#Willapa National Wildlife Refuge

Text

You have NO IDEA HOW HAPPY THIS MAKES ME!!!!!! Willapa NWR is my "home refuge", so to speak. I've volunteered there for hours, spent a ton of time walking the trails, and it is incredibly dear to me. They're already protecting and restoring thousands of acres of land, from tidal wetlands to old-growth forests to dune habitat and more. This funding approval means that Willapa NWR will receive $1,255,248 to acquire 239 acres of land for the purpose of preserving waterfowl and other wildlife habitat.

Habitat loss is THE single biggest cause of species endangerment and extinction, so the more we're able to protect, the better--especially if we can create wildlife corridors between sections. Biodiverse ecosystems also have a better chance of weathering the effects of climate change.

Along with the habitat acquired for Willapa NWR, funding was also approved to purchase land for other Refuges:

Cat Island National Wildlife Refuge in Louisiana – $1,466,000 to acquire 548 acres.

Clarks River National Wildlife Refuge in Kentucky – $6,621,000 to acquire 2,482 acres.

Green River National Wildlife Refuge in Kentucky – $11,372,000 to acquire 1,335 acres.

Silvio O. Conte National Fish and Wildlife Refuge in New Hampshire – $1,066,450 to acquire 797 acres.

The funding was acquired through the sales of Federal Duck Stamps; 98% of the money from these stamps goes into purchasing and maintaining Refuge lands. While these were originally created to raise funds for waterfowl land by requiring waterfowl hunters to buy a stamp with their license each year, anyone can buy a Duck Stamp. There are lots of non-hunting collectors who buy them for the art, and the annual art contest draws talent from across the country. The Junior Duck Stamp Program allows young artists K-12 to enter their own contest while also learning about conservation. (It also was the topic of one of my more infamous posts here on Tumblr!)

#conservation#environment#environmentalism#Willapa National Wildlife Refuge#National Wildlife refuge#wildlife refuge#wildlife habitat#wildlife corridors#wildlife#animals#nature#climate change#biodiversity#endangered species#extinction#Washington#Washington State#PNW#Pacific Northwest

145 notes

·

View notes

Text

[H]istorians should see space as dynamic rather than simply as a container in which historical events unfold, and consider the relationships between scales rather than focusing only on the local, regional, or national. [...] [E]ven further [...] that scale itself is constructed. [...]

In the fall of 1946, thousands of ducks and geese descended into the Klamath Basin. Straddling the Oregon-California border, the basin funnels the different flight paths that migratory waterfowl follow, bringing up to seven million birds together at one time in the basin's marshes. During the previous four decades, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation had drained most of the wetlands in the basin. Two U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) refuges, Lower Klamath Refuge and Tule Lake Refuge, contained the few remaining marshes that once blanketed the area. The Bureau of Reclamation had converted parts of the lakebeds into homesteads, many for World War I and World War II veterans. Hence, the birds flew into a landscape of wetlands surrounded by grain farms.

The birds found little food on the refuge and quickly moved on to the nearby fields of barley and wheat. Farmers watched in anger as acres of grain disappeared into the stomachs of mallards and pintails. Federal regulations [...] prevented the farmers from shooting the "trespassers," so they called on the FWS, the agency that was supposed to provide sanctuary for the birds in its wildlife refuges. Pressured to take action, the FWS tried a number of methods to help the farmers clear their fields of waterfowl. Using military surplus equipment like smoke grenades, searchlights, and small airplanes, the FWS herded the birds back into the refuges. The service also issued permits that allowed local farmers and their Mexican laborers to scare them from the fields with shotguns and flares. [...] For the most part, the birds remained there until hunters came to kill them after the beginning of hunting season in October, or until they flew south to their wintering grounds in California's Central Valley and Mexico. [...]

Since the retreat of the glaciers over 10,000 years ago, migratory waterfowl have connected the wetlands of western North America. The Pacific Flyway, the westernmost of four migratory routes, encompasses widely spaced marshes stretching from the Arctic and the Canadian prairies to the interior valleys of California and the wetlands of western Mexico.

Large saltwater marshes exist only in the Fraser River Delta, Puget Sound, Willapa Bay, Humboldt Bay, and San Francisco Bay. In from the coast, mountains and aridity restrict marshes to the sloughs along riverbanks and the basins and valleys of the interior west: the Malheur Basin in eastern Oregon, the Klamath Basin on the Oregon-California state line, the Central Valley in California, and before dams and canals upstream starved it of water, the delta of the Colorado River.

Since 80 percent of the waterfowl along the Pacific Flyway passed through the Tule Lake and Lower Klamath Refuges, these Klamath Basin refuges served as a focal point for problems along the flyway. Farmers leased large portions of the two refuges [...]. [W]hen the Bureau of Reclamation decided to drain Lower Klamath Lake to create farmland in 1917 [...] [t]he Bureau of Reclamation turned one of the nation's premier wildlife sanctuaries into a dust bowl [...] Like a chain, the Pacific Flyway was only as strong as its weakest link. Destruction of key habitats in either the breeding or wintering areas of the flyway could devastate waterfowl populations throughout the western United States, Canada, and Mexico.

---

Robert M. Wilson. “Directing the Flow: Migratory Waterfowl, Scale, and Mobility in Western North America.” April 2002.

123 notes

·

View notes

Text

Racing the Tide

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service heavy equipment operators tackle challenging nighttime project on Oregon Coast

The tide was slowly draining out of Nestucca Bay, and it was still hours before the sun would peek above the horizon. The only light was from headlights of the machinery that was already rumbling along in the cool night air, moving dirt at a furious pace.

A crew of U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service heavy equipment operators were racing the tide.

The objective was to install a fish screen for a pump, and remove and replace tide gates that help manage water levels on the Upton Slough section of Nestucca Bay National Wildlife Refuge on the Oregon Coast.

The entire project took weeks, but this critical element had to be done in a narrow window of time at the lowest tides last fall.

This work on soft ground on the bank of the Little Nestucca River was left to a crew of five heavy machinery operators from National Wildlife Refuges across the Columbia-Pacific Northwest Region.

Story Map with videos and audio clips available at

https://fws.maps.arcgis.com/apps/Cascade/index.html?appid=64cdfe78fe87436881551befde79b8e7

In bureaucratic terms, the heavy equipment operators are known as wage-grade professionals. That’s the official term.

But to project leaders, facility managers and biologists --- they simply call them the backbone of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. They're the people who turn habitat conservation dreams into reality.

They're creators of conservation.

“They are so important to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service's mission. Without our wage-grade professionals, we couldn't accomplish the important habitat and conservation work we do on refuges. They're unsung heroes of conservation,” said Kevin Foerster, Refuge Chief for the Columbia-Pacific Northwest Region.

Due to the location and environmental factors for the Upton Slough work, this project had a variety of technical challenges including daily tidal changes, a variety of infrastructure upgrades/installations, ever-changing weather conditions, and the need for specialty heavy equipment to implement the habitat restoration.

“This was a technically challenging project and all the construction work was completed by our heavy equipment professionals. What really floored me was the morning of the first tide-gate replacement,” Oregon Coast NWR Complex project leader Kelly Moroney. "We were following the tidal cycles, which required operations to begin a 3 a.m. I have been involved in many projects over my 25-year career, but nothing came close to what I saw when I pulled up to that morning. It almost looked choreographed. I was impressed. They are true professionals.”

Gary Rodriguez, a 32-year Service employee and now-retired Facilities Operations Specialist/ Engineering Equipment Operator at Oregon Coast National Wildlife Refuge Complex, served as lead for the project.

“Our job was to execute the project. We had plans, elevations and equipment, and then it was up to us to be able to put that all together. Some folks were skeptical if we could do it. From our standpoint, it was not a problem. It was going to happen, and that’s what we did,” Rodriquez said.

The crew during the nighttime installation was (from left) Kenny Berry from Malheur NWR; Shaun Matthews from Willapa NWR; Gary Rodriguez from Oregon Coast NWR Complex; Kelly Connall from Little Pend Oreille NWR; and Tyrone Asencio from Willamette Valley NWR Complex. Dave Harlow from Willamette Valley NWR Complex primarily worked on the channel restoration at Upton Slough.

Spencer Berg, heavy equipment manager for the Service’s Columbia-Pacific Northwest Region, also worked heavy equipment on the project. He says that wage-grade staff play an essential role in conservation for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

“I consider our wage-grade staff the backbone of the refuge system,” Berg said. “They’re doing the work on the ground, mowing the habitat, maintaining the boiler systems and parking lots, and creating wetland habitat. They are doing phenomenal things. On the Upton Slough project, a project like that takes a lot of planning and work to get going. You have to order the culverts and supplies, you have to get the permits, and watch the tide charts and weather. Getting all those factors lined up is a huge lift.”

All the construction work on the Upton Slough project was handled by the Service’s heavy equipment professionals, saving taxpayers close to $200,000 for the project.

Internally, multiple Service programs and departments helped with the development and execution of the program. Those programs include the Service's Water Resources Division, Inventory & Monitoring's Biological program, Ecological Services' Oregon Fish and Wildlife Office, Fisheries and Aquatic Conservation's Vancouver Office, and Connor Shea from the Partners for Fish and Wildlife in California.

External partners on the project included the Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians, Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, Nestucca, Neskowin & Sand Lake Watersheds Council and the Little Nestucca Drainage District.

“Like most projects these days, partnerships were huge,” Moroney said. “We could not have accomplished this project without help from internal and external partners.”

The Service also reconstructed the historic slough channel as a part of the project. It was returned to its original path, winding across the lowlands. This will reduce flooding, which will benefit landowners in the Upton Slough watershed basin and the Little Nestucca Drainage District.

It will also improve habitat for fish and wildlife. Dusky and Semidi Island Aleutian Canada geese, which are both identified as species of concern in the Pacific Flyway Council Management Plans, and other migratory waterbirds will benefit from the lowland pasture improvements. It’ll also improve fish passage and fish habitat requirements for federal- and state-listed Oregon coastal coho salmon.

“The bottom line is that the operators left their homes for two weeks, worked long hours as a team to deliver on a common goal,” Moroney said. “Their work and accomplishments on the Upton Slough project should be a model for refuges doing business. These professionals care about the resource, care about refuges, and take a lot of pride in their work – and it shows.”

Our wage-grade professionals -- the people who turn conservation ideas into conservation successes.

Story by Brent Lawrence / U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

youtube

youtube

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Walk alongside wild roses in bloom and watch summer unfold at Willapa National Wildlife Refuge in Washington. Explore the freshwater marshes, grasslands, coastal dunes, old growth forests and beaches -- and get to know one of the most pristine estuaries in the United States, Willapa Bay. Wet fields and soggy forests provide incredible wildlife viewing opportunities. Visitors may spot residents such as Roosevelt elk, long-tailed weasels, black bears, shorebirds, and spawning salmon. Walk the Art Trail boardwalk with friends and take in the sounds and sights of summer. Photo by Andy Zahn (www.sharetheexperience.org).

#nationalwildliferefuge#usinterior#travel#nootkaroses#willapanationalwildliferefuge#marshes#boardwalk#shorebirds#willapa bay#washington#adventure#walking trails#estuary#summer#summer beauty#beautiful destination#peaceful trails#get outdoors#outside adventure#pacific northwest#PNWliving

470 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Foxglove~ #PNW #Washington #WestCoast #Nature #sparrowatheartphotography #flower (at Willapa National Wildlife Refuge Complex) https://www.instagram.com/p/CB_uoDIjZDM/?igshid=6nx5wxi625ob

2 notes

·

View notes

Conversation

U.S. Daily Low Temperature Records Tied/Broken 4/7/22

Columbine Pass summit, Colorado: 4 (previous record 11 2010)

Unincorporated Fremont County, Colorado: 13 (previous record 17 2003)

Routt National Forest, Colorado: 4 (previous record 7 2003)

Unincorporated Saguache County, Colorado: 17 (also 17 2010)

Trinidad Lake State Park, Colorado: 16 (previous record 19 2009)

White River National Forest, Colorado: 14 (previous record 15 2012)

Unincorporated Hawai'i County, Hawaii: 42 (previous record 44 2008)

Riggins, Idaho: 25 (previous record 28 1959)

Hot Springs, Montana: 18 (previous record 20 2021)

Yellowstone National Park, Montana: 6 (previous record 7 1997)

Unincorporated McKinley County, New Mexico: 13 (previous record 14 2010)

John Day, Oregon: 17 (previous record 18 1959)

Unincorporated Linn County, Oregon: 27 (previous record 28 2021)

Unincorporated Malheur County, Oregon: 22 (previous record 23 2012)

Brigham City, Utah: 22 (previous record 23 2012)

Sequim, Washington: 20 (previous record 27 2002)

Willapa National Wildlife Refuge, Washington: 27 (previous record 29 2012)

Battle Mt. summit, Wyoming: 14 (previous record 15 2003)

Bone Springs Divide summit, Wyoming: 4 (previous record 5 2007)

Doubletop Peak summit, Wyoming: -3 (also -3 2008)

Unincorporated Park County, Wyoming: 13 (also 13 1997)

Wamsutter, Wyoming: 9 (previous record 12 1961)

#U.S.A.#U.S.#Colorado#Idaho#1950s#Oregon#Utah#Washington#Wyoming#1990s#1960s#Hawaii#New Mexico#Crazy Things#Awesome

0 notes

Photo

at Willapa National Wildlife Refuge https://www.instagram.com/p/Bnkjqjzg7kXQBVlC-_rwdZ9u2EbqoSVcDTy21k0/?utm_source=ig_tumblr_share&igshid=iyfogy6wjtsc

1 note

·

View note

Text

I'm going to politely ignore that Public Lands Day was yesterday and post some pics of some public lands.

Black Canyon Campground and Blue Pool in Willamette National Forest, Oregon.

Willapa National Wildlife Refuge, Washington

Chief Joseph Dam, USACE, Washington

Okanagan-Wenatchee National Forest, Washington

0 notes

Link

Birds by the Billions: A Guide to Spring’s Avian Parade At Washington’s Long Beach Peninsula, for instance, which abuts Willapa National Wildlife Refuge and Willapa Bay, you might catch sight of a pelagic species like a sooty shearwater, while hundreds of thousands of shorebirds like black-bellied plovers work the wet sand. If you’re extremely lucky, you might see an enigmatic marbled murrelet in an ancient Western red cedar, a seabird that only nests in mossy old-growth trees. Meanwhile, red-winged blackbirds and purple martins flock to Ridgefield National Wildlife Refuge on the Columbia River. Greater sage-grouse gather near Hart Mountain National Antelope Refuge. Grebes, a red-eyed, black-and-white relative to the flamingo, come to the Klamath Basin near Klamath Falls, Ore., to perform mating spectacles that include a splashy, synchronous “rush” of flightless running across the water. “Spring is always so fun because we get all the migrants back,” said Jackie Ferrier, a project leader in Washington’s Willapa National Wildlife Refuge Complex. “I mean swallows, ospreys, woodpeckers, warblers, turkey vultures. People think, ah, turkey vultures, but I get excited to see them every year.” Dianne Fuller can relate. After a long career in nursing, Ms. Fuller retired on Loomis Lake on Washington’s Long Beach Peninsula. Now 73, she’s been birding since she was 20. Come spring, there’s no place she’d rather be than walking the early morning dunes or paddling the flat water in a kayak and pointing out the kingfishers to her miniature Australian shepherd, Beau, who stows aboard. “Medicine is like detective work and it’s the same thing with birds,” Ms. Fuller said. “If you really watch them, study the length of the bill, the size of the feet, the shape of the wing, suddenly you realize this bird is filling some niche in this part of the world, and it’s just amazing.” TIM NEVILLE Source link Orbem News #Avian #billions #Birds #Guide #parade #Springs

0 notes

Text

Farewell to an Old Cedar–and Hello to a New One

Originally posted to my blog at https://rebeccalexa.com/farewell-to-an-old-cedar-and-hello-to-a-new-one/

Last Wednesday I had the opportunity to do some volunteering with Willapa National Wildlife Refuge. As the weather has finally turned better, with some warm, sunny days mixed in with the rain, it’s made conditions more favorable to getting outside. So when I got the email asking if I wanted to help plant some cedar trees, I jumped at the chance.

Western red cedar (Thuja plicata) is my very favorite tree. It’s not a true cedar, instead being a member of the cypress family Cupressaceae. But there’s something about the red-tinted bark powdered with Cladonia lichens, and the flat, scaly green needles that appeals to me. Maybe it’s because it’s some of the best of the coloration of Pacific Northwest forests all wrapped in one tree. Or perhaps it’s because I loved eastern red cedar (Juniperus virginiana) so much as a child, and I’ve just developed a fondness for cedars that aren’t actually cedars.

We have only a few tiny patches of old-growth forest here in the extreme southwest corner of Washington, mostly populated with ancient cedars and a few very old Sitka spruce (Picea sitchensis). My first real look at old-growth forest here was Teal Slough, a section of Willapa NWR that protects 140 acres. These ancient trees very nearly ended up logged a few decades ago, but for the heroic efforts of historian Rex Ziak. In the pre-internet times he spent months tracking down the then-corporate owners of this tract of land, and managed to convince them to cease logging with a letter, a photograph, and a rope loop the same circumference as one of these massive old cedars. (It’s a pretty incredible story that I got to hear him tell in person at Wings Over Willapa a few years ago.)

It really was at the eleventh hour, though. One of the first things an astute naturalist will notice when arriving at Teal Slough is that almost all of the trees are either very old–or very young. That’s because the undergrowth had been bulldozed in preparation for chopping down the couple dozen big trees left. It’s rebounded in recent years, but there are tons of scrawny young western hemlock trees (Tsuga heterophylla) along with a scattering of young cedars.

Adding more cedars was our original goal for that morning, which was cool but sunny. We brought ten young trees with us, but stopped at the old Refuge headquarters just down the road from Teal Slough. It turned out that the place we were originally going to plant them was where the old logging road cut through, and the heavy gravel made digging by hand impossible. So we planted eight to create a windbreak at the old HQ, which is itself going through a slow metamorphosis, and tucked the other two back into the truck.

And then it was time to head to Teal Slough itself. While we couldn’t plant trees, we could still pick up debris from the storms that came through. The bigger branches and fallen saplings made good material for outlining the trails, making them more visible to visitors. While the old logging road is pretty obvious, some of the footpaths that diverge off the main trail to showcase big trees further back in the woods were getting tougher to discern. So we spent some time lining them with some of the windfallen materials.

But I also want to touch on the original reason we were slated to go out there that day. See, those young cedars were originally going to be used to help start to close off the last hundred feet or so of the trail. This last bit leads down to one of the biggest of the cedars at Teal Slough, and–to be quite honest–my favorite.

As it turns out, she’s not doing so well. She’s been rotted out inside for some time; this is normal, of course; in many cases an old tree can survive its heartwood rotting away completely, since that wood is dead. But this old cedar has been beginning to lean noticeably toward the northwest in recent months. There’s no disruption at ground level yet, no cracks in the earth or roots bursting forth to the surface. A Refuge employee was on the trail a few months ago during one of the vicious windstorms we’ve had over the winter, and he noticed this tree swaying more than usual.

We don’t know when she’ll fall. It might be later this year; it might not be for another century. But it was decided that the trail to her should be closed off just in case she came down when there were people around. A massive tree of this size would be quite a danger indeed; the day after our volunteering a logger was killed in the Willapa Hills after being hit by a much smaller tree. Even a section of this tree coming down at the wrong time could be disastrous. And beyond a certain size there’s really no way to buttress such an enormous thing, especially when it’s located on a slope of super-saturated soil.

We walked down the trail to where she still stood with her much younger hemlock “buddy tree” growing out of her side; many of the old cedars have similar hemlock companions. It was apparent she was listing more than I had seen her in the past, and there seemed to be a little more space between her and her hemlock. We all spoke of how magnificent she was, and how sad that it seemed she was nearing her end.

I lingered behind for a moment while everyone else moved the “End of Trail” sign back up to where the path would be cut off. It was my last moment to be up close and personal to this beautiful old cedar. While technically, yes, I could still steal up the path before it was completely planted or fenced or however the Refuge will eventually close it, I respect their decision and decided this would be my farewell. I told the tree how much I had enjoyed visiting her, and thanked her young hemlock as well. I touched the lichens that adorned her furrowed bark, and looked up at the broken crown of branches at her top.

Then I turned, with many glances backwards at a Eurydice I would never be able to bring home. I dragged with me a young alder that had fallen in a storm, and added it to the small pile of branches placed across the trail as a temporary barrier. And we headed back down to the road, with the sound of a pileated woodpecker (Dryocopus pileatus) rapping high overhead, and a rough-skinned newt (Taricha granulosa) waiting for us at the trailhead.

I don’t know when the old cedar will finally fall over, but when she does her death will not be in vain. Like all fallen trees, the countless molecules she accumulated over a millennium of life will slowly start to disperse throughout the forest through the actions of detritivores and decomposers. She will feed bacteria and fungi, insects that then become food for birds, and a whole host of plants that will make use of the vast stores of nutrients she holds, and the sunlight that her passing will reveal to the forest floor. Nothing ever goes to waste in a forest, not least of all a fallen tree.

As we drove back down 101 toward the new headquarters, I gave a glance to where we had planted the young cedars. I would never live to see them achieve that great stature; in fact, not all of them may even make it to maturity, especially if cedar die-back continues in our too-hot summers. But it is hope that allows me to continue to plant new things amid loss. I cannot help but try, even against the odds. And I can do two things at once: I can mourn the eldest of the trees as she makes her literal last stand, and I can also loosen the soil for one of her relatives to set roots and grow.

Did you enjoy this post? Consider taking one of my online foraging and natural history classes or hiring me for a guided nature tour, checking out my other articles, or picking up a paperback or ebook I’ve written! You can even buy me a coffee here!

#Pacific Northwest#PNW#Washington#Washington State#western red cedar#old growth forest#forests#Thuja plicata#nature#environment#conservation#trees#Willapa National Wildlife Refuge#wildlife refuge#volunteering

90 notes

·

View notes

Text

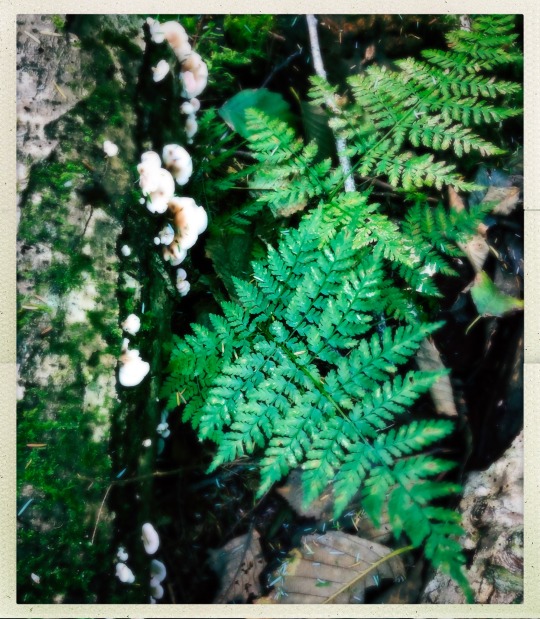

#willapa national wildlife refuge#IIwaco washington#my heaven#my phoyography#mushrooms#fern#nurse log#marksjunior

0 notes

Text

"Bringing back the butterflies: Project aims to restore vanished ‘coastal prairie’“: Some updates on restoration of very rare Pacific Northwest coastal “prairie” environments near the Pacific shoreline in the Willapa region of the Olympic Peninsula. The Oregon silverspot butterfly, endemic only to the immediate coastline of the northwestern Oregon and the Olympic Peninsula (with a tiny isolated population near Tolowa Dunes on the California coast), and it requires the presence of the wind- and salt-tolerant early blue violet. Non-native plants associated with Euro-American pastures took over the violet’s landscape, and Washington State’s last Oregon silverspot butterfly was recorded in 1990. (Aside from the prairie-oak woodlands of Willamette Valley and the Salish Sea shores, lowland open space is rare in the heavily forested coastal PNW.) Excerpts from a Chinook Observer article, 27 September 2019:

A rare butterfly species disappeared from the Long Beach Peninsula in 1990. Now, restoration of its vanished coastal prairie habitat at the South Bay Unit of Willapa National Wildlife Refuge aims to bring the butterflies back, along with the beautiful violets on which it depends.

Large-scale replanting to recreate the Oregon silverspot butterfly’s habitat began in August and will continue until February 2020, according to the U.S. Wildlife and Wildlife Service, which manages Willapa National Wildlife Refuge.

This butterfly species has declined in abundance and range over the past four decades and is in danger of extinction. Only six of the 20 populations that historically occurred along the Pacific coastline from Grays Harbor County to Lake Earl in Del Norte County, California currently exist.

Efforts on the Peninsula are considered critical for the recovery of the species, USFWS said. The last Oregon silverspot butterfly in Washington state was observed here in 1990, not far from the location where the current habitat restoration is taking place near the intersection of Sandridge Road and Pioneer Road between 85th and 95th Streets.

Population decline of the Oregon silverspot is mostly blamed on loss of native coastal prairie habitat due to development and introduction of non-native plant species.

Oregon silverspot butterfly larvae feed exclusively on the leaves of the early blue violet. This violet was once a widespread and abundant component of native coastal prairies because it is adapted to tolerate salt spray, low-intensity fires and soil movement by wind. Development of coastal areas led to fire suppression and the introduction of non-native plant species that quickly dominated coastal prairies, stabilizing the soil and overgrowing the violets.

If the restoration succeeds, it will replace existing non-native pasture with native coastal prairie and reestablish a thriving population of early blue violets. The first landscape-scale planting of the species this year includes more than 30,000 plants. Violets will be planted in plots where the upper layer of soil has been removed using heavy equipment, which was determined to be the most effective method of reducing the growth of non-native pasture that competes with the violets.

[Source: Chinook Observer, 27 September 2019.]

126 notes

·

View notes

Text

Racing the Tide

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service heavy equipment operators tackle challenging nighttime project on Oregon Coast

Story by Brent Lawrence, public affairs officer in the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Columbia-Pacific Northwest Regional Office.

The tide was slowly draining out of Nestucca Bay, and it was still hours before the sun would peek above the horizon. The only light was from headlights of the machinery that was already rumbling along in the cool night air, moving dirt at a furious pace.

A crew of U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service heavy equipment operators were racing the tide.

The objective was to install a fish screen for a pump, and remove and replace tide gates that help manage water levels on the Upton Slough section of Nestucca Bay National Wildlife Refuge on the Oregon Coast.

The entire project took weeks, but this critical element had to be done in a narrow window of time at the lowest tides last fall.

This work on soft ground on the bank of the Little Nestucca River was left to a crew of five heavy machinery operators from National Wildlife Refuges across the Columbia-Pacific Northwest Region.

In bureaucratic terms, the heavy equipment operators are known as wage-grade professionals. That’s the official term.

But to project leaders, facility managers and biologists --- they simply call them the backbone of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. They're the people who turn habitat conservation dreams into reality.

They're creators of conservation.

“They are so important to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service's mission. Without our wage-grade professionals, we couldn't accomplish the important habitat and conservation work we do on refuges. They're unsung heroes of conservation,” said Kevin Foerster, Refuge Chief for the Columbia-Pacific Northwest Region.

Due to the location and environmental factors for the Upton Slough work, this project had a variety of technical challenges including daily tidal changes, a variety of infrastructure upgrades/installations, ever-changing weather conditions, and the need for specialty heavy equipment to implement the habitat restoration.

Watch the full Story Map with videos and interviews at https://fws.maps.arcgis.com/apps/Cascade/index.html?appid=64cdfe78fe87436881551befde79b8e7

“This was a technically challenging project and all the construction work was completed by our heavy equipment professionals. What really floored me was the morning of the first tide-gate replacement,” Oregon Coast NWR Complex project leader Kelly Moroney. "We were following the tidal cycles, which required operations to begin a 3 a.m. I have been involved in many projects over my 25-year career, but nothing came close to what I saw when I pulled up to that morning. It almost looked choreographed. I was impressed. They are true professionals.”

(Facilities operations specialist Gary Rodriguez, left, and Oregon Coast National Wildlife Refuge Complex project leader Kelly Moroney.)

Gary Rodriguez, a 32-year Service employee and now-retired Facilities Operations Specialist/ Engineering Equipment Operator at Oregon Coast National Wildlife Refuge Complex, served as lead for the project.

“Our job was to execute the project. We had plans, elevations and equipment, and then it was up to us to be able to put that all together. Some folks were skeptical if we could do it. From our standpoint, it was not a problem. It was going to happen, and that’s what we did,” Rodriquez said.

The crew during the nighttime installation was (from left) Kenny Berry from Malheur NWR; Shaun Matthews from Willapa NWR; Gary Rodriguez from Oregon Coast NWR Complex; Kelly Connall from Little Pend Oreille NWR; and Tyrone Asencio from Willamette Valley NWR Complex. Dave Harlow from Willamette Valley NWR Complex primarily worked on the channel restoration at Upton Slough.

Spencer Berg, heavy equipment manager for the Service’s Columbia-Pacific Northwest Region, also worked heavy equipment on the project. He says that wage-grade staff play an essential role in conservation for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

“I consider our wage-grade staff the backbone of the refuge system,” Berg said. “They’re doing the work on the ground, mowing the habitat, maintaining the boiler systems and parking lots, and creating wetland habitat. They are doing phenomenal things. On the Upton Slough project, a project like that takes a lot of planning and work to get going. You have to order the culverts and supplies, you have to get the permits, and watch the tide charts and weather. Getting all those factors lined up is a huge lift.”

All the construction work on the Upton Slough project was handled by the Service’s heavy equipment professionals, saving taxpayers close to $200,000 for the project.

Internally, multiple Service programs and departments helped with the development and execution of the program. Those programs include the Service's Water Resources Division, Inventory & Monitoring's Biological program, Ecological Services' Oregon Fish and Wildlife Office, Fisheries and Aquatic Conservation's Vancouver Office, and Connor Shea from the Partners for Fish and Wildlife in California.

External partners on the project included the Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians, Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, Nestucca, Neskowin & Sand Lake Watersheds Council and the Little Nestucca Drainage District.

“Like most projects these days, partnerships were huge,” Moroney said. “We could not have accomplished this project without help from internal and external partners.”

The Service also reconstructed the historic slough channel as a part of the project. It was returned to its original path, winding across the lowlands. This will reduce flooding, which will benefit landowners in the Upton Slough watershed basin and the Little Nestucca Drainage District.

It will also improve habitat for fish and wildlife. Dusky and Semidi Island Aleutian Canada geese, which are both identified as species of concern in the Pacific Flyway Council Management Plans, and other migratory waterbirds will benefit from the lowland pasture improvements. It’ll also improve fish passage and fish habitat requirements for federal- and state-listed Oregon coastal coho salmon.

“The bottom line is that the operators left their homes for two weeks, worked long hours as a team to deliver on a common goal,” Moroney said. “Their work and accomplishments on the Upton Slough project should be a model for refuges doing business. These professionals care about the resource, care about refuges, and take a lot of pride in their work – and it shows.”

Our wage-grade professionals -- the people who turn conservation ideas into conservation successes.

Juvenile coho salmon found in Upton Slough

Checking depths for tide gate construction.

Setting a tide gate that helps drain water from Upton Slough to the Little Nestucca River.

Dusky Canada geese are on of the species that will benefit from the work on Upton Slough.

Gary Rodriguez was the project lead. He spent 32 years in public service before his recent retirement.

Story posted 6/26/2020

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Sooty Shearwaters (Ardenna grisea), Willapa National Wildlife Refuge Complex, coastal WA, USA

It's a great time to head to the Refuge and beaches of Long Beach Peninsula to witness the incredible journey of the Sooty Shearwater.

The sooty shearwater is one of the most abundant bird species in the world, with a total population estimated at about 20 million. These seabirds cross the equator twice a year in pursuit of an endless summer in which their feeding areas are always at or near peak productivity.

During the longest recorded animal migration, sooty shearwaters migrate nearly 40,000 miles a year, flying from New Zealand to the North Pacific Ocean every summer in search of food. They are often found in groups of hundreds or thousands, flying in long lines or grouped tightly together on the water.

They plunge into the water from a few feet above the surface and swim under water, using their wings to propel themselves. They also dive from the surface, taking prey at surface level, or just below. They sometimes feed near dolphins, whales, or other seabirds. They are also vulnerable to changes in their food supply.

http://www.birdweb.org/Birdweb/bird/sooty_shearwater

http://terranature.org/sootyShearwaterMigration.htm

http://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/sooty-shearwater

via: U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service

36 notes

·

View notes

Photo

driving up the coastal Washington highway can gift another perfect sunset #sunset #westcoast #roadtrip #river #lewisandclarktrail #washington #naturephotography #nature #natureshots #travel #traveling #travelphotography #explorewashington #explore #scenic #water #sky (at Willapa National Wildlife Refuge Complex)

#travelphotography#scenic#nature#sunset#roadtrip#water#naturephotography#river#travel#washington#lewisandclarktrail#traveling#explore#explorewashington#natureshots#westcoast#sky

1 note

·

View note