetrators of sexual and physical abuse. Such perceptions reinforce a distorted view of children as evil and out of control - children who lead adults astray, and are thus in need of punishment. This victim blaming runs directly counter to, and conflicts with, current approaches to offender treatment, which focus on offenders acknowledging that their crimes are an abuse of power. 'How much more convenient, as well as morally reassuring, to blame the victim' (Franklin & Horwath 1996, p.317).

Second, the portrayal of children in a negative manner by the media may also lead child victims of maltreatment to blame themselves for the assaults they have suffered, internalising the messages of perpetrators that they 'deserve' to be abused, and increasing their willingness to accept the abuse.

Third, how society values and perceives children 'fundamentally affects the size and direction of public investment in their services' (Walby 1996, p.25). If children and young people are perceived in negative terms - as a 'problem group', a 'threat to social stability' or as 'disadvantaged' - the resultant policies are most likely to be designed to control, manage and rehabilitate youth, rather than to encourage and support young people's transition to adulthood (Drury & Jamrozik 1985). In contrast, promoting positive societal perceptions of children and young people may, in turn, lead to the development of 'child-friendly' government policies.

Community Education

Despite the growing acknowledgment of child maltreatment as a societal problem, it is often difficult to convince those in the broader community that they, themselves, may be part of the problem. It is easier to think of maltreaters in stereotypical ways, pathologising them as mentally ill, abnormal or evil, enabling non-offenders to distance themselves from the problem rather than to address the true causes of maltreatment, such as poverty, or a lack of social support (Wilczynski & Sinclair 1996).

However, most adults will have experienced emotional abuse as children (whether they have labelled it as such or not), and subsequently inflicted it on children themselves (Hart, Germain & Brassard 1987; Briggs & Hawkins 1996). It is contended that emotional abuse is therefore the form of maltreatment most likely to result in the public seeing themselves as 'part of the problem'.

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

ID:120601

Date: May 31, 2020

Words:1500

Assignment 2

Introduction:

Media has been changed over the hundred years ago, from small things to large and modern tools. Which make a niche for several issues, using in wrong way and use it for war. So, it's difficult to know the media like that, a while we'd like to ask hard and difficult question to possess a critical understanding for the media, for love or money that connect with media, in political, culture, it represents the channel that represents culture and therefore the expression of identity. Additionally, it create many of issues like disinformation, labelling and therefore the other.

Develop the media

Media plays a crucial role in transforming societies from traditional to modern. . There are essential question about the democratic nature of the media and therefore the media saturated with commercial interests. However, at the past, they used old media for other reasons like war. It utilized in war 1 and a couple of , there was a communication system like a telegraph, which British army wont to communicate with their commanders. within the other side, war 2, the communication were developed lots. The countries within the war used radiotherapy. therein war use sorts of propaganda like in radio, posters, magazines and news.

In lately new media and platforms has changed the. These tools are faster and more personal and large than all tools of old media, have a quick ability to send, combine and distribute all contents via any medium. In fact, technology plays the role of a huge oasis with lately , which is described as communication and knowledge age. Social Media has broken the perception of dominant social, cultural and political structures.

Social networking:

Social networking may be a group of individuals can contact between other for a selected reason. One examples to tend as a social network is anyone’s circle of friends. during this world, there are similar characteristics and patterns of behavior, which are an important a part of every person behavior on Twitter, Facebook or Snapshot.

Now, with coronavirus the most important and more important trend is: technology, then social media, followed by video call. additionally , plan online education in many colleges.

Social media has been forced to require a more active stance against disinformation during the COVID-19. From survival kits, social media round the world is responding to it. Like Facebook is providing location tracking data to health authorities to assist them combat COVID-19 providing individual connectivity maps indicating whether people are staying home.

Therefore, social media are often a source of essential data for mapping the spread of the disease and managing it. Geographic information systems that repose on data from social media and other sources have already become key to mapping the worldwide spread of COVID-19.

By developed the new media and be most vital things that announced many information and news from the most place, it becomes thing to deliver the messages, named Comics.

Visual narratives, like comics and animations, are getting increasingly popular as a tool for science education and communication, it makes scientific subjects more accessible and interesting for a wider audience. within the past, decades comics have emerged as an increasingly popular sort of communication, ready to engage readers of various age groups and cultural backgrounds.

It is important first to understand the novel or information, but the standard that separates the storyboards from the articles is that they depend mainly on a particular arrangement of images to point out the story. additionally , it's going to be necessary for young readers to be the story with fictional characters and situations to present and simplify information, however but might be viewed as childish by adults. the instance of comics is a few character about Corona virus shows that the chopper, it's like saying COVED-19 came from eating sorts of animals, that we've not ate it. That Virus comes from those animals, in order that they say Coronavirus is formed by the humans themselves. It also show like snake within the character, because its like killer machine, dangers and may kill people easily.

Therefore, Comics are influential for several reasons:

1- Comics are attractive. they're strongly magnetic and visually appealing.

2- Comics make it simpler, by entering humor.

3- Comics push authors to write down more stories, making the audience react faster.

After all that development for media, it start change in our days, its became an activity and awareness especially the new one, with new technology and equipment can improve it. Social media makes the communication easier between people nowadays. But it change this thing, it become like freedom when write or post, and it increase the misunderstanding, hate speech and disinformation altogether of old media and new of it. Nowadays, people in media attempt to effect and write fake information about many things which will believe it who are didn't know the reality and search about it.

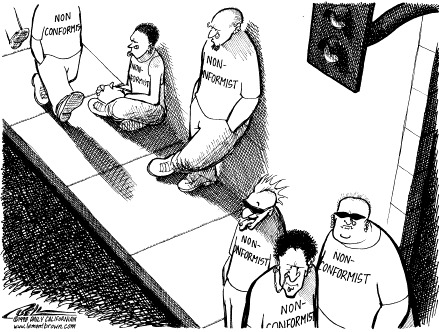

Labelling:

Labelling theory is an analyze how social groups create and apply definitions for deviant behavior. The closer examines how its developed the facility to impose labels onto selected others. It helps to elucidate why a behavior is taken into account negatively deviant to some people, groups, and cultures but positively deviant to others. for instance , fictional vigilantes, like Robin Hood and Batman. many years ago, people yearned for stories a few hero, a person who could save them from the retched body waste that littered the streets. Therefore, Robin Hood became a legend to the commoner , a beacon of hope and how to flee their dire existence through adventurous stories of a hero.

Moral panic is defined as a situation wherein. A condition, episode, person or group of persons emerges to become defined as a threat to societal values and interests, its nature is presented during a stylized and stereotypical fashion by the mass media, the moral barricades are manned by editors, politicians and other right-thinking people.

Stereotypical phrases related to these youth cultures thugs, hooligans, menaces repeatedly are highlighted in bold news headlines to strengthen pre-existing perceptions and beliefs held by "normal folk"

And the most examples is that the western media describe the Muslim as terrorists and he's tough in religious but when the American or people from different religious do the same and killing the Muslims they don’t dais that, they show on TV something different. Therefore, they create labels in media, old and new media.

Moreover, by developed the media, it comes the definition of disinformation. The most goal of it is the concepts of an establishment or state, distorting the viewer's ideas, influencing the mind and controlling emotions to form them with the active institution, and therefore the strongest sorts of it are brainwashing in critical issues that no country or institution can erase from the record. It comes with Hitler story in war 2, how Hitler persuaded the Nazi German people to make an unparalleled army to wage wars that participated in war. Convincing wasn't that easy, brainwashing and deception were wont to hide the reality of what Hitler had and his ambition to invade and attack countries. Now, they use it secretly by many countries, media institutions, politicians and influential people within the country.

Create hate speech gives space to governments to regulate of everything, In fact, some people want to destroy system of governments or country, and do what they need , therefore the government used it to prevent them. Also hate speech is sweet for a few crises like what's happening within the world, Corona Virus, to form the country safe most use it. And social media gives the free speech, which are often more dangers to write down anything.

Media and shown narcissism/ human kind:

Narcissism means selfishness, and it is a mental disturbance that's characterized by arrogance, transcendence, also it is a way of importance and an attempt to understand even at the expense of others. The narcissist sees that he's more beautiful and people less beautiful than him. It cares tons about his appearance and therefore the refore the way he look and he's choice his clothes carefully and cares about how he looks within the eyes of others and the thanks to convince them. Media has change some people, by being famous, so his or her are going to be selfish.

In addition, Social Media show the woman as a commodity and she or he isn't as we see her within the life, where the weakness is that she is unable to work and continue without an individual , unlike an individual who always appears with a strong and controlling personality which he's sexually aggressive and hard tough which you've plenty of superpower and capabilities.

Conclusion:

Media (old and new) year-by-year change, most changes is currently be more effect for people that doesn't know truth . Also, media gives us easier life, information and the way easy to attach with one another , in most situation, media start to send many news from the most place to receive the knowledge fast.

#Mass2620_20 #SQURT

1 note

·

View note

Text

“How can I create a non-pathological culture, while embracing deviancy and tradition at the same time?”

Deviance can be defined as an absence of conformity to the social norm. Not all deviant behavior is necessarily illegal or harmful to individuals, these behaviors can range from a standing in another’s personal space to murdering another individual. In some cases, it can be looked upon as a positive change or a unique favorable act. Although, considered deviant because it is not the social norm, it still can have a very positive social aspect or lead to social change. Culture and the societies within these cultures have a significant impact on what it is considered deviant and what is acceptable or even lawful behavior. The degree of deviance is measured by society’s reaction towards the action and the lawful sanctions that may take. Abnormal behavior in one society appears normal in the other society (Nairne, 426). Deviance is weighed by the society’s way of life so that it defines the unwelcoming behavior. It ignores the social order and some organizations believe the reality in society. The violation of the social norm can be meant to be utilized as a way of sustaining power, position, and influence of a specific group of people or organizations. In most cultures, the idea of deviance is based on the values, deeds, and beliefs that are achieved through interaction among people that have influence in the society and form the understanding that culture is passed on for member to member. Societies are also comprised of subculture and the culture itself. The huge cultural forces depict what deeds are appreciated and which are unaccepted or discouraged. On the other hand, the subculture in a certain setting creates a resistance to the dominating culture social norms can be attributed to the social classes and financial classes. For example, prostitution in regions of the developing world is deviant in most cultures; however poverty pressure pushes young girls towards survival.

When we say, non-pathological culture by all means it is vulnerable to any solutions, meaning you can fix that particular situation in regards with cultures. The thing is, how am I going to attempt this while embracing the aspects of deviancy and culture at the same time, we will find out soon about that. Often times when we hear the word culture, we think of the differences of different countries. That statement may be true; however, there are different cultures within the same country, even within the same city. No matter what culture we call our own, there are distinct differences between that of other cultures around us and it depends on many factors like location or audience. One of the major differences occurs in the realm of family; family affection to be more specific. When talking about family affection, we should consider many different aspects. It was my task and privilege to explore these aspects. I consider myself having a strong Filipino culture. My family has been here for many years and has adopted the “Filipino Way”. This is some sort of unpopular opinion but, straight ahead I can maintain a non-pathological culture while embracing those. I believe that there were no perfect cultures out there, as it said that deviance deals about the violation of social norms and practices in respective society and now that you are aware already what exactly it is, that way you have all the freedom to manipulate yourself how to attempt a no pathology culture. Embracing deviancy and culture is either bad or in a good way it all depends the way you handle them. This time I have to be honest with you, I have lived for a decade and possessed different kinds of culture and sometimes I act the nature of deviancy without knowing what it is, but still I had this non pathological culture inside me meaning I did embrace it already. Abstract before referring to the impact of culture on families, I will say that culture is known as knowledge, art, beliefs, law, morals, customs and all habits and skills acquired by man not only in the family but also to be part of a society as a member that is. It also defined as a set of ideas, behaviors, symbols and social practices learned from generation to generation through life in society. When planning to create a family there has to be a lot stairs to take, it is very traditional to us humans that creating ones, start by courtship, now courtship is the stage of preparatory to marriage and may include all forms of behavior by which an individual seeks to win the consent of another to a marriage. There are four stages of courtship, first is dating in this stage, man and woman are provided opportunity from friendly relations. Getting to know each other is the primary aim of dating. Next is, going steady, it refers to the practice of dating one person exclusively, although it does not necessarily imply the prospect of marriage. After that, you have to take practice a private understanding where a man openly declares his love and affection for the woman and his desire to have her for a wife now the last thing is engagement which is it culminates in public where it takes into account the involvement relative and friends. Now that you have passed all those stages and owns the sweet ‘yes’ of a woman you are not entering in the world of marriage which gives you the idea that it is a legally recognized social contract between two people , traditionally based on a sexual relationship and implying a permanence of the union. Now as a man and wife, you are now socially recognized group (usually joined by blood, marriage, or adoption) that forms an emotional connection and serves as an economic unit of society.

However, there are two types of deviance we have here the over conformity that deals about positive deviance. It means that this involves behavior that over conforms to social expectations. While on the other hand, under conformity, it refers about the negative deviance where it involves behavior that under conforms to social expectations people either reject, misinterpret or are unaware of the norms. Deviant behavior in terms of broad social conditions is constantly changing. Deviance is not just a matter of numbers nor what is less common. Deviant acts are not necessarily against the law but are considered abnormal and may be regarded as immoral rather than illegal. Am act is deviant because most would consider it immoral rather than criminal because it is not against the laws of that jurisdiction. Other acts of deviance are necessarily immoral but are considered strange and violate social norms. Social norms are behaviors accepted by either a significant group of people or those with the power to enforce. These types of deviant acts are meaningful though not considered to be criminal under a legal definition. While some aspects of personality may be inherited, psychologists largely see personality as a matter of socialization and deviance as a matter of socialization and deviance as a matter of improper socialization. Individuals participating in these types of acts may exhibit a tendency toward antisocial behavior often linked to criminal behavior. While there is value in approaches, each is limited in their explanation of deviance for they only understand deviance as a matter of abnormality and do not answer the question of why the things that is deviant in the first place. Additionally, many jurisdictions are moving to have these deviant behaviors declared illegal while others are doing the opposite to have longer considered illegal. Social control is an attempt to regulate people’s thoughts and behaviors in ways that control, or punish, deviance. These negative sanctions are negative social reactions to deviance. The opposite are positive sanctions that are affirmative reactions that are usually in response to conformity. Formal sanctioning of deviance occurs when norms are codified into law, and violation almost always results in negative sanctions from the criminal justice system. The stake in conformity is the extent to which individuals are willing to risk by breaking the law or invested in traditional society standards. Agreeing on what is considered deviant behavior is important because studies have shown that shake in conformity is one of the most influential factors in an individual’s decision to offend. Individuals who have nothing to lose are more likely to take risks and violate norms than those who have relatively.

Therefore, understanding what constitutes deviance is the first step toward defining which acts violate social norms. The construction of social norms, which may vary from society to society, illustrates that deviance is a social phenomenon. Only norm violations found most unacceptable to society are codified into law and acted upon by criminal justice agencies. It is very understandable that we as a living individual we have all different races, beliefs and culture it is up to one of us how are we going to manage and control those, I mean it’s not a mistake when you mold a no pathology culture while cuddling deviancy it’s just the people who think that it’s a mistake and the society within that. Just continue what you are doing and be comfortable for whatever it is.

youtube

youtube

youtube

0 notes

Text

Culture and conTROLL freaks; An insight into the practice of trolling in an online space.

It has been generally accepted among communities that the internet and social media networks are full of deviant individuals and behaviors. With many platforms offering an opportunity for ultimate anonymity and a perceived lack of consequences the internet as a whole has been synonymous with certain people using the platform to express anti-social, deviant or even violent behaviors is called trolling. This blog post shall discuss what trolling is, who a troll is and, with the use of the case study pertaining to Chelsea King, how trolling can be applied to real world situations.

Online trolling has become a vastly popular topic within internet communities and has attracted a plethora of media attention over the last couple of years, however it remains a topic that is under-researched, with little scholarly attention paid to it (Fichman and Sanfilippo, 2016). This may be attributed to the fact that the term is still in its infancy or simply because the definition for trolling is in a constant state of change and evolvement, with it having never been clearly differentiated from other deviant or negative behaviors and attitudes found online (Fichman and Sanfilippo, 2016). However, for the purpose of this essay we shall define trolling as a repetitive and hugely disruptive set of behaviors that are exhibited on an online platform in order to target a specific individual or group (Fichman and Sanfilippo, 2016). This is performed often with the intention of publicly shaming them, drawing them into an argument or diverting attention away from the original intent of the group (Fichman and Sanfilippo, 2016).

While the act of trolling has been defined, in order to understand the concept as a whole, one should have a thorough understanding of who is classified as a troll (Hardaker, 2010). However, a severe lack of clarity and indeed a large lack of agreement on the term and who can be classified under it, makes it a challenging task (Hardaker, 2010). One explanation that has proven to be both sufficiently detailed and succinct details an internet troll as an individual that operates through an online platform and seeks to provoke others in order to elicit responses that are hostile, naive or corrective in nature (Phillips and Milner, 2017,7). This person can also be a troll by reacting in a primarily emotional manner in order to elicit response or stimulate action from supporters (Phillips and Milner, 2017).

While Social Media platforms are widely accepted as having a global reach and an audience pool that increases exponentially it is no surprise that it has offered individuals with positive opportunities in which individuals can share and communicate, traversing boundaries connecting with others in a way that has previously not been possible (Barlow and Awan, 2016). Indeed, with the internet offering instantaneous communication as well as the compression of time and space there is a significant increase in the speed of communicative processes and a reduction in cultural latency (Stein, 2016). However, taking into consideration the instantaneous and far reaching effect of the internet it can also act as a double-edged sword (Barlow and Awan, 2016). By fashioning a cybernetic universe for individuals who employ hate speech as a means to directly target others while simultaneously maintaining their anonymity (Barlow and Awan, 2016). Thus, users often are found to exhibit behaviour and express opinions online that they would not normally be able to demonstrate in a real-world example without incurring significant consequence (Stein, 2016).

I, myself, have found that the internet often provides one with a false sense of security, I often am under the assumption that other individuals do not know my real identity and therefore my responses can often be different in comparison to if I was responding in person. I am traditionally more daring and more likely to disagree with someone online than in person. This is due to the fact that despite how heated the confrontation may get I am still relatively removed from the situation and can choose to withdraw entirely whenever I see fit.

Psychologists have applied the term ‘online disinhibition effect’ to this notion, in which aspects such as online anonymity, a perceived idea of invisibility, a lack of recognisable authority and the fact that the majority of communication is not happening in real time, serves to degrade the attitudes, established rules of etiquette and accepted cultural practices that many millennia has spent enforcing (Stein, 2016).Indeed, online trolling usually occurs in an asynchronous manner, when the individual responsible for the slander or inappropriate content does not communicate with the victim concurrently (Stein, 2016). This is due to the fact that it is easier to bait the victim with a form of provocation and then leave the scene temporarily (Stein, 2016).

Trolling and the severity of the behaviour can differ depending on specific circumstance, indeed in 2010 trolling reached a new height on the social media platform, Facebook and a new and particularly virulent form of subcultural trolling began to take over (Phillips and Milner, 2017). Unlike other social networking sites such as 4Chan – whose anonymous interactions didn’t extend beyond a particular coordinated attack against a chosen target – trolling on Facebook allowed for the creation of a of a relatively stable and antisocial network in which trolls were able to form close-knit groups to target a whole host of on-site causes, public personalities and affinity groups (Phillips and Milner, 2017).

Arguably one of the most outrageous of these behaviors occurred on what Facebook called the “memorial pages” (Phillips, 2017,8). These pages which are sometimes referred to as RIP pages offer an opportunity to friends, fans and family of the deceased to find comfort in the sense of community, post messages of condolence, keep an open line of communication with other users and to be witness to any site updates or group announcements (Phillips, 2017). Although it is a requirement of the site for people who want to contribute to be members of the page, the condolence pages are usually accessible to all. Hence making them ostensibly private but effectively representative of a very open and public space (Phillips, 2017). Consequently, the tone and at times the coherency of the comments posted vary greatly (Phillips, 2017).

With the death of a family member often being a disturbing and traumatic event in one’s life, many people find comfort in the support and love that is shown on social media networks. Facebook, in my personal case, was abuzz with messages of condolences and I was flooded for days after with memorial pictures of my lost loved one. Indeed, it was a haven of good memories, past photographs of the family and an overwhelming amount of support and love from friends and family all over the globe. However, this is not always the case and Facebook memorial pages can often turn into a platform in which hate is spewed. This is demonstrated clearly through the case of Chelsea King.

youtube

Chelsea King was often described by those who knew her as a golden girl of sorts, attractive, intelligent and well-liked by all who knew her (Phillips, 2017). When Chelsea was first reported missing after she failed to return home from a run on the 27th February 2010, everyone assumed the worst (Phillips, 2017). Their worst fears were confirmed when on the 1st of March John Gardener was taken into custody and charged with the rape and murder of two girls, one of them being Chelsea King (Phillips, 2017). Her body was found dumped in a make-shift grave days later (Phillips, 2017). On the internet, concerned individuals and well-wishers who were based all over the world had begun using Facebook as a network platform to express their sympathy, follow the case and cheerlead the search effort (Phillips, 2017). Pages like “Help Find Chelsea King” initially had a following of 80,000 people, however, after she was found dead that number skyrocketed with tens of thousands of group members joining and almost instantaneously the “Help Find Chelsea King” pages gave way to the memorial pages in honour of the dead teen (Phillips, 2017). The majority of the users had never met Chelsea, however they felt inextricably connected to the case and involved with the narrative that surrounded it (Phillips, 2017). This resulted in a number of negative comments as well as a slew of inappropriate remarks that were often sexual in nature (Phillips, 2017). Indeed, one user asked if there were any nude photographs of Chelsea while another used the platform to threaten another user defending the memory of Chelsea with the rape of her mother and sister (Phillips, 2017). Another user who went by the username “Francis Bagadonuts” posted the Google image of a user’s house who disagreed with him on a thread pertaining to Chelsea’s page (Phillips, 2017).

The situation escalated when a troll by the name of Mike McMullen launched a page with the title “I bet this pickle can get more likes than Chelsea King” (Karpi, 2017). Using a picture of a frowning cartoon pickle dressed in underwear and holding an obviously Photo-shopped cut-out of Chelsea’s head (Karpi, 2017). The massive reaction to the page was instantaneous and it was flooded with offensive images, statements and opinions as well as a large body of users who liked the page in order to defend the memory of Chelsea King (Karpi, 2017). Indeed, the page received so much attention that a reporter belonging to ABC went to interview McMullen who demonstrated an entirely apathetic attitude to the entire situation and the reprehensible things his platform has resulted in (Karpi, 2017). As mortified as the ABC audiences were at the story unfolding, the majority of the comments left on the Pickle page were too horrendous and explicit for Prime-Time audiences and thus were left out of the segment (Phillips, 2017). Furthermore, the segment failed to acknowledge in any way that the story was actually the tip of a far deeper and more serious problem, one that extended far beyond a single fan page (Phillips, 2017). In contrast to the belief that the pickle page was an horrendous yet isolated incident it represented the beginning of what eventually became known as RIP trolling (Phillips, 2017).

The above example is a horrifying testament to the damage that can be inflicted by an internet troll and the fact that it is such an accepted piece of social media today proves greatly concerning to many individuals, me included. I find it a disturbing notion that at any given time there will be someone within my social circles that are being either targeted directly or having their opinions lamented or slammed by others. Indeed, I myself have been a direct target of online Trolling. Belonging to the popular social media forum, Reddit. One automatically is cautious of what one comments or posts. Although usernames are anonymous and there is no information directly pertaining to my actual identity there is no shortage of people who are willing to pick apart the profile of those who dare share their personal information, experiences, opinions or accomplishments on the forum.

In my opinion, while Reddit is a social media site that is known for harboring a slew of internet trolls, it is not all negative, indeed many of the subreddits offer motivation , support and inspiration.r/loseit was one such community in which people who were looking to lead healthier lifestyles and lose weight could be given advice, be encouraged when lacking motivation and share progress pictures in order to achieve a common goal of being both happier and healthier. I had belonged to this community for a year and found it a great source of inspiration and motivation as it was full of like-minded individuals. However, the subreddit was not completely devoid of trolls. On one occasion, having lost a significant amount of weight, a progress picture was uploaded with an emoticon of a sun hiding my face on both photographs to protect my identity- the thought process was that I wanted to share my victories with others but not have a permanent reminder of it uploaded onto the internet. However, this small action seemed to be the catalyst for a slew of insults and jokes pertaining to the necessity of having to hide my face. One user insinuated that while I could do everything to change my physique there was nothing I could do to change my face. While another made lewd sexual comments. The more ferocious the comment the more attention it seemed to garner and the more upvotes it received proving that it was most probably said to generate a reaction either from me or other Reddit members. They certainly achieved the intended as the comments deviated so far from the original picture and contained so many instances of trolling it was eventually locked by a moderator of the post.

Internet trolling has fast become one of the most popular and fastest spreading piece of jargon in the 21st century. Indeed, the practice of trolling has become so pervasive and normalised within society it is often barely noticed as being unusual. Instead it is accepted as being a part of belonging to social media and other online networking platforms. Trolls and the practice of trolling occurs on a daily basis and is often performed by those who hide behind the anonymity the internet affords them- with usernames, fake profiles and ways to shield their true identity it becomes the perfect environment in which trolling can occur with the possibility of consequence being very slim. Trolling can often be extremely deviant, this was highlighted through the case study of Chelsea King whose death triggered the beginning of what was to become known as the Facebook memorial pages and through my own personal experiences. Thus this blog post has discussed what trolling is, who a troll is and how it is applied in a real-world situations.

Biblography

abc News 2010. Chelsea Kings body found. Video. Retrieved 1 November,2017 from the World Wide Wed; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vcLmmiY0VM4.

Barlow, C. and Awan, I. 2016. You Need to Be Sorted Out with a Knife: The Attempted Online Silencing of Women and People of Muslim Faith Within Academia. Social Media + Society,2-4.

Fichman, P. and Sanfilippo, M. 2016. Online trolling and its Perpetrators: Under the Cyber Bridge. London: Rowman and Littlefield,9-16.

Hardaker, C. 2010. Trolling in asynchronous computer-mediated communication: From user discussions to academic definitions. Journal of Politeness Research. Language, Behaviour, Culture,1-29.

Karpi, T. 2017. Change name to no-one, Like peoples statuses, Facebook Trolling and managing peoples online Personas. The Fiber Culture Journal. Online, retrieved 29 October,2017 from the World Wide Web:http://twentytwo.fibreculturejournal.org/fcj-166-change-name-to-no-one-like-peoples-status-facebook-trolling-and-managing-online-personas/.

Phillips, W. 2017. LOLing at Tragedy; Facebook trolls, memorial pages and Resistance to grief online. First Monday. Online. Retrieved 29 October,2017 from the World Wide Web: http://firstmonday.org/article/view/3168/3115.

Phillips, W. and Milner, R. 2017. The Ambivalent Internet:Mischief, Oddity, and Antagonism Online. New York: John Wiley and Sons,6-10.

0 notes

Text

Come Out, Come Out, Whoever You Are!

New Post has been published on http://iofferwith.xyz/come-out-come-out-whoever-you-are/

Come Out, Come Out, Whoever You Are!

Review

Nathan Tipton

Harry M. Benshoff, Monsters in the Closet Homosexuality and the Horror Film. (Manchester: Manchester U P, 1998.) $18.95.

Come Out, Come Out, Whoever You Are!

1. “The plot discovered is the finding of evil where we have always known it to be: in the other” (97). So wrote Leslie Fiedler in The End of Innocence (1955), his summation of the McCarthy-era horrors. Although ostensibly referring to the 1953-54 McCarthy hearings, Fiedler discloses the societal fear of difference operating within the “Us versus Them” dialectic. Moreover, by finding evil in an Otherness “where we have always known it to be,” he acknowledges both the historical construction and destruction of the Other and, in effect, explains society’s genocidal predilections in the name of moral preservation. Nevertheless, Fiedler’s comment leaves larger questions unanswered. How, for instance, does society arrive at this conflation of evil and “other?” And does society need to create monsters for the sole purpose of destroying them?

2. Harry M. Benshoff “outs” his Monsters In the Closet with the conceit of a “monster queer” universally viewed as anyone who assumes a contra-heterosexual self-identity, including those outside the established gay/lesbian counter-hegemony (“interracial sex and sex between physically challenged people” [5]). For the sake of brevity, his work focuses on homosexual males and their presence, either tacit or overt, in the modern horror film. In so doing, Monsters also proposes (with more than a passing nod to gay historiographer George Chauncey), an extant gay history created through the magic of cinema. For Benshoff, however, the screening room quickly morphs into a Grand Guignol-styled Theatre of Blood, and gays become metaphorical monsters whose sole purpose in horror films is to subvert society before meeting their expected demise.

3. Benshoff draws a provocative, decade-by-decade timeline to illuminate his thesis. He begins in 1930s Depression-era America, the “Golden Age of Hollywood Horror.” In a chapter entitled “Defining the monster queer,” the cultural construction of the modern homosexual is placed alongside (and within) classic horror films such as Frankenstein and Dracula (both 1931). Benshoff notes the decade’s movement from viewing homosexuals as gender deviants to those engaging in “sexual-object choice (48),” thus underscoring the ideological shift from Other-as-Separate to Other-Among-Us. This, then, becomes his foundation motif for the modern horror cinema: the fears within us are the fears of us.